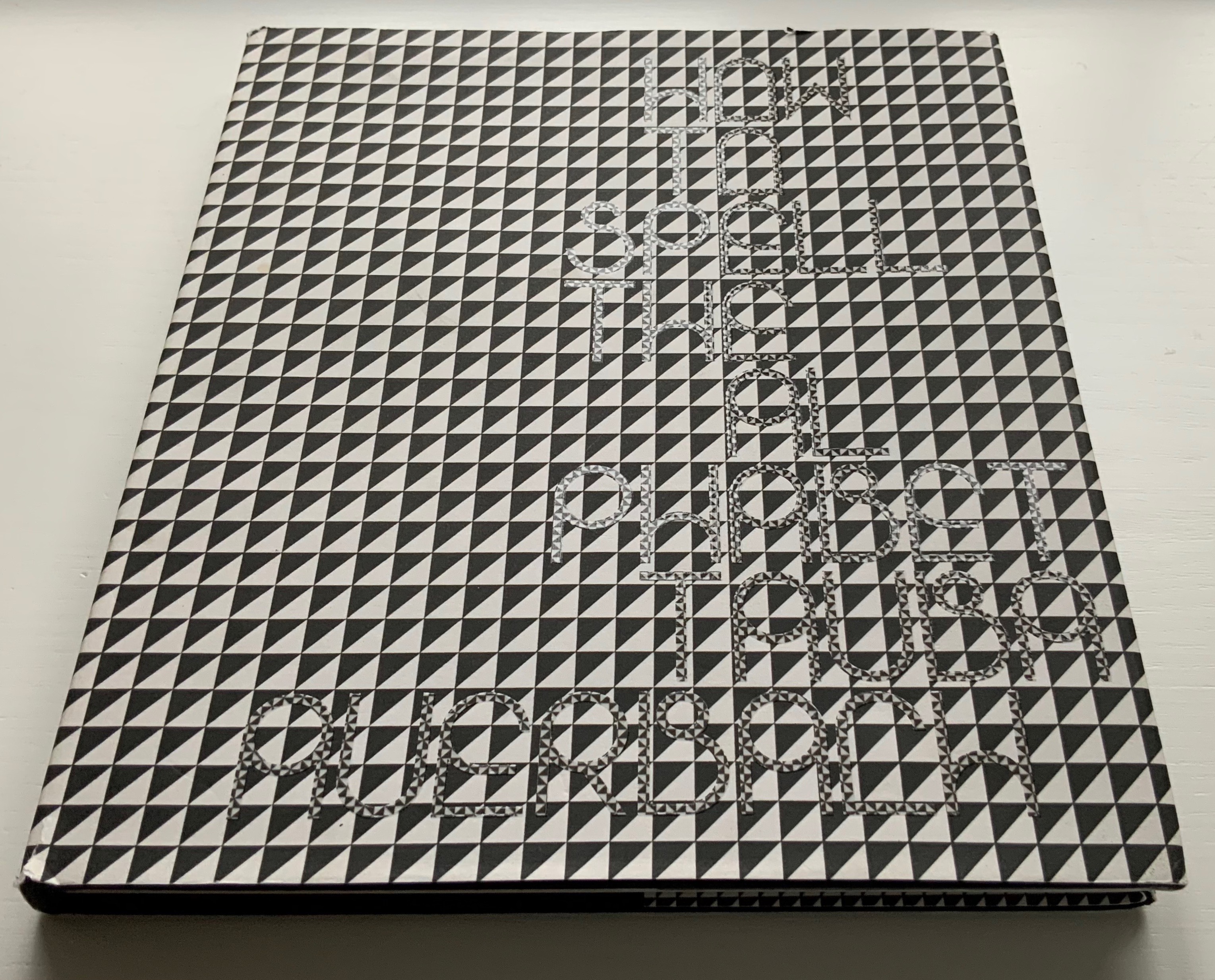

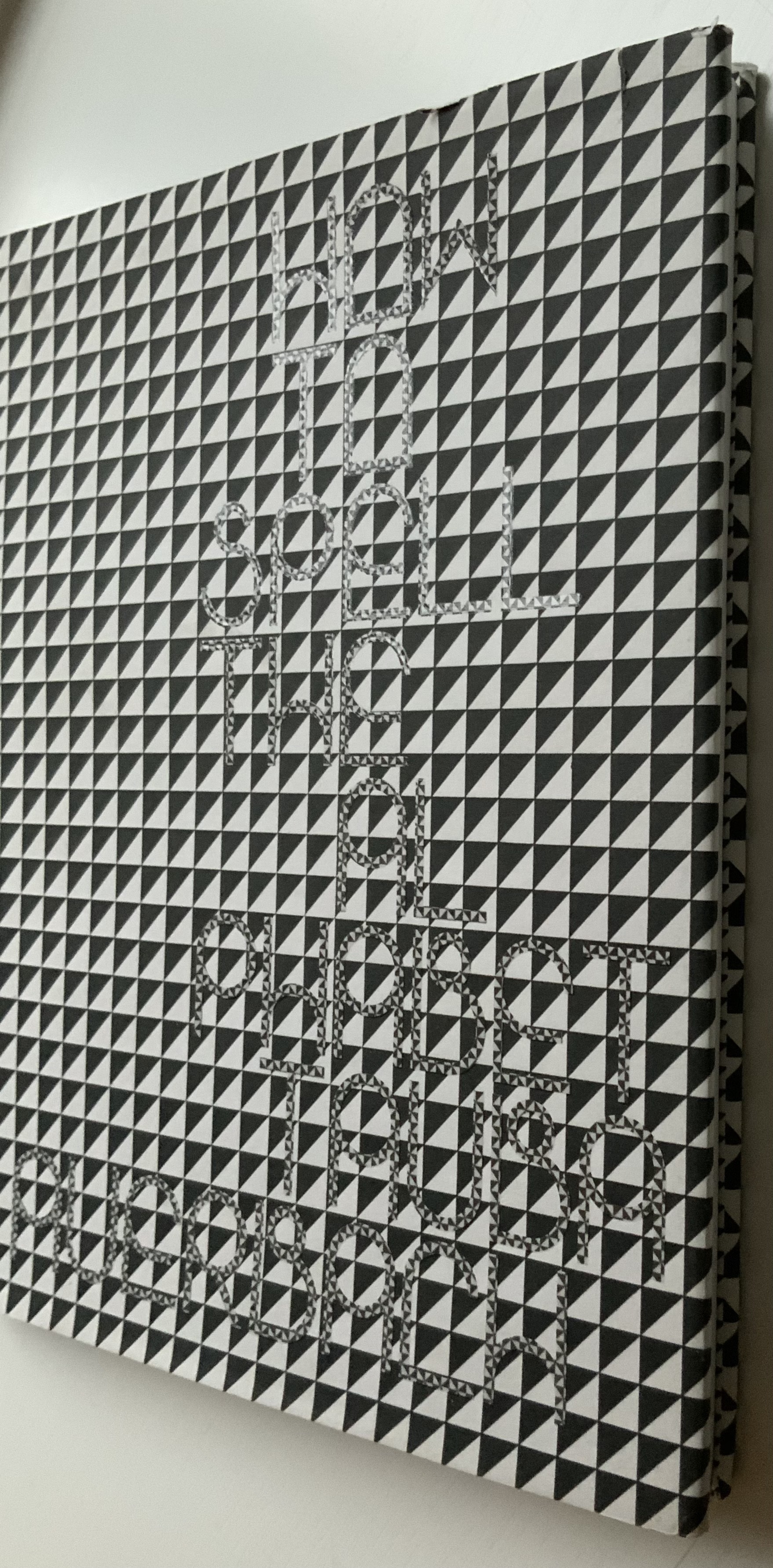

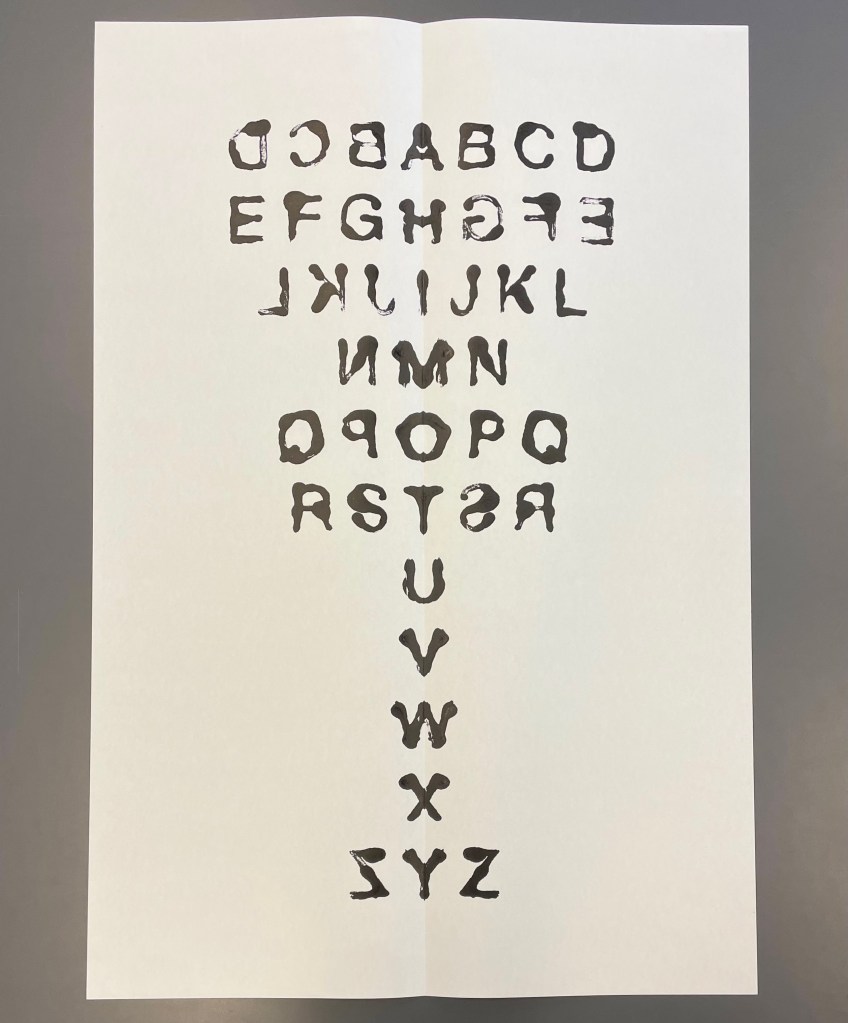

Mis-en-pli (2016)

Mis en pli (2016)

Étienne Pressager

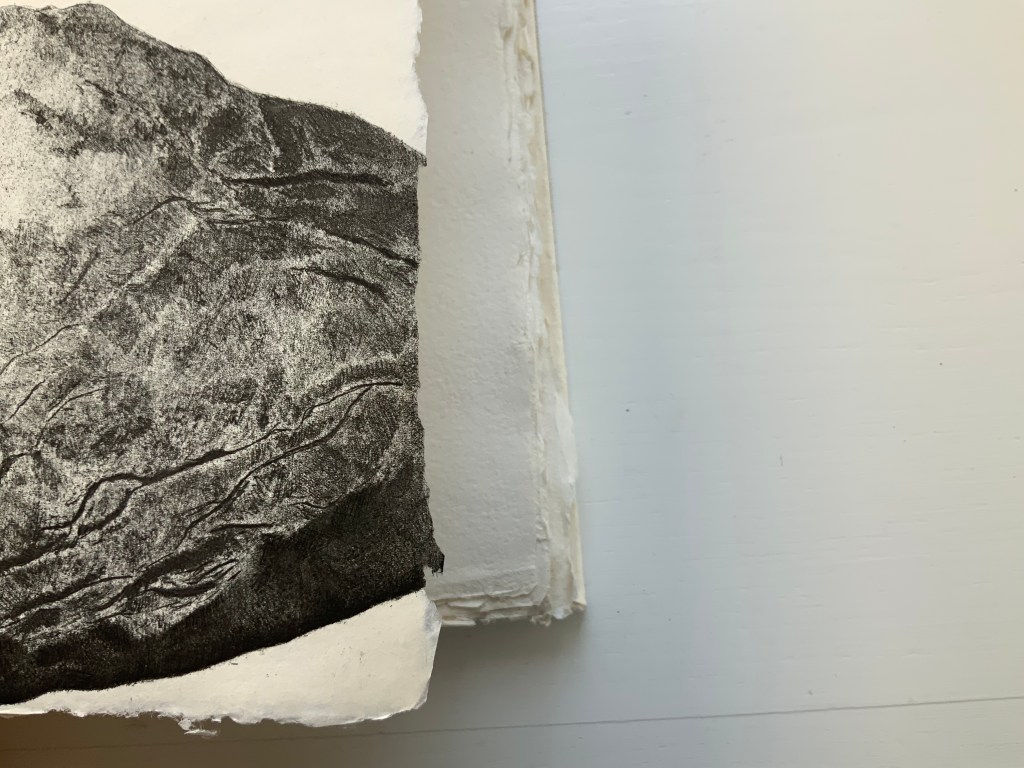

Monotype, inked, folded in half lengthwise and unfolded. H840 xW570. Edition of 16, of which this is #12. Acquired from the artist, 22 April 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection, and courtesy of the artist. Displayed with permission of the artist.

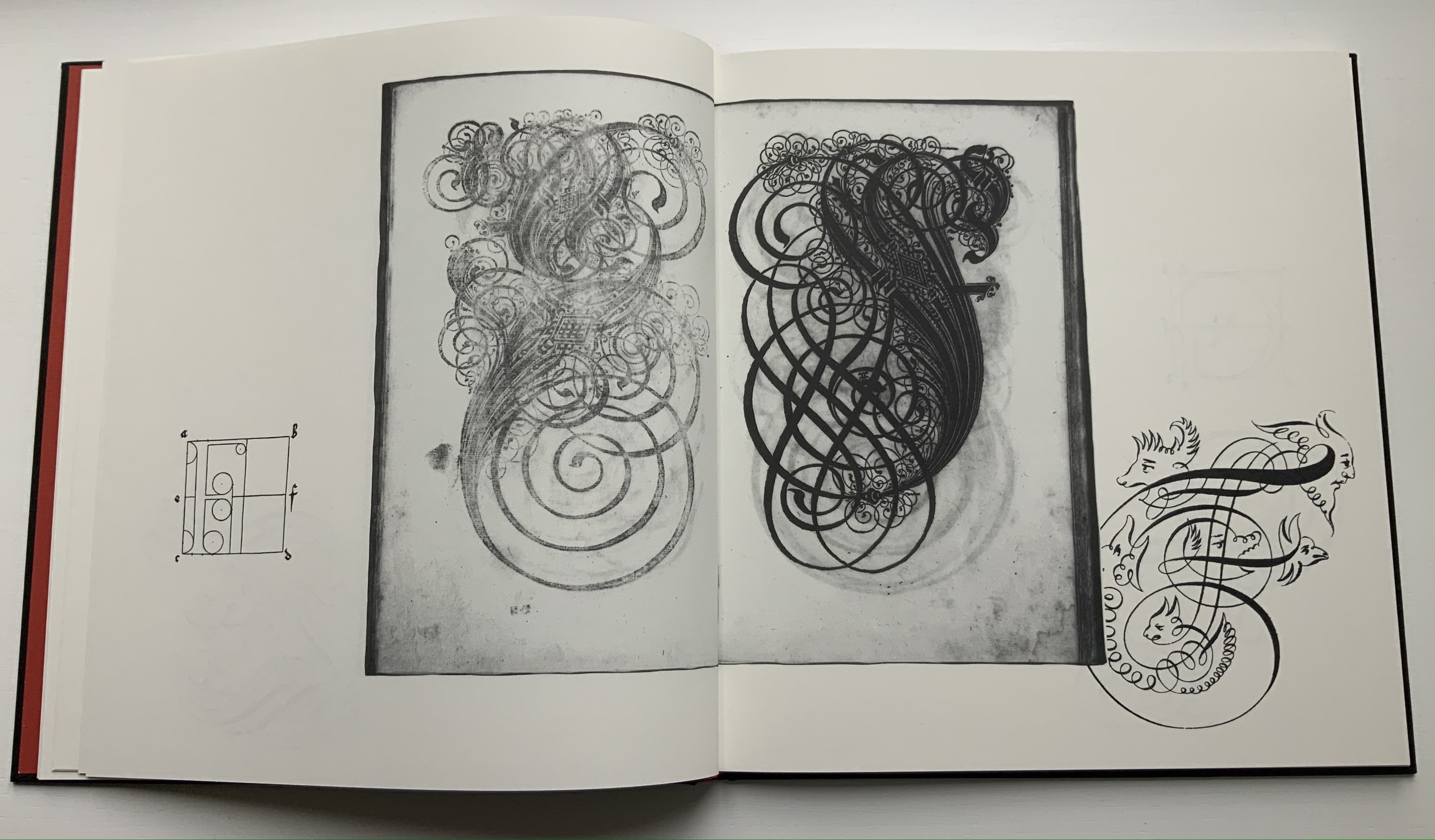

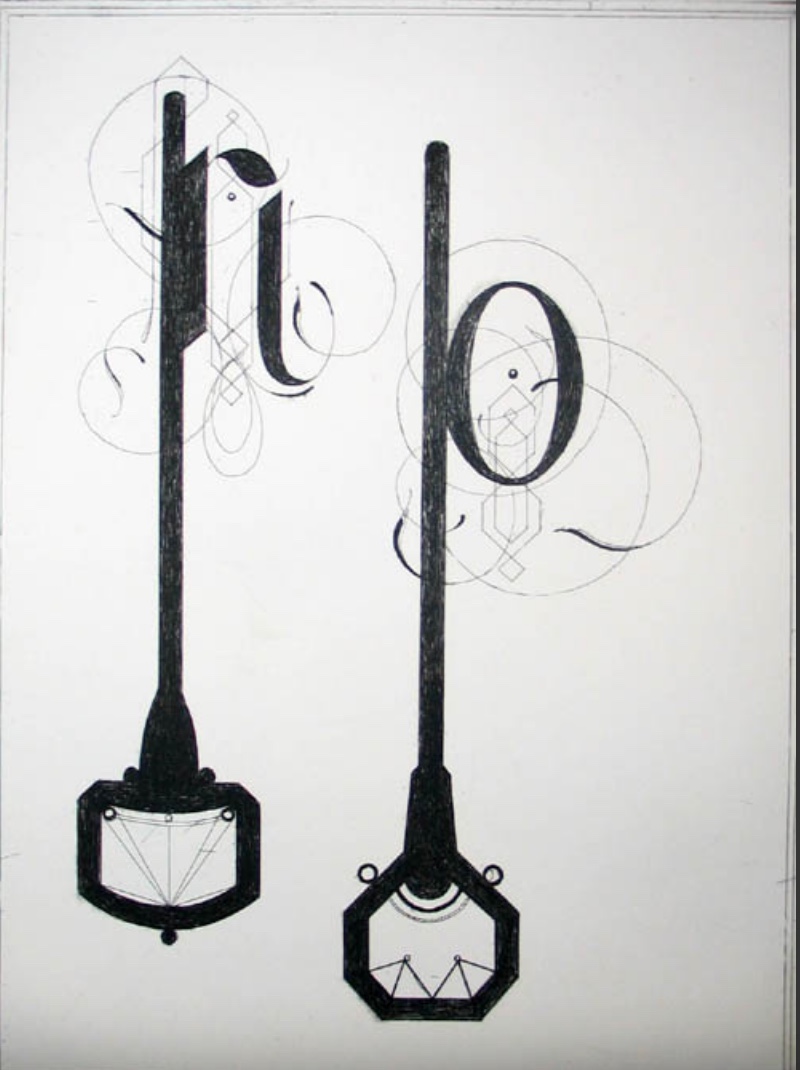

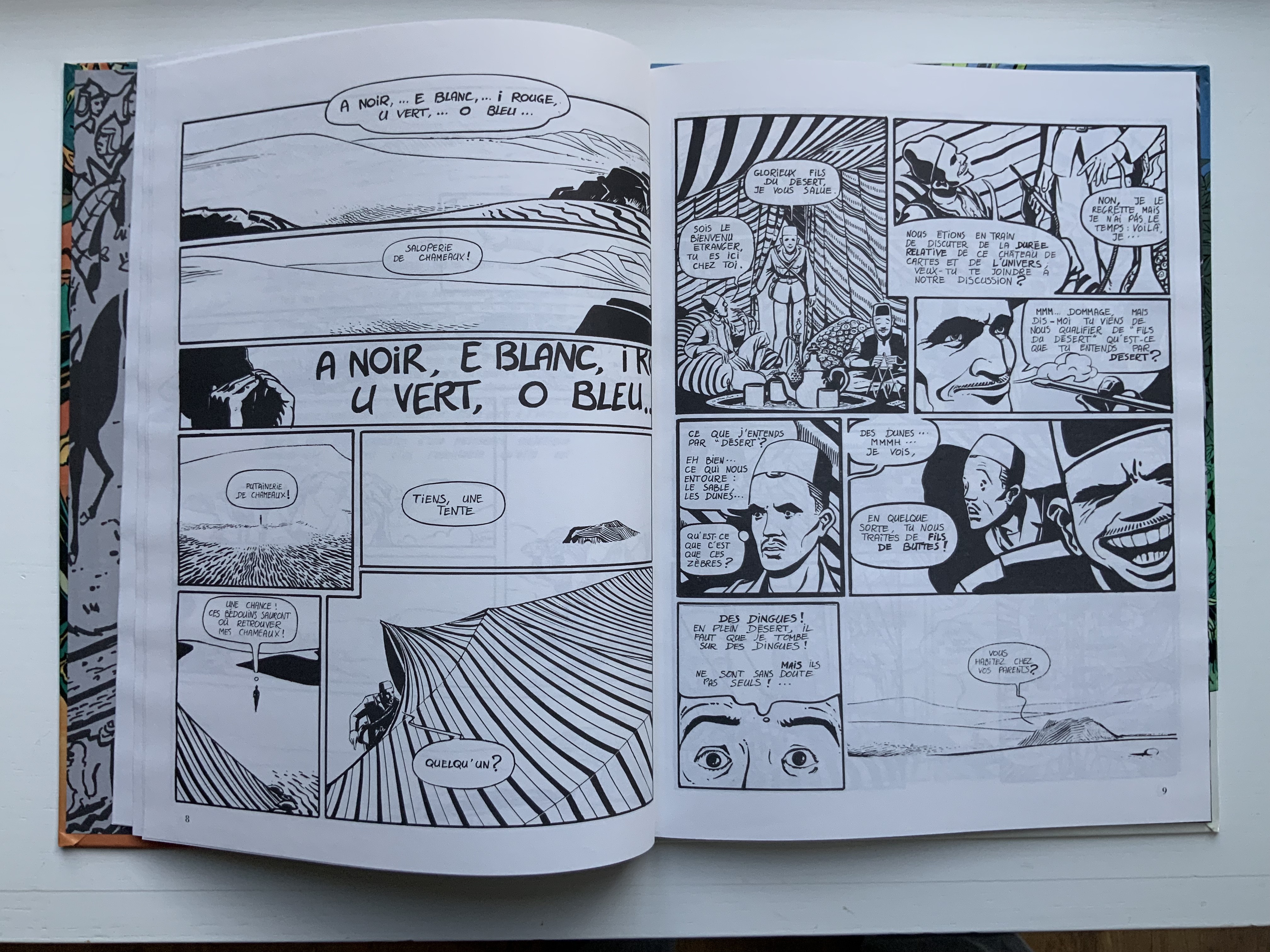

The alphabet loves a mirror, and like many artists’ books that comment on themselves or the Book, Étienne Pressager’s monotype is self-regarding — in its process, its result and its title. A large sheet is folded lengthwise and unfolded. Ink is arranged just so in the center and to the right. The sheet is folded, pressed and unfolded to reveal the mirrored alphabet. Voilá, a single-fold book. Mis en pli or “Set in fold”.

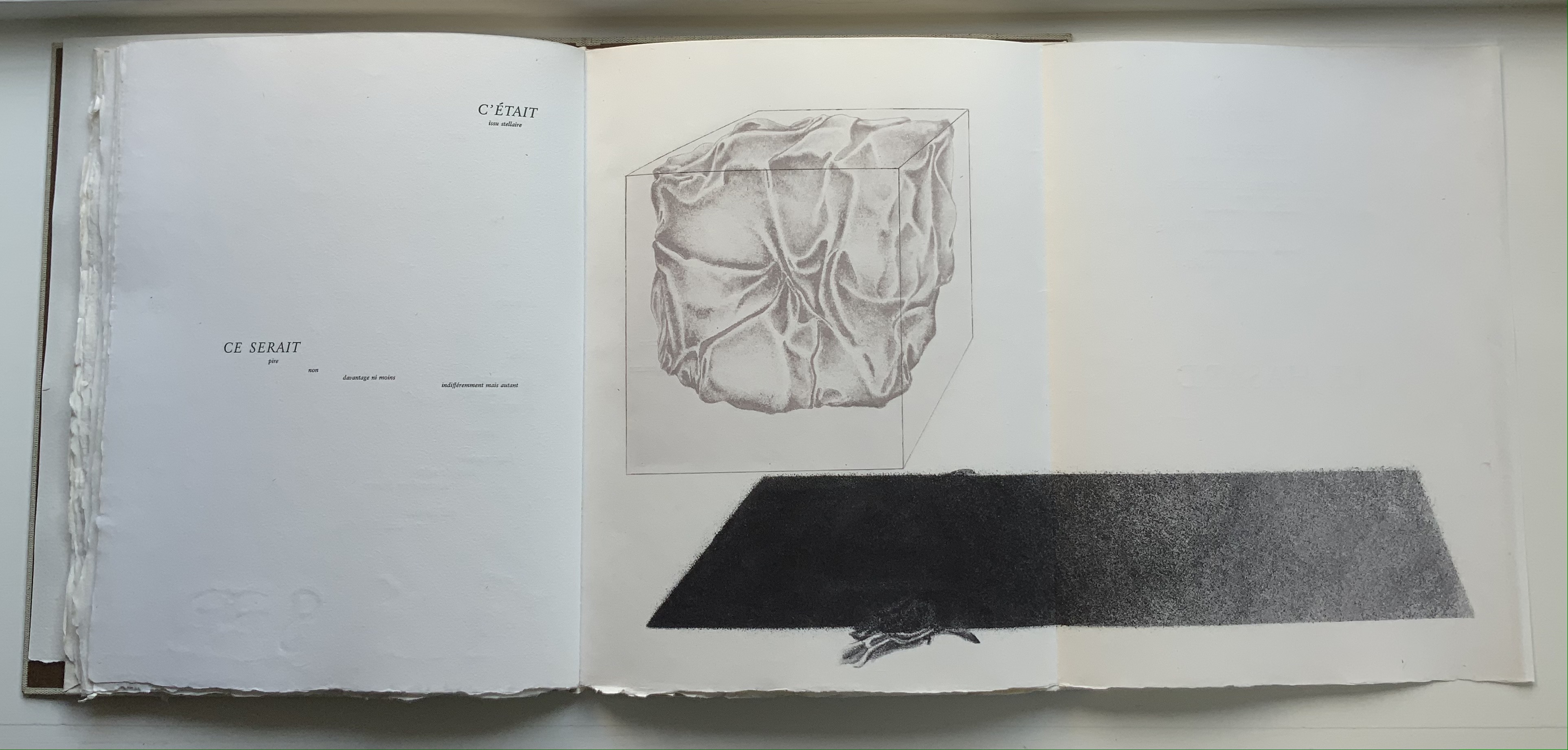

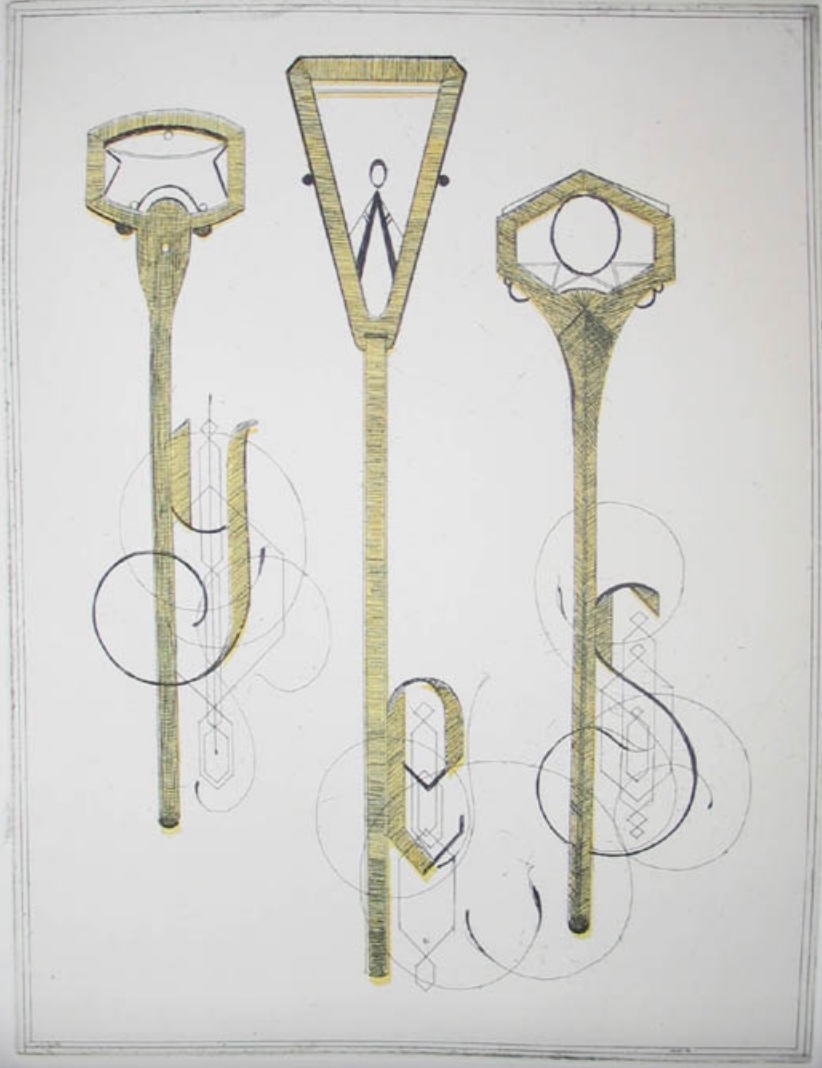

Quelques îles en formation (2007)

Quelques îles en formation (2007)

Étienne Pressager

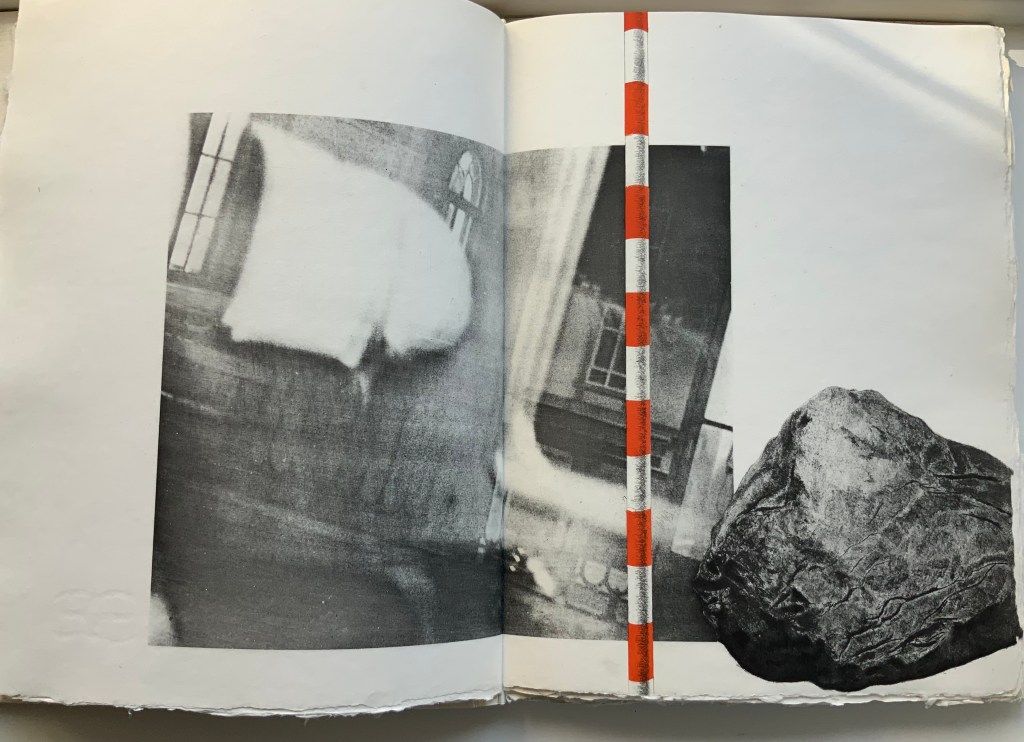

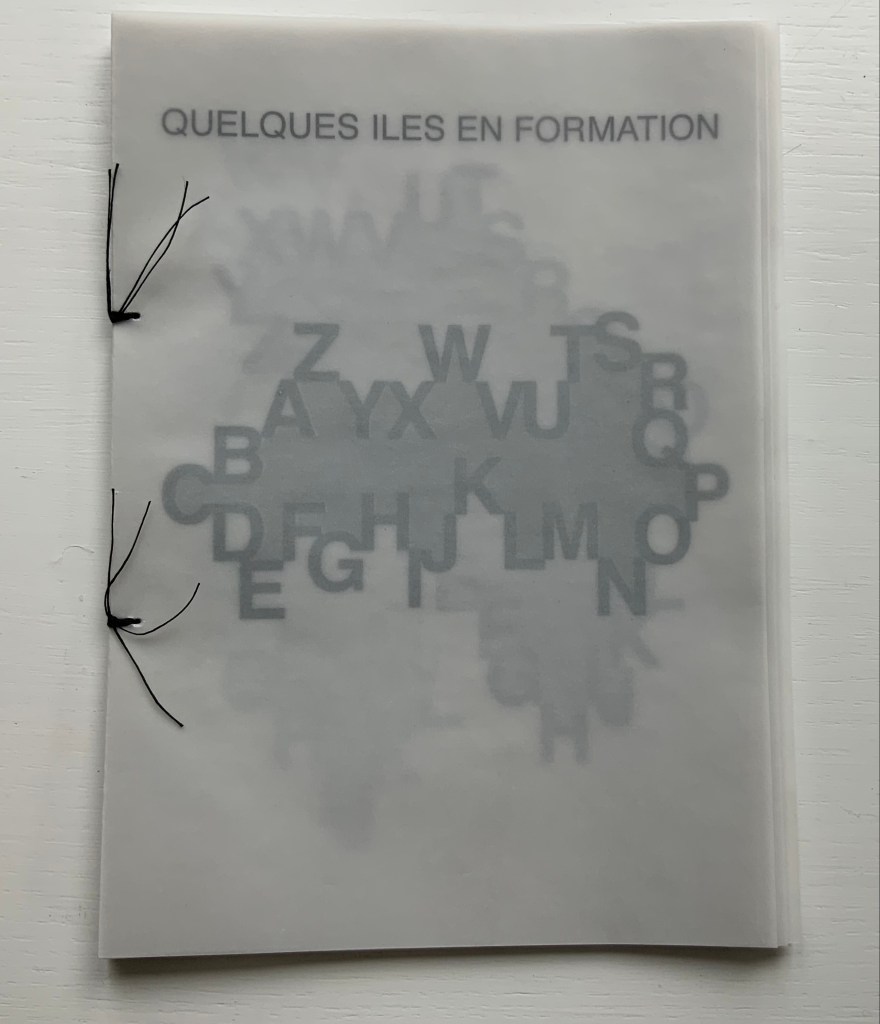

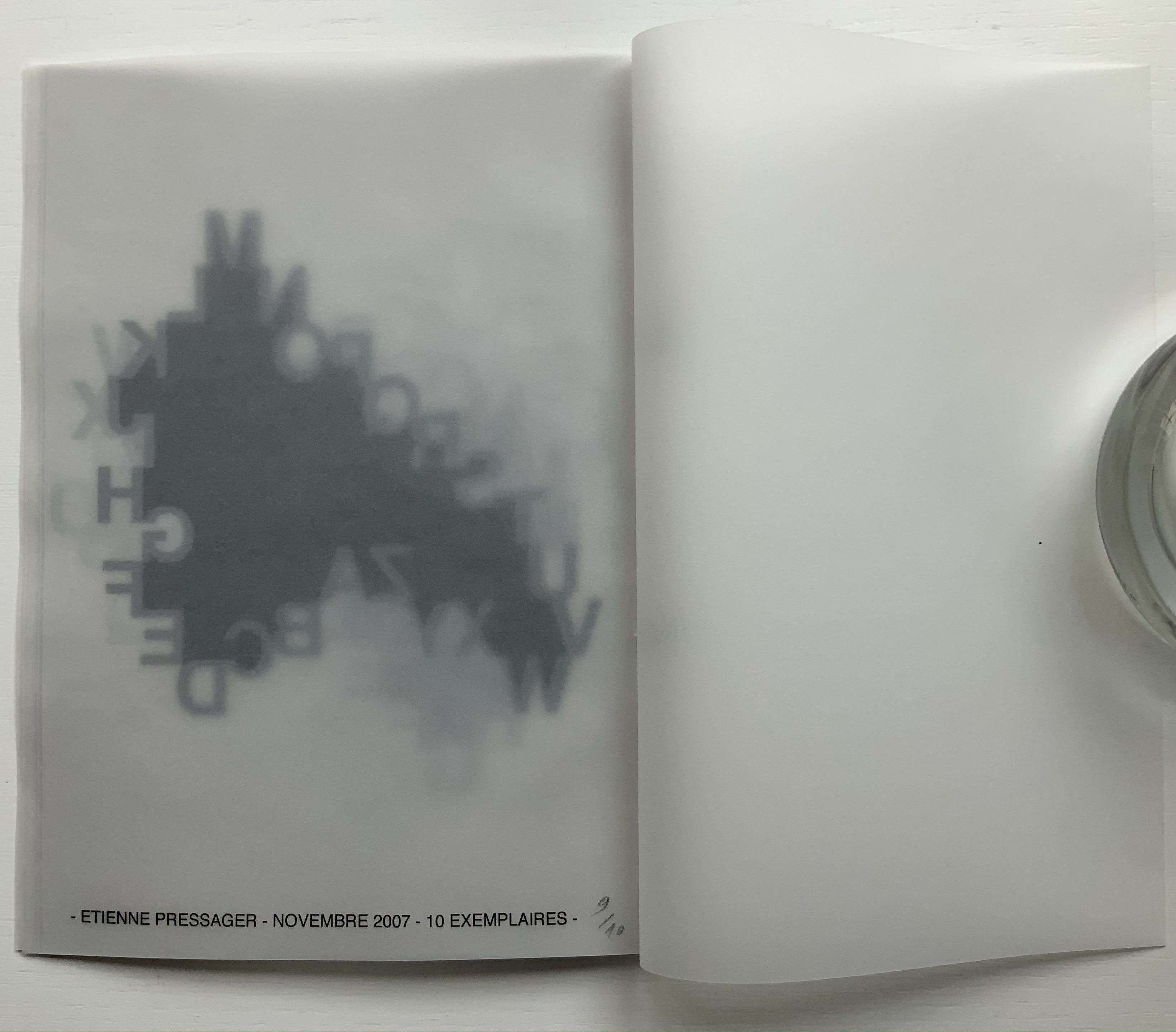

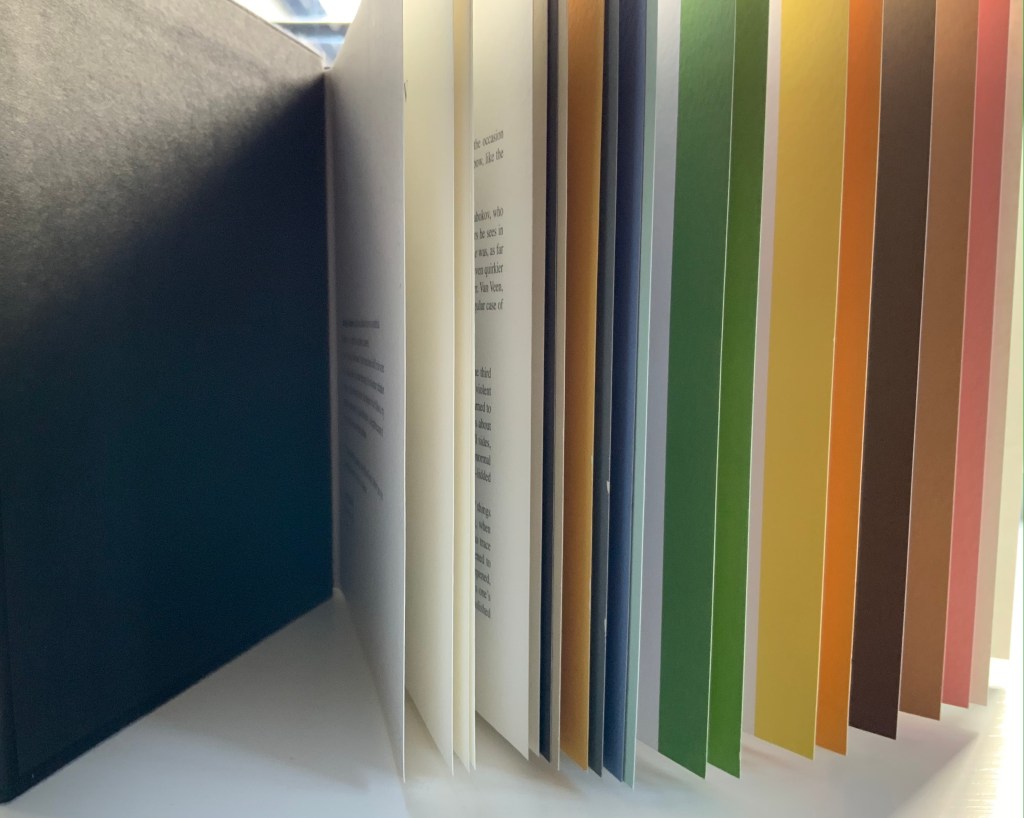

Handsewn booklet. H210 x W170 mm, 30 pages. Edition of 10, of which this is #9. Acquired from the artist, 8 March 2022. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

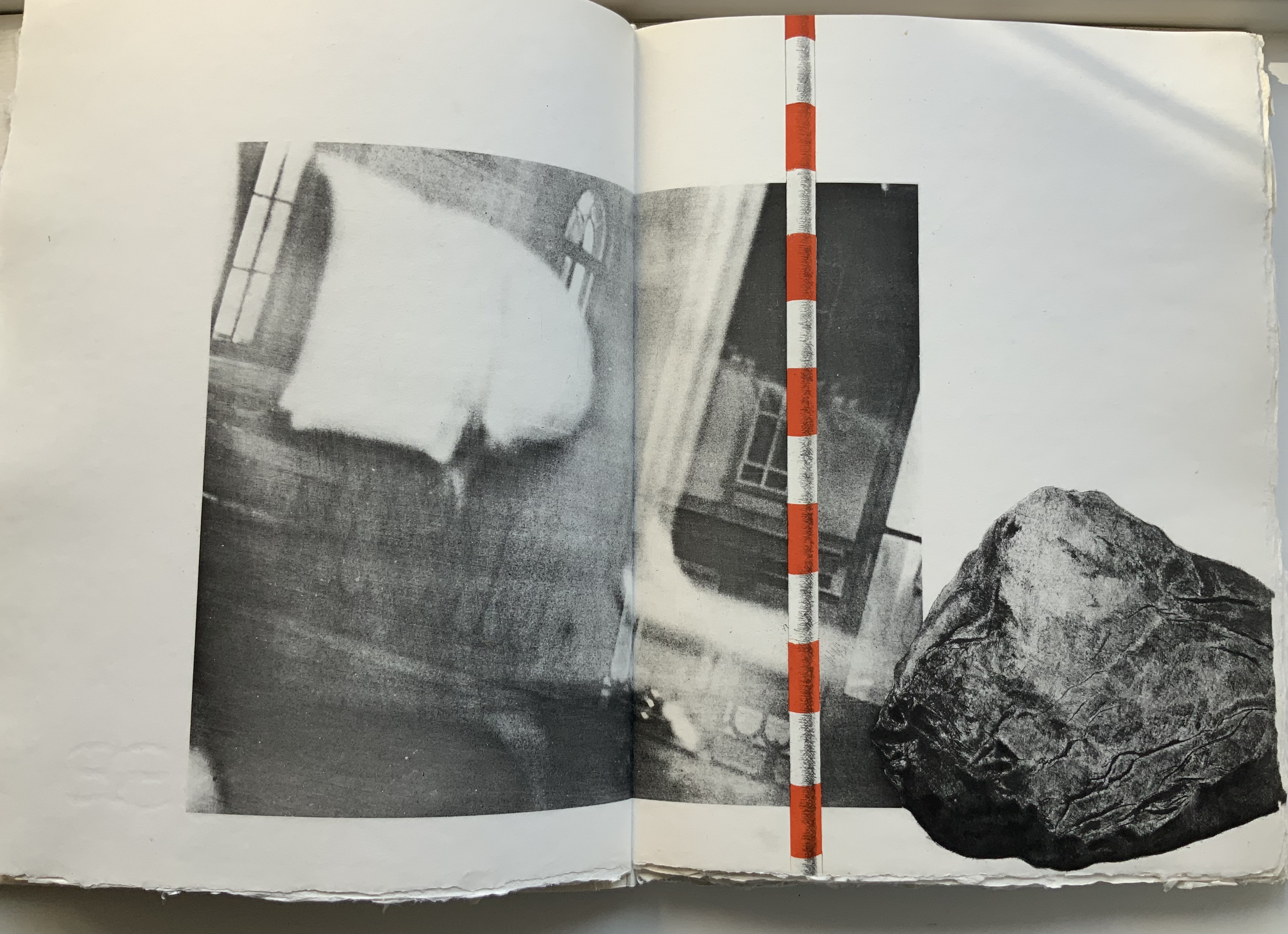

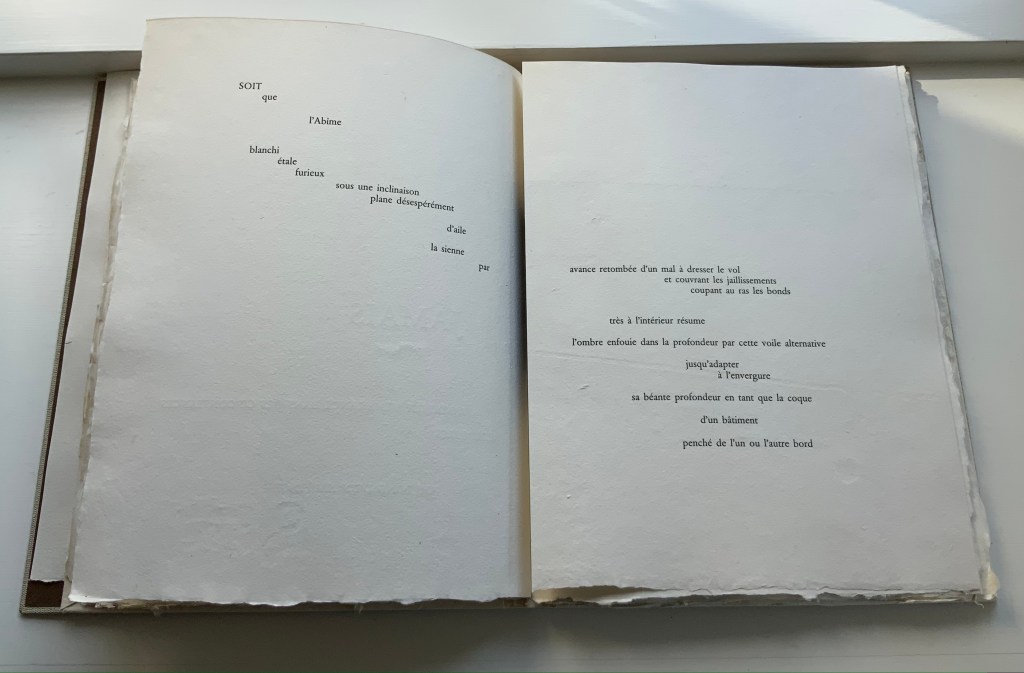

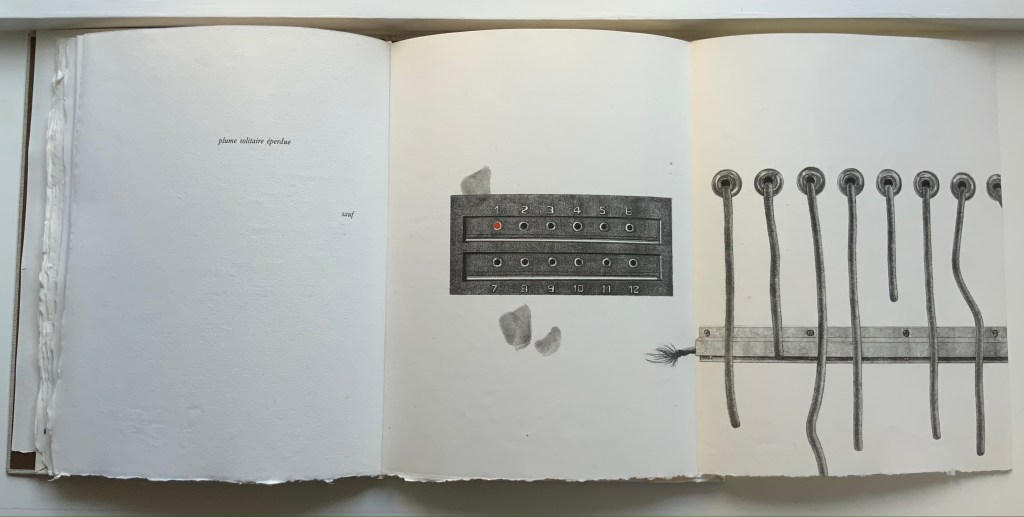

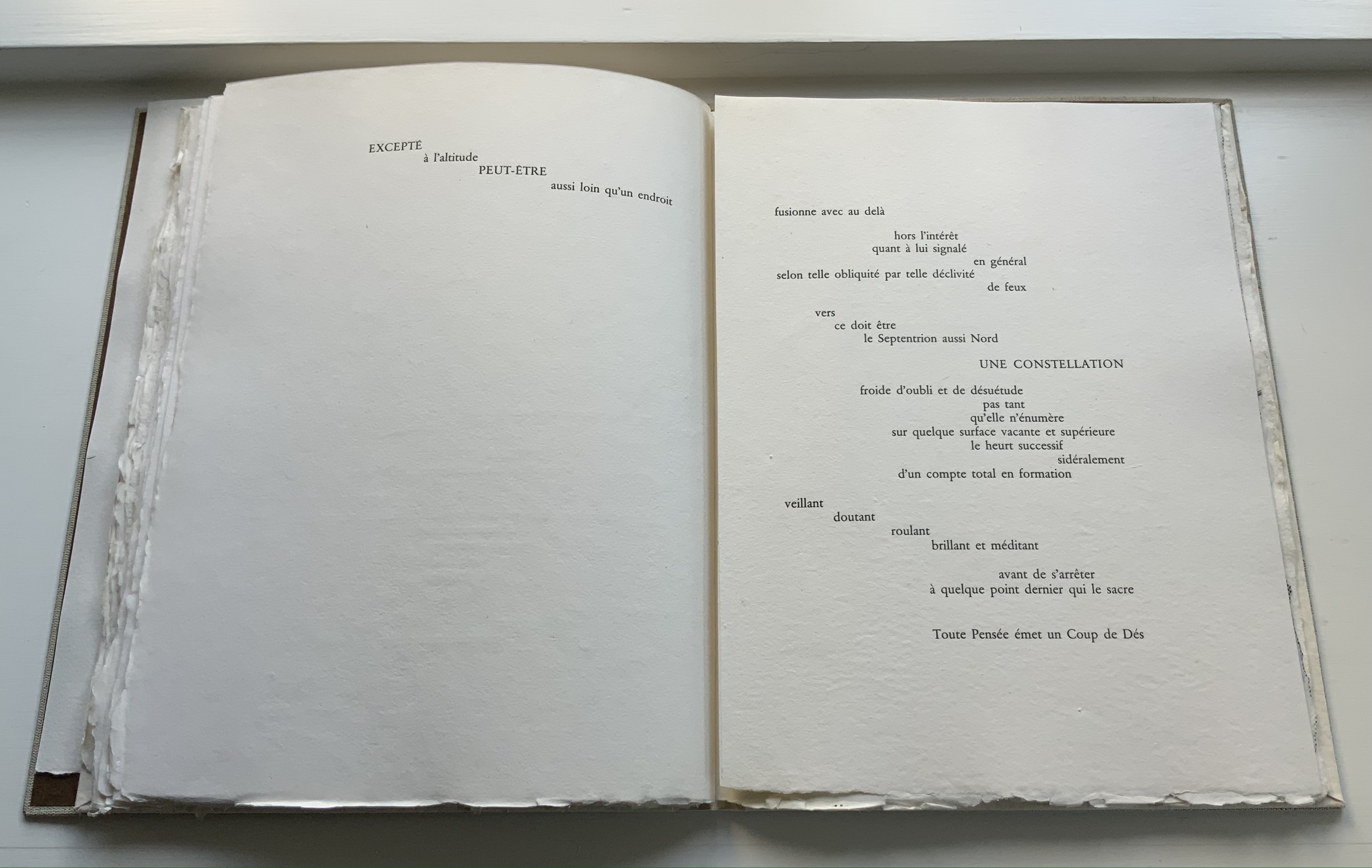

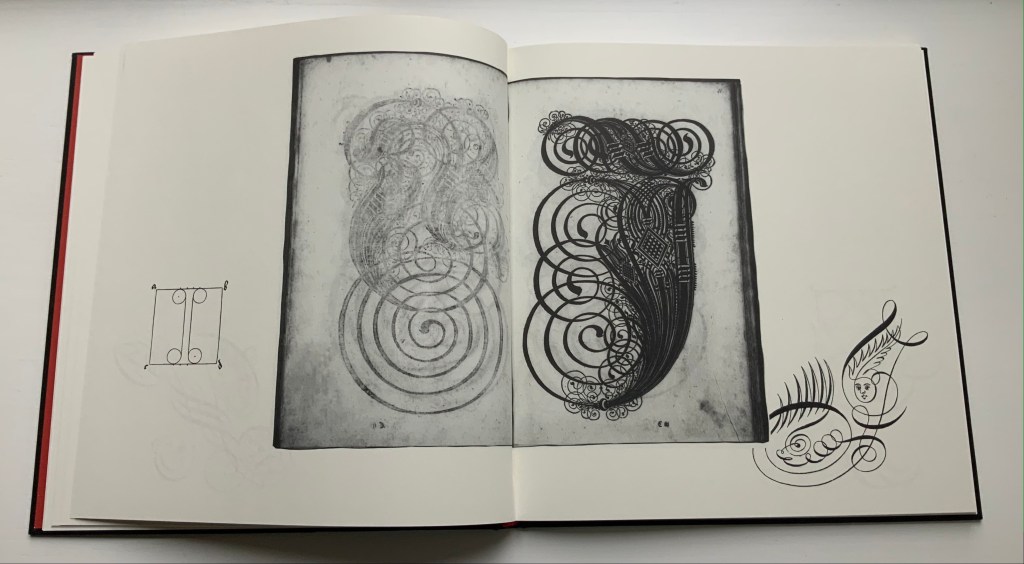

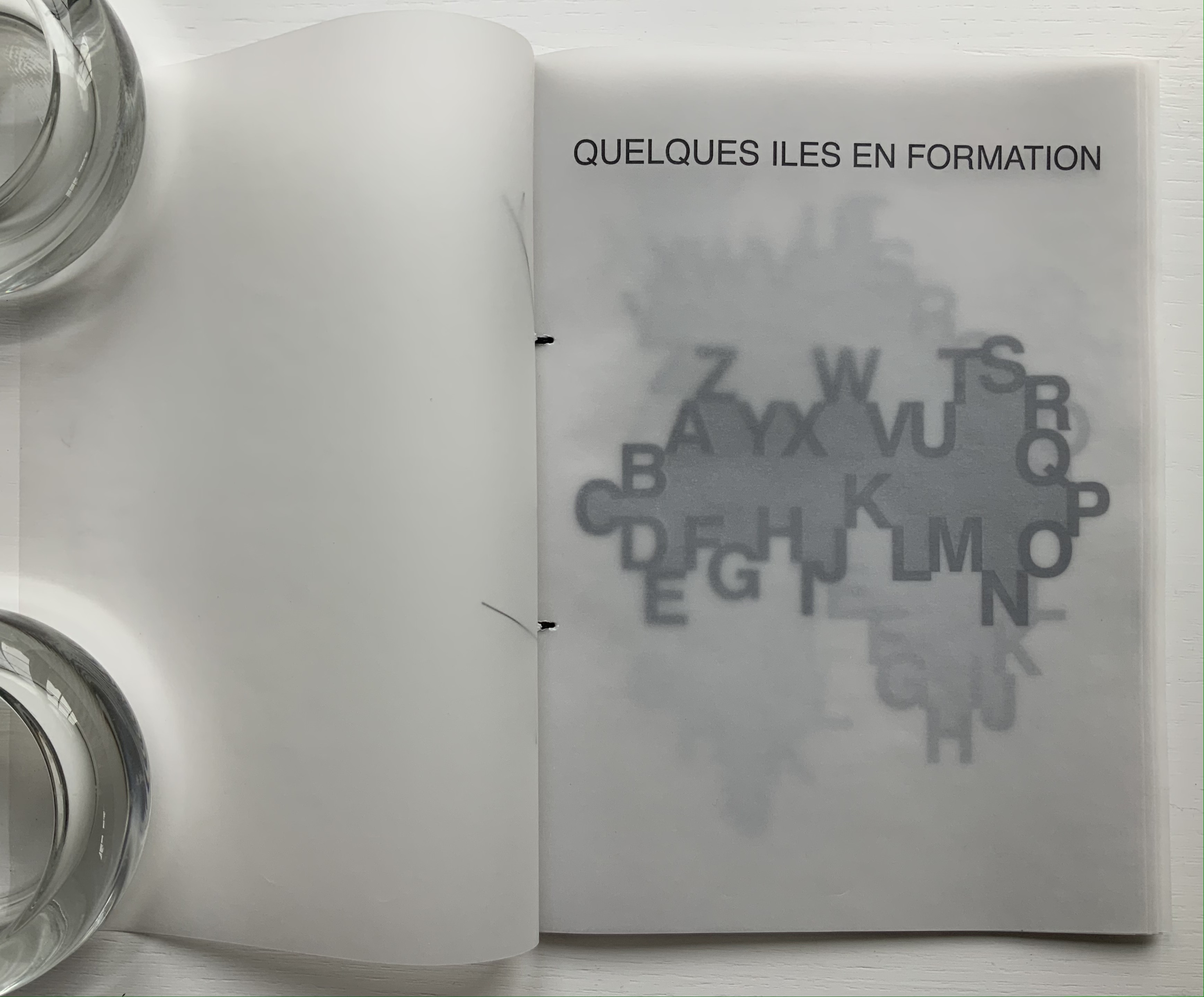

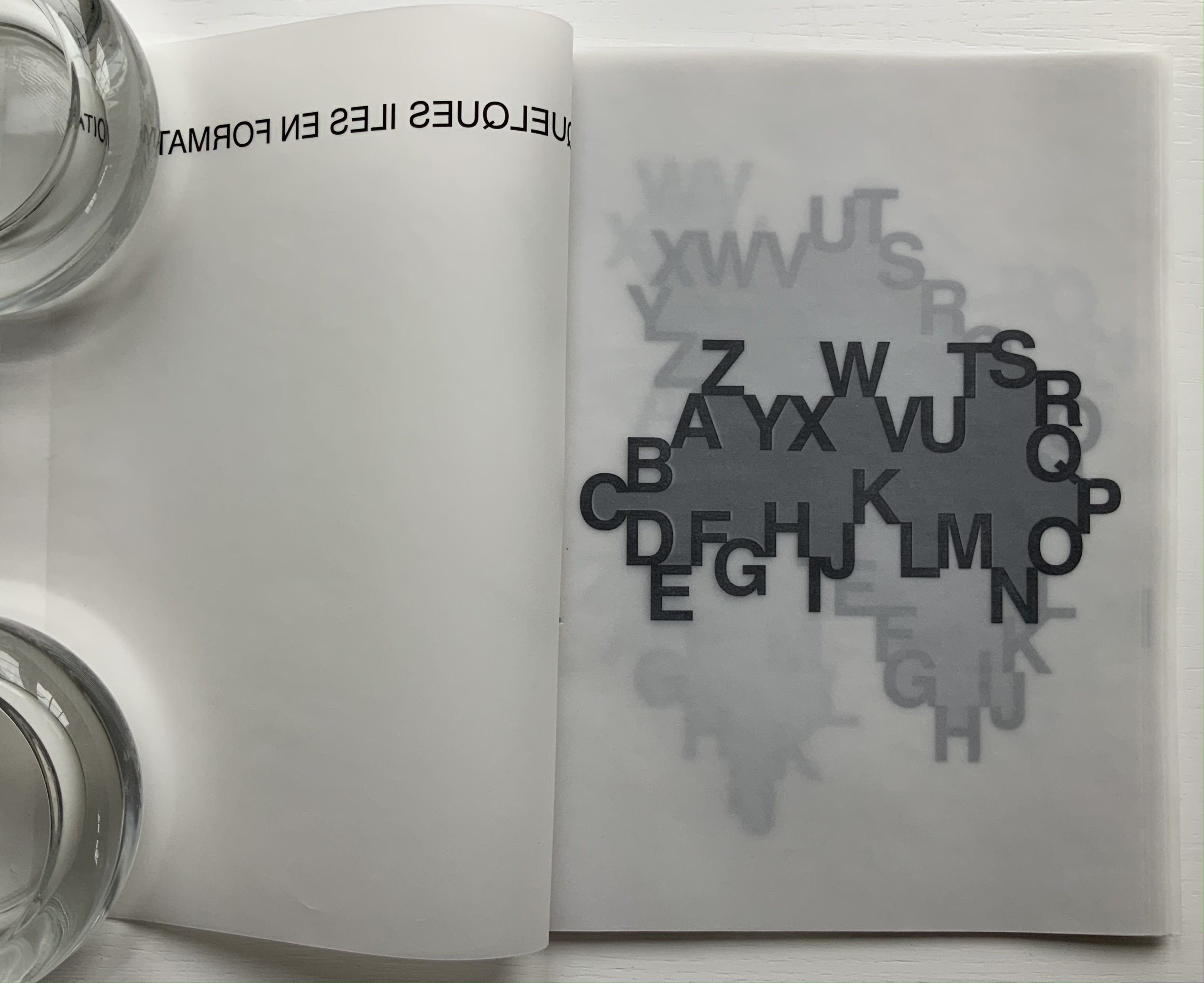

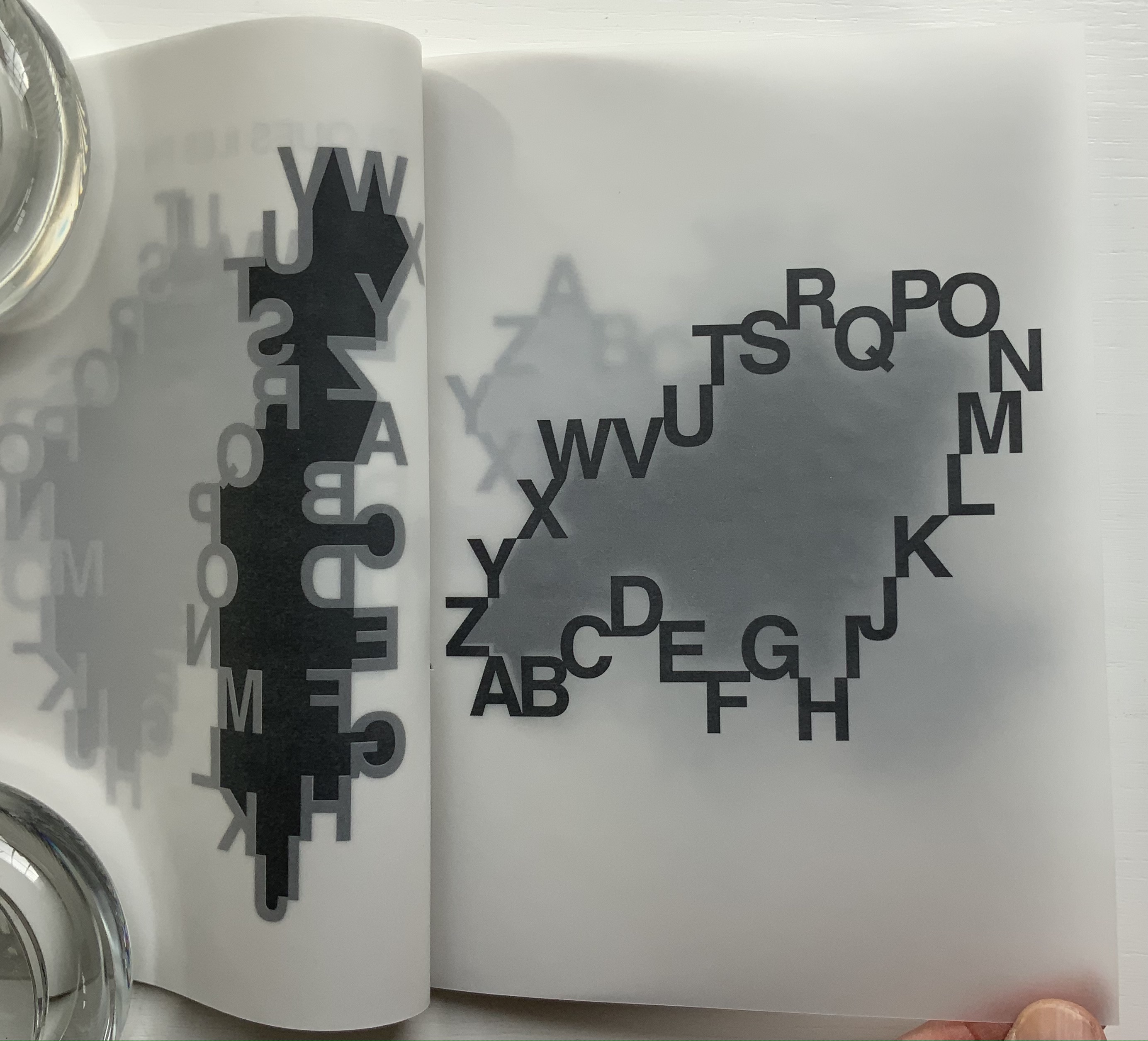

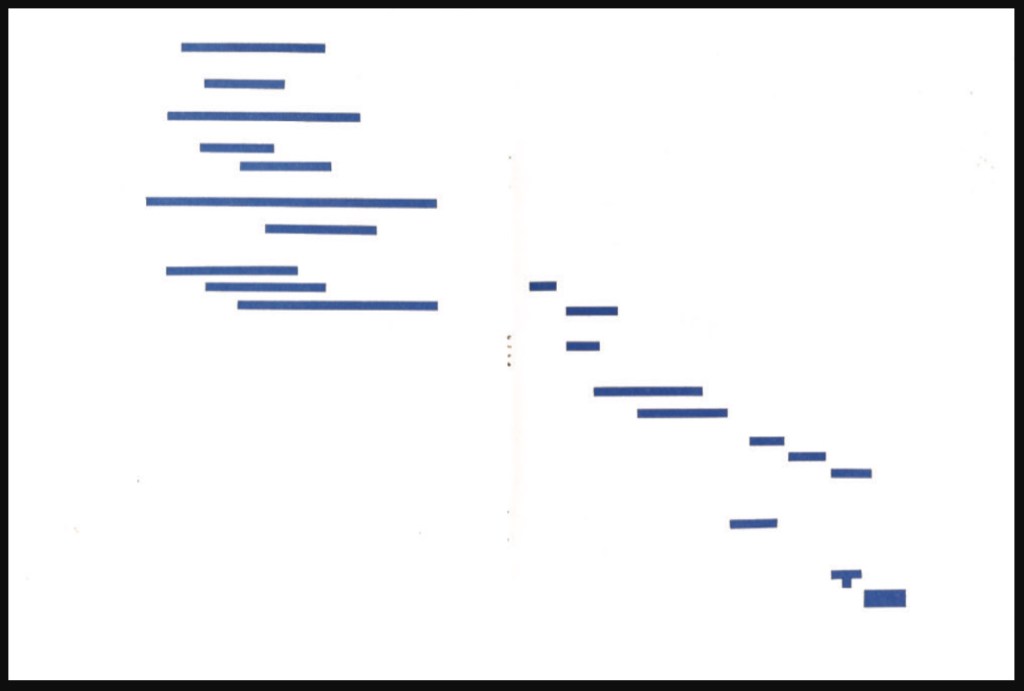

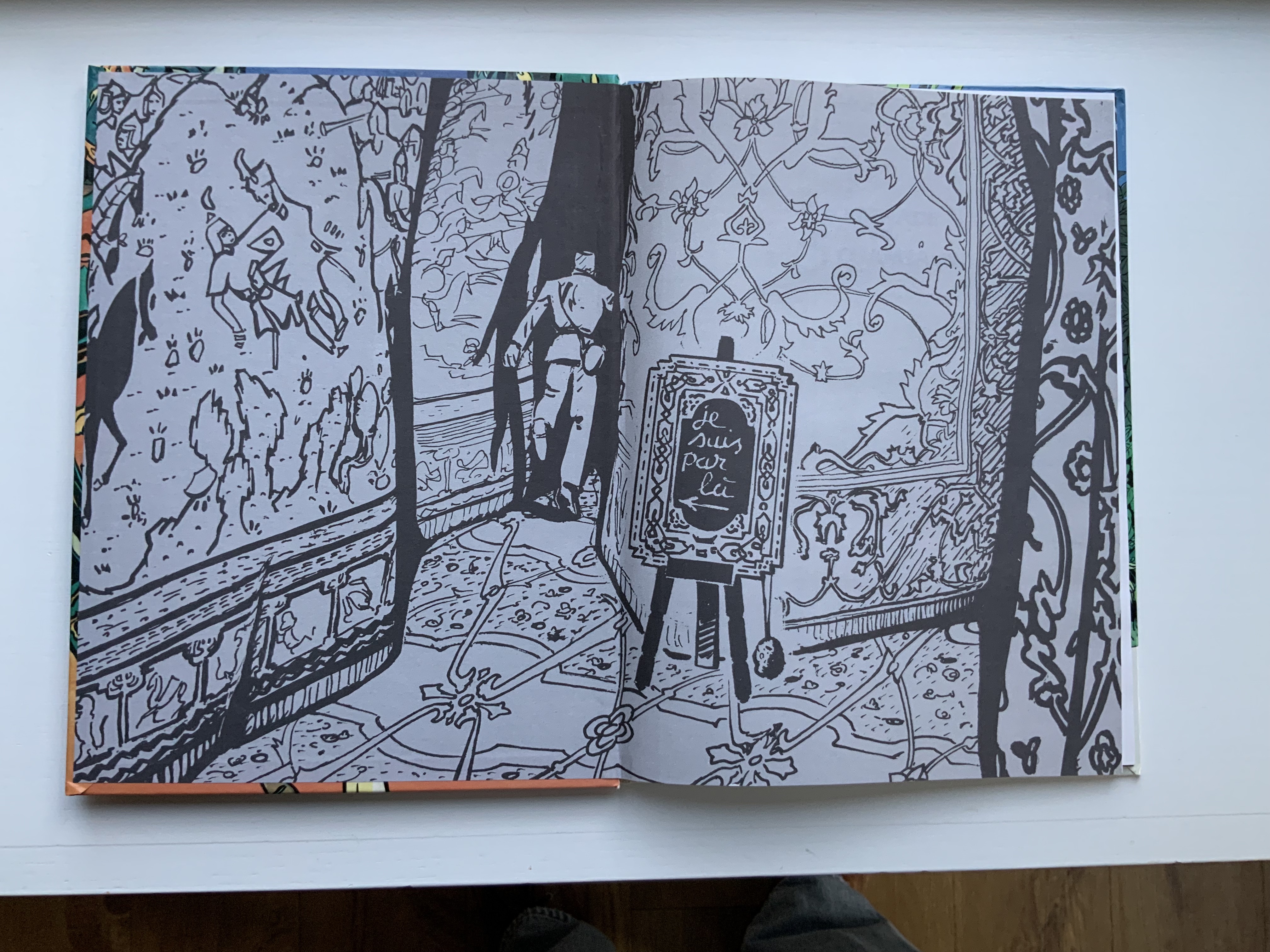

Quelques îles en formation consists of fifteen single-fold folios handsewn with black thread. The first and last folios serve for the front cover/title page and colophon/back cover, respectively. The thirteen folios between them constitute the îles/”islands” being formed by the encircling letters of the alphabet and the encircled masses laser-printed on the translucent paper. But why “some islands”/quelques îles and not just thirteen? As the reader/viewer moves through this work, it dawns that there are far more than thirteen ways of looking at these blackbirds.

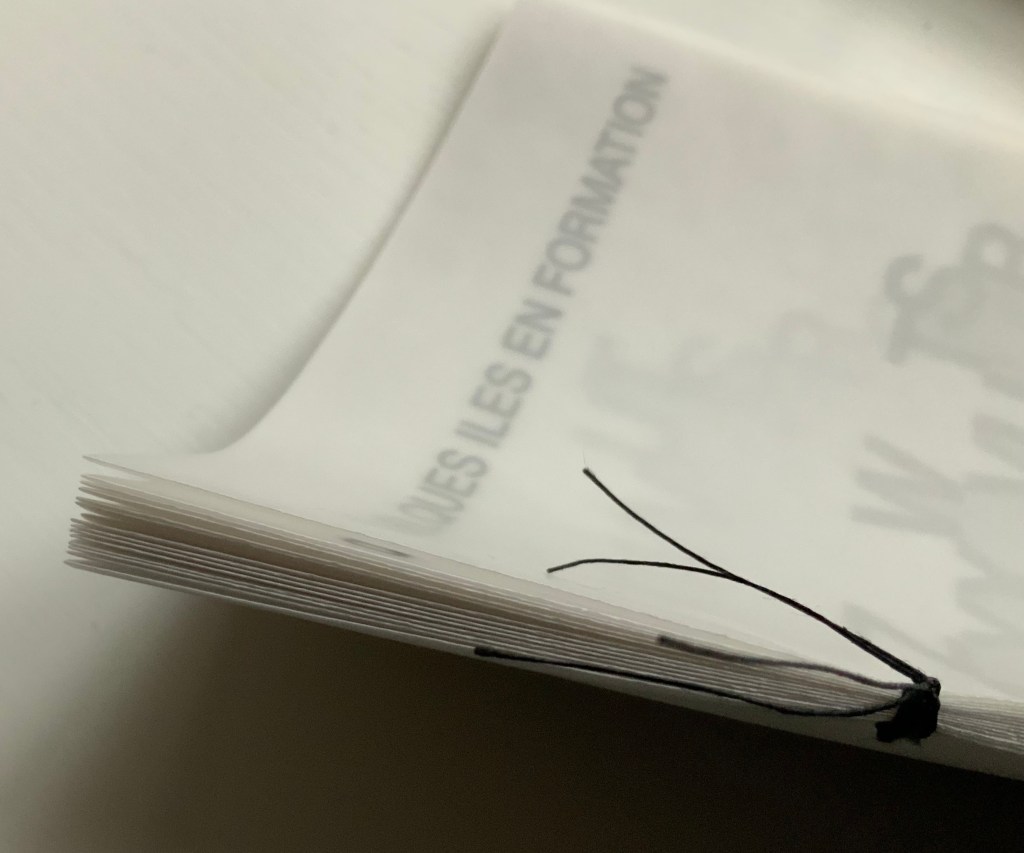

Spine, showing the single-fold folios.

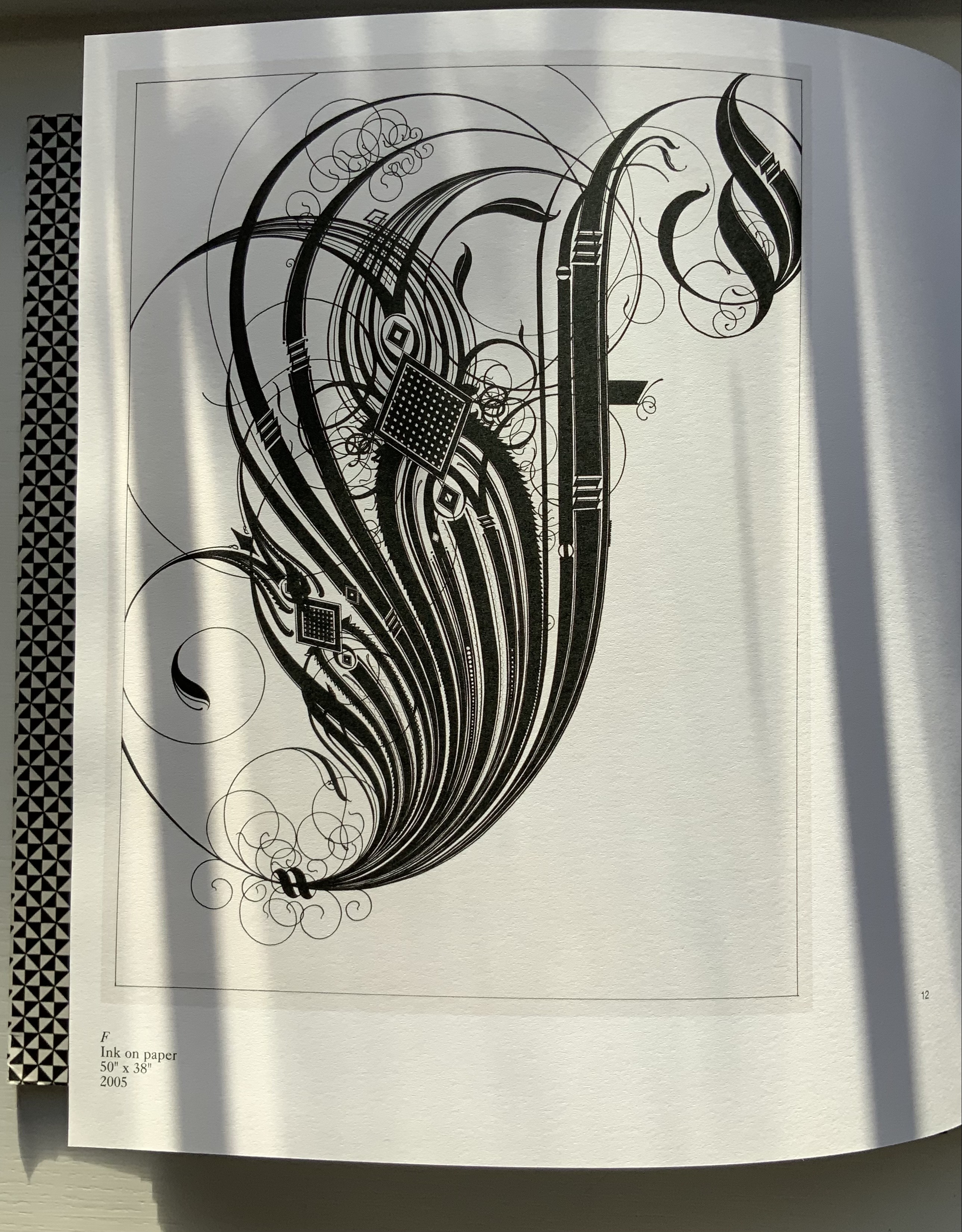

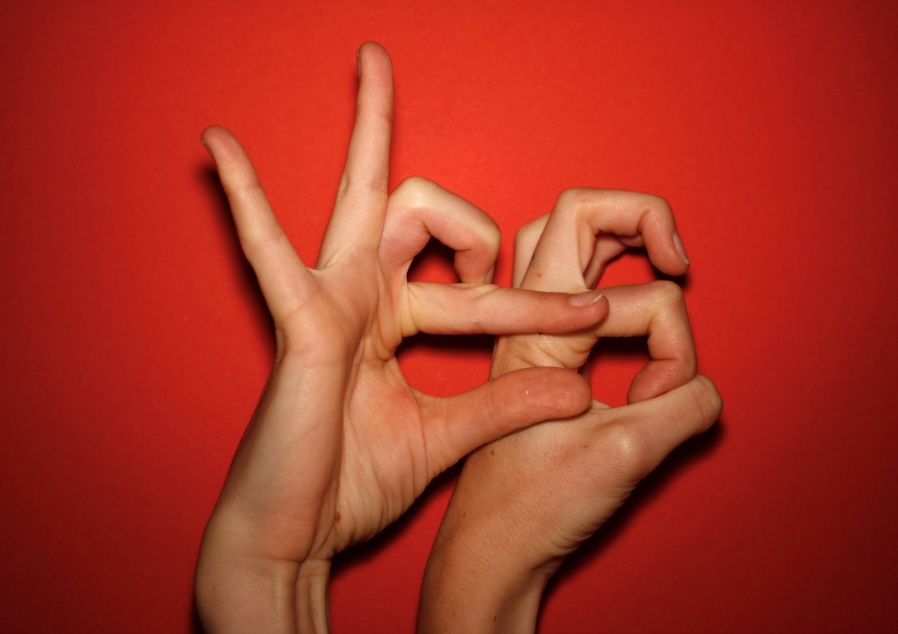

To talk about the folios (and since the pages are unnumbered), let’s name them “Island AB”, “Island CD” and so on. So the work’s second folio would be Island AB (below). If we go round the island clockwise from Z, we are reading the alphabet in reverse. This doesn’t seem right (although we are reading à droite/”to the right”). But to follow the Latin alphabet aright, we are forced into reading right to left. Once we reach letter C, the Western norm of left-to-right reading asserts itself — even if bumpily so — but with letter P, we are back to the Middle/Far East direction of reading. At least, in either direction, the dark gray body of land is clear enough. Or is it?

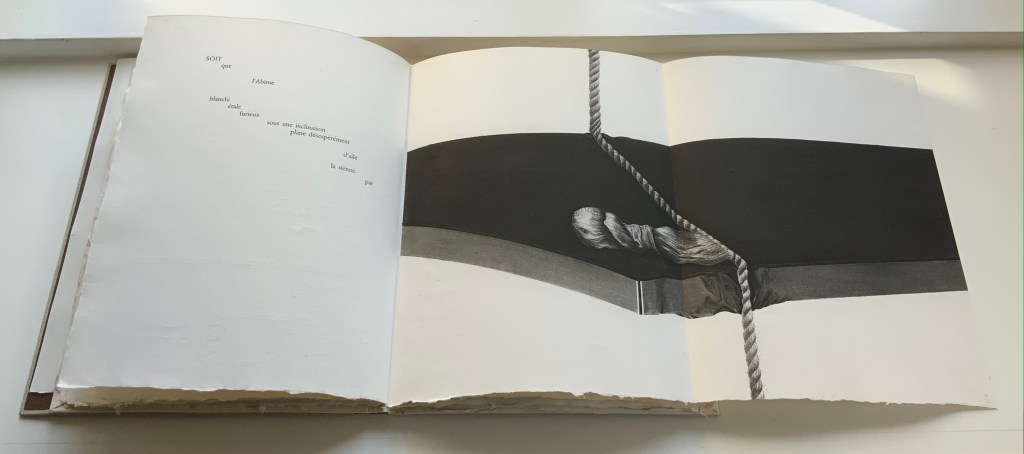

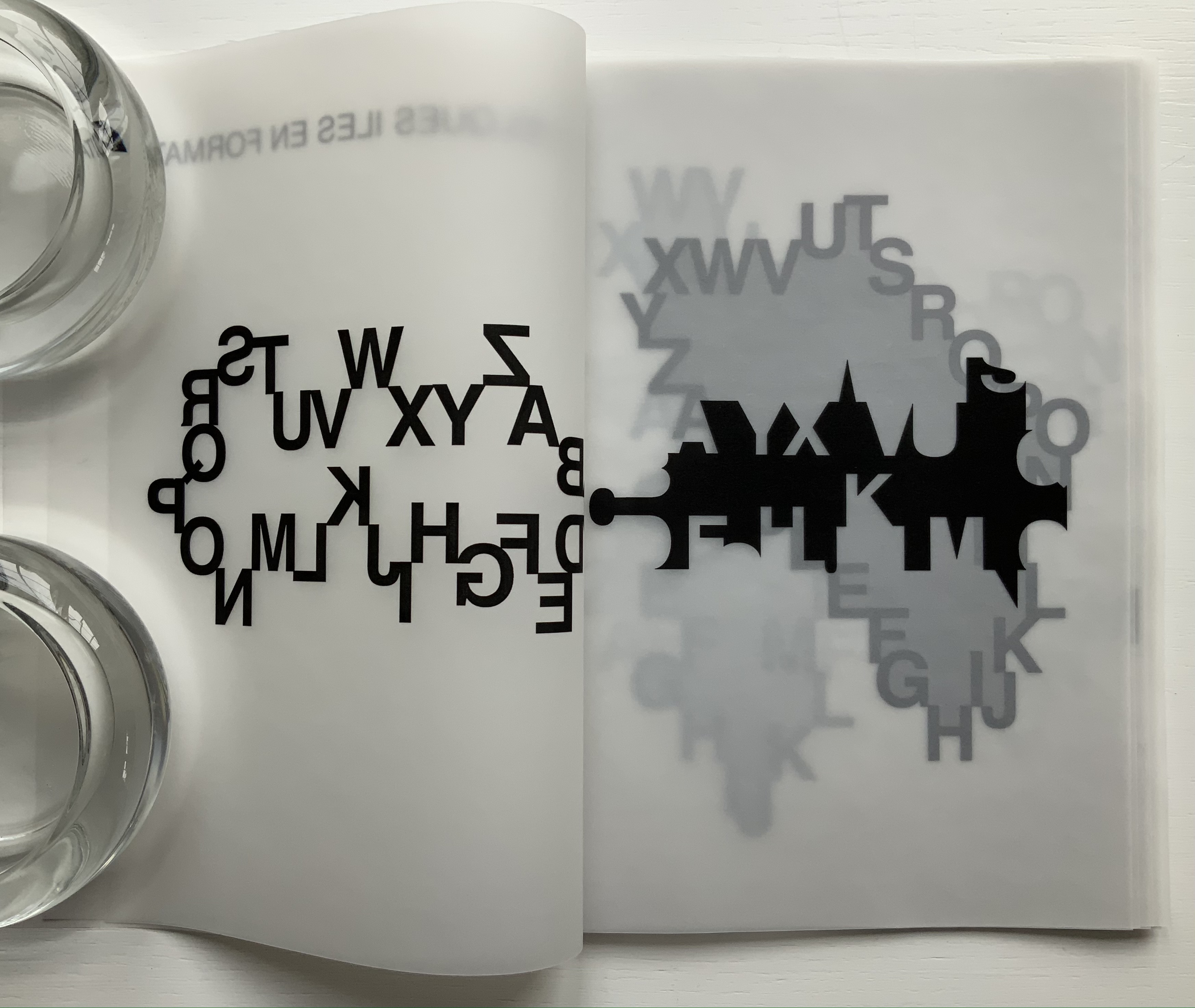

Folio “Island AB”: first, second and third pages displayed. The fourth page appears below.

When Island AB’s first page turns, the black letters separate from the body they define. They float in reverse on the second page (above) even more black. The dark gray body now becomes a separated mass of black on the third page (above). It looks like an abstract image or a skyline, but here and there, the island’s contour shows just enough parts of the absent island-forming letters to make out the Y, X, F, K and M. When the third page turns, Island AB’s “underside” appears on the fourth page of the folio (below). The reversed black letters on the second page lighten to gray as the translucent paper falls over them, but the black abstract or skyline or island printed on the third page shows through just as black as before.

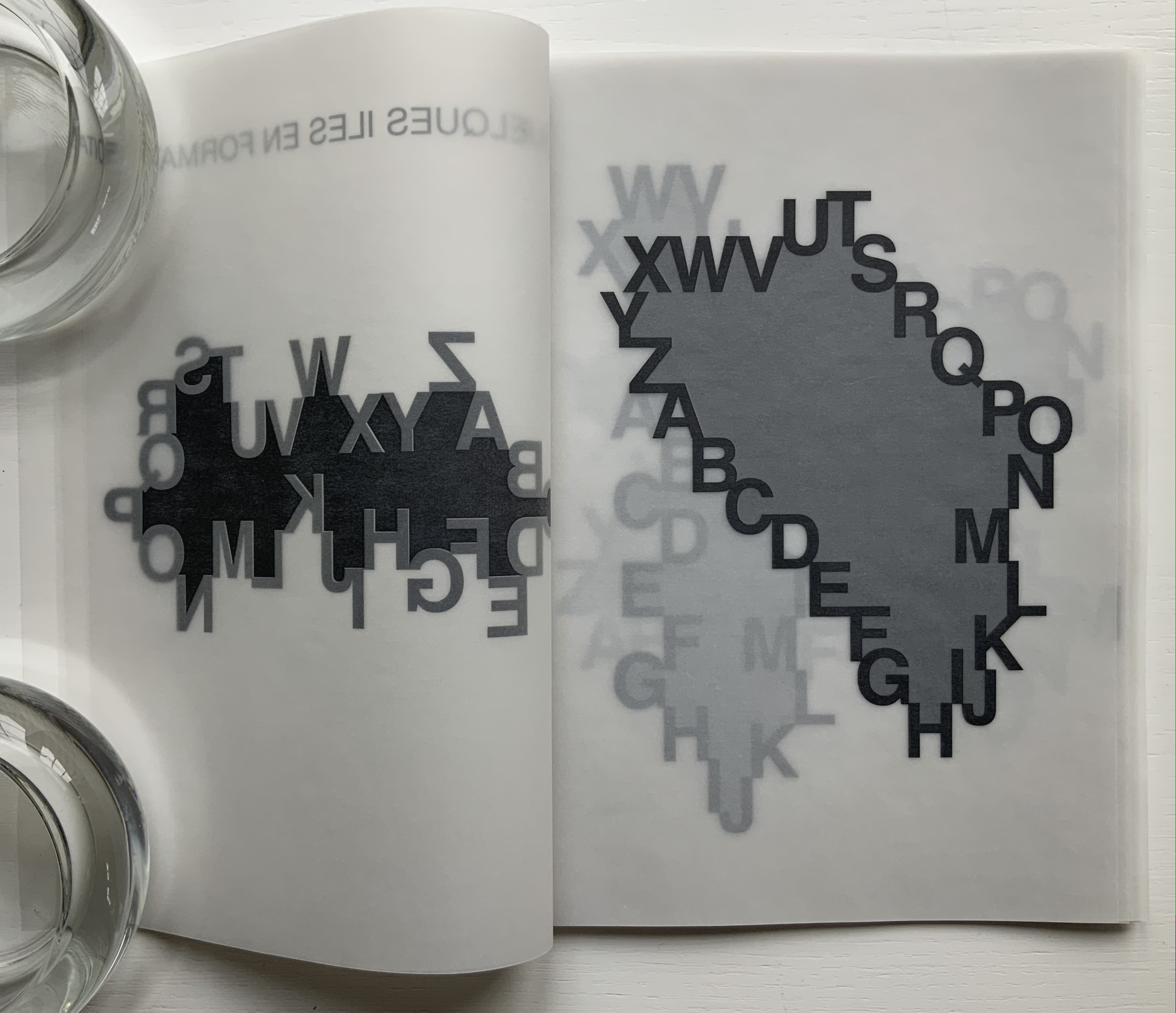

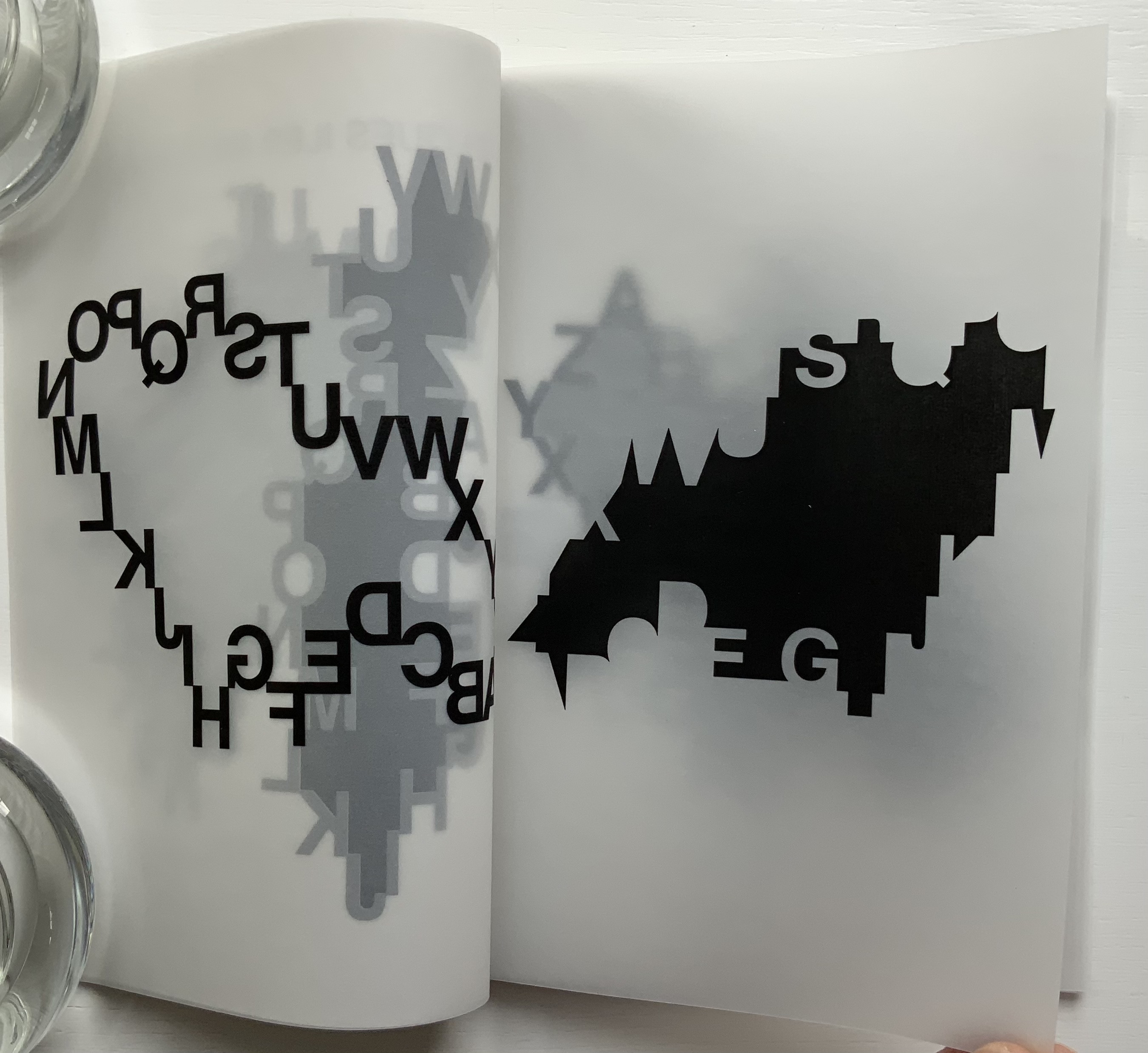

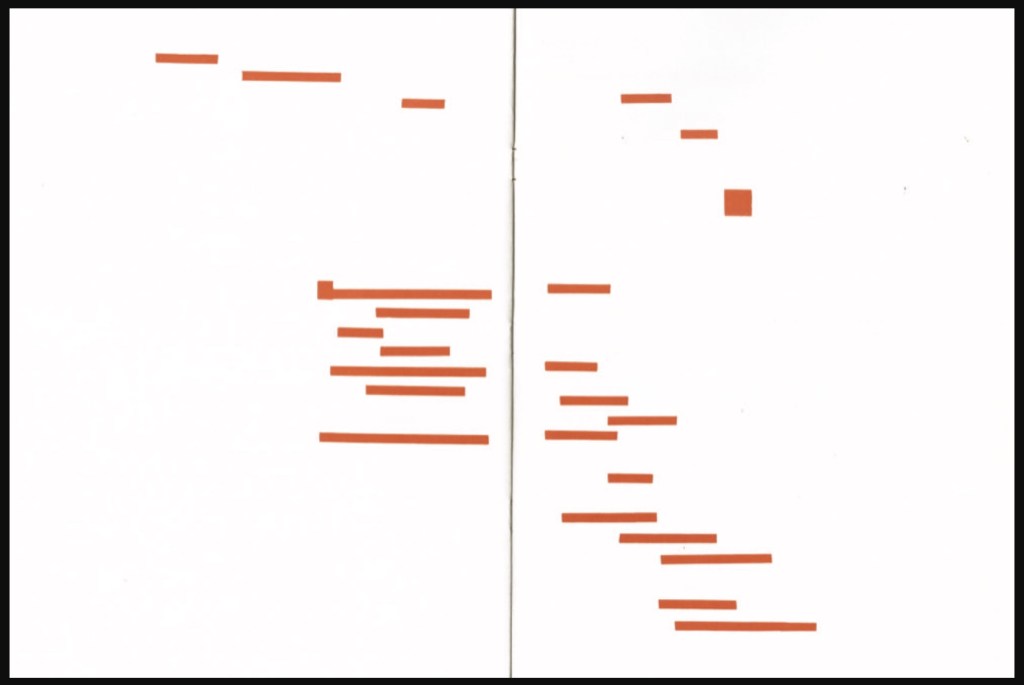

Island AB’s fourth page; Island CD’s first, second and third pages.

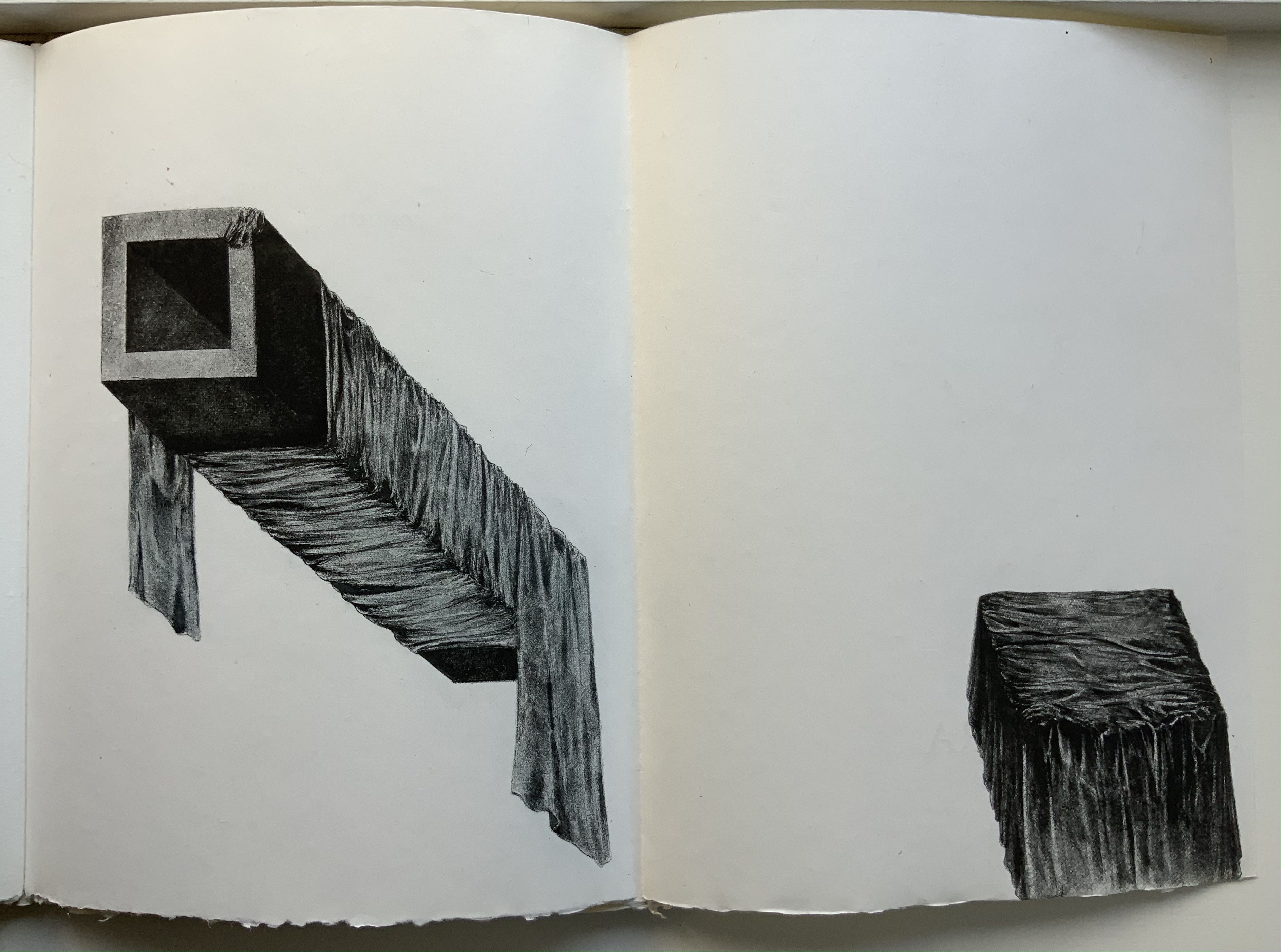

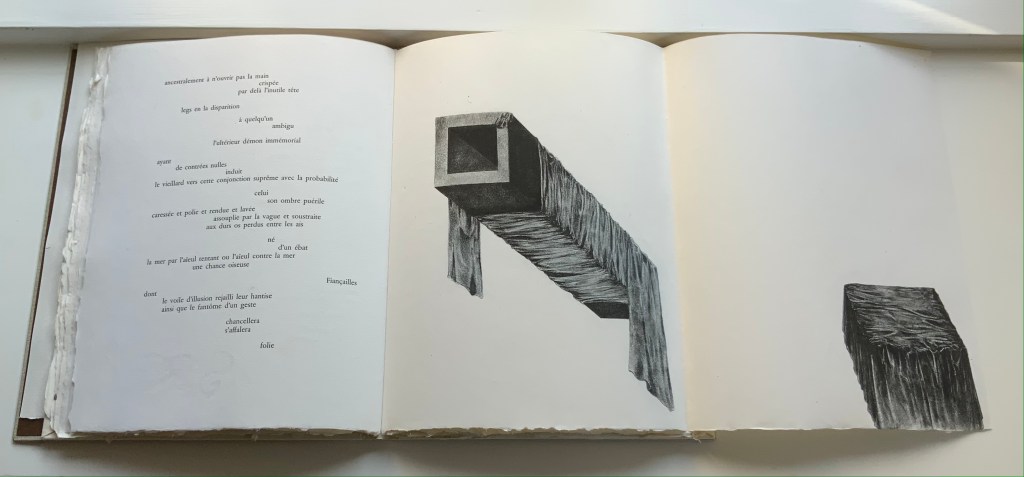

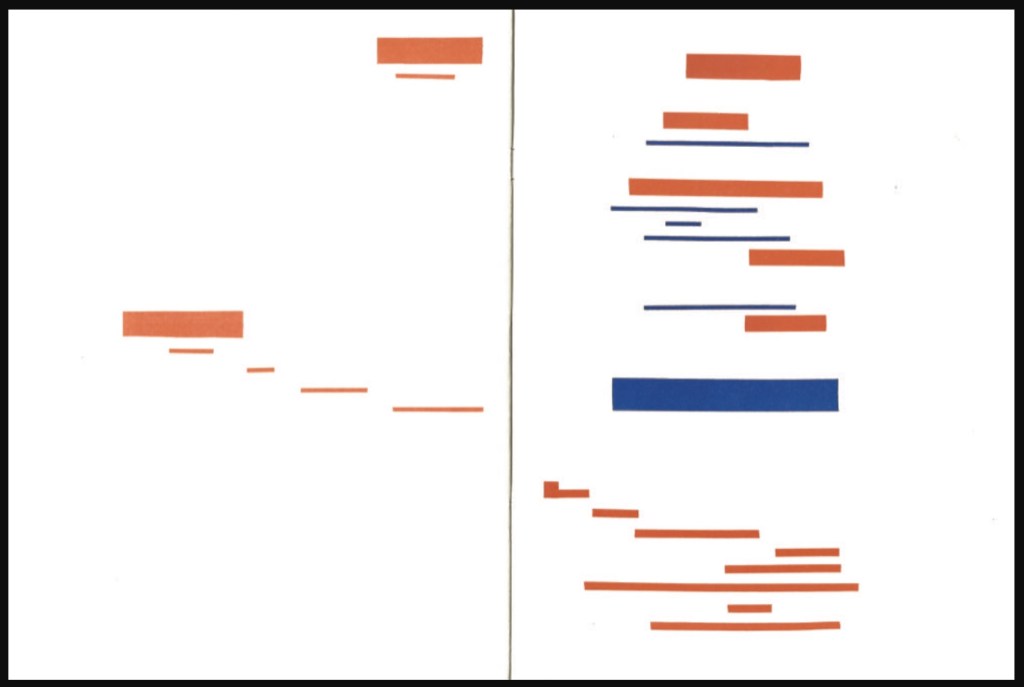

In an installation setting, three of these bodies of black become the work Îles capitales, a standalone large-scale hanging made from industrial plywood covered with thin black melamine. In contrast, the book form layers the islands, adding yet another layer in the process of îles en formation. The islands beneath cast shadowy outcroppings upwards around the island covering them. Indeed, as pages turn, outcroppings disappear, replaced by others from islands further underneath. Look again at Islands AB and CD above.

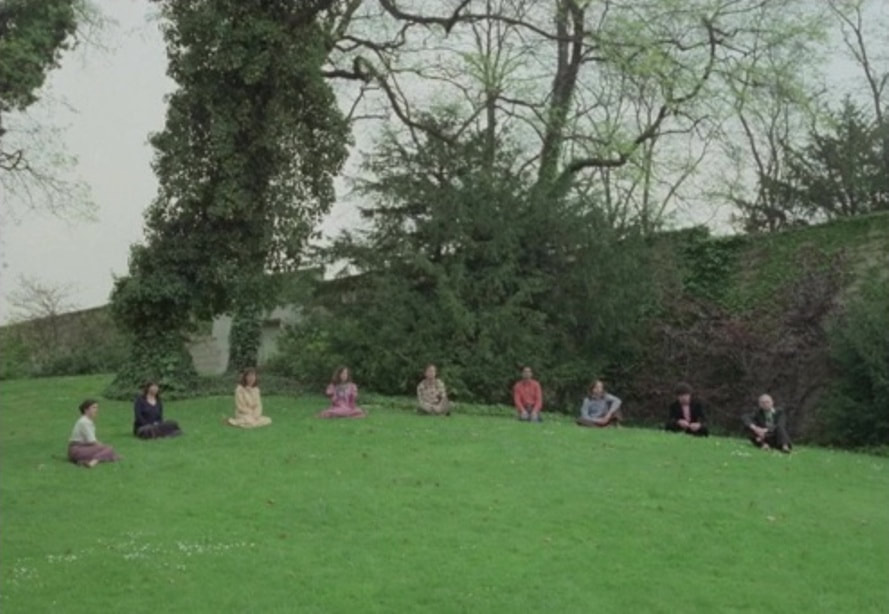

Gallery view of Îles capitales (center) in “Bertrand Gadenne/Étienne Pressager: A,B,C,D, Etcaetera”, a joint exhibition at Lieu d’Art et Action Contemporaine (LAAC), Musée de France, Musée de la Ville de Dunkerque, 2007. Photo: Courtesy of Étienne Pressager.

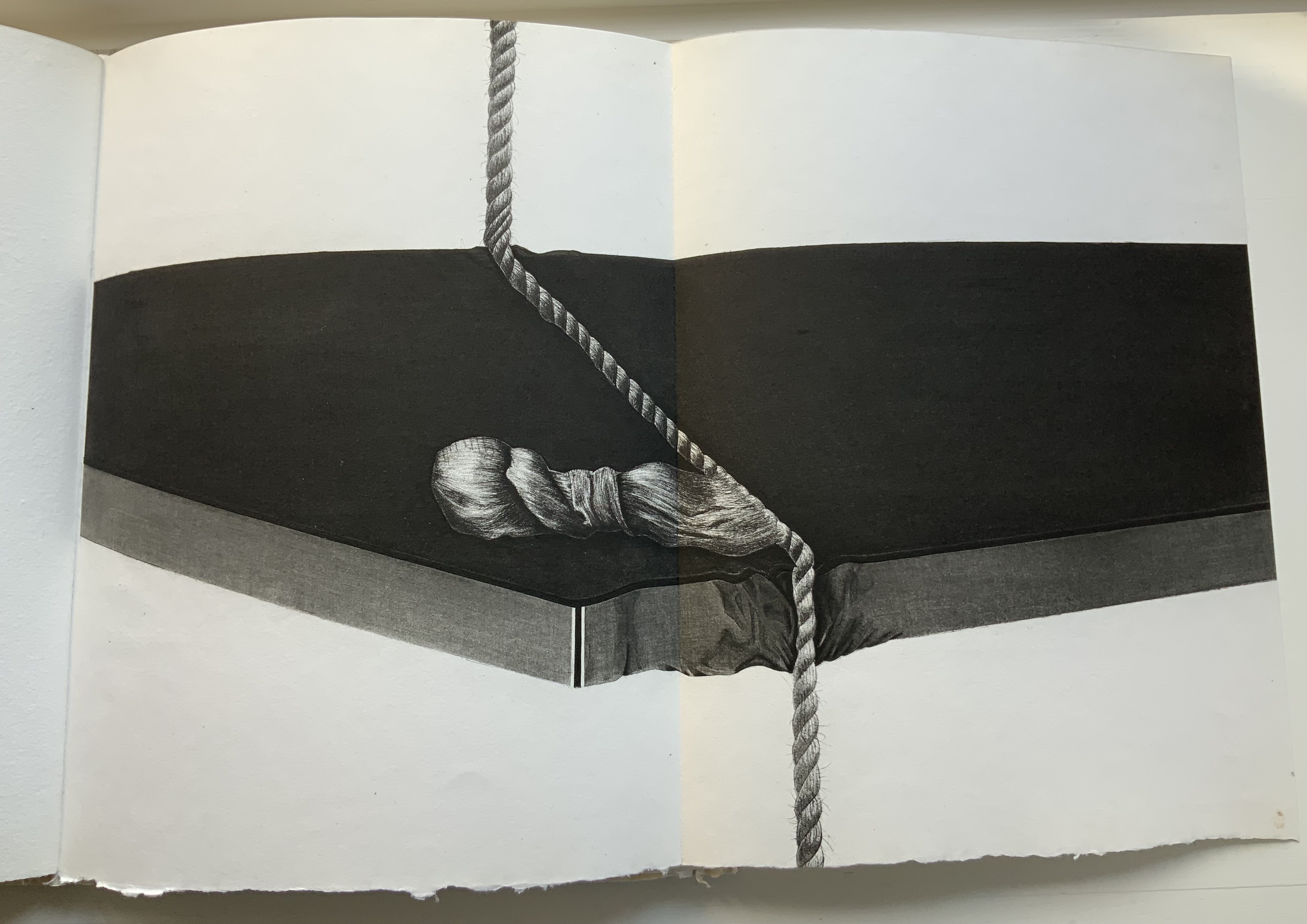

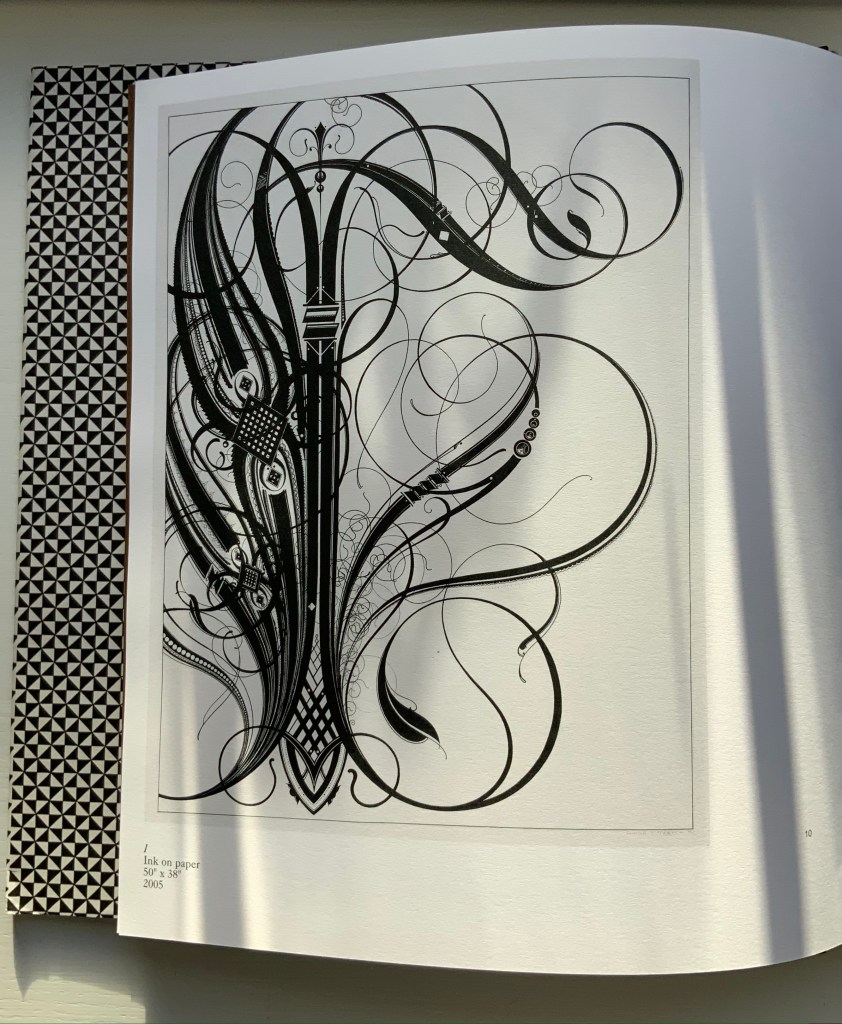

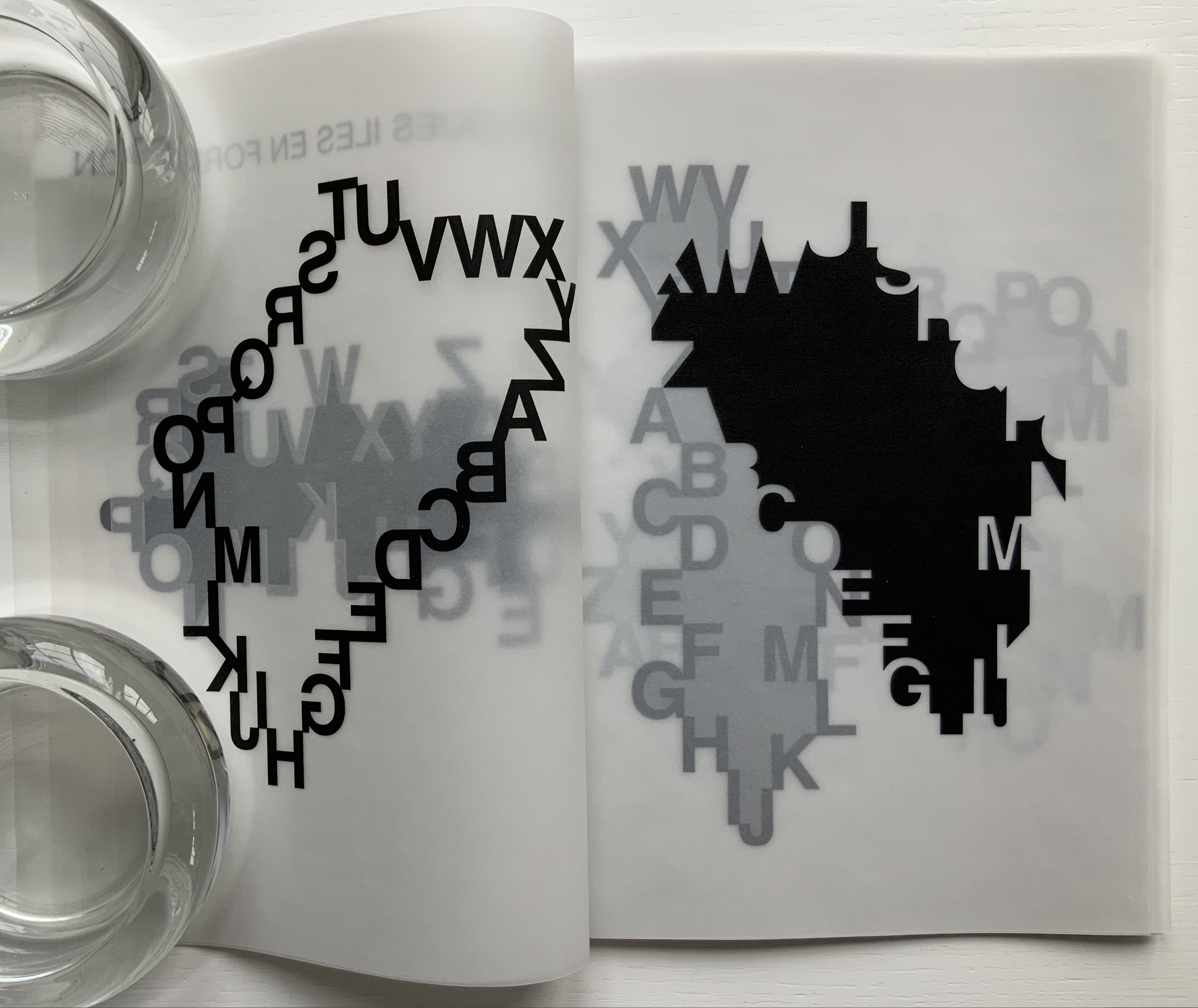

Another element of the layering comes into play as pages turn. It comes just as a page is lifted. Below, on the left, the letters around Island GH lift away leaving a blurred outline of the island beneath; on the right, the island becomes more sharply defined as the page begins to turn. Calling further attention to the layering, each folio is folded offset, the first and second pages always being wider than the third and fourth, which facilitates turning the slippery translucent pages but highlights the work’s in-betweenness, its gradations of gray, black and white.

Island GH: with its first and third pages being turned.

Each island is shaped by the same 26 letters, but the contours of each island differ. An infinite number of varied archipelagoes could be derived from Pressager’s ourobouros-like alphabet, just as an infinite number of words can be generated from the alphabet, which in turn can be used to define, delineate and bridge domains or islands limited only by our imaginations. Confronted by such infinities, what can a finite human do but offer up quelques îles en formation?

Further Reading

Charles-Arthur Boyer. 2003. Étienne Pressager: traversées : [exposition], Saint-Fons, Centre d’arts plastiques, 7 juin – 19 juillet 2003. Saint-Fons: Centre d’Arts Plastiques.

Pressager, Étienne. 1994. Étienne Pressager: Catalogue édité suite à l’exposition à la synagogue de Delme en février-mars 1994. Delme: Synagogue de Delme.

Recht, Roland. 2009. Point de fuite: les images des images des images : essais critiques sur l’art actuel, 1987-2007 : Marcel Broodthaers, Hubert Duprat, Robert Filliou, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Jean-Luc Godard, Thomas Huber, Anselm Kiefer, Lee Ufan, René Magritte, Claudio Parmiggiani, Giuseppe Penone, Étienne Pressager, Claire Roudenko-Bertin, Sarkis. Paris: Beaux-arts de Paris, les éd.

Treps, Marie. 1995. Étienne Pressager. Castres: Centre d’Art Contemporain de Castres.