Altered books as artists’ books present a seemingly endless variety.

Some may be the conversion of old books into just-legible new ones as in A Humument redacted with ink, paint, excision, and collage by Tom Phillips, Tree of Codes mechanically excised by Jonathan Safran Foer, or The Eaten Heart scalpeled into existence by Carolyn Thompson. They give us a new work to read page by page extracted page by page from the earlier work, which remains more or less (mainly less) present in our hands.

Others like Marcel Broodthaers’ page-by-page redactions of Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés by ink in one case and excision in another or Michalis Pichler’s similar reformatting and excision of the same poem in clear acrylic or Jérémie Bennequin’s page-by-page erasures of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past give us artists’ books that make the altered books illegible but still accessible page by page.

Other altered books as artists’ books are mainly one-off spatial objects that can be taken in in one go — not necessarily in just a glance but in the look or gaze given to a sculpture or painting. The ground up and encased works in Literaturwurst by Dieter Roth. The sealed, painted, nailed, and “hairied” works of Barton Lidice Beneš. The torn works of Buzz Spector. The sandblasted works of Guy Laramée. The glued and carved works of Brian Dettmer. The bullet-hole-ridden Point Blank by Kendell Geers. The pun-packed moebius-sculpted Red Infinity #4 by Doug Beube. They give us artists’ books that make the altered books illegible and inaccessible as books.

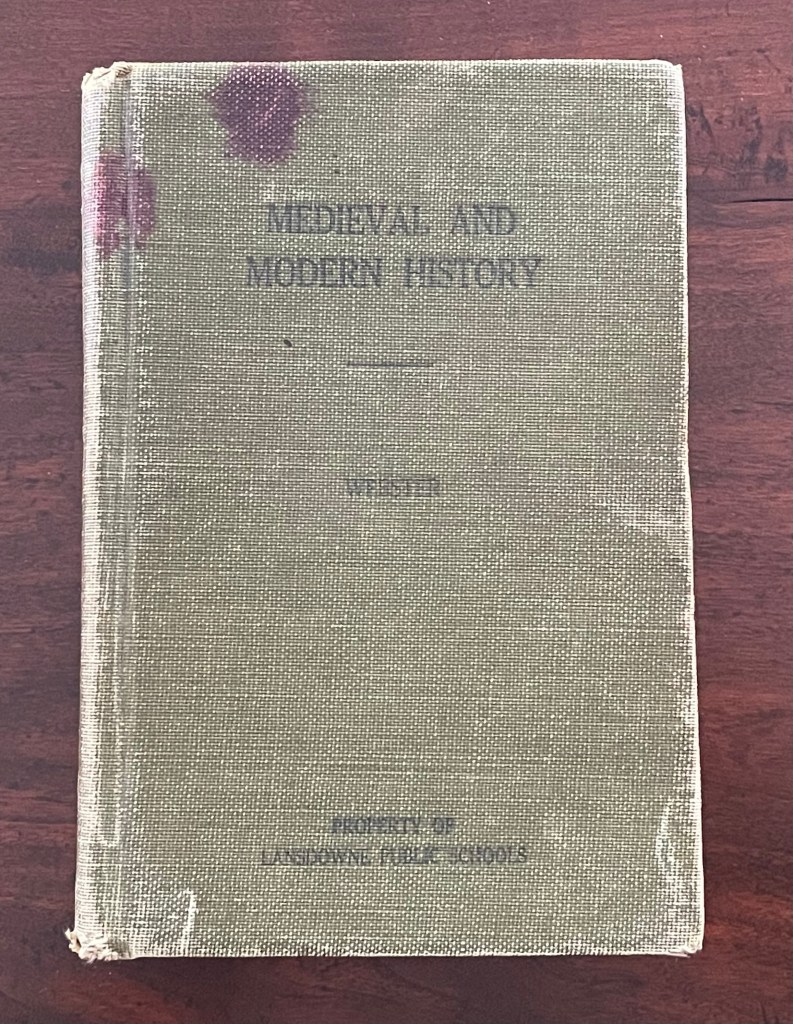

With Medieval and Modern History (Suggestions for Further Study for Jack Hroswith) (2013), a schoolboy’s textbook burnt into near illegibility but still accessible page by page, Linda Toigo adds an artist’s book that distinctively broadens the variety of alterations and their outcomes.

Medieval and Modern History (Suggestions for Further Study for Jack Hroswith) (2013)

Medieval and Modern History (Suggestions for Further Study for Jack Hroswith) (2013)

Linda Toigo

Altered casebound hardback. H195 x W135 x D40 mm. 832 pages. Unique. Acquired from the artist, 30 August 2025.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

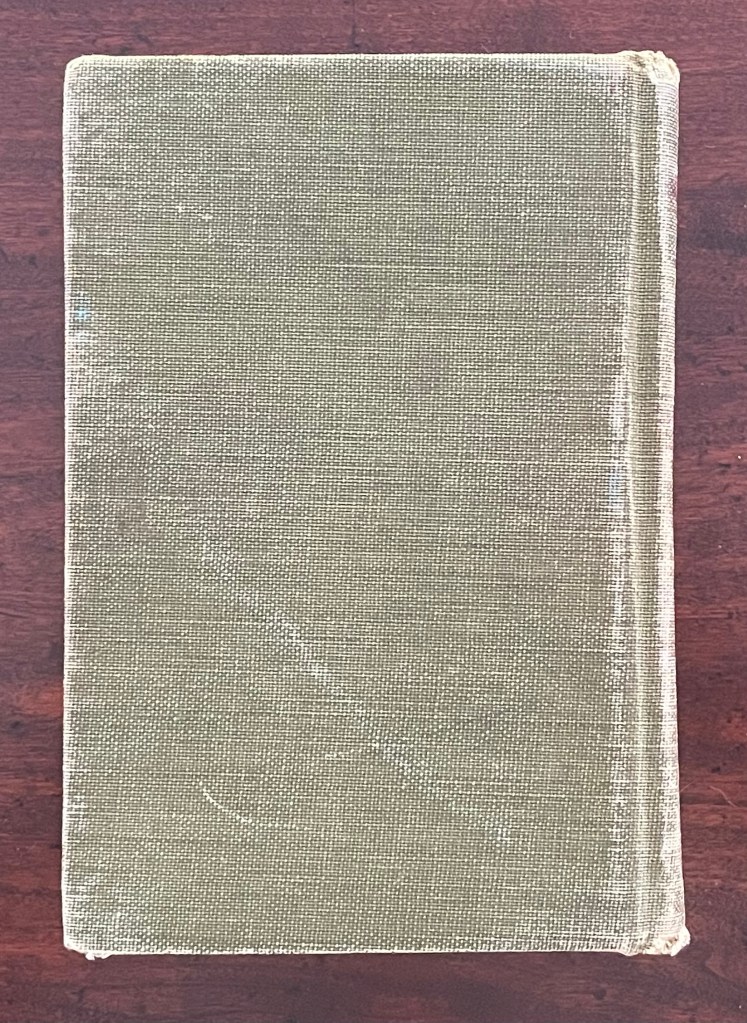

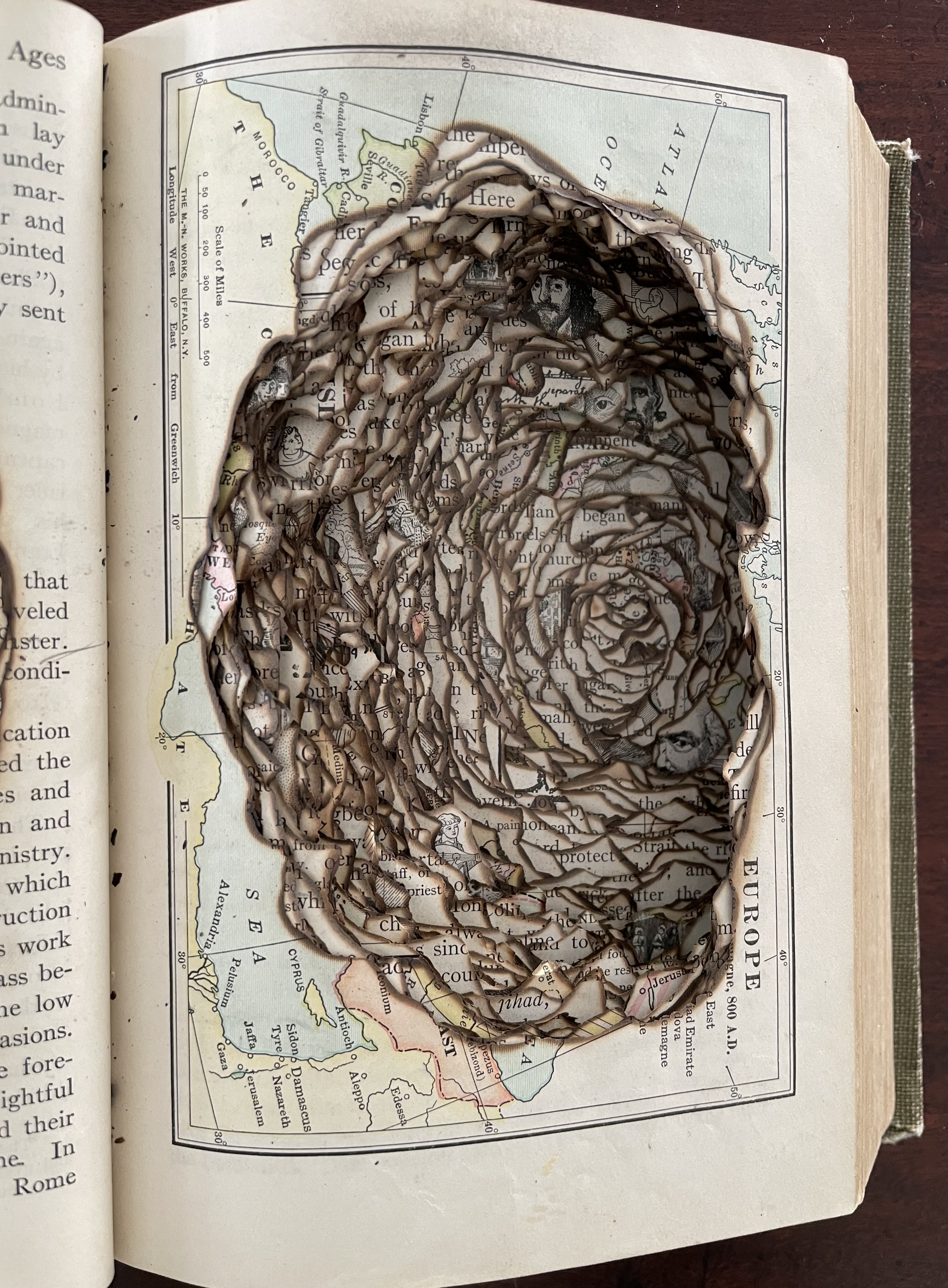

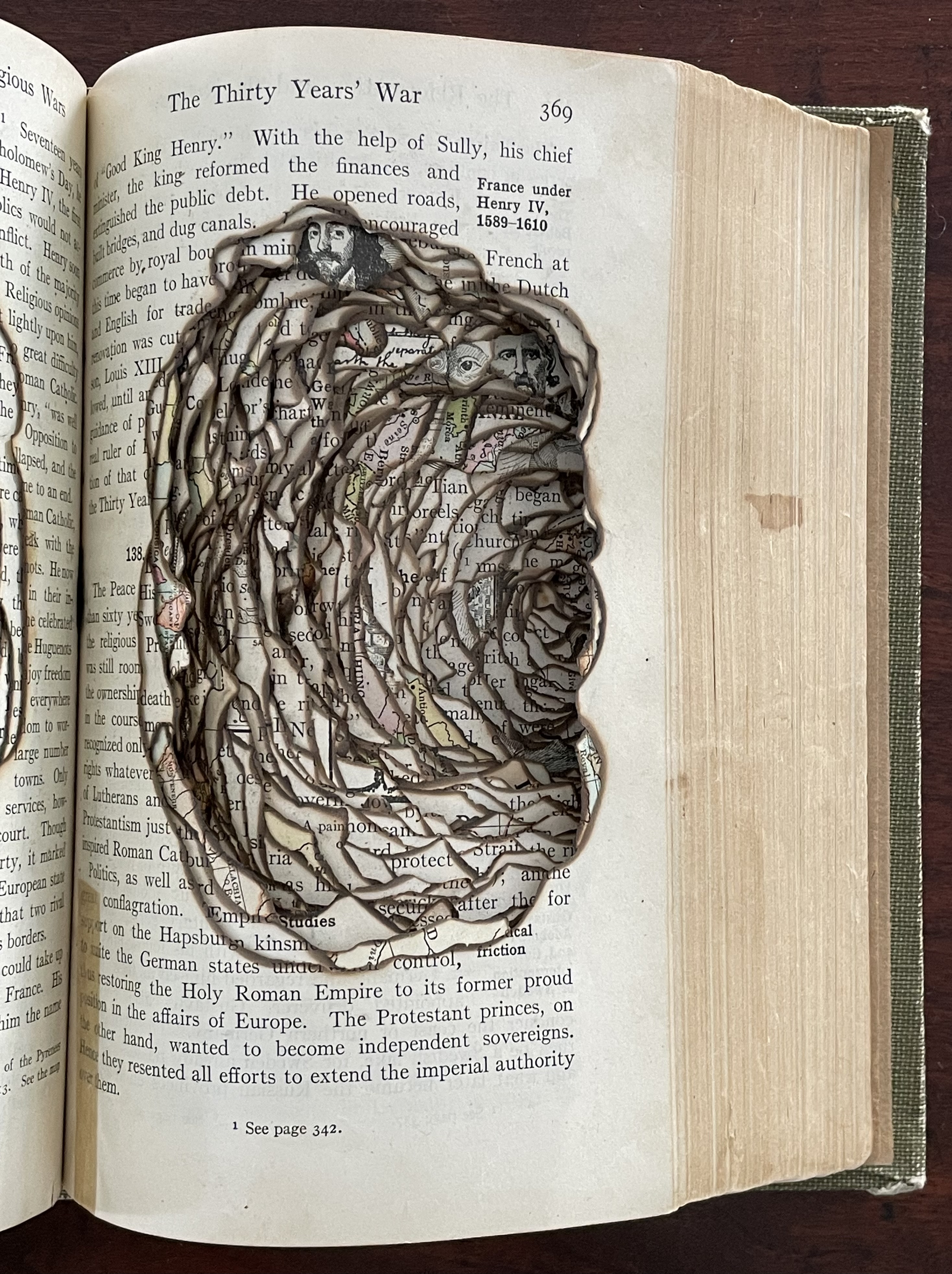

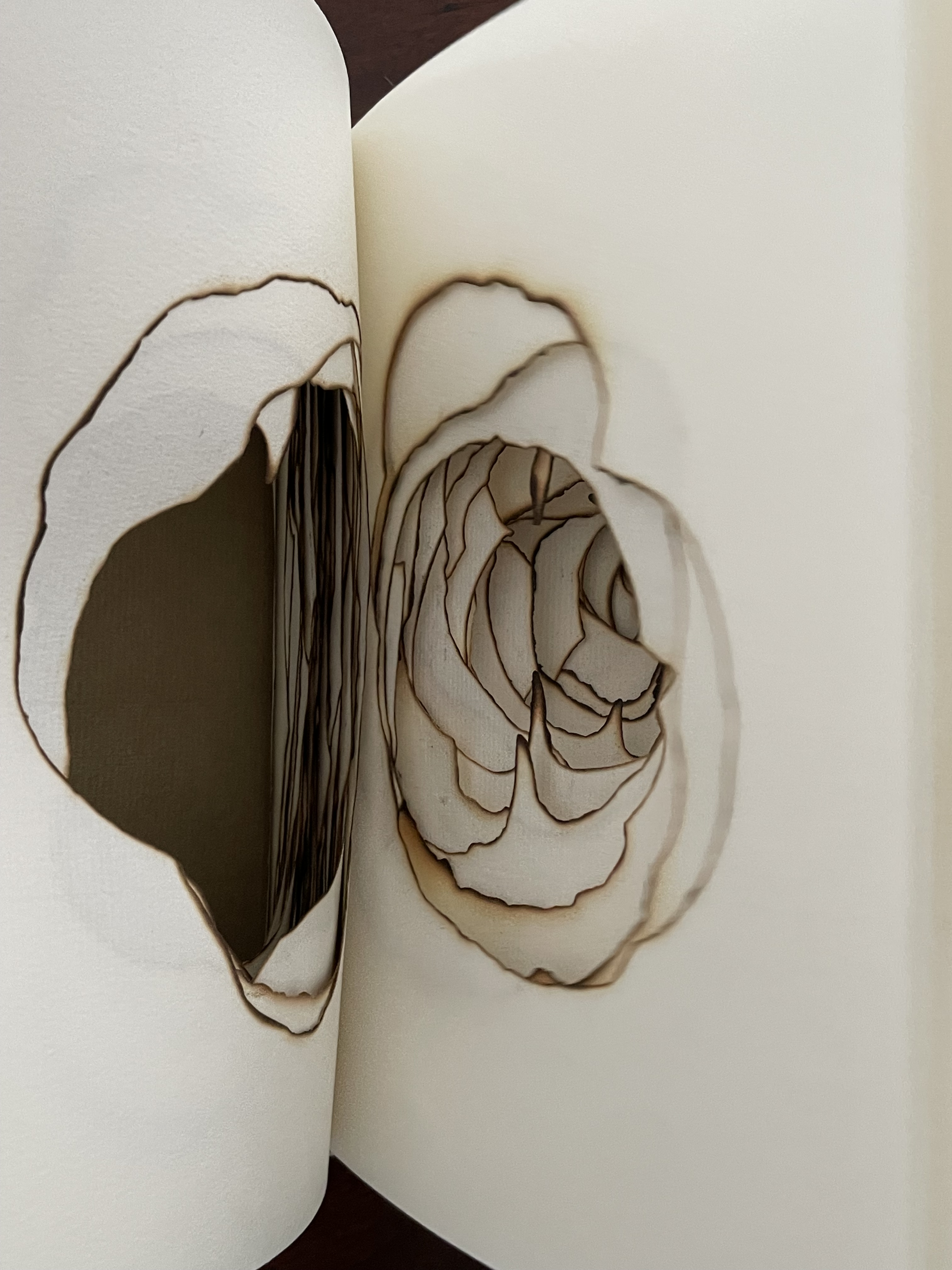

Toigo’s sly subtitle invites the contemporary reader to put on young Hroswith’s spectacles for a very different view — or rather many different views — of medieval and modern history. Her page by page pyrographic altering of Medieval and Modern History gives us an artist’s book that has left the altered book accessible page by page, its contents legible in the fragments surrounding the burnt-out sections, but illegible as a whole. Rather we are offered a new whole: one that offers new and multiple readings, multiple legibilities of the original book that can arise from Toigo’s artist’s book.

Different readings arise as the reader leafs through. What are we burning as we move through history?

While the map of Europe at the end of 1914 might imply that whatever we’re burning, we burn less of it as history progresses, the artwork’s other multiple aspects suggests that we peer deeply before coming to that conclusion. A more likely conclusion about not remembering the past can be drawn from the following double-page spreads and inside back cover.

Peering into the layers of the artist’s book at different points and from different angles can offer an ahistorical perspective. Bunched together, the burnt edges on the recto side look like the cave or tunnel of history. Or if we look to the verso, maybe it is the maw of history.

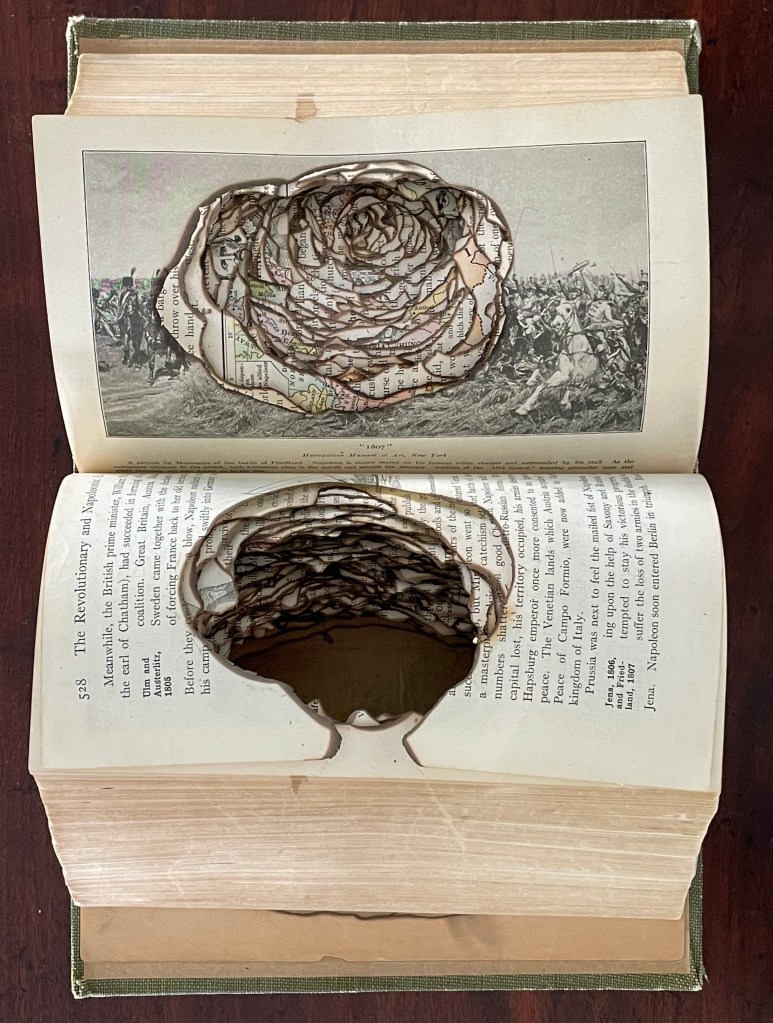

Or maybe the object of further study comes with the obliteration of scenes such as Napoleon’s victory in the Battle of Friedland, 1807, as depicted by Meissonier. Now an Ozymandias-like warning?

“1807” by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier

Metropolitan Museum of Art, online collection (Object ID 437052).

Or maybe the object of further study is the unease with juxtapositions of running heads and labels with a particular burnt out section such as this?

Toigo’s artist’s book interacts with its raw material in so many ways that it is almost like having 832 artworks in one. It makes a strong case for including book objects or book sculptures in any study and appreciation of artists’ books.

451 (2011)

451 (2011)

Linda Toigo

Casebound, painted cloth over boards. H218 x W164 x D30 mm. [220] pages consumed and shaped by a burning match. Unique. Acquired from the artist, 30 August 2025.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

While the burning of books has long been the subject of artworks, burning books into art is a more recent phenomenon.

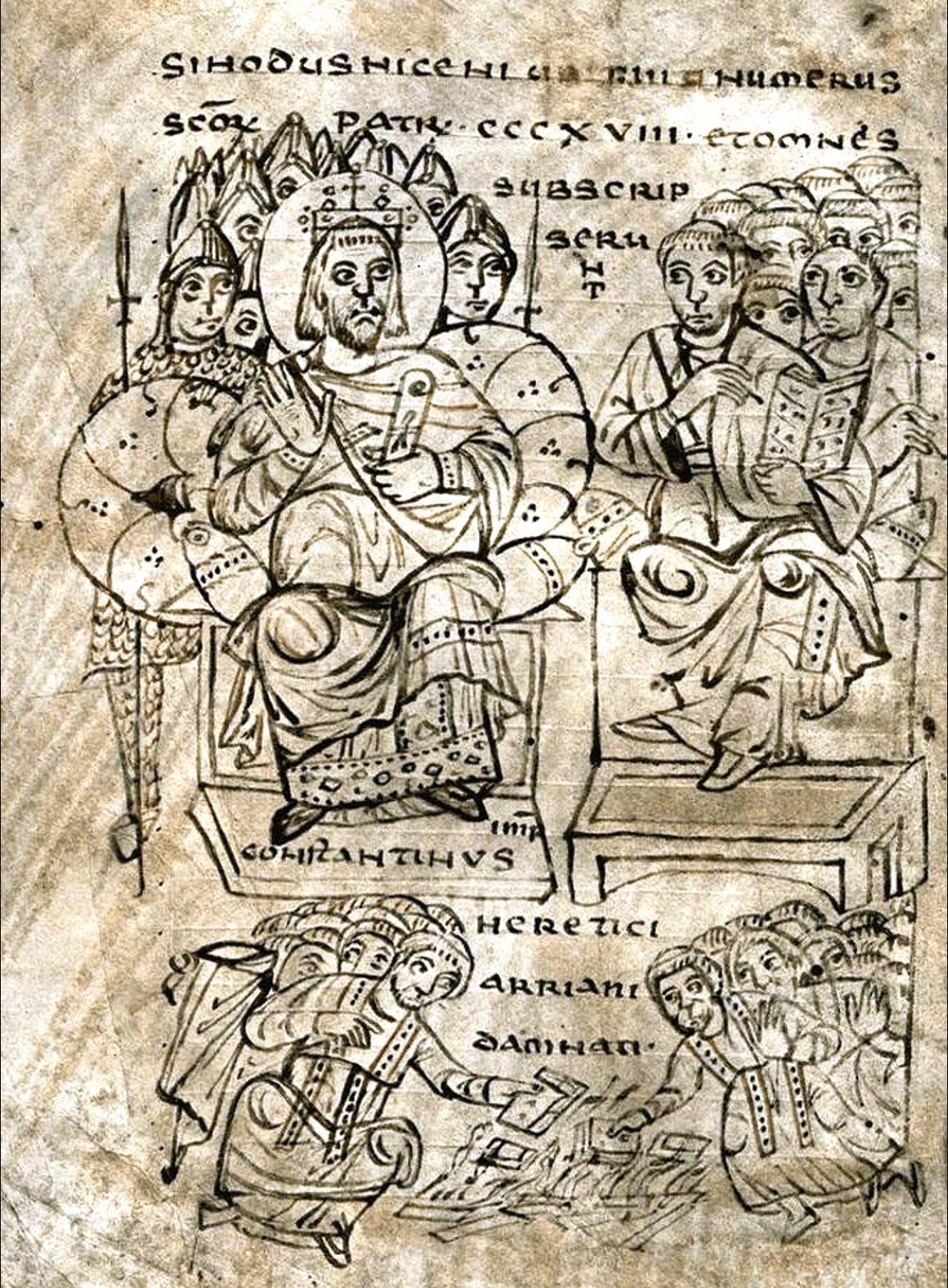

Emperor Constantine, the Council of Nicaea, and the burning of Arian books, drawing on vellum, from MS CLXV, Biblioteca Capitolare, Vercelli, a compendium of canon law produced in northern Italy (c. 825 CE); Saint Dominic and the Albigensians by Pedro_Berruguete (1445-1503), Prado; The Burning of the Books at Ephesus (detail) designed by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (c. 1530s), tapestry, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Killing the Scholars and Burning the Books, 210–213 BCE, Qin Dynasty, anonymous 18th century Chinese painted album leaf, Bibliothèque nationale de France; A procession to St. Mary’s Church, Cambridge, and the burning of Protestant books in Cambridge marketplace, etching by G. Terry (1710-67), Wellcome Collection.

Illustrated doublure in 451.

In 2015, the Fondation Calouste-Gulbenkian presented an exhibition with the title Pliure: Prologue (La

part du feu)” (“Fold: Prologue [The Share of the Fire]“). A curious title for the program, its only display room where it made some literal sense was the one showing Ed Ruscha’s Various Small Fires and Milk (1964). Reflected in the protective glass, Bruce Naumann’s Burning Small Fires (1968) could be seen — an early instance of burning a book (Ruscha’s Various Small Fires) into art. Also reflected was the screen showing François Truffaut’s adaptation of Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451, a contrary instance of burning books to make art.

Display of Ed Ruscha’s Various Small Fires and Milk, 1964

Pliure: La Part du Feu, 2 February – 12 April 2015, Paris, Fondation Calouste-Gulbenkian.

Photo by Robert Bolick, 11 April 2015.

Reflected in the lower left hand corner is the display of Bruce Nauman’s Burning Small Fires, 1968; in the upper right corner, a film clip of Truffaut’s 1966 Fahrenheit 451; and in the upper left, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s La bibliotheque en feu, 1974.

Toigo has noted the influence of Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive Art manifesto from the 1960s and sequences from Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 on her work:

The starting reference for [Medieval and Modern History] has been Auto-Destructive Art, a concept developed in the ’60s by Fluxus member Gustav Metzger, based on “Destroy, and you create”, the idea of shaping a work of art through a disintegrative process: in his first public demonstration, the German artist and activist hid behind a glass surface across which was stretched a sheet of Nylon. The artist then sprayed a hydrochloric acid solution to the fabric, that gradually dissolved creating a glue-like coating on the glass through which Metzger slowly became visible. … I gave chance a prominent role: with the same morbid fascination that inspired the fire officer in Fahrenheit 451, I let fire burn its way on the pages, and I observed the devastation of words, maps and illustrations. At the same time, however, I kept a certain level of control on the destructive process developing a quick reaction to avoid the complete dissolution of the book: for every page I waited for the fire to reach a chosen sentence or a specific image before pushing the paper down onto a glass surface with my fingertips. (Toigo, 2013)

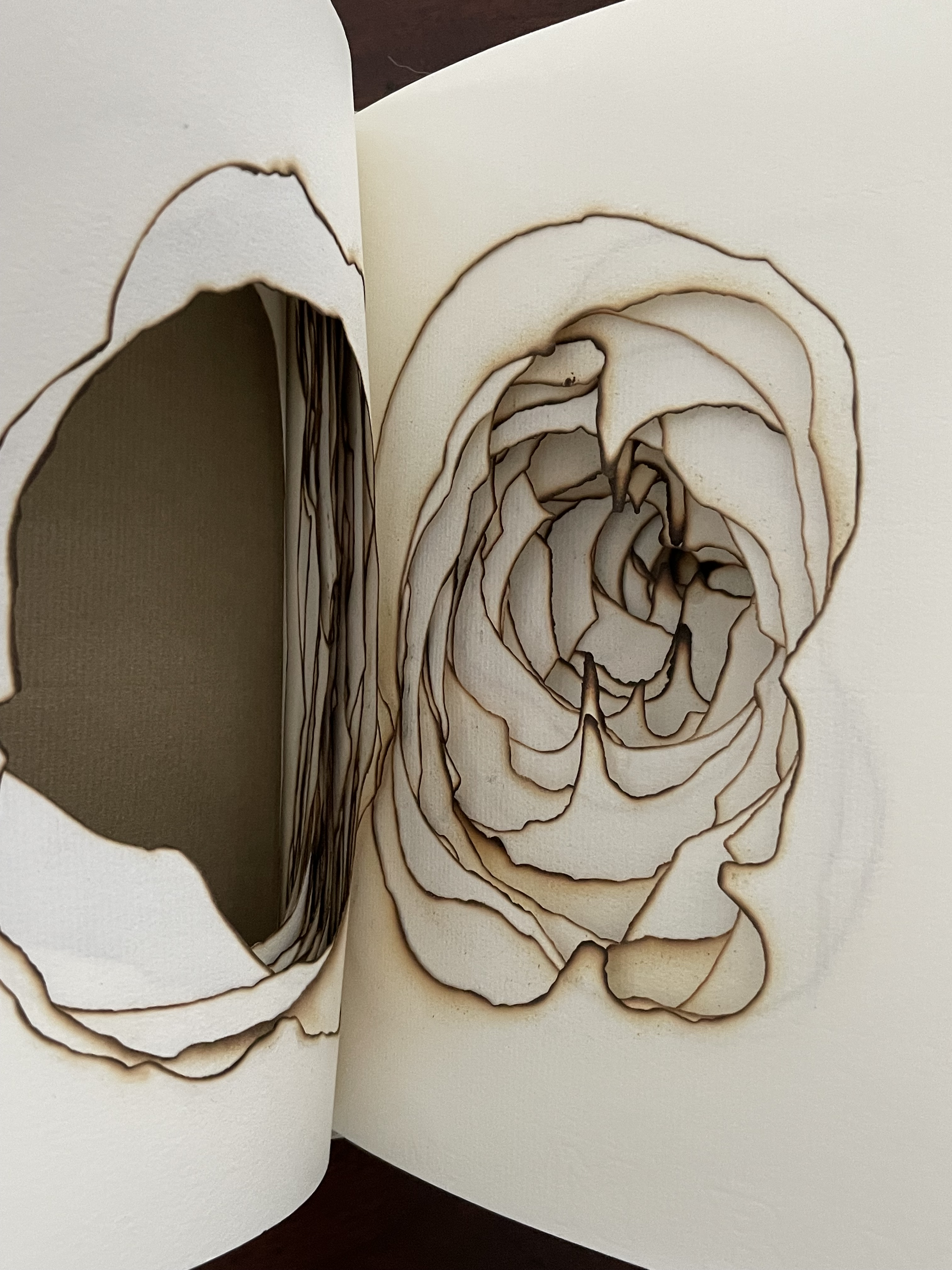

This technique of using lit matches, a glass surface and her fingers to burn, excavate and sculpt the pages differs from the more usual pyrographic techniques involving purpose-made tools. Perhaps knowing that prompts a sympathetic sense of tactility as Medieval and Modern History and 451 are explored, or perhaps it is the care required not to dislodge any of the burnt edges.

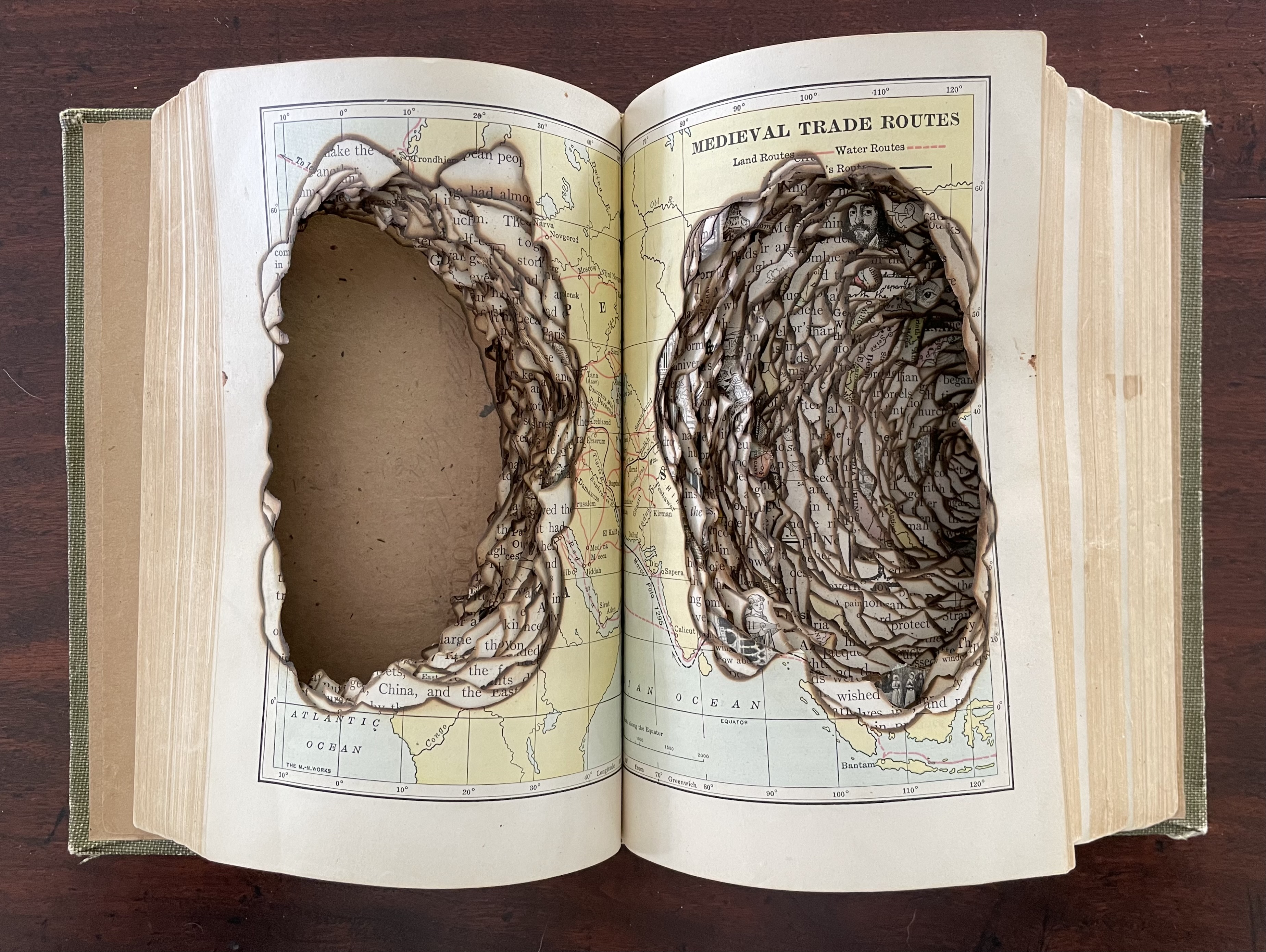

In 451, the burnt edges create a different abstract drawing on each page. It is peculiar to perceive the lines of a drawing tangled in those on the pages beneath it and then perceive them mid-air on either side of the folio as it turns. Any loss of the burnt edge on a page would detract from its graphic effect.

Even though the tangled “lines” seen when looking into the depths of 451 offer a striking effect, its very tight binding does not lend the work to the sculptural views possible with Medieval and Modern History‘s lay-flat binding and more supple paper. The very different results the artist has achieved in these two works with the same pyrographic technique, enhanced by binding choice for 451, is admirable.

Alongside Linda Toigo, other book artists who have played with fire include

- John Latham (Skoob Towers, 1966)

- Bernard Aubertin (Livre brulé, 1974)

- Doug Beube (Books of Knowledge Standing Up against the Elements, 1983-89)

- Ann Hamilton (Tropos, 1993)

- Jacqueline Rush Lee (Ex Libris: Endoskeleton, 1998)

- Raphael Vella (Oubliette, 2003)

- Anselm Kiefer (Für Paul Celan : Aschenblume, 2006)

- Cai Guo-Qiang Danger Book: Suicide Fireworks, 2007)

- Antonio Riello (Ashes to Ashes, 2009~)

- Donna Ruff (Spreads of Influence, 2010)

- Egidija Čiricaitė (Damnatio Memoriae, 2011)

- Fiona Dempster (Beyond Bombs and Burning, 2015)

- Jaz Graf (Trophic Avulsions, 2016)

- Ines Seidel (Manifesto, 2016)

Further Reading and Viewing

“Doug Beube“. 21 April 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Jonathan Safran Foer“. 8 November 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Jaz Graf“. 10 July 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Guy Laramée“. 18 September 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Jacqueline Rush Lee“. 8 October 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Buzz Spector“. 24 Setember 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Carolyn Thompson“. 19 December 2023. Books On Books Collection.

Dworkin, Craig Douglas. 2003. Reading the Illegible. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press.

Galpin, Richard. 1998. Erasure in Art: Destruction, Deconstruction, and Palimpsest. Accessed 7 September 2025.

Kiefer, Anselm. 2015. Anselm Kiefer : L’alchimie Du Livre. Edited by Marie Minssieux-Chamonard. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France : Éditions du Regard.

Toigo, Linda. 7 April 2013. ““Destroy, and you create”: an Auto-Destructive History lesson for Jack Hroswith”. Lindo Toigo website. Accessed 25 May 2018.

Vella, Raphael. 2006. The Unpresentable : Artistic Biblioclasm and the Sublime. University of the Arts London.