I tried to “define the book” when I designed (one of my books) Cover to Cover hoping that the “reader” would have a multi-sensory experience of the nature of what she/he held in her/his hands. (from The Book: 101 Definitions)

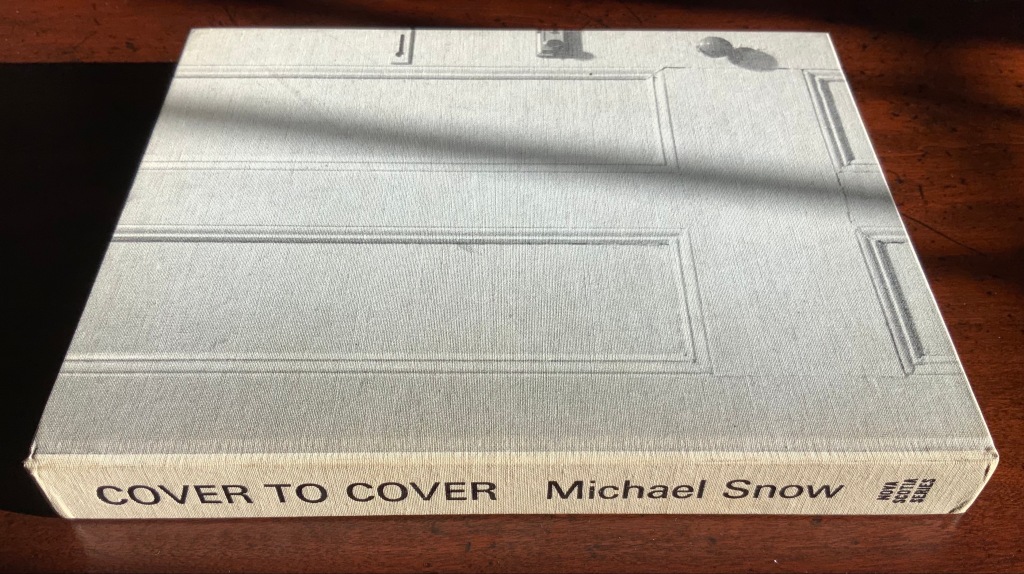

Cover to Cover (1975)

Cover to Cover (1975)

Michael Snow

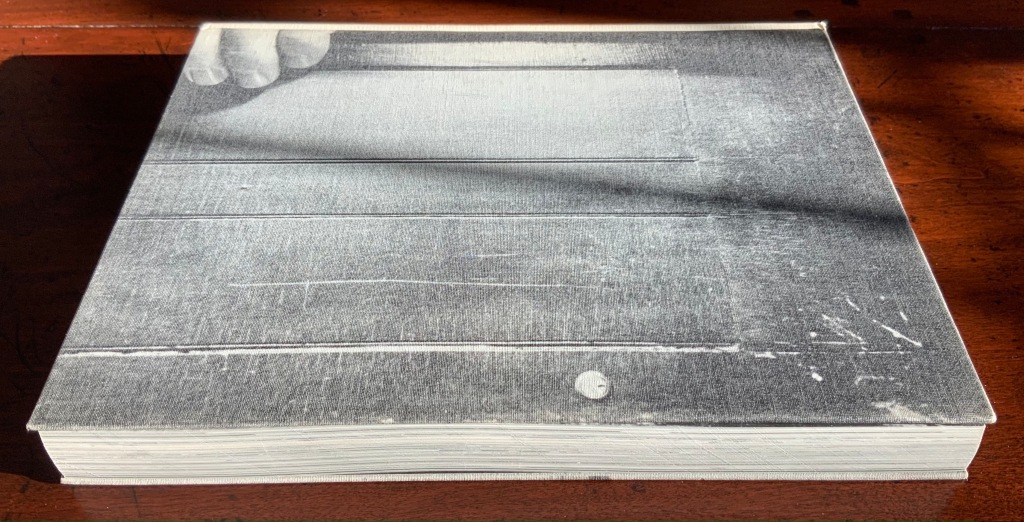

Cloth on board, sewn and casebound. H230 x W180 mm. 310 unnumbered pages. Published by Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Unnumbered edition of 300. Acquired from Mast Books, 10 December 2020. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

After a long search since first sight of it in 2016 at Washington, D.C.’s now defunct Corcoran Gallery library, the original hardback edition of Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover (1975) finally joins the Books On Books Collection. Thanks to Philip Zimmermann, more readers/viewers have the chance to experience Cover to Cover — if only through the screen — than the original’s 300 copies and Primary Information’s 1000 facsimile paperback copies will allow.

Amaranth Borsuk describes the work and experience of it in The Book (2018), as do Martha Langford in Michael Snow (2014), Marian Macken in Binding Spaces (2017) and Zimmermann in his comments for the exhibition “Book Show: Fifty Years of Photographic Books, 1968–2018” (for all, see links below). Like Chinese Whispers by Telfer Stokes and Helen Douglas and Theme and Permutation by Marlene MacCallum, Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover evokes an urge to articulate what is going, how the bookwork is re-imagining visual narrative, how it is making us look, and how it makes us think about our interaction with our environs and the structure of the book.

The already existing commentary about Cover to Cover sets a high hurdle for worthwhile additional words. One thing going on in the book, though, seems to have gone unremarked. Some critics have asserted that, other than its title on the spine, the book has no text. There is text, however. It occurs within what I would call the preliminaries, and they show us how to read the book.

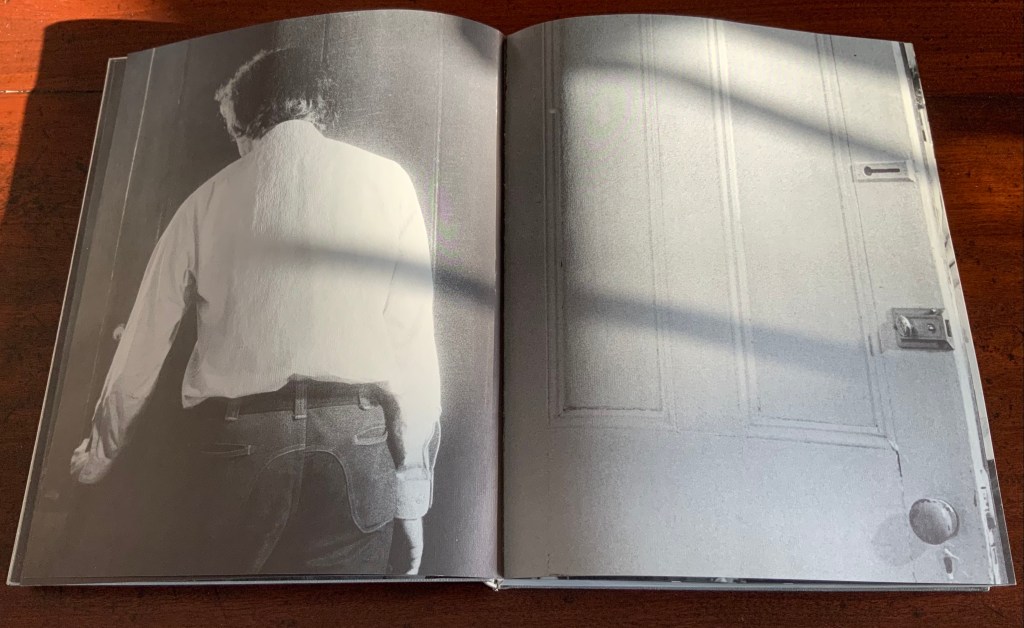

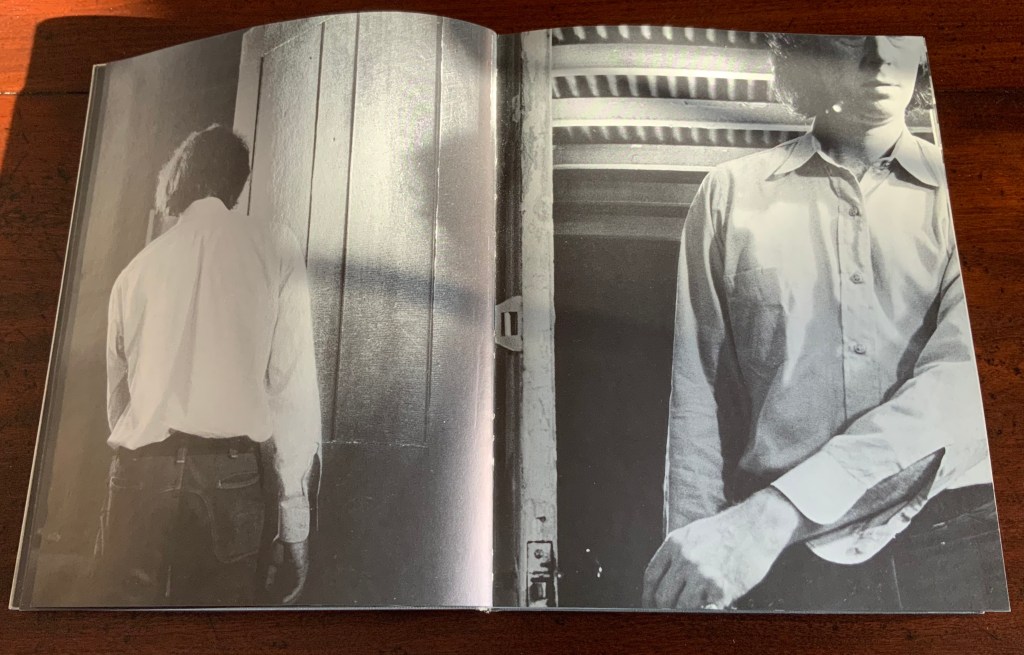

On the front cover, we see a door from the inside. Then, on its pastedown endpaper, the author outside the door with his back to us.

Front cover; pastedown end paper and page “1”.

On turning the “inside door” (page “1” of the preliminaries), we see in small type a copyright assertion and the Library of Congress catalogue number appearing vertically along the gutter of pages “2-3” (a tiny clue as to what is going on).

Pages “2-3”

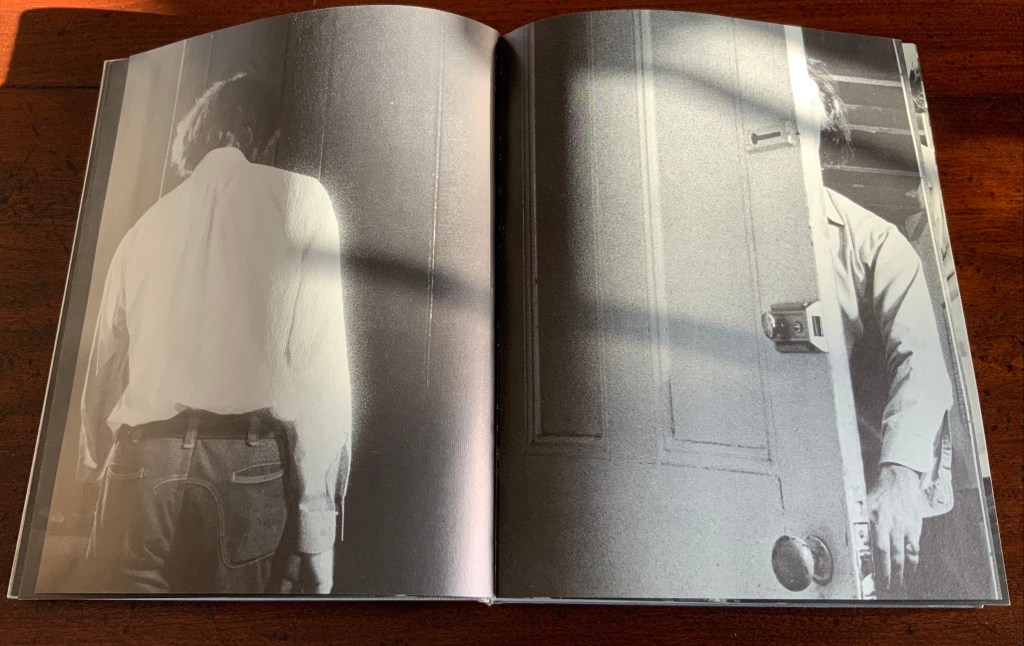

Over pages “4” through “14” from the same alternating viewpoints, the author reaches for the door handle, the door is seen opening from the inside, and the artist is seen walking through the door (from the outside) and into the room (from the inside). But who is recording these views?

Pages “10-11”, “12-13”, “14-15”

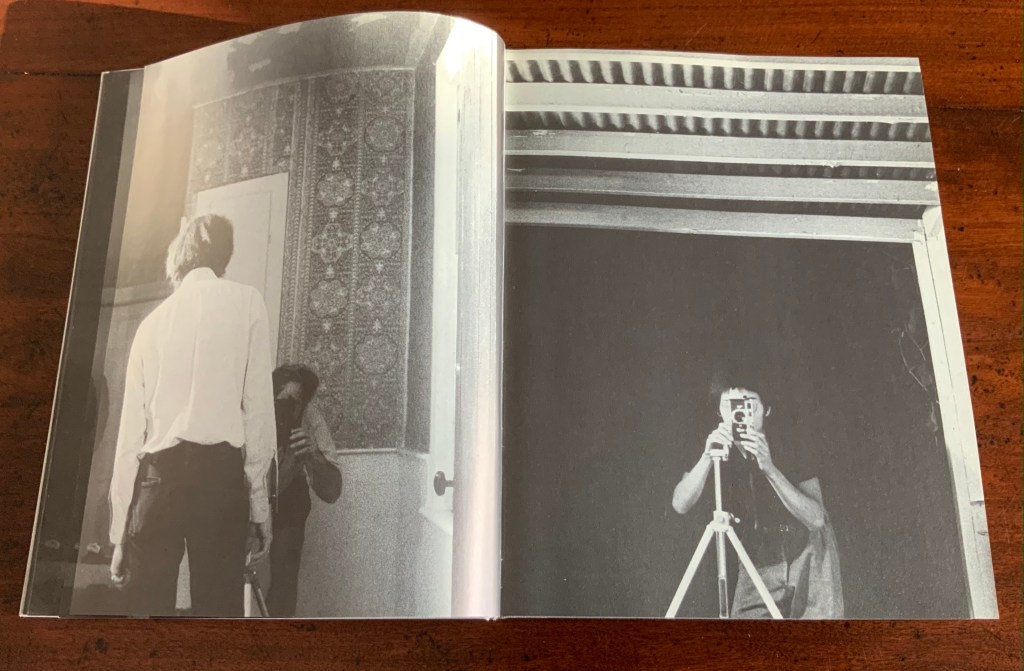

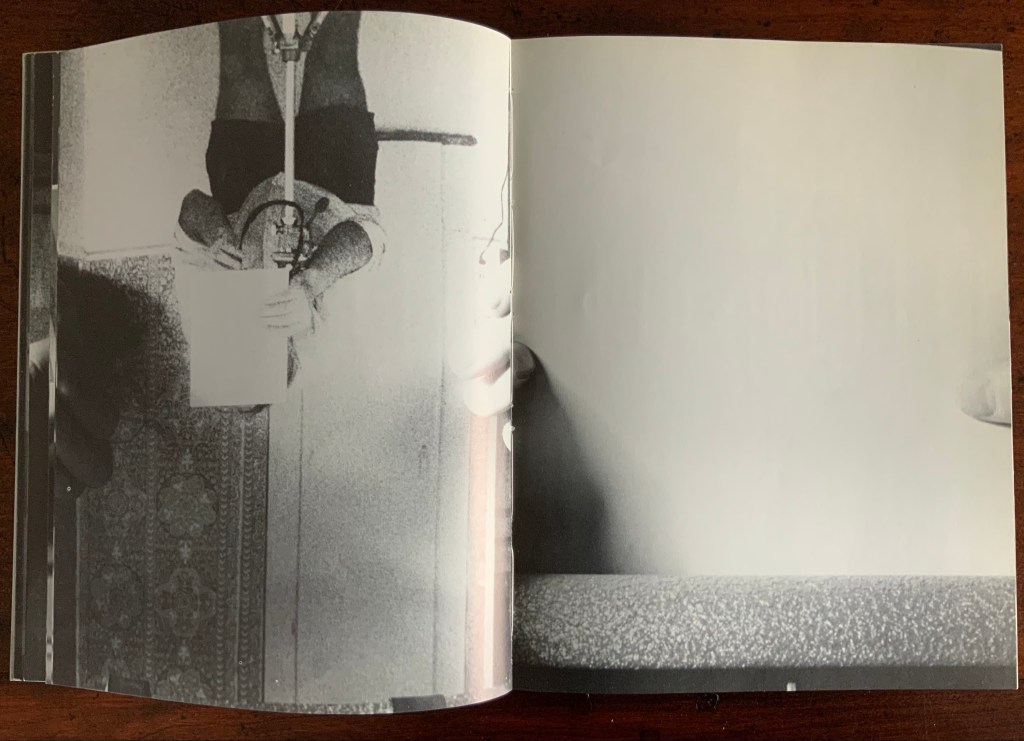

Over pages “16” through “24”, two photographers appear. Facing us, they are bent over their cameras — the one outside, clean shaven and wearing a short-sleeved shirt, is behind the author, and the one inside, bearded and wearing shorts, is in front of the author. As the author moves out of the frame, we see that the photographer inside is holding a piece of paper in his right hand. All of this occurs through the same alternating viewpoints. At page “21”, the corner of that paper descends into the frame of the inside photographer’s view of the outside photographer, and after the next switch in viewpoint that confirms what the inside photographer is doing, we see a completely white page “23”, presumably the blank sheet that is blocking the inside photographer’s camera aperture. Page “24” is the outside photographer’s view of the inside photographer whose face and camera are blocked by the piece of paper.

Pages “16-17”, pages “20-21” and pages “24-25”

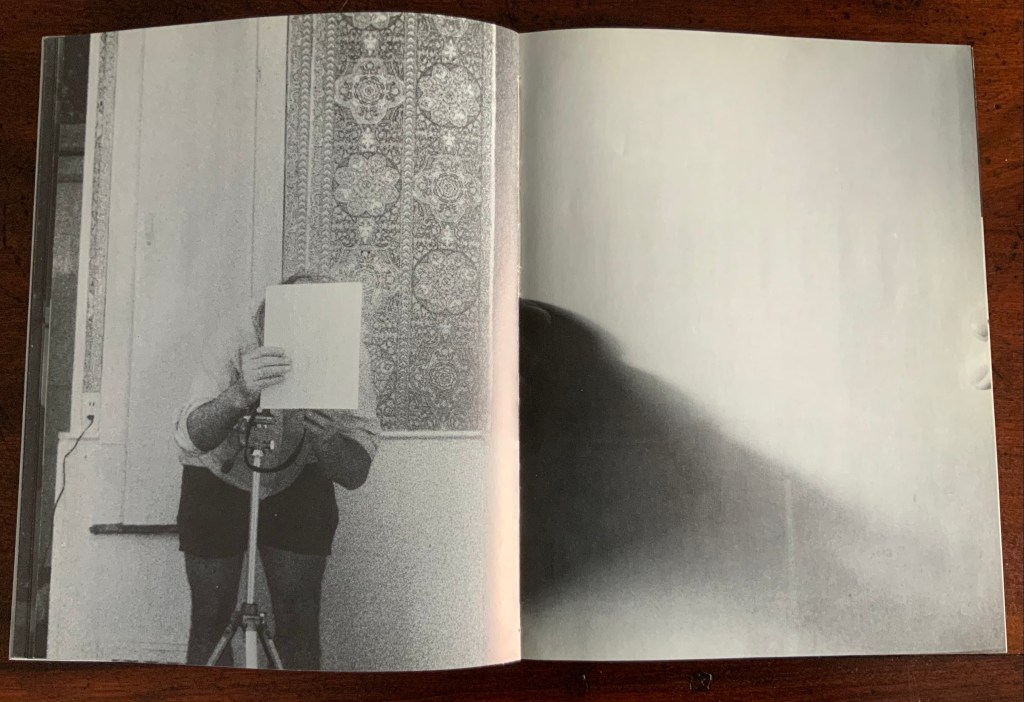

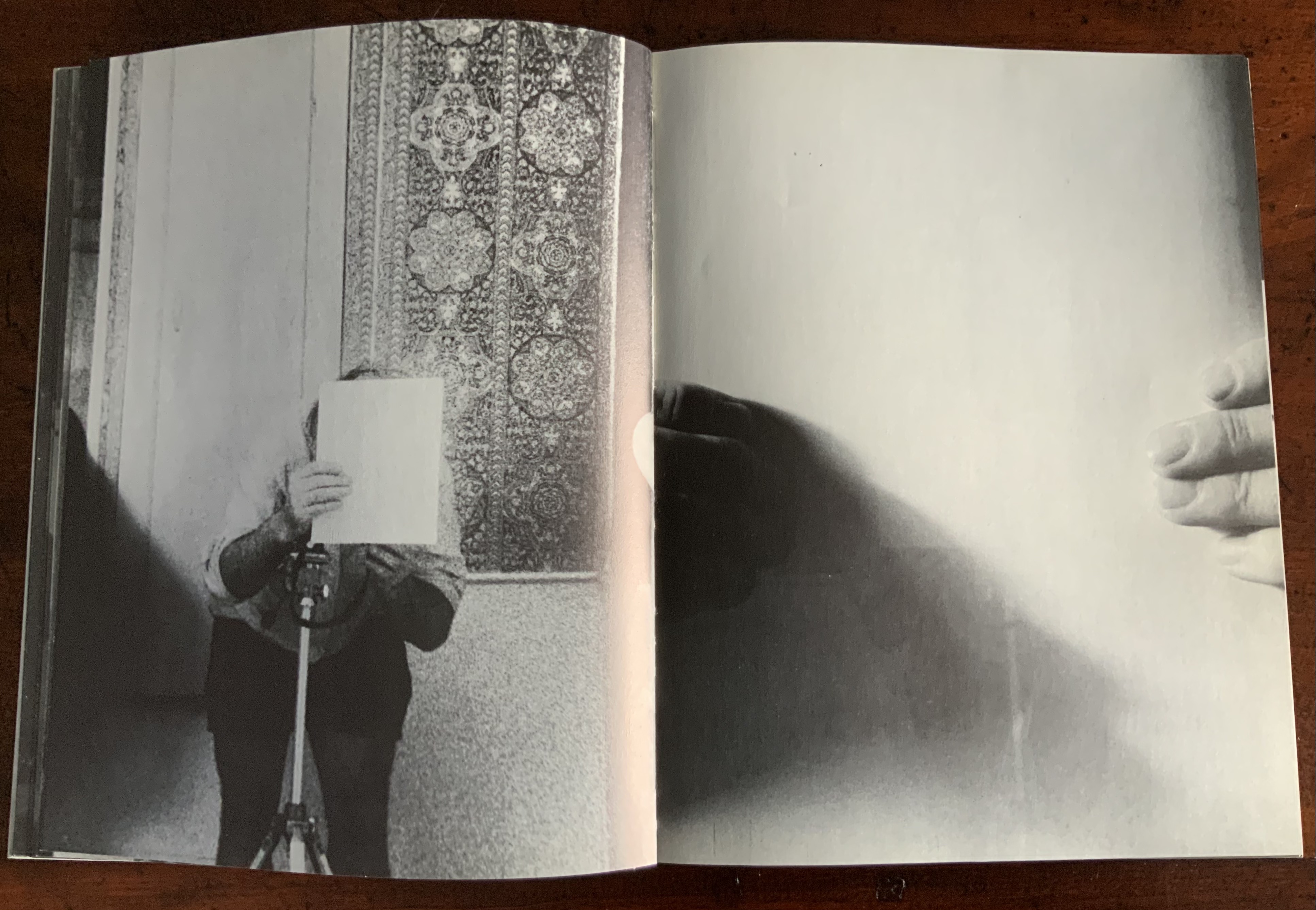

After the sequence above, something stranger still happens: on the left, a photo of the inside photographer holding the blank paper in front of his face appears. We can tell it is a photo by the tip of the thumb holding it (look in the gutter) between pages “26 and 27”. It is the developed photo the outside photographer just took of the inside photographer with his face and camera hidden by the sheet of paper. The image on page “27” is the reverse of that photograph. We can tell by the fingers on the right holding it.

Pages “26-27”

We are looking at images of images. But on pages “30-31”, whose fingers are holding the image of images?

Pages “30-31”

From there on, we see images of this piece of paper being manipulated by one pair of hands. The thumbs appear on the verso (the view from the outside photographer’s perspective), the fingers on the recto (the view seen by the inside photographer). By page “34”, it has been flipped upside down (the inside photographer is standing on his head), and on page “35”, we see a close up of the blank reverse side of the paper being held between the two photographers. By page “37”, we can see the blank side of the photo paper being fed into a manual typewriter. The pair of hands feeding the paper into the typewriter cannot belong to one of the photographers. Who is the typist — the author?

For both pages “42” and “43”, the perspective is that of a typist advancing the photo paper and typing the title page of the book. On both pages, we can see the ribbon holder in the same position. As it progresses, more and more of the outside photographer’s camera appears above the typed page. Page “45” presents itself as the full text of the book’s title page, curling away from the typist and revealing the inside photographer on the other side of the typewriter. Page “46” shows the upside-down view of the title page as it moves toward the inside photographer and reveals the outside photographer on the other side of the typewriter. Not only are we seeing images of images, we are witnessing the making of the book’s preliminaries.

From page “48” through page “54”, the photographers alternate views of blank paper advancing through the typewriter. By pages “55” and “56”, the typewriter has moved out of the frame. Look carefully at page “56”, however, and you can see the impression of the typewriter’s rubber holders on the paper. As a book’s preliminaries come to a close, there is often a blank verso page before the start of the book. If Cover to Cover is following that tradition, page “56” is that blank page at the end of the preliminaries, and page “57”, showing a record player, is the start of the book.

Pages “56-57”.

Zimmermann notes that, at somewhere near the book’s midpoint, the images turn upside down, and that readers who then happen to “flip the book over and start paging from the back soon realize that they are looking at images of images produced by the two-sided system, and indeed the very book that they are holding in their hands”. He notes this as another mind-bender added to the puzzlement of the two-sided system with which the book begins. Yet the long set of preliminaries foretold us that the upside-downness, back-to-frontness and self-reflexivity of images of images were on their way. Without doubt, Cover to Cover is an iconic work of book art.

Further Reading

Afterimage (1970). No. 11, 1982/83. On the occasion of an exhibition of his films at Canada House in London, an entire issue on Snow’s work.

… Cover to Cover is the result of another distanced use of self in the course of art-making. Snow is subject/participant as he and his actions are observed and analyzed by two 35 mm cameras… simulataneously recording front and back, the images then placed recto-verso on the page… Snow is subject observed in the book at the same time that he is also choosing and making decisions about images. Cover to Cover in 360 pages, [sic] becomes a full circle — front door to back door or the reverse. The book is designed so that it can be read front to back and in such a way that one is forced to turn it around at its centre in order to carry on. Regina Cornwell in Snow Seen and “Posting Snow”, Luzern catalogue.

Borsuk, Amaranth. The Book (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018).

Borsuk, Amaranth, ed. 2021. The Book : 101 Definitions. First edition. Montreal: Centre for Expanded Poetics : Anteism Books.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 2002. Writing Machines. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. See p. 68.

“Ellen Lanyon“. 25 June 2024. Books On Books Collection. For comparison of Cover to Cover with Transformations I (1977).

Langford, Martha. Michael Snow: Life & Work (Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2014).

Macken, Marian. Binding Space: The Book as Spatial Practice (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017).

Michelson, Annette, and Kenneth White. Michael Snow (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019).

Zimmermann, Philip. “Book Show: Fifty Years of Photographic Books, 1968–2018“, Spaceheater Editions Blog, 3 February 2019. Accessed 16 December 2020.

But as the scene “progresses,” an action is not completed within the spread, but loops back in the next one, so that the minimal “progress” extracted from reading left to right is systematically stalled each time a page is turned, and the verso page recapitulates the photographic event printed on the recto side from the opposite angle. This is the disorienting part: to be denied “progress” as one turns the page seems oddly like flashback, which it patently is not; it might be called “extreme simultaneity.” Two versions of the same thing (two sides of the story) are happening at the same time. Zimmerman.