Craig Mod modulates on margins here in Medium (18 August 2014).

Text printed on the best paper with no margins or unbalanced margins is vile. Or, if we’re being empathetic, sad. (For no book begins life aspiring to bad margins.) I know that sounds harsh. But a book with poorly set margins is as useful as a hammer with a one inch handle. Sure, you can pound nails, but it ain’t fun. A book with crass margins will never make a reader comfortable. Such a book feels cramped, claustrophobic. It doesn’t draw you in, certainly doesn’t make you want to spend time with the text….

On the other hand, cheap, rough paper with a beautifully set textblock hanging just so on the page makes those in the know, smile (and those who don’t, feel welcome). It says: We may not have had the money to print on better paper, but man, we give a shit. Giving a shit does not require capital, simply attention and humility and diligence. Giving a shit is the best feeling you can imbue craft with. Giving a shit in book design manifests in many ways, but it manifests perhaps most in the margins.

Reiterating his point by analogy, Mod channels the late designer George Nakashima: “in order to produce a fine piece of furniture, the spirit of the tree must live on. You give it a second life … You can make an object that lives forever, if used properly.

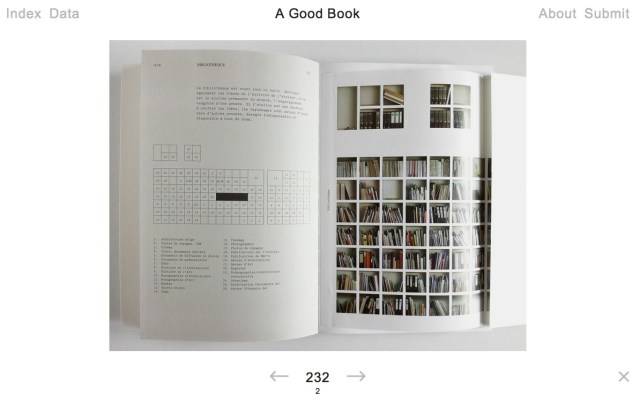

For the fundamentals underlying Mod’s scatologically and poetically emphatic truth, you cannot find much better than Alexander Ross Charchar’s essay on the craft and calculations of “page canons” by Villard de Honnecourt (13th century!) , J.A. Van de Graaf, Raúl Rosarivo and Jan Tschichold: “The Secret Law of Page Harmony“. Most delightful is Charchar’s dynamic diagram “The Dance of the Four Canons” illustrating the workings of each page canon:

Copyright 2010, Alexander Ross Charchar.

The Further Reading suggested by Charchar and his commenters is excellent, and I would only add Marshall Lee’s Bookmaking. For those who are irritated with the imposition of the print paradigm on the digital reading experience, there is a useful pointer to applying the page canons to website design that will cause a rethink of that irritation and equally make the imposers think harder as well.

For those who care about the book, what it is evolving into and the role that heart, mind and design still play in that process, read Charchar’s”The Secret Law of Page Harmony” –again and again.