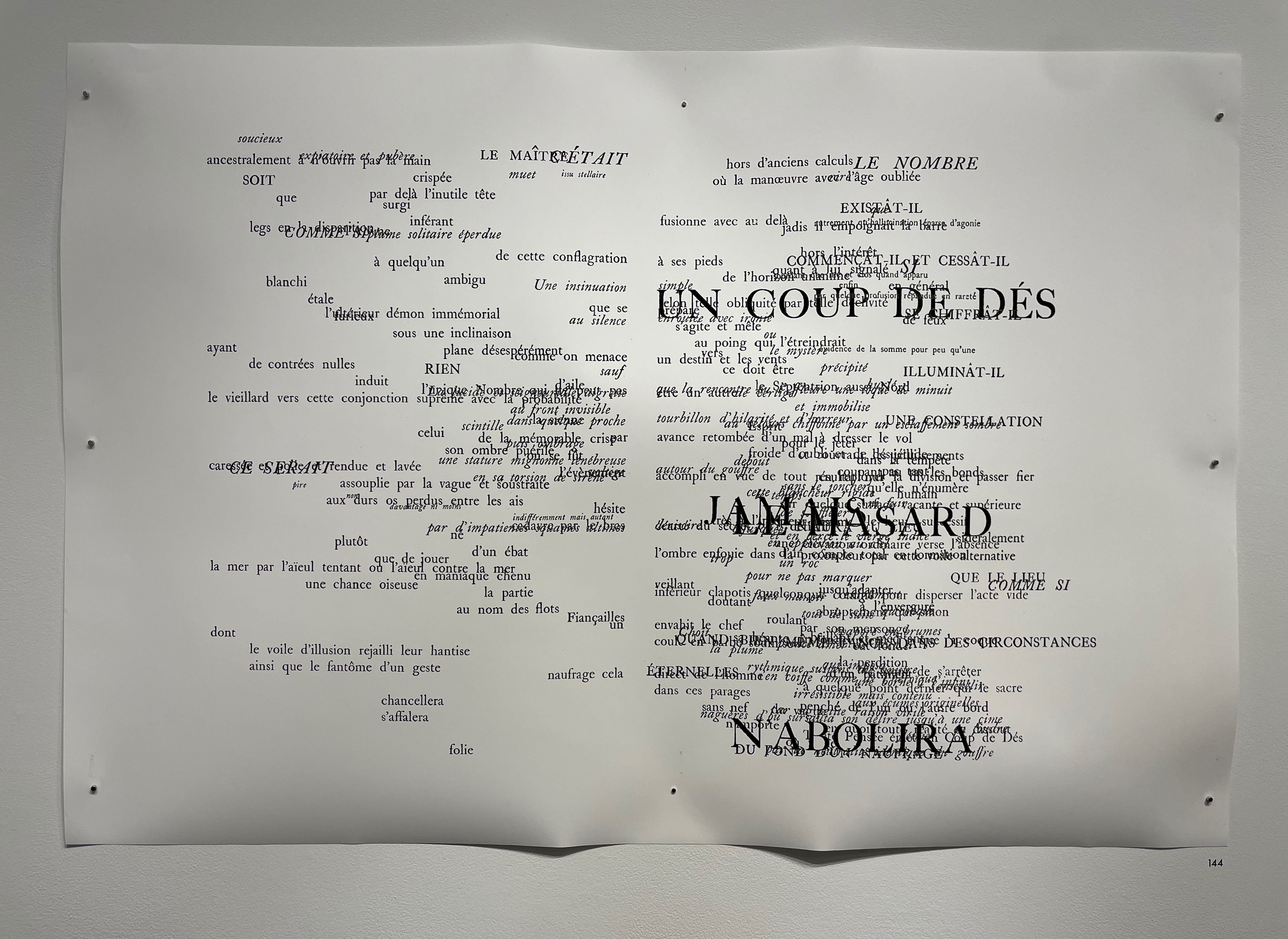

Why should an obscure poem like Stéphane Mallarmé’s groundbreaking Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira le Hasard: Poème (1897) have become the cornerstone of an art-industrial complex of literary, critical and artistic responses ranging from essays, books, edited collections, countless editions, and appropriations in the form of fine press livres d’artiste, book art and sculptures, films and theater, ballets and fado, musical compositions, digital programs and installations, and even pavement art? It was never even produced under Mallarmé’s hand in the form he intended. We have the poet’s manuscripts and proofs. We have his son-in-law’s efforts with the publisher Éditions de la Nouvelle Révue Française (NRF) in 1914 to present Un Coup de Dés in accordance with Mallarmé’s plans. In many ways, their liberty of including the preface from the 1897 Cosmopolis version so unsatisfactory to the poet paved the way for artistic/editorial interventions and art-industrial complex to come.

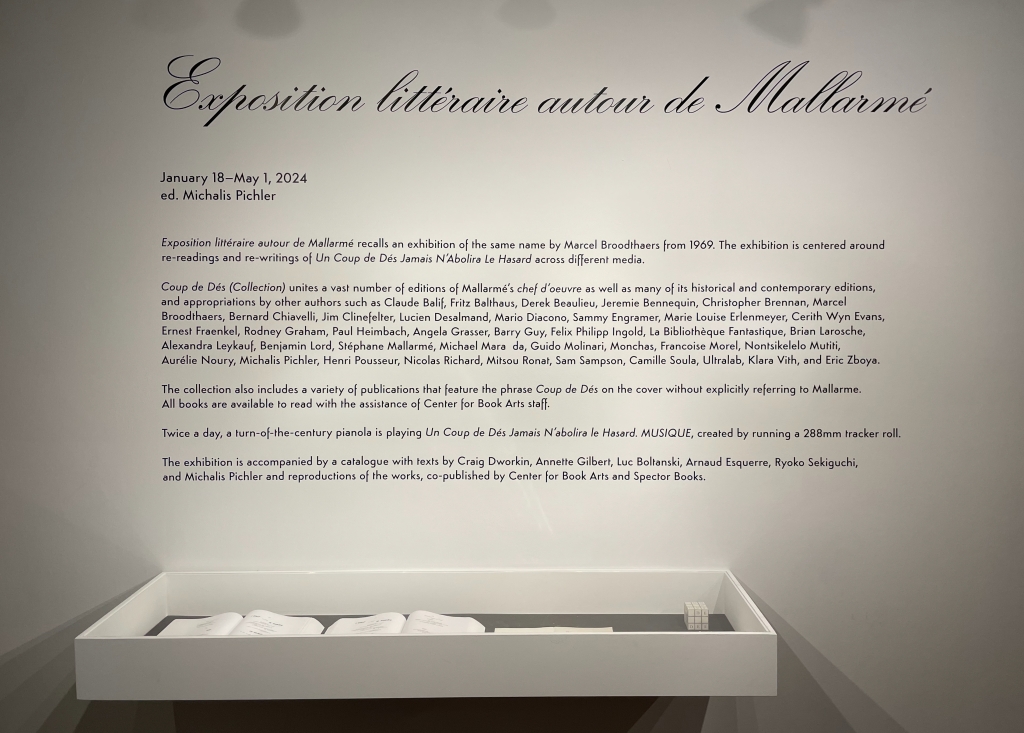

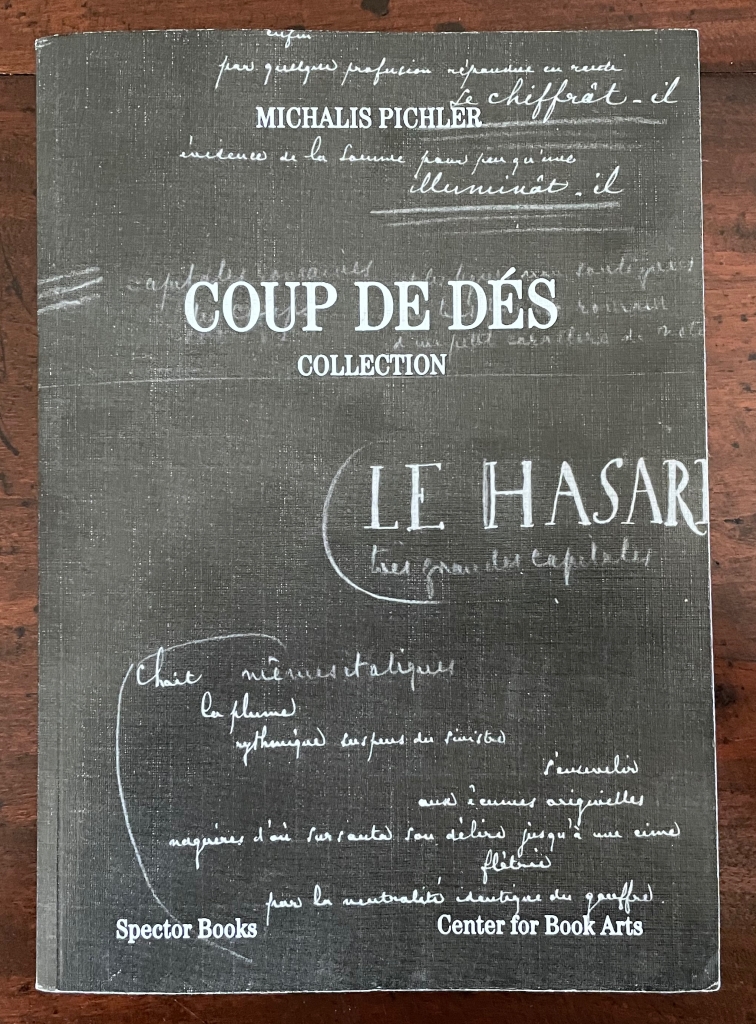

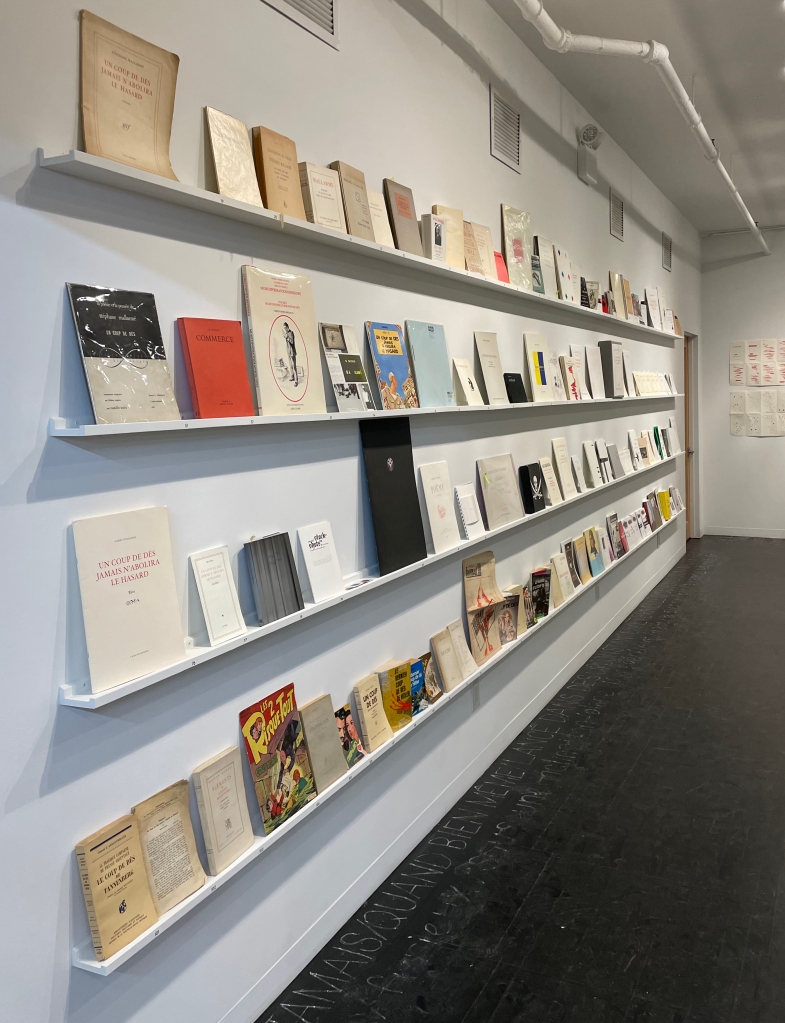

With this exhibition and edited catalogue COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION) at the New York Center for Book Arts, Michalis Pichler does not so much ignore the question as answer it by extending the art-industrial complex. The exhibition and catalogue are more than a mere display and list of over 150 works. Taken together and with his own artistic practices, they represent a multi-faceted artwork in its own right. The core constituent of this artwork is Pichler’s extensive collection of editions of Un Coup de Dés, critical works and the numerous instances of the century-plus of appropriations, including his own, of the poem. In effect, Pichler has developed the activity of collecting, appropriating and publishing into an artistic practice.

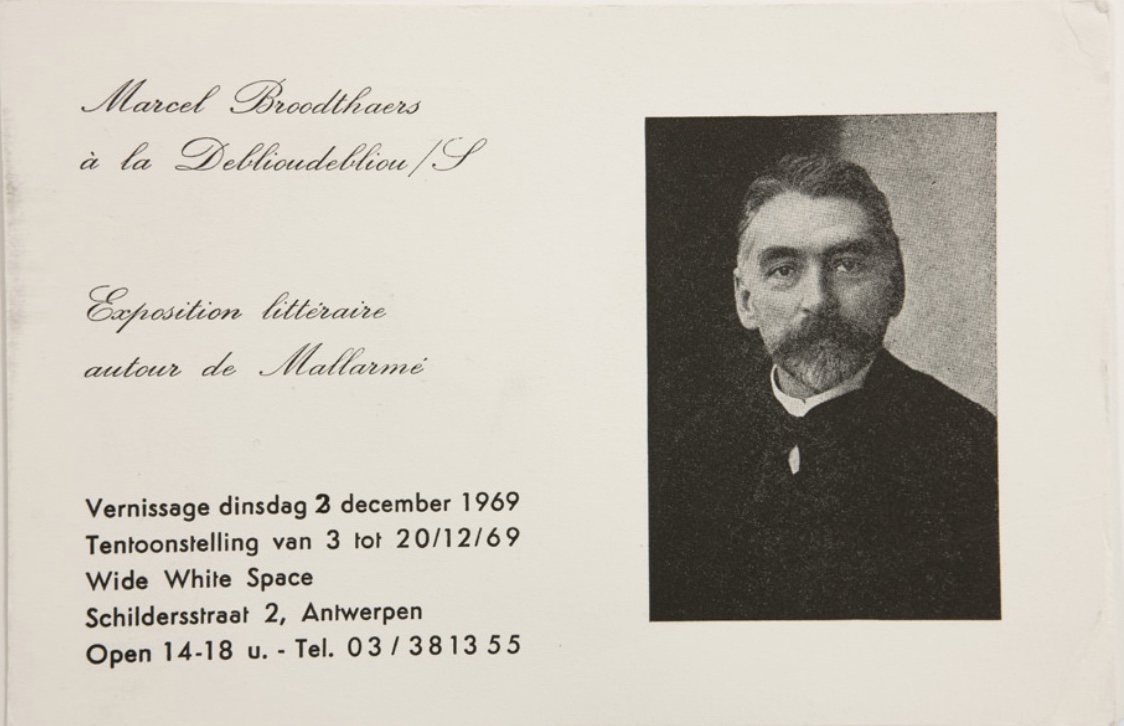

(COLLECTION) is the second and further developed instance of Pichler’s practice. The first occurred in Milan in 2016 with an invitation card appropriating the format and title of Marcel Broodthaers’ Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé at the Wide White Space in Antwerp in 1969. Pichler appropriated not only the title and card of Broodthaers’ exhibition, he appropriated its content, redisplaying Broodthaers’ landmark UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (IMAGE) and many of the editions of the poem that Broodthaers had included.

Top: Invitation to Marcel Broodthaers’ Exposition Littéraire autour de Mallarmé at the Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerp, December 1969; image courtesy of MACBA. Bottom: Invitation to Michalis Pichler’s Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé, Kunstverein Milano and Il Lazzaretto, 14 December 2016 – 28 January 2017.; with permission of Michalis Pichler.

With its introduction of his landmark (IMAGE), Broodthaers’ exhibition marked a transformative moment for the Mallarméan art-industrial complex. By blotting out the lines of Mallarmé’s poem with strips of black ink, Broodthaers elevated image over text. In its wake, we have had

- Jérémie Bennequin’s (OMAGE DÉ-COMPOSITION), (OMAGE) and (FILM)

- Raffaella della Olga’s (CONSTELLATION), (PERMUTATION) and (TRAME)

- Sammy Engramer’s (ONDE) or (WAVE)

- Benjamin Lord’s (SEQUENCE)

- Michael Maranda’s (LIVRE)

- Richard Nash’s (ESPACE)

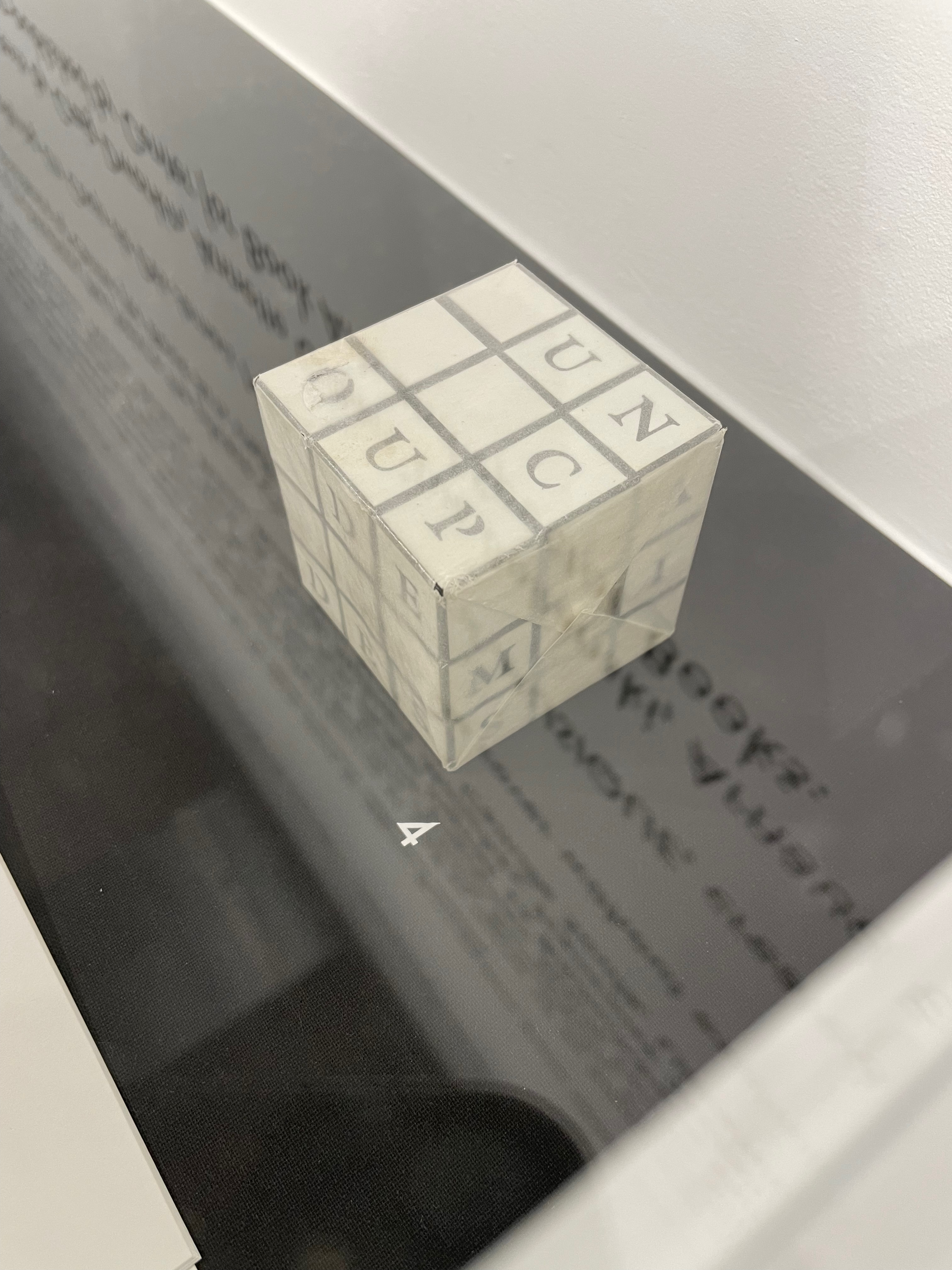

- Aurélie Noury’s (RUBIK’S CUBE) and (POSTER)

- Michalis Pichler’s (SCULPTURE) and (MUSIQUE)

- Sam Sampson’s (((SUN-O)))

- Klara Vith’s (DISCOURS I-III)

- Eric Zboya’s 2018 (VECTEUR) and (TRANSLATIONS)

Like Broodthaers’ (IMAGE), each of these appropriations remakes the poem (and sometimes a previous artist’s remaking) through its parenthetically indicated tag. For instance, Pichler’s (SCULPTURE) replaces Mallarmé’s pages with plexiglas sheets and Broodthaer’s blottings with abrasions. But Pichler’s parenthetical tag (COLLECTION) is omnivorous. It consumes again Broodthaers’ Exposition, eating Mallarmé’s poem in its several incarnations; devours all the parenthetical appropriators, including (SCULPTURE); swallows the many other appropriators lacking a parenthetical tag; and picks its teeth with works that merely allude to the poem’s title.

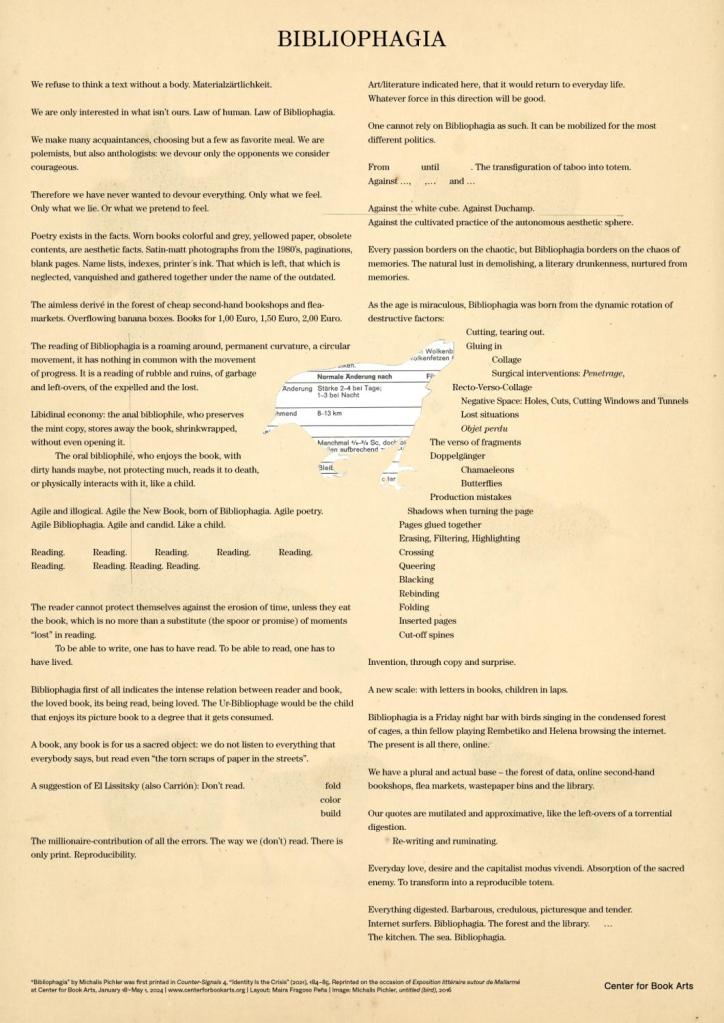

The reverse of Pichler’s displayed print Bibliophagia (2024) reveals this cannibalistic metaphor as central to the artistic practice that yields (COLLECTION) as an artwork in its own right. Visitors may miss the import of the print’s reverse side until leaving the exhibition because that side is not displayed, although it can be found on the free copy offered onsite.

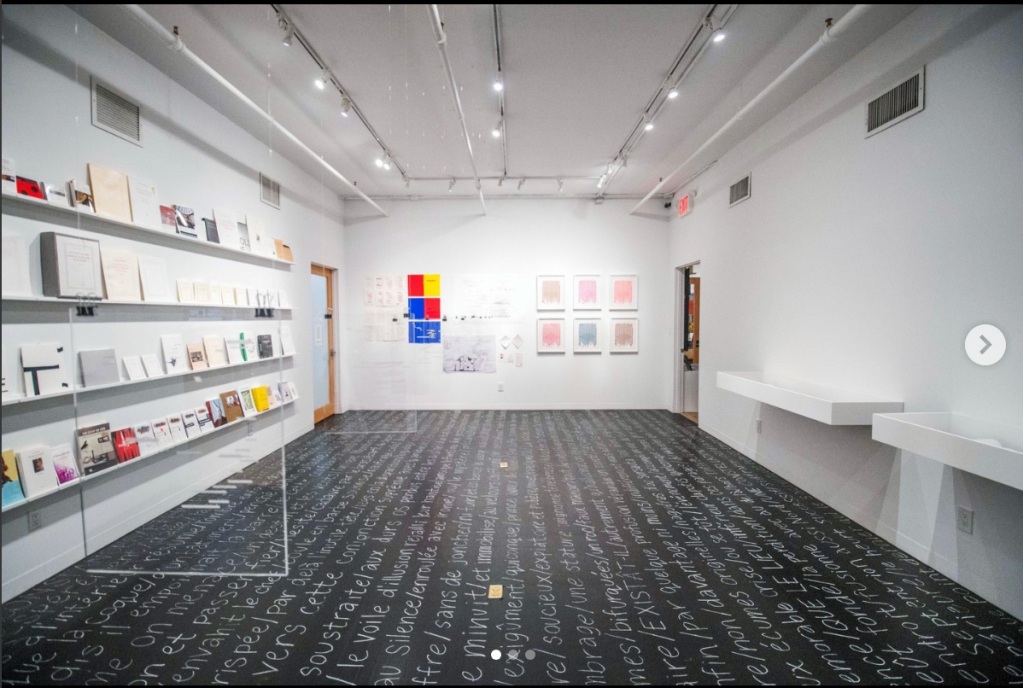

Pichler’s 2016 and 2024 exhibitions add another constituent practice to this project: that of performance art, but with the visitor as performer. Like a work of performance art, an exhibition has a venue and displays that serve as the stage setting. Performance art and exhibitions are both time-delimited, fixed within the period and hours of the venue’s availability. Where the length of a performance is constrained by the artist/performer’s stamina, this exhibition’s is constrained by the visitor’s stamina. Fortunately with Pichler’s performances, a less-than-indefatigable visitor has something other than a leaflet of performance notes as guide and souvenir: the volume COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION): Books and Ideas after Mallarmé. This volume’s three essays and two book excerpts work together with the snapshots of the exhibition to put forward this premise that (COLLECTION) is intended as an artistic work in its own right.

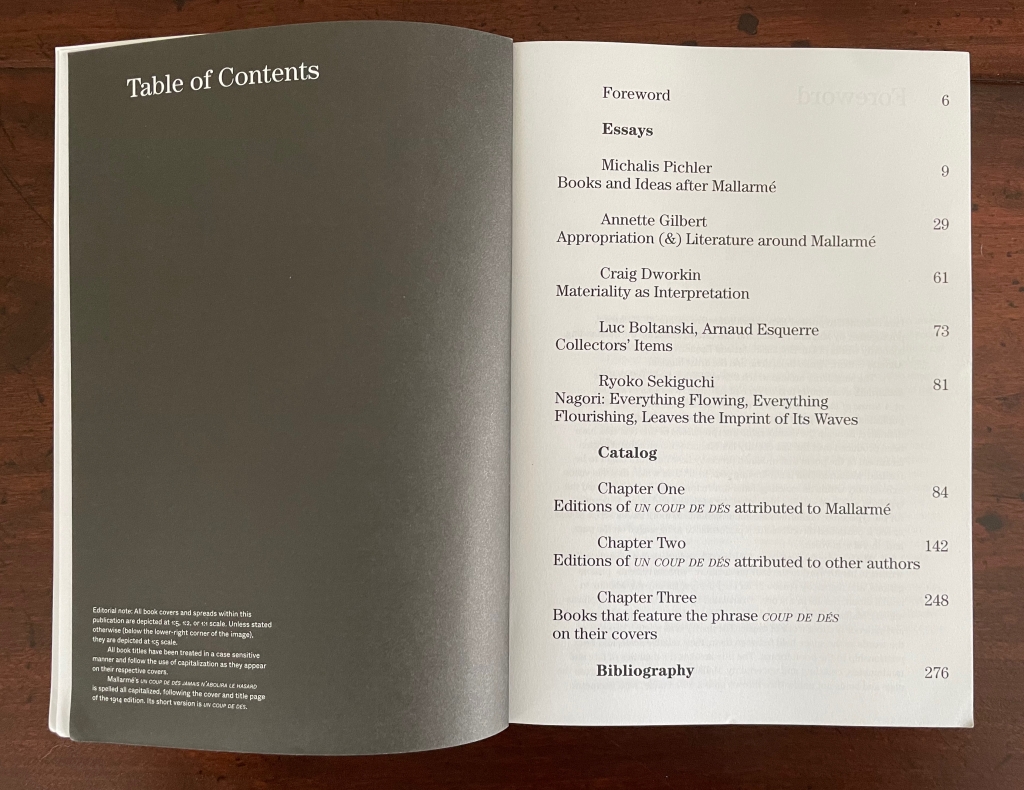

COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION): Books and Ideas after Mallarmé (2024)

Michalis Pichler (ed.)

Perfect bound paperback. H240 x W170 mm. 280 pages. Acquired from AHA-Buch, 22 January 2024. Photos: Books On Books Collection.

In addition to recapitulating the Bibliophagia manifesto, Pichler’s introductory essay provides the background to the appearance and editioning of Un Coup de Dés and also explains the relevance of the two book-excerpts. Pichler’s translation with Misaki Kawabe from Ryōko Sekiguchi’s book”Nagori” is welcome apart from any role it plays in (COLLECTION). As a concept, nagori has popped up in book art with Victor Burgin’s 2020 essay “Nagori: Writing with Barthes” and with Nagori (2023), a sculptural artist’s book by Ximena Pérez Grobet and and Kati Riquelme. Depending on context, nagori can mean the ephemeral imprint of withdrawing waves, a late-season wistfulness for the taste of early-season fruit or tea, what remains after the passing of a person, an object, an event, or the atmosphere of something missing. Pichler ties this to the absence of an authoritative edition of the poem.

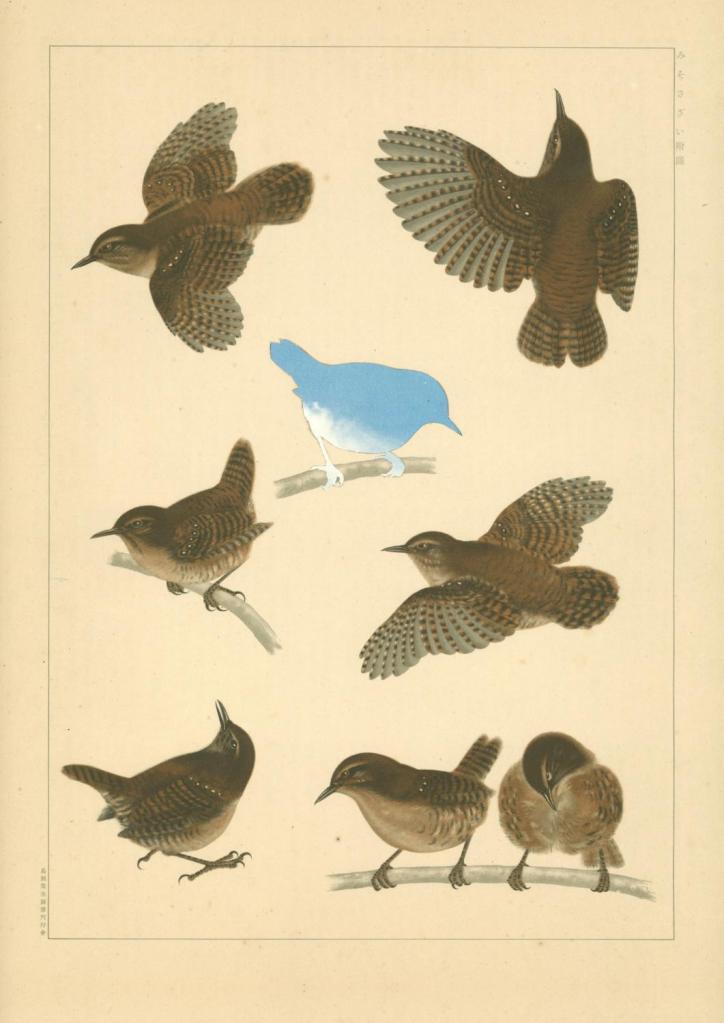

The sense of something missing also comes up in the second book excerpt: Luc Boltanski and Arnaud Esquerre’s Enrichment: A Critique of Commodities (Polity, 2020). Pichler enlists them to establish what distinguishes a collection from a heap on the one hand and a stockpile on the other (pp.73-90), not merely accumulating items in a collection but curating according to governing principles, similarities, differences, and the feel for what is missing. (Recall the “missing” bird on both sides of Bibliophagia above?) In a sense, the act of collection or curation is a form of appropriation, and in that sense, Pichler’s governing principle of collection has been the appropriation of appropriations but always with a hungry eye for the next. To paraphrase Bibliophagia, Pichler has made many acquaintances and chosen but a few as his favorite meal.

Here, Annette Gilbert’s essay chimes in to assert that “curating has now ascended to a full-fledged artistic practice in its own right” where “literary curators are also increasingly succeeding in creating ‘a new artist-like identity’ for themselves and inscribing their ‘collections’ as autonomous works of their own right in their own oeuvre, of which Michalis Pichler’s COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION) … is a striking example.” (p.52)

Tellingly, Gilbert’s assertion comes in the context of mapping the field of “appropriation literature” as a manifestation of the pressures of an affluent society giving rise to “new strategies of artistic production and the creation of meaning” (p.29), echoing Felix Stalder’s observation: “in the digital condition, one of the methods (if not the most fundamental method) enabling humans to participate […] in the collective negotiation of meaning is the system of creating references.” (p.31) And what is Pichler’s collecting if not a systematic creation of references among the works in (COLLECTION)?

Craig Dworkin’s essay bizarrely and brilliantly connects Mallarmé with another system of creating references: Alphonse Bertillon’s identification system for the Parisian Préfecture de Police. Not only did the Bertillon system overlap with Mallarmé in the 19th century, it turns out that its principles map directly onto Mallarmé’s conception of Le Livre as stacks of unbound sheets filed in the cubbyholes of a filing cabinet and awaiting a theatrical performance of a séance leader’s withdrawing sheets to arrive at a poem (rather than the flic‘s pulling them to arrive at the identification of a suspect). Dworkin goes on to make convincing links to Klaus Scherübel’s styrofoam edition of Le Livre, to Dan Graham’s “Poem Schema”, to Ernest Fraenkel’s Les Dessins trans-conscients de Stéphane Mallarmé, to Mario Diacono’s and Marcel Broodthaers’ blotted versions of the poem, to Derek Beaulieu’s tattered sails (after un coup de des), and to Rainier Lericolais’ and Michalis Pichler’s die-cut perforations, among others. All of which leads to Dworkin’s assured conclusion: “The editions and appropriations of UN COUP DE DÉS alone are substantial enough to have led to an exhibition, and a sense of the assembled collection, UN COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION), as an artistic work in its own right.” (p.67)

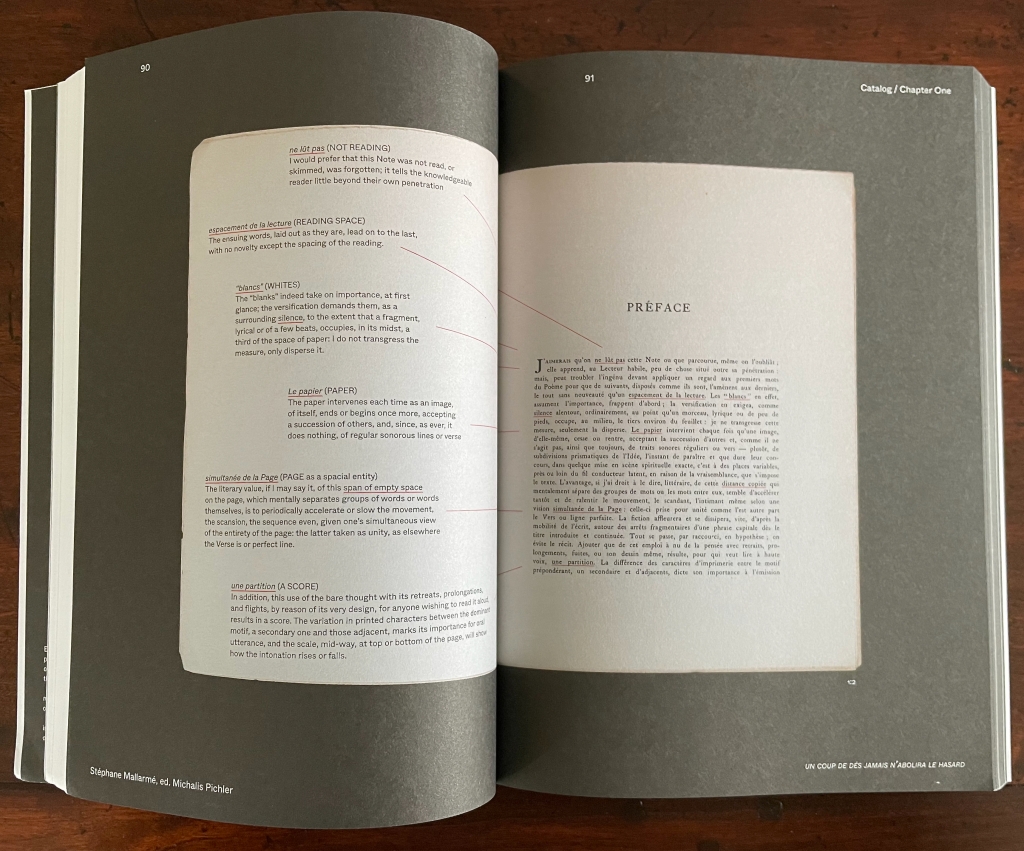

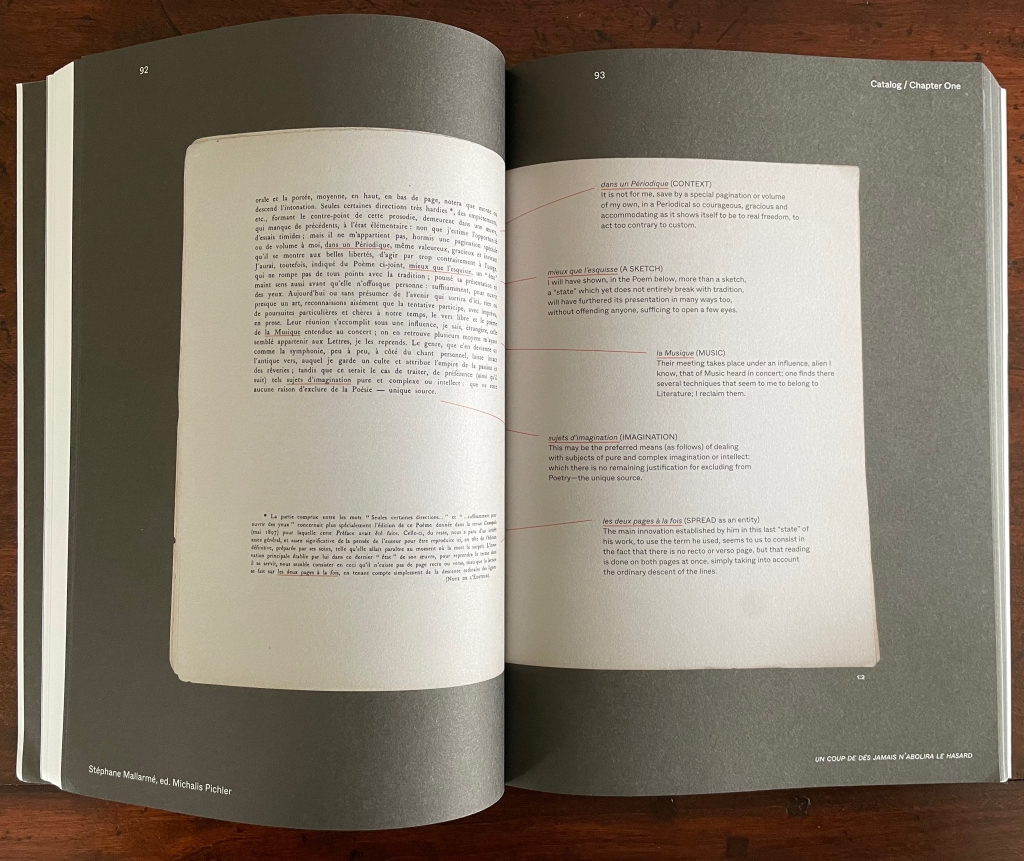

The “Catalog” section, which includes over 150 pages of images of book covers and spreads variously at 1:5, 1:2 and 1:1 scale against a black background, presents more items than are displayed in the exhibition. One of them is Pichler’s editorial intervention in that very first editorial intervention in the poem: the PRÉFACE required of Mallarmé in 1897 by Cosmopolis and reproduced by his son-in-law in the 1914 edition. Here Pichler’s annotations call out 10 key aspects of the poem and Mallarmé’s thoughts about it that would lead to the overlapping industry of artistic homage, appropriation, expropriation, transculturation, transvaloration and cannibal translation or bibliophagia as Pichler variously puts it.

This contribution from Pichler not only echoes many of Annette Gilbert’s points in mapping the field of appropriation literature but also confirms her assertion: “Pichler’s project … positions itself decidedly both as an independent artistic work and as artistic research, which demonstratively opens itself up to chance and serendipity through its collection policy – in resonance with a dice roll as the object of the collection ….” (p.39).

COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION) — the bookwork — belongs in any library with an interest in Mallarmé, book art or the cutting edge of contemporary art. The exhibition at the Center for Book Arts closes on 1 May 2024. Copies of the catalogue for sale remain on hand as do free copies of the print Bibliophagia (2024) and the invitation from Pichler’s 2016 Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé.

As with the 2016 exhibition, the majority of items on display were accessible, making the exhibition a rare hands-on experience.

Courtesy of Center for Book Arts

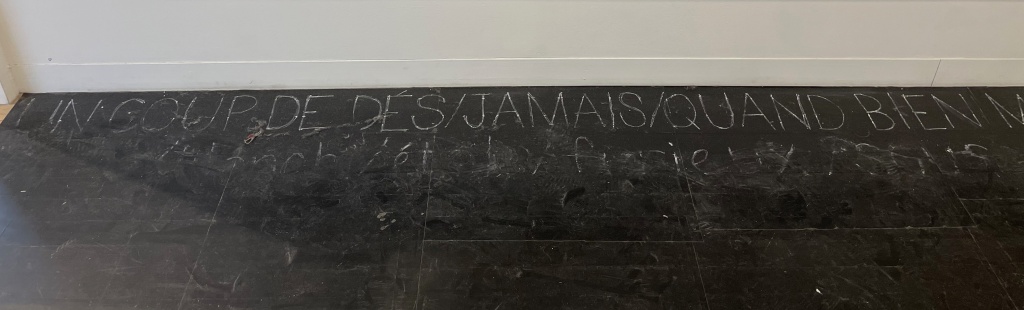

Before the opening, the poem was chalked onto the floor of the main display room. Within minutes of the opening, the visitor traffic had erased most of it.

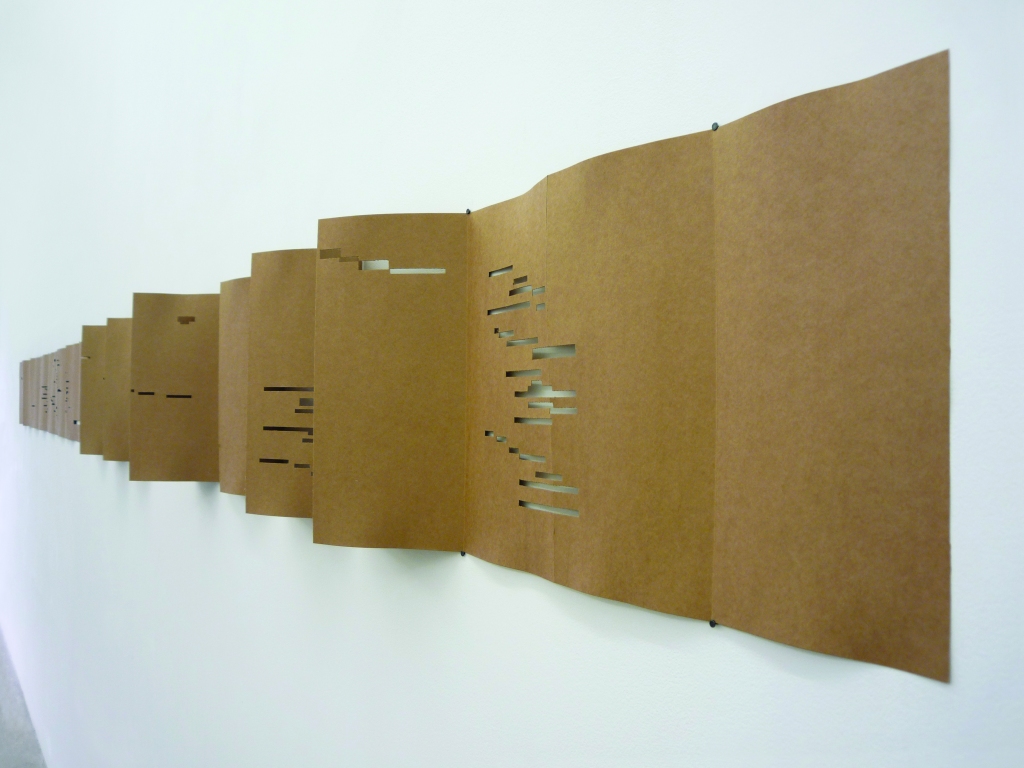

On the wall: Bibliophagia, 2016 and 2024. Hanging: UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (SCULPTURE) 2016;

Against the wall: UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (MUSIQUE) 2009

Michalis Pichler

UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (MUSIQUE) 2009

Michalis Pichler

UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (RUBIK’S CUBE) 2005; UN COUP DE DÉS JAMAIS N’ABOLIRA LE HASARD (POSTER) 2008

Aurélie Noury

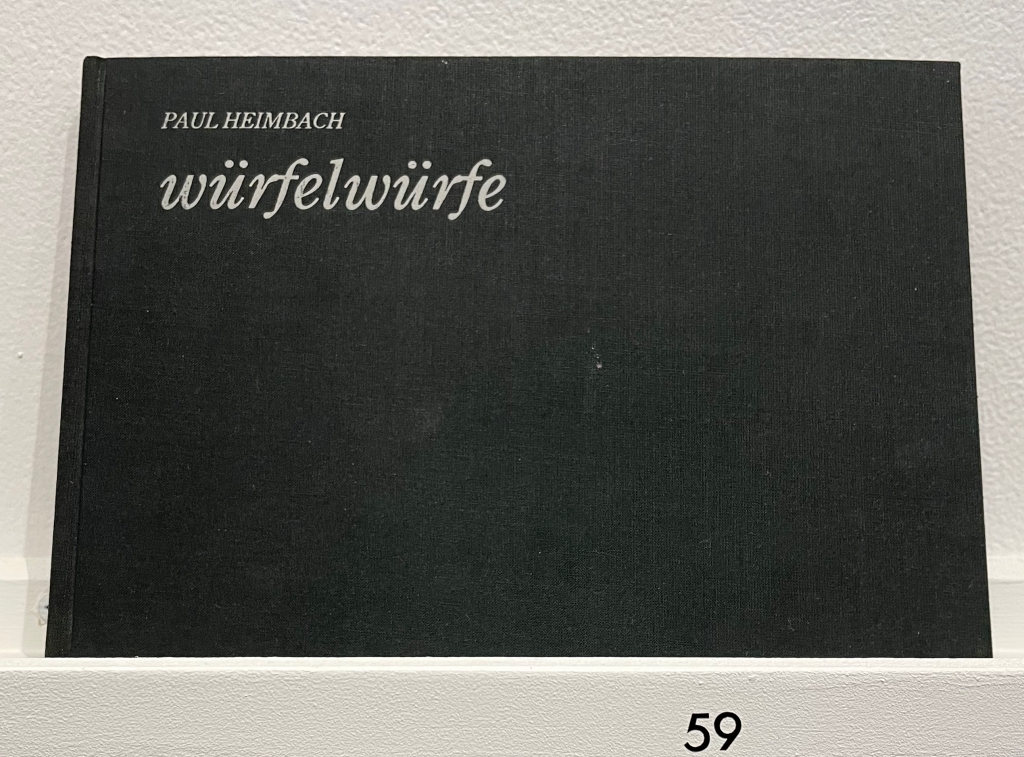

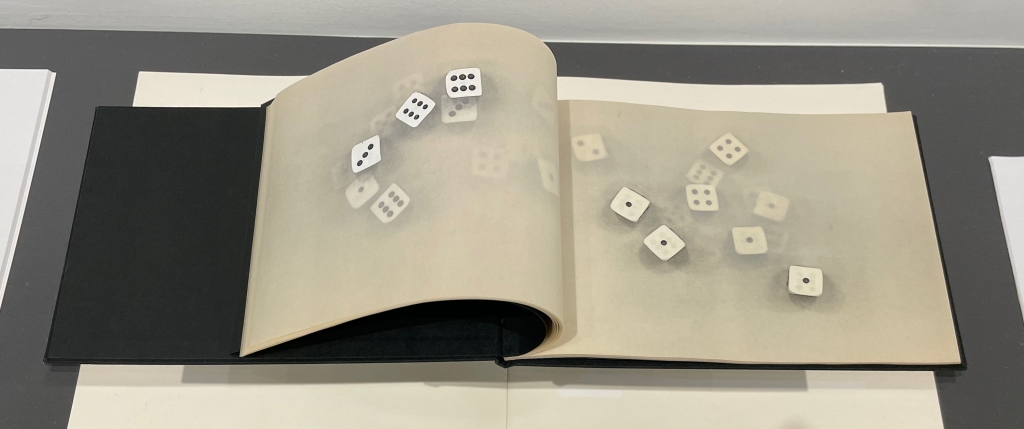

Paul Heimbach was perhaps the first after Marcel Broodthaers to use translucent paper in an artist’s book interpretation of Mallarmé’s poem. In würfelwürfe, for each roll of the dice, the results on the upper faces appear on a recto page, the results on the bottom faces appear on the verso.

Declaration of interest: COUP DE DÉS (COLLECTION): Books and Ideas after Mallarmé kindly cites Books On Books’ “‘Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira l’Appropriation’ — An Online Exhibition“.