by John Collier

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us…. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

– On the Origin of Species, 1869, the final paragraph.

In disparate “entangled banks” and micro-climates around the world, book artists and Charles Darwin have evolved a symbiotic relationship. By date and place, here are some bookmarks on that evolution.

1995, Washington, D.C., USA

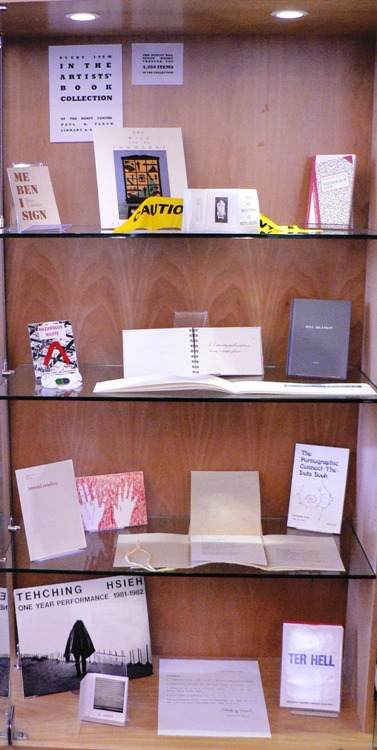

Carol Barton and Diane Shaw organized the exhibition “Science and the Artist’s Book” for the Smithsonian Institution Libraries and the Washington Project for the Arts. Barton and Shaw invited book artists to respond to works in the Heralds of Science collection in the Smithsonian’s Dibner Library. Among twenty-one other pairings, George Gessert was invited to respond to Charles Robert Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, London, 1859.

Gessert’s response was Natural Selection (1994), an artist’s book consisting of computer-printed handwriting and Cibachrome prints of the results of Gessert’s own experiments in hybridizing irises. Citing Darwin’s description of the breeding of pigeons for their ornamental characteristics, Gessert contends “that Darwin also recognized aesthetics as an evolutionary factor”. Since the 1980s, Gessert’s work and writings have focused on the way human aesthetics can affect evolution and the aesthetic, ethical and social implications. His work and that of artists/theorists such as Suzanne Anker, Eduardo Kac, Marta De Menezes, the Harrisons and Sonya Rapoport have constituted the bio art and eco art movements. A collection of his essays appeared as Green Light: Toward an Art of Evolution in the Leonardo Book Series, published by The MIT Press in 2010.

2004, Manchester, UK

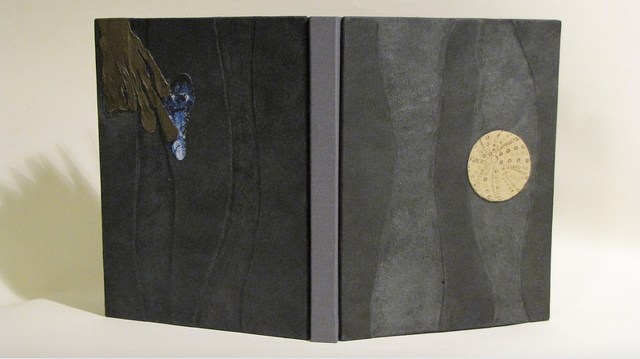

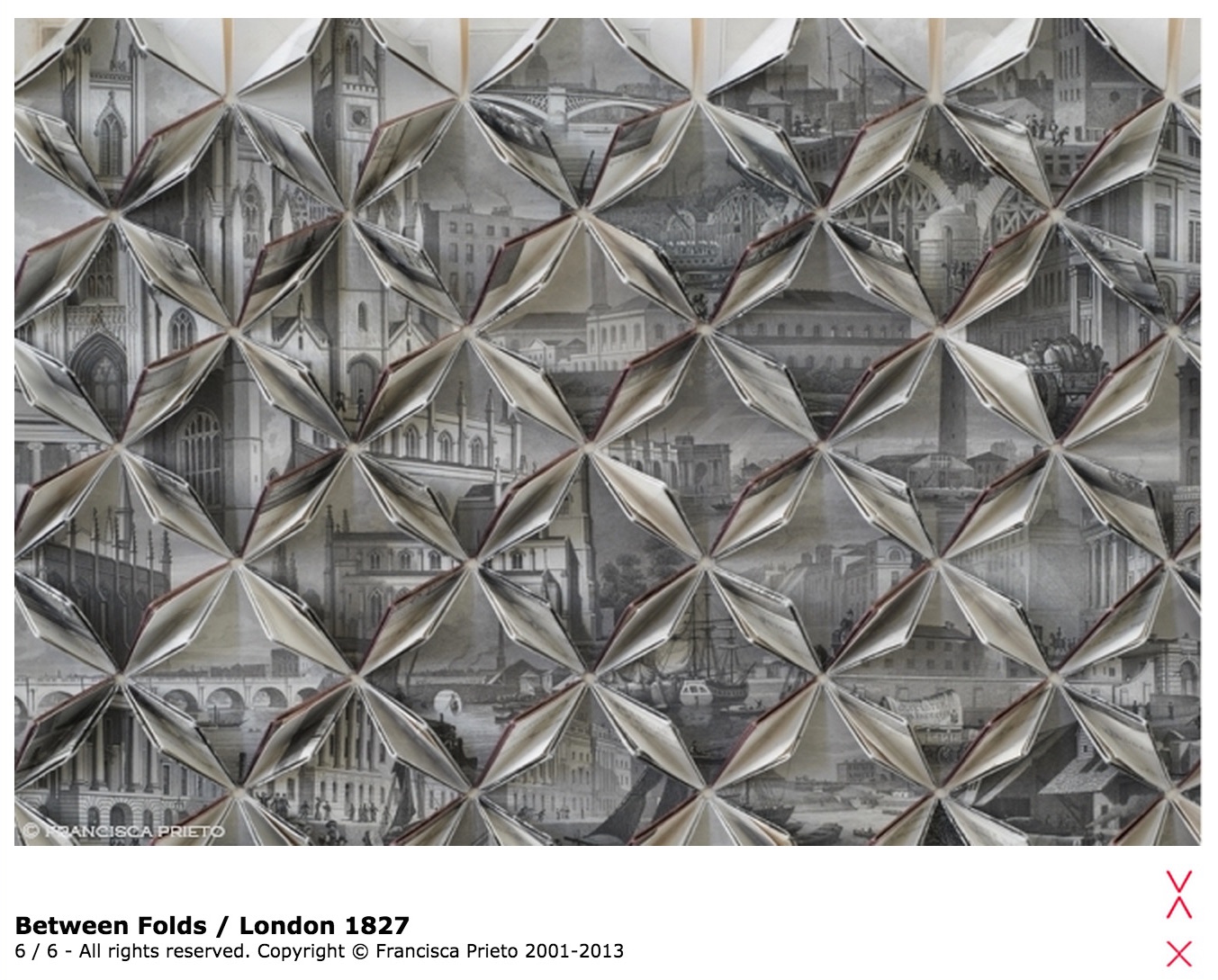

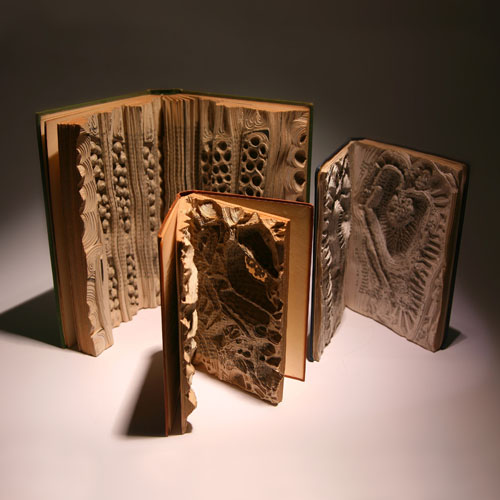

Evolution Triptych (2004)

Part 1 – 10 x 7.5 x 1, Part 2 – 12 x 9 x 2, Part 3 – 8.5 x 6.5 x 1

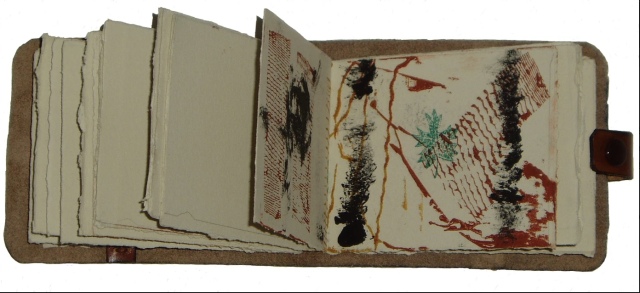

Inspired by Darwin’s The Descent of Man, Part I, and cell structures in biology texts, Emma Lloyd‘s Evolution Triptych sparks thoughts of fossils, woodcarved altarpieces or the tooled cover of the St Cuthbert Gospel, the code of life embedded in DNA structure and the code of information embedded in the codex.

Porto, Portugal

British Library

The artistic technique here – carving the book as artifact – is prevalent in book art; see the work of Doug Beube, Brian Dettmer and Guy Laramée, for example. Lloyd’s treatment of the Darwin volume is the only one of its type in this collection of bookmarks. Given the influence of On the Origin of Species, though, it would be unusual if other “book surgeons” have not been similarly inspired by it.

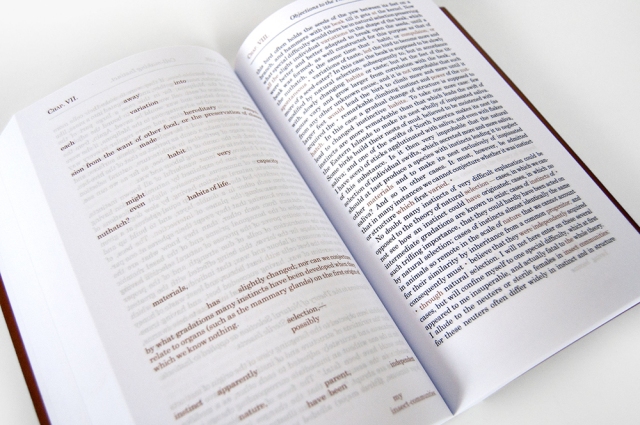

2009, London, UK

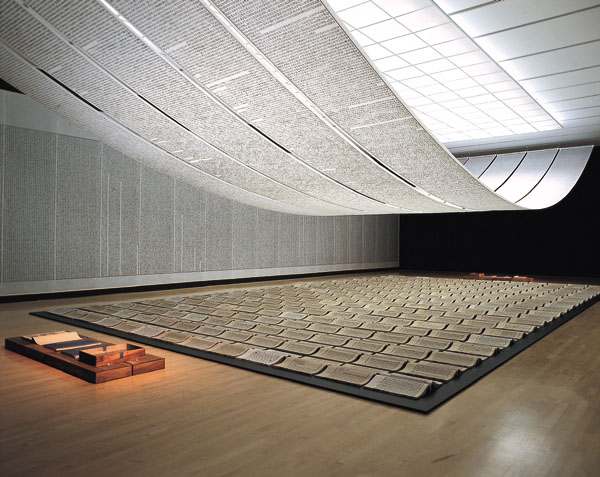

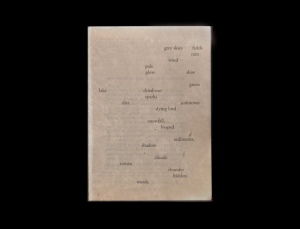

Storyteller and book artist Sam Winston set about categorizing the words in On the Origin of Species and poet Ruth Padel’s Darwin, A Life in Poems (Chatto & Windus, 2009). He sorted them by nouns, verbs, adjectives and “other”. As Winston puts it, he “wanted to present a visual map of how a scientist and a poet use language – a look at how much each author used real world names (Nouns) and more abstract terminology (Verb, Adjective and Other) in their writings.”

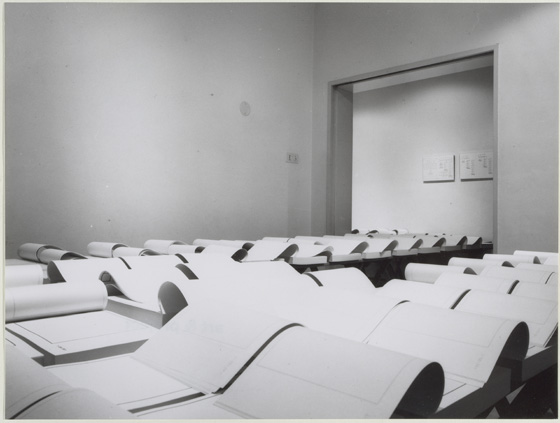

To do that, he categorized the 153,535 words in On the Origin – a dot with a 4H pencil for the 50,567 words categorized as “Other”, a 2H pencil for the 38,266 categorized as “Noun”, an HB pencil for the 26,435 categorized as “Verb” and a 4B pencil for the 38,266 categorized as “Adjective”. The result – Darwin, a series of visual “frequency poems” on display at Le Gun Studio in London – is a book altered through the DNA-like pattern of its own words into a completely “other” scroll and into a topographical map of itself – guided by the artist’s hand and mind.

Darwin (2009)

Le Gun Studio, 19 Warburton Road, London, E8 3RT, UK

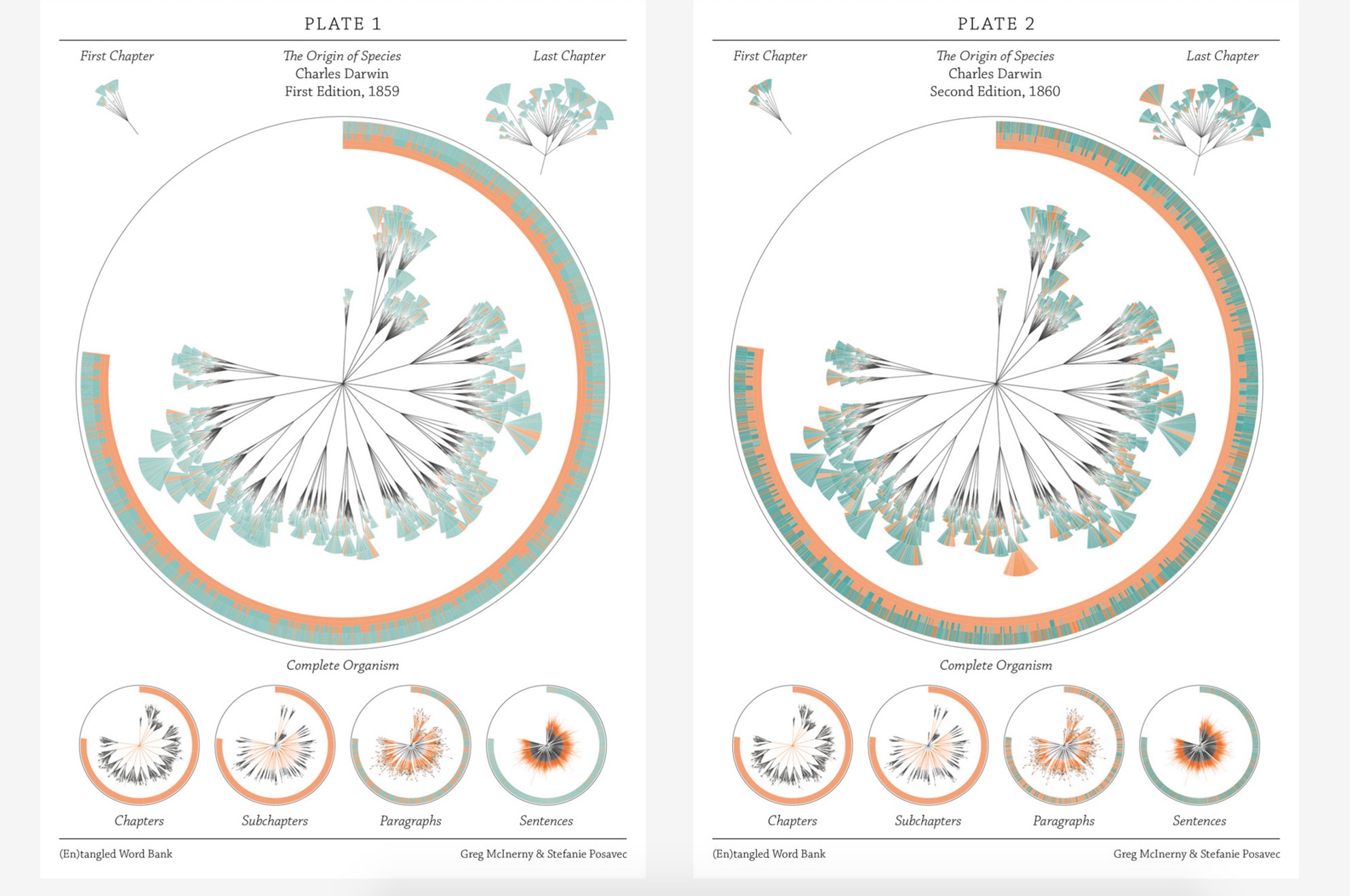

In the same sesquicentennial year, in the same city, Stefanie Posavec collaborated with Greg McInerny to issue (En)tangled Word Bank, a series of diagrams, each representing an edition of On the Origin of Species, and the work’s title alluding to Darwin’s “entangled bank” passage presented above. The pressed-dandelion-shaped chapters and subchapters are divided into paragraph ‘leaves’ with wedge-shaped ‘leaflets’ representing their sentences.

The sentences forming the ‘leaflets’ of the organism are of orange, senescent tones when they will be deleted in following editions. The green, growth tones are applied to those sentences that have life in the following edition. The tone of each colour is determined by its age, in editions, to that point. Through these differences in colouration the simplicity in structure in the early stages of the organism’s life develops into a complex form, showing when the structures developed to its changing environment. Around the organisms the textual code is provided, showing the changes in the size of the organism, and where the senescence and growth is derived in that code. A series of re-arrangements of the organism focus on changes at each level of organisation.

This is “structural infographic” as art.

(En)tangled Word Bank (2009)

2009, Boston, MA, USA

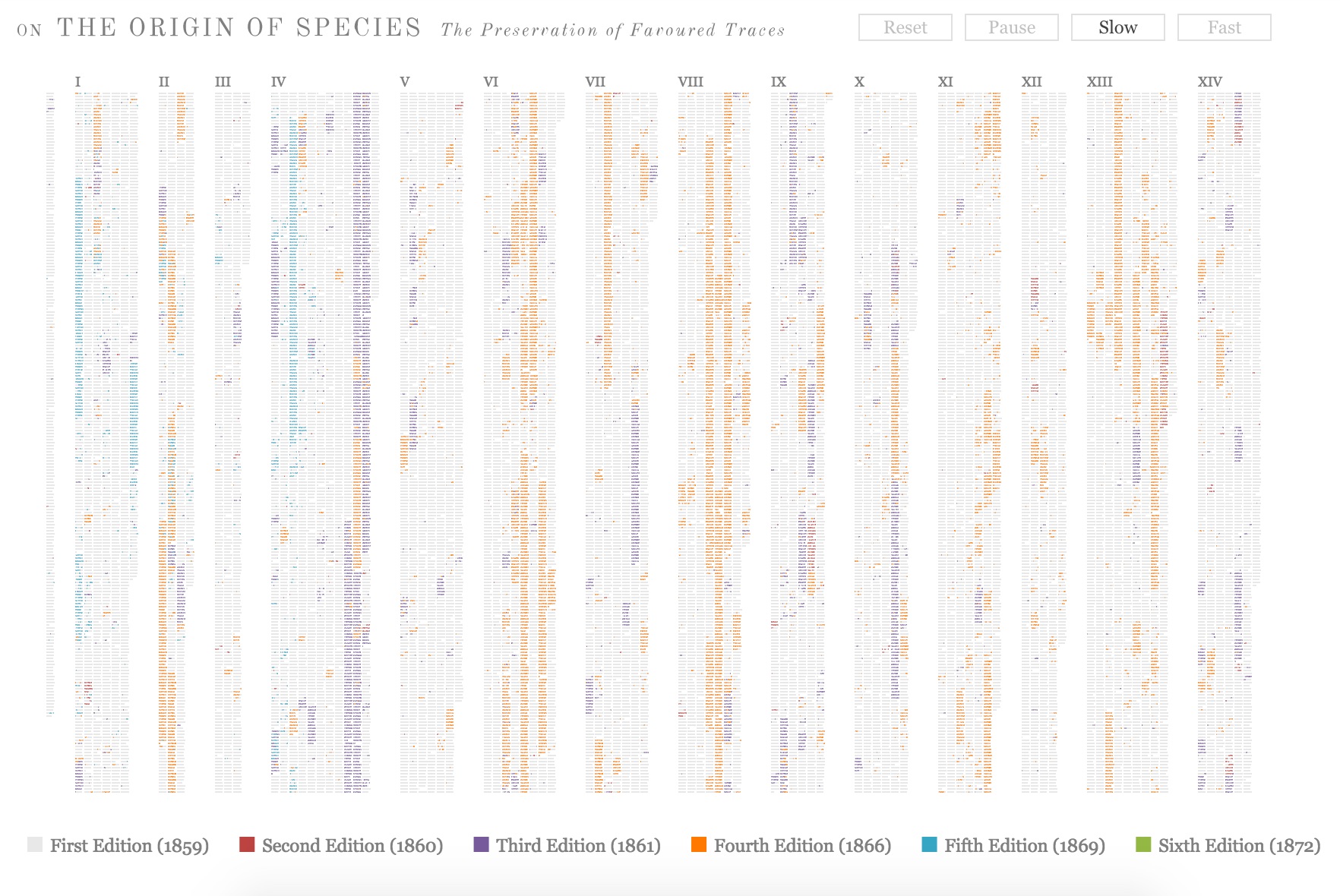

Across the Atlantic, Ben Fry, author of Visualizing Data (O’Reilly, 2007), created a similar work of art called The Preservation of Favoured Traces. Fry color-coded each word of Darwin’s final text by the edition in which it first appeared and used the data to build an interactive display at fathom.com demonstrating the changes at the macro level and word-by-word. Fry went on to produce a poster version and print-on-demand book version.

The Preservation of Favoured Traces (2009)

2009, Vancouver, Canada

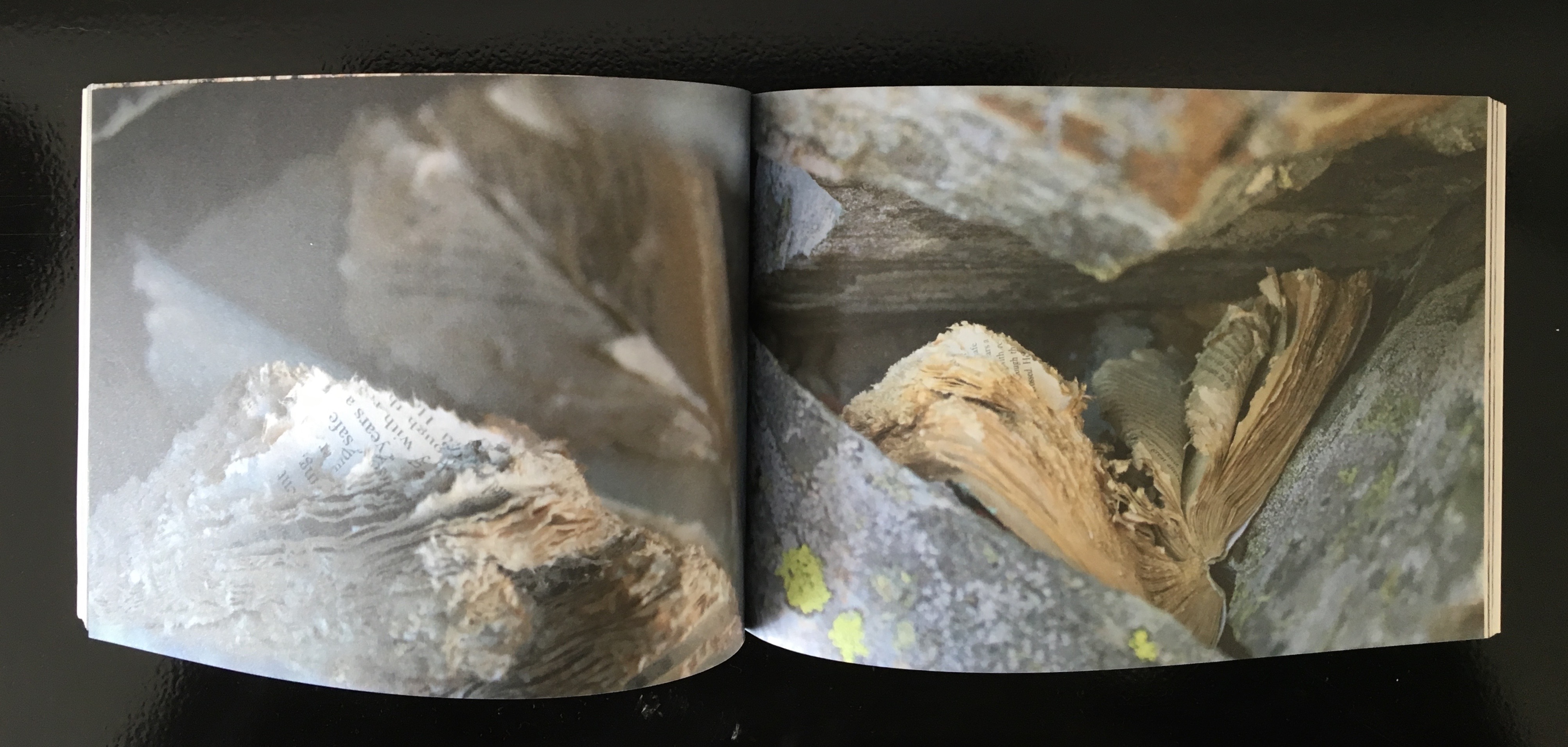

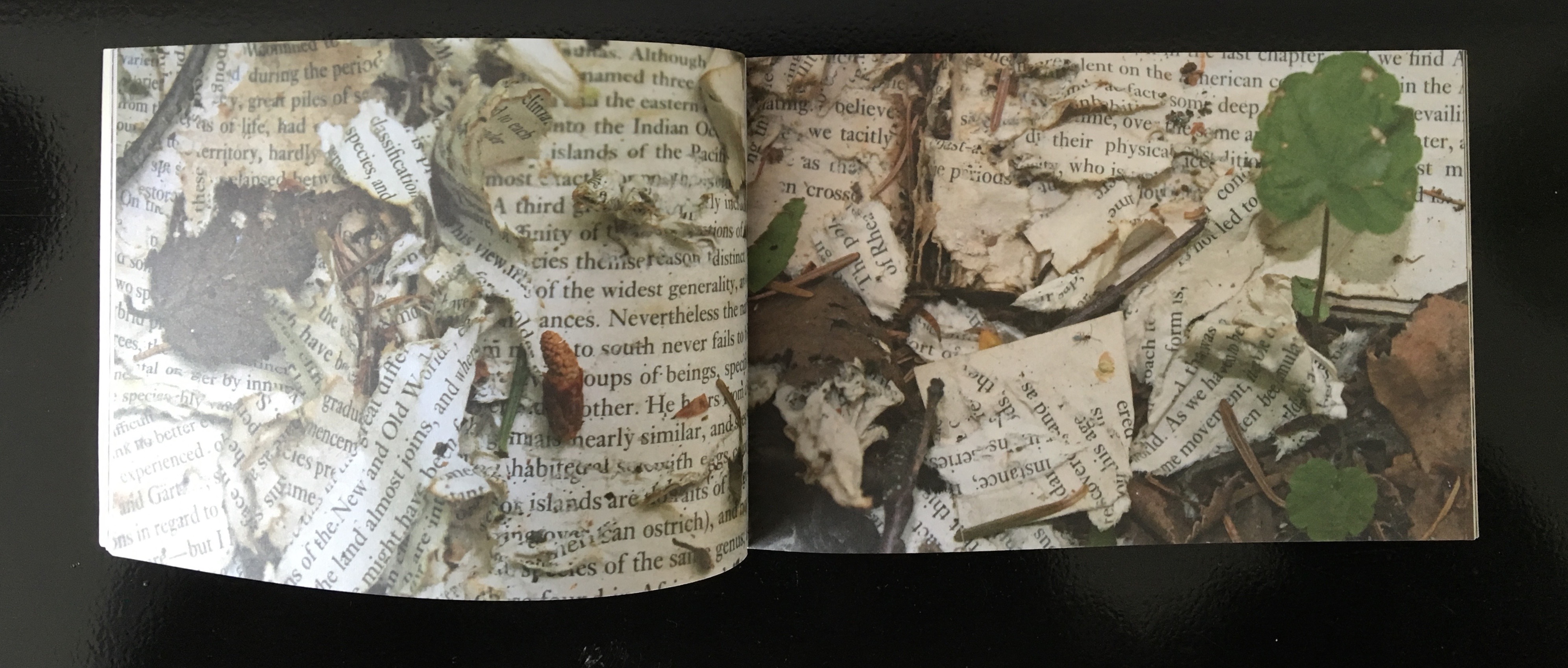

Three thousand miles away that summer, Canadian poets Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott placed multiple copies of On the Origin of Species in various outdoor locations “not … to put the natural into the text, [but] … to put the text out into the natural world and see what happens to it” (p. 2). After a year, Collis and Scott photographed the results in situ and collected and used the some of the still decipherable words as found text for their volume Decomp (Coach House Press, 2013).

Decomp (2013)

Decomp (2013)

This blend of the technique of found text and artistic collaboration with nature harks back to Marcel Duchamp’s 1919 Readymade Malheureux , Finlay Taylor’s East Dulwich Dictionary (2007) and M.L. Van Nice’s Feast is in the Belly of the Beholder (2010) among many others.

2009, Phoenix, AZ, USA

Former science teacher and now botanical artist and bookmaker, Kelly Houle embarked on a 10-year plan to create an illuminated and scribed copy of the first edition of On the Origin. Where medieval scribes and rubricators had abbots to preside over them and their book art, Houle has University of Chicago Professor Emeritus Jerry A. Coyne and several other academics. As she notes about her process, the past techniques have also yielded to present concerns:

The Illuminated Origin (2009 – )

Watercolor, gouache, interference watercolor, gold foil, shell gold

on Fabriano Artistico, 22 x 30 inches

Today many artists still practice the tradition of illumination using medieval and renaissance-era materials and techniques. While many of these have stood the test of time, there are more earth-friendly materials than those used in the past….

Courtesy of the artist

The Illuminated Origin of Species will be written on hot-pressed Fabriano Artistico paper made in Italy. It is the best paper in the world for both calligraphy and botanical art. These are extremely smooth, beautiful, and durable papers. They are chlorine-free, acid-free, and 100% cotton. No animal by-products are used in the sizing. Combined with Winsor and Newton watercolors and gouache, this paper will be perfect for the demands of The Illuminated Origin.

Courtesy of the artist

To mimic the play of light on various shiny and iridescent surfaces in nature, I am using 23k gold foil, shell gold, and interference watercolors, which contain small flecks of mica to produce an iridescent effect. These metals will distinguish The Illuminated Origin as a truly “illuminated” manuscript. — Kelly M. Houle, “The Making of a Modern Illuminated Manuscript“

Houle aims to complete her work in 2019, On the Origin‘s 160th anniversary.

2009, Farnham, Surrey, UK

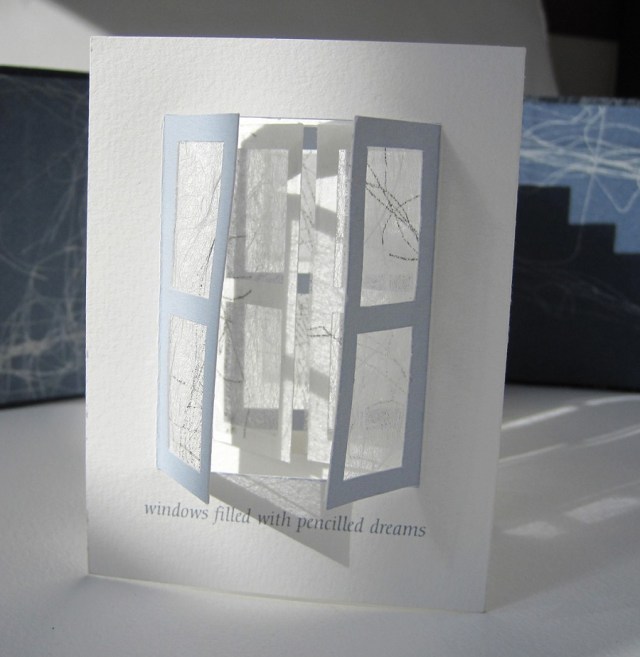

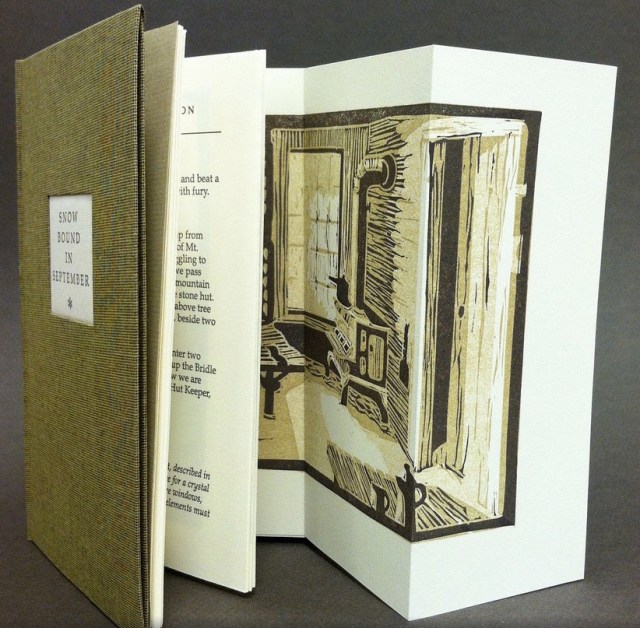

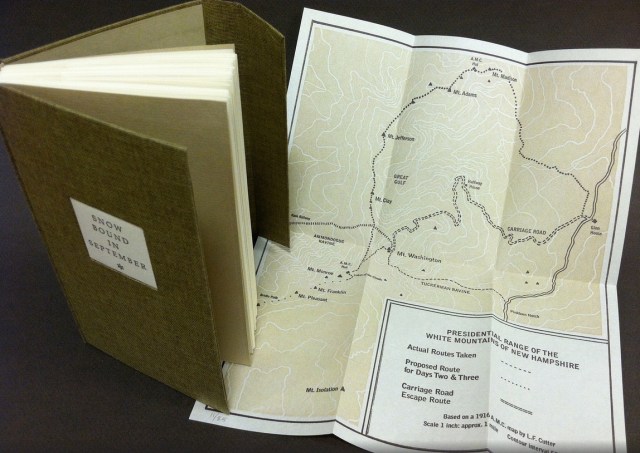

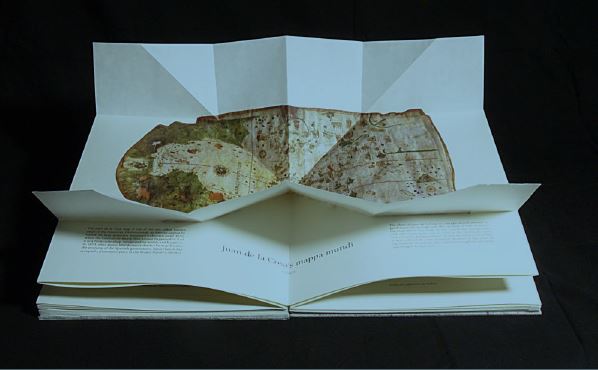

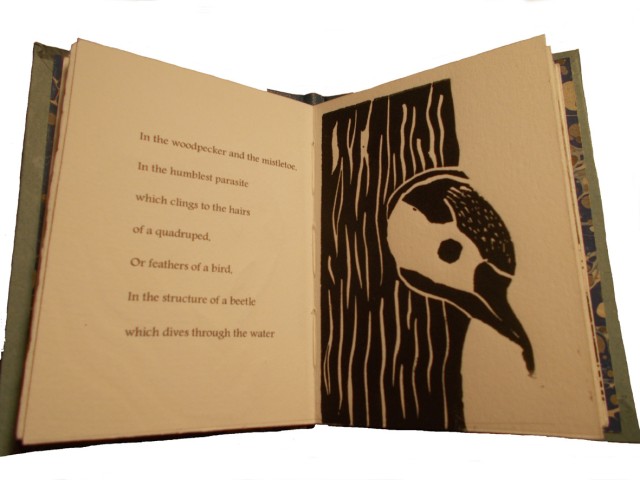

Between its hardback covers lined in marbled papers, Angela Thames’ Darwin’s Poetic Words has distilled the often liturgical, poetic passages of On the Origin of Species.

Darwin’s Poetic Words (2009)

Hardbound, 12 pages, 12 x 8 cm, 8 linocuts, Somerset paper

Between 2009 and 2013, Thames created four more artist’s books besides Darwin’s Poetic Words, based on excerpts from On the Origin of Species. In this focus and technique, Thames takes and interprets portions rather than the whole of the source as do Houle, Collis and Scott, Fry, McInerny and Posavec, Winston, and Lloyd in their differing ways.

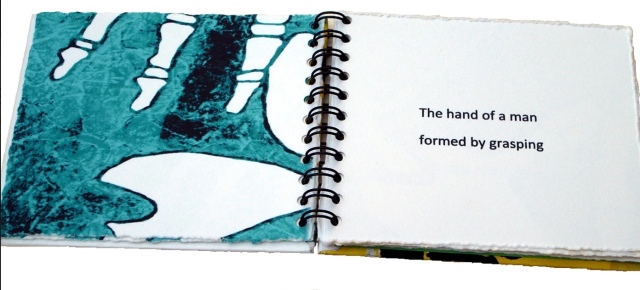

Evident Evolution (2009-13)

Collagraph images of bone structures and text, 8 pages, Silkscreen covers, Spiral bound edition

A Grain in the Balance (2009-13)

Collagraph images with rubber-stamped text, 8x10cm, 15 pages, Somerset beige paper

Poor Man (2009-13)

Folded card with pop up flower, Words spoken by his gardener,

Silkscreen, wood-stamped text, Open edition

Poor Man (2009-13) is the only exhibit in this survey that demonstrates the pop-up technique in book artistry, but as evolutionary biology and fossil-hunting have shown, who knows what undiscovered forms are out there.

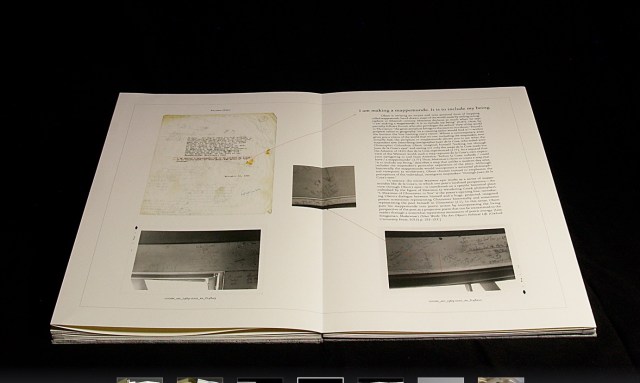

2012, New York, NY, USA

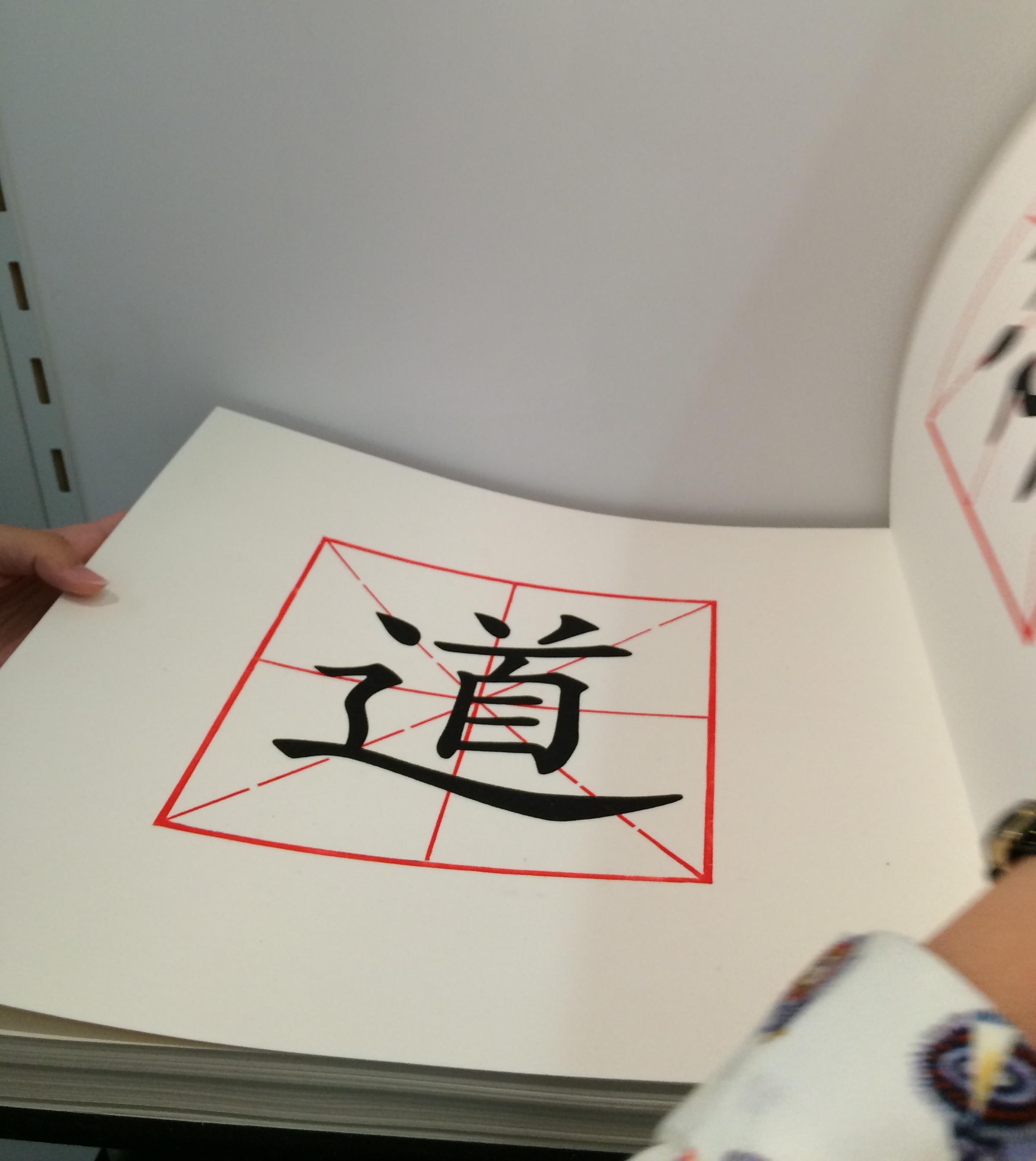

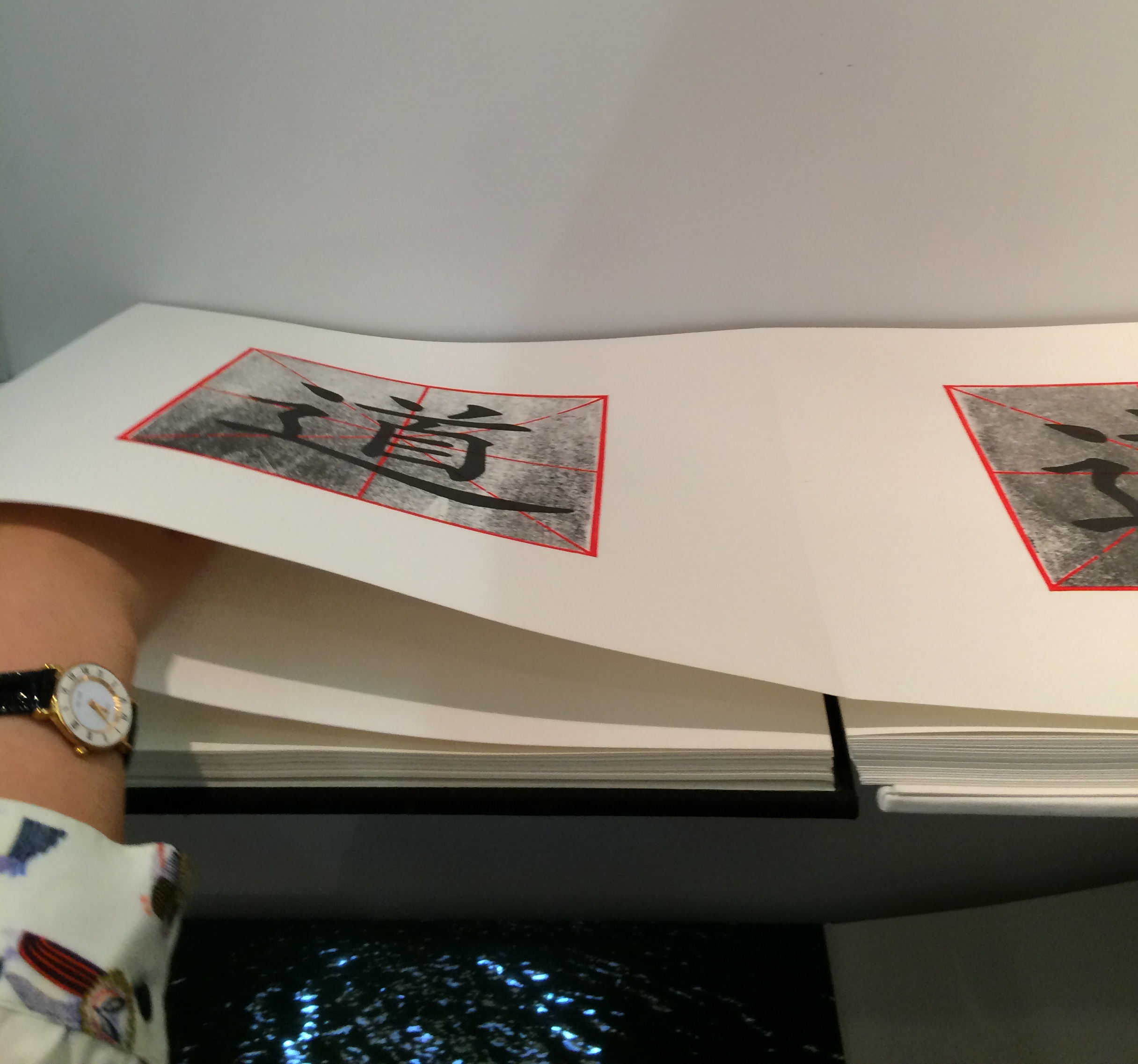

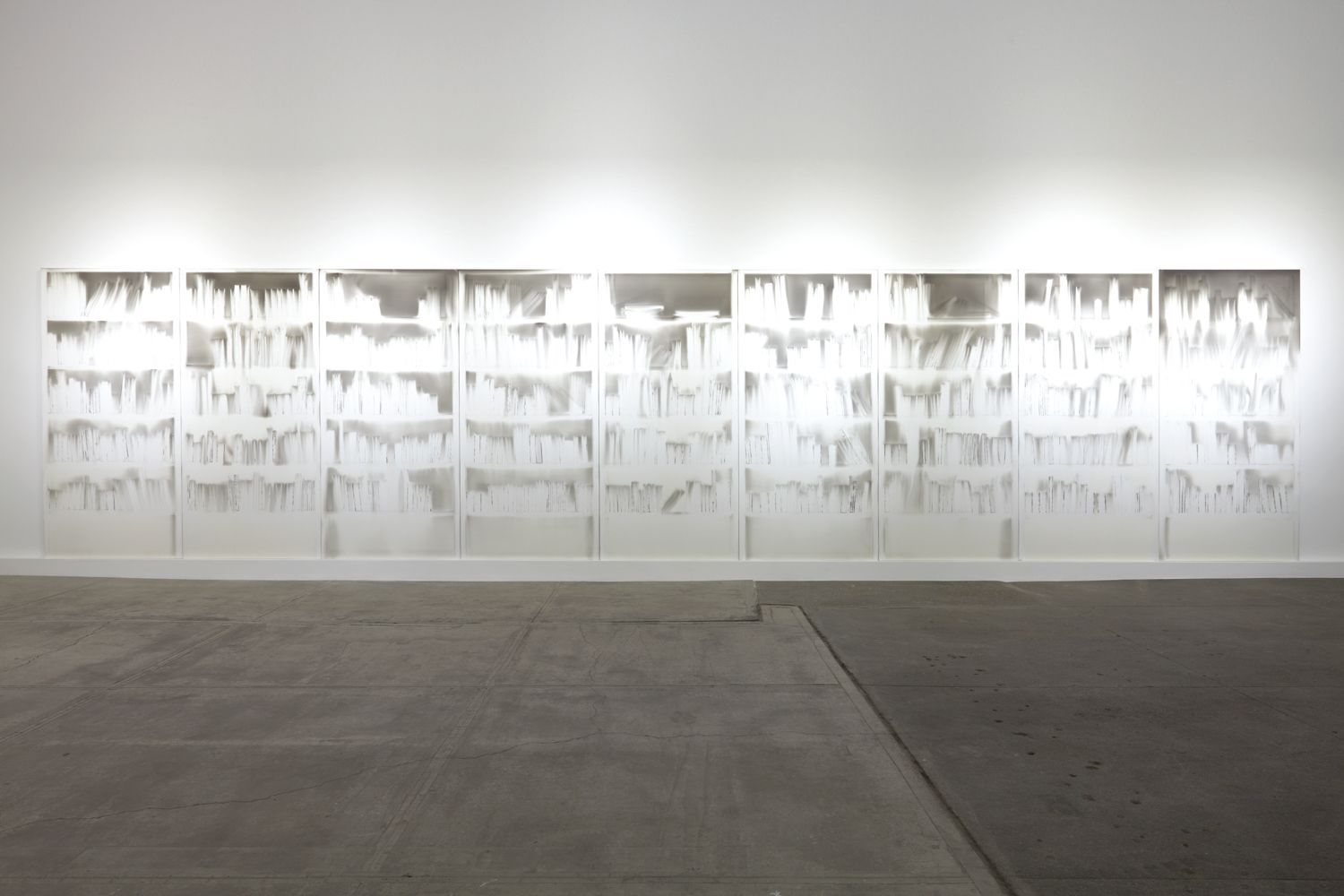

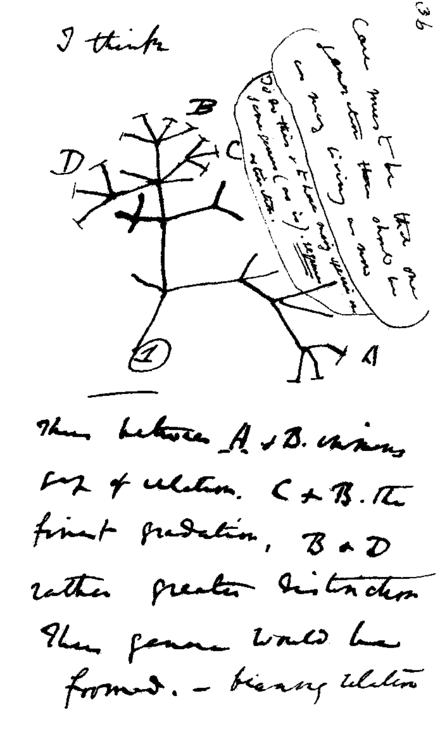

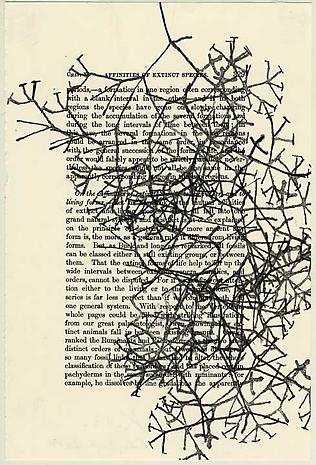

Following in their tradition since 1984, Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (“Kids of Survival”) seized on Darwin’s “Tree of Life” diagram

and “jammed” to produce a series of paintings and preliminary works in ink and watercolor on pages of the book to create ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES (after Darwin). Eighteen students, aged 13 to 16, worked with Rollins on the preliminary studies, one of which appears below, that preceded the 2013 exhibition of paintings at the Lehmann Maupin Gallery.

Studies for ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES (after Darwin) (2014)

Ink and watercolor on book page, 22.9 x 15.2 cm

Photo credit: Lehmann Maupin Gallery

The large-scale paintings consist of almost all of the 360 pages of On the Origin fixed to canvas and ink-stamped over and over with the “Tree of Life” image, which had been cut into 60 handstamps. Rollins described the concept of the works in an interview for Brooklyn Rail:

The whole book is 360 pages but we don’t ever want to be literal so it’s not all of the pages. They’re there to inspire. It’s like an opera. The libretto inspires the music. You can watch an opera in a language you don’t know, without reading. It’s the same with our work. It’s about a visual correspondence with the text. The work is not about something. That’s why you can’t get hung up on interpretation. That’s a big issue, especially with so much politically engaged art. We want to create a situation, learning machines, so everyone is learning in the process of making and then hopefully the audience will be inspired too. Maybe they will pick up Darwin or continue with the idea. These are catalysts for action.

In a video interview with ArtNet, Rollins also refers to the K.O.S. jamming process -reading aloud from the book in a studio setting, discussing it with students and seeking inspiration from the text – not as a school lesson or classroom exercise but as a kind of séance, an assertion that touches the essence of “reverse ekphrasis” in book art. Rather than the literary work or book capturing the spirit of a work of art, the work of art captures the spirit of the book.

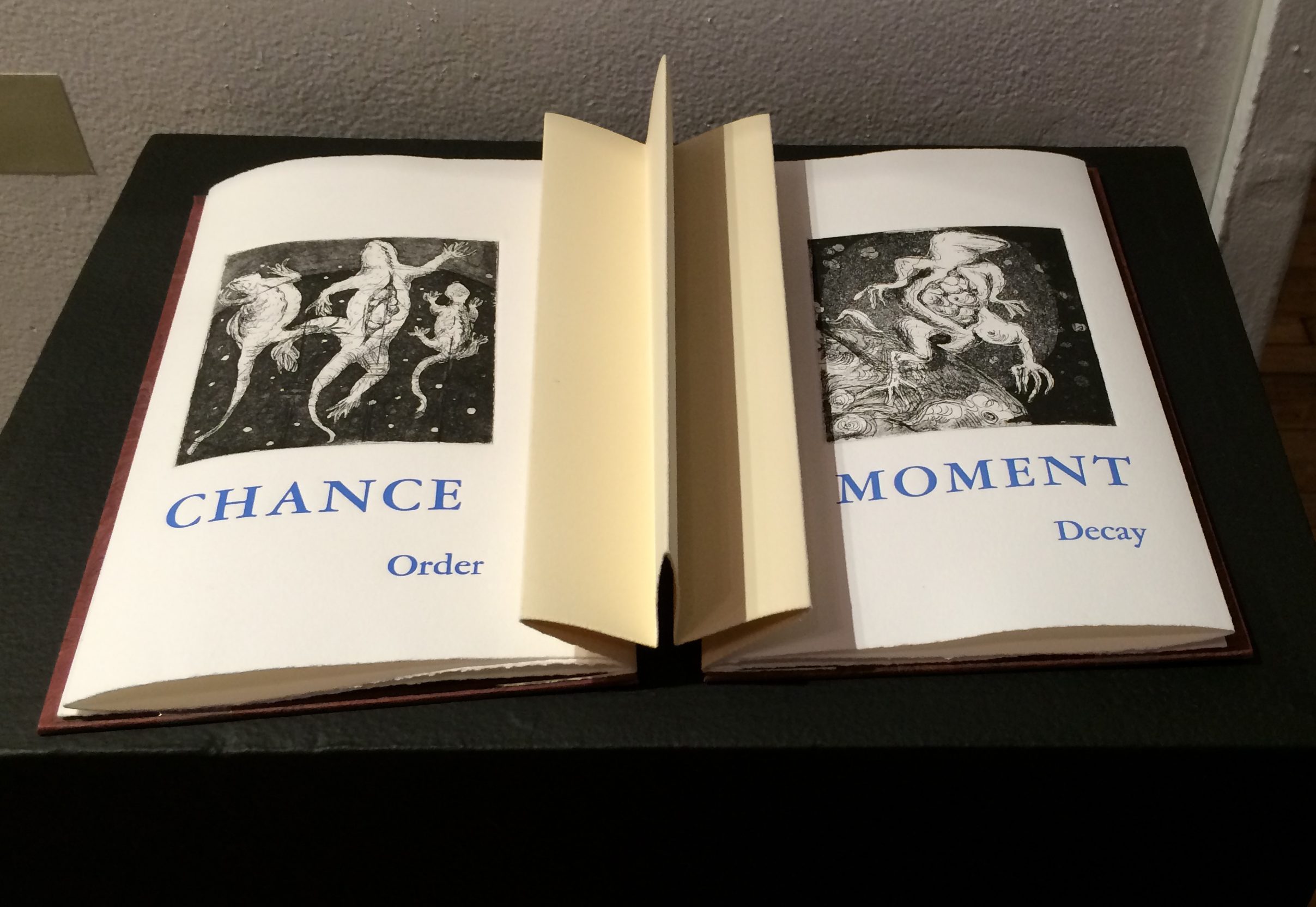

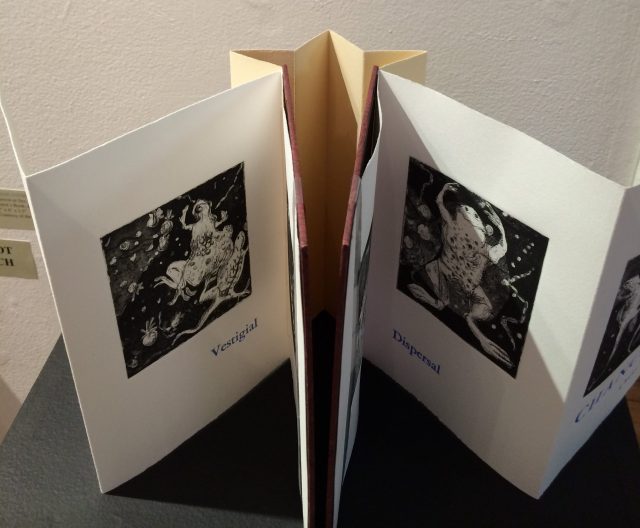

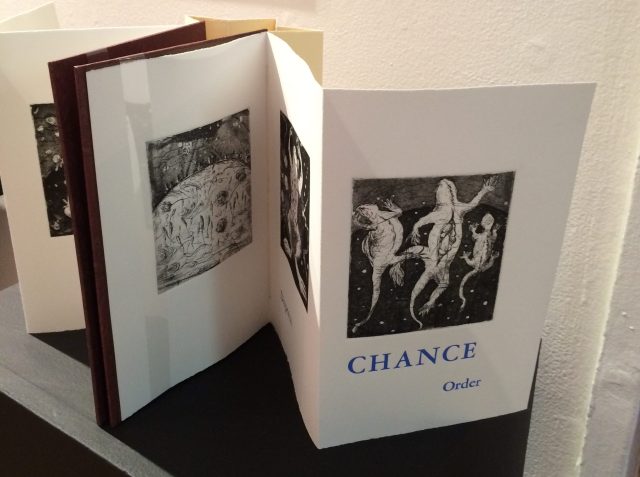

2013/14, Oxford, OH, USA

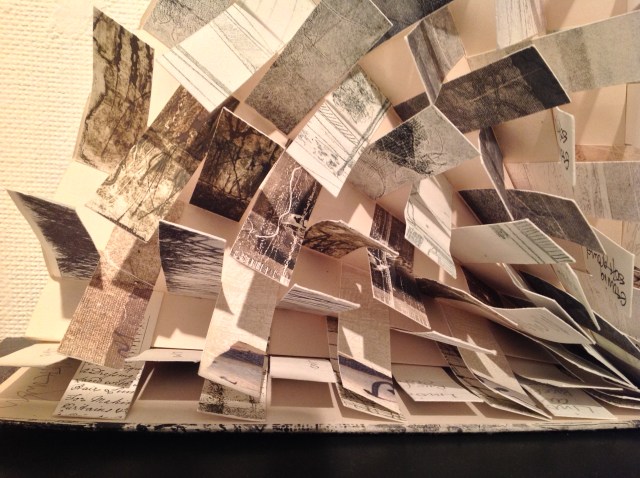

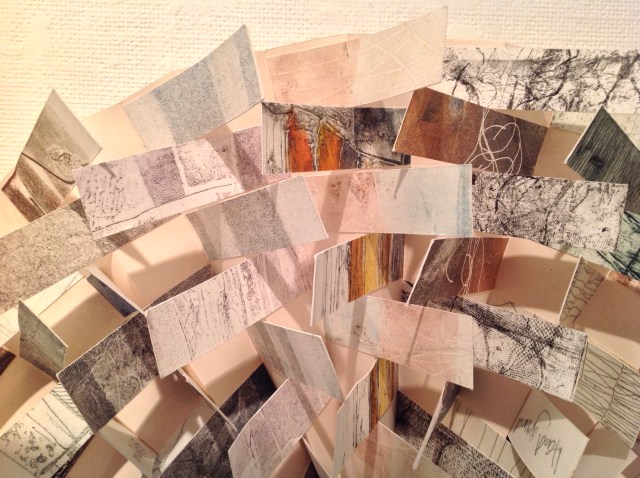

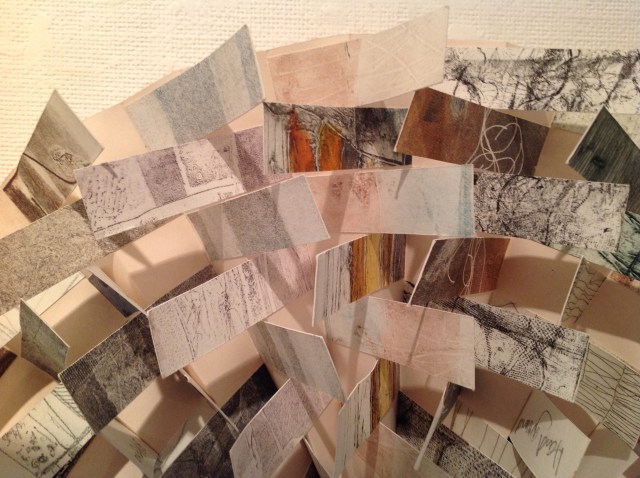

At the University of Puget Sound (2013) and Center for Book Art in New York (2014), Diane Stemper exhibited her Darwin-inspired book art that explores “the intersection between the natural world, daily living, science and the collective and individual experience of landscape”.

Universal Sample (2014)

Edition of 4, Intaglio and letterpress on Arches

Universal Sample (2014)

Edition of 4, Intaglio and letterpress on Arches

Universal Sample (2014)

Edition of 4, Intaglio and letterpress on Arches

Hand bound, printed and produced in her Plat 21 Studio, in Oxford, her Galapagos Map (2013), Darwin’s Atlantic Sea (2014) and Universal Sample (2014), these works have an eerie physical presence. At the Center for Book Art, I have seen and, with the kind permission of Alex Campos, the curator there, touched the works. The intaglio printing and richly textured creamy paper still communicate themselves even across the digital divide.

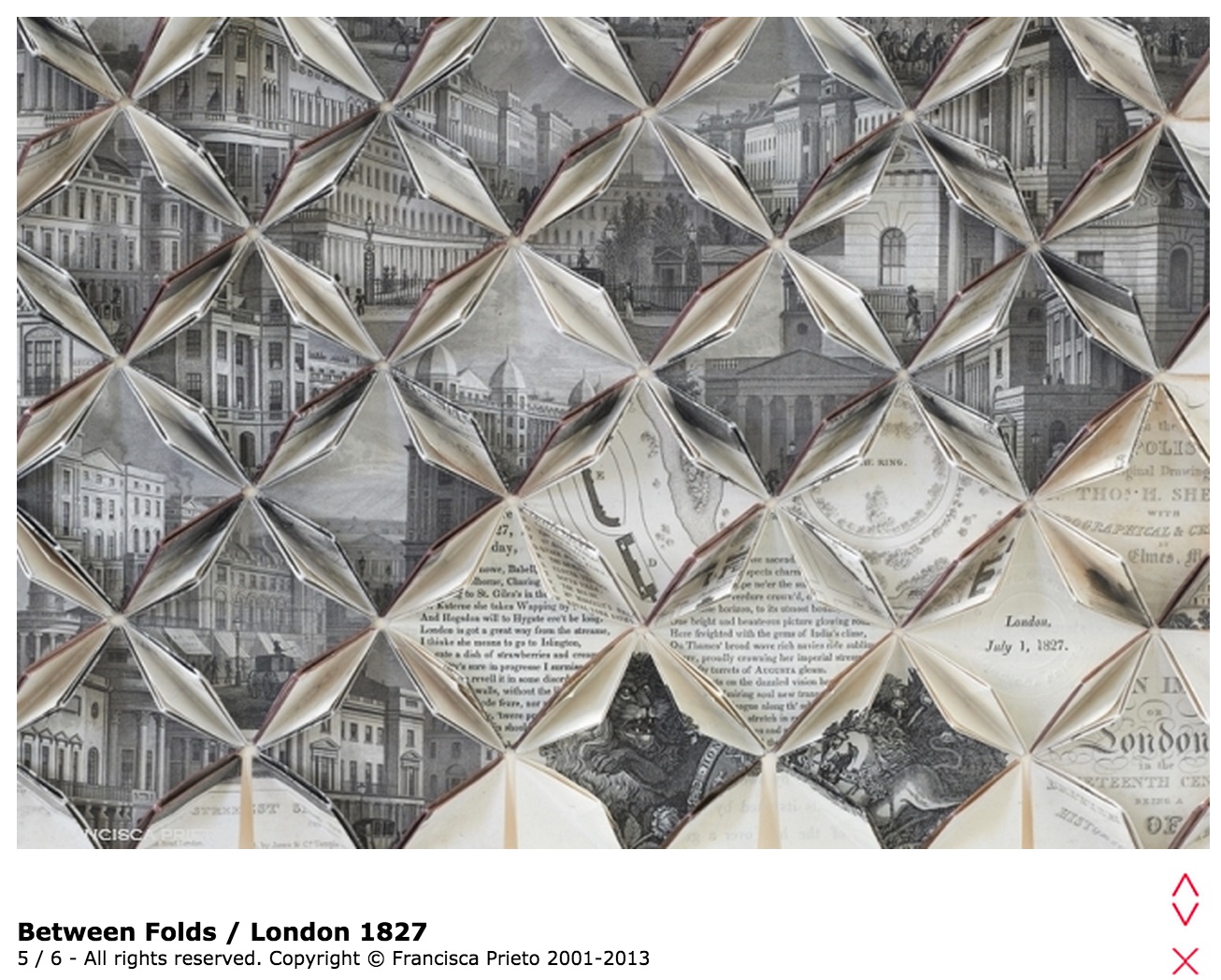

2014, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and London, UK

Simon Phillipson completed a variorum edition of On the Origin of Species, in which every verso page is the evolved or amended text and the recto page is the final text from the the Sixth edition.

Printed in the Netherlands on special 60gsm bible paper and finished with a special metallic bronze ink

The verso pages are completely printed in a special metallic bronze ink. The recto is printed in a combination of black and bronze ink. The bronze highlighted words in the recto correspond to the evolving or amending text in the verso. Very reminiscent of, but distinct from, Ben Fry’s The Preservation of Favoured Traces (see above).

2014, Minneapolis, MN

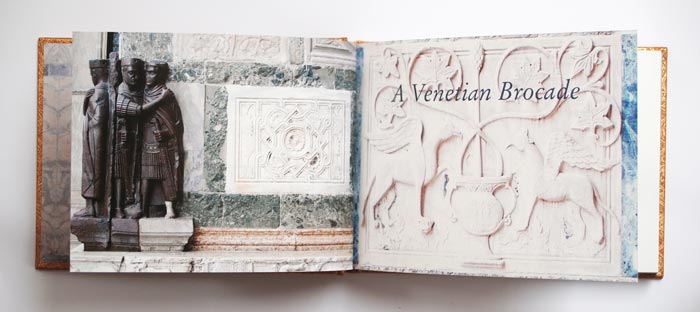

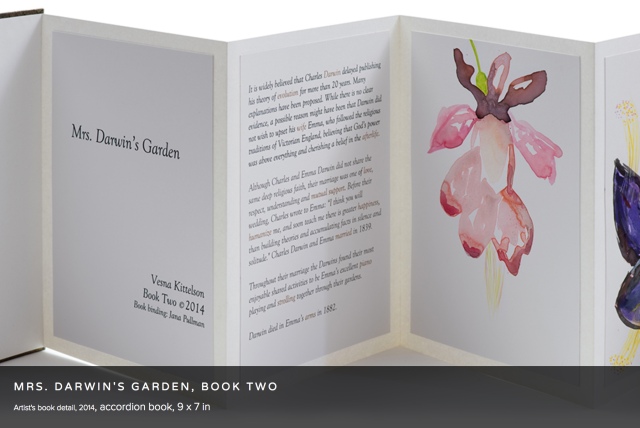

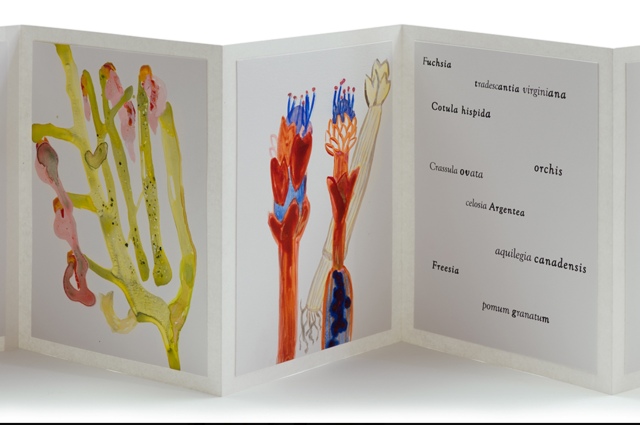

Mrs. Darwin’s Garden, Book Two (2014)

Accordion book, 9 x 7 in

Vesna Kittelson is an American-Croatian artist based in Minneapolis. Her résumé cites public collections ranging from Tate Britain and Minnesota Museum of American Art to Cafesjian Center for the Arts in Armenia and the Modern Museum of Art in Croatia. In 2009, she spent time at Churchill College, Cambridge University, where she learned about the life and marriage of Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood. Subsequently she created four artist books titled Mrs. Darwin’s Garden depicting primitive-seeming plants imagined as flora that Darwin might have seen from the deck of the Beagle. The names of the plants are made-up Latin names or variations on those of contemporary plants.

Accordion book, 9 x 7 in

These abstract images are imagined plants for Mrs. Darwin’s garden. They are illustrations of named floral specimens that never existed in reality. In Mrs. Darwin’s Garden they are presented as if they correspond to data derived from Darwin’s experimentation in his greenhouse. In this book I replaced the 19th C methods of botanical drawing with pouring paints to incorporate the contemporary notion of valuing an accident, followed by drawing with brushes and pencils to gain control and give the images a place and time in the 21st C.

2014, Grasswood, Saskatchewan, Canada

Jonathan Skinner (Warwick University) wrote in his preface to Decomp (see above):

Writing rots, meaning flees. … Yet the book is written to locate (some) meaning here. Would it make any difference to leave Decomp itself in the wilderness? Probably not.

Book artist, papermaker and co-founder with her husband David Miller of Byopia Press, Cathryn Miller reviewed Decomp in 2013. If not prompted by Skinner’s preface, Miller must have felt how appropriately evolutionary it would be to attempt to replicate the Decomp experiment by substituting the result of that experiment for the subject of the replicating experiment. Thus, in January 2014, Miller nailed to a tree “a book based on letting brand new copies of On the Origin of Species rot in various locations”.

Recomp (2014)

Copy of Decomp, Collis and Scott (2013) nailed to a tree

Photo credit: David G. Miller

For over twenty months, Miller monitored and husband David photographed the book’s weathering. That, however, was not the transformation that would result in an altered book and possibly a work of book art. Nature had some ironic appropriateness in store for Miller, Skinner, Collis, Scott and all of us. The blown pages were visited by Bald-faced Hornets, who digested them á la John Latham and his students but regurgitated them as cellulose with which to build a large nest.

Recomp (2015)

Photo credit: David G. Miller

Recomp (2015)

Nest composed of pages from Decomp, Collis and Scott (2013)

Photo credit: David G. Miller

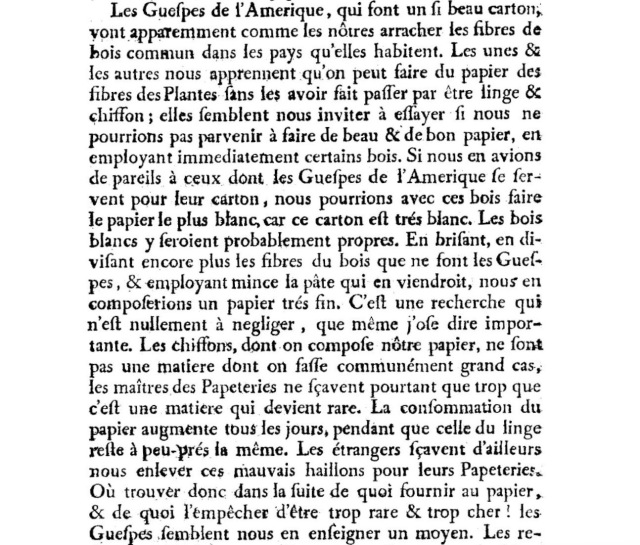

In the context of book art, the nest offers a curiously serendipitous digression. In 1719, the French naturalist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur published an essay to the Royal Academy of Sciences on the natural history of wasps. In the passage below, he hypothesizes how their natural papermaking industry could be adopted by man.

In 2015, Miller presented the results as Recomp in her blog at Byopia Press. In September that year, however, critics (raccoons, the artist thinks) visited the work and deconstructed it.

Photo credit: David G. Miller

Might this prove that, to paraphrase the last paragraph of On the Origin, “by laws acting around us…. from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals [and their art], directly follows”? If so, that makes raccoons and critics equal laws of nature.

2015, Umeå, Sweden

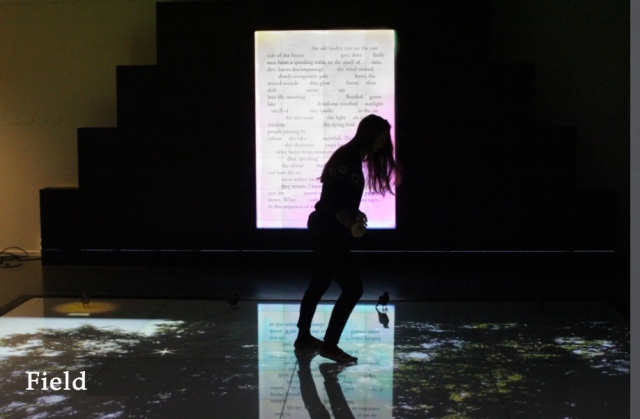

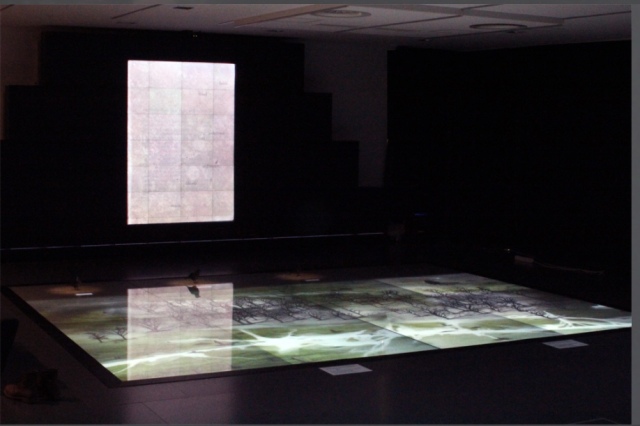

Johannes Heldén’s work Field is book, visual art and installation all in one. Heldén’s is perhaps the darkest variant on Darwin’s theme here.

It consists of interactive landscape animations on a floor touchscreen of 20 sqm,

Field (2015)

Produced, and premiered, at HUMlab, Umeå University

a series of sculptural mutations of the Eurasian Jackdaw*,

Field (2015)

Produced, and premiered, at HUMlab, Umeå University

an ever-changing soundscape and an interactive screen wall with a text responding to the changing DNA of the bird

Field (2015)

Produced, and premiered, at HUMlab, Umeå University

– as the ”code” of todays species is slowly lost, so is the code and context of language. The gaps in the text correspond to the shift in the DNA sequence, prose turns into dark poetry, connections and meaning changing for each iteration.

Field (2015)

Produced, and premiered, at HUMlab, Umeå University

Field (2015)

Produced, and premiered, at HUMlab, Umeå University

All these pieces are connected: as you explore the landscape and trigger the glowing touch points with your body, time is rapidly speeding up (clouds move over the scene, trees wither away, a flood is coming), one by one the four bird sculptures in the installation will be ”activated” with light and sound, spiraling the species further down into mutations. At the end of the piece, no lights remain in the landscape, the sound is immense, all mutations have occurred, the last poetry dissolves into entropy. Then all fades to black.

Since Darwin’s theory encompassed extinction, perhaps Heldén’s vision is not so much a variant on Darwin as it is a pessimistic appreciation and warning about the impact of our interaction with the entangled bank.

2016, Guildford, Surrey, UK

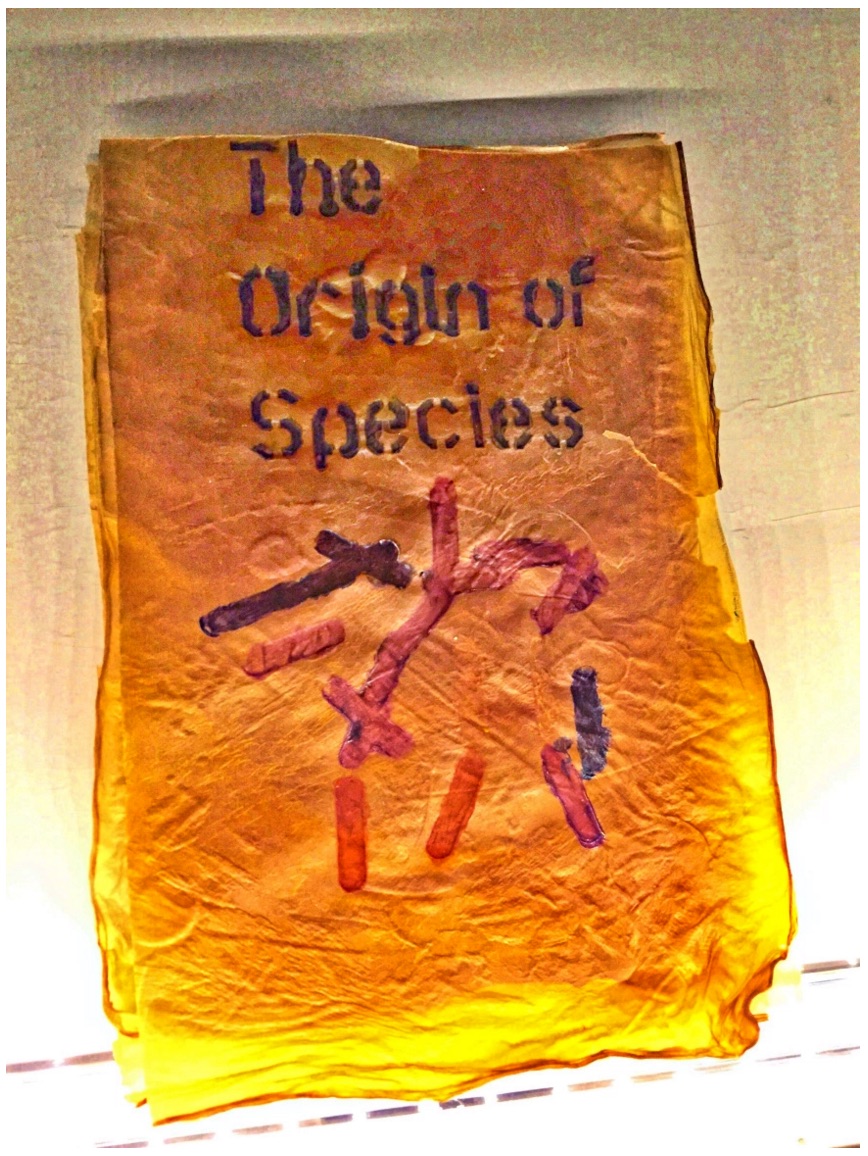

Cathryn Miller’s “bio-book-art” and that of Collis and Scott stand at the collaboration end of the bio art spectrum, where the artist yields considerable control to nature in the creative process. At the coordination end of the spectrum – closer to domestication of species – stands Dr. Simon F. Park’s bio-book-art – The Origin of Species – perhaps “the first book to be grown and produced using just bacteria”. Presented at the Edinburgh International Science Festival, the small book has pages made of bacterial cellulose, produced by the bacterium Gluconoacetobacter xylinus (GXCELL). Its cover is even printed with naturally pigmented bacteria.

The Origin of Species

“The small book shown here was grown from and made entirely from bacteria. Not only is the fabric of its pages (GXCELL) produced by bacteria, but the book is also printed and illustrated with naturally pigmented bacteria. ” Posted 27 March 2016

Photo credit: Dr. Simon F. Park

Although Park’s science-driven process for paper manufacturing and printing echoes the speculations of French naturalist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (see above), it seems to have much in common with the painstaking craft of handmade paper and hand letterpress printing. The first sheet of Park’s micro-organically grown paper took a little under two weeks to be generated and stencilled with his bacterial ink.

2016, Colchester, Essex, UK

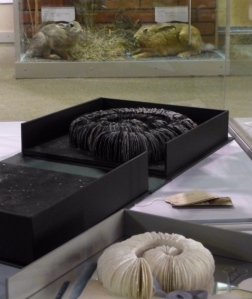

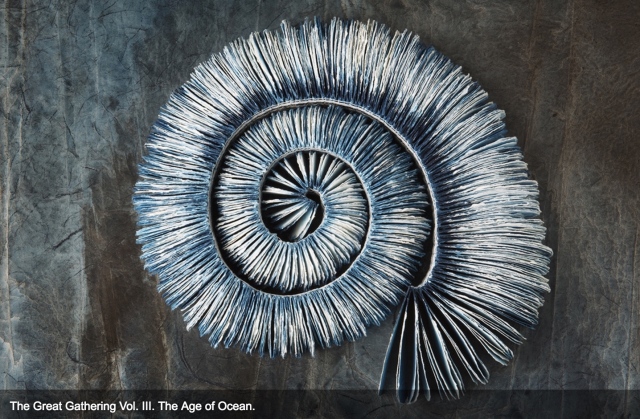

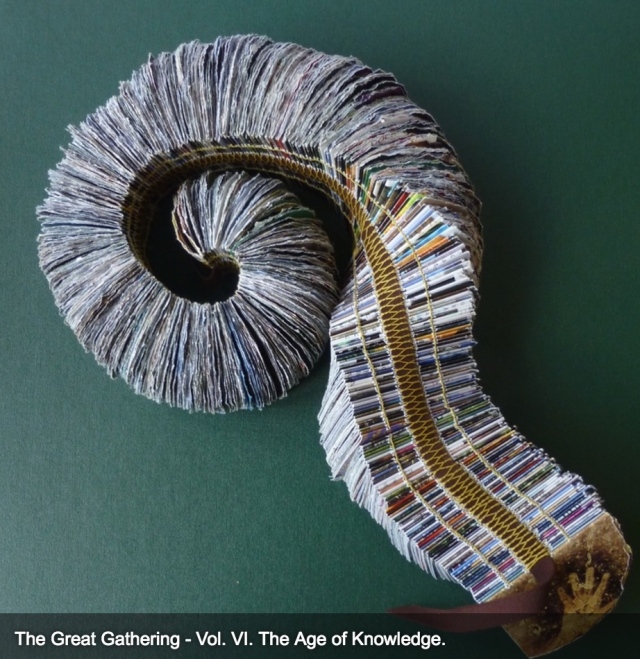

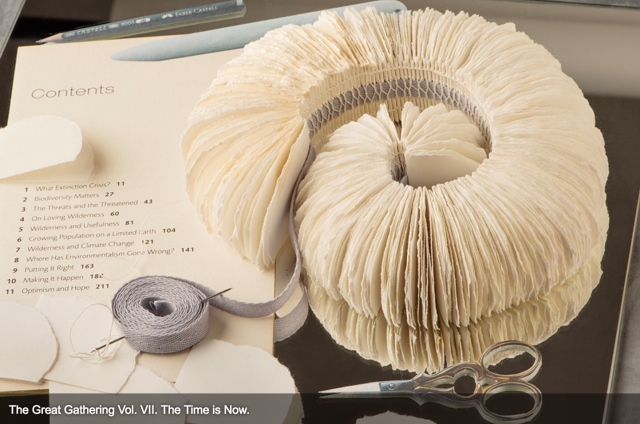

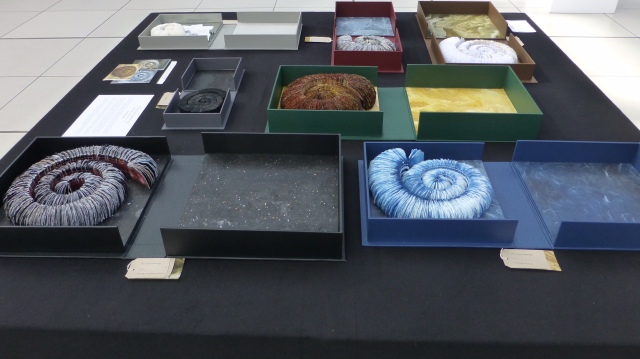

It seems chronologically backwards to move from bio-book-art’s live media to Chris Ruston’s ammonites of The Great Gathering. As should be evident by now, however, the evolution of the symbiotic relationship between book artists and Darwin has been anything but a straight line. It has curved, circled and recursed.

Tim Rollins + K.O.S may have had their séance 30-50 feet away from Darwin’s lodgings in Edinburgh, but Chris Ruston brought her Darwin-inspired book art to an even more fitting venue: a church converted into Colchester’s Natural History Museum.

Colchester, Essex, England

Photo credit: Chris Ruston

As the artist comments at her site:

The Great Gathering refers to our continued exploration of where we have come from, and where we are going. Combined the seven volumes tell an amazing story spanning 650 million years. Sculptural in form, each book reflects a moment of this journey. From black holes and dark beginnings, through ocean and sediment layers, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, and recycled National Geographic magazines the work charts the inevitability of change.

Natural History Museum, Colchester

Photo credit: Chris Ruston

They are a response to visiting Museum collections, in particular the Natural History Museum, Colchester and the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Cambridge. Fossils have enabled us to unlock the story of our Origins – from the largest creatures to the smallest organisms. The 19th century saw an explosion of knowledge and understanding, culminating in Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species. By piecing together the riddle of the fossil record, Darwin and his contemporaries began asking revolutionary and challenging questions, the results of which are still felt today.

Natural History Museum

Photo credit: Chris Ruston

Science and art are the presiding geniuses over The Great Gathering. In The sciences of the artificial (1969), Herbert Simon emphasized: “The natural sciences are concerned with the way things are” and engineering, with the way things ought to be to attain goals. Like the scientist, the artist, too, is concerned with the way things are. They are the raw material with which the artist works or to which he or she responds. But like the engineer or the designer, the artist is concerned with the way things ought to be:

The Great Gathering, 2016

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

how a solander box ought to be constructed to operate with the work and, in enclosing it, be “the work”;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

what materials (photos from the Hubble telescope) ought to be used to reflect a moment in time;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

how thread, tape and stitch ought to be to hold together a spine that will flex and spiral into the shape of a fossil;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

how the color of the material ought to be juxtaposed with the material’s altered shape to carry meaning;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

how the shift from content to blankness ought to be juxtaposed with the material’s altered shape to carry meaning;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

how the selection and alteration of text ought to be made to show the fixity and flux of knowledge and ourselves;

The Great Gathering (2016)

Photo credit: Chris Matthews

and how our reflection in the mirror in Volume VII under the maker’s tools and the made thing ought to implicate us — the viewer here and now – in an ongoing process of making and remaking.

Photo credit: Chris Ruston

If you have come this far with these bookmarks on the evolution of book artists’ symbiosis with Darwin, note that today and every 12th of February is Darwin Day, marking international celebrations of the birth of Charles Darwin and his contributions to science. From today’s engagements and all those to come with the concepts of On the Origin of Species and (I hope) with these bookmarks, perhaps new discoveries and new creations of book art will emerge.

For further reading about

Stephen Collis: Facebook

Ben Fry: Ben Fry

George Gessert: Revolution Bioengineering

Johannes Heldén: News

Kelly M. Houle: ASU Magazine

Vesna Kittelson: Form + Content Gallery

Emma Lloyd: Facebook

Greg McInerny: Warwick University

Cathryn Miller: Byopia Press

Simon F. Park: Exploring the Invisible

Simon Philippson: LinkedIn

Stefanie Posavec: Wired

Tim Rollins: Artspace.com, Brooklyn Rail (article by Thyrza Nichols Goodeve)

Chris Ruston: Essex Life

Jordan Scott: Twitter

Diane Stemper: Saatchi Art and “– in medias res – Diane Stemper“. 9 September 2017. Bookmarking Book Art.

Angela Thames: Angela Thames

Sam Winston: Articles

de Lima Navarro, P. & de Amorim Machado, C. “An Origin of Citations: Darwin’s Collaborators and Their Contributions to the Origin of Species”, J Hist Biol (2020).