The entry on Transforming Hate by Clarissa Sligh, her first work acquired for the Books On Books Collection, was posted in September 2020, just over a month from an election that offered a step away from hate, prejudice, and bigotry. Unfortunately insurrection brushed the offer aside. Four years later, another election, and reactionism and revanchism seem to have the upper hand. In such times, Clarissa Sligh’s book art, photographs, and recorded lectures provide a tonic of bittersweet hope. You cannot help but be struck by the persistent but wary humanity of the art and the artist.

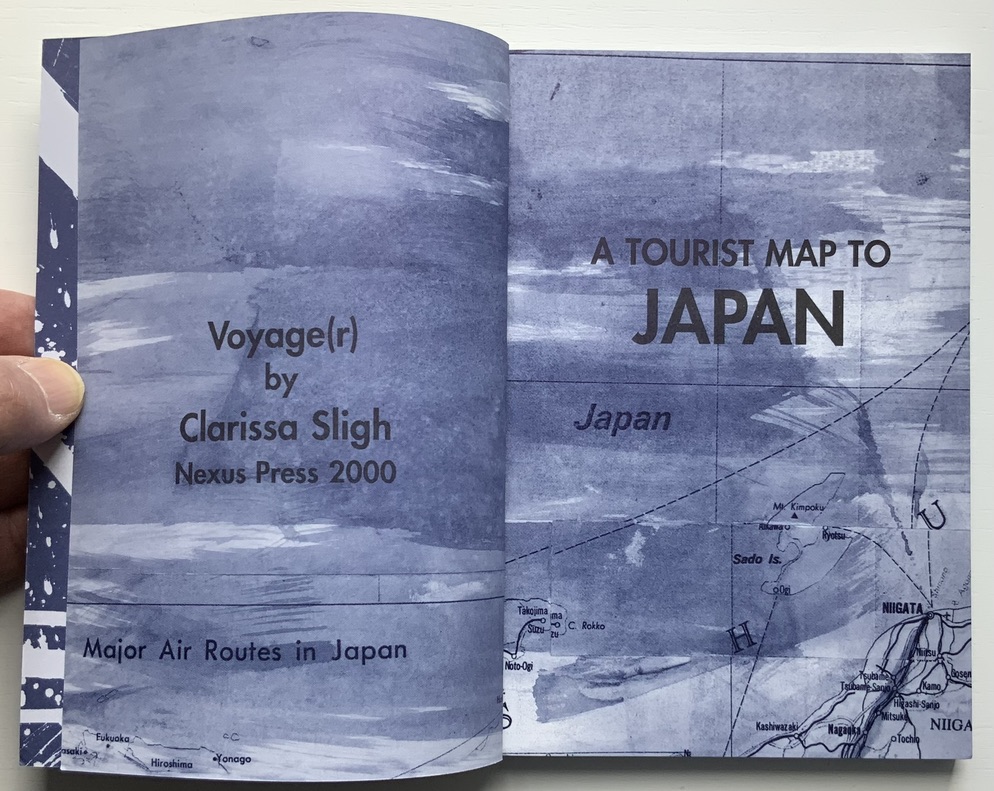

Voyage(r) (2000)

Voyage(r): A Tourist Map to Japan (2000)

Clarissa Sligh

Perfectbound paperback. H184 x W127 mm. [144] pages. Edition of 1000. Acquired from Hudson River Books, 11 February 2021.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Artist’s description: “In this diary-like artist’s book, Sligh recounts a trip to Japan through a thoughtfully constructed montage of photography, texts, and abstract gestural paintings. In personal and poetic musings, the author ponders her relationship to Japanese culture, both as a first time visitor and as an African American woman. Beautifully printed in blue and black duotones, the book comes in a cloth bag.”

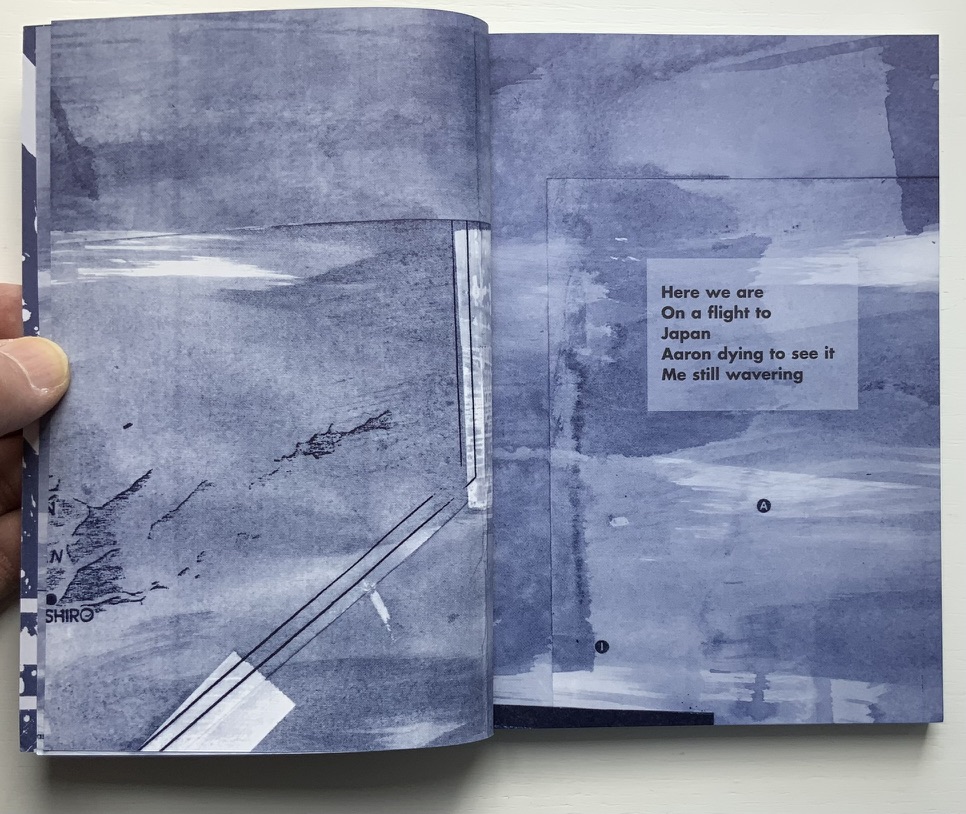

The trip begins with reluctance and trepidation.

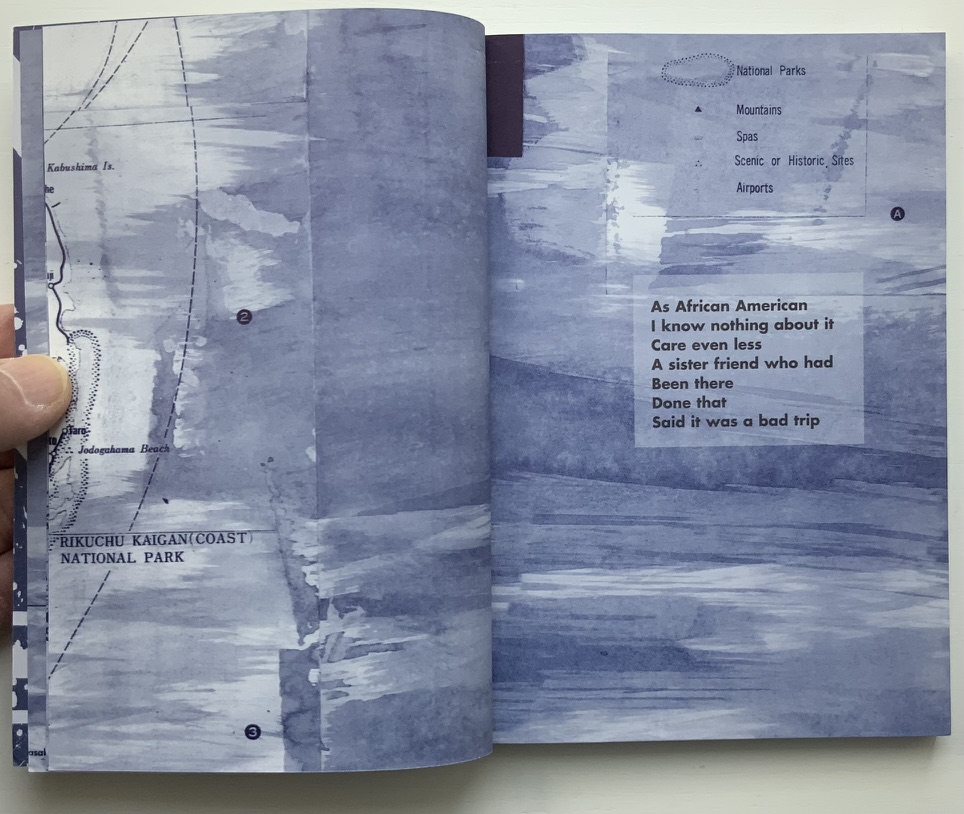

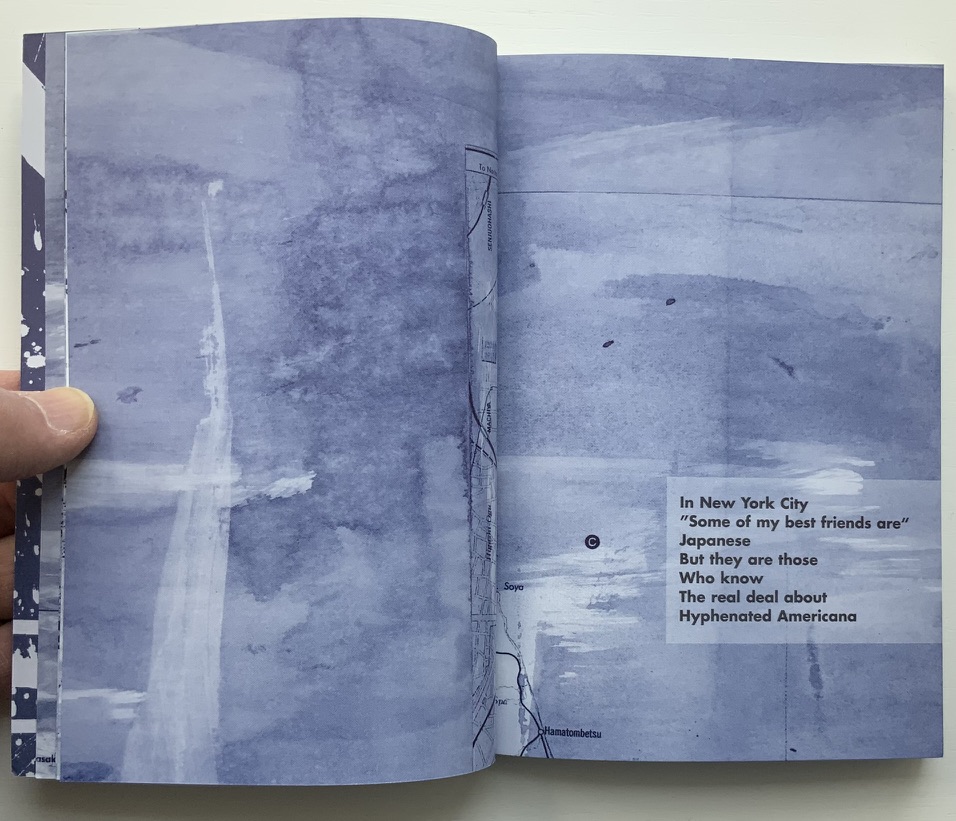

Sligh’s travel jitters are not the only source of wariness. They also stem from an ironic self-awareness of her own prejudice (‘”Some of my best friends are” Japanese’) and distance from knowing the “real deal” of this other branch of “Hyphenated Americana”.

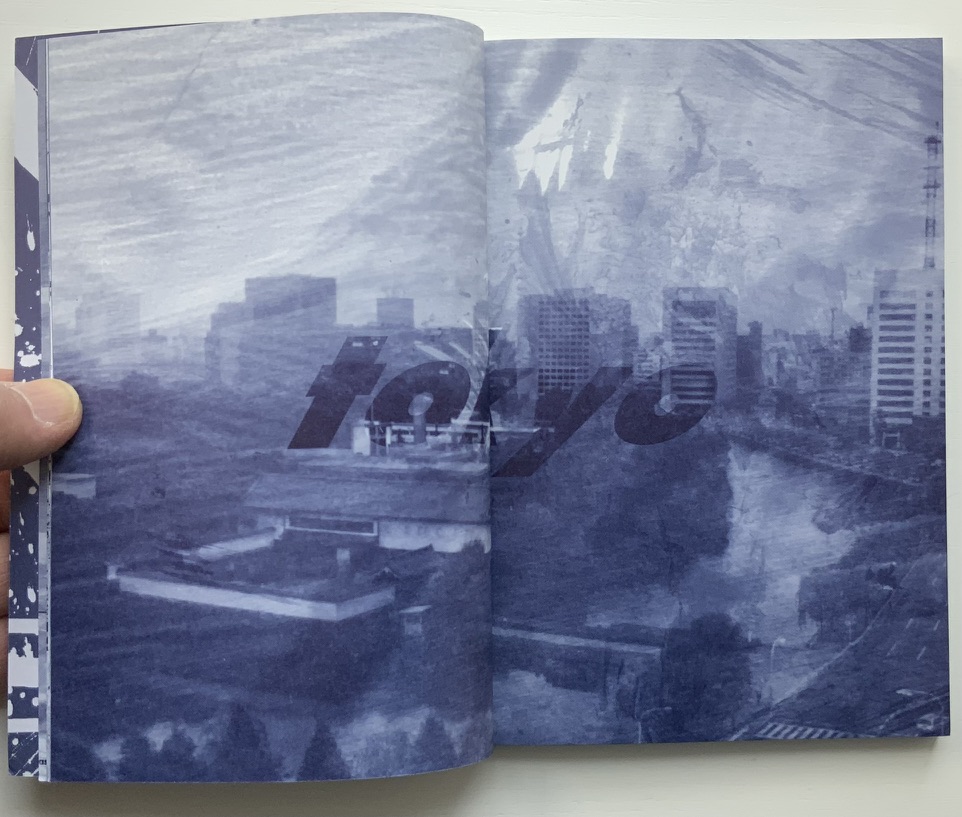

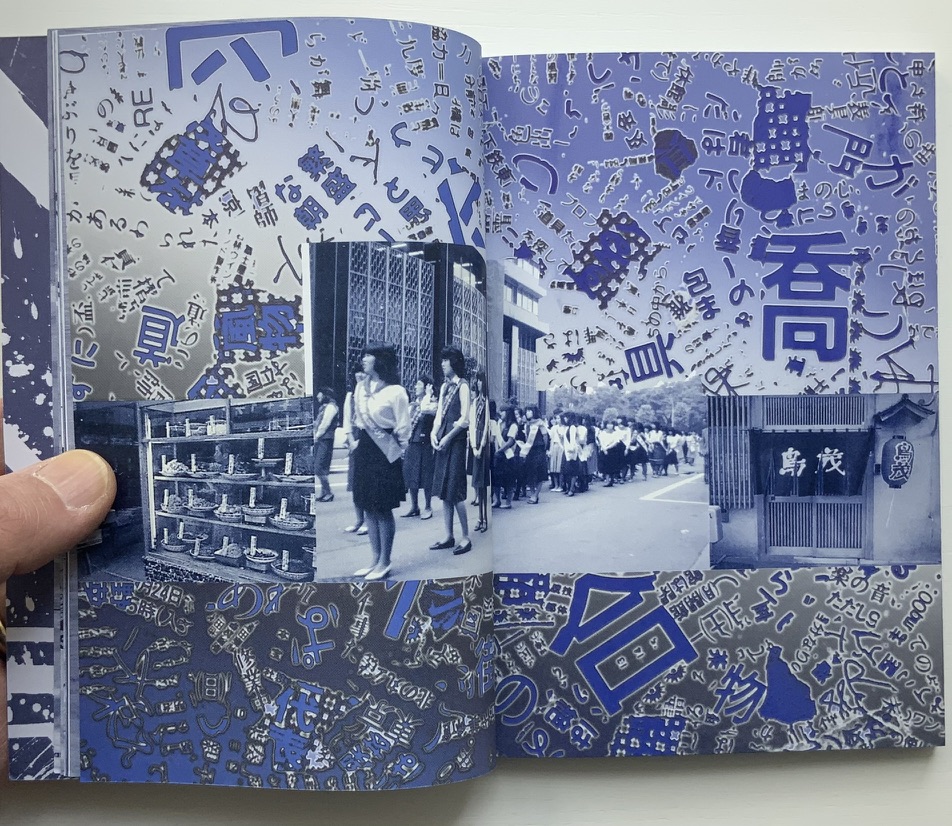

The descent from a hazy airplane window view to a montage of linguistic confetti and street-level views delivers the diary-like narrative while sharing Sligh’s perception of her filtered view.

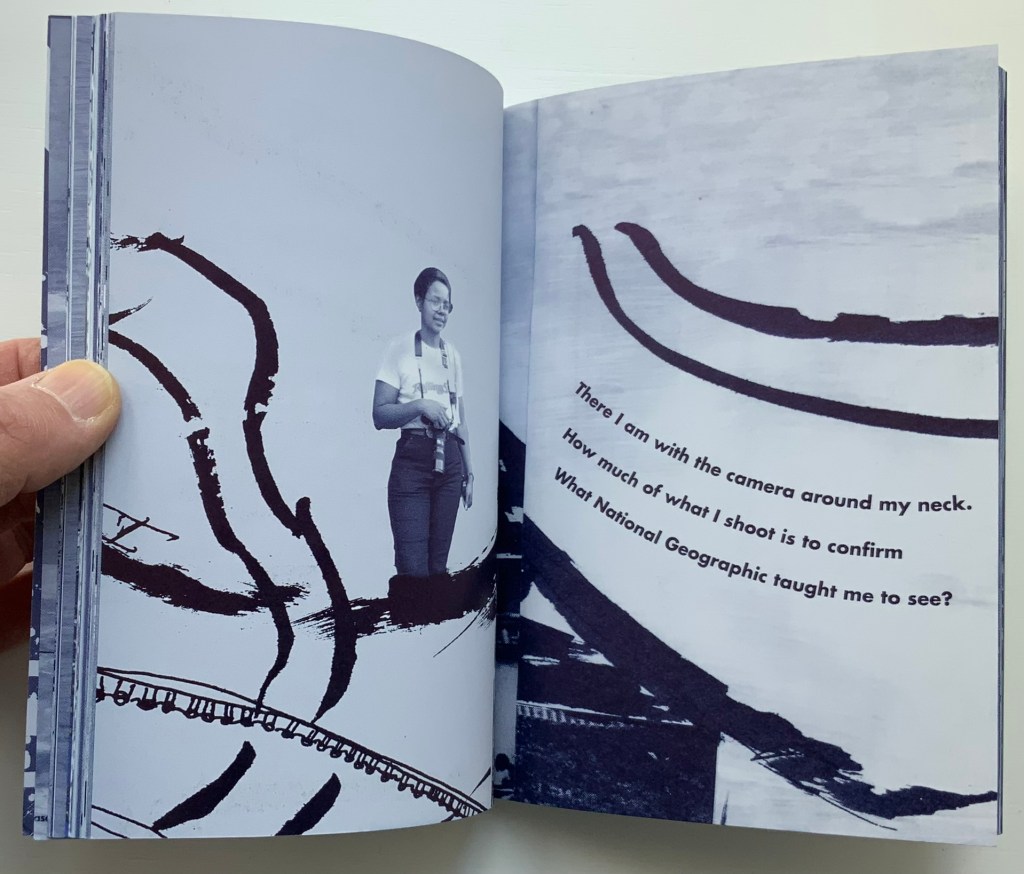

The spread in which she seems to float among brushtrokes that give a stereotypical roof profile to a fragmented photo bears text that emphasizes Sligh’s awareness of her perspective’s artifice and cultural filters.

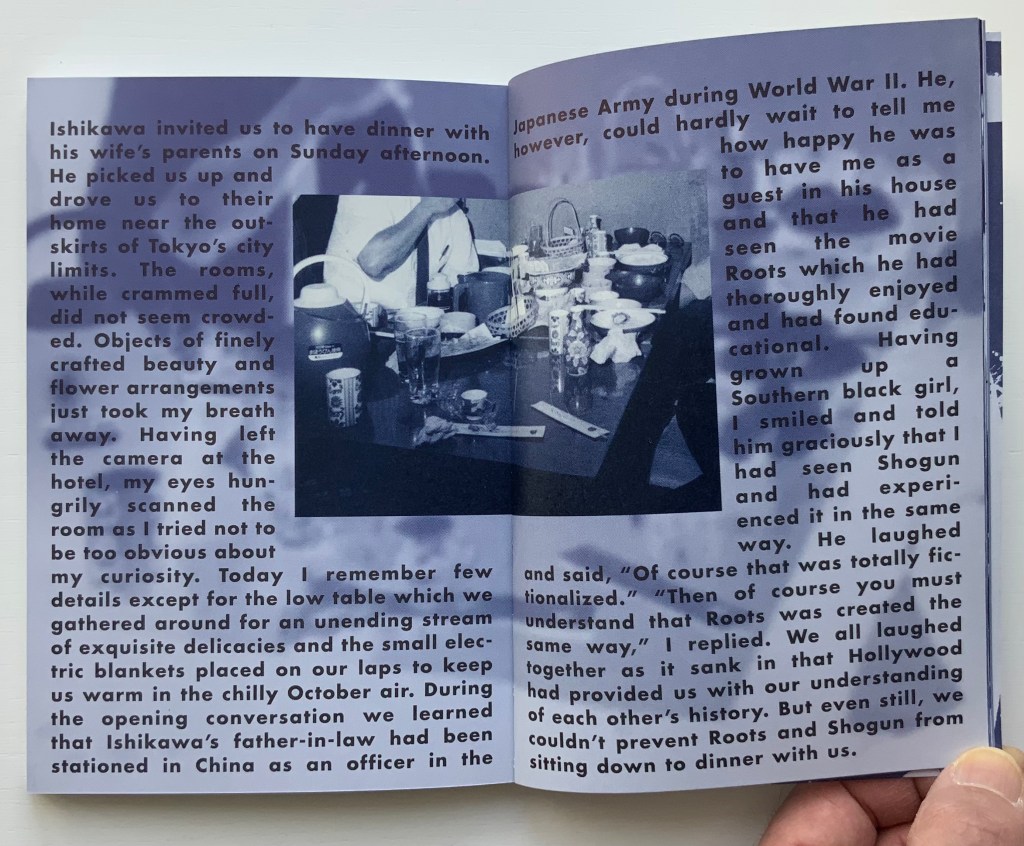

Sligh’s self-awareness does not hold back a naturally human self-defensiveness during a meal when her host happily asserts his awareness of her background because he has seen the television show Roots. Even when countering Roots with Shogun and everyone laughing about it, Sligh steps back into her self-awareness.

In the current moment, can the other-fearing and other-hating conceive of asking, “What epic television drama depicting your ancestors could possibly serve as the analogously awkward guest to sit down with Roots and Shogun at this dinner table?”

Sligh’s ability in her artist’s books to stand outside herself while being herself is preternatural. It is also astonishingly foresightful in the next work.

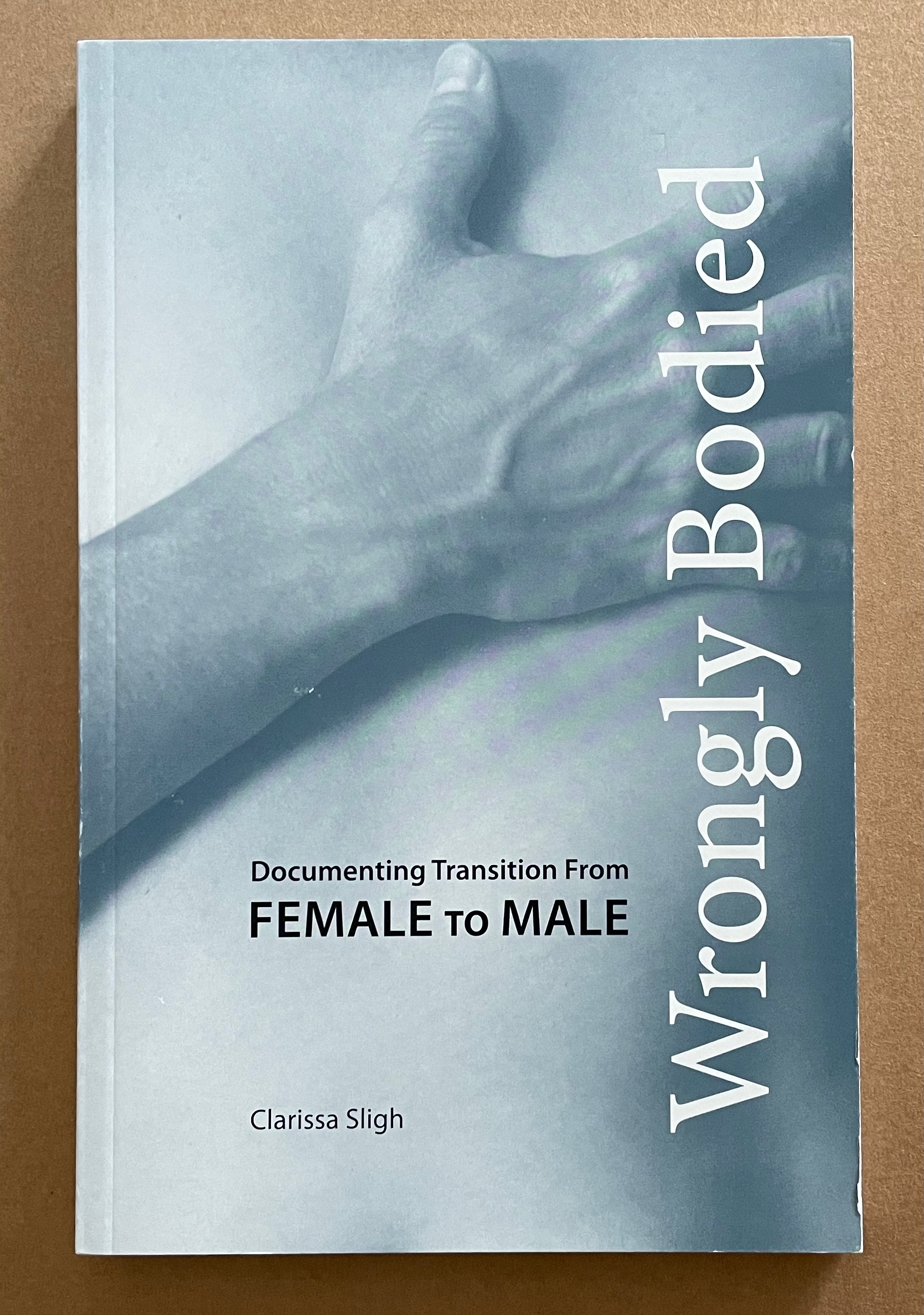

Wrongly Bodied (2009)

Wrongly Bodied: Documenting Transition from Female to Male (2009)

Clarissa Sligh

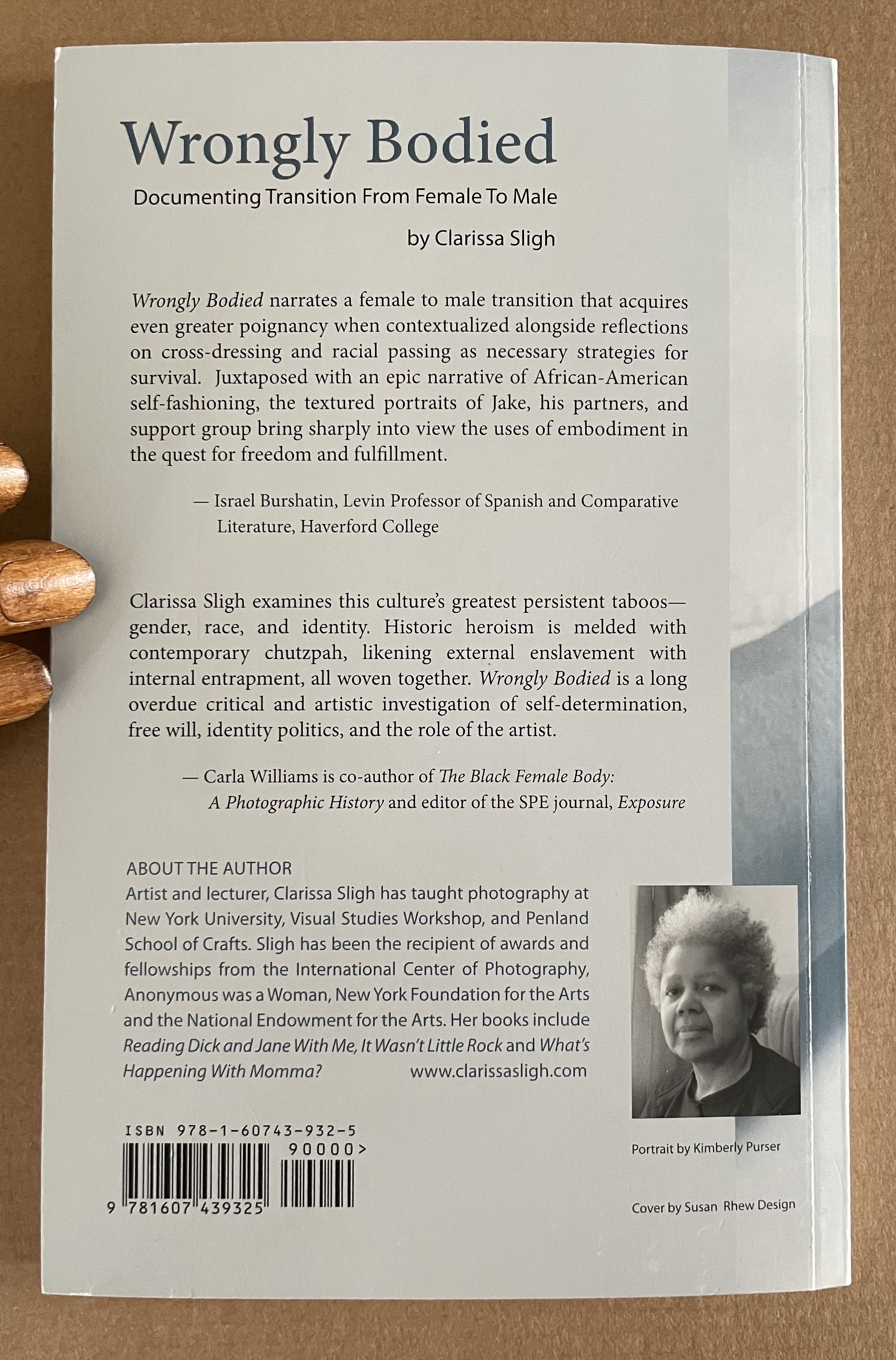

Perfect bound paperback. H197 x W127 mm. 160 pages. Acquired from Vamp & Tramp, 15 Sep 2023.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

An earlier casebound limited edition in digital and screen print of Wrongly Bodied was created in 2004 at the Women’s Studies Workshop. Twenty-0ne years later, it remains as topical, if not more so.

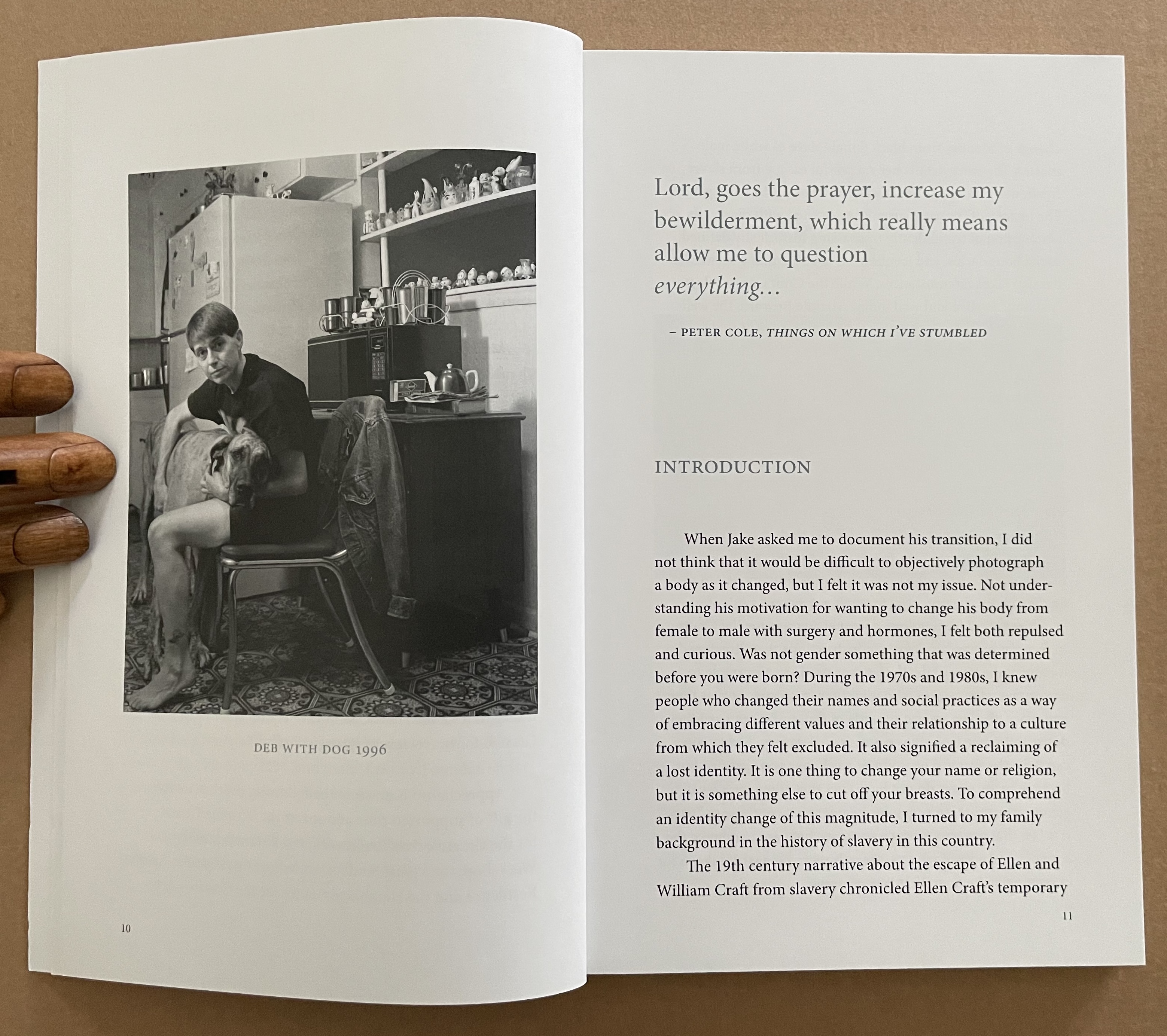

Just as Voyage(r) begins warily, so too does Wrongly Bodied. As Sligh explains in her 2020 Mills College lecture, Wrongly Bodied emerged from another project — “The Masculinity Project, 1994-1999”, which explored African-American men’s perception of manhood. With a desire to understand her father, Sligh could see “The Masculinity Project” as personal, but with Deb and her gender dysphoria that led to Jake, Sligh felt initially “this is not my issue”, as she puts it.

When Jake asked me to document his transition, I did not think that it would be difficult to objectively photograph a body as it changed, but I felt it was not my issue. Not understanding his motivation for wanting to change his body from female to male with surgery and hormones, I felt both repulsed and curious. Was not gender something that was determined before you were born? …

My looking for masculine women to photograph, in a small North Texas town, was how we met. Having come from New York City to attend a small women’s college, I was astonished that such a tiny woman could puff up her chest and say, “I am really a man who happens to be in a woman’s body.”

Trying to avert my eyes so as not to stare, I thought, “If this chick is a man, then what in the hell am I?”

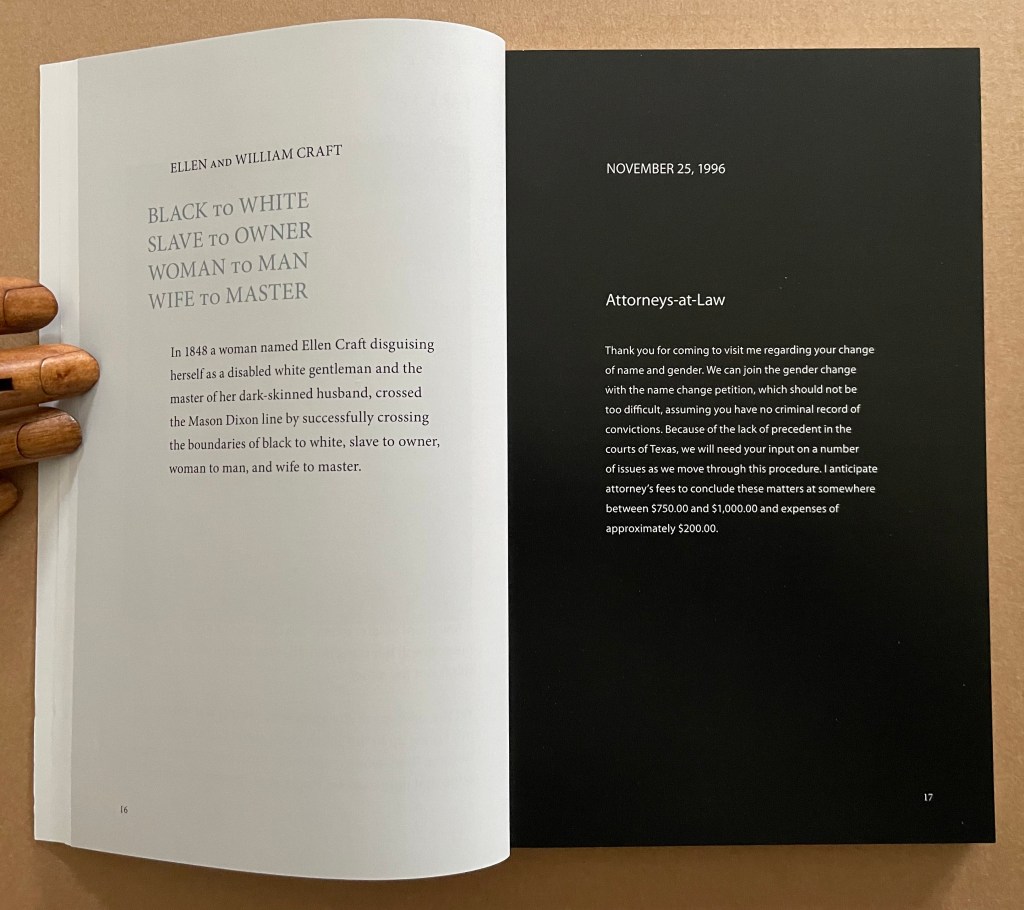

To frame the “issue” as one she could understand, Sligh turned to the nineteenth-century escape story of Ellen and William Craft, in which Ellen whose skin would let her “pass” for white changed her identity as a black female slave to that of white male master.

At that time and place, the law was on the side of those who opposed their desire to be free from the oppression of slavery. Today, you can have the surgical procedures to change your gender, but because many states do not have laws that allow for a legal gender transition, transgender people must continue to “pass.” It is law that governs western societies, but can it embrace the complex nuances of who we are as human beings? It takes a lot of courage to be oneself; this is my issue.

After those preliminaries, Sligh starts the artist’s book in earnest with the Crafts’ story in black ink on white paper juxtaposed with a reversed-out white on black excerpt from a letter from Deb’s lawyers who handled the legalities of the change of name and gender. The white page then the black page underline Sligh’s primary technique of juxtaposing Deb/Jake’s story with the Crafts’, but before hitting her stride with it, Sligh pauses.

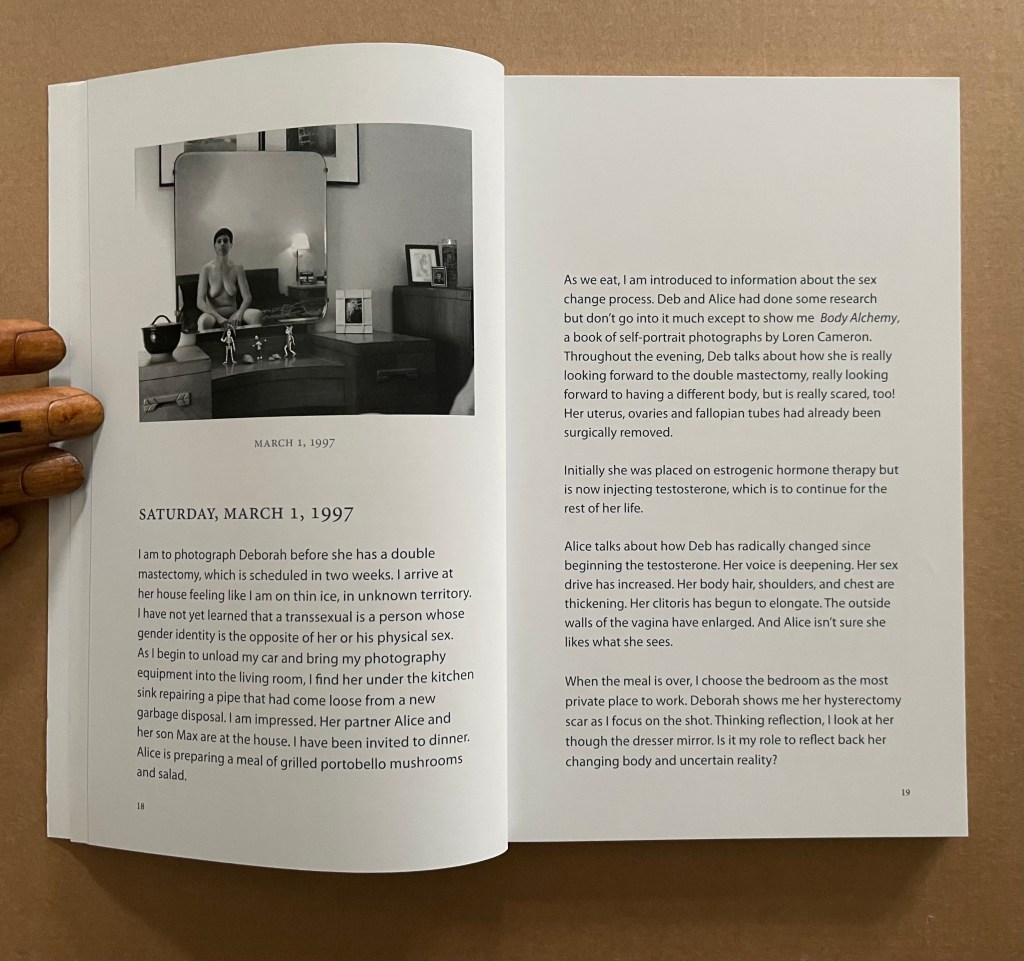

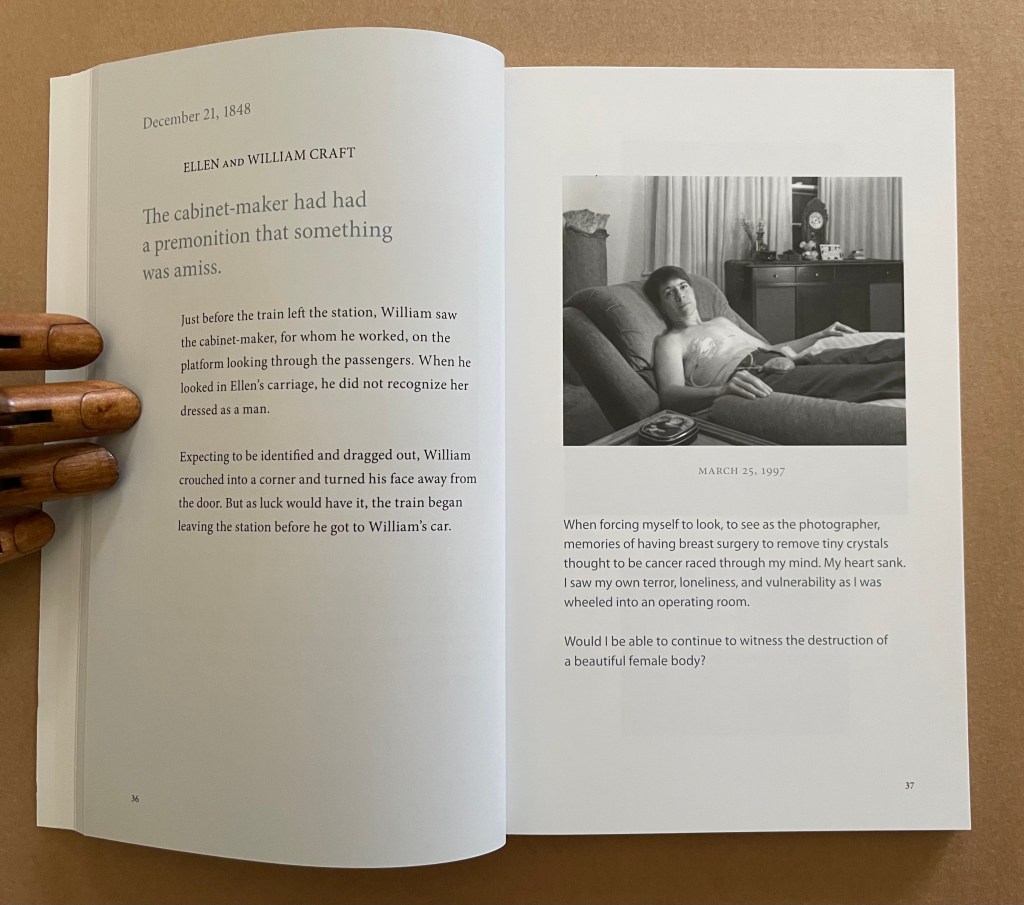

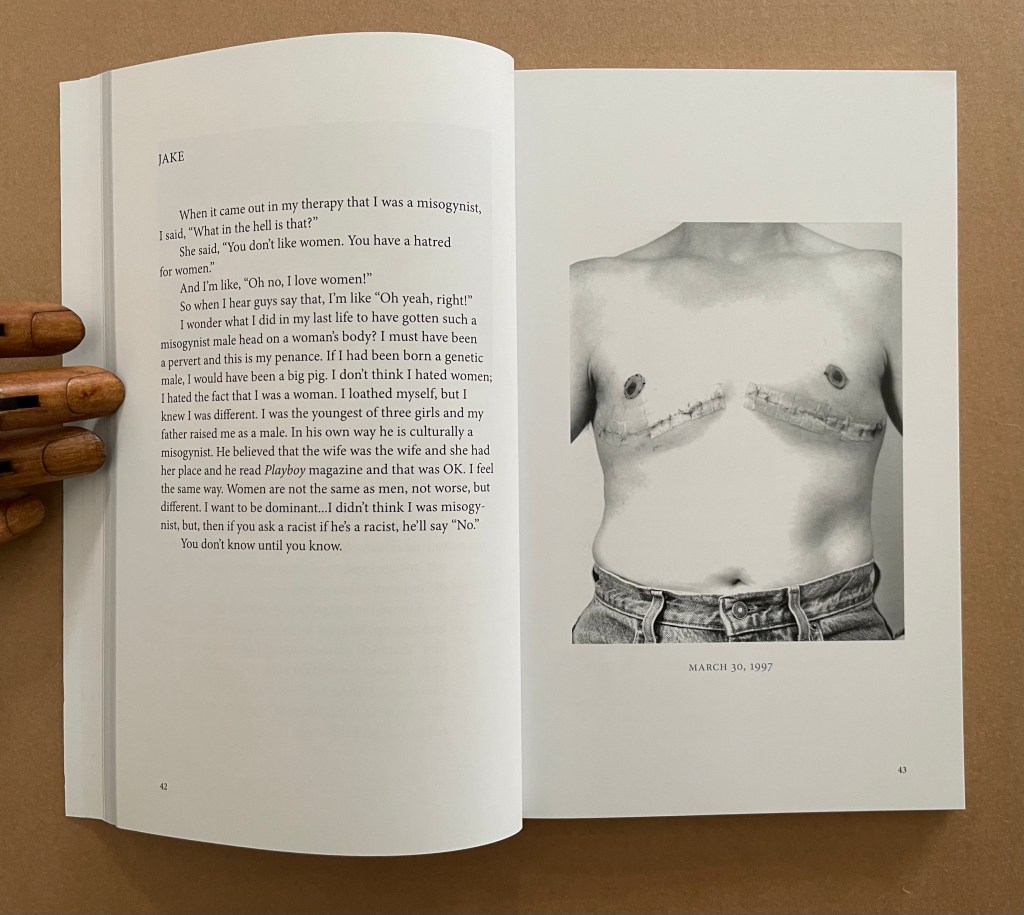

The next double-page spread presents a stark black-and-white nude, a photographed reflection of Deb/Jake well after the removal of the female sexual organs but prior to the mastectomy. As Sligh explains in her journal entry, this photo was taken after a dinner meeting with Deb/Jake and partner Alice. The description of the meeting serves several important purposes. One is to reassert Sligh’s self-aware artistic presence: “Thinking reflection, I look at her through the dresser mirror”. Another purpose is to restate Sligh’s professional and personal unease: “Is it my role to reflect back her changing body and uncertain reality?” Another purpose lies in the sentence “Alice talks about how Deb has radically changed since beginning the testosterone”, which lays the groundwork for one of the most tellingly self-aware remarks that Jake will make later in the book.

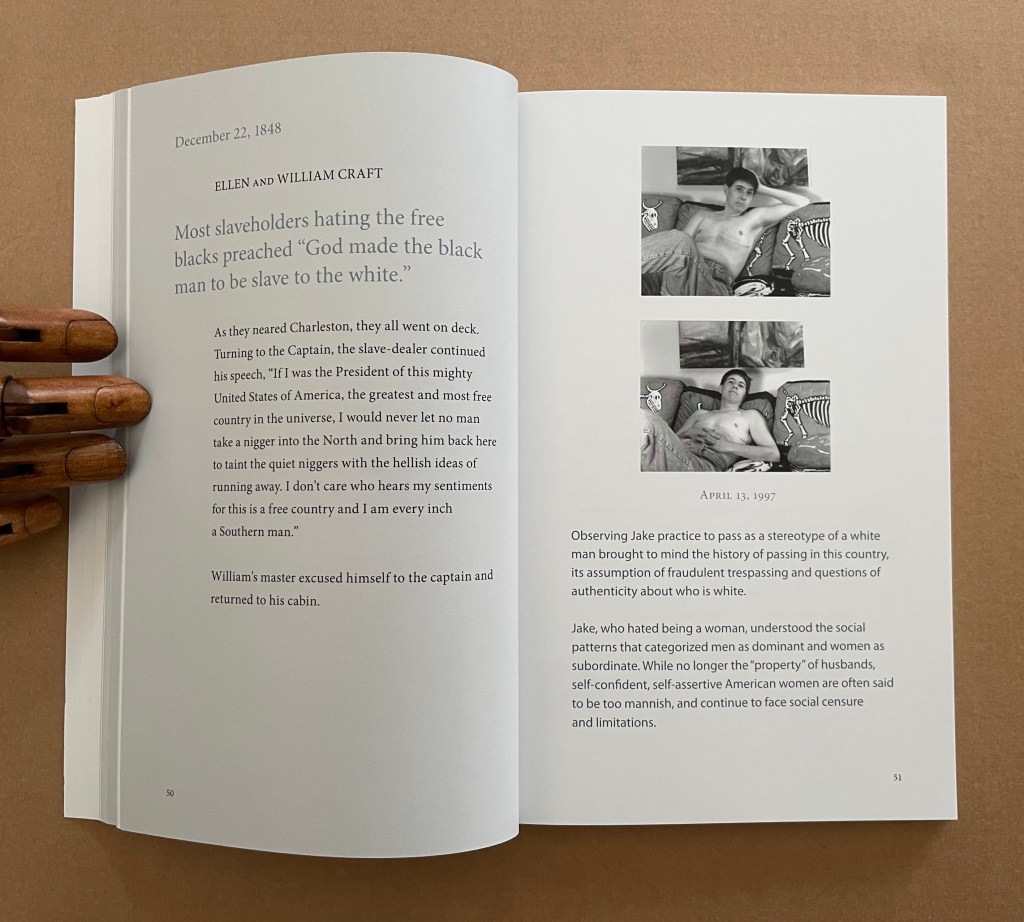

The next eight spreads establish the rhythm of entries from the Crafts’ story on the left and Deb/Jake’s on the right. Throughout the book, the latter is related by photos of the transition, excerpts of interviews with Jake, Jake’s journal, photos of friends, and excerpts of interviews with them. Throughout these eight spreads, Sligh is always present as photographer as well as juxtaposing book artist, but she reenters the foreground just after these spreads, and periodically, with journal entries ranging from her own memories of breast surgery to more communal ones of the practice of”passing” and the “place” of women in patriarchal society.

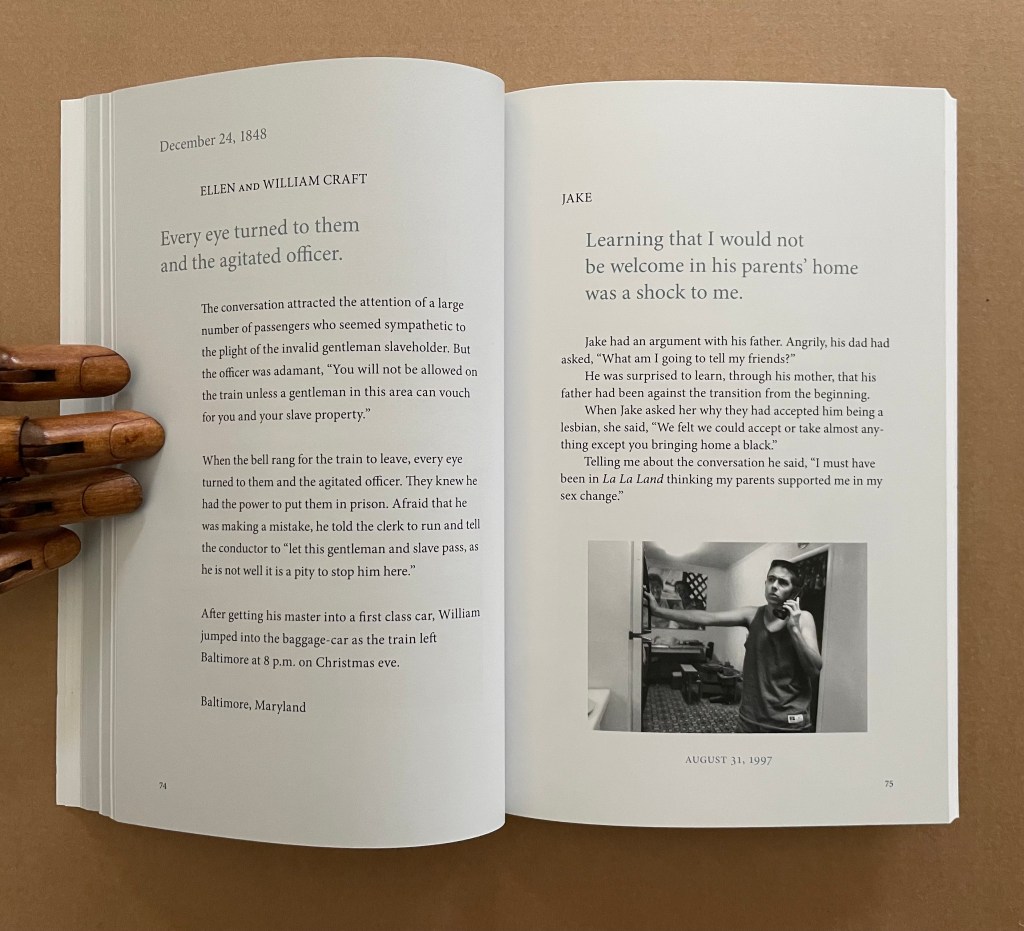

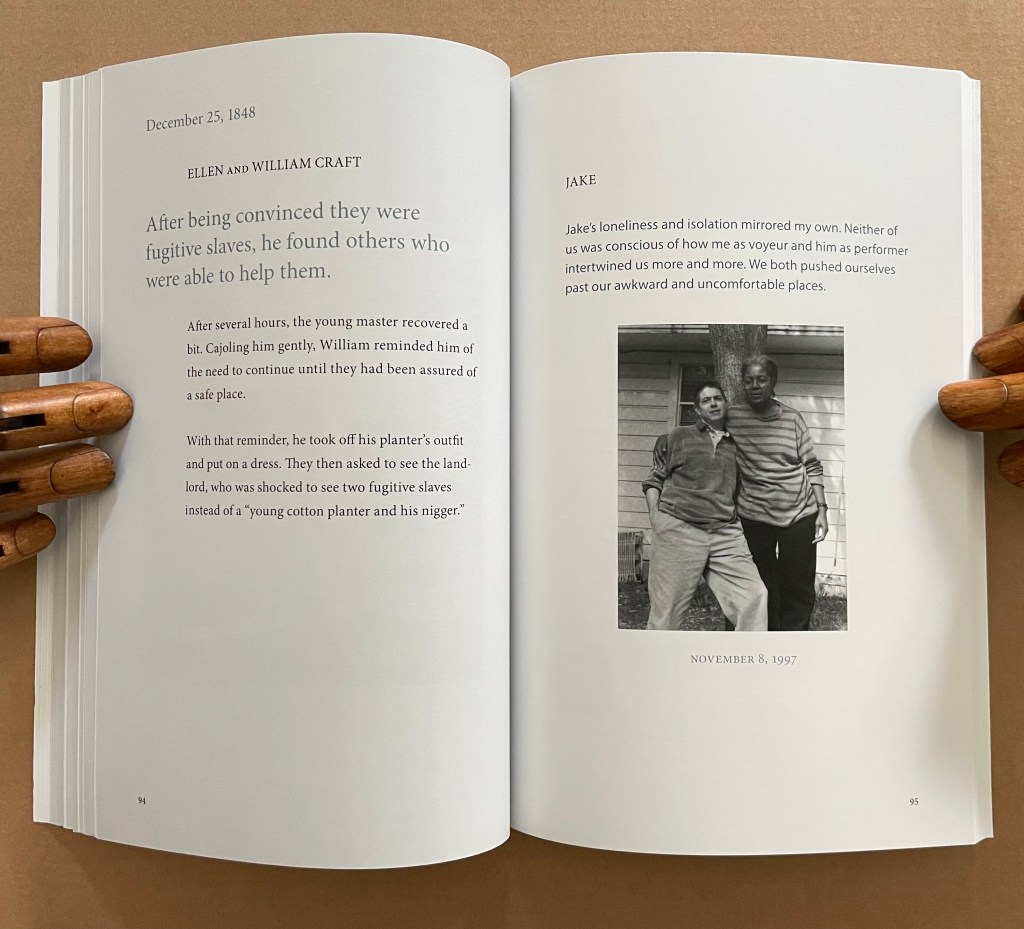

Perhaps these instances of foregrounding herself occur because she was worried that the juxtaposition of a female slave cross-dressing to pass as her husband’s white master with a late 20th-century female undergoing gender reassignment would not draw her readers’ empathy through the parallels being drawn. Perhaps she reckoned that foregrounding her own fears and struggle to come to terms with what she was witnessing would make it easier for readers to empathize. Perhaps she reckoned that sharing her awareness of passing and her experience of being treated as the “second sex” would make it easier for readers to accept the validity of the historical parallels being drawn with Jake’s situati0n. When mid-way through the book a shock brings Jake and Sligh into the foreground together, no reader — whatever race or gender — will fail to recognize the grounds for empathy and the validity of the parallels drawn among the Crafts, Jake, and Sligh.

This double-page spread with its juxtaposition of December 25, 1848 with November 8, 1997 is one of the most powerful strokes of book artistry in the Books On Books Collection.

Recall Sligh’s journal entry about the dinner meeting followed by the initial photo session? Alice’s remark “about how Deb has radically changed since beginning the testosterone” was the groundwork for the double-page spread below. For the testosterone-infused white reader, Jake’s recognition of his own misogyny and its parallel with racism should register as the proverbial kick in the balls. For any reader willing to ask the questions that Jake puts, the passage should delay any answer.

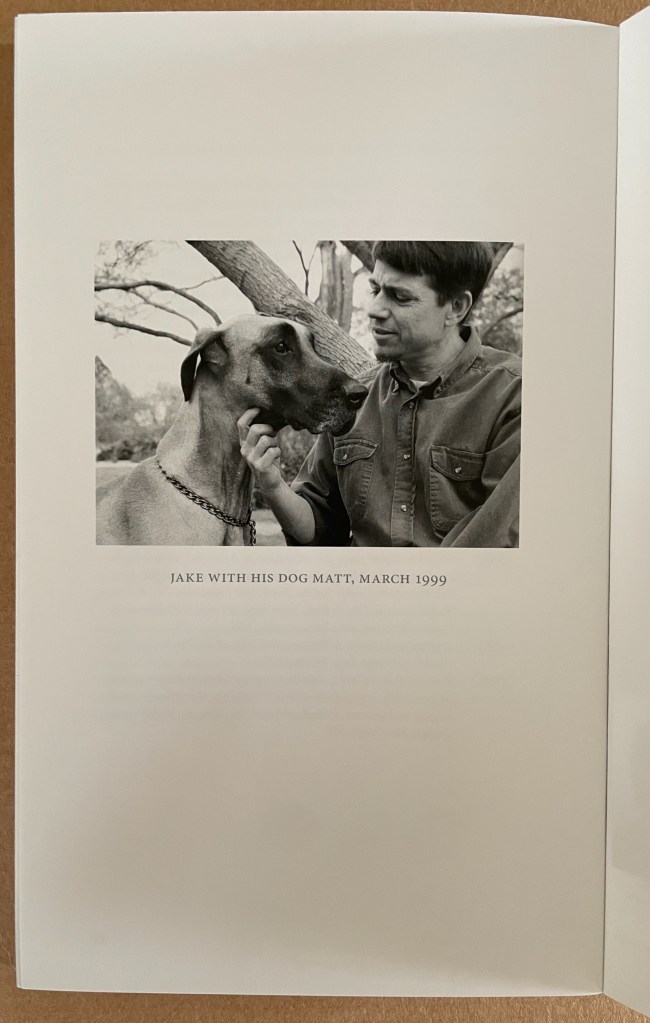

Wrongly Bodied is a complex artist’s book. If it had been available for Johanna Drucker’s consideration in 1994 for the first edition of The Century of Artists’ Books or early enough in 2004 for the new edition, it would have been an ideal candidate for inclusion in the chapters called “The Book as Sequence: Narrative and Non-narrative”, “The Artist’s Book as an Agent for Social Change”, or “The Book as Document”. It layers the Crafts’ narrative with Jake’s and with that of Sligh and Jake. As an agent for change, it addresses the social issues of gender dysphoria, misogyny, sexual discrimination, and racism. It documents the transition from Deb to Jake, it documents Sligh’s documenting, it documents the escape of Ellen and William Craft from slavery to freedom, it documents Ellen’s transformation into a white male slave owner, and it documents Sligh’s intertwining of Jake’s issue with the Crafts’ issue and her own issue.

Wrongly Bodied is uncomfortable not simply because of its depiction of Jake’s physical and emotional pain, or his partners’ and friends’ sense of betrayal, or the artist’s own struggle with the personal, racial and social issues evoked. It is uncomfortable not simply because of its compositional complexity, its multiple perspectives, and its multiple parallels. It is uncomfortable because it demands accepting and not accepting. It demands judging and not judging. If this is bewildering, then note the epigraph with which Wrongly Bodied begins:

Go back, look and read again.

Further Reading

“Clarissa Sligh (I)“. 2 September 2020. Books On Books Collection.

Bainbridge Island Museum of Art. 1 April 2023. “Celebrate with Us“. Artist’s Books Unshelved. Bainbridge Island, WA. Wrongly Bodied is discussed at 3″43″ in this video review.

Sligh, Clarissa. 23 October 2020. “Clarissa Sligh Lecture at Mills College.” Mills Art and Visual Culture. Voyage(r) is discussed at 34’38”. Wrongly Bodied is discussed at 40’20”.

Robert, I can’t believe a year and a half has passed since we last spoke at Codex. So much has gone on, both in my life and in the world. I am fortunate to be well, but at 70 find the hearing aids and glasses take time to work out to satisfaction. I have to confess I have been playing more music than spending time in the print shop. I am in 3 bands, 2 focus on 20-30s music, the other plays songs I have written. There is instant gratification when performing music, much like when giving a lecture or workshop, and in contrast to making a book. But there is real long term satisfaction in completing an editioned book that some find joy, pleasure, beauty or meaning in when they see it.

I also can’t believe I was not subscribed before and now am, and happy to be connecting with your inquiries on a regular basis.

Yours,

Peter

>

LikeLike

Dear Peter –

Great to hear from you. My photos and notes for Goodbye, Bonita Lagoon (2023) are still calling to me. The posting will include a note on 1,000 Artists’ Books (2012), which is as enjoyable for its taxonomy as it is useful for its reference function.

By the way, Ms Van Vliet sent me a bit of information about Praise Basted In that caused me to pick up on a subtlety that I think you will appreciate, especially as the choice of paper is the source of the subtlety. See the new paragraph about sister Dorothy Lyne’s birthday greeting.

You artists of the book are ingenious.

Cheers,

Robert

LikeLike