Between Page and Screen (2012)

Between Page and Screen (2012)

Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse

Website: Accessed 16 May 2014. Book: Perfect bound, H178 x W179 mm, 44 pages. Acquired 16 May 2014.

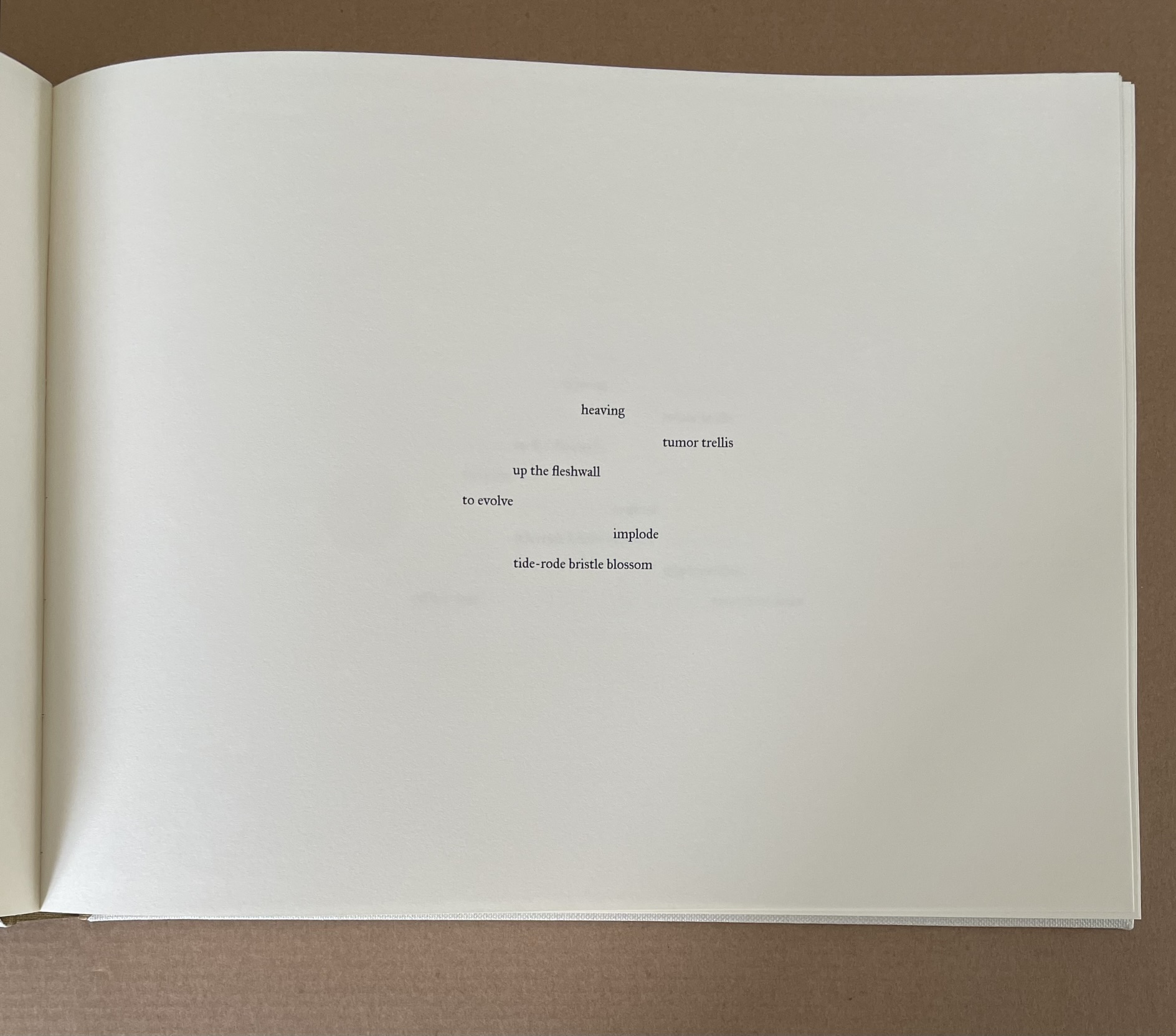

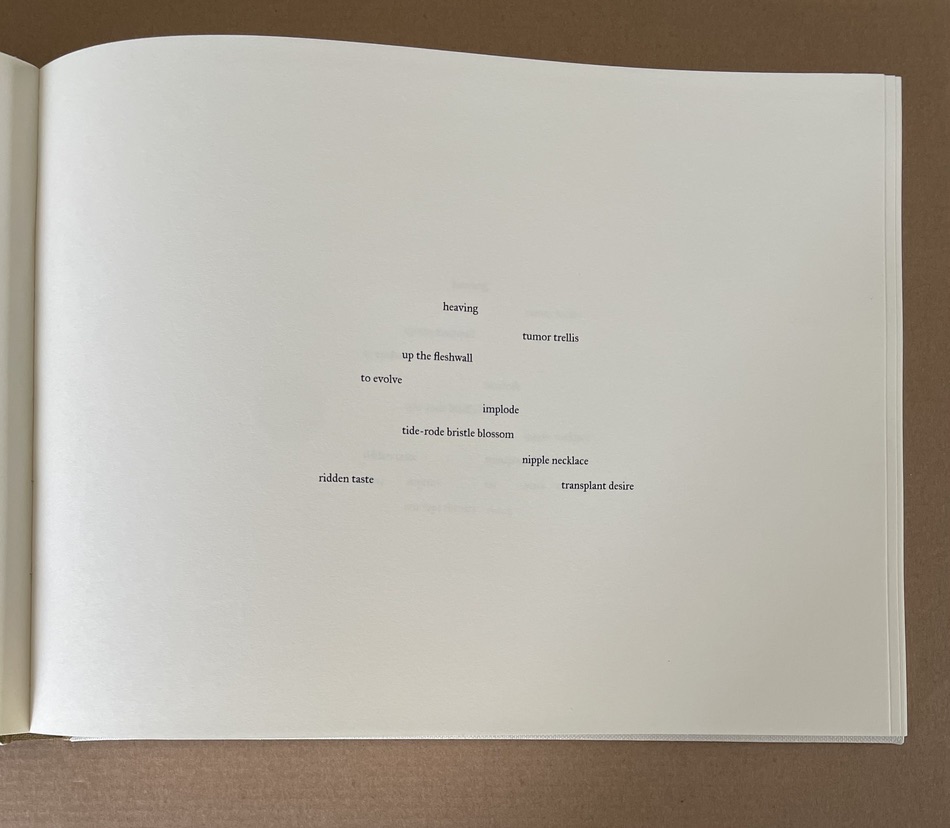

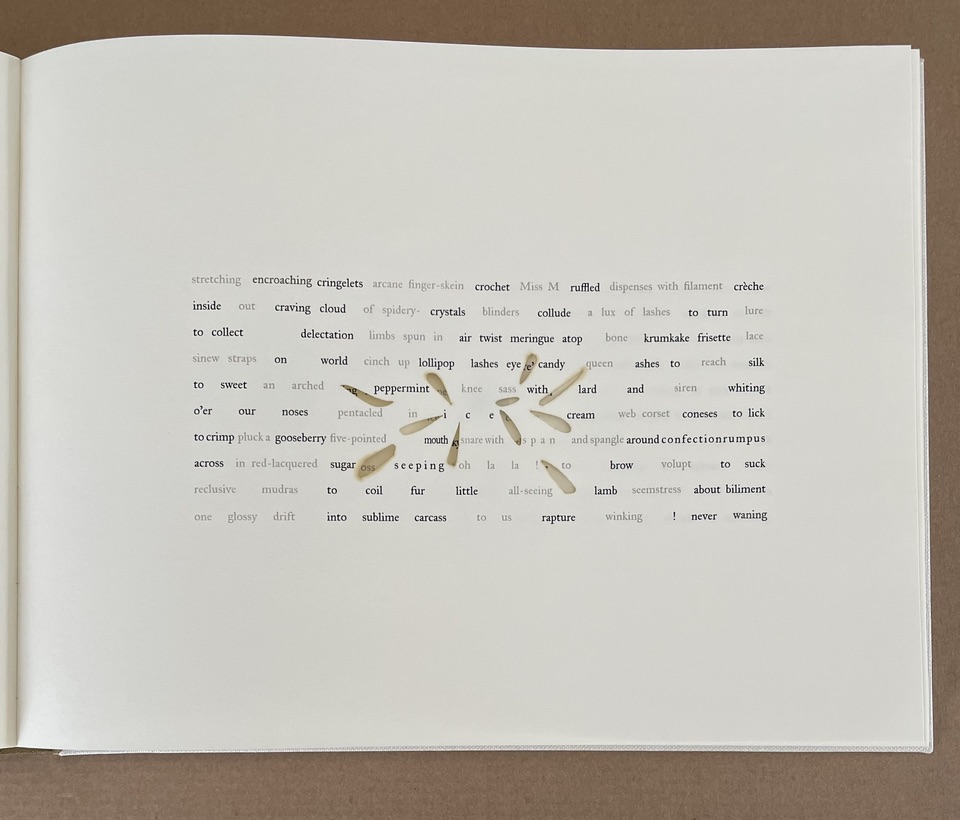

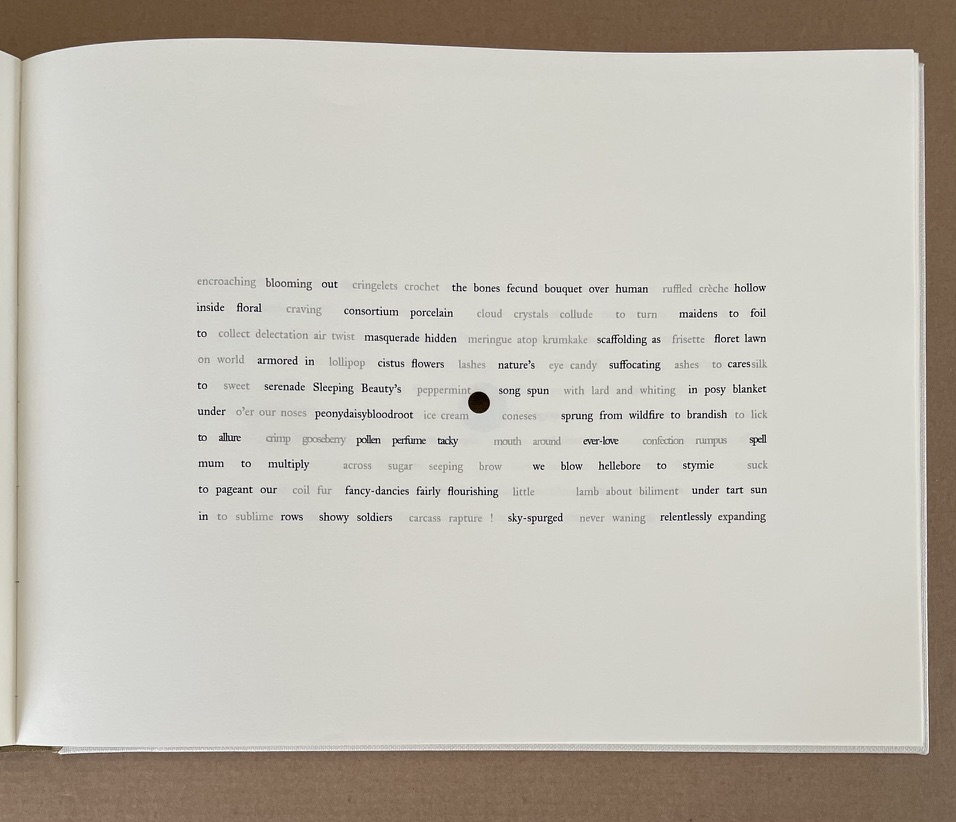

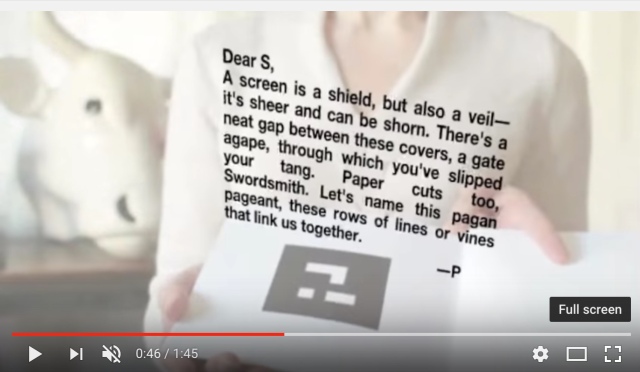

Between Page and Screen chronicles a love affair between the characters, P and S…. The book has no words, only inscrutable black and white geometric patterns that — when seen by a webcam — conjure the written word. Reflected on screen, the reader sees himself with open book in hand, language springing alive and shape-shifting with each turn of the page. The story unfolds through a playful and cryptic exchange of letters between P and S as they struggle to define their relationship. Rich with innuendo, anagrams, etymological and sonic affinities between words, Between Page and Screen revels in language and the act of reading. Publisher’s description.

Within months of its publication, this digital work of book art received attention from Johanna Drucker during the Tate Britain workshop “Transforming Artist Books (February 2012 — August 2012)“:

The finitude of a bound codex quite literally defines its limits in analogue form. Even … gesturing outward to the world of lived and imagined phenomena that comprise a shared realm of cultural knowledge, the book’s dimensions remain linked to its physical form. But where is such a book located in the spatial-temporal realms of networked environments? And when is a work produced? … Borsuk and Bouse’s depends on a linked connection between quick response (QR) codes on pages and files stored online. The capacity to conjure stored material that projects itself in augmented screens onto the perceived world further erodes the boundaries of interior/exterior edge and periphery that were traditionally defining features of an aesthetic work.

Between Page and Screen has been displayed in exhibitions such as “The Art of Reading (18 November 2017 — 4 March 2018)” held at the Meermanno Museum in The Hague. Unusually, at that exhibition, the art was not simply on display. Touching was allowed. Paul van Capelleveen, one of the curators organizing the show, insisted that each work be touchable. As a curator at the Dutch national library and advisor to the Meermanno, he felt strongly that the challenges of multimodal literacy cannot be understood “under glass”. Apparently, the market agrees: Between Page and Screen is now in its second edition.

Further Reading

Created for the November 2016 issue of The Bellingham Review, “Abra: The Kinetic Page” is a polymorphic tour de force – online prose poem, video, review of and homage to an installation at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, WA, in 2014 and a promotion of the artists’ book Abra: The Living Book by Kate Durbin, Amaranth Borsuk and Ian Hatcher, published in 2014.

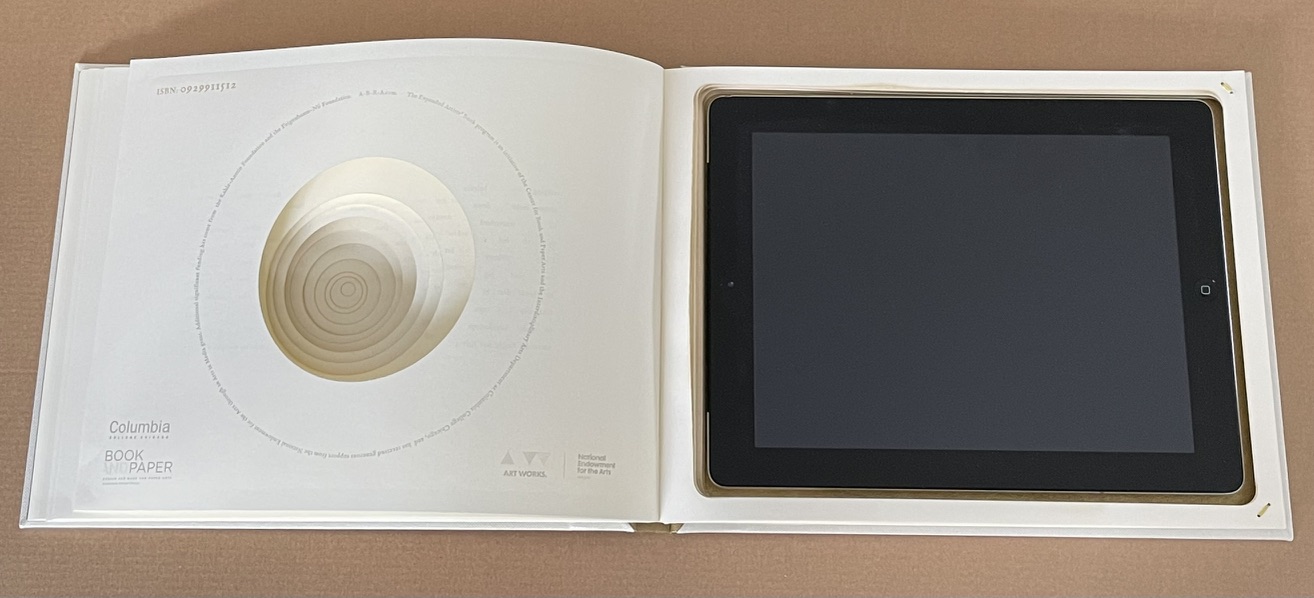

From where did such work spring? From a project called “Expanded Artists’ Books: Envisioning the Future of the Book”. Inspired by the advent of the iPad in 2009 and a symposium held in 2011 with Bob Stein, Director of the Institute for the Future of the Book, Steve Woodall, then Director of Columbia College’s Center for Book and Paper Arts, secured funding for that project from the National Endowment for the Arts in 2012. Woodall later explained the intent of the project in that same workshop where Johanna Drucker drew attention to Between Page and Screen:

In its first phase, our project takes existing artist books and creates iPad applications that both represent and contextualise them. The apps will be made available as free downloads. With the many millions of portable devices running on the iOS platform, the reasoning goes that an under-distributed and too-obscure art form can gain wider reach and achieve greater public awareness. We will soon expand to include Android and other platforms, but we expect to stay within the ‘walled garden’ world of the app, as opposed to the open range of a purely browser-based platform – we feel that the smoother functionality and higher-quality user experience of the app work well with the expanded practices of authorship and craft engagement that define artist books.

In the project’s second phase we shall commission media artists to create born-digital artist book/apps, which will then be reverse engineered as physical books, or created in parallel with them. Owing to the creative countercharge it represents, we find this to be an extremely interesting phase of the project from a research standpoint.

…

It is the dialogue between the physical books and their digital avatars that provides a great part of the value of this project. … it is in the artist’s studio, whether that be an electronic workstation or a more traditional book art studio, where the dialogue will play out in the creative process. Artists will explore ways in which expression can take both virtual and physical manifestations, examining the advantages of each and how the interplay between the two can be leveraged to provide a comprehensive and powerful expression. Woodall, “Artists, Writers and the Future of the Book“.

Abra was funded by a grant from this project, and with Abra, Borsuk, Durbin and Hatcher have manifestly “embodied” the sponsor’s intent as will become clear as you read. But pause first on Borsuk’s Bellingham Review piece.

Borsuk is an inspired writer, a gifted conceptual and haptic artist. “Abra: The Kinetic Page” starts as a reflection on experiencing Ann Hamilton’s installation the common SENSE with its exploration and celebration of “touch”:

As I walked through the upper galleries, where newsprint images of the undersides of birds and small animals fluttered in the HVAC breeze, I thought about the way the exhibit invited us to read space. Hamilton’s juxtapositions, like the lines of a poem, rely on the visitor to bridge the between with their body. We provide the spark that leaps across the enjambed line where the tale of Cock Robin meets a downy hide.

○

I’ve strayed from what I wanted to tell you because Hamilton’s work requires it. It is, as she says, a form of attention she seeks to share with her audience—she creates installations as spaces animated by the viewer. She sets up the conditions for an experience or interaction, and then withdraws, trusting the reader / viewer / visitor to make meaning. To limn the contours of the work with their own gentle touch.

○ [Now note here how she pivots to experiencing Abra.]

As I trace my finger along Abra’s cover, whose title is also the incipit, silently voiced by the reader, which activates the text, I’m invoking not only the magic word that brings things to pass as they are spoken, I’m invoking Hamilton, whose “handseeing” videos of the late 90s and early 2000s turn the fingertip into an eye, uniting reading and writing in a gesture that links dactyl and stylus, through the digital that fits like pen in glove.

Whether read on screen or heard in the video, Borsuk’s words and sentences are tactile. Listen:

Click on the image above for the video “Abra: The Kinetic Page” by Amaranth Borsuk

“Abra: The Kinetic Page” explores and celebrates the “fundamental relationship between the eye, the brain, and, critically, the hand” as Woodall hoped. It is a work of art as much as Abra itself.

If its artistry were not enough, The Bellingham Review piece takes things a bit further than might have been expected from the “Expanded Artists’ Book” project. Interestingly, The Bellingham Review piece also addresses changes in the value chain that hybrid books and hybrid book art must confront. As originally set out by Harvard’s Michael Porter, the value chain is the “set of activities that a firm operating in a specific industry performs in order to deliver a valuable product or service for the market.” Marketing is one of those key activities in the set. In The Bellingham Review, an online and print literary magazine, Borsuk has found not only a platform for marketing Abra, but a platform from which to offer a complementary work of art in the form of a video. An example of “art for art’s sake” that finally makes sense to the business school.

The example does not end there. Reflecting in the Tate Britain workshop on the “Expanded Artist Book” project, Woodall remarked on “digitally trained designers … being drawn back to the fundamental relationship between the eye, the brain, and, critically, the hand, … photographers … combining digital processes with nineteenth-century ‘alternative’ techniques. … [and] … the enthusiasm most contemporary graphic designers have for letterpress printing.” Web skills, videographics and the YouTube/Vimeo channels are just as remarkably important, which is clear not only from the Abra site, The Bellingham Review piece but from this shorter directly promotional video:

Abra: A Living Text

Video editing by Louis Mayo

Shot by Nathan Evers at the Digital Future Lab, University of Washington, Bothell

Music: Graham Bole, “We Are One”

Woodall did wonder whether the project’s prompting a dialogue of the physical and digital would have implications for practical matters such as distribution. While Abra has a paperback version as an entry in the traditional channels to market, that offers little insight into such implications — not like the insight realized by the combination of website, promotional video and The Bellingham Review piece.

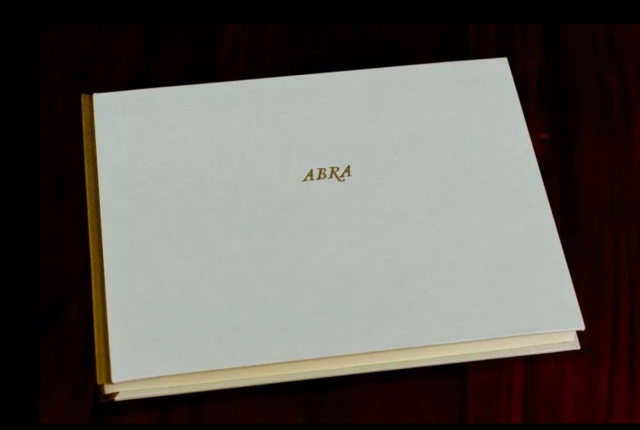

In fact, from a perspective of craft and product, the experience promised by the videos and website is completely available only if you download the app and have a copy of the limited edition of the artists’ book. Constructed by Amy Rabas, the artists’ book allows you to insert an iPad in the back of the book creating a continuous touch-screen interface. This interactivity with the reader is one more aspect of the work that realizes perhaps more than was expected from the “Expanded Artists’ Book” project.

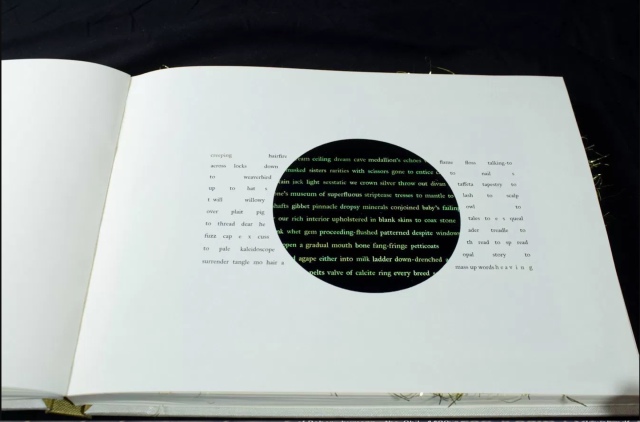

The book’s simple, mysterious foil-stamped cover. Created by book artist Amy Rabas.

Courtesy of the artists.

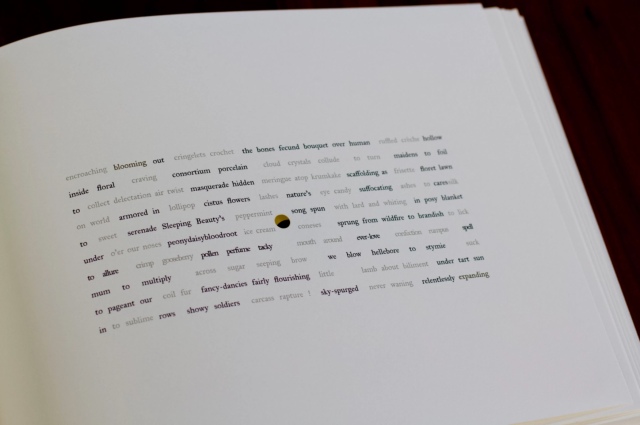

The laser-cut openings coalesce into a pinhole that begins to reveal the iPad below.

Courtesy of the artists.

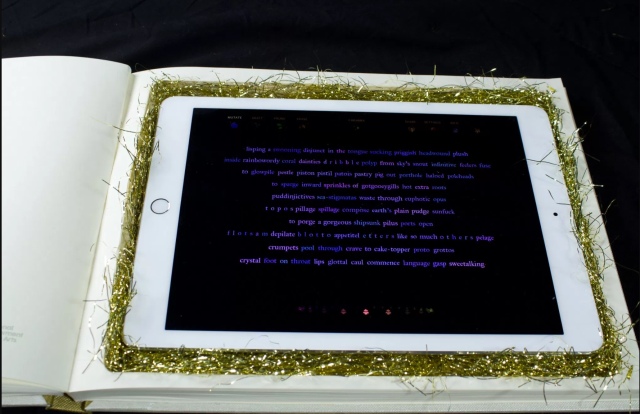

Readers can begin to interact with the iPad, on which the book’s text is mutating on its own.

Courtesy of the artists.

At the end of the book, the iPad is revealed, and the reader can make Abra their own using the menu at the top of the screen to “Mutate,” “Erase,” “Graft,” “Prune,” and cast an unpredictable “Cadabra” spell.

Courtesy of the artists.

With its poems mutating on the iPad screen, Abra challenges the play with boundedness beyond the effect Drucker explained when describing Between Page and Screen in 2012. In its digital challenge to boundedness, Abra has much in common with Visual Editions’ reimagining of Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1 in an app format. The original work was published by Le Seuil in 1962 and translated by Richard Howard for Simon & Schuster the next year.

Marc Saporta

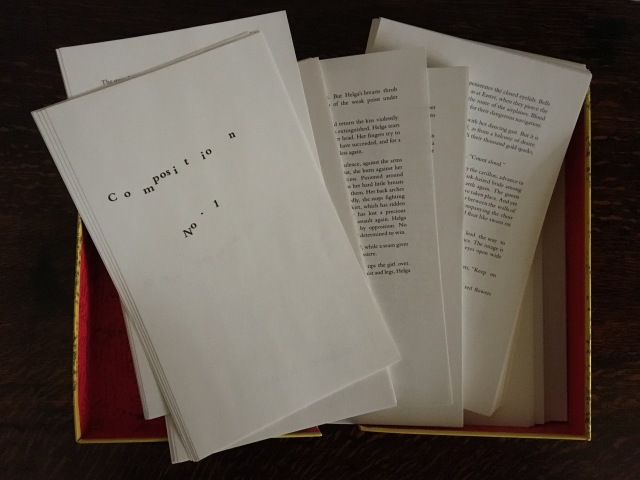

Composition No. 1

Translated by Richard Howard

Redesigned and reissued by Visual Editions (2011). Photo: Books On Books Collection.

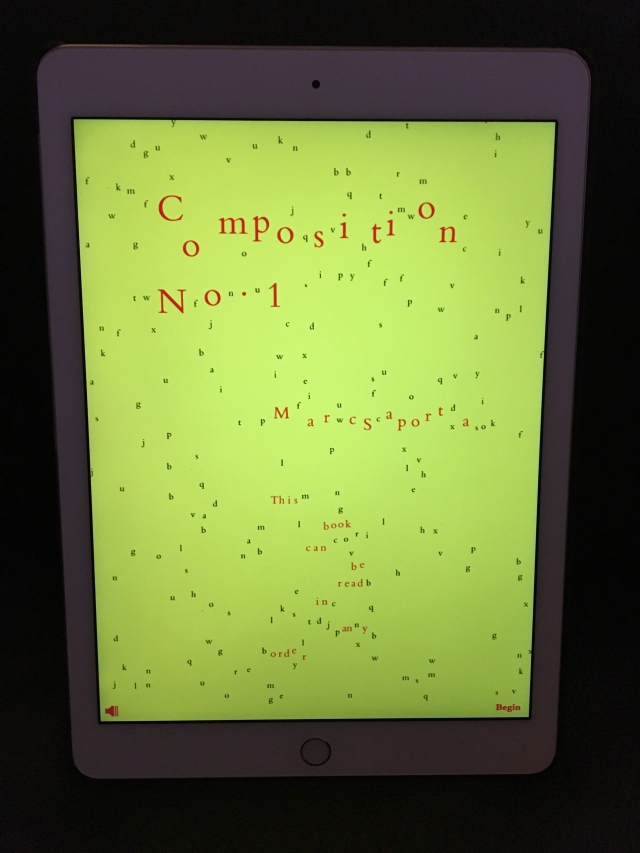

Composition No. 1 (the app)

Marc Saporta, Composition No. 1

Diagrams by Salvador Plascencia, Designed by Universal Everything (2011). Photo: Books On Books Collection.

Introduction by T.L. Uglow, Google Creative Lab and YouTube (2011). Photo: Books On Books Collection.

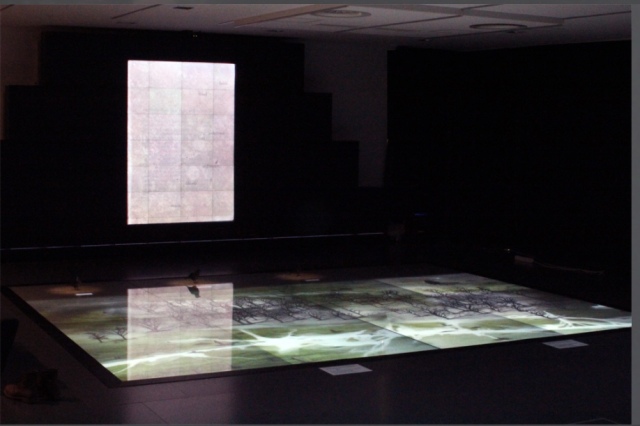

The unboundedness of Abra also has echoes in Field, the book, visual art and installation all in one produced by Johannes Heldén about the same time as Abra and The Bellingham Review piece. Field‘s interactivity, however, relies on a floor touchscreen of 20 square meters, one effect of which is to remove words from pages projected on a screen and another to animate a series of sculptural mutations of the Eurasian Jackdaw. The ephemerality of an installation combined with the effective of personal interactivity intensifies the challenge and play of unboundedness.

Johannes Heldén

Field (2015)

Produced and premiered at HUMlab, Umeå University. Screenshot: Courtesy of the artist.

Which brings us full circle to the installation-inspired “Abra: The Kinetic Page” and the last aspect of Abra: The Living Text that carries it beyond the expectations of the “Expanded Artists’ Book”. The work began as a collaborative book-length poem between Borsuk and Durbin. Writing separately using a series of constraints, then weaving their words together and editing them side by side, the authors found a new voice emerging from the conjoined poem, that of ABRA herself. To give a body to that voice, they created a series of conjoined costumes, each an avatar reflecting various aspects of the poems.

Abra Woodnymph

Courtesy of the artists.

When I hear sad tales of “The End of Books“, I think of these artists and authors and the distances between them – Borsuk in Washington State, Durbin in southern California, Hatcher in New York, Hamilton in Ohio, Rabas and Woodall in Illinois and Heldén in Sweden. Then I look at the distance between my finger and screen, between my hand and the copy of Borsuk’s Between Page and Screen lying on the table here. Those sad tales fade before the palpable vibrancy of book art and the transformative effect of the digital.

Abra features in Anne Royston’s piece on the media-bending of book art today at the College Book Art Association’s site.

See also Borsuk’s “Books and Bodies“, Cuaderno Waldhuter, August 2020. Accessed 25 September 2020.

And finally, see Borsuk’s The Book (MIT Press, 2018).

Images of ABRA from Books On Books Collection (not including iPad app)