When it comes to acquiring skills and professional training in book publishing, from the early days of the printing press onwards, learning by doing has been book publishing’s order of the day. Consider the following interview exchange between Mac Slocum (Tools of Change) and Theodore Gray (The Elements):

.

MS: What skills — or people with those skills — must be incorporated into the editorial process to produce something like the iPad/iPhone editions?

TG: Specifically in the case of “The Elements,” the skills required were writing, commercial-style stills photography, Objective-C programming, and a whole, whole lot of Mathematica programming to create the design and layout tool and image processing software we used to create all the media assets that went into the ebook.

Other ebooks might well require different skills. My next one, for example, is going to include a lot more video, so we’re gearing up to produce high-grade stereo 3D video. That’s one of the challenges in producing interesting ebooks: You need a wider range of skills than to produce a conventional print book.

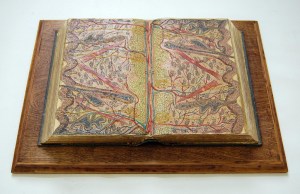

Starting out in book publishing late in the last century, a novice would have consulted Marshall Lee’s Bookmaking and the Chicago Manual of Style to learn the basics of design, editorial and production. If it were Trade publishing that beckoned, a familiarity with A. Scott Berg’s biography of Maxwell Perkins (“Editor of Genius”) would have been likely.

If scholarly book publishing, then Harman’s The Thesis and the Book, Turabian’s A Manual for Writers and maybe Bailey’s The Art & Science of Book Publishing.

But as with the acquisition of print publishing skills through learning by commissioning, designing, editing, printing, marketing and selling, the acquisition of the skills required for ebook publishing could use a hand up from appropriate resources. People like Joshua Tallent, Joel Friedlander, Liz Castro, Craig Mod, Matthew Diener are those resources — either by example or authoring — and novices today would do well to start bookmarking their output.

For notes on the availability of formal training and career conditions in publishing, see Thad McIlroy’s The Future of Publishing.

Related sources:

“Joshua Tallent of Ebook Architects on the State of Digital Publishing,” Bill Crawford, Publishing Perspectives

“Understanding Fonts & Typography,” Joel Friedlander, The Book Designer

html, xhtml, and css: 6th edition, Elizabeth Castro

“Our Future Book,” Craig Mod

“Resources,” Matthew Diener, David Blatner and Anne-Marie Concepcion, ePUBSecrets

The Chicago Manual of Style Online