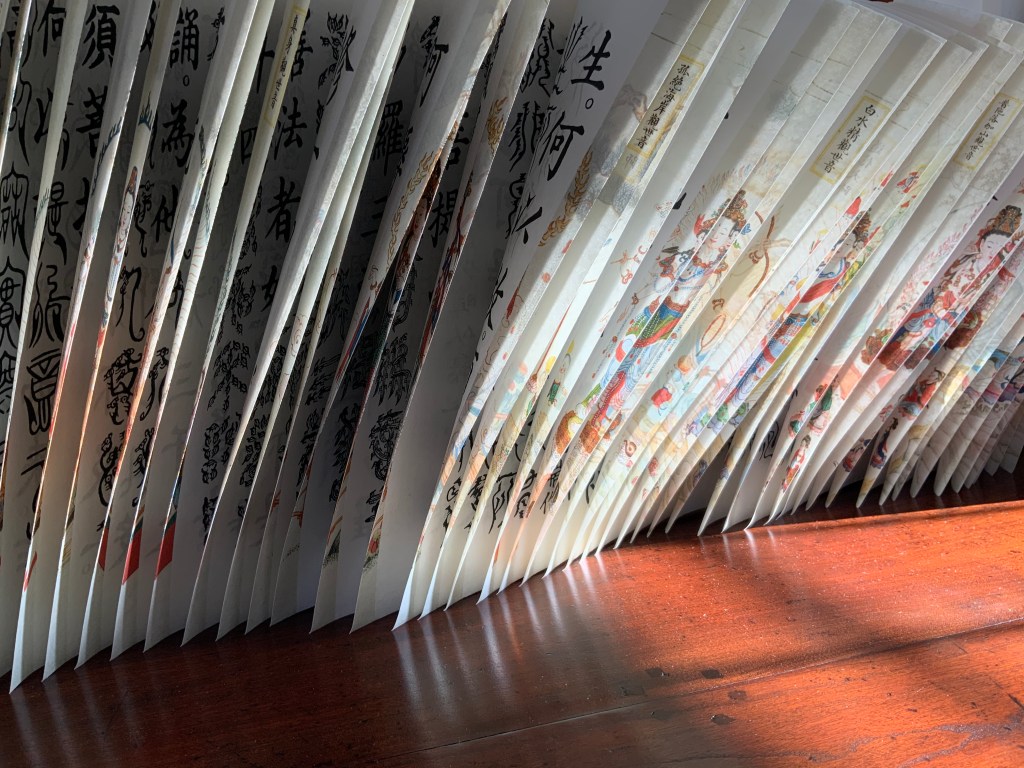

Diamond Sutra in 32 zhuan (seal) fonts (2017)

Zhang Xiaodong

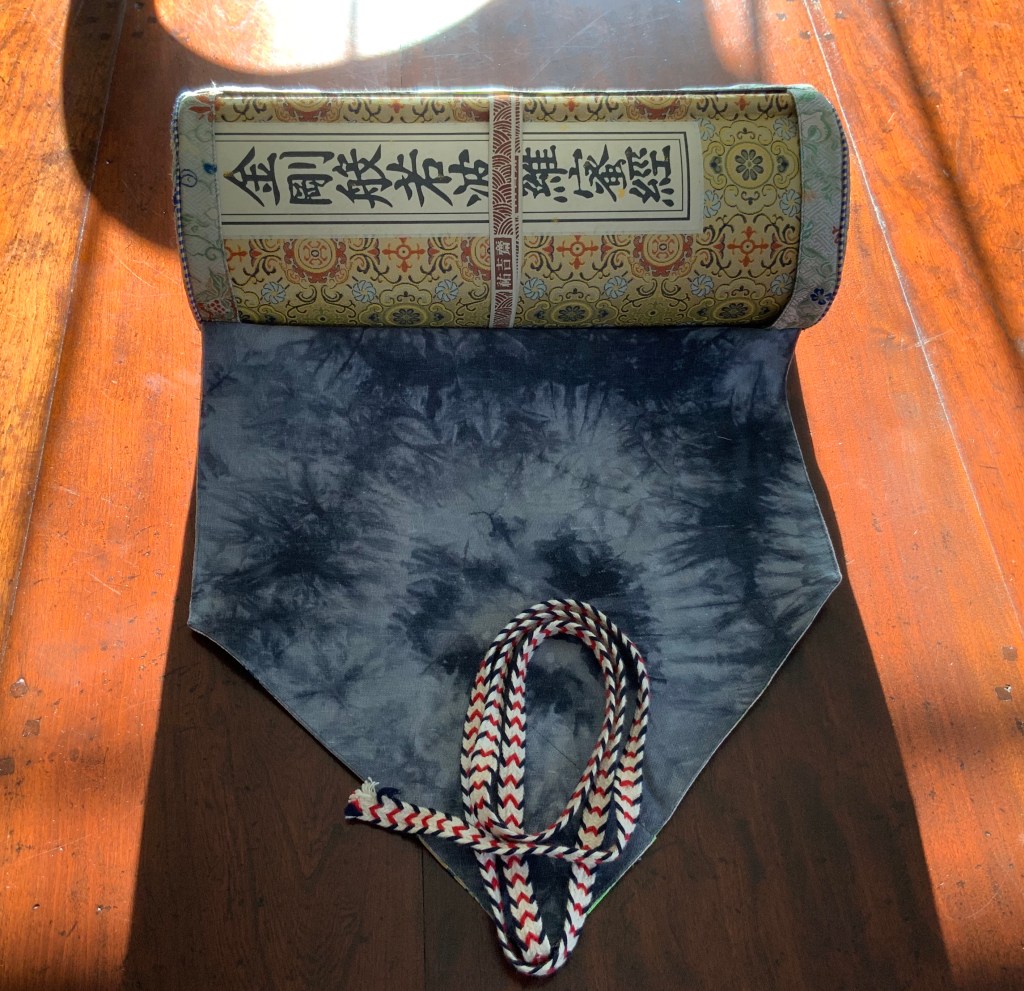

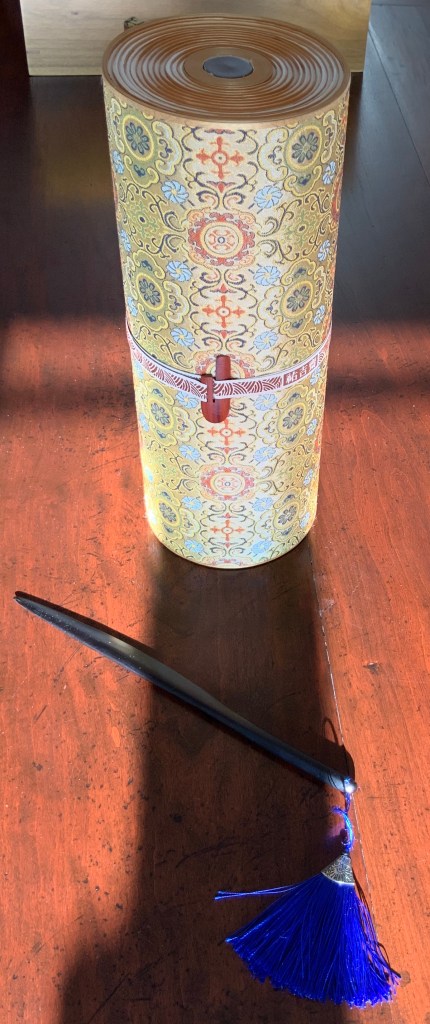

Scroll in dragon scale binding. 152 x 382 x 160 mm. Edition of 300, of which this #197. Acquired from Sin Sin Fine Arts (Hong Kong), 31 October 2019. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

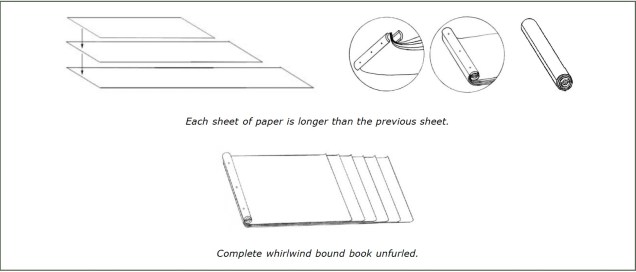

In 1900, in China’s Dunhuang province, the Diamond Sutra (868 CE), the world’s earliest complete and dated printed book, was discovered in a cave along with 40,000 scrolls. One of those other scrolls — Or.8210/S.6349 — was possibly just as important for the book arts as the Diamond Sutra was for the history of printing. Like the Diamond Sutra, Or.8210/S.6349 resides in the British Library and is “the only known example of whirlwind binding in the Stein collection of the British Library” (Chinnery). The structure is also known as dragon scale binding, although distinctions between the two have been debated (Song). It came into use in the late Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) then fell away in the face of the easier to handle butterfly and wrapped-back bindings. Besides Or.8210/S.6349, there are few surviving examples of original whirlwind or dragon scale bindings.

Chinnery, 2007.

One of those few resides in the Forbidden City’s Palace Museum: Wang Ren xu kan miu bu que qie yun [“Wang Renxu’s Correcting Errors and Supplementing the Rhyming Dictionary“] (706).

Dragon Scale Binding of Correcting Errors and Supplementing the Rhyming Dictionary

Five volumes. (Tang dynasty) Compiled by Wang Renxu, annotated by Changsun Nanyan, and edited by Pei Wuzhi. Manuscript written by Wu Cailuan. Height: 25.5 cm, width: 47.8 cm.

From 清宫盛世典籍 = Ancient books and records of Qing dynasty. 2012.National Palace Museum, Beijing.

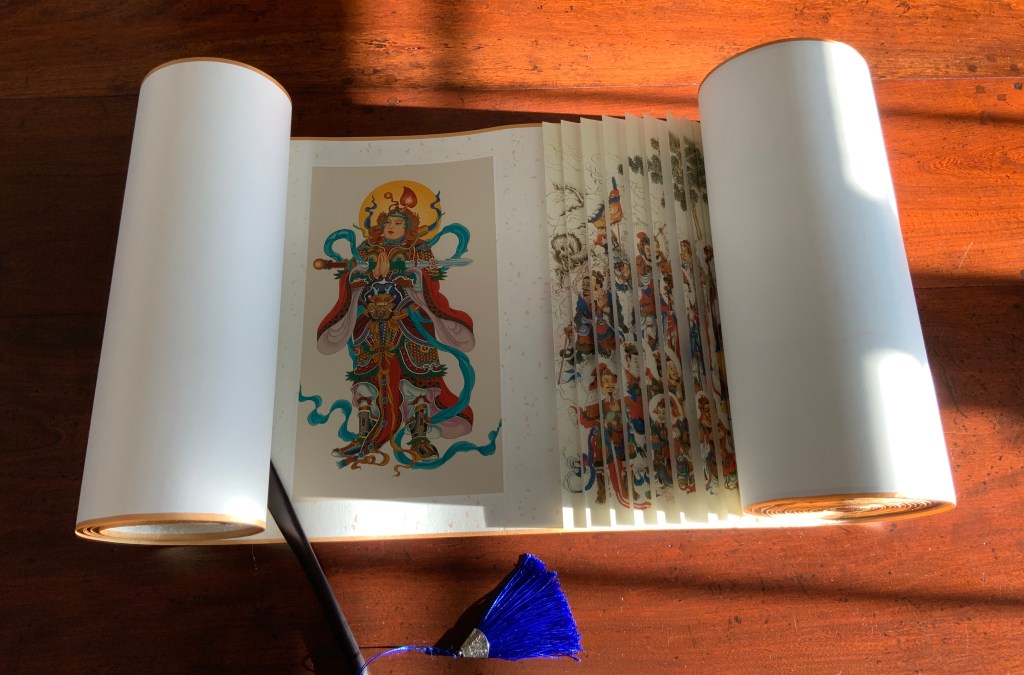

The artist Zhang Xiaodong began studying it in 2008 and in 2010 applied the binding technique to the Diamond Sutra with extensive illustrations. Bringing together these two jewels of inspiration from the Dunhuang cave, Zhang’s effort received the China Printing Awards Gold Award in 2013. An edition of 300 appeared in 2017 and was followed in 2023 by Poem and verses of the Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin (2023) in an accordion variation on the dragon scale form. Zhang carried the technique from the book to wall hangings, and in June 2025, his Good Fortune #2 was shortlisted for the Loewe Foundation Craft Prize and displayed in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

Below, the characters ranged horizontally give the Diamond Sutra‘s full title. The transliteration and translation are “Jin gang bo re bo luo mi jing” = “Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra” = “The Perfection of Wisdom Text that Cuts Like a Thunderbolt” or “The Diamond of Perfect Wisdom Sutra”.

金剛般若波羅蜜經

The silk encasing

Views of the scroll, rolled and bound

The paper used for the book is Shengxuan, a kind of raw rice paper from An Hui province. The inks used to print the Diamond Sutra are Japanese mineral inks; the printing technique, Ultra Giclee on a Japanese printing machine. The page turning wand is made of camphorwood.

Unrolling the scroll

Views of scroll standing

The two sides of the dragon scales

The text consists of 32 passages in which the Buddha converses with Subhuti, an elder monk from the assembly at Shravasti, where the Buddha lived after his enlightenment. A translation into English can be found here.

Top down view

The illustrations are taken from Origins and branches of Dharma by Ding Guan Peng, imperial artist of the Qianlong Emperor (1711-1799), Qing dynasty (1644-1912). Like his application of the dragon scale binding, Zhang’s use of the 18th century painting takes an artistic liberty. The original Diamond Sutra is a simple scroll, and its single illustration, however striking in its detail, does not provide the imagery that the binding demands. Zhang’s melding of the sutra with the binding structure, the mid-Qing dynasty artwork, and 21st century printing technology is sure and deft.

As noted earlier, Zhang has adapted his revival of the dragon scale scroll binding to other structures. In the next work, he applies it in an accordion portfolio to another treasure of Chinese culture.

Poem and verses of the Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin (2023)

Poem and verses of the Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin (2023)

Zhang Xiaodong

Boxed book; Accordion Dragon-scale binding. Box: H547mm L x W330 x D80 mm. Book: H525 x W304 x D39 mm. Edition of 700, of which this is #80. Acquired from Sin Sin Man Atelier, May 2023.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Writing in the same century as Daniel Defoe and Henry Fielding, Cao Xueqin created Dream of the Red Chamber, a complicated multi-volume epic about the decline of the fictional Jia family. It is considered one of the “Four Great Classical Novels” of traditional Chinese literature. According to the modern Chinese scholar Lu Xun, though, Cao Xueqin broke all the rules of traditional fiction. In “A Guide to Reading Story of the Stone/Dream of the Red Chamber “, Bryan Van Norden summarizes the narrative this way:

… when the novel begins, the Jias are immensely wealthy and distinguished, the problem is that, “They are not able to turn out good sons…. The males in the family get more degenerate from one generation to the next” (74). The novel centers on the Rong-guo wing of the family, whose eldest surviving son is Jiǎ Bǎo-yù (贾宝玉), a bright and kind-hearted but unambitious adolescent. Early in the novel, he meets his cousin, Lín Dàiyǔ (林黛玉), who is beautiful and brilliant, but also prim and touchy. The two will fall in love, but in Chapter 1 we learn that Bao-yu is the incarnation of a supernatural stone, while Daiyu is the incarnation of a magical flower, and that the two must learn a lesson through “the tears shed during the whole of a mortal lifetime” (53). The lesson is the danger of “attachment” (even a seemingly good attachment like romantic love). ”

So underlying the narrative, there is considerable allegorical mythology and Taoism.

Zhang has produced a towering eight-volume set incorporating the epic’s later 19th-20th century illustrations by the Qing dynasty artists Sun Wen (1819-1891) and Sun Yunmo (1867-1903).

Courtesy of Sin Sin Fine Arts gallery

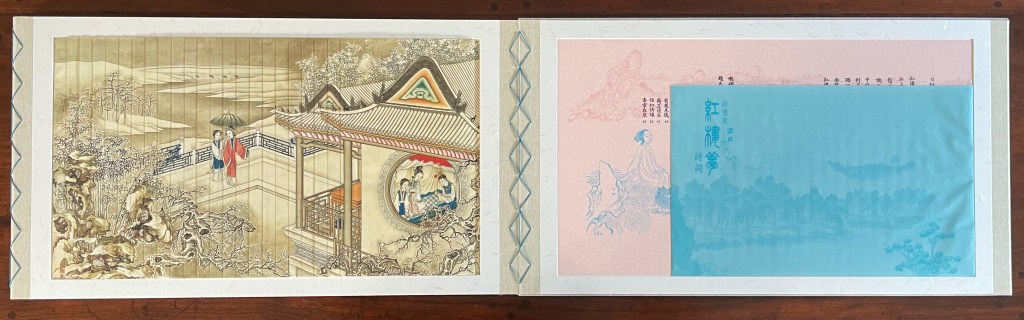

The briefcase-style box presents a volume of extracts: 8 paintings and 77 poems from the text. After the panel presenting the table of contents, there are five panels for the paintings. Using the bifoliated dragon scale technique, three panels are used to display 6 of the paintings and all of the poems; the two panels between the three bifoliated panels display the remaining 2 paintings.

The first panel after the table of contents is a bifoliated dragon scale panel. The 23 bifolios in the panel present the first 2 of this volume’s 8 paintings.

Left: the first scene in the first bifoliated panel. Right: table of contents with protective sheet.

Enlargement of bifoliated left-hand panel’s first scene.

Once all of the bifolios on the left panel have turned to the right, the second scene “hidden” in the panel has been built, as seen below.

The second scene in the left-hand panel revealed by turning all bifolios to the right.

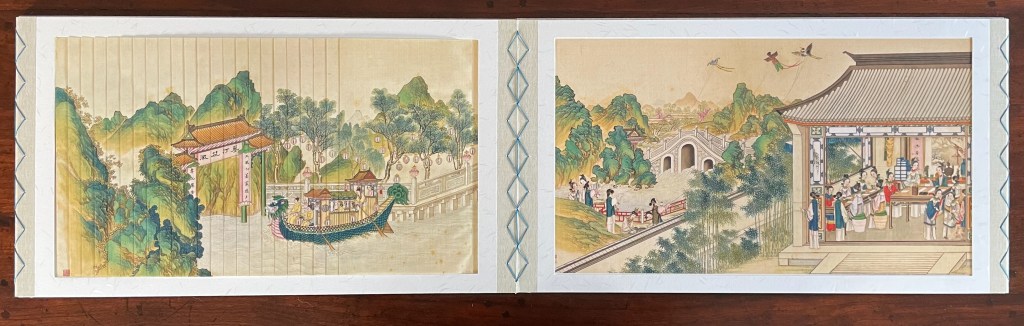

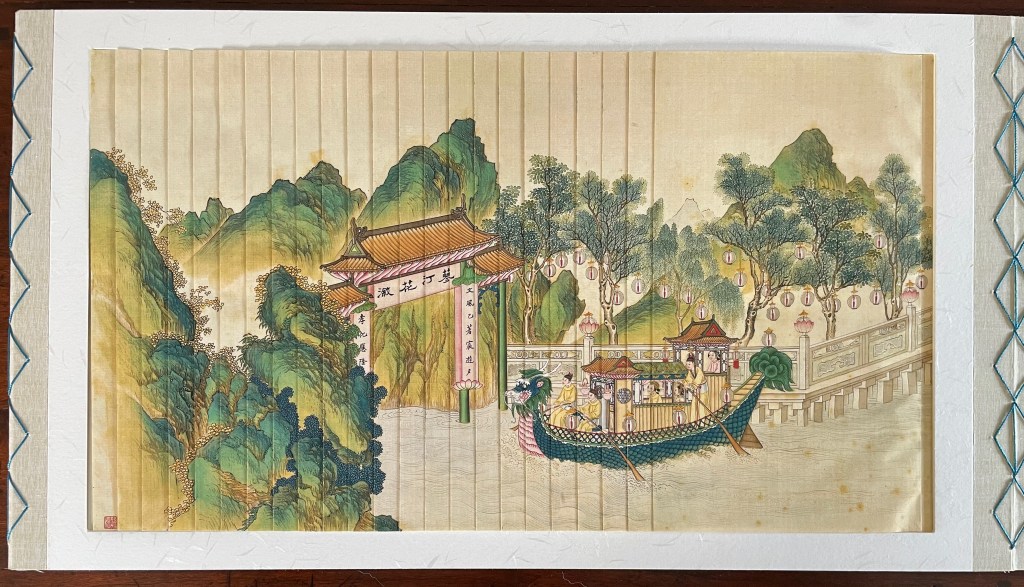

All of the bifoliated panels work in that fashion. The first scene in the second bifoliated panel displays a boat. To single folio panel to its right shows a kite-flying scene.

Left: the second bifoliated panel. Right: the first single folio painting.

Enlargement of the second bifoliated panel’s first scene.

Second scene in the second bifoliated panel revealed by turning the 23 bifolios to the right.

Left: the third and final bifoliated panel. Right: second single folio painting.

Enlargement of the first scene in the third and last bifoliated left panel.

Detail from single folio painting.

Enlargement of the second scene in the third and last bifoliated panel.

The 77 poems appear as the individual bifolios turn. Below, seven bifolios in the third and last bifoliated panel have been turned to the right. Note how the second scene in the panel begins to build on the right.

In the right-hand margin, the label reads, “Chapter 51: Xue Xiaomei’s New Nostalgic Poems; Doctor Hu Misuses Tiger and Wolf Medicine”, and the poem in the main column on the right is “Nostalgia for Ancient Zhongshan”.

Fame and fortune have never been yours,

yet you were summoned from that world for no reason.

Implicated by this, it is difficult to break free,

so don’t blame others for their constant mockery.

(From www.redmansions.net and www.gushiwen.net. Google-translated).

The Red Mansions site provides a gloss that this alludes to a satirical tale about a falsely aloof country noble named Zhou Yong from Zhongshan, who, summoned to service by the emperor, pretended nostalgia for his seclusion and scorn of fame and fortune. Even the “Redologists” at the Red Mansions site demur on explaining the relationship of the poem to the characters and narrative of Dream of the Red Chamber.

At the top of the main columns are hǎitáng flowers, which come from different genera (crabapple, quince, begonia, and others). When written 苦恋, hǎitáng connotes “unrequited love”, which fits some of the epic’s narrative, but the addition of this “florilegium” is Zhang’s addition. If the Chinese characters beside the flower are, in fact, 兰在幽林亦自芳 , they come from the Tang dynasty poet Liu Yuxi (772-842 CE), obviously predating the Dream of the Red Chamber. One translation would be “Even in secluded woods, orchids retain their fragrance”. The allegory or metaphor seems to be that “even when alone, one should maintain a noble character“, which does align with the moral issues of some in the Jia family.

Closer view of the flower on the seventh folio. Closer view of the new image building on the right.

It may also be that Zhang’s pairing of the secluded orchid with the allusion to the isolated Zhou Yong is meant as an echo, but what relation they have to the scenes on either side of the dragon scale panel is unclear. Perhaps we simply have a beautiful cultural mélange: an assemblage of extracts from an 18th century classic of Chinese literature, a reproduction of its famous illustration by two 19th-20th century Chinese artists, a Chinese hǎitáng florilegium, and Zhang’s 21st century revival of the 1000-year-old Chinese bookbinding structure.

Although Zhang Xiaodong is acclaimed for resurrecting the dragon scale binding in 2010, Mark Tomlinson taught a workshop on it in 2000 at Daniel Kelm’s and Greta Sibley’s Garage Annex School in Easthampton, MA. Pati Scobey’s Evening Susurrus (2006) eventually emerged from it.

Evening Susurrus (2006)

Pati Scobey

Scroll format, 30 cm x 15 cm at longest extension. Relief printing on Kitakata and linen book cloth, sewn onto bamboo ‘spine’.

British Library.

A year before, Rutherford Witthus produced Skip for Joy (2005), which was also inspired by the whirlwind structure.

Skip for Joy (2021)

Rutherford Witthus

Dragon-scale scroll bound to bamboo rod. H306 x W477 mm, 11 panels. Edition of 5, of which this is #1. Acquired from the artist, 18 August 2021.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of the artist.

Later works include Helen Malone’s Tsunami (2011) and Steven Daiber’s El que vive de ilusiones muere de desengaño (“He who lives with illusions dies of disenchantment”) (2015). The same year, Jim Escalante taught a course on the technique at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which led to The Song that Never Ends, a striking work by Cynthia Tidler.

Tsunami (2011)

Helen Malone

Box containing “whirlwind” book of Japanese paper washed with sumi ink and water, Japanese stab binding, leather roll. H230 mm, variable width. Unique edition. Acquired from the artist, 2 July 2020.

Photo: Books On Books Collection.

More recent variants on dragon scale binding include Nif Hodgson’s Fluid Horizons (2021) and Camden Richards & Deborah Sibony’s Water, Calling (2021). The most prolific producer of dragon scale bound works, however, is Barbara Hocker. Watercourse I (2022) is but one of several of her works using the technique. Like Zhang, she has applied it to installations.

Fluid Horizons (2021)

Nif Hodgson

Slipcase. Modified dragon-scale concertina. Slipcase: H91 x W158 mm. Book: H90 x W156 mm, 20 panels. Variable edition of 10, of which this is #1. Acquired from 23 Sandy Gallery, 2 September 2021.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artist’s permission.

Water, Calling (2021)

Camden Richards & Deborah Sibony

Felt-covered, modified dragon-scale bound artists’ book, accompanied by audio equipment in custom box. Box: 262 x 262 x D170 mm. Book: H155 x W775 mm (closed). 110 pages. Edition of 15, of which this is #1. Acquired from the artists, 5 October 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artists’ permission.

Watercourse I (2022)

Barbara Hocker

Scroll in dragon scale binding. Unique. Acquired from the artist, 10 February 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Zhang, however, remains the only artist to have applied dragon scale binding to an epic work of literature. By joining the cultural treasure of this binding technique with the Diamond Sutra and then with the cultural treasures of Cao Xueqin, Sun Wen, and Sun Yunmo, he has set a high bar for other book artists.

*An earlier version of this entry appeared 1 December 2019. This version has been updated to include Poem and Verses of Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin, further reading, and Western examples. Also, many thanks to Mamtimyn Sunuoudolu (Bodleian Libraries) for his linguistic assistance and cultural insights. Any errors rest with me.

Further Reading and Viewing

“Barbara Hocker“. 5 August 2025. Books On Books Collection.

“Nif Hodgson“. 28 October 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Helen Malone“. 23 July 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Camden Richards & Deborah Sibony“. 14 February 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Rutherford Witthus“. 28 October 2021. Books On Books Collection.

BPG East Asian Book Formats. 2023. Book and Paper Group Wiki. American Institute for Conservation (AIC). Accessed June 13, 2023.

Brokaw, Cynthia and Kornicki, Peter. 2013. The History of the Book in East Asia. Farnham: Ashgate.

Burkus-Chasson, Anne. 2005. “Visual Hermeneutics and the Act of Turning the Leaf” in Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China, ed. Cynthia Brokaw. Berkeley: University of California, 2005. Also in Brokaw and Kornicki, 2013.

Chinnery, Colin. 7 February 2007. “Whirlwind binding (xuanfeng zhuang)”, International Dunhuang Project, British Library. Accessed 12 December 2019.

Chung Tai Translation Committee. January 2009. The Diamond of Perfect Wisdom Sutra . Accessed 28 November 2019. The full text in English alongside the Chinese characters.

Drège, Jean-Pierre. 1984. “Les Accordéons de Dunhuang”, pp. 195-98, in Soymié, Michel; et al. Contributions Aux Études De Touen-Houang. Volume III. Paris: Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient : Dépositaire A.-Maisonneuve.

Galambos, Imre. 2024. “The Survival of Old Book Forms on the Periphery: Chinese Book Forms in Dunhuang and Beyond”. In Multicivilizational Exchanges in the Making of Modern Science, ed. Galambos, Imre; Mei, Jianjun; Lau, Raymond W. K ; Bala, Arun. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2024. 251–270. Web.

Hotson, Howard. May 2018. “The world’s earliest dated printed book: The Diamond Sutra, 868 CE“. Cabinet. Oxford. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Ko, Stella. 3 April 2018. “Resurrecting the art of China’s dragon scale bookbinding”, CNN Definitive Design. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Lu, Feiran. 12 March 2022. “Artist resurrects a lost art of book binding in painstaking detail“. ShanghaiDaily.com. Shanghai. Accessed 24 July 2025.

Martinique Edward. 1983. Chinese Traditional Bookbinding : A Study of Its Evolution and Techniques. San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center.

MOT Times Editorial Department. 24 February 2014. “Taipei’s ‘2016 World Design Capital’ promotional work wins dual German iF Design Awards, demonstrating the power of local culture and innovation.” MOT Times. Taiwan.

Ren, Yutian, and Anna Dubrivna. 2024. “Traditional Chinese Bookbinding Forms and Their Influence on Modern Book Design“. Art and Design. 2(26). 73–79.

Song, Minah. March 2009. “The history and characteristics of traditional Korean books and bookbinding”, Journal of the Institute of Conservation, 32(1). 53-78. Accessed 12 December 2019. DOI: 10.1080/19455220802630743

Taipei City Government. 2015. “Dragon Scale Binding: The Rebirth of an Ancient Bookbinding Technique“. Taipei, Taiwan. Accessed 23 July 2025.

Tsui, Enid. 2 April 2018. “Art Basel in Hong Kong: city’s small galleries shine through with memorable displays“, South China Morning Post. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Van Norden, Bryan. 2013. “A Guide to Reading Story of the Stone/Dream of the Red Chamber ” (based on the translation by David Hawkes [Penguin Books, 1973]). New York: Vassar College.

Xianfeng Hu, Yang Wang, and Qiang Wu. nd. “Multiple Authors Detection: A Quantitative Analysis of

Dream of the Red Chamber“. Michigan State University.

Xing, Wen. “Bringing the past into the future“, China Daily, 10 January 2019. Accessed 15 November 2019.

Yang, Hu ( 肖阳) and Xiao, Yang.2010. Chinese publishing : homeland of printing. Beijing : China Intercontinental Press.

Yunming, Jia. 3 November 2023. “Dragon Scale Binding: The revival of an ancient Chinese book format“. Garland Magazine. Australia.

Zhang, Wenbin. 2000. Dunhuang. A Centennial Commemoration of the Discovery of the Cave Library. Beijing: Dunhuang Research Institute, Morning Glory Publishers.

Zhizhong, L., & Wood, F. 1989. “Problems in the History of Chinese Bindings“. The British Library Journal, 15(1), 104–119.

One thought on “Books On Books Collection – Zhang Xiaodong*”