“What happens when we’re not watching the clocks? A short piece where ordered Newtonian time gives out and something a bit more interesting takes over instead.”

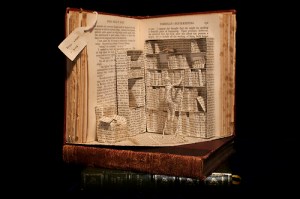

Based in Bristol, Andrew Eason creates and teaches book art. One of his more interesting bookworks is Clock Watching, but he is more than a book artist watching the clock or posterity. Consider these concluding paragraphs to “The Critical Commonwealth,” his essay contributed to the 2010-11 Book Artists’ Yearbook.

If we are to say that artists’ books count in contemporary art practice, we have to connect those circuits up with the wider critical discussion. Books have made this difficult, because in themselves, as objects, they harbour an insular perfection of their own. They have a persuasive individual completeness that only a wider context can begin to describe and elucidate. This security is part of their appeal, of course. But it also trips us up as we try to write about them, as the temptation is to treat every book as a world in itself, separate from any other and from the world outside. Walter Benjamin, writing of the early books of his childhood, confides, ‘whereas now content, theme and subject-matter are extraneous to the book, earlier they were solely and entirely in it’.

We should move towards a perception of practice, tactics and desires extraneous to the insufficiently-permeable identity of ‘artists books’. Like Benjamin, we should allow our perception of what is inside books to be informed by that which is outside them. The critical commonwealth that artists’ books belong to is none other than that of contemporary art practice. This realisation reframes the question of how to discover the relevance of artists’ books. It has nothing to do with their definition, or categorisation, and everything to do with what they say and what they make possible. They’re art.

The digital revolution is one of those extraneities that Eason and other book artists must have in mind. As is evident from the link, his Clock Watching is a pdf flipbook and seems to be viewable only on his website — a book in a browser. Any critique of the work would take into account the artist’s accommodation for non-Flash browsers and his choices of the application’s functionalities (automated page-turning, click to turn, click and drag to turn, thumb-nail presentation, print not allowed, download not allowed, etc.). On the iPad, the ability to zoom in to appreciate the chalk-drawn figures over the tinted collage of landscape foreground and background surpasses that of the cursor-bound MacBook Pro (circa 2009), but the work is dated 2006, and one would have hoped for greater visual control to pore over the tinted rocks and roots in the twilight scenes. But attention to technical extraneities are not the only ones Benjamin or Eason expect of the artist and viewer.

The work poses its question of measured time in words and then in images that suggest the vegetal, cultural and mortal passage of time. The strangely tinted foliage is moving through its seasons. The chalked characters are from different times and suggest Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the influence of other literary and artistic forebearers. But does Clock Watching succeed in bringing what is outside the clock and outside its medium — book, book-in-browser, book art — within itself? Time, as they say, …

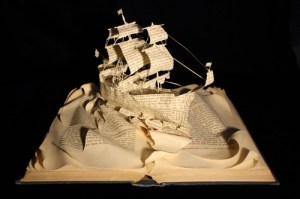

In addition to making his own bookworks and inviting us onto the grounds of the critical commonwealth, Andrew Eason has posted a tunnel book: The Thames Tunnel. Be sure to hover over the holes in the cover and click on the dropdown “Look through.”

Here is the collection citation should you happen to be near the Brunel Collection in Bristol and wish to make an appointment to see the work:

Repository University of Bristol Library Special Collections

Level Collection Ref No DM327

Title Illustrated booklet advertising the Thames Tunnel

Date 1827

Extent 1 item

Description ‘Sketches and Memoranda of the works for the Tunnel under the Thames from Rotherhithe to Wapping [London]: published and sold at the Tunnel Works, Rotherhithe, and by Harvey and Darton, 55 Gracechurch Street, 1827’.

26 p., [13] leaves of plates (4 folded). Copy available in the Eyles Collection, TA820.L6 SKE.