Auparavant : Roman (1991)

Auparavant : Roman: Collection Voir Comme On Pense (1991)

Roland Sabatier

Jacketed softcover, exposed sewn & glued spine. H144 x W105 x D30 mm. 184 pages.Edition of 300. Acquired from Didier Lecointre et D. Drouet, 16 November 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

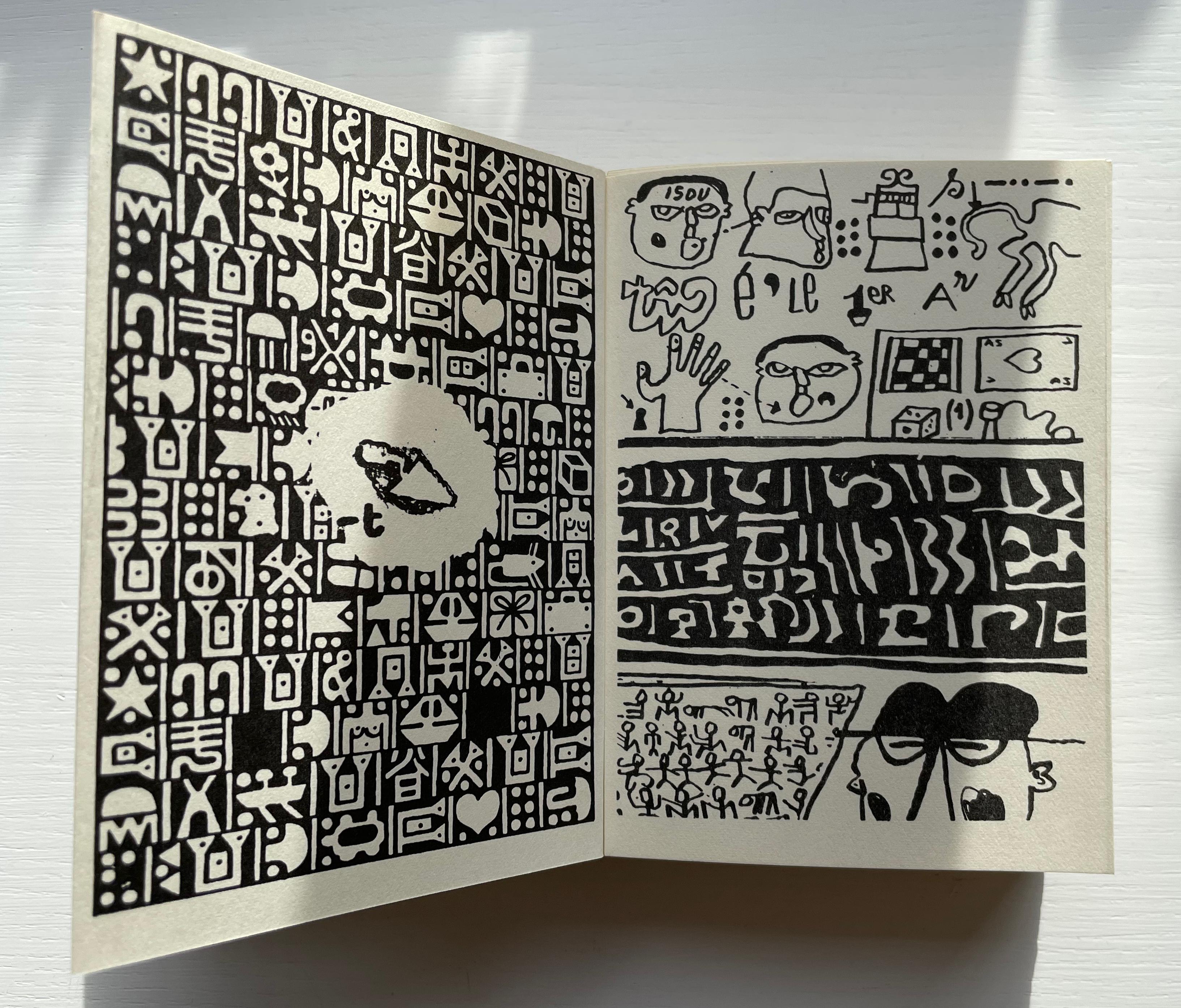

Sabatier’s work follows in the tradition of the Lettrists — Isidore Isou, Maurice Lemaître and Gabriel Pomerand — whose works Johanna Drucker addresses in the chapter “The Book as Verbal Exploration” of The Century of Artists’ Books (2004). Although much shorter (10 pages), Lemaître’s Roman Hypergraphique (1950) is the direct precursor to the lengthier Auparavant. Drucker’s comments on Lemaître’s booklet apply easily to Sabatier’s tome:

On one page… Lemaître arranged images of the solar system, planet earth, the continent of Europe, and other particulars in decreasing scale — ending the sequence with an image of himself. … Another page was composed of small drawings of objects meant to be read according to the resemblance between their shapes and that of letters. This was a painfully slow way to assemble words, but a reasonably successful way of blocking their easy translation into disembodied meaning. The ”letters” take so much deciphering that conventional reading is deferred. Another page used images as if they communicated sense directly – with a rising sun “meaning” the act of arising, a footstep indicating a trip, a line of waves a body of water, and so forth. Lemaitre was unperturbed by the indeterminate aspect of these images – or at least did not acknowledge them. In another image he used letters of the alphabet according to a set of substitutions and containing a buried key to their meaning. Graphically successful, Lemaitre considered this the best attempt he had made at a “mise en page hypergraphique” (or “hypergraphic page layout”). In other pages he made use of an invented phonetic alphabet, some classic images from the history of writing particularly non-alphabetic scripts, and any other graphic means he could muster. The result is highly worked, but almost completely unintelligible. (Drucker, pp. 229-30)

In his preface, Sabatier declares his allegiance to the hypergraphic tradition:

Auparavant se présente comme une narration hypergraphique, fondée sur la réunion unifiée de toutes les formes possibles de notations et d’écritures”. [“Auparavant presents itself as a hypergraphic narrative, based on the unified union of all possible forms of notation and writing.”]

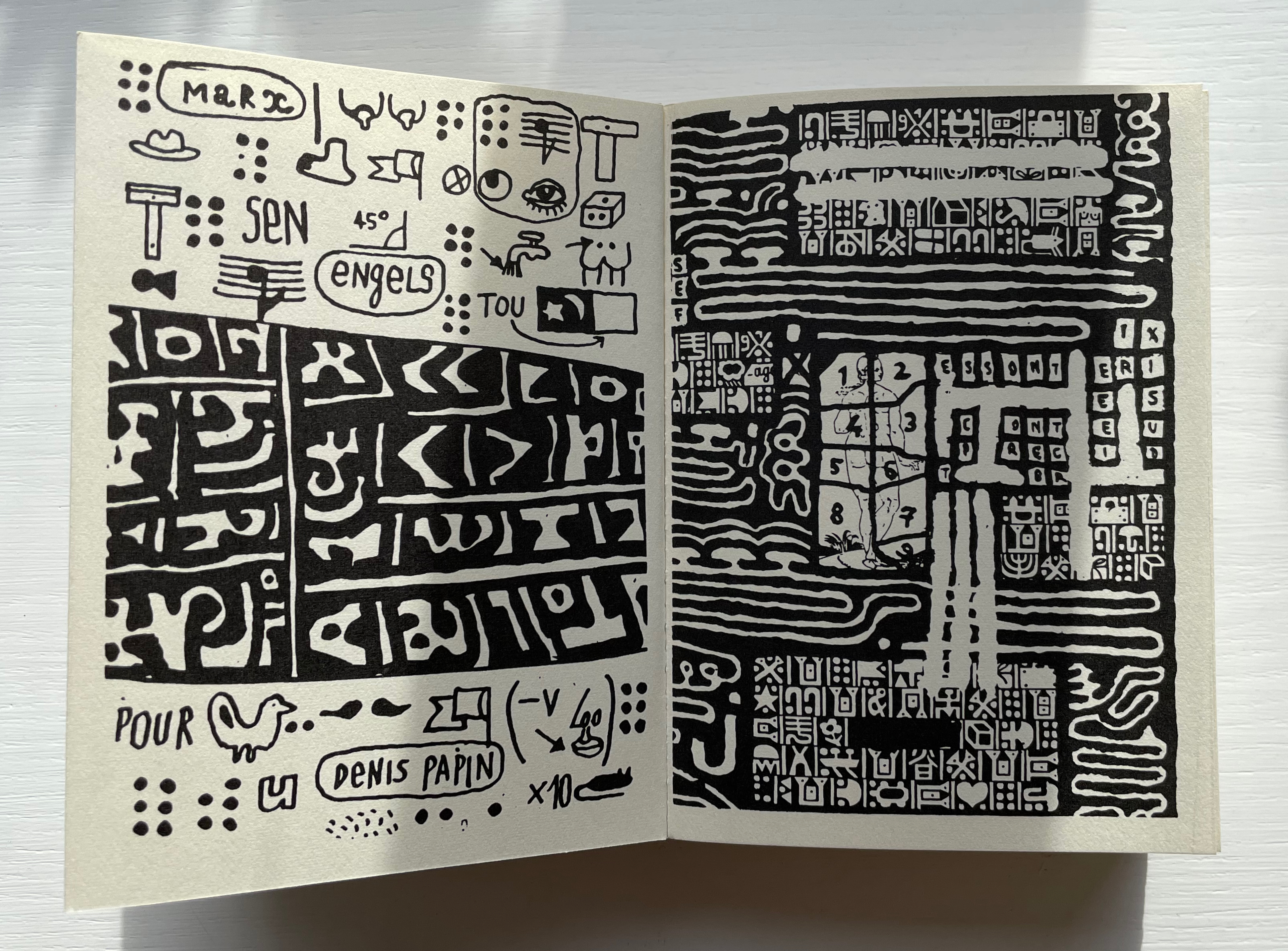

The word auparavant means “previously” or “before”, and there is much of the past in this hypergraphic narrative: Sabatier’s old ID cards, images of his previous works, drawings from earlier centuries’ books, and the names of eminent creators (Joyce, Débussy, Dégas, Socrates, Breton, Poe, Marx, Engels, Zola, Liebniz) in cartoon thought bubbles or scattered among other graphics.

Ce roman est le roman d’avant le roman: précisément, la fiction en prose qui s’interdit de se réaliser en tant que telle, du fait de la présence itérative de fragments de romans existants dont l’auteur ne parvient plus à se départir. [“This novel is the novel before the novel: specifically, prose fiction that refrains from realizing itself as such, due to the iterative presence of fragments of existing novels that the author can no longer part with.”]

This self-reflexivity differs from the physical self-reflexivity of the artists’ books whose shape or sequencing might be challenging the form of the codex. Here, the self-reflection is with the past of the avant-garde novel. So much so that it seems we are dealing with an arrière-avant-garde that Sabatier asserts does not contribute to elaborating future work but engulfs it and prevails over it. Hypergraphia becomes then a paradoxical coping mechanism:

Par les voies de “l’éloquence visuelle”, autant que de la suite ininterrompue de “belles pages”, l’oeuvre de l’écrivain et l’histoire du roman d’avant-garde se confondent pour s’imposer comme les sources aux-quelles, irrésistiblement, ce roman revient toujours.[“Through ‘visual eloquence’, as much as through the uninterrupted succession of ‘beautiful pages’, the work of the writer and the history of the avant-garde novel merge to impose themselves as the sources to which, irresistibly, this novel always returns.”]

Lemaître may end the map sequence in Roman Hypergraphique (1950) with an image of himself, but Sabatier begins and ends Auparavant with himself.

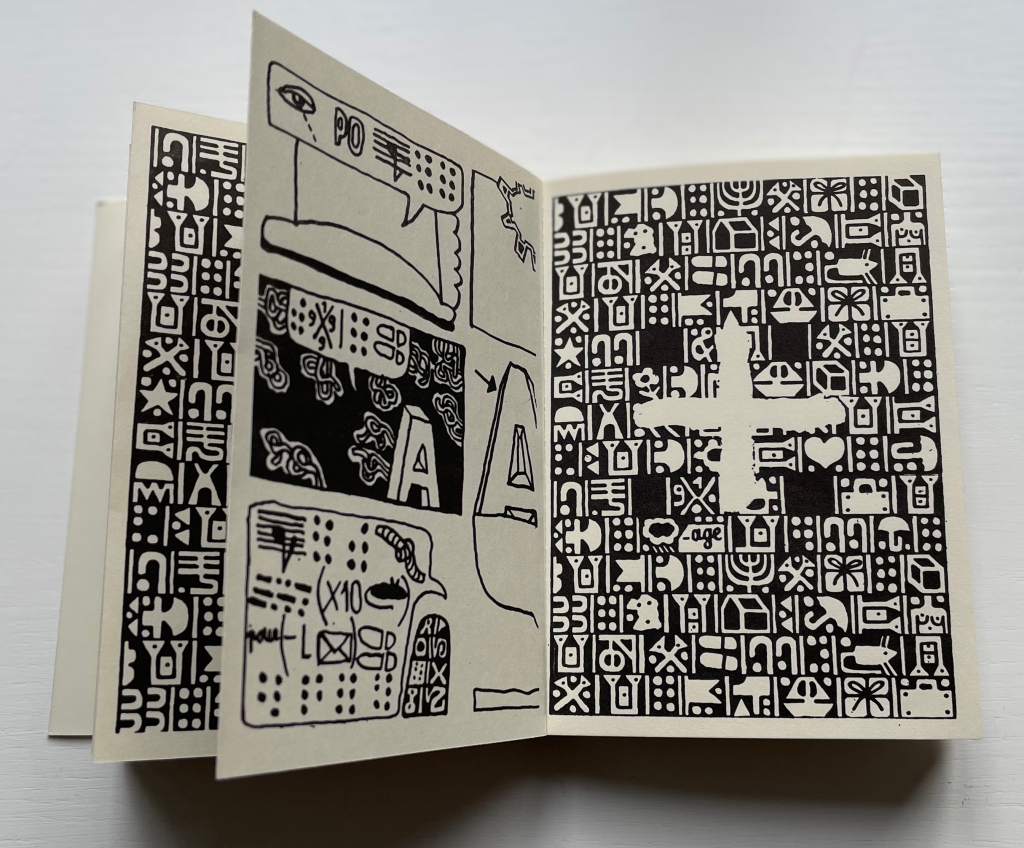

Entire lines of pictographs recur from page to page. In the seventh row from the top, the sequence of sunrise (or sunset) over mountains, followed by a tepee and then a canoe recurs throughout — sometimes in the same row, sometimes not.

Influencers of the past — Giotto, Eschyle (Aeschylus), Berlioz — confronting the novelist, or vice versa.

More influencers from the past: Isou (Isidore), Marx, Engels, Denis Papin.

The lower left may be easy to decipher for those fluent in French and rebus! The speech bubble contains a musical note (the solfège syllable la, the word meaning “the” in French), dice, a knot (noeud in French, pronounced ne indicating negation), ten mice, a lettre minus its l (suggesting être, for “to be”) and footsteps.

The image of Psyche with Cupid and the anatomical image recur throughout, often segmented differently.

Above, Drucker concluded about Lemaître’s hypergraphic novel, “The result is highly worked, but almost completely unintelligible”. With Sabatier’s Auparavant, “almost undecipherable” would be a more accurate phrase, and thinking of another artist whose work shows some affinity with the Lettrists, we can find two works with which to raise a question about the distinction. Whether the viewer is Chinese or Western, Book from the Sky (1991) by Xu Bing presents characters that are, in fact, unintelligible — intentionally so. For inhabitants of the late 20th and early 21st century, the logo- and emoticon-based characters in his Book from the Ground (2000) are — sometimes with difficulty — decipherable. Curiously though, the decipherable pages of Book from the Ground do not deliver the same quality that the unintelligible pages of Book from the Sky and the almost undecipherable pages of Auparavant deliver. Across this range of unintelligible to fully decipherable, it is the “uninterrupted succession of beautiful pages” that weighs most in the balance.

Further Reading

“Book from the Sky to Book from the Ground” by Xu Bing (2020)“. 21 January 2021. Bookmarking Book Art.

Caron, Anne-Catherine. “Le Roman” [“The Novel”]. Le Lettrisme: Les Théories du Lettrisme. Accessed 22 May 2024. A good source for more on hypergraphic narrative.

Drucker, Johanna. 2004. The Century of Artists’ Books [Second edition] ed. New York City: Granary Books.

Foster, Stephen C., ed. 1983. Lettrisme: Into the Future (Special Issue) Visible Language. 17:3.

Sabatier, Roland. 2010. “Introduction au Lettrisme“. Le Lettrisme: Les Théories du Lettrisme. Accessed 22 May 2024.

Sackner, Martin and Ruth. 2015. The Art of Typewriting : 570+ Illustrations. 2015. London: Thames & Hudson. P. 75.