Abt, Jeffrey. The Book Made Art: A Selection of Contemporary artists’ Books Exhibited in Joseph Regenstein Library – University of Chicago, February Through April 1986, Exhibition catalog.

Antaya, Christine and Sloman, Paul. Book Art: Iconic Sculptures and Installations Made from Books. Gestalten (May 26, 2011). Documents current art, installation, and design created with and from books. “The fascinating range of examples in Book Art is eloquent proof that–despite or because of digital media’s inroads as sources of text information–the book’s legacy as an object and a carrier of ideas and communication is being expanded today in the creative realm.” Book jacket. See interview with Antaya and some of the artists here.

The Book as Instrument: Stephane Mallarmé, the Artist’s Book, and the Transformation of Print Culture – Anna Sigridur Arnar. An academic study of the literary and cultural seedbed of book art. “This is a highly ambitious, original account of Stéphane Mallarmé’s lifelong engagement with the book and the vast network of forces (cultural, aesthetic, political) that both informed this engagement and were transformed by it. Anna Sigrídur Arnar seamlessly brings together divergent areas of inquiry in order to support the idea that the book was and remains a site of numerous debates about democracy, public and private space, the uses of art and print, and the role of authors and readers. The Book as Instrument is elegantly written, in engaging and highly readable prose. Arnar succeeds in presenting and analyzing with remarkable lucidity ideas that many of us have learned to approach as difficult and thus nearly off-limits. This will be an important work of scholarship for a variety of disciplines.” (Willa Z. Silverman, Pennsylvania State University).

Art Is Books: Kunstenaarsboeken/Livres D’Artistes/Artist’s Books/Künstlerbücher – Guy Bleus. Catalog of a travelling exhibition in 1991. See also Artists’ Books on Tour edited by Kristina Pokorny-Nagel.

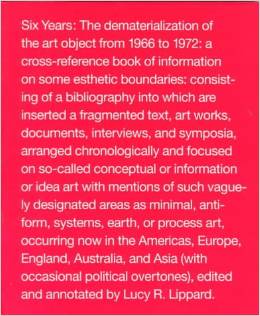

No Longer Innocent: Book Art In America 1960-1980 – Betty Bright. A history of an important period in book art. Like Drucker (below), Bright categorizes book art, places it within the movements of the period and profiles its individual and institutional supporters. Artbook review.

Artists’ Books: The Book As a Work of Art, 1963-1995– Stephen Bury. Explores the impact artists had on the format of the book.

A Century of Artists Books — Riva Castleman. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1994. NAL pressmark: AB.94.0020. A catalog of an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The selection tends toward the livre d’artiste but does address the impact of the digital shift on artists’ books.

Chapon, François. Le Peintre et le Livre: l’Age d’Or du Livre Illustré en France 1870–1970. Paris: Flammarion, 1987. NAL pressmark: 507.C.172

Courtney, Cathy. Speaking of Book Art: Interviews with British and American Book Artists. Los Altos Hills: Anderson-Lovelace, 1999. NAL pressmark: AB.99.0001

New Directions in Altered Books – Gabe Cyr. A book of projects and techniques by a book artist.

The Century of Artists Books – Johanna Drucker. “A folded fan, a set of blocks, words embedded in lucite: artists’ books are a singular form of imaginative expression. With the insight of the artist and the discernment of the art historian, Drucker details over 200 of these works, relating them to the variety of art movements of the last century and tracing their development in form and concept. This work, one of the first full-length studies available of artists’ books, provides both a critical analysis of the structures themselves and a basis for further reflection on the philosophical and conceptual roles they play. From codex to document, from performance to self-image, the world of artists’ books is made available to student and teacher, collector and connoisseur. A useful work for all art collections, both public and academic.”Paula Frosch, Metropolitan Museum of Art Library, Library Journal.

#5168 Altered Book – Special Effects (Design Originals) – Laurie Goodson. One of a series of booklets on book-alteration techniques. Other authors include Beth Cote and Cindy Pestka.

Altered Books, Collaborative Journals, and Other Adventures in Bookmaking – Holly Harrison. A showcase of book art with an emphasis on multi-artist collaborations.

The Cutting Edge Of Reading: Artists’ Books – Judd Hubert and Renee Hubert. Published in 1999, a close examination of 40 examples of book art. Illustrated.

Books Unbound – Michael Jacobs. A book of projects by a book artist.

Johnson, Robert Flynn. Artists Books in the Modern Era 1870–2000: the Reva and David Logan Collection of Illustrated Books. London: Thames & Hudson, 2002. NAL pressmark: AB.2001.0002

Artists’ Books: A Critical Survey Of The Literature – Stefan Klima. A 1998 monograph summarizing the debates over the artists’ book.

Book + Art: Handcrafting Artists’ Books – Dorothy Simpson Krause. A book of projects by a book artist; covers mixed-media techniques as well as bookbinding.

The Penland Book of Handmade Books – Jane LaFerla (Editor); Alice Gunter (Editor); Lark Books Staff. Tutorials, inspiration and reflective essays by book artists.

500 Handmade Books – Steve Miller. A highly illustrated, wide-ranging coffee table book.

Artists’ Books on Tour – Kathrin Pokorny-Nagel. Catalog of a travelling exhibition organized and sponsored by MAK (Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna), MGLC (Llubljana’s International Centre of Graphic Arts) and UPM (Museum of Decorative Arts) in 2011.

1,000 Artists’ Books: Exploring the Book as Art – Peter and Donna Thomas, Sandra Salamony. External and internal views of works, descriptions at the end of the book.

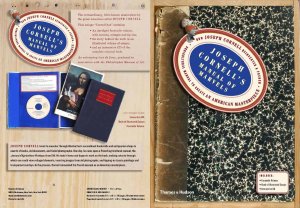

Joseph Cornell’s Manual of Marvels: How Joseph Cornell reinvented a French agricultural manual to create an American masterpiece – Dickran Tashjian and Analisa Leppanen-Guerra (editors). A part-facsimile, part-DVD, part-boxed-presentation that gives some idea of the artwork by Joseph Cornell held in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The artwork is Cornell’s alteration of the Journal d’Agriculture Practique (Volume 21, 1911), a handbook of advice for farmers.

Playing with Books: The Art of Upcycling, Deconstructing, and Reimagining the Book – Jason Thompson. Techniques-driven; covers bookbinding, woodworking, paper crafting, origami, and textile and decorative arts techniques.

Masters: Book Arts: Major Works by Leading Artists – Eileen Wallace. Illustrated selection of work from 43 master book artists with brief comments from the artists about their work, careers, and philosophies.

The Book As Art – Krystyna Wasserman; Audrey Niffenegger (Text by); Johanna Drucker (Text by). An illustrated volume covering over 100 artists books held in the permanent collection of the Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

Book Art: Creative Ideas to Transform Your Books, Decorations, Stationary, Display Scenes and More – Claire Youngs. A crafts book of 35 projects.

0.000000

0.000000