Now here’s a rare thing — a journal issue that requires a video to show the reader h0w to open it.

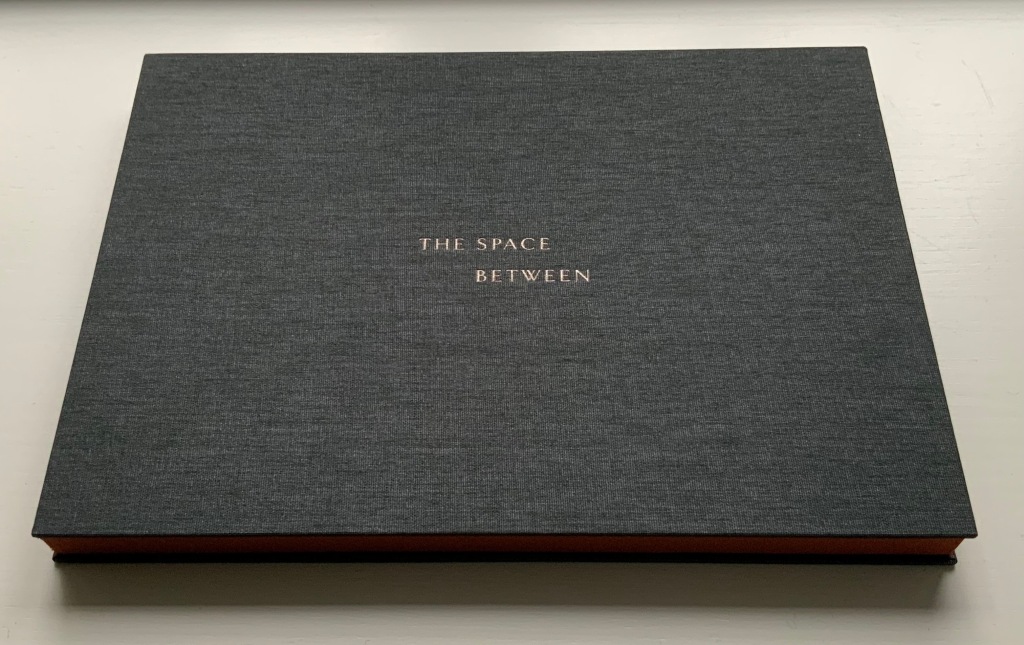

Inscription: The Journal of Material Text, Issue 3 on Folds

Simon Morris, Gill Partington and Adam Smyth (eds.)

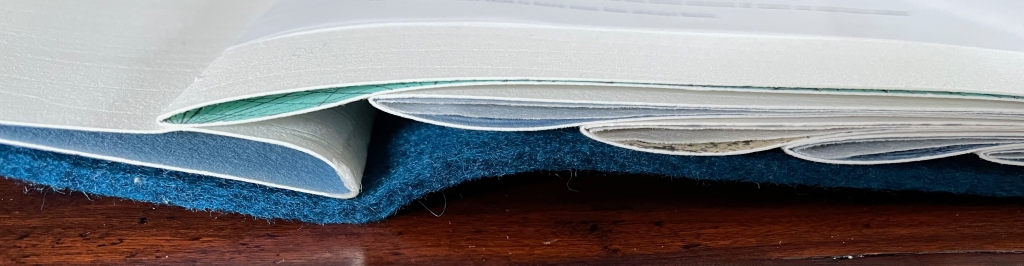

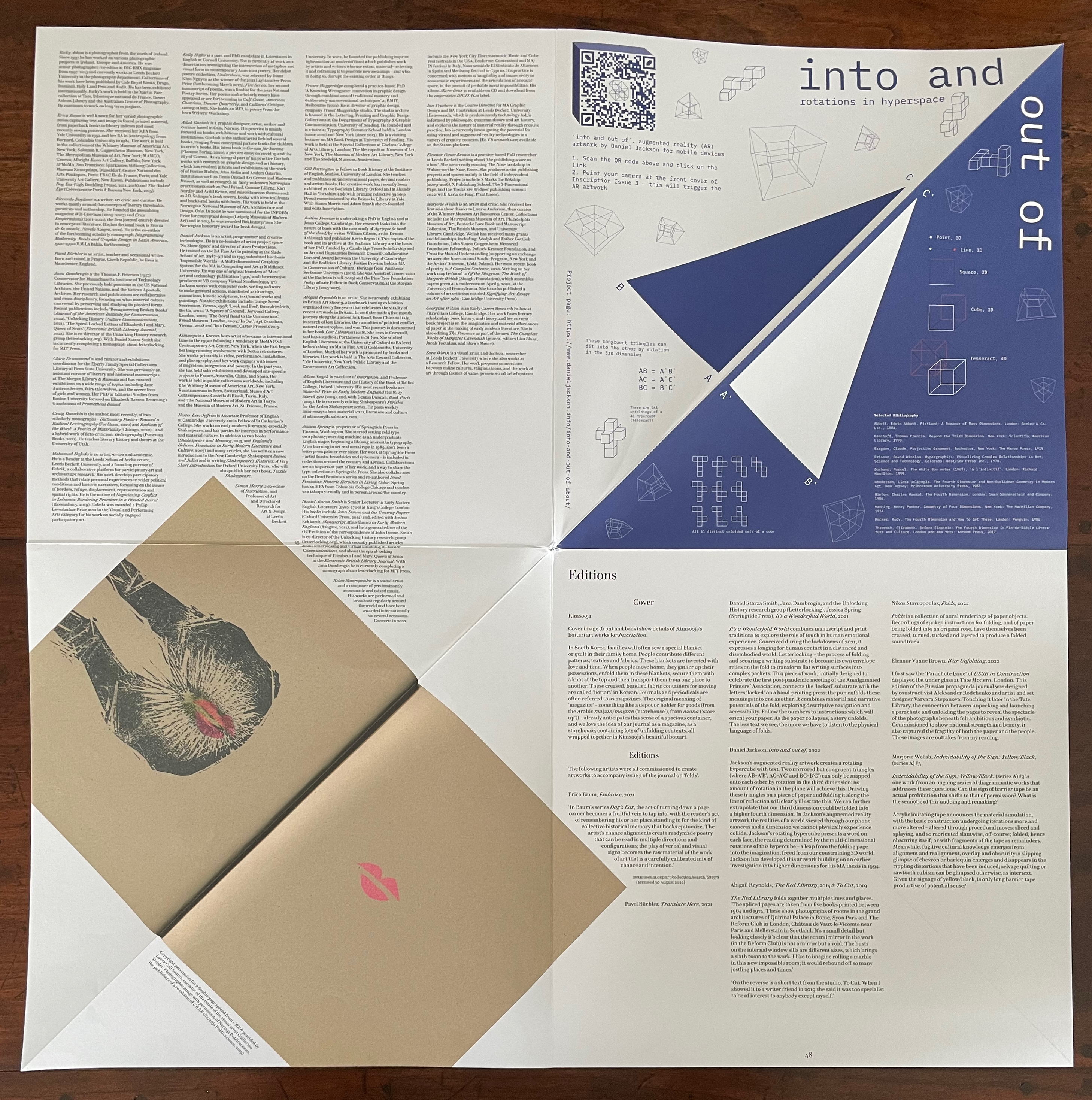

Printed boards over recurring origami square-base folded leaves. 300 x 300 mm. 120 pages. ISSN: 2634-7210. Acquired from Information as Material, 29 November 2022.

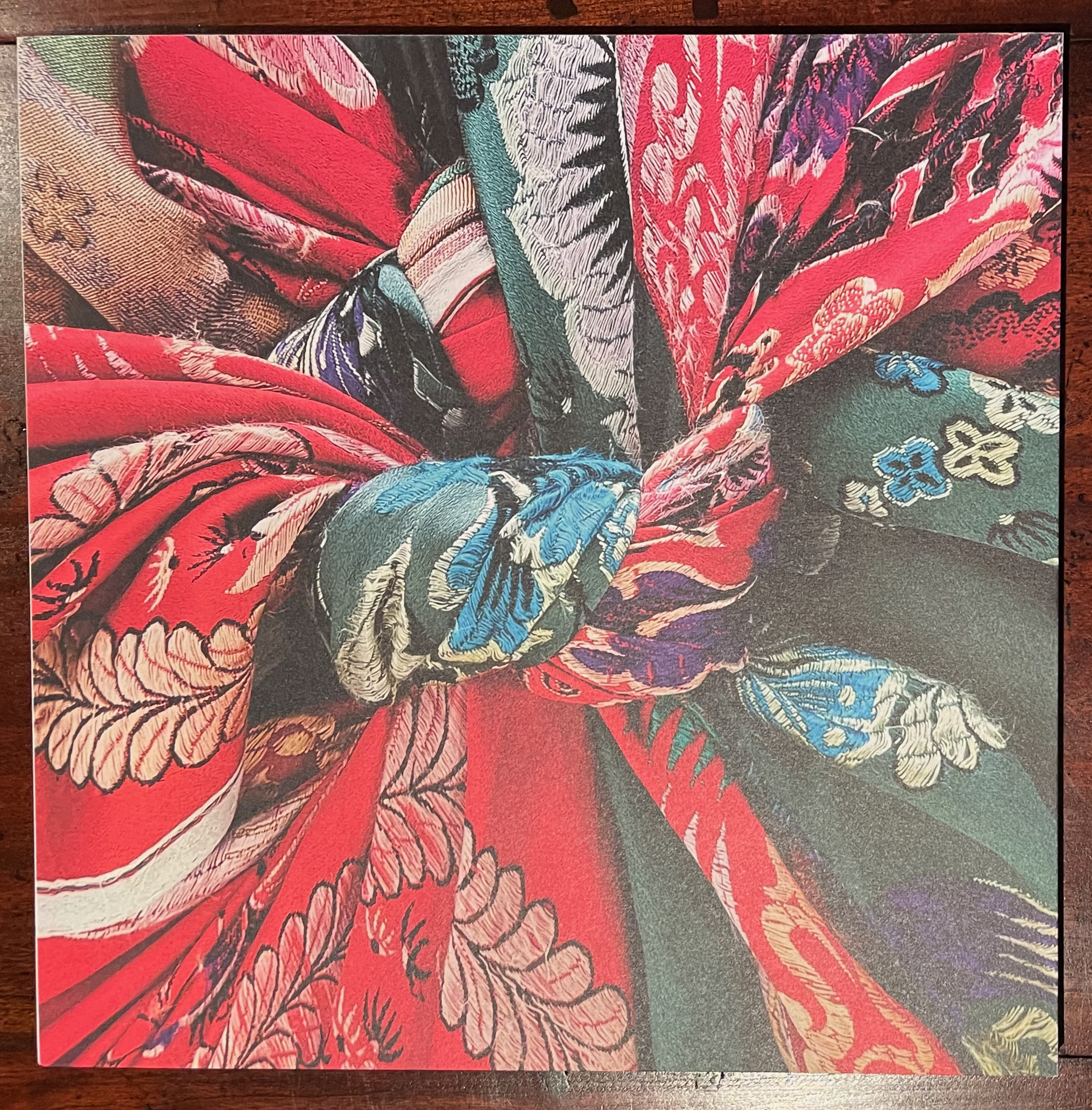

Photos: Books On Books Collection. [Front and back covers, Kimsooja’s bottari artwork commissioned for Inscription 3.]

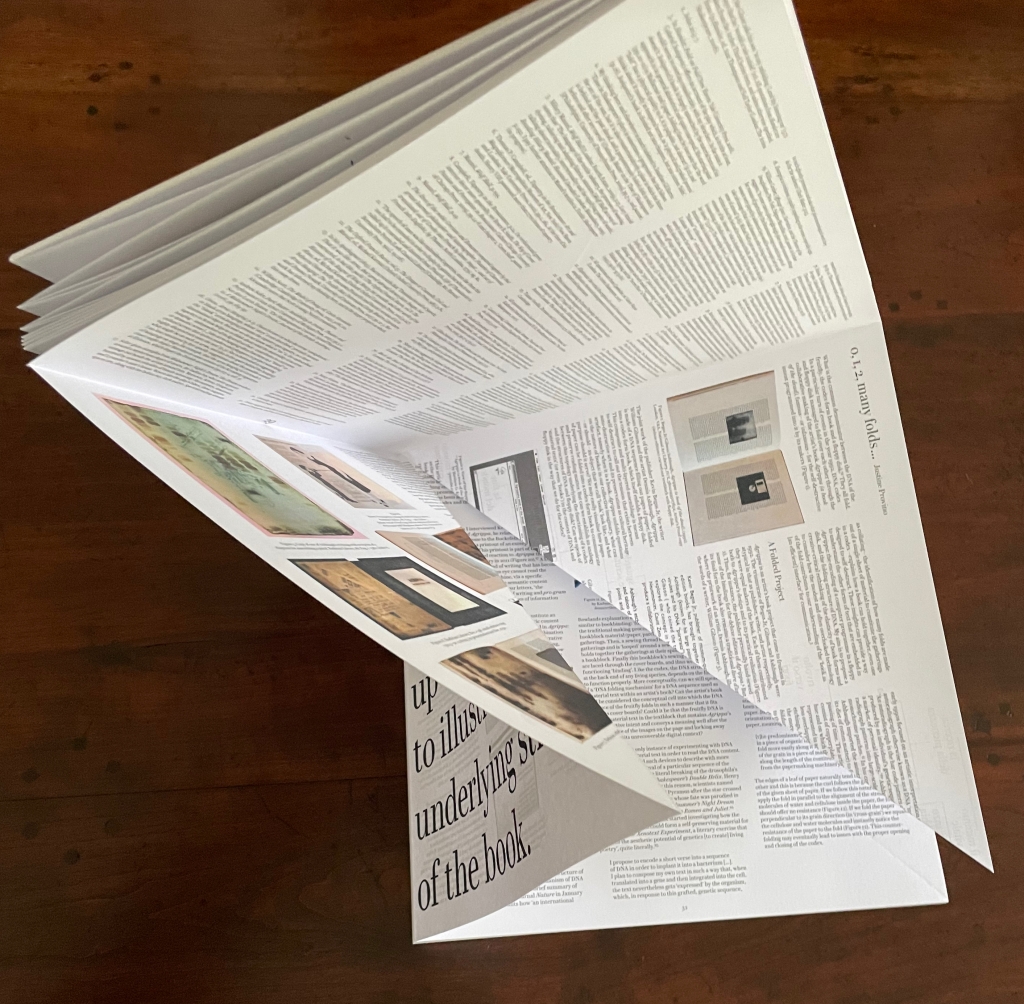

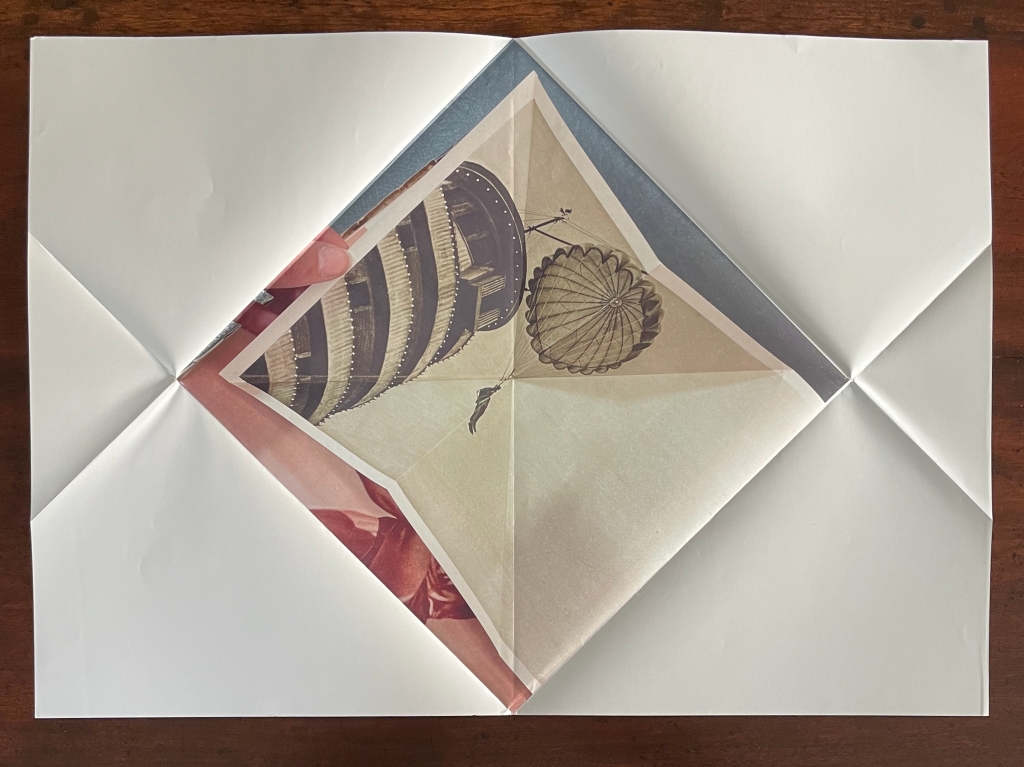

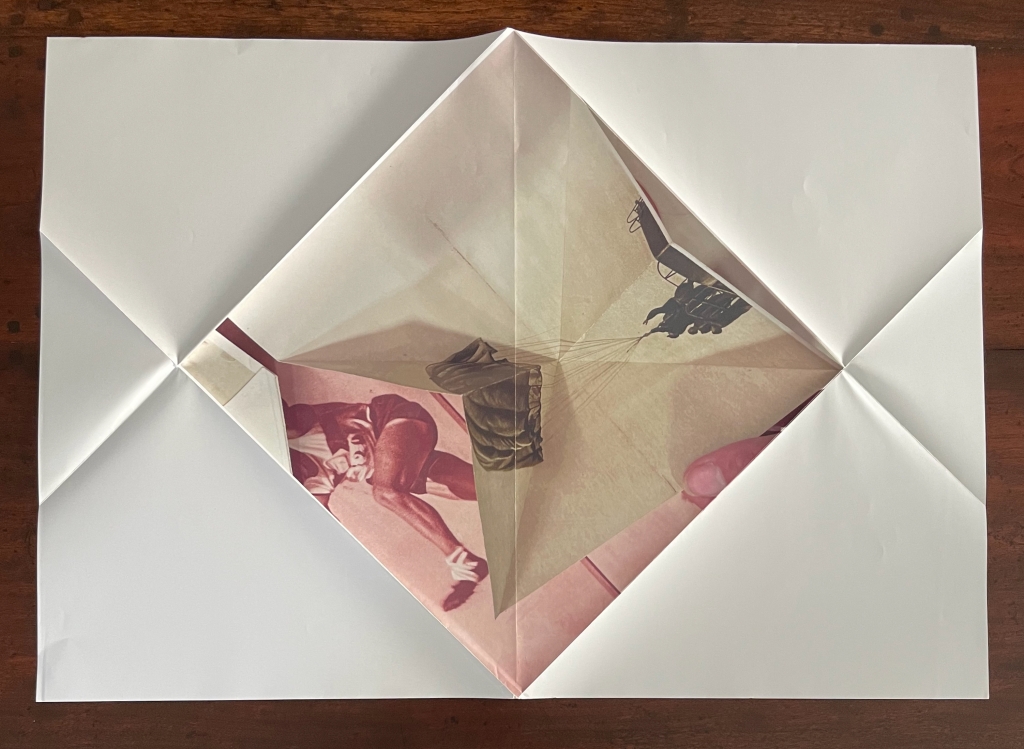

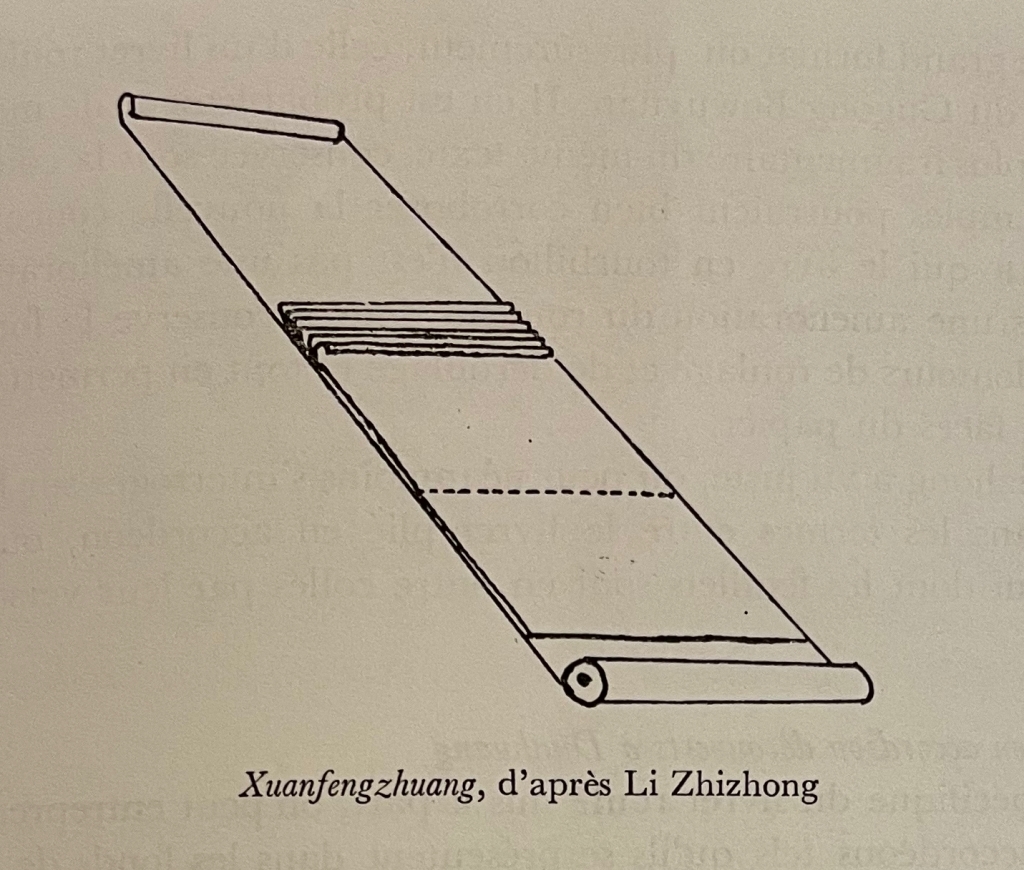

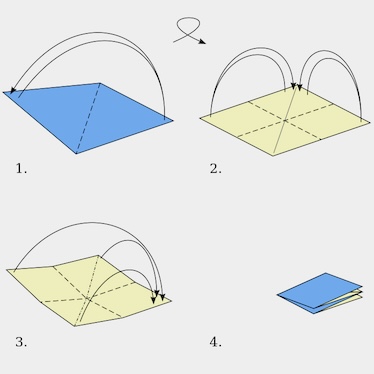

The structure is built on the simple principle of an origami square base. A diagonal mountain fold bisects two corners of a square, followed by two perpendicular valley folds bisecting the edges of the square; then the north, south and west corners come together and down atop the east corner. For the printer, the not-so-simple principle is how one base connects to the next to make a book!

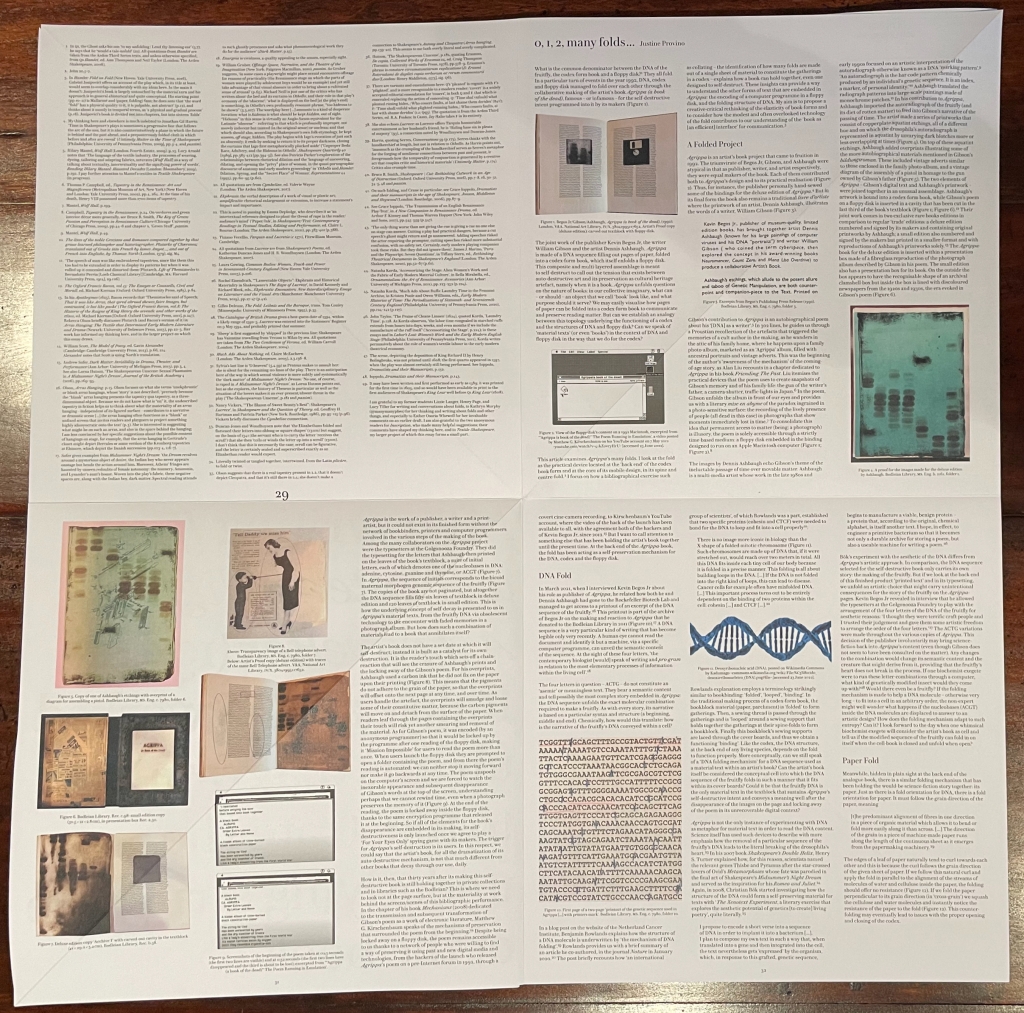

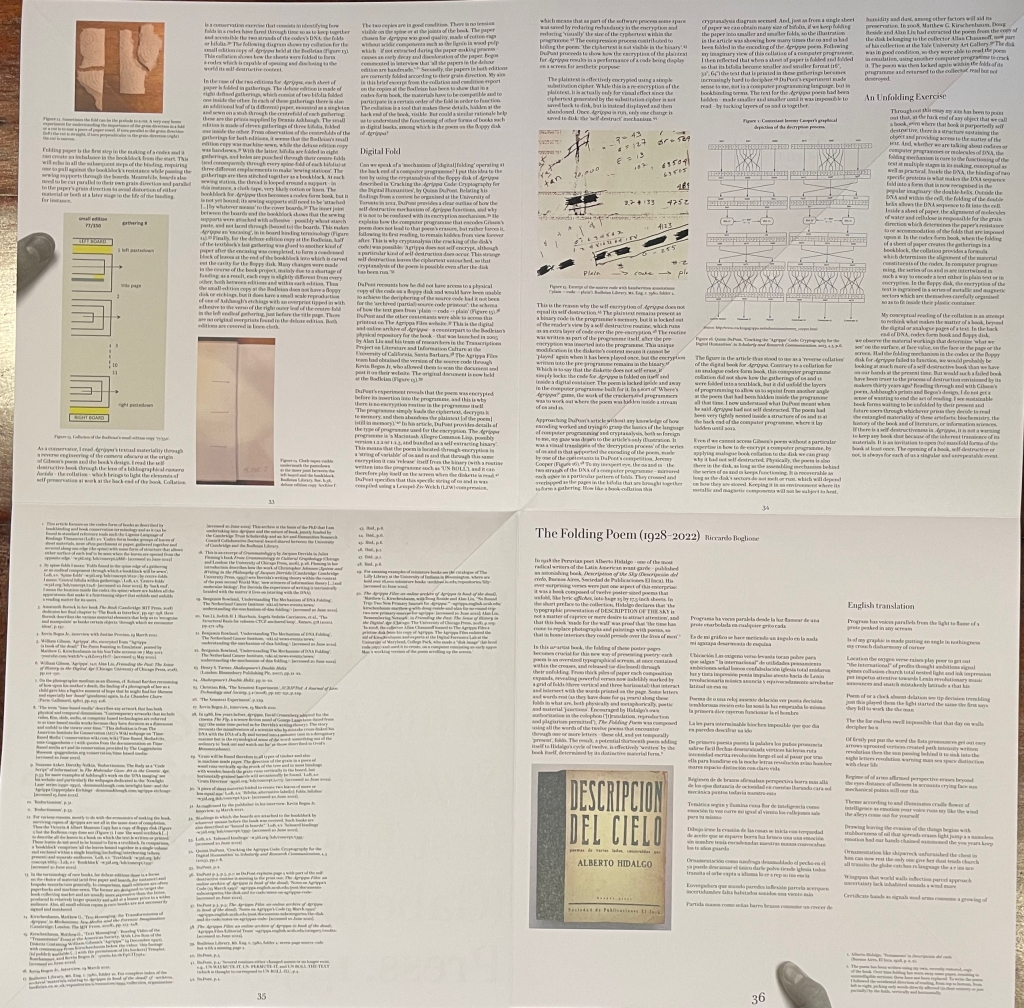

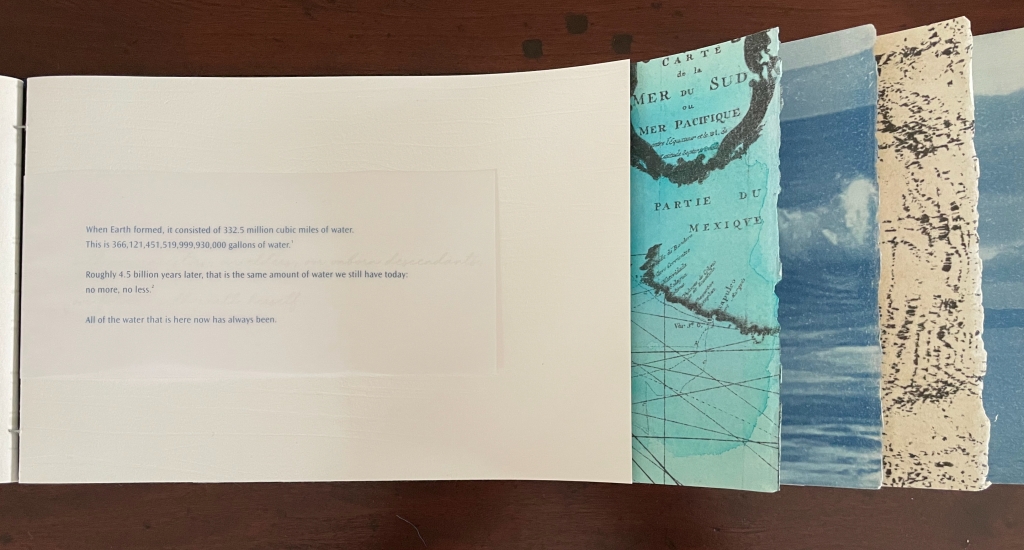

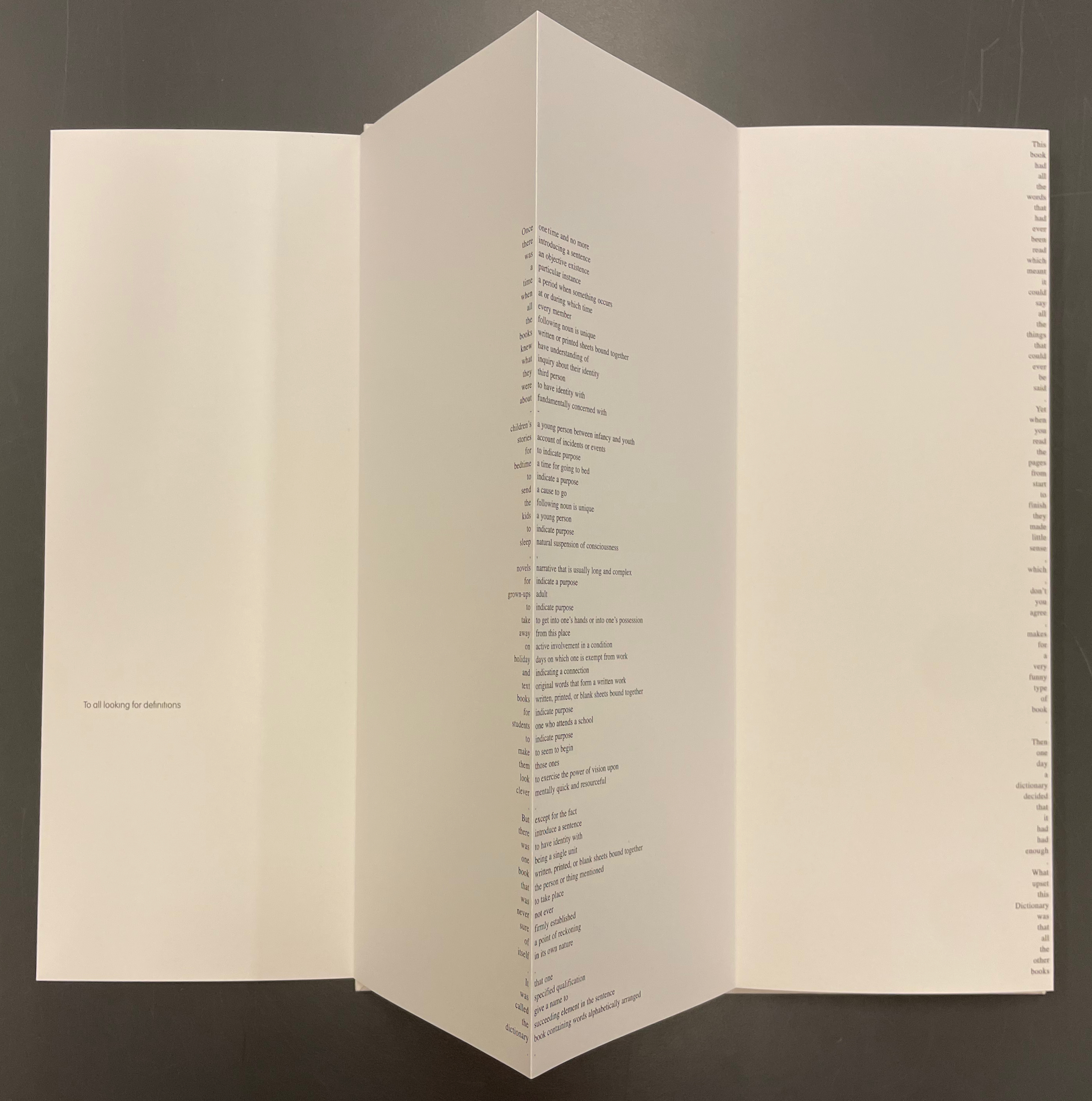

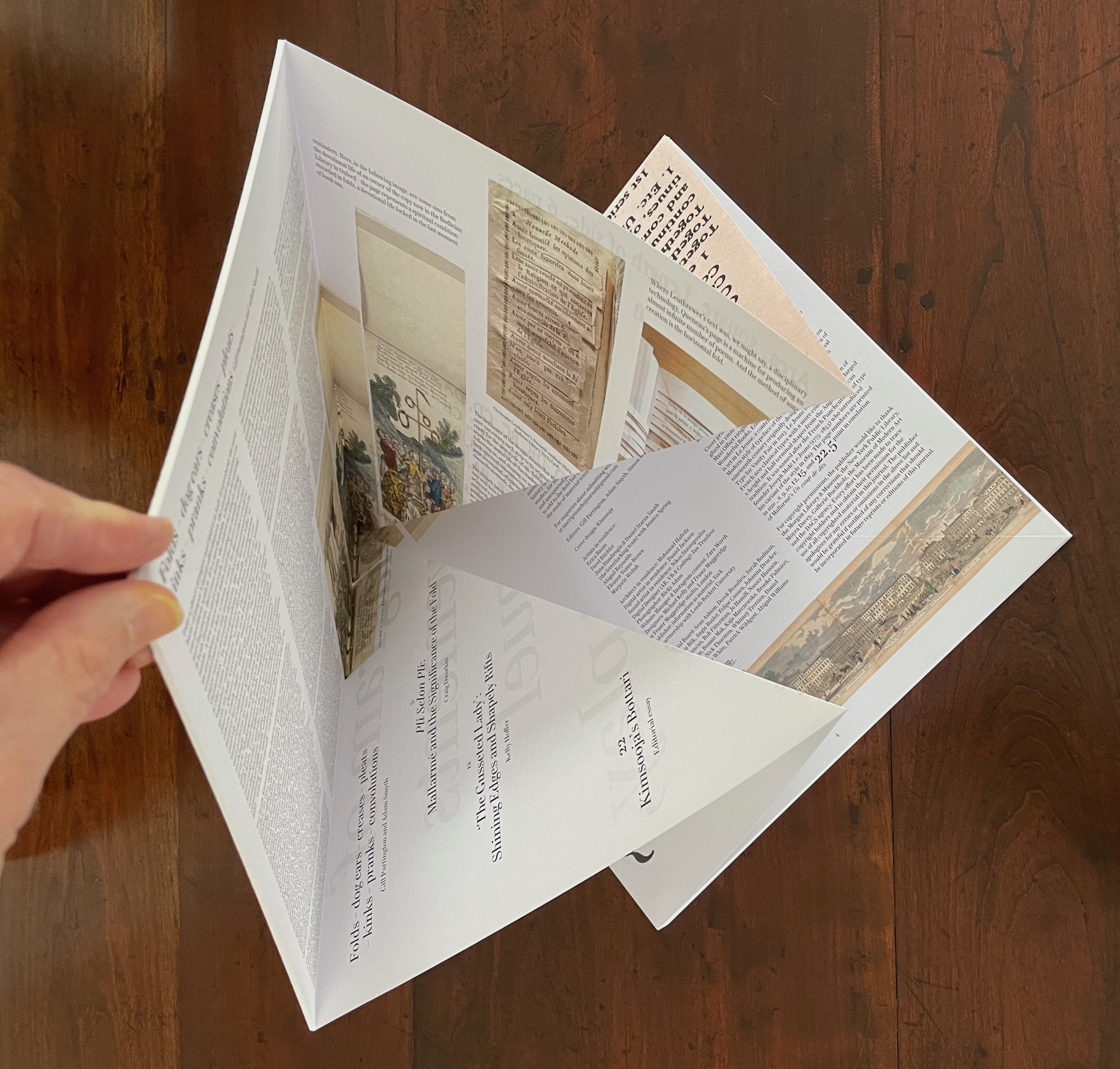

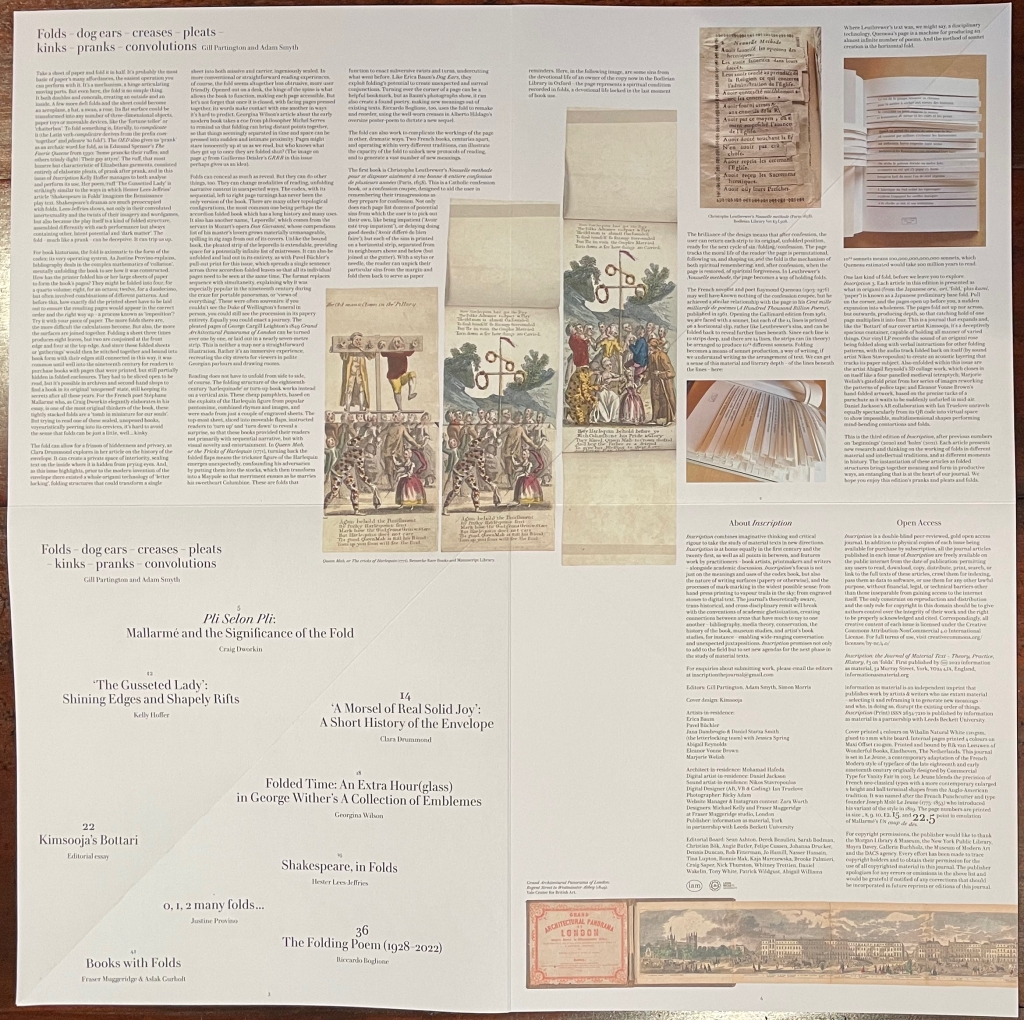

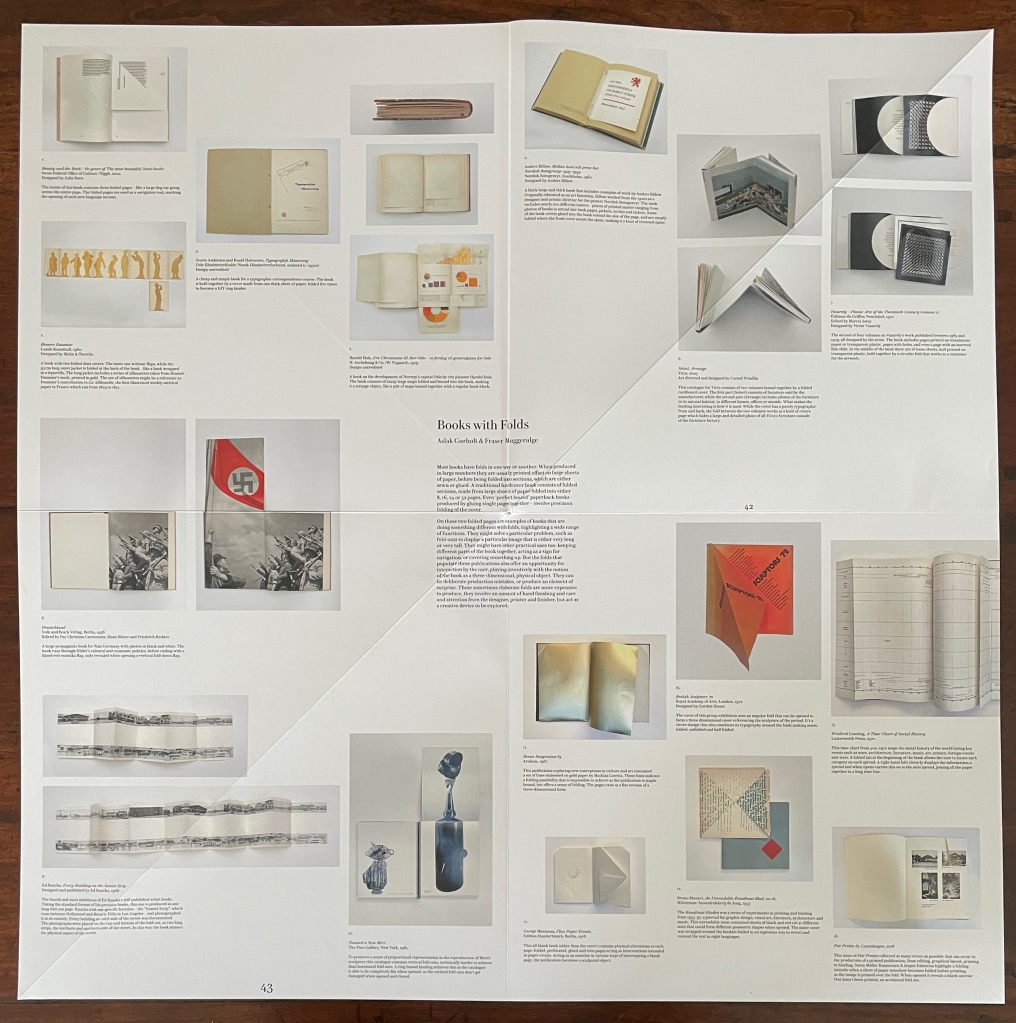

Inscription 3 has ten essays, including the editors’ introduction. As seen below, the latter neatly fits with the issue’s table of contents on a single unfolded sheet in a layout that offers considerable creative opportunities for structure and design to enact the theme of the issue.

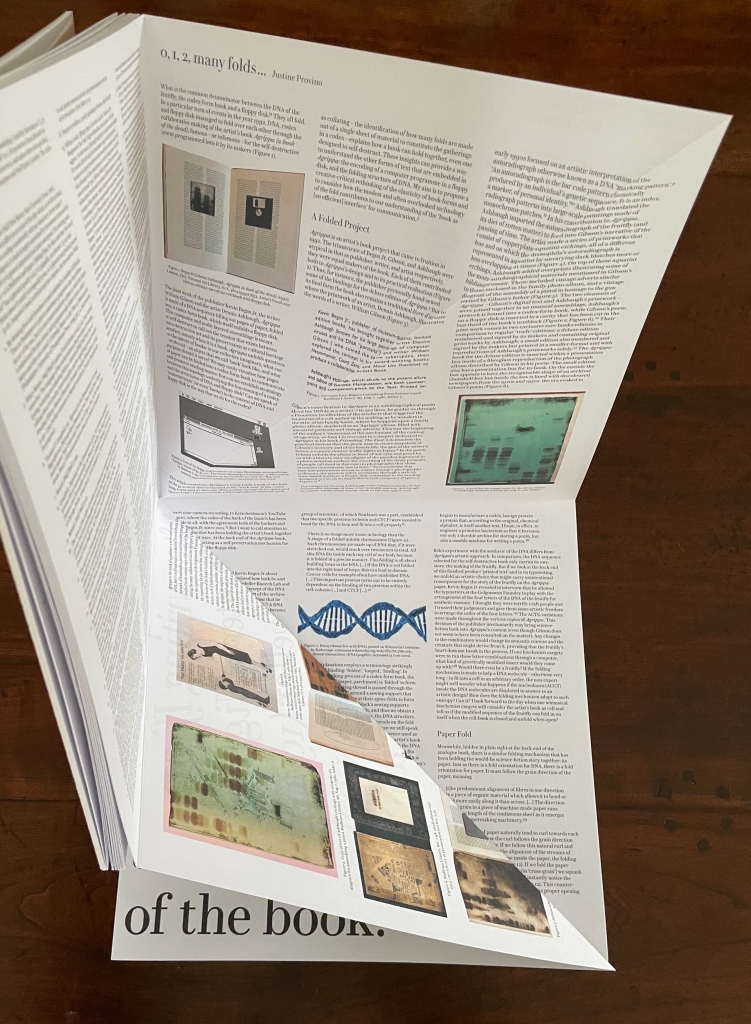

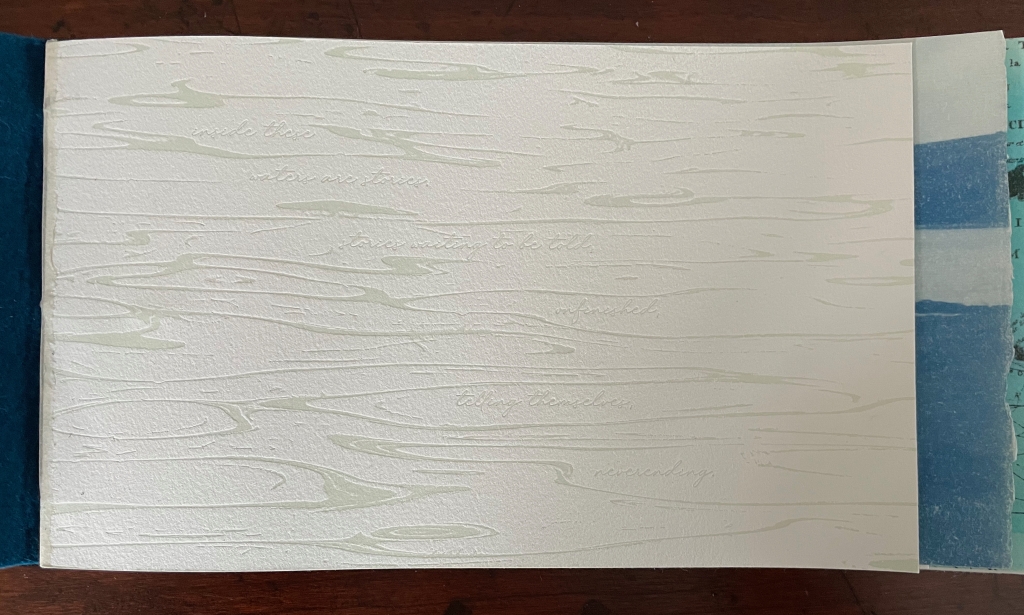

The essays fall across eleven of these large unfolded sheets, with a twelfth sheet serving for the contributors’ biographies and description of the nine commissioned artworks shrinkwrapped with this journal issue. In general, each unfolded sheet breaks down into quadrants, and each quadrant breaks down into three columns to accommodate text and images. The designers run images across columns, across the vertical and horizontal folds dividing the quadrants and, later on, even in alignment with the diagonal fold.

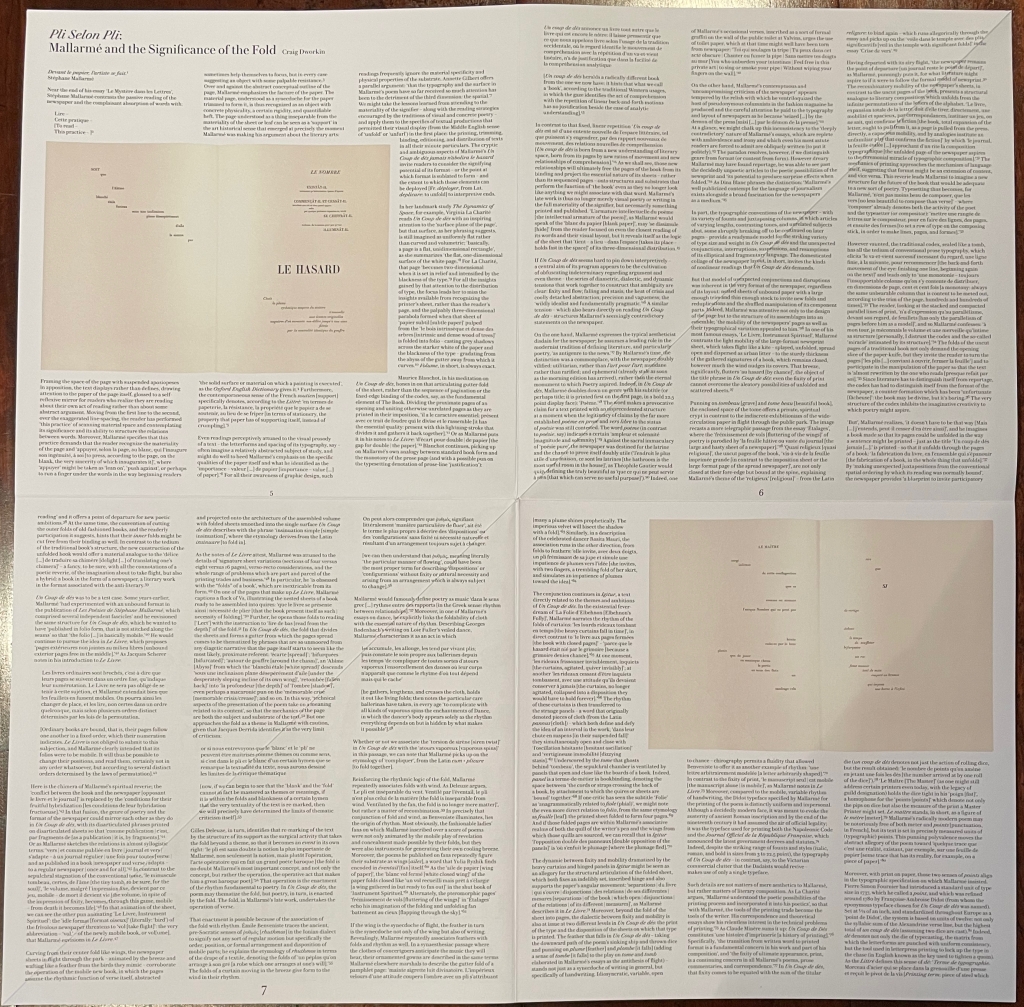

The structure and layout of Inscription 3 take the star billing in this issue and, to varying degrees, interact with the content. Two essays in particular highlight this. In the issue’s first contributed essay (see above), Craig Dworkin and the editors seem to have conspired to present an essay that enfolds its subject with the design of Incription 3. While Dworkin’s essay explores Stéphane Mallarmé’s efforts to reconcile his ideal of the Book with his ambivalent inspiration for it from the spaciousness of newspaper print, it has to be read across a sheet of book paper unfolded like a Sunday newspaper spread out on the dining room table. To reveal the end of the essay, the sheet of pages must rise, fold and unfold like the wings of a bird. Compare that with Dworkin’s description of Mallarmé’s imagined fusion of newspaper and book in which his landmark poem Un Coup de Dés should appear:

Curving from their center fold like wings, the newspaper sheets in flight through the park – animated by the breeze and wafting like a feather from the birds they mimic – corroborate the operation of the mobile new book, in which the pages assume the rhythmic function of verse itself, abstracted and projected onto the architecture of the assembled volume with folded sheets smoothed into the single surface Un Coup de dés describes with the phrase insinuation simple [simple insinuation], where the etymology derives from the Latin insinuare [to fold in].

The second example coinciding with Inscription 3‘s structure and layout is Justine Provino’s “0, 1, 2, many folds”, which explores an artist’s book just as abstruse semantically and physically as Mallarmé’s poem:

What is the common denominator between the DNA of the fruitfly, the codex-form book and a floppy disk? They all fold. In a particular turn of events in the year 1992, DNA, codex and floppy disk managed to fold over each other through the collaborative making of the artist’s book Agrippa (a book of the dead), famous – or infamous – for the self-destructive intent programmed into it by its makers …

Agrippa (a book of the dead) by Dennis Ashbaugh, Kevin Begos, Jr. and William Gibson incorporates each of these elements, as Provino creatively and critically explains, in ways that ask

… what can – or should – an object that we call ‘book’ look like, and what purpose should it serve? We may easily visualise how pages of paper can be folded into a codex-form book to communicate and preserve reading matter. But can we establish an analogy between this topology underlying the functioning of a codex and the structures of DNA and floppy disk? Can we speak of ‘material texts’ (or even ‘books’) in the context of DNA and floppy disk in the way that we do for the codex?

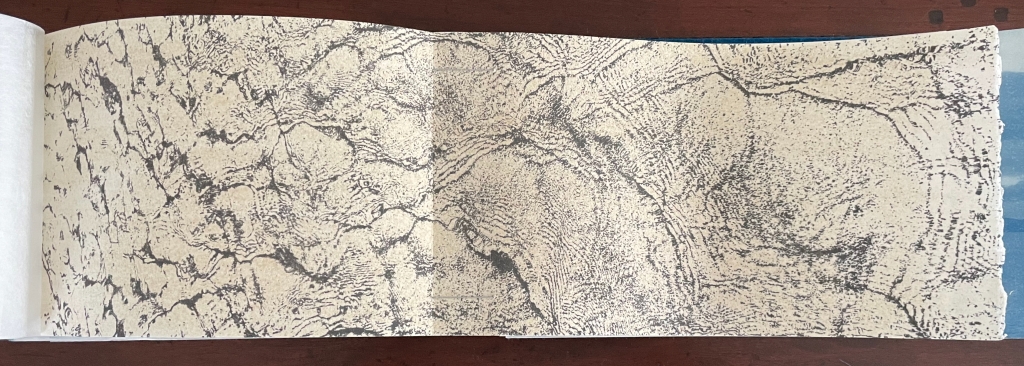

As soon as the double helix of DNA structure is raised, the reader turning the pages of Inscription 3 will surely have a frisson of recognition.

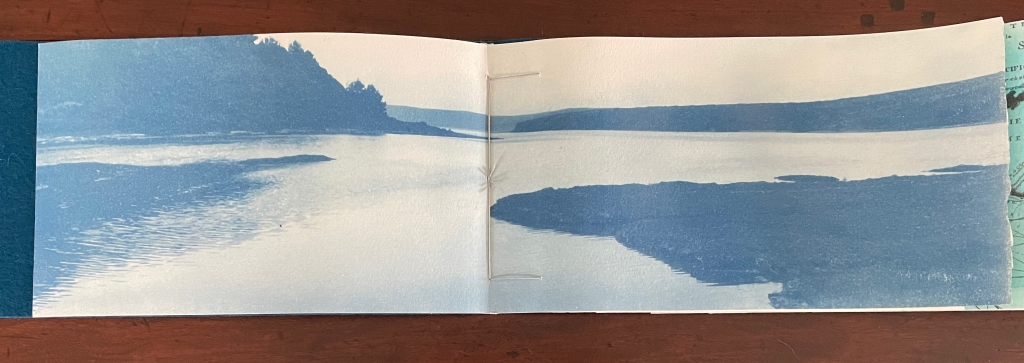

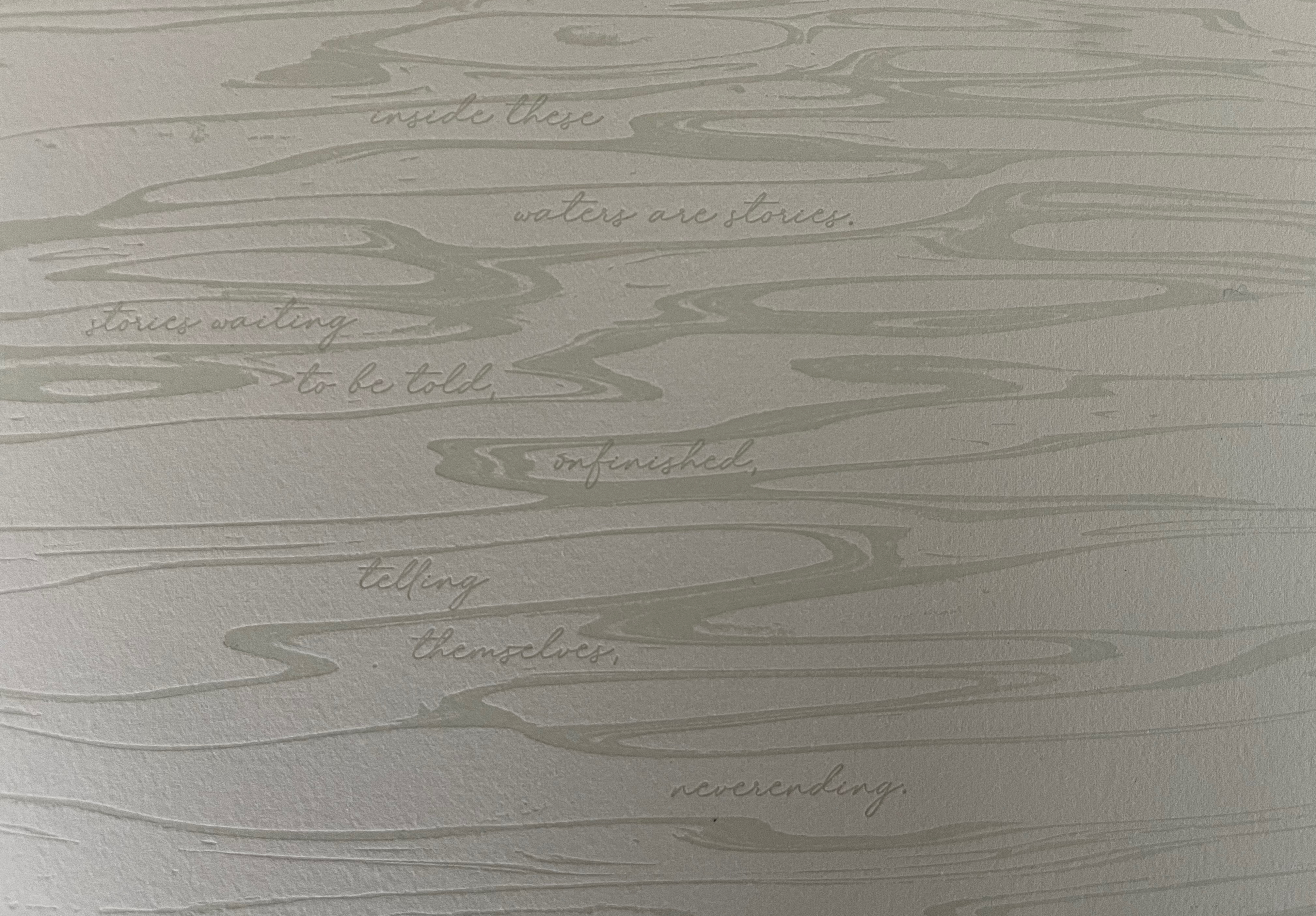

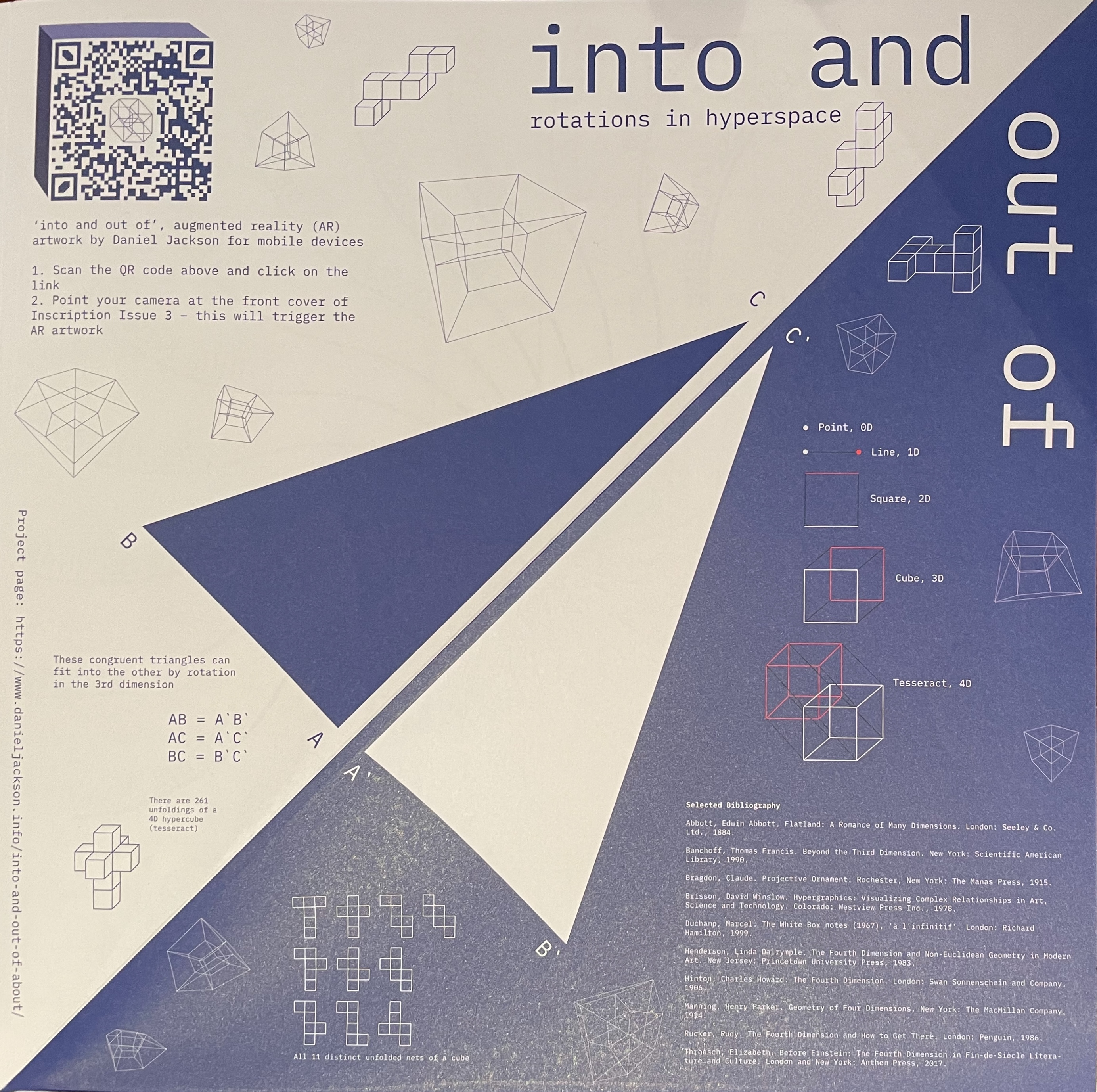

The skill with which the structure and layout enhances the essays’ content presents a challenge to the nine standalone works of commissioned art. They are individually delightful, but only Daniel Jackson’s into and out of integrates with Inscription 3 “physically”, and then only by virtue of its augmented reality nature that works when pointed at artist Kimsooja’s bottari fabric art commissioned for the front and back covers.

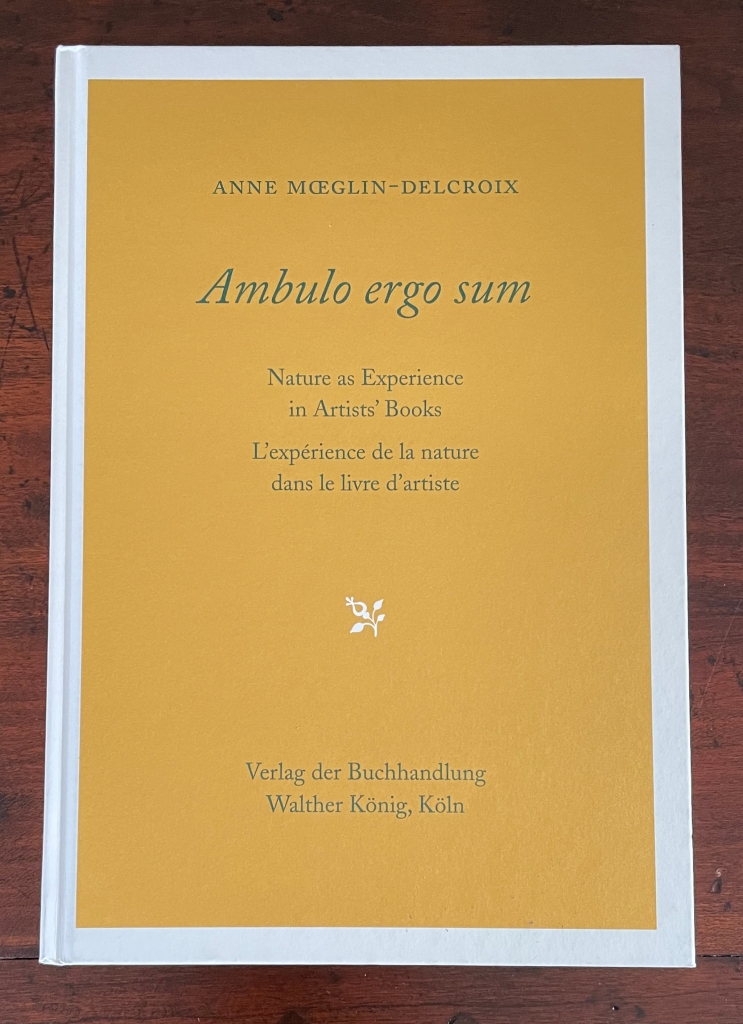

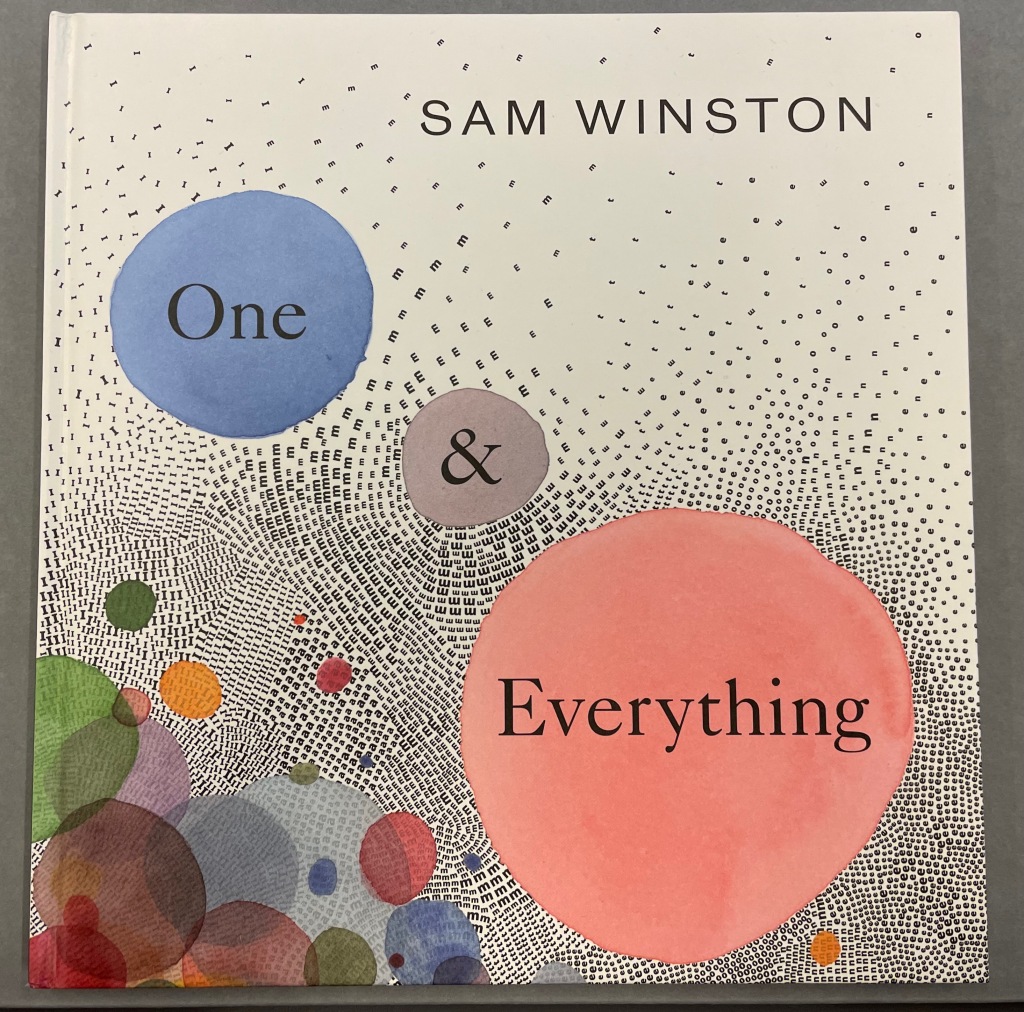

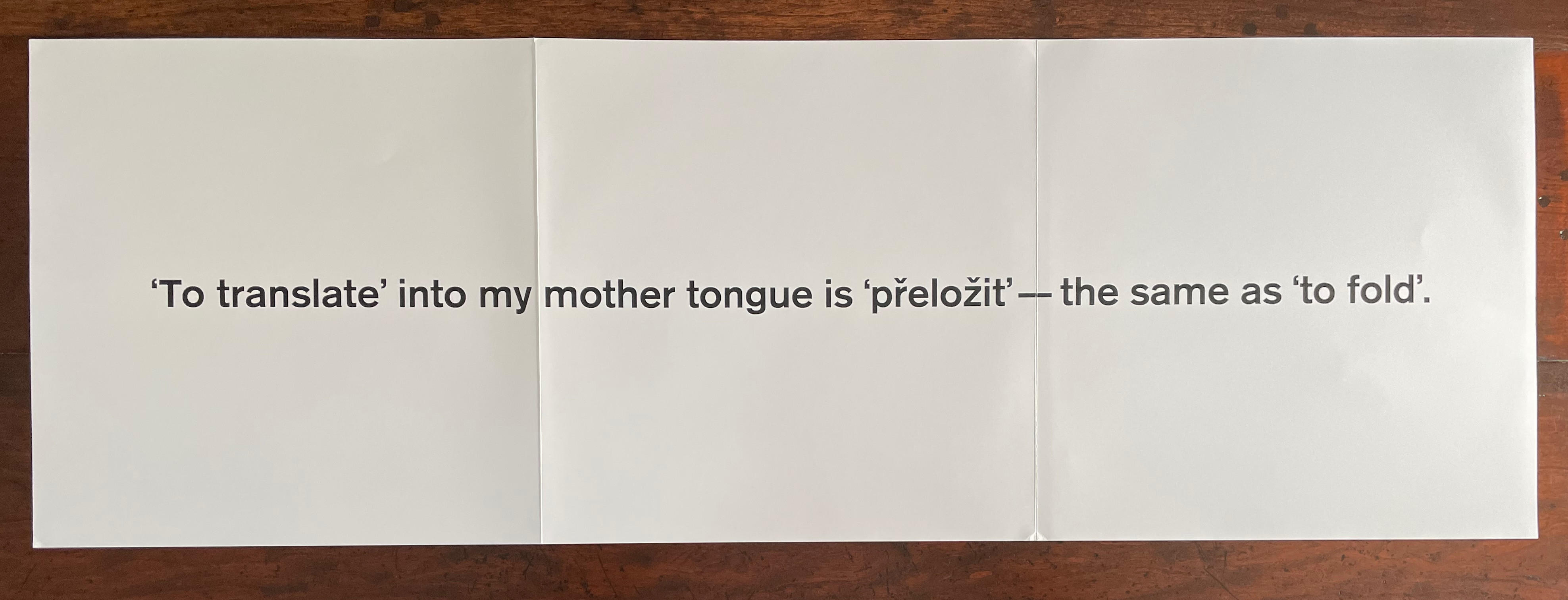

First row: Daniel Jackson, into and out of; Pavel Büchler, Translate Here. Second row: Rick Adams & Simon Morris, Less is More. Third row: Eleanor Vonne Brown, War Unfolding. Fourth row: Marjorie Welish, Indecidability of the Sign; Erica Baum, Embrace. Fifth row: Daniel Starza Smith, Jana Dambrogio, Jessica Spring, and the Unlocking History research group (Letterlocked), It’s a Wonderful World [self-enveloping letter]. Sixth row: Abigail Reynolds, The Red Library. Last row: Nikos Stavropoulos, Folds [vinyl LP record jacket and sleeve, sides A and B].

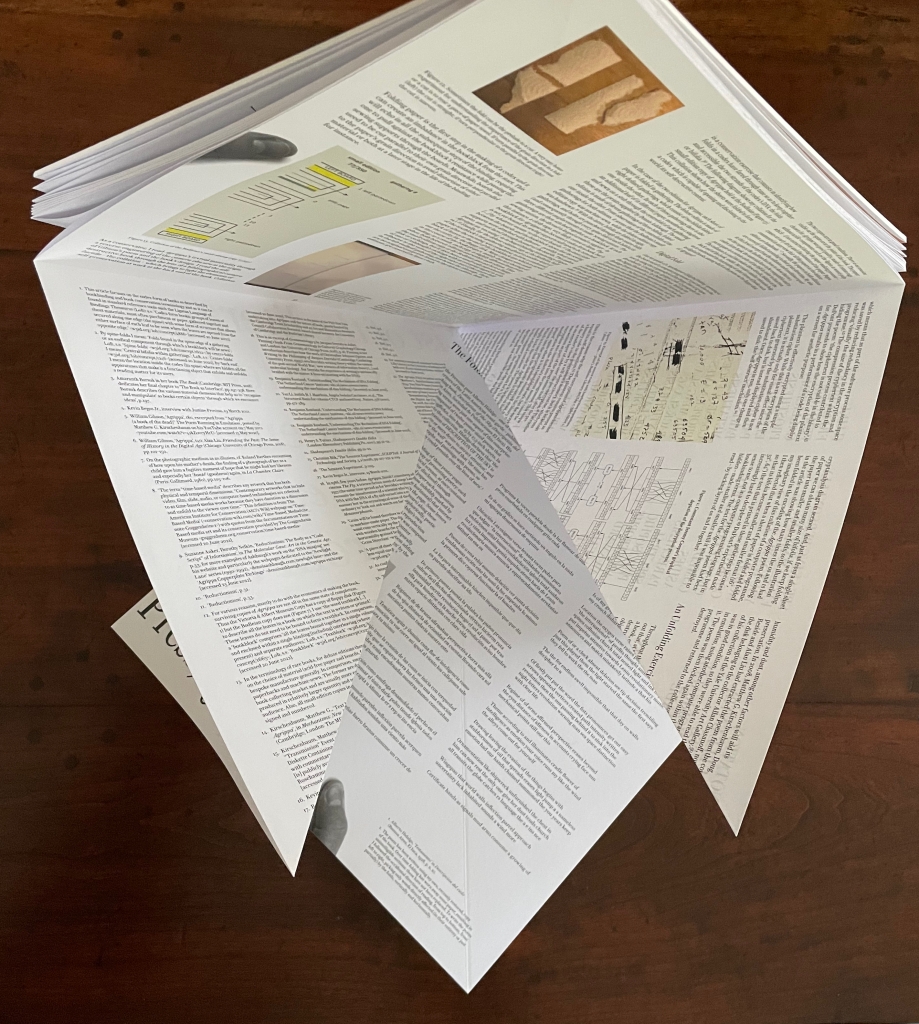

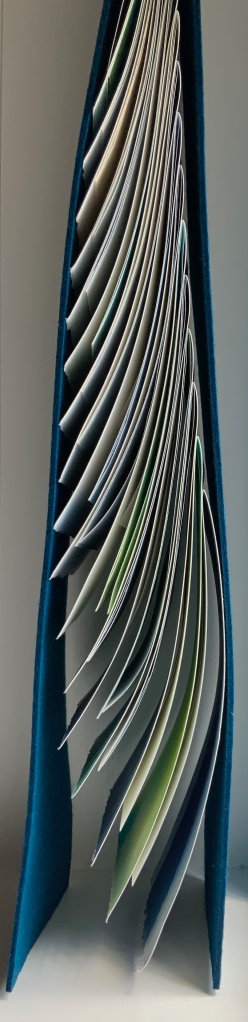

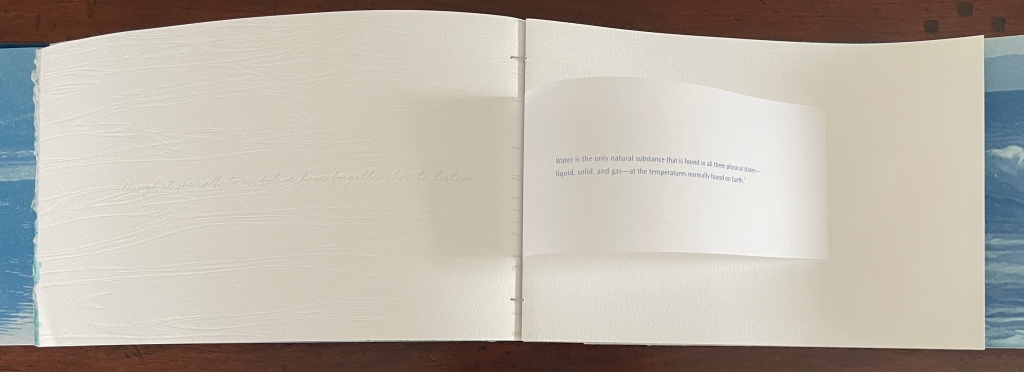

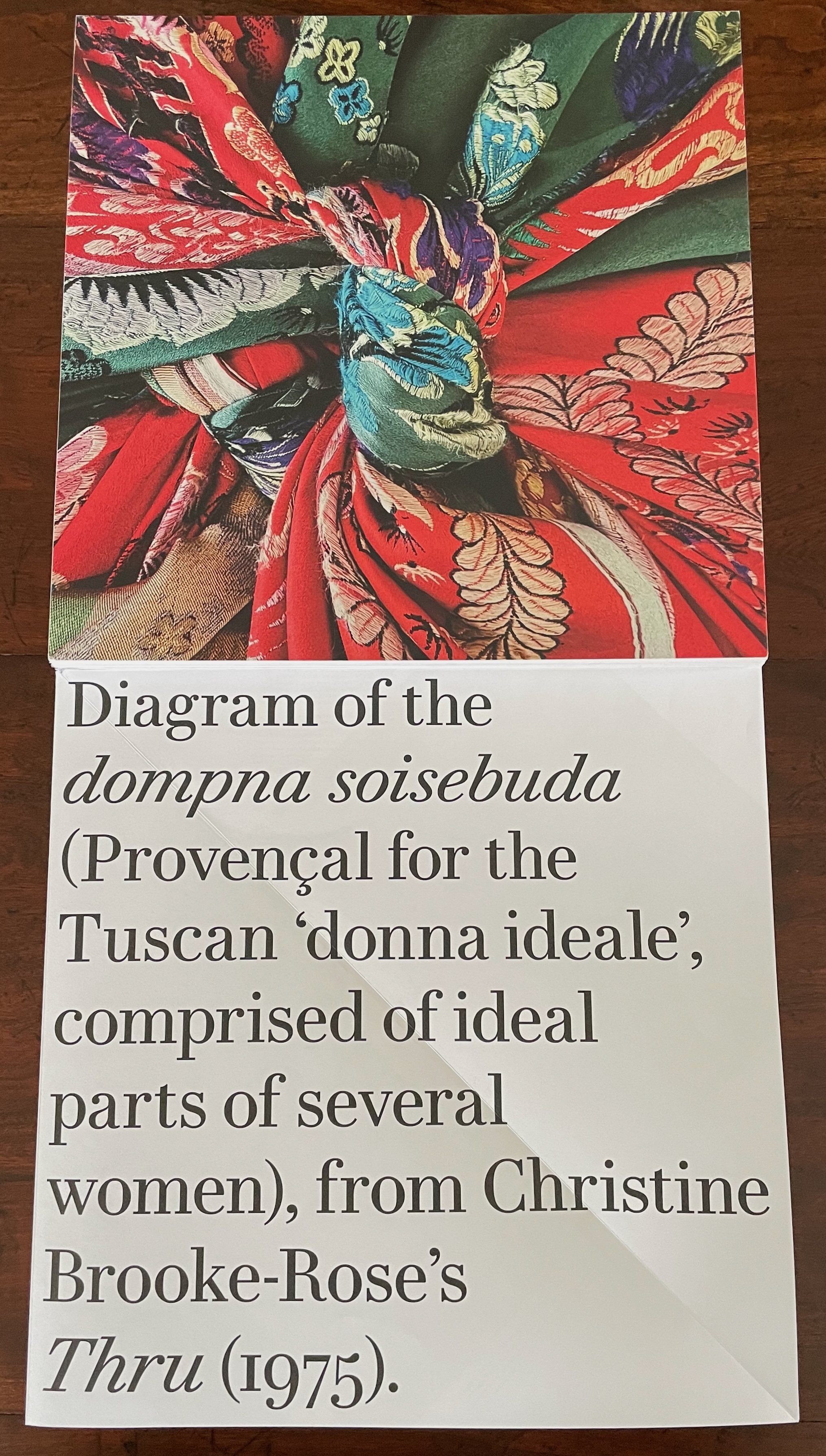

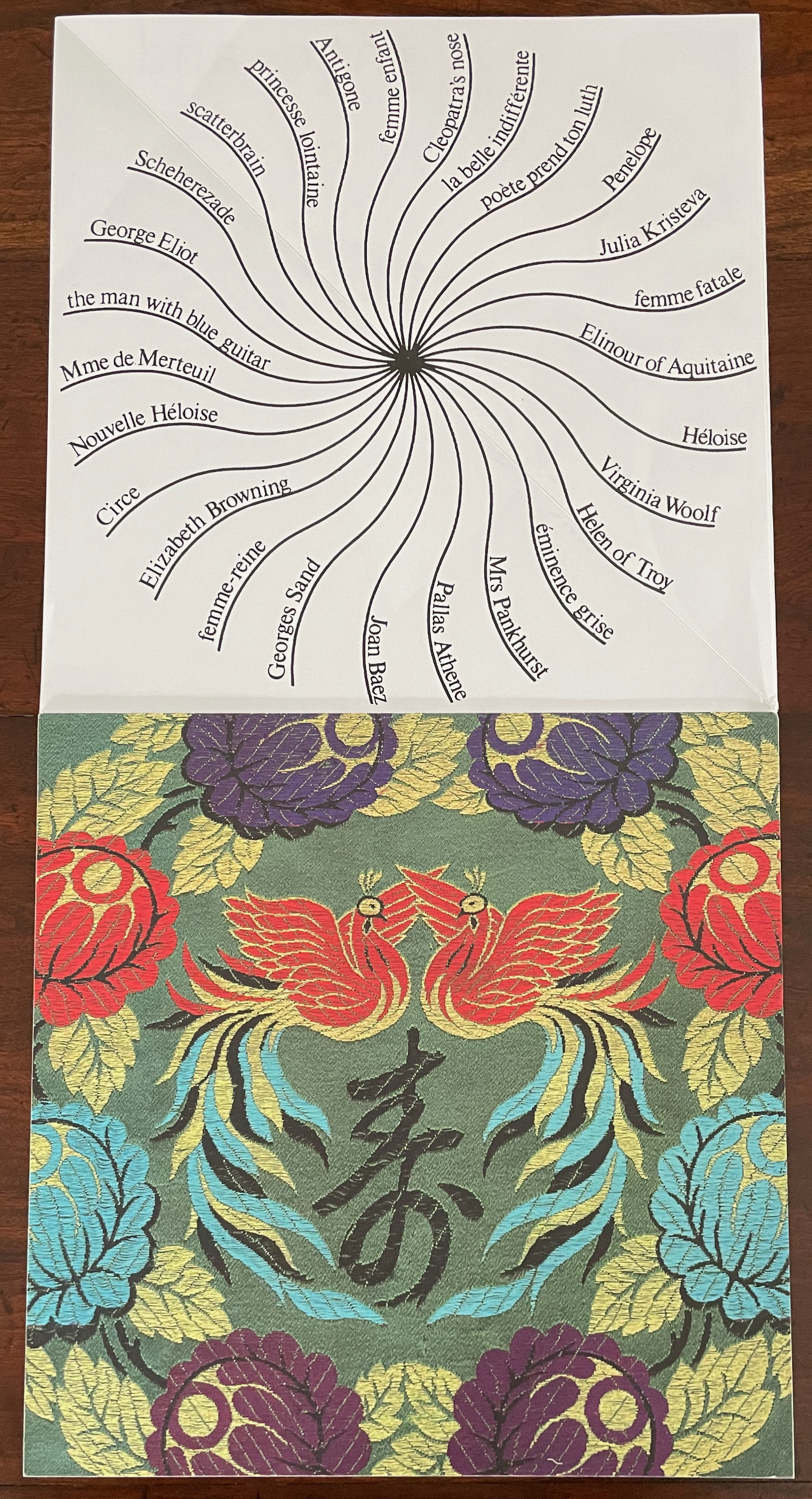

One more point about structure and a pointer for the reader. This issue manages to include twelve diptychs on the reverse of the twelve large unfolded sheets. Each diptych presents a figure, diagram or list on one half and a sizable corresponding label on the other half. Getting to them is the trick not explained in the video.

Top-down edge view of figures, diagrams and lists. How to see them and their labels?

With a large unfolded sheet in view, turn (carefully!) the left half to the right. There is the label below the front cover. Now turn the whole over. There is the figure, diagram or list above the back cover. The figures, diagrams and lists deal with works by Samuel Beckett, Stéphane Mallarmé, James Joyce, Laurence Sterne, Daniel Spoerri, Guillaume Apollinaire, Italo Calvino, Raymond Queneau and (below) Christine Brooke-Rose.

By the way, the large unfolded sheet above is the last of the twelve in Inscription 3. In addition to providing the biographies of the contributors and the list of nine commissioned artworks, it offers one more diagonal flourish from the designers. Call it a cheeky parting kiss.

Further Reading

“Inscription 1“. 15 October 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Inscription 2“. 29 May 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Inscription 4“. Books On Books Collection.

“Hedi Kyle’s The Art of the Fold: How to Make Innovative Books and Paper Structures (2018)“. Bookmarking Book Art.