In this ode to the letter X, Mexico and language itself, Alberto Blanco and Nacho Gallardo Larrea brilliantly show how the artist’s book can translate word and image from one to the other and back and, at the same time, soar over the challenge of translating poetry.

Book of X (2012)

Book of Equis (2012)

© Alberto Blanco and Nacho Gallardo Larrea (“El Nacho”).

Slipcase paper-covered spine and edges, and leather Intagrafía insignia on cover panel; enclosing a casebound hardback, monotype over boards, and black doublures. H15 x W7.5 in. [18] pages. Letterpress printed with Bembo Roman and Bembo Roman Italic types. Printed on Rives BFK paper. Bilingual text of Spanish and English. Edition of 50 plus 15 artists’ proofs (P.A. 1-15), of which this is #11; 5 binding workshop copies (P.T. 1-5); and 3 print proofs (P.I. 1-3).

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Alberto Blanco.

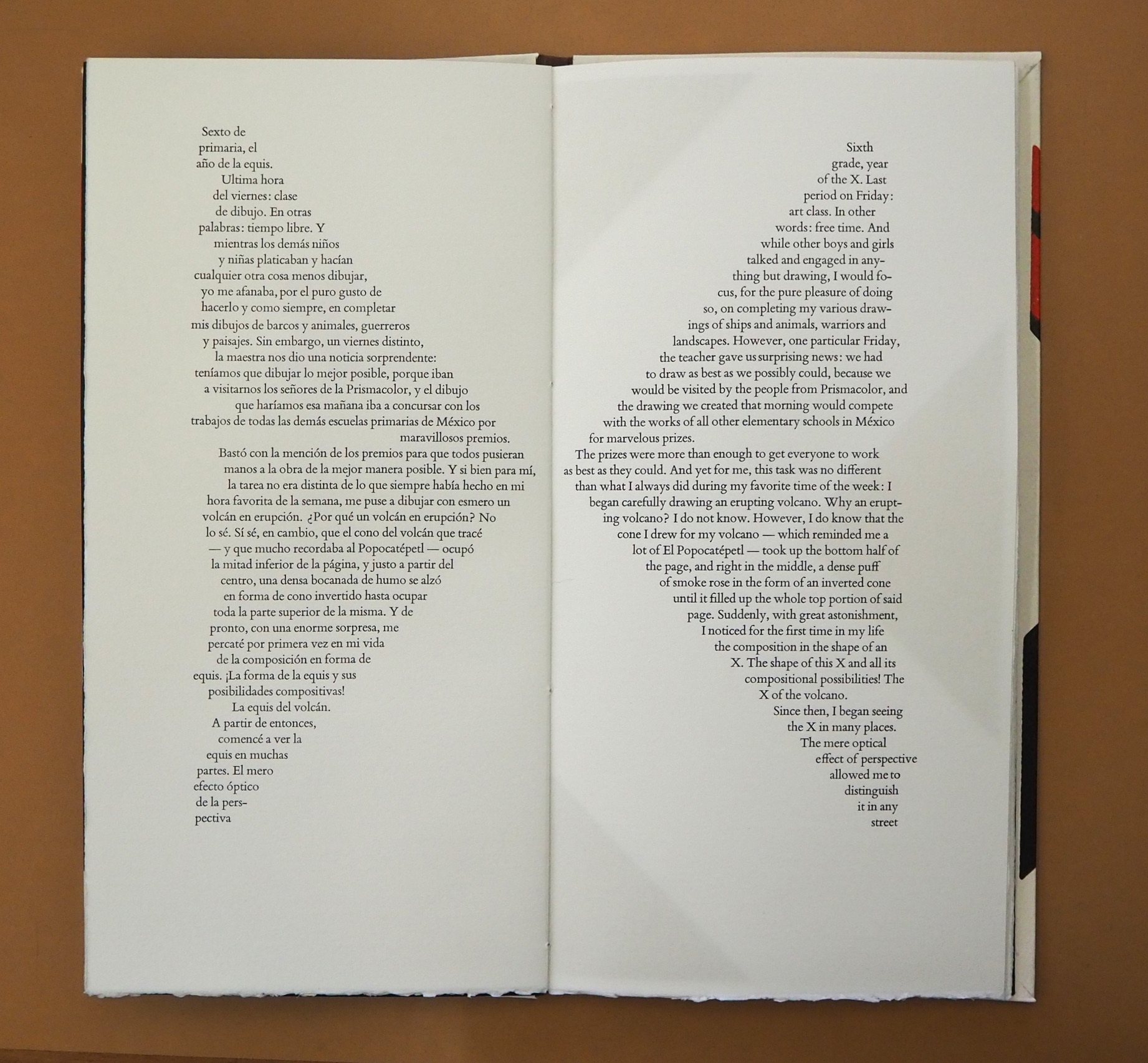

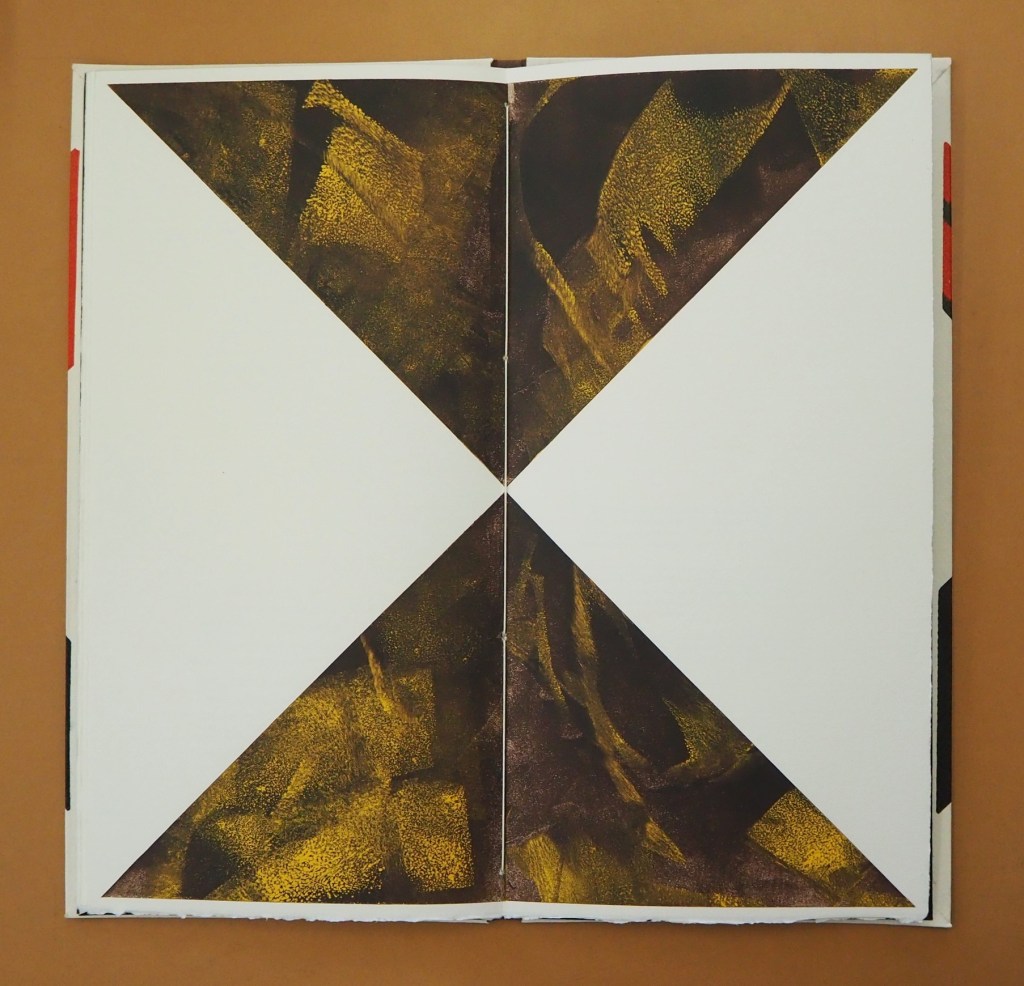

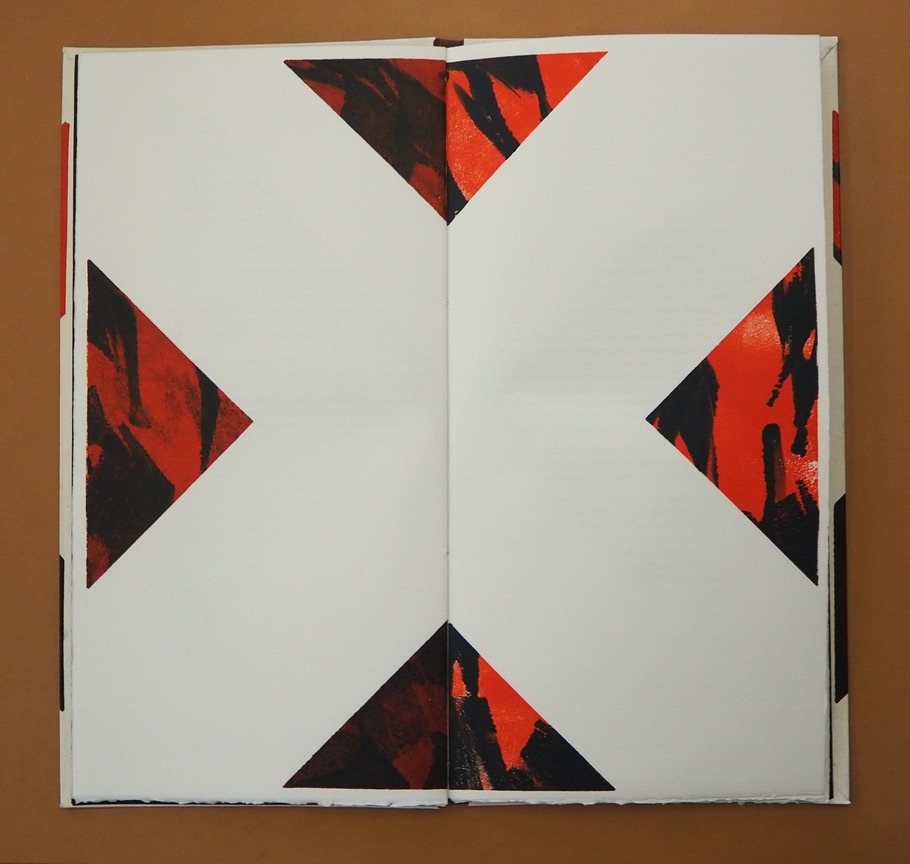

The Spanish and English versions of Blanco’s text shape, and are shaped by, the bilateral symmetry of the letter X and the codex form of the book. Spanish on the left, English on the right: the imposition of type and the ghostly images of the X play with one another. The two texts delight in the crossover between similarity and difference, knowingly in the white space at the exact center of the X in the double-page spread below. How better to use the notion that, for all letterforms, space counts as much as line?

Sometimes the language on one side completes a thought or expression before the language on the other side can do so, a natural phenomenon in translation in which one language needs fewer or more words than the other. See above, for example, the passages beginning “La equis del volcán” and “X of the volcano” that do not quite align in the legs of the X. The Spanish sentence trails off in a fragment to be completed on the following verso page, but the English sentence is already half way there on the recto page above.

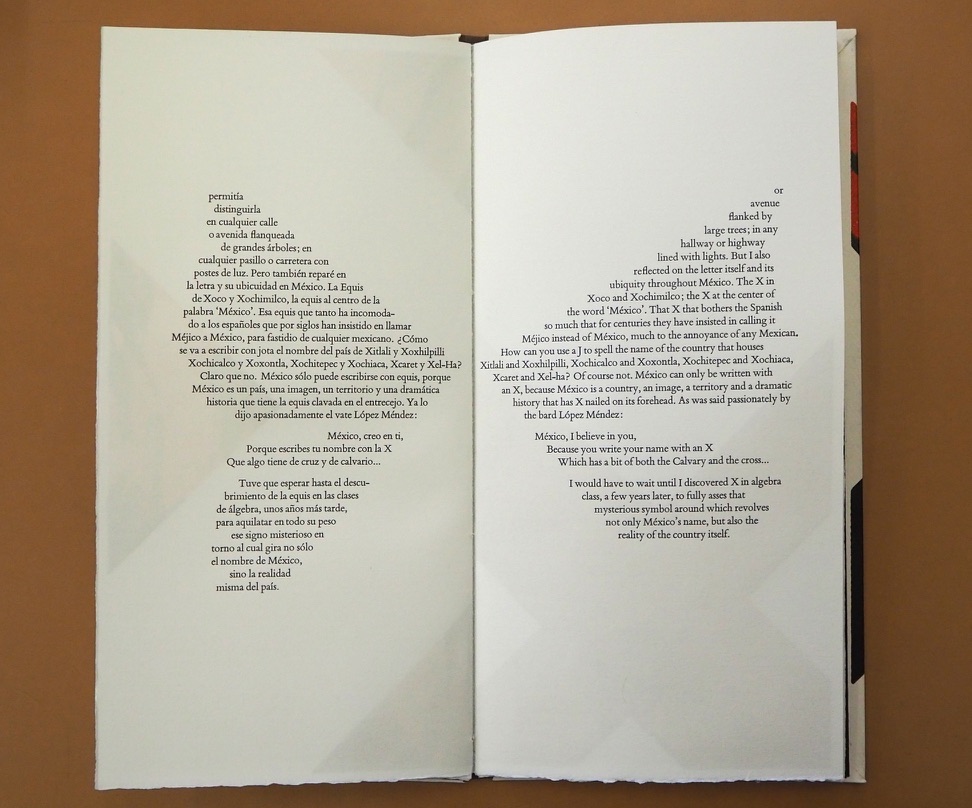

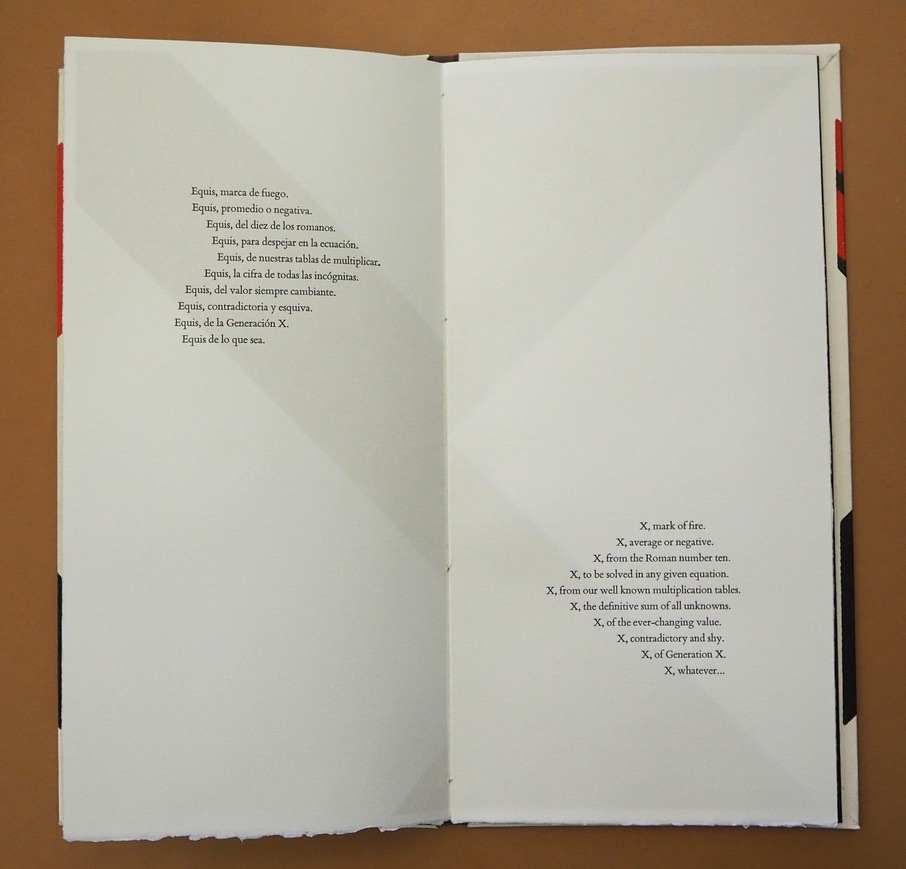

As the shaped poem continues in the pages below, and the number of words in one language exceeds those on the other creating lines asymmetrical to one another, the poet and artist use the X shape in whole and parts and the diametrical placement of text in the last double-page spread to reflect the crossing dance of similarity and difference, asymmetry and symmetry, that they find in X across languages, generations and country.

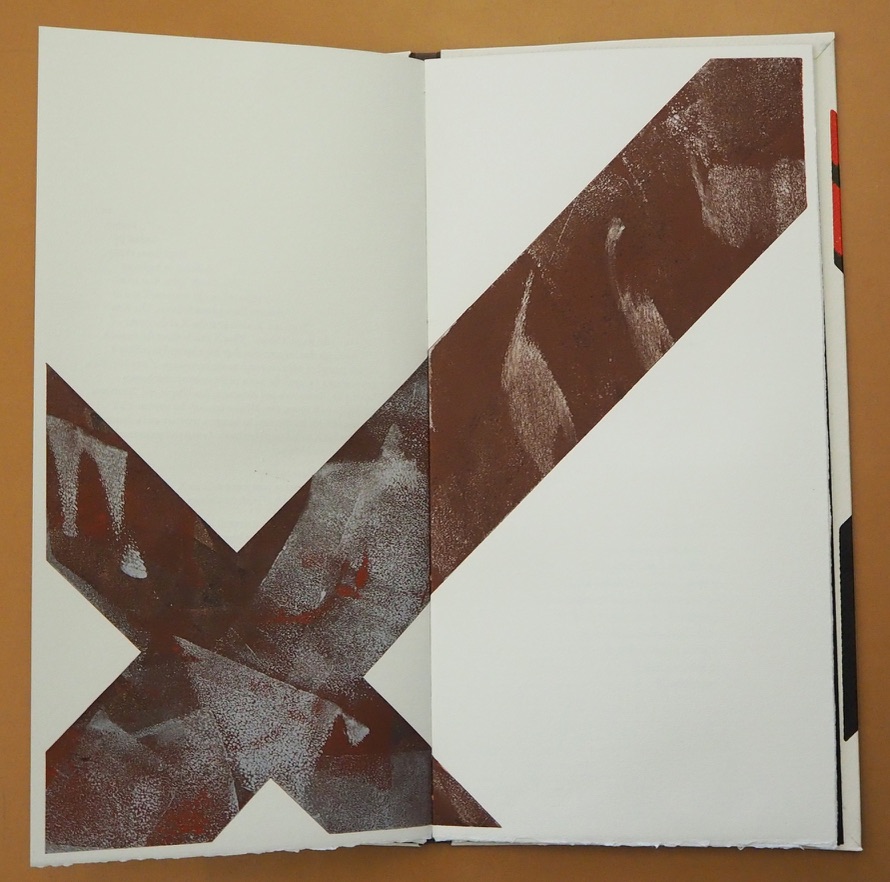

Interpersed between the pages of text, the late El Nacho’s monotypes make color, shape and space play with one another to mirror — not merely illustrate — the thrust of the language. If ever there were a collaborative work that distinguishes the artist’s book from a livre d’artiste, this is it. Alberto Blanco has also created solo artist’s books, which enjoyed an exhibition at the Athenaeum Music & Arts Library, La Jolla, California, February 19-March 26, 2011. Stylistically they are distinct from The Book of Equis, which underscores its collaborative originality.

Colophon: “The Book of Equis was designed and printed in Intagrafía, located in San Jose del Cabo under the direction of Peter Rutledge Koch, with monotypes created by El Nacho. Printed under the supervision of Lenin Andujo Fajardo by Ivonne Rivas.”

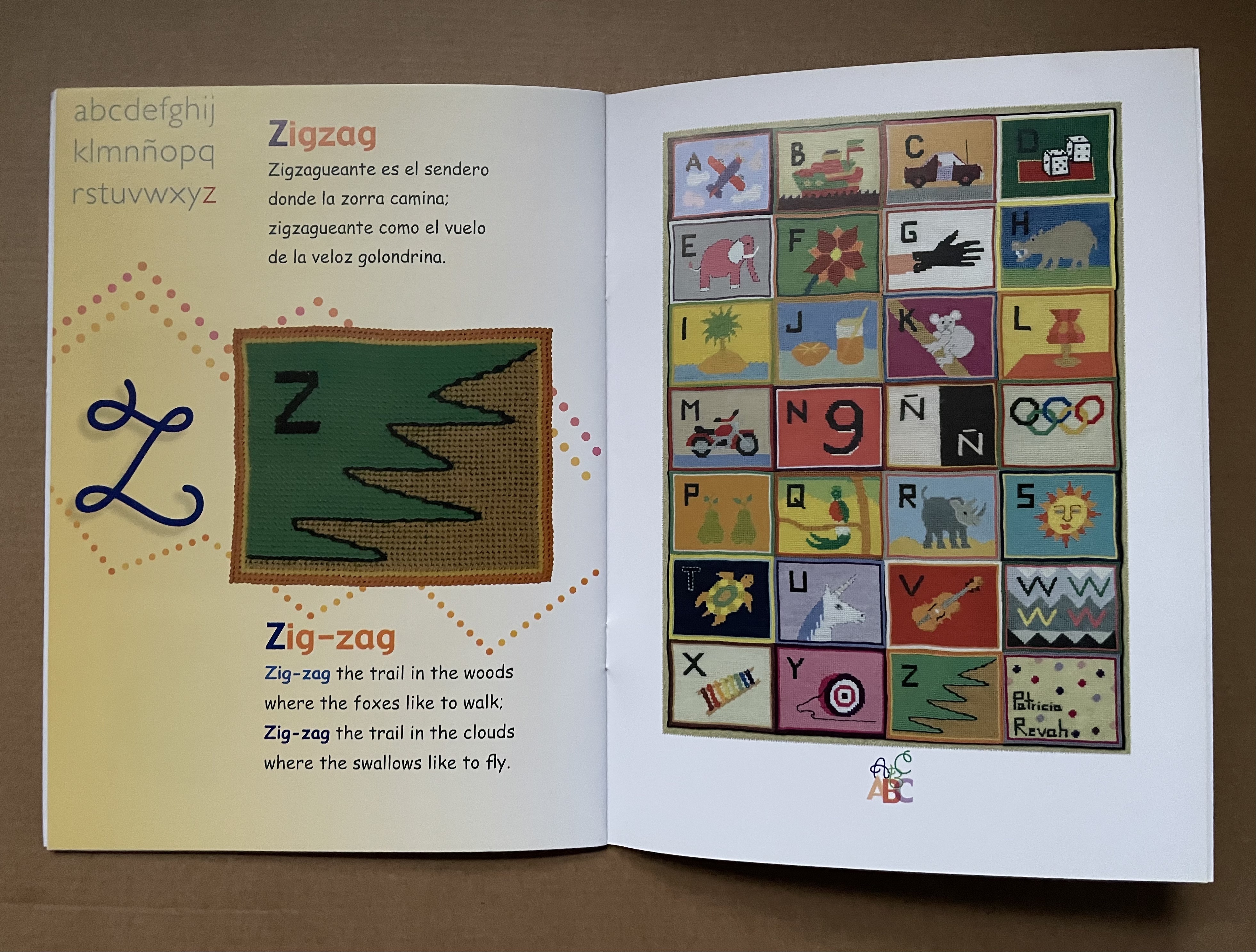

ABC (2008)

ABC (2008)

©Alberto Blanco and Patricia Revah

Softcover, saddle stitched H230 x W170 mm. 32 pages. Acquired from The Book Depository, 11 July 2021.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Alberto Blanco.

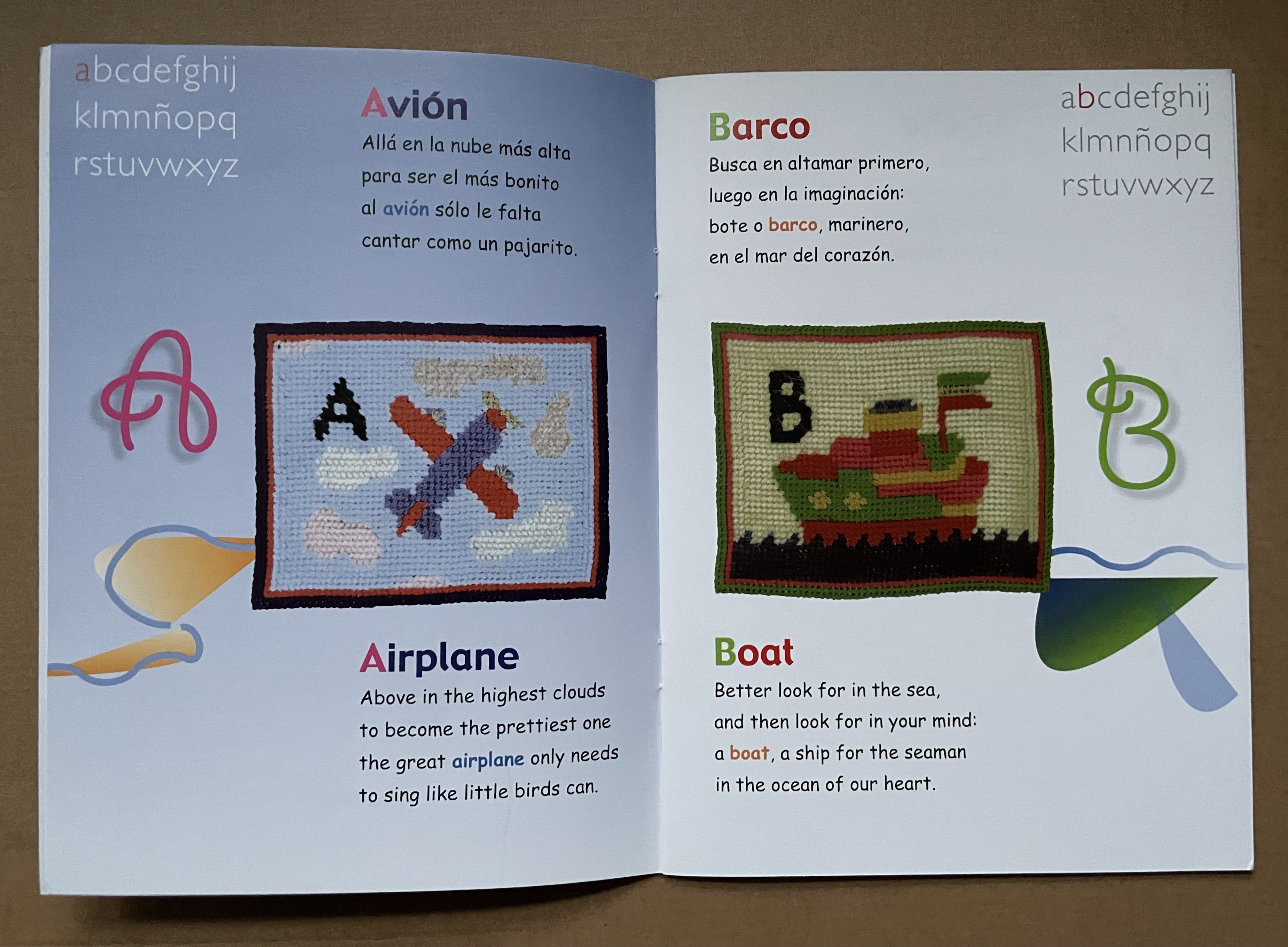

Rhyming poetry often raises the already high bar to translation. The literal English translations that follow Alberto Blanco’s charming abab Spanish poems do not attempt to substitute suitable rhymes. The textile art in this abecedary, however, wraps a comforting quilt around the challenge of translating poetry in a way that appeals to children.

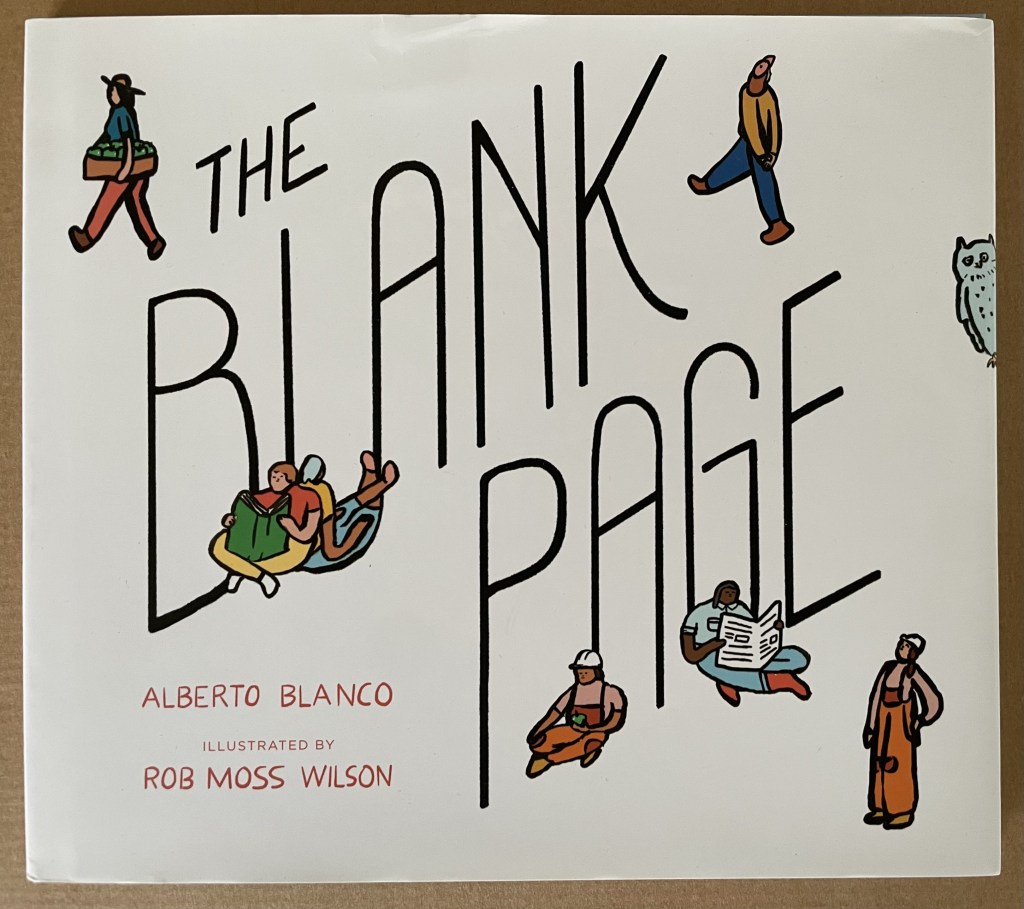

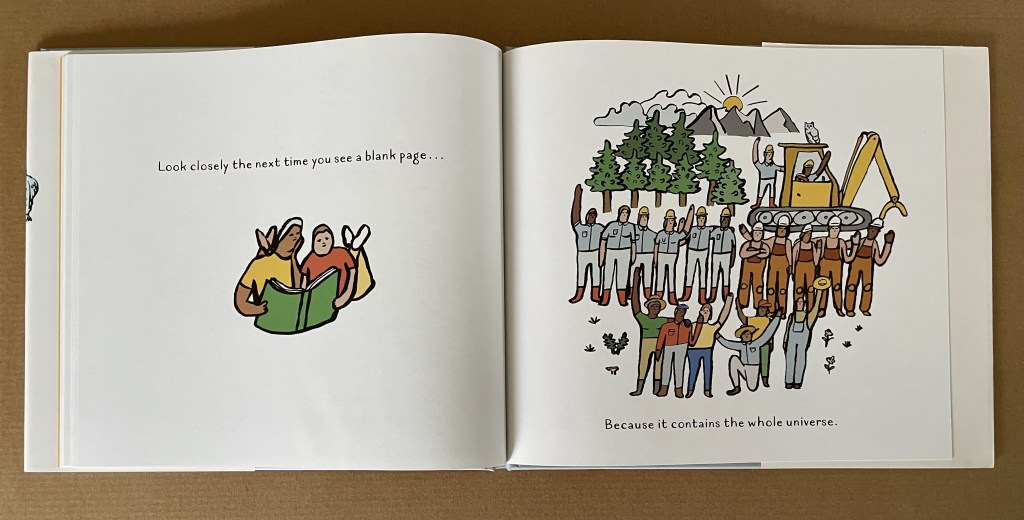

The Blank Page (2020)

The Blank Page (2020)

©Alberto Blanco and Rob Moss Wilson

Jacketed, casebound, illustrated paper over boards. H224 x W252 mm. 32 pages. Acquired from The Monster Bookshop, 1 July 2021 1 Jul 2021.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Alberto Blanco.

Who would think it possible to introduce children to the ideas of Stéphane Mallarmé? Alberto Blanco for one, albeit without mentioning the French poet.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

“Alphabets Alive!” 19 July 2023. Books On Books Collection.

“‘Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira l’Appropriation’— An Online Exhibition“. 1 May 2022. Books On Books Collection.

Blanco, Alberto. 2011. Visual Poetry/Poesía Visual. La Jolla, Calif.: The Athenaeum Music & Arts Library.

Blanco, Alberto. 1995. Dawn of the Senses : Selected Poems of Alberto Blanco. San Francisco: City Lights Books.

Blanco, Alberto. 2007. A Cage of Transparent Words : A Selection of Poems = Una Jaula de Palabras Transparentes. First edition. Fayetteville, N.Y.: Bitter Oleander Press.

“

Dear Robert Bolick,

For over 40 years in books and other artworks, I’ve explored a geometric transliteration of the spelling of words that visually reveals an unexpectedly meaningful patterning in the alphabetic sequencing. In recent years, my project has attracted a small following in a variety of academic fields, They believe my project challenges the accepted idea in linguistics and philosophy that the signs of language are fundamentally arbitrary (In addition to my imagery of the alphabetic patterning, new research in the perception and processing of the signs of language indicates Saussure’s assumption was based on an incorrect view of how the signs are perceived).

However, reopening the question of the nature of the signs of language will adversely impact the published work of a large number of academics. For example, it could mean that all the research concerning the Indo-European predecessor of our language could be misguided–the similarity in the signs of all the so-called descendant languages could actually result from innate aspects of human perception and language-creation that caused the independent choices to have relational similarities, rather than being descended from an unidentified culture that impacted a huge percentage of the world’s languages (this was never investigated because of the acceptance of the assumption that the signs of language were arbitrary).

Consequently, there have been attempts to block the discussion of my work in linguistics and philosophy. But because I’m an artist with a significant following, I have access to publishing venues outside the academic context. I wrote a chapter in my 2021 memoir that is now being discussed in the literary and art departments of some major universities, and in a few philosophy departments by a younger generation of professors–that chapter is now freely accessible online at: https://philpapers.org/archive/WINFTI-2.pdf

The more people who know about this in the cultural community, the more difficult it will be to prevent open discussion. The discussion of the nature of the signs of language should not be closed forever based purely on an assumption made over a century ago that we now know has lost the logic of its foundation.

Thanks so much for reading,

Michael

LikeLike