Because he works with so many different materials, it is hard to classify Julien Nédélec as an artist: A polyfabricant? With language play being a more or less constant theme: A polywright? His website labels him a plasticien, the perfect French word that captures more of the media in which he works than its usual translation “visual artist” does. In Zéro2, Antoine Marchand writes:

Everything, with him, is subject to manipulation, appropriation, and diversion, at times in the most trivial and basic way imaginable. His work is based on permanent mischief, a desire to destabilize the viewer, and be forever creating a slight discrepancy, which barely ruffles the reading of the work—well removed from the showiness of many present-day productions. He bypasses the daily round and takes us towards somewhere else that is not that far away, but all the more joyful. … What should incidentally be underscored in this young artist’s praxis is his ability to move from one medium to another, without the slightest bother or apprehension. It is impossible to pigeonhole Julien Nédélec’s praxis in any one particular medium.

Several of his works have been hosted on the Greek island of Anafi by the Association Phenomenon and the Collection Kerenidis Pepe, whose website also notes that his

practice can take many forms, from sculpture to drawing, through books and photography, with a predilection for the paper, that he uses not only as a support, but also as a material that he bends, cuts, colors, stacks or crumples. His works are the result of linguistic and formal games that reveal the artist’s fascination with the potentialities of language, with a malice that places him as an heir apparent of the Oulipo, while his taste for geometric and serial shapes brings him closer to the tradition of minimalism.

With paper as a favorite medium, there are a handful of artist’s book among the many other forms. Taken together, his artist’s books almost make up an anthology of homage to book artists from the 1960s to the present. He also belongs to the school of appropriators embracing forerunners like Bruce Nauman, Richard Prince, and Richard Pettibone and contemporaries like Michalis Pichler, Antoine Lefebvre, and Jérémie Bennequin, all of whom have embraced the self-reflexive artist’s book as an appropriate medium for appropriation. No wonder Galaad Prigent’s Zédélé Éditions, the French publisher that hosts Anne Moeglin-Delcroix and Clive Phillpot’s Reprint Series of artists’ books, is so fond of his bookworks.

TER (2021)

TER (2021)

Julien Nédélec

Softcover, saddle stitch with staples. H240 W165 mm. [36] pages. Acquired from Zédélé Éditions, 21 September 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with the artist’s permission.

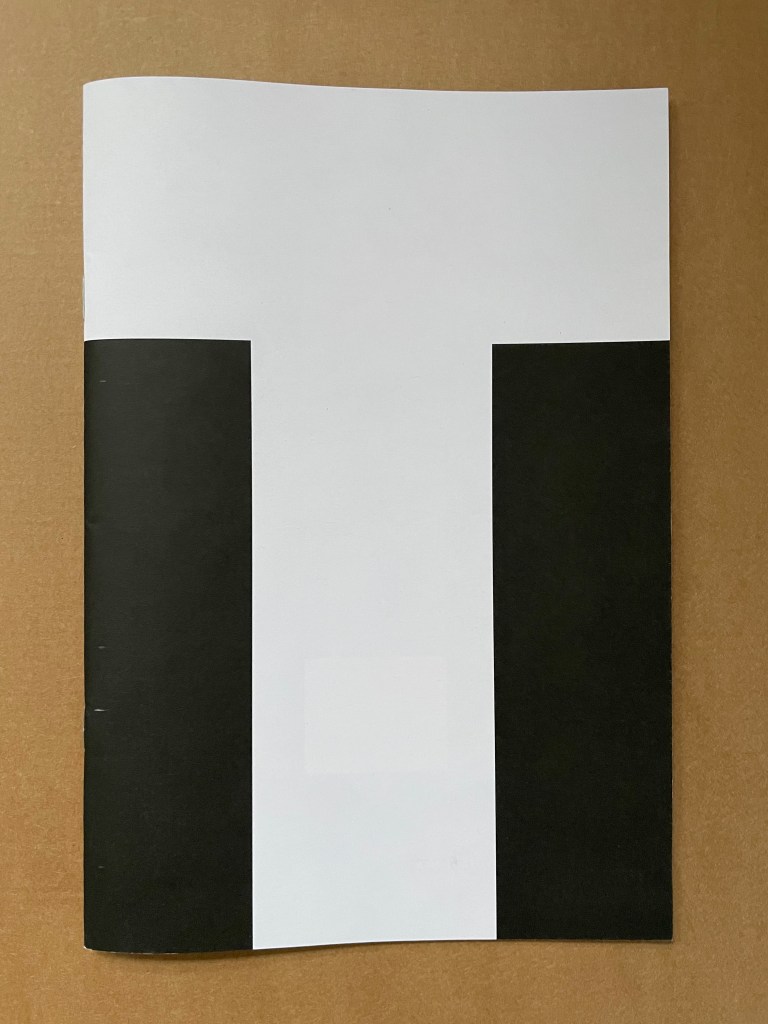

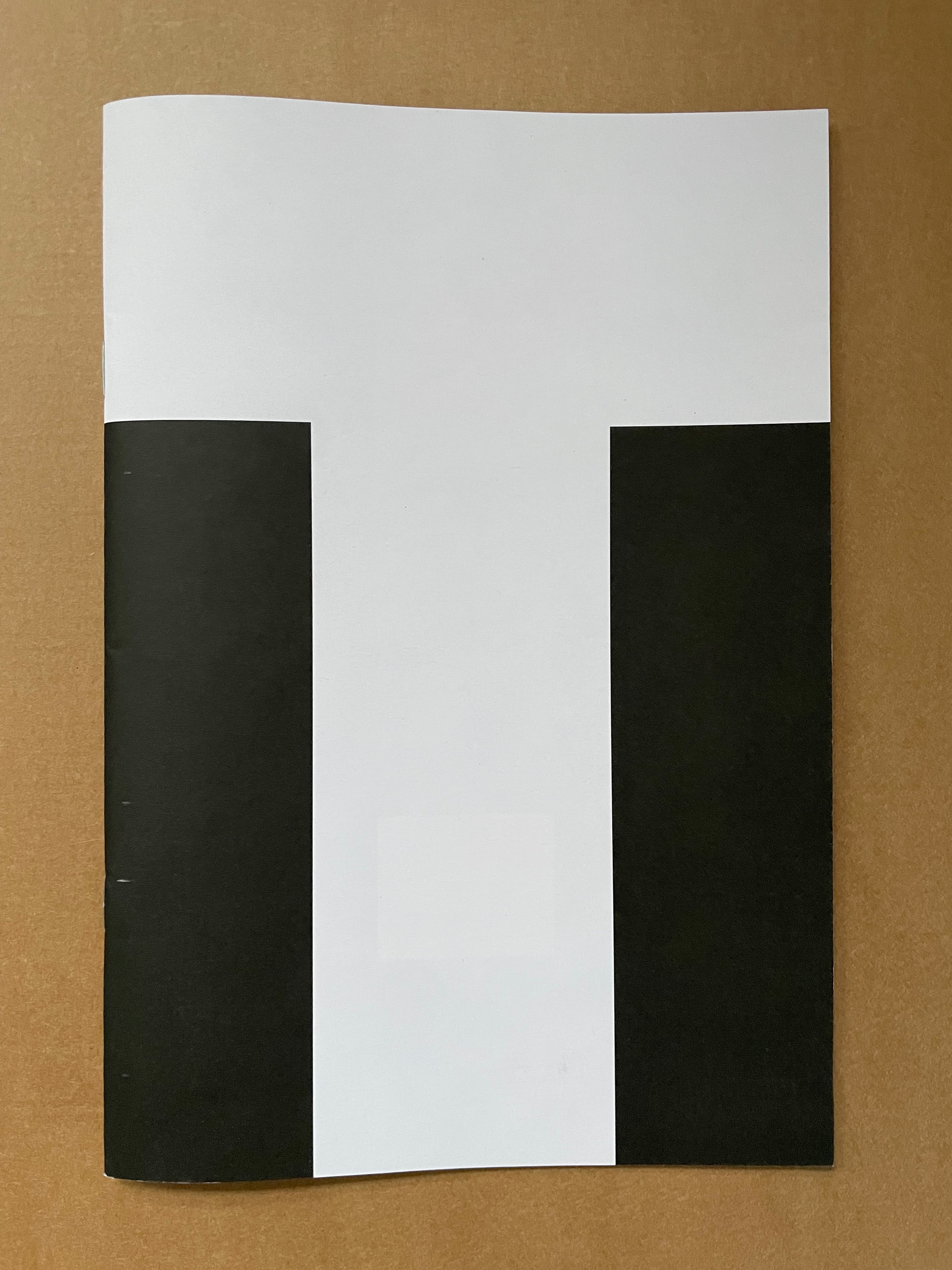

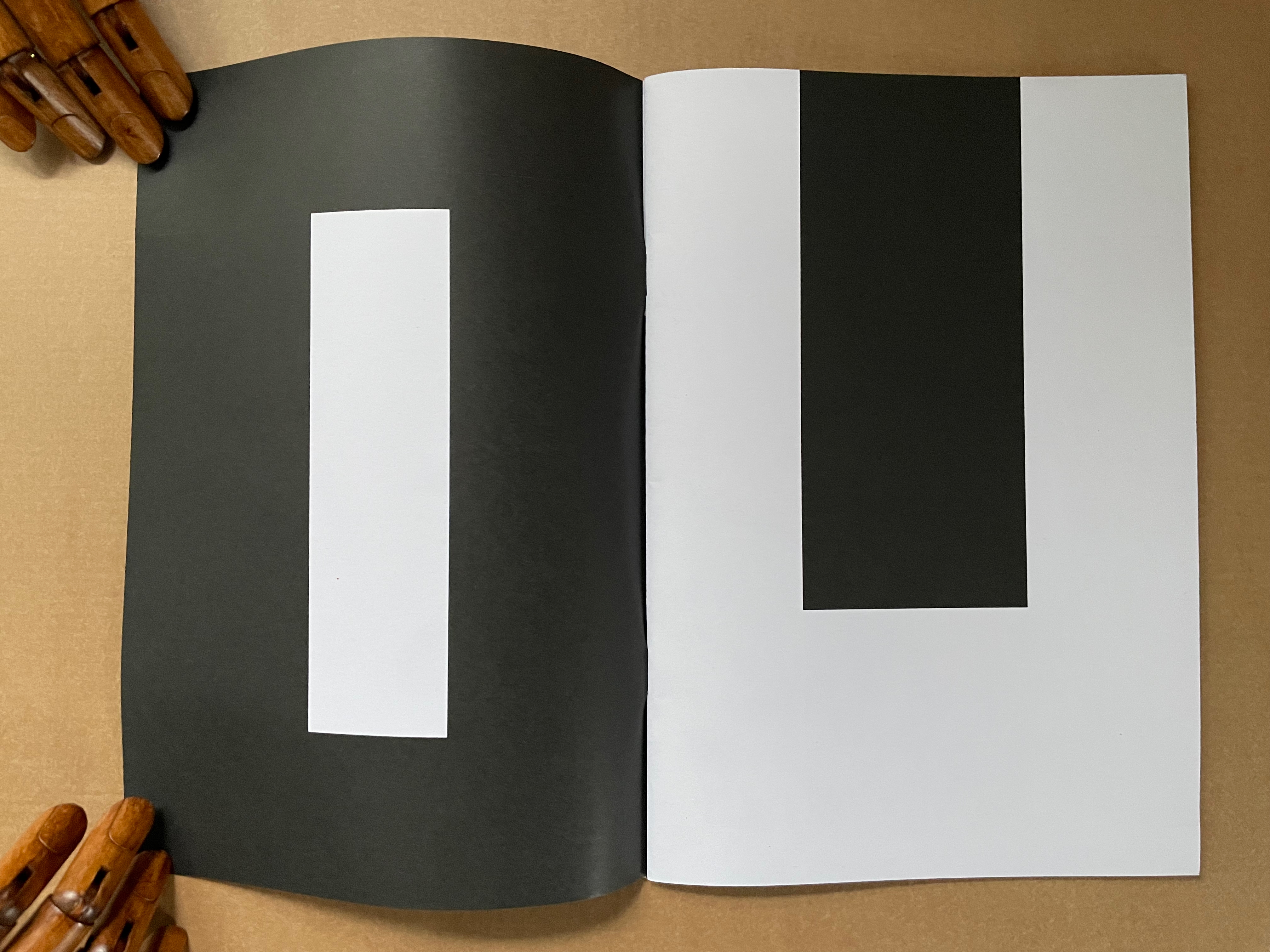

“Tout”

The sentences to be deciphered from these full-page-bleed letters are Tout a été redit. Tout a été refait, which, in English, would be “Everything has been said. Everything has been done.” But it also has the echoes of a French children’s song, “Tout ce que je fais“:

Tout ce que je fais,

Mon âne, mon âne,

Tout ce que je fais,

Mon âne le refait.

Tout ce que je dis,

Mon âne, mon âne,

Tout ce que je dis,

Mon âne le redit.

Everything I do,

My donkey, my donkey,

Everything I do,

My donkey does it too.

Everything I say,

My donkey, my donkey,

Everything I say,

My donkey says it too.

Given Nédélec’s mischievousness and propensity to appropriate, perhaps the echo of the children’s song is somewhat a case of the mockingbird mocking himself for his appropriations. Asked about this, Nédélec replied, “I don’t know that song, but yes it’s about ‘don’t worry about what was done and do it in your own way'”.

Given that another of Nédélec’s earlier works, Lignes de train (2011), is the story drawn of a train journey from Nantes to Rennes, we can’t ignore that TER stands for Transport express régional, one of the rail systems in France. But ter is also French slang for district/area/block, and we can’t ignore his installation Blocs (2015), 213 inked blocks of wood corresponding to the 213 text blocks in Julien Gracq’s book La forme d’une ville (“The Form of a City”).

Blocs (2015). Photos: Courtesy of Julien Nédélec.

But in correspondence, the artist points out that TER is Latin for “three times”. Like BIS for “twice” and QUATER for “four times”, TER is a Latin-based numeral adverb, or multiplicative adverb. So what about TER is “three times”? It appears to be something as simple, coincidental, and Oulipoesque that the expression “Tout a été redit. Tout a été refait.” has a total of 36 characters, spaces, and periods (full stops) to occupy the 36 pages of the book, giving Nédélec a self-reflexive object with which to not worry about what has already been said or done and to say and do it his own way.

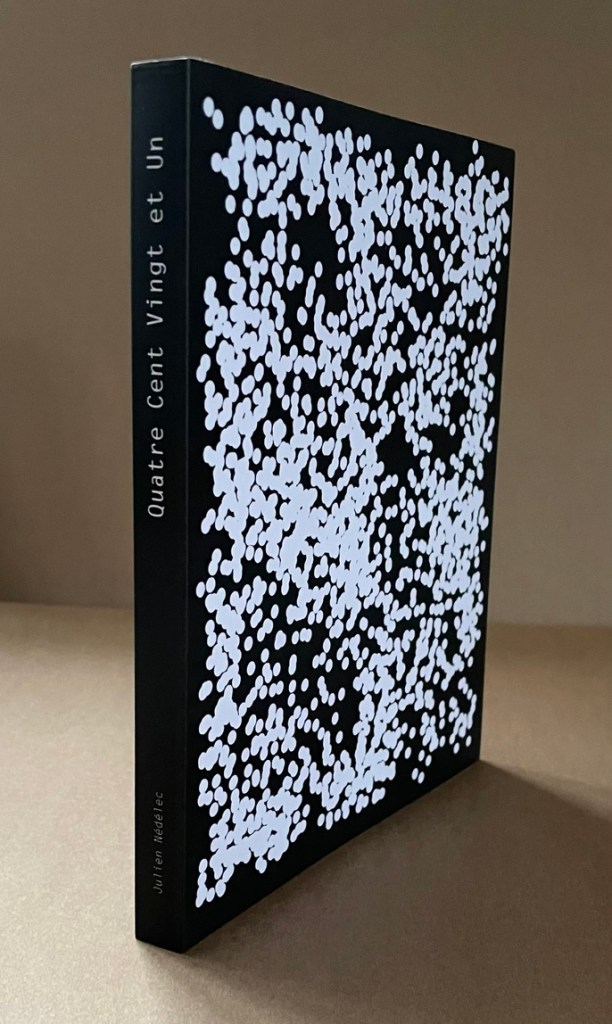

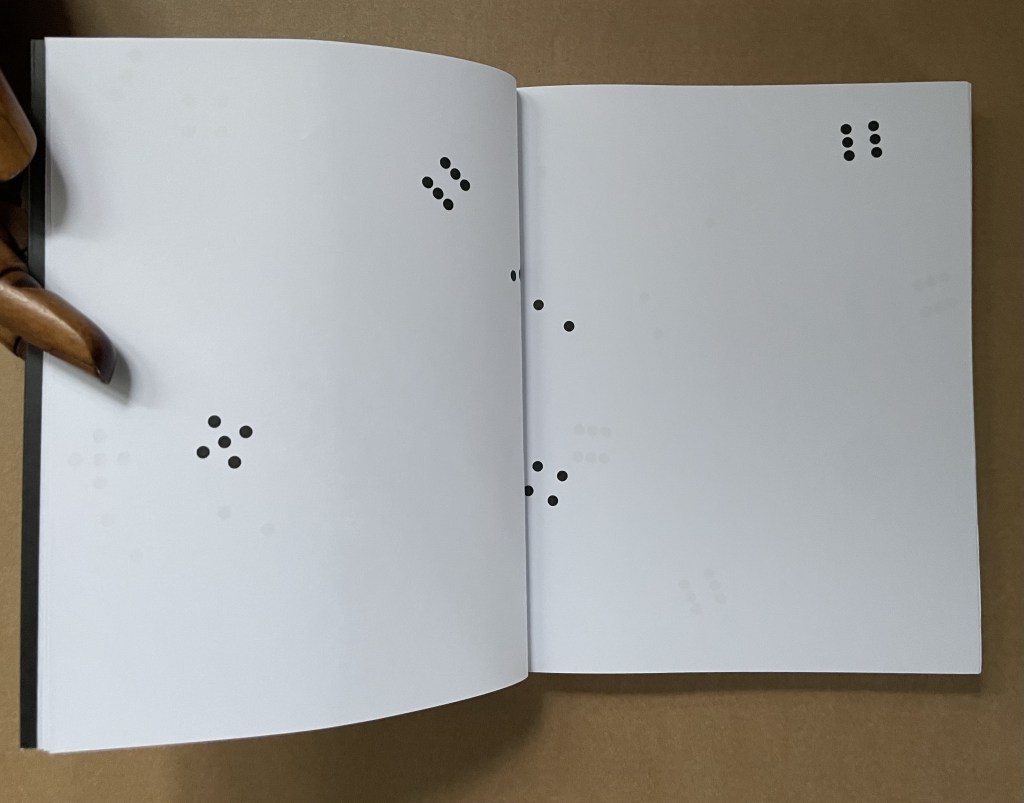

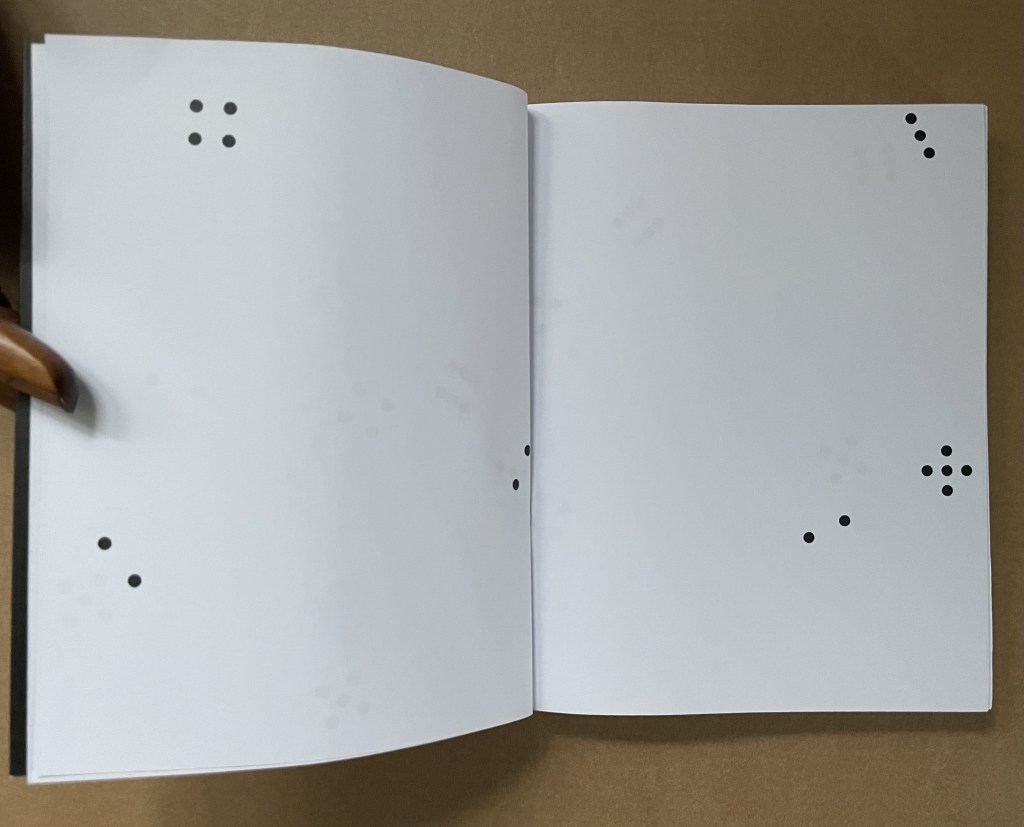

Quatre Cent Vingt et Un (2021)

Quatre Cent Vingt et Un (2021)

Julien Nédélec

Perfect bound paperback. H175 x W140 mm. [216] pages. Acquired from Zédélé Éditions, 21 September 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with the artist’s permission.

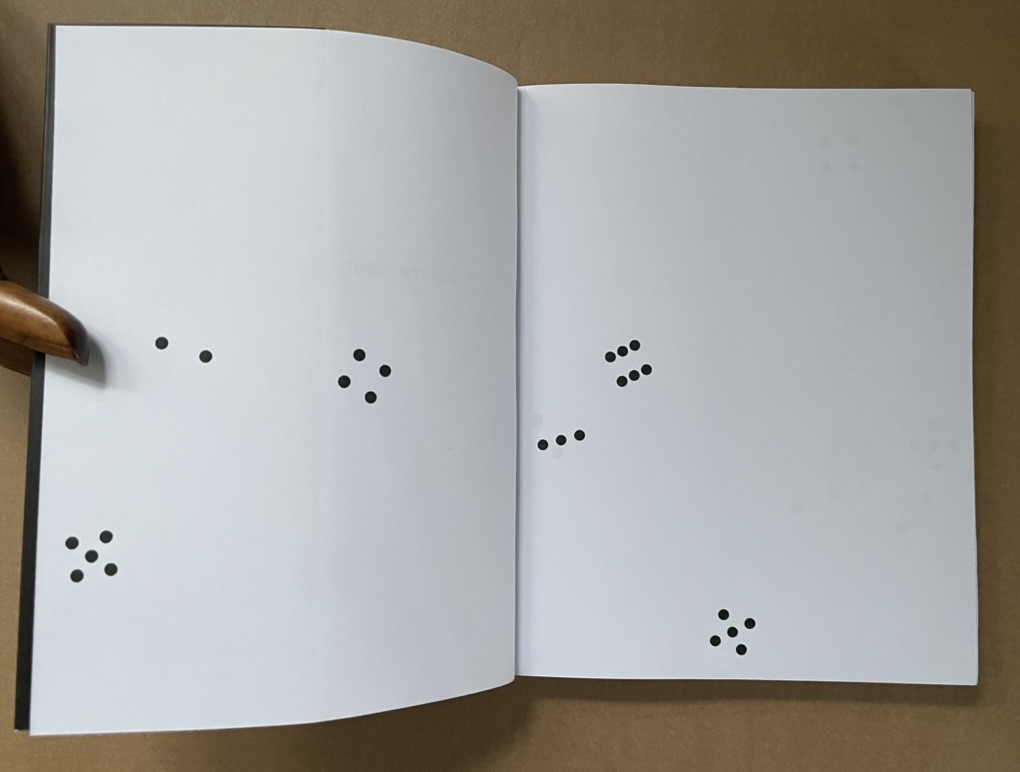

The title refers to a well-known dice game in France. Each page shows the spots of three dice, and the book contains all the dice rolls that were necessary for the author to achieve all the possible combinations with 3 dice (56 different combinations).

Achieving all the possible combinations is not the point of the game, so might this Oulipoesque rule-driven book also be a nod to Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés N’abolira le Hasard (1897)?

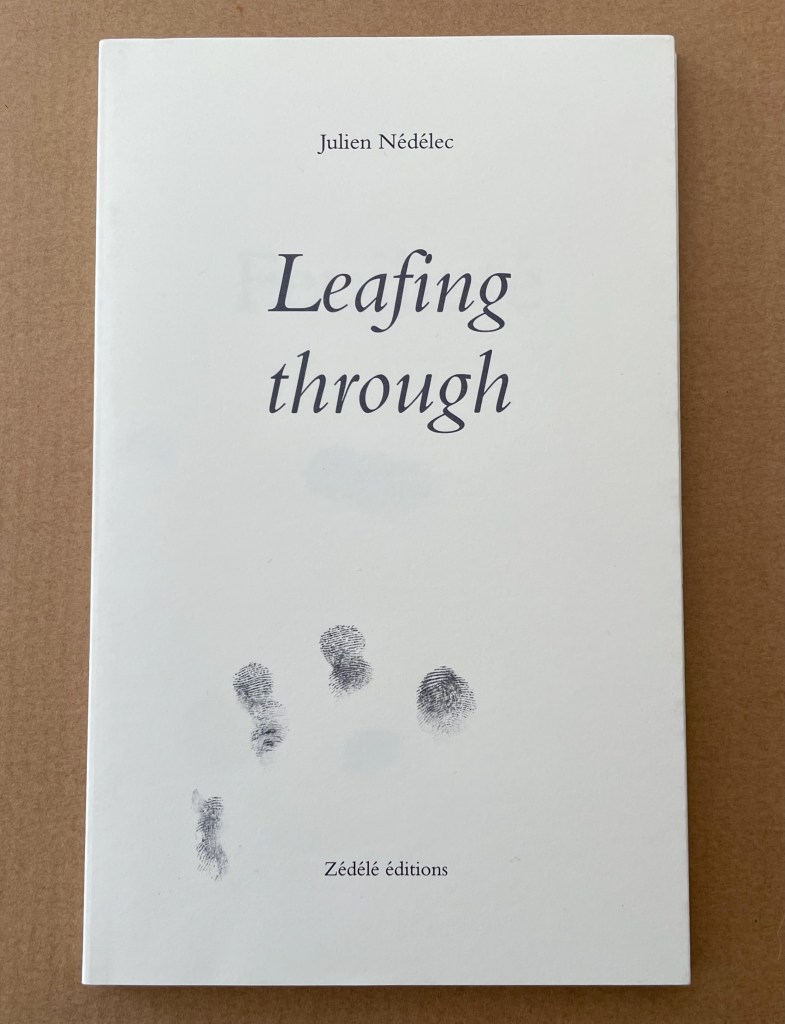

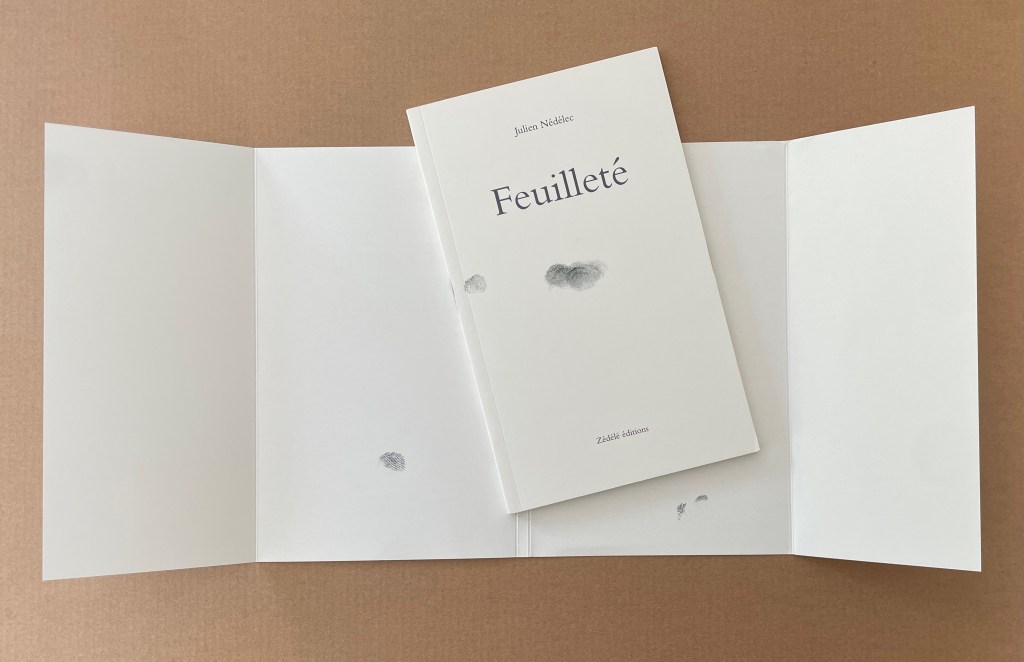

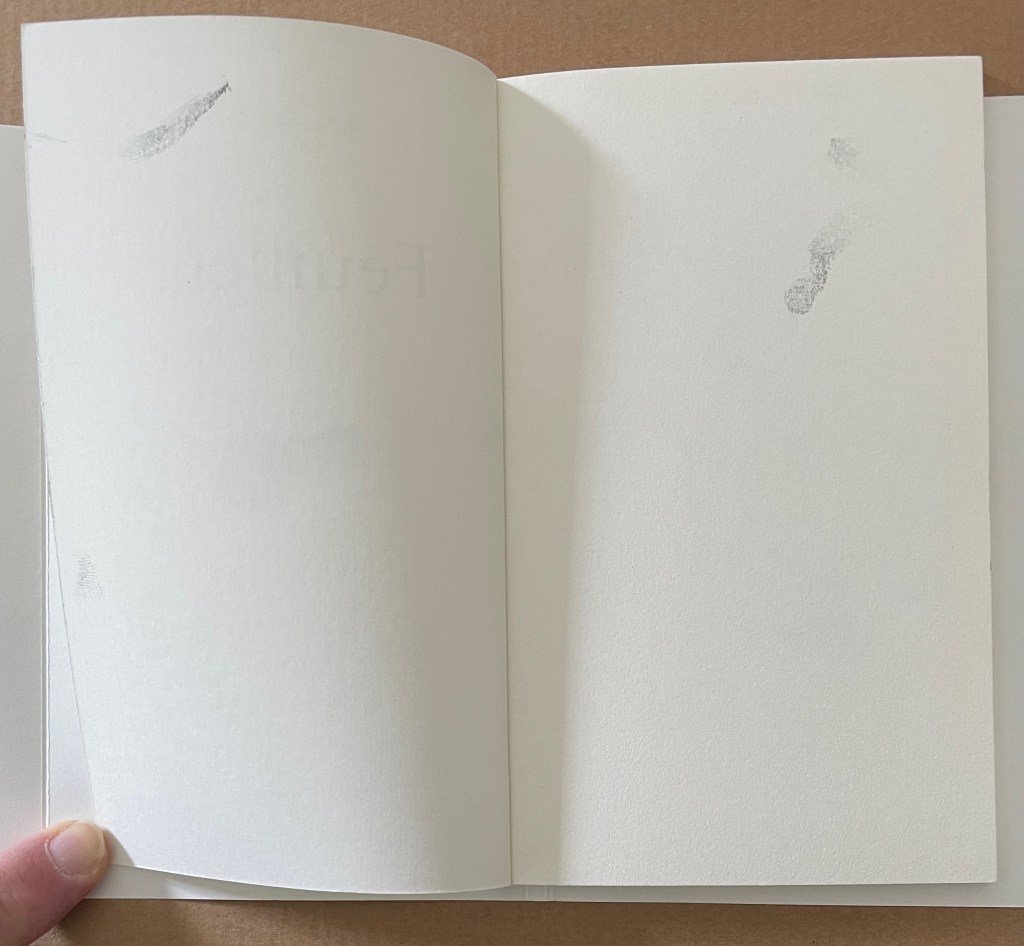

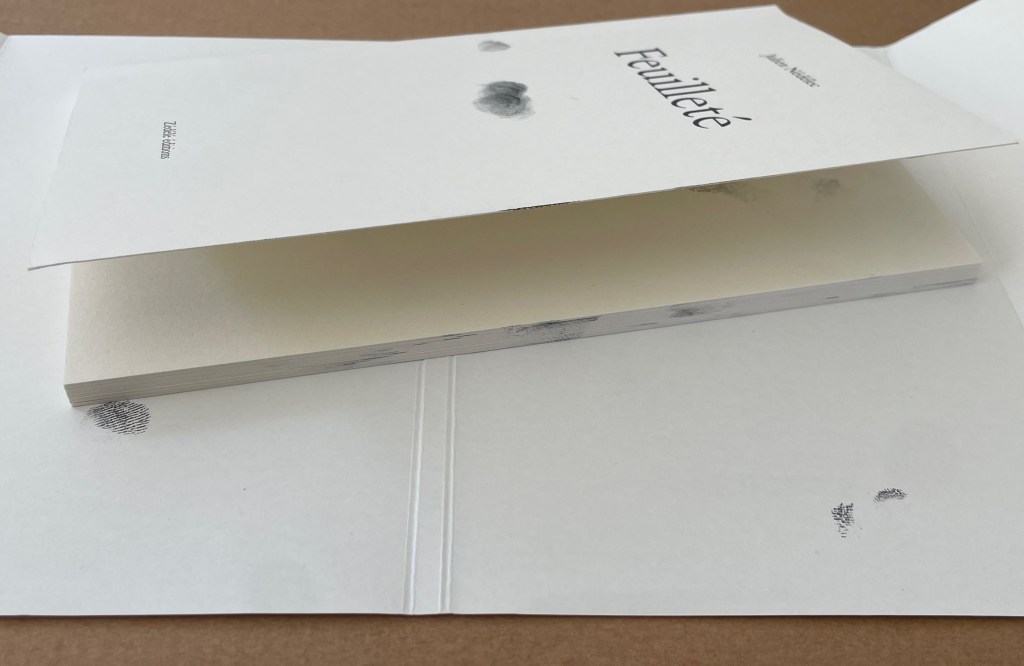

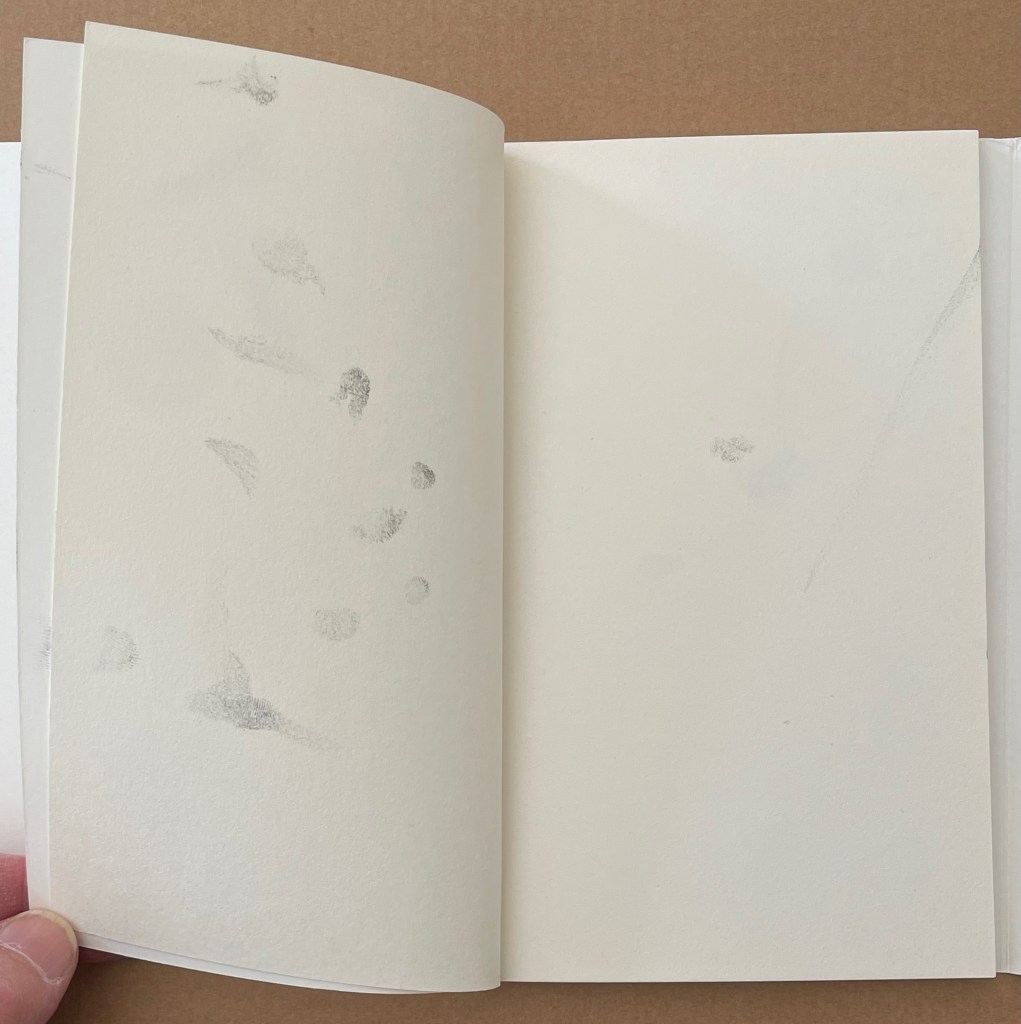

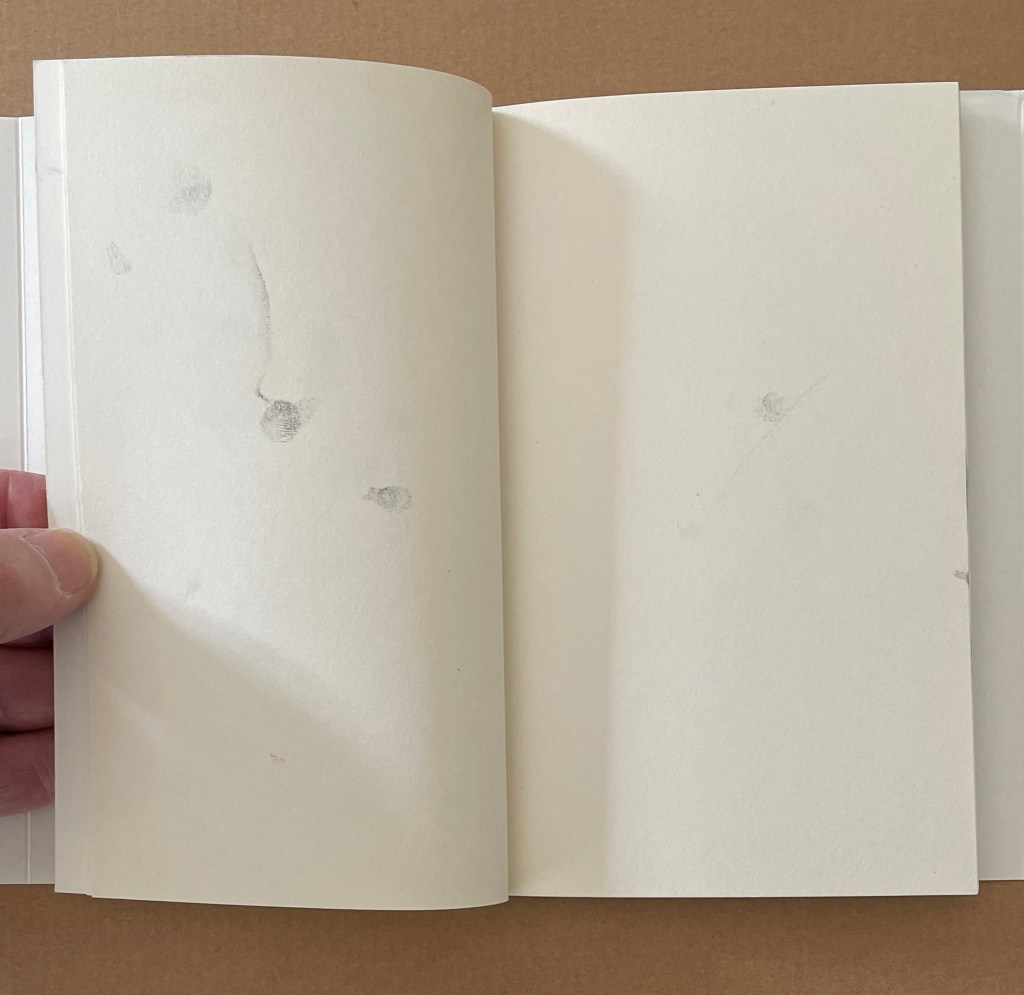

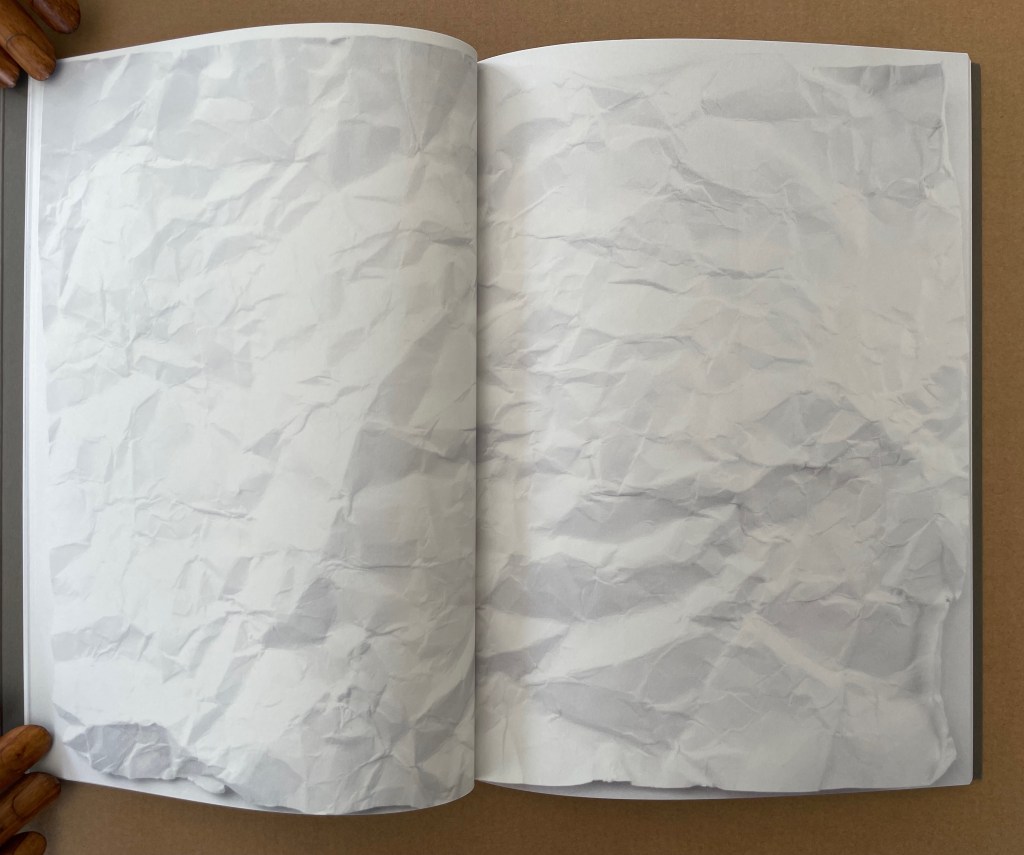

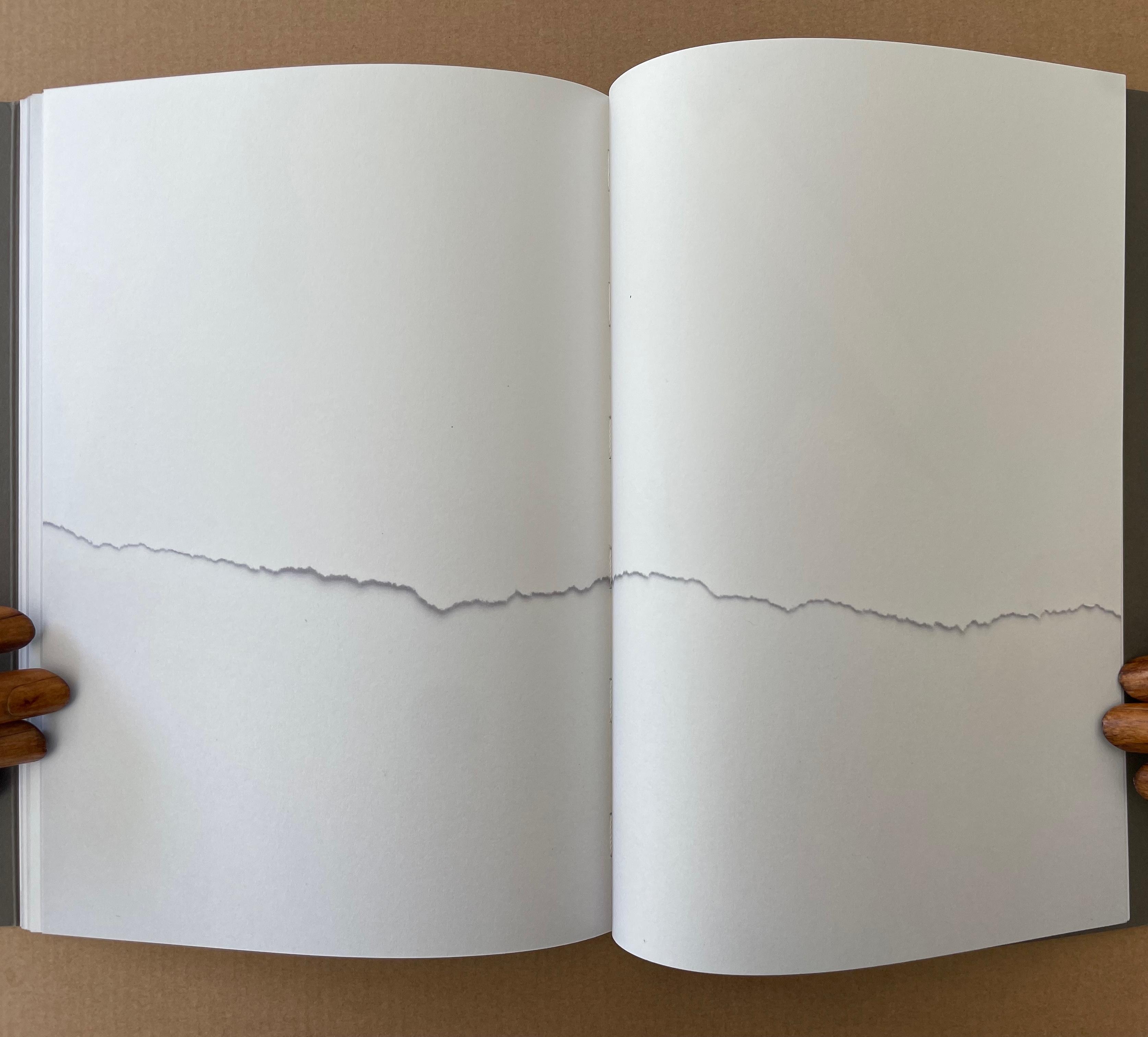

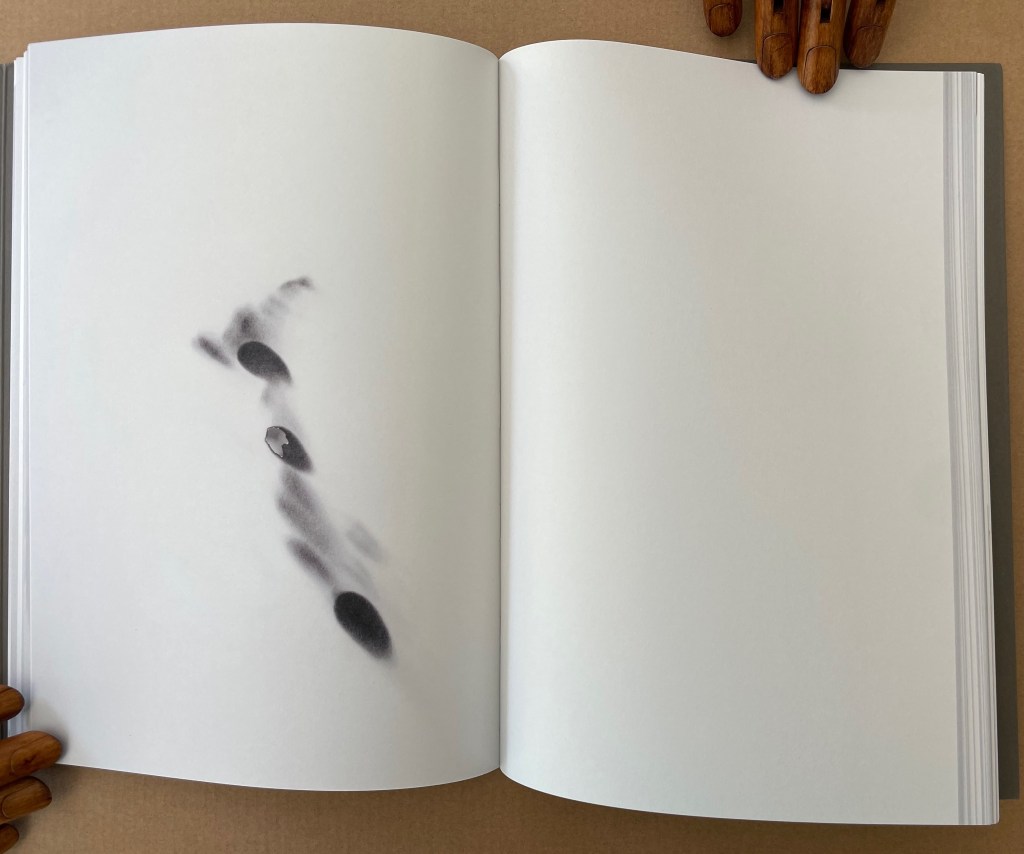

Leafing through (2013)

Leafing through (2013)

Julien Nédélec

Dust jacket with deep flaps around perfect bound paperback. H185 x W115 mm. [48] pages. Acquired from Zédélé Éditions, 9 May 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with the artist’s permission.

More self-reflexive mischief here. It’s like a simple sentence of Subject-Verb-Object except it’s a tautological jumble of SOV. The subject is the act of browsing or leafing through. The object is the blank book browsed or leafed through. The only evidence of the verb are the inky fingerprints which have acted on the object, altering it and making it into the subject.

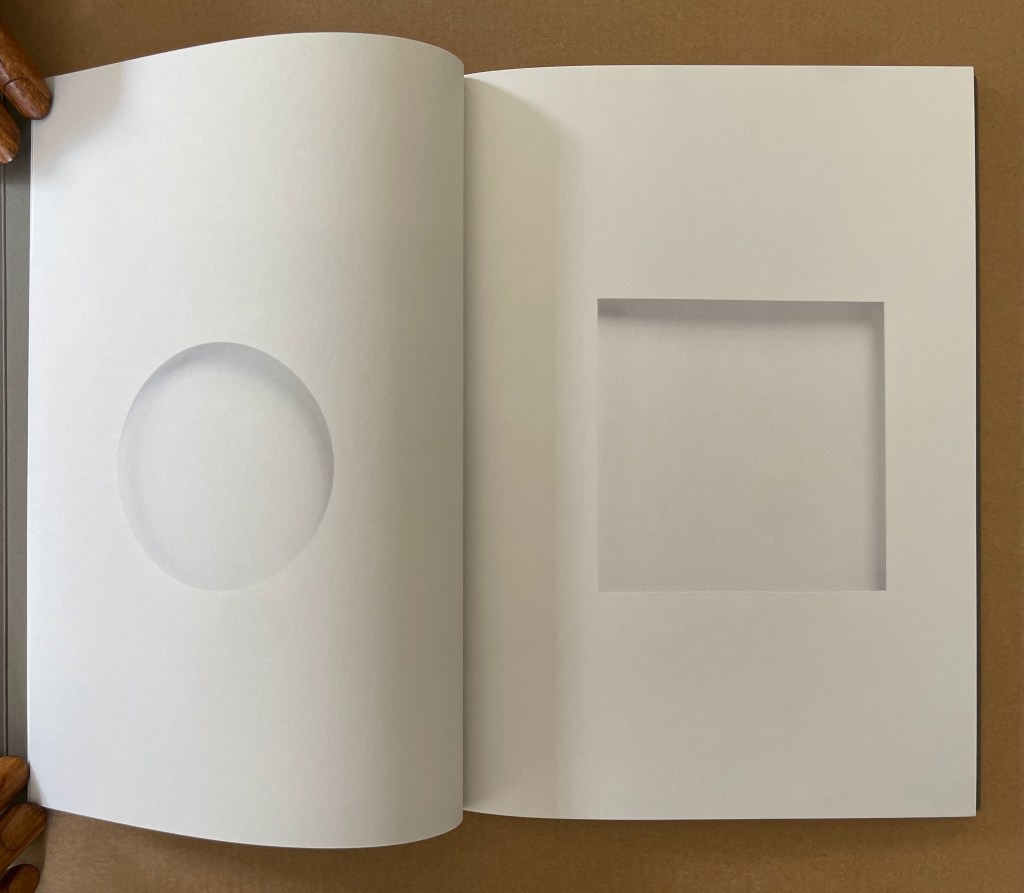

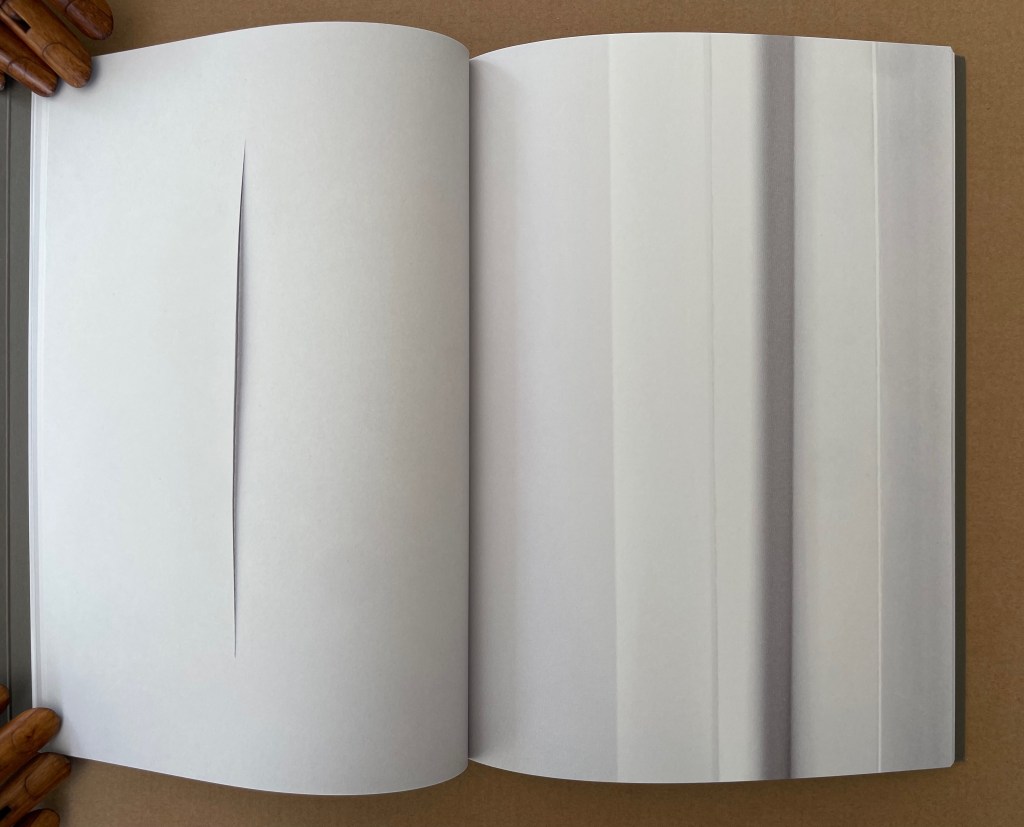

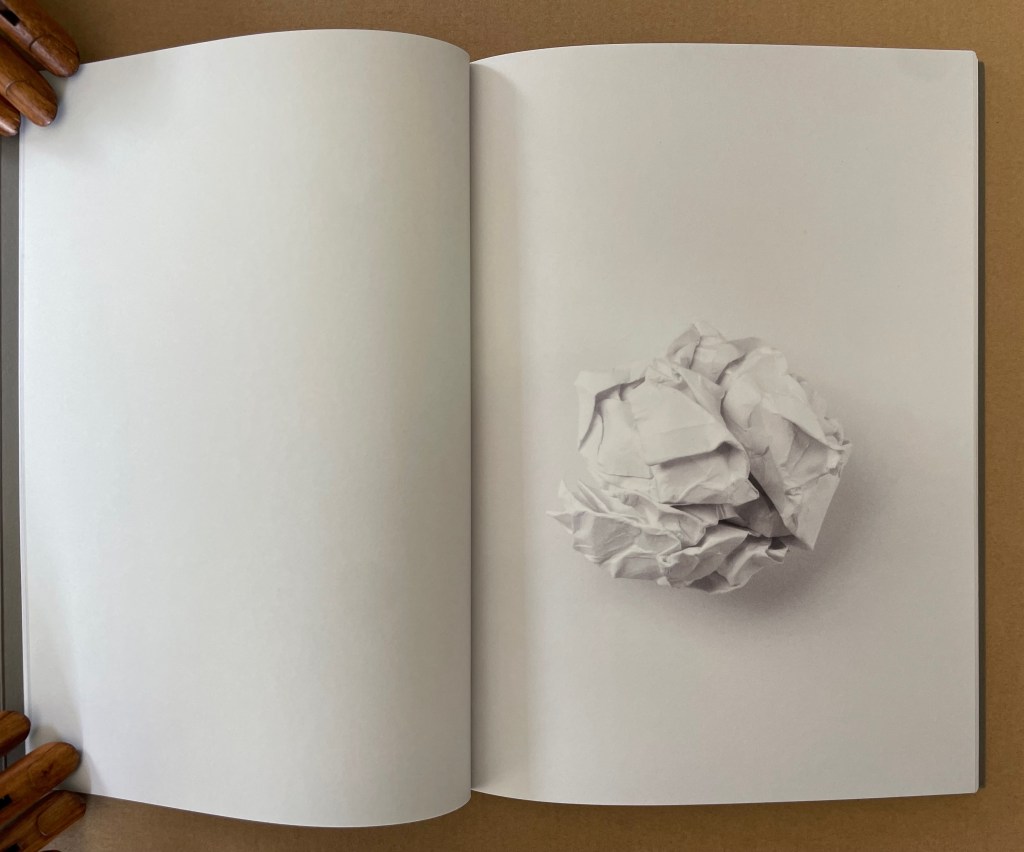

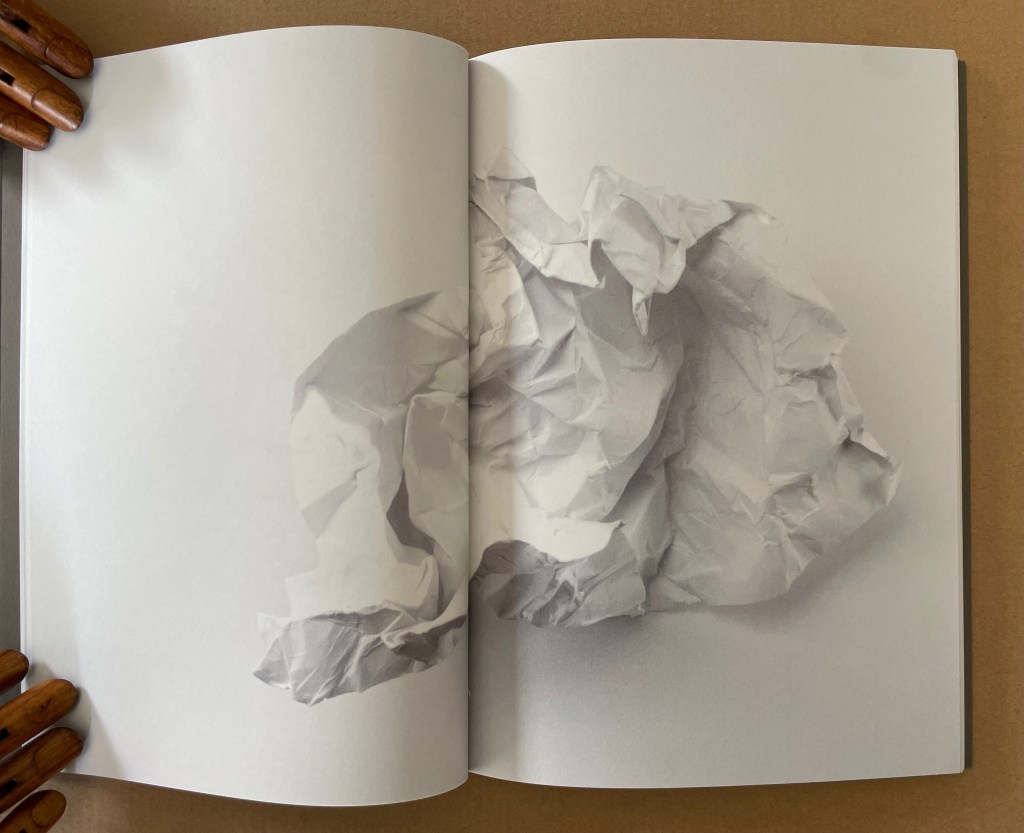

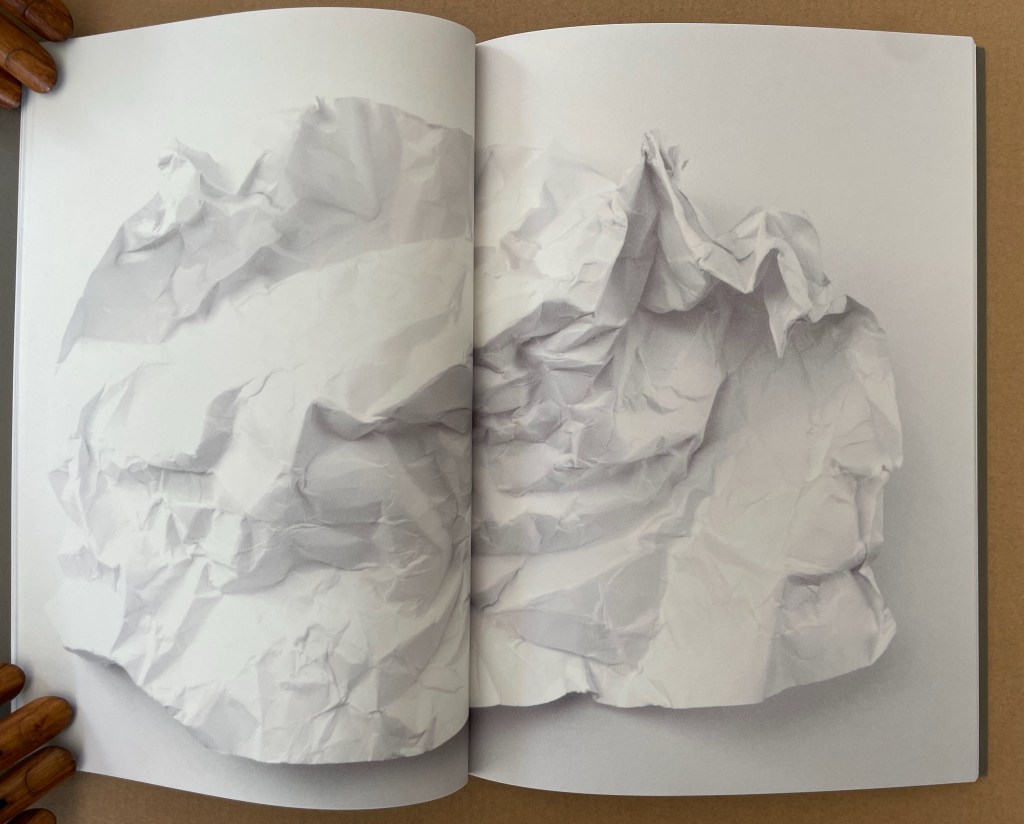

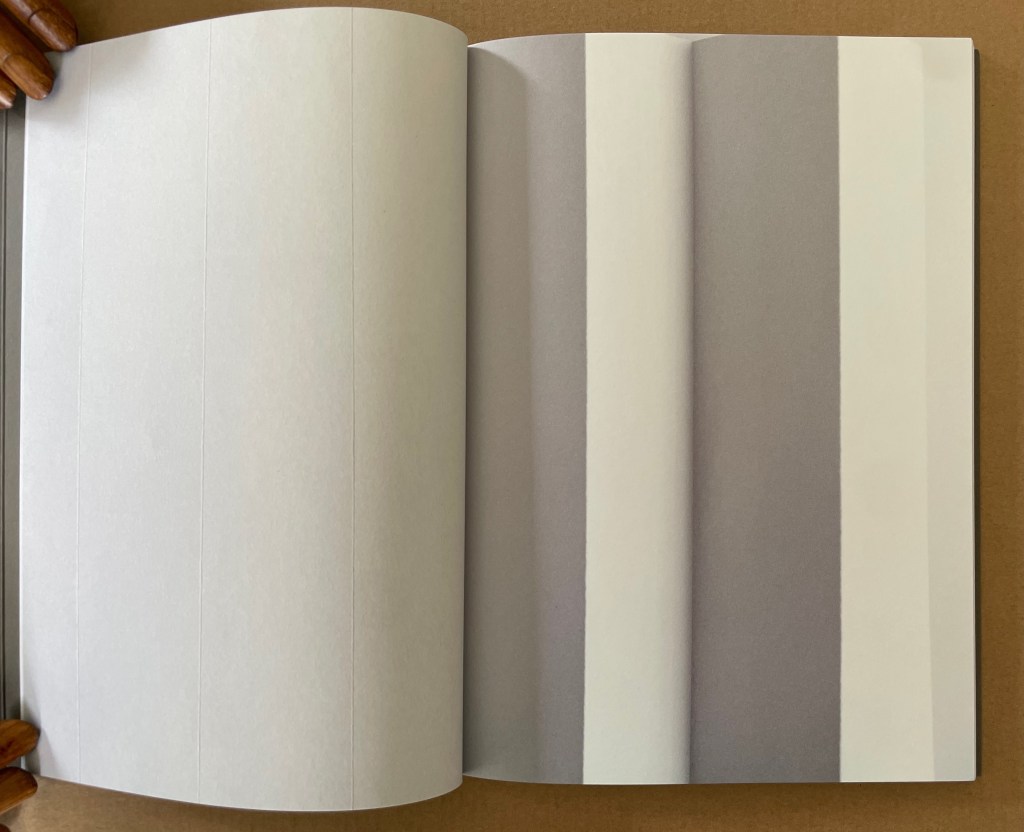

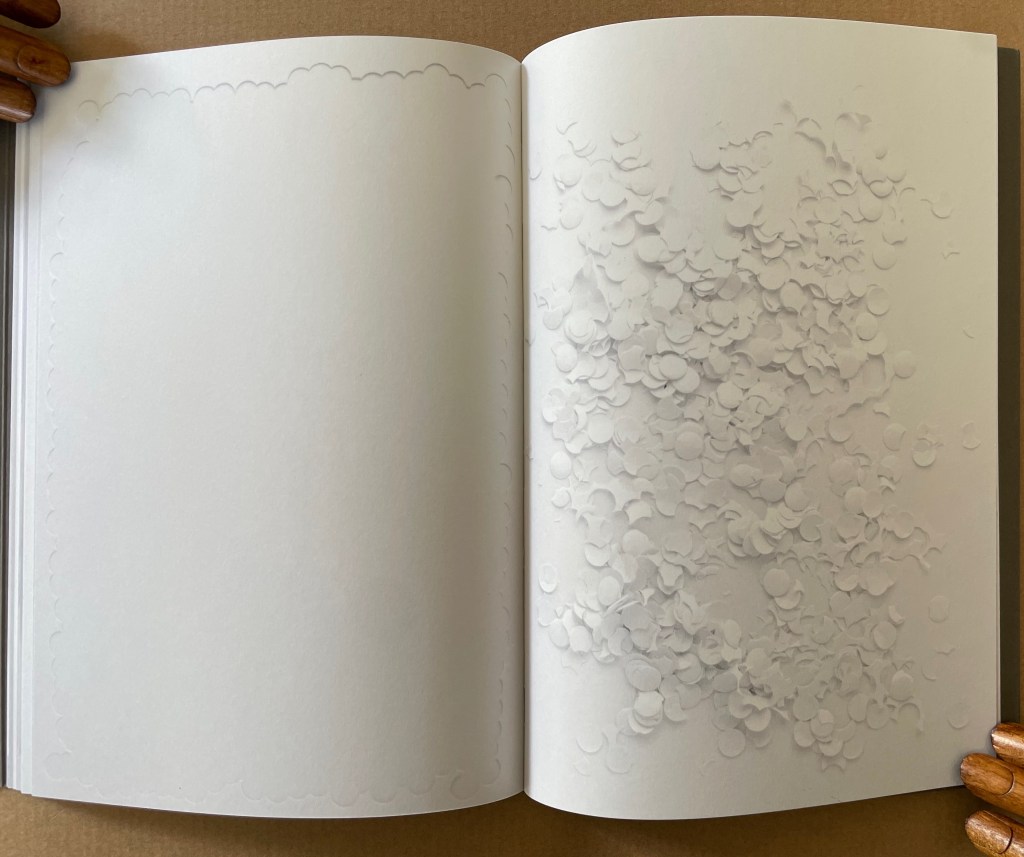

Titrer (2012)

Titrer (2012)

Julien Nédélec

Embossed card cover with deep flaps around perfect binding. H240 x W171 mm. [64] pages. Acquired from Zédélé Éditions, 21 September 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with the artist’s permission.

“In 1967 and 1968,” says Richard Serra about Untitled (Verb List), “I put together a list of verbs as a way of exerting different actions on unspecified materials. Roll, bend, twist, shorten, hover, tear, slash, split, cut, slice. Language structured my actions in relation to the materials, which had the same function as transitive verbs.”

In turn, I made my own list of action verbs applying to my practice, and more specifically to my relationship with paper: Turn, Split, Tear, Cut, Mask, Decompose, Section, Find, Wet, Fold, Titrate, Enlarge, Roll, Duplicate, Look, Support, Corner, Pick up, Fold, Crumple, Shorten, Move, Find, Repair, Swivel, Dirt, Burn, Crease, Chew, Raise, Recompose, Bend, Stack, Grease, Reproduce, Reduce, Look, Lift,. ..

This list is a working protocol. I use it to apply simple actions to paper, turning it into sculpture. — Artist’s statement, cover.

In addition to its homage to Richard Serra, Titrer could also be paying homage and “forward homage” to numerous paper artists and book artists.

Homage to Sol LeWitt?

Homage to Anish Kapoor’s Wound (2005)?

Homage to Martin Creed’s Work No. 301: A sheet of paper crumpled into a ball (2003) or Rutherford Witthus’s Crumpling a Thin Sheet (2007)?

“Forward homage” to Andy Singleton’s Fabric II (2017), Fabric III (2017), Silk(Draped) (2018) and Silk (Falling) (2018)?

Homage to Julie Johnstone’s A Book of Tears (2006) or Field (2014) or “forward homage” to Tim Mosely’s A Book of Tears (2014)?

“Forward homage” to Linda Toigo’s Medieval and Modern History (Suggestions for Further Study for Jack Hroswith) (2013) or Zaida Oenema’s Burnings (Variations) (2018)?

“Forward homage” to Mathilde van Wijnen’s Ruimte [Space](2017)?

Homage to Jenny Smith’s Book of Beads (2008)?

Titrer is a nearly encyclopedic homage to paper art, but more than that, it is a self-assured, self-reflexive artist’s book to be leafed through again and again — with clean fingers!

Further Reading

“Inscription 2 on Holes“. 29 May 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Looking Back and Forward from the Paper Biennial 2018“. 24 June 2018. Bookmarking Book Art.

Bruce, Kathy. 2013. Crease, Fold & Bend. Easton, PA: Lafayette College Art Gallery.

In Extenso. 2013. “Julien Nédélec: Ockham’s Razor“. Exhibition. Clermont-Ferrand: In Extenso.

Kerenidis, Iordanis, and Piergiorgio Pepe. 2016. “Julien Nédélec“. Paris and Athens: Association Phenomenon and the Collection Kerenidis Pepe.

Küng, Moritz (ed.). 2023. Blank. Raw. Illegible: Artists’ Books as Statements (1960-2022). Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König. See p.34.

Malfettes, Stéphane. 22 January 2013. “Introducing : Julien Nédélec”, Artpress No. 397.

Marchand, Antoine. N.D. “Julien Nédélec: from all angles“. Zéro2. Nantes.