Marlene MacCallum achieves distinctive results by painting with photography and sculpting with book structure in her artist’s books. Her painting with photography has involved not only collage work but pinhole cameras, digital cameras, digital layering and masking as well as a variety of transfer processes — digital and analogue photogravure, lithography, digital pigment printing, and digital inkjet printing. Sculpting with book structure mainly includes varying the binding as in the accordion with fold-out of Obvert (1997), the tunnel book structure of Do Not Enter (1998), the gatefold of Domestic Arcana (1999), the tile format fold-outs of pink story (2004-05), the accordion of Quadrifid (2009), the dos-à-dos of Glaze: Reveal and Veiled (2013), and the Miura fold of Rise (2020). It also includes altering books as in Withdrawn (2010) and varying the substrate as in the lace paper, Moriki, double matte Mylar, Lanaquarelle, and embossed leather of Townsite House (2006) and the etched copperplate and Tyvek of Trompe l’Oreille (2011).

Across the four volumes of the Shadow Quartet, MacCallum reflects almost all of the variety of these works and demonstrates her special blend of painterly photography and sculptural book artistry. The word (or text) has also but not always played a part in MacCallum’s book art. Even this is captured in the Shadow Quartet, but perhaps in a poetic way that sets them apart. Another element that sets this quartet apart is music; it may appear subtly in the title of Theme and Permutation (2012), but in the Shadow Quartet, it makes its presence known in the title, images, structure, and words.

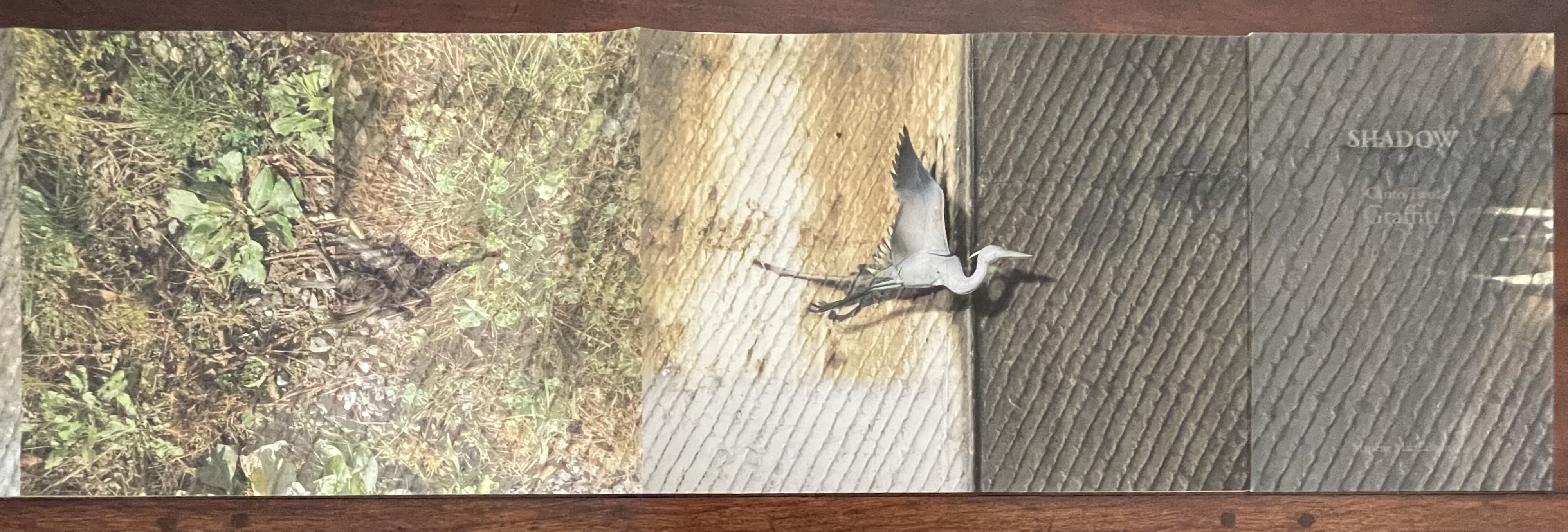

Shadow

Canto One: Still Life (2018)

I was the shadow of the waxwing slain

By the false azure in the windowpane;

I was the smudge of ashen fluff – and I

Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

— Pale Fire, Canto One, 1-4

Shadow

Canto One: Still Life (2018)

Marlene MacCallum

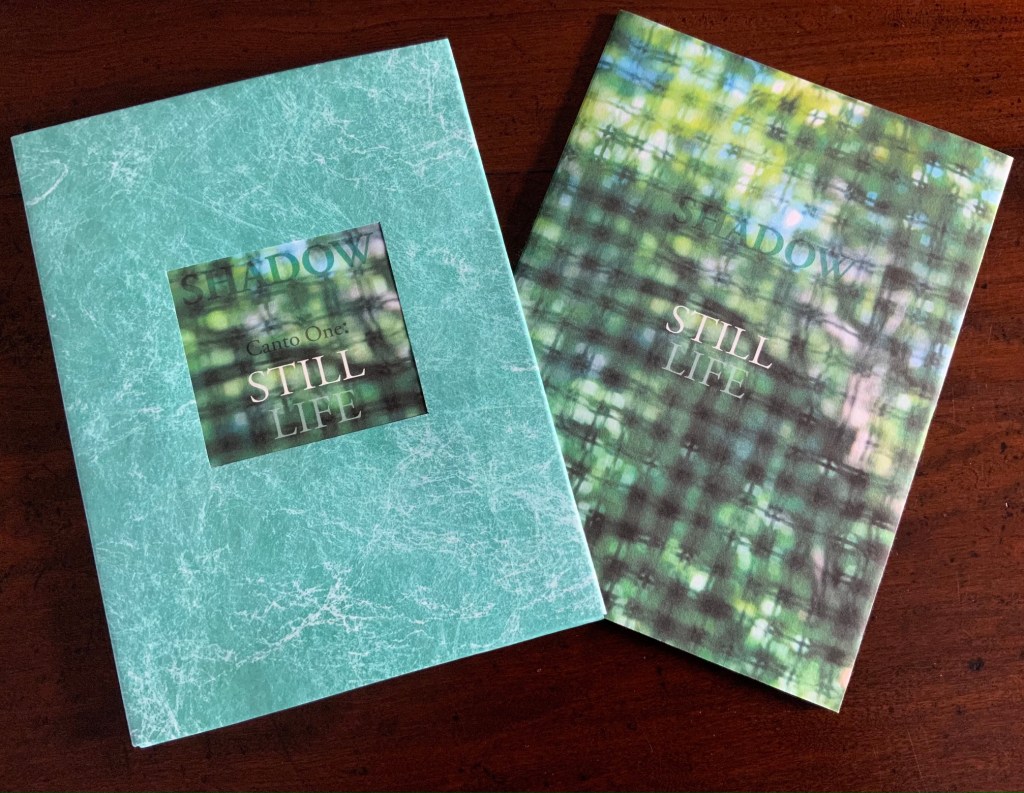

Handbound artist’s book with slipcase, pamphlet binding with gatefold structure, digital pigment print on Aya. H237 × 175 × 10 mm (closed dimensions). Edition of 15, of which this is #3. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

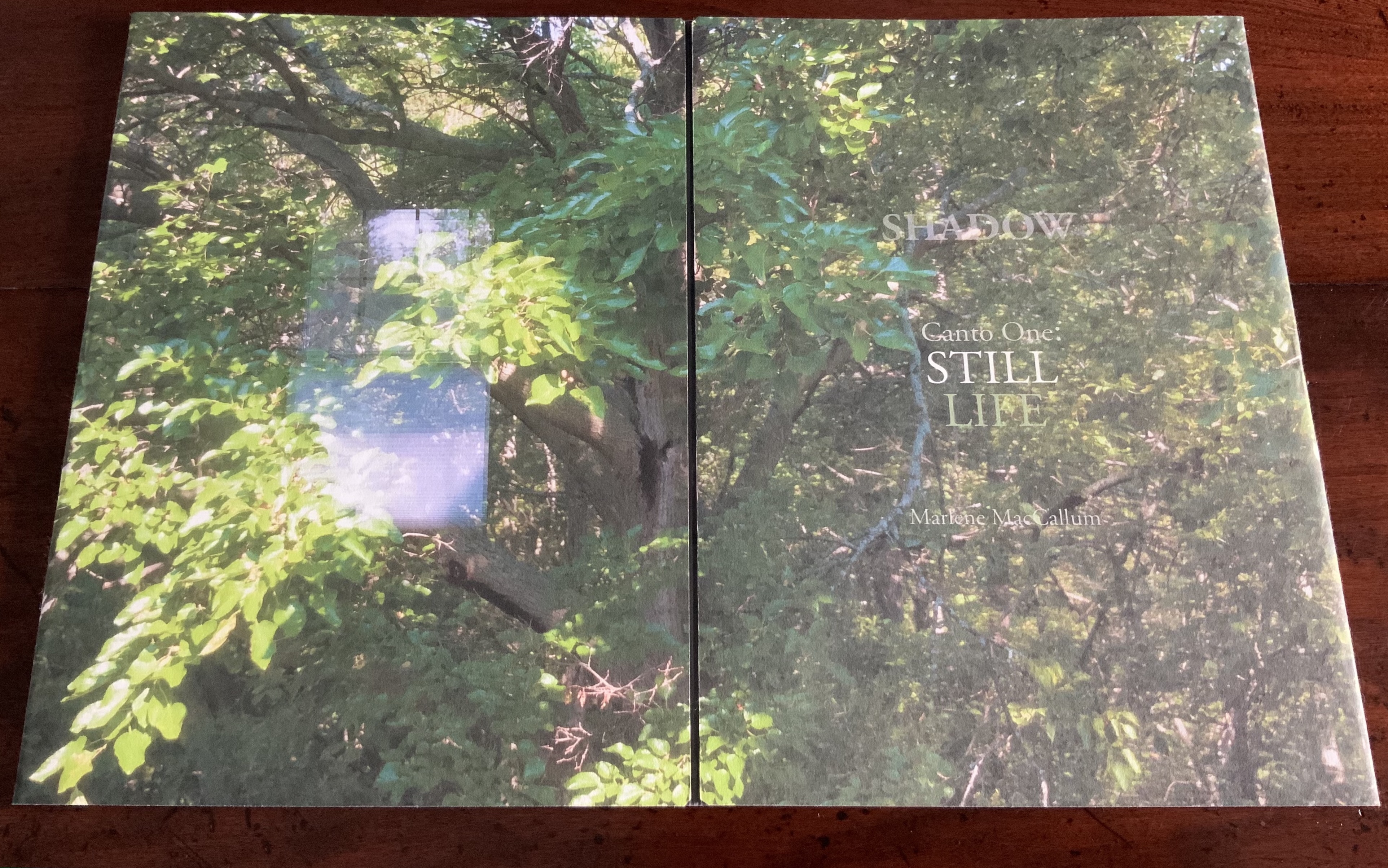

Canto One: Still Life had its inception at a window in the bare room of a house into which Marlene MacCallum and David Morrish were moving. According to the artist, it was, in fact, a dual inception: the death of a cedar waxwing at that window over her desk and her recollection of those opening lines above from the long poem at the heart of Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire (1962). Throughout, there are so many allusions to Pale Fire‘s images, metaphors, and its workings that you might be tempted to think of it as a frame or some sort of biblical source. But no. The frame and source are that bird, that window, that room, shadow and light, surface and reflection, interior and exterior, folding and unfolding, the book — and music.

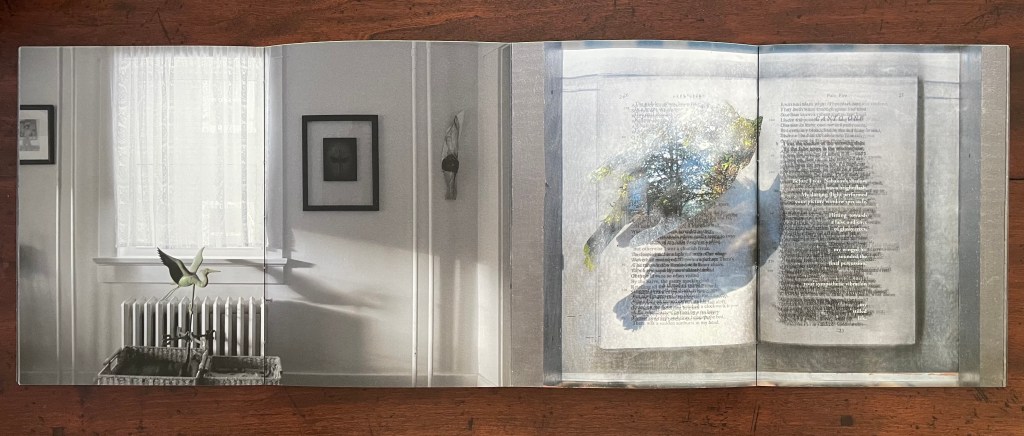

Pull the book from it slipcase and open it to the first spread of its gatefold structure of two pamphlet-sewn booklets, fore-edge to fore-edge. On the left, the reflection of a window hangs in the light and shade of the trees. On the right, the work’s full title, also hanging in the light and shade of the trees.

First spread of the book’s gatefold. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

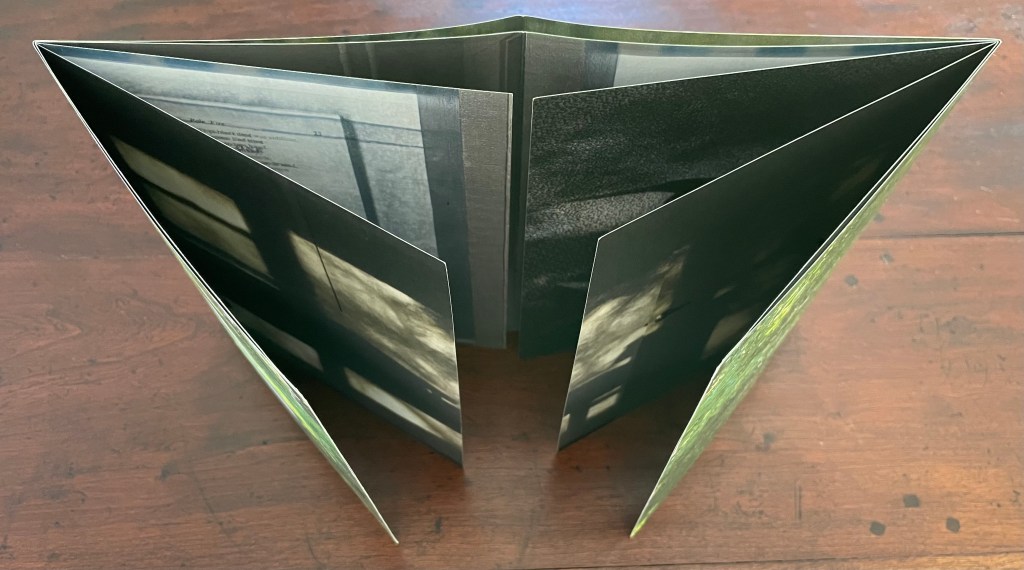

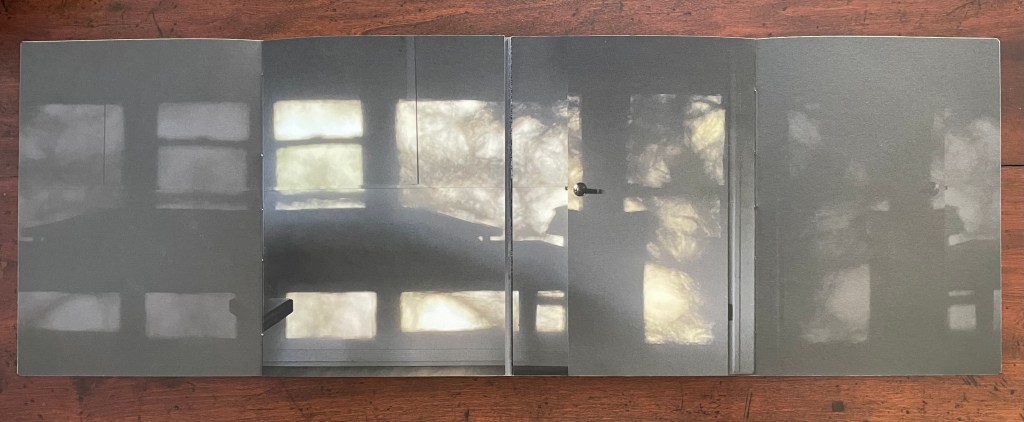

When the verso cover page turns left and the recto cover turns right, the center panels of the resulting four-page spread display a camera obscura-like projection against the back wall and opened door of the artist’s room. Unlike a camera obscura image, however, the image is right side up. In a sense, the back wall and door are a mirror in which the window and outside world are shown. What we are seeing is a layered set of digital photographs. One image is the room’s backwall and door. This image has been created by the setting sun shining in through the window projecting the shadow of the trees and window frame onto a wall. The table is between the window and the wall, so we see its shadow as well. Thus, we see the silhouette/shadow of tree branches and leaves, table top and the architecture of the window frame. Another is taken from the edge of the artist’s desk capturing the desk’s surface reflection of the window and trees outside. Naturally the image of the window and trees is blurred and shadowy, but layered on top of the back wall, it seems to be both its own reflection and its own shadow. The two wings of the four-page spread echo this paradoxical equation of reflection with shadow. The far left panel mirrors/shadows the panel to its right. The far right panel mirrors/shadows the panel to its left.

Elsewhere, MacCallum has referred to windows as apertures and barriers in a house (MacCallum, 2007, p. 54). In Still Life, that dual metaphor comes to life with the cedar waxwing’s death at the window and the digital camera’s record of a room that has become a camera chamber, filled with tree shadows and window forms. What also comes to life is the mysterious effect this dual metaphor has on the age-old philosophical conundrum of reality vs appearance. As a version of Plato’s cave, MacCallum’s camera chamber adds the twist of directing our attention and perception to the fully in-focus corner of a book on the desk and a gleaming door handle. The “reality” of the door handle asserts the reality of the background status of the wall and door, but the sharply focused book corner in the foreground calls that into question. Imagine one of Plato’s captives piping up to say, “But that’s a real bat crawling on the cave wall amongst those projections!”

First four-page spread. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

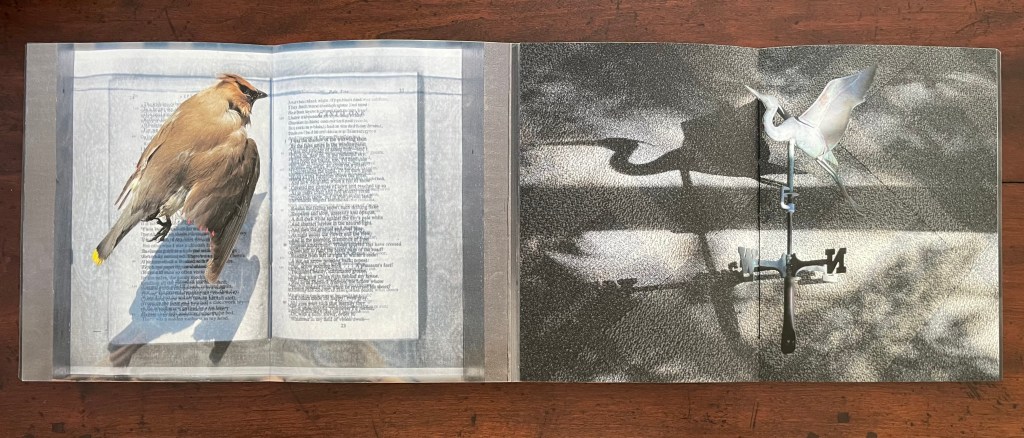

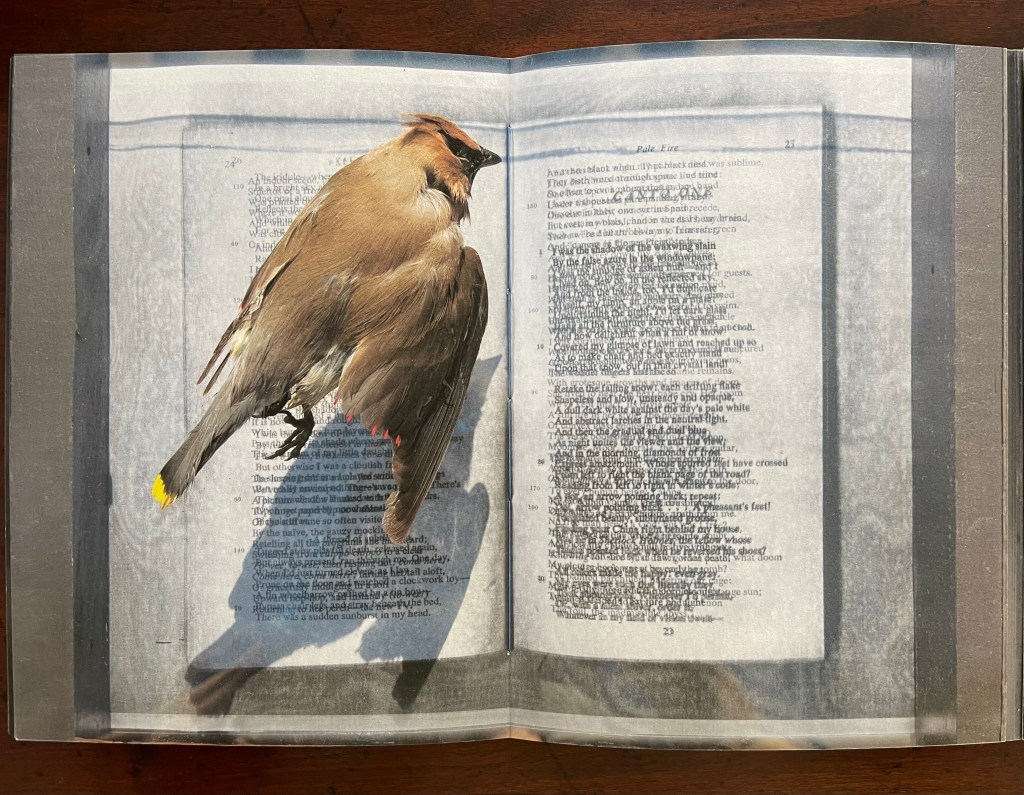

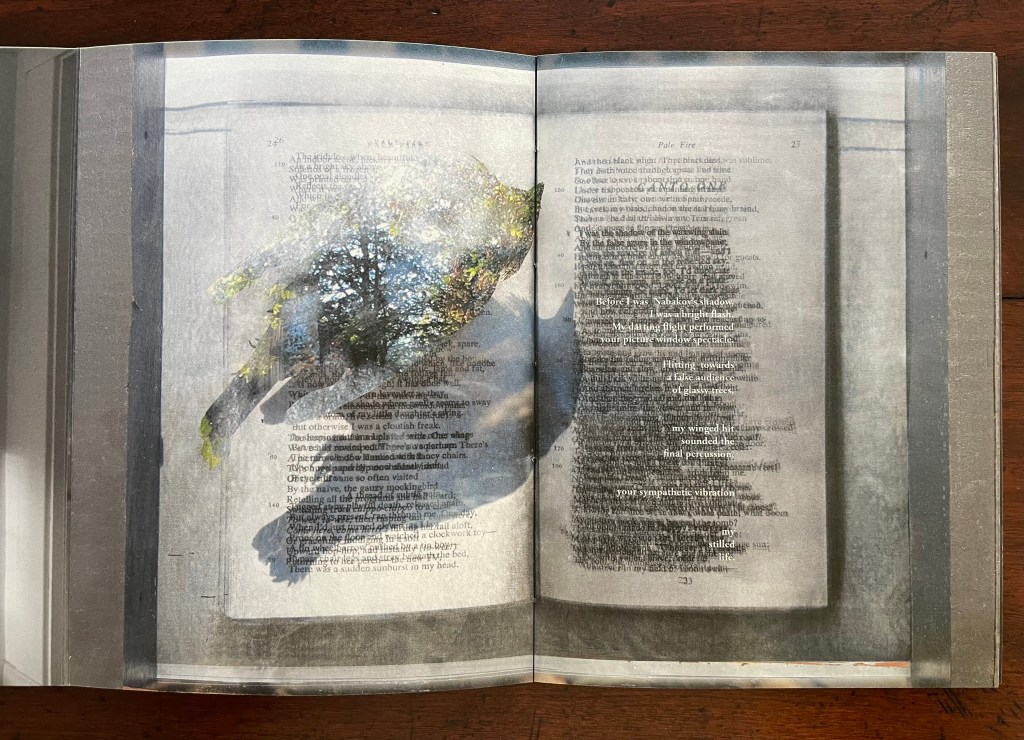

The turning of the two center pages reveals two double-page spreads, the still life cedar waxwing hovering over its shadow on the left and a heron weathervane hovering over its shadow on the right. Just as the shadowy mirrored window view contains the green of the outside world, the waxwing’s shadow strangely reflects the color of the dead bird’s feathers. Shadow appropriates/reflects bird. Likewise, MacCallum’s gatefold structure appropriates/reflects Pale Fire with the blurred palimpsest view of the double-page spreads and their gutters aligned perfectly along the panels’ pamphlet-sewn fold.

The second four-panel spread.

Despite their inspirational importance, lines 1-4 of Pale Fire are barely legible in the palimpsest of pages from Pale Fire facing the waxwing and its shadow. Hardly any of the lines are legible in the palimpsest, which includes the pattern from the curtains that will hang at the window in the next spread. Perhaps this is a bit of distancing of the canto from Pale Fire. A reminder of the distance between shadow and reflection, the distance between art and reality, the distance between the appropriation and the appropriated?

Now look at the right-hand “double-page spread” that is structurally and metaphorically a shadowy reflection of the cedar waxwing spread. Like the dead bird, the heron weathervane hovers over and casts its shadow on the surface below (a background of carpet squares). Unlike the waxwing’s shadow, though, the weathervane’s shadow does not reflect the heron’s white and verdigris colors. A signal of distance between object and shadow? There are no waterbirds, weathervanes, or allusions to them in Nabokov’s novel . So, another form of distancing the canto from Pale Fire, a distancing of the appropriation from the appropriated?

That distancing is a good thing. Pale Fire (1962) is a strange book. The 999-line four-canto poem entitled “Pale Fire” at the heart of Nabokov’s book comes in heroic couplets from the fictitious John Shade, an authority on Alexander Pope. Or rather it is presented to us framed by a foreword and commentary by Charles Kinbote, Shade’s purportedly fellow academic who spies on him at all hours, who is really the fictitious deposed king of the fictitious kingdom of Zembla, and who thinks he has slyly persuaded Shade to incorporate his Zemblan tragedy in this poem before a dispatched assassin arrives to dispatch the exiled king but misses and dispatches Shade instead. There are windows, shadows, reflections, recursive footnoting, self-reflexive puns, and easter eggs aplenty, so much so as to have launched dozens of expositions — even a comparison with digital game design. Too close a mapping, appropriation, or sourcing or allusiveness would overwhelm MacCallum’s effort.

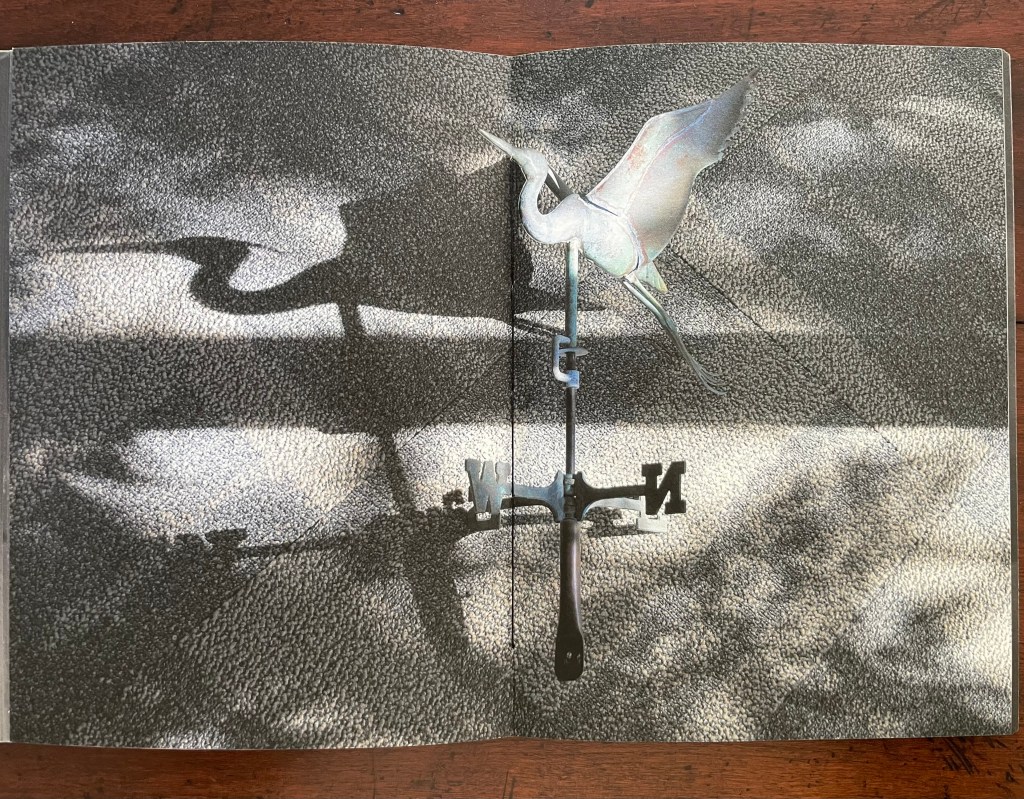

In Still Life‘s next set of double-page spreads, the birds switch position. On the left, we have a decorated room with wall hangings and curtains in contrast with the bare room of the first four-panel spread, and the weathervane now waits to be carried away in a wicker basket. A straightforward photograph of a straightforward interior. It pairs, however, with a surreal manipulation of the waxwing’s corpse, now become a window on the windowed reflection it struck. The palimpsest beneath is the same, but overwritten on its illegible text is MacCallum’s poem in the voice of the waxwing before it was “Nabokov’s shadow”. These four panels — and in particular the double-page spread on the right — spell out Pale Fire‘s role in the canto.

MacCallum has more than appropriated Pale Fire‘s waxwing and the book’s themes of art’s recursive, self-reflexive effort to engage the exterior world, to capture the line between the real and the fictive, between self and other, and between life and death. With her gatefold structure and photographic techniques, MacCallum dives through the rhetorical devices. From the beginning — from the left and the right — structure and the visual precede verbal metaphor. The verbal metaphor is last out of the gatefold, and when it comes, it comes from before Nabokov’s words, voices, and images. It’s no accident that the reflective corpse and its shadow cross and dominate the gutter of the palimpsest’s image. Their surreality adds a reality to the waxwing’s white-on-black voice that speaks of life before either book and now of life stilled in the artist’s book.

The gatefold structure and MacCallum’s precision of alignment allow the reader/viewer to participate in the material play with metaphors by combining different spreads. Here is one particular combination that underscores the role of the waxwing in Still Life.

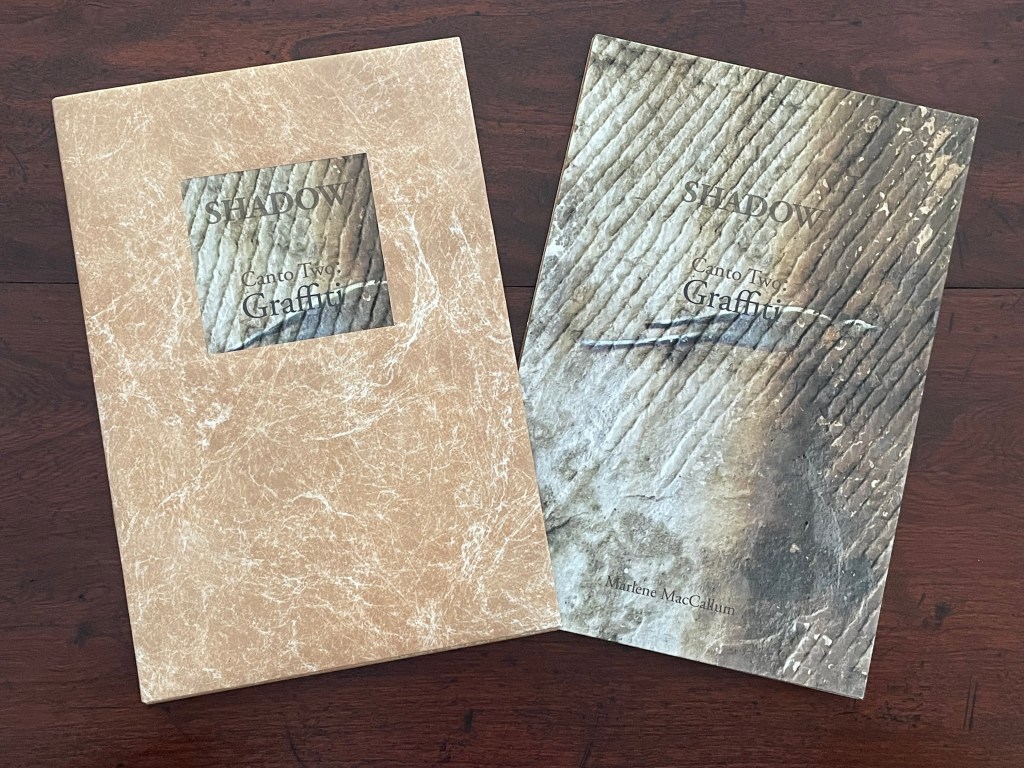

Shadow

Canto Two: Graffiti (2018)

Shadow

Canto Two: Graffiti (2018)

Marlene MacCallum

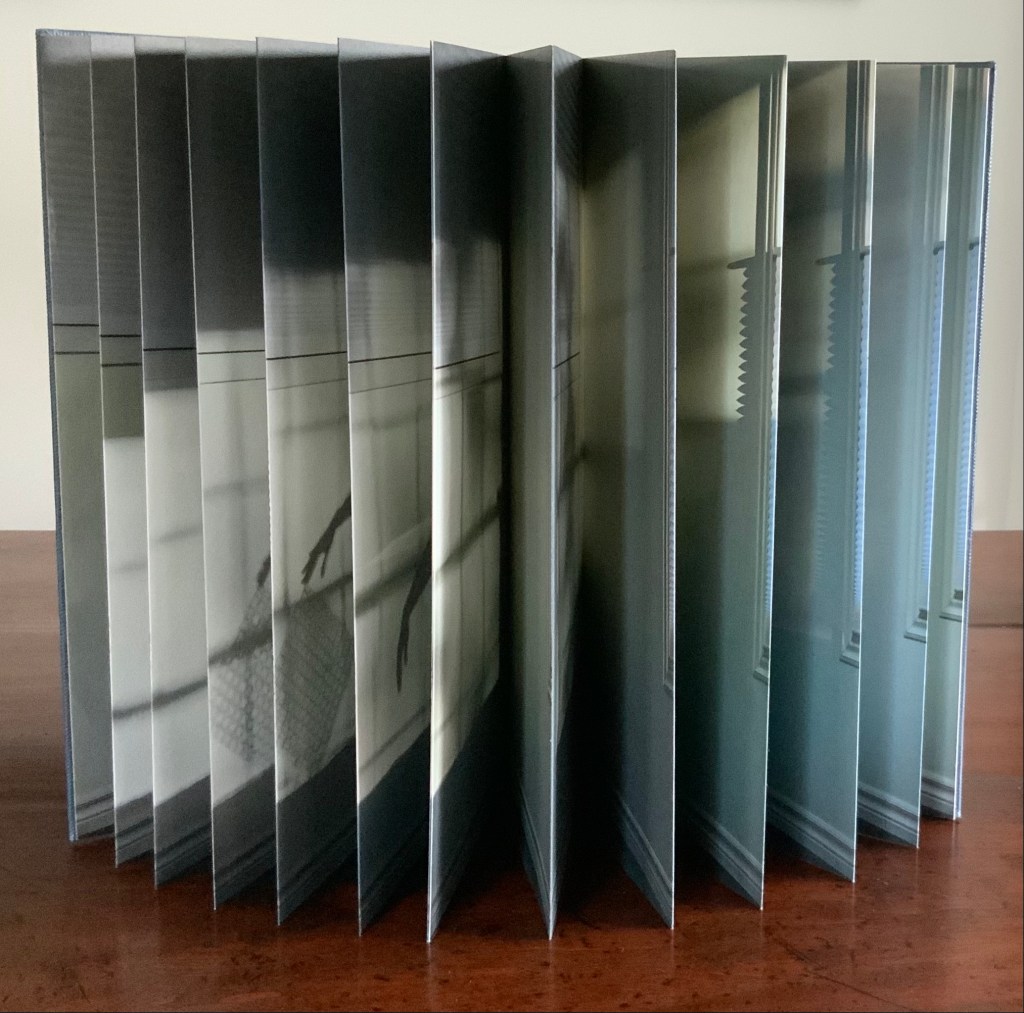

Hand bound artist’s book with slipcase, accordion binding with hard covers, digital pigment print on Aya (bird images) and Niyodo (music images), slipcase constructed of stained Tyvek wrapped around eterno boards, H237 × W160 × D14 mm (closed). 10 panels each side. Edition of 15, of which this is #3. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

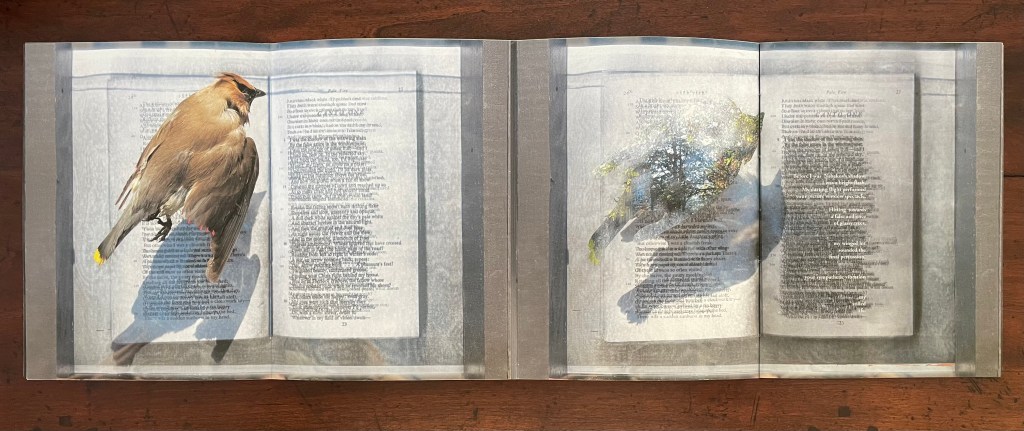

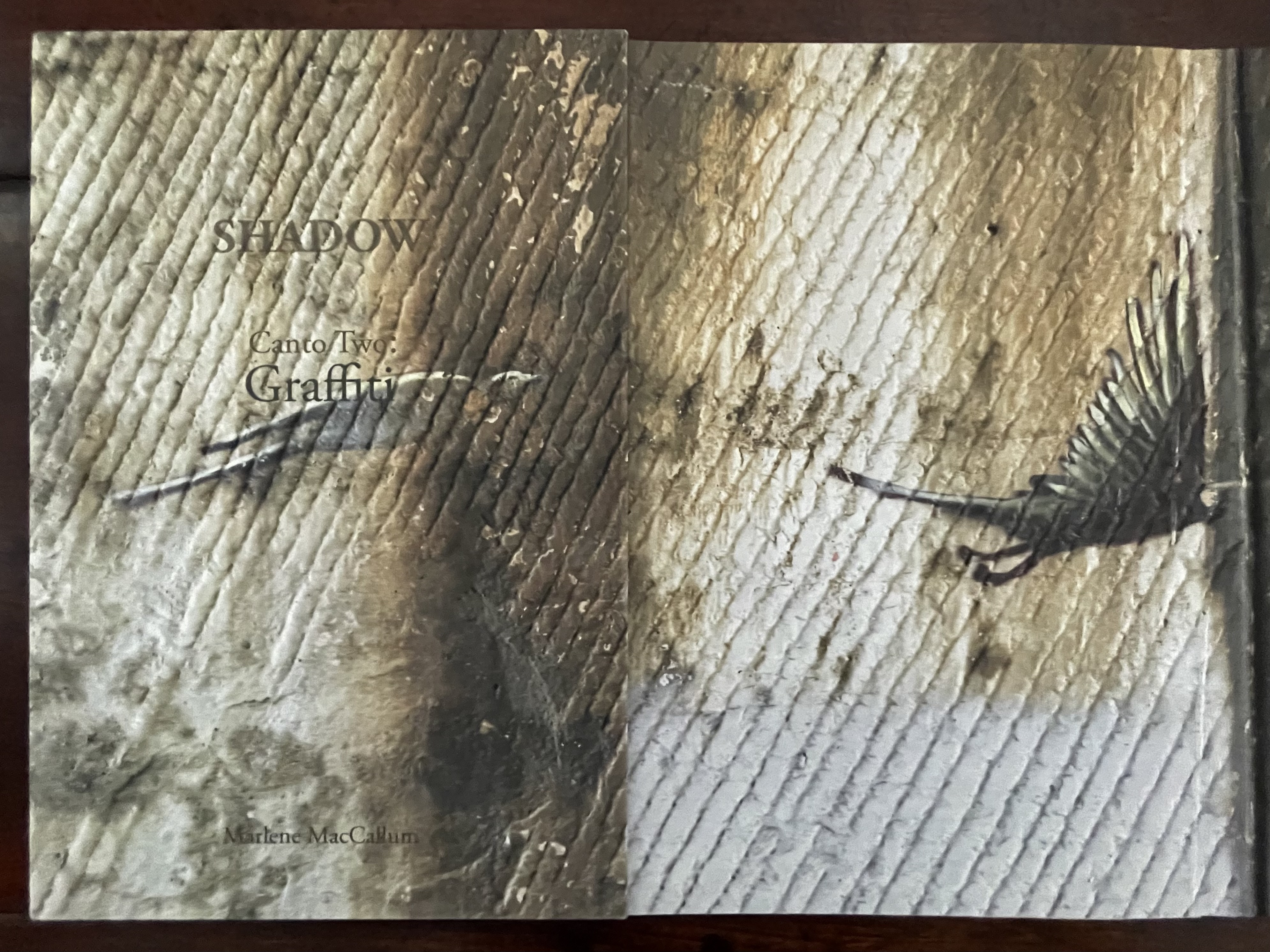

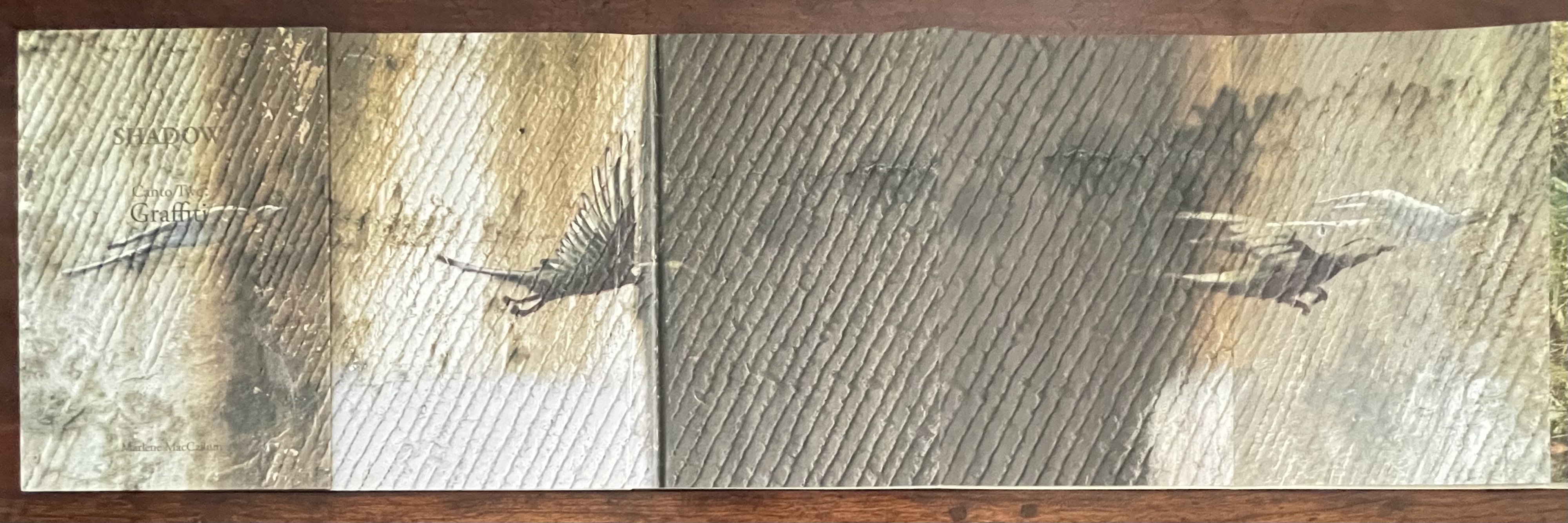

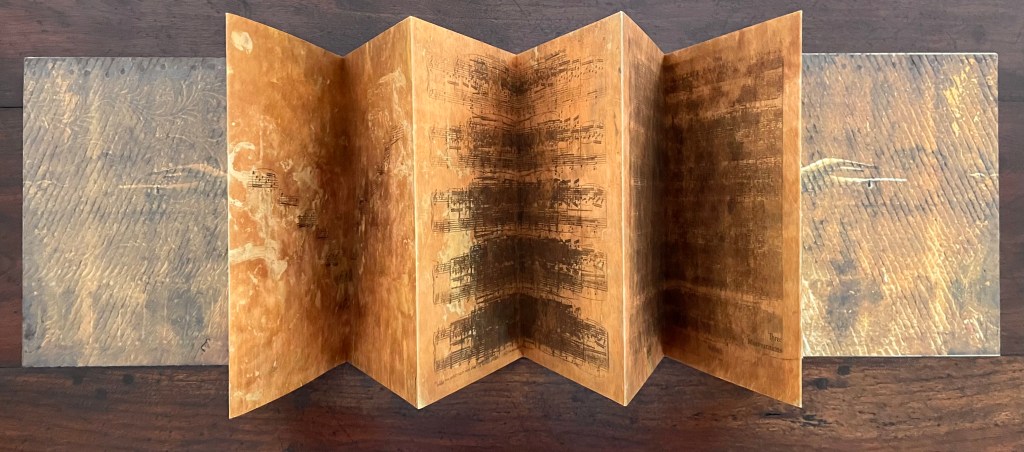

While Canto Two: Graffiti echoes the bird imagery, found objects, and palimpsest technique of Canto One, it works with a different structure and adds a new source of allusions. Canto Two is a double-sided accordion made with two different papers — Aya and Niyodo.

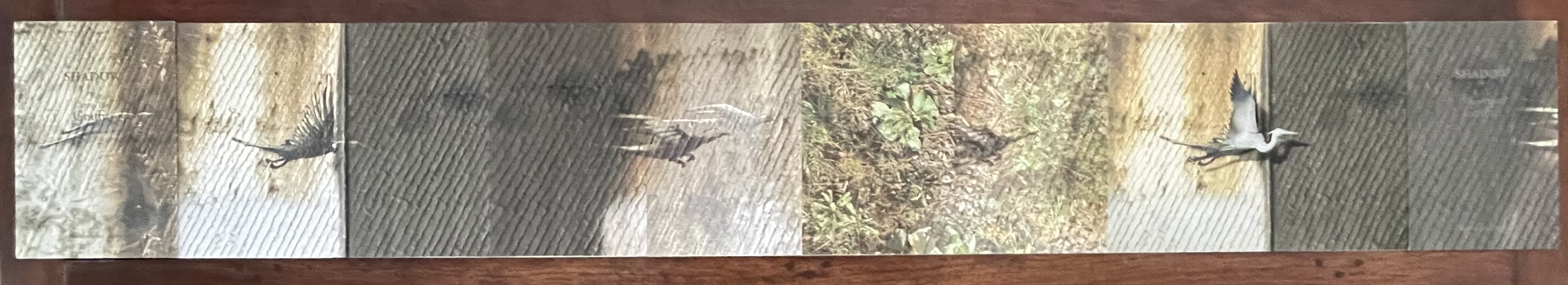

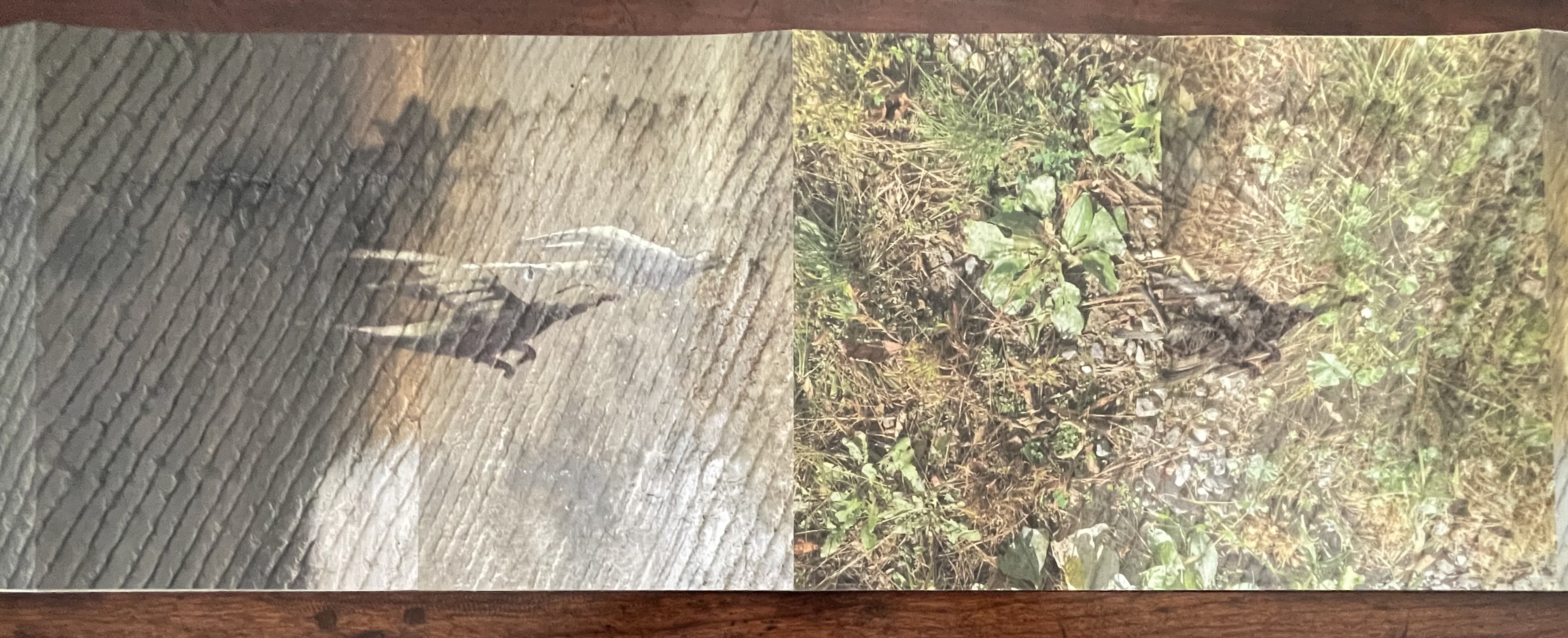

On the Aya side, MacCallum has appropriated a found image of birds in flight graffitied against the walls of an underpass, layered it with images of actual birds, and transformed the background of the concrete walls into a weed patch then back again. The effect is almost animated. The birds simultaneously appear embedded in the wall yet above its surface, to fly into yet through the second fold, to metamorphose from one breed to another, to dissolve into bones and feathers on the weed patch, to fly over the next to last fold, and to exit the last panel’s edge. Like recurring musical motifs, the flight into the second fold and the segue from textured concrete wall to the weed patch with bones echo the cedar waxwing’s collision and death at the windowpane in Canto One, and Canto Two‘s heron flying over the penultimate fold seems taken directly from the weathervane in Canto One.

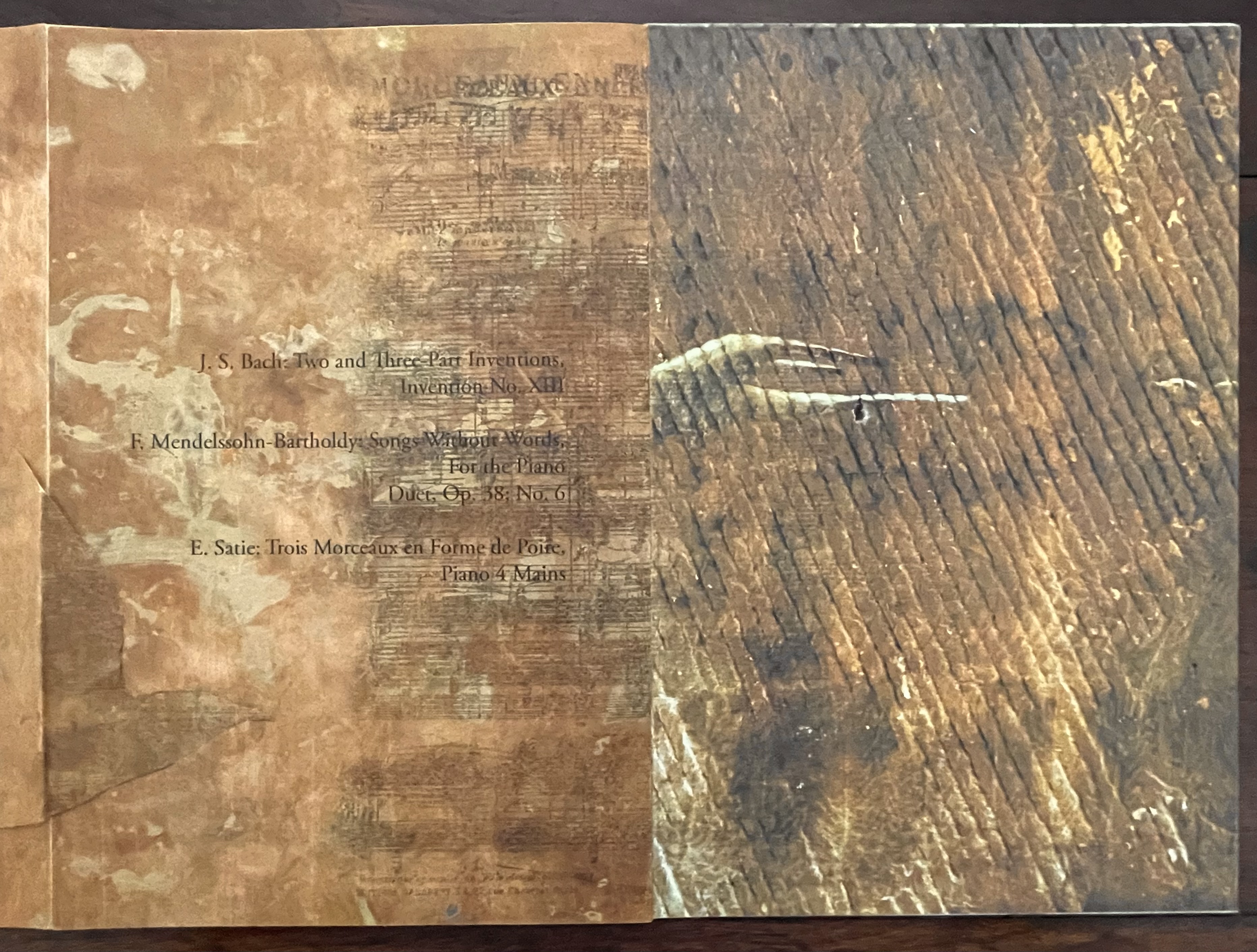

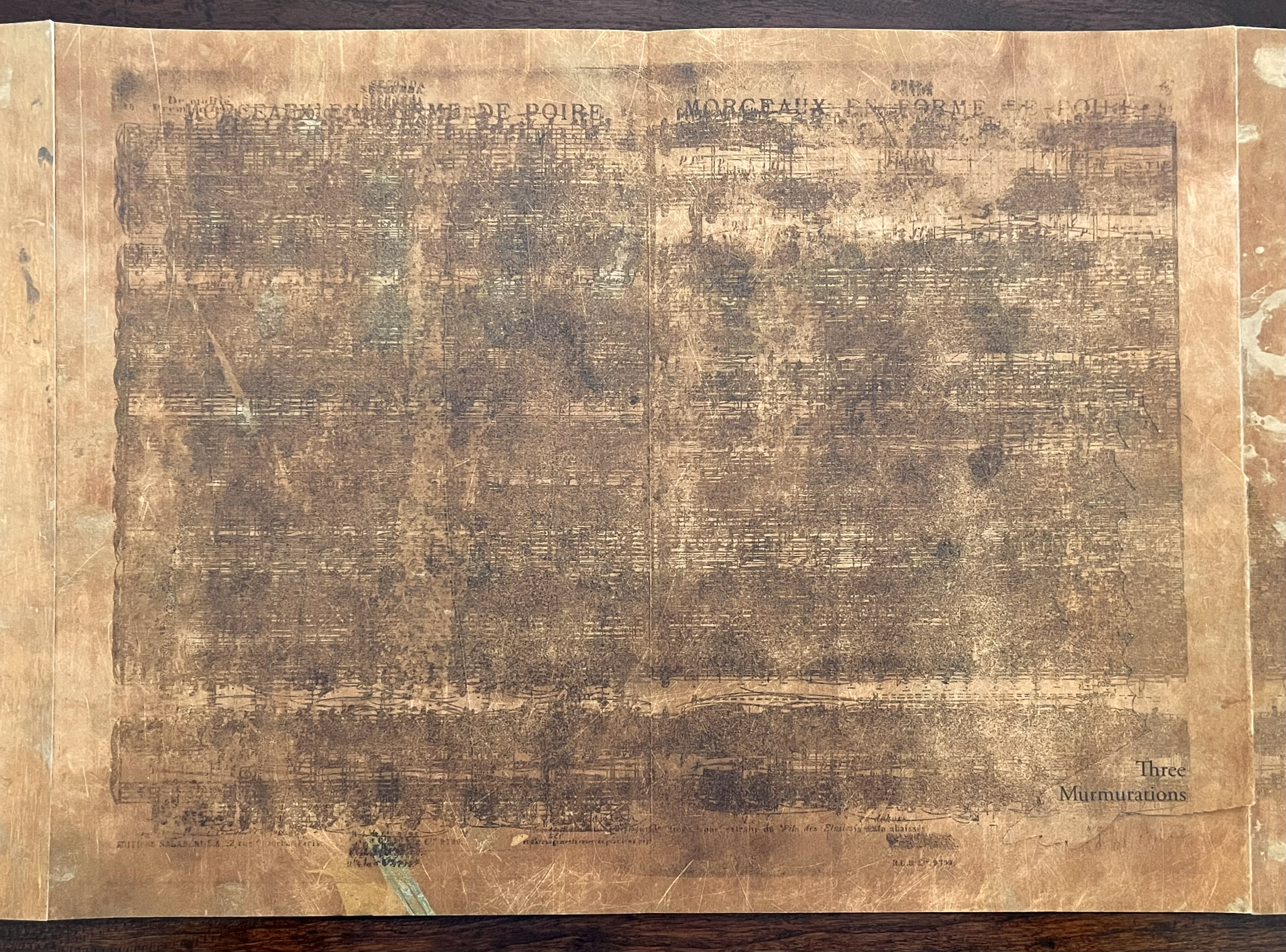

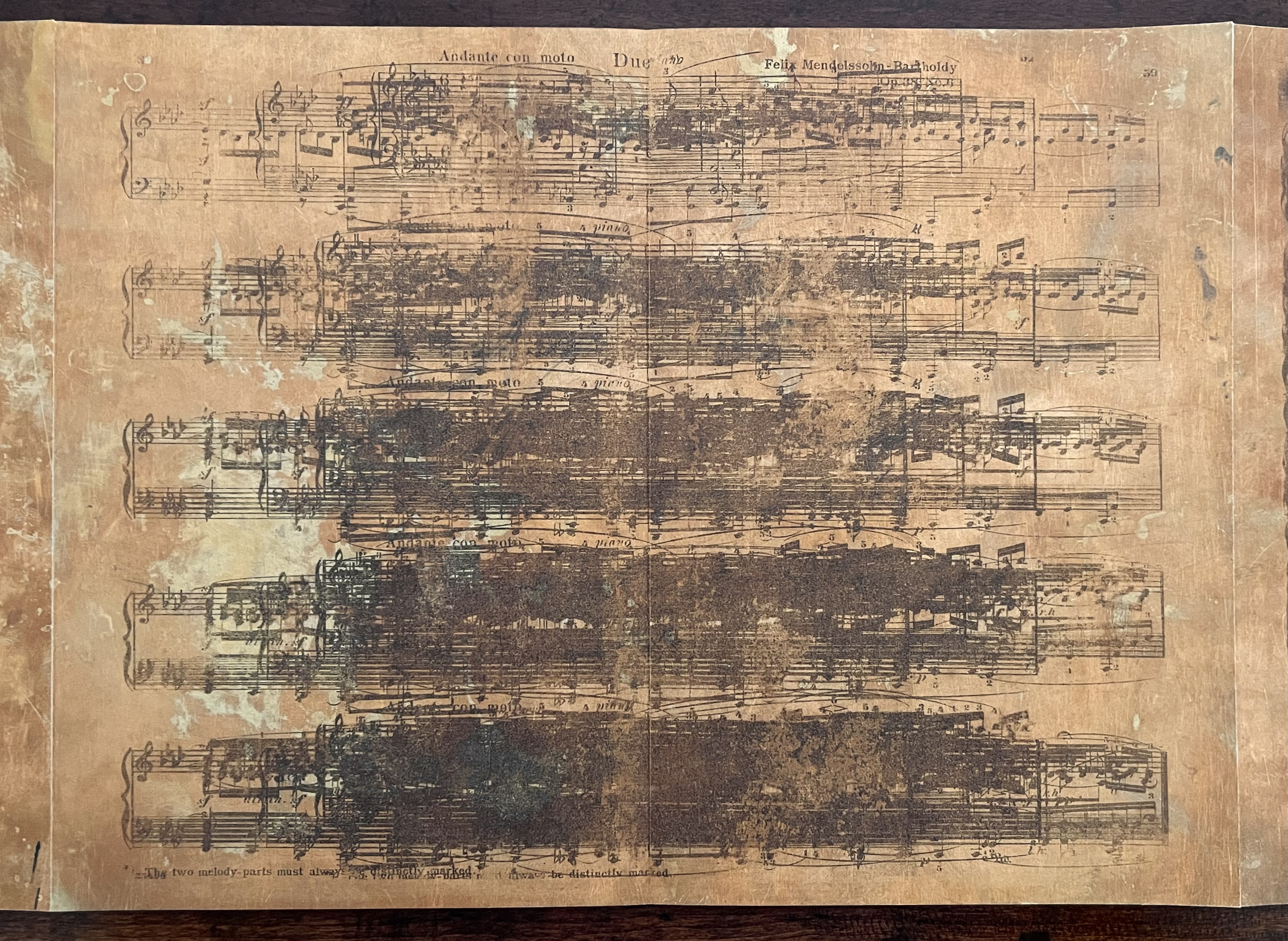

On the Niyodo side, MacCallum brings the musical metaphor to the surface. She has scanned the sheet music for J.S. Bach’s Two and Three Part Inventions, Invention No. XIII in A Minor, Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s “Song Without Words,” Op. 38, No. 6 (“Duetto” in A-flat major), and Erik Satie’s “Three Pear-shaped Morcels“, then condensed and layered them in the palimpsest manner applied to page spreads from Pale Fire in Canto One. The resulting image has been printed out and transferred onto copper. Each musical work has an element of duality that echoes Canto One‘s pairings of art and nature, the real and the fictive, self and other, and life and death.

The Niyodo-side seems to encourage reading from left to right and right to left. The birds on the outer panels are inward-bound, like the left and right hands would be on the keyboard in certain passages from the Bach, Mendelssohn, and Satie pieces.

Inward-bound birds on the outer panels.

Like the Aya side, the Niyodo side makes indirect as well as direct references to Canto One. The Niyodo side’s layering of the musical notation indirectly refers to the layering of Pale Fire in Canto One and directly refers to Canto One by including its curtain pattern in the layering on the outer panels, more easily seen immediately below and farther down.

The first two right-hand panels: The inner panel listing the music pieces. The outer panel with its layering of Canto One curtains and Aya-side concrete walls.

In these two panels at the far right of the Niyodo side, MacCallum further deepens this musical weaving or fusion of themes with a subtle piece of collage work. Notice the collaged bird in the left panel above. Below, this same bird almost disappears in perfect alignment with the palimpsest musical notation in the lower right-hand corner, but not before its tail feathers serve the purpose of labeling the named musical pieces as “Three Murmurations”, equating the birds in flight with notes in the air.

Bach, Mendelssohn, and Satie: sources of the “Three Murmurations” (see lower right-hand corner).

On the far left of the Niyodo side, the inward-bound birds seem to fly from the outer panel into a cloud of transformation in the adjacent panel. Within the cloud, musical staves begin to emerge.

The first two left-hand panels. The outer panel with its inward-bound birds and layering of Canto One curtain pattern and Aya-side concrete walls. The adjacent panel with musical staves emerging.

In the next two panels, we have musical notes on the wing presented in a shape that suggests a murmuration or the profile of a single bird. (This V-shape will appear again in Canto Four but in words.)

A murmuration? A musical profile of a single bird?

The Niyodo side’s two center panels now densely layer the musical notations to the point of blackness, which is where the birds on the outer panels and the music have been headed — into darkness and shadow.

The Niyodo side’s two center panels.

Like the difference in papers, the linearity of the Aya side and bidirectionality on the Niyodo side contribute satisfyingly to theme of duality in Still Life and Graffiti — and, as becomes evident, the entire suite of Shadow Quartet.

Shadow

Canto Three: Incidental Music (2019)

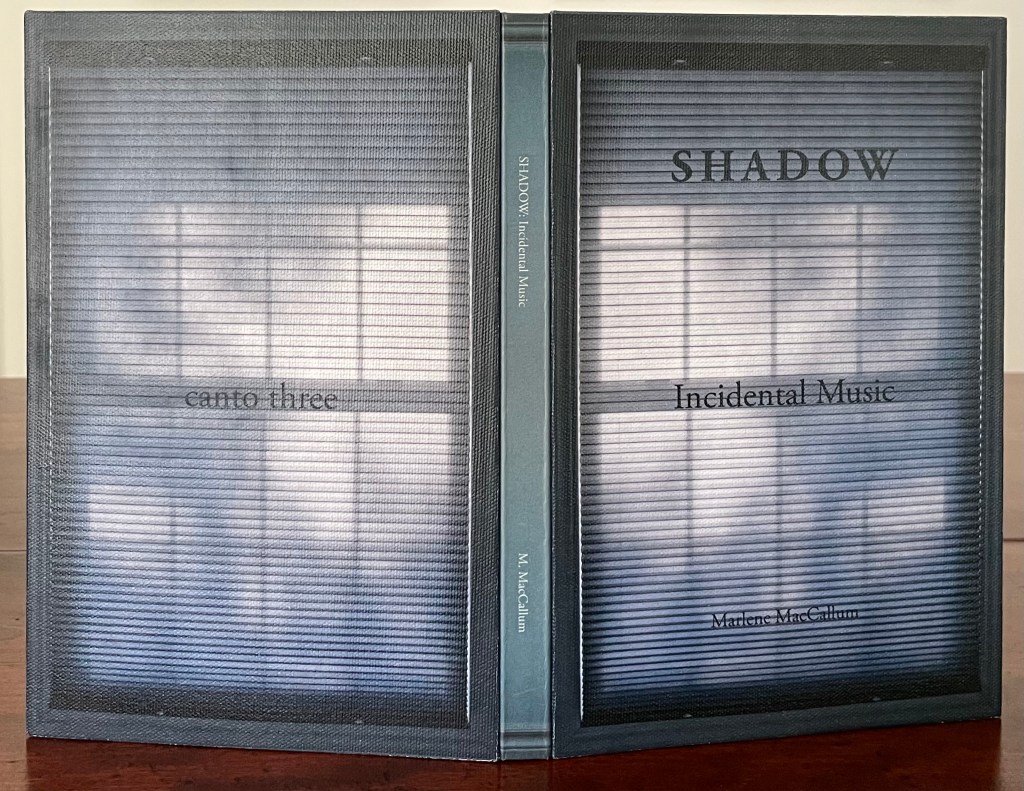

Shadow

Canto Three: Incidental Music (2019)

Marlene MacCallum

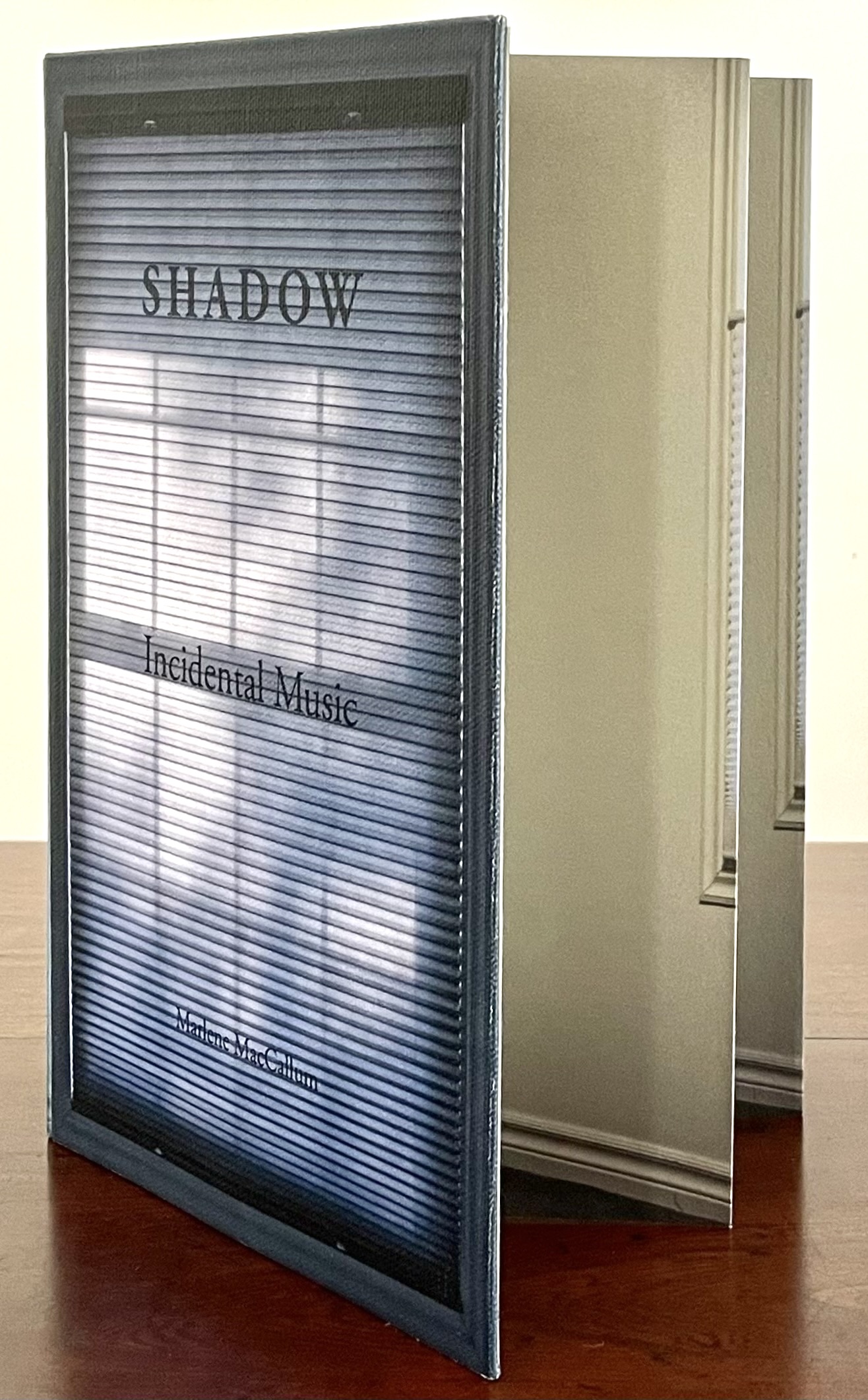

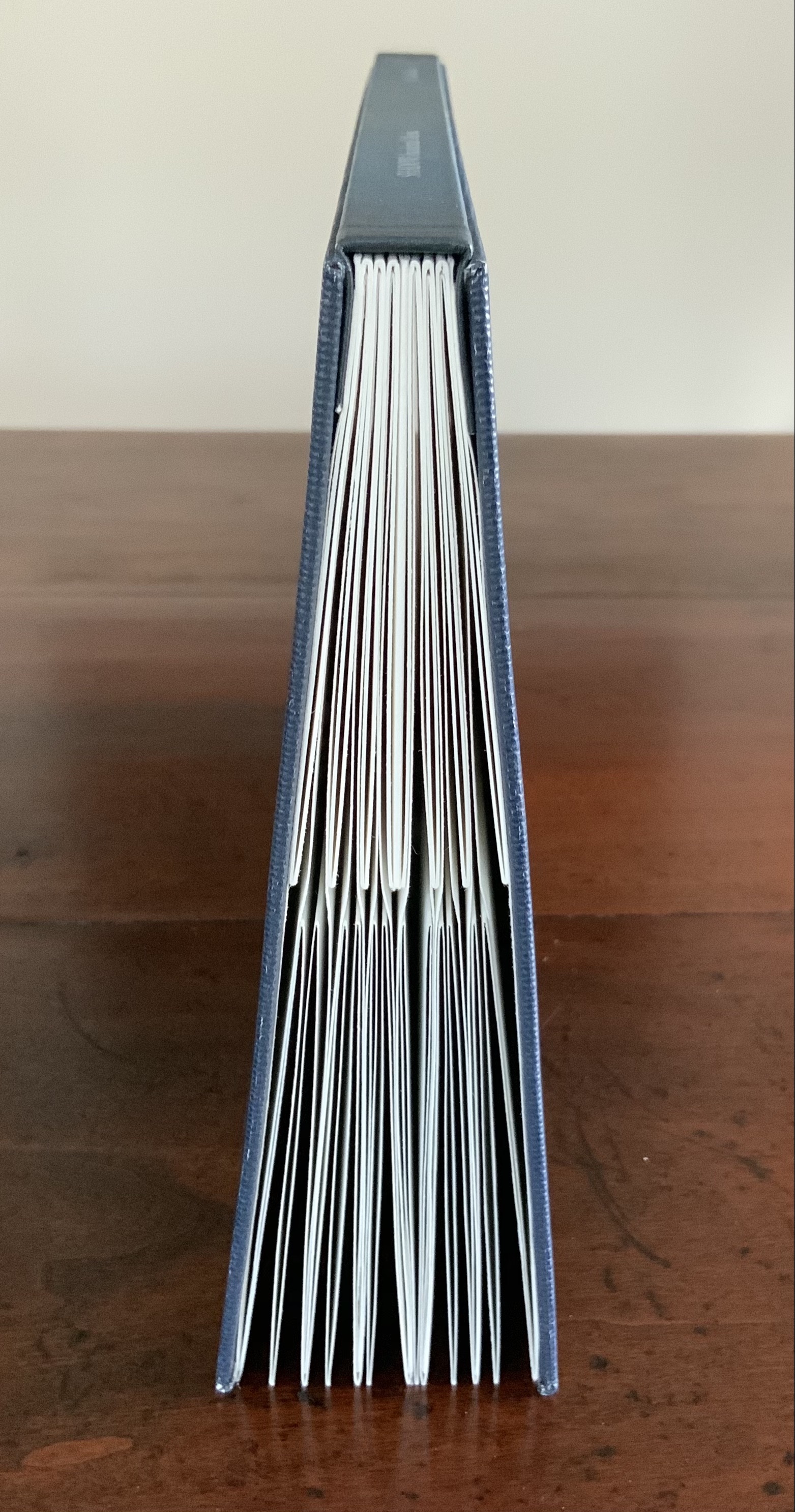

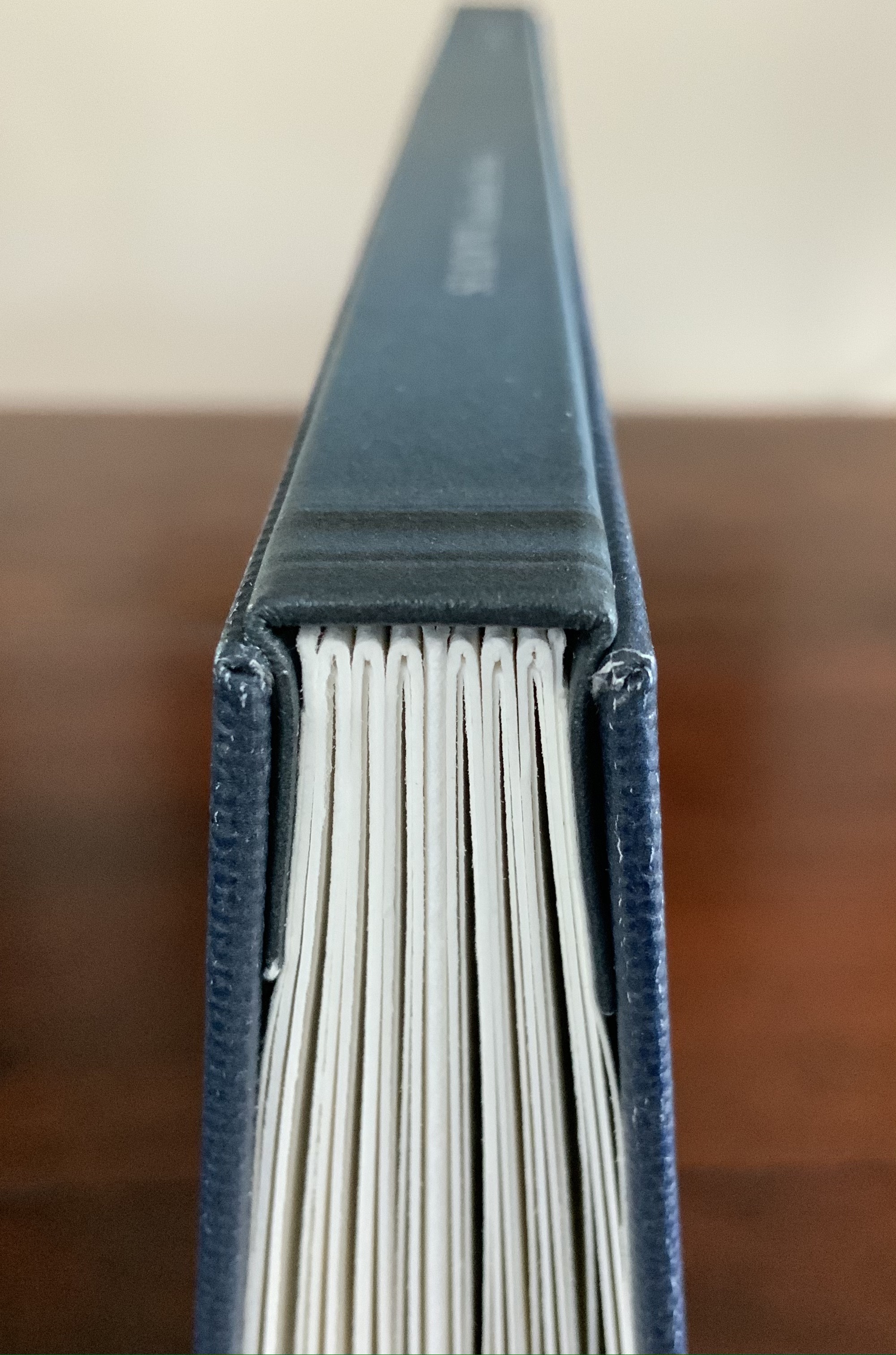

Hand bound book work with image accordion suspended over text accordion. Images are digital pigment prints on Digital Aya, hand-set letterpress poem and blind embossed soundscape letterpress. Case bound with digital pigment print covers. Dimensions: H237 × W159 × D11 mm (closed), H236 × W30o mm (page spread). Edition of 16, of which this is #3. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

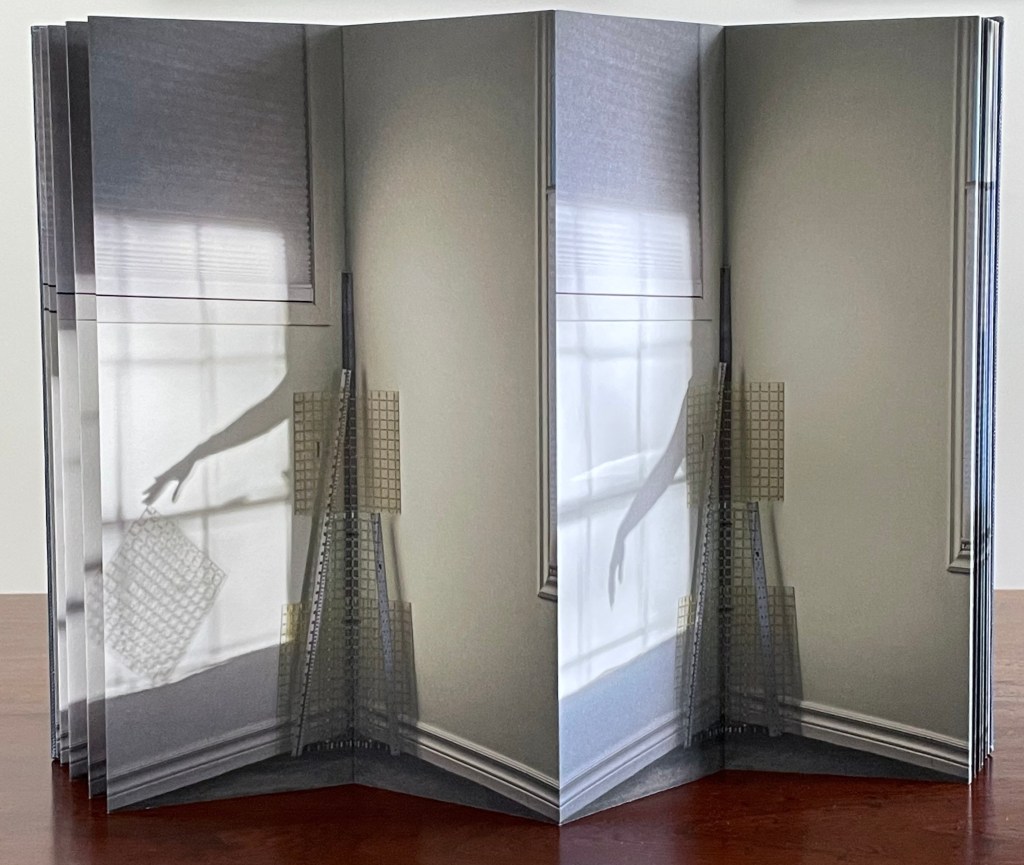

The way the images of birds, background, and musical notation dance with one another in Graffiti foreshadows another intricate dance in Canto Three. As with Still Life and Graffiti, the architecture of Incidental Music plays a critical role, perhaps even more so in its empowering of the work’s material elements and content. Standing the book upright and circling around it from left to right, we see the view of a room unfold. A window’s shadow and light cast into the room recall the opening of Still Life and MacCallum’s metaphor of windows as the apertures of a house. Through the aperture of this window, the light throws the window’s shadow, the shadow of an arm and hand, and the shadow of a quilter’s grid being balanced on its tip by the human figure. The objects leaning precariously in the corner are three quilter’s grids (two square ones, top and bottom, and one long vertical one) and three rulers of varying lengths acting as tripod supports. These measuring devices rest on top of and against one another and the wall. As we move around and to the right, the human shadow disappears, and all the images curve upwards and to the right.

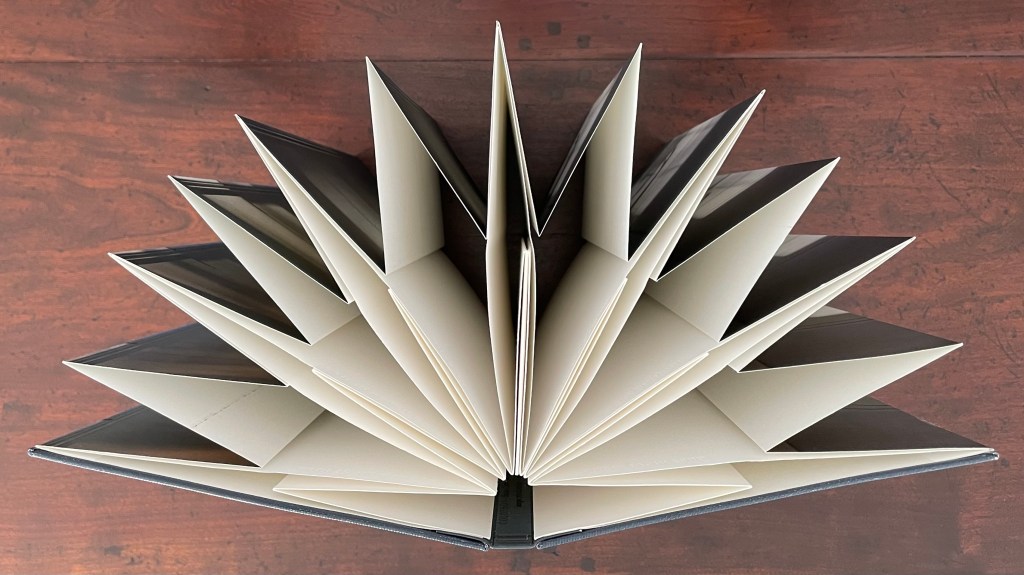

Viewing the book from above, we can see partially how the internal structure achieves this effect. The fore edges of the folios are folds, but their loose ends do not attach to the spine as would be expected in wrapped back binding.

There are in fact two long accordion-fold folios at play, one layered over the other. The outer folio carries the images of the window, the room’s interior, and the human shadow. Its left edge attaches as a pastedown to the front cover. The inner accordion-fold folio’s left edge is turned under and attached to the pastedown.

The outer folio is folded to interleave with the inner folio, and the inner folio is folded to interleave with a stiff blank supporting accordion structure attached to the inner edges of the front and back pastedowns.

View showing the two folios attached to the front and back covers’ pastedowns and, here, disengaged from the inner supporting accordion structure attached to the inner edges of the front and back pastedowns.

Looked at edge-on, the book seems to comment on the intricacy of its interweaving structure. The intricate balancing act of this binding structure echoes the balancing of the quilter’s-grid shadow, and both echo the balancing of dualities (shadows/reflections, art/nature, life/death, and perspectives) in Still Life, Graffiti, and, as we shall see, the final canto.

Outward appearance of a square back Bradel binding disguises the more intricate interleaved accordion structure inside.

If treated as a codex with the spine resting on the table, the book’s internal structure delivers further surprises. For the first half of the book, opening it reveals four narrow panels of the outer folio at a time. In the gap between the outer and inner folios, a single line of embossed text appears at the top of the inner folio’s narrow verso panel and inked verses at the bottom of the narrow recto panel.

The first four narrow panels of the book.

In the second half of the book, the embossed line shifts from the the inner folio’s verso panel to the recto, and the inked verse shifts from the recto panel to the verso.

The four narrow panels following the midpoint of the book.

The shift of the embossed line to the recto panel and the shift of the inked verse to the verso panel following the midpoint of the book.

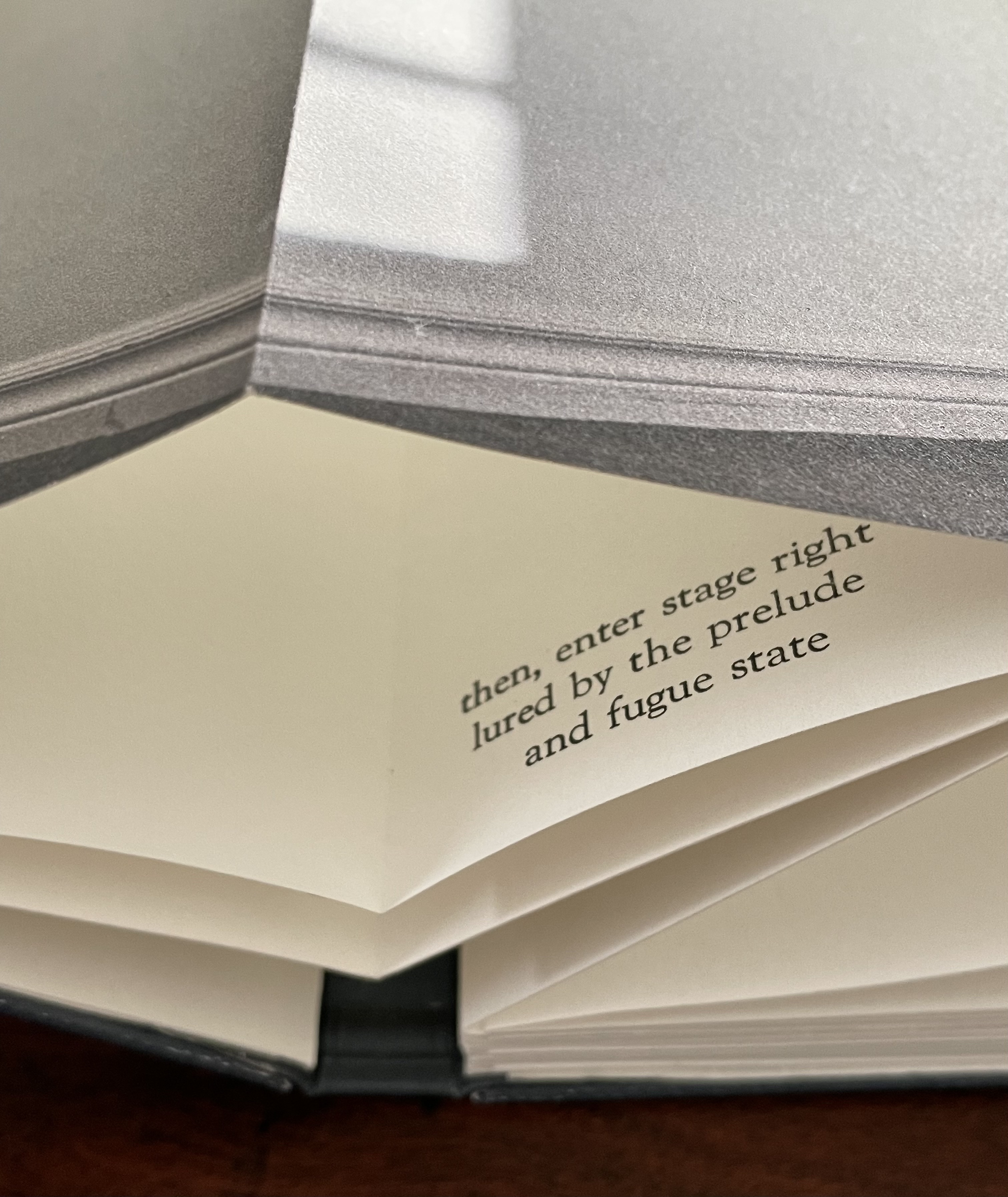

The verse follows the nineteen-line structure of a villanelle: five tercets and a concluding quatrain. Traditionally, the scheme for a villanelle entails the first and third lines of the first stanza repeating alternately in the other stanzas until the last where they form a concluding couplet.

then, enter stage right

lured by the prelude

and fugue state

flood of late sunlight

shadow play fixed and

anchored in stage fright

or, trace flickering flight

patterns of daydreams

bemused state

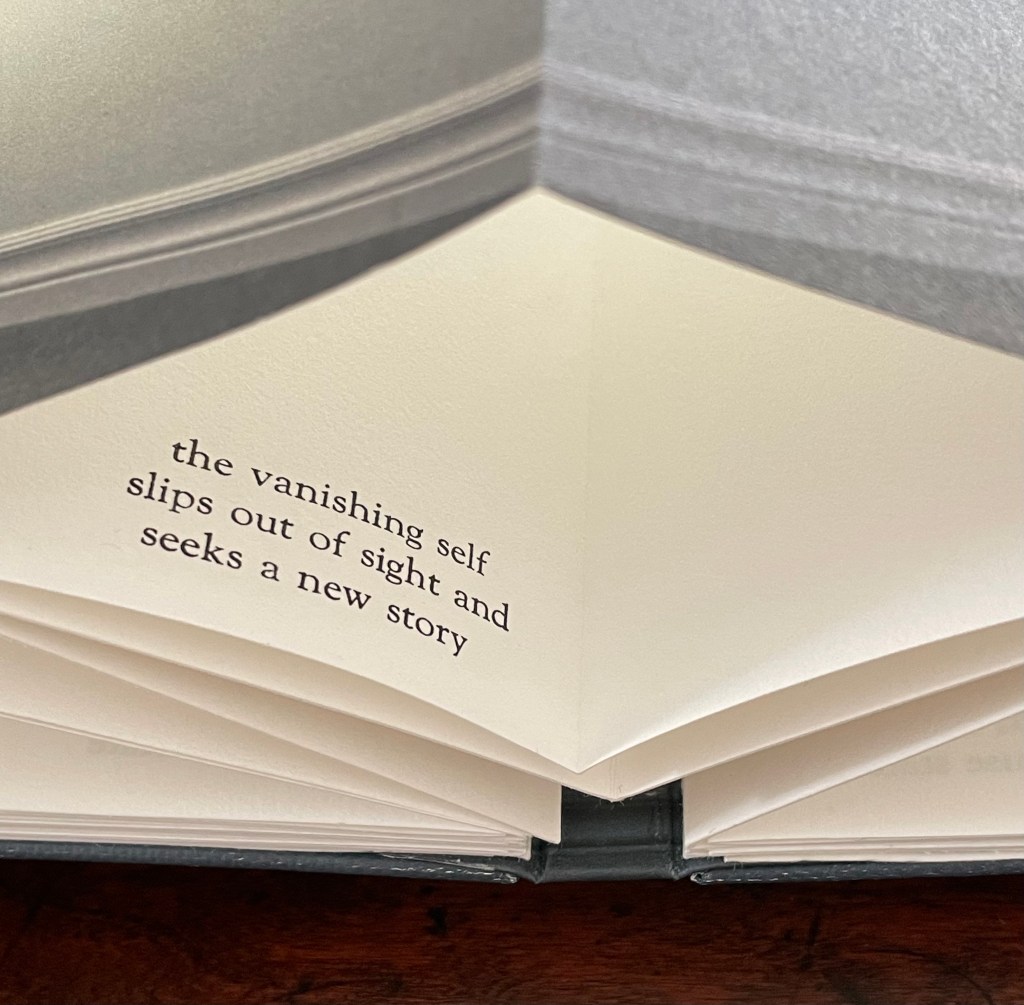

the vanishing self

slips out of sight

and seeks a new story

of fast shifting light

of paper, still white

a muse state

pleated pages expand

unbound from the walls

to enter stage right

renewed state

Adherence to the rules can be loose or strict as these examples from Elizabeth Bishop and Theodore Roethke show. MacCallum’s is of the looser variety, but its intricate interaction with the book’s structure and photographic images more than substitutes for any stricter prosodic demands. For instance, the tercet beginning “the vanishing self” appears immediately after the panels showing the human shadow. In this tercet’s panels, the human shadow has vanished, slipped “out of sight”, and MacCallum has rhymed her words with the book’s photography and structure.

The single lines of embossed text are not part of the villanelle. They play their own visual, auditory, and structural role. Visually and structurally, they counterpoint the verse in color and position. Visually, they echo the moulded white skirting in the photographic images of the room. Auditorially, their recessed words evoke the incidental or background music of the canto’s title: “dust mote static” (as in radio static), “looping clock beats”, “elusive electric hum”, “wing song”, “scattered applause of trees”, and “drawn out sigh of tires”. And again, the artist has rhymed her words with the book’s photography and structure.

Shadow

Canto Four: Travelogue (2021)

travelogue (n.): Originally: a lecture or presentation, usually accompanied by the showing of slides or a film, in which a traveller talks about the places he or she visited on a particular journey and describes the experiences he or she had while travelling. Later more generally: any account of or documentary about a person’s travels, now typically in the form of a film, television programme, or book. Oxford English Dictionary

Shadow

Canto Four: Travelogue (2021)

Marlene MacCallum

Handbound artist’s book. Square back Bradel binding with wrapped back bifolios. Edition of 25, of which this is #5. Acquired from the artist, 26 October 2022. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

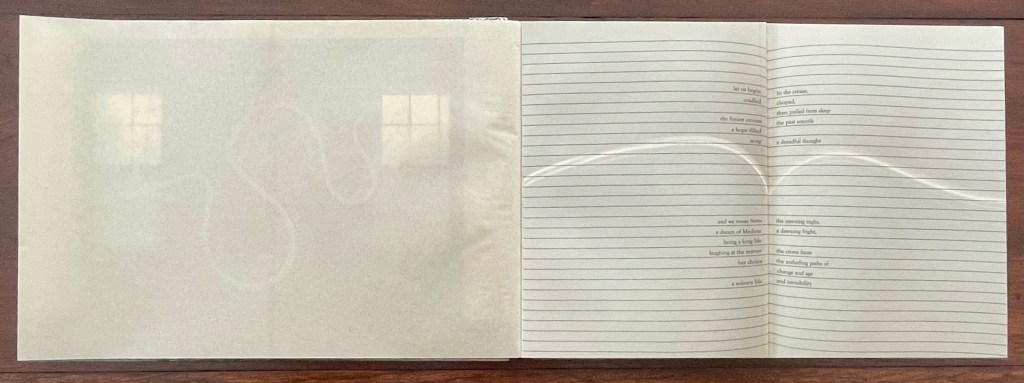

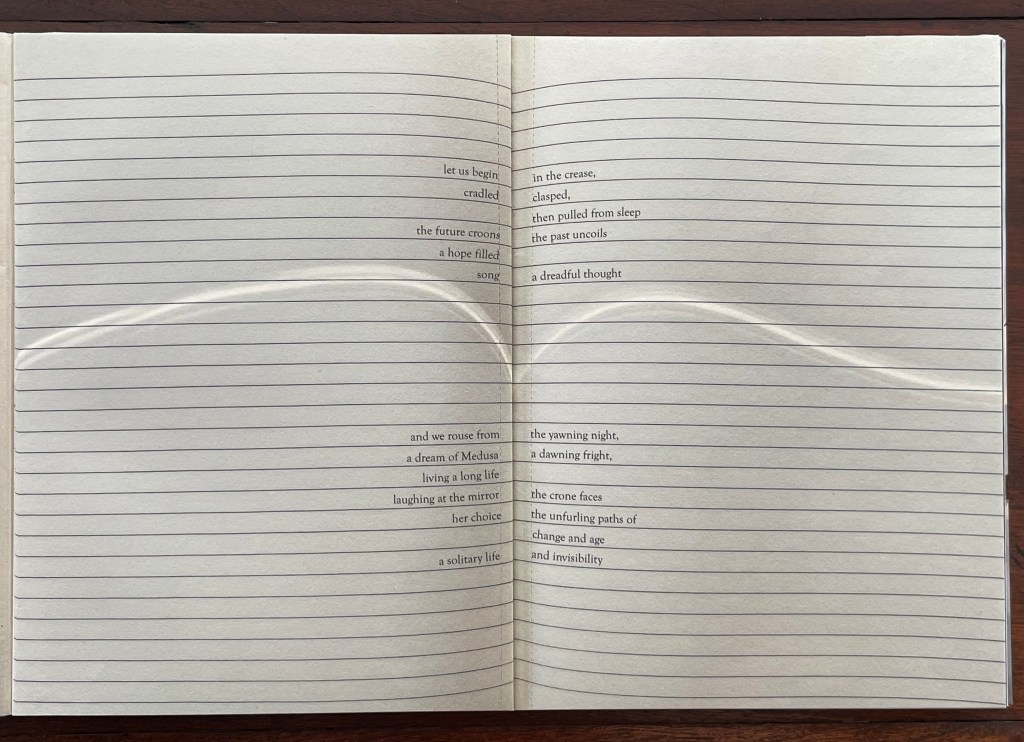

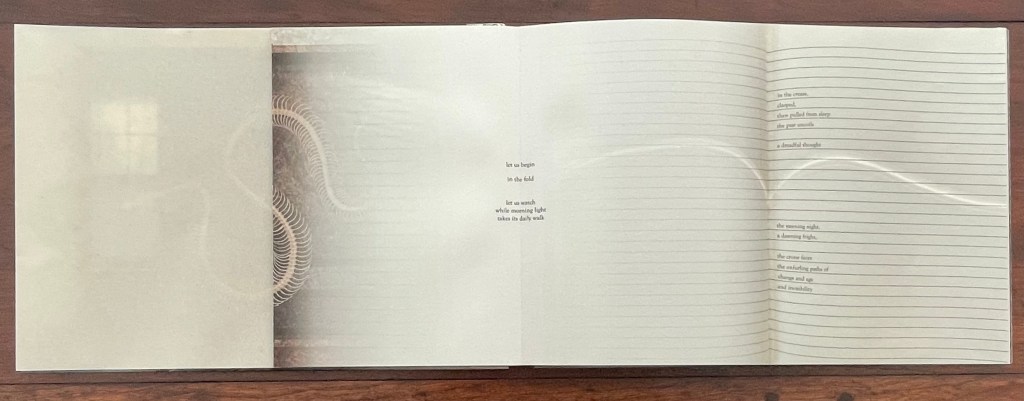

The bridge on Travelogue‘s front cover supports our expectation set by the title. The photograph’s tone and composition along with the slatted blind image on the pastedown and the lined-notebook image after the title page remind us of the painterly style of the earlier books. The interesting combination of a square back Bradel binding with wrapped back bifolios and the alternation of Gampi and Aya papers remind us of the earlier books’ structural and material feats. It’s when we turn that lined-notebook image with it superimposition of curving edges of light that we find a startling juncture.

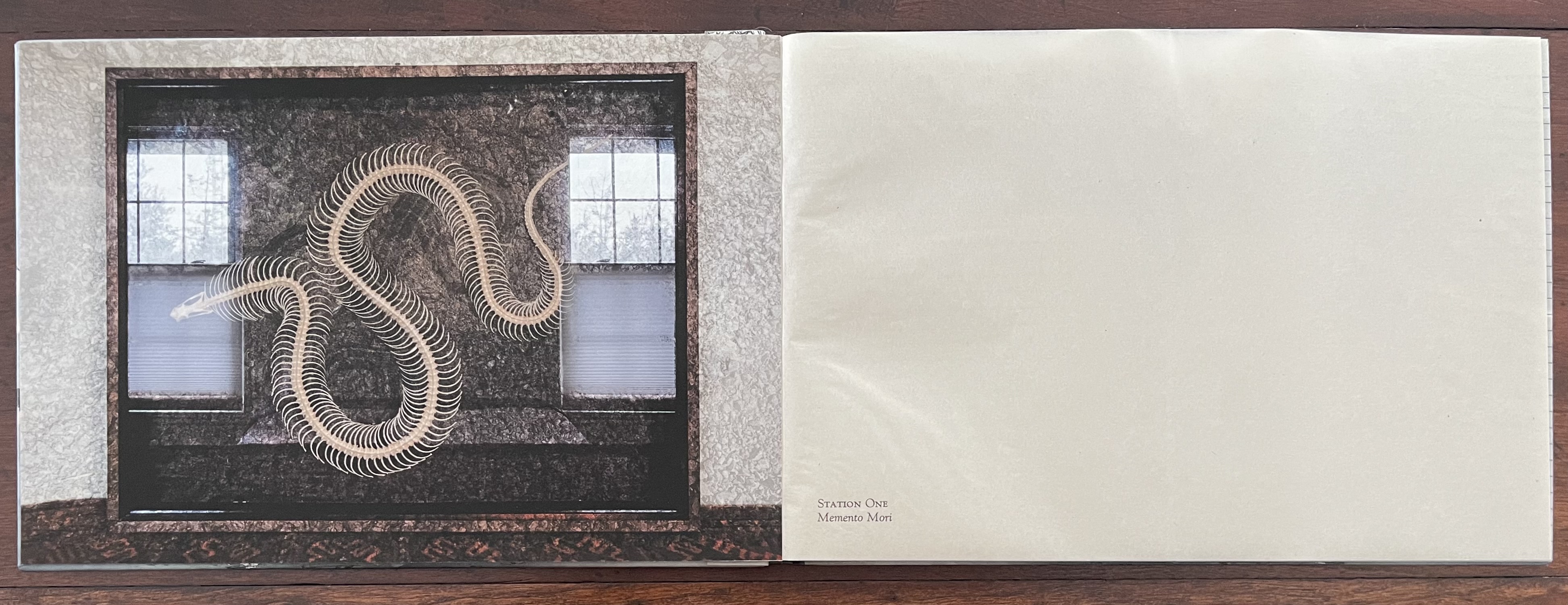

The image of a snake skeleton against funereal marbling overlays the Shadow Canto‘s now familiar two-windowed room, but the label across from it on the letterpress-printed Gampi paper reads “Station One Memento Mori“. Appropriating Pale Fire, underpass graffiti, and sheet music from Bach, Mendelssohn, and Satie are one thing. Appropriating the structure of the Catholic prayer and devotion known as the Stations of the Cross for a travelogue is another. Cruciform images and a stained lace-hanky allusion to Veronica’s Veil later on add to the risk of appropriative disrespect. How will the artist manage it?

Station One “Jesus is condemned to death.”

On turning the page signifying Station One, we can still see the memento mori image through the verso page, and on the recto page, we encounter the first thirteen lines of this canto’s meditation on what appears to be a double-page spread in a lined notebook. MacCallum’s prayer-like language in this canto asserts a sincerity at odds with any sense of secular trivialization or disrespect. Also, as Travelogue proceeds, its textual content and images stand apart from any easy or common examples that might come to mind from the term. Rather it is an extended meditation on dualities of shadow/light, art/nature, life/death, and the journey of personal self/selves with them. In its language and layered construction, Travelogue invites the reader not only to witness this catechismal journey but to become involved, to interact with the construction, to wonder at the layered images and their relation to one another, and possibly become implicated in the artist’s perspective.

The first thirteen lines of meditation. Notice the first line’s semantic and structural self-reference to the book.

The curved light across the notebook is one of those images to wonder at. It came about as sunlight through a slatted blind struck the notebook’s curved surface. Once MacCallum noticed that phenomenon, she returned to the space and set up the journal to be photographed repeatedly as the sun changed angle. It is a serendipity echoing the curving skeleton, the slatted blind of the pastedown, the bird flight of the earlier cantos as well as their shadow/light theme; and it introduces a cruciform image across the apparent double-page spread.

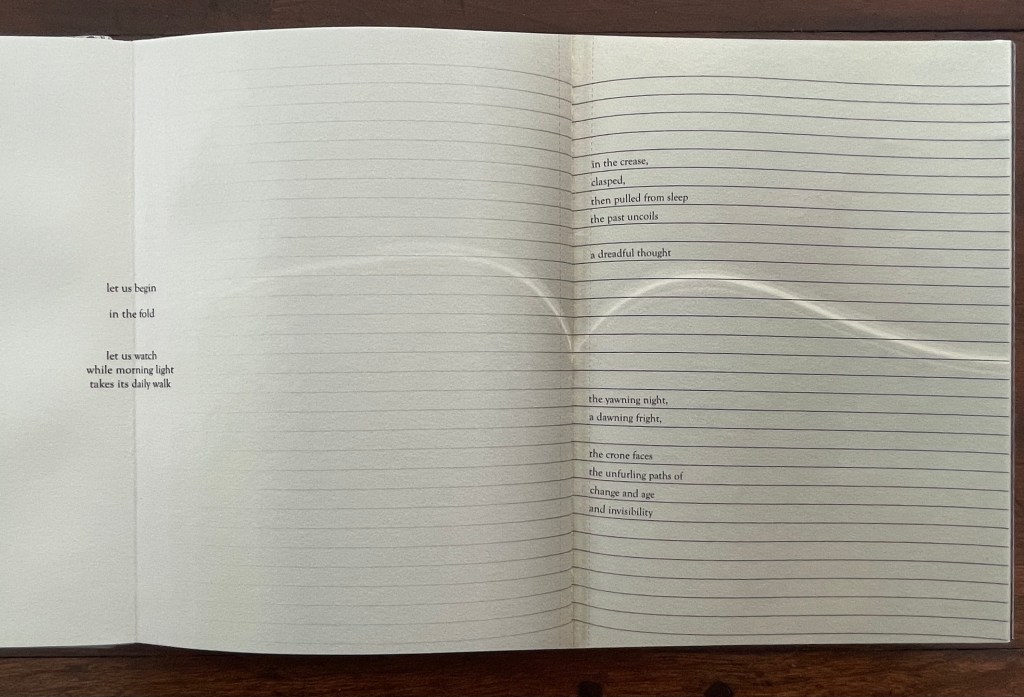

When the verso page of this spread folds back, it shows on its reverse the faint image of half of the snake skeleton now layered over the faint lines of the notebook. The revealed half skeleton aligns with the other half of the skeleton still viewable on the left through the Gampi paper. The effect is a quadriptych of panels across which multiple metamorphoses occur. The first metamorphosis changes the notebook page of text into a notebook page layered with the half skeleton. The second metamorphosis is that the second and third panels appear to form a double-page spread in the notebook because of the notebook lines’ alignments and the five new lines of text centered across the “gutter” of the seeming double-page spread. The third metamorphosis is that the third and fourth panels appear to form another double-page spread, containing a fourth metamorphosis. The text on the fourth panel has changed from its role in the first thirteen lines of litany to the new role of an eleven-line continuation of the meditation.

The quadriptych of metamorphoses

The five lines of the meditation revealed when the apparent verso page of the lined notebook is turned to the left.

The fourth panel’s metamorphosis into eleven lines of meditation.

The first station of the Catholic Stations of the Cross can be Pilate’s judgment of death or Jesus praying in the Garden of Gethsemane. Although both point toward impending death, they do not fit with the usual signals of the memento mori tradition in art: a skull, dying flowers, rotted fruit, dead animals, a watch or clock, etc. The image of a snake skeleton does fit. It would likely be over-interpretive to link the snake to the serpent in the Garden of Eden and the death forecast in the Garden of Gethsemane, but religious art historians would be tempted.

Closer to hand, the Travelogue‘s first station has laid down a baseline of appropriating the landscape format of photobook travel literature and juxtaposing it with the meditative discipline of the Stations of the Cross, of layering and transforming images and text with photographic technique and manipulation of page structures, and of self-referentiality and cross-referentiality among all of these baseline elements. Each of the stations builds on this baseline in different ways.

Station Two “Jesus takes up the cross.”

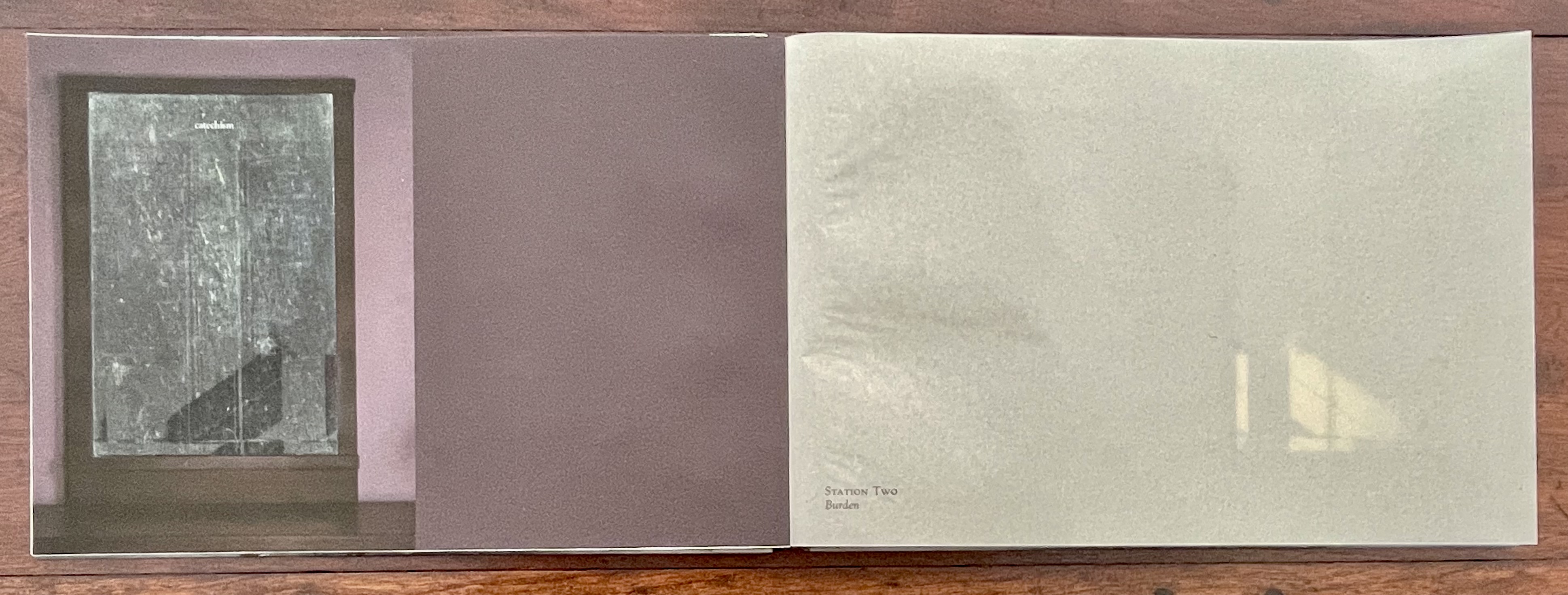

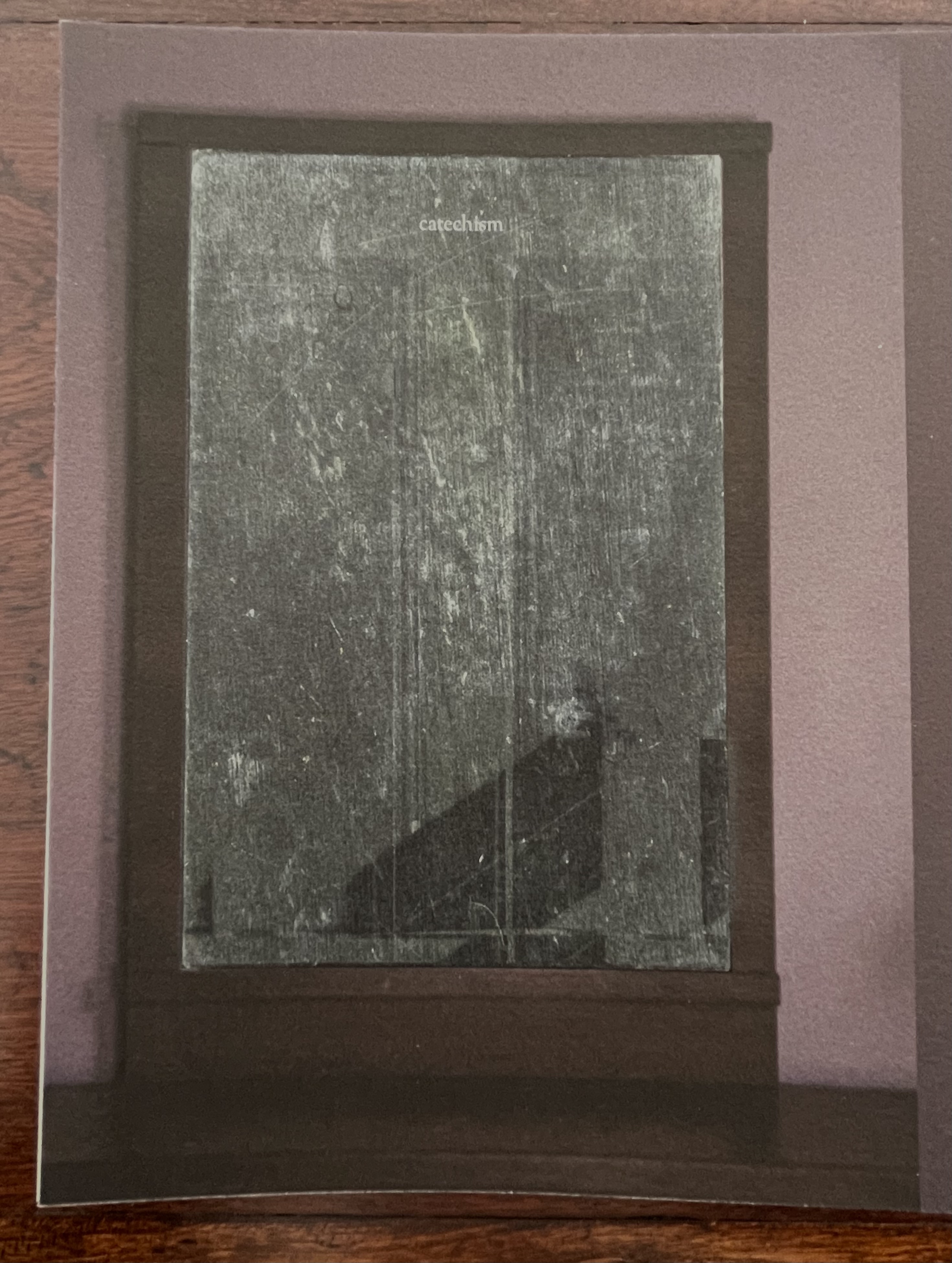

Other than the word “catechism” at the top of the first image, this station has no text. Its “burden” is carried by two images separated by the Gampi paper.

Station Two

Burden

Only after looking at the second image can we know that the wooden frame in the first image is a mirror frame. Only then do we register that the first image is an inversion (a negative) of the mirror reflection. In the second image, that reflection in the bevelled mirror is of two closet doors and the wall space between them. The bevelling generates a perception of depth and also a cruciform image. The secular cross or burden being offered is a dual one: we can only see “as through a glass darkly” and we can only represent our illusion with illusion.

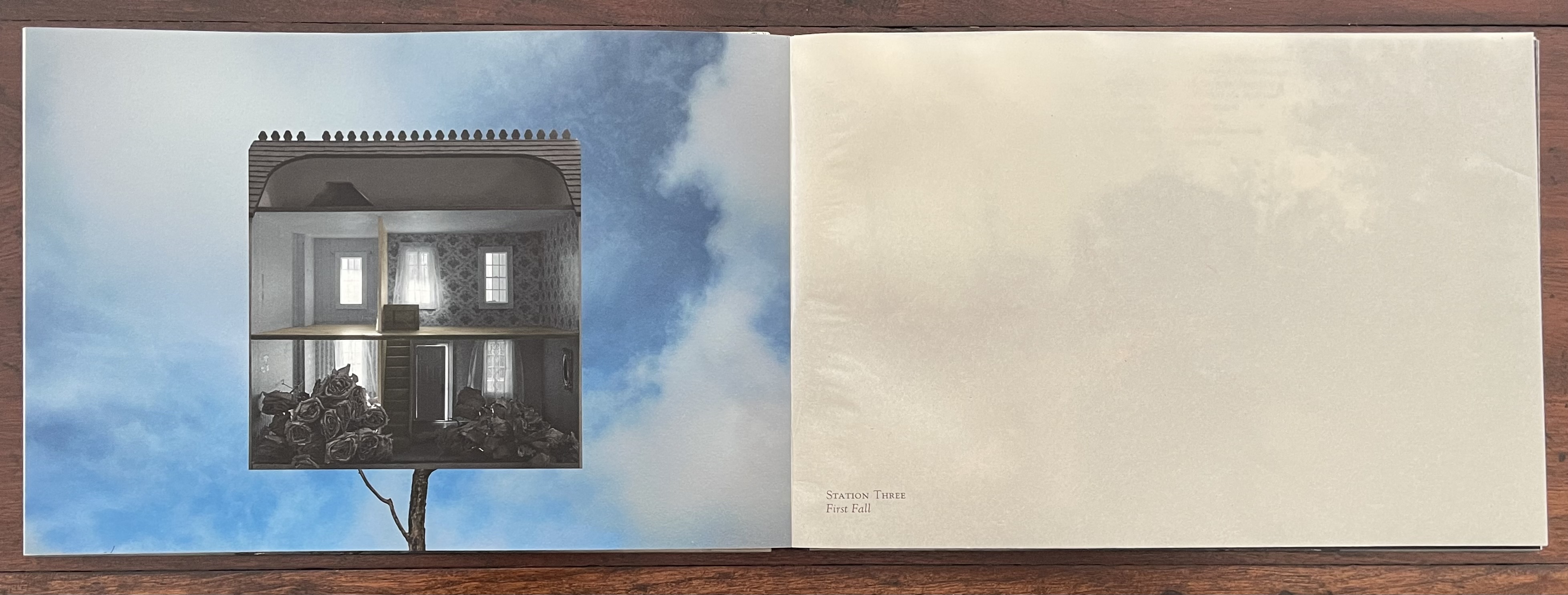

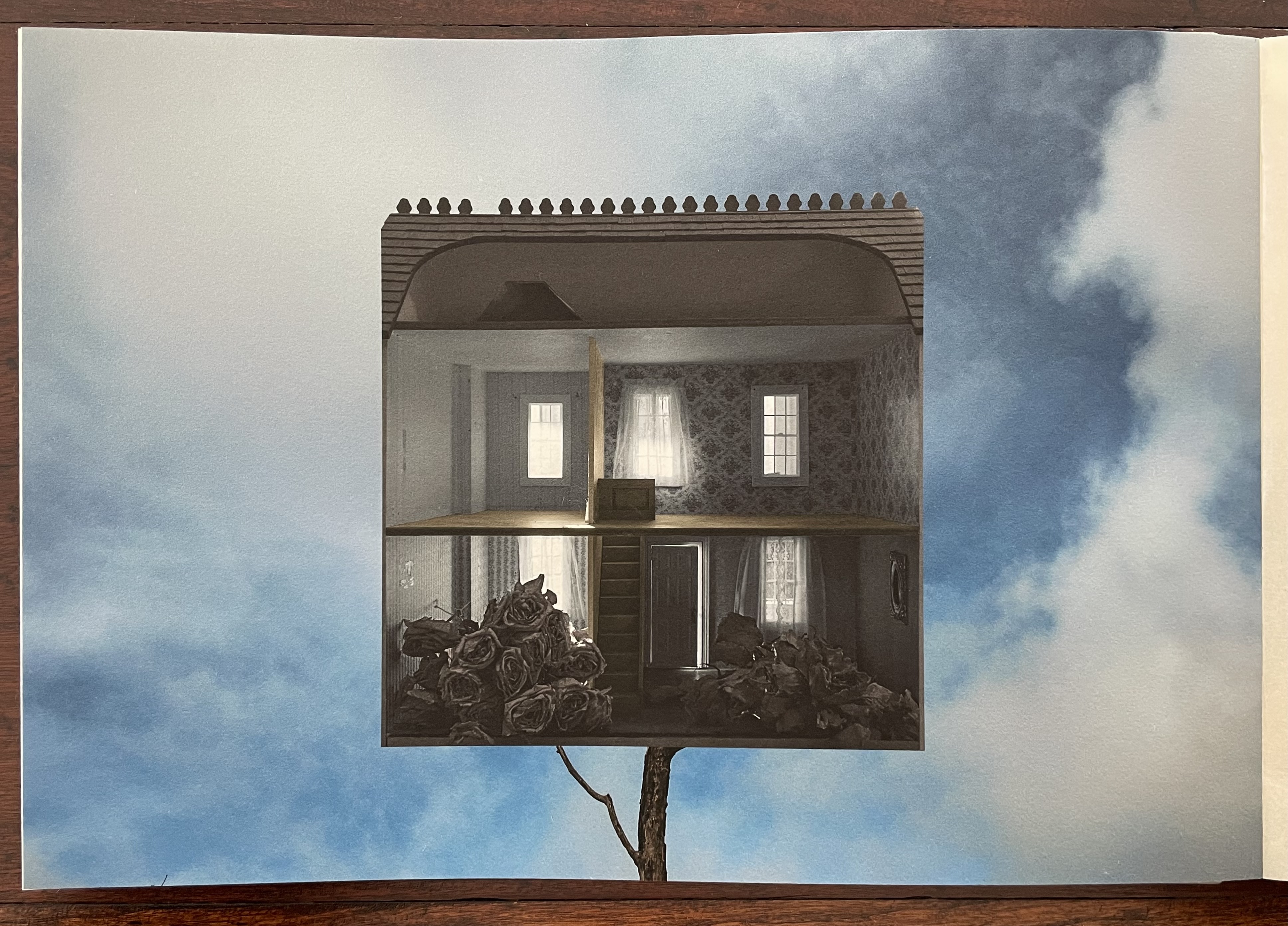

Station Three “Jesus falls the first time.”

The photo of the dollhouse filled with dead roses on its ground floor is perched on a tree branch or narrow trunk against a blue lightly clouded sky.

Station Three

First Fall

Is that surreal secular image a first fall in childhood, the first realization of death? A reductive premonition of MacCallum’s paradoxical themes of interior/exterior, shadow/light, aperture/barrier, art/nature, etc.? Are the dead roses the artist’s future crown of thorns?

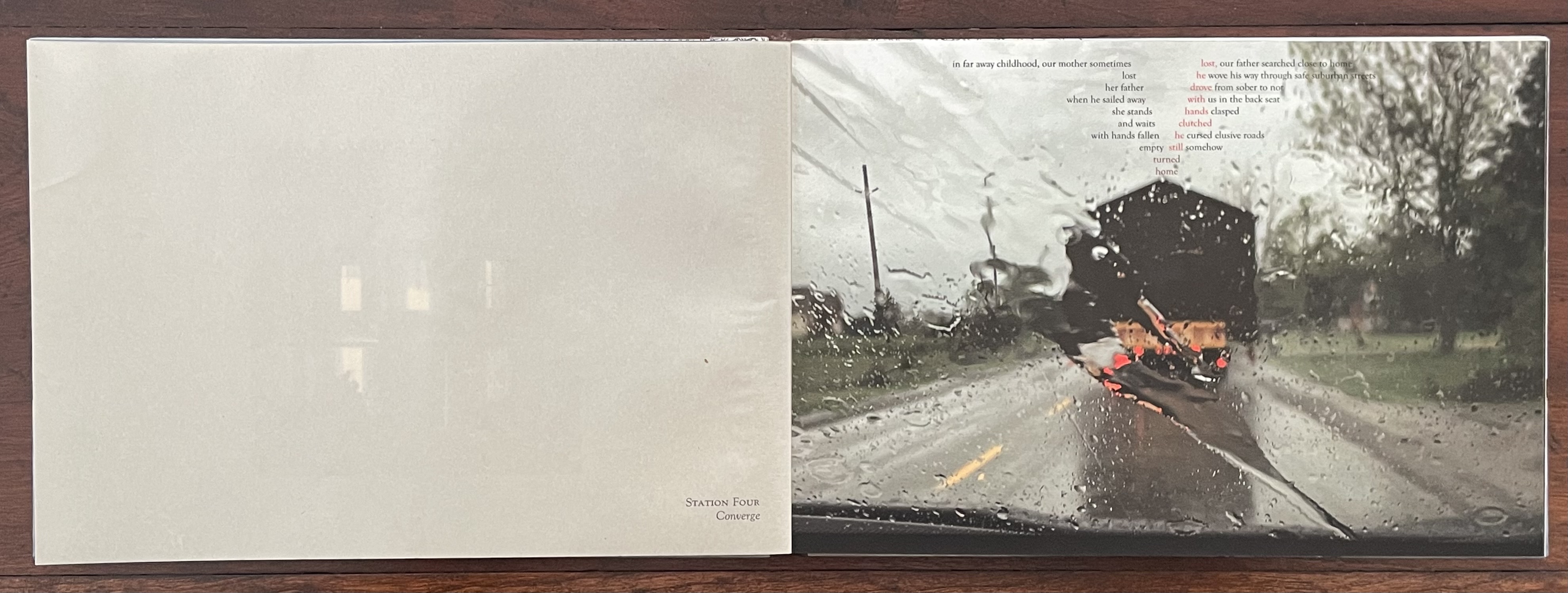

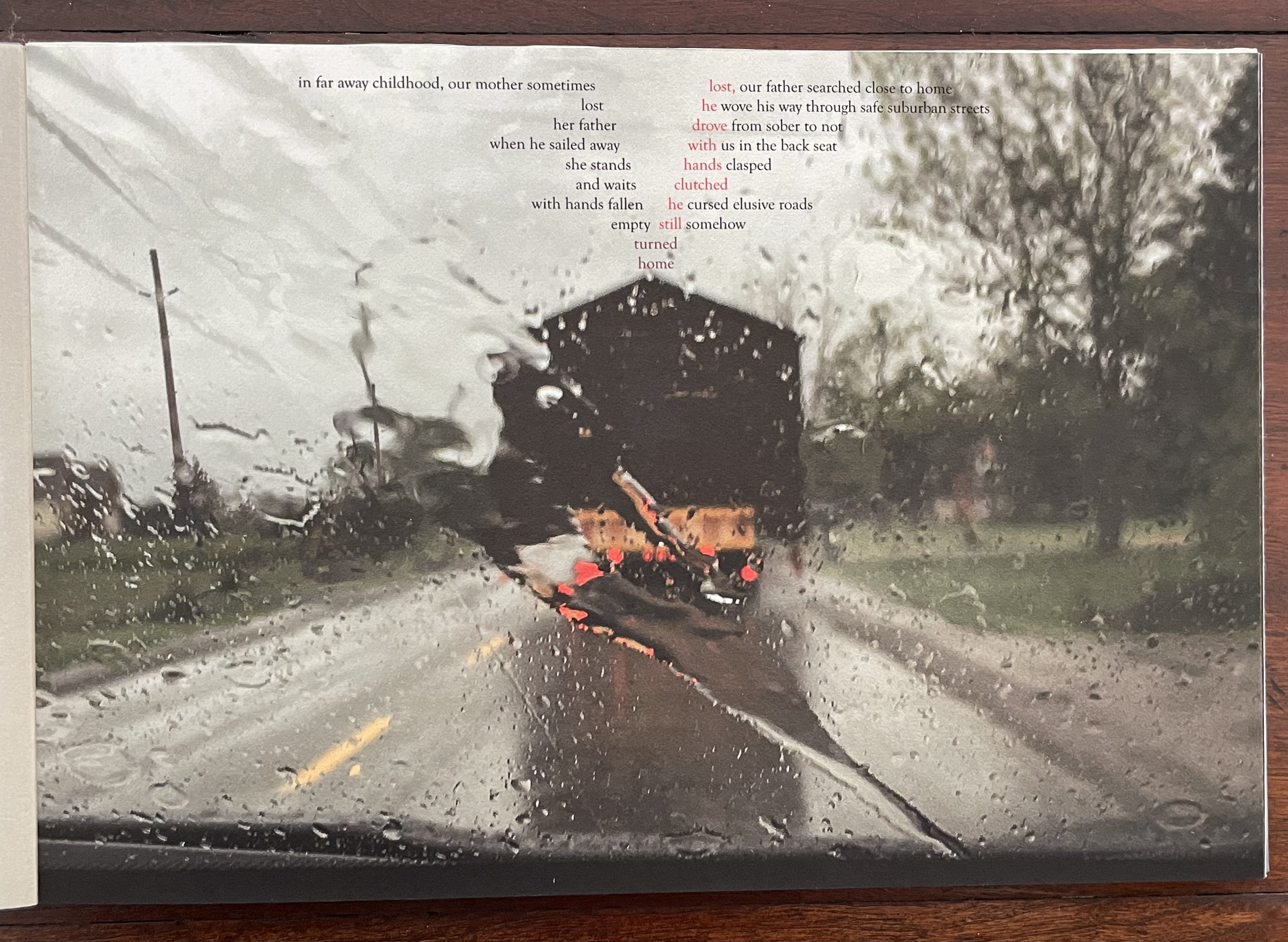

Station Four “Jesus meets his mother.”

Station Four

Converge

So many convergences here. The typographical convergence to the rain-blurred peak of a house on a trailer. The artist’s memories of a mother’s memory of a father, the artist’s memories of her father, all converging to home. The convergence of the preceding curves of light. The convergence of preceding mirror images. We have seen interiorized text converge with exteriorized images across the accordion folds of Incidental Music. We have seen musical notation converge in Graffiti to echo the image of a bird in flight. We have seen a cedar waxwing converge with its shadow/reflection in Still Life.

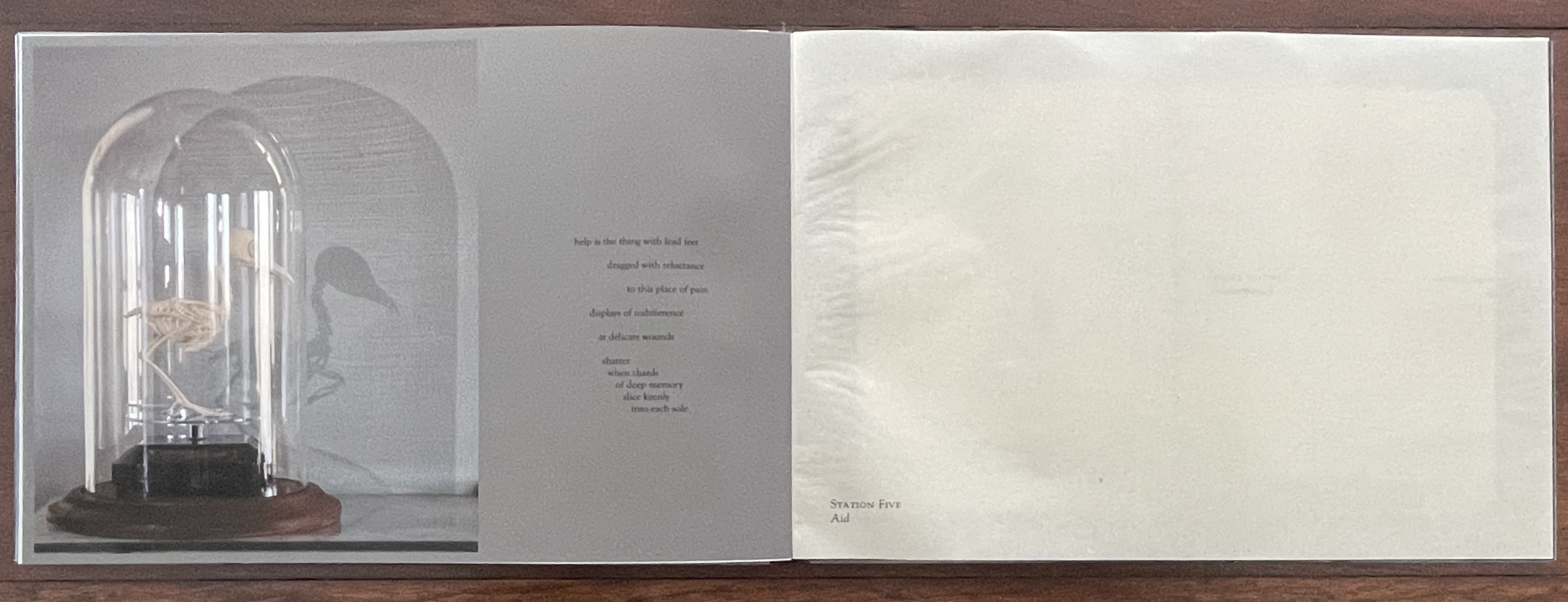

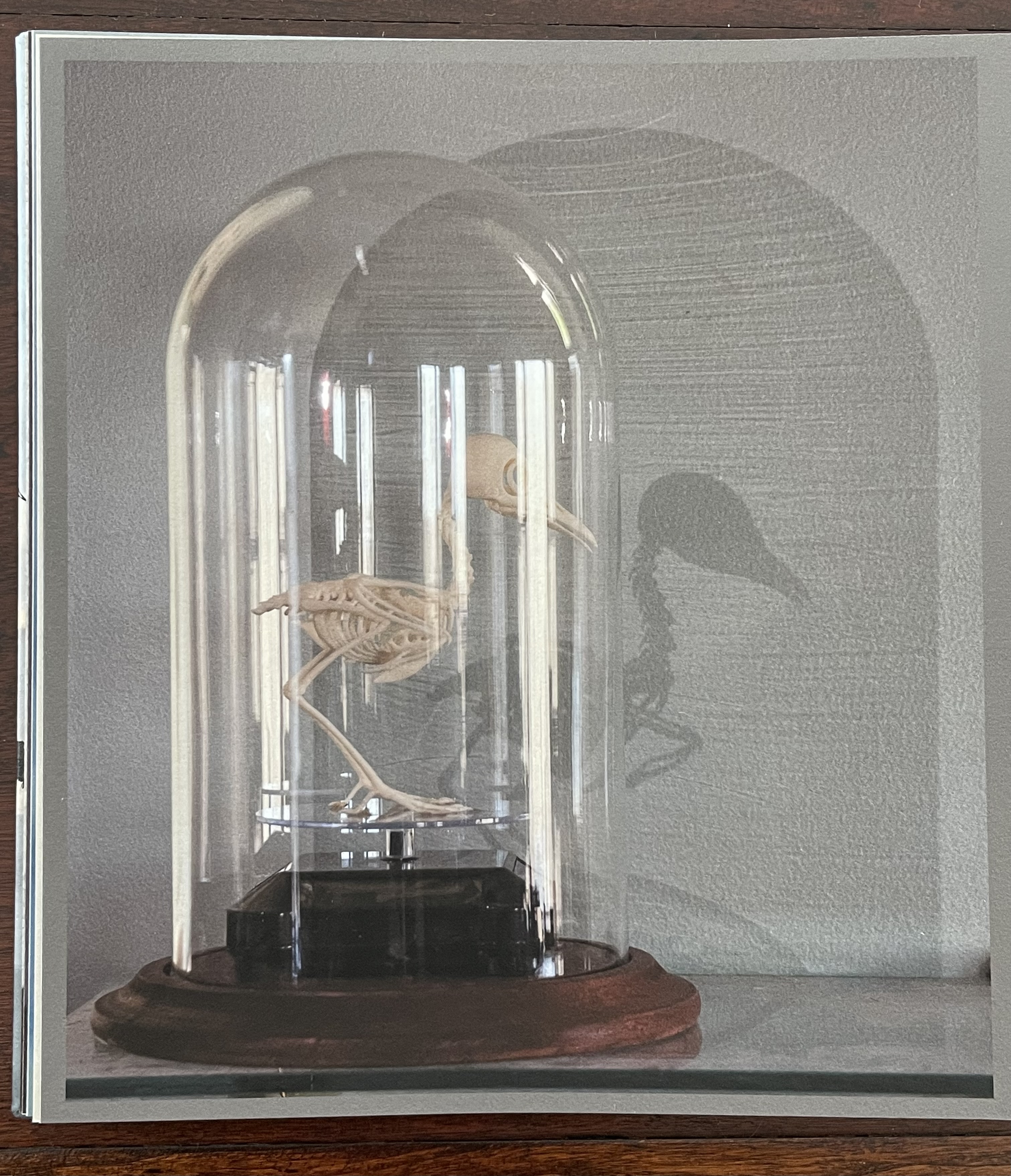

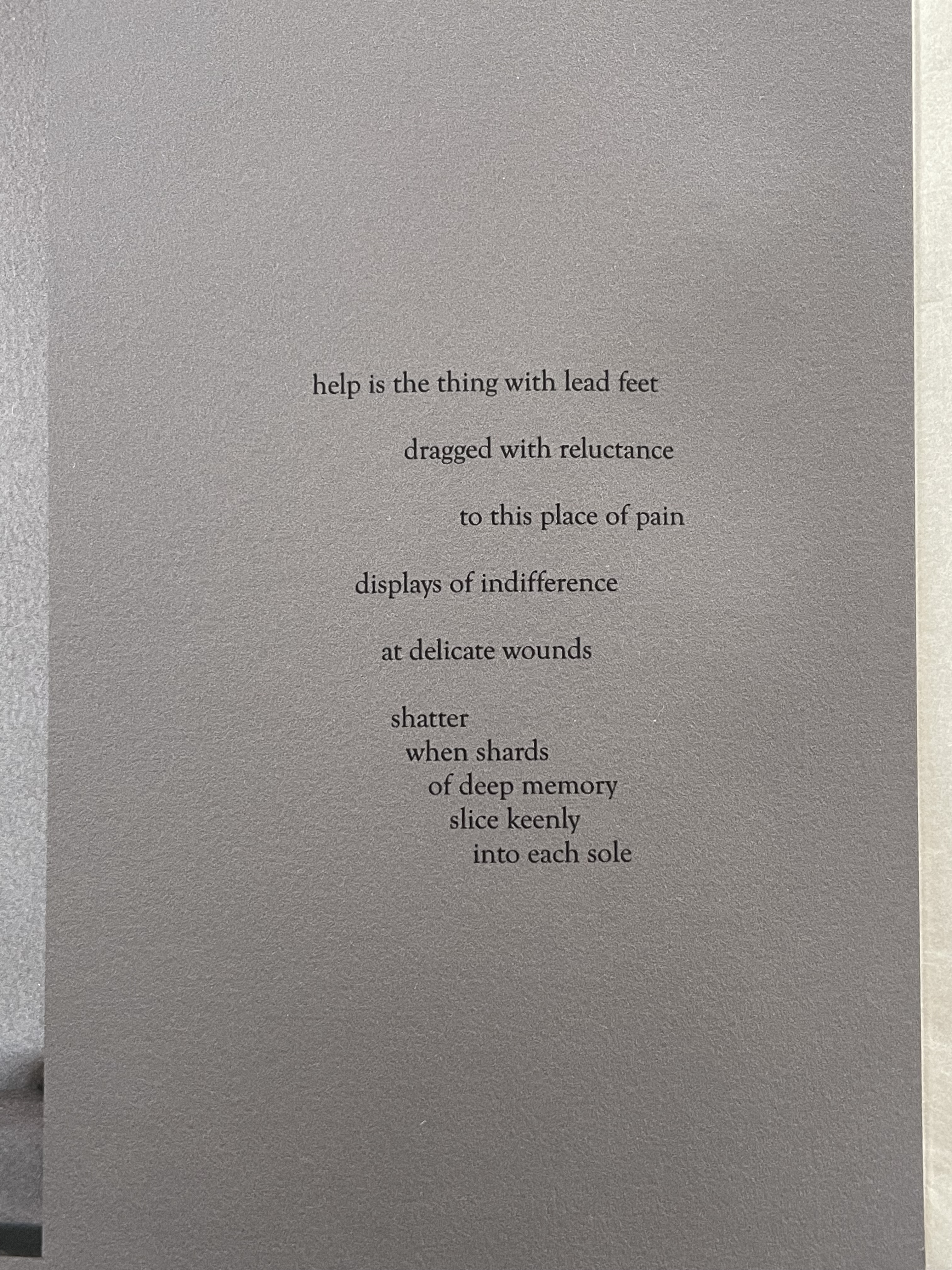

Station Five “Simon of Cyrene helps to carry the cross.”

Emily Dickinson wrote, “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers –“. MacCallum gives us the image of a bird without feathers. First, the skeleton of a snake. Now the skeleton of a bird and its shadow, an echo of the cedar waxwing’s corpse and its shadow.

Station Five

Aid

In the meditation’s words above, these displayed specimens display indifference; after all, the specimens are dead and would be indifferent to the living’s delicate wounds. Nevertheless, the artist has dragged them here for help in “this place of pain” — the place being life, memory, and the creative effort to make sense of it all.

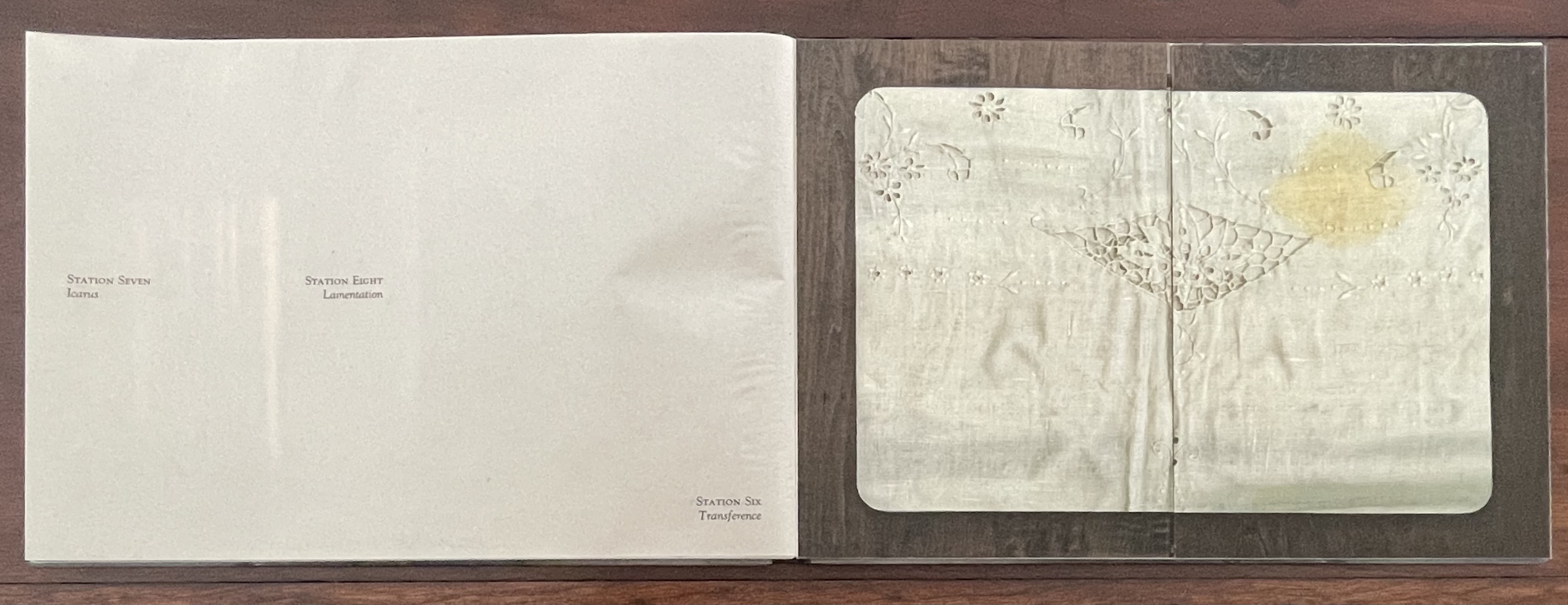

Station Six “Veronica wipes the face of Jesus.”

As with Station One, Stations Six through Eight present multiple metamorphoses, somewhat difficult to follow at first because the labels of Seven and Eight hang mid-page on the left. The label for Six refers to the needlework item on the right whose image runs across the closed edges of a gatefold diptych. The left side of the cloth is a mirror image of itself on the right but without a stain, alluding to the acheiropoietic imprint of Jesus’ face on Veronica’s veil. The religious metamorphosis is replaced with the mundane secular one of tea staining a well crafted handkerchief.

Station Six

Transference

When both panels of the gatefold open, the labels for Stations Seven and Eight fall into place, and we have a spread of five panels.

Station Seven “Jesus falls the second time.”

Jesus’ falling seems a far cry from Icarus’ falling. But then so is a large model airplane fallen into a tree a far cry from an origami bird. And yet that image of the airplane pulls at the image of the bird in flight across its half of the notebook, …

Station Seven

Icarus

Station Eight “Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem.”

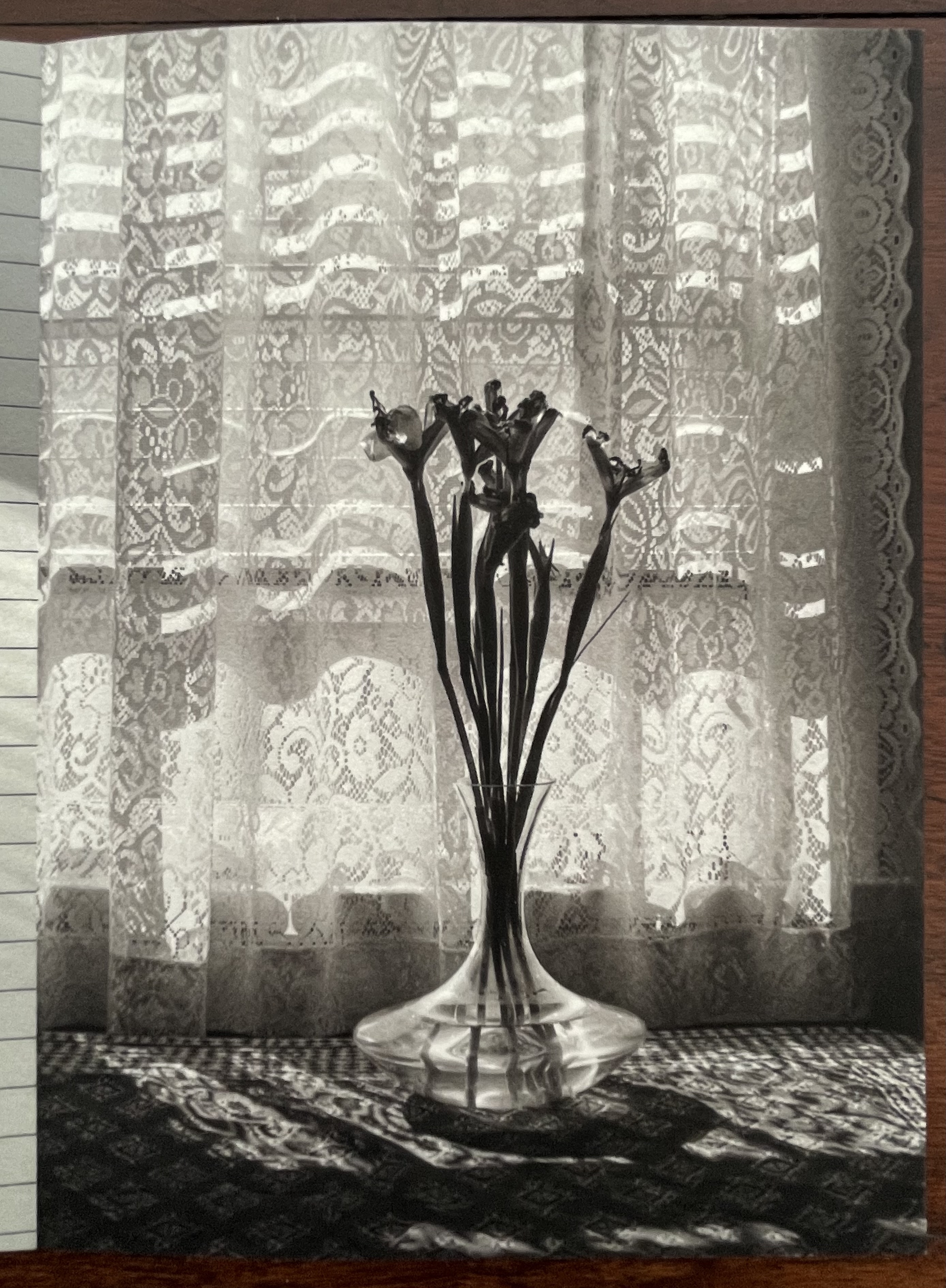

while the text on the other half of the notebook is pulled by the vase of monochrome iris on the right. And yet the centripetal force of the fold in the double-page spread seems to fight against the pull of the images.

Station Eight

Lamentation

The visual tensions pulling and pushing across these five panels seem to parallel the tension of aptness and inaptness of comparing the religious with the secular.

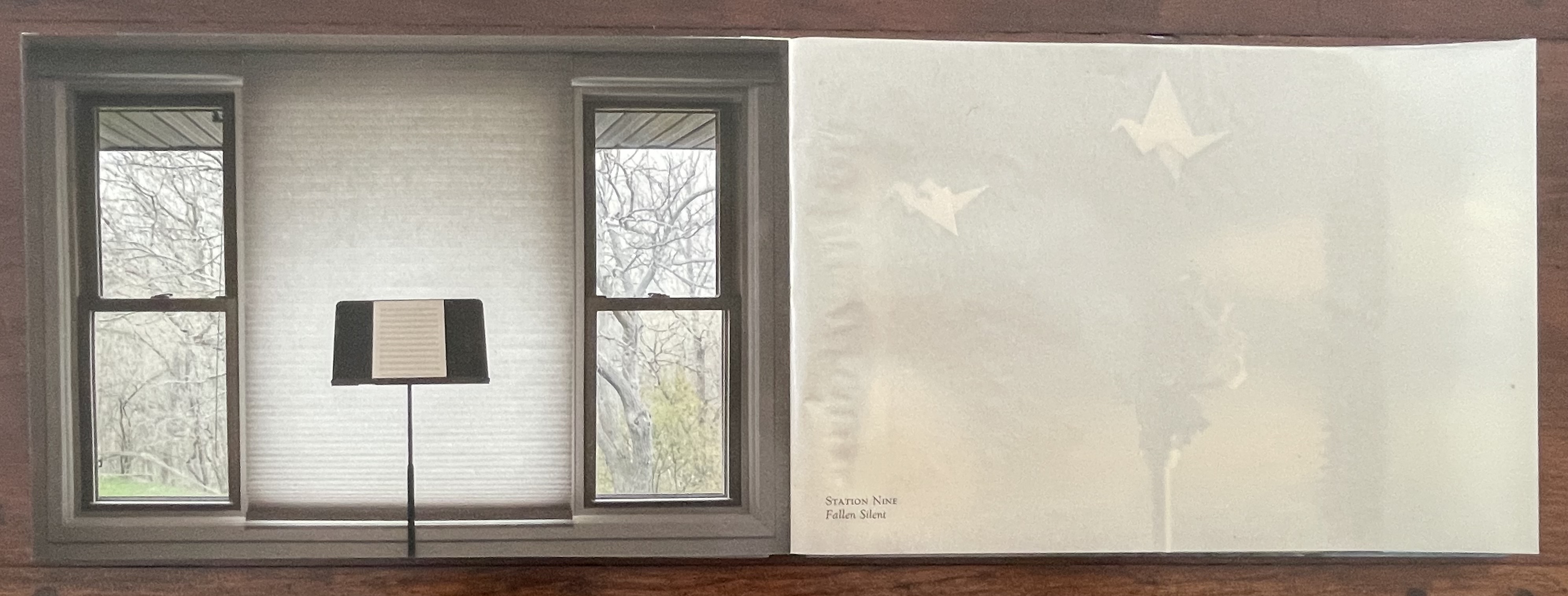

Station Nine “Jesus falls the third time.”

In the secular world, the falling is marked by empty staves on the music sheet as well as the origami birds, recalling the one from the second falling in Station Seven.

Station Nine

Fallen Silent

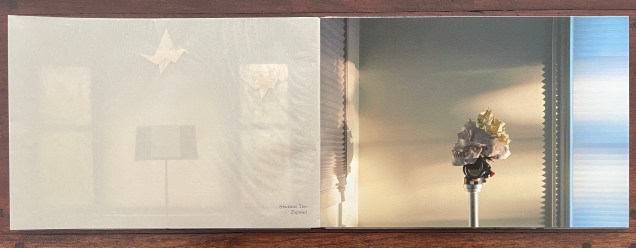

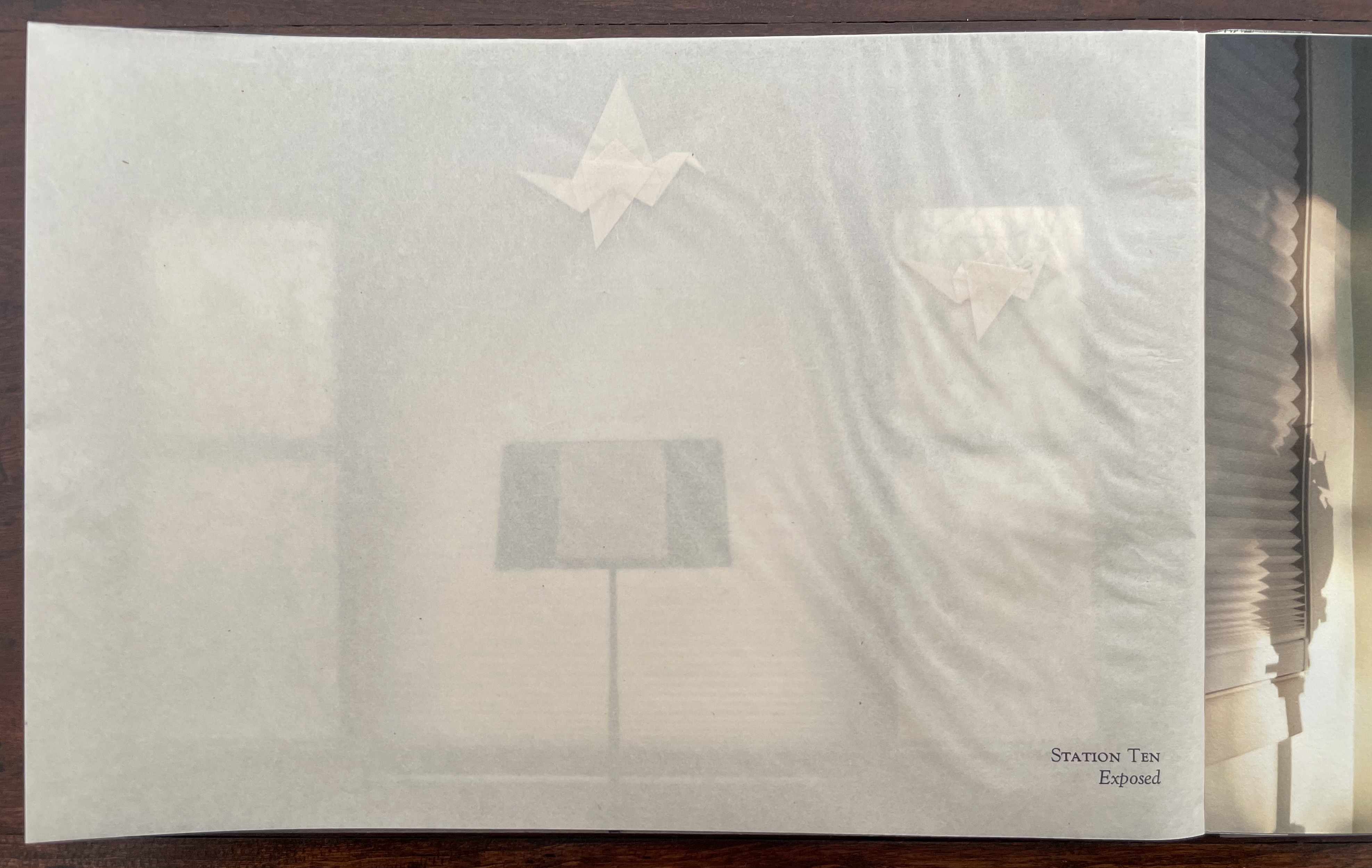

Station Ten “Jesus is stripped of his garments.”

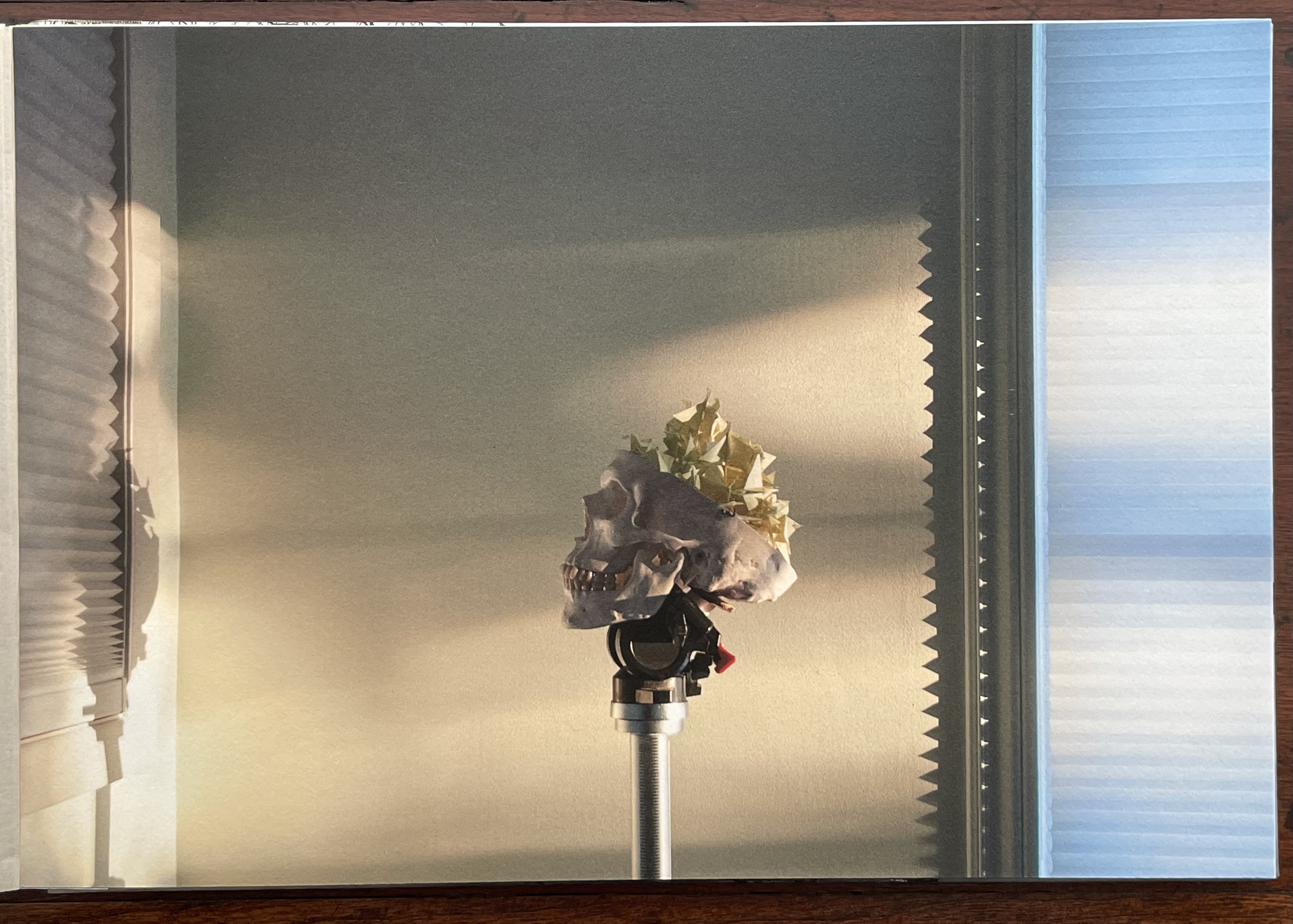

Here is the most macabre of images in Travelogue. Locked into position facing its shadow on the wall, like the inhabitants of Plato’s cave, the skull’s mind displays a flock of origami birds toward which the pair of birds trapped in the verso bifolio now seem to be flying. Will they crash into the window/wall the skull faces and repeat the scene in Still Life? Is that flock of paper birds in the stripped skull its accumulated fears of falling, or its accumulated experiences of the shadowed window/wall (apertures/barrier) on its journey?

Station Ten

Exposed

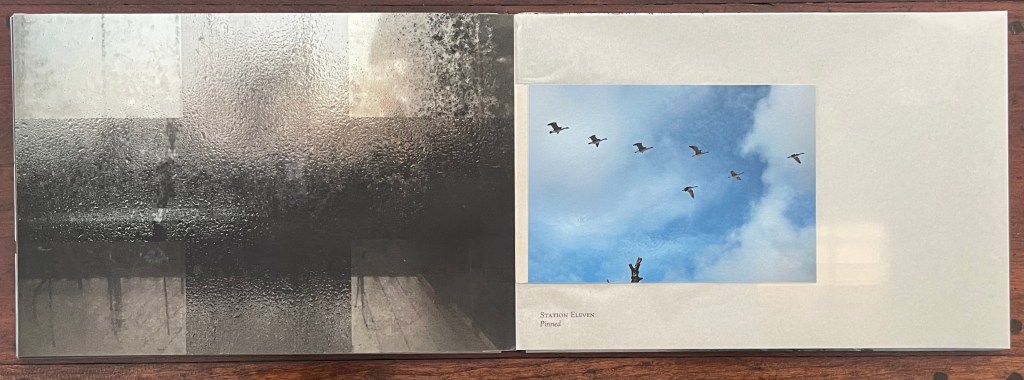

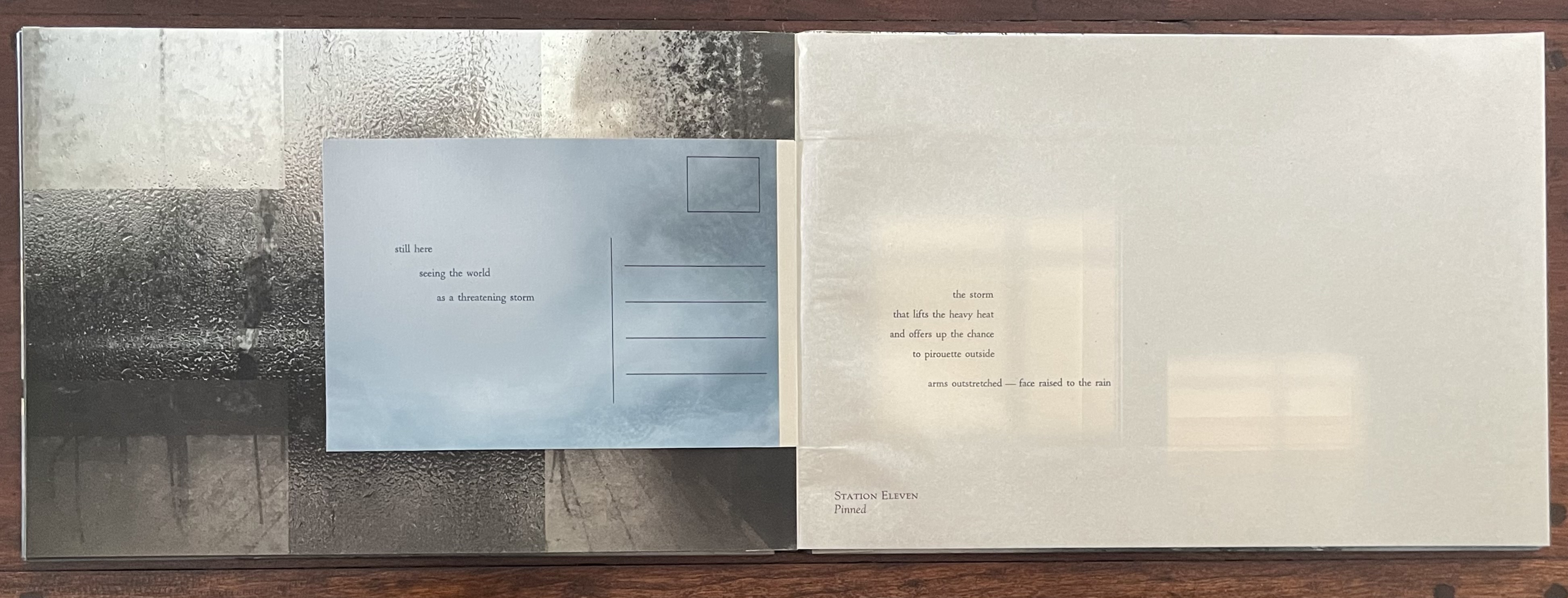

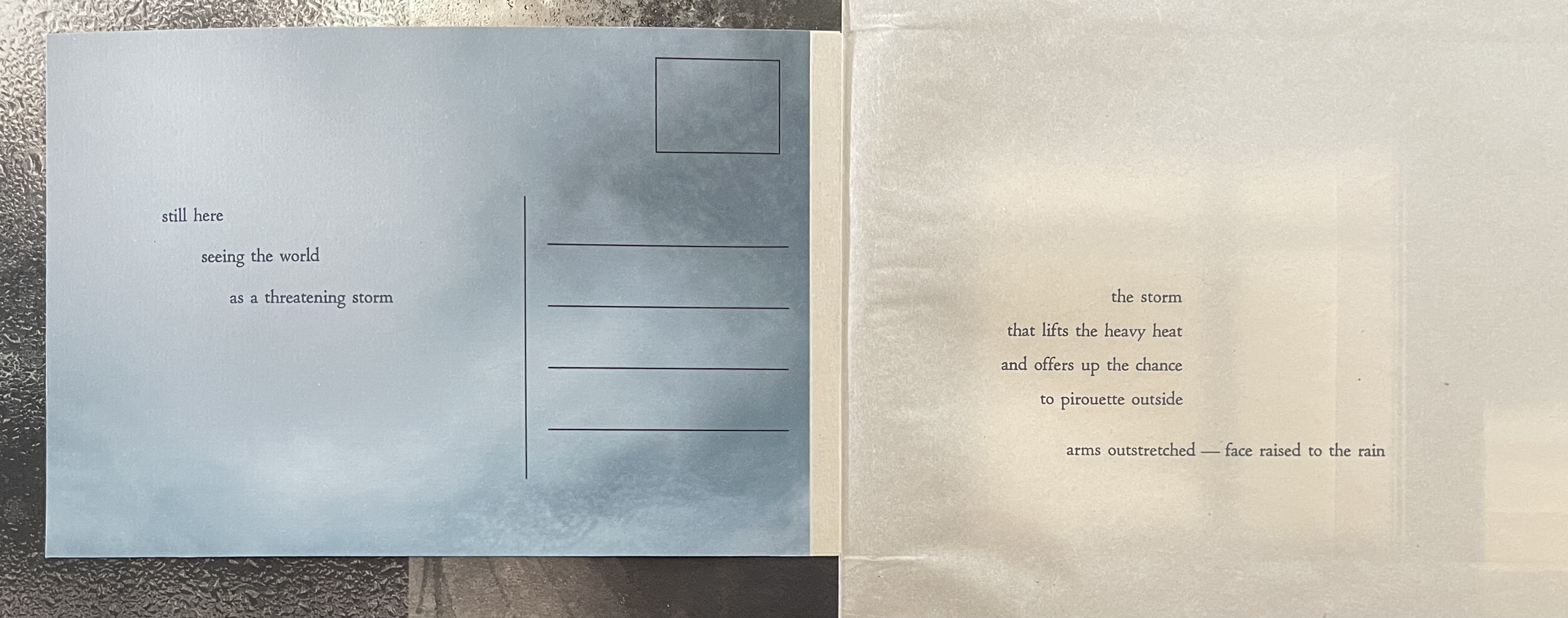

Station Eleven “Jesus is nailed to the cross.”

After the simpler layouts for Stations Nine and Ten, the artist reverts in Station Eleven to one more complicated. As with the more involved layouts of Stations One and Six through Eight, there is more at work with the elements presented. Like the religious station, this secular station represents a moment of intensity. A storm breaks against the window with its cruciform image. In contrast, postcard birds fly across a blue, lightly clouded sky reminiscent of that in Station Three.

When the postcard turns, the meditation on its reverse confirms the storm and also a perspective that is rejected in the stanza that the postcard’s turning reveals on the recto page. Whoever is speaking the stanzas is pinned (nailed) by (and to) the dualities in the images: shadow/light in the window (aperture/barrier), fear and threat versus dancing in the rain, and the religious station’s cross versus Travelogue‘s postcard.

Station Eleven

Pinned

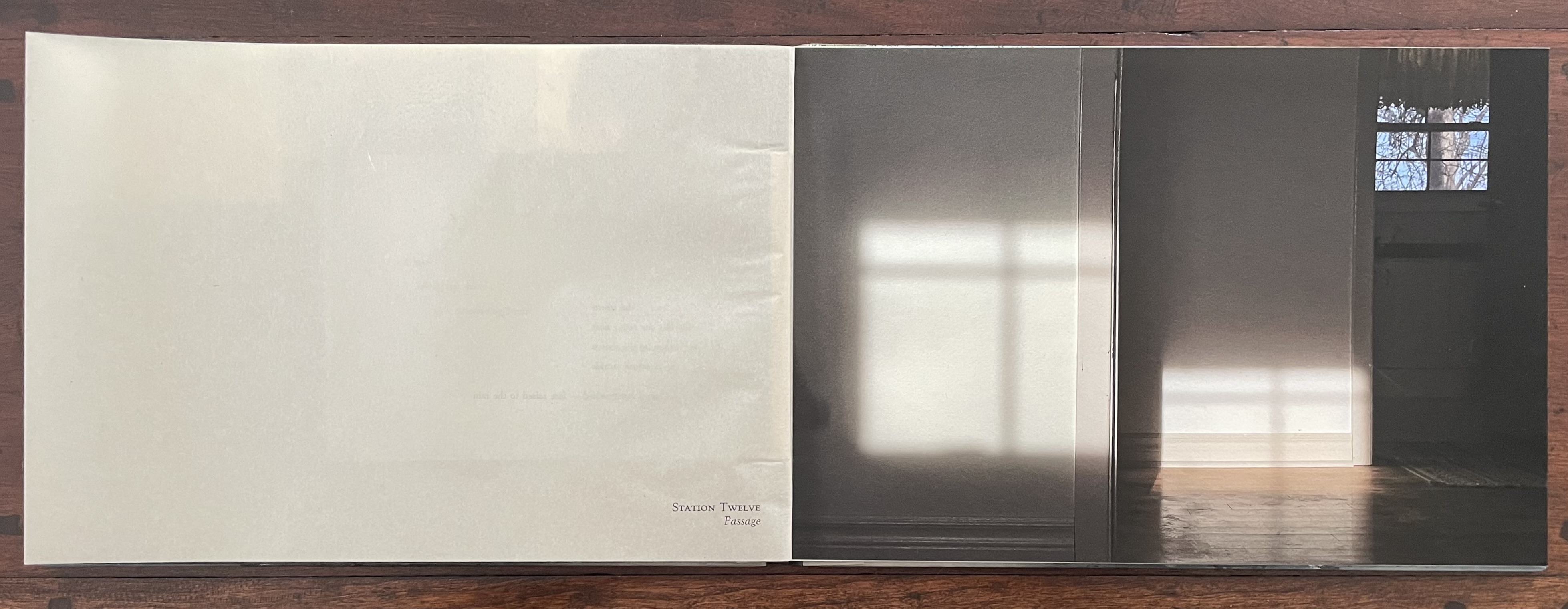

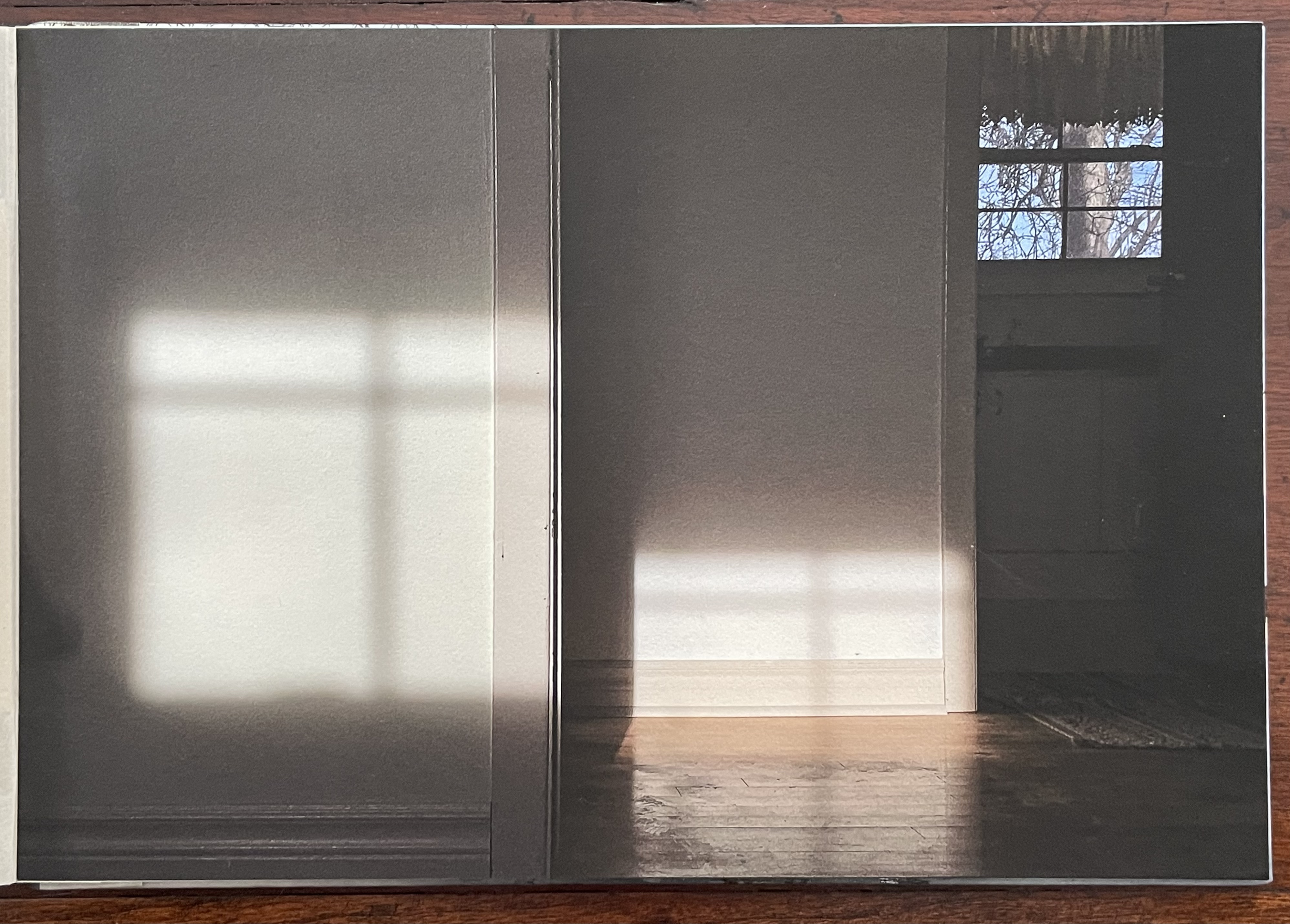

Station Twelve “Jesus dies on the cross.”

Cruciform images shadow the walls of the secular passage to the outside world glimpsed through a half-window displaying another cruciform image. The door, however, is dark and closed.

Station Twelve

Passage

The rooms of this secular passage recall the shadow-and-light-filled rooms of Still Life and Incidental Music, not just those of the other stanzas in Travelogue. Likewise, the empty sheet music recalls the palimpsest of musical notation in Graffiti. Religion has its ways of confronting the dark and closed door; the book artist has hers.

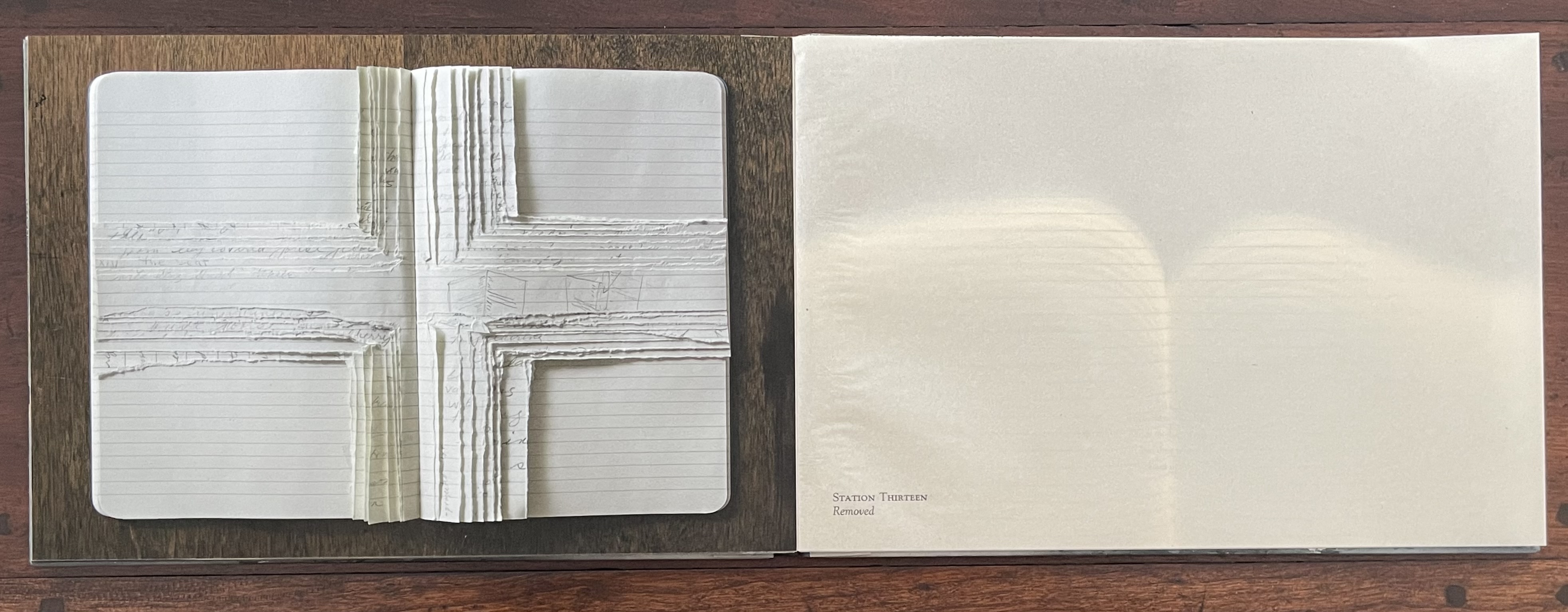

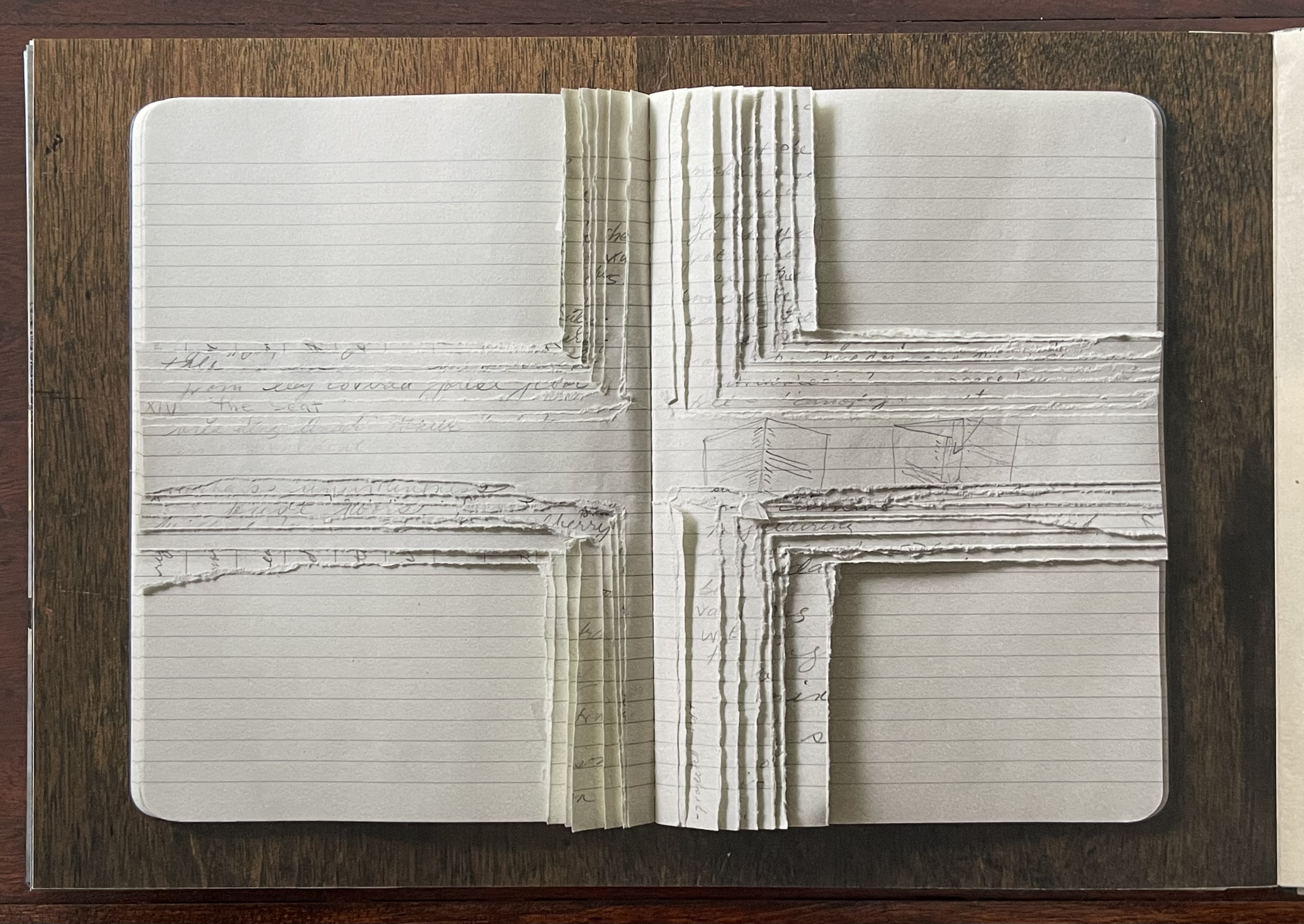

Station Thirteen “Jesus is taken down from the cross.”

Typographers, visual artists, sculptors, and architects know that empty space is just as important as filled space. By “deposing” the paper in four corners of the notebook, the book artist has left us with another cruciform image.

Station Thirteen

Removed

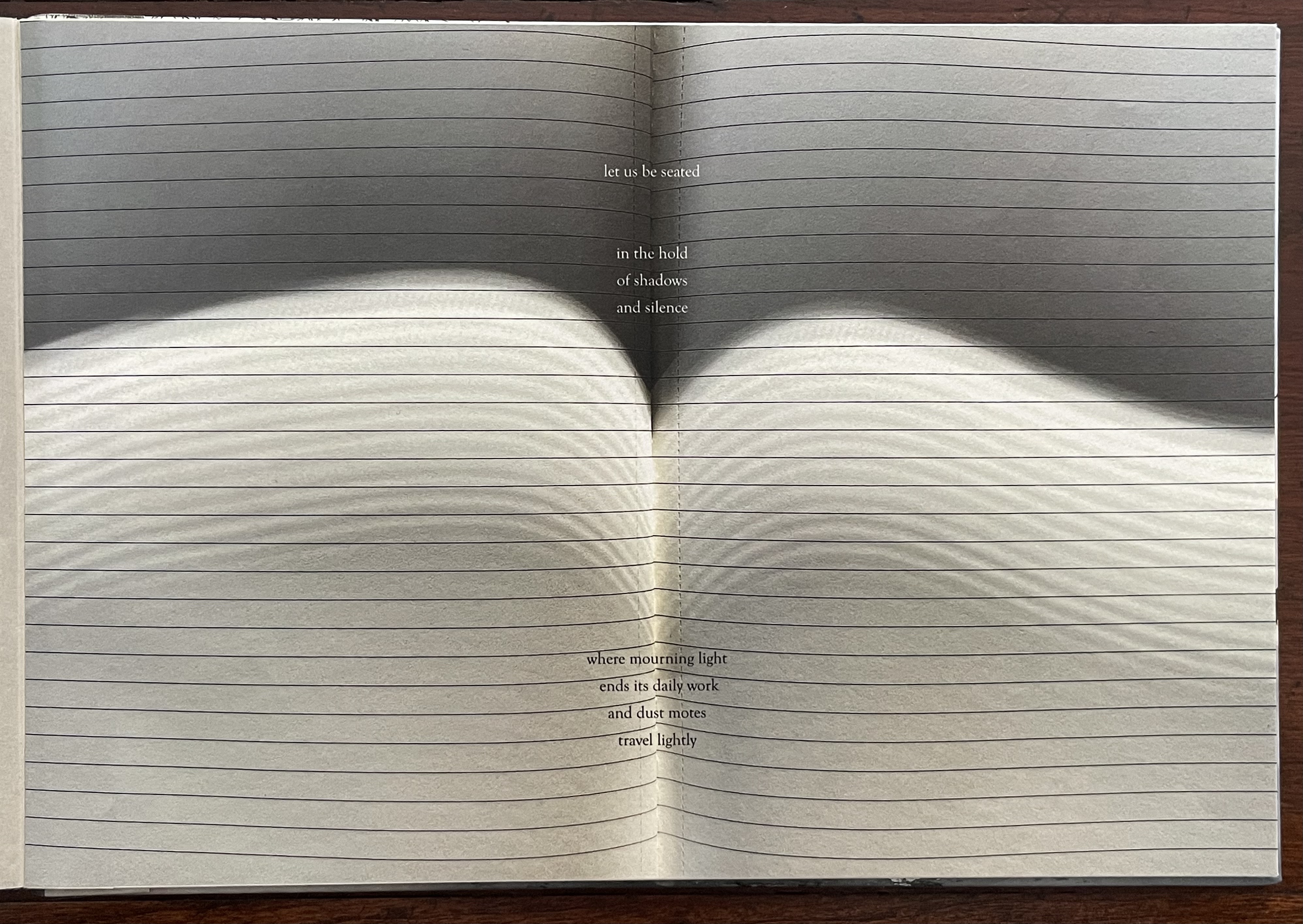

Station Fourteen “Jesus is laid in the tomb.”

When the Gampi paper turns to the final station, the cross of torn pages still shows faintly behind it. It lies in parallel with the meditation centered on the cruciform image formed by shadow above the accumulated curves of light on the notebook. Instructed to be seated in the shadows, silence, and mourning, we seem to have come to the secular as well as religious end.

Station Fourteen

Residue

But the seeming end is really the beginning.

Throughout the Shadow Quartet, MacCallum has maintained a certain distance. In Still Life, when the dead cedar waxwing speaks of “your sympathetic vibration”, it could be addressing the reader. We only know that it is MacCallum’s experience from her artist’s statement accompanying the work. In Incidental Music the villanelle’s rhetorical mode is a mix of stage instruction, description, and narrative; it is impersonal.

Travelogue, too, seems impersonal with its final instruction: “let us begin”. But it is the book artist giving the instruction, and it was the book artist giving us the same instruction in Station One “to begin” at the crease and in the fold. In Station Four, it is the book artist sitting in the back seat of the car recalling her parents and their trips. It is the book artist’s journey we are witnessing — a journey from religious spirituality to a secular spirituality. By addressing us as she does, by presenting visual and material challenges as we move through the book, though, the book artist implicates and involves us in her journey. So at the end of Travelogue, we have a choice.

Just as Travelogue‘s meditation began with “let us begin”, so it ends. Like the other cantos, Travelogue urges us to embrace “our innermost rooms”, “our house-bound route”, our “windows and walls”, “our sanctuary prison”, and with them their shadows, uncertainties, and ambiguities. It invites us to their “close circumnavigation” as the means of facing “life’s fourteen stations” and “free[ing] ourselves on this day’s walk”. Far from disrespectful appropriation, Travelogue is a personal, respectful renunciation of “the shadow of religion” in favor of the shadows and light themselves. If the reader accepts the invitation, it will be to reread and reread the Shadow Quartet.

Shadows Cast and Present (2019)

The artist gratefully acknowledges the Canada Council for the Arts Digital Originals grant program for funding this project and the CBC/Radio Canada for partnering to provide a national platform for this new work.

Given the conceptual and synesthetic play within the four cantos, this digital re-imagination of them follows on with a natural ease. With the assistance of Matthew Hollett and David Morrish, the artist has created an online variation of the long-poem format. Images, text, video and soundscapes come together in an interactive presentation of shadows cast in domestic spaces and by daily activities. Click on the image above or here to view.

With MacCallum’s other works (see Further Reading), the Shadow Cantos put her work in the same class as Michael Snow’s Cover to Cover (1975) and Abelardo Morell’s A Book of Books (2002).

*The earlier version of this entry has been extensively edited and updated here to include Canto Four: Travelogue.

Further Reading

“Marlene MacCallum (I)“. 2 September 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Marlene MacCallum (II). 19 September 2024. Books On Books Collection.

Levergneux, Louise.5 January 2021. “New Year, New Work“, Half-Measure Studio Blog.

MacCallum, Marlene, Gail Tuttle, Lisa Robertson, and Sir Wilfred Grenfell College Art Gallery. 2007. The Architectural Uncanny. Corner Brook: Sir Wilfred Grenfell College Art Gallery.

Root , Deborah, and Marlene MacCallum. 2021. “On Marlene MacCallum’s Shadow”. IMPACT Printmaking Journal 4 (November):11.