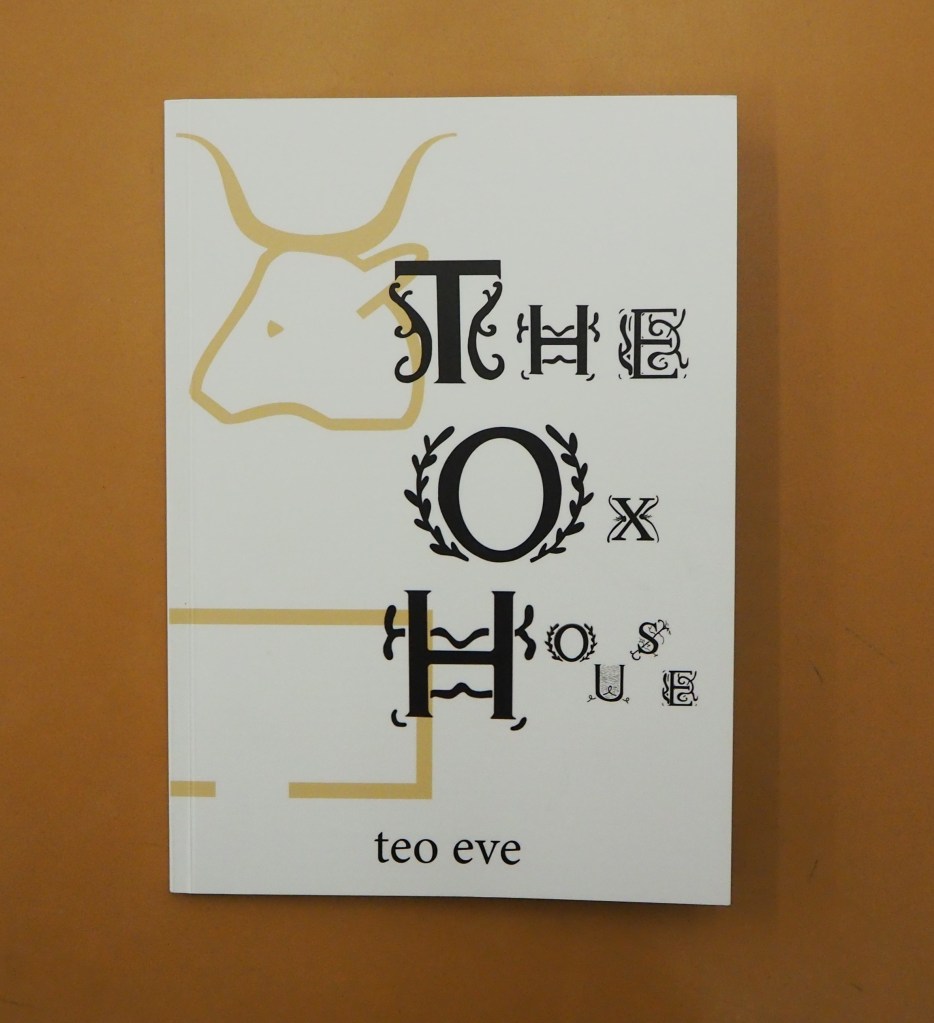

The Ox House (2022)

The Ox House (2022)

Teo Eve

Perfect-bound paperback. H210 x W148 mm. 68 pages. Acquired from Penteract Press, 6 August 2022.

Photos: Emilia Osztafi.* Displayed with permission of the publisher.

A love letter to the letters of the alphabet, Teo Eve’s debut collection The Ox House contains an eclectic array of constraint-based poems, innovative forms, and concrete & visual works. At once homage to the intricate hieroglyphs used in Ancient Egypt & the beautifully illuminated capital forms of Medieval manuscripts, and an exploration into the possibilities of new ways of playing with letters’ shapes & sounds, The Ox House harks back to a time when words were magic, and language was new. — Publisher’s description.

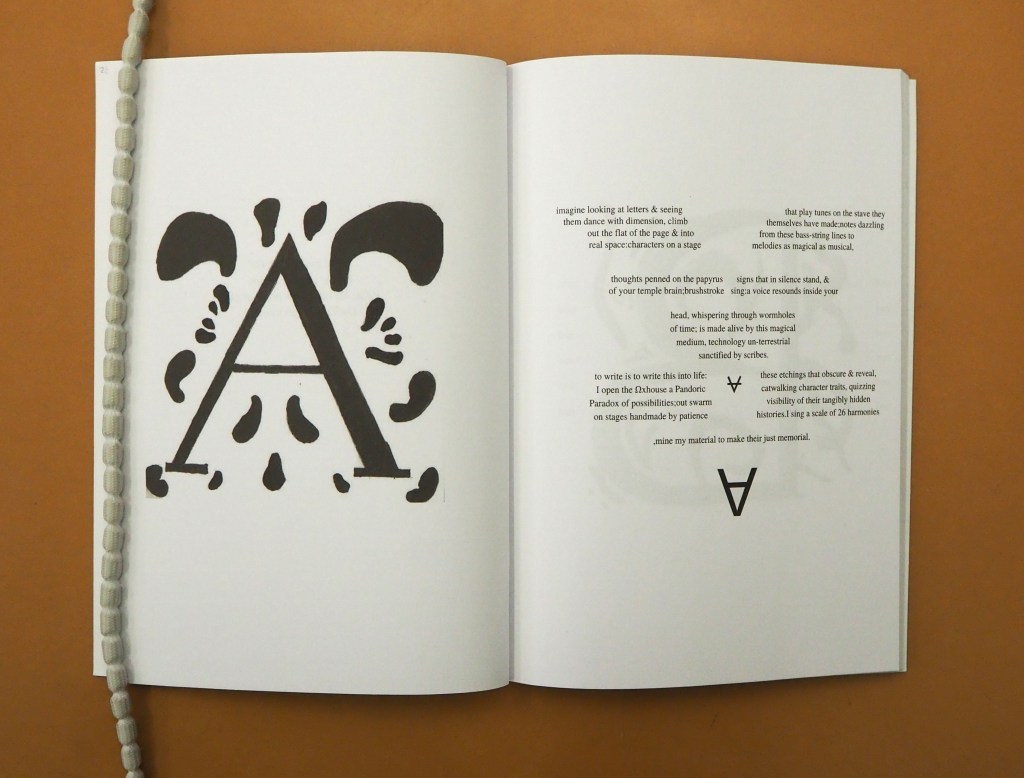

At some point, we all had to learn a set of indecipherable signs, and transform them into meaningful referents. Eve’s work intends to “make letters strange and mysterious again” through 26 poems (one for each letter of the Latin alphabet) paired with visual artworks inspired by medieval illuminated capitals, those elaborately hand-painted letters that marked the beginning of new chapters. For Eve, this “respect for the letterform” has been lost in an age in which the “omnipresence” of characters tends towards “disposability & misuse”. (Eve, 16 May 2022) So, this work gives each letter a personality of its own. The visual poems characterise the characters we usually take for granted.

The “Ox House” of the title derives from the glyphs for the objects whose names began with the sounds of the first two letters of our upper-case alphabet: a shape suggesting an ox head, called aleph or alif, which gradually became our letter A, and a shape suggesting a shelter or house, called beth or bait, which gave us our B. From the moment readers come upon the first poem — a visual poem, shaped like an ox head — they find themselves with the poet as he opens “the Ωxhouse a Pandoric / Paradox of possibilities”, a Pandora’s Box of letterforms, potentially volatile but also generative. As Eve says of the work, it “harks back to a time when words were magic, and language was new”, and this first poem sets the theme and starts the readers out on the book’s alphabetical mythical narrative.

Pandora’s Box is more than a mythical analogy here: it is enacted textually and visually in the B poem. There, the word “box” is printed repeatedly to form a poem in the shape of the Semitic glyph for beth or bait (“shelter” or “house”) and also the shape of a box. But the bottom side has an opening, framed by the word “ox” instead of “box”. It is as though the “ox” opens “Pandora’s Box” – which it does, insofar as the “ox” (A) opens the ABC, opens The Ox House, and opens the box which is this visual poem. Even the book cover’s “all gold” glyphs for A and B pick up the poet’s Pandoric pun in the opening A poem and reflect the ox’s opening of Pandora’s Box or this house of letters we call the “alpha-bet”.

Shaped poems have a substantial history. The seventeenth-century poet and amateur musician George Herbert wrote a series of sacred poems, The Temple, in which many poems have a visual form such as “The Altar”, shaped like an altar, and “Easter Wings”, with text oriented sideways to create the wings. Eve’s poems for F, H, I, J, O, S, X, and Z follow this tradition, forming the shapes of their subjects, that is their respective letters. Visual poems whose shapes enact rather than simply display their subjects count among the more interesting. Zigging and zagging to form its subject character, Eve’s Z poem enacts and displays.

Eve’s poems signify in other ways besides shape. The poem for E is a lipogram, written in words without the letter “e”, paying homage to Georges Perec’s 1969 novel La Disparition [The Void] and, likewise, to the letter itself, underscoring its usual frequency in English and French. The letter Q is honored with a sonnet consisting of 14 questions probing the nature of meaning, writing and words; one of the more orthographic questions seems to be uttered by Q itself: what power have I, dependent on u? Many of the letterform poems also signify by retracing their ancient origins. The H poem is a complex word search, the placement of letters inspired by Egyptian carved tablets. V uses only words believed to have their root in Old Norse. P is written in IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) specifically because the modern letter P derives from the Egyptian hieroglyph for “mouth”.

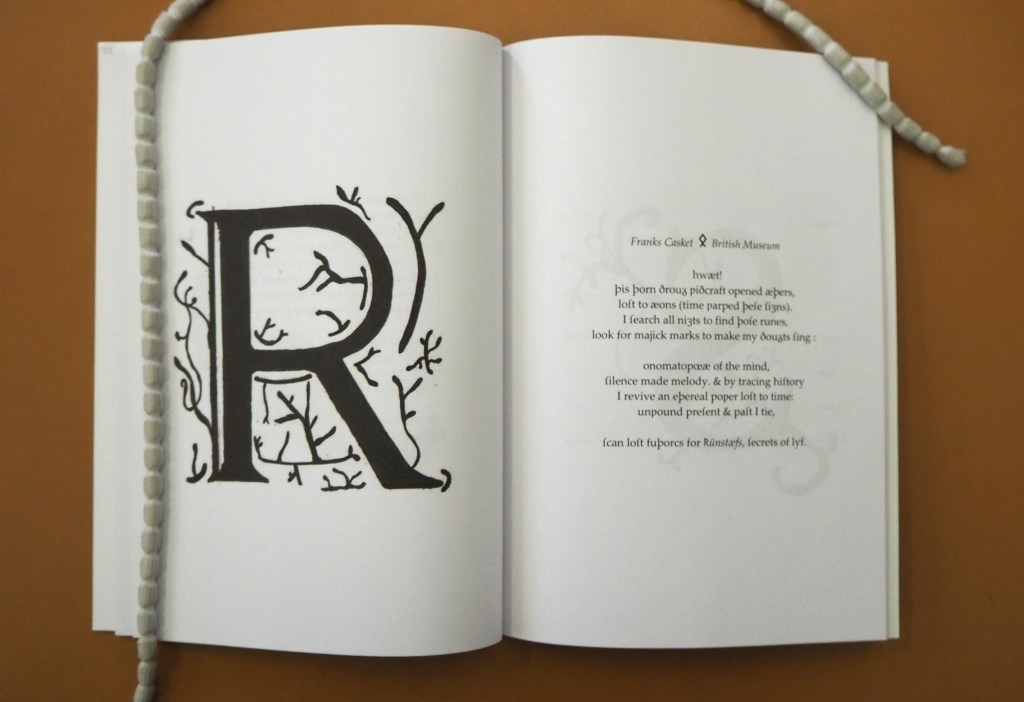

As well as Egyptian hieroglyphs, runes are a recurring orthographic theme, first appearing in the poem for D.

The medieval poem “The Dream of the Rood”, in which the Crucifixion is narrated from the perspective of the cross, survives in the 10th century Vercelli manuscript, but it is also preserved in runic inscriptions on the Ruthwell Cross, 8th century, Scotland.

Detail of the Ruthwell Cross showing the runic inscription from “The Dream of the Rood”. Photo: Connor Motley

Eve uses the opening lines of the Old English poem as the epigraph for his visual poem. Translated into modern English, they read:

Lo, I will tell of the best of dreams

That I dreamed in the middle of the night

After speech-bearers had gone to bed!

[Translation by Osztafi]

Four seemingly incomplete words intersect to form a two-dimensional cross, a simple echo of the pre-modern rood sculpture. At their point of intersection, a stylized form of the Semitic character daleth (meaning “door”), from which our letter D derives, completes the four words — rood, dreams, doors, behind — and in doing so, the Semitic letter becomes a symbol within the Christian symbol. For his intersection, Eve might have used instead the rune ᛞ (daeg [“day”]), but, while daeg also corresponds to our /d/ sound, it has the disadvantage of visually alluding to St. Andrew’s Cross. Although the Old English epigraph contains several other rune-derived letters — æ ð þ ƿ Ȝ — which, unlike daeg, slipped into the Latin alphabet and lingered there for some centuries, we have to wait for the letter R to see how Eve would use runes in a poem.

Here, another medieval artefact is in play: the British Museum’s Franks Casket, an ornate 8th century chest made of whale bone, densely decorated with Anglo-Saxon carvings narrating Roman history, Germanic legend, and other mythology. Unlike the D poem, the R poem is not a visual one. All the visual interest lies in the shapes of those rune-derived Old English letters.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

In the “About” section of his book, Eve explains that earlier versions of his project attempted to illustrate the history of each letter narratively, but then uncertain origins and overlapping histories came cropping in. The Ox House had to learn to let its characters be complex individuals, not neatly categorisable. In fact, arbitrariness – and, sometimes, the accidental meaning of what should be arbitrary — are entirely in keeping with the book’s underlying theme of the possibility of language.

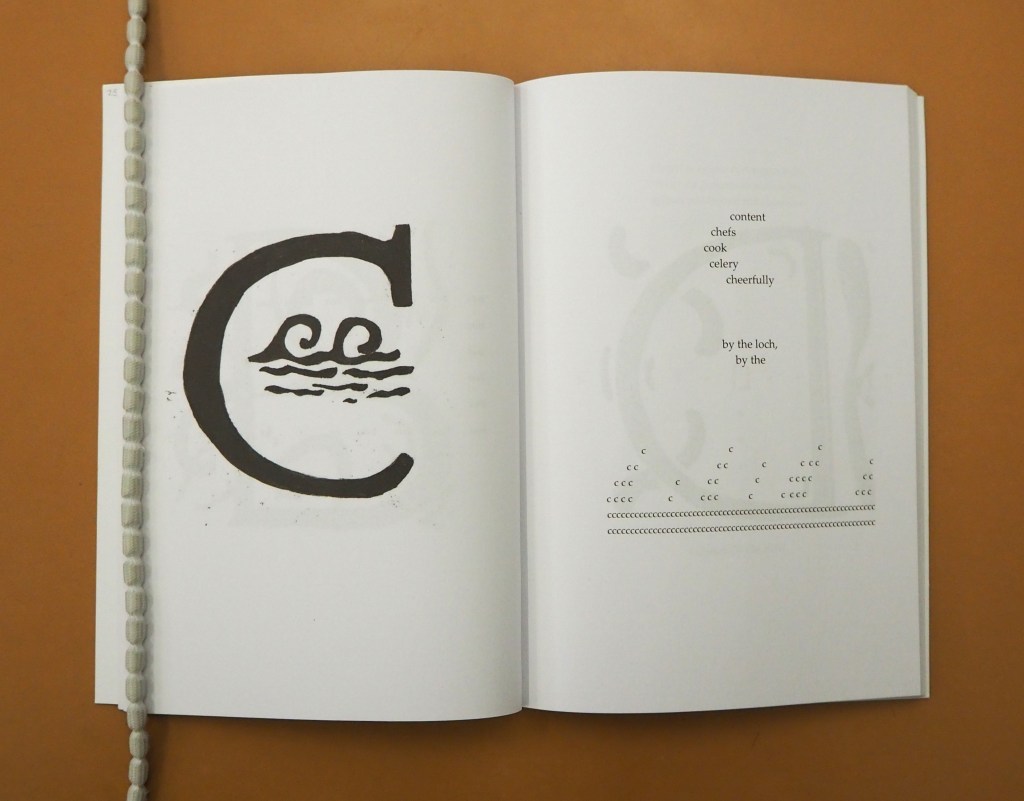

The arbitrariness and oddness of letters’ association with sounds — always a problem for beginning readers — is cleverly addressed in the poem for C. It follows the tradition of children’s alliterative alphabets with “content/ chefs/ cook / celery / cheerfully”. The C-shaped stanza that begins the poem covers the five initial consonant sounds the letter can represent. The middle stanza covers the final consonantal sound it can represent, afloat upon a concluding visual and textual pun made up entirely of the letter itself.

The convergence of image and sound is something letterforms have in common with poems: letters, like poems, are both visual and aural objects. In one sense, individual letters are poems, of the smallest and most self-contained kind. Here, letterforms are exposed as arbitrary shapes that convey sound, but also meaningful artworks with a long history that is far from arbitrary – from the glyphs which characterised each character, to the carefully painted illuminated initials in manuscripts. The Ox House is made up of calligraphy artworks and constrained poems in equal parts, and although the poems are “about” letterforms, this is also a work about poetry. Poems have the capacity to play with language both as shape and as sound, making us strangely aware of the play, and making meaning from it. As Eve’s work shows, this magical quality is in language itself, and in each letter.

*Entry jointly written with Emilia Osztafi.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

“Lyn Davies“. 7 August 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Mark Van Stone“. 31 May 2023. Books On Books Collection.

“The Dream of the Rood“. 10th century. The Old English Aerobics Anthology. Based on Peter Baker’s Introduction to Old English (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2012).

British Library. 2019. Writing: Making Your Mark. Edited by Ewan Clayton. London: British Library.

British Museum. Early 8th century. Franks Casket.

Eve, Teo. 16 May 2022. “When Words Were Magic: Opening The Ox House”. Nottingham City of Literature Blog.

Eve, Teo. 2023. i imagine an image. Shrewsbury: Penteract Press.

Herbert, George. 2004. The Complete English Poems. London: Penguin.

Mclennan, Rob. 30 October 2022. “12 or 20 (second series) questions with Teo Eve“. rob mclennan’s blog.

Pinch, Geraldine. 2004. Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP.

Rosen, Michael. Alphabetical: How Every Letter Tells a Story. London: John Murray.

Shepherd, Margaret. 1985. Learning Calligraphy: A Book of Lettering, Design, and History. London: Thorsons Publishers Ltd.

Terry, Philip (Ed.). 2020. The Penguin Book of Oulipo. London: Penguin.

Wilson, Penelope. 2004. Hieroglyphs: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: OUP.