Lessons from the South (1986)

Lessons from the South (1986)

Susan E. King

Modified flag book. Closed: H270 x W172 mm; Open: W670 mm. 20 pages. Acquired from Rickaro Books BA PBFA, 22 September 2023.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Lessons from the South presents a masterful weaving together of material, structure, technique and image with Susan King’s reminiscences and social observations of her birth state Kentucky. For King, growing up white and female in the South in the second half of the 20th century engendered a sense of otherness and rebellion. As with some white southerners, it led to mild acts of rebellion — sitting too far back in the bus, sitting next to black students in typing class, or finally leaving for other regions of the US. With the 21st century’s rise of the “Karen”, repression of voting rights and reproductive rights, and resurgence of white supremacy, can we afford to dismiss the expression of conscience as “mild”? Any expression of conscience is something. Lessons from the South is an artful expression of fondness, humor, closeness and distance — a sense of being ill at ease with a Southern heritage we all seem unable to escape — that should be revisited not only for the sake of its art but as encouragement to conscience.

Start with the cover above. In that light, at that angle, the corrugated plastic front and back covers of Lessons from the South resemble those backdoors in the South with frosted louvres that covered a screen and could be cranked open to let in cool air while the screen kept out insects. But the elbow crank was almost always cranky — particularly if the louvres had been closed tightly over a long period. Sure enough, it is a bit difficult to open this book.

A top-down view of the modified flag book structure.

As Johanna Drucker points out in The Century of Artists’ Books, the interior’s heavy translucent sheets attached to the spine “hold a hard fold, the crease of their edges functioning as a rigid element” that fights the reader’s access to the interior pages.

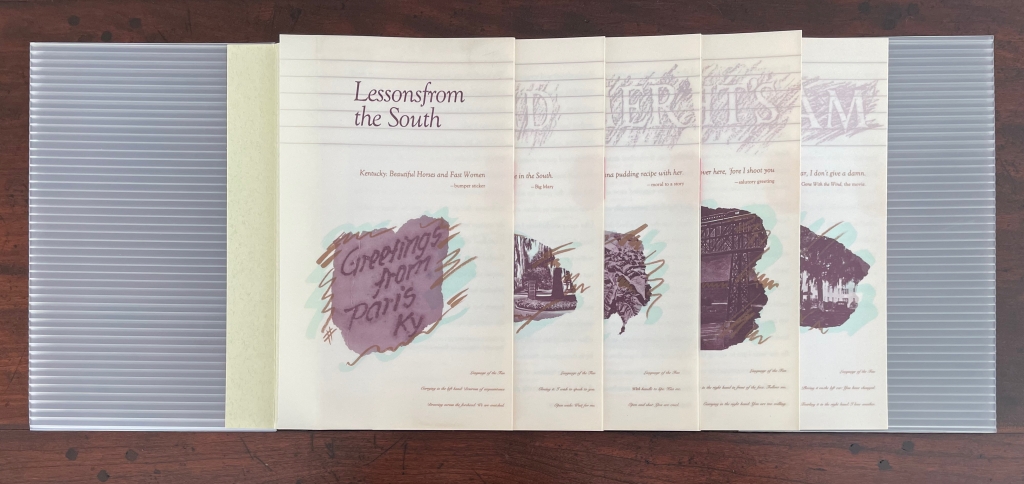

Even when the front cover is turned codex style, the binding and interior stiffness nudge you instead to pull and slide the front cover to the left, revealing the five sections of the book overlapping one another in a sideways continuation of the louvre motif.

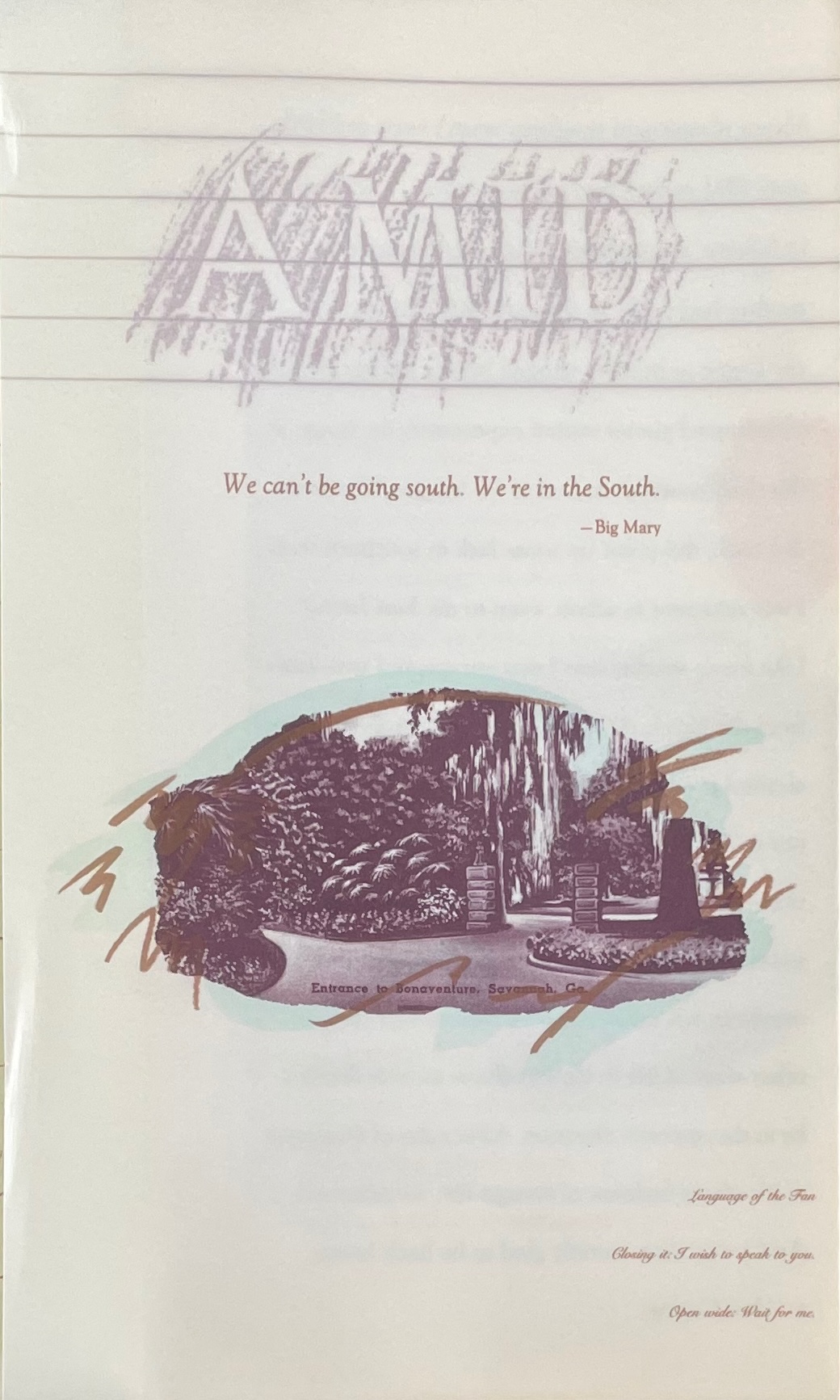

Each section’s opening page carries a pair of quotations. The first pair comes from a billboard (or postcard), a bumper sticker, a joke, a common expression and a movie. The second pair in the lower right corners comes from the 19th century leaflet The Language of the Fan, produced by Duvelleroy, a fan maker in Paris, France, which complements the book’s opening billboard image “Greetings from Paris, KY”. After the italic book title that opens the first section, the section titles of the following four sections are parts of the phrase “A MID SUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM” and seem to be rubbings from an engraving.

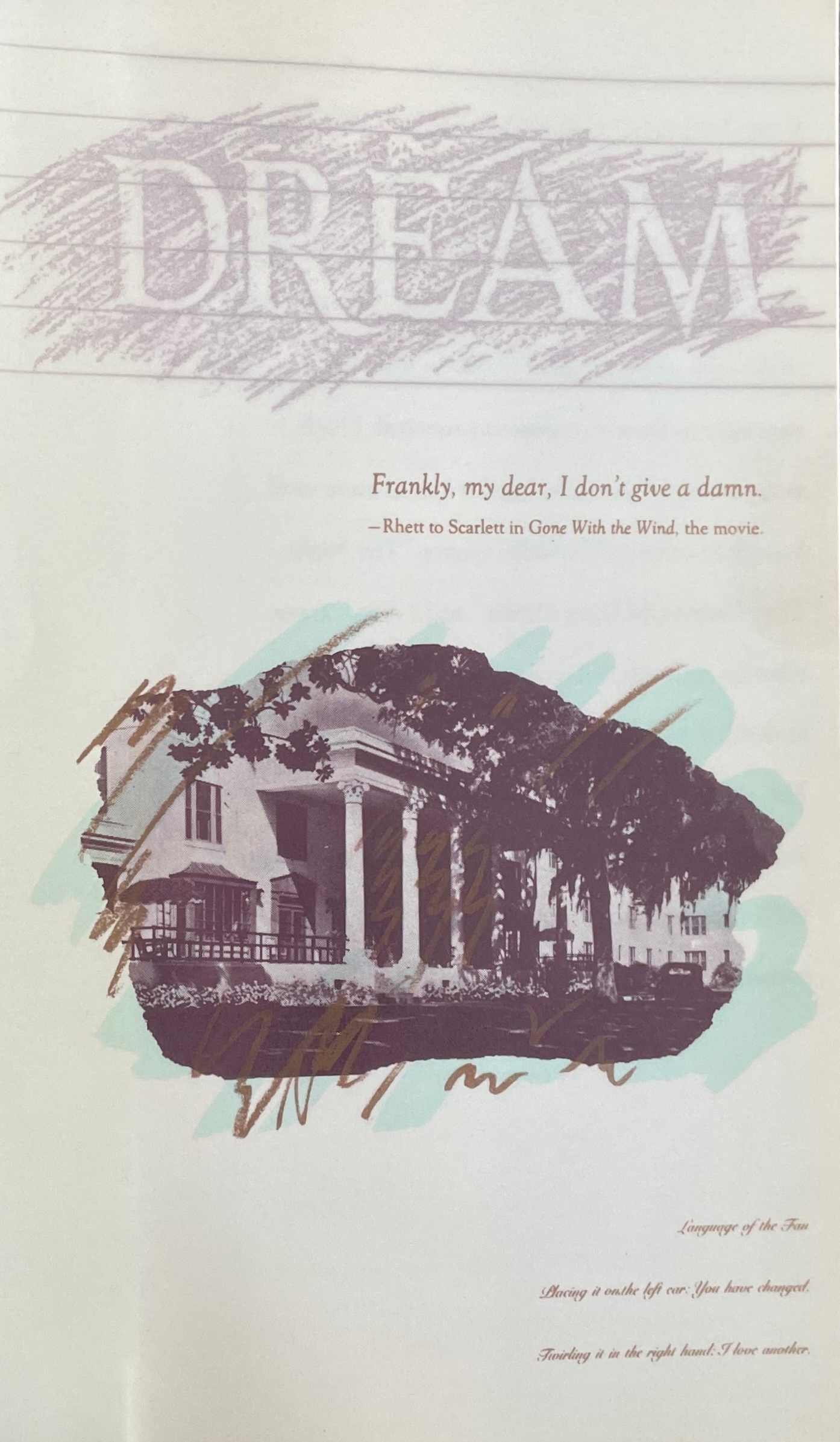

The image under ” A MID” is the entrance to Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah, Georgia . The second shows a tobacco field being inspected by a woman dressed all in white, including a large sun bonnet. The third is a night-time scene of a train crossing the High Bridge over the Kentucky River. The fourth — a photo of a Corinthian-columned university building — resembles a plantation frontage providing a visual complement to the text printed above it: “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn” (Rhett Butler, Gone with the Wind, the movie). “Coloring” the work as a recollection of growing up in the South, all of the images appear to have been scribbled over with a child’s crayon, as if they had been in a grandparent’s keepsake album. In keeping with that echo is the following anecdote.

At an annual camp meeting, King’s grandmother and her friends are rocking away on the front porch and discussing “whether or not, and how much they would cry at one another’s funerals”. King sadly notes the reality of her grandmother’s last wish — “to be buried in a wine red dress” — being denied and that “as the pictures of the open casket show, she was allowed to pass from this world to the next in something more subdued and suitable”. Those photos are not in the book, just that reference. Nothing so macabre finds its way into Lessons from the South. But between that anecdote and the photo of the plantation-style building, a discomfiting list of words and phrases runs down the accordion spine’s cutout tab to which the anecdote page is attached: “Black Magic / Blackface / Black Humor / Black Belt / Black Mammy / Blackberry / Blackball / Black Sheep / Black Widow / Black Boy”. The list juxtaposed with the anecdote about her grandmother’s “open casket” might suggest prescience of the first episode of the documentary Eyes on the Prize, which aired on 21 January 1987 and revived the memory of Emmett Till’s open-casket photo.

The absence of anything that shocking in Lessons from the South underscores King’s observation: “As far as I can see, the glory of the Ole South is held close to the heart through its relics rather than its reality”. The dashing chivalry of Confederate generals, the white columns, clinging vines and that bittersweet nostalgia the South “doesn’t deserve” seem to block out the reality of that other open casket. The final words of Lessons from the South — “In this effort to remember our past and re-invent ourselves” — seem a rueful fan flutter toward a reality with which King does not confront us. What would a more daring and intense work look like? Can a white Southerner — any white person for that matter — create an autobiographical artist’s book that authentically addresses racism’s realities? Dr. Lisa Whittington’s comments seven years ago during the controversy over Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket offer some hope:

I don’t think it is wrong for a white person to paint Black subject matter. Art is a form of communication. Art gets people talking. Art documents mindsets and thought processes. But it has to be done responsibly, especially in this era of time. … racism is not a pretty or an easy topic to talk about let alone to paint a picture about it. It’s just not. But it is necessary because artwork can spark conversations that need to be had.

Coincidentally, seven years ago, Susan King returned to Kentucky, something she thought she “would never do” — a Grapes of Wrath in reverse as she puts it. On the journey home, she stopped in Memphis, Tennessee and visited the Civil Rights Museum, which incorporates both the façade of the Lorraine Motel where Dr. Martin Luther King was shot and James Earl Ray’s boarding house room from across the street. On her Paradise Press site’s blog, King recalls:

A woman stood on the other side of the street protesting the museum. I walked over to talk to her. She thinks black kids shouldn’t be taught their history. It is too painful. She wants the museum moved and low income housing built. In her world, we somehow can’t have both.

For most baby boomers and those from an earlier generation, a walk through the museum is a painful reminder of the history of racism in this country. Much of that history we saw unfold as youngsters. Almost too much to bear.

Thirty-eight years on, Lessons from the South remains an outstanding work of book art. It encourages the fusion of craft and engineering with art that followed on from the democratic multiples in book art to challenge the anatomy of the book. Thirty-eight years on, it piques the male conscience and white conscience differently than it did at any intervening point. It encourages more works to do even more — more than almost bear it — to bear witness.

(Auto)biographical Writing and the Artists’ Book (1996)

(Auto)biographical Writing and the Artists’ Book (1996)

AbraCadaBrA No. 10

Alliance for Contemporary Book Arts and Susan E. King (ed.)

Softcover over saddle stitch with staples. H277 x W203 mm. 48 pages. Acquired from Rulon-Miller Books, 7 September 2023.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

For a few examples of (auto)biographical works in the Books On Books Collection, see Johanna Drucker, Scott McCarney

Further Reading

“Alphabets Alive! — Activism and Anti-Racism“. 19 July 2023. Books On Books Collection.

“Tia Blassingame“. 17 August 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Johanna Drucker“. 28 May 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Warren Lehrer“. 28 May 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Louise Levergneux“. 27 April 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Scott McCarney“. 26 February 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Clarissa Sligh“. 2 September 2020. Books On Books Collection.

Drucker, Johanna. 2012. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York: Granary Books.

Gleek, Charlie. “Centuries of Black Artists’ Books“, presented at “Black Bibliographia: Print/Culture/Art” conference at the Center for Material Culture Studies, University of Delaware, 27 April 2019, pp. 7-8. Accessed 20 July 2020.

Hampton, Henry. 1987. Eyes on the Prize. Boston: produced by Blackside and GBH; aired by PBS.

King, Susan. E. 1996. (Auto)biographical Writing and the Artists’ Book. Abracadabra, No. 10. Los Angeles: Center for Contemporary Book Arts & Alliance for Contemporary Book Arts. Contributions by Betsy Davids, Joan Lyons, Katherine Ng, Johanna Drucker, Terry Braunstein, Scott McCarney and Bonnie O’Connell. Most of the autobiographical otherness addressed in the issue comes from the feminist era. Aside from Katherine Ng’s contribution reflecting on the role of her Chinese-American heritage in her art, no other contribution picks up on this reality of race and “the other” in life and and book art then or before. Given that the issue has a review of Clarissa Sligh’s What’s Happening with Mama?, the absence is odd.

King, Susan Elizabeth, Paul Muhly, and Allwyn O’Mara. 1993. Treading the Maze : An Artist’s Book of Daze. Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press.

Rubin, A. S. 1995. “Reflections on the Death of Emmett Till“. Southern Cultures, 2(1), 45–66.

Whittington, Lisa. 26 March 2017. “#MuseumsSoWhite: Black Pain and Why Painting Emmett Till Matters“. NBC News Digital: Think. New York.