Amorous Embrace (2023)

Amorous Embrace (2023)

Suzanne Moore and Titus Lucretius Carus (trans. A.E. Stallings)

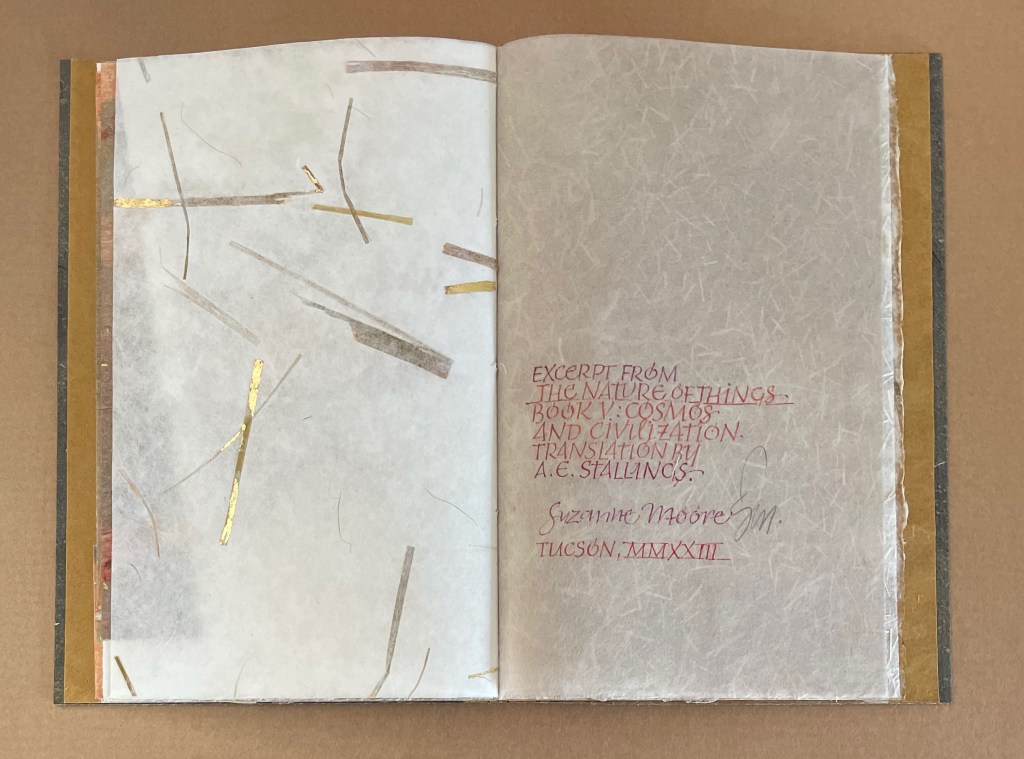

Artist’s manuscript, stub bound to stone cover, tinted thread, gold leaf, kozo, paste paper. H220 x W148 mm. 12 pages. Unique.

Acquired from the artist, 5 February 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Sometime in the first century BCE, the Roman poet Lucretius wrote the didactic epic De rerum natura (The Nature of Things). It celebrates the atomistic physics and philosophy that Epicurus and his followers recorded two hundred plus years before in thirty-seven volumes. Imagine the determination to press that Greek vision of the world from atoms to the cosmos into six volumes of Latin poetry. We’ll have to await further papyrology applied to the cinders of the Herculaneum library of scrolls and hope that it reveals more scraps of the Greek’s Περὶ φύσεως (On Nature). Only then will we know whether Lucretius based his poem directly on them.

In the meantime, wonder also that somehow …

— De rerum natura would survive for almost a millennium into the ninth century CE,

— five hundred or so years later only a handful of copies would exist in monasteries hundreds of miles apart,

— one Poggio Bracciolini travelling from Italy to Germany in 1418 would discover and acquire a complete one, and

— its contents would survive only as copied in the 1430s (Slattery, 2023).

Opening to one of the surviving mss of De rerum natura. Bodleian Libraries MS AUCT F 1 13 (1460)

Presumably then, most English translations of De rerum natura go back to Bracciolini’s copied copy. Here from the Bodleian Libraries are images of two of those translations. The earlier one comes from an anonymous prose translation dating no earlier than 1659 and no later than 1755. The later one comes from A.E. Stallings, the Oxford Professor of Poetry (2023-2027).

Anonymous, a prose translation of De rerum natura, from the Rawlinson Collection, Bodleian Libraries. MS. Rawl D. 314.

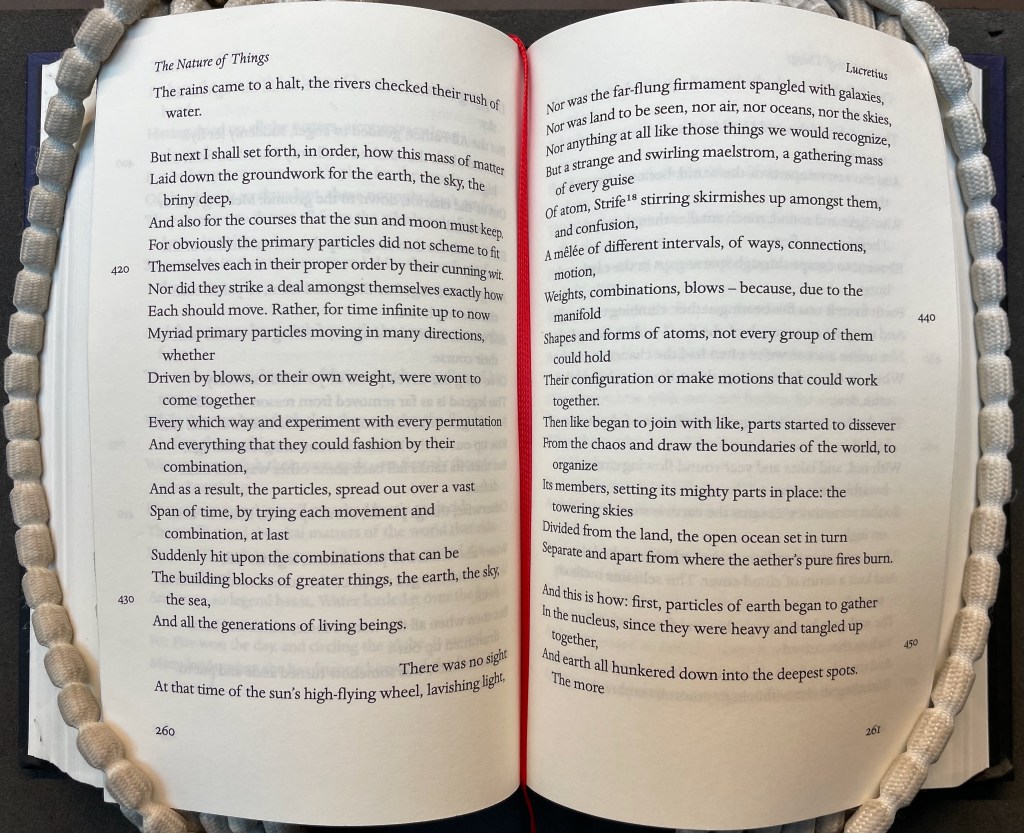

A.E. Stallings. The Nature of Things. London: Penguin, 2007.

Suzanne Moore’s Amorous Embrace (2023) aims for an altogether different kind of translation: to embody the essence of a handful of Lucretius’ lines in the materials, techniques and forms available to the calligrapher and book artist. In the passage Moore selects from Stallings’ translation, Lucretius begins to describe how the elements necessary for the formation of the cosmos and our world emerged. For convenience, here in bold are the lines:

But next I shall set forth, in order, how this mass of matter

Laid down the groundwork for the earth, the sky, the briny deep,

…

And this is how: first, particles of earth began to gather

In the nucleus, since they were heavy and tangled up together,

And earth all hunkered down into the deepest spots. The more

Tightly knit the earth, the more it squeezed out from the core

The bodies which would build the sun, the moon, the stars, the seas

And the vast ramparts of the world, because the seeds of these

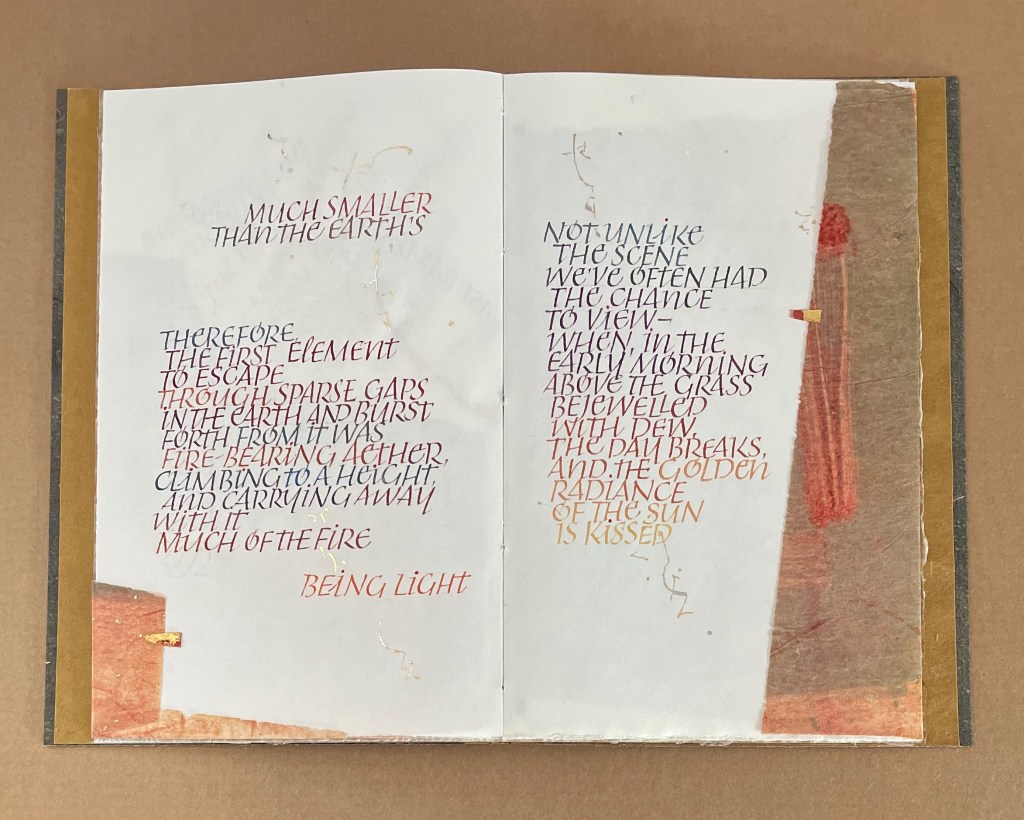

Were light and round, much smaller than the earth’s. Therefore, the first

Element to escape through sparse gaps in the earth and burst

Forth from it was fire-bearing aether, climbing to a height,

And carrying away much of the fire with it, being light.

Not unlike a scene we’ve often had the chance to view –

When, in the early morning, above the grass bejewelled with dew,

The day breaks, and the golden radiance of the sun is kissed

With red, and lakes and year-round-flowing streams breathe out a mist,

So that sometimes it seems the earth is steaming. Then on high,

The evaporations gather up beneath the vaulted sky

And knit a scrim of cloud-cover. This selfsame method served

The aether, which though thin and flimsy, wove one cloth that curved

And spread out far in all directions, blanketing every place,

Encircling all else within in its amorous embrace.

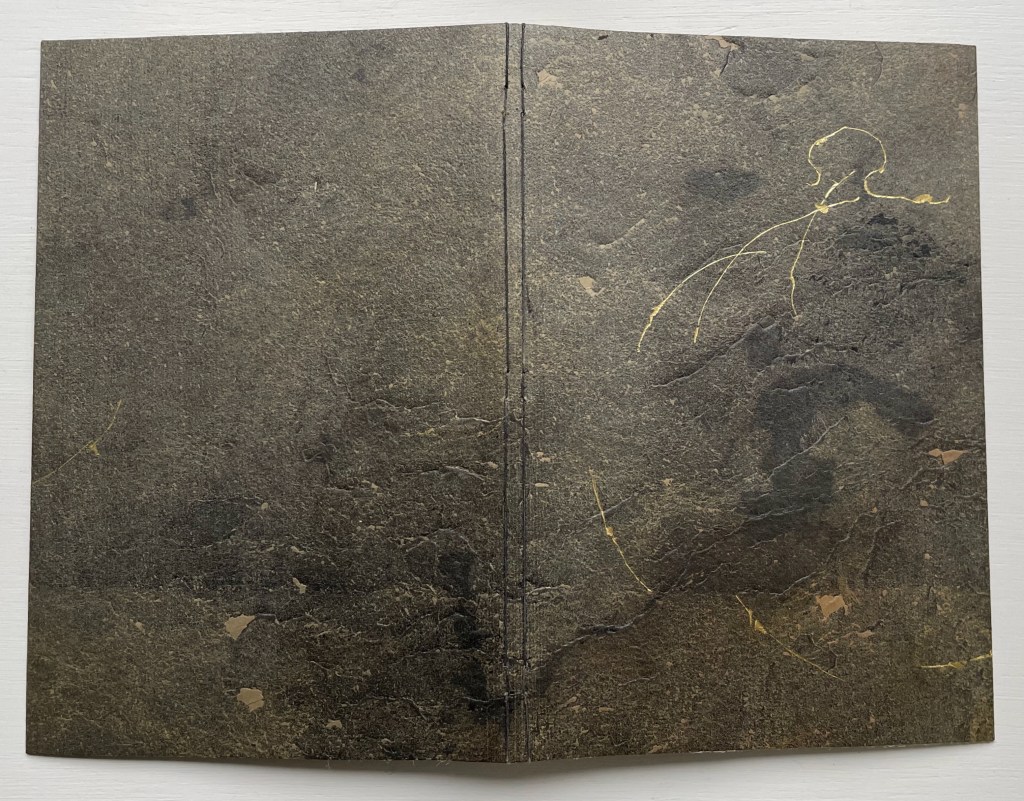

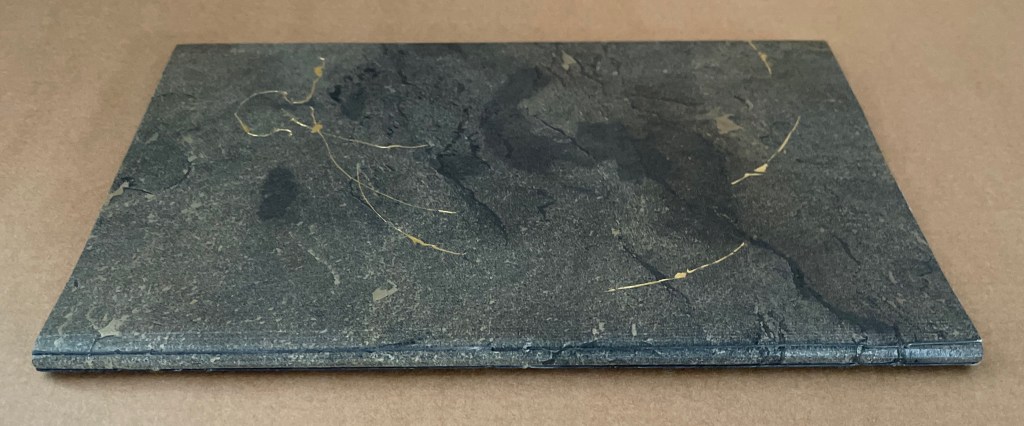

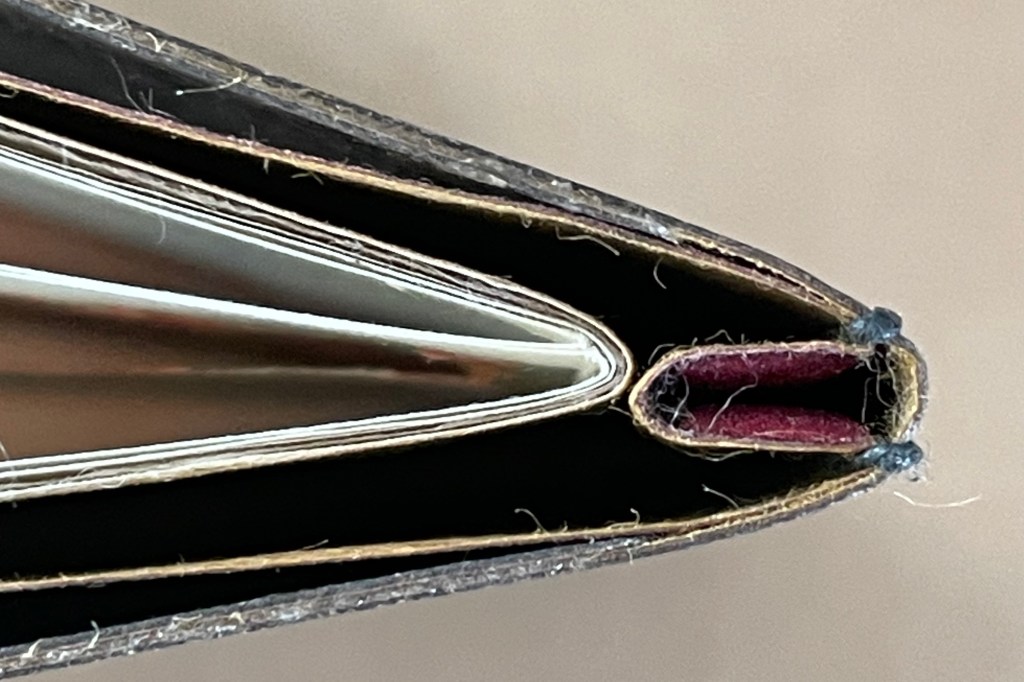

Taking the last two words above as her work’s title, Moore signals an intention to make her work a material metaphor for the whole passage. Even before the book is open, her transformation of text into material makes a stunning start. Its cover is made appropriately of the densest form of “earth all hunkered down into the deepest spots” — stone. This is “the core” from which the elements will emerge and eventually “build the sun, the moon, the stars, the seas/ And the vast ramparts of the world“. On, and in, the cover’s dark and real terrestrial matter, flecks of gold leaf suggest the stirring of the elements.

When the book opens, fiber-embedded endpapers echo the “thin and flimsy [woven] cloth that curved/And spread out far in all directions, blanketing every place, / Encircling all else within in its amorous embrace“.

Moore’s encompassing material metaphor even extends to the manuscript origin of De rerum natura. The multicolored Roman-based calligraphy on cream-colored vintage paper and the hand tooled gold leaf tabs evoke the 15th-century copied Latin manuscript and the decorative elements of the pre-incunabula period of books.

As mentioned above, the “first/Element“ to emerge is “fire-bearing aether“. In the spreads below, Moore uses thin, translucent painted paper, cut and torn in the shape of a plateau and slope, partially covering the lines of calligraphy and gold leaf that mimick that element’s bursting “Forth … climbing to a height,/And carrying away much of the fire with it, being light”.

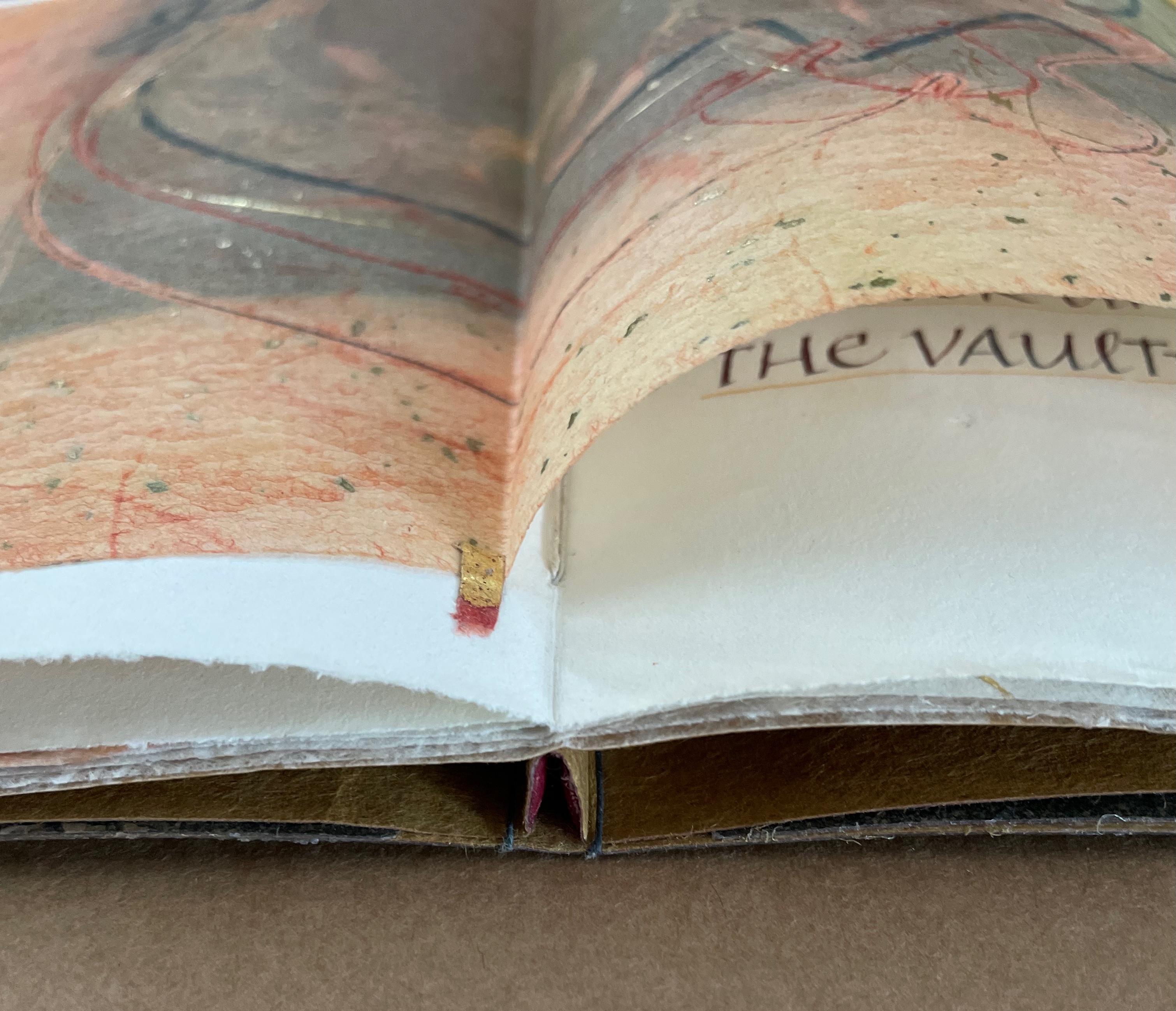

Moore works her material and techniques of collage and calligraphy together in paradoxical ways to express Lucretius’ content. The earth-suggesting paper is airy. In fact, it is lighter than the paper it partially covers: a heavy vintage paper bearing the lines of calligraphy and gold leaf that play out the fire-bearing aether’s escape. The loosely attached papers mimick the gaps through which the elements burst, and the hand tooled gold leaf tabs fixing the airy paper to the heavier paper and bejewelling the book’s leaves also echo the text — “the grass bejewelled with dew“.

When poets enjamb a poem’s lines, the syntax, rhythm and rhyme turn a line’s last word into the fulcrum of a seesaw. The sense of the sentence, the beat and rhyme make the reader balance on the last word, but also carry the reader forward to find completion of the sense, the next beat and the next rhyming word in the next line. Moore uses her materials and the physical turn of the page to embody the enjambment’s teetering on “kissed”. As soon discovered, the red-kissed gold leaf tab is pausing and anticipating the continuation of the last line.

In the spreads below, Moore prolongs that pause by fastening the kozo paper near the gutter with two more red-kissed gold leaf tabs and requiring a turn of its loose flap to find the poem’s next words, which so happen to be “with red”. That completes the anticipation created by the red ink highlighting the gold tab and by our wanting to know how the previous line of the poem will continue.

So why the prolonged pause? Moore’s monoprint image on the Japanese paper suggests the vibration and motion of atomic particles or molecules, which is perhaps a little unfair since the reader would have to know that Lucretius deals with that principle in the poem’s earlier books. Nevertheless, the principle causes the coalescence and transformation of the elements. When the leaf of kozo turns, the reader finds that, while finishing their enjambment, Lucretius/Stallings, too, are extending the pause with an added description of an early morning scene: the morning mists rising from lakes and streams, evaporating and gathering in the sky.

And again there is an enjambed line and a page turn before the added description is completed with those rising evaporations knitting “a scrim of cloud-cover“. All this — the building description and the pauses — turns out to be a metaphor for the transforming aether’s weaving, spreading and embracing the world.

As noted above, Moore’s encompassing material metaphor also draws in De rerum natura‘s manuscript origins, but it equally links the past of the book with the present. The use of collage and assemblage, the abstract monoprints on Japanese paper, the abstractness of strips of gold leaf applied in curves, straight lines and angles — all are practices of artists’ books and contemporary art. Like Stallings, Moore has set out to translate a work of art from the past into one on her own terms and the tradition of artists’ books.

Stub binding

Inside of front and back stone covers

Further Reading and Viewing

Here (at 52’50”) is Moore speaking at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art in 2017 about Chains of Love, an earlier foray into Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things.

“Suzanne Moore (I)”. 6 June 2023. Books On Books Collection

“Rutherford Witthus“. 28 October 2021. Books On Books Collection. See TRAIANUS for the only other work in the collection to use stone for a cover.

Barbour, Reid. 2010. “Anonymous Lucretius“. The Bodleian Library Record, 23:1. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Lucretius Carus, Titus, and William Ellery Leonard, ed. 1916. De Rerum Natura. In the Perseus Digital Library, edited by Gregory R. Crane, Tufts University.

Lucretius Carus, Titus, A. E. Stallings, and Richard Jenkyns. 2007. The Nature of Things. London: Penguin.

Marchant, Jo. July 2018. “Buried by the Ash of Vesuvius, These Scrolls Are Being Read for the First Time in Millennia“. Smithsonian Magazine.

Slattery, Luke. May 2023. “The Italian Job: Lucretius in the Renaissance“. Antigone: An Open Forum for Classics. [“The most likely source of Poggio’s manuscript, known as Codex Oblongus (O) on account of its shape, is held today in the Library of the University of Leiden in Holland. So, too, is Codex Quadratus (Q). These two Lucretian manuscripts, dating from the early-mid 9th century, were in separate monastic libraries several hundred miles apart in the 15th century. (A third, incomplete manuscript also survives from the 9th century, partly in the Royal Library of Copenhagen, Denmark, and partly in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. It is a sibling of Q, but only preserves 45 per cent of the poem.) Poggio doesn’t divulge the hiding place of his Lucretius, although Fulda in central Germany and Murbach in Eastern France are possibilities. So let’s imagine that monastic fires, or simultaneous acts of sacerdotal vandalism, managed to destroy all three complete manuscripts: O, Q, and the manuscript unearthed by Poggio that would in time be copied as L (Codex Laurentianus, written in the 1430s and now in the Laurentian Library of Florence). “]

Trépanier, Simon. Winter 2023. “Lucretius“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.).