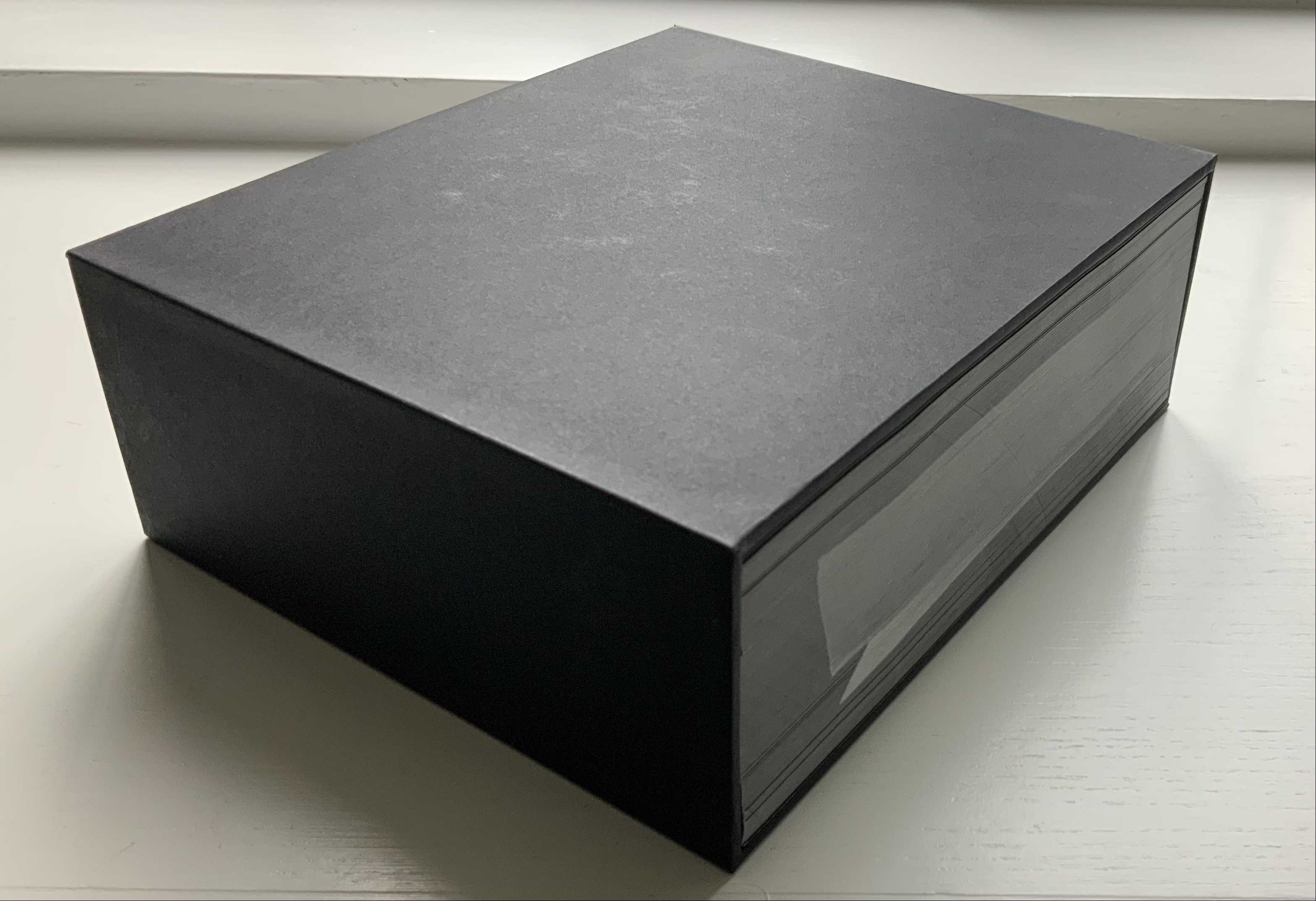

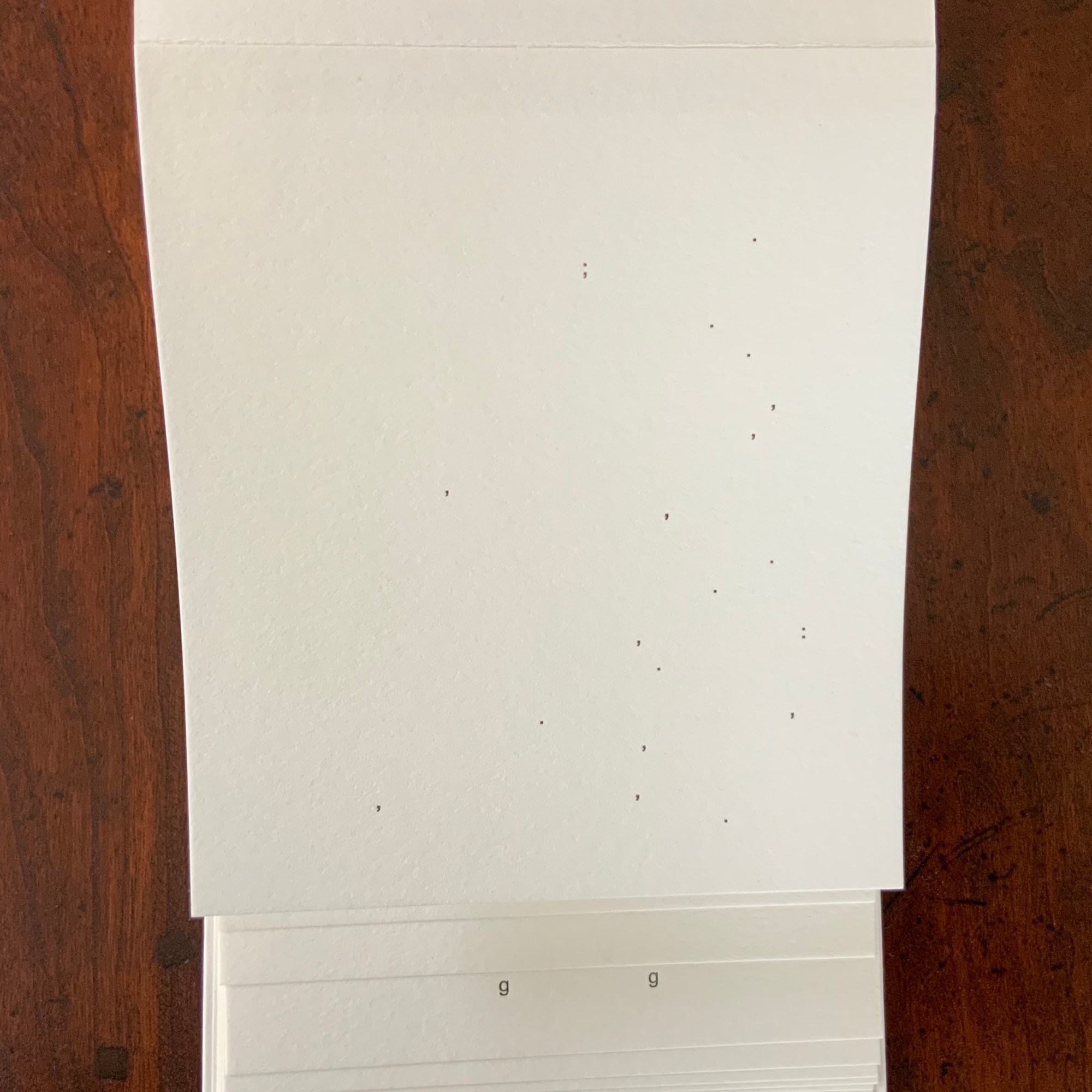

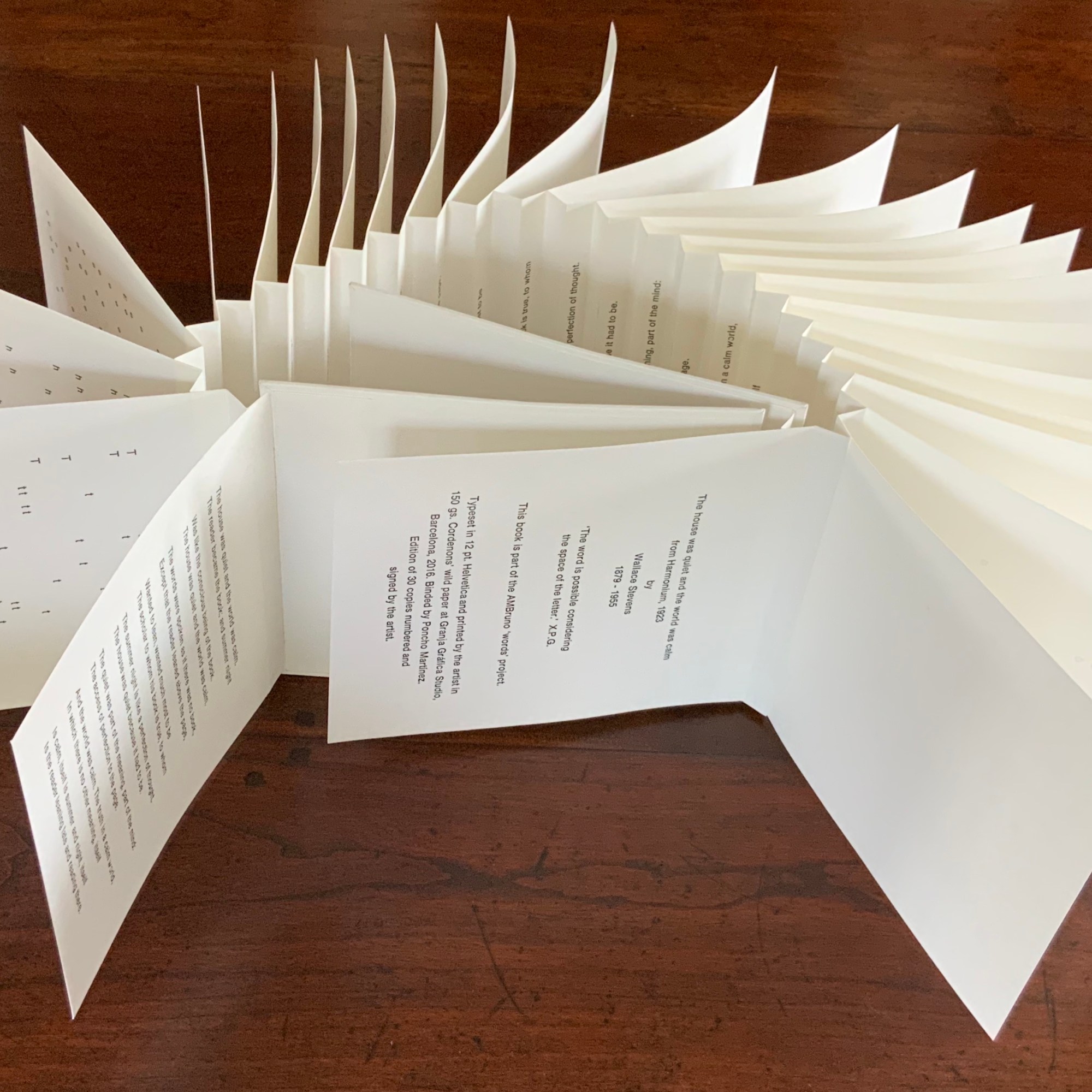

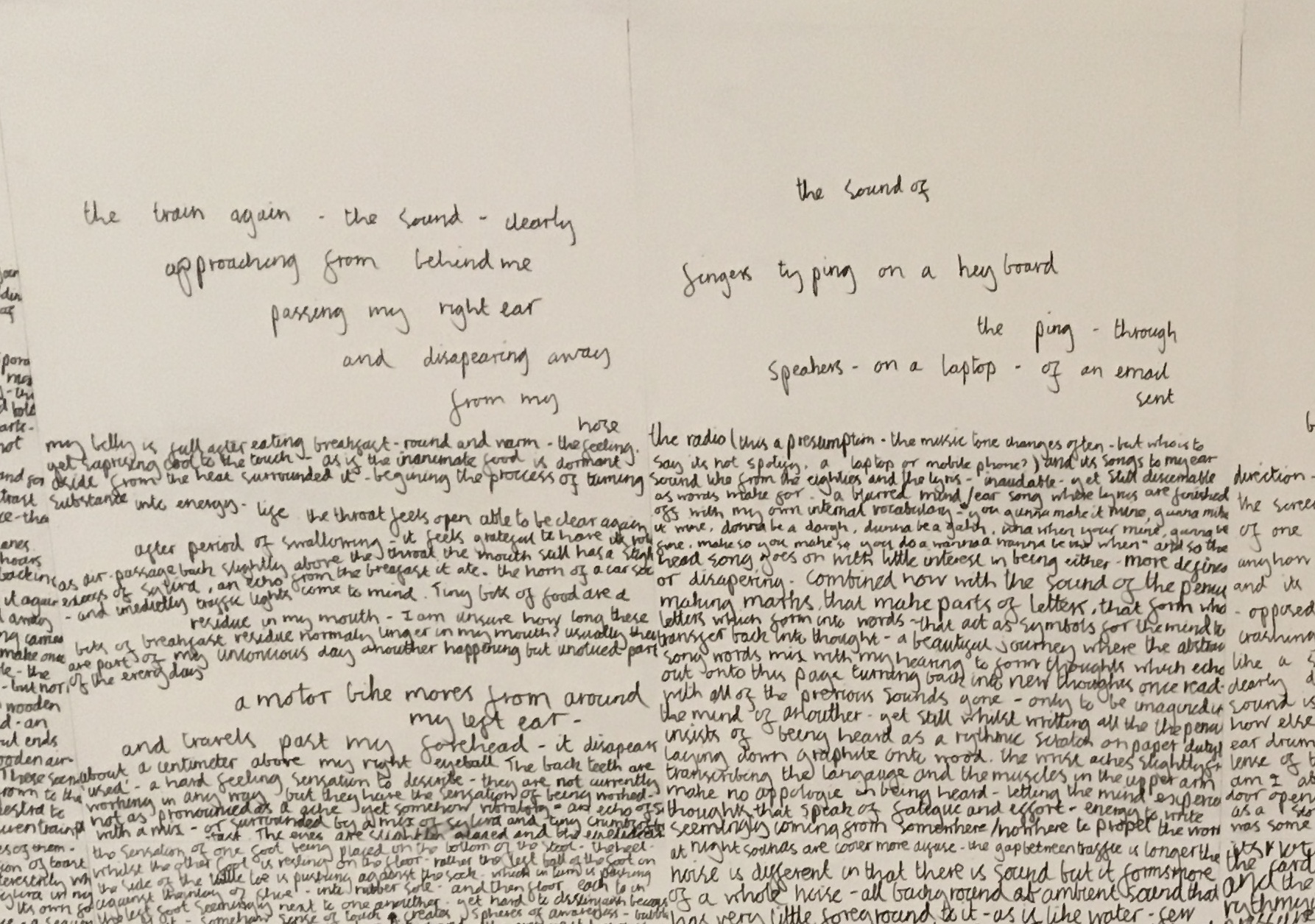

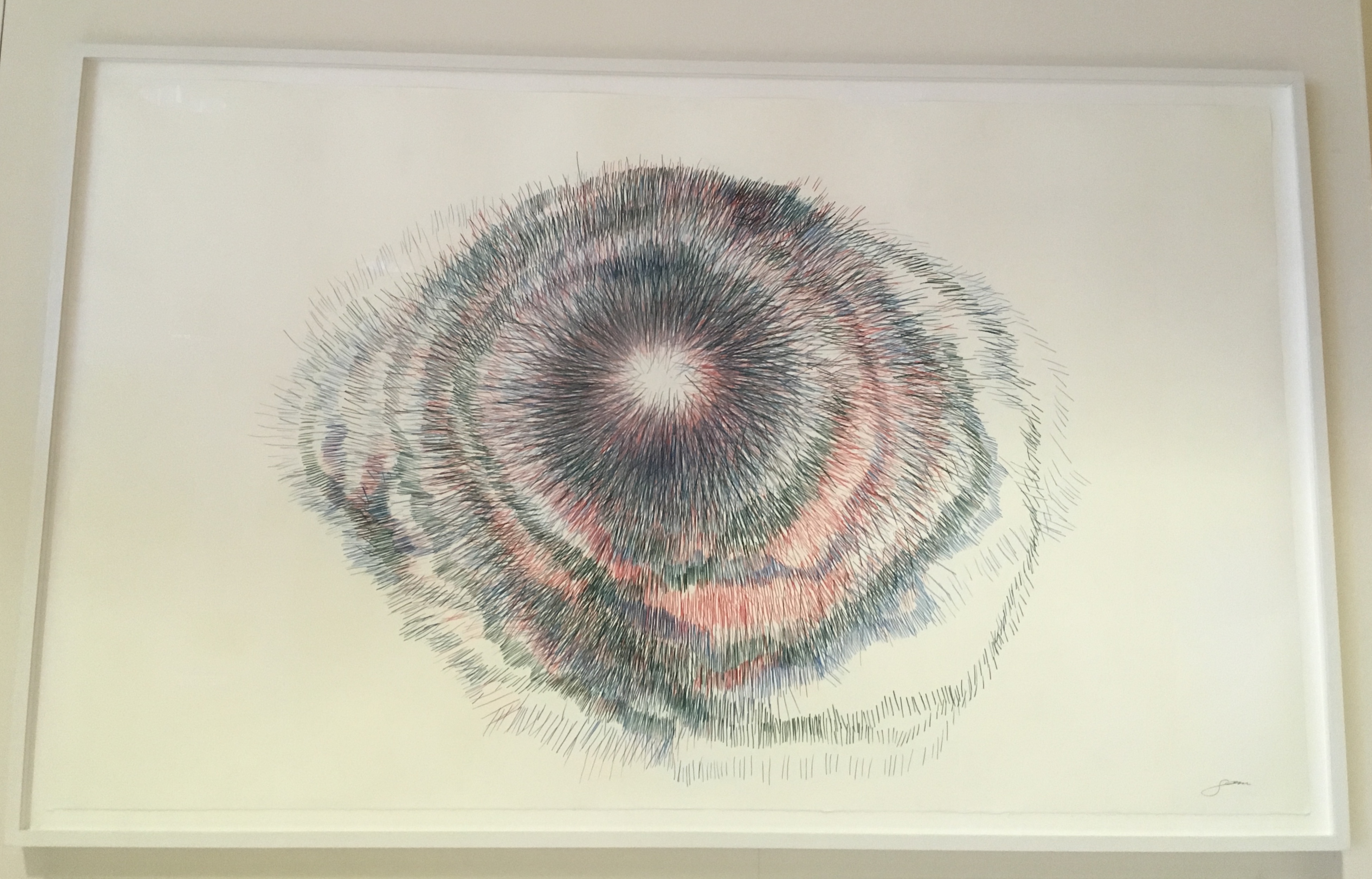

Infant A (2012)

Infant A (2012)

Louis Lüthi

Thread-stitched signature. H225 x W160 16 pages. Edition of 1000. Acquired from Torpedo Books, 8 January 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection

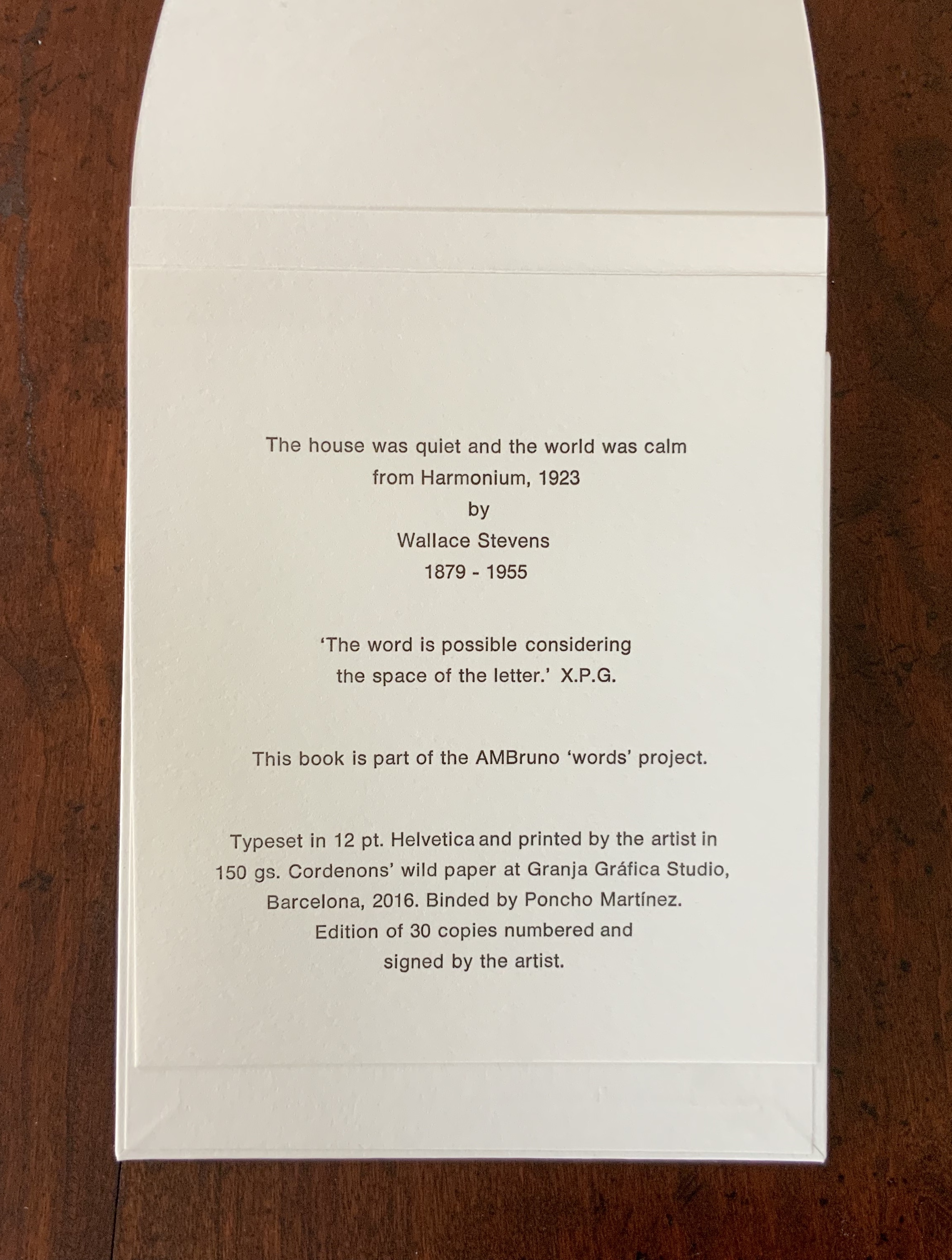

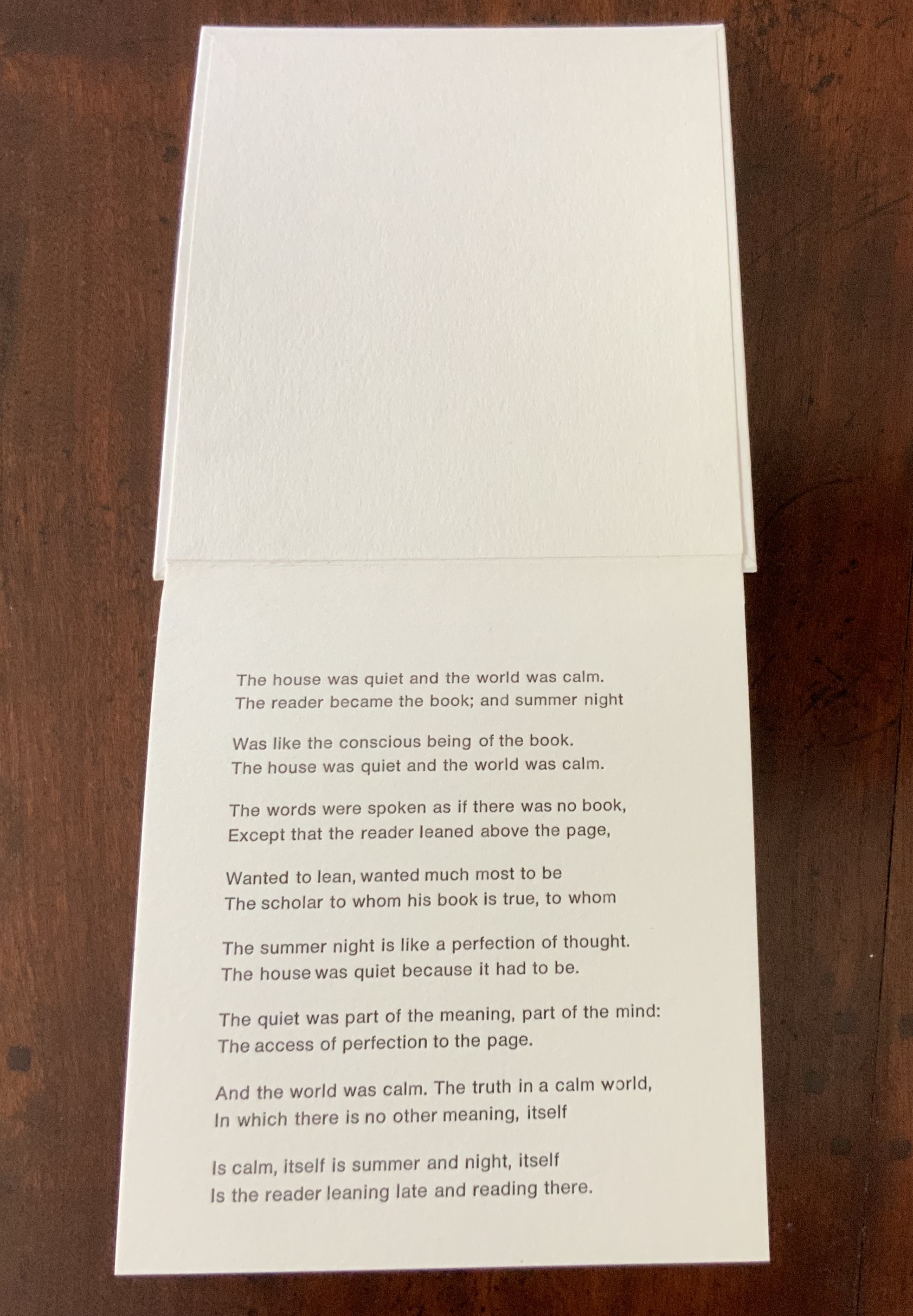

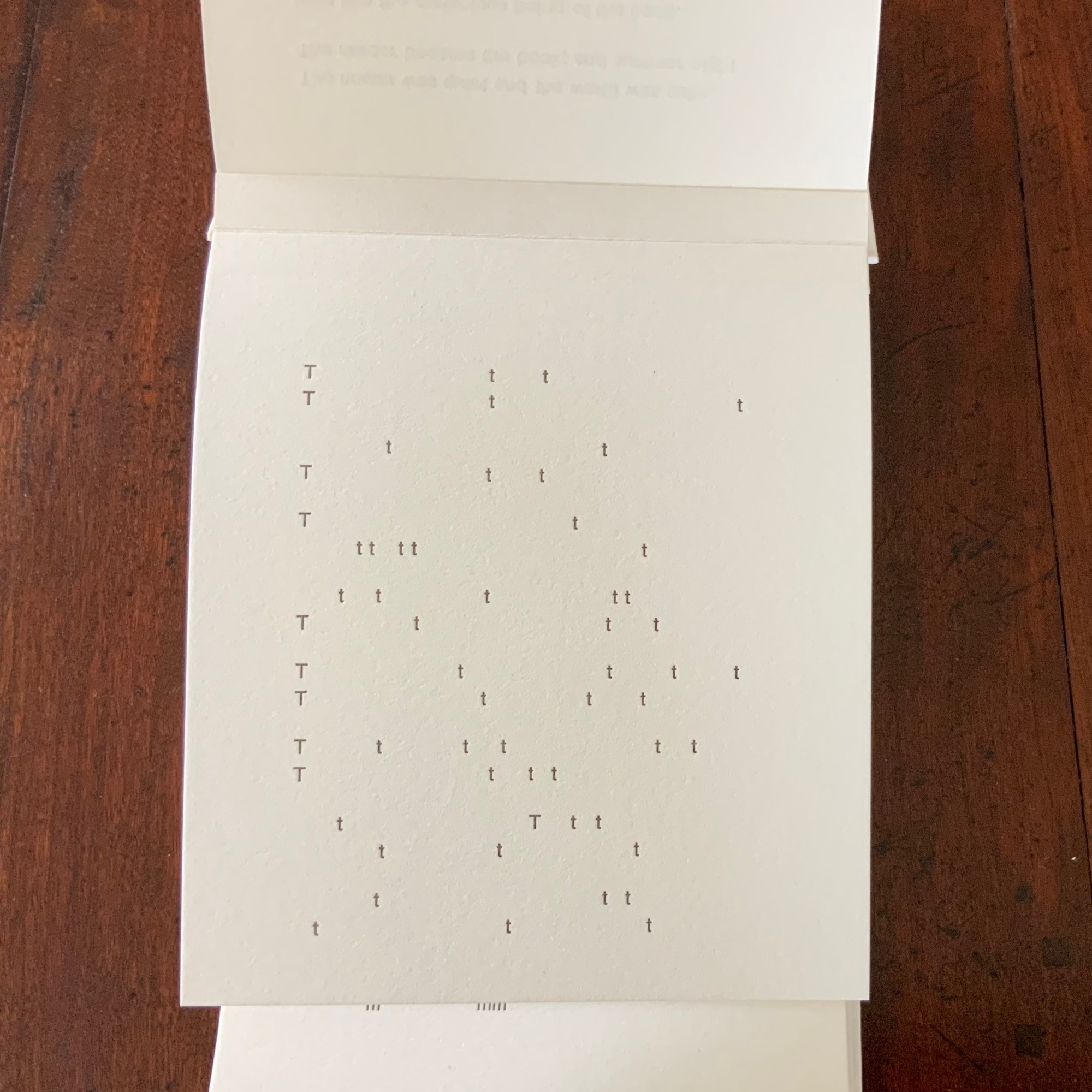

Infant A is part of a collection of essays commissioned by castillo/corrales and published by Paraguay Press under the series title The Social Life of the Book. Lüthi’s contribution fits the Books On Books Collection on several scores. First is the epigram’s invocation of the alphabet, which echoes the collection’s concentration of alphabet-related artists’ books and children’s books. See Alphabets Alive! Second is the epigram’s source: Wallace Stevens, whose poetry has inspired Ximena Pérez Grobet’s Words (2016). Would that other book artists be so inspired. Third is the narrator’s fictional conversation with Ulises Carrión in a celebration of all things A-related, in particular Andy Warhol’s novel a: a novel (1968), which finds analogues in Warren Lehrer’s A Life in Books: The Rise and Fall of Bleu Mobley (2013) and Derek Beaulieu’s a, A Novel by Andy Warhol (2017) (entry in progress). Fifth is how the dialogue reminds me of Suzanne Moore’s A Musings (2015).

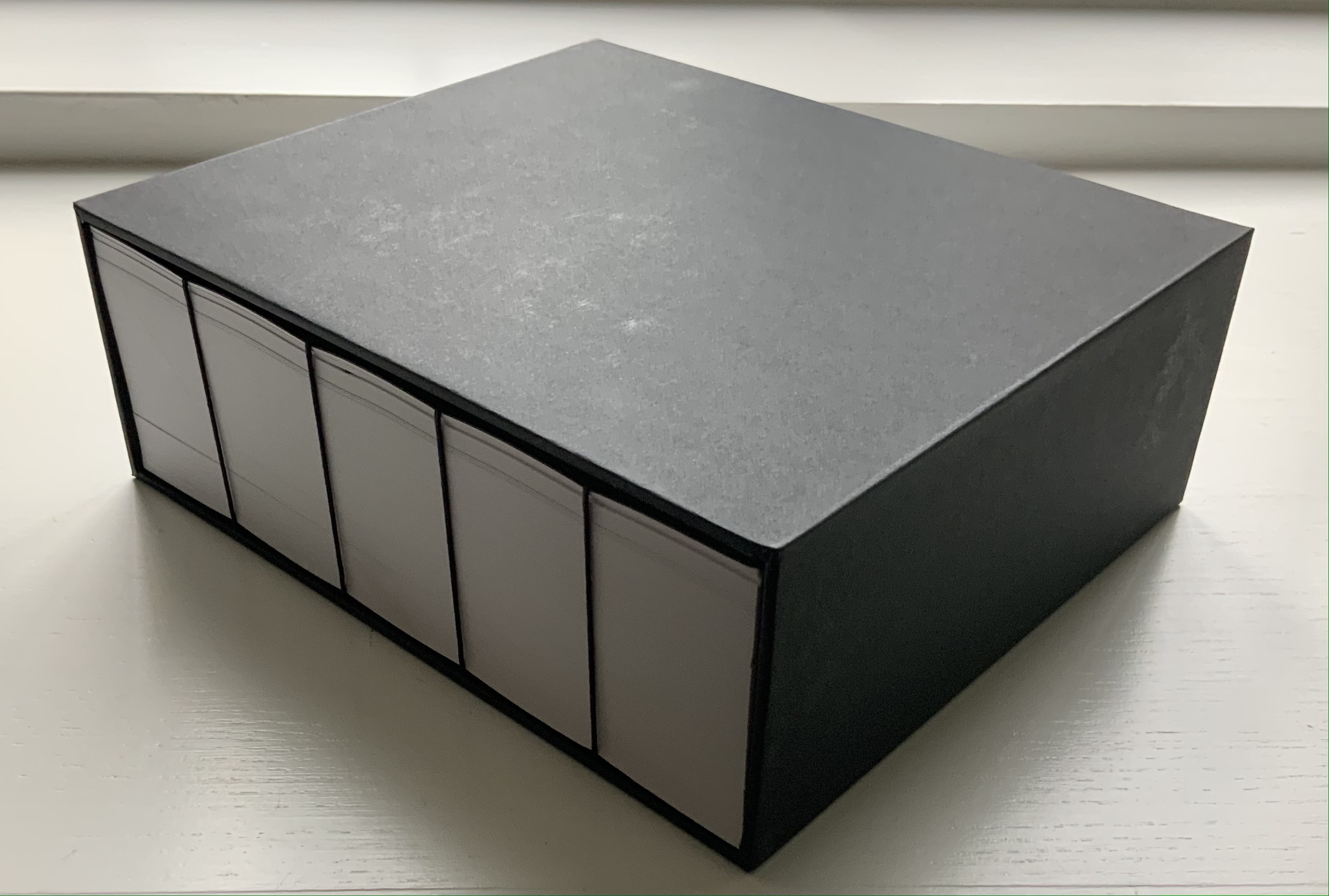

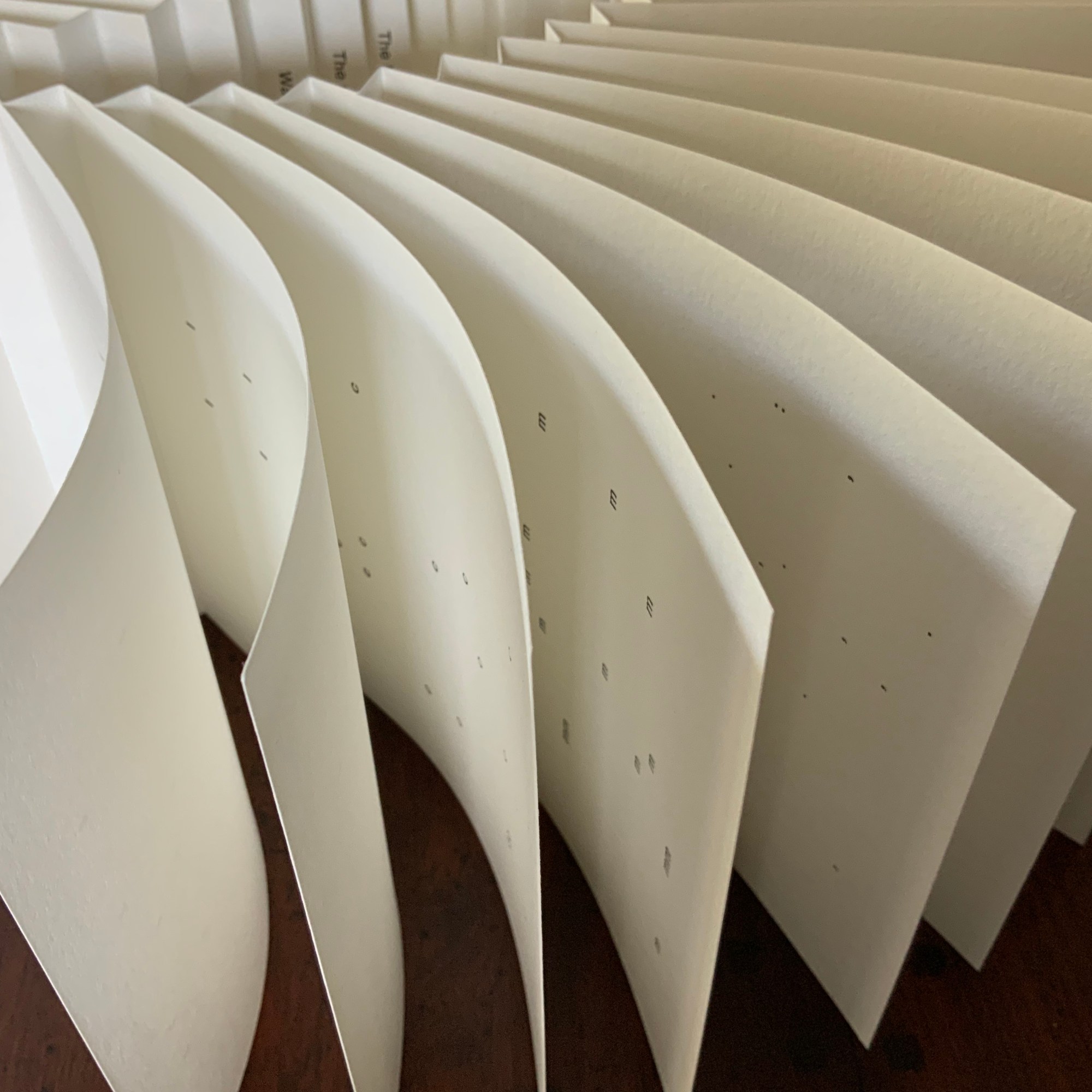

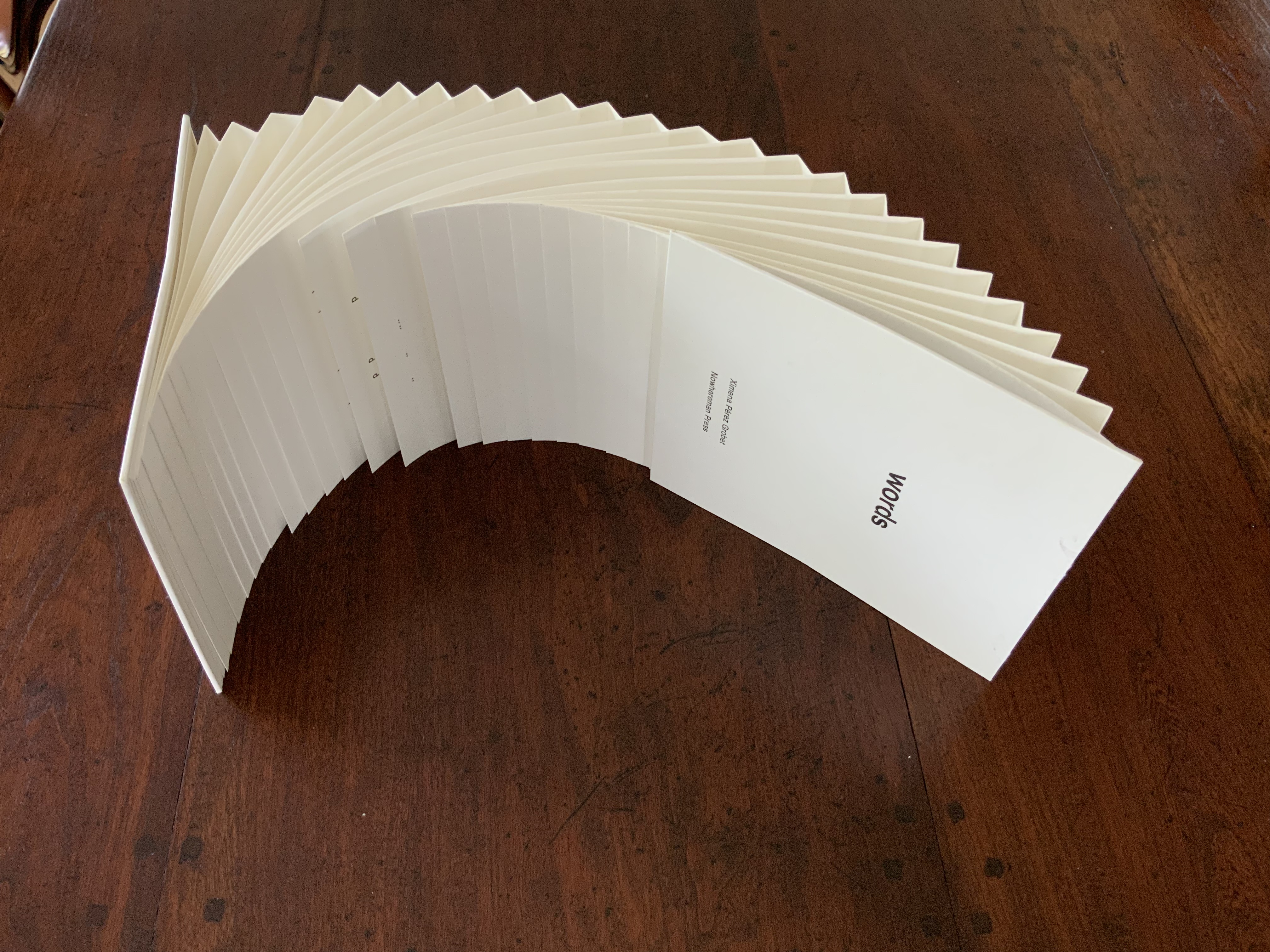

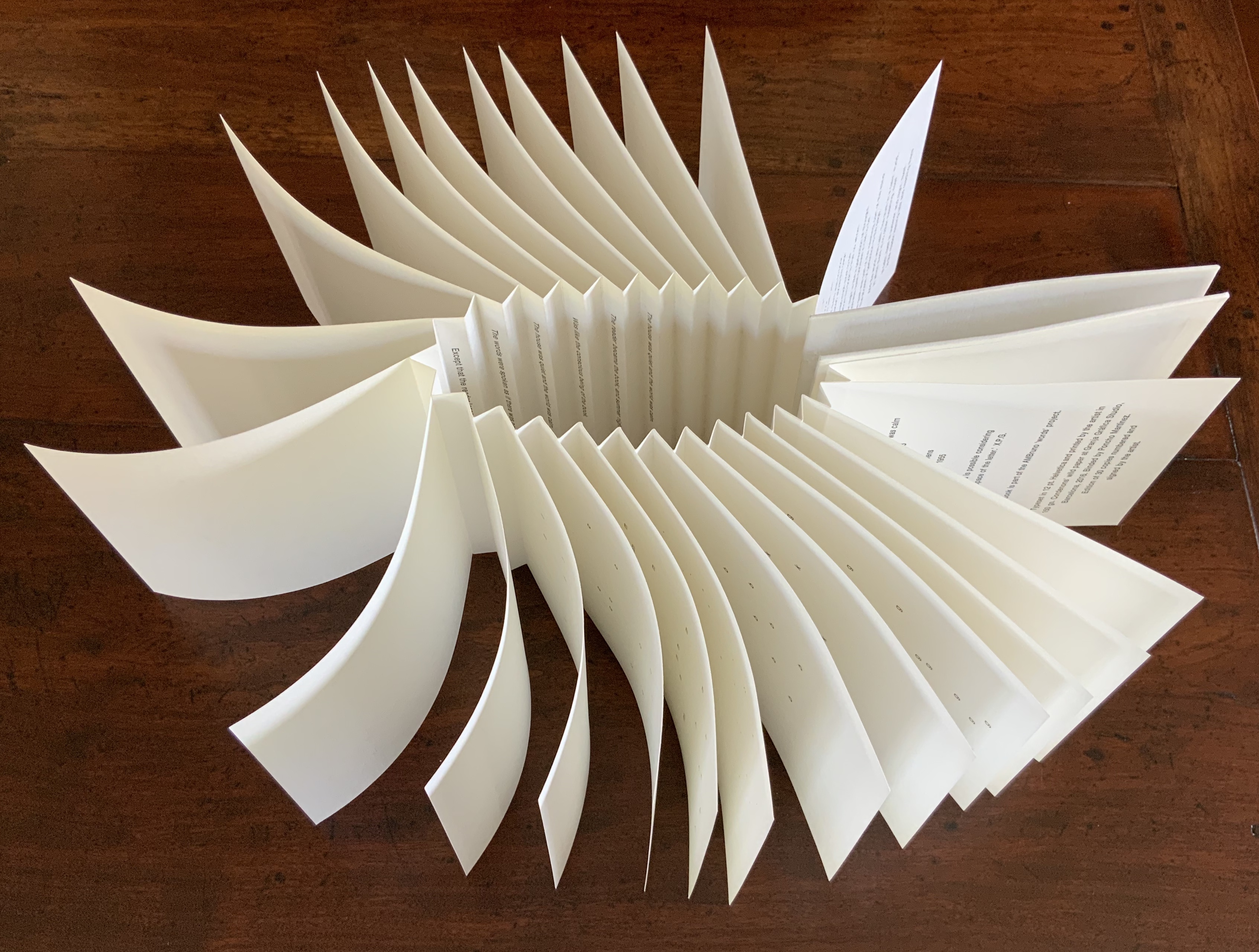

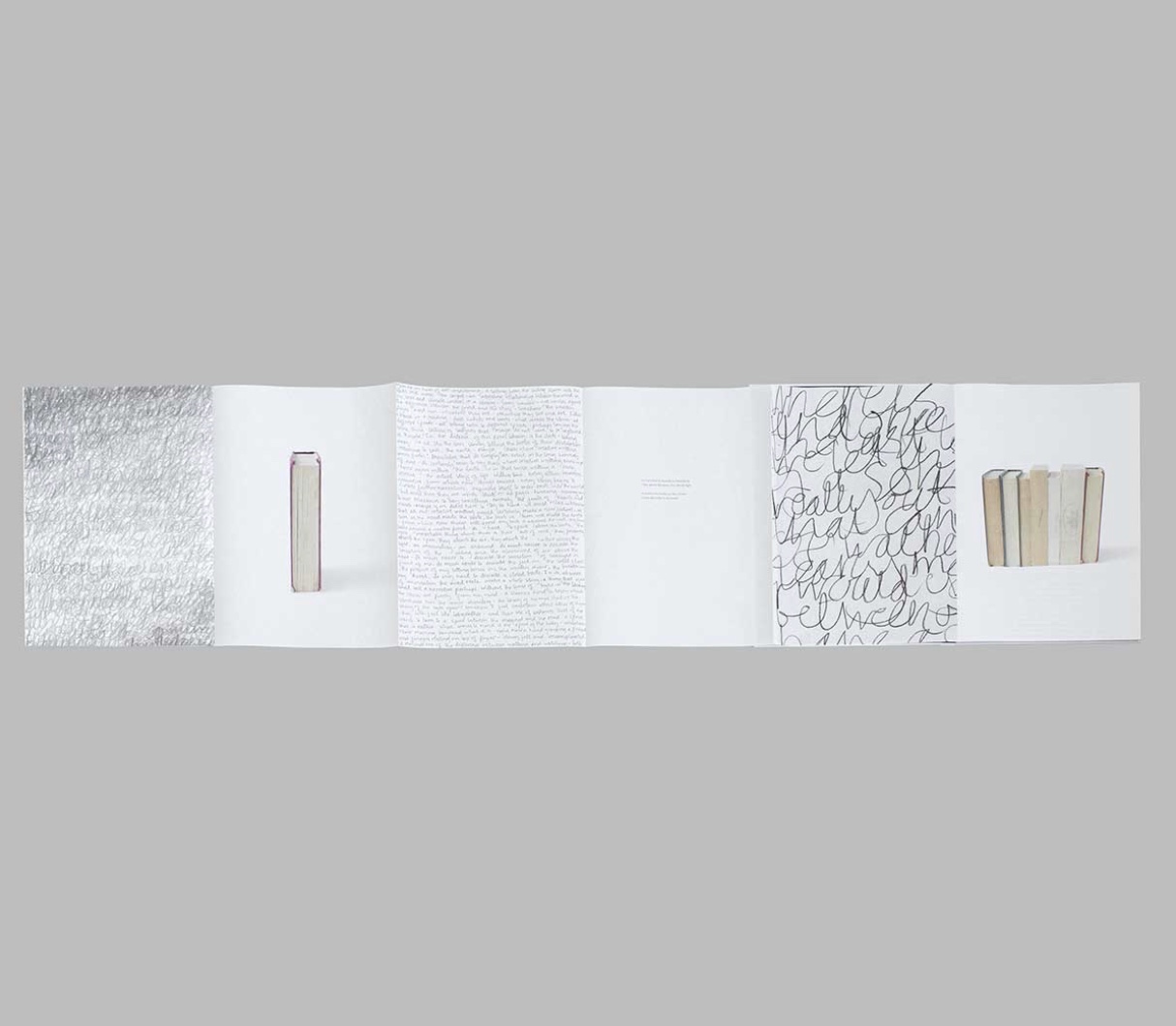

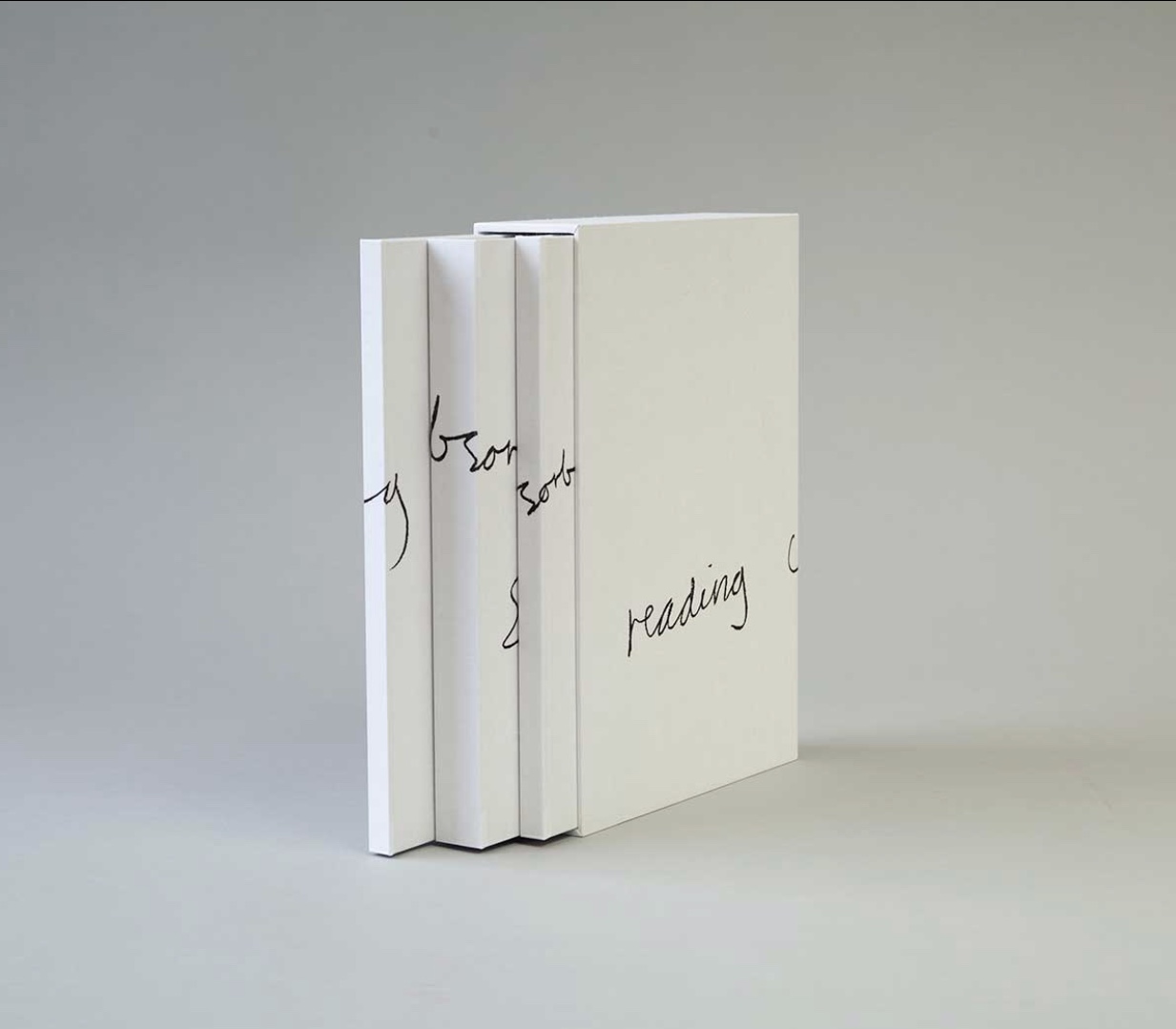

A Die With Twenty-six Faces (2019)

A Die With Twenty-six Faces (2019)

Louis Lüthi

Paperback. H200 x W130 mm. 104 pages. Acquired from Amazon, 18 September 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection

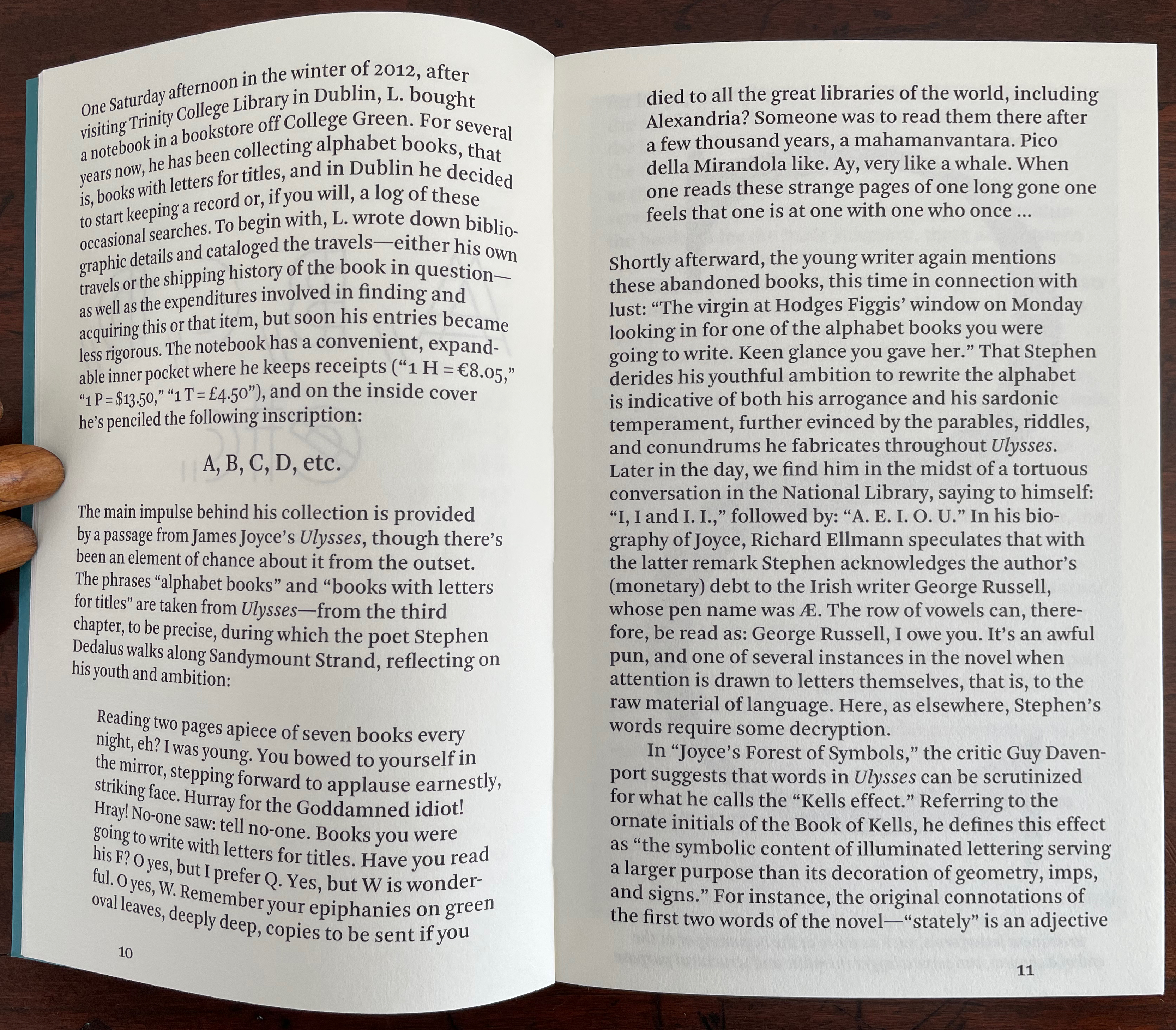

Walter Benjamin’ unpacking of his library has a lot to answer for. Not only do we have Buzz Spector‘s take on it in 1995, but Jo Steffens’ Unpacking trilogy of photos of architects’, artists’ and writers’ bookshelves, Alberto Manguel’s elegiac Packing My Library (2018), and here is Louis Lüthi’s.

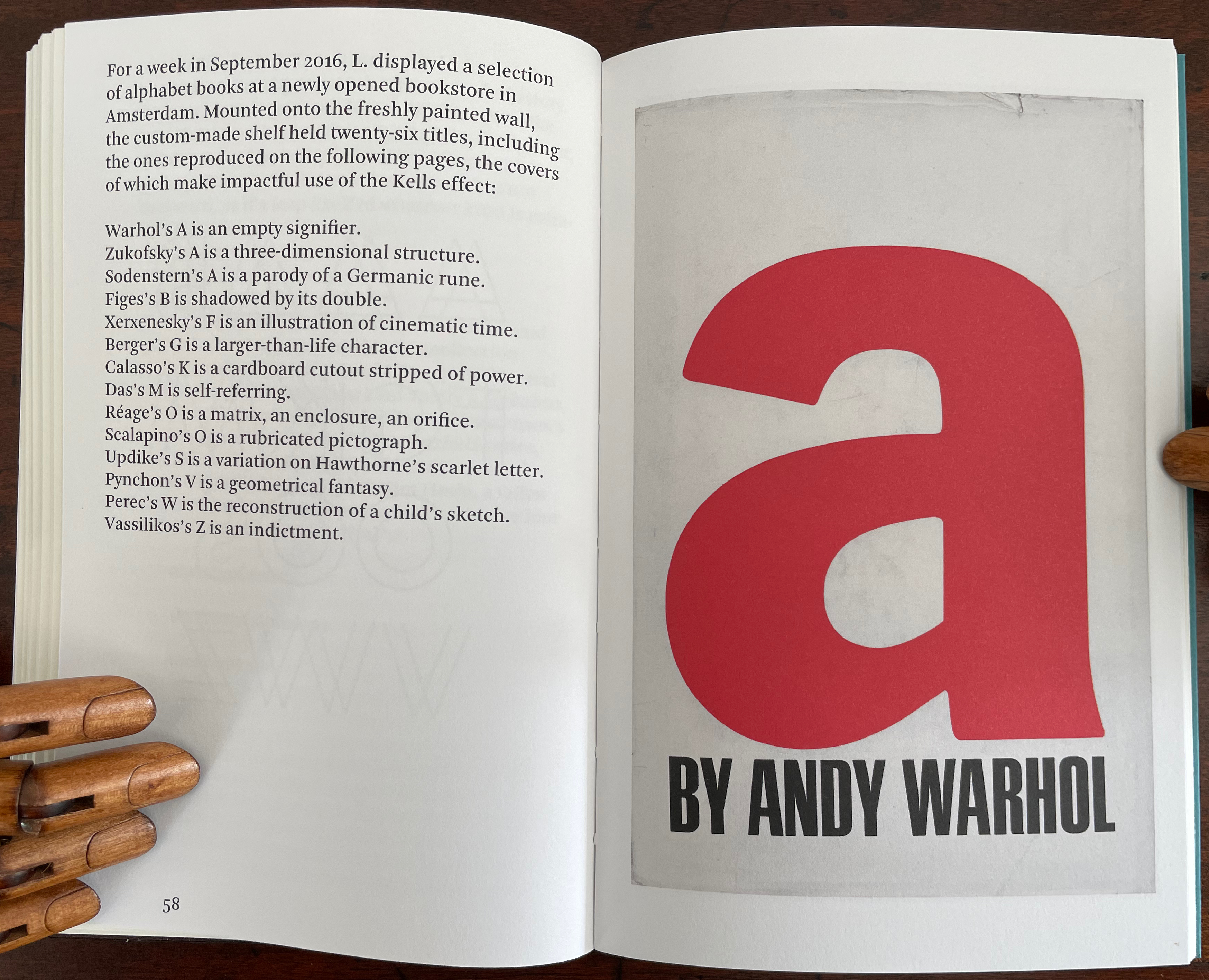

Publisher’s website: In A Die with Twenty-Six Faces, the author — let’s call him L. — guides the reader through his collection of alphabet books, that is, books with letters for titles. Some of these titles are well known: Andy Warhol’s “a,” Louis Zukofsky’s “A”, Georges Perec’s W. Others are obscure, perhaps even imaginary: Zach Sodenstern’s A, Arnold Skemer’s C and D. Tracing connections between these books, L. elaborates on what the critic Guy Davenport has called the “Kells effect”: “the symbolic content of illuminated lettering serving a larger purpose than its decoration of geometry, imps, and signs.”

The title stirs thoughts of Marcel Broodthaers’ oracular statement in 1974 “I see new horizons approaching me and the hope of another alphabet”. An alphabet that unrolls across the twenty-six faces of a die would certainly qualify as another alphabet. Broodthaers and the die also stir thoughts of Stéphane Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira le Hasard to which Broodthaers paid repeated homage. Throwing a twenty-six-sided die would certainly no more abolish chance than would a roll of Mallarmé’s six-sided die. Lüthi’s game, however, has little to do with chance unless we count his luck in finding the works to build his library of single-letter-entitled books. Even less to do with luck if some of the library is fictitious, a likelihood that the “publisher’s” statement suggests. Lüthi’s die is loaded!

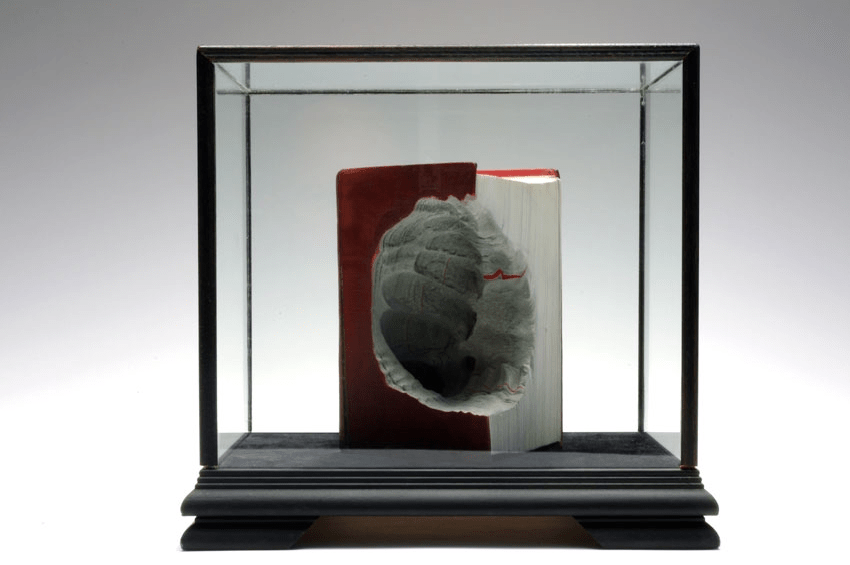

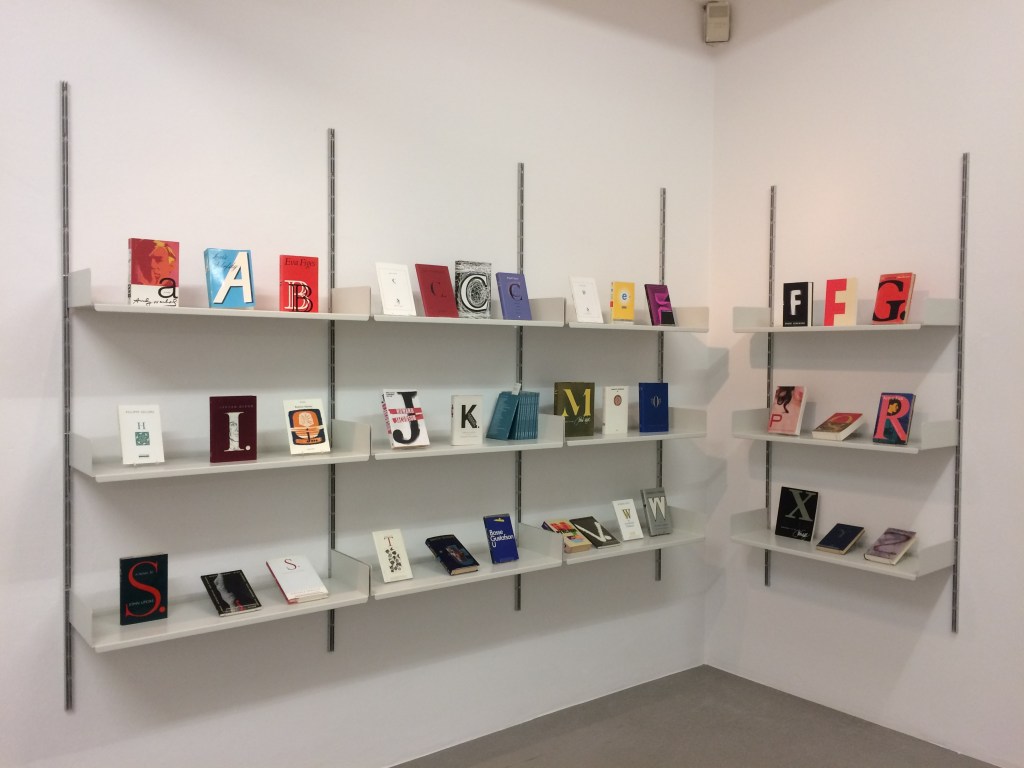

A selection of Lüthi’s “alphabet” books on display. Courtesy of the author.

Photo: Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst Bremen

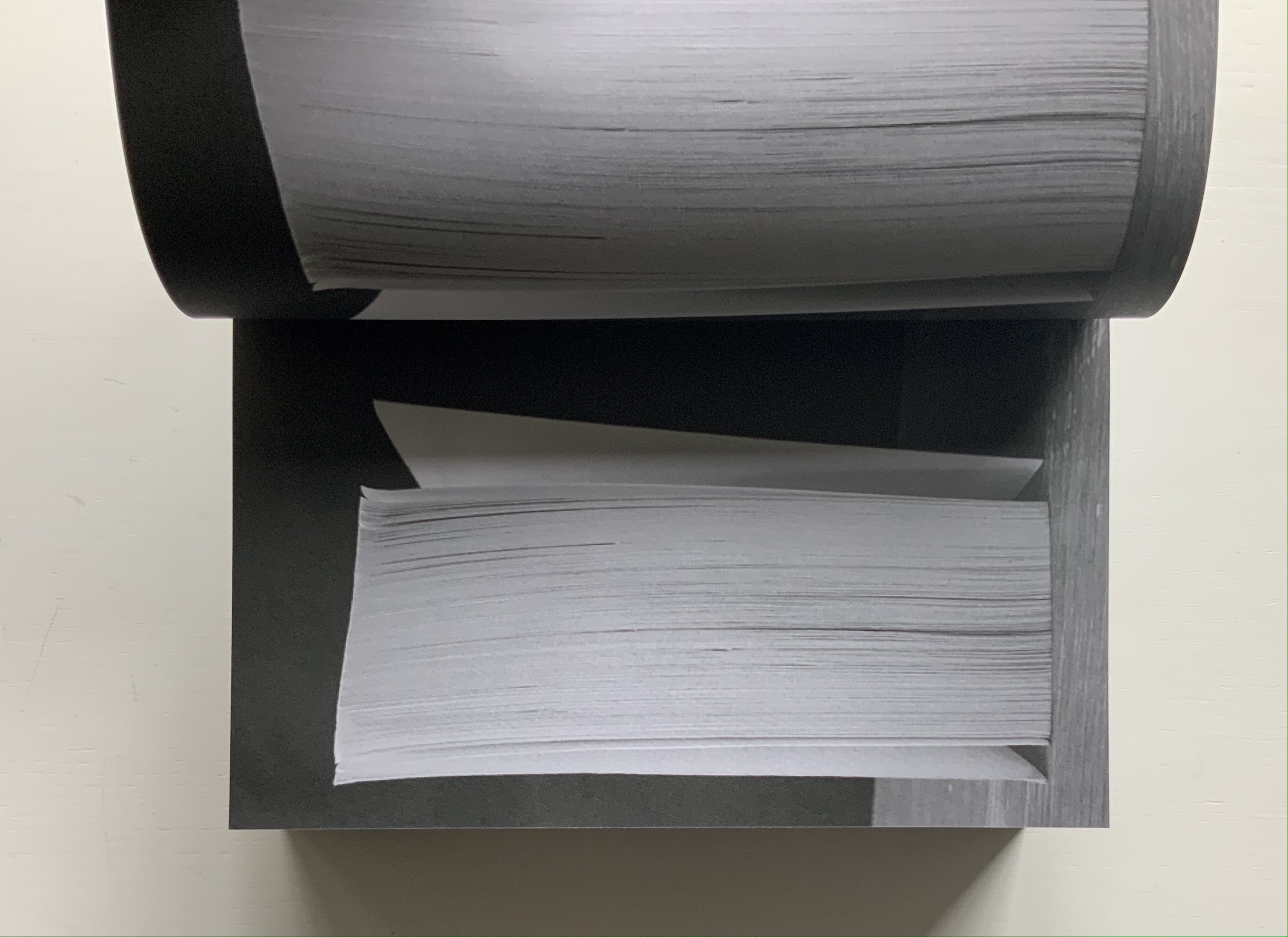

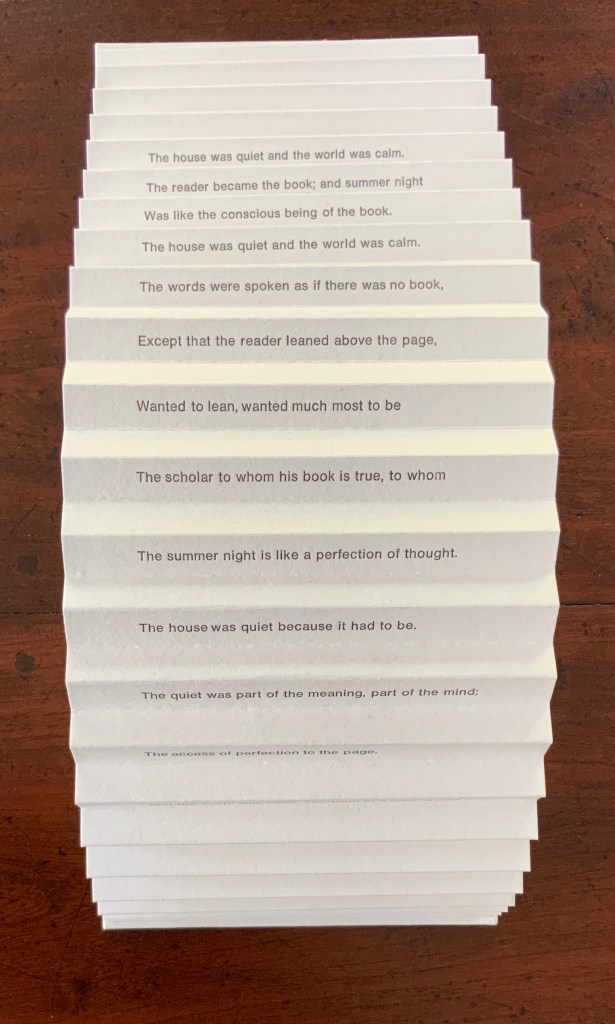

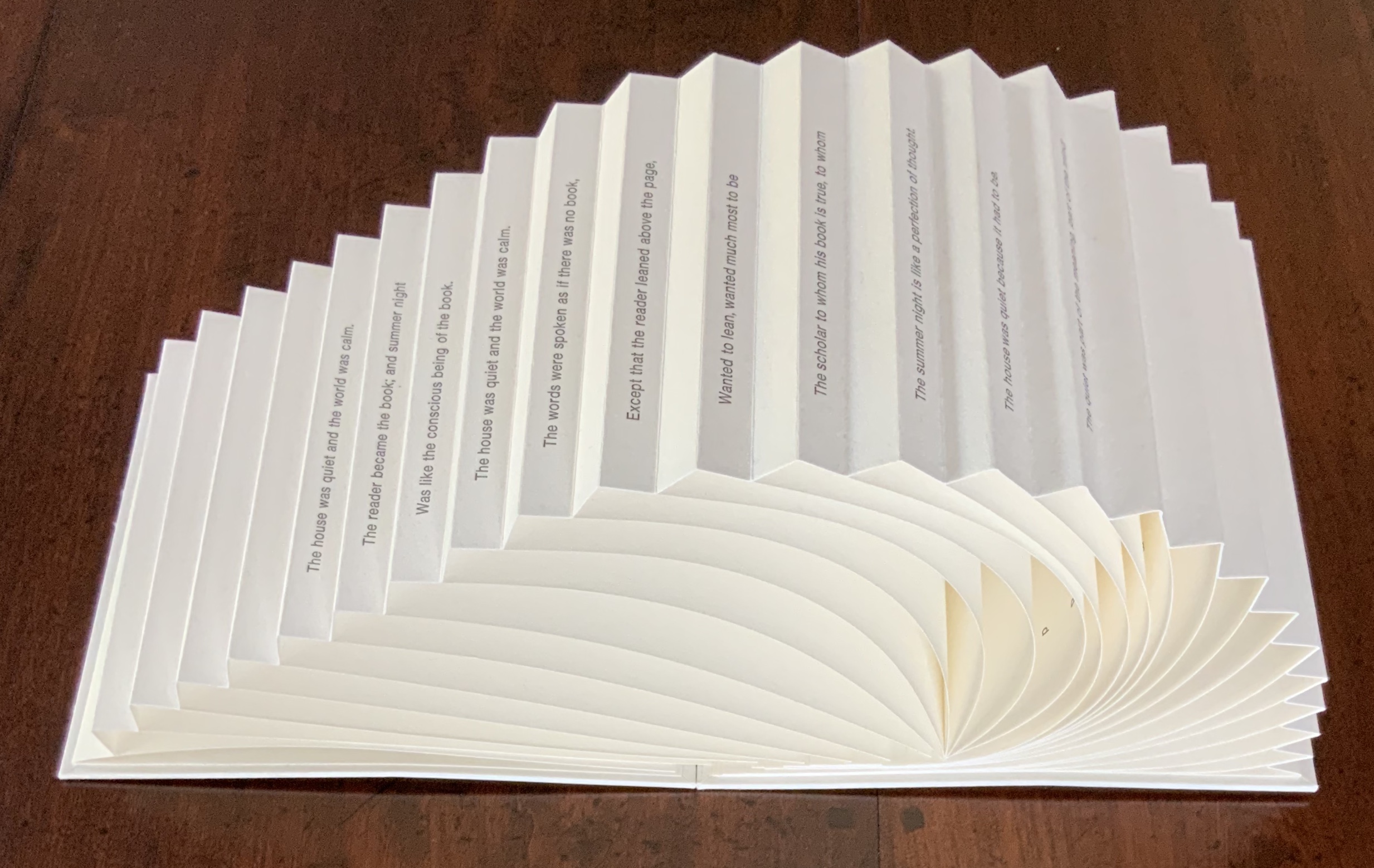

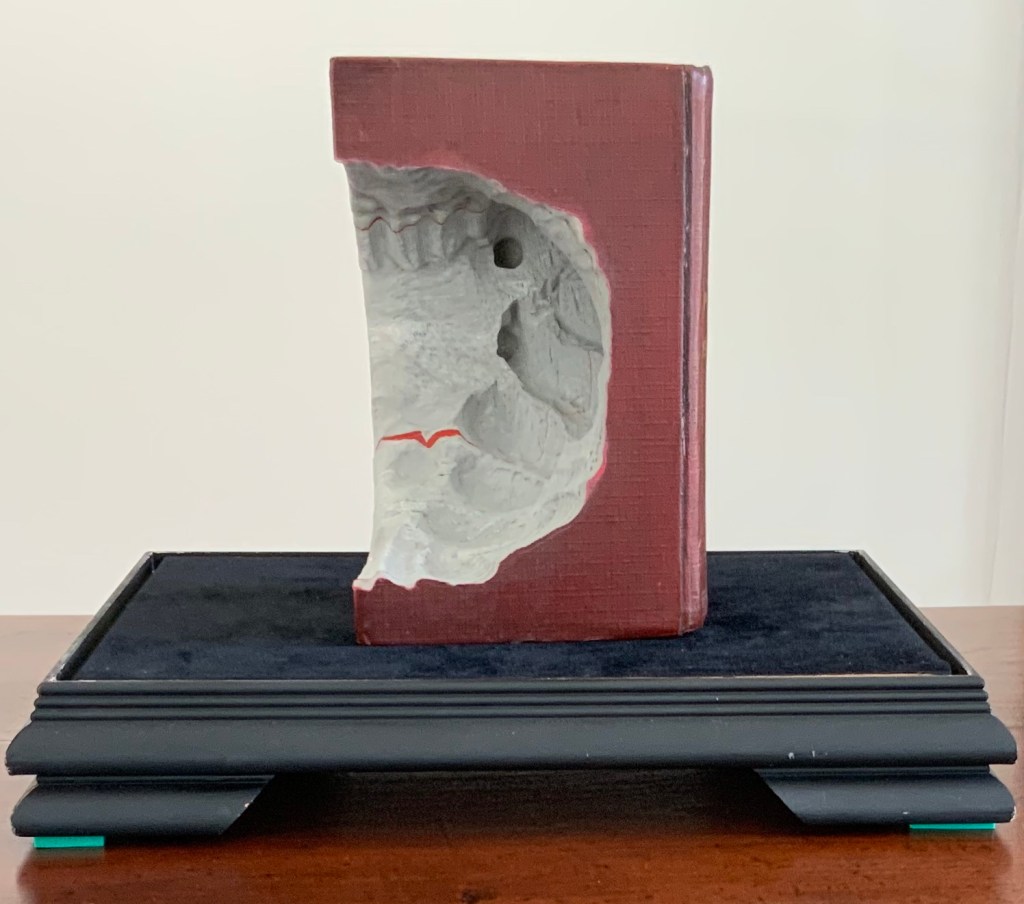

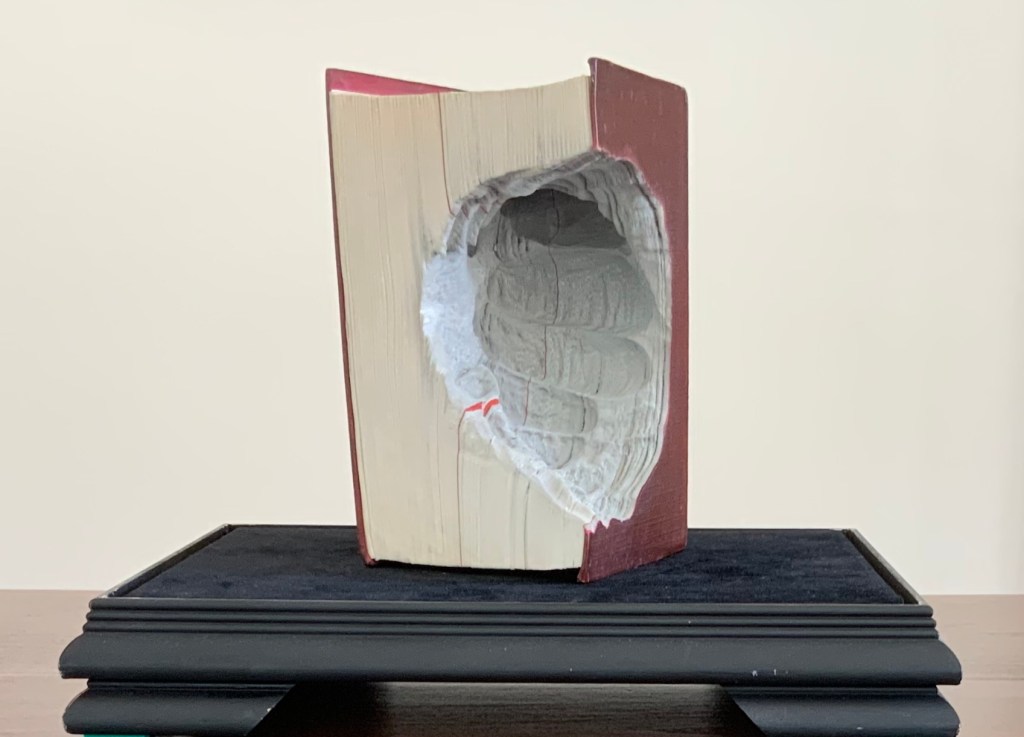

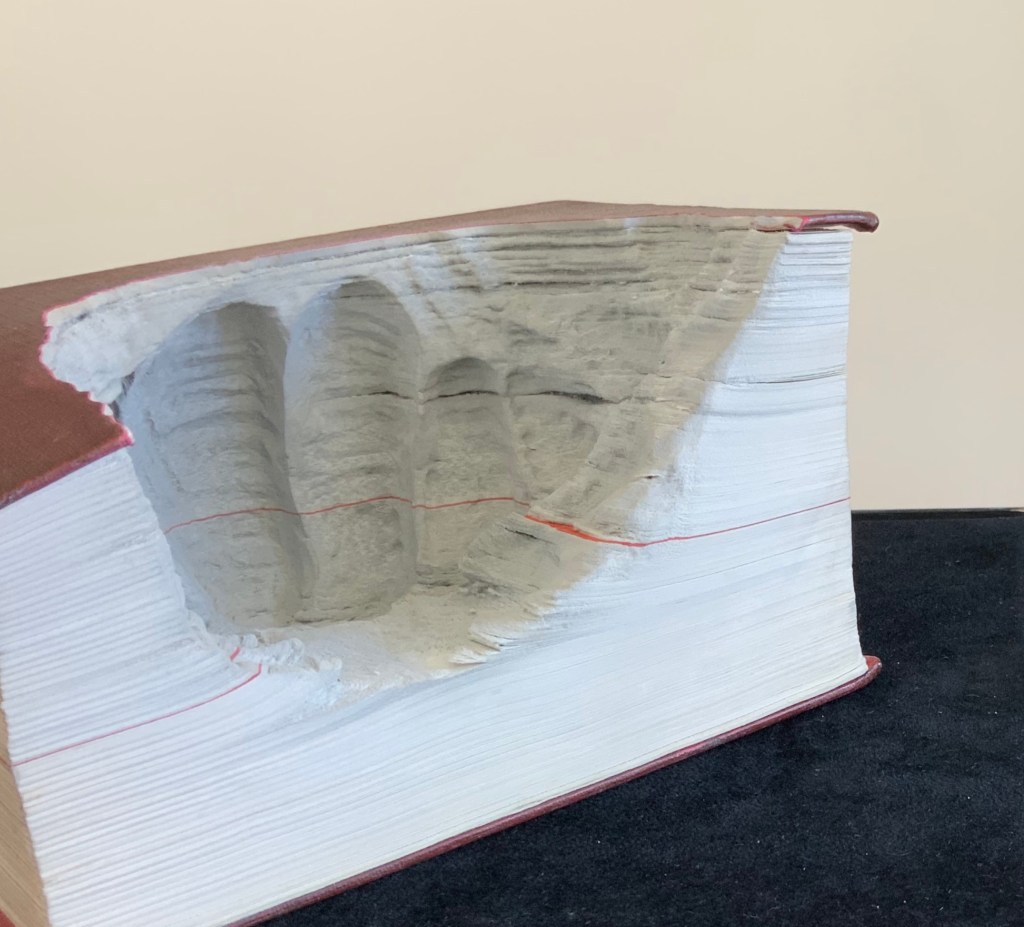

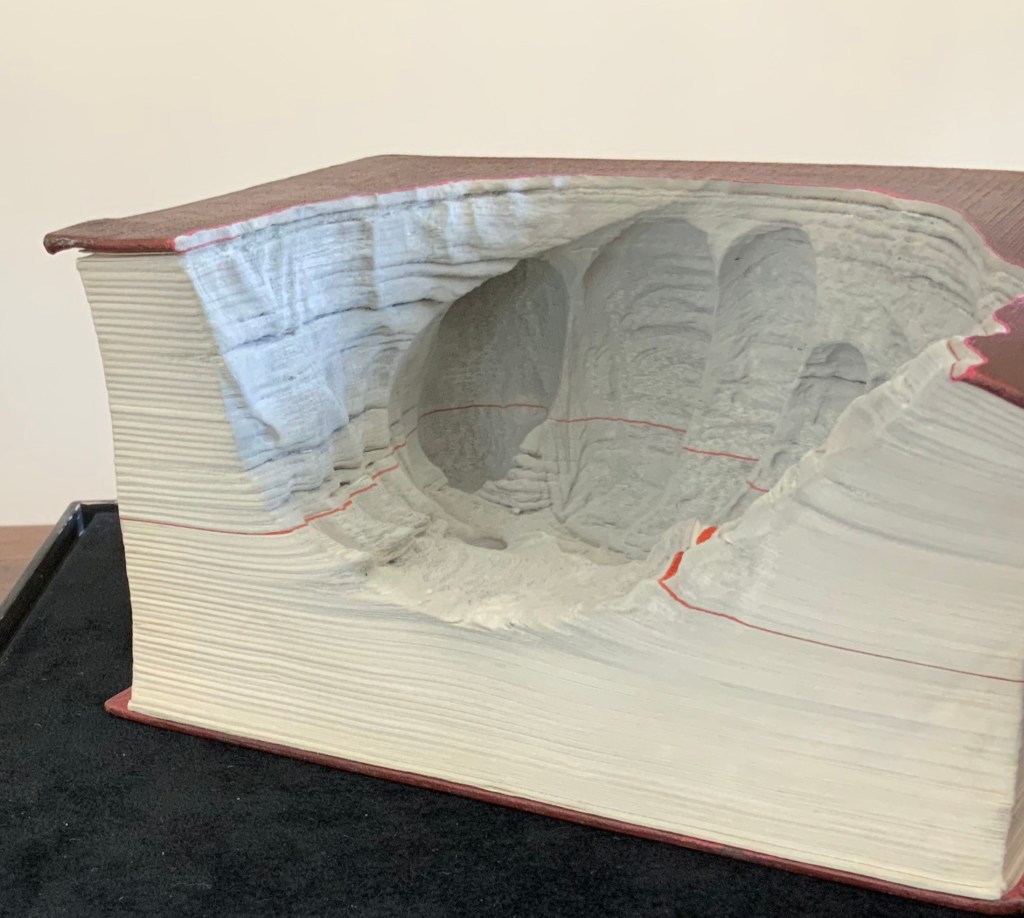

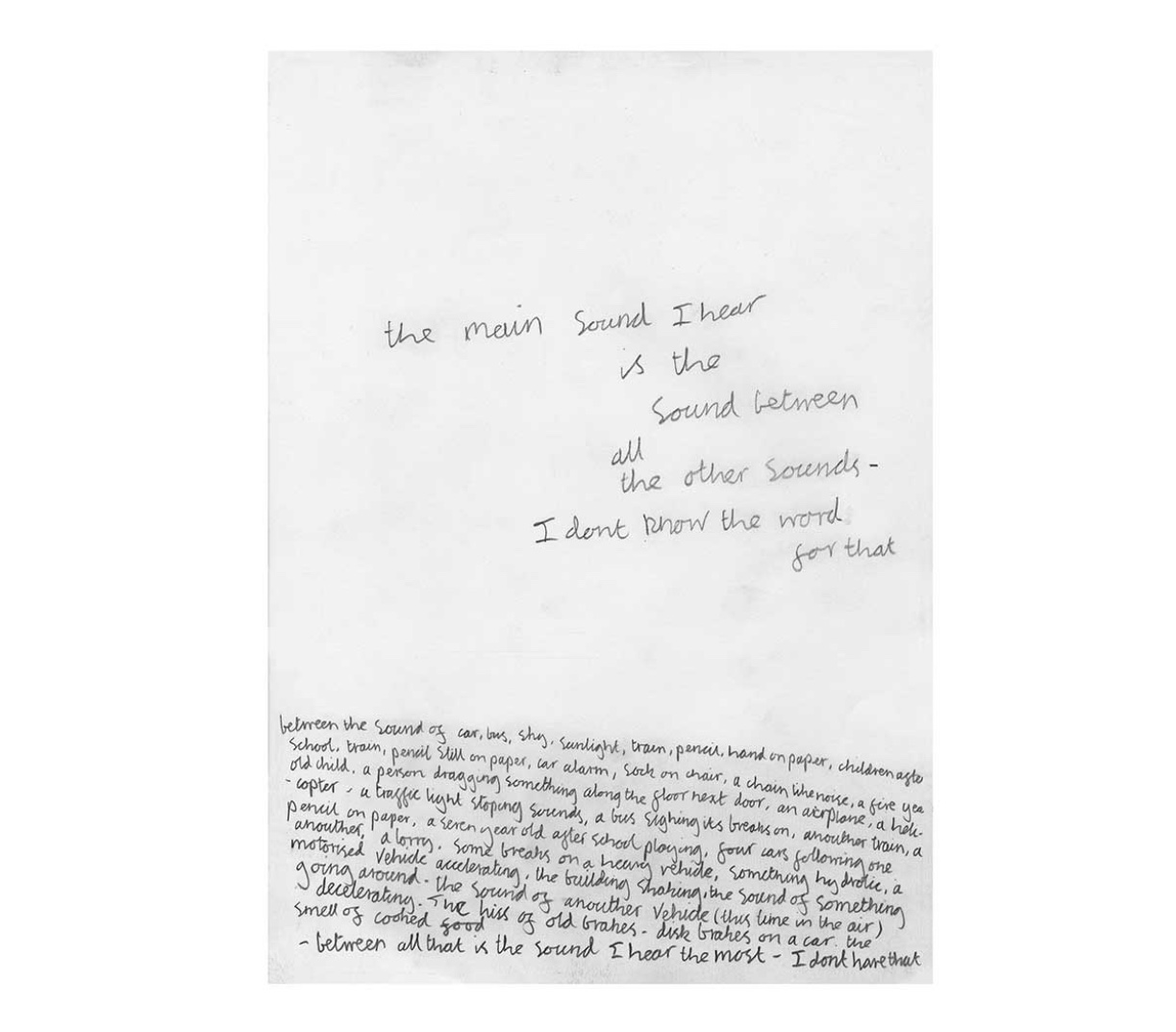

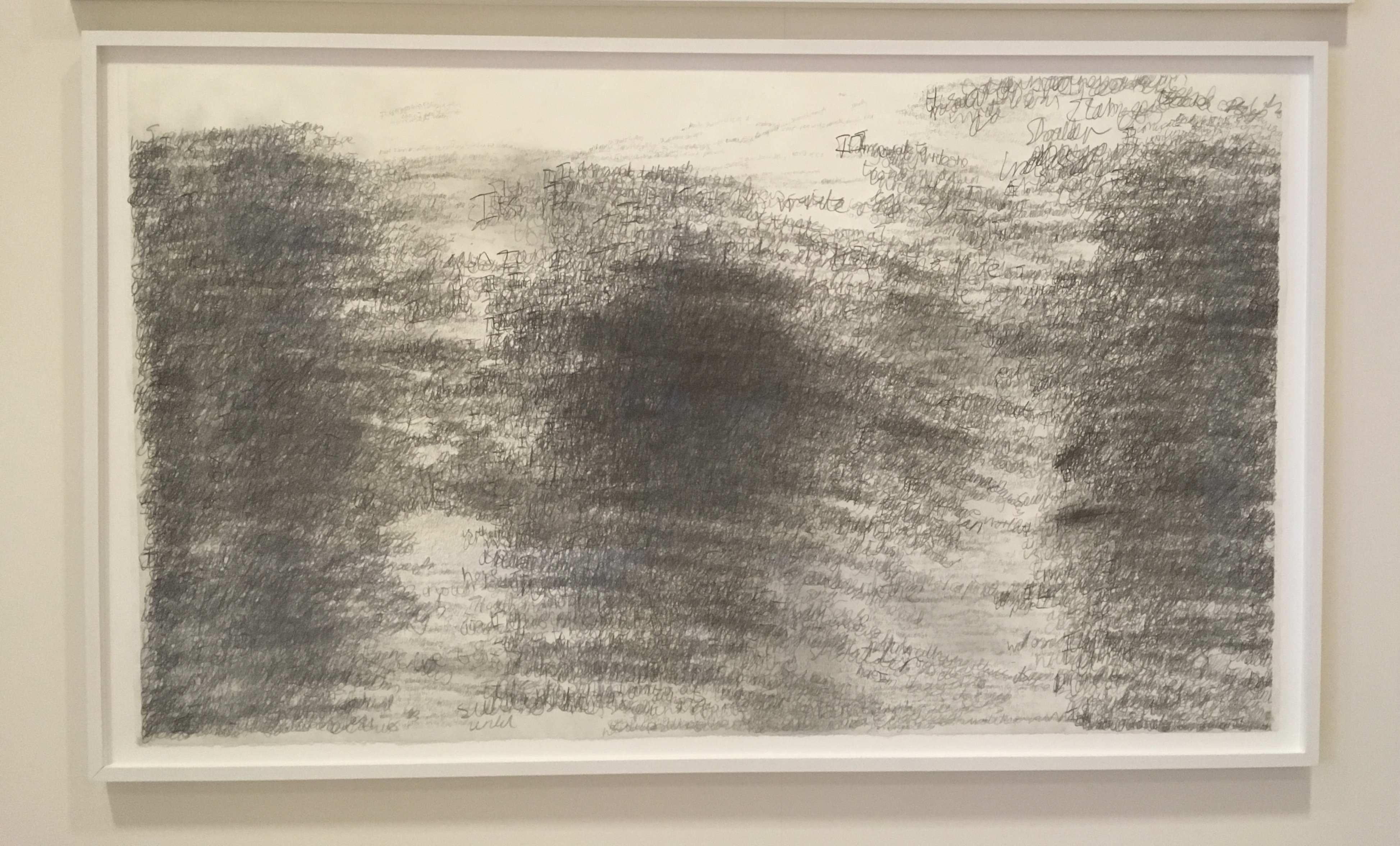

On the Self-Reflexive Page II (2021)

On the Self-Reflexive Page II (2021)

Louis Lüthi

Paperback. H200 x W130 mm. 304 pages. Acquired from Idea Books, 18 September 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

This is a peculiar book in its order and nature. After two variant half-title pages, it begins with a section entitled “Black Pages”. Only on flipping through the volume can we find the remaining front matter — just after page 208. There’s another half-title and then the Table of Contents. Reproducing the marbled page from Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–1767), the book’s cover gives a clue to this peculiarity. Sure enough, Lüthi spells it out later in the section entitled “On Drawing Pages”.

So much in Tristram Shandy is presented out of order: a second dedication comes not after the first but on page 27, the preface is not at the beginning of the novel but in chapter 20 of volume three, and chapters 18 and 19 of volume nine come not after chapter 17 but are inserted after chapter 25. In a similar act of transposition, we find a marbled page in volume three, even though hand marbling is customarily used to decorate covers and endpapers. As Viktor Shklovsky observed, “It is precisely the unusual order of even common, traditional elements that is characteristic of Sterne.” (p. 240)

This one paragraph confers on Lüthi’s entire book the very self-reflexivity that it explores across a range of literature and artists’ books. Reflecting the custom to which it refers, On The Self-Reflexive Page II carries Sterne’s marbled pages on its front and back covers. In the text before his marbled leaf, Sterne refers to it as the “(motly emblem of my work!)“. Lüthi has taken that exclamation to heart (and cover) as if it were advice in creating this hybrid, motley work of his own: “part artist’s book and part essay, part literary excavation and part typographical miscellany” as he calls it in his middle-of-the-book Foreword.

Lüthi’s work is just one in the Books on Books collection of several inspired by Tristram Shandy. There is Erica Van Horn’s Born in Clonmel (2011), Simon Morris’ Do or DIY (2012), Abra Ancliffe’s The Secret Astronomy of Tristram Shandy (2015), and Shandy Hall‘s The Black Page Catalogue (2010), Emblem of My Work (2013), Paint Her To Your Own Mind (2018) and The Flourish of Liberty (2019). Outside the collection, there is Brian Dettmer’s Tristram Shandy (2004), commissioned by Shandy Hall’s Laurence Sterne Trust, and also Sean Silver’s Shandean online venture called The Motley Emblem (2022~) celebrating Sterne’s marbled leaf and the analytical chemistry of marbling. The latter may become a book, even an artist’s books to add to the tally. In The Century of Artists’ Books, Johanna Drucker draws attention to Sterne’s novel twice as an example of self-reflexivity or self-interrogation, but in 1994 and 2004, Sterne did not rise to the same level of precursor to book artists as William Blake or Stéphane Mallarmé in Drucker’s view. With these later works of book art inspired by Uncle Toby’s nephew in the bag, a dozen or so more might nudge Sterne up the scale.

In the meantime, anyone interested in artists’ books could fruitfully apply to the medium Sterne’s exhortation to his own readers:

Read, read, read, read, my unlearned reader! read, — or by the knowledge of the great faint Paraleipomenon — I tell you before-hand, you had better throw down the book at once; for without much reading , by which your reverence knows, I mean much knowledge, you will no more be able to penetrate the moral of the next marbled page (motly emblem of my work!) than the world with all its sagacity has been able to unraval the many opinions, transactions and truths which still lie mystically hid under the dark veil of the black one.

Artists’ books are to be read, handled and digested, not stored away in the archives.

Further Reading

“The First Seven Books of the Papier Biënnale Rijswijk“. 10 October 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Maureen Richardson“. 28 September 2019. Books On Books Collection.

Silver, Sean. 2022~. The Motley Emblem. Rutgers: Rutgers University. A website that celebrates Sterne, paper marbling and much more related to them.