The Price of Words, Places to Remember 1−26 (1992)

The Price of Words, Places to Remember 1-26 (1992)

Lily Markiewicz

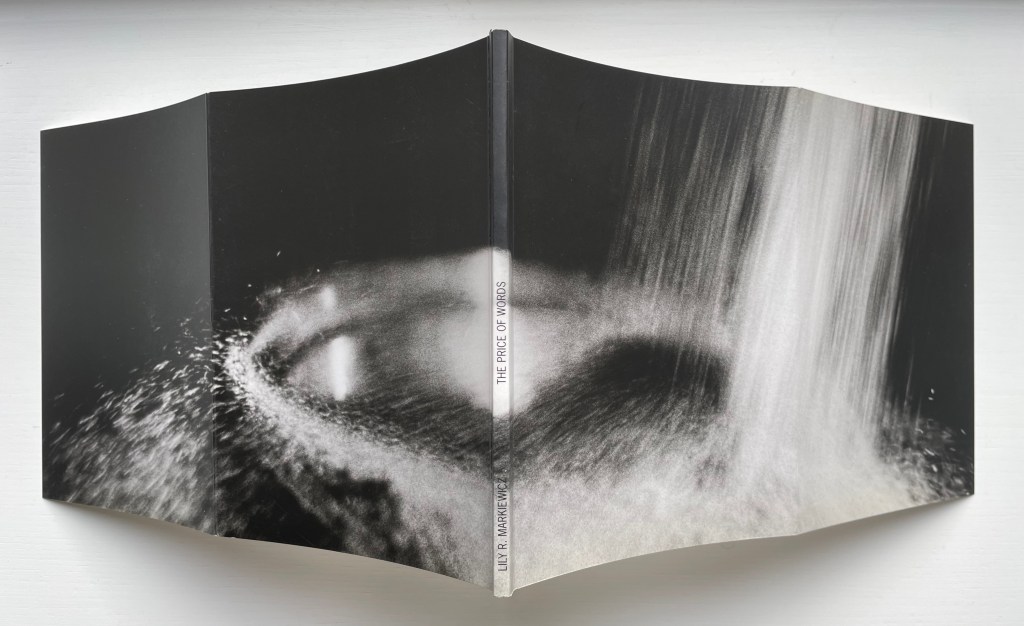

Perfect bound paperback with deep cover flaps. H200 x W155 mm, 60 pages. Acquired from Bookworks, 11 July 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection and Emilia Osztafi*. Displayed with artist’s permission.

The Price of Words is an amalgamation of two archetypal forms of the book: the alphabet book from which children learn to read and the memory book. The book’s subtitle Places to Remember 1−26 links the alphabetical plan of the book to the injunction to remember, so important in Judaism and Jewish culture. The ‘places’ are pages of the book, though reference is made within them to actual places − lived in, moved from, arrived at, passed through, never named or identified. Black and white photographs that show sand pouring into a metal bowl preface the alphabetical section of the book. These images have an ambiguous quality, caught between movement and stillness, negative and positive. The book is not a straightforward memorial observance: it addresses the need within Jewish culture not only of the importance of remembering but of the need to forget.— Publisher’s description.

Words, places, and memories all have a “price”: they have value, but also demand something in exchange. As the publisher’s description says, the book is not simply a “memorial observance”. It observes the power of words over and above places in Jewish culture, and the need both to remember and to forget. Much like her 1997 installation piece, Promise II, this piece works with the idea that traumatic memory is not remembered in a linear way, but experienced in the present, both in time and place. As Markiewicz says in her essay “No Place – Like Home” (2007), “boundaries between a then/now and a there/here are dissolved” (p. 43). In The Price of Words, the process of putting memory into words necessarily involves the present.

Markiewicz grew up in Germany as the daughter of non-German Jewish Holocaust survivors, and later migrated to England. For a long time, she was called by the idea of artistic practice as a dwelling, or at least “a sense of housing oneself “– an attempt to translate the German verb wohnen, which can mean dwelling, living, residing, inhabiting, and (in German) evokes “both an at-homeness and a feeling comfortable”. But, as she discusses in the essay, making art might mean “losing oneself, or becoming unaccommodated“. In creating places, even if conceptualised as “places-to-be”, she often creates “places to be or become unaccommodated in” (pp.38-9). Markiewicz works with “domestic, low-resolution production methods”, and her images are of simple, natural subjects, in local and familiar locations. Yet they evoke “something more unfamiliar, gesture towards something unknown, hidden”, which we might be drawn to but also threatened by (p.45). At the same time as her work creates a space for the viewer to enter, it also denies us access to that space.

Her 1995 installation piece, Places to Remember, consisted of “a temporary construction within an already enclosed space”, in which speakers are hanging from the ceiling, and we hear a female voice echoing from one speaker to the next, filling the space with “the imperative to remember” (p.39).

The black and white photographs of sand in that installation – charged with associations of time, and the building of earth and desert – are also printed in The Price of Words, in the four double-page spreads preceding the alphabet text. One image shows a bowl surrounded with sand, floating and unfixed. The sand might be gathering and building, like the words and memories we hope to build from the letters of an alphabet, or it might be spilling out, the bowl slowly emptying.

The text that follows is sequenced as an ABC, a formal structuring device rather than a thematic one – like language itself, which might guide a reader through an otherwise non-linear work. Johanna Drucker draws a distinction between artists’ books which are narratively sequenced and those in which linear sequence has no narrative significance (Century of Artists’ Books, pp. 257-284). Although the individual letters in The Price of Words do not correspond to specific hidden meanings, this sequencing of discrete items (letters of an alphabet) gives each piece of the sequence a place, a significance, or even a “price”. In traditional Jewish thought, the 10th letter of the Jewish alphabet, yod, is thought to be the singular starting point for all words. From words, we make worlds: ideally, words are a place, a “dwelling”, to be inhabited. But words can be left unspoken, and dwellings uninhabited – or partially, uncomfortably inhabited.

Physical places, words, and their record on paper are made to overlap, for instance in the letter K, which begins, “Armed with maps, organised like the tedious lines of an old and futile argument, I take to the streets.” Here, the “tedious lines” are simultaneously the lines on a map, the paths they represent, and the worn-out “lines” of speech and rhetoric. This individual letter, like many others, embodies a place, but it is beyond reach: “I go in search of stones, ancient and beautiful, which remind me of some other place.” We move on, still searching, to L, “(Always another place)”, and then somewhat later, Q, “The place where I have been is as though I have never been there”.

Q is rich with sensory experiences of the present, which hold what the memories themselves cannot. Speech and language become tactile and corporeal: “My tongue is charred and still I chew my words and hold them tight and press my lips together, so as not to let anything escape.” Words are physically real, both as “marks; notations” on a page, and as “instruments of meaning, powertools” (M). To learn the alphabet is to gather the components which make up these tools, whether they form weapons or remedies.

At the end of the alphabet (Z), memory and learning to read are explicitly connected – “They say that what you read is your memory and your becoming” – and then pulled into the negative, into the impossible: “I ask you what you cannot read – read.” This final word might work as an imperative, “now read”, or it might be an extension of the “read” in “cannot read”, stretched out and dispersed across the dash, promised but not entirely fulfilled. Even by the end, we can only begin to learn to read.

*Entry written by Emilia Osztafi.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

Caruth, Cathy, Ed. 1995. Trauma, Explorations in Memory. Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press.

Drucker, Johanna. 1995. The Century of Artists’ Books. New York: Granary Books.

Felman, Shoshana and Laub, Dori. 1992. Testimony: Crisis of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History. London and New York: Routledge.

Hirsch, Marianne. 1998. “Past Lives: Postmemories in Exile”. Ed. Susan Suleiman, Exile and Creativity. London: Duke University Press.

Hirsch, Marianne. 2002. “Marked by Memory: Feminist Reflections on Trauma and Transmission.” Extremities; Trauma, Testimony and Community. Eds. Nancy K. Miller and Jason Tougaw, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Jabès, Edmund. 1985. “There is such a thing as Jewish writing.” Ed. Eric Gould, The Sin of the Book. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

Jabès, Edmund. 1987. The Book of Questions, Vol. 1 (Trans. Rosemary Waldrop). Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

Markiewicz, Lily. 2007. “No Place – Like Home.” Thamrys/Intersecting No. 17: 37-48.

Rehan, Ernest. 1990. “What is a Nation” (Trans. Martin Thom). Ed. Homi K. Bhabha, Nations and Narration. London and New York: Routledge.