The form of the book, the book as technological artifact, each of the book arts (design and layout, typography, illustration, papermaking, imposition, printing, binding, preservation and restoration) and even the book as an objet d’art attract memes — ideas, gestures, behaviors, methods, devices and practices that have spread from clay to scroll, from scroll to book, from book to ebook and perhaps from ebook to “cloud book.”

As we try to preserve – with clay counters in clay containers, with 0’s and 1’s stored on floating disks in tablets – we have assumed we are progressing.

Guy Laramée is a book artist, a subversive book artist. His “artist statement” articulates the meme of erosion, entropy and the dissolution of culture and knowledge — what he calls the “cloud of unknowing.”

Artist Statement

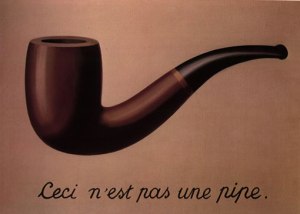

The erosion of cultures – and of “culture” as a whole – is the theme that runs through the last 25 years of my artistic practice. Cultures emerge, become obsolete, and are replaced by new ones. With the vanishing of cultures, some people are displaced and destroyed. We are currently told that the paper book is bound to die. The library, as a place, is finished. One might ask so what? Do we really believe that “new technologies” will change anything concerning our existential dilemma, our human condition? And even if we could change the content of all the books on earth, would this change anything in relation to the domination of analytical knowledge over intuitive knowledge? What is it in ourselves that insists on grabbing, on casting the flow of experience into concepts?

When I was younger, I was very upset with the ideologies of progress. I wanted to destroy them by showing that we are still primitives. I had the profound intuition that as a species, we had not evolved that much. Now I see that our belief in progress stems from our fascination with the content of consciousness. Despite appearances, our current obsession for changing the forms in which we access culture is but a manifestation of this fascination.

My work, in 3D as well as in painting, originates from the very idea that ultimate knowledge could very well be an erosion instead of an accumulation. The title of one of my pieces is “ All Ideas Look Alike”. Contemporary art seems to have forgotten that there is an exterior to the intellect. I want to examine thinking, not only “what” we think, but “that” we think.

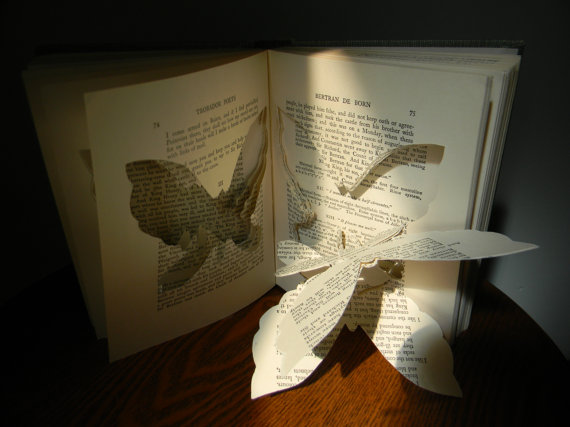

So I carve landscapes out of books and I paint romantic landscapes. Mountains of disused knowledge return to what they really are: mountains. They erode a bit more and they become hills. Then they flatten and become fields where apparently nothing is happening. Piles of obsolete encyclopedias return to that which does not need to say anything, that which simply IS. Fogs and clouds erase everything we know, everything we think we are.

After 30 years of practice, the only thing I still wish my art to do is this: to project us into this thick “cloud of unknowing.”

Guy Laramée

Is that the book’s evolutionary destination – in the “cloud”?

Further reading

Magnificent New Carved Book Landscapes and Architecture by Guy Laramée

“Guy Laramée’s (previously) new series Onde Elles Moran (Where They Live) captures the mystique of the native birds of the Brazilian region Serra do Corvo Branco (Range of the White Raven) through both portrait and carved landscape.”

Bookmarking Book Art – Exhibit at the Grosvenor Rare Book Room

Bookmarking Book Art — “Out of Print: Altered Books”, A Virtual Exhibition

Bookmarking Book Art – Update to “Rebound: Dissections and Excavations in Book Art”

Mihai, Cristian. “Showcase: Guy Laramée“, Irevuo, 31 March 2018.