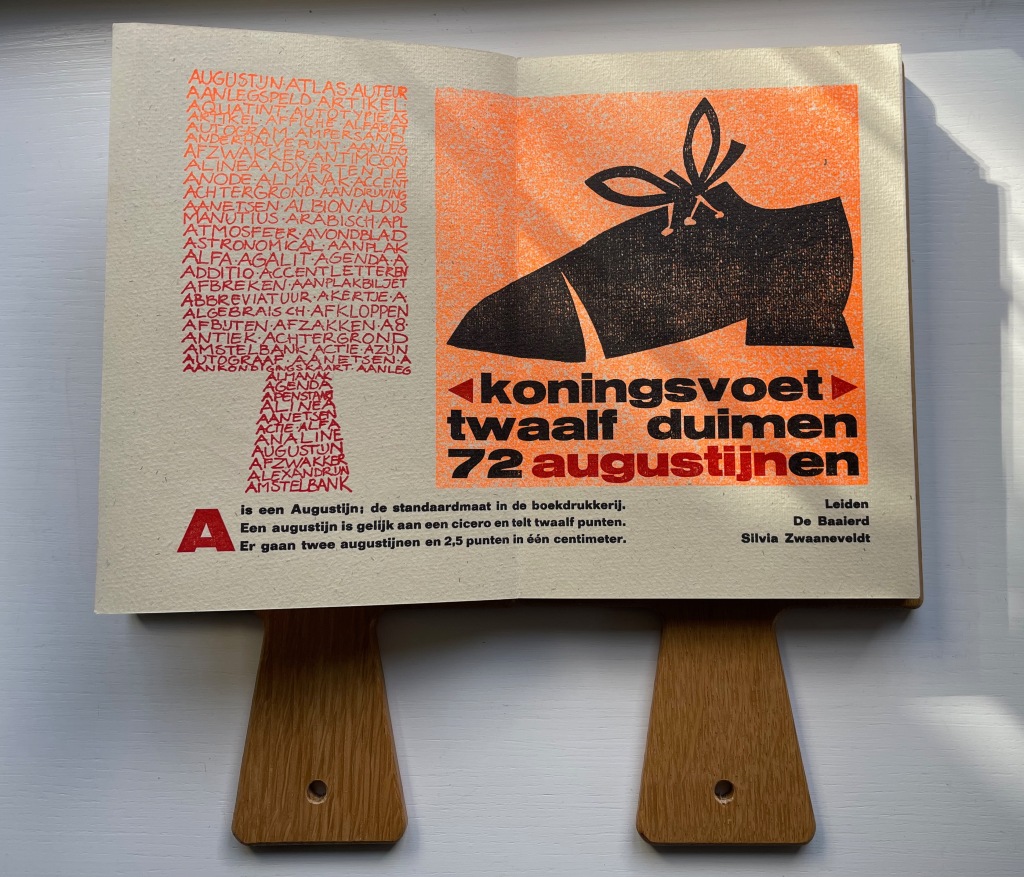

Battledore (2019)

Battledore (2019)

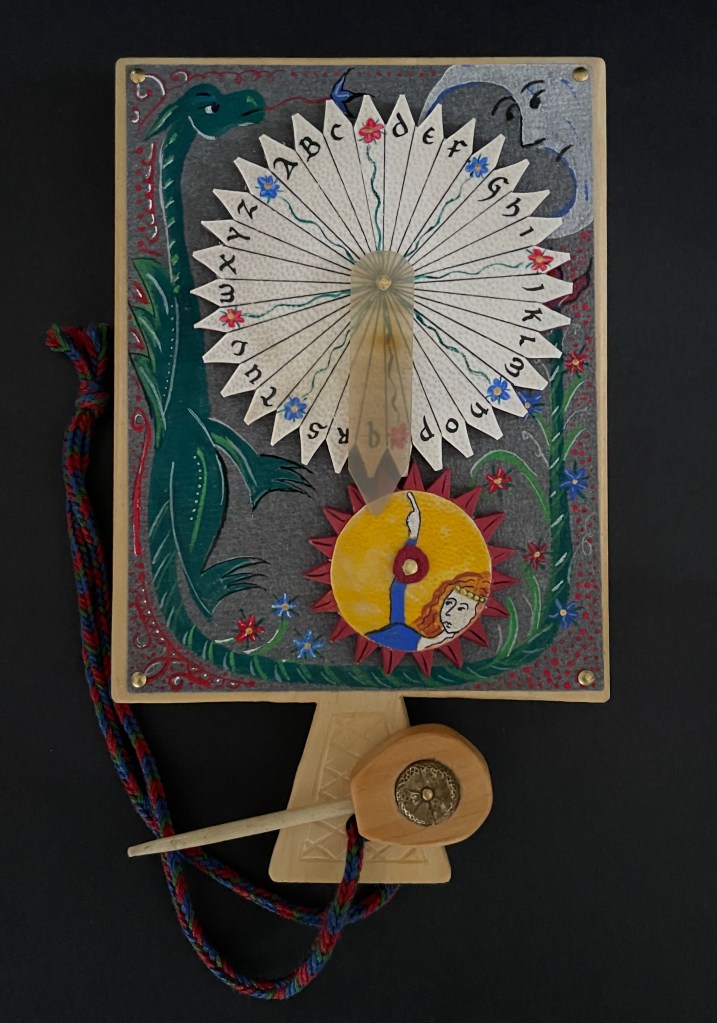

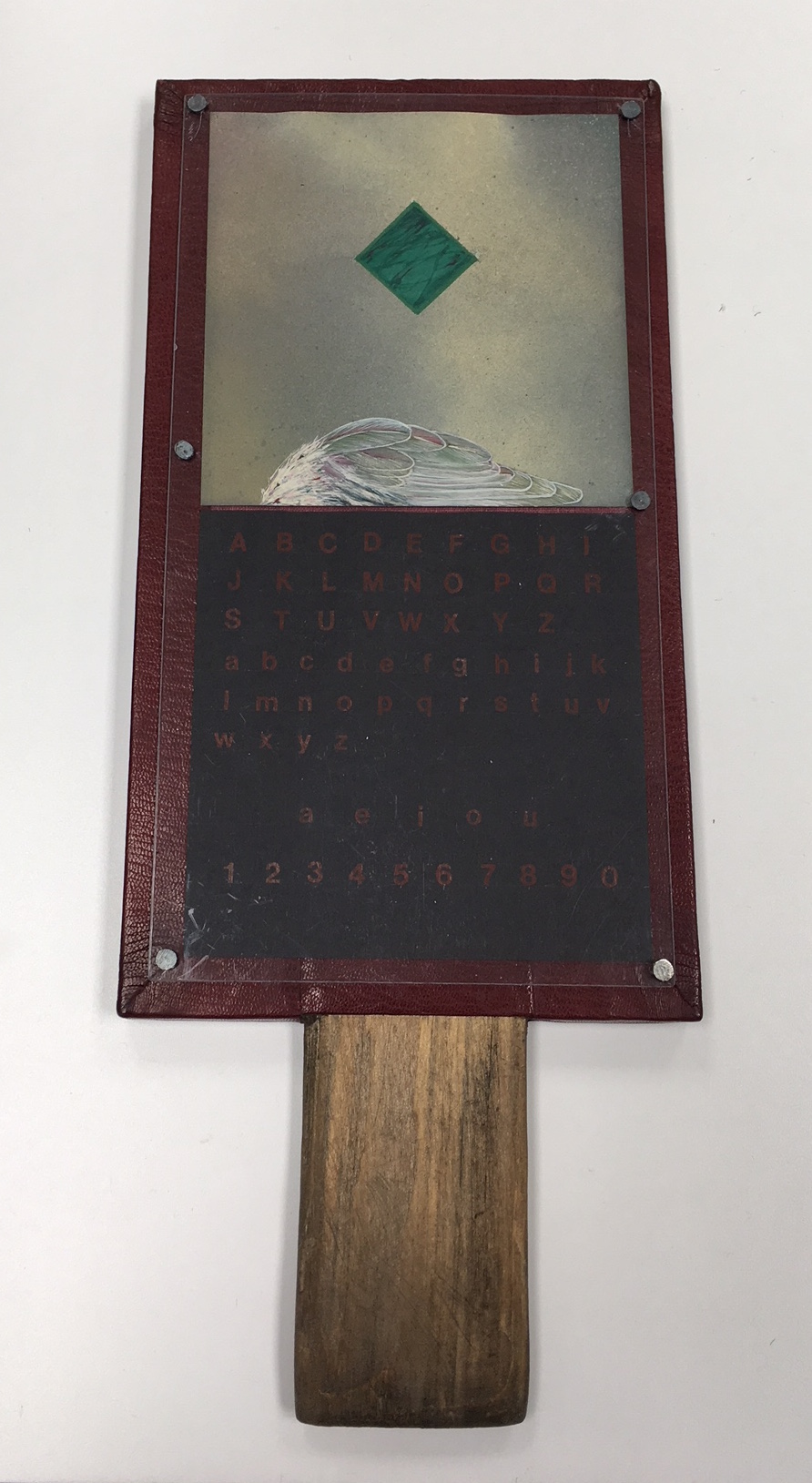

Bård Ionson

Digital photo of oscilloscope art on walnut, with leather straps & tacks. H229 x W127 mm. Animation of oscilloscope art with Artivive. Resolution: 3840 × 2160 px. File format: mp4. Duration: 1’0″ sec. File Size: 74.1 MB. Acquired from the artist, 1 March 2019.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of the artist.

The artifact displayed here is a vehicle for a digital artwork in which oscilloscope drawings are animated in augmented reality and which exists as an NFT (Non-Fungible Token). To view the digital artwork, open the camera on a smartphone, point it at the QR code below, and download the Artivive app. Open the Artivive app and position the phone’s camera over the artifact or even its image above.

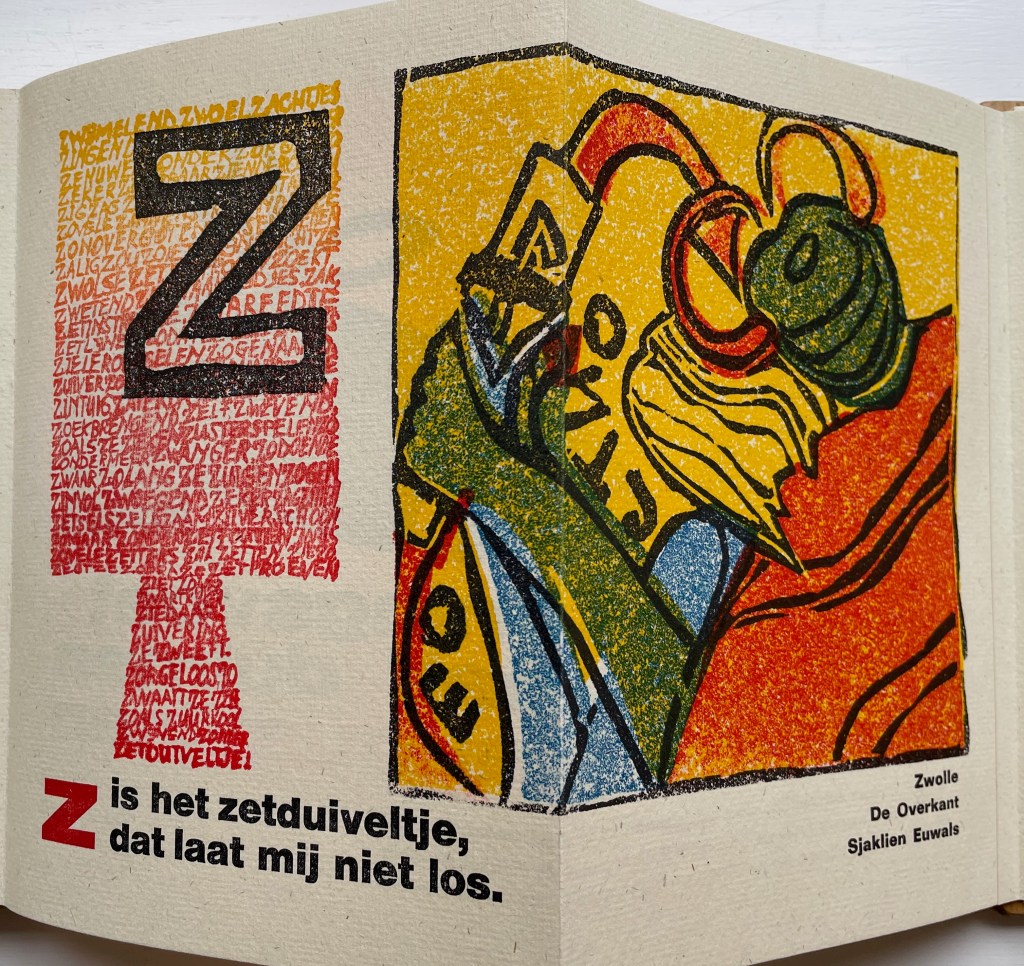

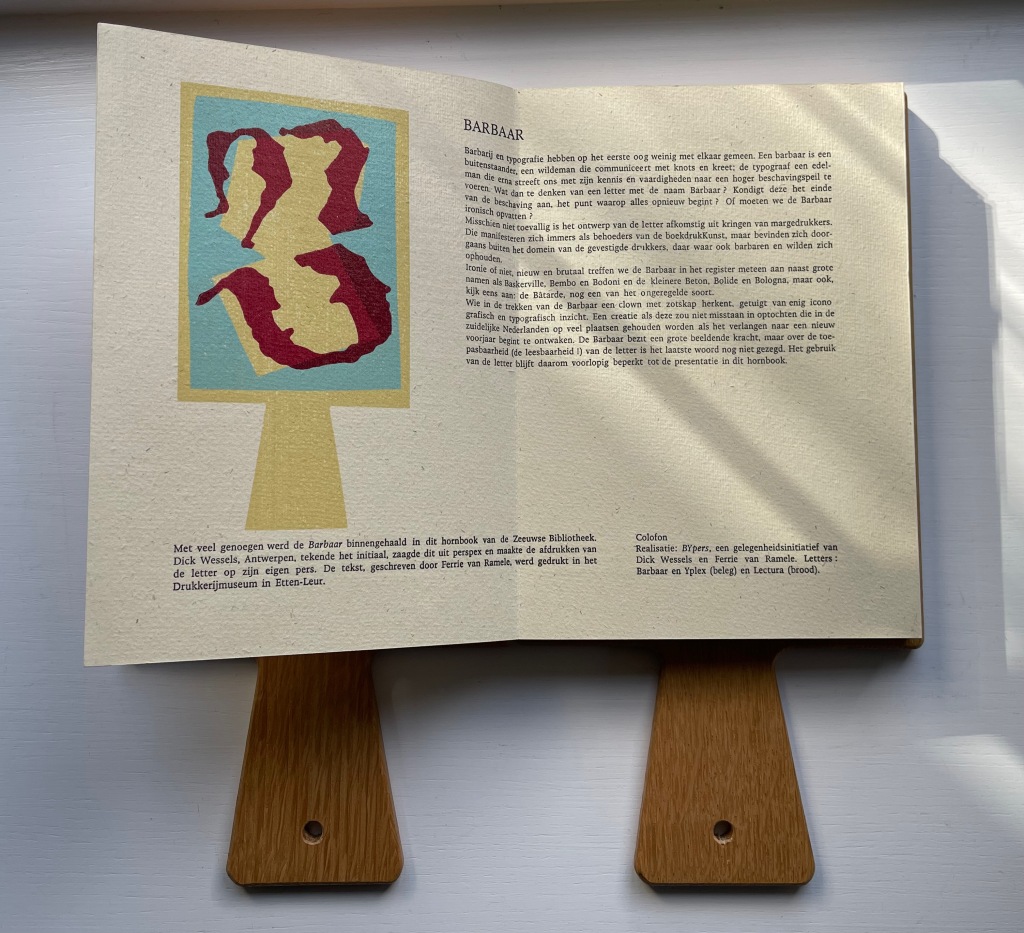

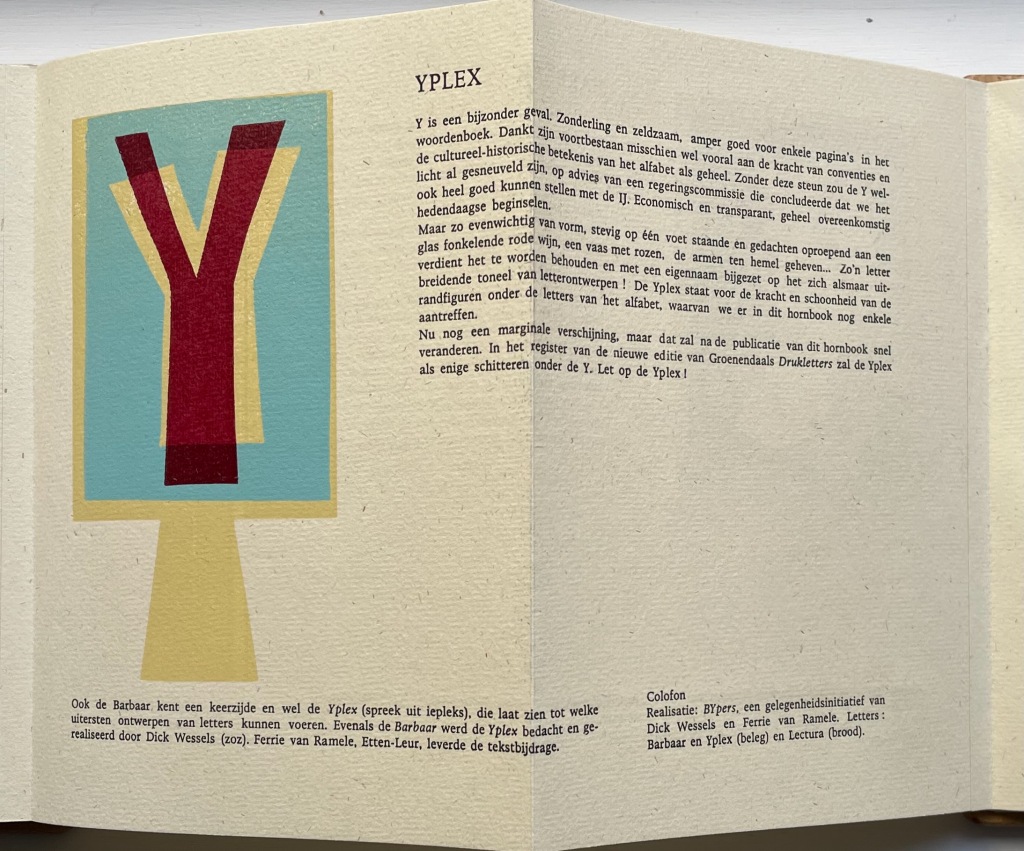

Each of the alphabet characters transforms into a logo (or image of a product associated with the company behind the logo). The letters represent Apple, Boeing, Comcast, Disney, Exxon, Ford, Google, HBSC, ING, JP Morgan Chase, Koch, Lockheed Martin, Microsoft, Nestle, Orbital, Phiser, QinetiQ, Raytheon, SkullCandy, TiVO, Unilever, Volume Integration, Winchester, Xerox, Yandex and Zinga.

Now that A is for Apple Inc. rather than the fruit, Ionson wonders, “What are our children learning as they navigate digital devices vs. when children used wooden tablets with narrow ideas presented with pictograms.” He goes on about the entities behind Battledore‘s letters, “Many of these are companies that manufacture weapons of war or are players in an information war. Many countries and organizations are using the information space of social media and news in a disinformation war. It is a digital battle now.”

To drive this home with several layers of irony, Battledore is offered as the learning tool needed to

Train your children for the battles of the 21st Century. Where brands, countries and organized crime compete for your allegiance. Using art, history, finance, education, news, war, social media and religion they fight to keep a hold on your mind. Learn to fight back by subverting the tools they wield.

At one layer of irony, the physical artifact shown above lies dormant just as it did until the teacher “activated” it with classroom recitation of the letters. But now, in augmented reality, the letters seem to come to life revealing hidden entities associated with them. Now, the reader/viewer has to engage in a digital transaction, point a digital handheld device at the letters, and peer to see and learn, letter by letter, what the letters “really” stand for — all while a looping track of electronic battle-game sounds plays on. Viewed on a laptop or desktop, these video clips at Elementum, Patreon and ARTificial show the transformations without the need of a smartphone. Caveat: whether phone or laptop, lower the speakers’ volume before activating!

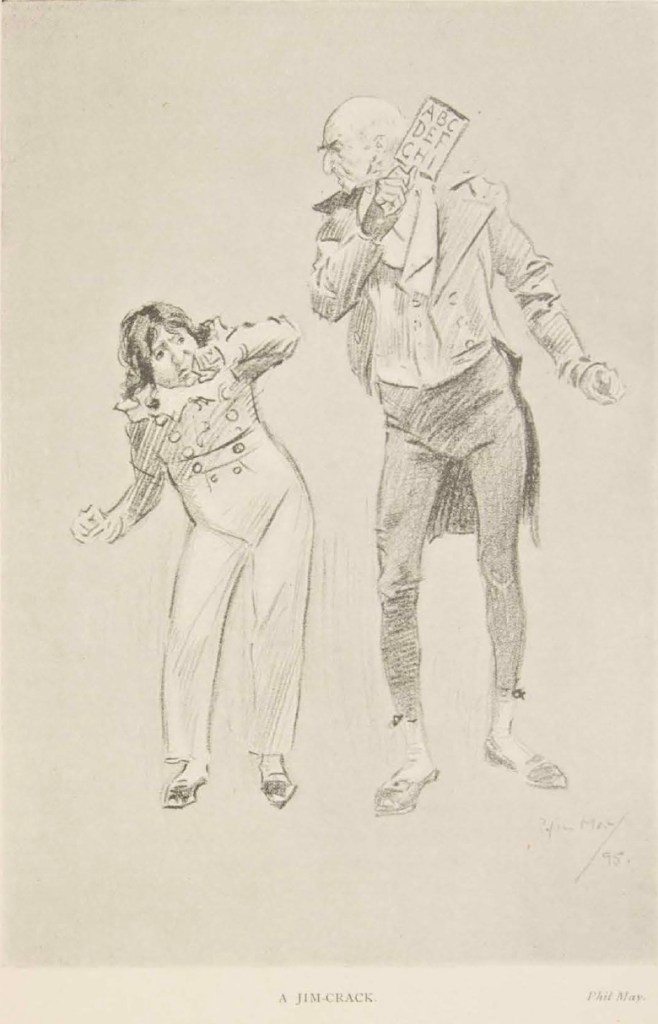

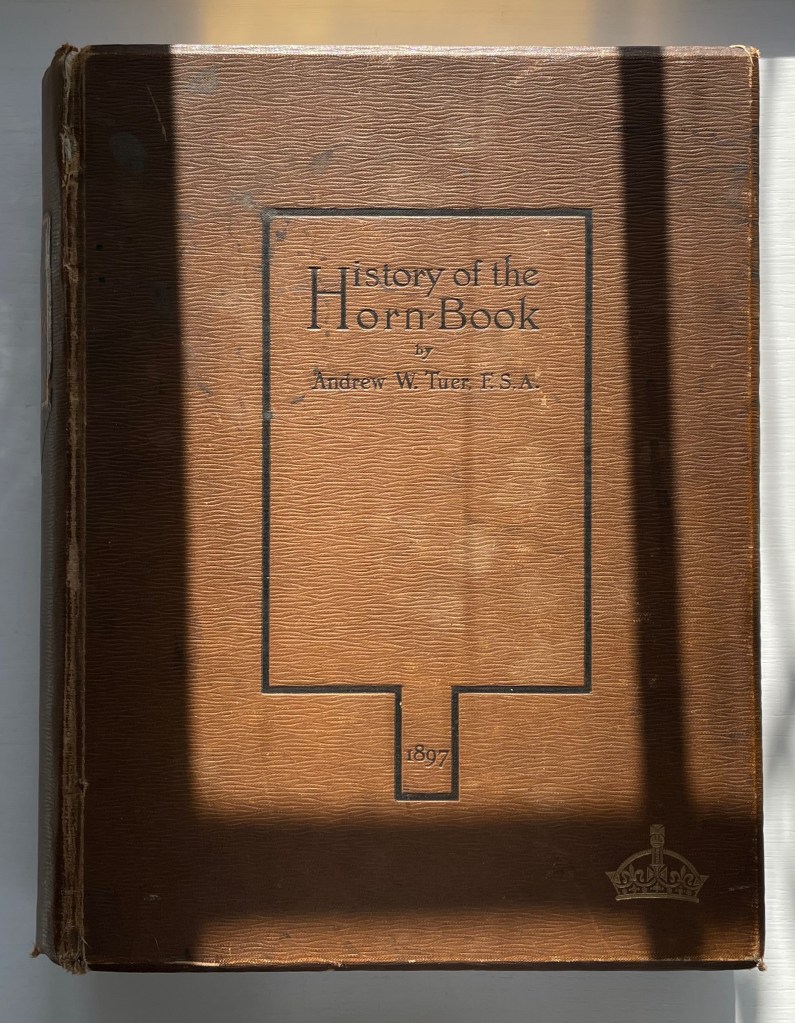

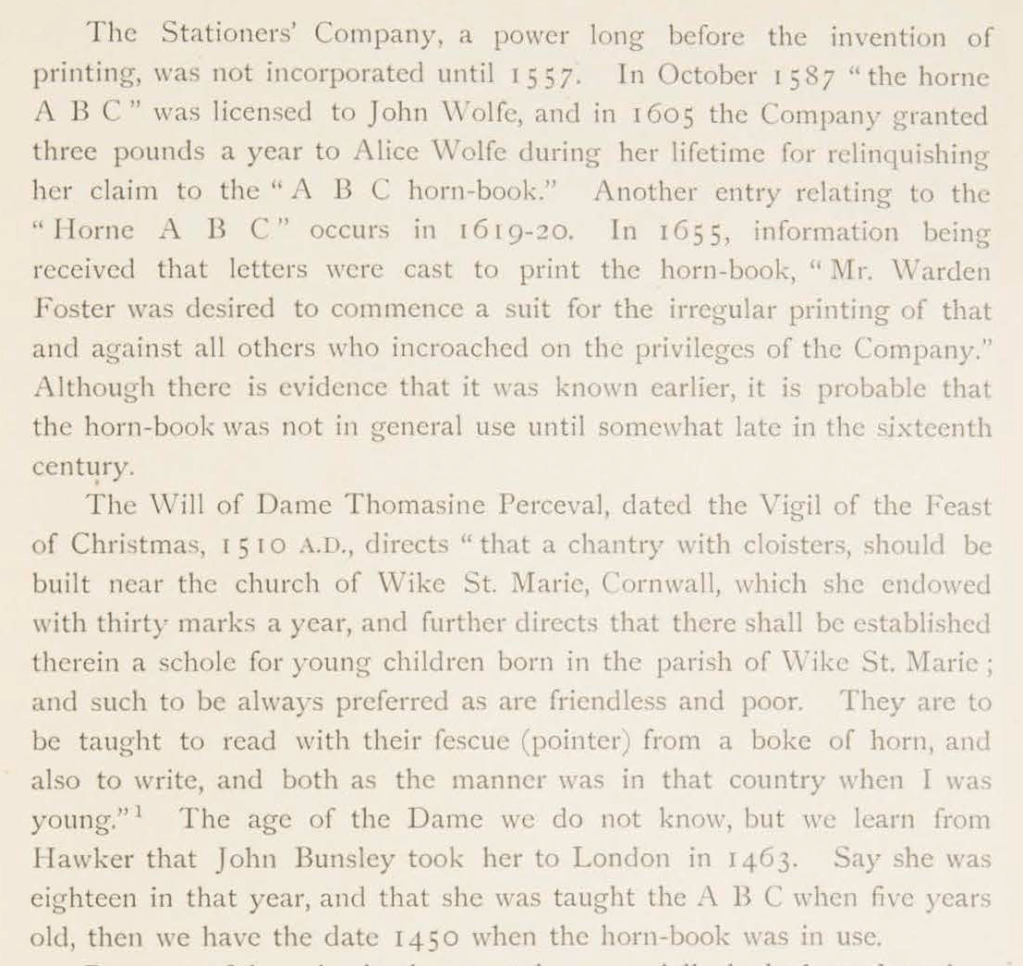

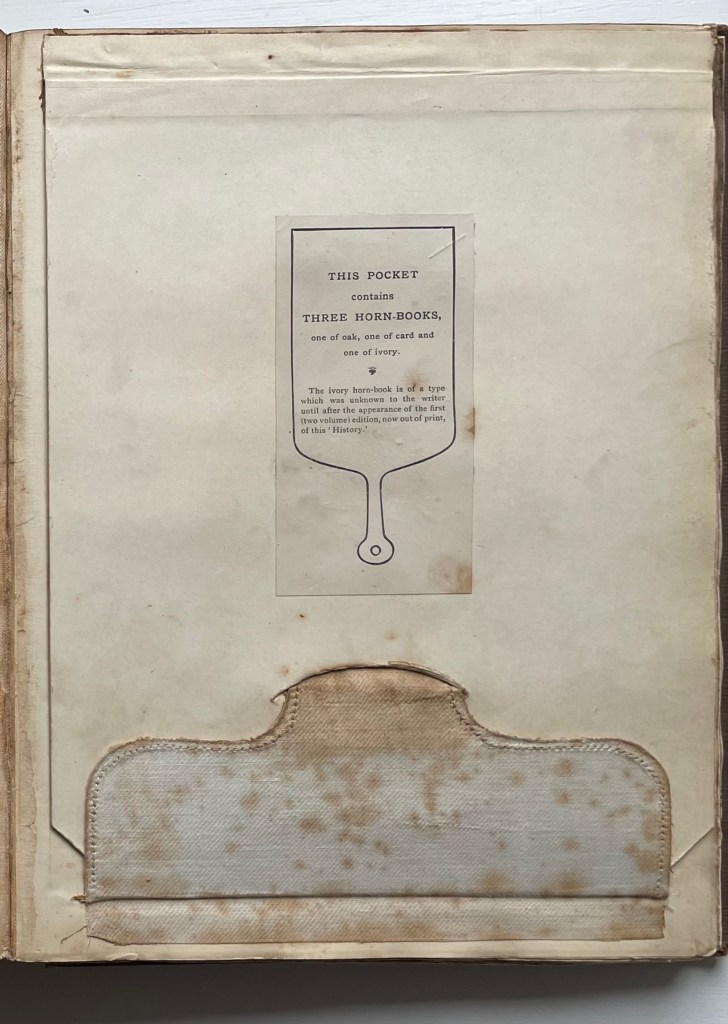

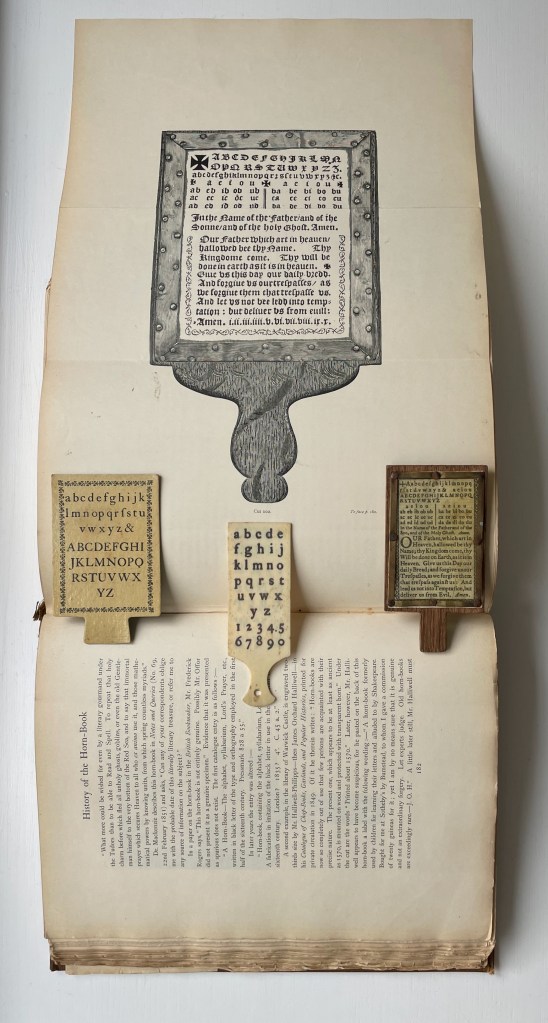

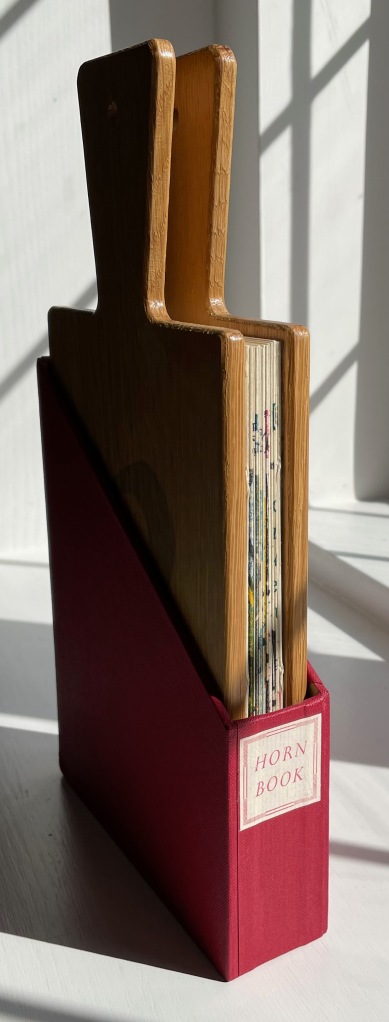

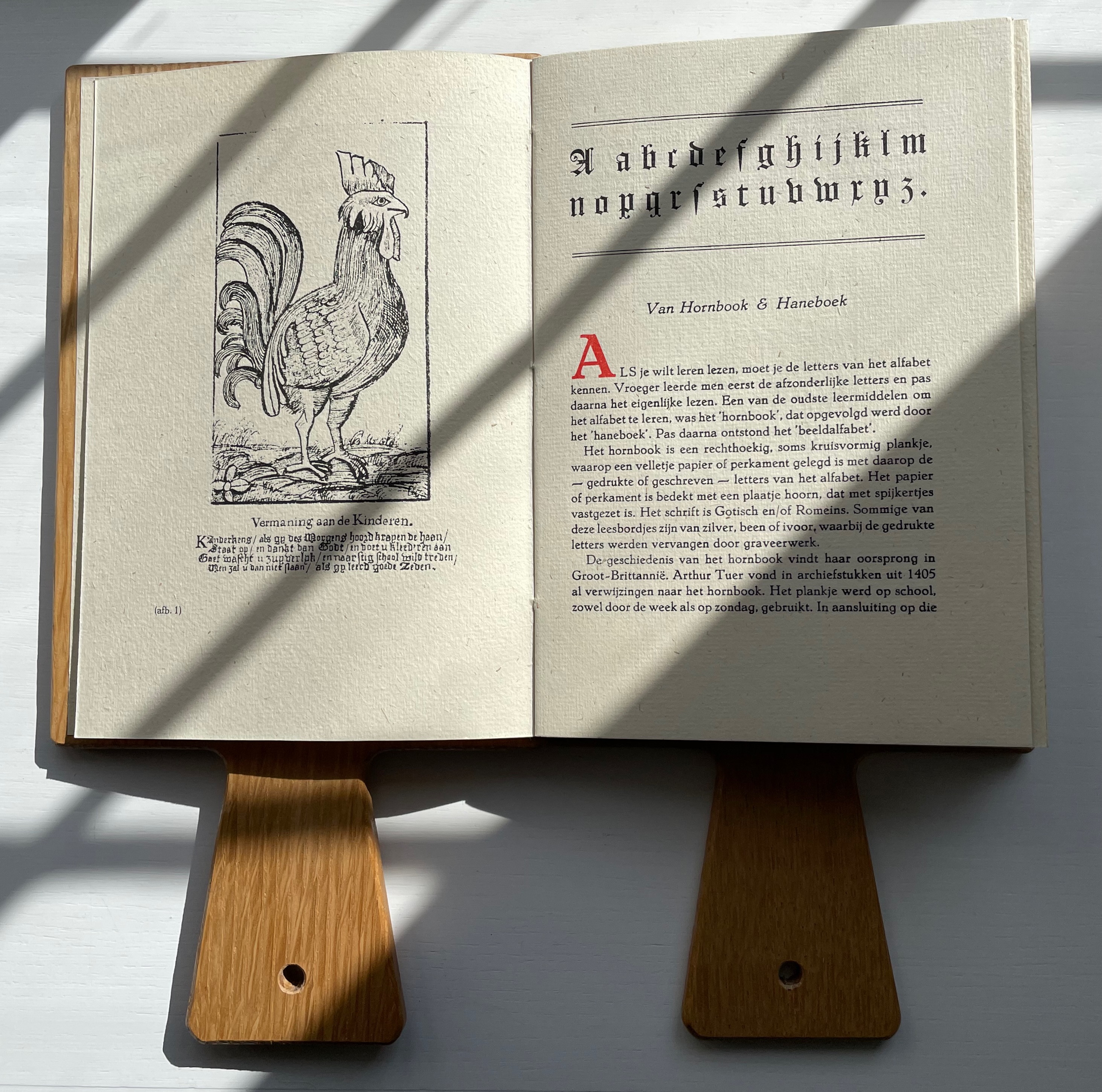

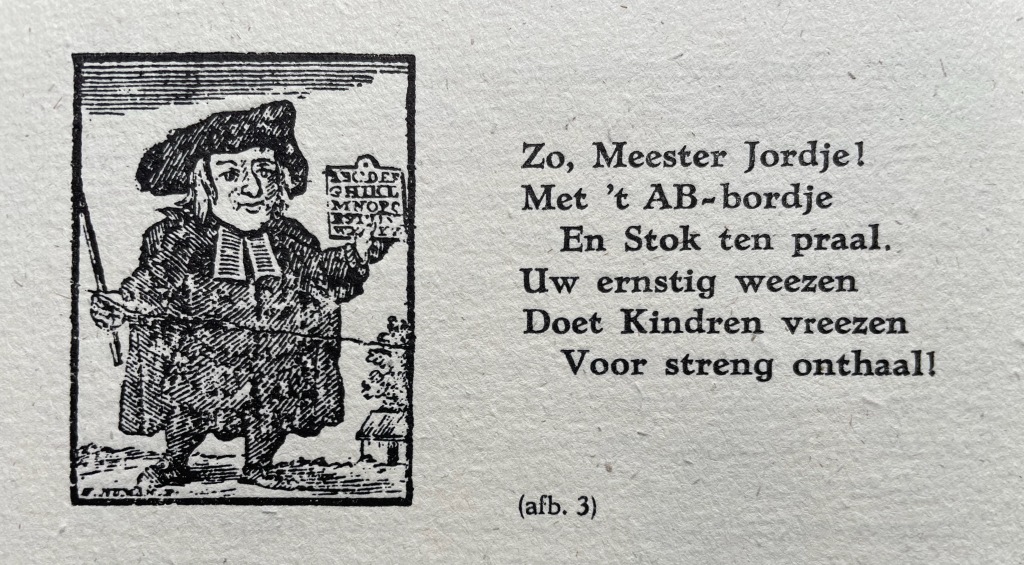

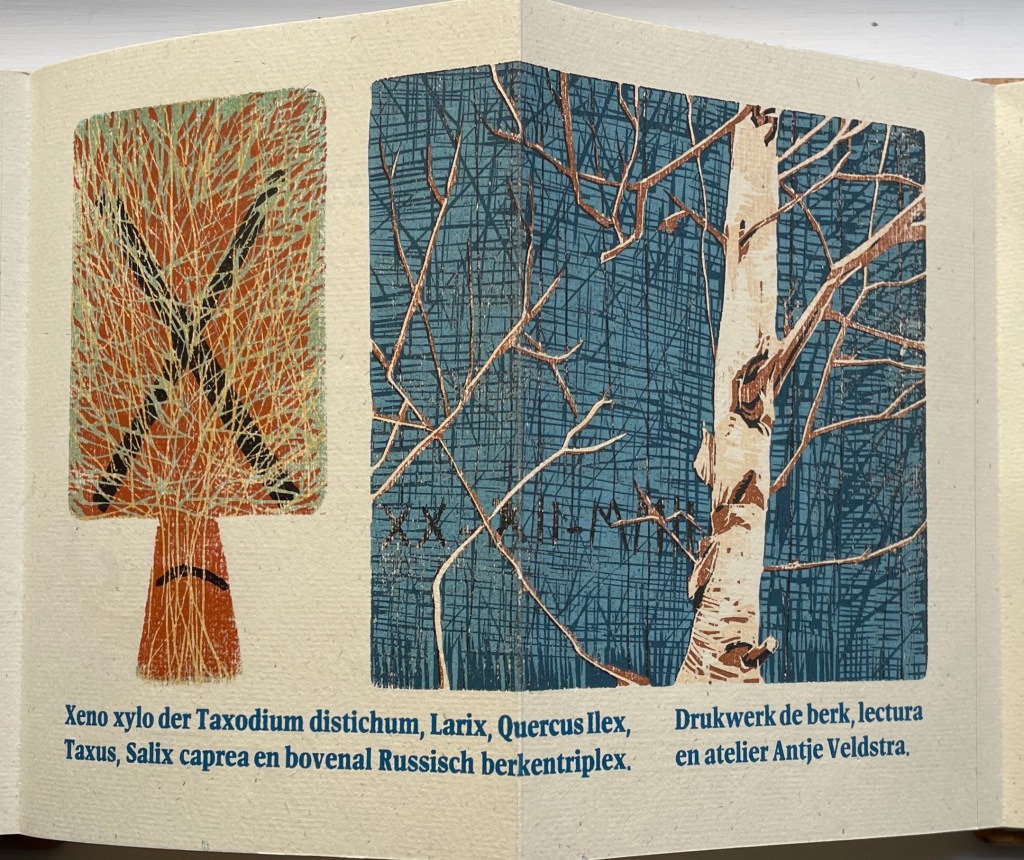

While the word “battledore” serves the artist’s metaphoric purpose, it introduces another layer of irony (unintentional according to the artist) in that the physical artifact is a horn-book, not a battledore, which was the later paper version of the horn-book. An additional unintentional irony is that, as illustrated by Andrew White Tuer, the “dean” of horn-book history, the old artifact itself was often wielded as a weapon.

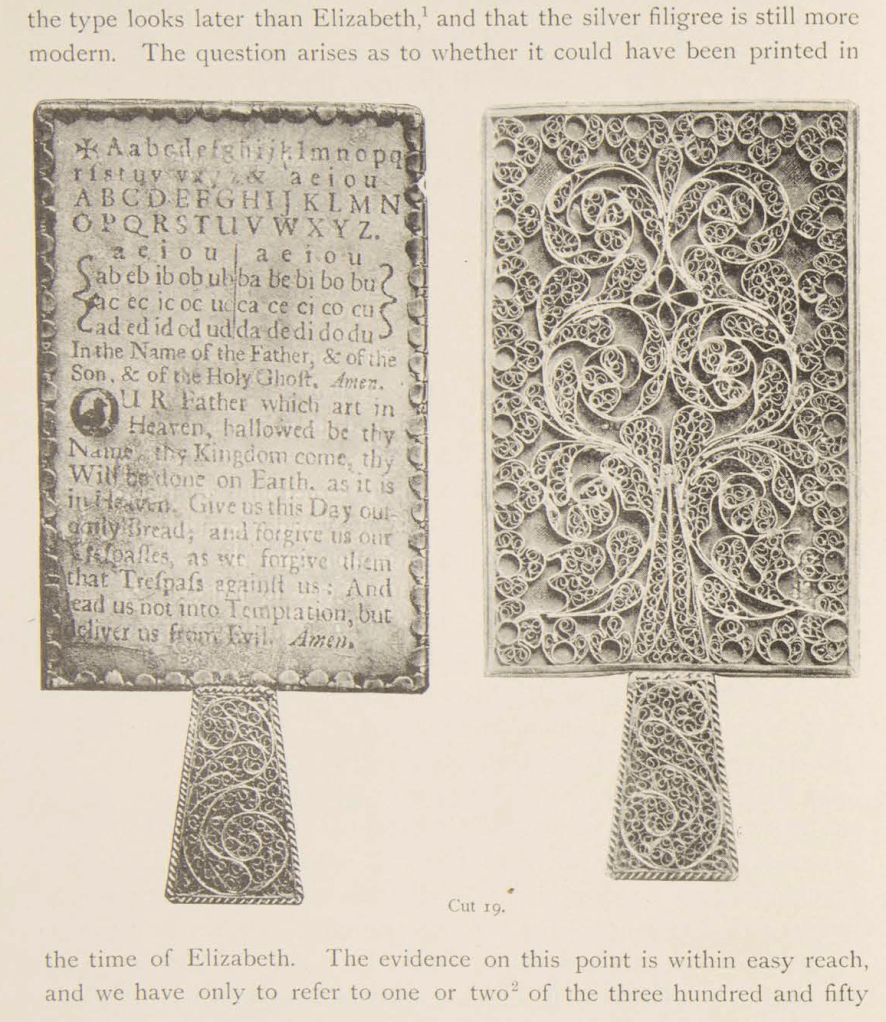

From Andrew White Tuer’s History of the Horn-Book (1897)

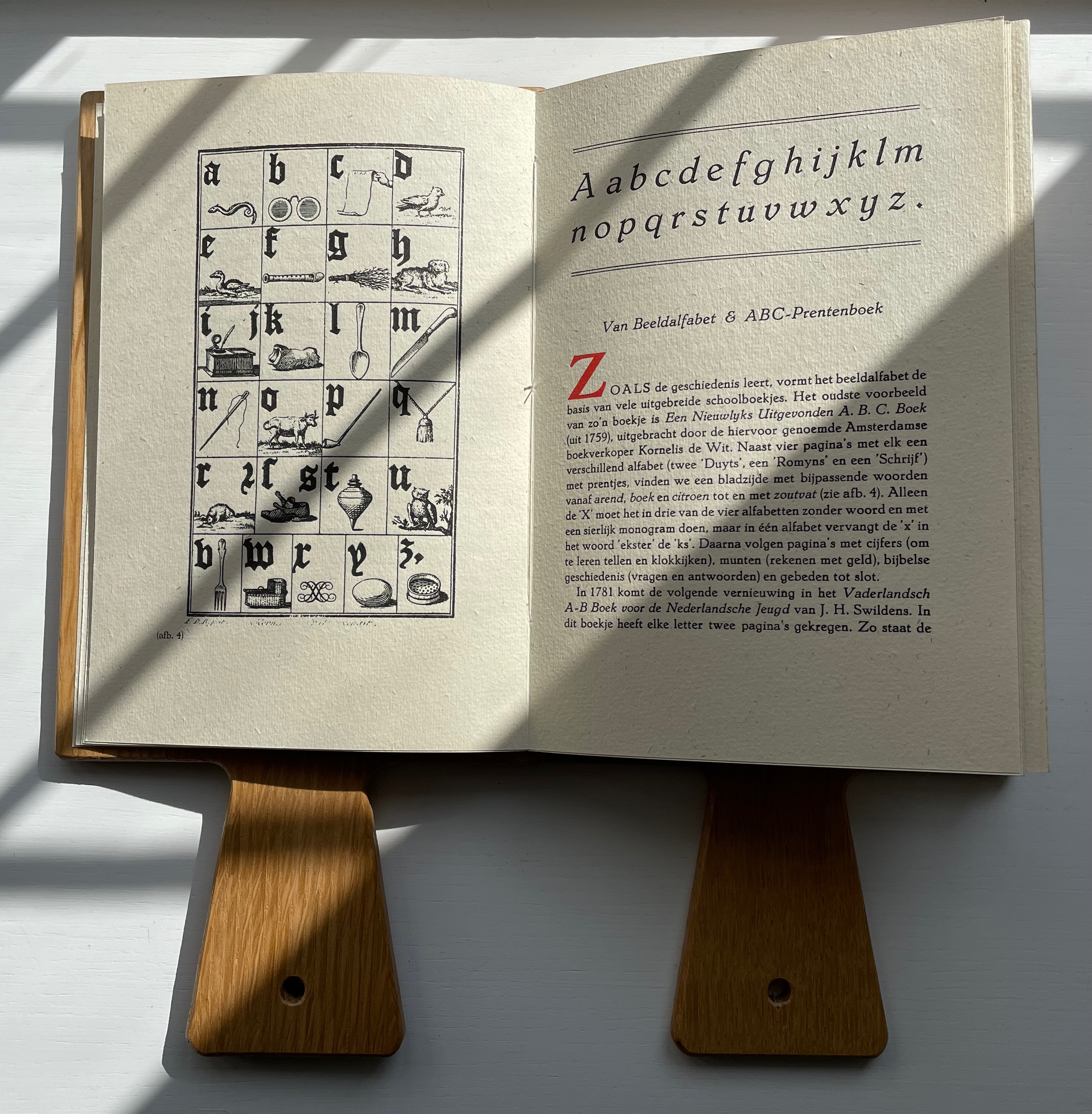

Some transformations are easy to follow and connect with a corporate entity. Others — such as the Q becoming a missile launcher because Q is for QinetiQ — require a bit of digging (online, of course). The original teaching device was not without its “corporate” — or rather religious, economic and patriotic — associations, but they were more obvious in the text, emblem and images on both front and back of the artifact.

Facsimile horn-books. Real cow horn is used for the cover of the horn-book at the lower left.

Gene Wilson

The NFT element of this work is yet another level of irony. It begins with a paradox and a pair of causes. The paradox is ownership in the digital age. Most digital objects — downloadable music or book files — are not owned securely. Whether subject to the supplier’s whims or errors (like Amazon’s now infamous overnight removal of Orwell’s 1984 from its customers’ Kindles) or to obsolescence (by operating system upgrades or by outright abandonment of file formats such as Adobe Flash), we do not so much own digital assets as lease them with fingers crossed for luck while the vendors’ fingers are crossed behind their backs.

The irony raised by Battledore‘s NFT status is the underpinning technology’s claim of redefining and securing unique ownership in a digital work of art. A long explanatory article in The Verge provides an amusing and clear explanation of non-fungible tokens and blockchain technology. Although a digital artwork can be copied many times by many viewers even if it’s included with an NFT,

… NFTs are designed to give you something that can’t be copied: ownership of the work (though the artist can still retain the copyright and reproduction rights, just like with physical artwork). To put it in terms of physical art collecting: anyone can buy a Monet print. But only one person can own the original.

A metaphysical or aesthetic precursor to all this can be found in Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”. He writes,

The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity. And

that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art.

So in Benjamin’s terms, the Monet original has authenticity, it has aura. NFTs and blockchain technology aim/claim to replace the “presence of the original”, its “unique presence”, its “aura” with “ownership of the work” as the “prerequisite to authenticity”. By associating a piece of wood, leather, metal tacks and inscribed plastic with the digital asset, Ionson physically and ironically underscores the paradox of digital ownership.

The NFT feature of Battledore also carries with it a pair of causes. The first cause has an analogue in the late 20th-century theories about book art: that this new form of art arose as a means of bypassing art galleries and gatekeeping authorities of art. Likewise, NFTs and blockchain technology have their roots in peer-to-peer (P2P) networks in which data resides in whole or distributed state across a network of distributed servers. The purpose of P2P is to protect data from the threat and vulnerabilities of centralized control. Battledore leverages its digital format and that anti-authoritarian tradition of NFTs to subvert the corporate enemy on the digital battlefield.

The second cause, related to the first, is economic and financial and linked to copyright. In the physical world, authors’ and artists’ ability to be remunerated from the sale and re-sale of copies or original works is attenuated. They might receive royalties from copies sold by the intermediary publisher or a percentage from an original sold by the gallery or to a collector, but there is no economic framework for remuneration from subsequent transactions. NFTs and blockchain technology provide the digital artist an option for ongoing remuneration. Whenever the NFT is exchanged, a new block in the chain arises, and the whole chain is aware of it. So the digital artist can set financial terms not only for the initial financial transaction but also for subsequent ones.

When the Books On Books Collection is donated to the Bodleian Libraries, the chain of digital ownership will extend by one more block. The wallet in which the Battledore NFT and financial terms, if any, reside will transfer to the Bodleian with a digitally secure chain of custody and provenance. Of course, with the accompanying transfer of the physical artifact associated with the NFT, the artist and collector will be giving an ironic wink of the eye to the amusement and relief of the Keeper of Rare Books at the Bodleian.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress)“. Books On Books Collection.

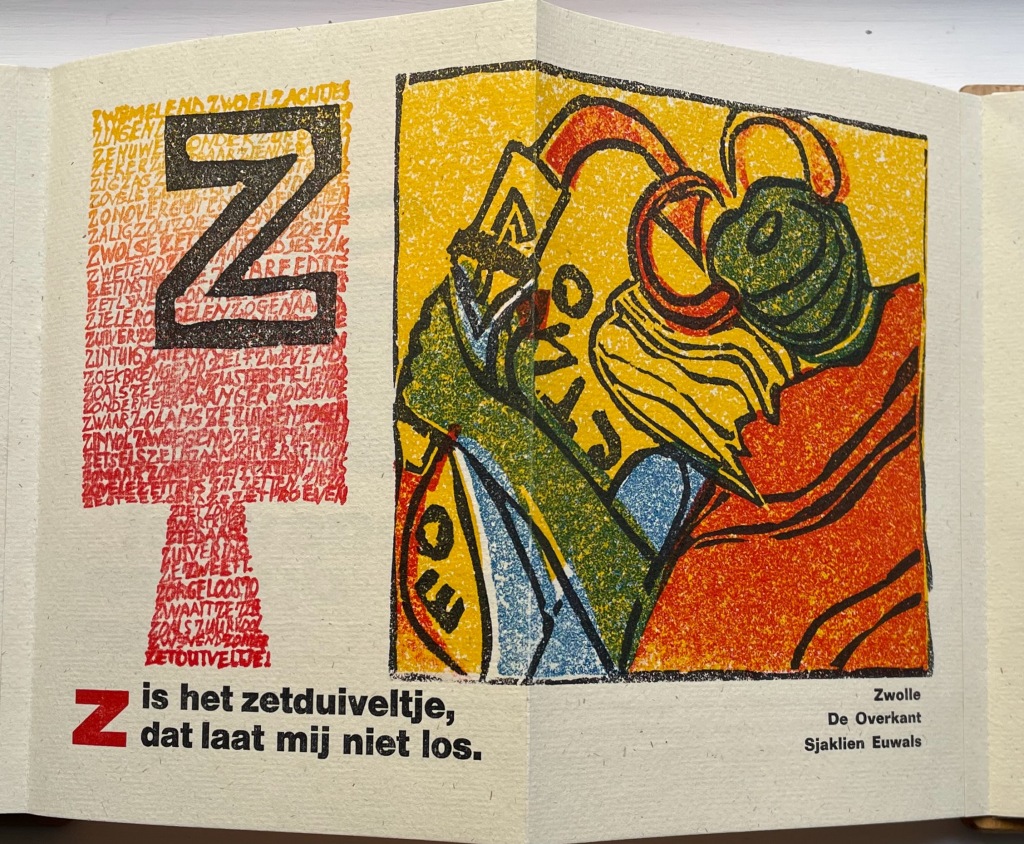

“Kees Baart, Dick Berendes, Henk Francino and Gerard Post van der Molen“. 2 November 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Margo Klass“. 9 July 2023. Books On Books Collection.

“Karen Roehr“. 26 December 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Connie Stricks“. 9 July 20223. Books On Books Collection.

“Ashley Thayer“. 26 December 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Andrew White Tuer“. 26 December 2022. Books On Books Collection.

Benjamin, Walter. 1969. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction“. Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, from the 1935 essay. New York: Schocken Books. Accessed 7 July 2023.

Bodleian Libraries. 7 July 2023. “Alphabets Alive! 19 July 2023 – 21 January 2024, Treasury, Weston Library“. Accessed 7 July 2023.

Chen, Min. 5 July 2023. “Digital Art Organization Rhizome’s New Blockchain Program Is an NFT-Dotted Journey Through the History of Generative Art“. Artnet News. Accessed 7 July 2023.

Clark, Mitchell. “NFTs, explained“. The Verge. Accessed 7 July 2023.