Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA) (尤伦斯当代艺术中心)

21 July through 18 October 2018, Beijing

For most of us, the only glimpse of the 2018 Beijing exhibition Xu Bing: Thought and Method will have come from online articles, screen shots and a short film or two. By noting commentaries contemporaneous with the exhibition and linking them to older related articles and books, Books On Books aims to enhance appreciation of the exhibition and Xu’s work as well as findability of the latter. Throughout, where known, links to institutions holding Xu’s works are provided.

May 2018 saw the first announcement of the Xu Bing retrospective, his “most comprehensive institutional exhibition” to date, according to Sue Wang writing for CAFA Art Info.

July 2018, just before the exhibition’s opening, Helena Poole’s article arrived to guide the reader on what to expect from the exhibition. One of its useful observations is the influence of the printmaking tradition of Lu Xun on Xu’s early prints. Although not a printmaker himself, Lu stimulated the tradition with his activist writing and encouragement of woodcut printmaking in the journals of the Morning Flower Society (朝花社) founded in 1929. In Art in Print (May-June 2016), the reader can find a useful background on Lu Xun and a selection of images from the New Woodcut Movement that will deepen Poole’s guidance.

Also helpful to a better appreciation of the prints are two online displays of images (more than offered by Wang and Poole): ArtThat eLite and RADII China’s “Photo of the Day”. Both displays enable us to see that, while Xu’s early prints — for example, The End of a Village (1982) — reflect the New Woodcut Movement style, his later work is at once more subtle and abstract than that of the early revolutionary periods and yet still evocative of the figurative, the diurnal and strife. The subtlety lies in the shift from the depiction of workers’ strife to the strife between sense and nonsense or language and concept, between cultures and their languages, and between the individual and polity.

From A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, prepared by Patricia Buckley Ebrey et al. Accessed 2 August 2017.

Just after the exhibition’s opening, two excellent overviews of Xu’s career and art appeared in July. Sue Wang followed up her May announcement with a translation of an essay by Lin Jiabin expanding on the exhibition’s title Xu Bing: Thought and Method. Rather than focus on any one work, Lin Jiabin digs into the artist’s thought and method. Among Lin’s several useful insights are these:

Xu Bing adheres to the essence of simplicity and wisdom of eastern culture, and also faces the world in a broader sense. His works are forward-looking and vigilant; at the same time, his works under the guise of dislocation, multi-level social issues and cultural thinking sway and excite each other. [Emphasis added]

… the new work is an excavation and extension of something that is valuable in the past and that was not fully realized. It actually has a “cue” effect. Xu Bing said, “As long as you are sincere, no matter what form these works are, big or small, no matter how early or late, actually the final relationship between them is like constructing a closed system.” [Emphasis added]

Through the transformation of old artistic languages and the creation of new languages, the artist provides the audience with a variety of channels for entry and exploration. [Emphasis added]

Lin Jiabin, “Xu Bing: Constructing a Closed ‘Circle’“, CAFA Art Info, 25 July 2018. Accessed 2 August 2018.

The second overview — Grace Ignacia See’s “UCCA Presents …” in The Artling — takes a more descriptive and linearly developmental view following the exhibition’s division into three sections, “a direct reflection of the turning points in [Xu’s] artistic context and processes”.

The first section:

Book from the Sky (1987-1991), Ghosts Pounding on the Wall (1990-1991), and Background Story (2004-present) allow viewers to observe the means in which Xu’s meditations on signification, textuality, and linguistic aporia have been evoked;

The second section:

A, B, C… (1991), Art for the People (1999) and Square Word Calligraphy (1994-present) project his explorations of hybridity, difference, and translingual practice through his works;

The third section:

his more recent works Tobacco Project (2000-present), Phoenix (2008-2013), Book from the Ground (2003-present) and his first feature length film Dragonfly Eyes (2017), exist as commentaries on economic and geopolitical changes that have contributed towards China’s societal evolution and the world’s in the last hundred years.

Grace Ignacia See, “‘Xu Bing: Thought and Method’, an Artistic Career that Spans More than Four Decades“, The Artling, 26 July 2018. Accessed 2 August 2018.

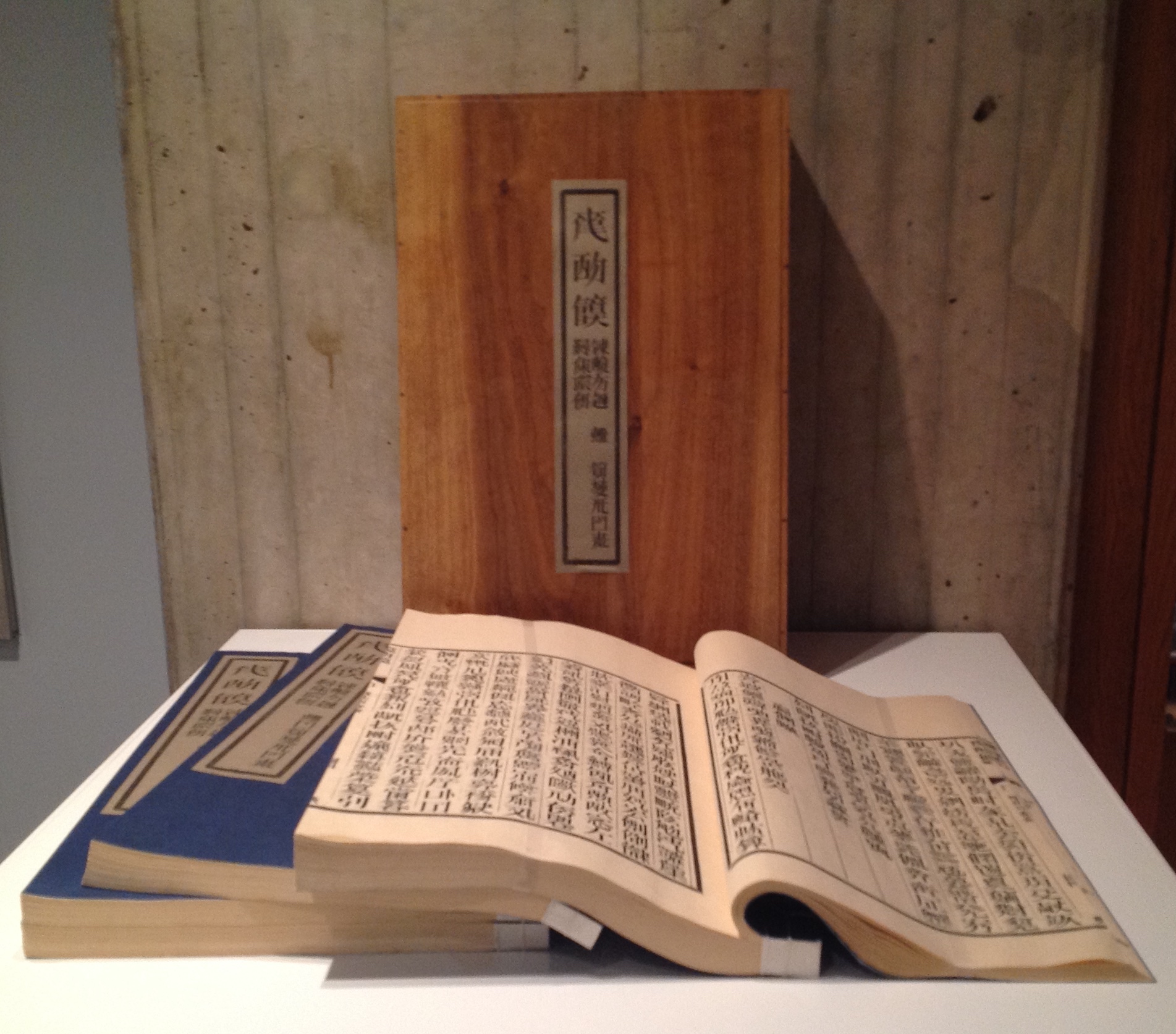

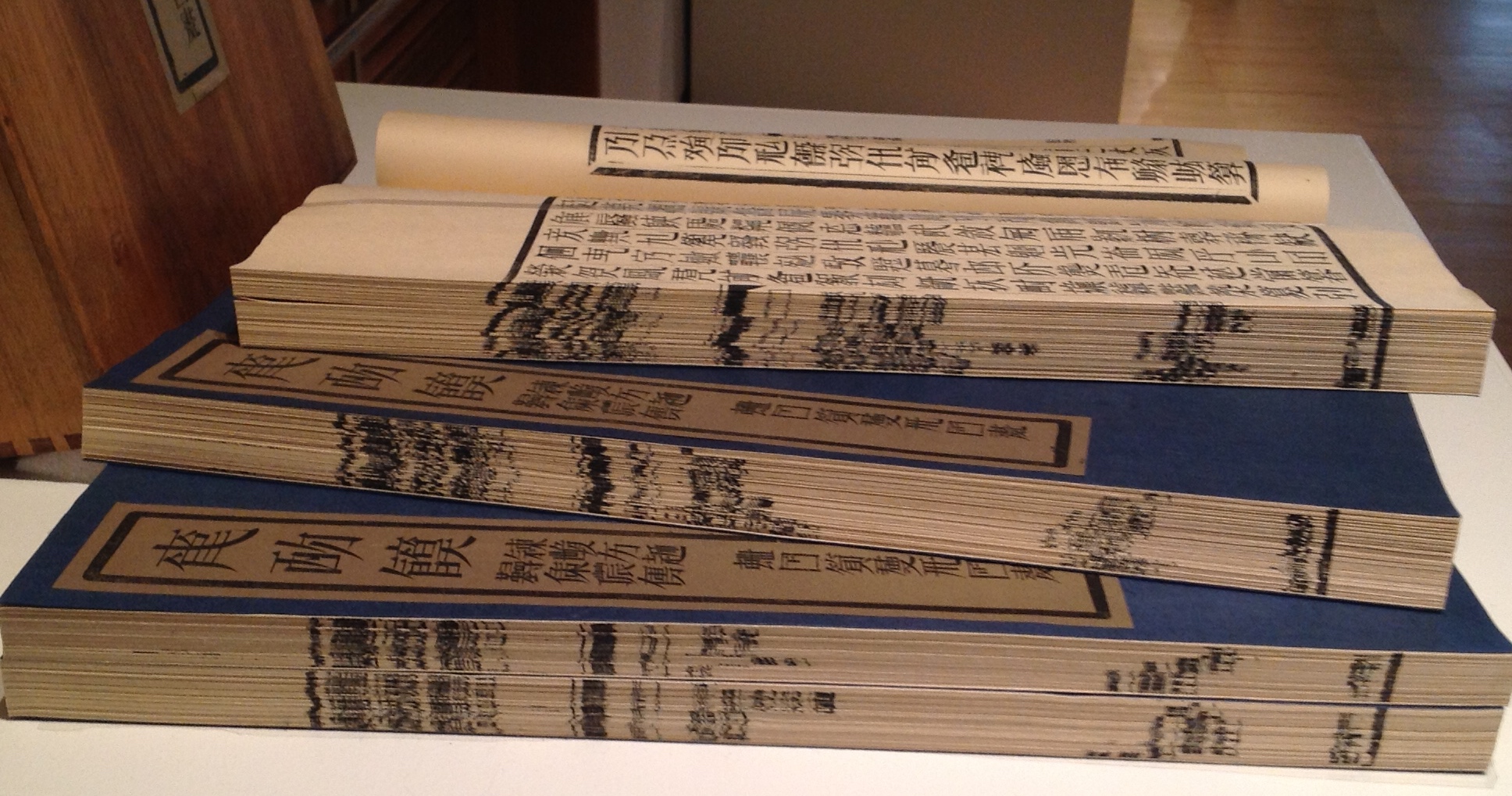

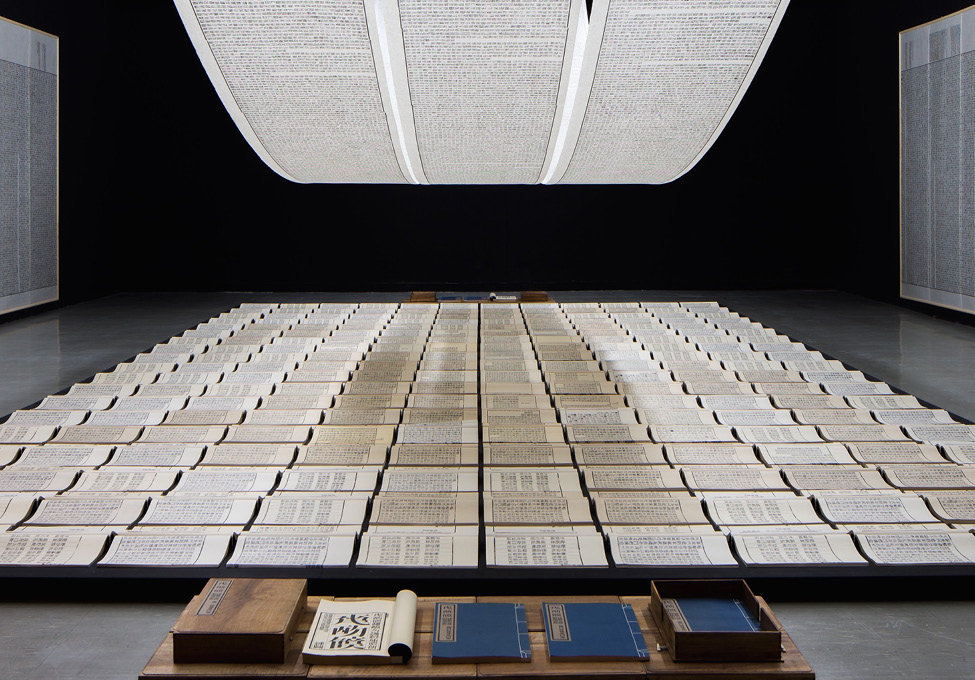

Tianshu or Book from the Sky, consisting of four volumes enclosed in a fastened wooden box, is a challenge to find, almost as much a challenge as being in the right place to see its installation version. The greatest challenge for a Westerner, however viewing the work, is grasping a Chinese viewer’s perception of it. How to imagine markings that, at first, look like the characters of the roman alphabet and even seem to form combinations that look like words and sentences but, on closer inspection, are not any letter, word or sentence known or knowable to the Western eye. Xu carved 4000 wooden stamps for characters that look like Chinese characters but are not and proceeded to have the four volumes printed under his instruction — as well as scrolls and wall hangings for installations.

Xu Bing

From the Allan Chasanoff Collection, Yale University Art Gallery

Xu Bing

View of installation

For a lengthier description and appreciation of Tianshu, John Cayley’s commentary and lecture are only surpassed by his book, where he writes:

[Tianshu is] not an object. It’s not a painting or a sculpture or even a book as such. It’s a configuration of objects and materials that represent a concept and provide some evidence or record of the development of the concept and the making of its constituent elements. You can’t possess it. You either have to find some elaborate way to acquire a personal record of the work or you have to take part in a process that allows the installation to remove itself into a museum or major gallery where this representation, beyond an individual’s acquisitive capacities, can be preserved for collective curated culture. In a sense, I’m helping you to ‘own’ the Tianshu by writing this.

John Cayley. Tianshu: Passages in the Making of a Book (London: Quaritch, 2009). Pp. 1-2.

Given the challenge of tracking down locations to visit where Tianshu has been acquired, Cayley’s “help” is welcome. The Beijing exhibition’s installation can be seen at the 4’04” mark in the UCCA video.

Although nicely illustrated in See’s article, Ghosts Pounding the Wall (1990) needs a bit more commentary for a fuller appreciation. According to Julia F. Andrews and Kuiyi Shen in The Art of Modern China (2012), the work was Xu’s response to the criticism that Book from the Sky demonstrated he had lost his way “like ghosts pounding the wall” (p. 258). It’s also worth noting that these two works have in common the process of turning one form of work into another.

Just as Book from the Sky consists of the four volumes in a wooden box yet is also an installation with scrolls and wall panels repeated in multiple venues, Ghosts Pounding the Wall began as the performance by Xu and his students wearing bright yellow jackets, stenciled with characters from Book from the Sky, and rubbing ink on rice paper fastened piece by piece across a one-kilometer stretch of the Great Wall and also is the installation. The latter is nicely shown in See’s article and can also be seen in the UCCA video at the 5’20” mark. Xu’s performance was one of “ghosts pounding the wall”; the installation, one of the ghostly impressions from that pounding of the wall. This characteristic or method in Xu’s art is one to watch for in almost all of his work.

Background Story, the third work in this section, is an installation and as such only fully accessible when in situ like Ghosts and later works. It first appeared in 2004. What appears to be a Chinese landscape printed on rice paper secured in a long row of joined-up lightboxes extending across the space of the host gallery is actually formed of shadows cast by objects on the other side of the lightboxes, which are open to view. Over time, the installation has developed as a series, with each version being based on a different ancient Chinese landscape painting. Usually the painting belongs to the institution where the work is installed. Four of the versions can be found at these links to videos and a slide show: 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015. The 2018 version can be found in the UCCA video at the 6’16“ mark.

In the meantime, another earlier essay from Sue Wang provides useful insights on experiencing the version based on the painting “Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains” by the Yuan dynasty painter Huang Gongwang. This version appeared in 2014 in Beijing as jointly organized by the Inside-Out Art Museum, Jing & Kai, the Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media at Cornell University, Life Bookstore and SDX Joint Publishing Company.

Xu Bing

Photo credit: Joy Lidu Yi

Wang also includes an interview with Xu about the process and intent of Background. The work marks a departure from Xu’s traditional materials: ink, paper, print, characters and language, but as Xu points out to Wang:

… whether using ink or not isn’t the issue at the core, while the most important thing is what the artist wants to express. It is necessary to think of what material does well in the presentation of the expected effect and the words of the artist. It may be a new language that no one speaks, it is a new language of the time, so it is in need of finding a new way of speaking ….

Sue Wang, “Xu Bing’s ‘Background Story: Dwelling in Fuchun Mountains’ Opened at Inside-Out Art Museum“, CAFA Art Info, 29 May 2014. Accessed 4 November 2018.

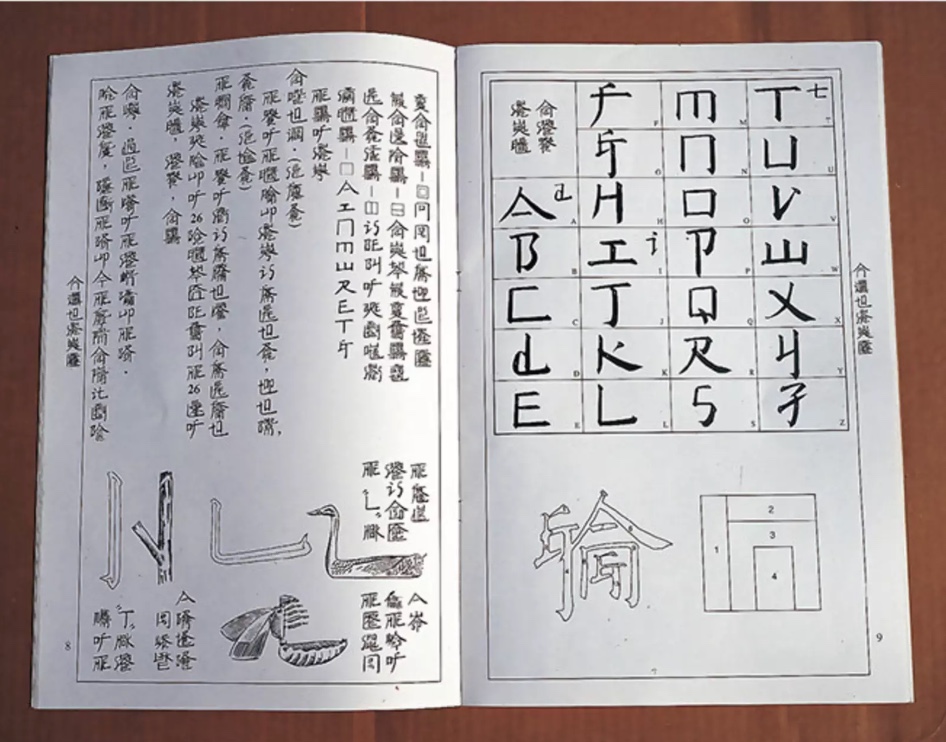

The second section of the 2018 Beijing exhibition brought into focus Xu’s deepening thought about language and culture when confronted with English and the art scene in the US and elsewhere in the West. See’s article highlights A, B, C… (1991) and Square Word Calligraphy (1994-present) as examples of Xu’s “explorations of hybridity, difference, and translingual practice through his works”. One of those works is An Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy (2000), a woodblock hand-printed accordion book with ink rubbings and wood cover. It is a textbook written by Xu Bing for users to learn the square word calligraphy writing system invented by the artist himself. The “installation version” consists of a classroom set up for learning and practicing the system.

Xu Bing

Columbia University has produced a video of one such installation, which demonstrates the fun of interacting with art. For most of us, though, an easier means of interacting with square word calligraphy and owning a bit of Xu’s art is to purchase the children’s songbook shown below.

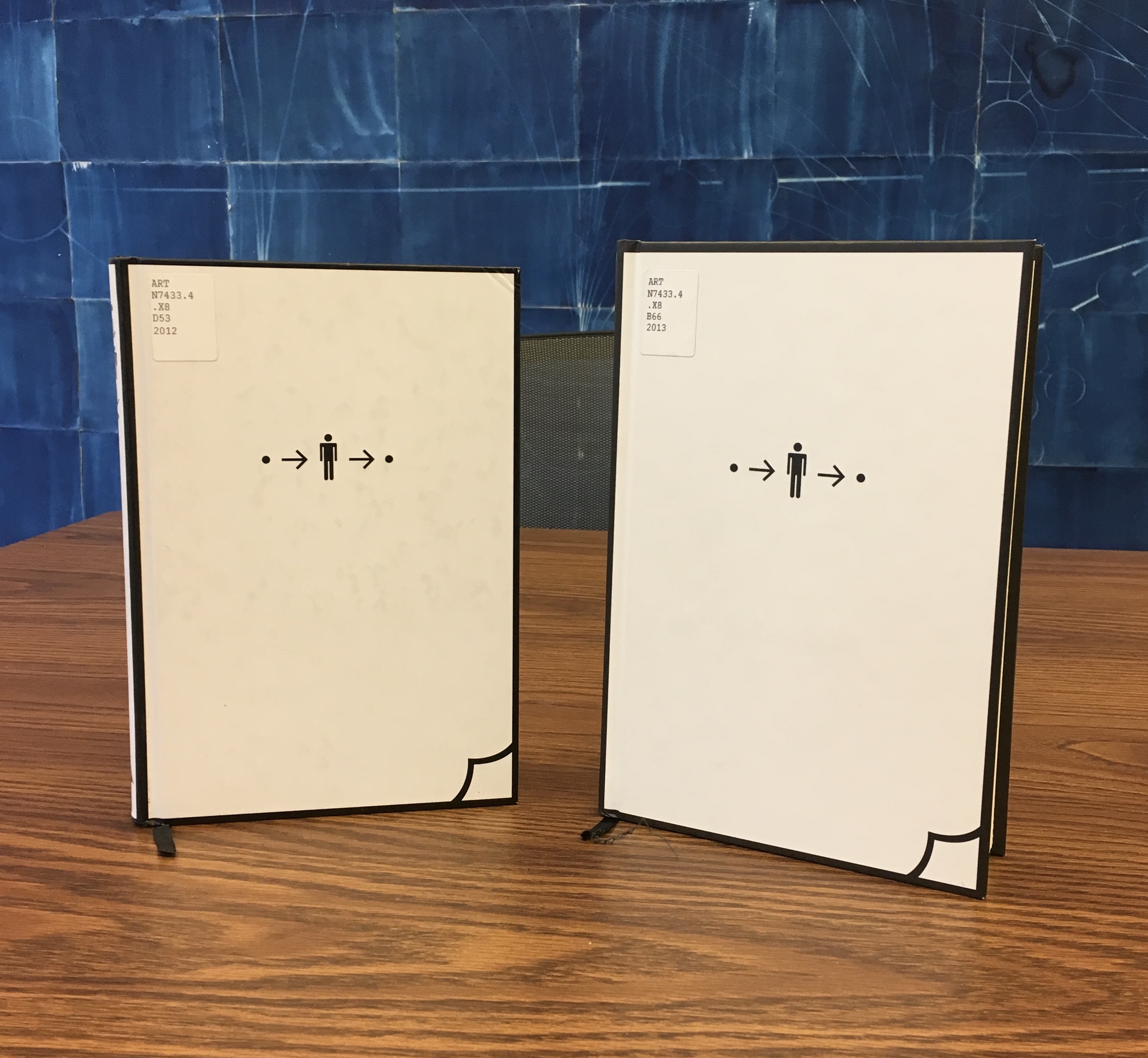

Another book by Xu, related to this third section of the Beijing exhibition and available for purchase, is Book from the Ground (2014), telling a day in the life of Mr. Black, an office worker — told completely in the symbols, icons, and logos of modern life. Xu’s playful but serious, to-and-fro treatment of language, meaning and cultures is another recurrent characteristic of his work.

Xu Bing

From the Hanes Library, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Notice the difference in size. On the left is the “Chinese” edition; on the right, the “English”. Why the quotation marks? There are no differences in the icons in which the narrative is written! Of course, the book trade being what it is, the traditional trim sizes are one cultural difference Xu could not erase.

Full appreciation of Xu’s signature interest in language — text and art, culture and meaning — would have sent the attendee in Beijing back from section two or three to section one to look at Book from the Sky again.

Serendipitously, another Xu exhibition was running nearby at INK Studio in Beijing at the same time: Xu Bing: Language and Nature. That show’s curator, Dr. Britta Erickson, is also the author of The Art of Xu Bing: Words without Meaning, Meaning without Words (2001). Her book covers many of the works in sections one and two and delivers insightful, plain-language readings of them that add considerably to the appreciation of Xu’s art. Again, as with the UCCA retrospective, Radii China delivers some outstanding photos from the INK Studio exhibition, and its briefest description makes the reader hunger for more as well as an actual visit:

… a selection from his The Living Word series in which the Pinyin Chinese word for bird, niao, transforms over a series of serial sculptures into the simplified character 鸟, then the traditional character 鳥, then, finally, into a small flock of birds soaring toward the gallery’s skylight.

“Photo of the Day: Xu Bing Hangs Birds from the Sky at INK Studio, RADII China, 26 July 2018. Accessed 2 August 2018.

A visitor could have hardly hoped to take in the UCCA and INK exhibitions in less than several days.

Xu’s conceptualism, genius for planning and meaningful attention to the detail of material recurs again and again in his work. He has a deft wittiness and patient, opportunistic eye, ear and even nose for enriching his artwork after the fact. Section three’s strong odor of tobacco must have underscored that to visitors.

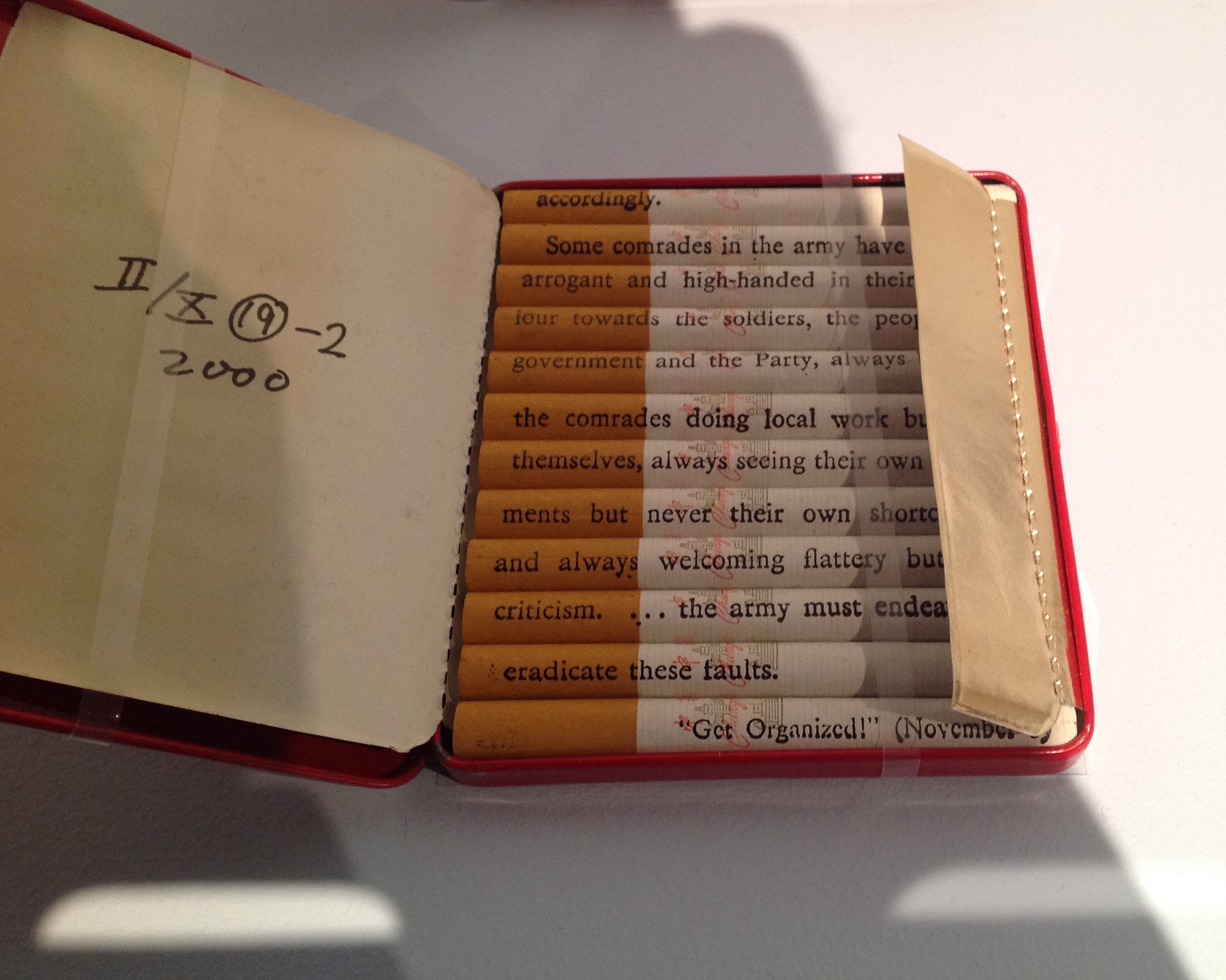

Xu Bing

From the Allan Chasanoff Collection, Yale University Art Gallery

Xu’s Tobacco Project trilogy, which began in 1999, incorporates Red Book (with Chinese and English inscriptions on each cigarette from Mao’s little Red Book), the floor sculpture Honor and Splendor (composed of 660,000 Fu Gui cigarettes) and several other related works. For an earlier in-depth piece on the Tobacco Project (and extensive illustrations), the reader can go to John Ravenal’s description in Blackbird (Fall 2011, Vol 10, No. 2). As the curator who organized the Tobacco Project exhibition in 2011, Ravenal’s perspective is unique. Like John Cayley, Ravenal also produced a book — Tobacco Project, Duke/ Shanghai/ Virginia, 1999–2011 (2011).

Introducing another of Xu’s major works — Phoenix (2008-13), not in the exhibition — See argues, contrary to Lin Jiabin, that Xu has been on a path to a shift in focus:

Phoenix (2008-13) and Dragonfly Eyes (2017) further highlight Xu’s … shift towards the economic and geo-political, where the first comments on China’s breakneck development and the latter dramatizes the role of individuals within the framework of an ever-expanding surveillance network.

Grace Ignacia See, “‘Xu Bing: Thought and Method’, an Artistic Career that Spans More than Four Decades“, The Artling, 26 July 2018. Accessed 2 August 2018.

See’s comments on these works closing section three of the Beijing exhibition miss the presence of a tension in them — or rather tensions present in all of Xu’s works from the very beginning. In a way, those ongoing tensions support the analysis of Lin Jiabin and how Xu’s works “sway and excite each other”.

August 2018. Enid Tsui surfaced the primary tension a few weeks later — worth the wait for the artful weaving of her own observations with Xu’s comments — in a “long read” in the South China Morning Post Magazine. That tension is between, on the one hand, the exquisite and, on the other, the cynical, the pessimistic, the ugly and anger. For Tsui, the anger is most evident in “Xu’s latest, and most bizarre, work … Dragonfly Eyes (2017)”:

His team edited 10,000 hours of surveillance footage into an 80-minute feature film loosely structured around the story of a man running after the woman he loves. There are no actors or cameramen. … Xu used only clips that were never meant to be seen in public. Film critics were baffled. Xu says the work is, once again, about how we are shaped by culture. The scenes in Dragonfly Eyes hardly fill you with joy: beauty parlours selling cosmetic surgery packages; aggressive customers in a shop; drab, anonymous streets. Scenes of terrible natural catastrophes or accidents add to the general atmosphere of doom. There is an uncustomary fury here about the state of the world, beyond the film’s obvious reference to how we are all being surveilled by invisible, all-seeing eyes.

Enid Tsui, “Chinese artist Xu Bing’s Beijing retrospective reveals his attitudes to China and Western art, but don’t call him a pessimist“, South China Morning Post Magazine, 11 August 2008. Accessed 2 September 2018.

“The exquisite” shows in the attention to detail and exactitude of execution. There are other tensions at play within and across Xu’s works: cynicism vs idealism, pessimism vs optimism, tranquillity vs anger, sense vs nonsense, meaning vs meaninglessness, beauty vs ugliness. But if The Beijinger‘s regular arts columnist, G.J. Cabrera, is right in his August article extolling the accessibility of Xu’s art,

… the exhibition is rife with examples of how Xu’s witty thought processes can find technically challenging ways to address questions about linguistic processes or historical circumstance, which resonate not only in his homeland but also worldwide. The content is surprisingly accessible and not at all obscured by the dense narrative which could easily hijack the content when dealing with such deep themes.

G.J. Cabrera,”State of the Arts“, The Beijinger, 29 August 2018. Accessed 2 September 2018

then shouldn’t those tensions be able to shape our appreciation of the works without explanations from articles and essays like this one and those above? If we are attentive enough, yes. Xu’s works are clever and beautiful enough, sometimes appalling and shocking enough, almost always playful and serious enough to make the viewer pause and attend — to hear Xu’s works say, “Language, the things of our cultures and their differences are not always what they seem”.

Locations of works

Book from the Sky

- British Museum (London, UK)

- Harvard Library (Cambridge, MA, USA)

- University of Wisconsin – Madison

- Yale University Gallery of Art (New Haven, CT, USA)

- Videos

Ghosts Pounding the Wall

Background Story

- Xu’s website lists the installations and locations since 2004.

- Videos

An Introduction to Square Word Calligraphy

- Asia Art Archive (Hong Kong, China)

- US libraries through WorldCat

- Yale University Gallery of Art (New Haven, CT, USA)

- Videos

Tobacco Project

- Xu’s website lists the installations and locations since 2000.

- Yale University Gallery of Art (New Haven, CT, USA)

- Videos

Phoenix

- Xu’s website lists the installations and locations since 2008.

- Videos

Dragonfly Eyes

General

“Xu Bing in ‘Beijing’: Art in the Twenty-First Century“, Art21, 25 September 2020.

Thanks so much for this! A serious piece of research and a nice bit of writing as well. ; ]

LikeLike

I adore Xu Bing’s work!

LikeLike