Pantographia (1799/2022)

Pantographia, Containing accurate Copies of all the known Alphabets in the World (1799/2022)

Edmund Fry

Casebound in Italian Fedrigoni Imitlin, sewn book block, black endpapers. H215 x W140 mm. Acquired from Black Letter Press, 1 April 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

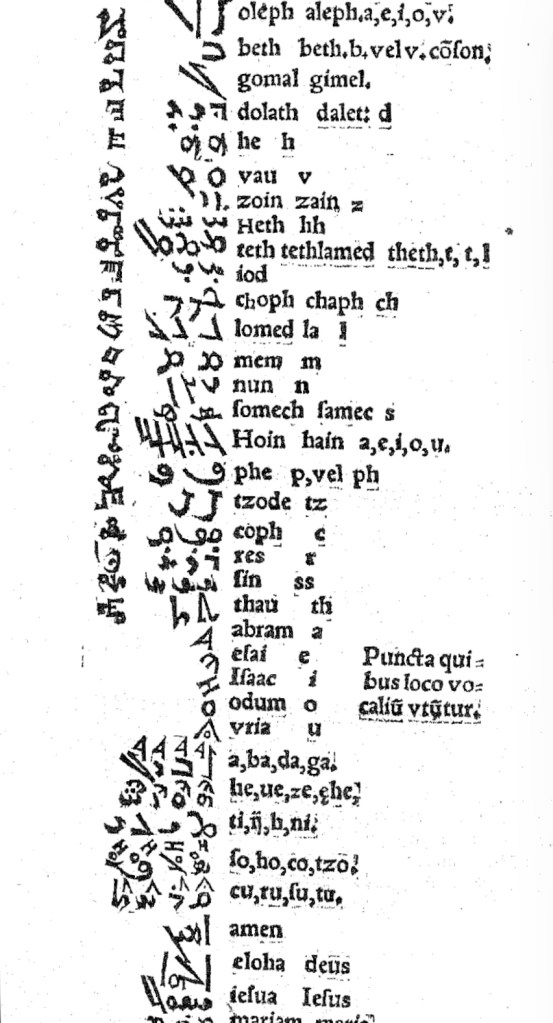

For the Enlightenment, everything that existed was meant to be in an encyclopedia. For Dr. Edmund Fry, scholar, typographer and owner of The Polyglot Foundry, this notion (and the spur of profit) led to his Pantographia (1799). Extraordinarily, Fry made the matrix for each of the roughly 5,000 characters for the 405 alphabet specimens, then handcast each — a monumental sixteen-year accomplishment in craftsmanship. Quite a type sampler for a printer specializing in foreign languages.

Fry was also driven by the importance of the subject: the origin of speech, its being made visible and the varieties of doing so. “The art of drawing ideas into vision, or of exhibiting the conceptions of the mind, by legible characters, may justly be deemed the noblest and most beneficial invention of which human ingenuity can boast — an invention which has contributed, more than all the others, to the improvement of mankind.” (xviii)

Fry is even handed in presenting the arguments and evidence for and against the two possible origins of speech he identifies — divine gift or human invention. He is unequivocal though “that all languages … that have been conveyed in alphabetical characters, have been those of people connected ultimately or immediately with the Hebrews, to whom we are indebted for the earliest specimens of the communication of ideas by writing” and “that there was but one truly original language, from which all others are derivations variously modified”. (xxxviii, xliii)

Plenty has been written about Fry’s accomplishment. Johanna Drucker has explored it in her Alphabetic Labyrinth and more recent Inventing the Alphabet. Even more recently, Hunter Dukes, editor of The Public Domain Review, posted a brief celebration, citing Drucker. Jan Düsterhöft, a German academic now affiliated with the Georg Eckert Institute, provides the publisher’s preface to the Black Letter Press edition shown above. All three identify the two features of Pantographia that echo two other works in the Books On Books Collection: Sam Winston’s One & Everything (2023) and Claire Jeanine Satin’s The Hebrew Alphabet Expressing the Celestial Constellations (2017).

Original at Mansfield College Library, Oxford University

Even in 1799 several of the alphabets displayed by Fry represented extinct languages. Today the Endangered Alphabets Project initiated by Tim Brookes aims rescue languages and their alphabets from that fate. Brookes’ project inspired Sam Winston’s story. More forcibly than Drucker and Dukes, Düsterhöft identifies the imperialist and Western perspective in Fry’s endeavor. Winston’s fable is populated with “story characters”, drawn as various sized and colored blobs, each filled with its distinguishing alphabet. Some are filled with hieroglyphic dogs (presumably for Egyptian shaggy-dog stories), others with Greek, Cherokee and so on. The one story that decides it is the “One and Only story” is filled with the English (Latin or Roman) alphabet and proceeds to eat up all the others.

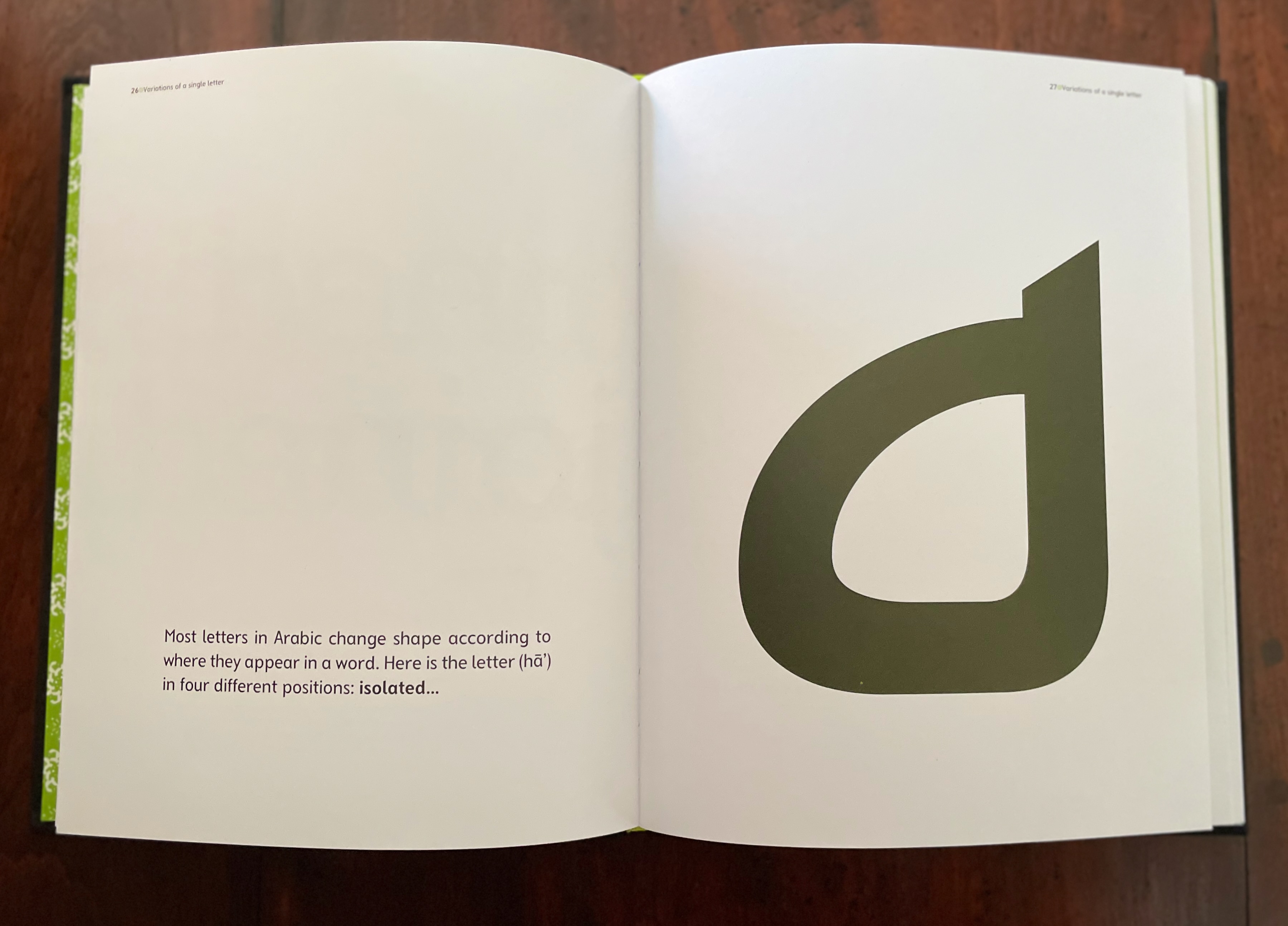

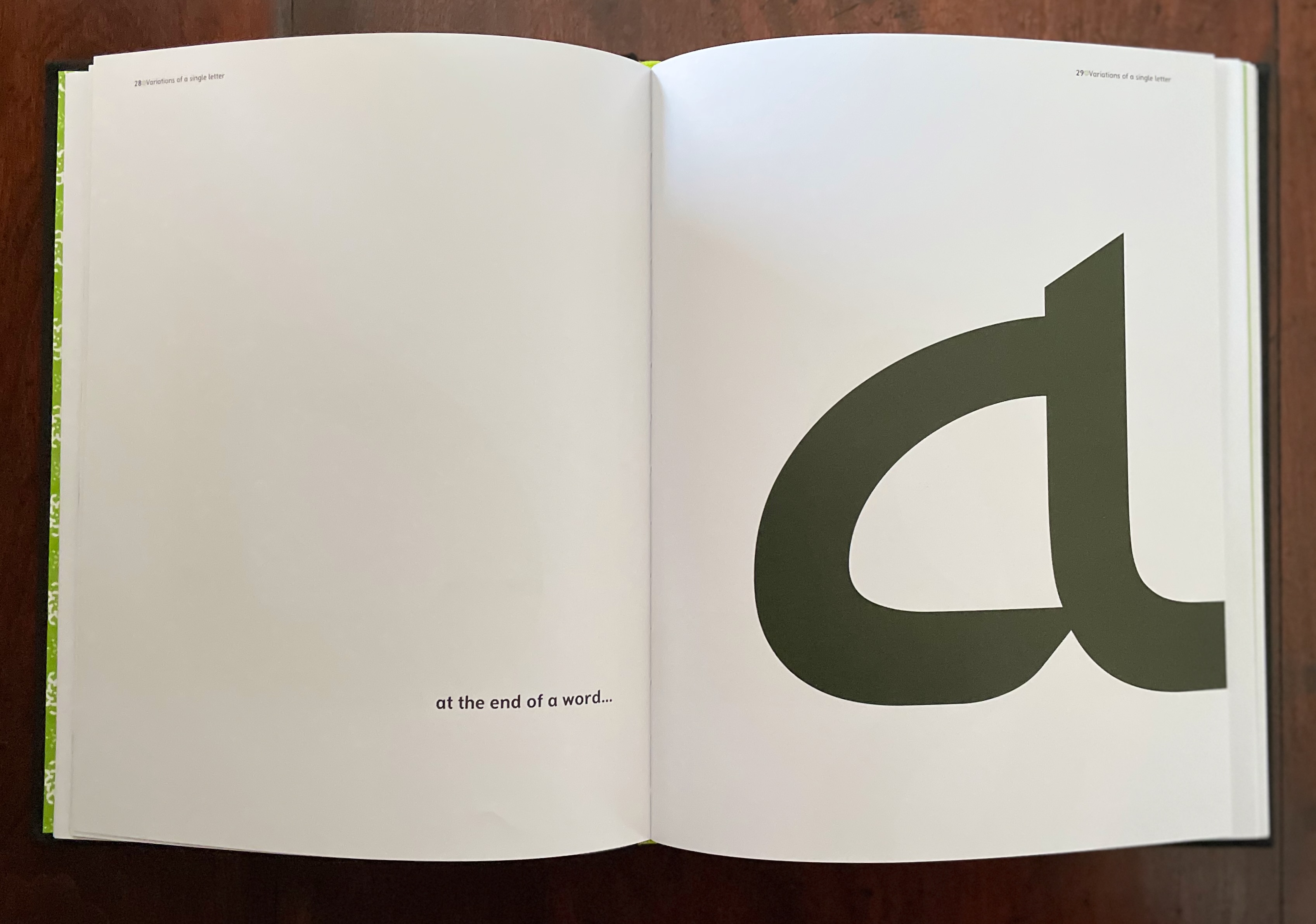

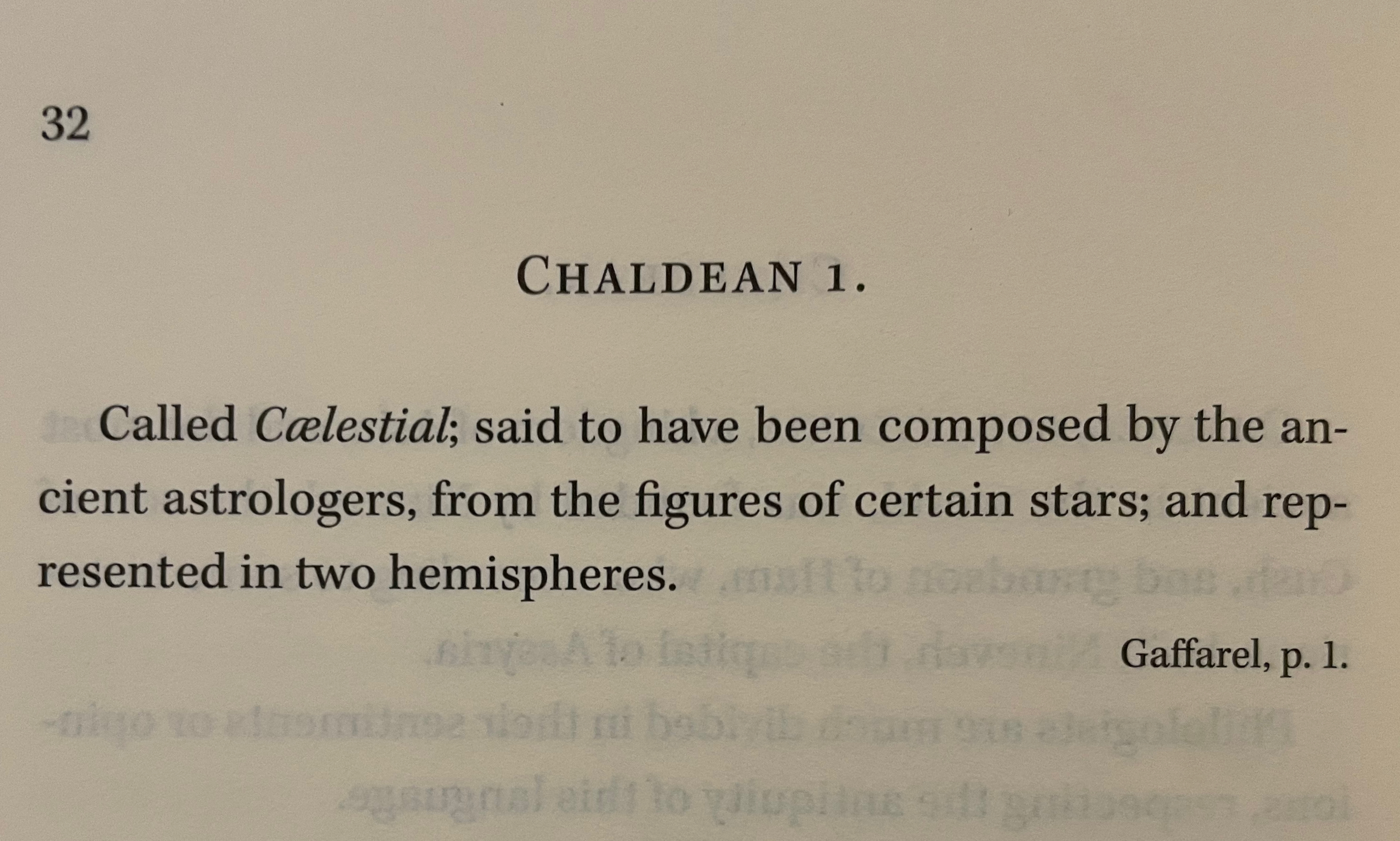

In Pantographia, Chaldean, one of the extinct languages, is a special case, not because Fry includes 20 variant specimens (Greek has 39) but because it is reportedly celestial. The first of Fry’s cited sources for this alphabet is Jacques Gaffarel (1601–1681), a French scholar and astrologer. A bit of digging reveals the source to be more precisely a woodcut from a 1650 translation of Gaffarel’s Curiositez inouyes sur la sculpture talismanique des Persans, horoscope des Patriarches et lecture des estoiles (1629).

From Pantographia (2022)

Unheard-of Curiosities : Concerning the Talismanical Sculpture of the Persians, the Horoscope of the Patriarkes, and the Reading of the Stars (1650)

Jacques Gaffarel

In addition to its astrological character, Gaffarel’s work sits in the traditions of gematria, the Kabbalah and alchemy, which Johanna Drucker has thoroughly explored in Alphabetical Labyrinth (1999) and Inventing the Alphabet (2022). Among the earlier contributors to these traditions is Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa. Like his mentor Johannes Trithemius, Agrippa was a polymath, occultist and theologian as well as physician, legal scholar and soldier. The Latinized Hebrew letters and their corresponding characters in the celestial alphabet seen below come from Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia (1533), which is more legible than Gaffarel’s above.

Henrici Cornelii Agrippae ab Nettesheym à consiliis & archiuis inditiarii sacrae Caesareae maiestatis De occulta philosophia libri tres (1533)

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim

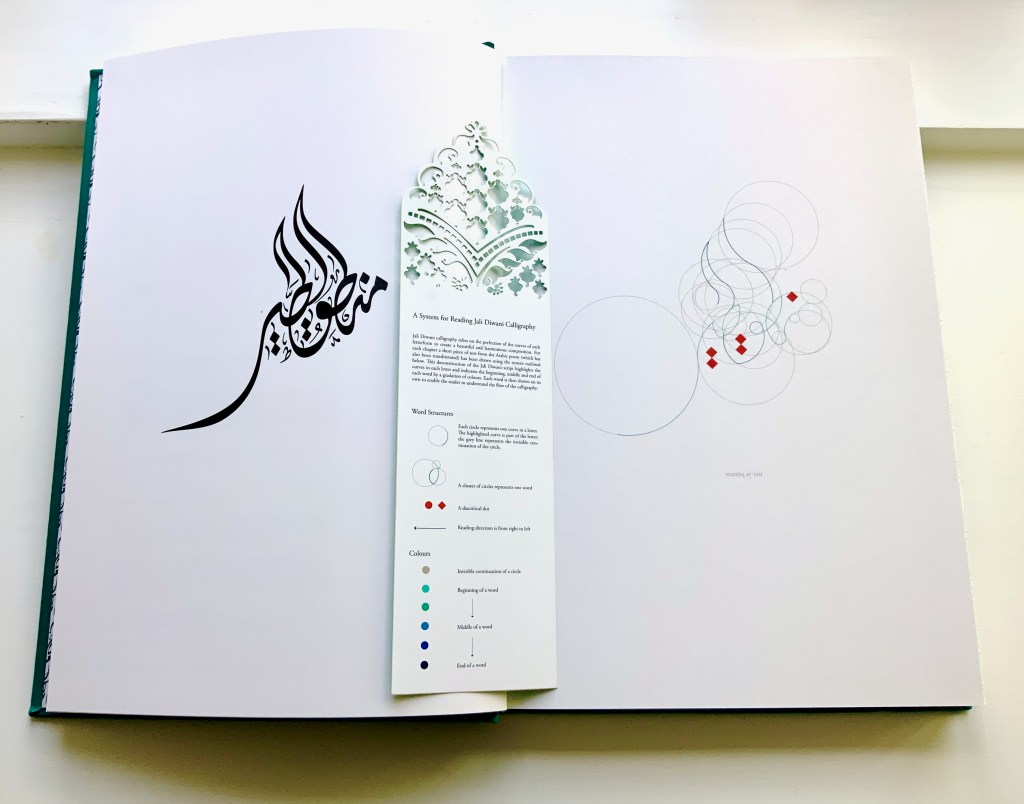

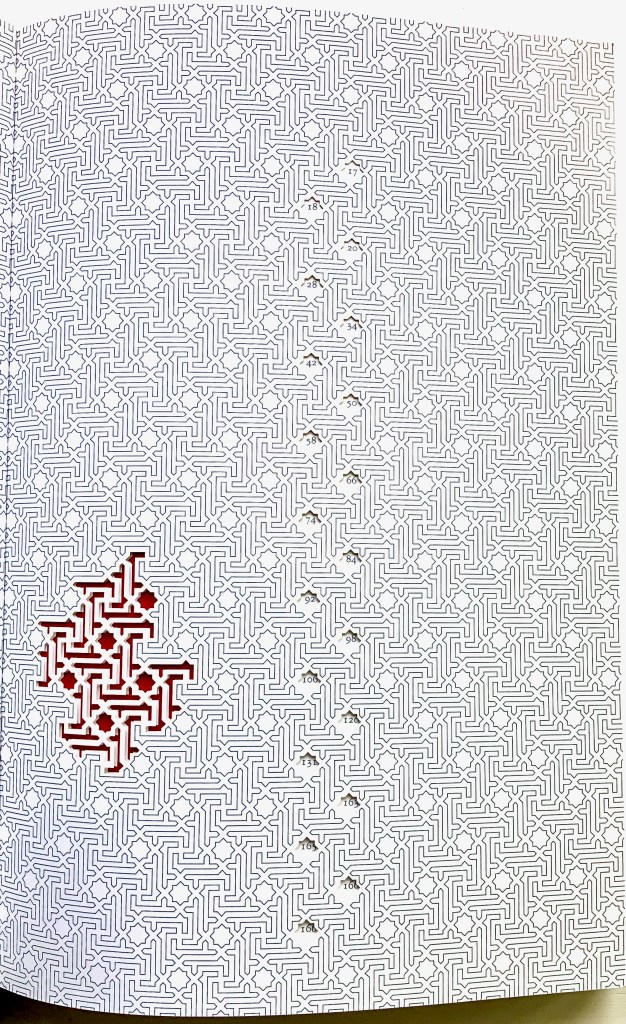

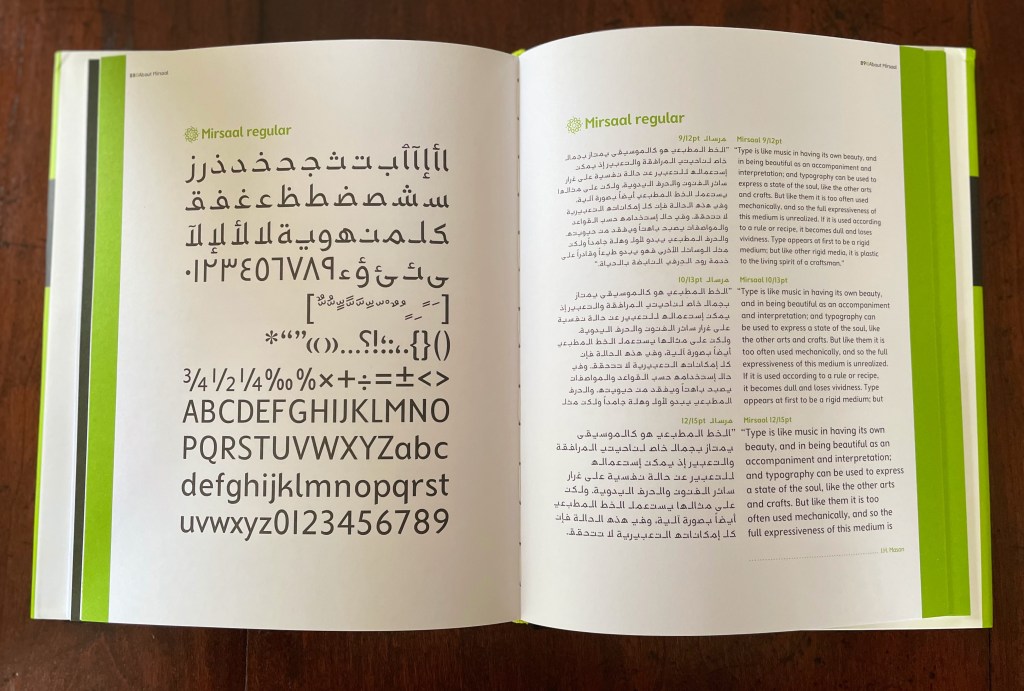

Black Letter Press issued this edition in 2022. As indicated in the caption at the head of this entry, considerable attention to materials was given, including blind debossing and hotfoil printing on the front and spine. The edition is not a photographic facsimile; rather it has been scanned and phototypeset. Scanning in lieu of resetting does not eliminate errors, even if the scan is reviewed carefully. Aside from occurrences of “mod” instead of “most”, “mall” instead of “shall”, and “2ist” instead of “first”, though, the most unusual variation from the original is the deliberate movement of openings on the verso to openings on the recto and, in the specimen section, the reversal of all verso and recto pages. On his verso pages, Fry placed the specimen, and on the recto pages, he placed comments, explanations and sources. For Black Letter Press, the reverse seems to have made more sense. Below are comparisons of pages from the original (left) and the Black Letter Press edition (right).

Left: 1799 original. Right: Black Letter Press facsimile.

Most uncaught scanning errors leap out, so despite the niggling worry about accuracy, the greater legibility and probable accessibility of the 2022 edition is welcome for explorers of alphabets and alphabet-related works. For the Books On Books Collection, its enhancement of the pleasure in Winston’s and Satin’s works and others such as Golnar Adili’s BaaBaa Aab Dad, Islam Aly’s 26 Letters and Ben Shahn’s The Alphabet of Creation (1954), it is more than welcome.

Another 25 images of Fry’s original edition can be found here, courtesy of The Letterform Archive.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

Drucker Johanna. 1999. The Alphabetic Labyrinth : The Letters in History and Imagination. London: Thames & Hudson.

Drucker Johanna. 2022. Inventing the Alphabet : The Origins of Letters from Antiquity to the Present. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Not just another in the long line of histories of the alphabet, rather it explores “Who knew what when about the alphabet?” How did the way they knew it affect how they imagined its identity and origin? For Drucker, Pantographia marks an endpoint and transition. These printed compendia of alphabetic scripts began in 1518 with Johannes Trithemius. Initially spurred by interest in the occult as well as exotic and ancient scripts and a search for the “original” alphabet, compendia gradually became more secular but still eclectic. By 1799, Fry ‘s was an exception by still including the Celestial Alphabet and citing sources in trackable ways. Simultaneously an investment in imagination and a significant step forward for scholarship.

Dukes, Hunter. 10 October 2023. “Pantographia: A Specimen Book of All the Alphabets Known on Earth (1799)“. Public Domain Review. Dukes, editor of the Review, celebrates Pantographia‘s iconic presence in the public domain. In his celebrating, Dukes also notes the presence of the Celestial Alphabet in Pantographia and Drucker’s singling out Fry for taking the antiquarian compendium of alphabets to the earliest stage of specialized, professional research. He also surrounds Fry’s effort with other interesting direct and indirect contexts: the discovery of the Rosetta stone in the same year as Pantographia’s publication and the extinction of several of the languages that Fry’s alphabet represents.

Düsterhöft, Jan. 2022. “Foreword”. In Fry, Edmund. 1799. Pantographia, Containing accurate Copies of all the known Alphabets in the World. Turin, Ialy: Black Letter Press. A German academic now affiliated with the Georg Eckert Institute, Düsterhöft also raises the point about extinction and relates it to the West’s imperial colonial perspective, which Fry displays in his omissions and dismissal of the Chinese mind’s intellectual and rational capacity “as evidenced” by the lack of an alphabet. Düsterhöft also identifies Gaffarel’s source for the celestial alphabet: Guillaume Postel ‘s Linguarum Duodecim Characteribus Differentium Alphabetum Introductio [An Introduction to the Alphabetic Characters of Twelve Different Languages] (1538). Postel (1510 – 1581) was a polyglot French linguist, astronomer, Christian Cabalist, and diplomat.

From Postel, Linguarum