A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley (2013)

A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley. An Illuminated Novel Written & Designed by Warren Lehrer (2013)

Warren Lehrer

Casebound, illustrated paper over boards with illustrated doublures. H254 x W198 x D28 mm. 300 pages. Acquired from Amazon, 3 March 2015.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

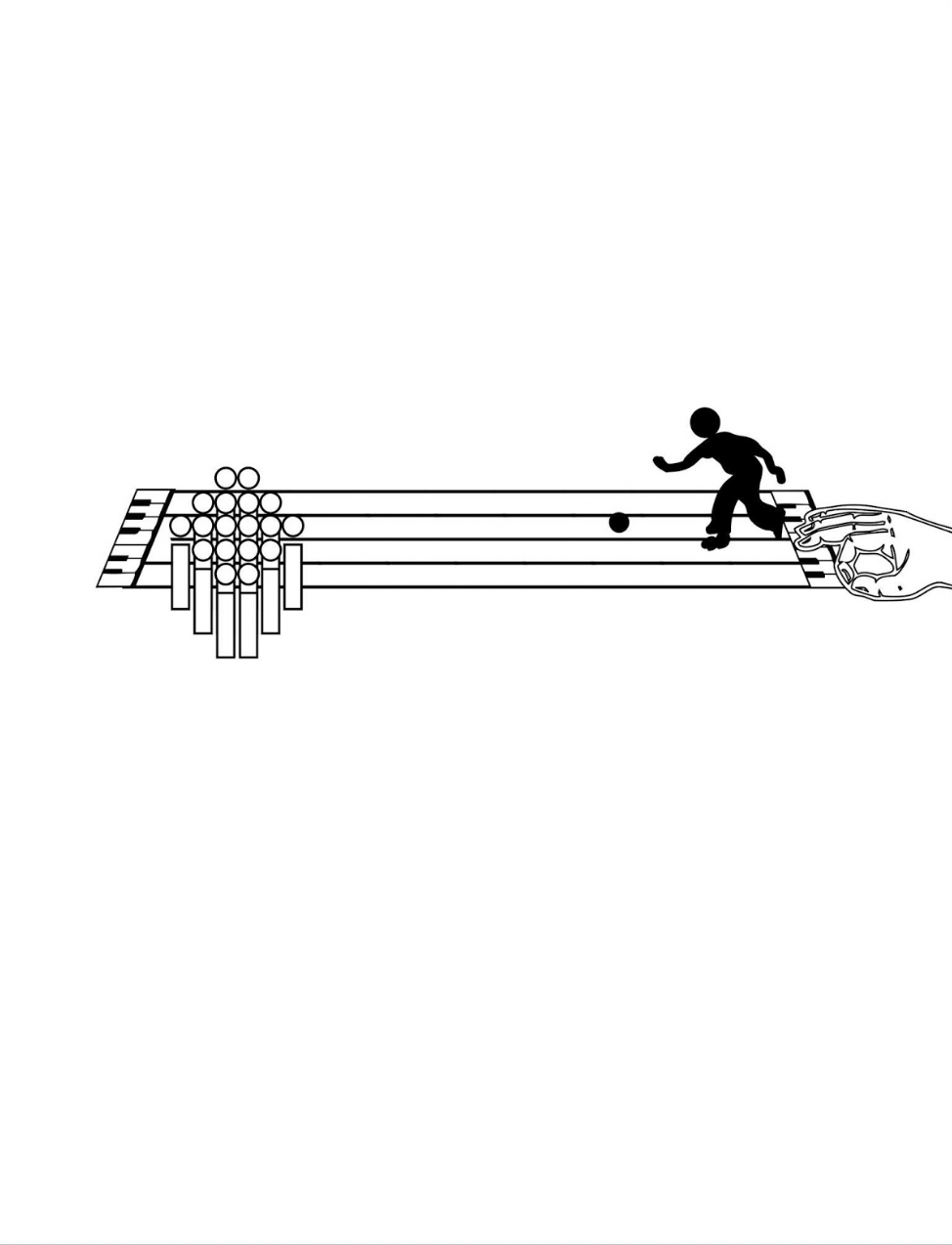

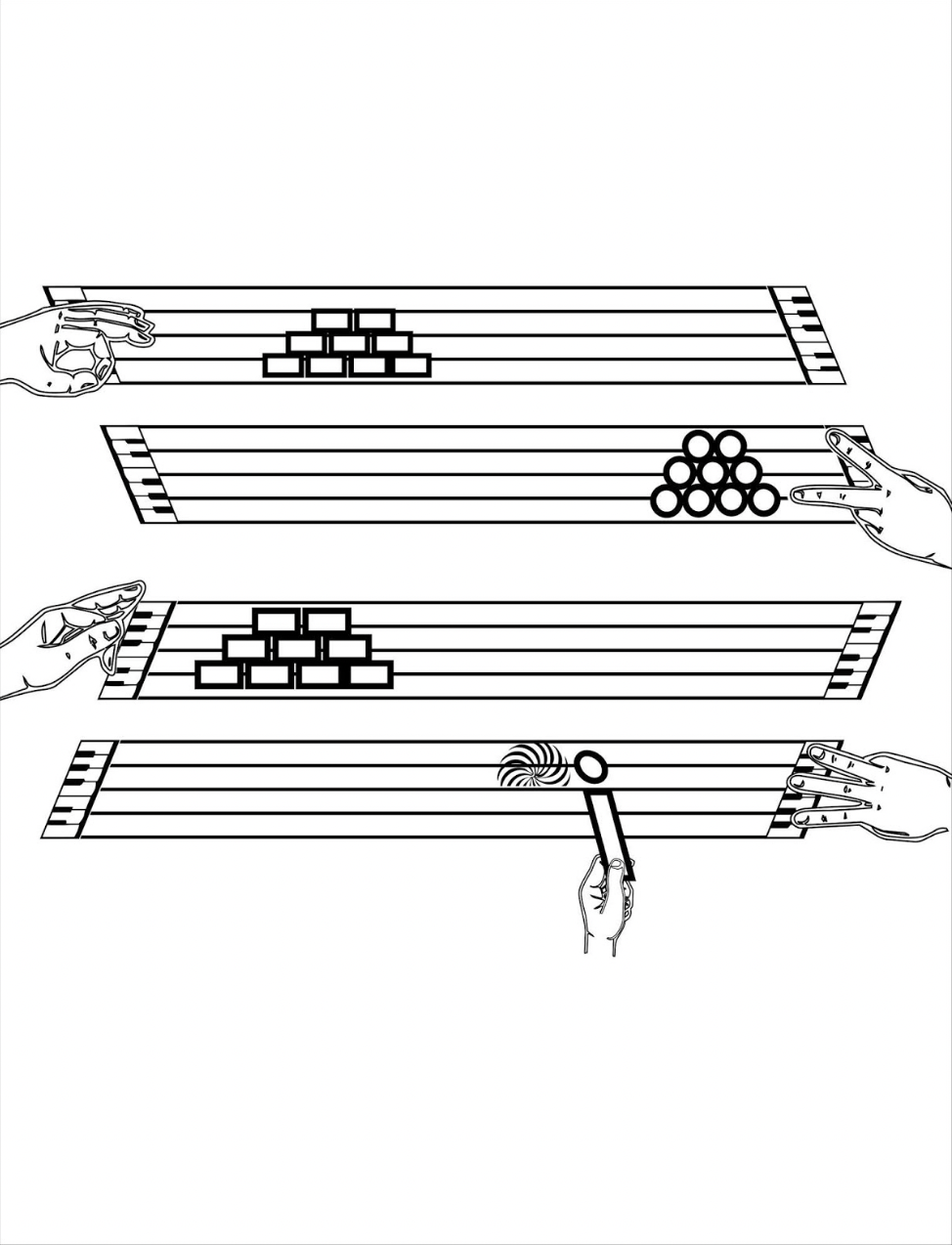

A Life in Books is the story of the fictional Bleu Mobley, writer, activist and jailbird, as compiled from Mobley’s prison tape diaries, his books’ jacket blurbs, excerpts from the books, and interviews by the non-fictional Warren Lehrer, writer, designer, performer, educator and citizen, presumably without a criminal record. What A Life in Books really is, though, is a satire on the book industry, bookmaking and book art and the broader social and political scene of the ’70s to the oughties in which it is set.

Each of nine chapters revolves around Mobley’s writing activities and publications, whose content reflects the winding narrative line of Mobley’s life (hence “a life in books”). Fiction, non-fiction and truth start the young Mobley on his oddball writing career, which throughout is characterized by a liberal cast of mind. Mobley is a feminist, anti-racist, environmentalist, pacifist, and anti-capitalist entrepreneur. Winding though it may be, the narrative line drives hard, and believe it or not, A Life in Books is a thoughtful, hilarious page-turner.

Mobley’s origins may remind some readers of John Irving’s The World According to Garp (1978), whose main character is also born out-of-wedlock to an artistic mother. Mobley’s parental puzzles lead him to his first handmade books: a miniature about his mother’s art and a series of dos-à-dos books with one side entitled “My Father” and the other variously entitled with a celebrity name. High-school journalism takes him into professional domestic and foreign reporting, which he quits before being fired for one too many metaphors and after which he begins his teaching and novel-writing career. Still pining for artistic integrity, Mobley experiments with handmade books. There’s a marriage portrait in a dos-à-dos format (two books bound back to back with a single spine) from which he progresses to a three-spine ménage-à-trois. There’s a Tom Phillips Humument-style artist’s book that Mobley makes by redacting his already-redacted FBI file obtained through a Freedom-of-Information-Act request.

Nevertheless he stumbles into financial success with the novel Buy This Book or We’ll Kill You (Maelstrom Limited, 1993), which becomes a bestseller after it has been transformed into a fast-paced crime comedy film reminiscent of Raising Arizona (1987). Mobley’s plan to leave teaching to pursue writing full time falls apart (seemingly) when he is felled by degenerative disk disease and starts down the entrepreneurial path to the equivalent of an artist’s workshop/studio to churn out even more quirky bestsellers. Instead of novels, as planned, the team first issues a successful series of self-help books under the name of Dr. Sky Jacobs, pop Zen psychologist under whose name Mobley wrote Yes, I Can’t: A How Not To Book (Simon & Schuster, 1995). The studio, however, does begin to produce Bleu Mobley fiction such as Outsourcing Grandma (Basic Books, 1999) and even a point-of-sale series of short fiction called The Check It Out Series (Bantam, 2000). All of these works continue to share a mash-up quality that is perhaps fundamental to book art, bookworks, artists’ books or whatever you want to call them.

Mobley’s works also share something else that he articulates only when his studio colleagues challenge the intentions behind his mash-up: End Times (Papyrus Books, 2000). Published as one of the first serialized online novels, End Times tells the story of a sex addict turned evangelical crusader (so is born the trans-genre of religious porn). Challenged to come up with one good reason to justify the book’s and its despicable character’s existence, Mobley responds “because it’s my Project“:

To paint a panoramic portrait of America — of humanity — one person at a time. Sort of like how Bruegel painted vast village landscapes populated by everyone in a village, and each person, no matter who they were, had a story. Only with my work, I suppose, the panorama won’t be complete till I write my last book. Even then it won’t be complete, but a reader could still go through all the books, zooming into the individual stories and out to see the bigger picture. So to ask me why I paint this person and not that one, or what it has to do with me, is sort of meaningless.

Underlying Mobley’s mash-ups, personae, and workshop/studio books, this humanism leads to that liberal cast of mind mentioned above, which draws Mobley to embrace every cause going. Unfortunately, there are plenty of traumatic encounters and personal affronts to encourage Mobley’s activist penchant. It is the combination of this activist penchant with his literary penchant for fictional non-fiction (or non-fictional fiction) that leads to Under the Rug: A Flush and Tell Book (Simon & Schuster, 2006). This White House cleaner’s behind-the-scenes account “of unseemly behavior, indiscretion, and hypocrisy as told … to bestselling author Bleu Mobley” lands Mobley in jail for contempt of court for not revealing his non-existent source.

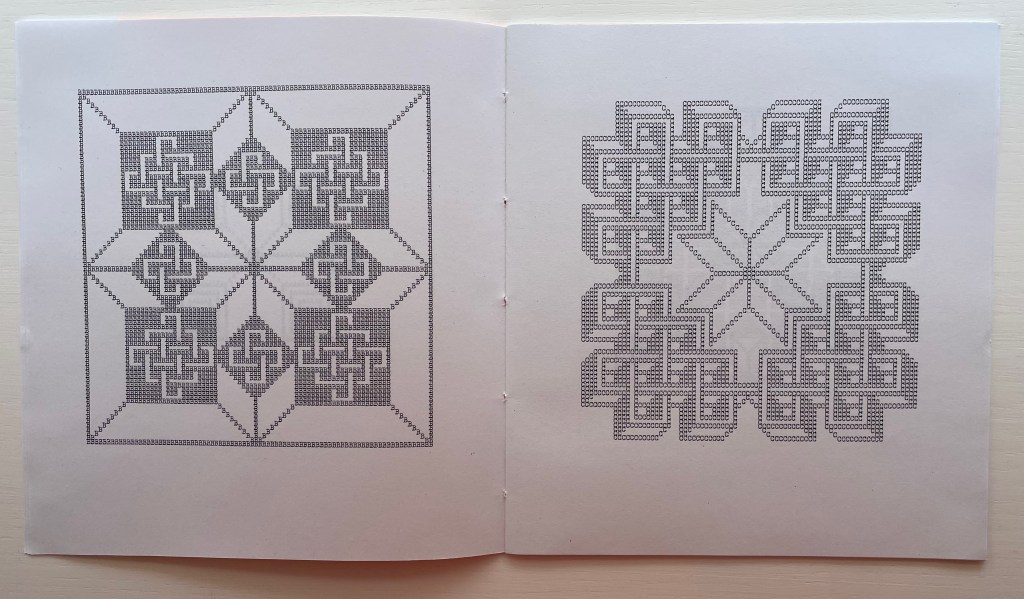

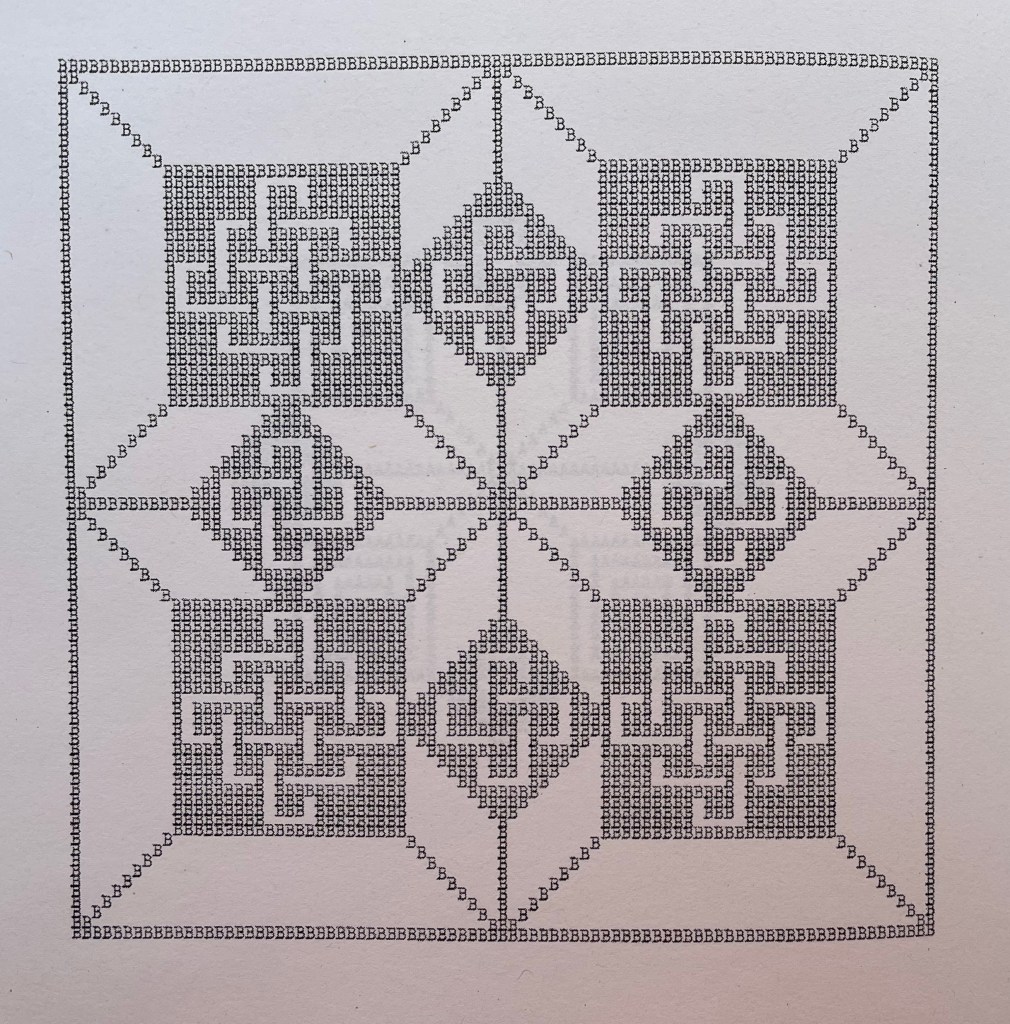

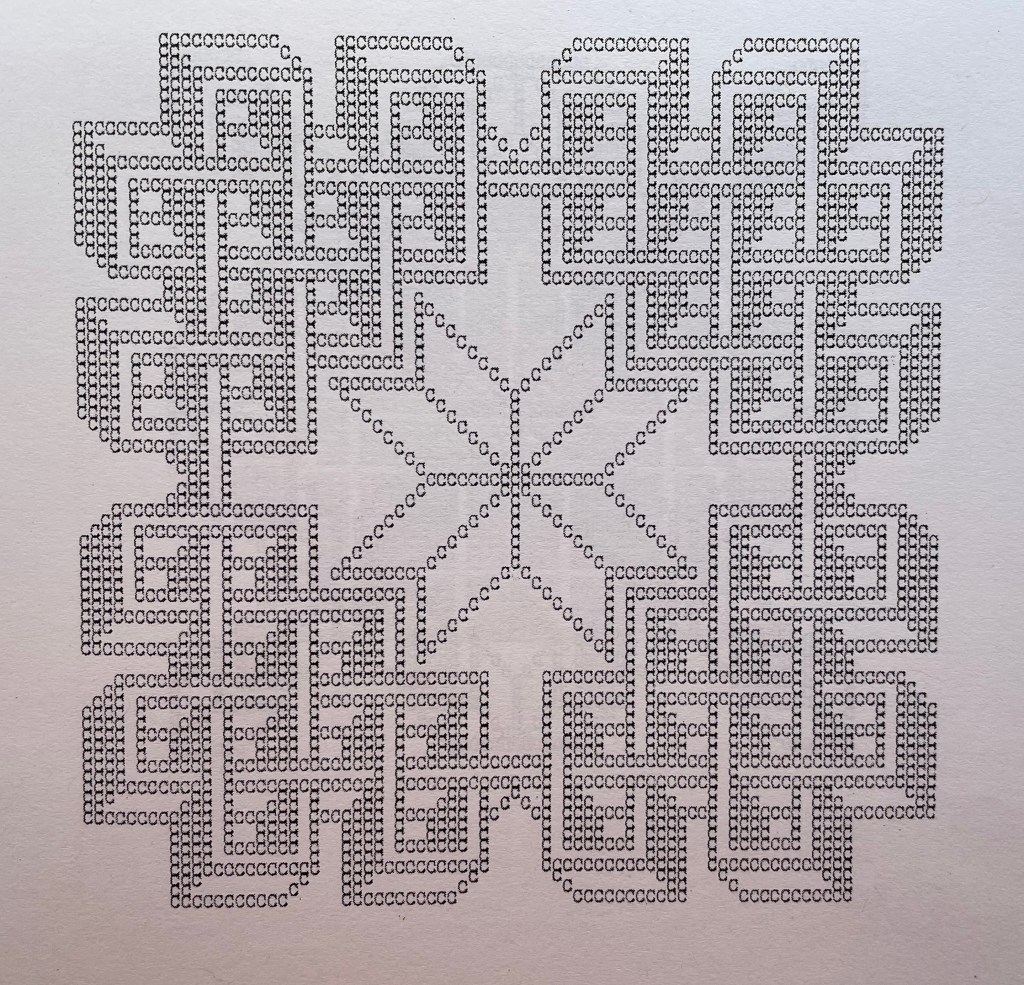

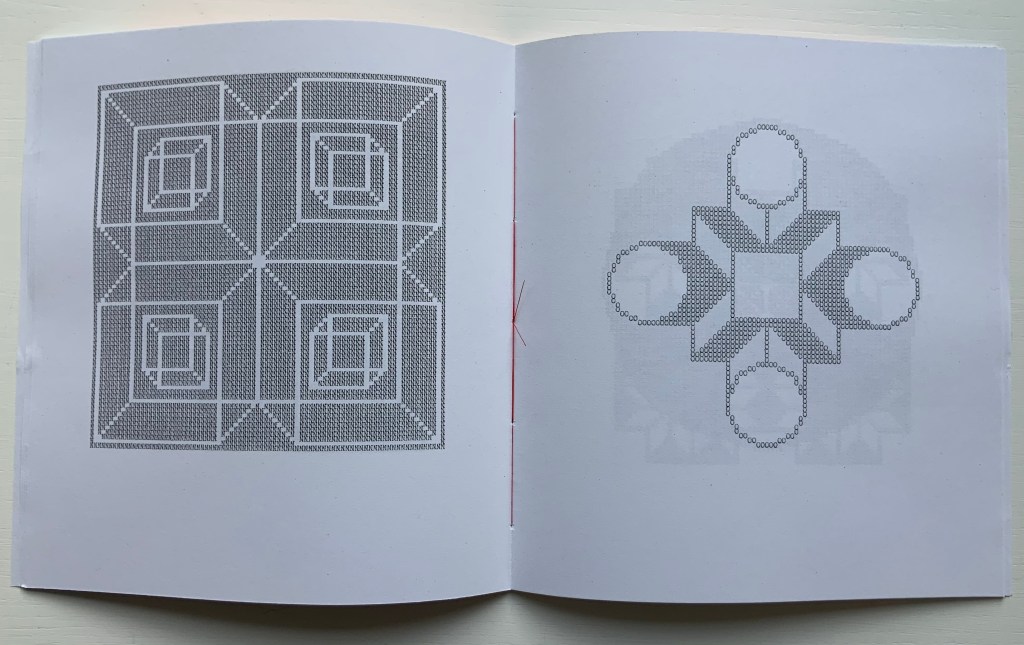

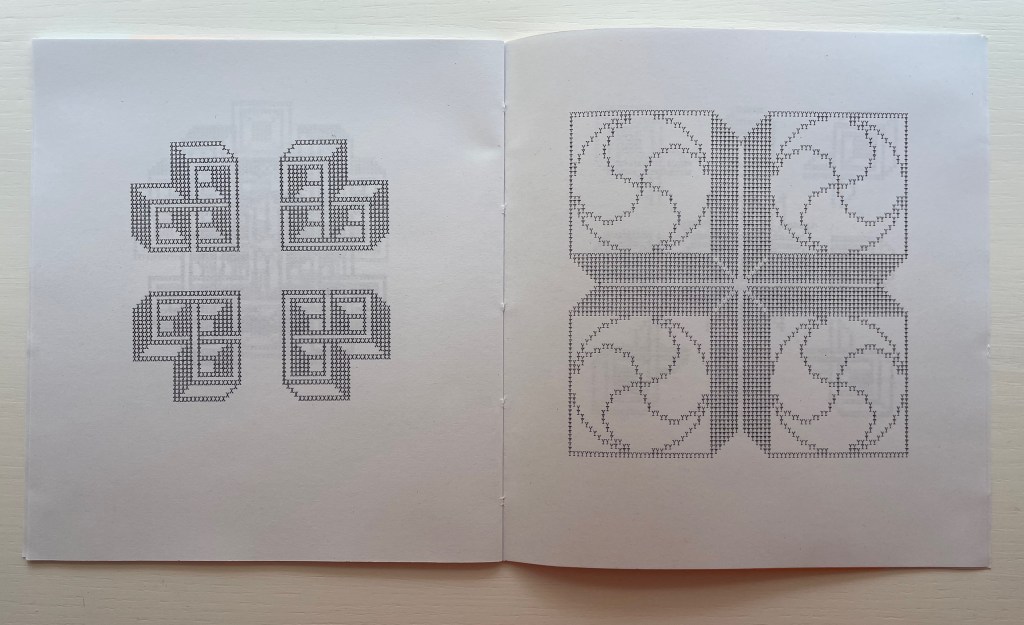

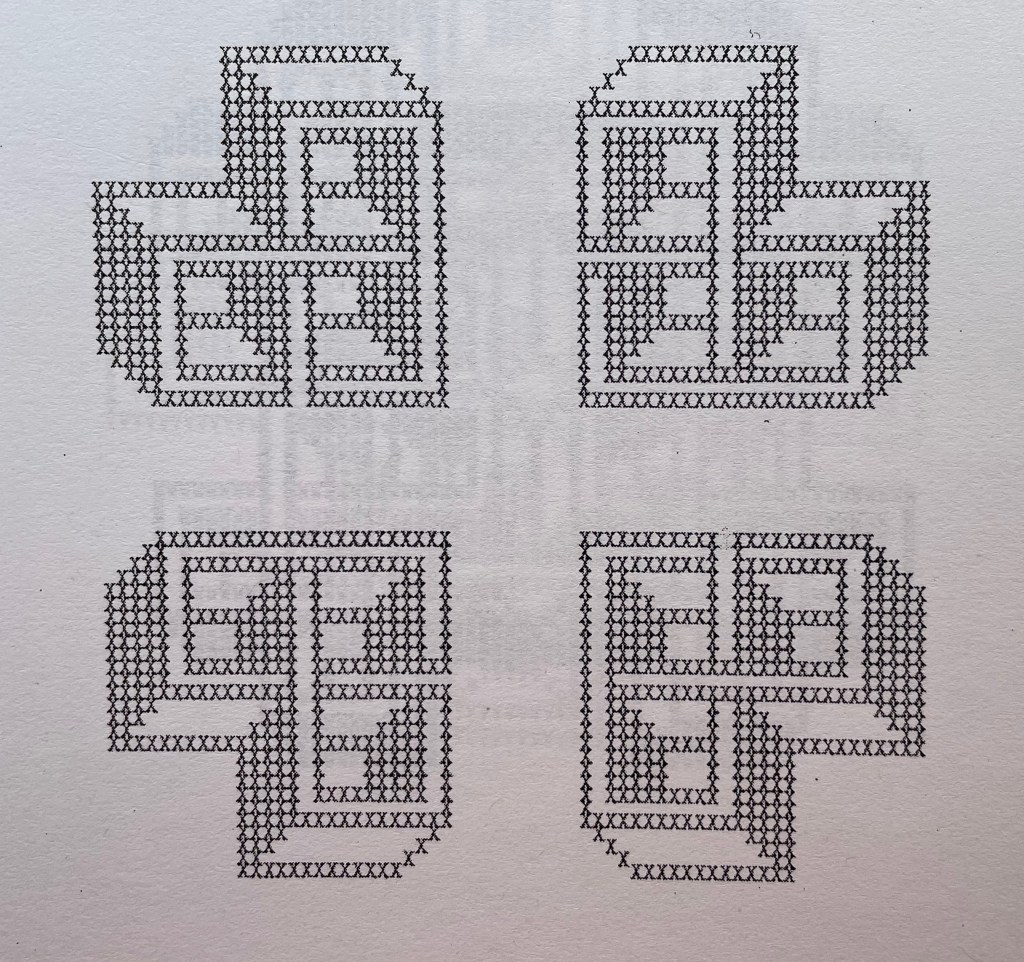

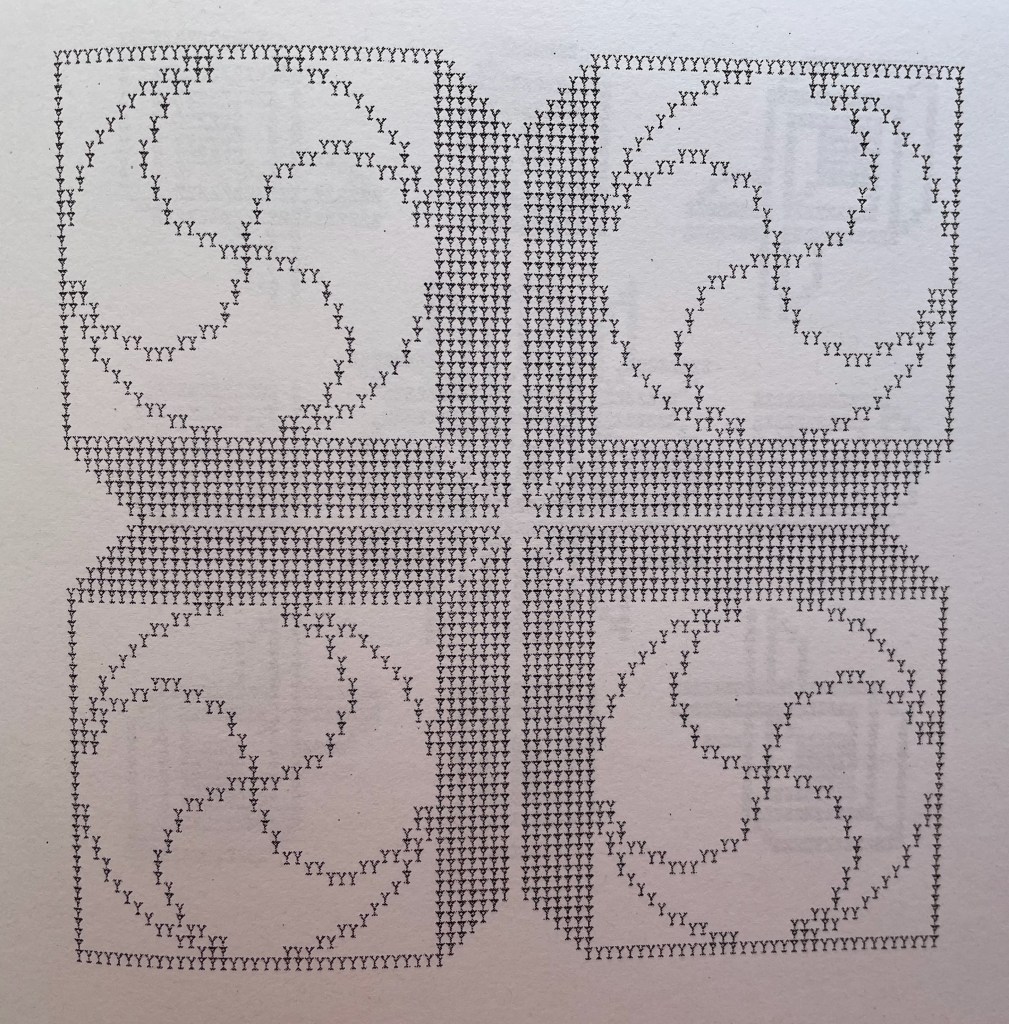

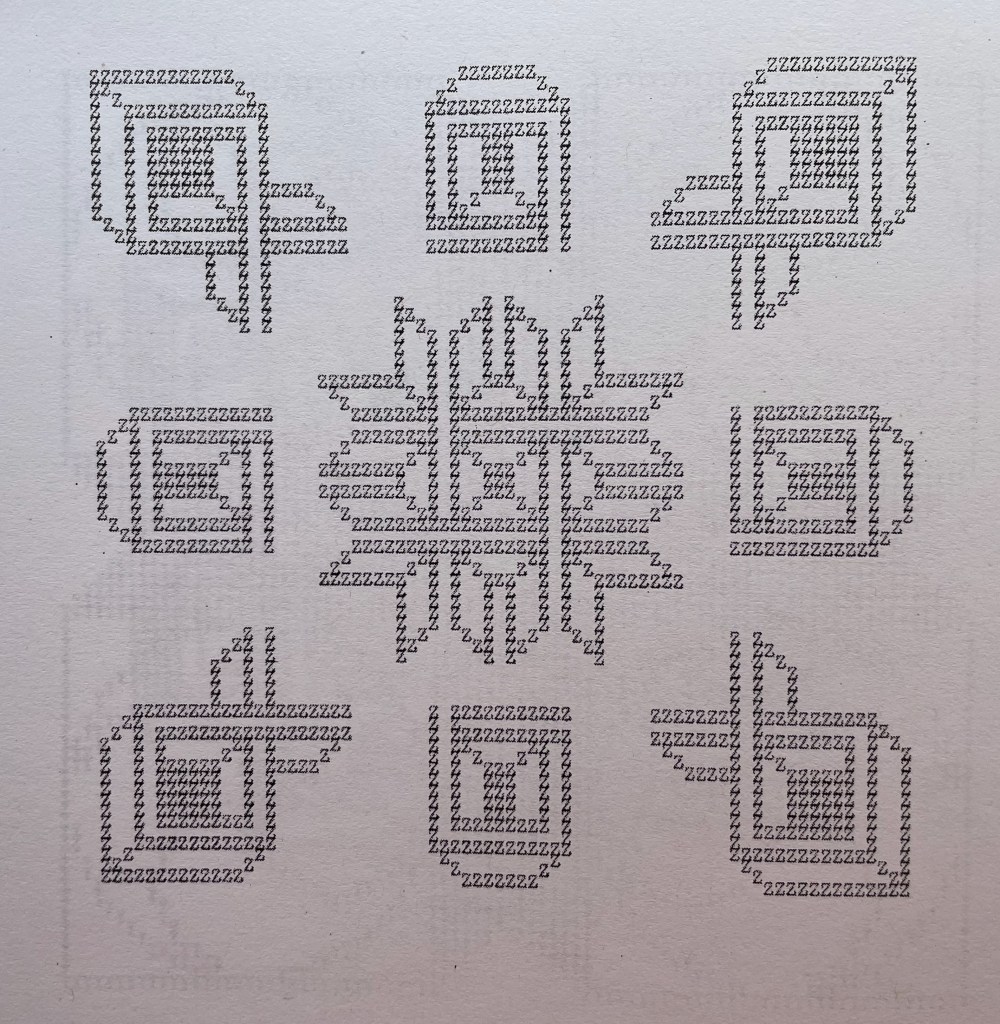

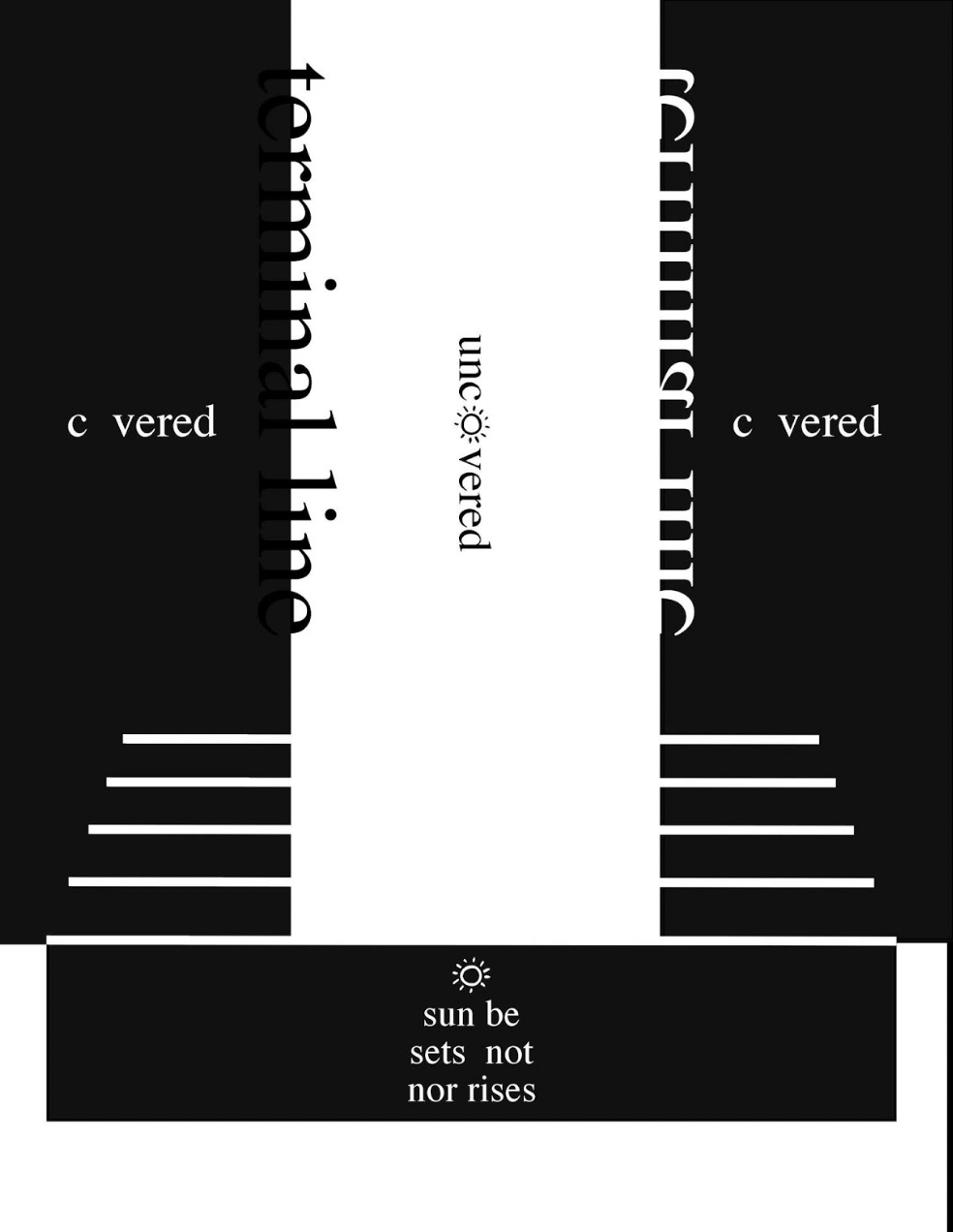

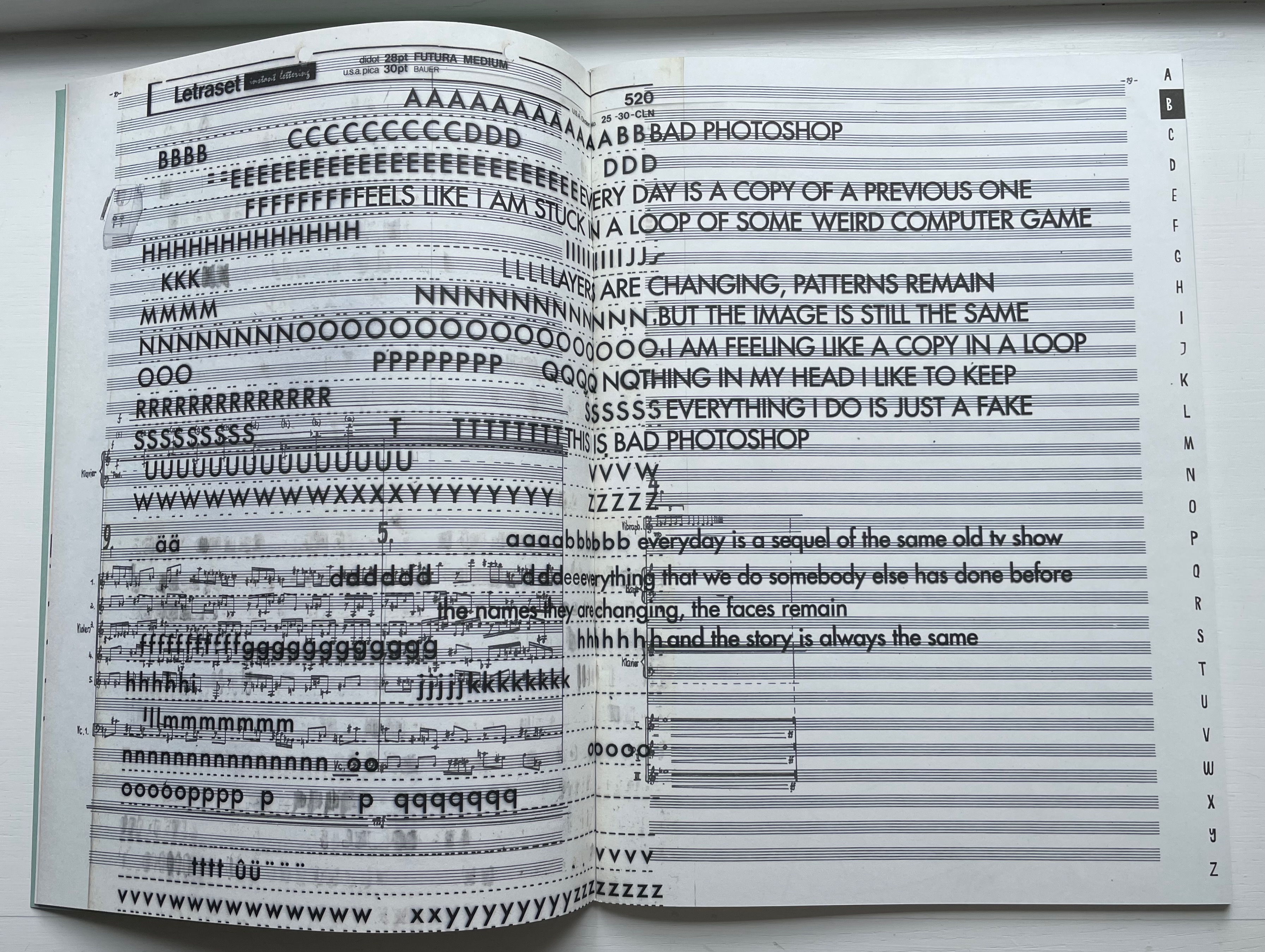

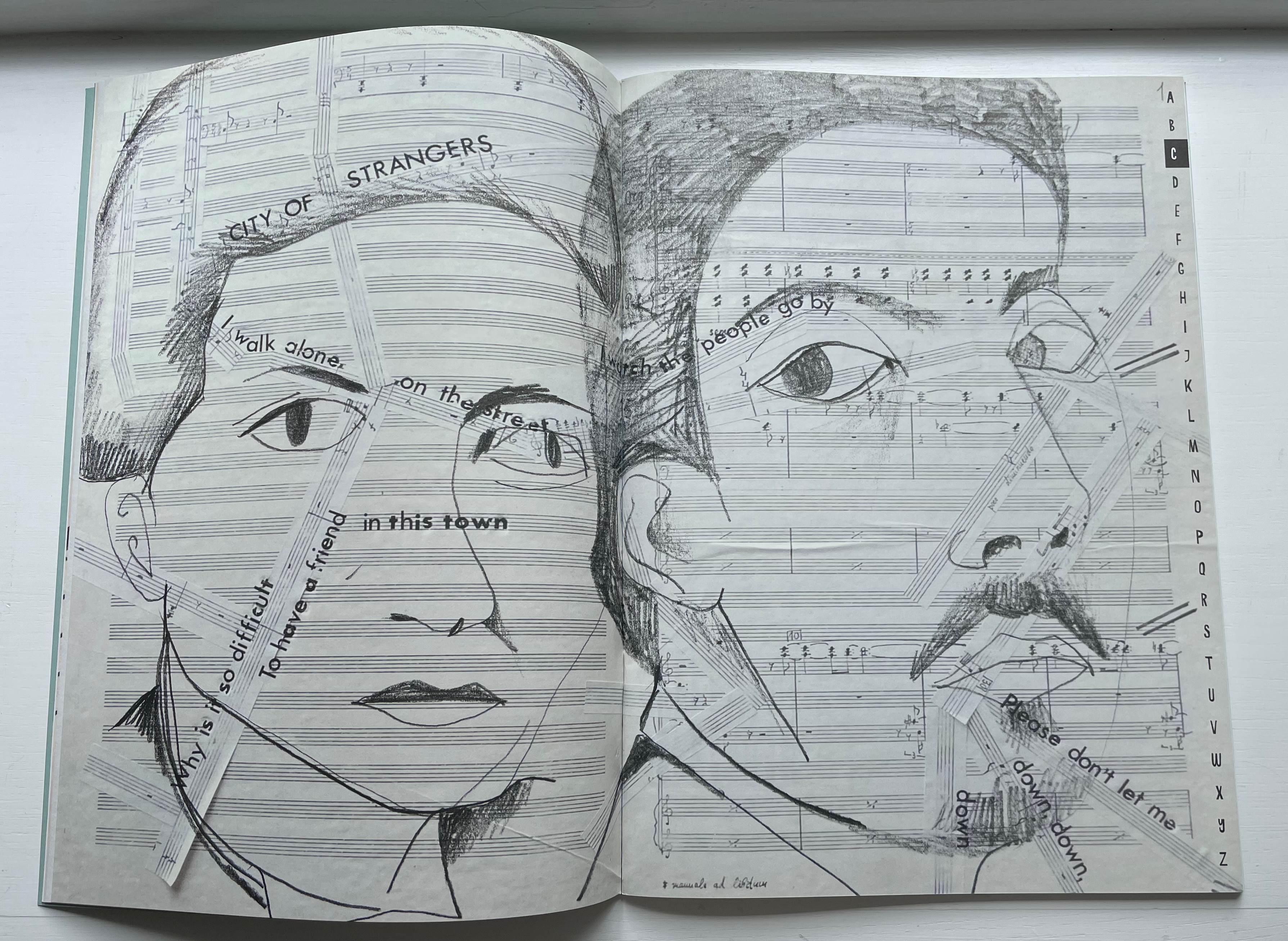

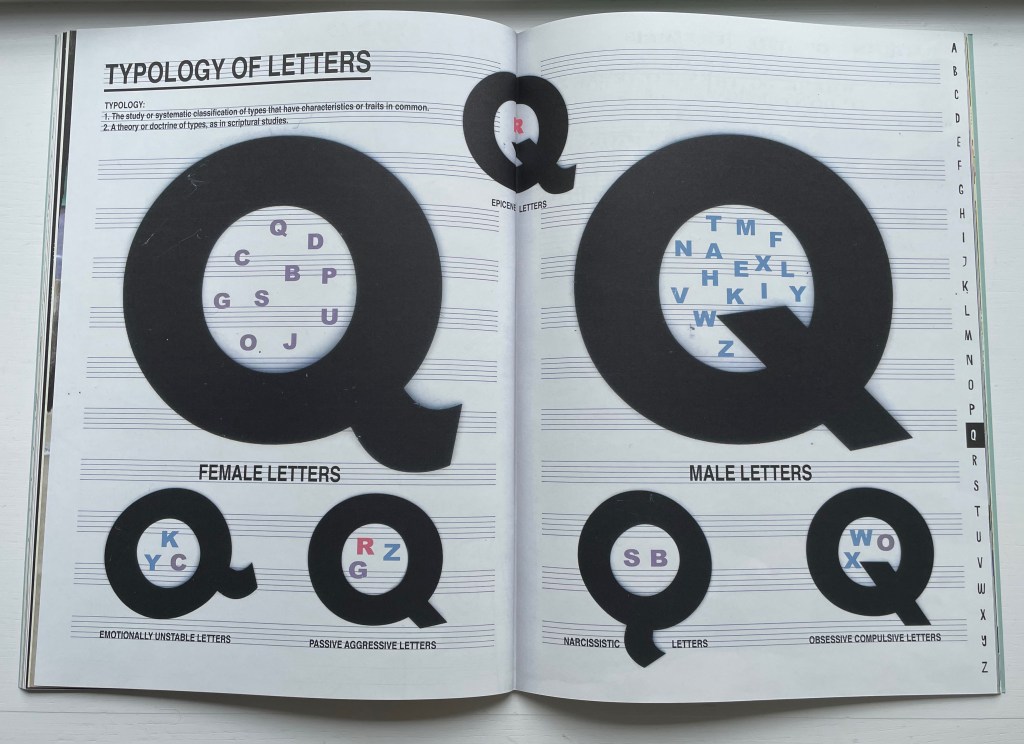

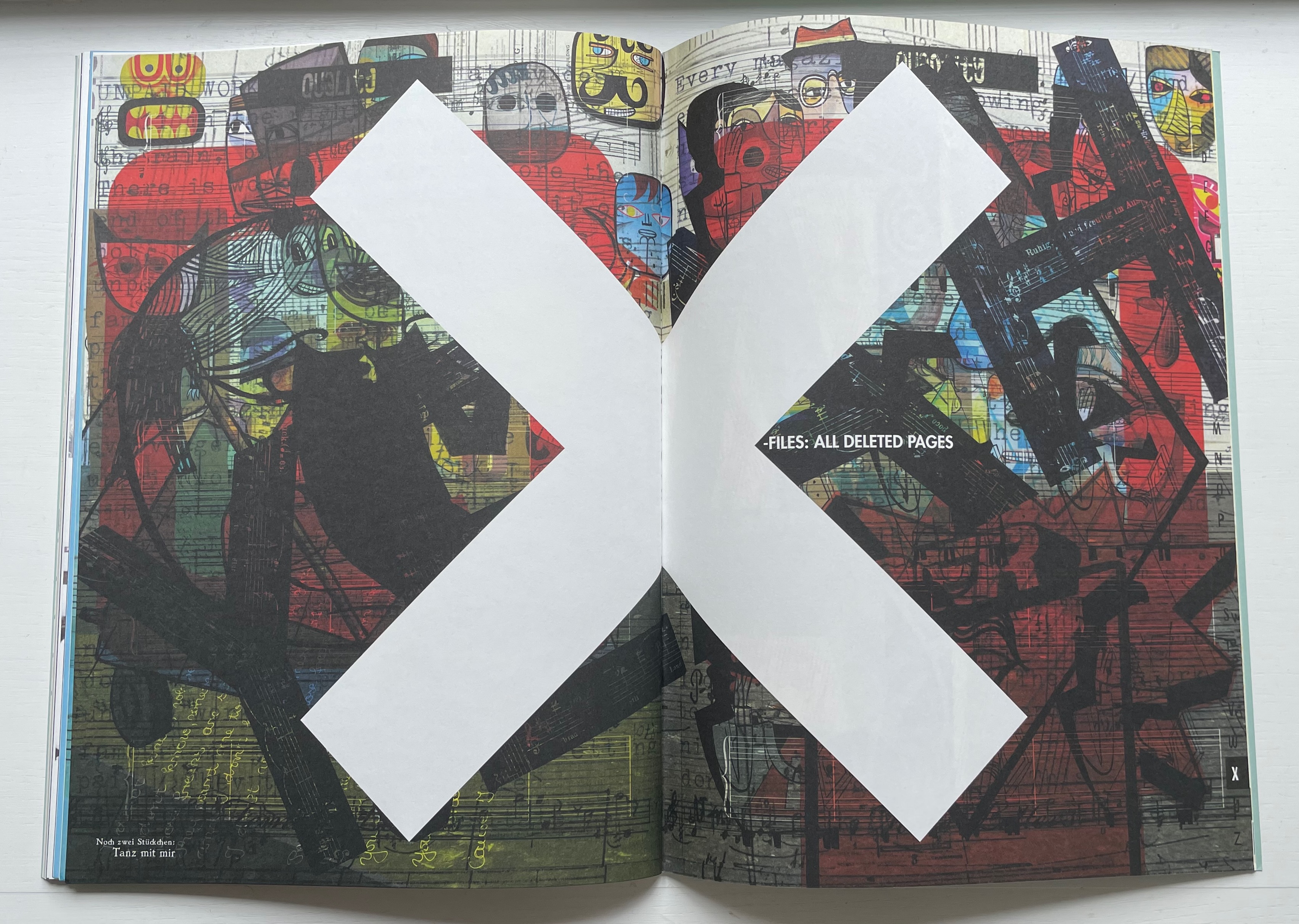

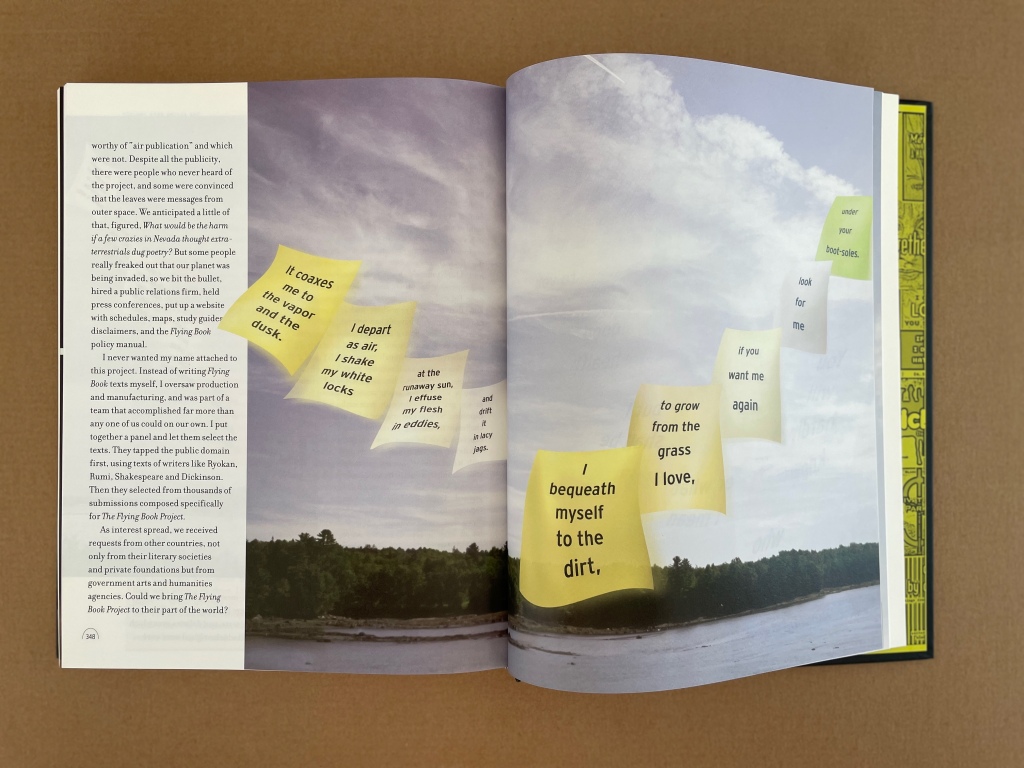

Of course, since the “Mobley biographer” is Lehrer’s mask, it’s no surprise that the format of A Life in Books consists of its own mash-ups. It is both catalogue raisonnée, novel and more. As catalogue, it has photos of covers and excerpts ginned up to look like Mobley’s 101 volumes of fiction and non-fiction. The book also has the features and production values of a full-color college textbook. In addition to the matte-gloss paper-over-boards textbook cover, it has a textbook’s double-page spread with margin call-outs and boxed inserts to explain how to read the book. The fine press book makes an appearance in the form of patterned end- and head-bands. While the titular illumination occurs not with decorated letters leading off each chapter or paragraph but with the photos of Mobley’s books, Lehrer the designer and book artist sneaks his typophilia under the covers of Mobley’s books where there are typographic fireworks that would tickle a Stéphane Mallarmé, with whom it all began.

A Life in Books will also remind some readers of David Lodge’s campus novel trilogy and its characters Philip Swallow and Morris Zapp. Mobley’s official mentor in the faculty of his college creative-writing program, Tobias Drummond, would fit right in at Swallow’s University of Rummidge with this career advice to Mobley:

And whatever you do, make sure your next few books can fit on a shelf, you know, one spine per book — this weird format stuff is not helping you. Once you get your tenure you can make books with wings for all I care, or make nothing at all. Look at me! I haven’t published a book in twenty-three years, though I’ve been tinkering with a collection of poems — modern sonnets.” (P. 83)

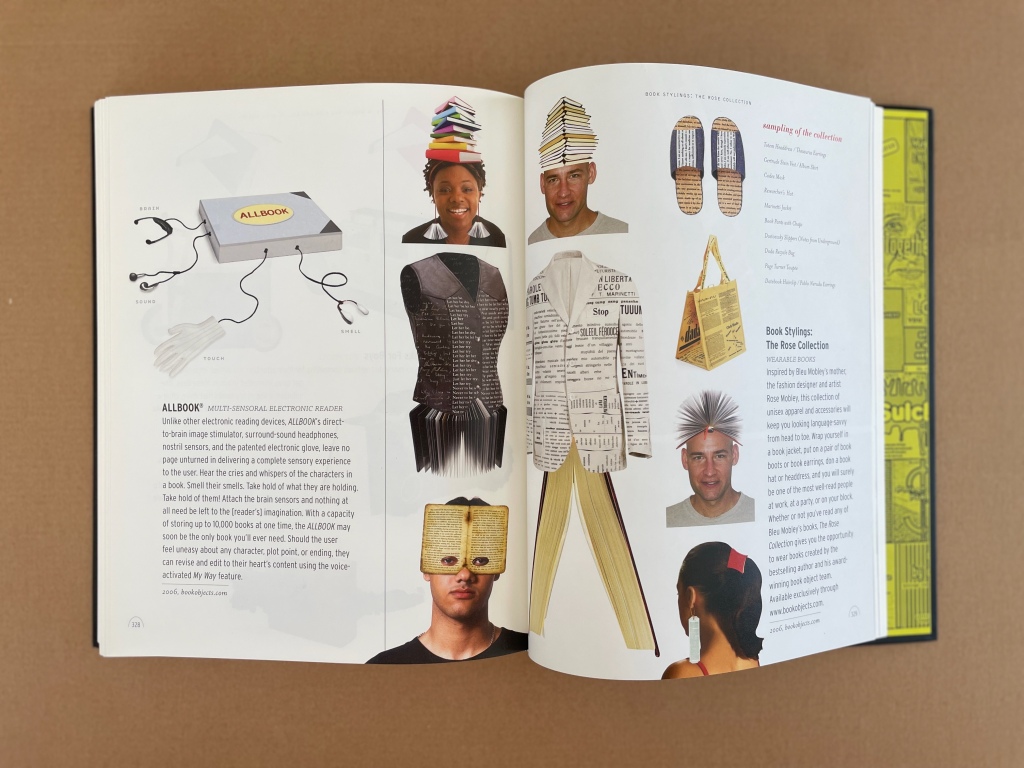

Eventually Mobley and his studio do make books with wings and wearable books as well as many other bookish objets d’art. Perhaps it is the book-art-ishness and the four-color “illuminations” of A Life in Books that has kept it from being issued in paperback and becoming the bestseller it deserves to be. So it goes, as another manic author wrote.

The Flying Books Project

Bookish objets d’art

Jericho’s Daughter (2024)

Eleven years later, it seems that Warren Lehrer has not only taken the advice of Tobias Drummond, Bleu Mobley’s mentor in A Life in Books, he’s also taken two of Mobley’s works and published them as his own: Walls: Stories of Enclosure (Graphic Language Press, 2005) and Riveted in the Word (Kinesthesia Books, 1995). Jericho’s Daughter (2024) is taken from Walls has the dos-à-dos binding against which Drummond warned Mobley. Riveted in the Word (2024) is a complete lifting of it 1995 predecessor but flutters down from the digital cloud to your choice of electronic device for reading. If it weren’t for the fact that Lehrer is the non-fictional, fictional biographer of the fictional, non-fictional subject of A Life in Books, we might expect to see Warren Lehrer in civil court being sued by the fictional, non-fictional Bleu Mobley. Poor Mobley is still presumably in jail, but so what: that wouldn’t prevent him from being nominated and elected president of the United States, so why not lodge a case against his biographer?

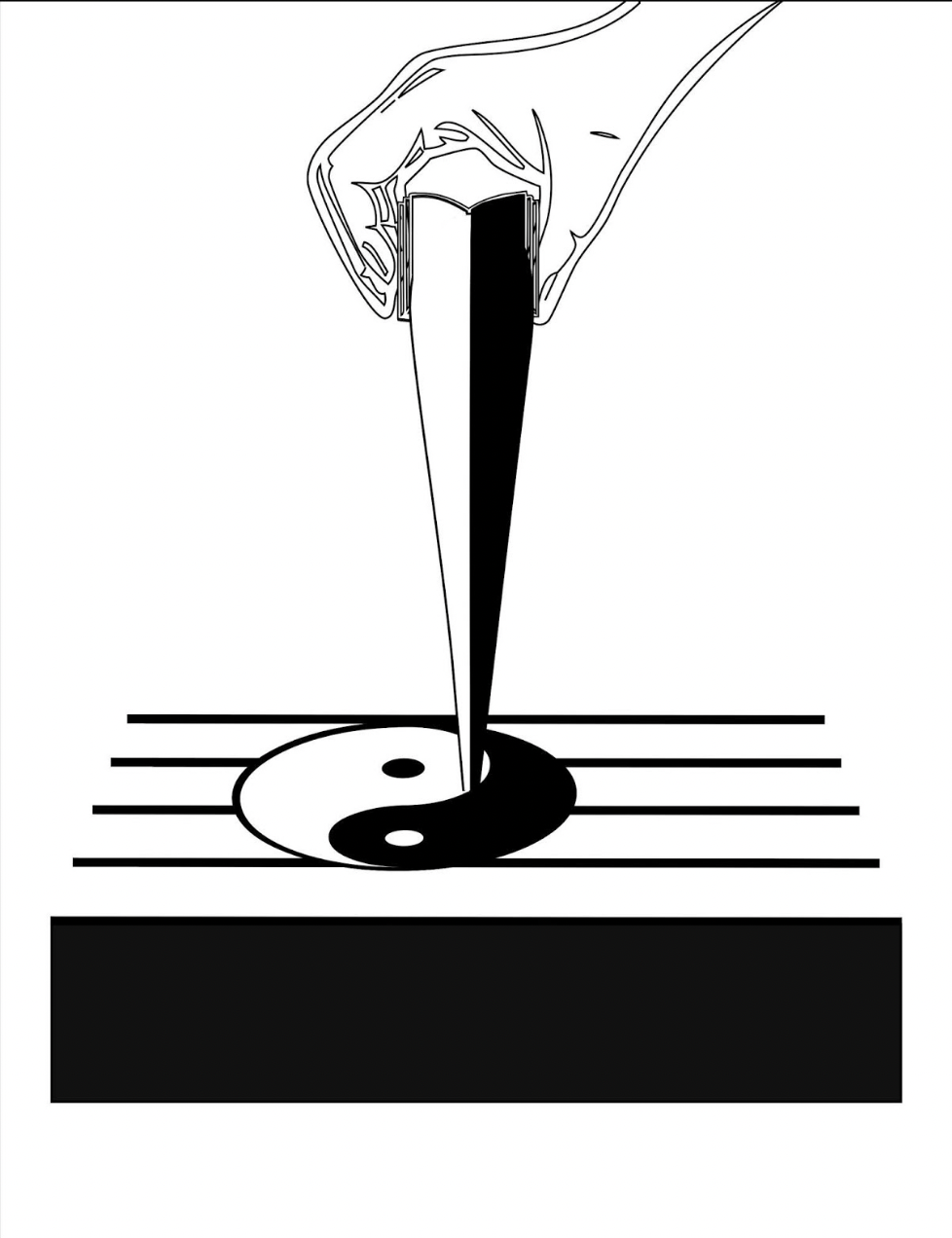

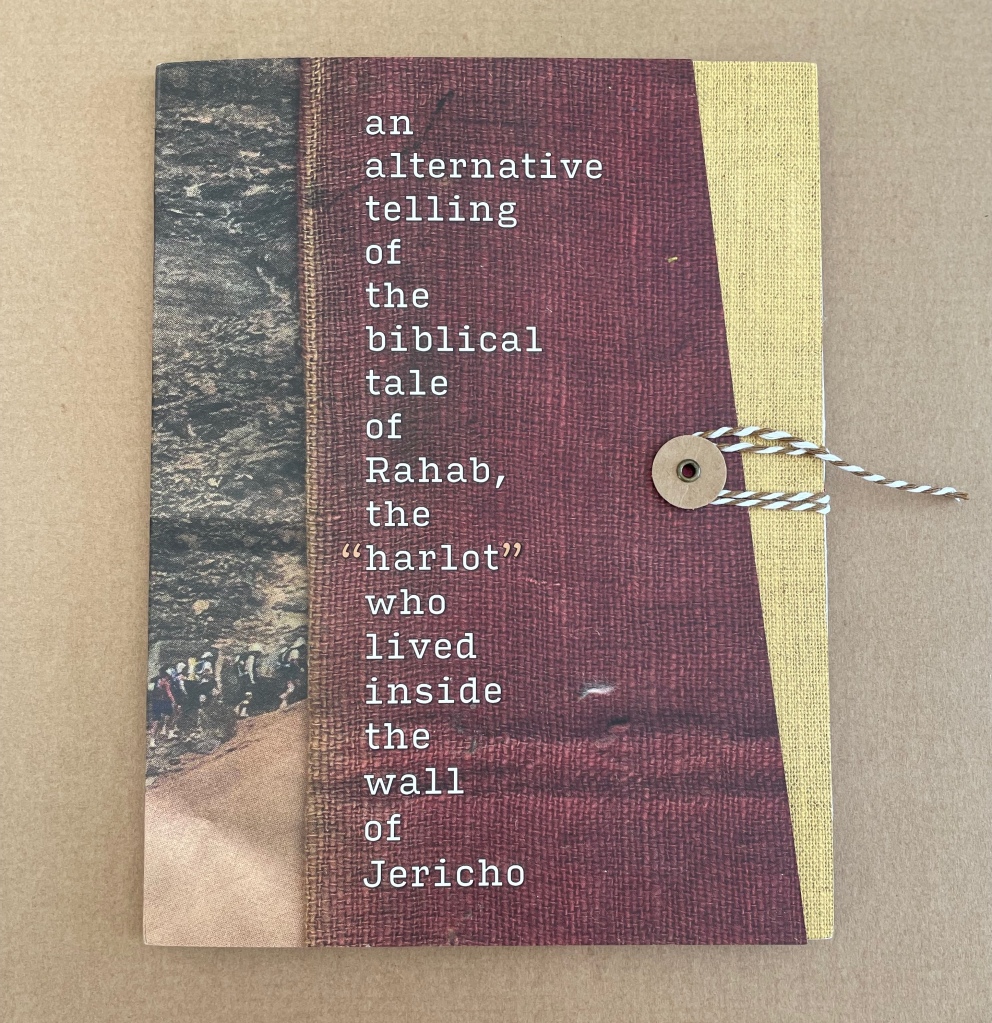

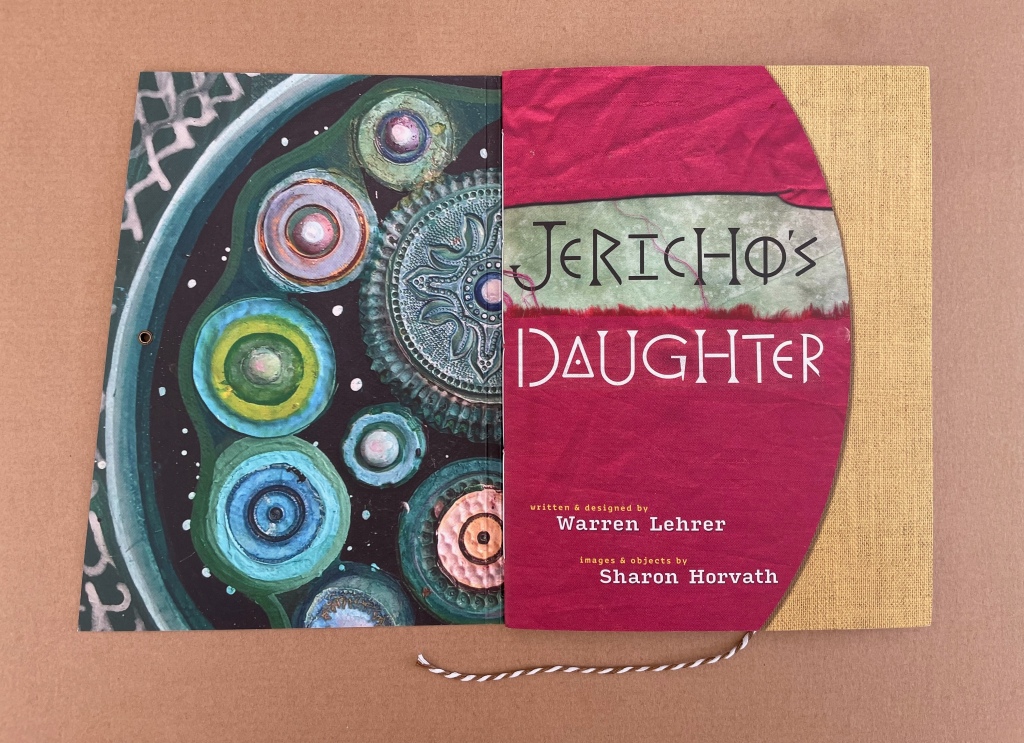

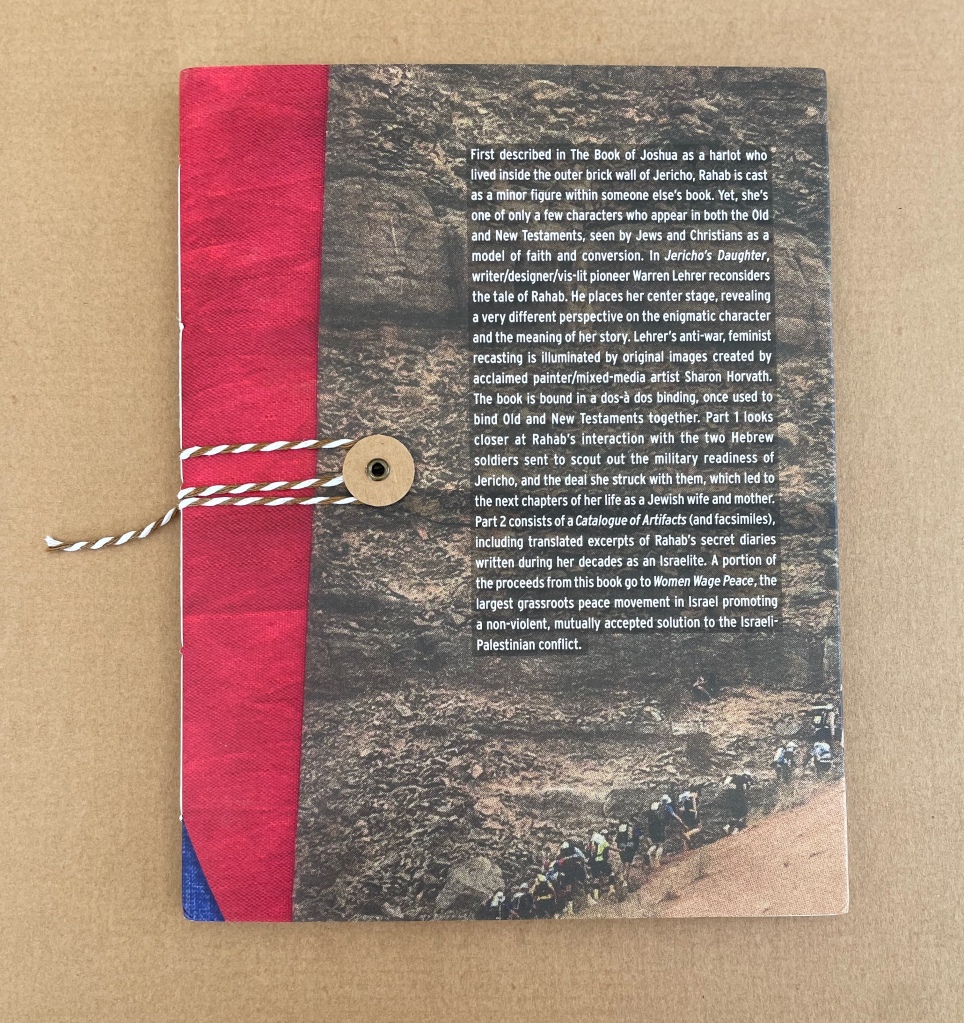

Jericho’s Daughter: An alternative telling of the biblical tale of Rahab, the “harlot” who lived inside the wall of Jericho (2024)

Warren Lehrer & Sharon Horvath

Variant dos-à-dos book sewn to a Z-fold wraparound cover with button & string clasp. H227 x W174 mm. 48 pages. Acquired from Warren Lehrer, 25 April 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Warren Lehrer.

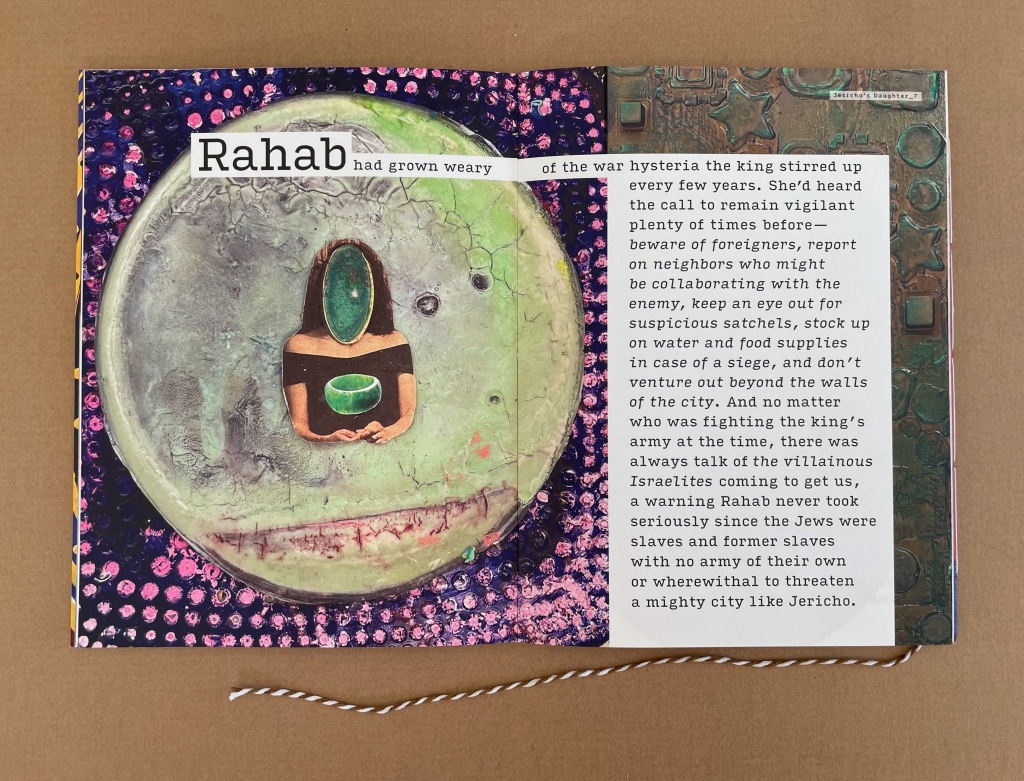

Back to the work of art. With the artist Susan Horvath, Lehrer has transformed the biblical tale of Rahab, the Canaanite prostitute, into a work of art. On one side of the dos-à-dos, Lehrer tells the story of Rahab’s hiding of two Jewish spies in her mud hut outside the walls of Jericho. The other side is a catalogue displaying artifacts (made by Horvath) and facsimiles of Rahab’s secret diaries from her later life as Israelite wife and mother.

Four-color throughout and printed on Mohawk Superfine paper, this first edition displays high production values, though not quite to the level of A Life in Books. It has been handbound by Elizabeth Castaldo. Horvath’s artwork, created in response to Lehrer’s text, consists of photographed collages and assemblages of found objects, drawings, clippings, logos, etc. The faux artifacts have a totemic quality, even when partly composed of rotary telephone dials or margarine ads.

Appearing in the Old and New Testaments and celebrated as a reformed sinner and a symbol of faith in the one omnipotent God, Rahab straddles the divide between Canaanite and Israelite in Lehrer’s retelling. Her reimagined story and her diaries portray her as anti-war and a proto-feminist. The book’s primary type family, Input Serif, and its sizes lend a children’s book air to the pages, which only further emphasizes the power of Rahab’s character and her response to the violence and sexuality of her condition. Lehrer’s and Horvath’s collaboration was completed prior to the events of 7 October 2023 and ongoing war between Israel and Gaza. In light of those events, Rahab’s ancient plea for an end to the cycle of blood and death has become all the more present. The proceeds from Jericho’s Daughter will go to Women Wage Peace, a grassroots peace movement in Israel.

Riveted in the Word (2024)

Riveted in the Word (2024)

Warren Lehrer, Andrew Griffin (soundtrack) & Artemio Morales (programming).

Electronic book. Pre-release edition. Acquired from Warren Lehrer, 25 April 2024.

Photos: Courtesy of Warren Lehrer.

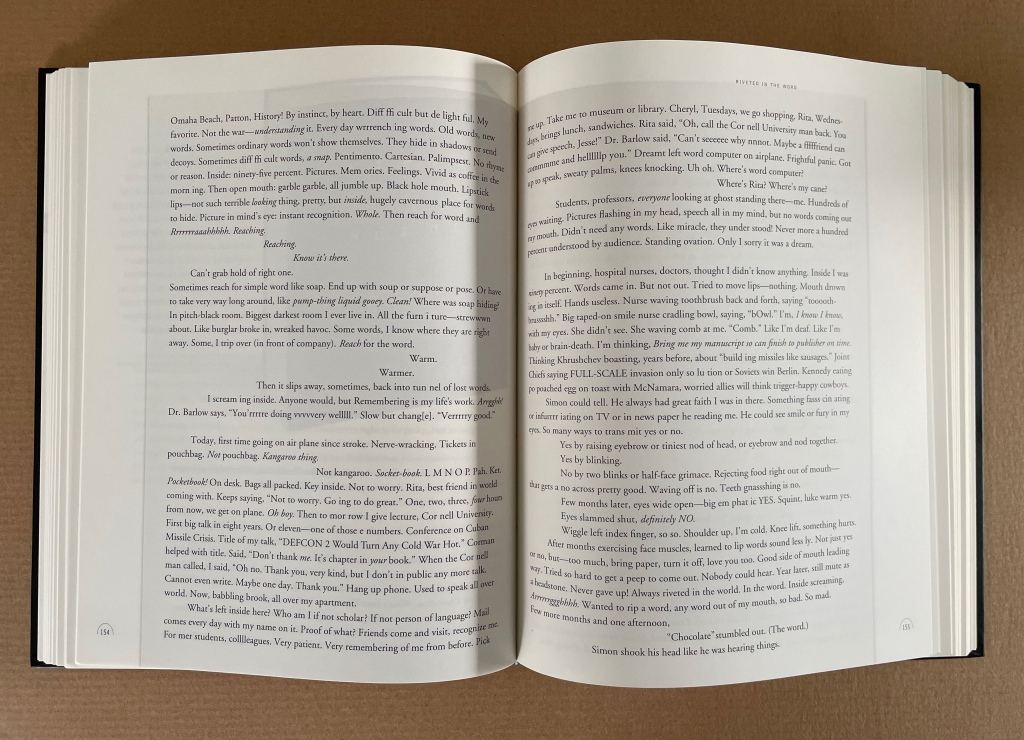

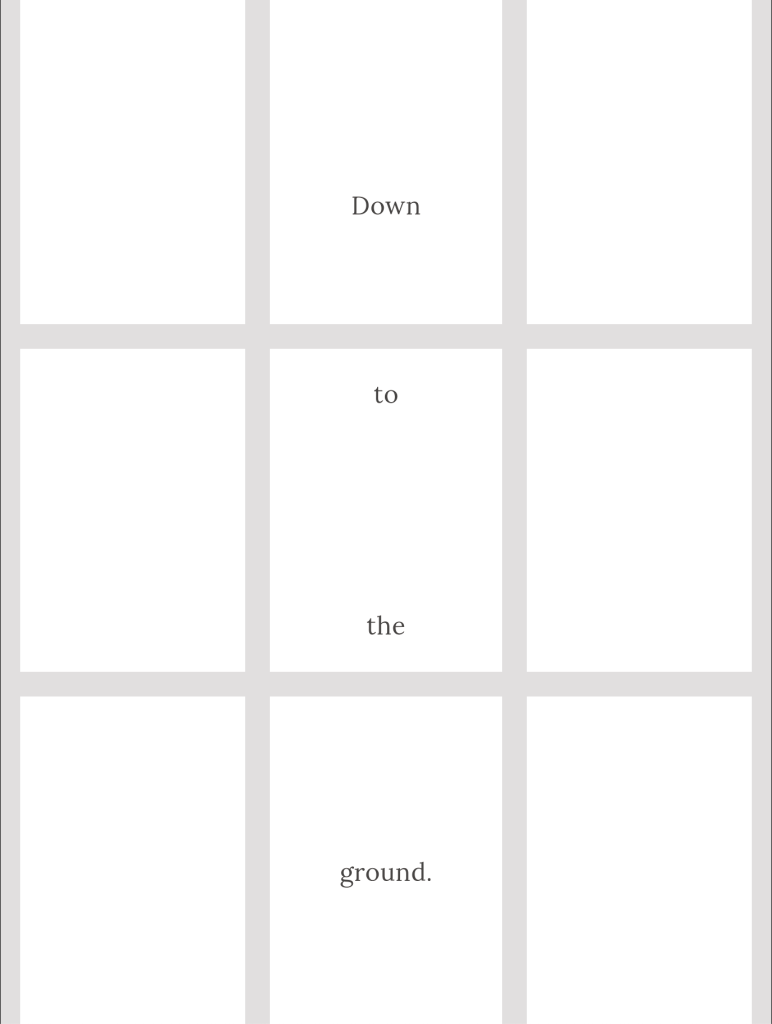

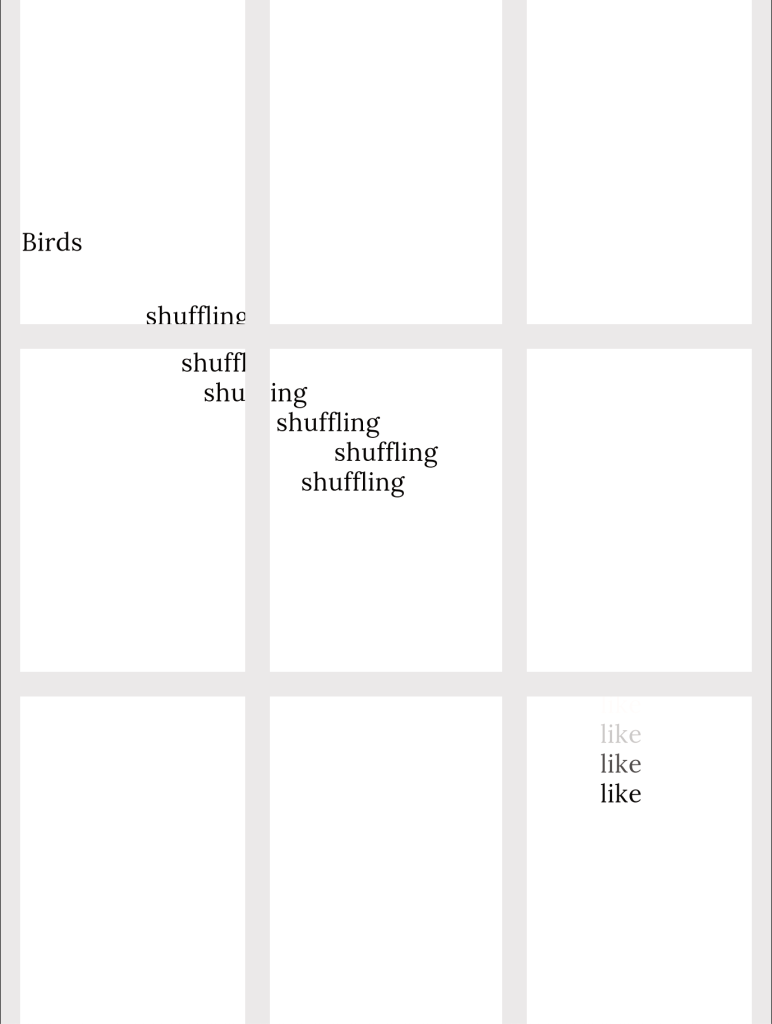

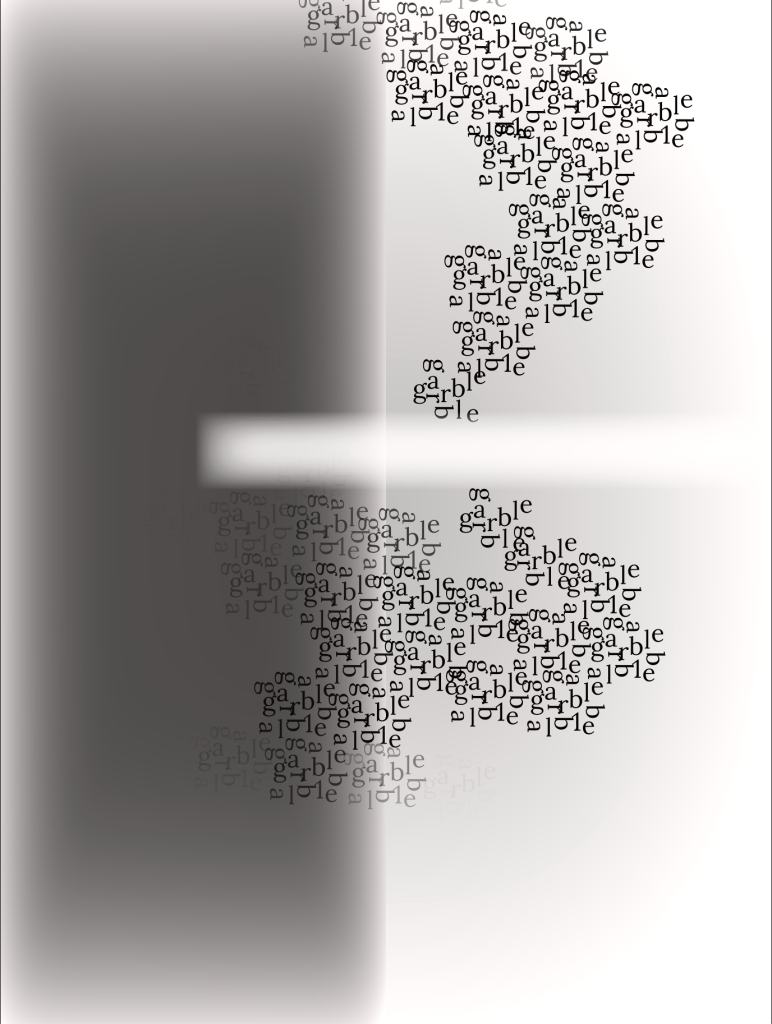

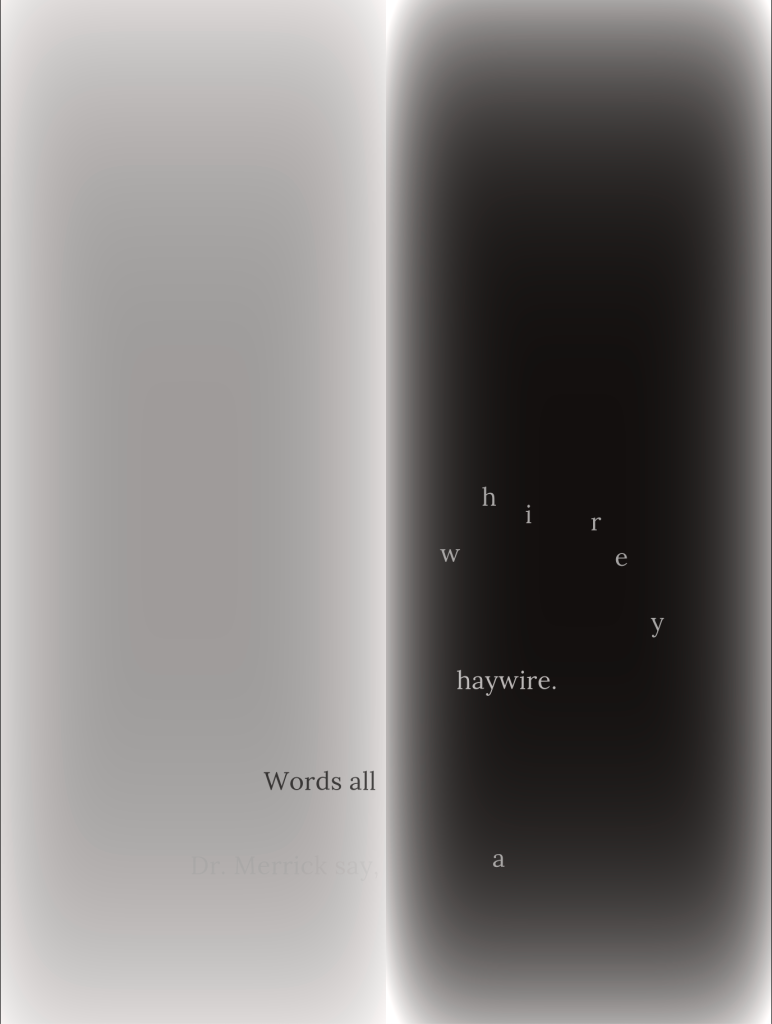

In each of its forms, this short story aims to place the reader inside the mind of Norah Hanson, a retired history professor, as she recalls her fight to overcome Broca’s Aphasia after a stroke, but whichever form, though, the reader is, first and foremost, in that form. When Norah’s first-person narrative expresses her condition on the printed page of A Life in Books, the reader accesses the narrative through the book page’s familiar affordances: fixed text to be read from left to right and down the page, then to be followed across the gutter and up to the top of the next page and down, and then to the top of the turned page. The size and weight of the type, word spelling, punctuation marks, and the placement of all these on the page are also affordances affecting how the reader experiences the narrative. All of those affordances can be manipulated to help share Norah’s experience.

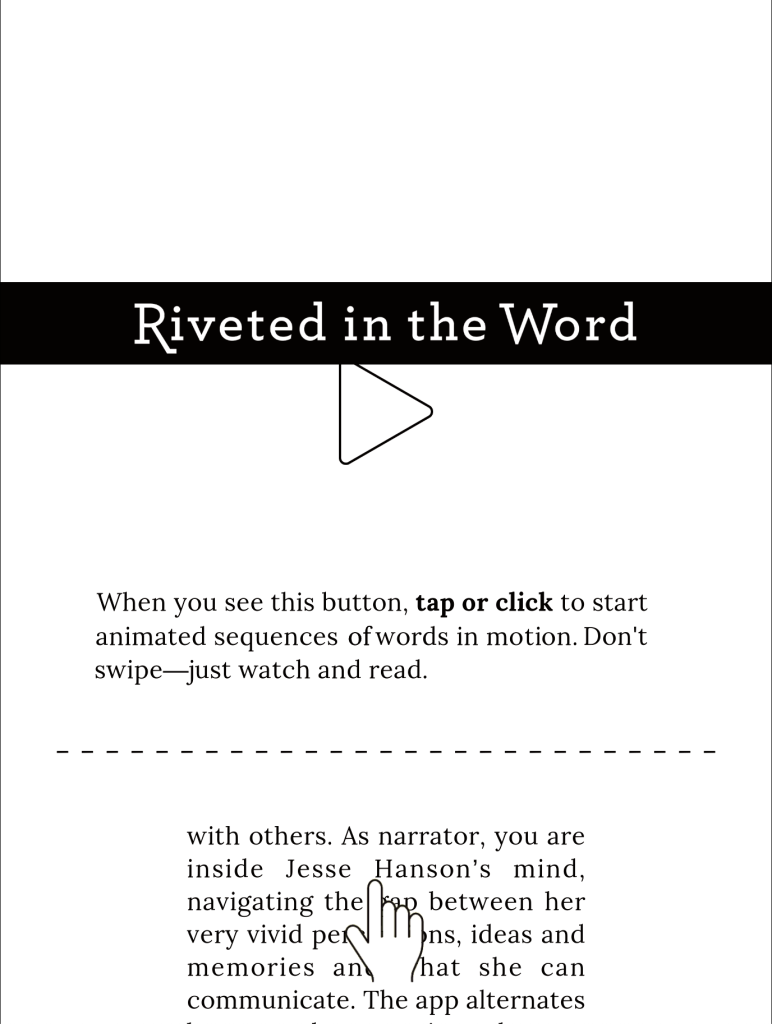

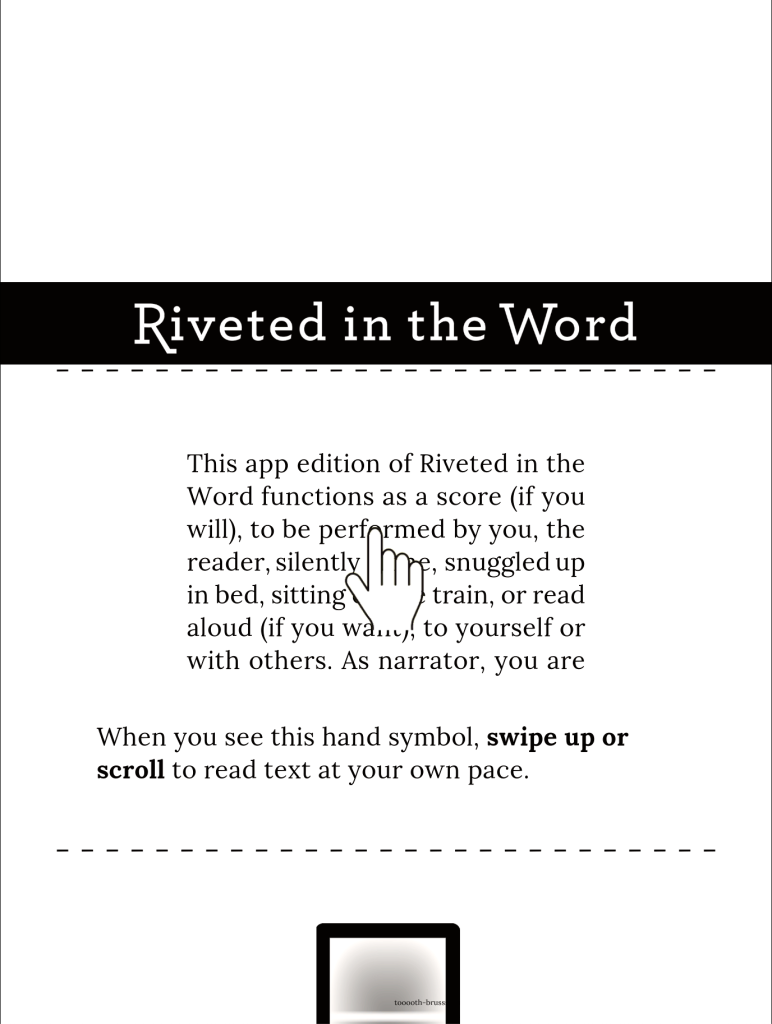

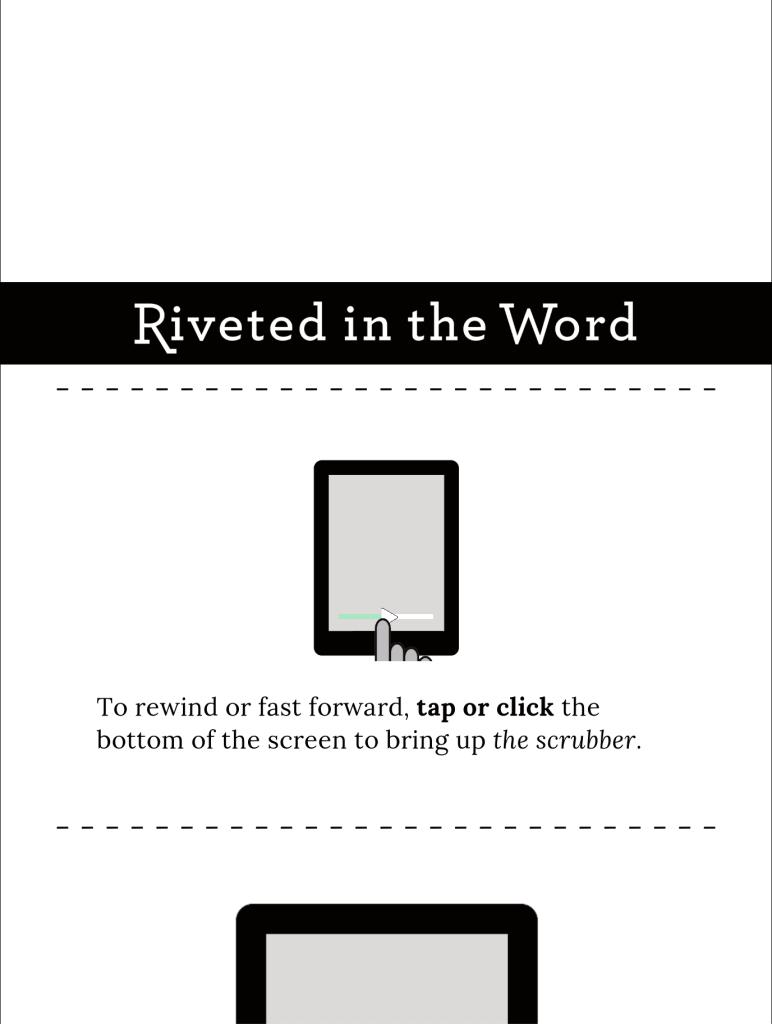

After decades of experience with the electronic screen, readers know the additional navigational affordances of clicking and double-clicking (or finger-tapping), scrolling (or swiping), and pressing and holding keys (or dragging). The reader also knows that different ebook applications deploy these affordances differently, and the programmer obligingly explains at the app’s opening its several states of activity (or operating modalities) and how the navigation works.

After its intro, the Riveted in the Word app delivers text and background music that progress from a screen displaying the glowing green set of numbers of an alarm clock without any navigation direction needed from the reader. Think of this as the televisual state of activity. Further on, vertical and horizontal gray lines enter the screen to form the lattice of a bedroom window through which Norah’s textualized and animated observations appear.

In both the print and ebook forms, the symptoms of omitting key words and repeating a word are similarly presented. By animated scrambling text and the jangling of sound, the ebook’s affordances suggest other aphasic experiences. Which form is more effective or stimulating depends on the individual imagination’s engagement and adeptness with the different affordances, and the individual’s preferences between them.

Neither the print or ebook, however, can replicate the experience of expressive aphasia, and a reader’s engagement and adeptness with either form can only go so far in stepping into the patient’s aphasia. A patient with visual agnosia offers symptoms more susceptible to near-replication by the affordances of an ebook app. One successful metaphor in the Riveted app would be particularly applicable to agnosia. Ironically it springs from the skeuomorphic persistence of the printed form’s double-page spread in the app. The display of the print’s verso and recto pages is a visual metaphor for the left and right hemispheres of Norah’s brain, but that is a static metaphor when it comes to enacting the expressive dysfunction. An ebook’s animation affordance could dynamically enact the symptoms of agnosia gradually erasing from one half of the double-page spread text than runs across it, or showing an object on the verso page and gradually presenting the patient’s distorted drawing of it on the recto.

Whether this is unfairly demanding a different patient and a different ebook, the point is to acknowledge Lehrer’s and Morales’ choices in crafting the ebook version of Riveted in the Word. Other crafters of ebooks have faced similar choices. For Between Page and Screen (2012) , Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse chose its webcam functionality to conjure words from an otherwise wordless print book. For the novella Pry (2014), Samantha Gorman and Danny Cannizaro chose among the functionalities of the touchscreen to enable us to read between the lines literally. For Breathe (2018), Kate Pullinger chose GPS to detect and insert the reader’s location, the time and weather, and when the reader tilts the device or rubs the screen, hidden messages from the story’s (the reader’s?) ghosts appear. It is also worth acknowledging that, by extracting Riveted in the Word from his earlier artist’s book A Life in Books, Lehrer has demonstrated the validity of Amaranth Borsuk’s observation in The Book (2018):

Artists’ books continually remind us of the reader’s role in the book by forcing us to reckon with its materiality and, by extension, our own embodiment. Such experiments present a path forward for digital books, which would do well to consider the affordances of their media and the importance of the reader, rather than treating the e-reader as a Warde-ian crystal goblet for the delivery of content. (p. 147)

Snippets of the ebook version of Riveted in the Word can be seen here, and the whole work can be purchased here. Note that the link to the snippets comes from the Wayback Machine and that the link for the purchase comes from the Apple App Store, which are used here to underscore one last point about print and ebook forms. So far, the former can last for centuries, the latter can last only for as long as the existence of the necessary device, operating system and online source allow. Links from the Wayback Machine are only freeze-frame views of a digital artifact. Permalinks (such as Digital Object Identifiers) may be a step toward preserving digital artifacts, but the limitations of device, OS and online source remain.

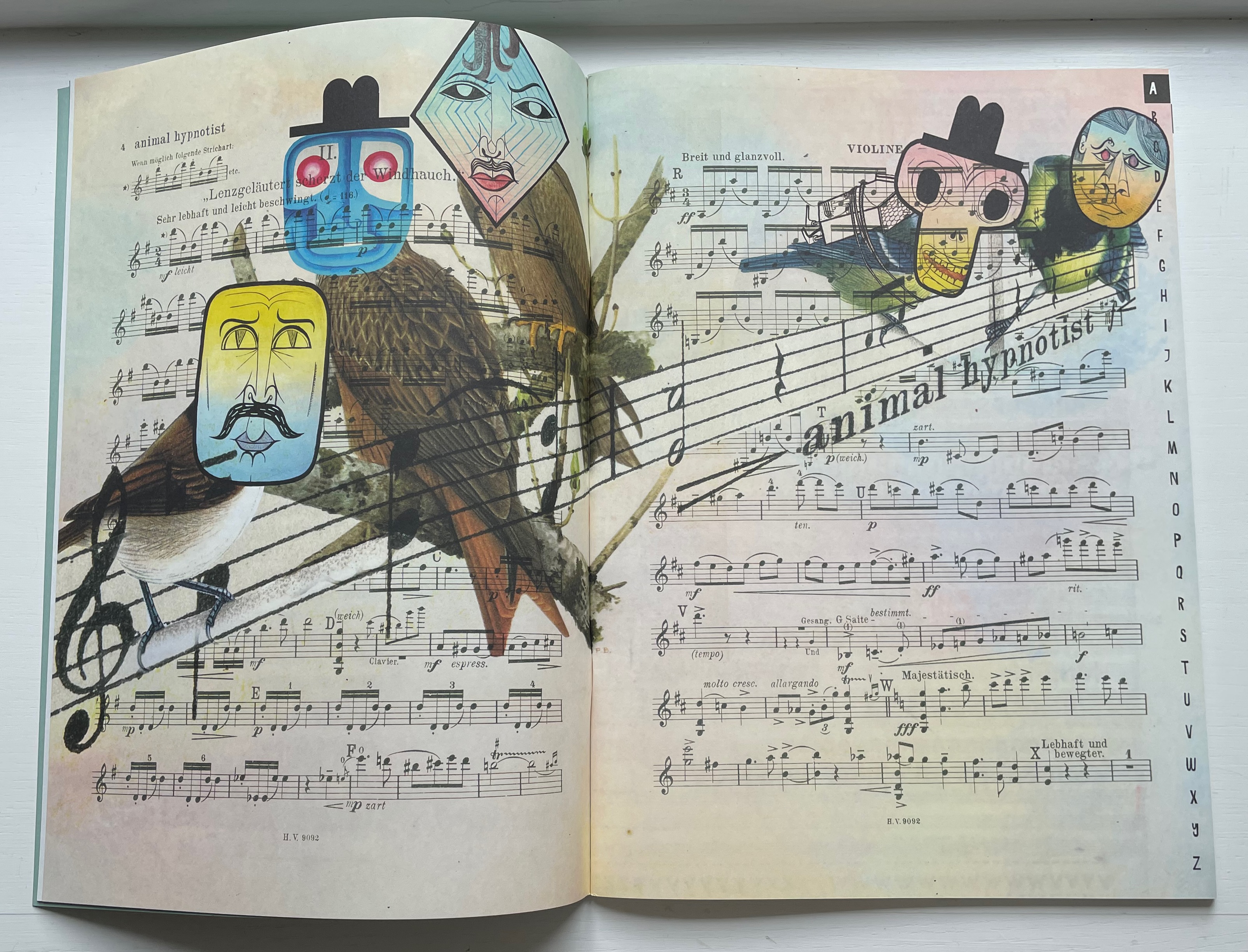

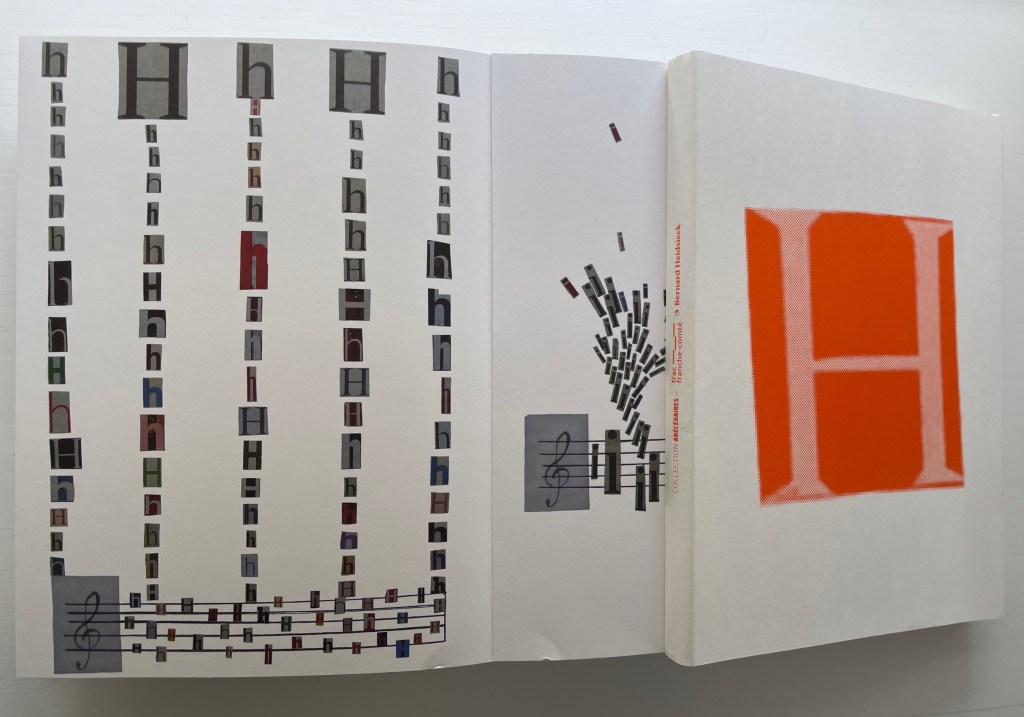

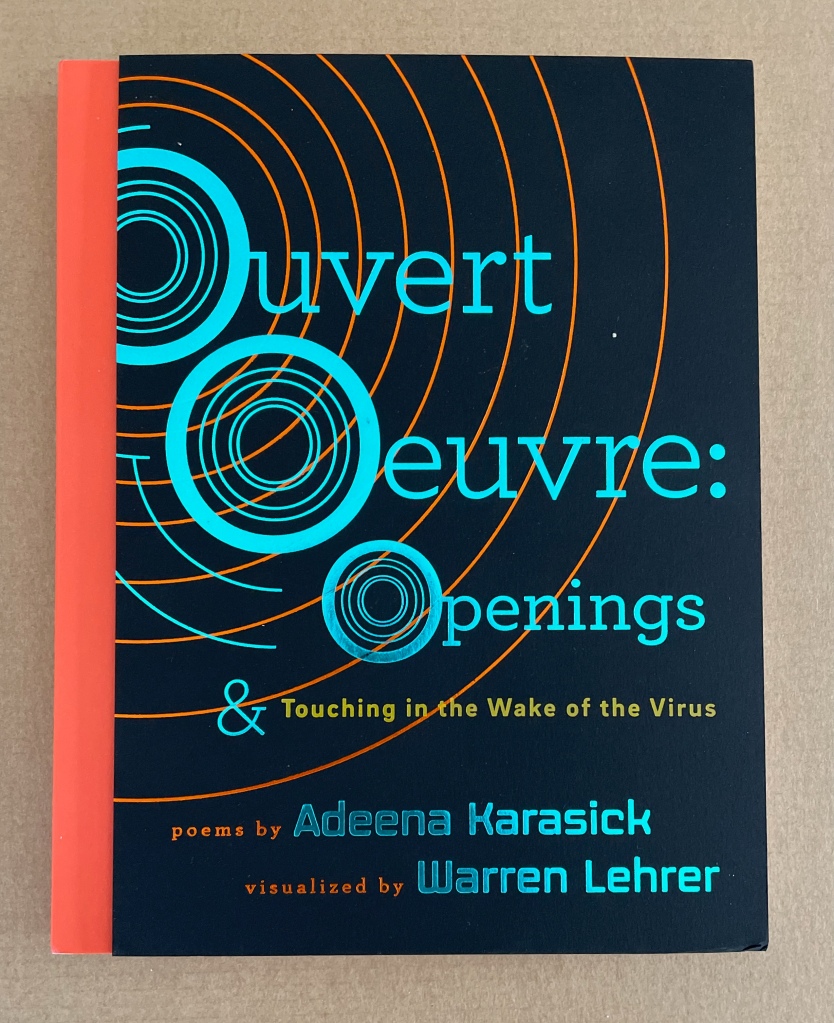

Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings (2023)

Ouvert Oeuvre: Openings (2023)

Adeena Karasick & Warren Lehrer

Three-piece hardcover binding, smythe-sewn, foil-stamped. H204 x W160 mm. 96 pages. Acquired from Warren Lehrer, 25 April 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

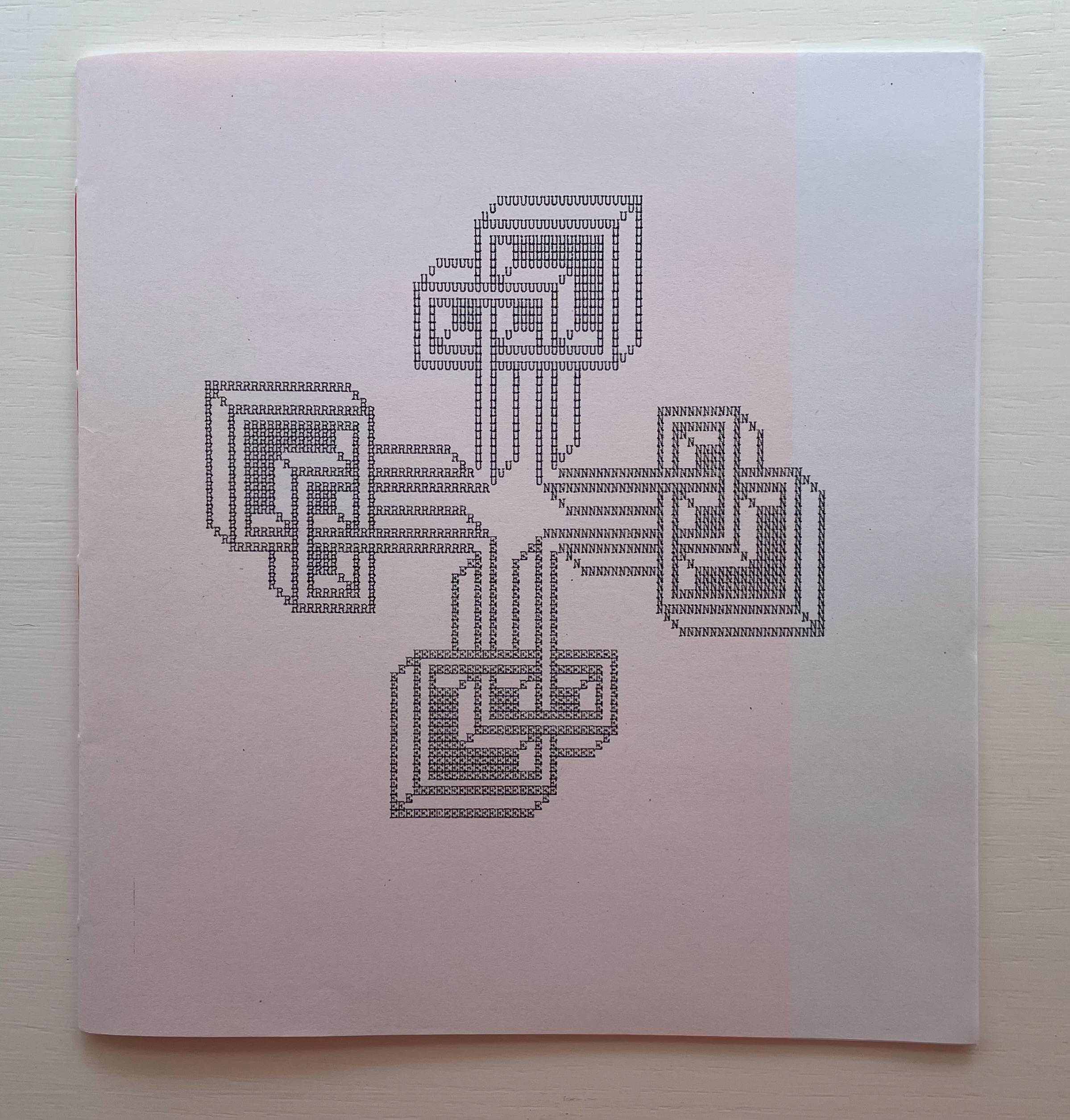

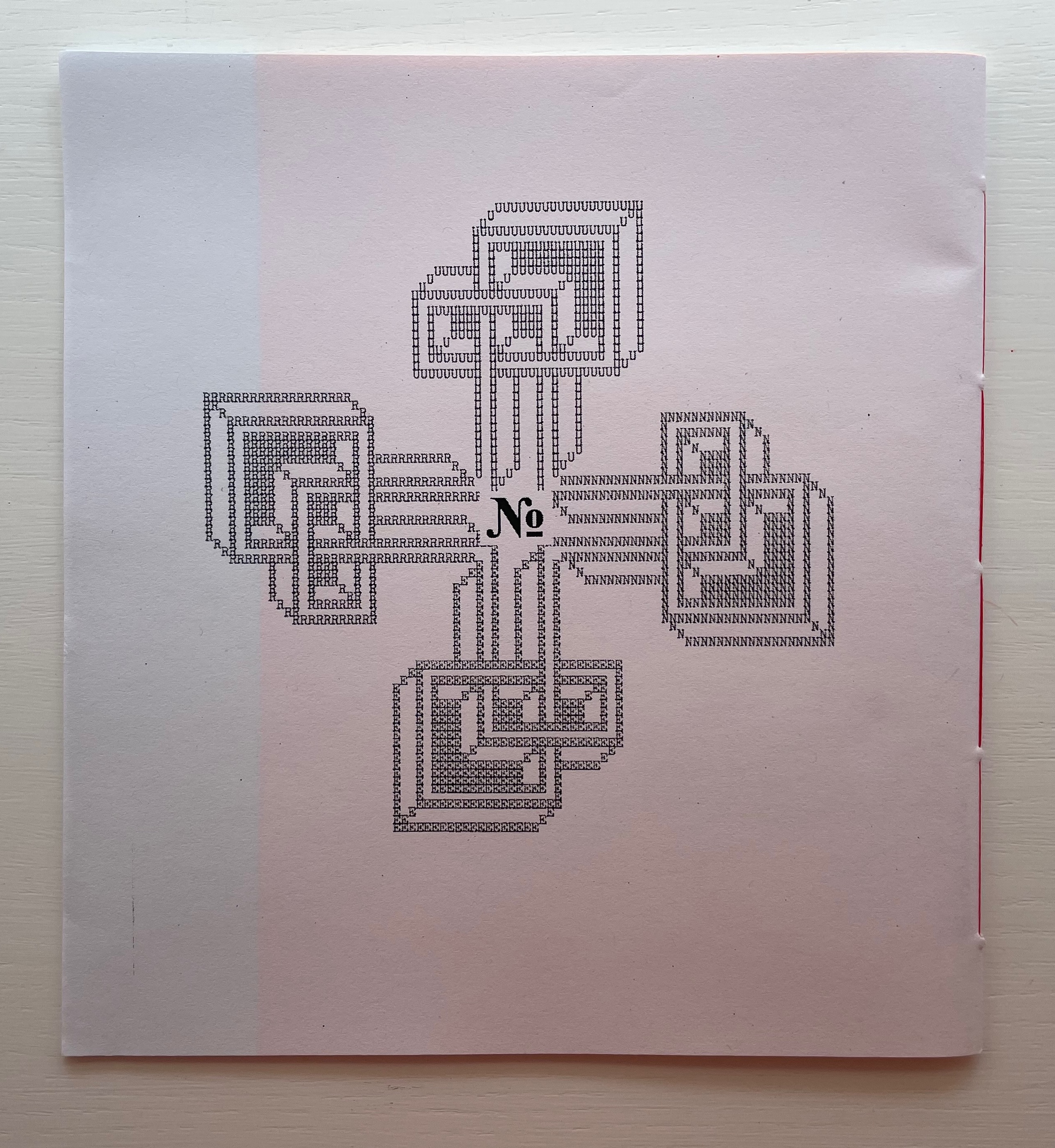

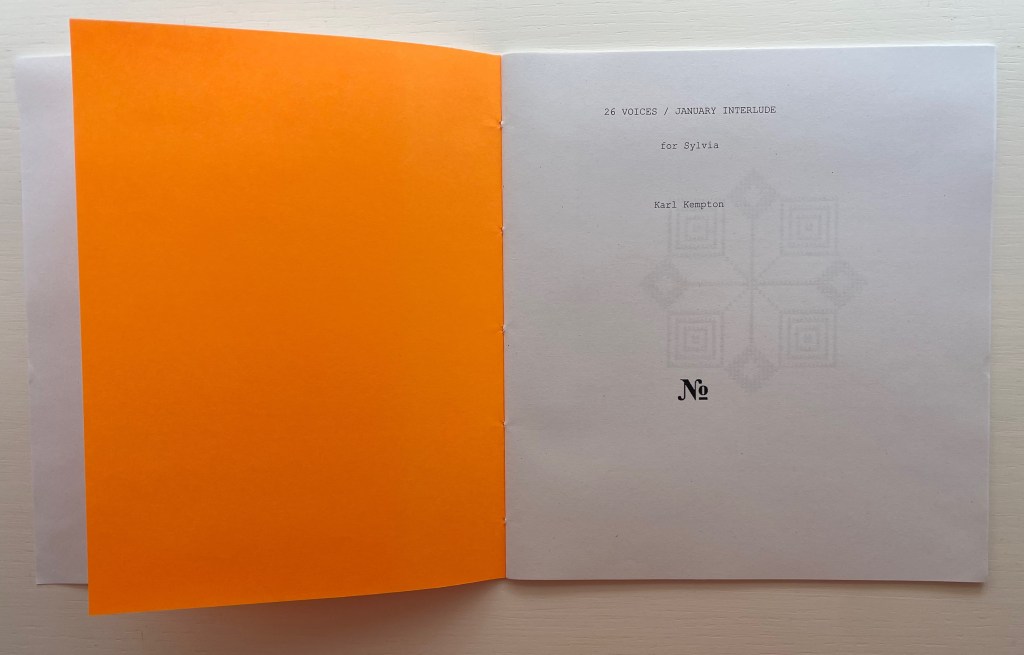

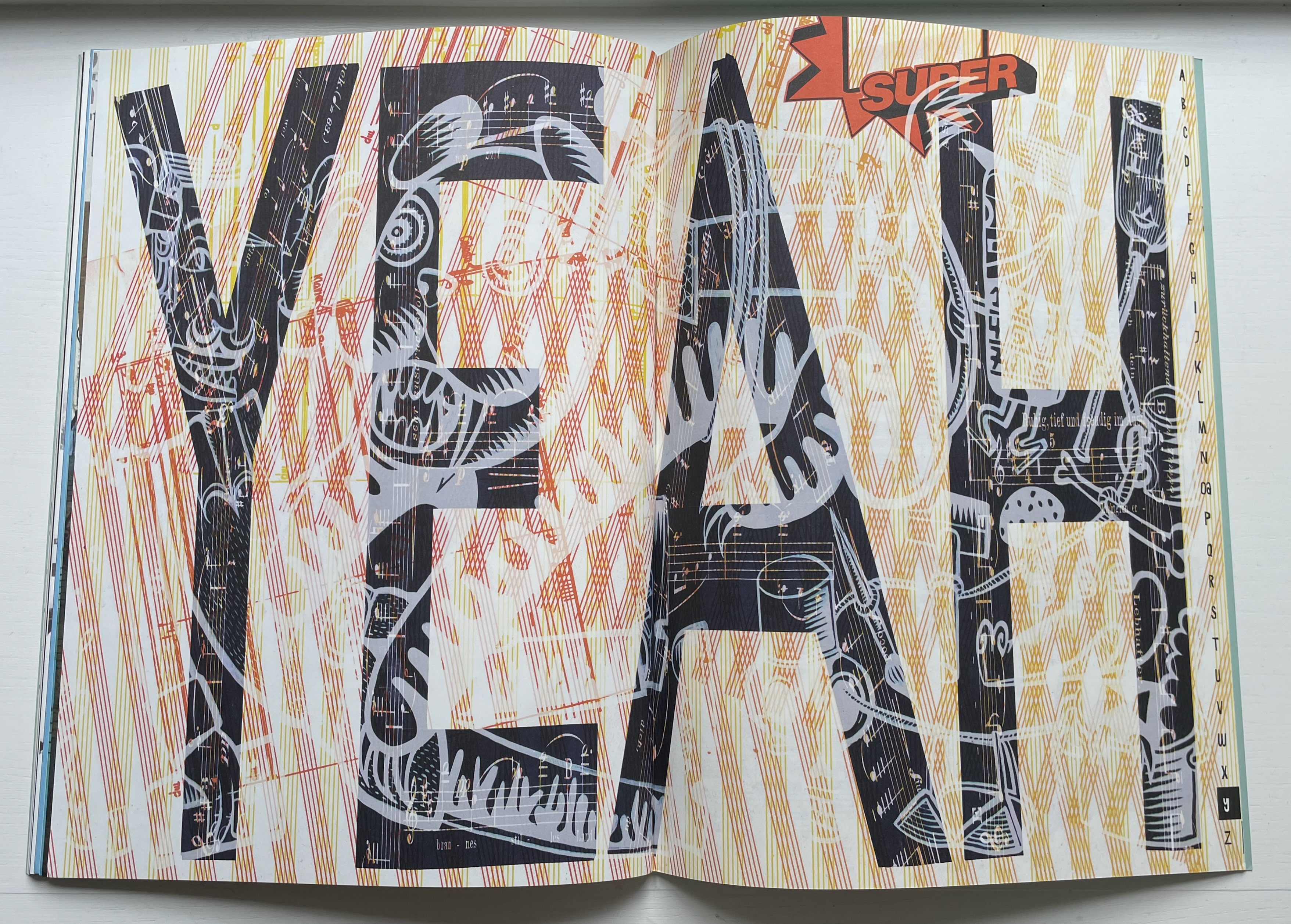

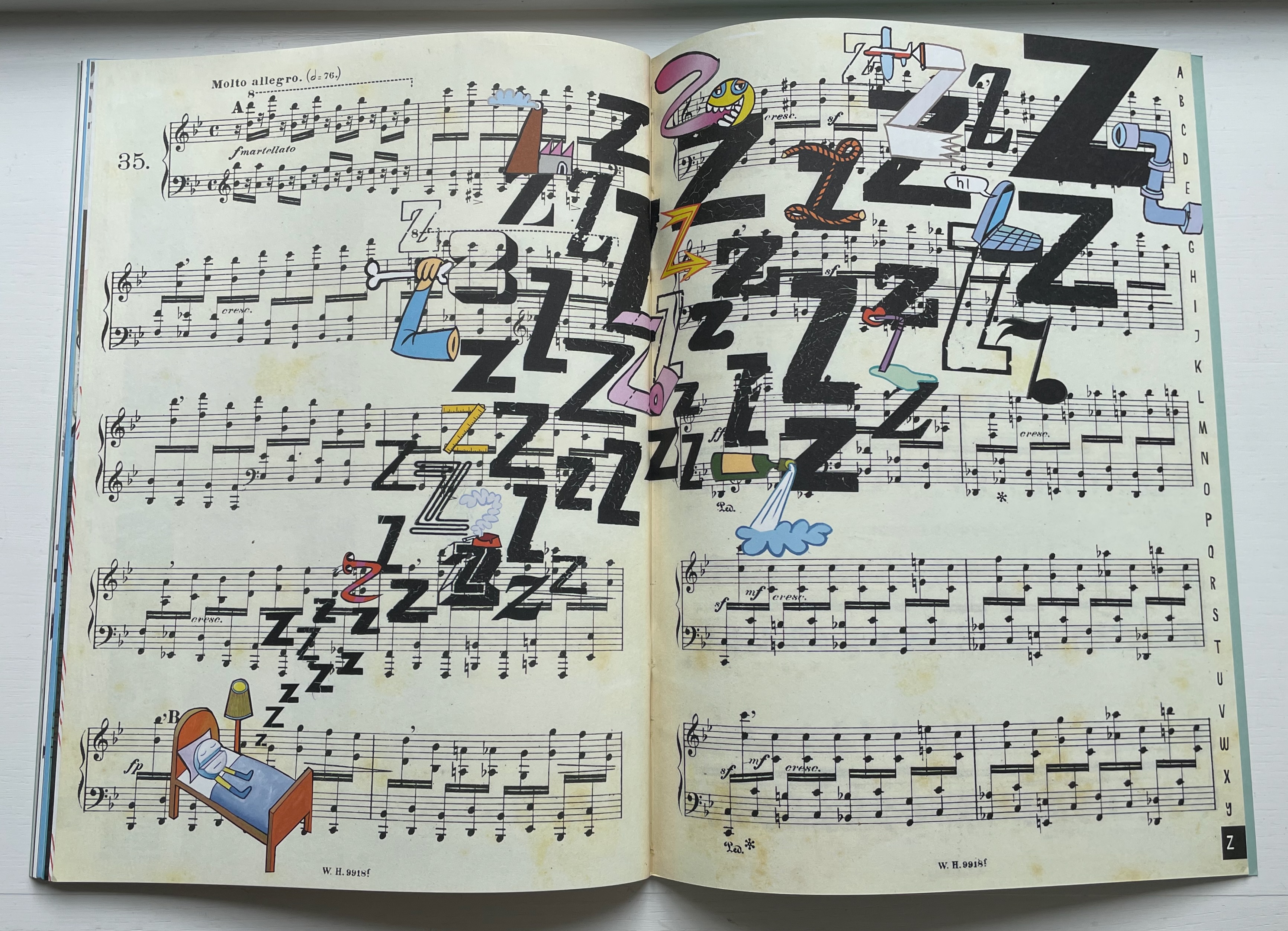

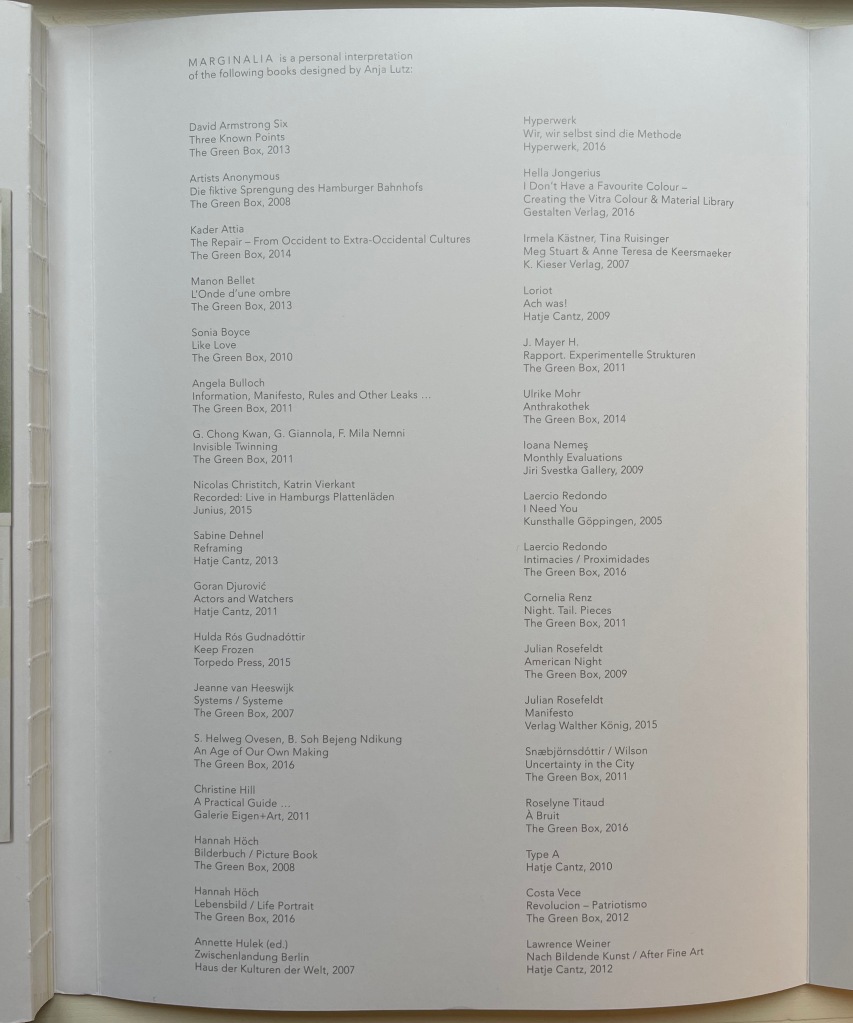

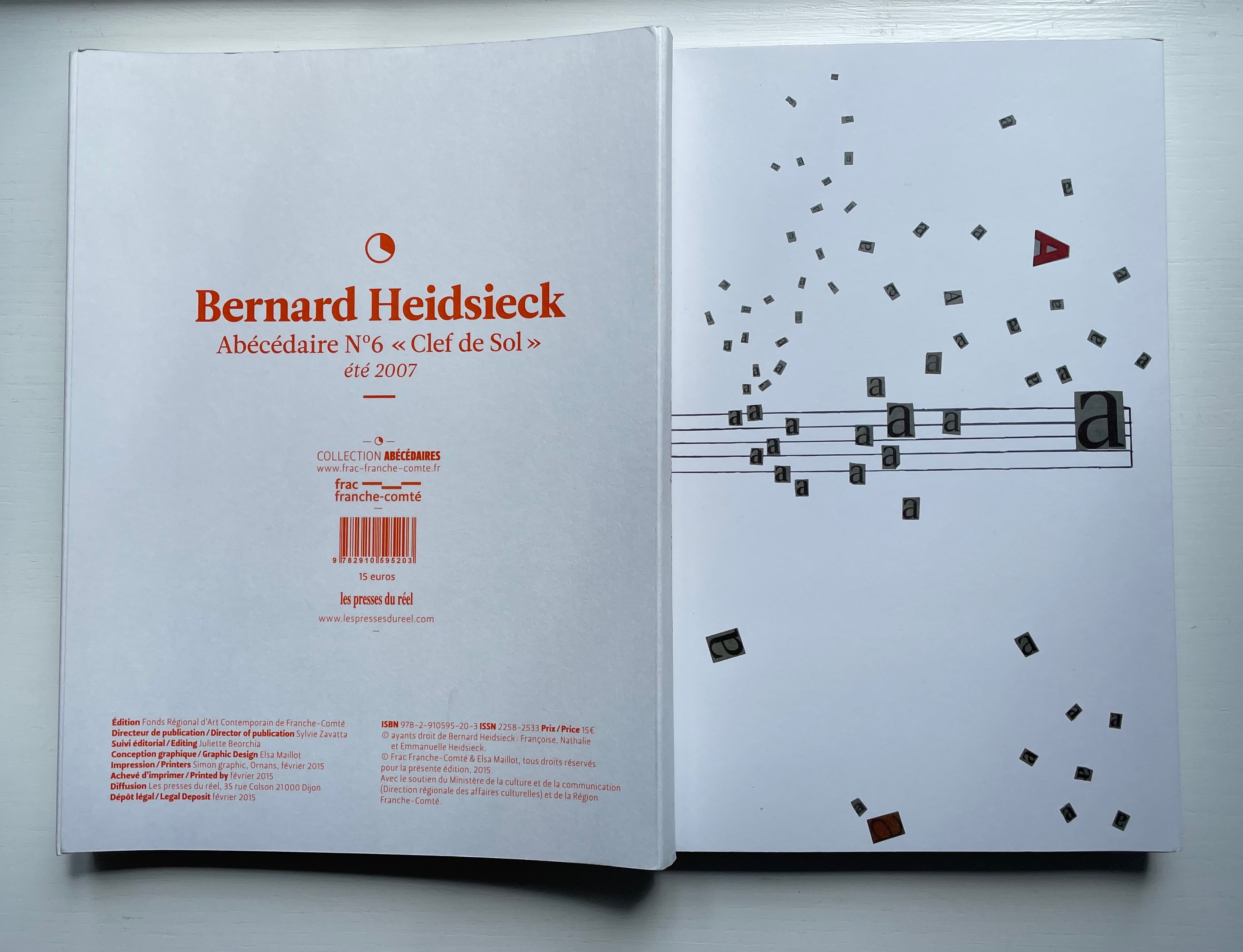

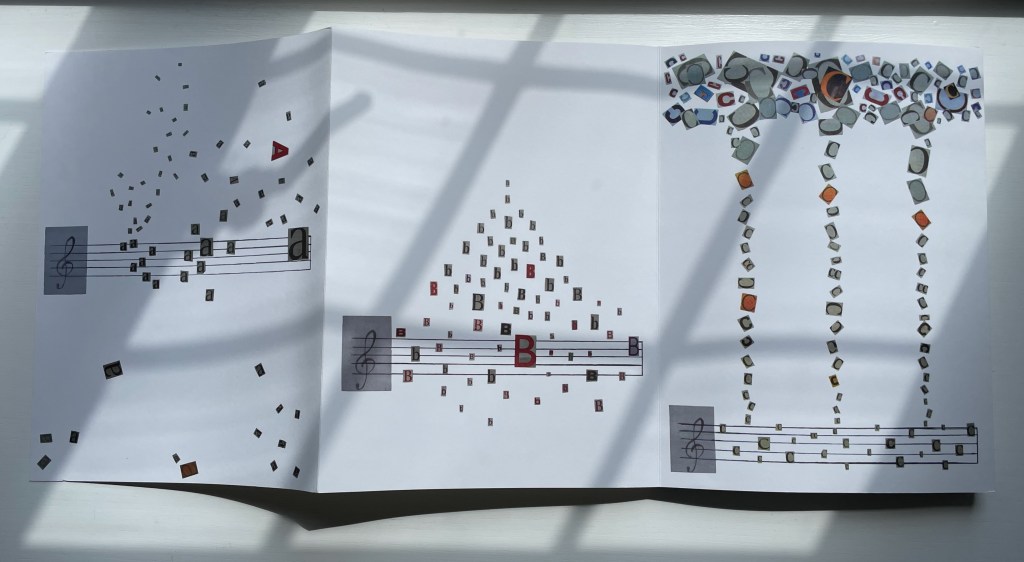

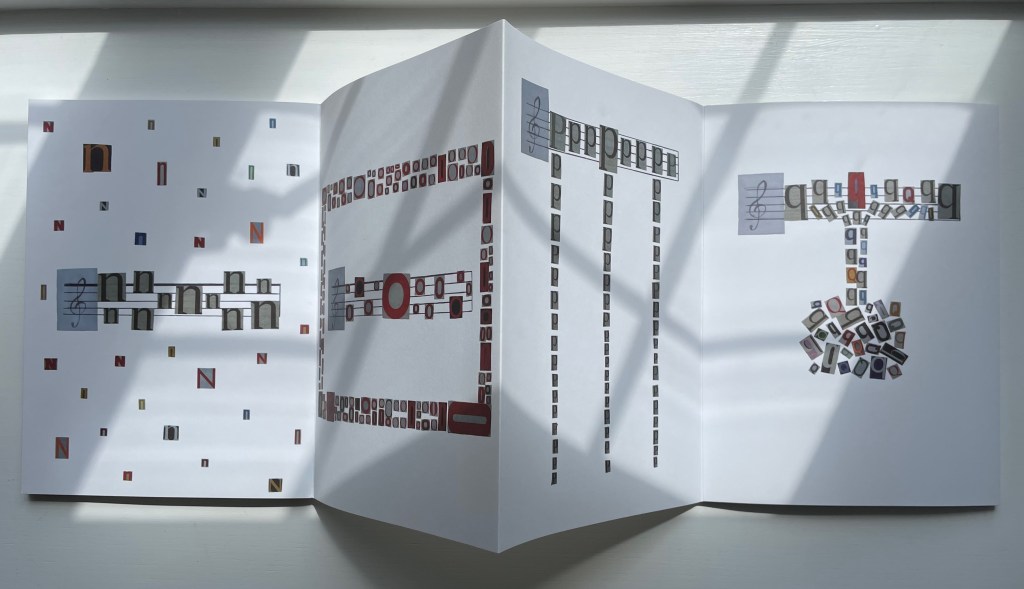

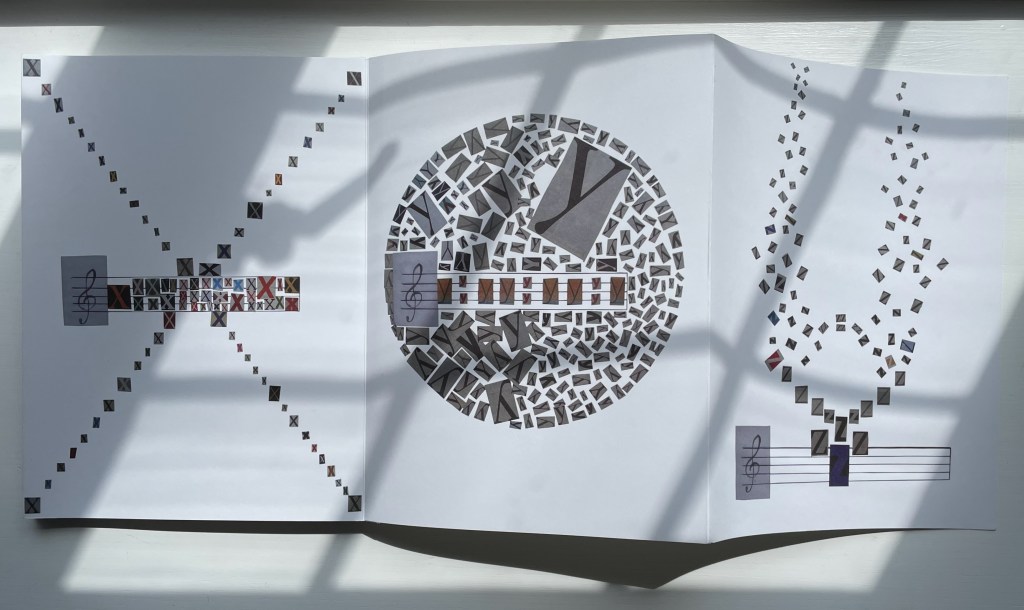

This artists’ book draws on the traditions of concrete poetry and, somewhat, Lettrisme. It is worth close comparison with other works in the Books On Books Collection such as those by Johanna Drucker, Bernard Heidsieck, Karl Kempton, Anja Lutz, and Sam Winston.

Publisher’s description (Lavender Ink):

Inscribing what the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas might call “espace vital” (the space we can survive), the two poems that embody this work form an ecstatically wrought exploration of re-entering the world after a pandemic that never seems to end.

The title poem and Touching in the Wake of the Virus track trepidations and celebrations of openings read through socio-economic, geographic and bodily space. Both poems explore a range of intralingual etymologies laced with post-consumerist and erotic language, theoretical discourse, philosophical and Kabbalistic aphorisms. They foreground language and book-space as organisms of hope—highlighting the concept of opening and touching as an ever-swirling palimpsest of spectral voices, textures, whispers and codes transported through passion, politics and pleasure as we negotiate loss and light.

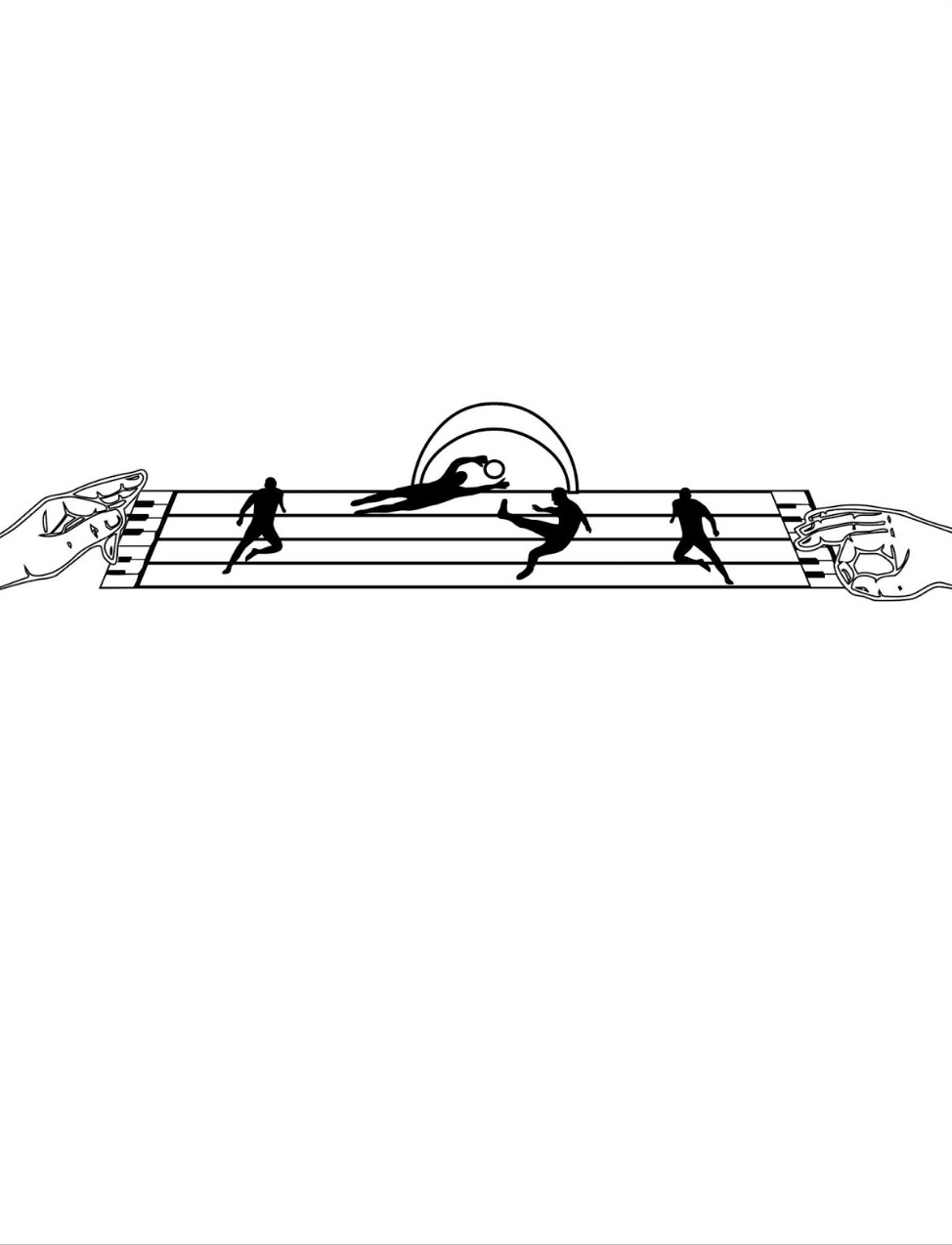

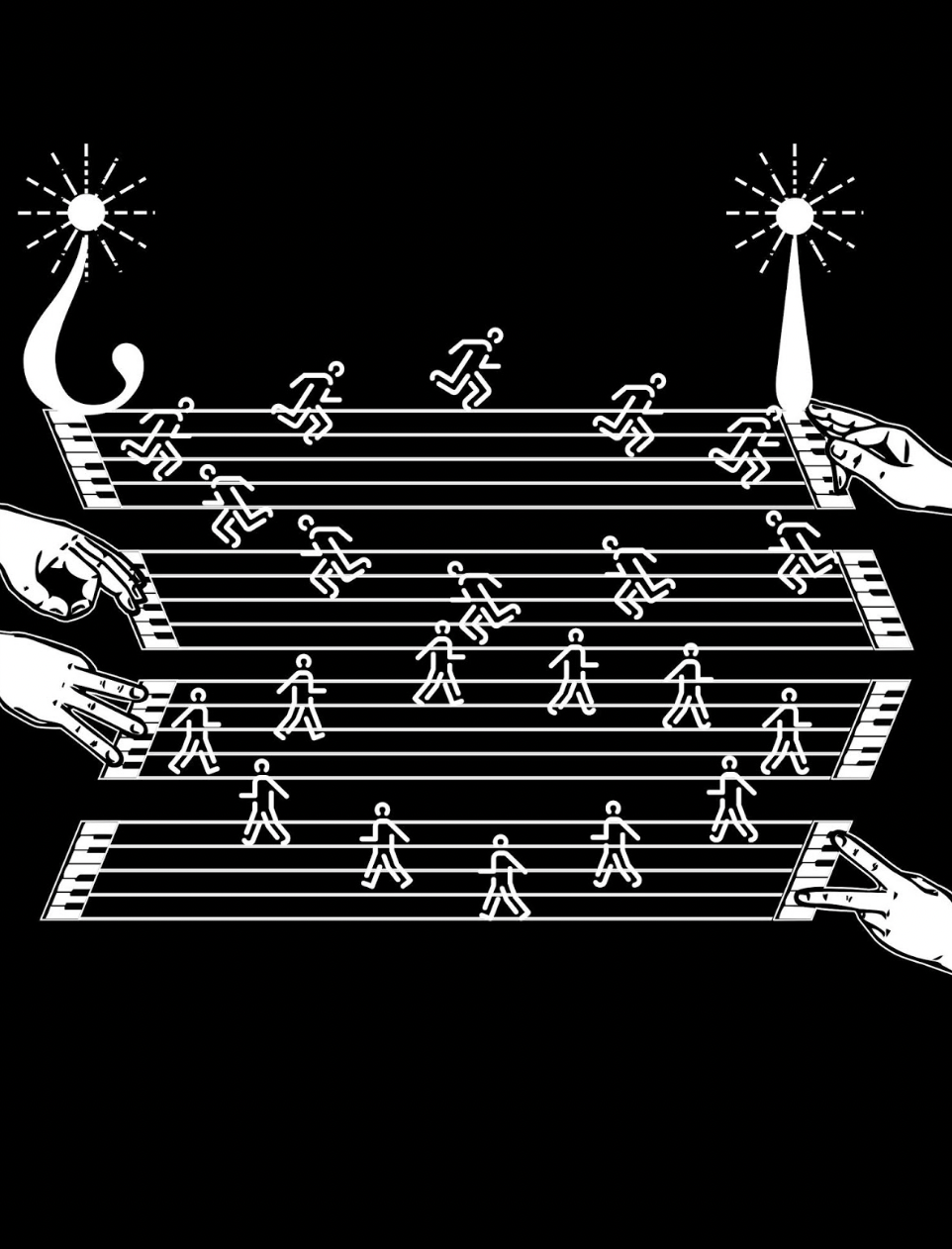

In this first collaborative book, Lehrer choreographs Karasick’s words on the stage of the page through typographic compositions that give form to the emotional, metaphorical, historical and sonic underpinnings of the texts. His sensuous, textural, textual settings diagram themes within the poems like approach/withdrawal, navigating between and through a landscape of barriers and openings, seeking intimacy, fearing/daring to touch and be touched. Together, the writing and visuals engage the reader to become an active participant in the experience/performance of the work.

The book also comes with a soundtrack recording (via QR code to Soundcloud page) of Karasick reading the poems with music composed and performed by Grammy award-winning composer and trumpet player, Sir Frank London.

Further Reading

“Jim Avignon & Anja Lutz“. 29 October 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Amaranth Borsuk“. 19 February 2017. Books On Books Collection.

“Johanna Drucker“. 28 May 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Bernard Heidsieck“. 29 October 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Karl Kempton “. 29 October 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“On The Book (MIT Press, 2018)“. 7 June 2018.

“Sam Winston“. 17 September 2018. Books On Books Collection.

Bean, Victoria, Kenneth Goldsmith and Chris McCabe. 2015. The New Concrete : Visual Poetry in the 21st Century. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing.

Center for Book Arts. 2020. Books, Animation, Performance, Collaboration : Works by Warren Lehrer; 17 January – 28 March, 2020. New York, NY: Center for Book Arts.

Davis, Brian. 15 May 2024. “Warren Lehrer’s Life in Books“. College Book Art Association Publications.

Lehrer, Warren. 2011. A Life in Books website.

Sherman, Levi. 25 May 2024. “Jericho’s Daughter“. artistsbookreviews.com.