This is not a stone (2017)

This is not a stone (2017)

Sunkyung Cho

Exposed spine binding with cross weave filament tape, board-covered. 170 x 170 mm. Acquired from SpazioB**K, 6 April 2025.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

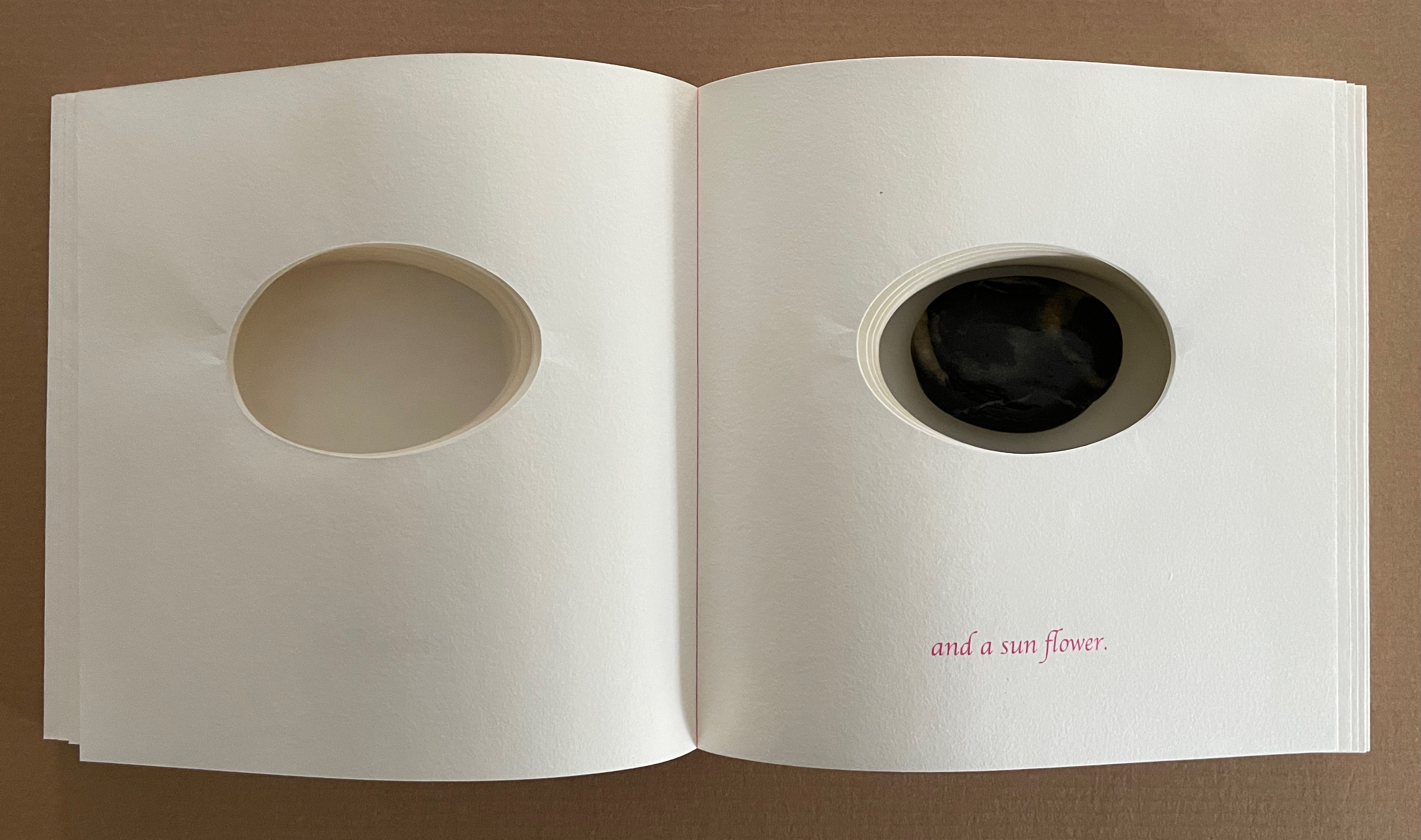

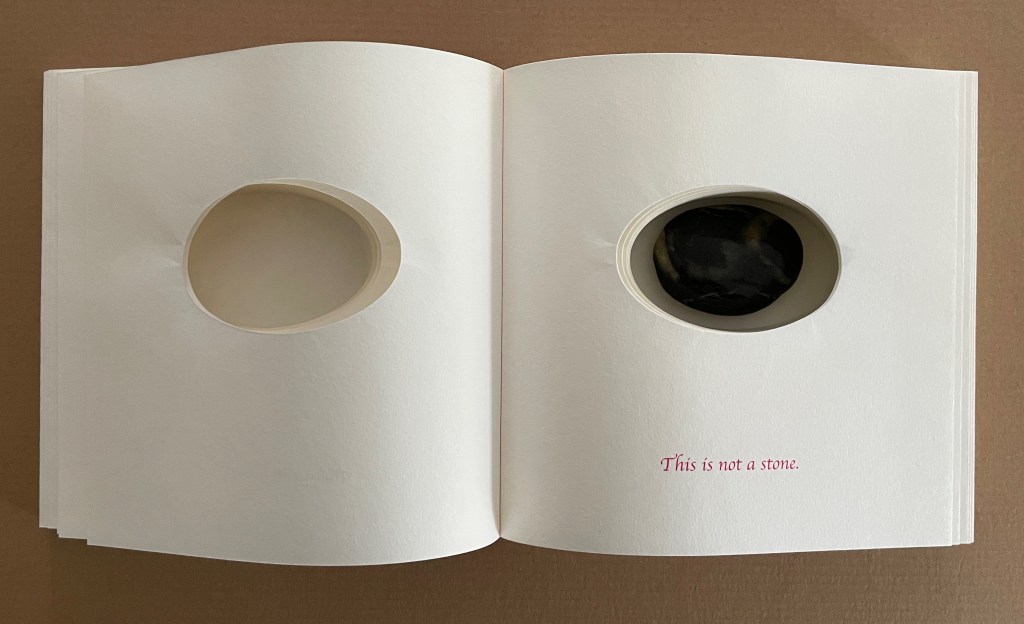

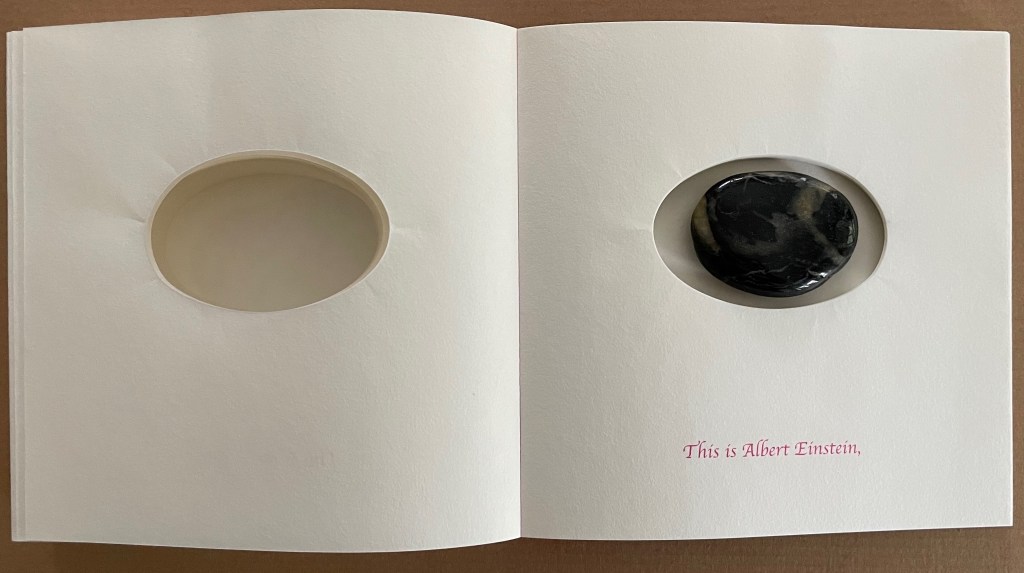

Just as you think this will be another two-dimensional riff on René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images (aka Ceci n’est pas une pipe), the Chinese fold title page turns to reveal a cutout well with a stone at the bottom.

With the turn of the next two pages, it appears we are in for a series of metaphors and riddles, and something more than a three-dimensional riff on the anti-metaphor and the gap between words (symbols) and objects. First, this not-a-stone is “an apple,” but then turn the next page, and the not-a-stone is also “a sun flower”. Is there some law of commutation that applies: If not-a-stone = apple, and not-a-stone = sun flower, therefore, apple = sun flower? Because it is round, because it is vegetal?

Over the next turns, we have “the Sun” and “the earth”, then “a crystal” and “a flake of snow in the Himalyas”, then “a beetle” and “a scorpion”, and on the pairs go, each separated with the spread “This is not a stone”. All along, while being urged to deny the evidence of reality, we are asked to accept the evidence of metaphor and imagination. Naturally our inbred pattern-seeking and ludic behaviors kick in, as if this were a game of “Twenty Questions”. But the pairs run the gamut of Animal, Vegetable, Mineral and beyond.

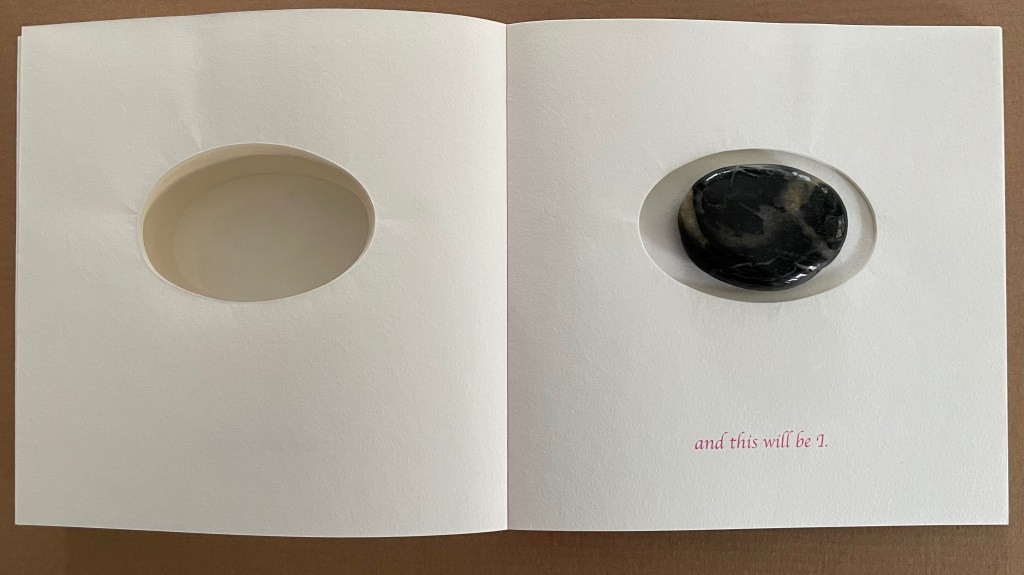

By the last page, it is as if we are playing “Twenty Questions” with the stone itself. That is, if the “I” is the stone saying, “and this will be I”. Is the stone uttering a deliberate a-grammatical union of subject (I) and object (me)? Is it a verbal visual pun (I-eye) evoking Emersonian Transcendentalism? Perhaps this stone that says “This is not a stone” is a Cretan philosopher’s stone, and round and round we will go.

On the artist’s website (www.somebooks.kr), the product page displays this Korean expression and its translation: 하나의 돌은 돌이자 다른 모든 것이다 [“One stone is a stone and everything else”]. It does not appear anywhere in the book, so perhaps it is unfair to invoke it as confirmation of any reading of This is not a stone. On the other hand, if you are going to play “Twenty Questions” with a Cretan philosopher’s stone, cheating may be your best option.

The other works by Sunkyung Cho in the collection are wordless, except for their titles, and lean more toward children’s books than This is not a stone. Like so many artists’ books, they occupy that crossover zone discussed by Sandra Beckett, Johanna Drucker, and Carol Scott (see Further Reading).

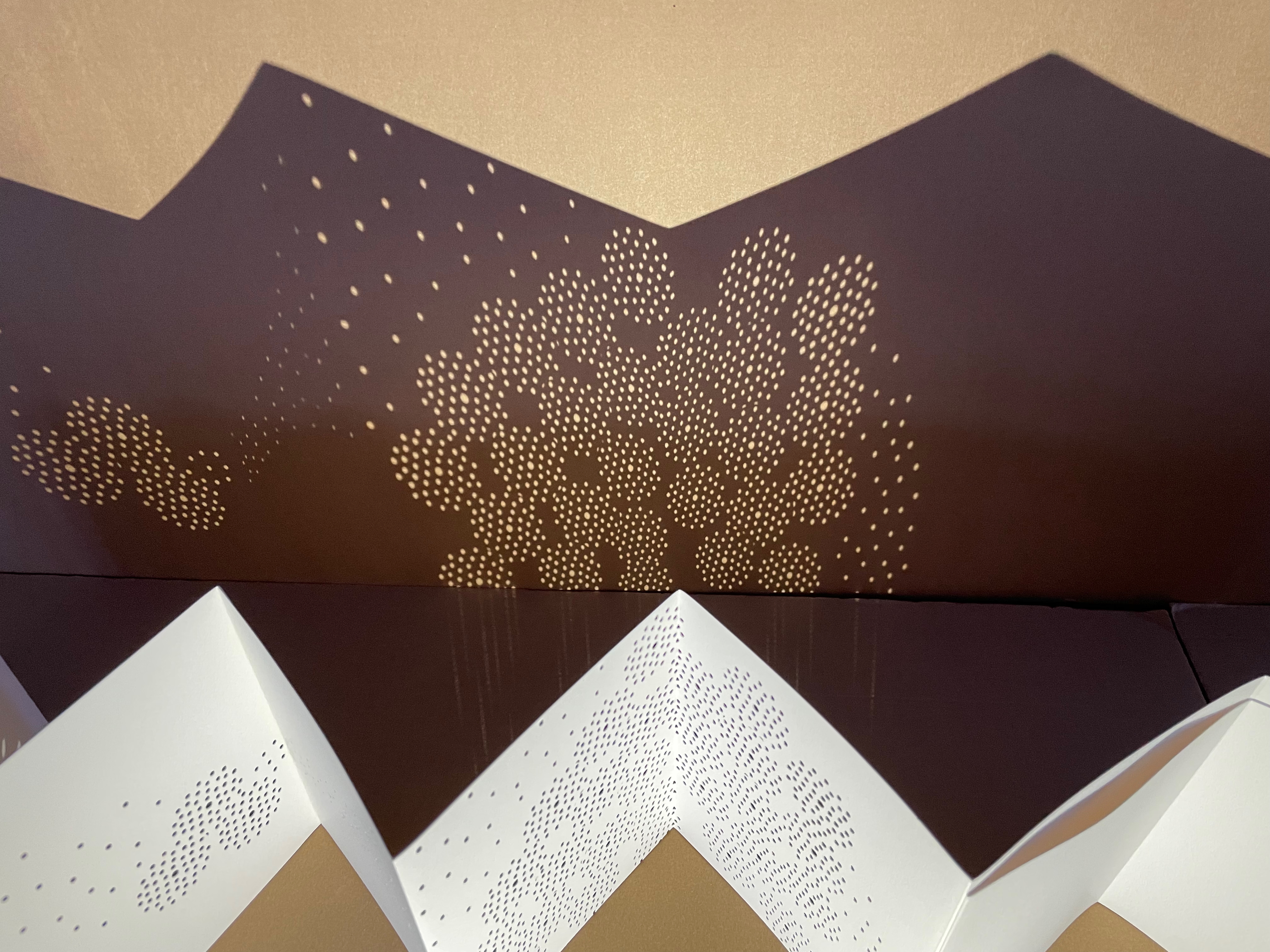

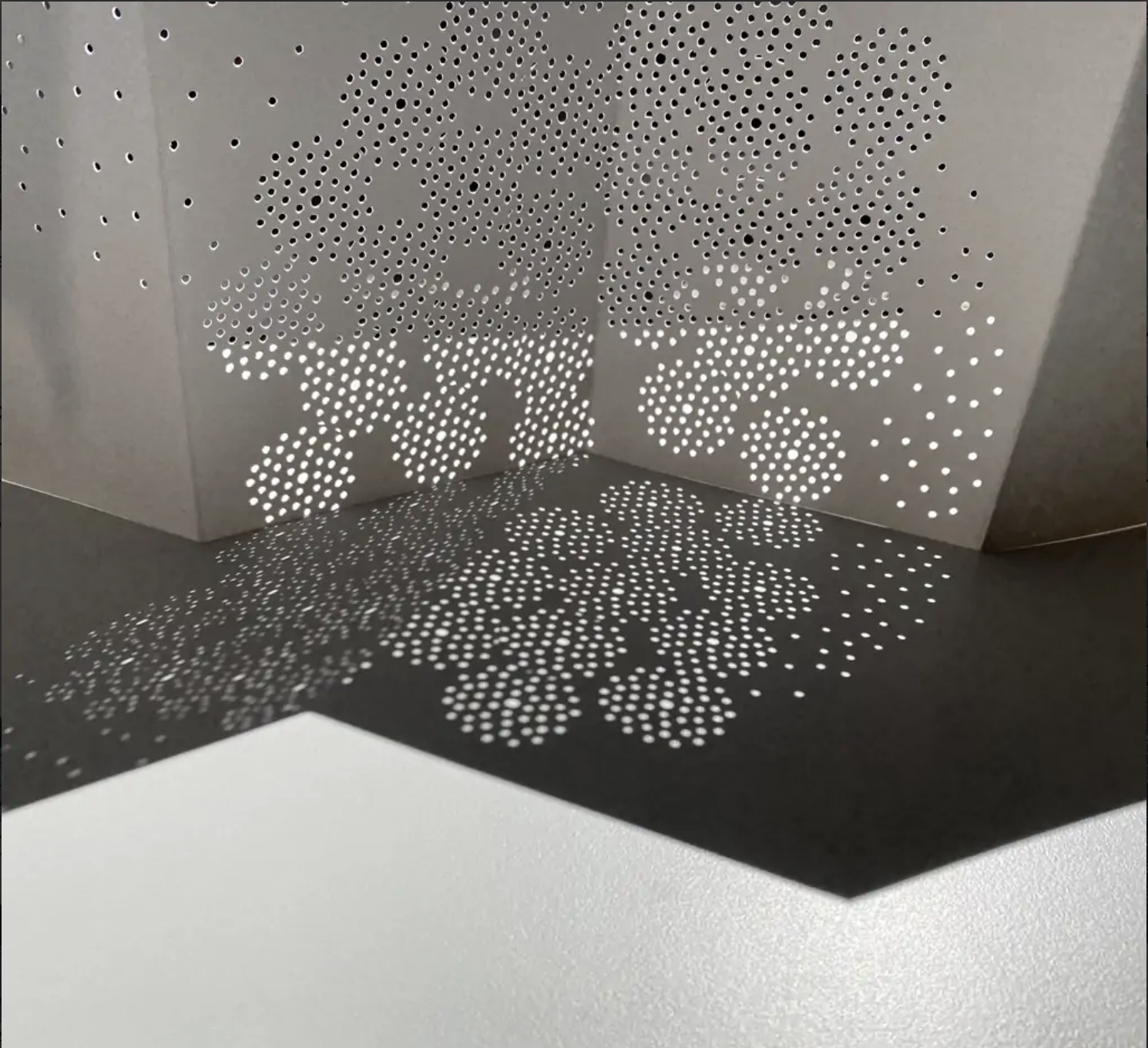

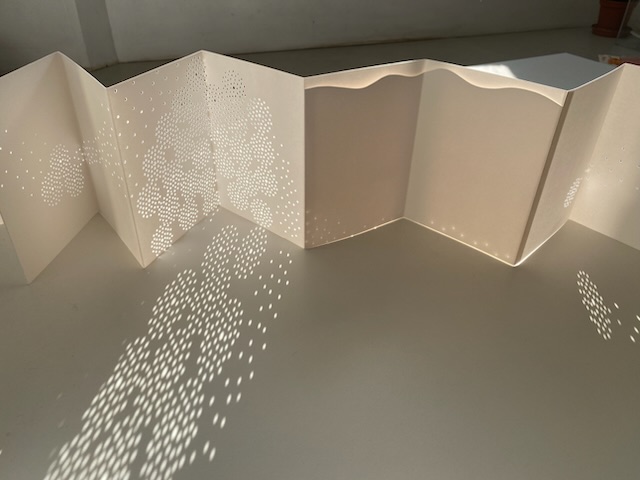

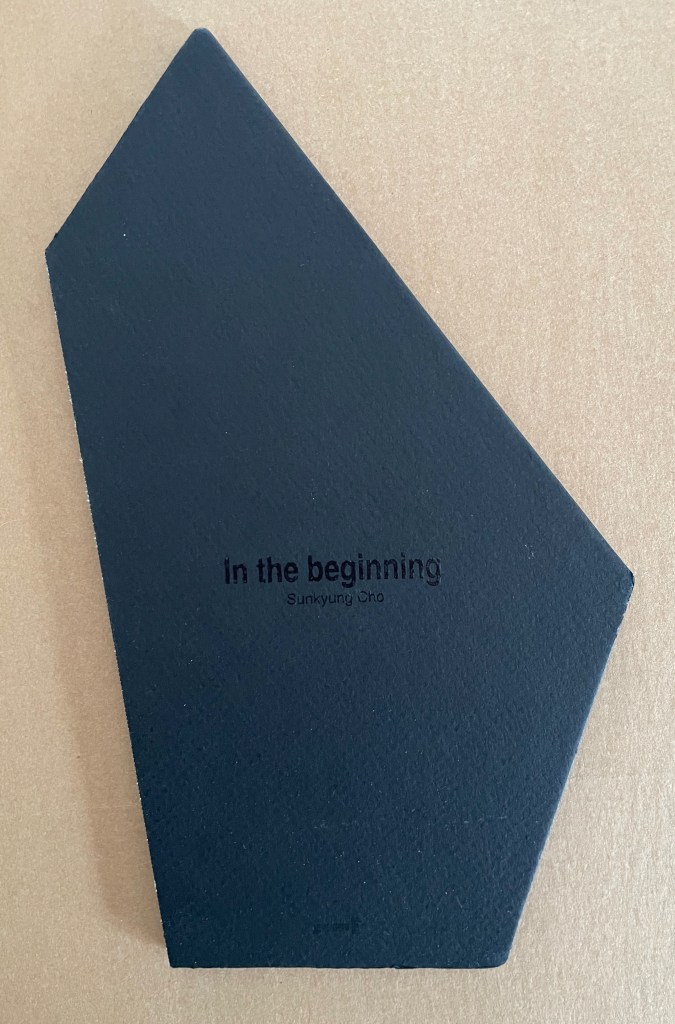

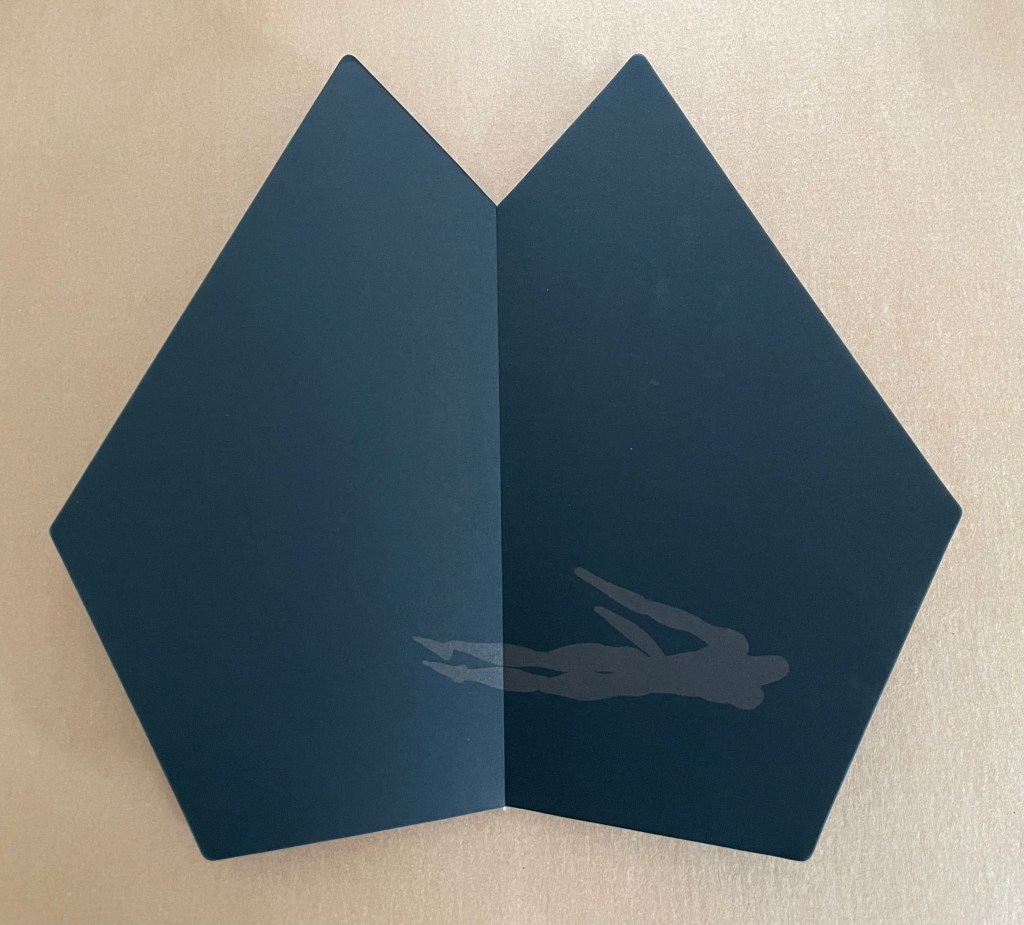

In the beginning (2012)

In the beginning (2012)

Sunkyung Cho

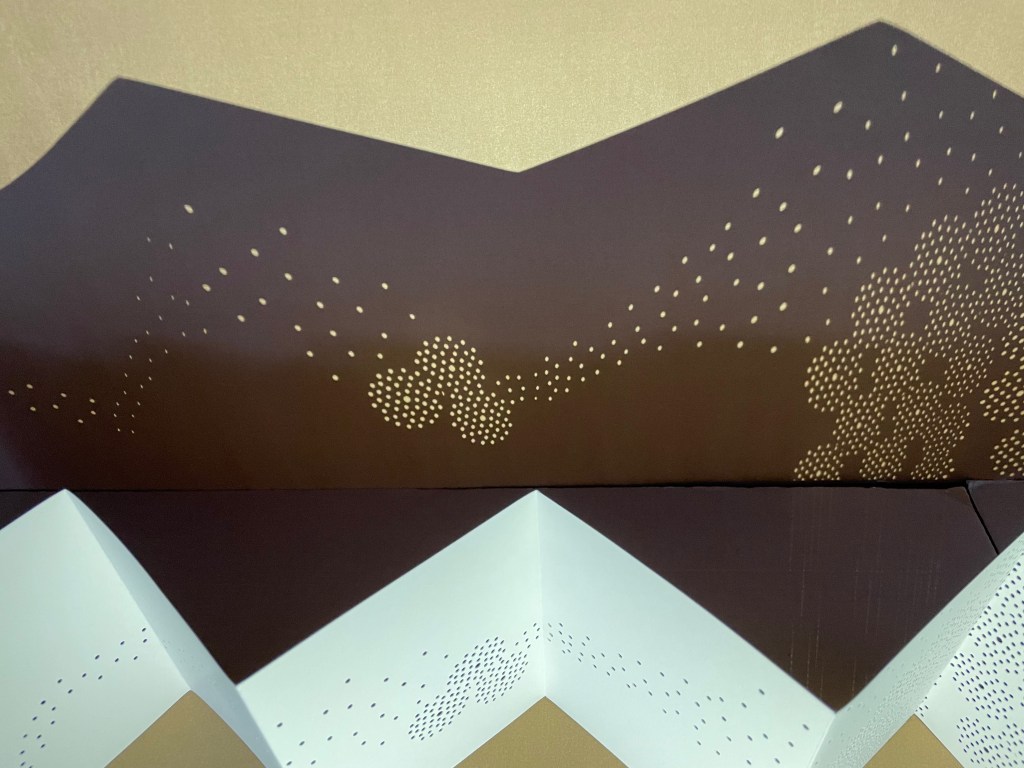

Softcover, sewn, exposed spine binding with cross weave filament tape. H260 x W150 mm. [36] pages. Unknown edition, of which this is #146. Acquired from SpazioB**K, 6 April 2025. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

From the artist’s website: 빛 이전의 태초, 사회화되기 이전의 인간에 대해 생각하는 책. [“In the beginning before light, a book that thinks about people before they became socialistic.”]

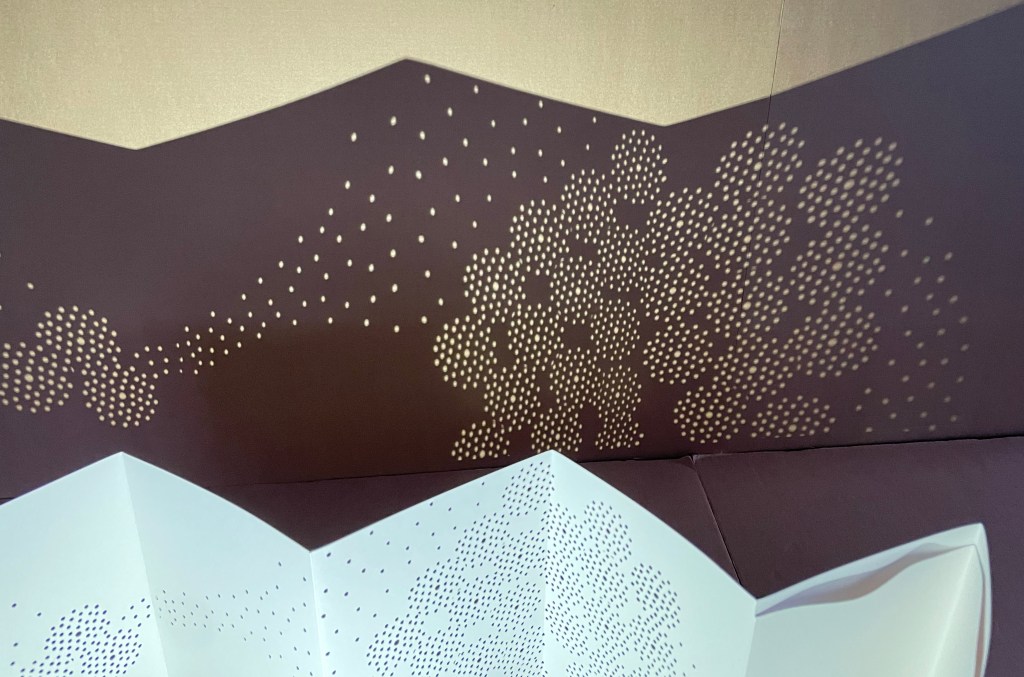

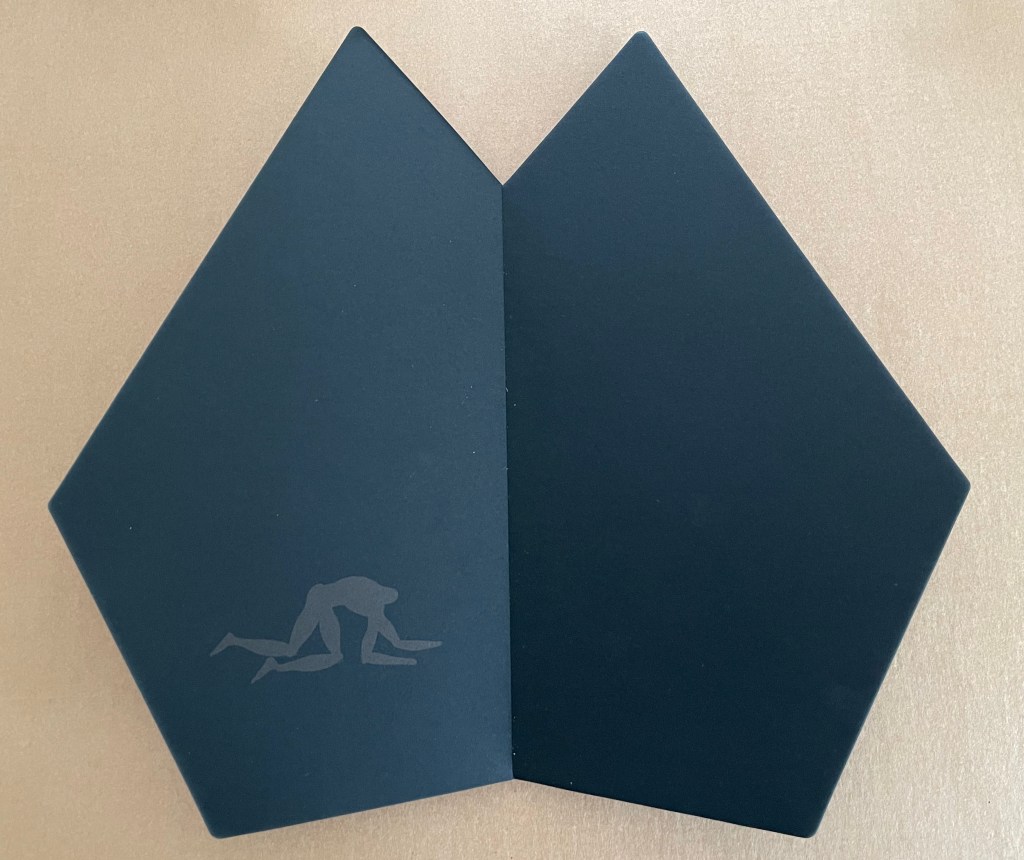

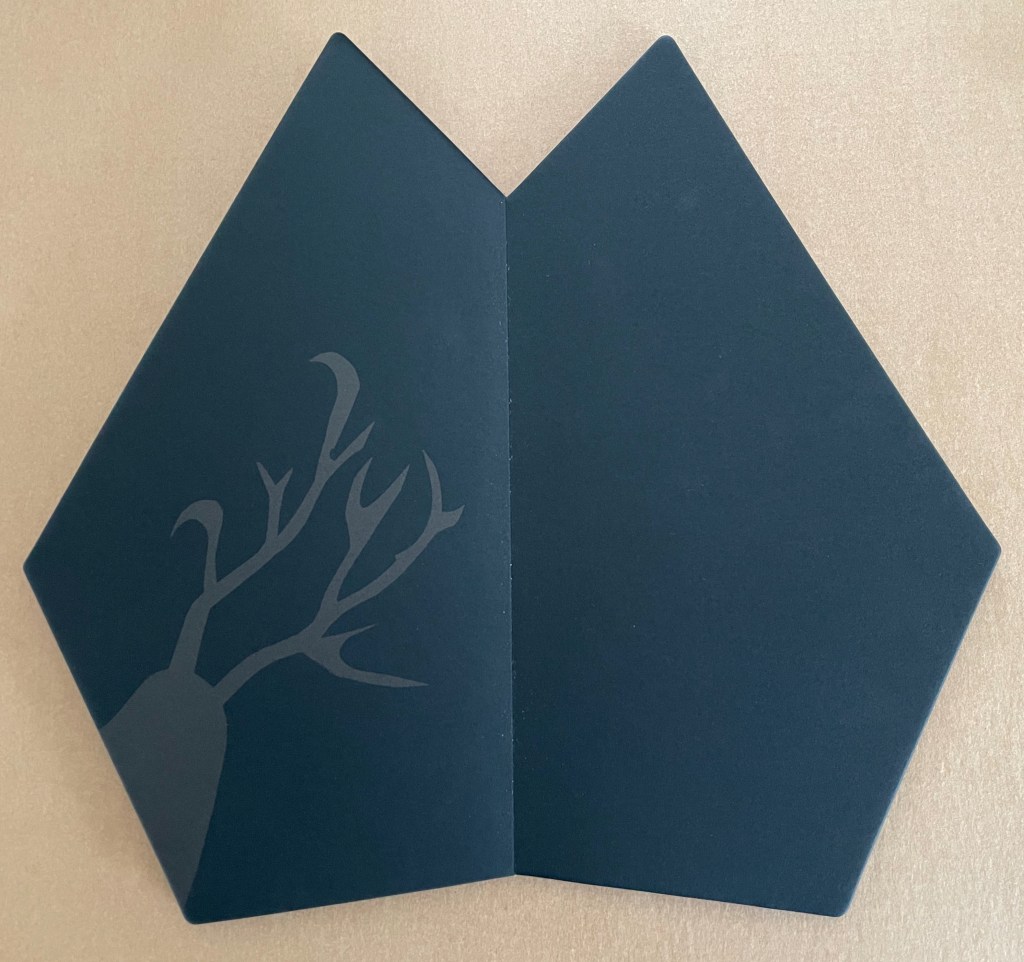

A translation that resonates more with the paper, structure, and images might be “A book contemplating the primordial state of the human before light and socialization.” Such a book would, of course, not have the normalized appearance we enlightened and socialized humans expect. Hence the black oddly shaped covers and leaves across which the gray, almost headless creature crawls on all fours and begins to sprout antlers or branches.

When other creatures enter the primordial state, they are oriented to it differently, which our branch-headed forebearer notices and tries to assume but fails.

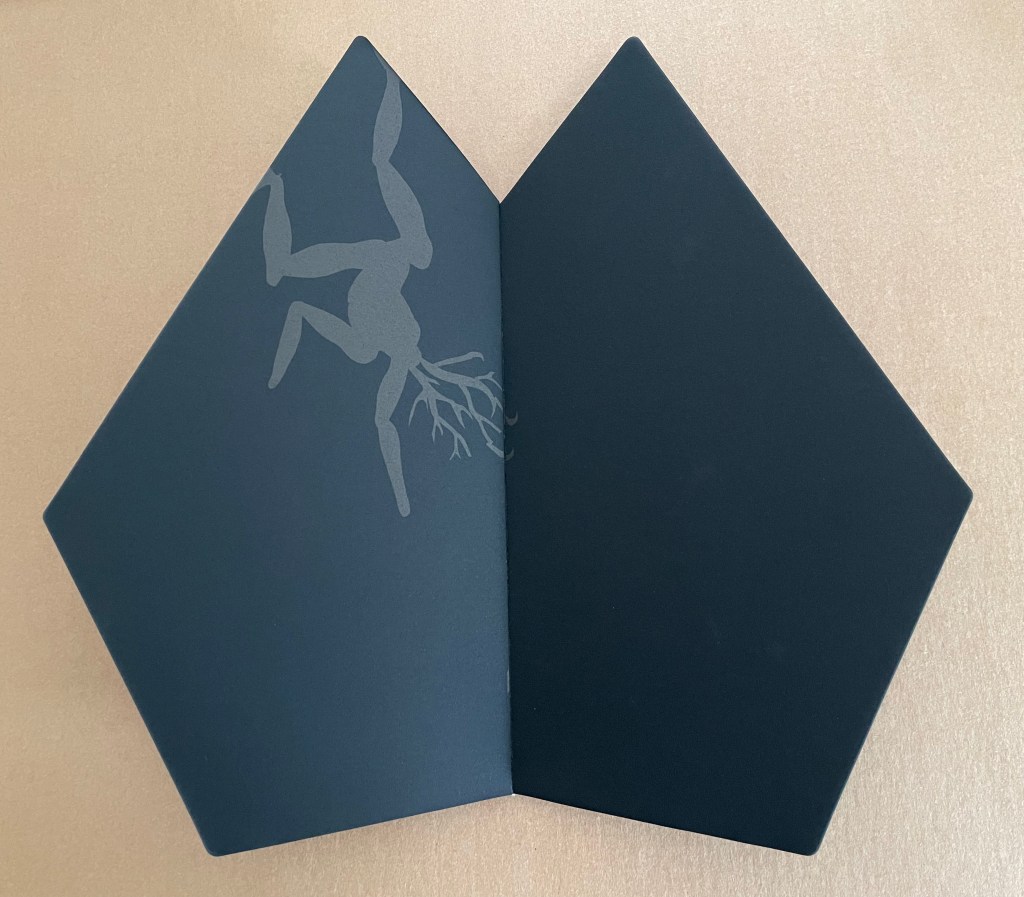

Having failed, our precursor tries to merge with one of the other creatures, but this elephant-like being will have none of him and flings the proto-human off.

Whereupon, branch-head seeks affiliation with the vegetable kingdom and climbs toward the top.

Having reached the top, our forebearer confronts and succumbs to the source of light and, having fallen and lost the semblance of antlers or branches (or both), yearns with arms outstretched for what once was.

The book’s unusual shape recalls Helmut Löhr’s Visual Poetry (1987), Kevin Osborn’s Tropos (1988), and Philip Zimmermann’s High Tension (1993), where likewise the shape contributes to meaning.

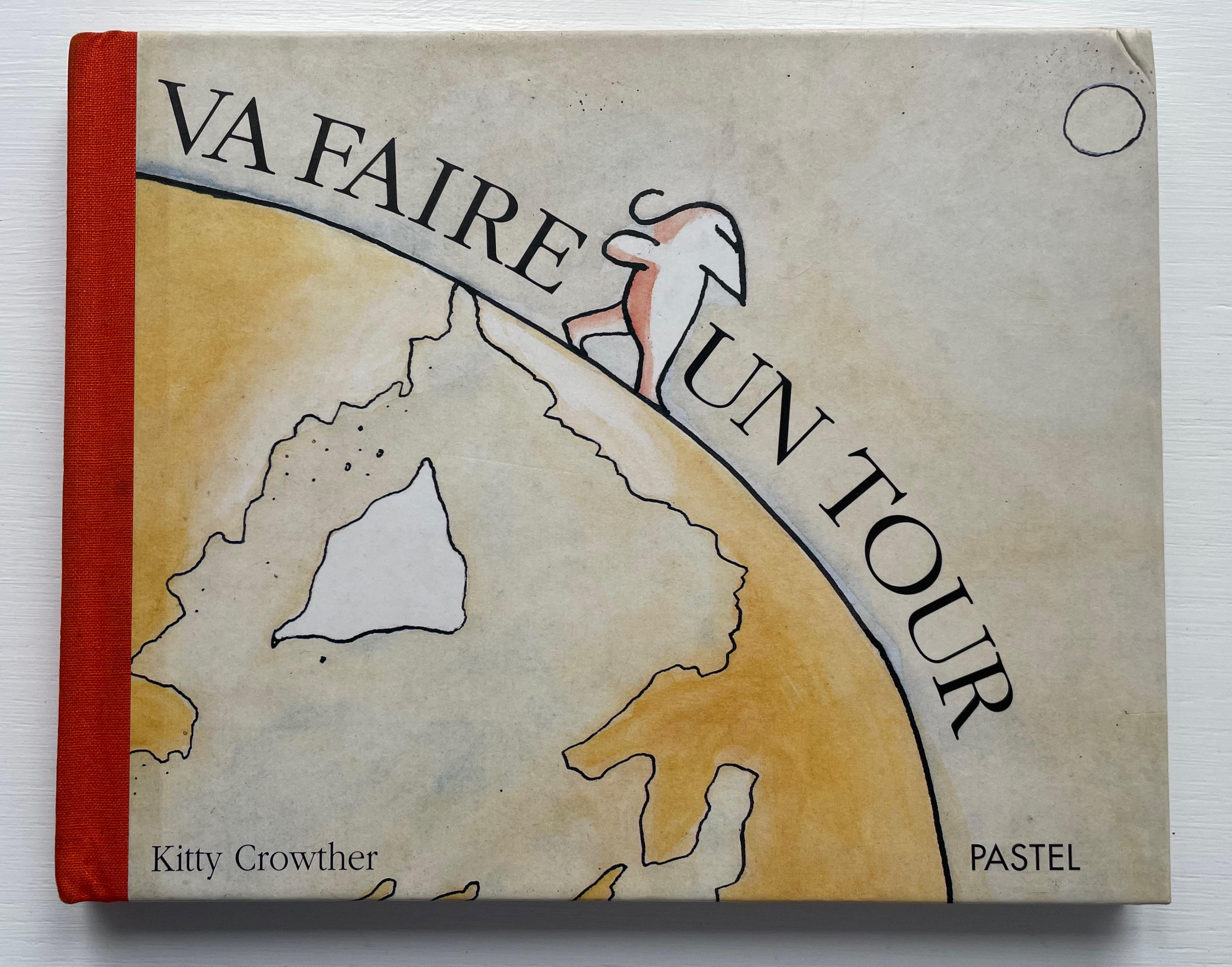

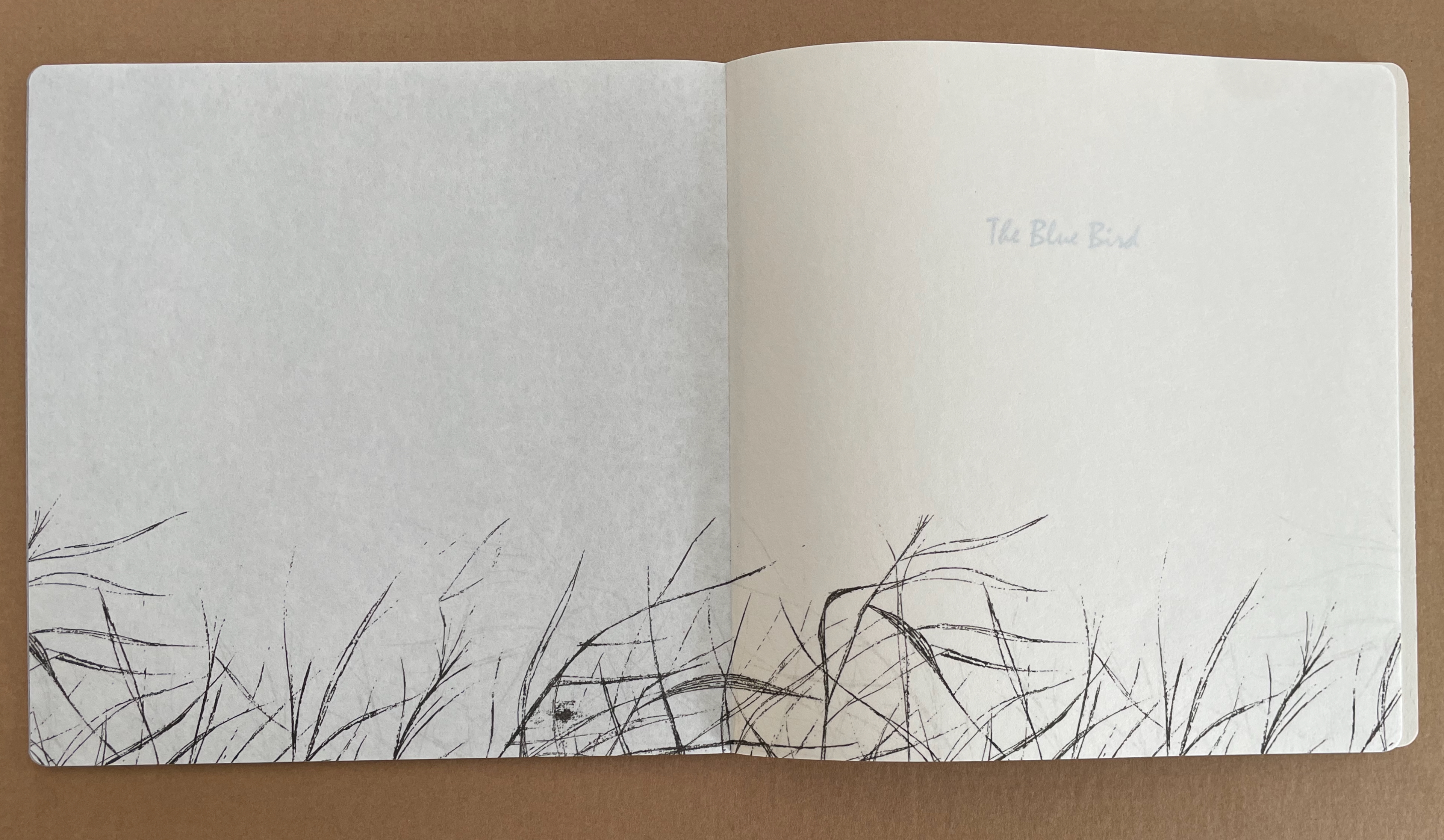

The Blue Bird (2011)

The Blue Bird (2011)

Sunkyung Cho

Exposed spine binding with cross weave filament tape, board-covered. 200 x 200 mm. [40] not including 2 illustrated fly leaves. Acquired from SpazioB**K, 6 April 2025.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

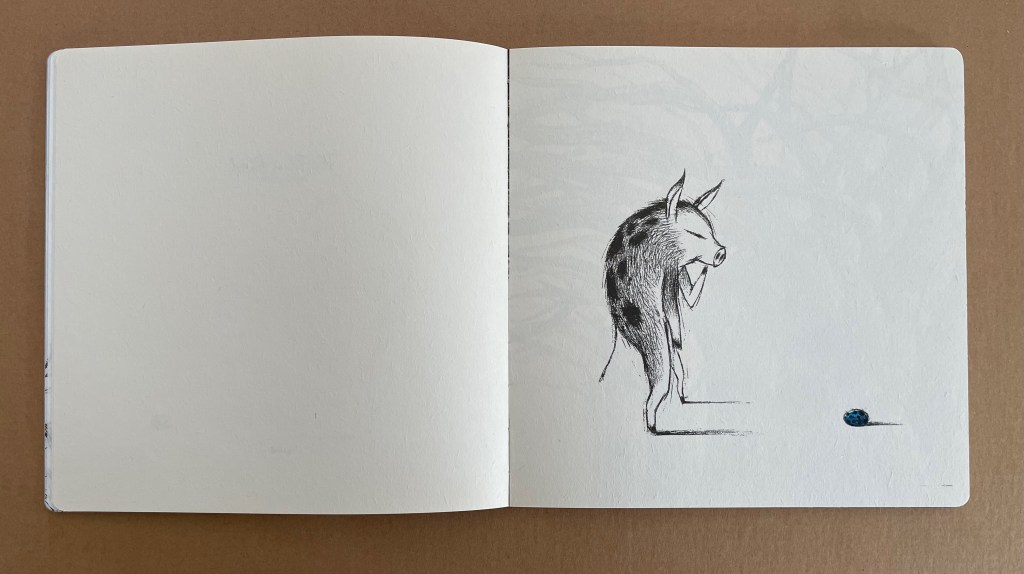

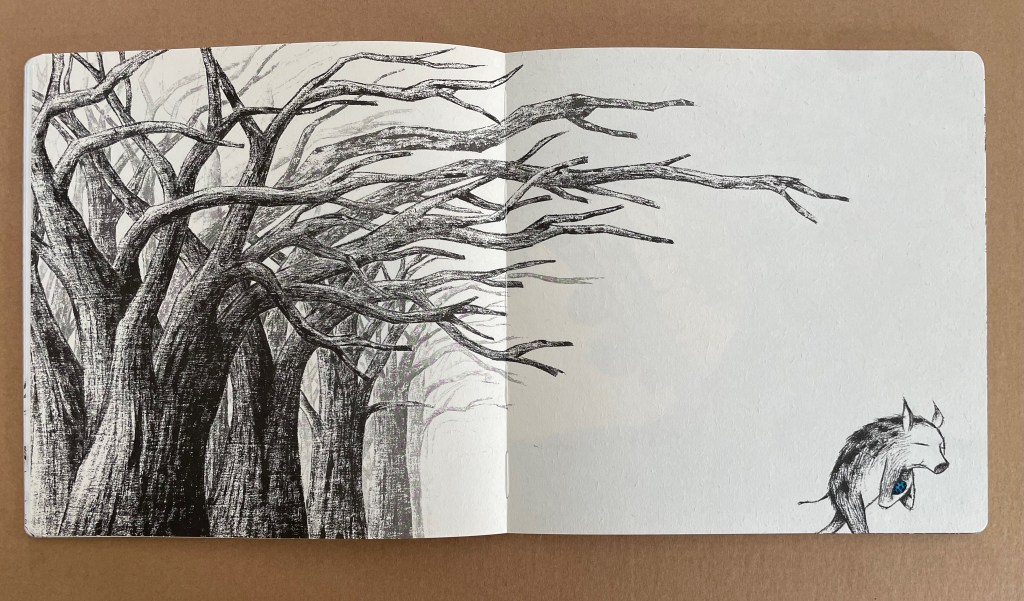

The Blue Bird leans much more toward the children’s book end of the crossover spectrum than in the beginning. The website’s description of it — “Blue Bird and Boar’s story of how to be a child and parent” — underscores all of the physical evidence except for the delicate nature of the paper. It is hard to imagine a copy surviving childhood use. But that might well be in keeping with the tender mix of joy and sadness in the tale.

The simplicity and evocative sophistication of composition and line eliminate the need for any words to carry the narrative. In the sequence below, Boar’s protective parental handling of the egg against wind and wave ends in predictable exhaustion and birth.

The remainder of the book in which Boar introduces Blue Bird to the world of foraging, running, jumping, sky- and star-gazing is landbound. Boar climbs trees to let Blue Bird sleep there, but when returns to the ground to sleep, Blue Bird follows, preferring to nestle against Boar under the stars.

Boar’s continued efforts to teach Blue Bird about flight lead to a separation that some parents may not be ready to explain to a child.

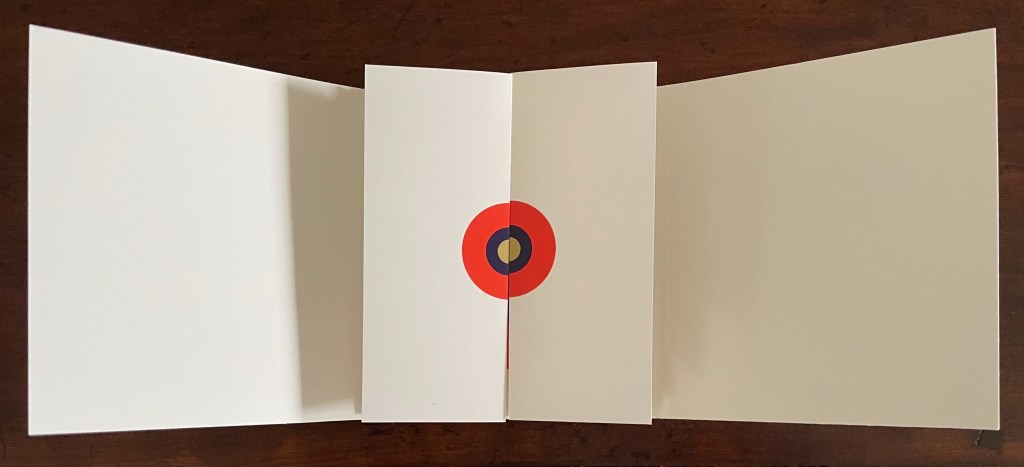

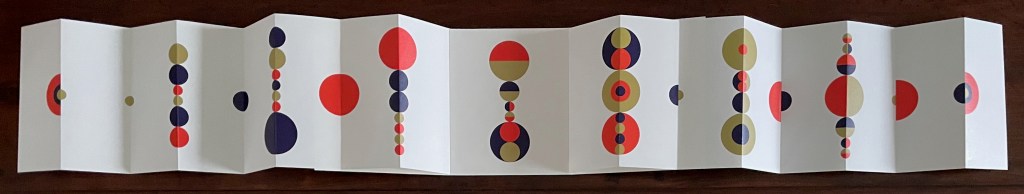

Kiss (2015)

Kiss (2015)

Sunkyung Cho

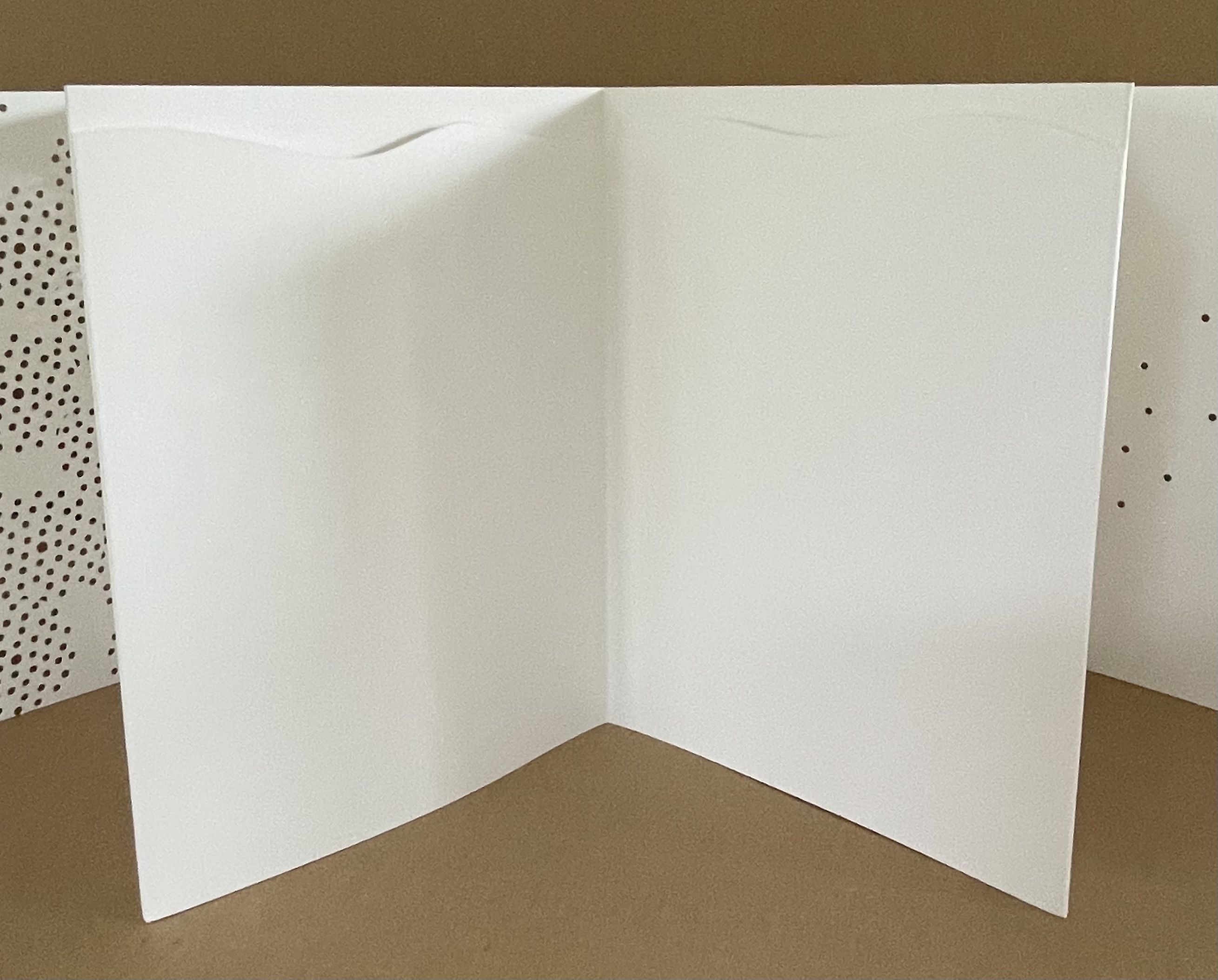

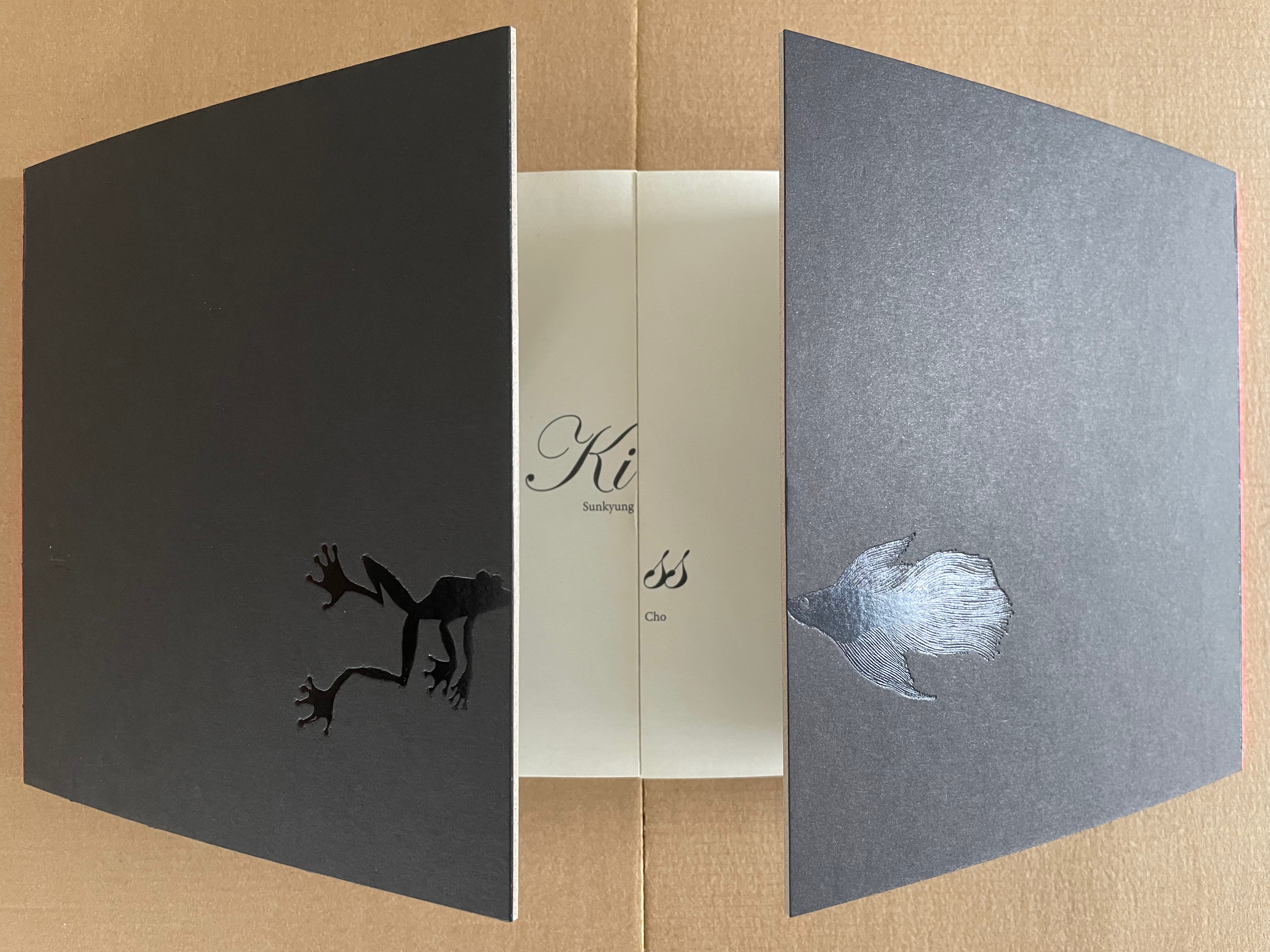

Board-covered books, bound face-to-face, exposed spine binding with cross weave filament tape. H200 x W400 mm (open); W800 (open). [16] Chinese fold folios. Acquired from Somebooks, 6 April 2025.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

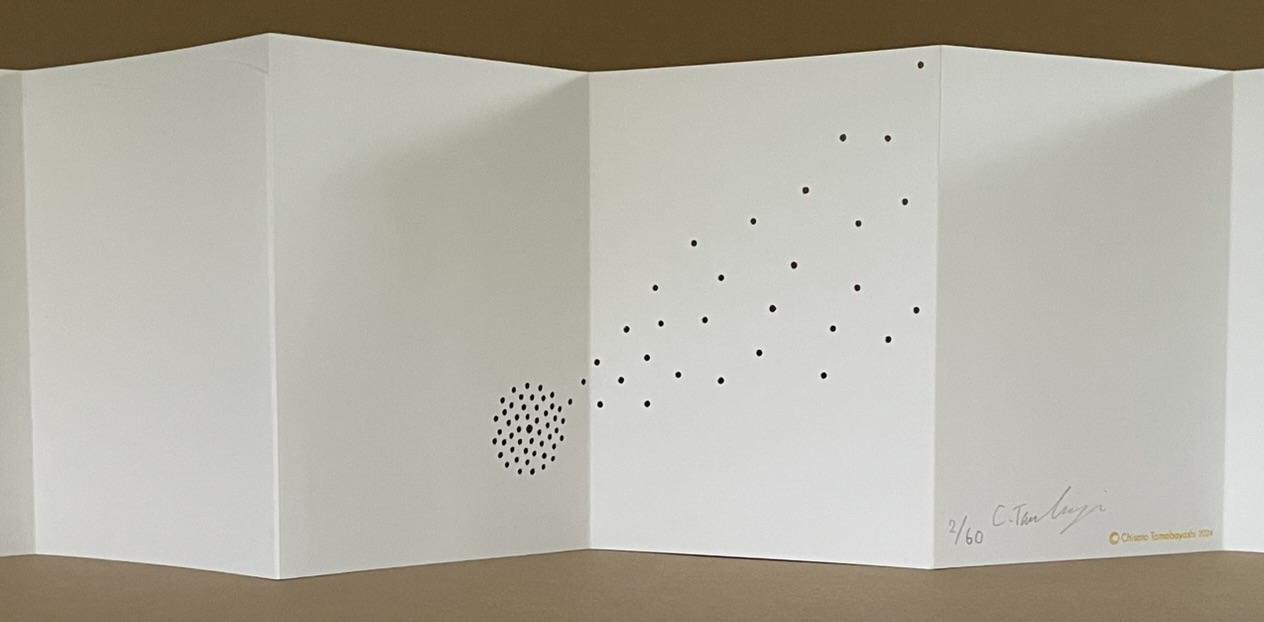

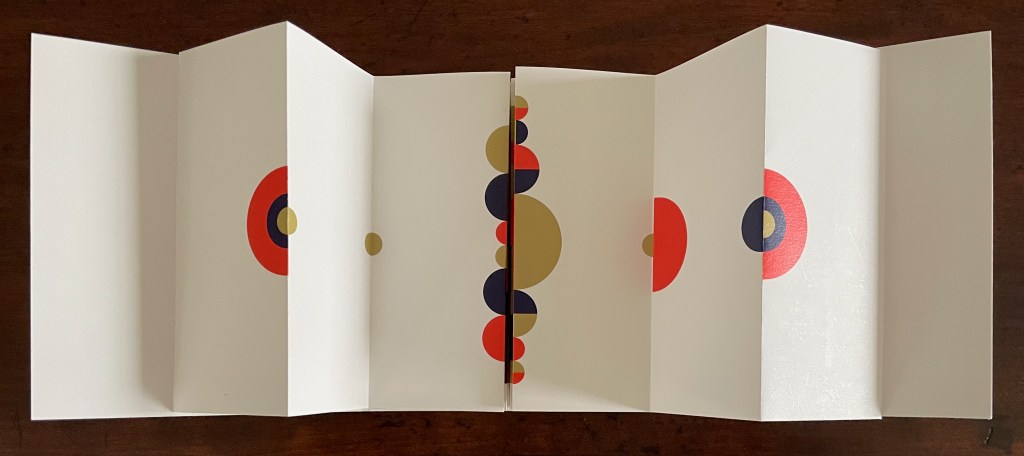

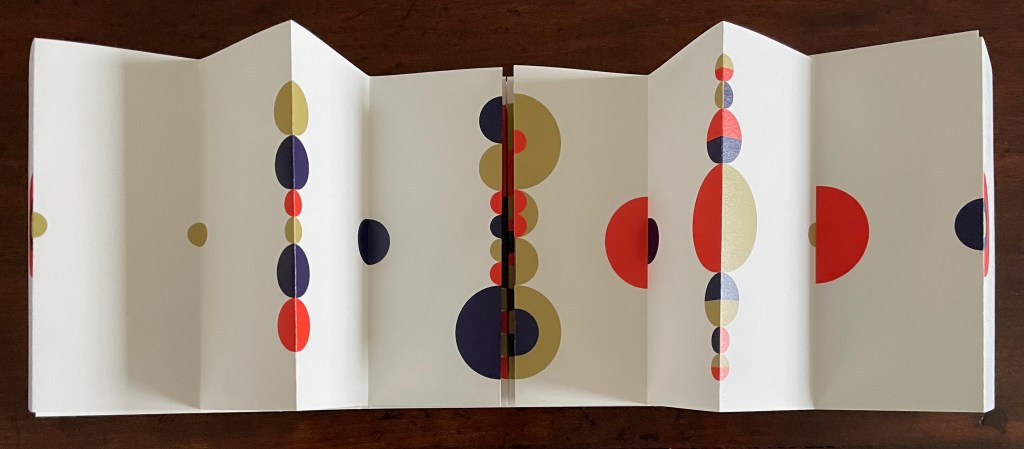

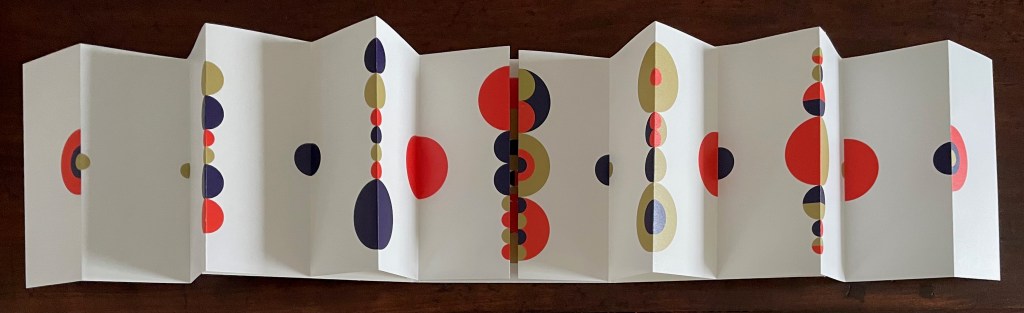

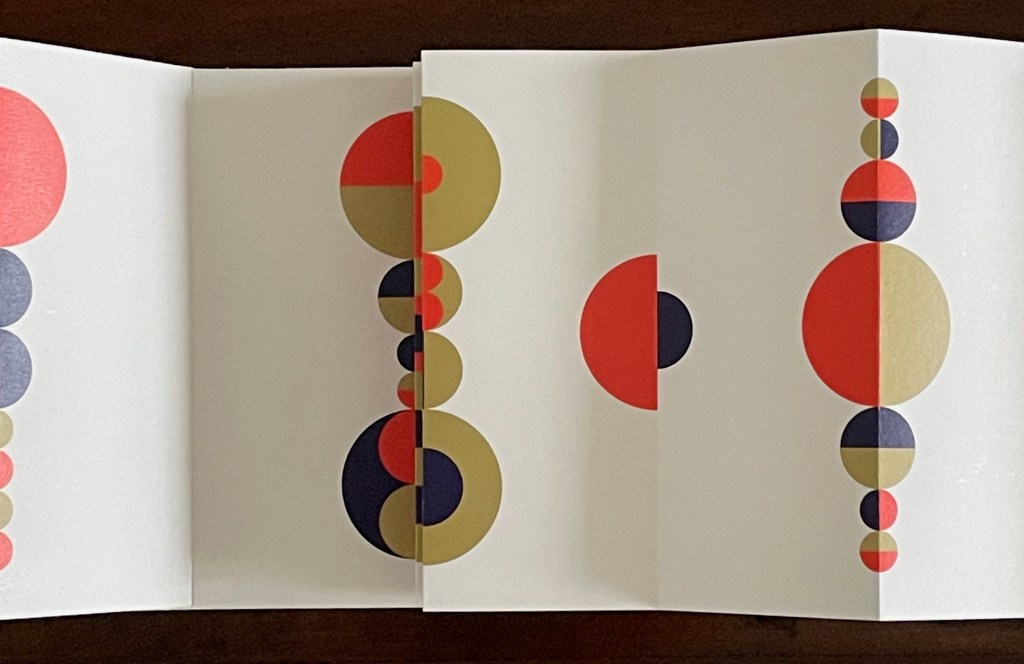

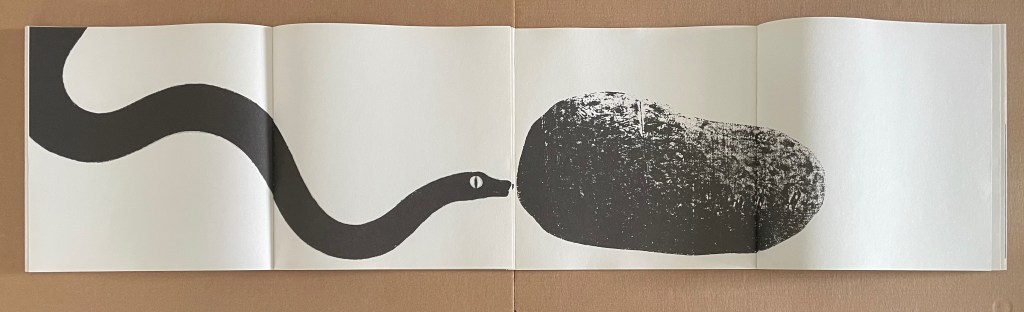

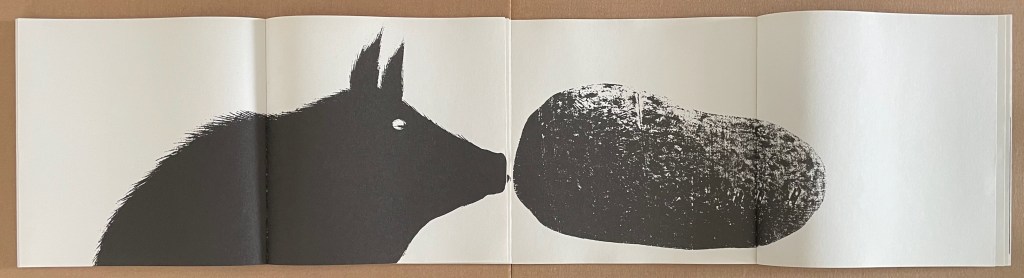

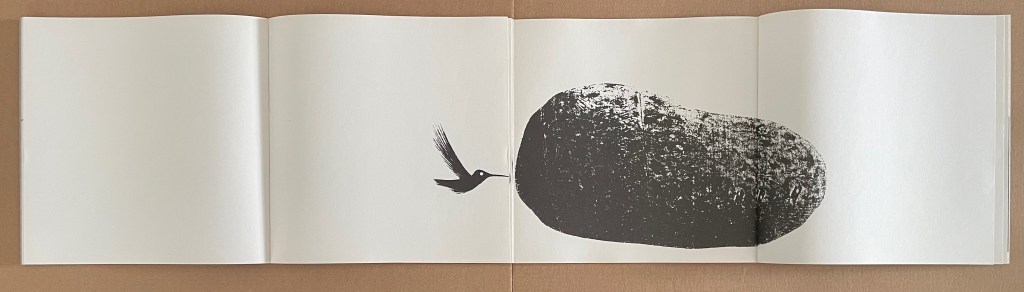

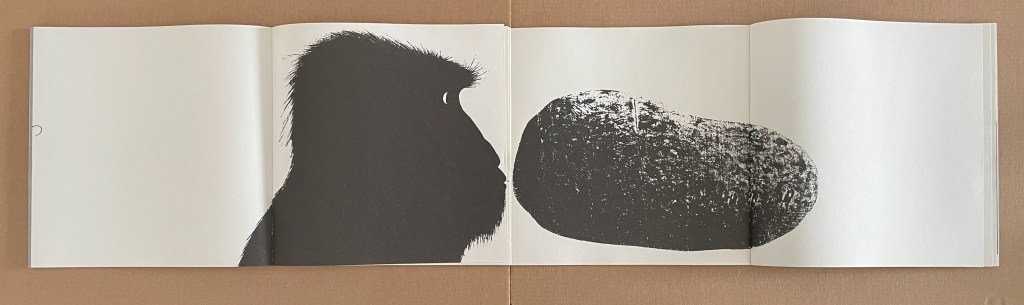

Kiss is far more whimsical. It works somewhat like a harlequinade, allowing multiple juxtapositions of images. The structure by which it does this is complex enough and the juxtapositions, subtle enough, that adult assistance is likely required. The book is actually two books joined at edges of their back covers, one opening to the left and the other, to the right.

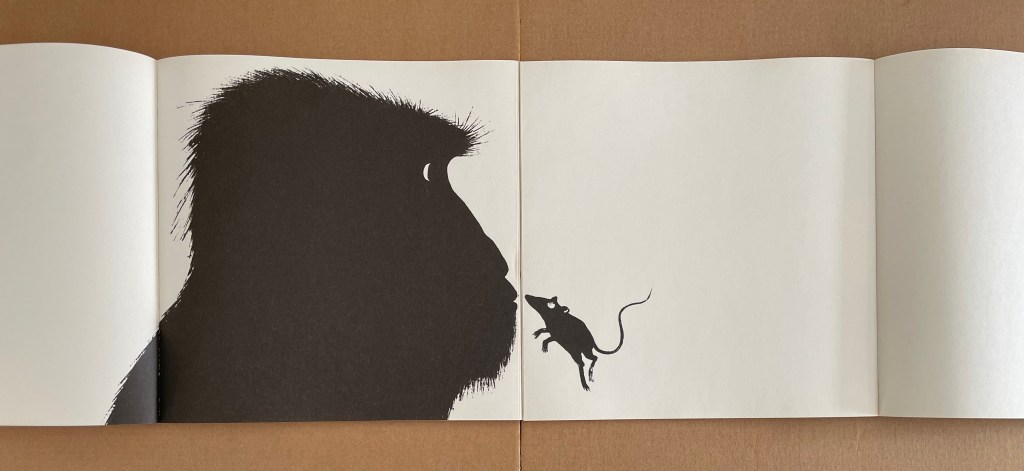

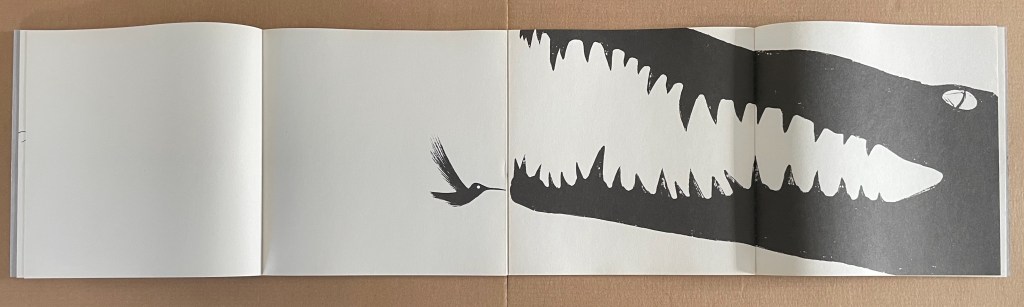

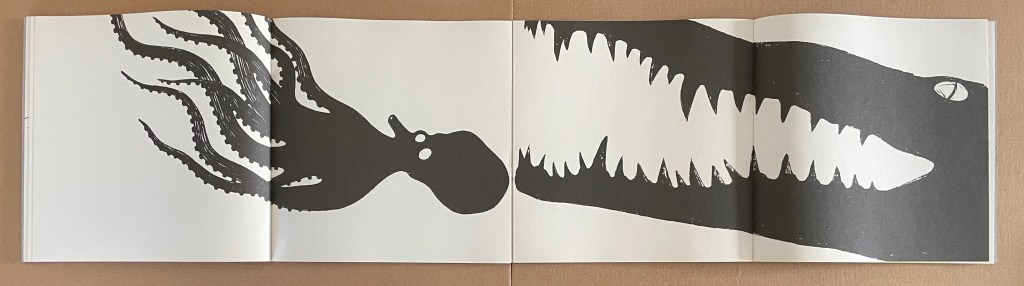

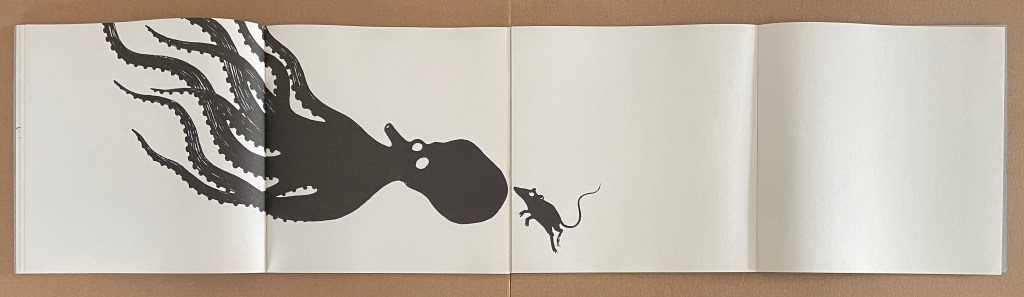

The precision of the registration between the facing books will generate delight as a gorilla kisses a mouse. The mouse kisses a bird. The bird, a crocodile. The crocodile, a gorilla or octopus. The octopus, a mouse or frog. And so on with sharks, snakes, and others.

Among the effective subtleties that more experienced observers will note are Cho’s handling of bleeds and the facing sets of double-page spreads. The large expanses of white behind each of any two smaller figures facing each other from single pages contribute to a non-threatening delicate kiss. The larger, more threatening creatures extend across their double-page spreads and even bleed off their pages. When they meet, or when one of them meets a smaller figure, there is an edge. It may be an edge of curiosity on one side or the other or both, but it is likely also one of threat and unease.

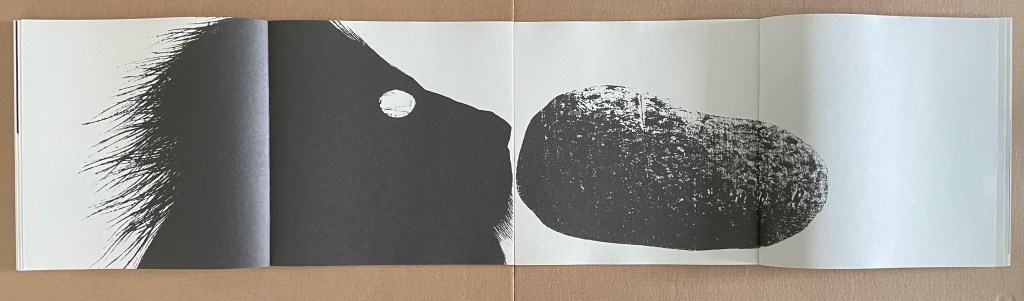

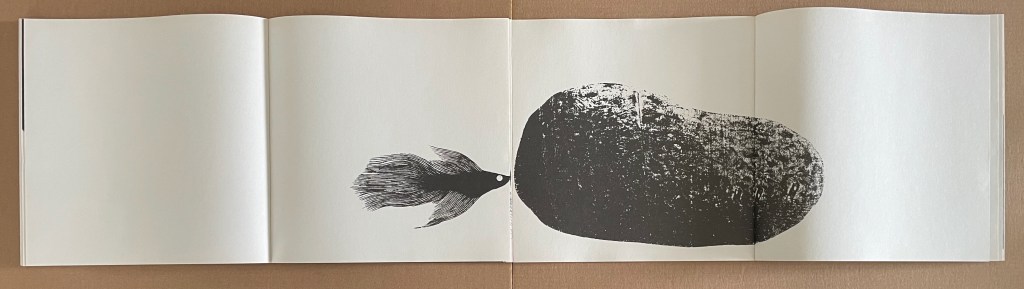

Another subtlety is the handling of the human figure. It occurs in the recto book. Like the smaller figures, it occupies a single page with a page of white behind it. It is expressionless, regardless of what it faces whether fish or lion. Oddly, the fish seems to be curious, and the lion, reserved.

Here is another subtlety that Cho raises. The last figure in the recto book is a stone, large enough to extend over its double-page spread. No doubt it is an anthropomorphizing tendency to read something (puzzlement, curiosity, annoyance, etc.) into the silhouette of each creature confronting the stone. But it is only the stone and human that exude indifference.

For an interesting structural, line and color comparison with another osculatory work, see Antonio Ferrara’s Ventiquattromila baci (Twenty four thousand kisses) (2021).

Further Reading

“Philip Zimmermann“. Books On Books Collection.

Beckett Sandra L. 2013. Crossover Picturebooks : A Genre for All Ages. London: Routledge.

Golden Pinwheel. 23 July 2020. “Cho Sunkyunk, the many faces of illustration“. Golden Pinwheel.

Haughton, Chris. 13 September 2011. “5 1/2 months on Sunkyung’s sofa“. chrishaughton.com.

Mutty. 12 May 2020. “Sunkyung Cho – Living Objects“. Art Tribune.

Nikolajeva, Maria, and Carole Scott. 2007. How picturebooks work. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Outlaw, Christopher. 17 April 2017. “FILBo 2017“. The Bogotá Post. Accessed 30 October 2011.

Perkins, Stephen. 7 March 2023. “Antonio Ferrara, Ventiquattromila baci (Twenty four thousand kisses), Settenove edizioni, Cagli, Italy, 2021.” Accordion Publications.

Scott, Carole. 2014. “Artists’ books, Altered books, and Picturebooks”. In: B. Kümmerling‐Meibauer, ed., Picturebooks: Representation and Narration. London, New York: Routledge.