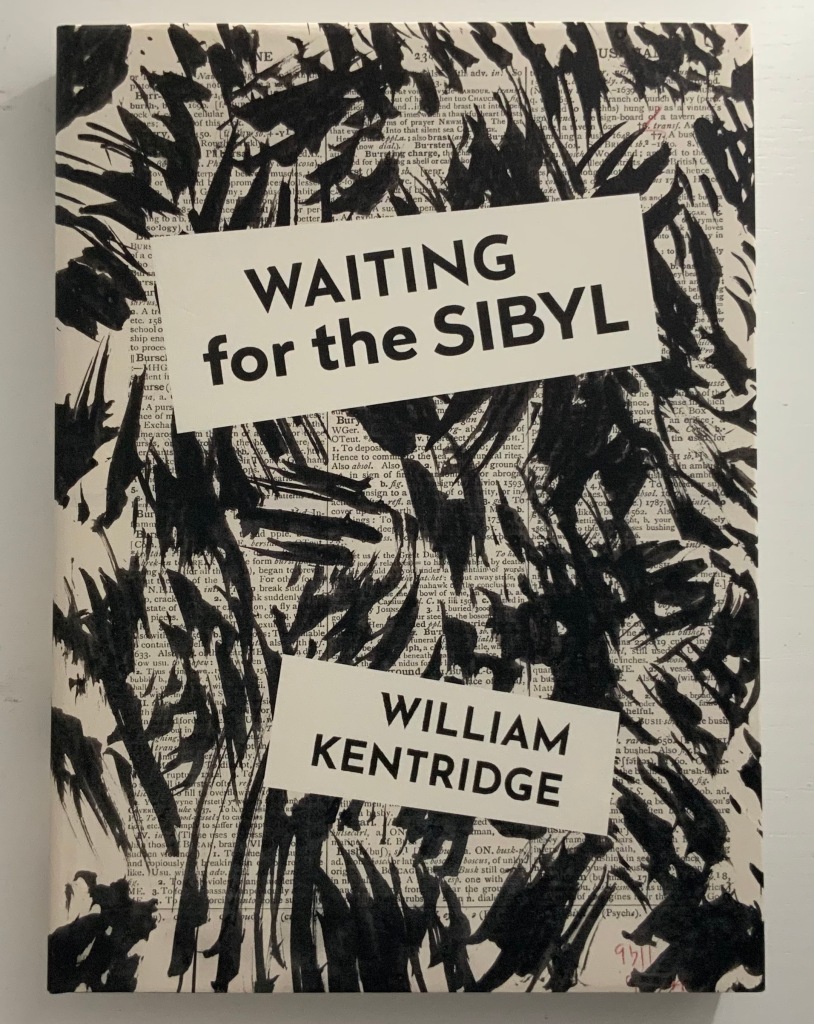

Waiting for the Sibyl (2020)

William Kentridge

Casebound and dustjacketed. H275 x W200 mm, 360 unnumbered pages. Acquired from Blackwells, 1 July 2021.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of the artist and the Marian Goodman Gallery.

Like the ancient Greek playwrights, William Kentridge begins his chamber opera’s retelling of the Cumaean Sibyl’s myth in medias res — in this case, in the middle of the dictionary at the letter M. Redactions and marks build and build across the dictionary pages, a visual prelude like a musical one. Then they suddenly disappear, leaving the “stage” to unmarked pages from the letter A, a thunderclap announcement in all caps bold and then an explanatory statement slightly reduced in volume with a lighter type face and uppercase with lowercase letters. What is going on?

Because performance of the opera was curtailed by the pandemic beginning in 2019/2020, we have only a few short clips from a trailer and filmed rehearsals to guess at how a live performance might have unfolded: this short clip posted by Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, this one from Quaternaire, this one from The Red Bridge Project and this version posted by the Centre for the Less Good Idea. A description from the Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg tells us that the performance consists of a series of six short scenes. From the Red Bridge Project, coordinating the commission, we have Kentridge’s description of four of them:

A scene in the waiting room for the Sibyl. A scene about which is the right decision and which is the wrong one. How do you know which is the chair that will collapse when you sit on it and which is the chair that will support you? Is the plane that you’re rushing to catch the one that will crash or do you relax and not catch that plane and take the next one − and in fact that is the one that crashes?

Judging from the videos and description, it is presumptuous to declare that the book and opera begin in medias res. Almost anywhere in the out-of-order pages or chaotic rehearsal scenes of performers snatching at and reacting to the scattered leaves of books, typescript and so on is the middle. But if the left-to-right reading convention of the Western codex prevails, the text to be sung continues to rumble along in the codex after the thunderous proclamations. The chorus or speaker seems to falter, admitting to having forgotten the message and losing the moment of its delivery. All the while, the libretto is being joined on the left by gradually forming images of leaves (a maple and an oak), an allusion to the leaves on which the Cumaean Sibyl would write the predictions of fate she had sung but which would be scattered and whirled by the wind before the supplicant could claim his or her rightful leaf.

As occurs in Kentridge’s other bookworks, these gradual formations draw on the flip-book tradition, introducing that other recurrent media in his work — film — as well as performing an echo of the projections in the to-be performed opera. As the leaves assert themselves, the speaker’s confidence returns in all caps, a larger face and some bold. And while the speaker quickly recedes into lowercase and a lighter typeface, only able of being reminded “of something I can’t remember”, a leaf begins to metamorphose into a tree, an ampersand and then a dancer. Metamorphosis is that mythical translation of one being or object into another. Metaphor is that figure of speech that uses one object to remind us of another. “Etc., etc.” is what we say when we can’t remember or be bothered to complete a statement or series of examples. What Kentridge offers here is unquestionably not mixed metaphor but rather metaphor-mosis.

The metamorphosing ampersand recalls an illustrative example from another of Kentridge’s favored media — sculpture. As Kentridge puts it:

The turning sculptures I’ve made in the past have all been ones which have one moment of coherence, when the different components of the sculpture align. From one viewpoint they turn into a coffee pot, a tree, a typewriter, an opera singer. And then, as the sculpture turns, the elements fragment into chaos. — from The Red Bridge Project site, accessed 21 July 2021.

Ampersand (2017)

William Kentridge

Bronze, 85 x 82 x 54 cm, 87 kg

Courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery

Even though there is a speaker/singer for the libretto, the dancer has the central role in the opera. Performed by Teresa Phuti Mojela, the dancer casts her shadow over the projected pages and seems to “dance” the prophecies. Kentridge notes in the book’s afterword that he has added images of her to stand in for her projected shadows. As this sequence in the codex shows, the dancer/Teresa Phuti Mojela is the Sibyl.

In addition to containing the libretto, serving as part of the setting for the actual performance, presenting the central player and the Sibyl’s transformation into her, demonstrating the dancer’s performance (when flipped like a flip-book) and exemplifying the key props (prophecies on leaves), the codex also reflects the collaborative creative effort that Kentridge extols in describing the opera’s preparation:

… when we had our first workshop in Johannesburg, in which we brought together the singers, the pianist, a dancer to be the Sibyl, costume designer, set designer, videographer, the editor of the animations I’ve been drawing, we discovered very quickly that the magic of the piece was in the live performance of the music. At this point the project became possible to do only if we could have these singers on stage.

As the book’s last page notes, creative collaboration among Kentridge and Anne McIlleron (editors), Oliver Barstow (designer), Alex Feenstra (lithographer) and robstolk® (lithographer and printer) is what has made this work of art possible.

Tummelplatz (2016)

Tummelplatz (2016)

William Kentridge

Papercased sewn booklet. H214 x W152 mm, 16 pages. Acquired from Lady Elena Ochoa Foster, 28 June 2022, “Sensational Books” exhibition at the Bodleian Libraries.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

In Tummelplatz the booklet created for the Ivorypress exhibition of the larger eponymous work, William Kentridge explains that tummelplatz is Freud’s term for the space between analysts and their patients. But its literal translation is “playground”, which might be the perfect word for William Kentridge’s studio. The studio is the actual setting for the series stereoscopic photographs reproduced as photogravure images in the double volume of Tummelplatz. With the artist’s charcoal drawings of a landscape background pinned to the walls and others cut out as foreground figures and fixed into position, the studio was transformed into a sort of diorama in which the artist himself posed. A stereoscopic viewing device in fixed position over the volume invites the reader/viewer to join Kentridge in his playground.

These are images that have to be read, not scanned like flat photos. The eyes’ focus has to jump from layer to layer, element to element. In the exhibition “Sensational Books”, Tummelplatz is set up within a glass case, so only one scene is available for viewing and reading, and the distance imposed by the extra layer of glass makes the sensation hard to appreciate. Nevertheless, there is enough of it to set the reader/viewer to wondering whether the technique, the effect of the photogravure and this three-dimensional precursor to virtual reality have transformed him or her into the patient and the work of art itself into the analyst. Or whether it’s just a playdate with William Kentridge in his playground.

Showcased at “Sensational Books” exhibition, Weston Library, Oxford University. Photo: Books On Books, 8 July 2022.

Showcased at “Sensational Books” exhibition, Weston Library, Oxford University. Photo: Books On Books, 8 July 2022.

William Kentridge : Lexicon (2011)

William Kentridge : Lexicon (2011)

William Kentridge

Cloth boards, sewn bound. H234 x W177 mm, 160 pages. Acquired from Specific Object, 2 May 2021.

Photos of the book: Books On Books Collection. Permission courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery.

The first work by Kentridge I ever saw displayed was 2nd Hand Reading (2014) at the Museum Meermanno (The House of the Book) in The Hague. The exhibition was called The Art of Reading and had been curated by Paul van Capelleveen. Curator at the Dutch national library and advisor to the Meermanno, he felt strongly that the challenges of artist books cannot be understood “under glass” and insisted that each work be touchable. So under his supervision, I was able to flip through 2nd Hand Reading and also watch the projected animation of stop-motion images across the pages being flipped. While the forward motion of the animation offers a narrative, its substrate — pages of the Shorter Oxford English dictionary on historical principles — contradicts any notion of logical beginning, middle and end: the drawn-upon pages are not in the original’s paginated or alphabetical order.

Compared to 2nd Hand Reading‘s 800 pages, Lexicon at 160 pages provides a small reminder of the experience. Bound in a green satin-sheen cloth, Lexicon begins as a facsimile edition of an antiquarian Latin-Greek dictionary. The dictionary’s browned pages and antique languages perform the role of drawing surface or projection screen for a flip-book metamorphosis. In scrawly black ink drawings, an Italian coffee pot emerges from the gutter and starts to tilt and turn.

Gradually the pot changes into a black cat, striding from right to left. Not the direction in which Western reading and narratives usually proceed. In its transformation and movements, the cat seems to pivot on itself as it turns and strides across the Latin and Greek like Rilke’s panther behind its bars until it turns back into a coffee pot. Or does it?

That drawing in the center certainly looks like the coffee pot, but as the pages turn, the cat returns to stride from left to right, expanding then shrinking until it is swallowed by the gutter.

The reference to Rilke’s panther is actually Kentridge’s, made ex post facto in the next book in the Collection.

Six Drawing Lessons (2014)

Six Drawing Lessons (2014)

William Kentridge

Cloth boards, sewn bound. H x W mm, 208 pages. Acquired from Amazon, 23 March 2019.

Photos of the book: Books On Books Collection. Permission courtesy of the artist and Goodman Gallery.

You rarely see a clear dustjacket. Of course, if it has type printed on it, you can see it. Still, it is rare, and in this case — in light of Kentridge’s film artistry — transparently ingenious.

The six lessons — Kentridge’s Charles Eliot Norton Lectures delivered at Harvard — begin with an extended riff on Plato’s allegory of the cave. Variations on the riff recur throughout — applied to film projected from behind the audience, to a stage design of The Magic Flute as the bellows of a tripod camera, to transformations and metamorphoses and to the mining caves under Johannesburg. Kentridge’s interpretation of Plato’s cave reminds me of José Saramago’s interpretation in A Caverna (2014) and Guy Laramée’s homage to A Caverna. All three address “the great cloud of unknowing“, a kind of knowing by not knowing — but without God.

A Caverna (2012)

Guy Laramée

Portuguese-Spanish dictionary carved. Wood and velvet plinth, wood-framed glass cover. H260 x W276 x D226 mm

Acquired from William Baczek Fine Arts, 12 September 2017.

What’s remarkable is how Kentridge brings so many variations, seeming tangents and media in the lectures into coherence. Or perhaps not so remarkable given that he manages it across his body of work and the multiple media in which he works. In breadth of stuff and raw material to hand and in his head, Kentridge himself identifies Picasso’s studio practices and work as an influence. Although not mentioned, Anselm Kiefer’s works such as Das Lied von der Zeder – Für Paul Célan (“The song of the cedar – for Paul Célan”, 2005) and his studio at La Ribaute, near Barjac in France, come to mind in these lectures. Likewise another artist called to mind is Xu Bing, especially his Landscape/Landscript (2013) and massive junk assemblage Phoenix (2008-15) among other works. Both Kiefer and Xu use the book as a medium with which to fuse language or text with the visual. All three artists confront similarly dark, raw cultural inheritances. Kentridge’s lectures, especially Lessons Two and Three, make plain his apartheid inheritance and its presence in his art.

Circling back to the book as artistic medium, the fifth and sixth lessons provide an important insight that underscores Kentridge’s artistry there. “Lesson Five: In Praise of Mistranslation” reproduces Rilke’s “Der Panther” and Richard Exner’s translation of it in full. In that same lesson, Kentridge presents us with a montage of the feline transformations and names the works from which they come, one of them of course being Lexicon.

Before going back to Lexicon for the cat, the reader/viewer would do well to wait for Kentridge to expand in the sixth lesson on the lines describing the panther’s walk around his cage as “a dance of strength round a centre where a mighty will was put to sleep”. He writes:

There is no avoiding it. …it is the circle in the studio, the endless walking around the studio, … Again here we go back to Rilke’s panther, and the radical insufficiency, the radical gap in the center. There has to be some gap, some lack, which provokes people to spend 20 years, 30 years, making drawings, leaving traces of themselves. It has to do with the need to see oneself in other people’s looking at what you have made.

With that, remember the cat — metamorphosing from the Italian coffee pot that slips from Lexicon‘s gutter, prowling from right to left, turning back into the coffee pot, striding from left to right and then being sucked into the center. Can you ever look the same way at the gutter of a book?

Further Reading & Viewing

“The Art of Reading in a ‘Post-Text Future’“. 21 February 2018. Bookmarking Book Art.

“Werner Pfeiffer and Anselm Kiefer“. 16 January 2015. Bookmarking Book Art.

“William Kentridge standing in front of ‘Action’, 2019, in his new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 24 September – 11 December 2022.

Kentridge, William. 2012. Six Drawing Lessons, Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Harvard University. Six videos from the Mahindra Humanities Center, posted 14-15 January 2020. Lesson 1, Lesson 2, Lesson 3, Lesson 4, Lesson 5, Lesson 6. Accessed between 1 April 2019 and 21 July 2021.

Kiefer, Anselm, and Marie Minssieux-Chamonard. 2015. Anselm Kiefer: l’alchimie du livre.

Krauss, Rosalind E. 2017. William Kentridge. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Mudam Luxembourg. 11 – 12 Jun 2021. “Sibyl“. Announcement. Accessed 22 July 2021. “Waiting for the Sibyl, co-commissioned by the Théâtres de la Ville de Luxembourg, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and Dramaten – Stockholm and created in collaboration with choral director and dancer Nhlanhla Mahlangu and composer Kyle Shepherd, unfolds in a series of six short scenes, …”