Alphabetum Romanum (c. 1460)

Alphabetum Romanum: The Letterforms of Felice Feliciano

Felice Feliciano (c. 1460)

Jason Dewinetz, drafting/printing (2010) and Mark Cockram, bookbinding (2022)

Boxed and casebound, sewn. Box: 222 x 172 x 30 mm. Book: 202 x 155 mm. 82 pages. Sheets acquired from designer/publisher. Binding acquired from designer book binder.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

One of the pleasures of collecting alphabet-related works and living close to Oxford University is the opportunity to place new work next to older ones. An added pleasure in this case is seeing a new work made newer by a designer bookbinder.

As the foreword and afterword to this work explain, Jason Dewinetz’s redrawing of Felice Feliciano’s letterforms (c. 1460) was in fact prompted by two 20th century responses to Feliciano’s original: the first being Giovanni Mardersteig’s edition in 1960 at Editiones Officinae Bodoni and the second, also overseen by Mardersteig, being the facsimile edition issued by Jaca Book Codici over 1985-87 and separately by Belser Verlag in 1985. The Bodleian Library has both the Officinae Bodoni and Belser editions. An opportunity too good to miss and one worth sharing.

Left: Dewinetz edition. Center: Feliciano’s original in the Vatican facsimile. Right: Officinae Bodoni edition. Photo: Books On Books.

Dewinetz does not reproduce Feliciano’s commentary. His aim is to focus attention entirely on the letters. Although he has restricted his re-presentation of the letters to the recto page (whereas in Feliciano’s original, the letters after A occupy the verso and recto), he is too clever a designer not to find a way to capture the one instance in which Feliciano’s letter drawing and double-page spread interact entertainingly.

For the opening of Paul F. Gehl’s foreword, Dewinetz captures the dramatic flourish of Feliciano’s Q,

whose tail crosses the double-page spread in his original. See below. Photos: Books On Books.

From the Vatican facsimile, Feliciano’s double-page spread with Q and S. Photo: Books On Books.

What happened to the letter R? Feliciano must have felt the need to give it its own double-page spread to show off a variation in coloring and tails. Like Mardersteig, Dewinetz gives the Rs each their own page. Unlike Mardersteig (and Feliciano), he places the Rs in correct alphabetical order.

Feliciano’s letter Rs from the Vatican facsimile. Photo: Books On Books.

Dewinetz’s re-drawing Q,R,R,S. Photo: Books On Books Collection.

Mardersteig follows Feliciano’s disrupted alphabetical order, but for Q and S to keep to a design that places each letter on a recto page facing a schematic drawing on the verso, Mardersteig has to forego the center-crossing tail of the Q and place S on a separate insert leaf.

Mardersteig’s QSRR sequence in the Ediciones Officinae Bodoni edition. Photo: Books On Books.

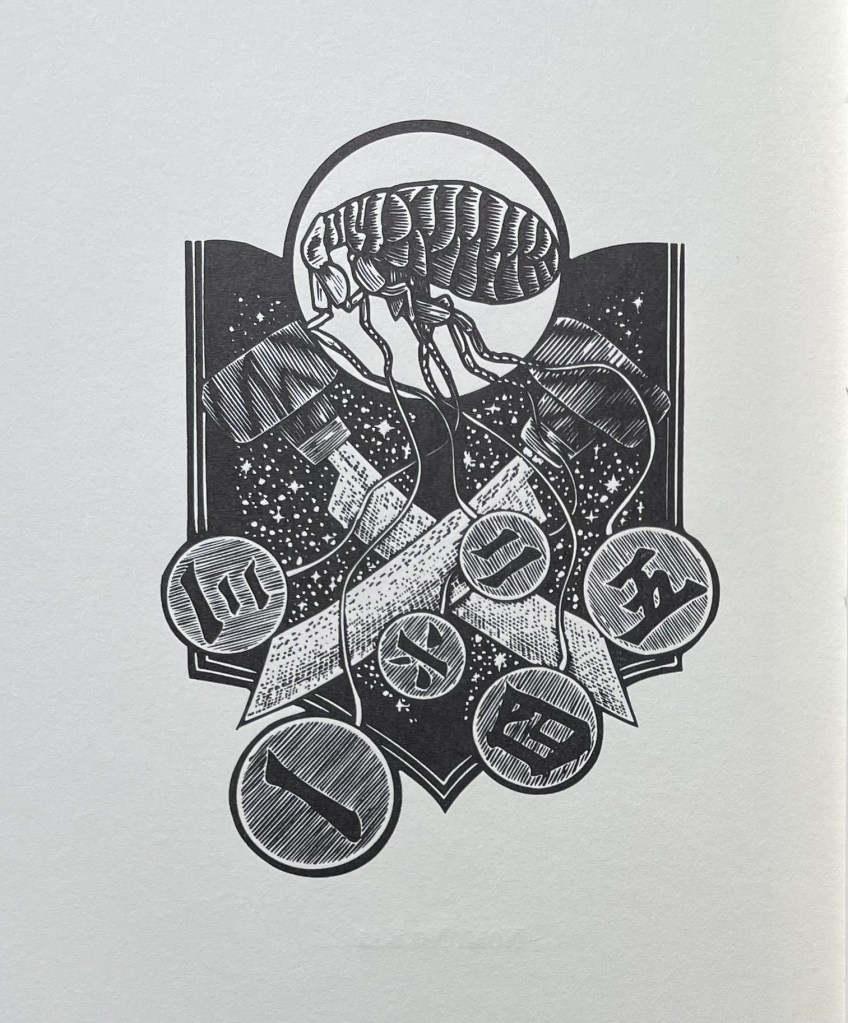

As a designer bookbinder, Mark Cockram has a deft eye and touch as he looks for and executes the designs inspired by the text. He could not resist Dewinetz’s cropped Q from the foreword by Paul F. Gehl. Taking his Q (as it were) however from the Goudy display font, he gives it a deserved prominence, stamped in black, on the double-trayed box’s spine. The choice of a different font reminds me of Eric Gill’s quip: “letter designing is still an occupation worthy of the enthusiasm of rational beings, and, though a Q which were all queue & no Q would be ‘past a joke’, it is difficult to say exactly where a tail should end”.

Left photo: Courtesy of Mark Cockram. Right photo: Books On Books Collection.

Apparently it was a tail of which Cockram could not let go. Further echoing Dewinetz’s cropping, truncated letter forms peek through the Palimpsest Parchment with which the book itself is bound (flat back). They are laserprinted on hand colored papers, colors inspired by those used in the book. Cockram also echoes the book’s color “ghosting” on the box by layering blank strips of hand colored papers beneath the cloth during the making process. The color-echoes between box and book continue with the box’s interior.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

The handsome bindings of the Vatican facsimile and Mardersteig edition have stood up to their library existence. In muted tones and gilt, they speak to the design esthetics of a different era.

Vatican facsimile binding

Officinae Bodoni edition binding

When the Dewinetz/Cockram edition joins the Vatican facsimile and Officinae Bodoni edition at the Bodleian, students of lettering, type design, bookmaking and bookbinding and their history will have a feast of an opportunity to compare and contrast.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

Gill, Eric. 1931. An essay on typography. London: Sheed & Ward.

Feliciano, Felice, & Mardersteig, Giovanni. 1985. Alphabetum romanum: Vat. Lat. 6852 : Aus der Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana (Codices e Vaticanis selecti ; v. 70). Zürich: Belser Verlag.

Feliciano, Felice, Mardersteig, G., & Ferrari, O. 1960. Alphabetum Romanum (Ital. ed.] ed., Biblioteca apostolica vaticana. Mss. (Cod. Vat. 6852)). Verona: Officinae Bodoni.