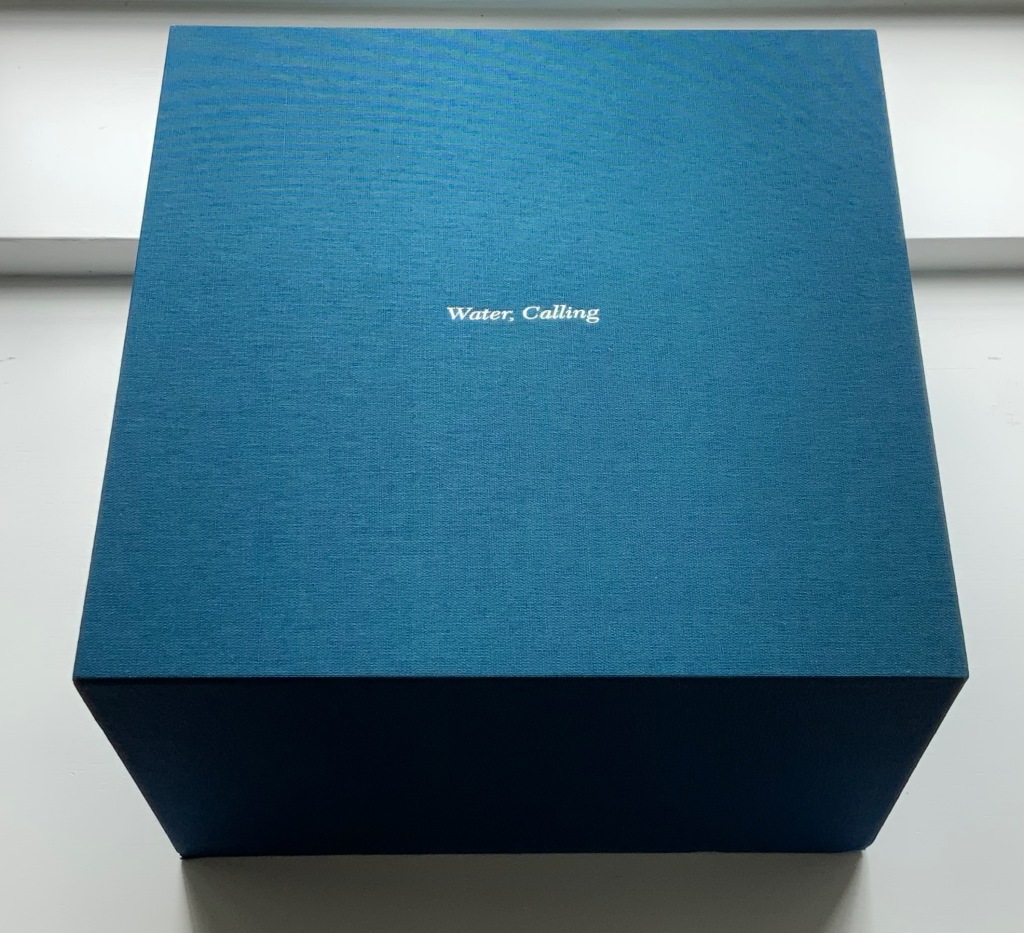

Water, Calling (2021)

Water, Calling (2021)

Camden Richards & Deborah Sibony

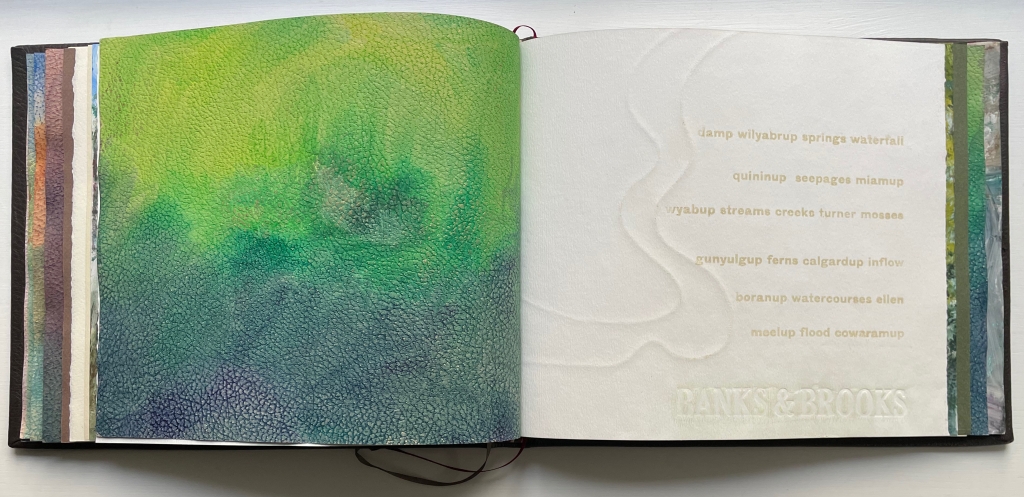

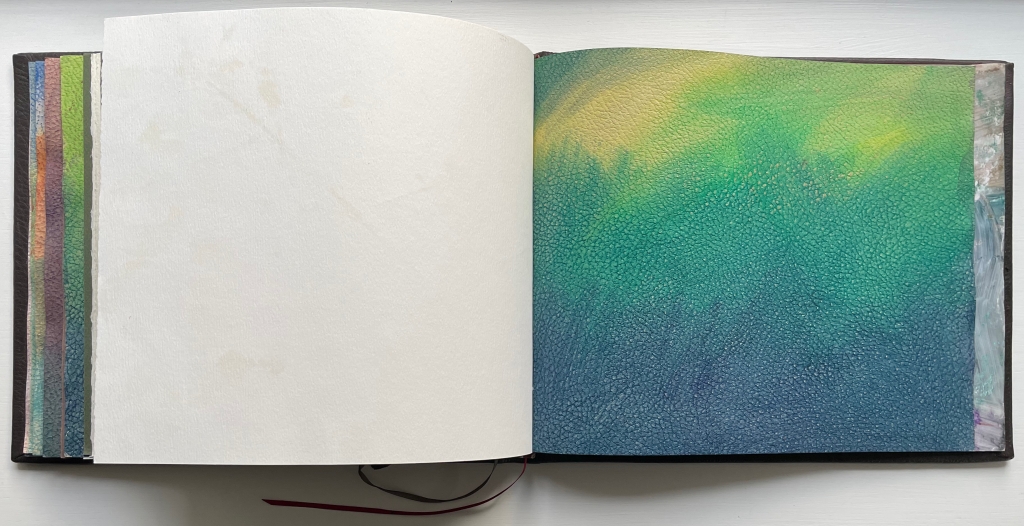

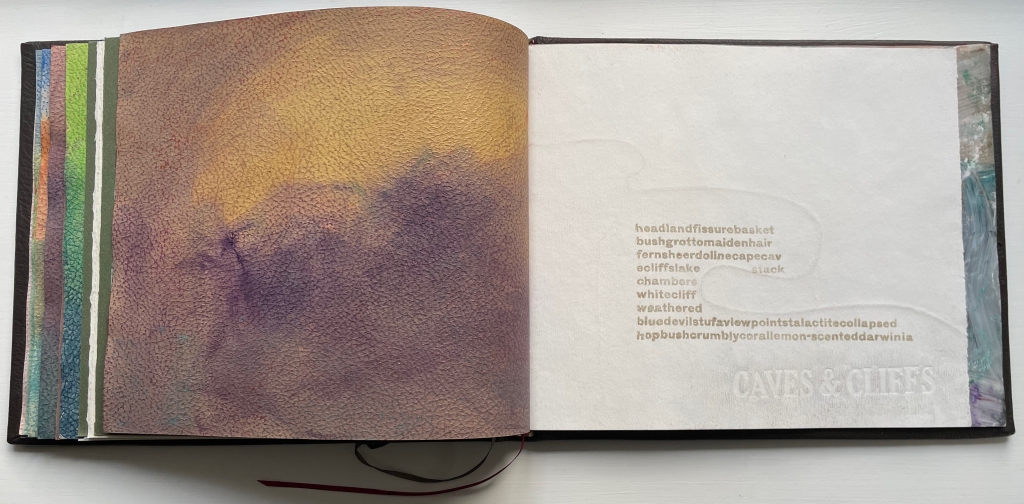

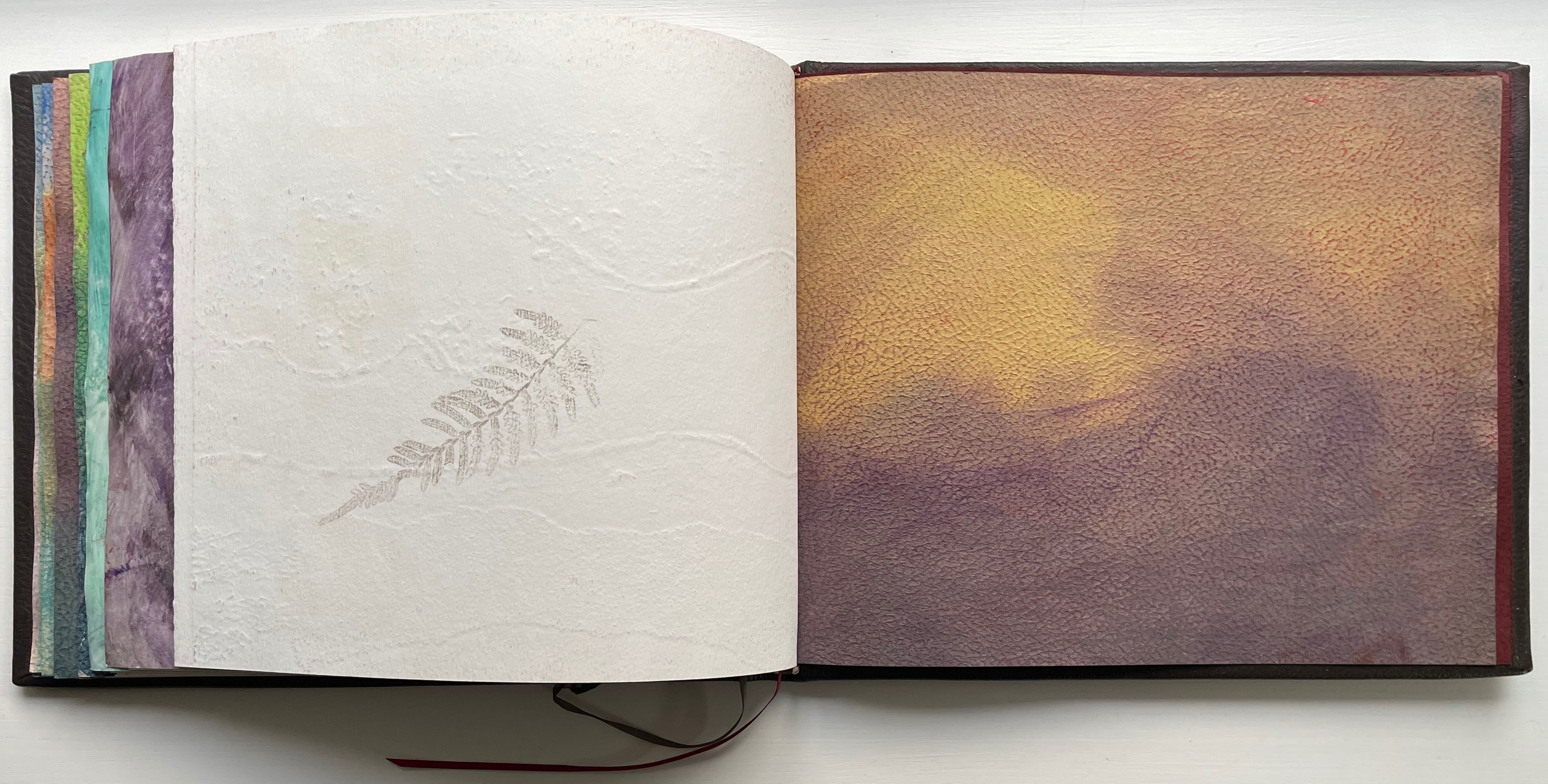

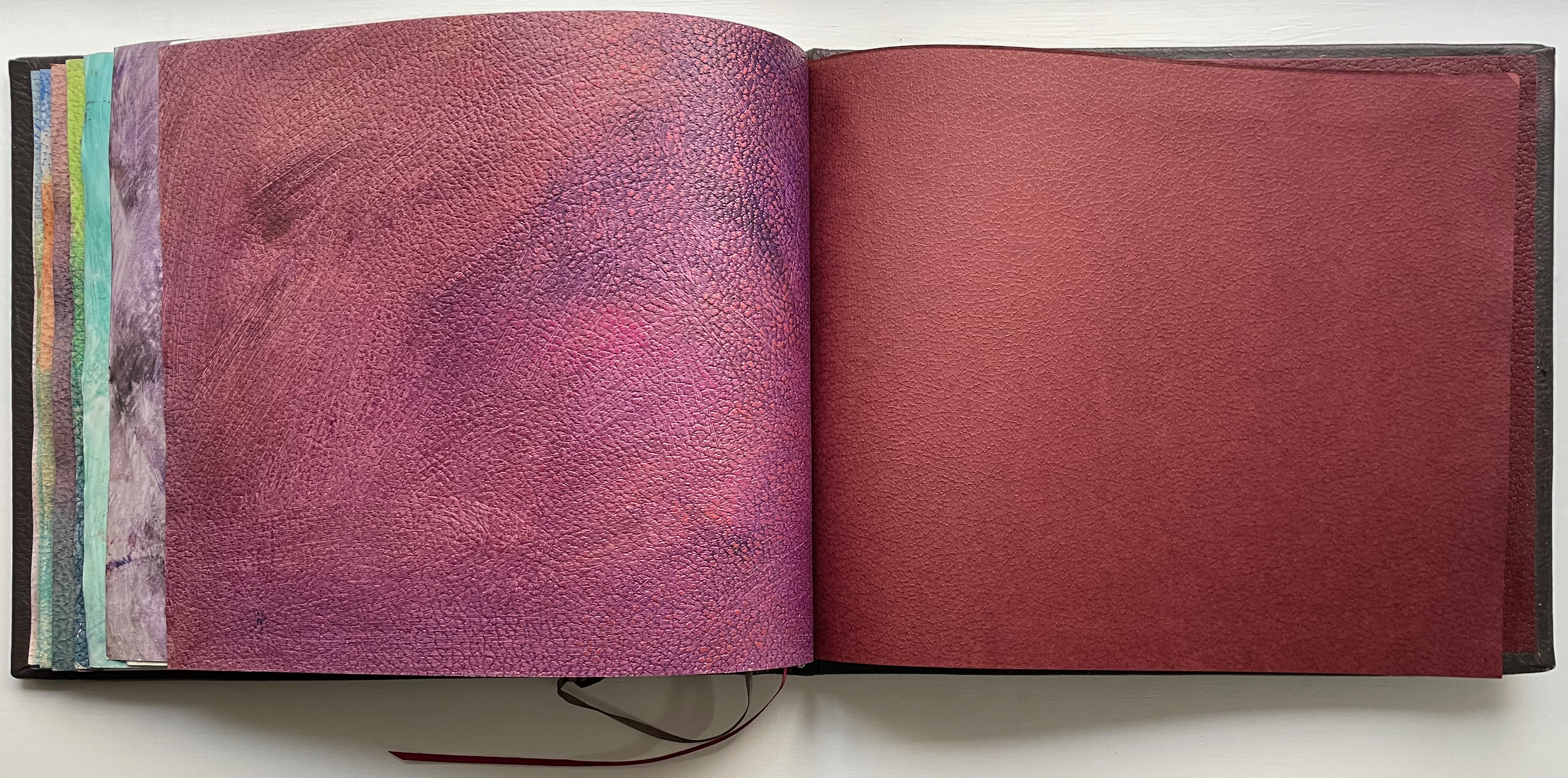

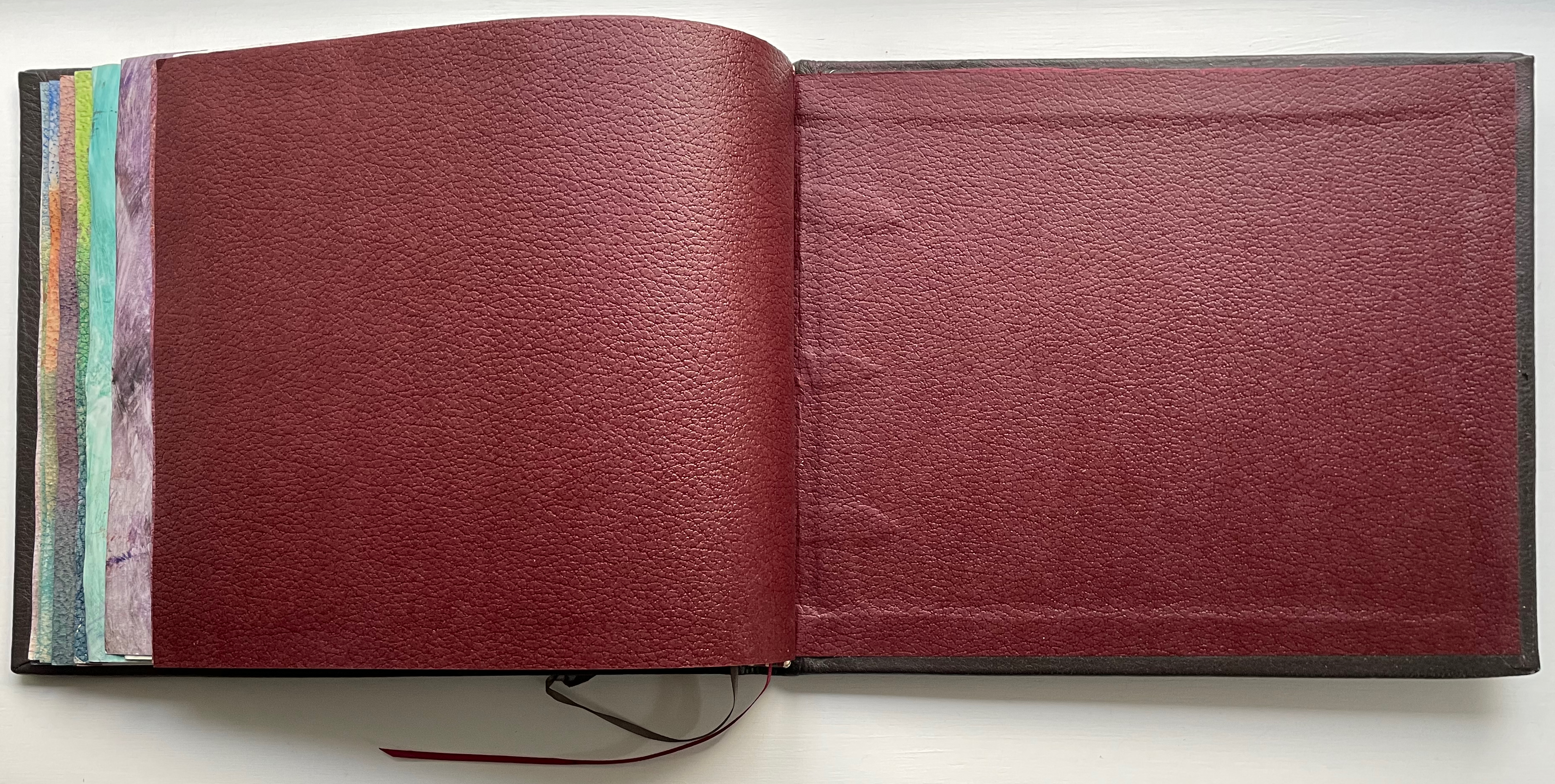

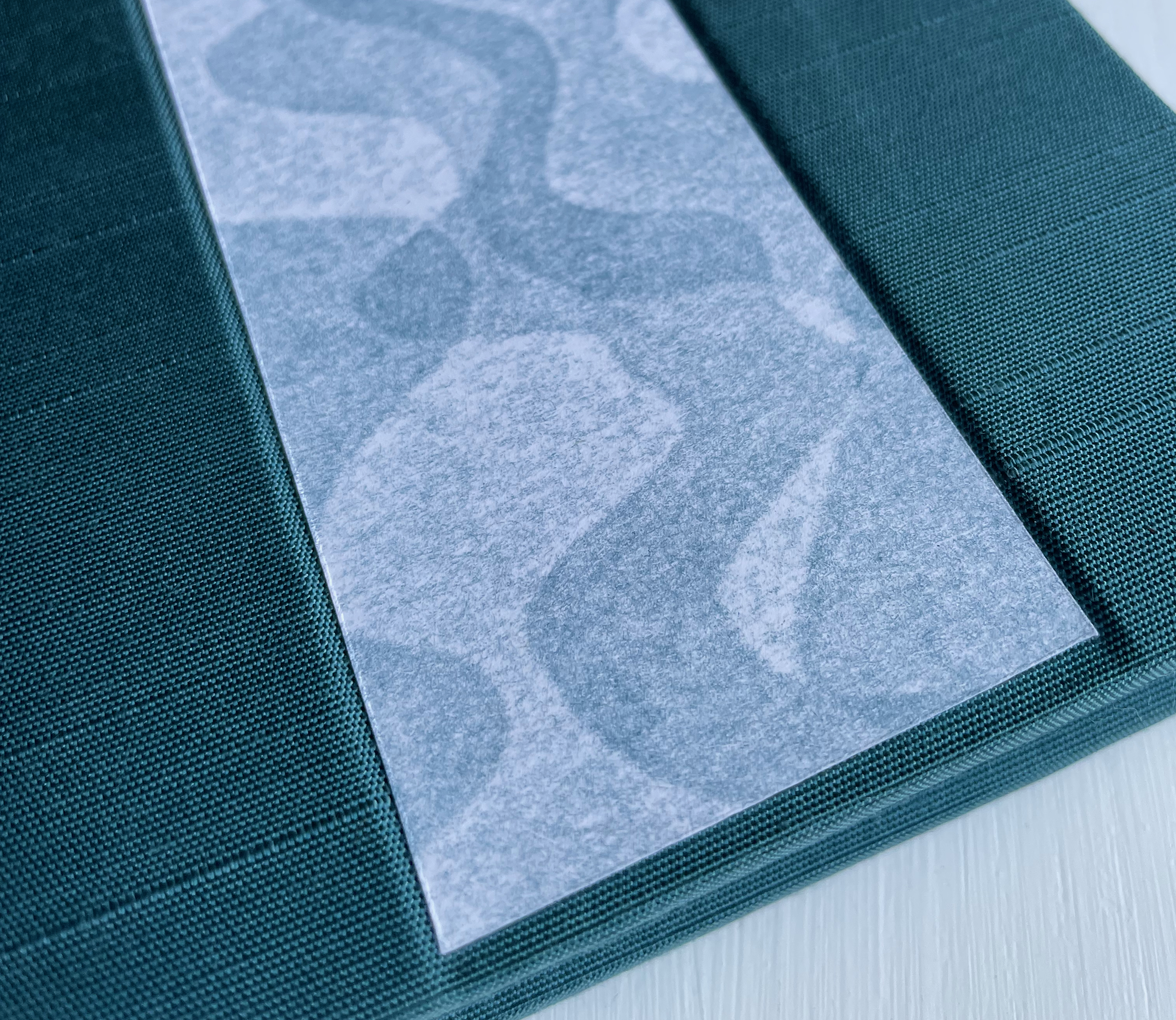

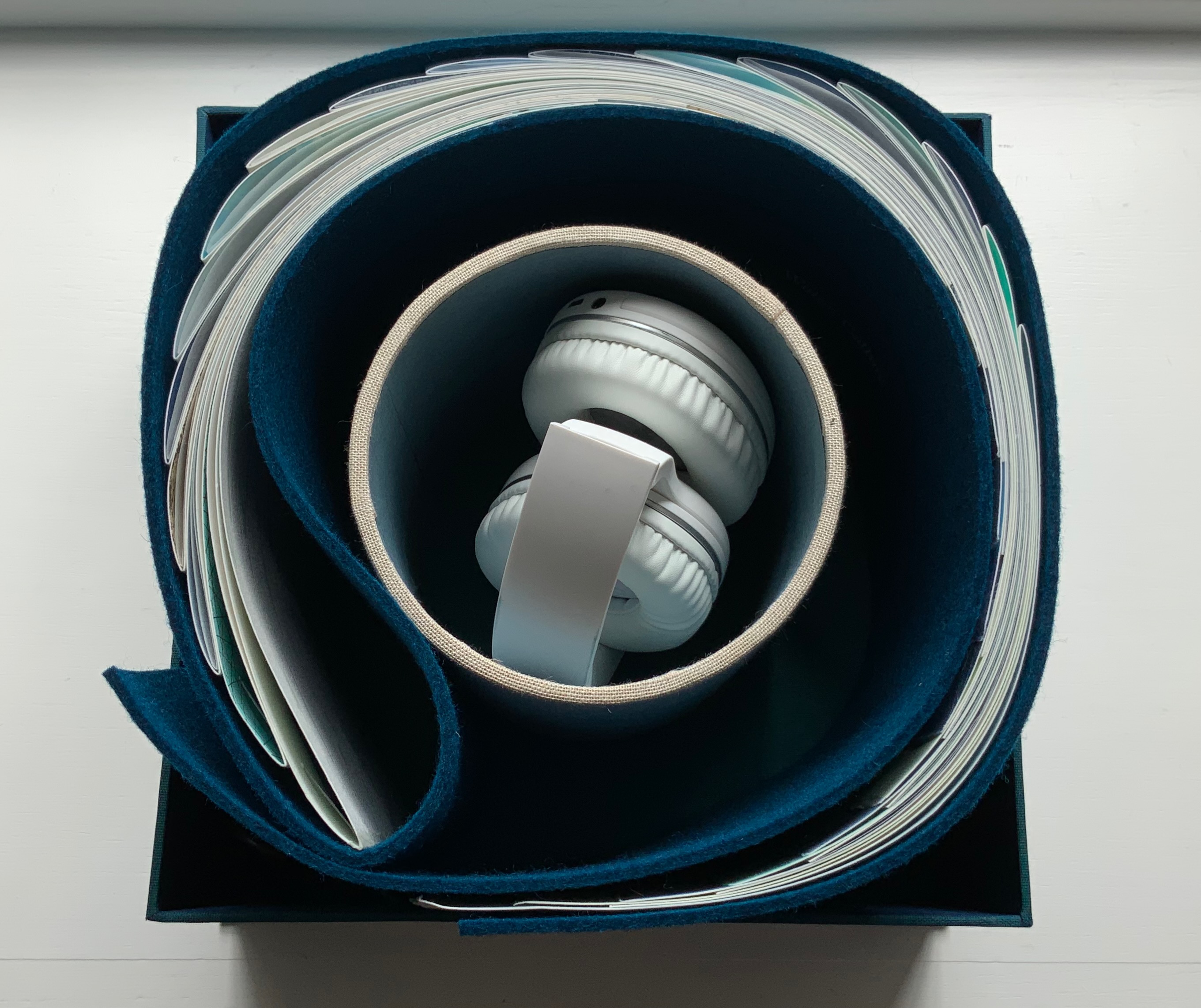

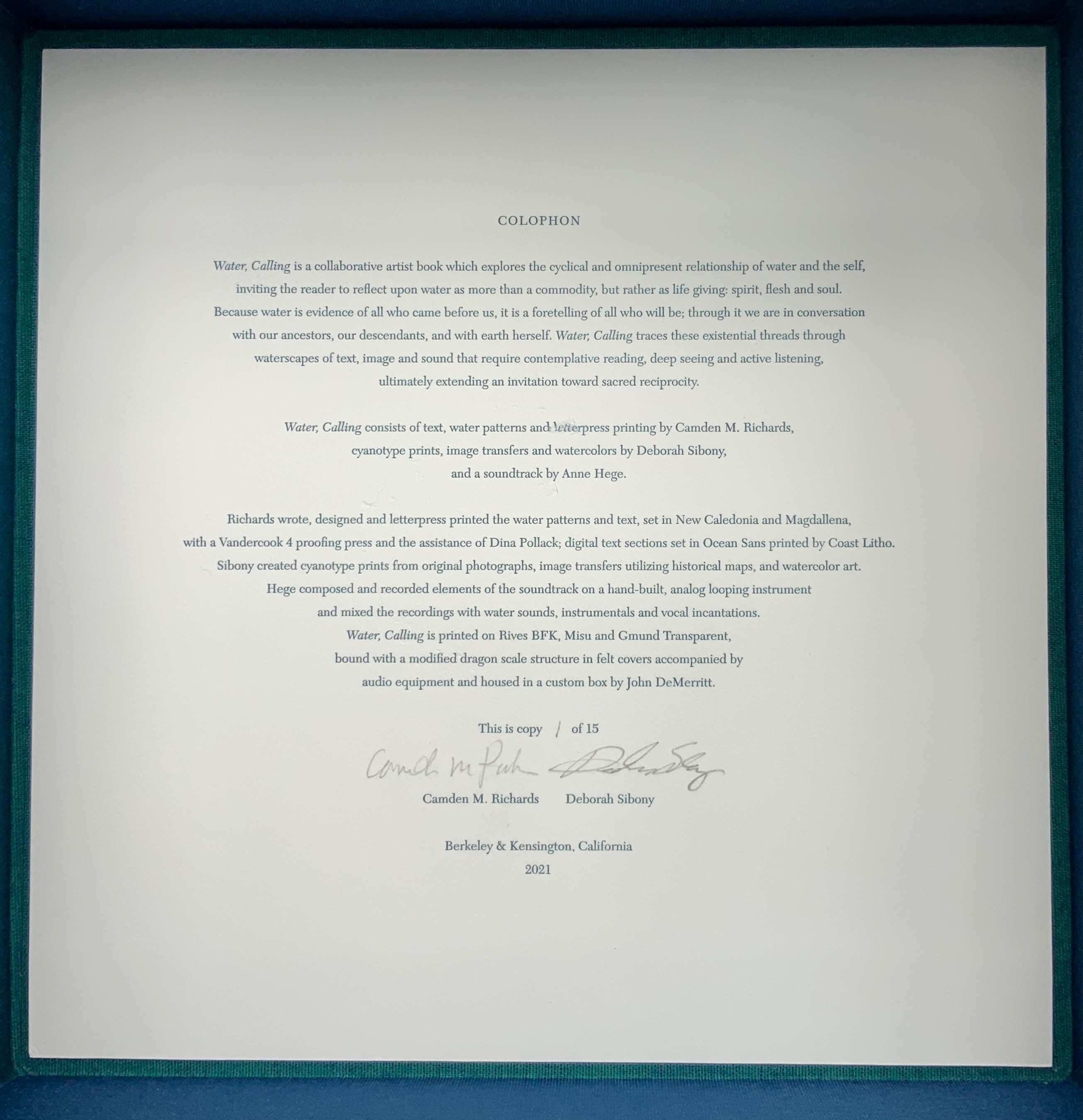

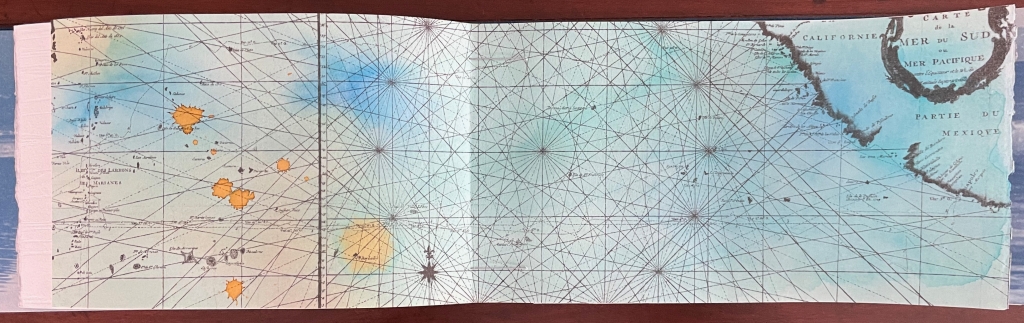

Felt-covered, modified dragon-scale bound artists’ book, accompanied by audio equipment in custom box. Box: 262 x 262 x D170 mm. Book: H155 x W775 mm (closed). 110 pages. Edition of 15, of which this is #1. Acquired from the artists, 5 October 2022. Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artists’ permission.

Colophon

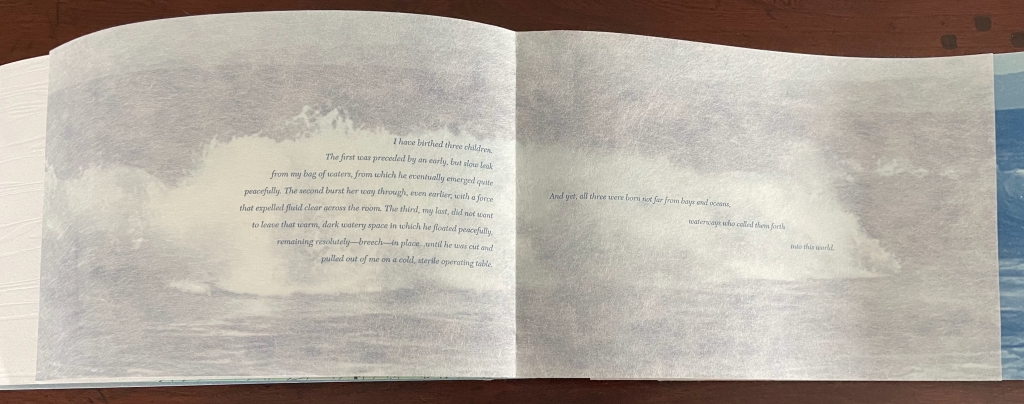

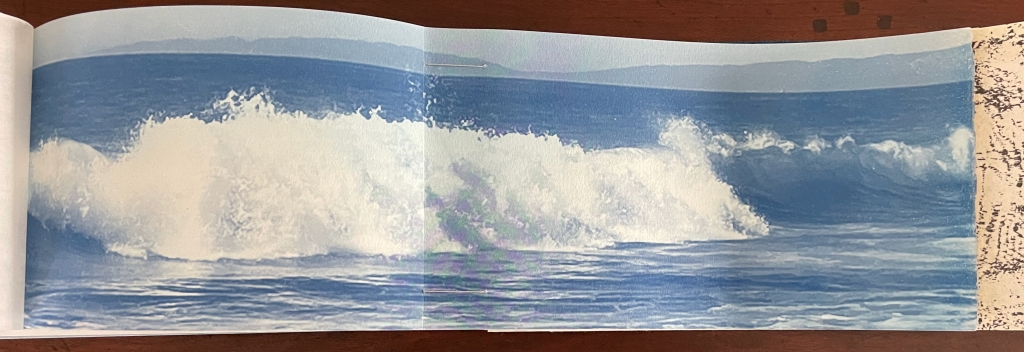

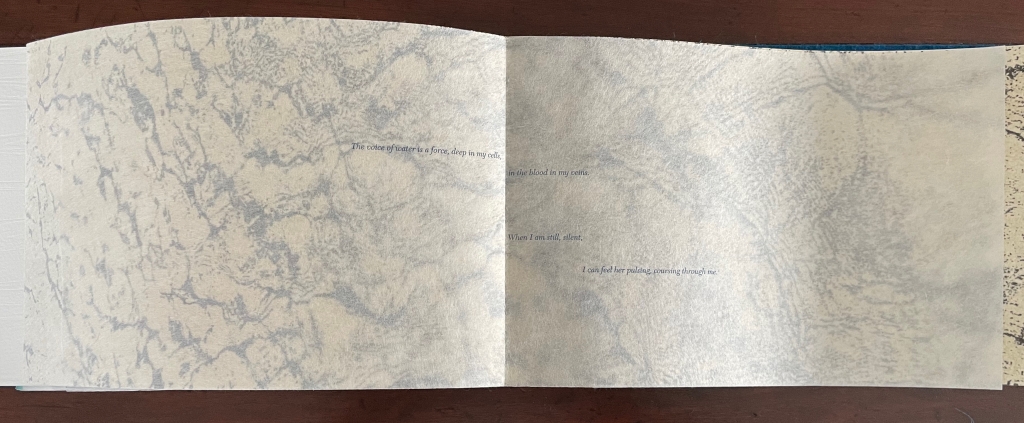

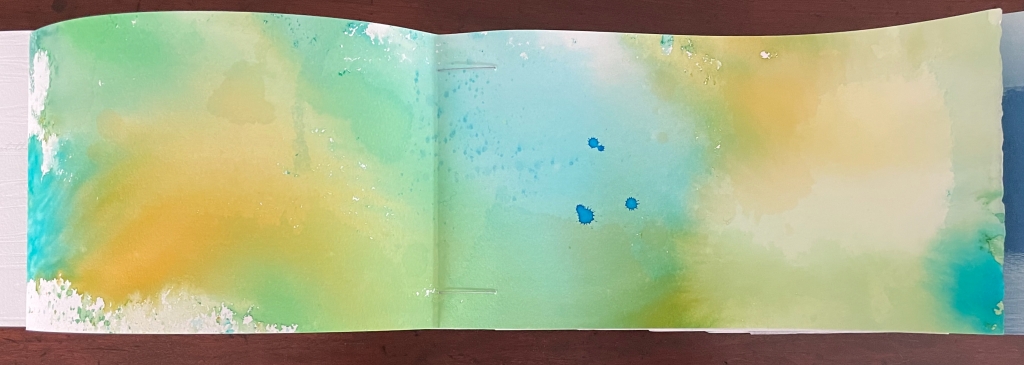

“Water, Calling is a collaborative artist book which explores the cyclical and omnipresent relationship of water and the self, inviting the reader to reflect upon water as more than a commodity, but rather as life giving: spirit, flesh and soul. Because water is evidence of all who came before us, it is a foretelling of all who will be; through it we are in conversation with our ancestors, our descendants, and with earth herself. Water, Calling traces these existential threads through waterscapes of text, image and sound, extending an invitation to enter more fully into a dialogue composed of acts requiring active listening, contemplative reading and deep seeing with the hope of inspiring sacred reciprocity.”

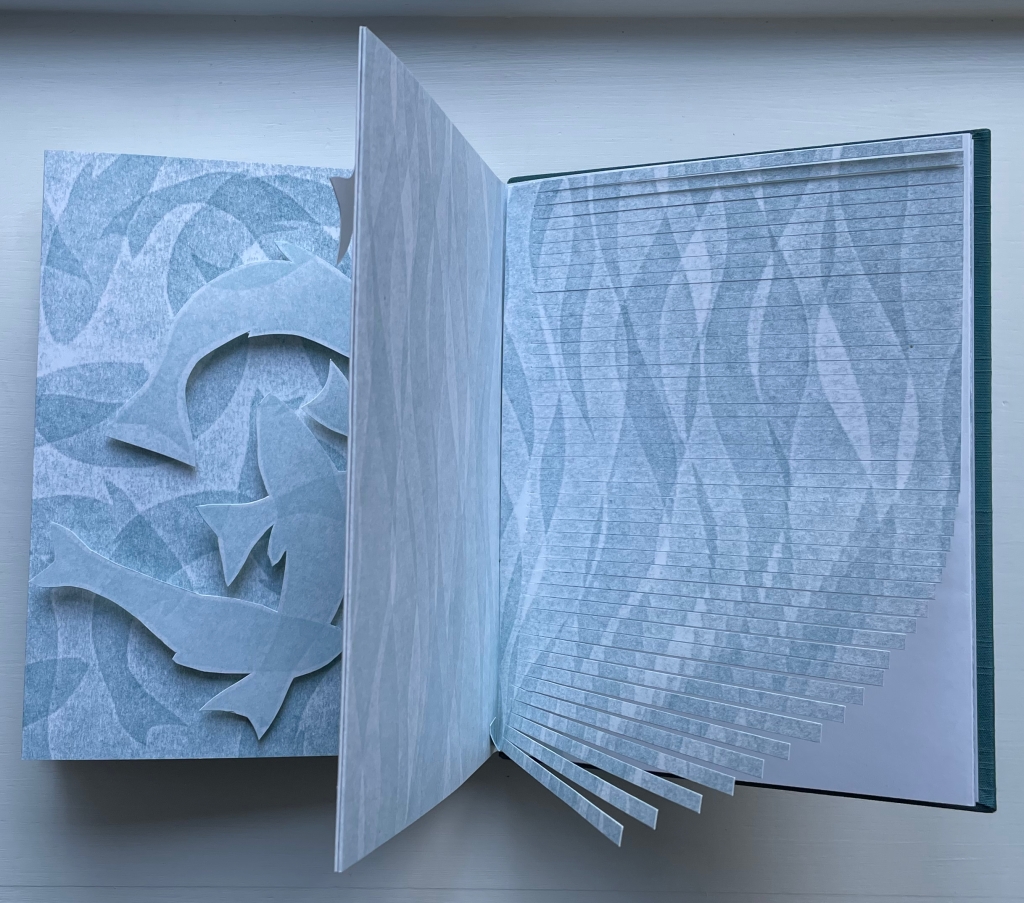

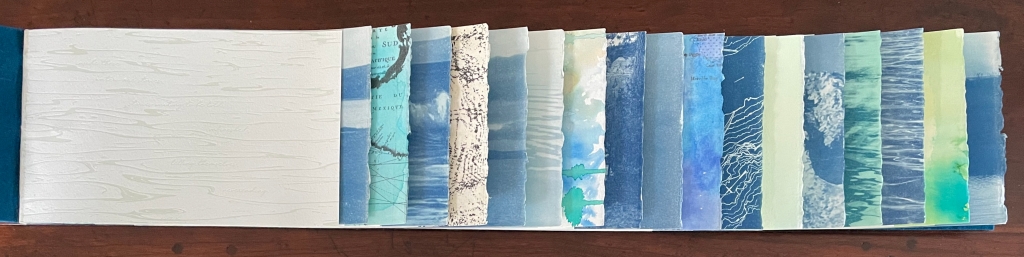

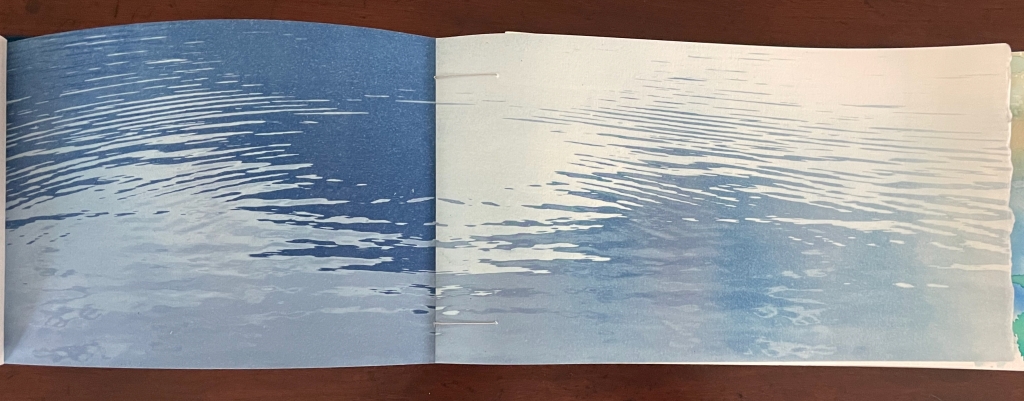

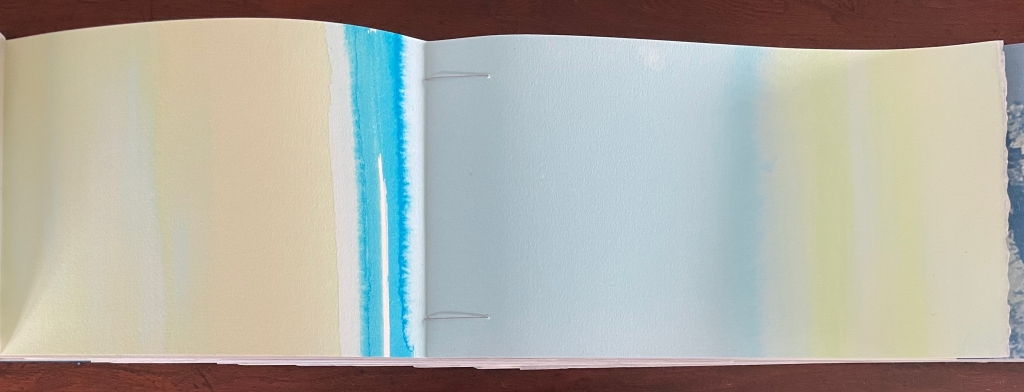

The initial attraction of Water, Calling was its modified “dragon-scale” binding (Chinese: longlin zhuang 龍鱗裝). Its lasting attraction has been how the binding and the structure within it join with the text, images, textures and sound to create this work of art so evocative of the element water.

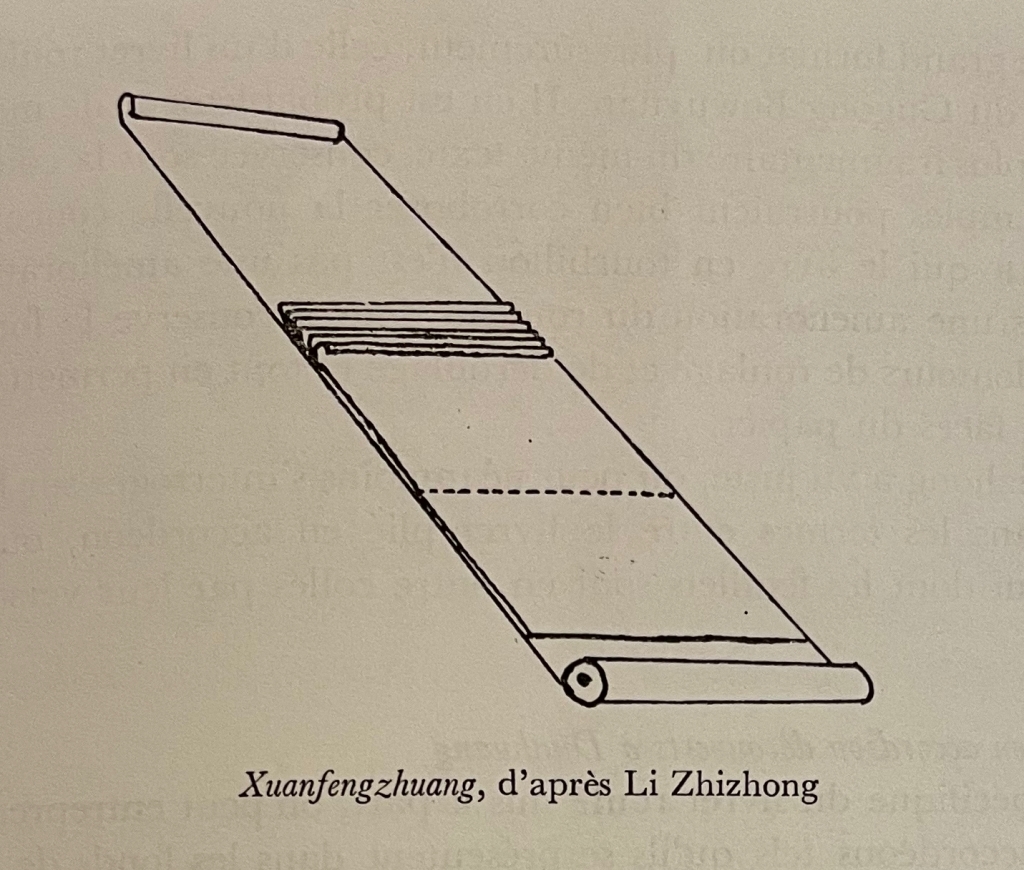

Water, Calling‘s dragon-scale binding is a modified form of the method used with Chinese manuscripts in the 8th century CE and in the oldest printed book known — the Diamond Sūtra, dating back to 868 CE and found in the caves near Dunhuang, China in 1900. In the original structure, sheets of paper of different widths overlap one another with the narrowest on top and the widest on the bottom. They are aligned and attached along the left or right edge, and from the attached edge, the overlapping stack of leaves rolls into a scroll. Below are images from various sources (Drège, Song, and Chinnery).

Drège. Figure unnumbered (p. 197) and Plate XXIV (p. 205).

Song. Fig. 2 Diagrams of whirlwind bindings (top) ‘concertina’ xuanfeng zhuang (旋風裝) and (bottom) ‘dragon scale’ longlin zhuang (龍鱗裝).

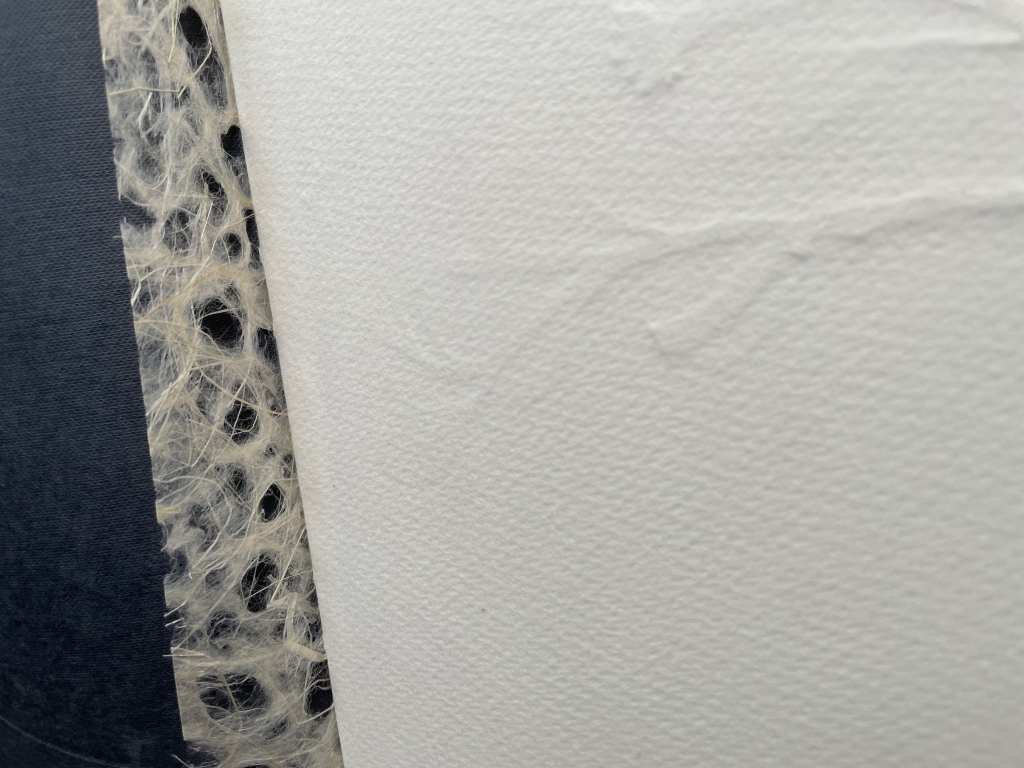

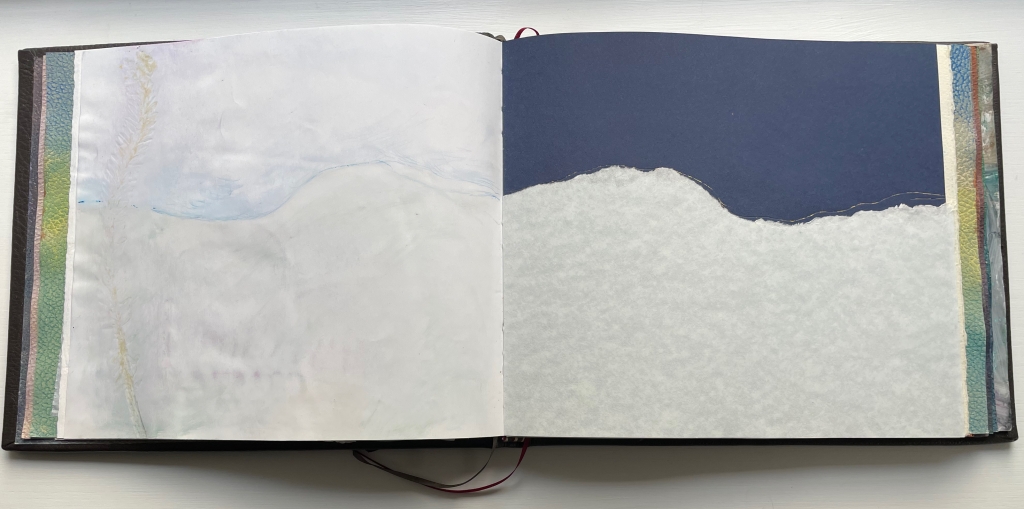

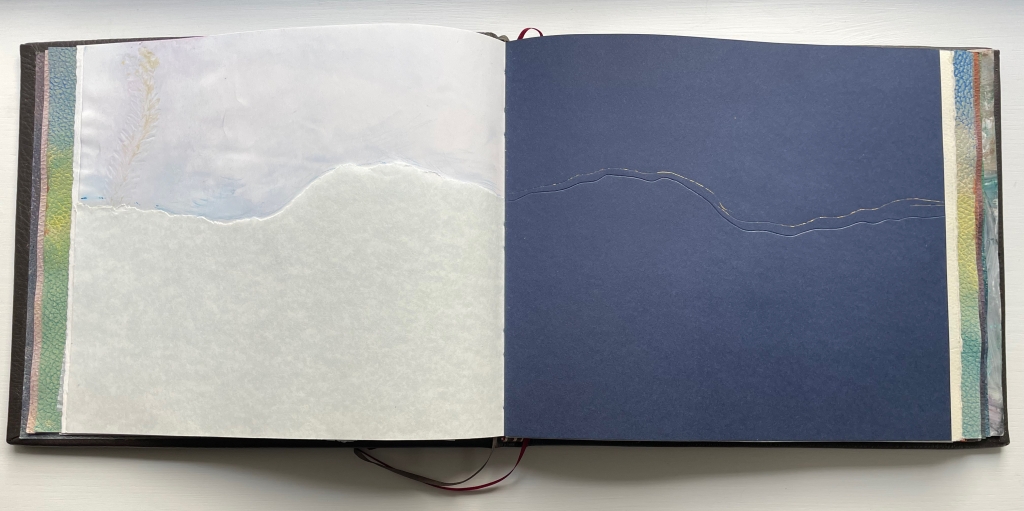

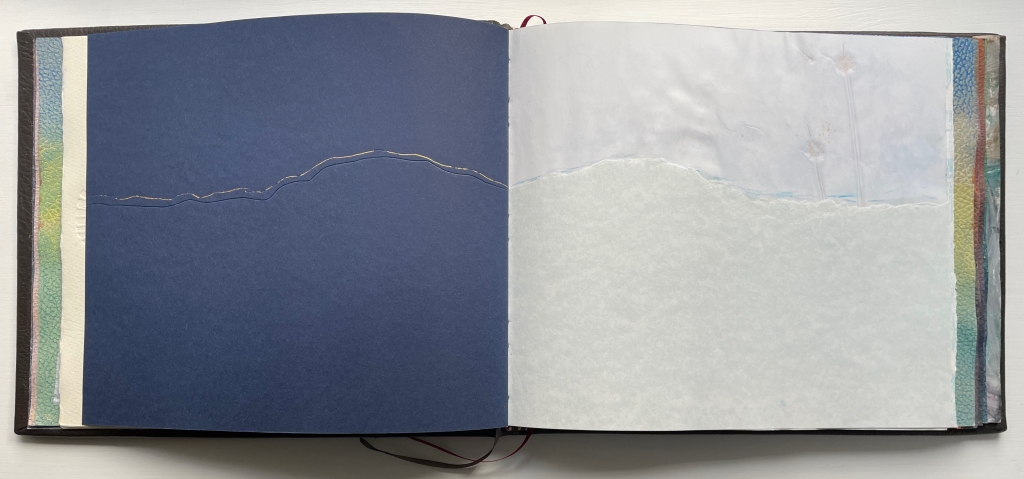

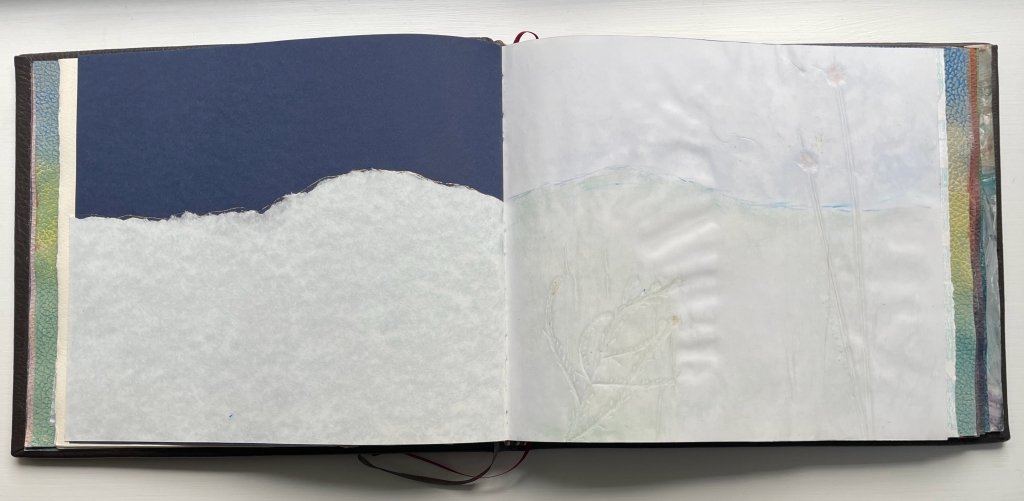

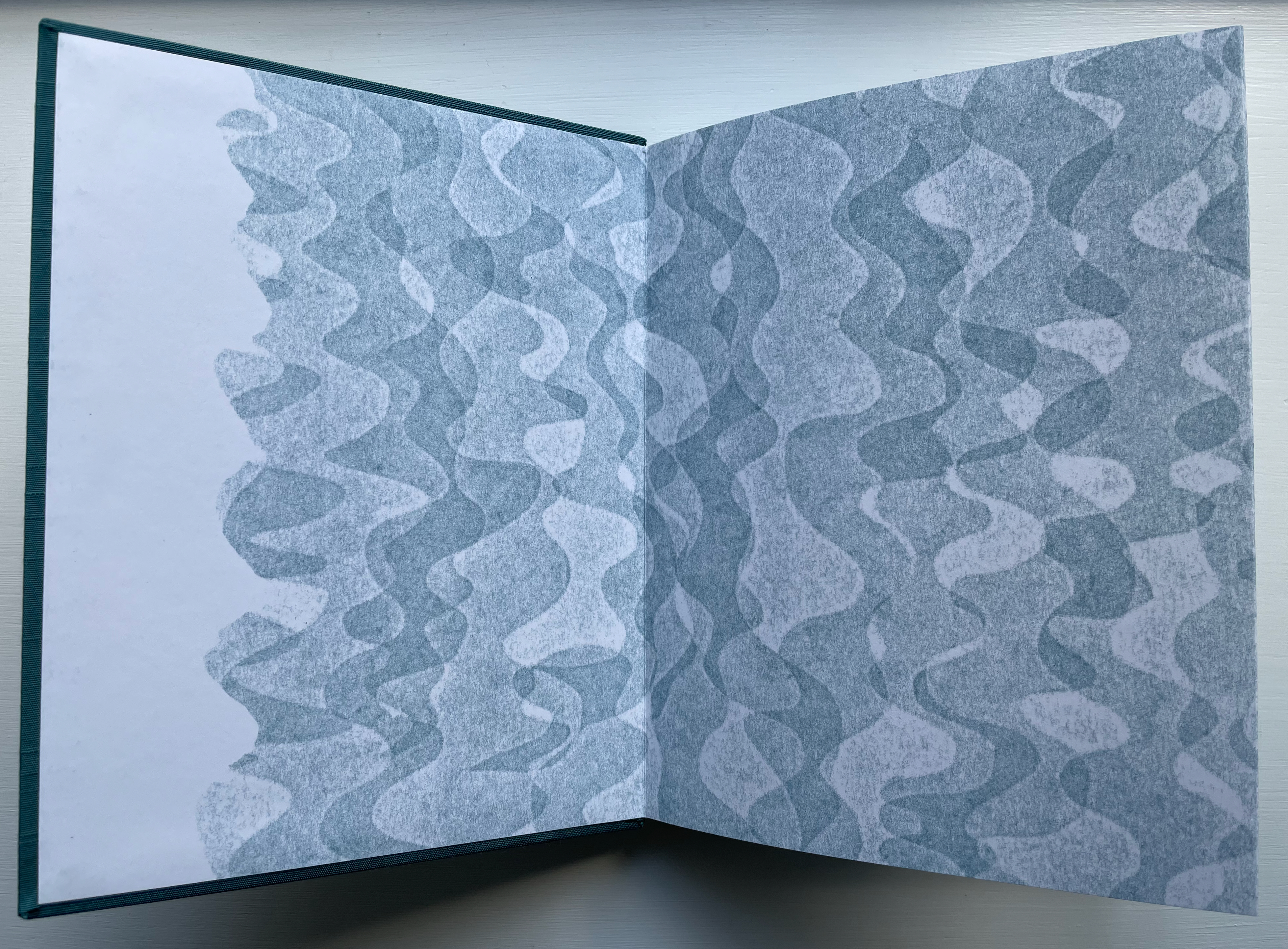

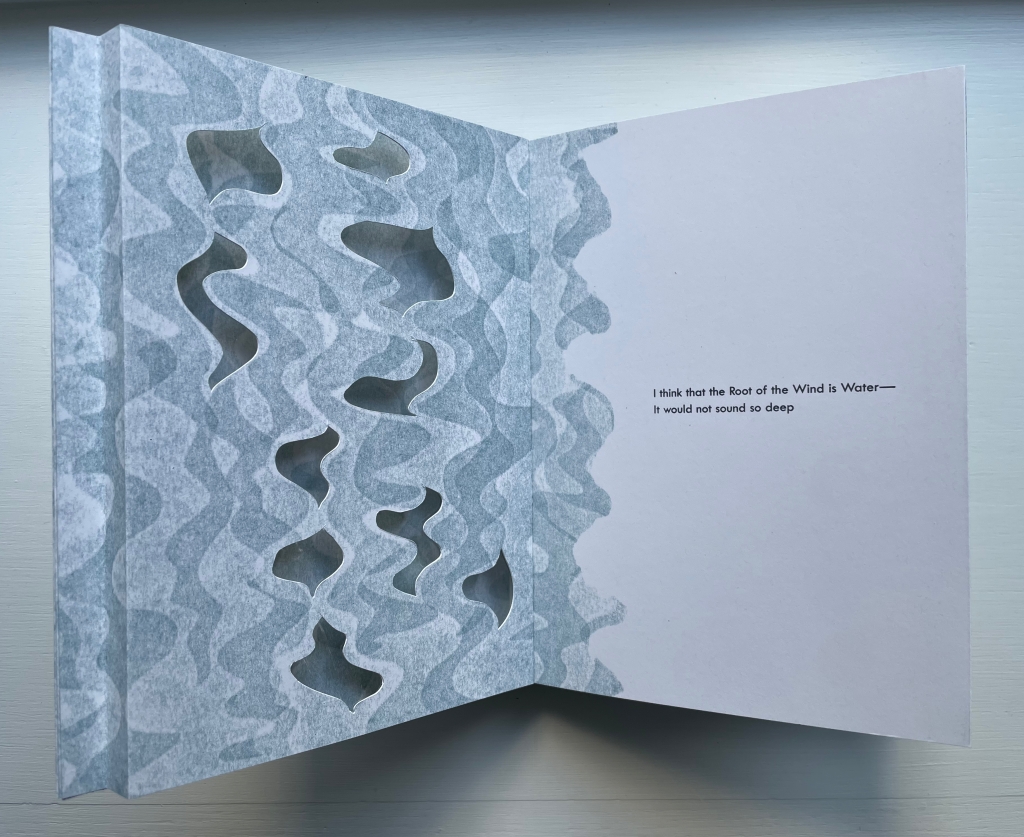

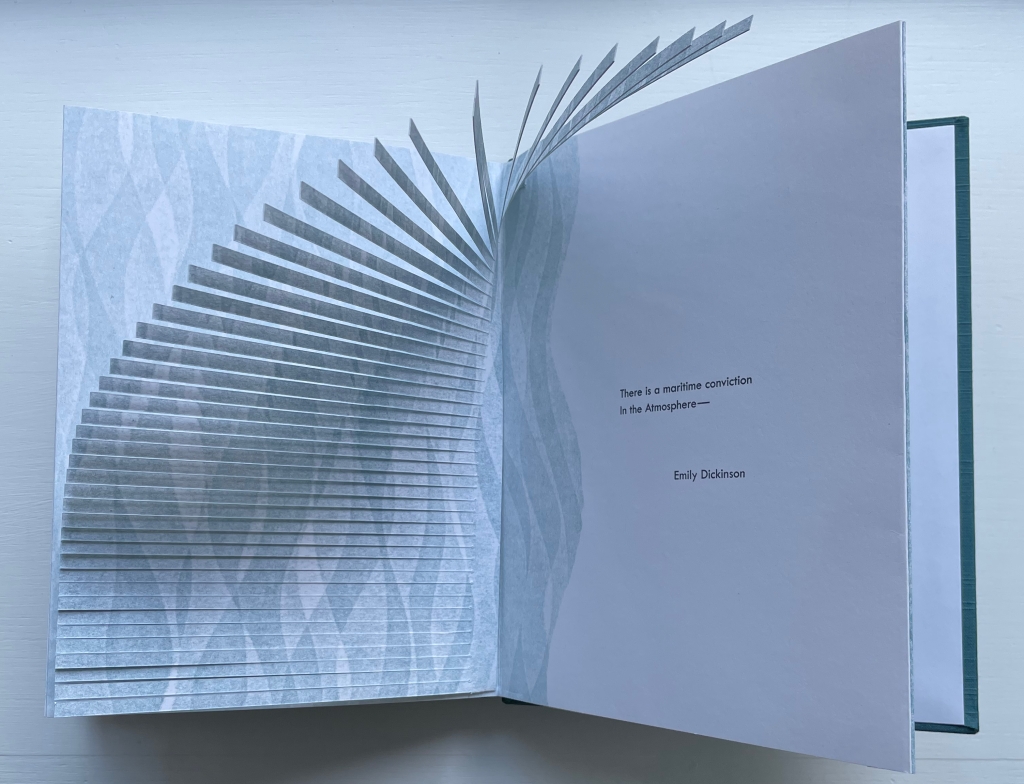

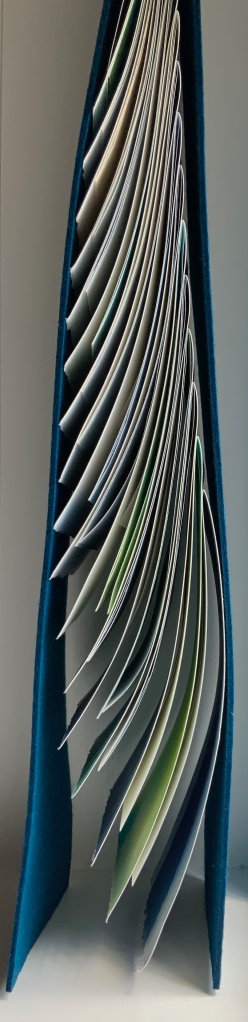

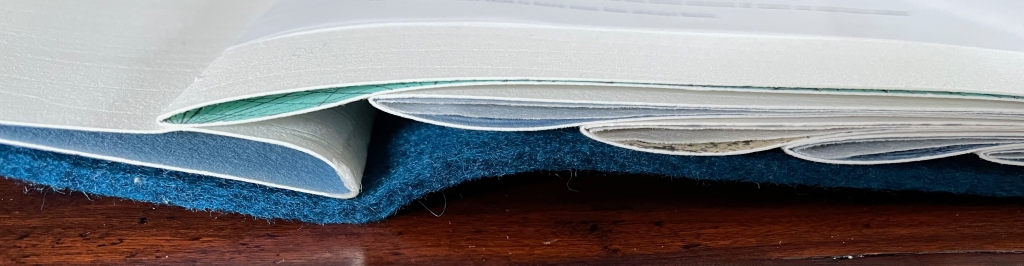

Historically the dragon scale seems to occupy a transitional stage between scroll and codex, and the latter seems to inspire most of the modifications of the dragon scale in Water, Calling. Its dragon-scale-like overlapping occurs within each of seventeen codex-like signatures and across them. There is, however, no single widest sheet. The dragon-scale’s characteristic curling, outlying edge occurs due to a staggered fold of one leaf in each signature. The first signature, below with its the first page and edge of its third page showing, is a single-fold leaf that anchors the book block to the long felt cover. As the first signature’s last page is turned to the left, it pulls all of the next sixteen signatures with it. Viewed from the edge in the third image below, the staggered and overlapping signatures mimic waves of water (see the third image below).

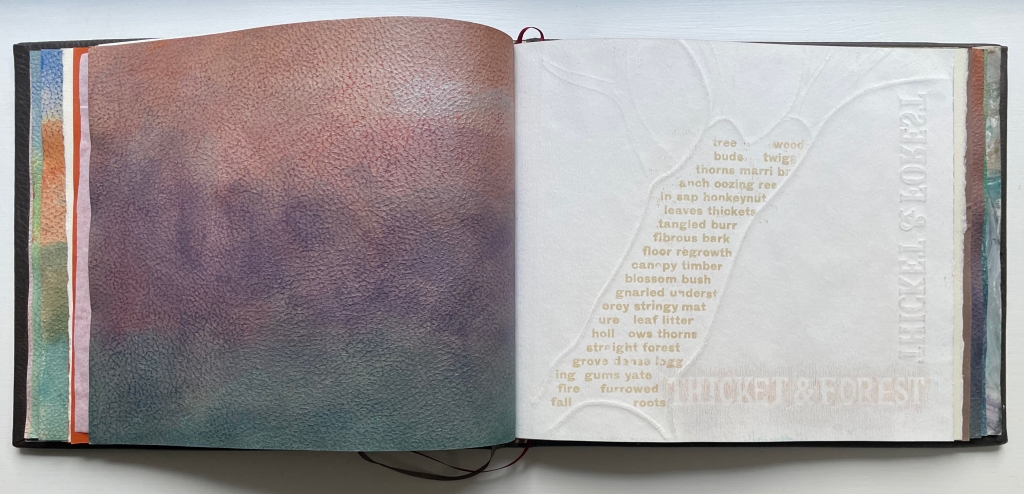

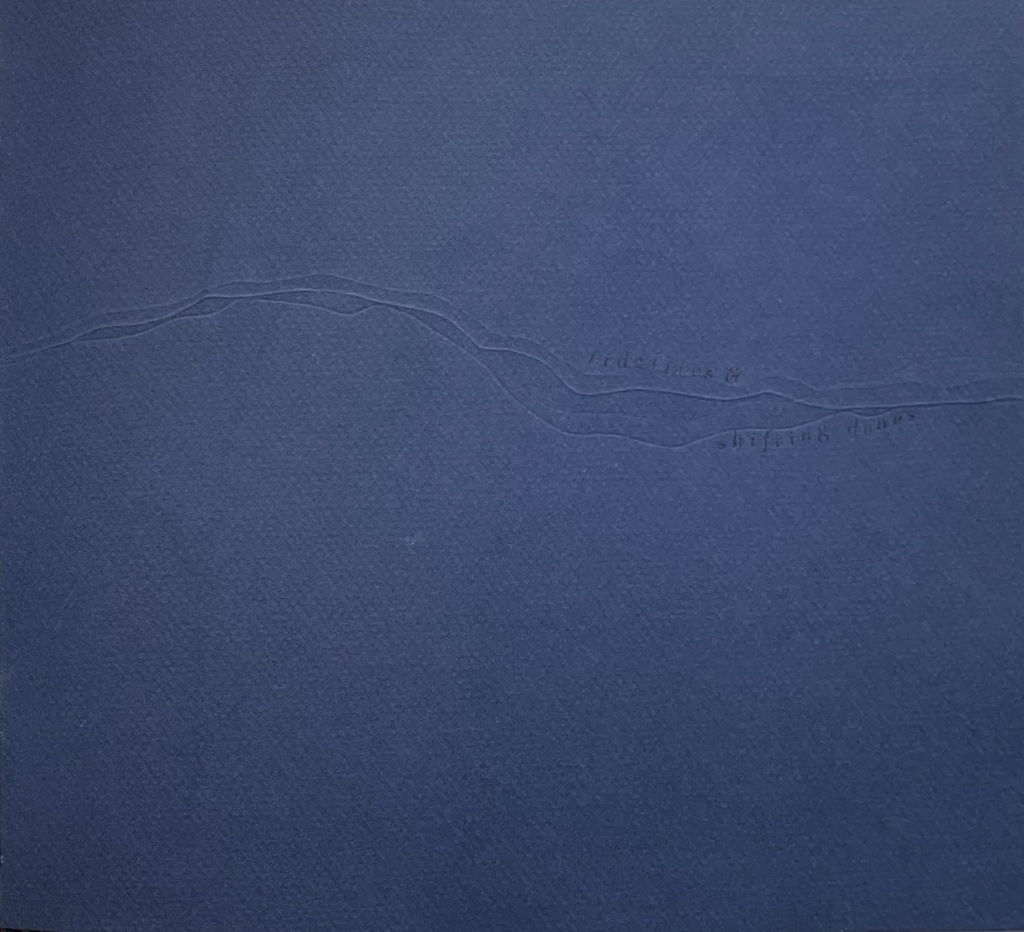

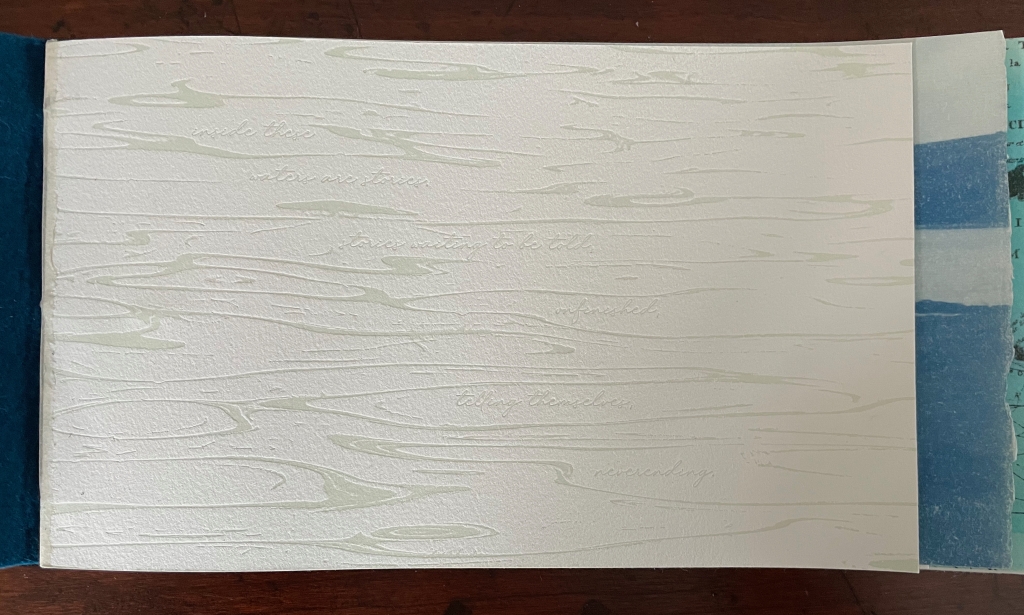

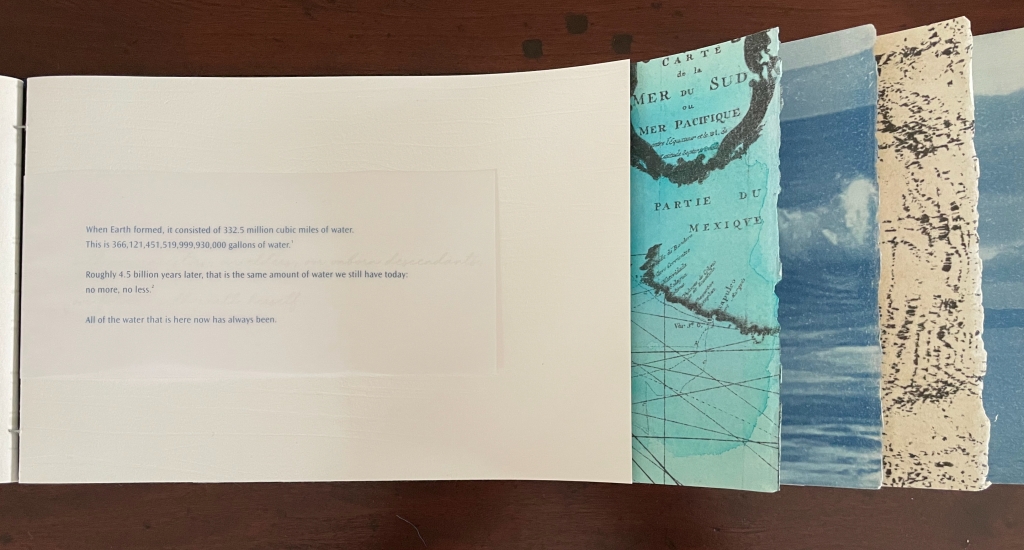

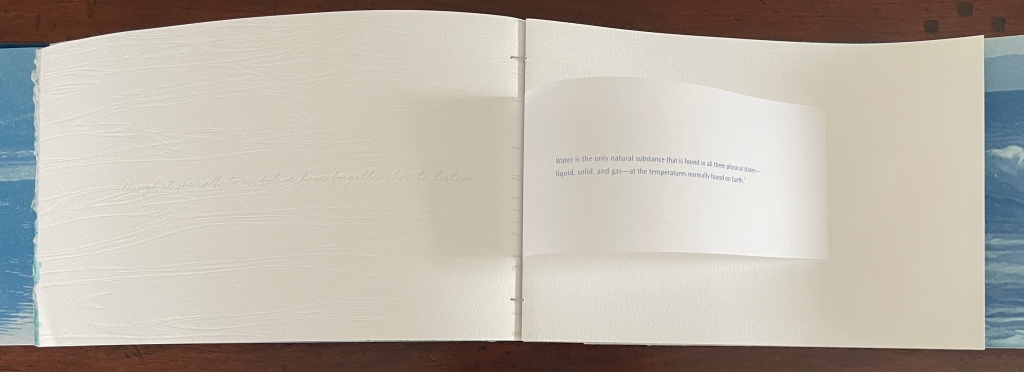

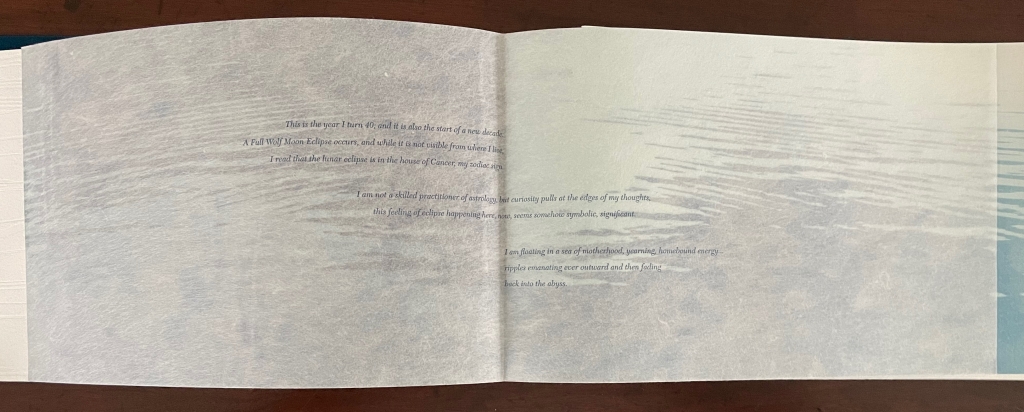

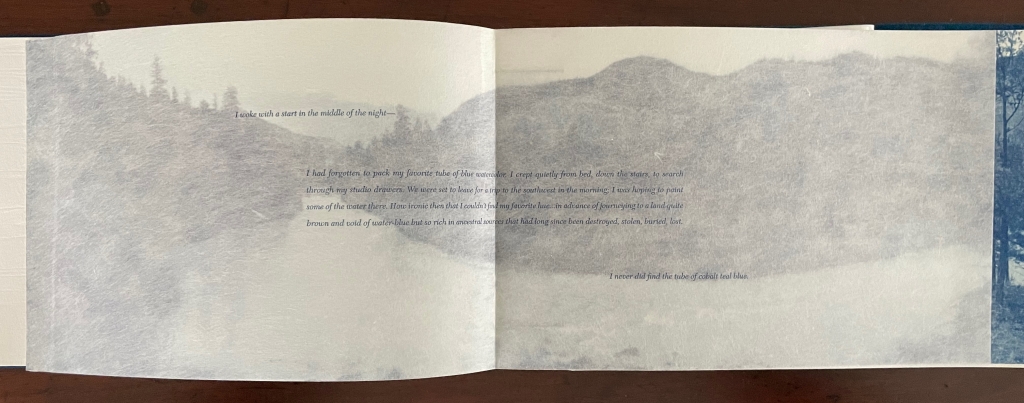

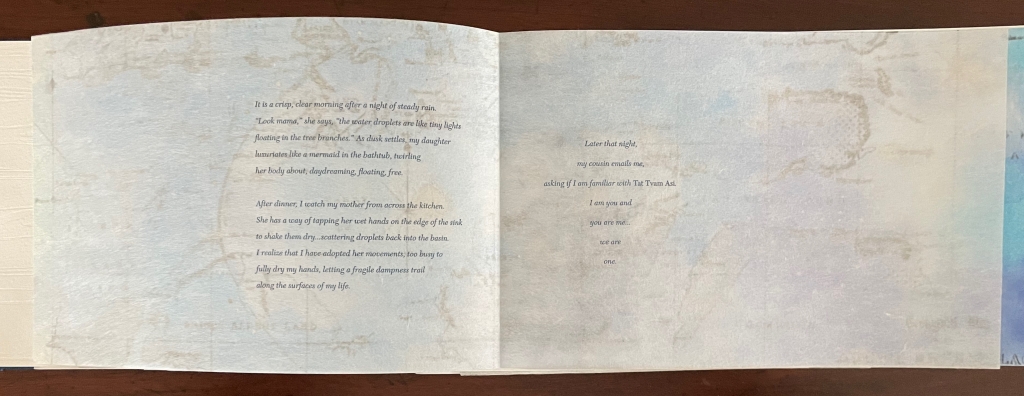

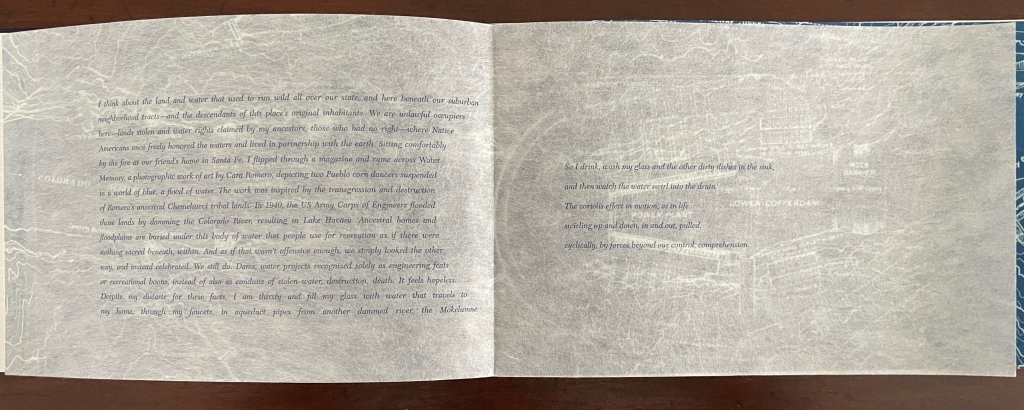

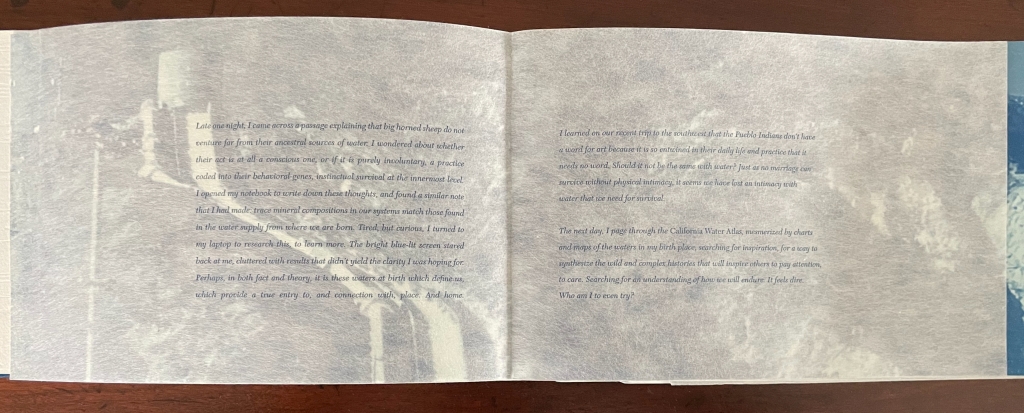

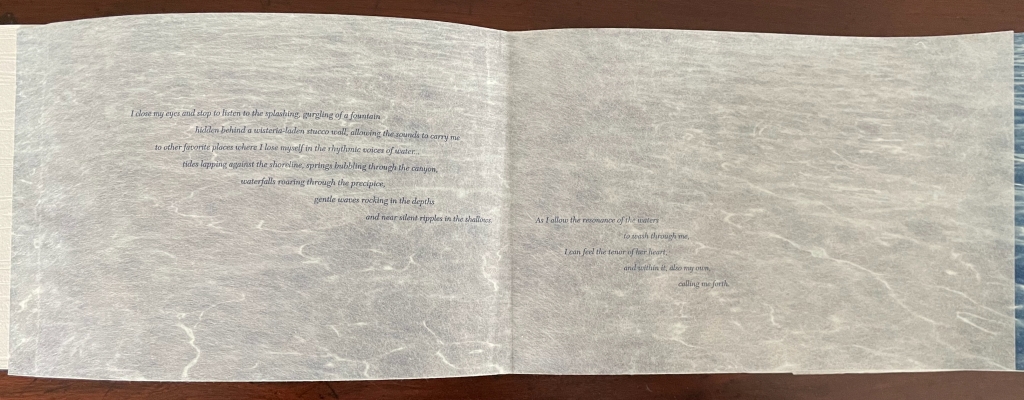

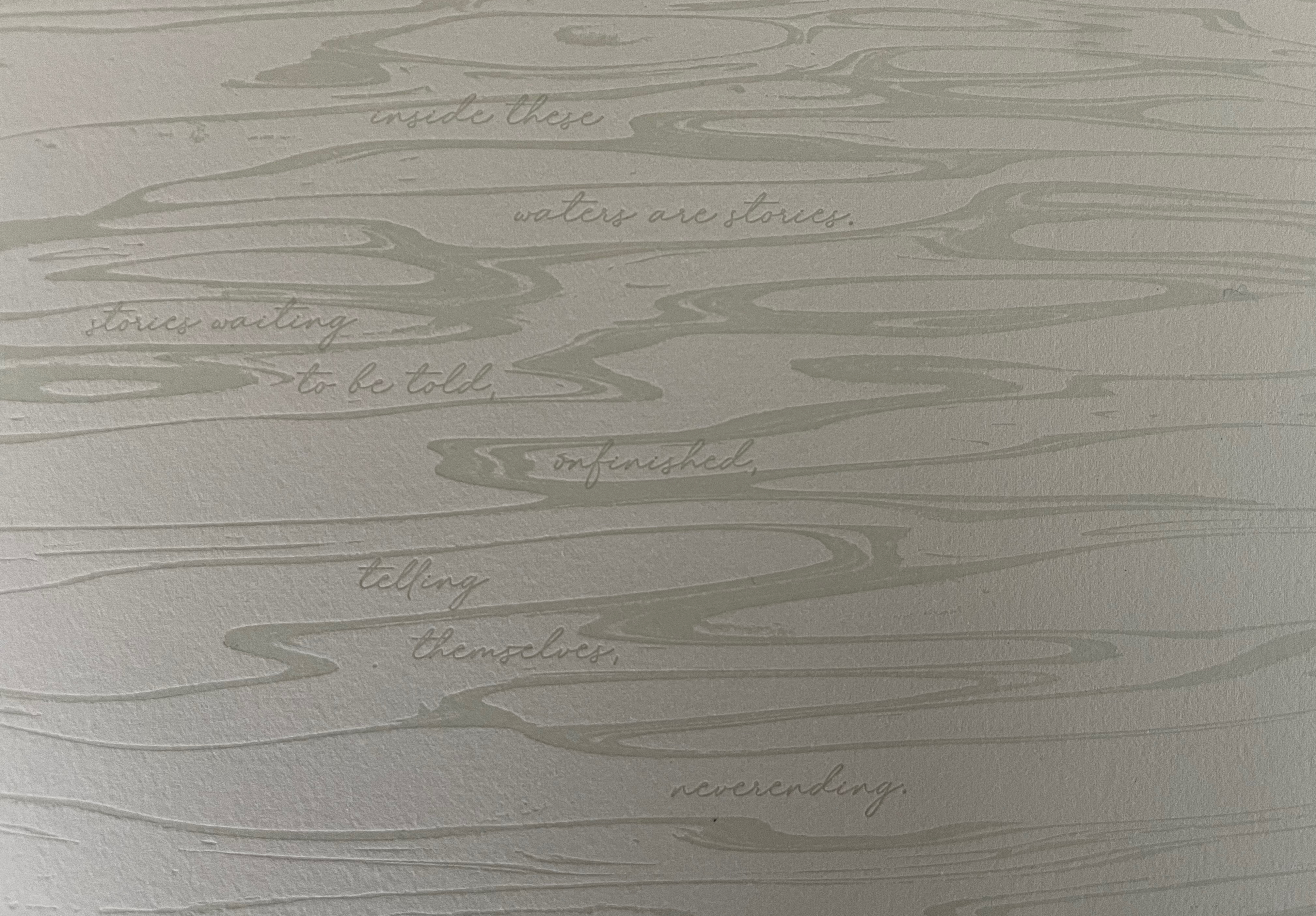

A distinctive modification of the binding is the inclusion of a narrow-cut sheet of Gmund Transparent in the second signature that interleaves with the third signature. The dry facts printed on the transparency interrupt the flow of the text debossed at the end of the first signature and beginning of the second. Each of the remaining pairs of signatures has a narrow-cut linking sheet of dry facts making up one stream of text interweaving with the more lyrical text and water patterns debossed on the Rives BFK paper.

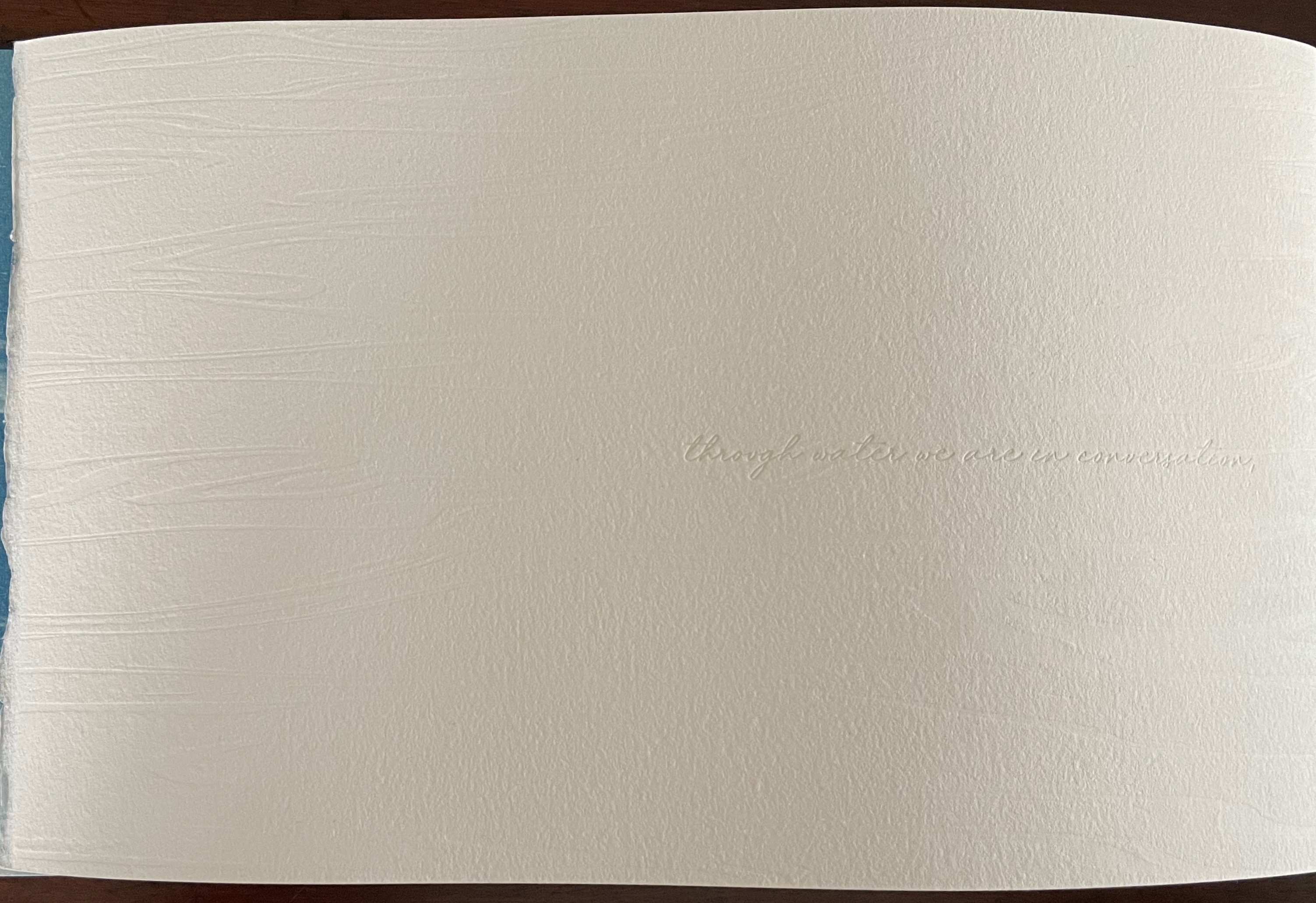

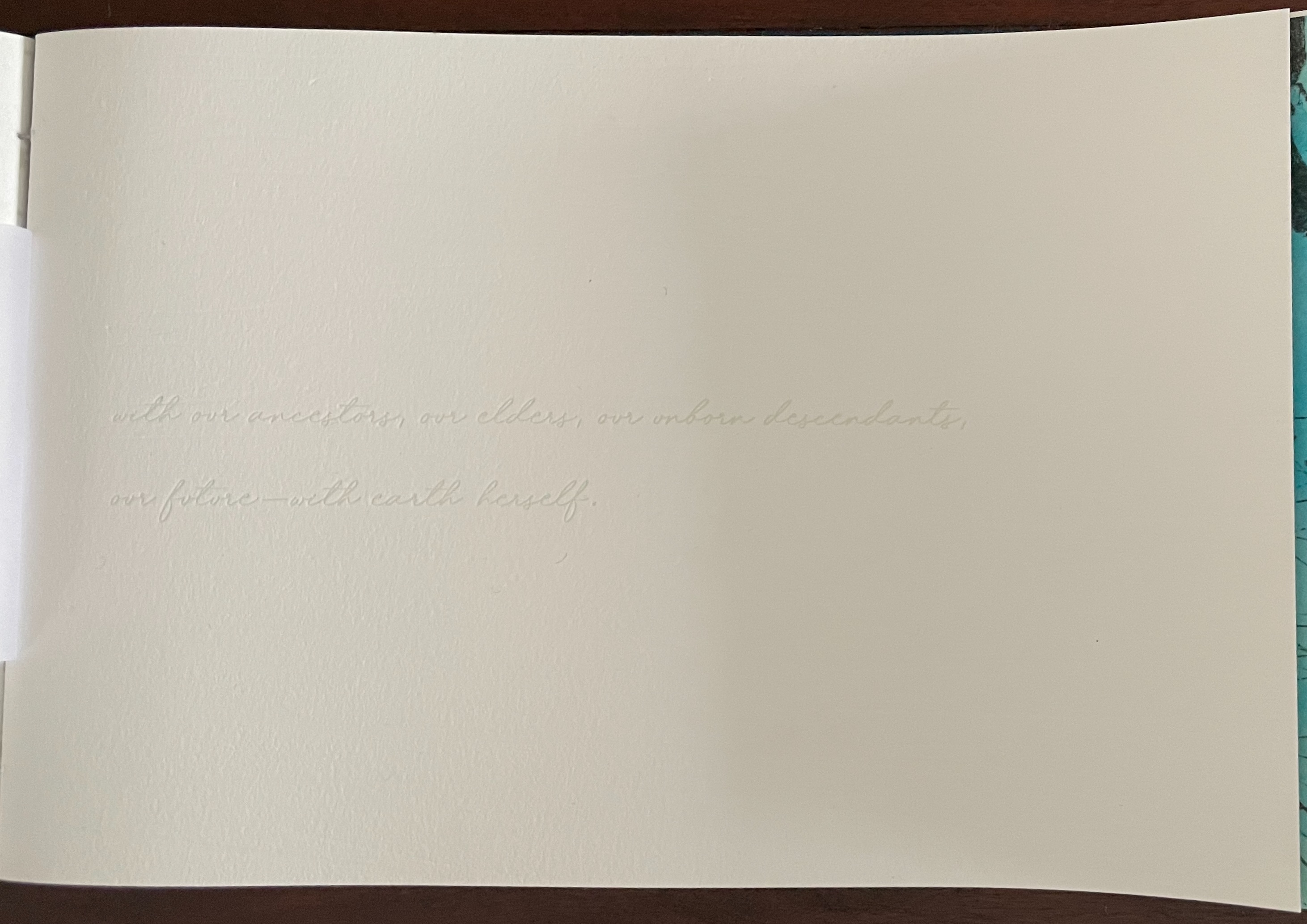

Set in the cursive Magdallena, the debossed text reads “through water we are in conversation, | with our ancestors, with our elders, our unborn descendants, our future — with earth herself.”

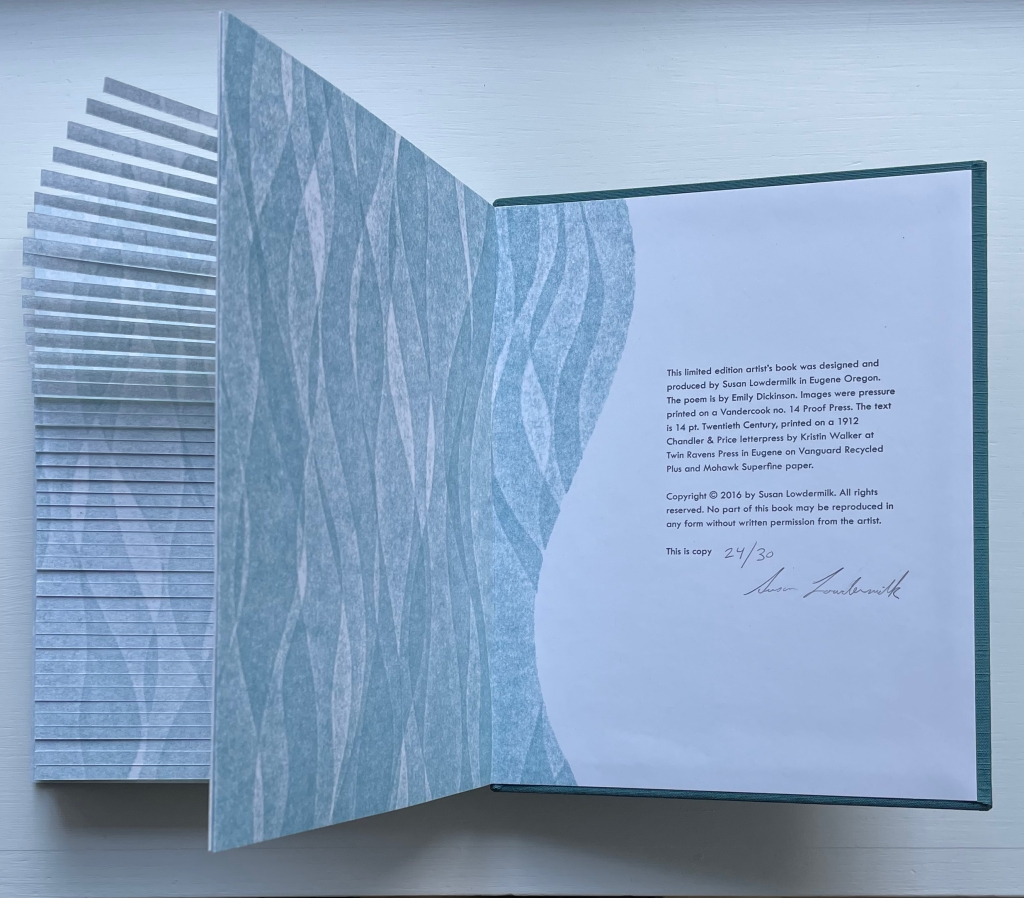

All eight of the translucent sheets can seen from this sideways rear view of the seventeen signatures. So the dry, however impressive, facts on the translucent sheets make up one stream of text interwoven with the more lyrical text and water patterns debossed on the Rives BFK paper.

A sideways view of the back of all seventeen signatures shows all eight of the translucent sheets.

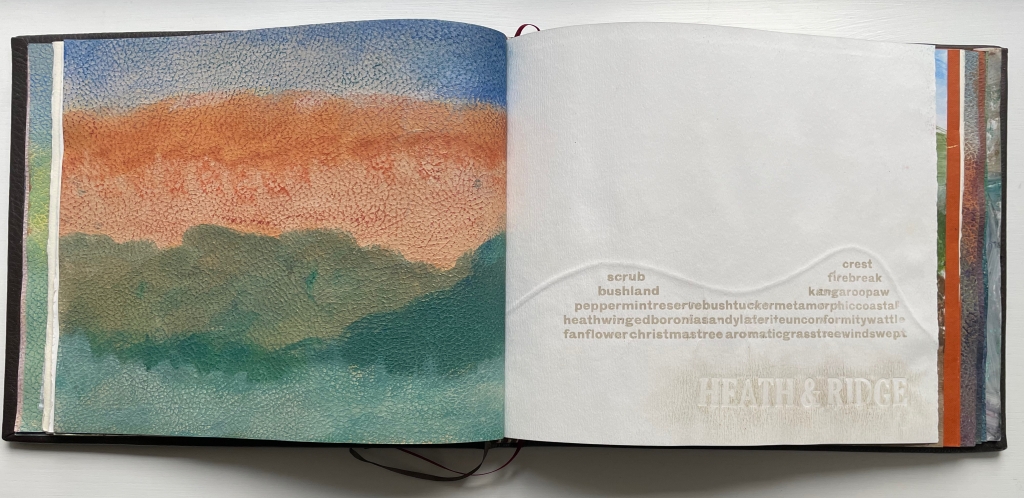

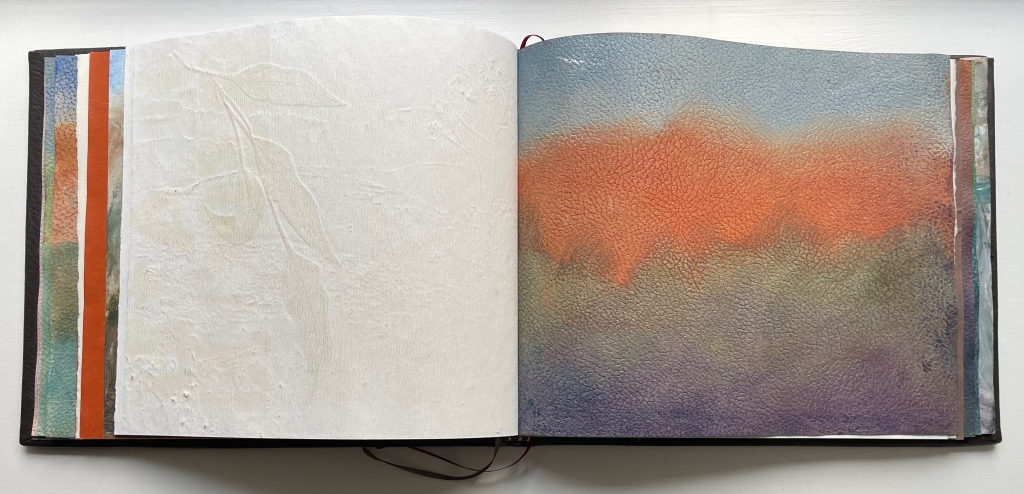

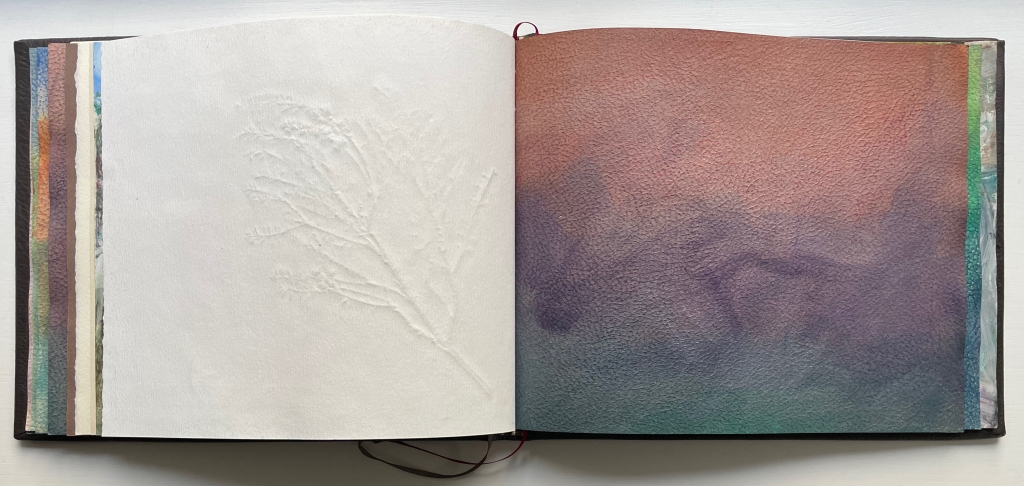

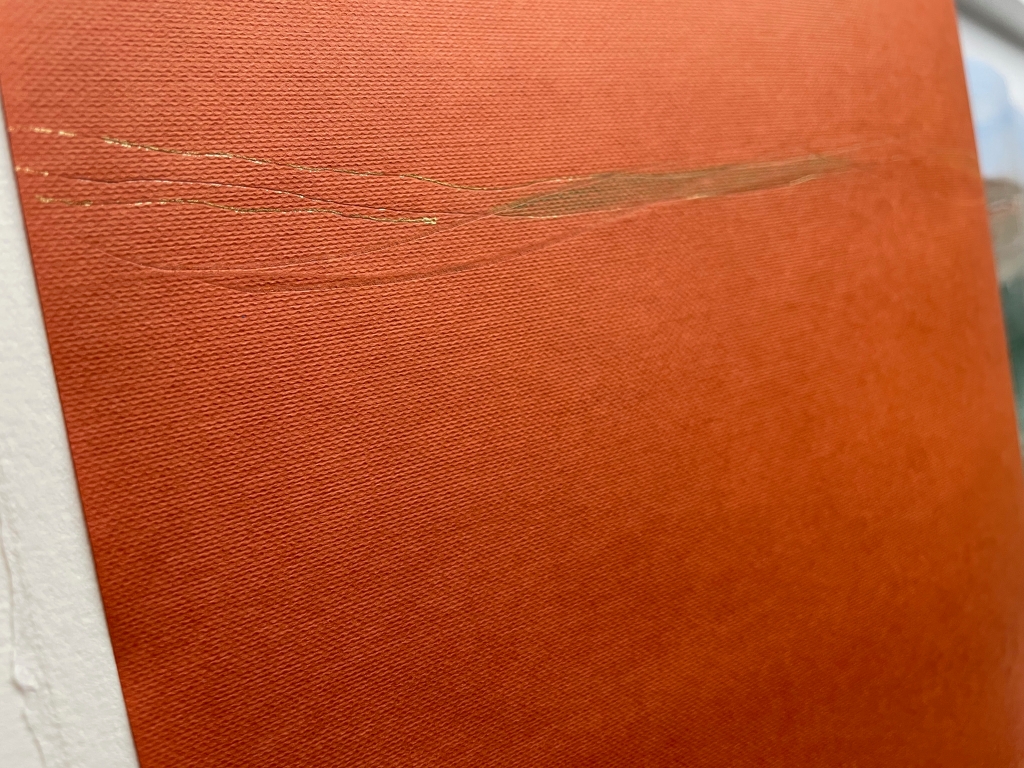

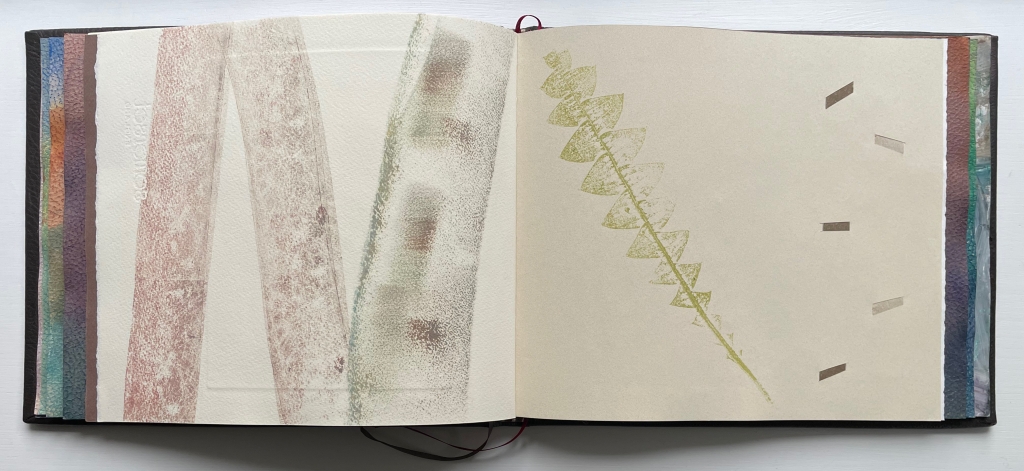

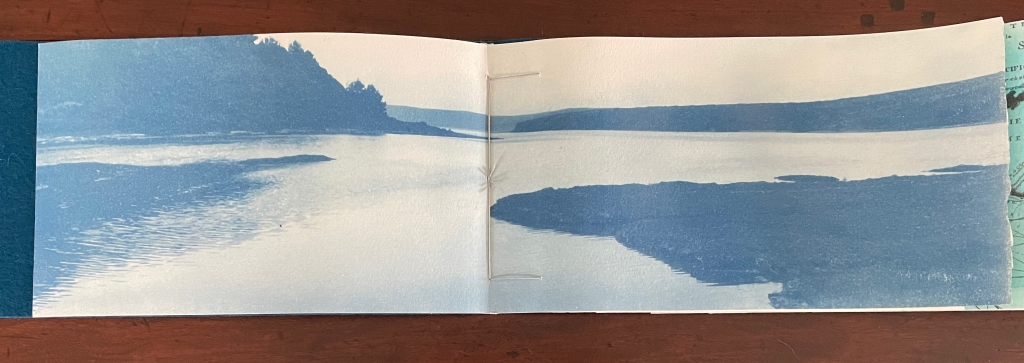

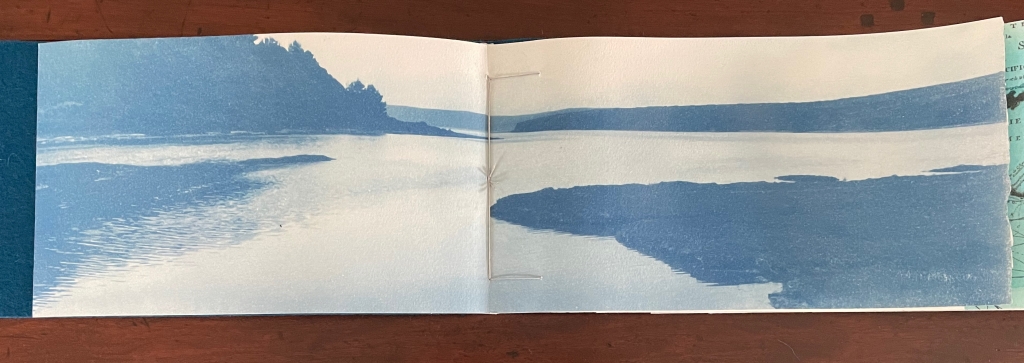

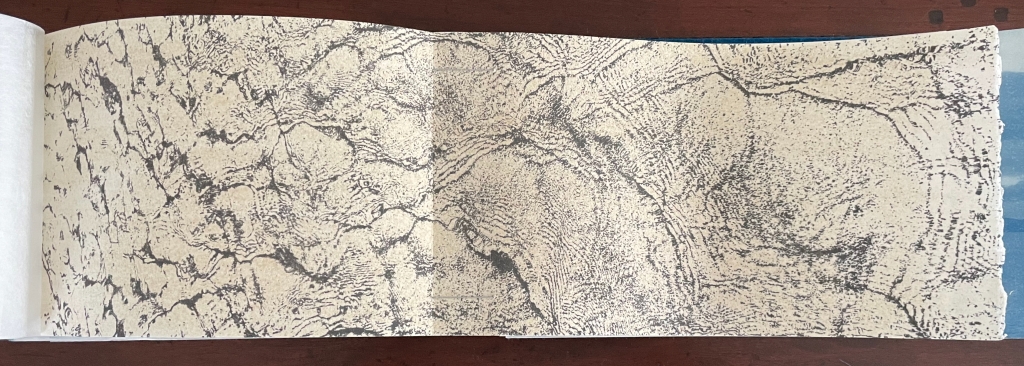

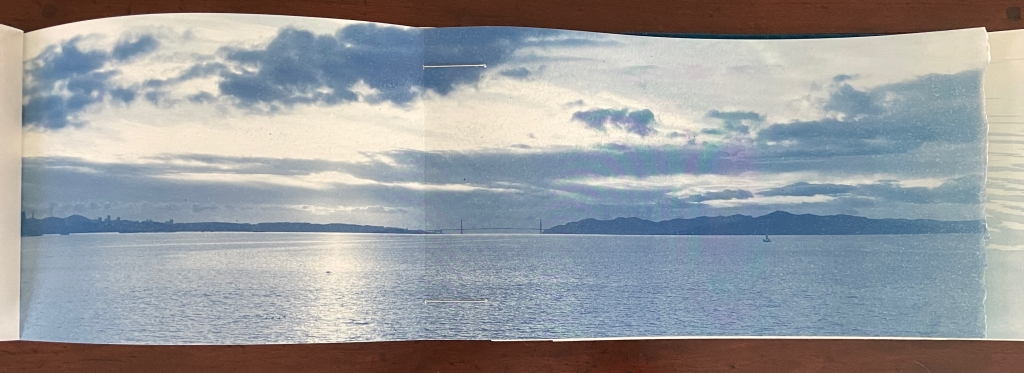

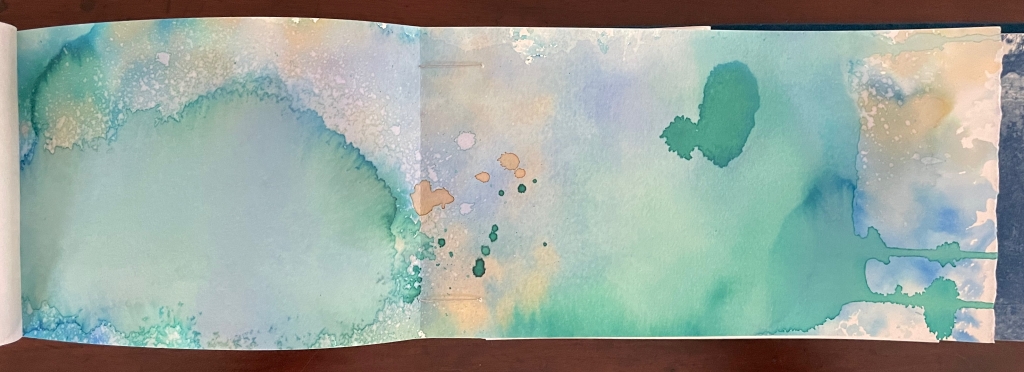

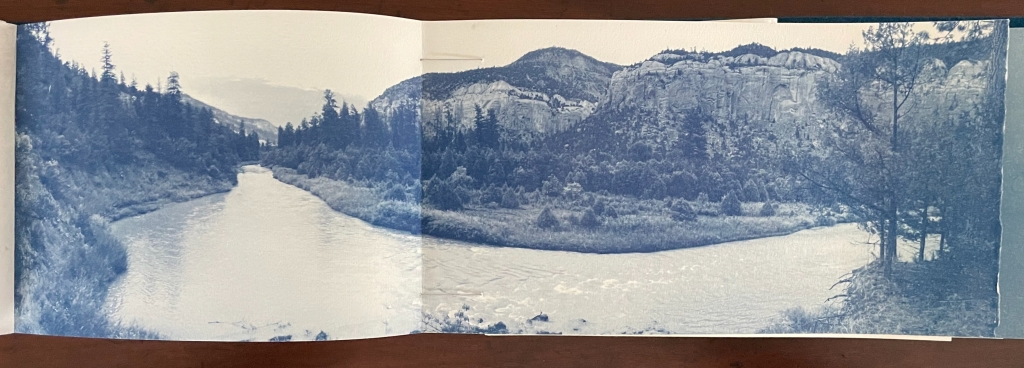

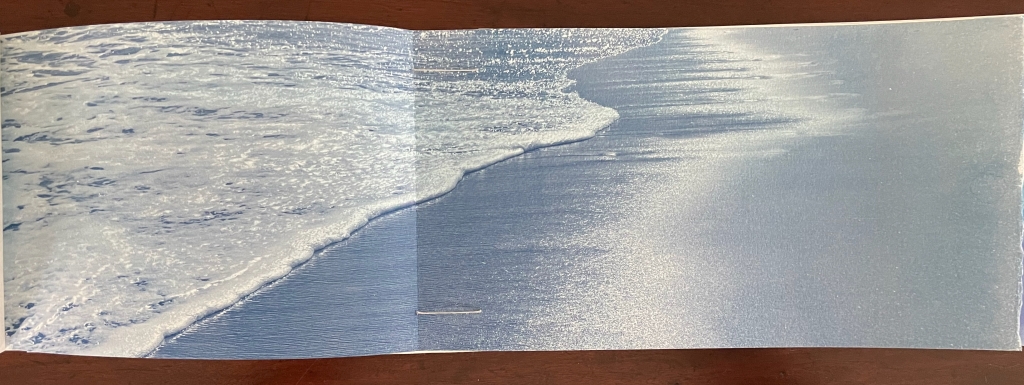

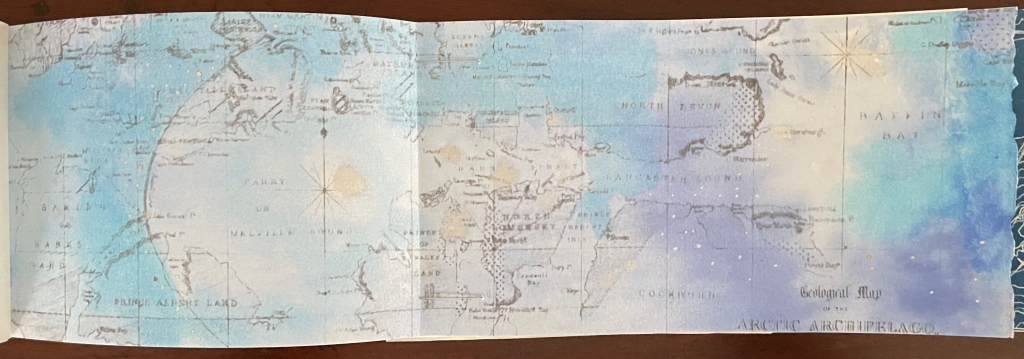

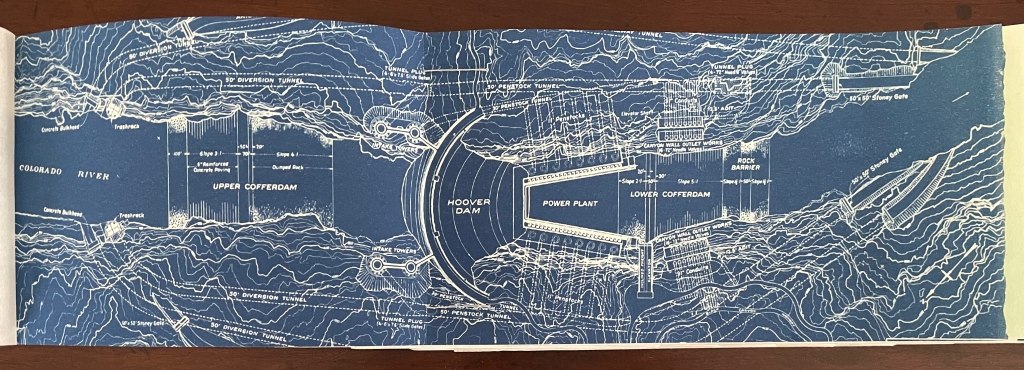

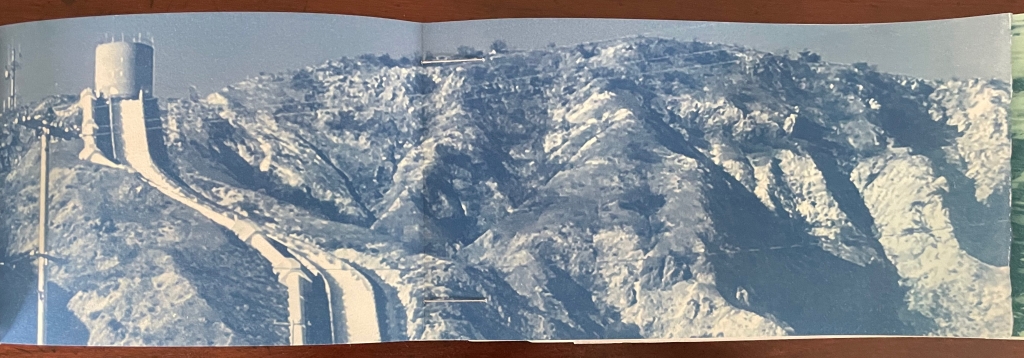

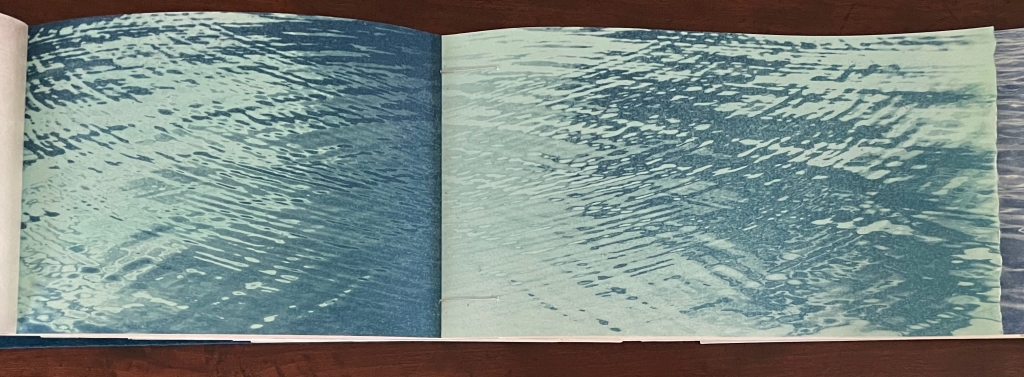

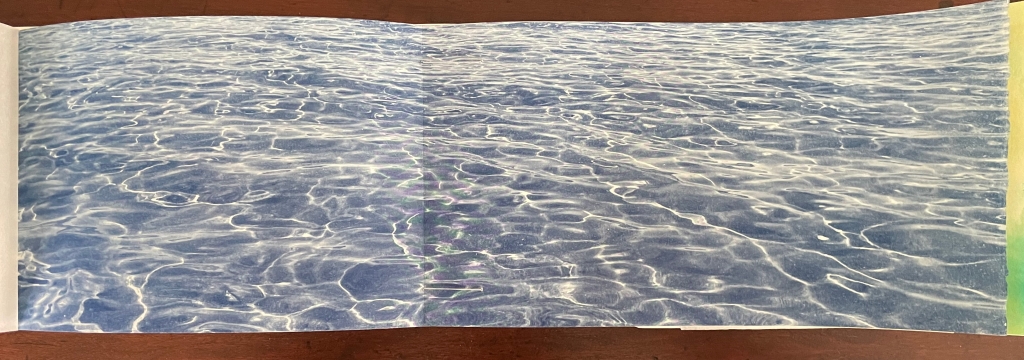

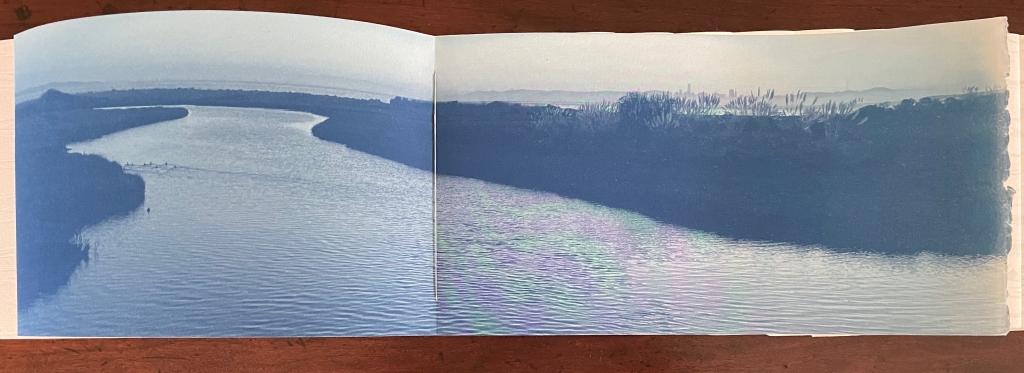

Within each of the seventeen signatures, there is a double-page spread of artwork: a series of cyanotype prints of original photographs, image transfers sourced from historical maps, and watercolor art.

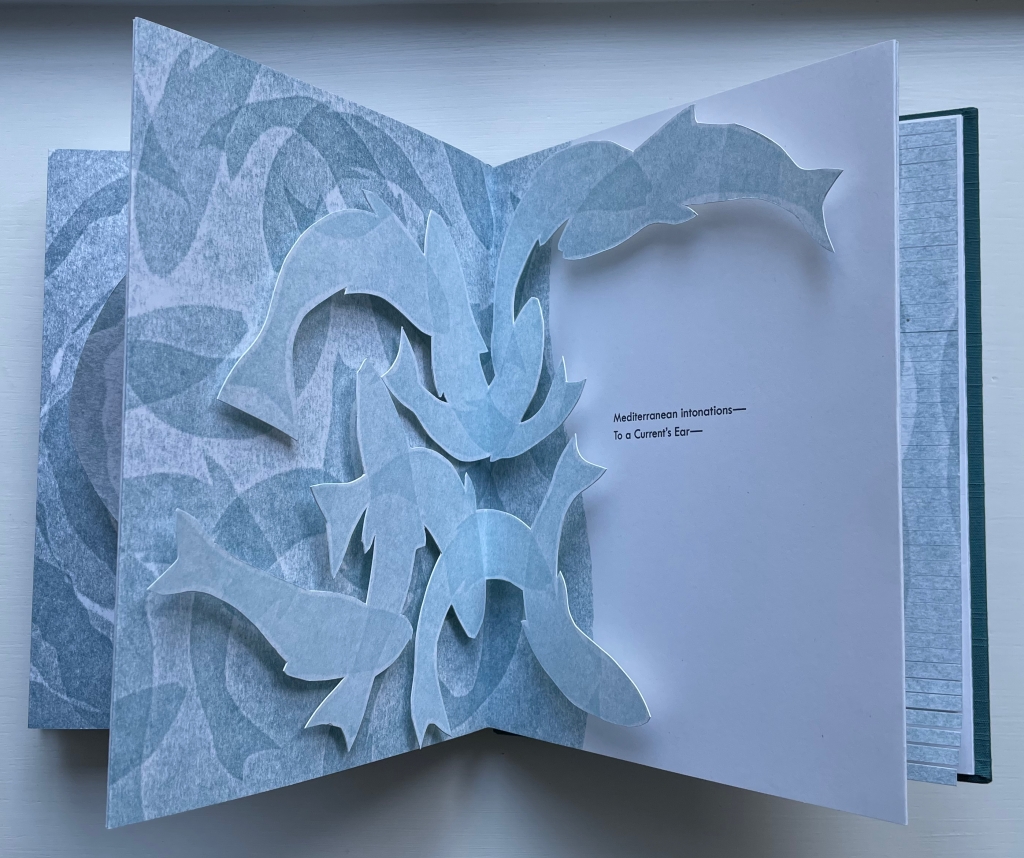

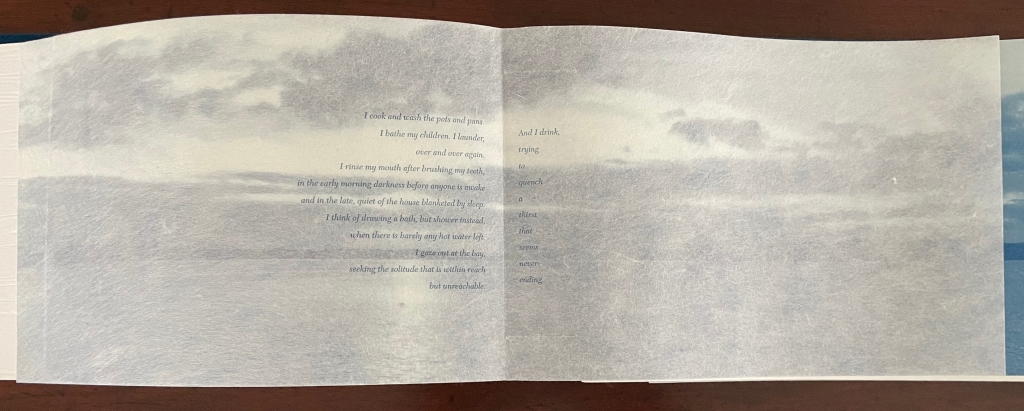

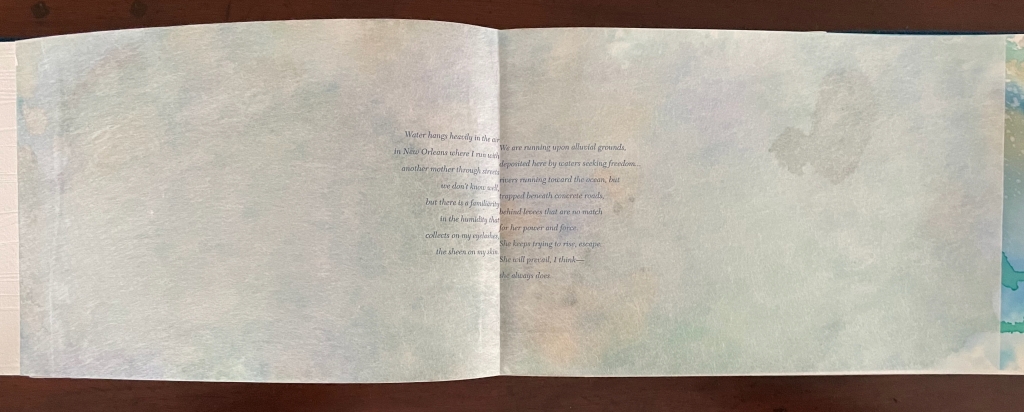

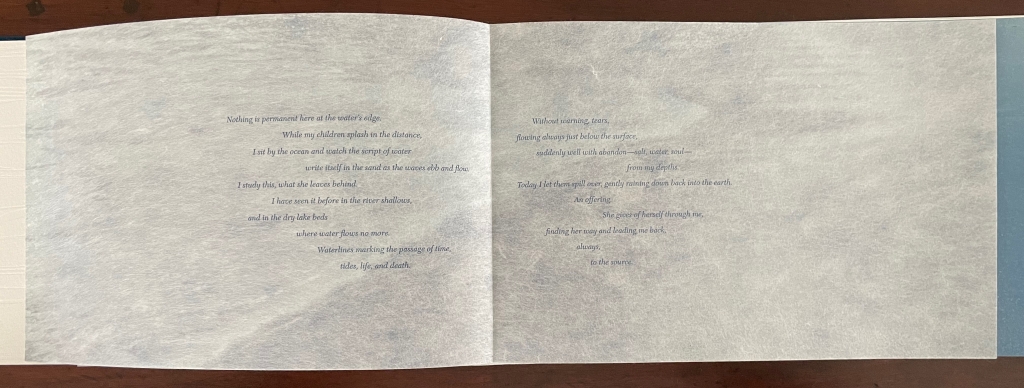

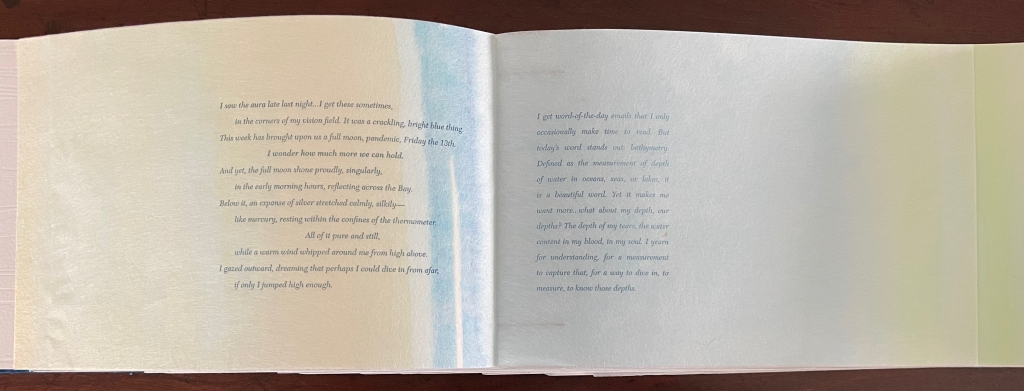

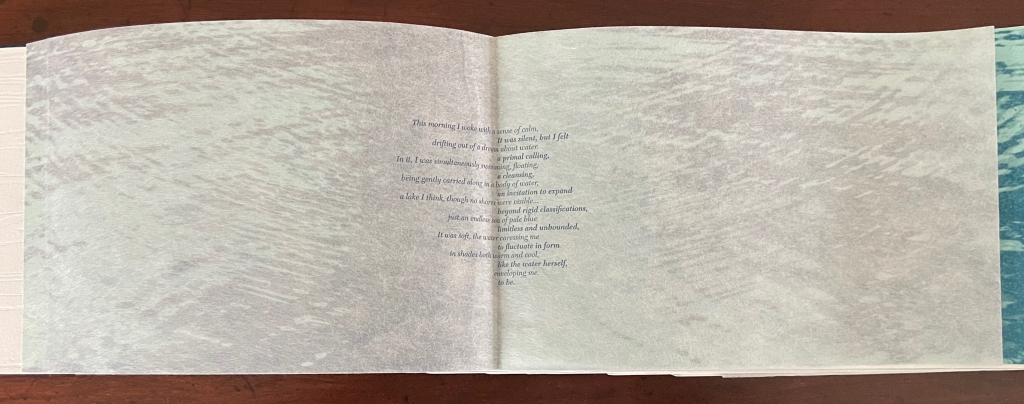

With the third double-page spread, a third stream of text and a material element of interweaving occurs. Richards introduces a more personal set of observations typeset in New Caledonian on a sheet of Sekishu paper attached to the lefthand edge of an underlying spread of artwork. Nothing quite like this appears in other works of dragon-scale binding. The presence of those Sekishu sheets requires some care in turning the pages, unscrolling and scrolling the work. This modification of the dragon-scale binding heightens its delicacy and slows down the process of reading, looking and reacting, which reinforces the artists’ words.

There are thirteen of these Sekishu sheets in total, leaving two double-page spreads at the beginning and two at the end uncovered. This is not by accident. Structurally it reflects the ouroboros nature of the debossed text on the Rives BFK: it ends as it began.

The width of the opened work and way the reader must almost embrace it to open it reflect the breadth of the artists’ meditation on various bodies of water—wild and managed, urban and rural. The interwoven leaves and text reinforce the makers’ (and water’s) call to “pay attention” and reconnect.

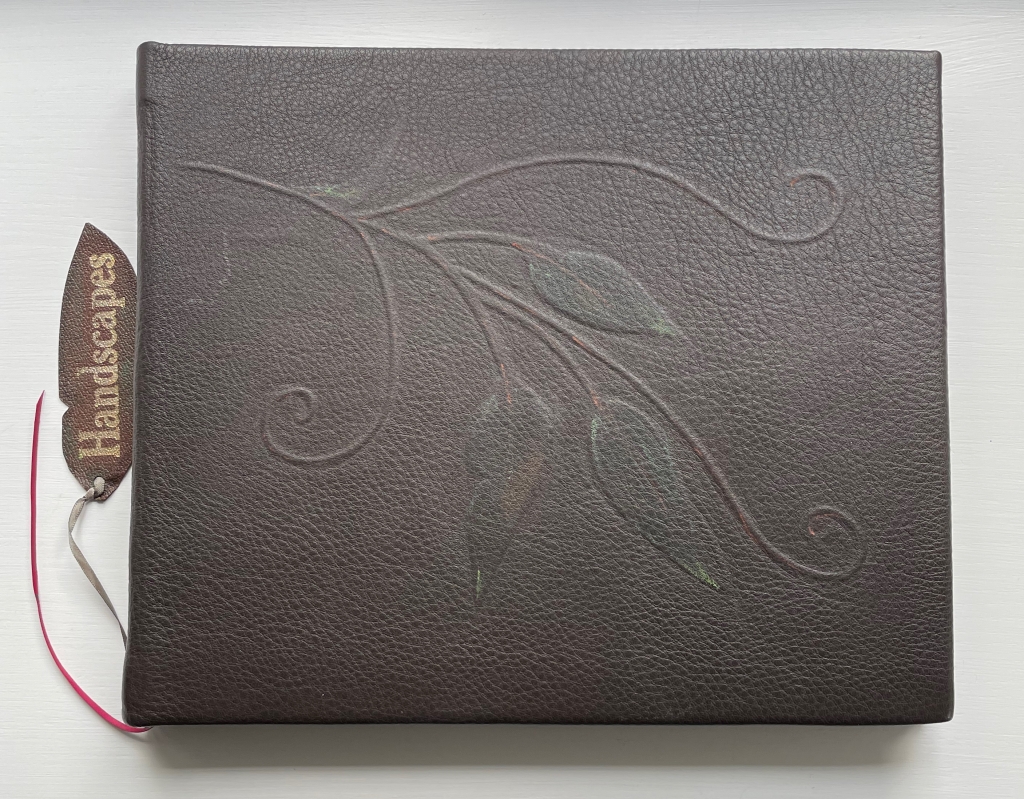

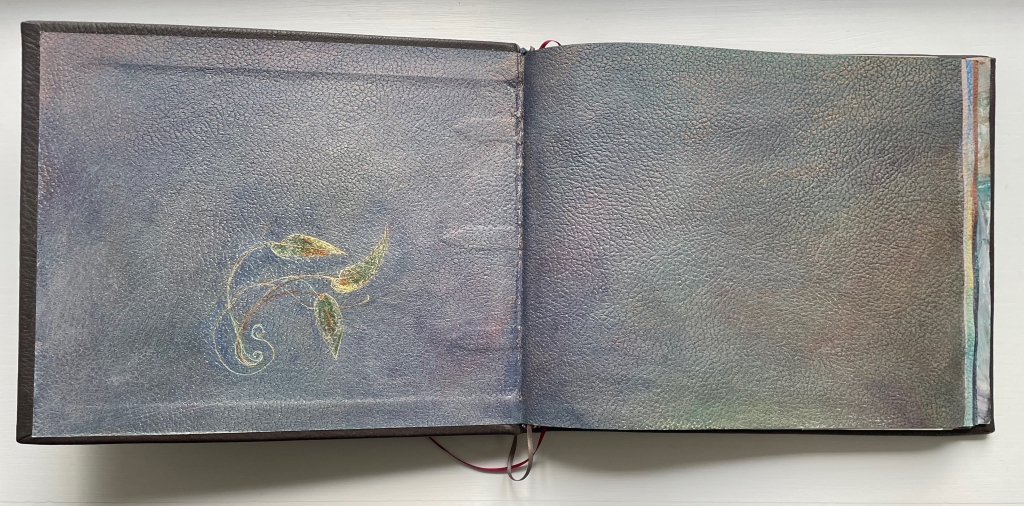

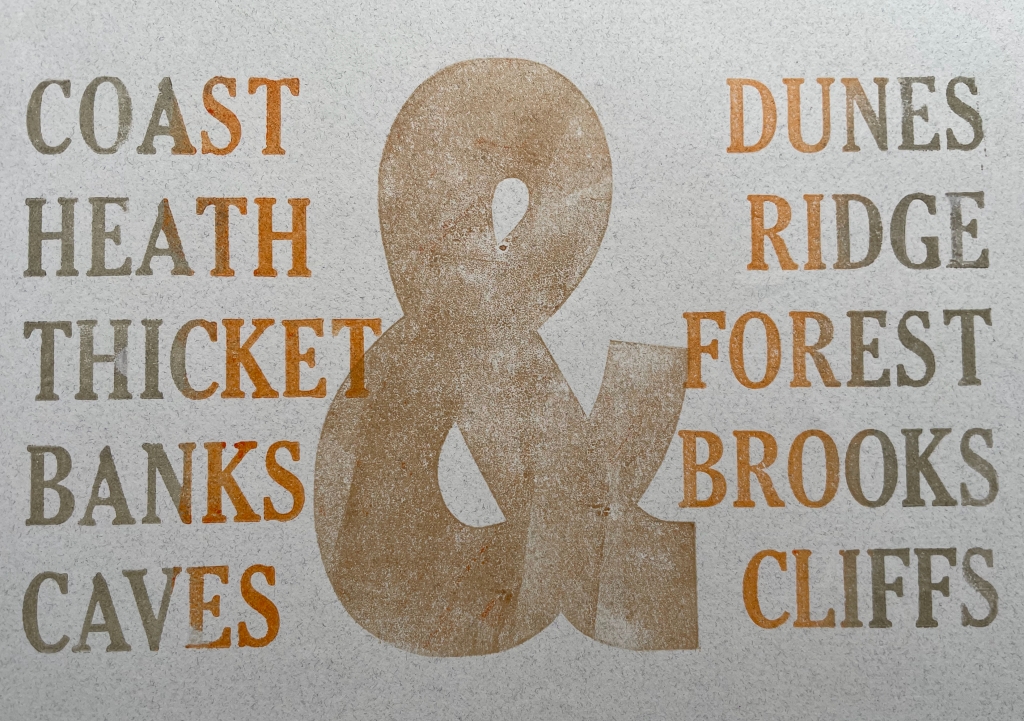

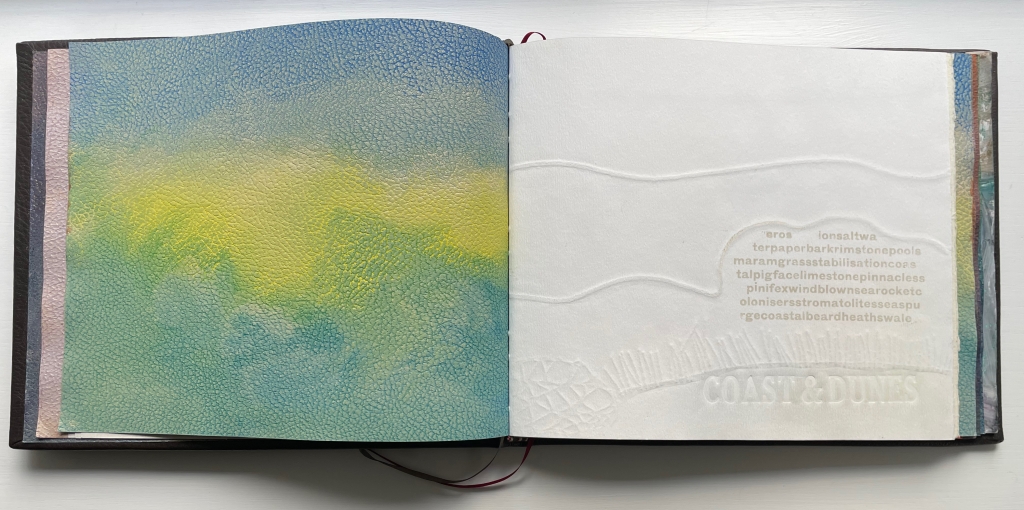

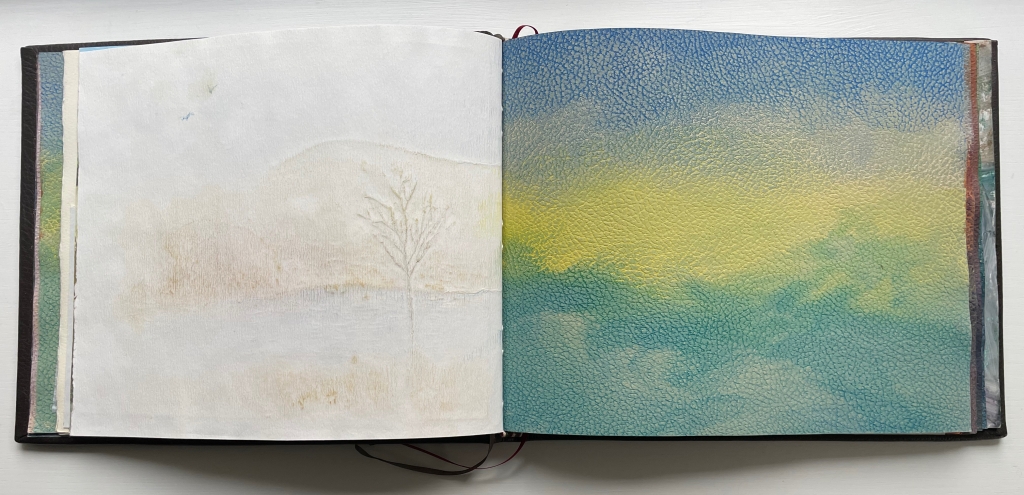

Other examples of dragon-scale binding in the Books On Books Collection include works by Barbara Hocker, Nif Hodgson, Rutherford Witthus and Zhang Xiaodong. It seems no accident that Hocker and Hodgson adopt the dragon-scale binding to evoke the element of water. But other artists in the collection who aim to evoke the element choose another structure that, like dragon scale, seems to be a transition from scroll to codex: the accordion fold or leporello and its variant the window-panel flag book. Among the leporellos are Helen Douglas’ Follow the River (2015-17), and for an example of the variant, there is Cathryn Miller’s Westron Wynde (2016). Of course, the codex is not antithetical to the theme. The sense of water pours from the “Coast & Dunes” and “Banks & Brooks” sections of Margaret (Molly) Coy & Claire Bolton’s Handscapes (2016) and Bodil Rosenberg’s Vandstand (2019), though the size, shape and texture of the latter may have more in common with the sculptural and equally evocative I think that the root of the wind is water (2016) by Susan Lowdermilk and Breaking Waves (2023) by Emmy van Eijk. Still, even in this century, the scroll continues to offer an effective conduit whether in paper or pixels as Helen Douglas’ The Pond at Deuchar (2011, 2013) demonstrates.

Of all these works, Water, Calling engages multimedia the most in its invocation and evocation of the element of water. Its environmental soundscape, created by Anne Hege with a hand-built, analog looping tape machine, consists of water recordings, instrumentals and vocal incantations. To listen to excerpts from the soundtrack, click here, or to listen to the full soundtrack, click here (password required; request access here).

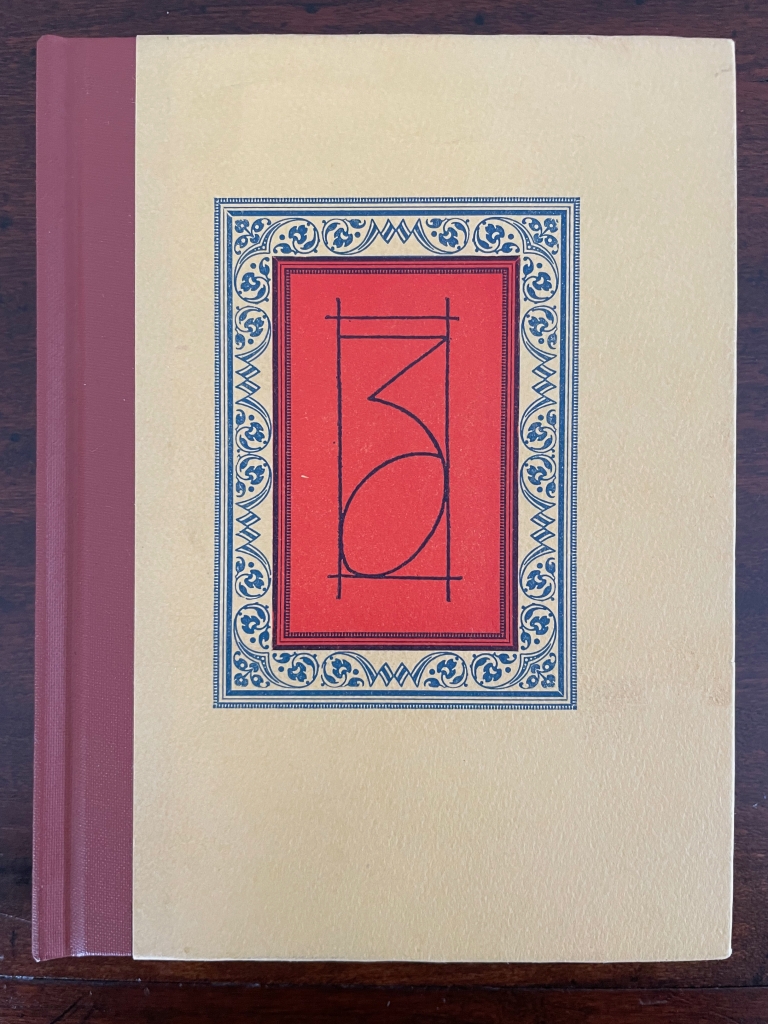

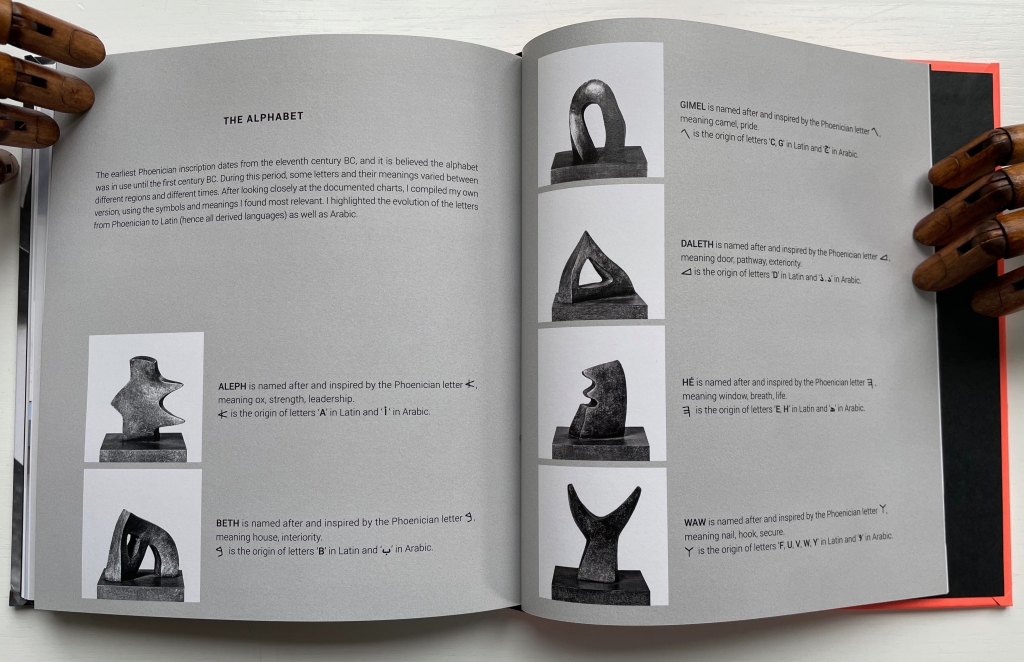

The Space Between (2018)

The Space Between (2018)

Camden Richards & Deborah Sibony

Casebound with cloth-covered spine between bonderized steel covers in a cloth-covered custom box. Box: H216 x W305 x D24 mm; Book: H197 x W284 x D10 mm. 50 pages. Edition of 13, of which this is #11. Acquired from the artists, 5 October 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artists’ permission.

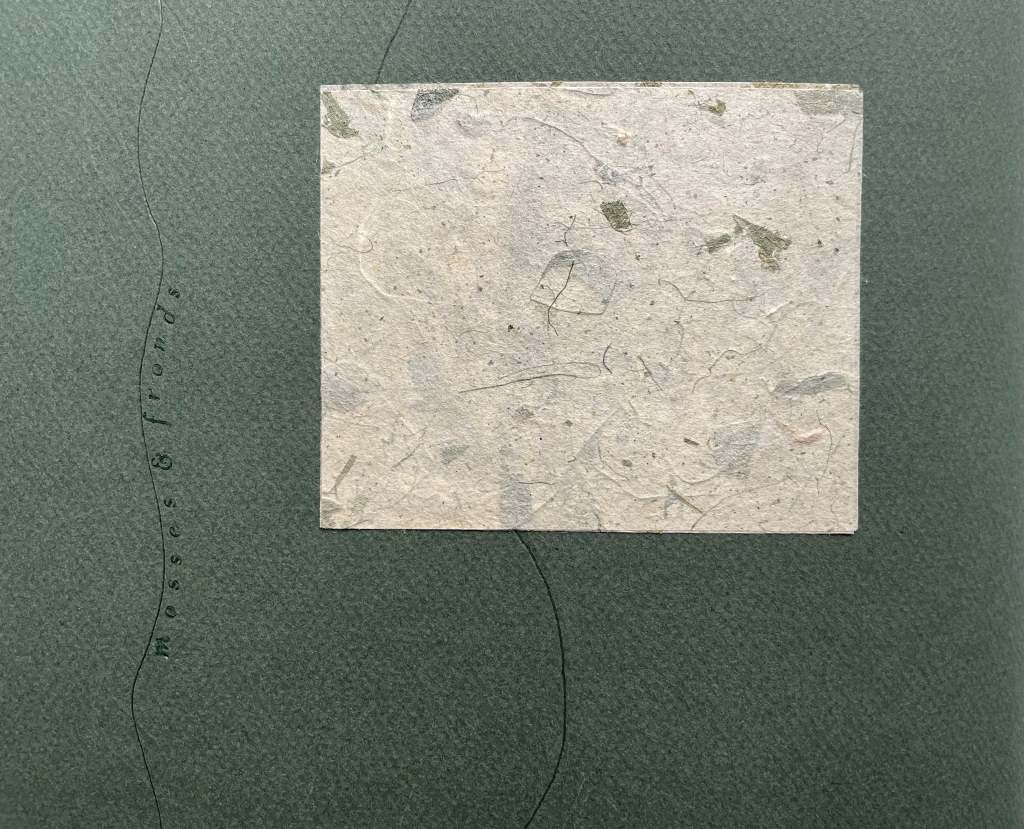

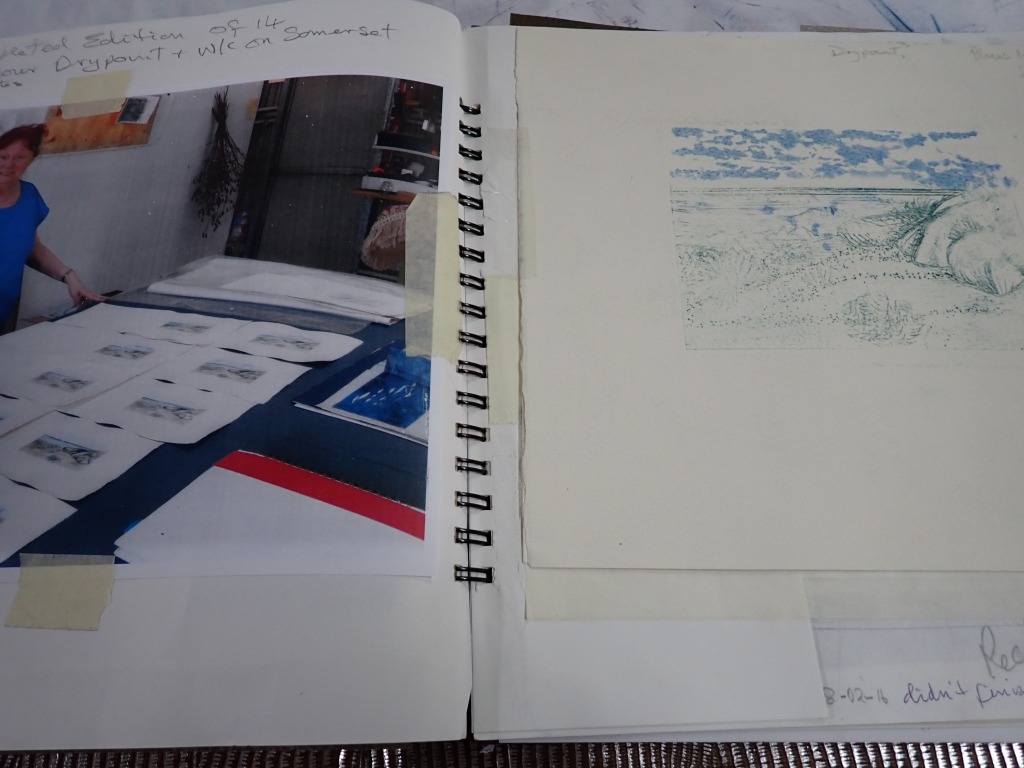

An earlier collaboration between Richards and Sibony, The Space Between is based on ten original monotypes printed by Sibony at Studio 1509 on a Takach press and digitally reproduced for the book by Coast Litho on Grafix matte drafting film. The work’s text is set in Mark Simonson’s Goldenbook; its typographic layout, die-cuts and letterpress printing is by Richards at Liminal Press + Bindery on Somerset Book paper with a Vandercook 4 proofing press; and its handmade paper embedded with local Bay Area plant fibers comes from Pam DeLuco of Shotwell Paper Mill. The Space Between is bound in bonderized steel covers and housed in a custom box by John DeMerritt.

The ten monotypes were inspired by the gradual removal of the eastern span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge after its partial collapse in 1989. About that inspiration, Sibony writes:

On the day of the Loma Prieta earthquake (October 17, 1989) I had just begun commuting from San Francisco to work at Fantasy Records in Berkeley. Thus began my long-term relationship with the Bay Bridge. The quake caused the collapse of a 50-foot section of the upper deck and led to the death of a 23-year-old woman. I was fortunate not to be driving home on the bridge at the time of the earthquake, when I could easily have been returning to San Francisco. I spent that night in Berkeley with a friend since the bridge was closed to all traffic, and would remain so for several weeks.

Twenty-four years later, on September 3, 2013, a wondrous, white, single-span was set to replace the damaged eastern section of the bridge. On the day before the eastern span was closed forever and the dismantling began, I drove across that compromised structure for the last time. As I shot video from the car, a feeling struck me on a gut level: it was the start of a new era for the geography and landscape of the Bay Area — and the beginning of the end for an iconic structure that would soon cease to exist.

From then on I took photos with my iPhone whenever I drove across the new eastern span, adjacent to the closed cantilevered section, documenting its gradual deconstruction until it finally disappeared. Using a special transfer process I incorporated those images into a series of monotypes that are reproduced in The Space Between.

Sibony’s monotypes are fragments that illustrate moments of a vanishing and a metamorphosis of wood, concrete, and steel. In The Space Between, Richards uses letterpress printing, translucent substrate and die-cuts to pair Sibony’s images with text inspired by a poem by Charles Koppelman and thereby reimagines the two-dimensional monotype form into a three-dimensional book form. As the reader turns the pages, the images simultaneously build upon one another and retreat from one another, mimicking the moments of transition and creating a sense of meaning that emerges from spaces in between.

The Space Between is made with both machined and organic materials — from sheet metal covers to drafting film to handmade paper embedded with plant fibers — materials that ground it squarely in space and time as both a human and natural byproduct. The result is a physical and metaphorical exploration (and experience) of thresholds between those we physically create, those nature creates for us, and the space in between where we exist. Given the name of Richard’s enterprise — the Liminal Press — this work must hold a signal position for the publisher.

In its object and the theme it finds in the object, The Space Between resonates not only with the architecture-inspired works of book art in the Books On Books Collection but also those inspired by typography. See below.

Further Reading

“Architecture“. 12 November 2018. Bookmarking Book Art.

“Celebrating the 250th Anniversary of Steingruber’s Architectural Alphabet“. 1 January 2023. Books On Books. For the link with typography, see Proposition #1.

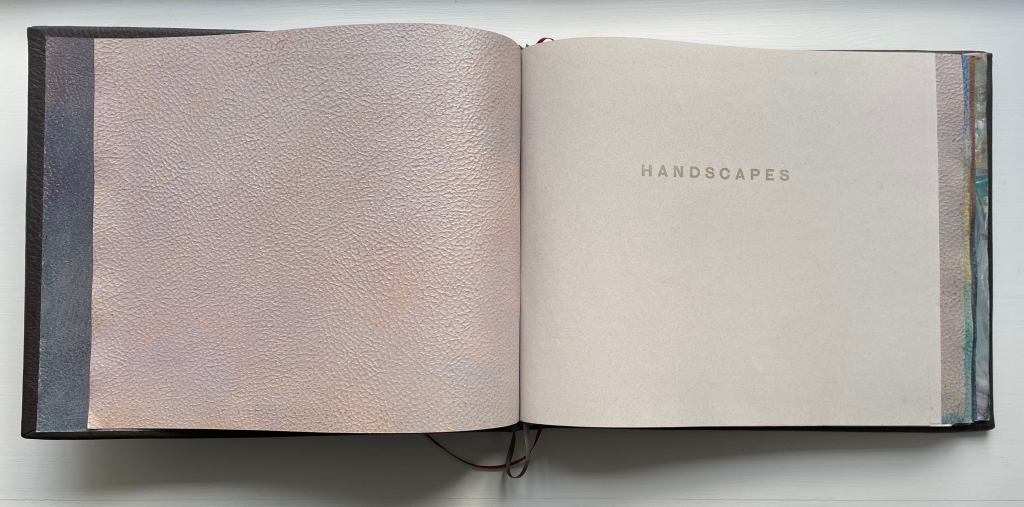

Margaret (Molly) Coy & Claire Bolton, Handscapes

Helen Douglas, Follow the River and The Pond at Deuchar

Nif Hodgson, Fluid Horizons

Susan Lowdermilk, I think that the root of the wind is water

Cathryn Miller, Westron Wynde

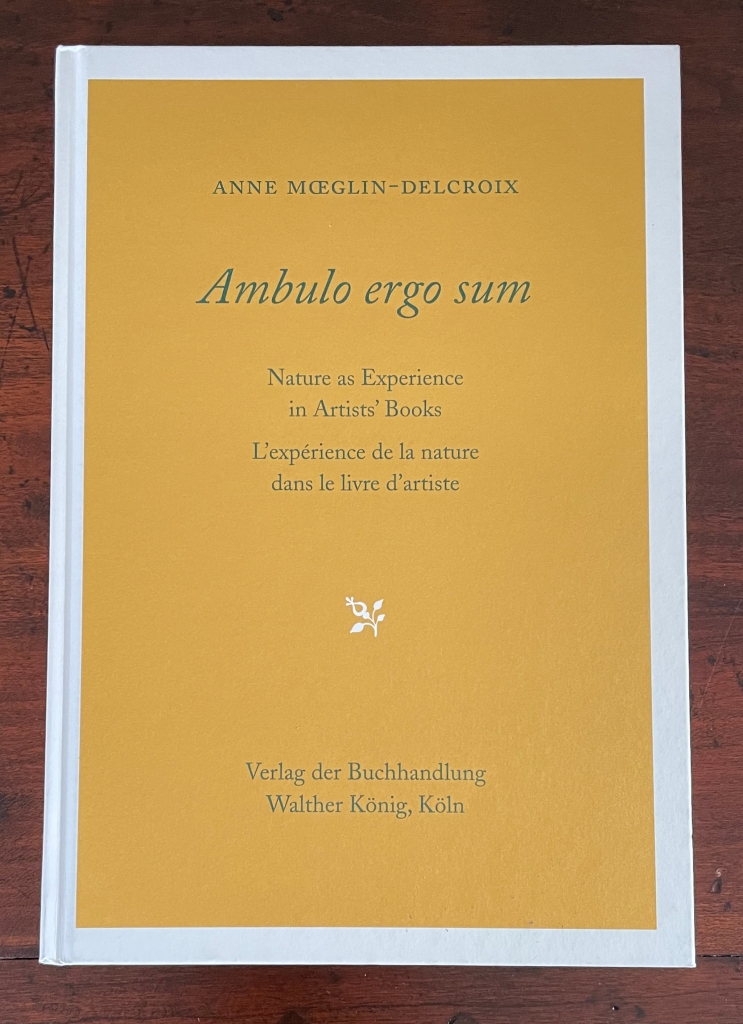

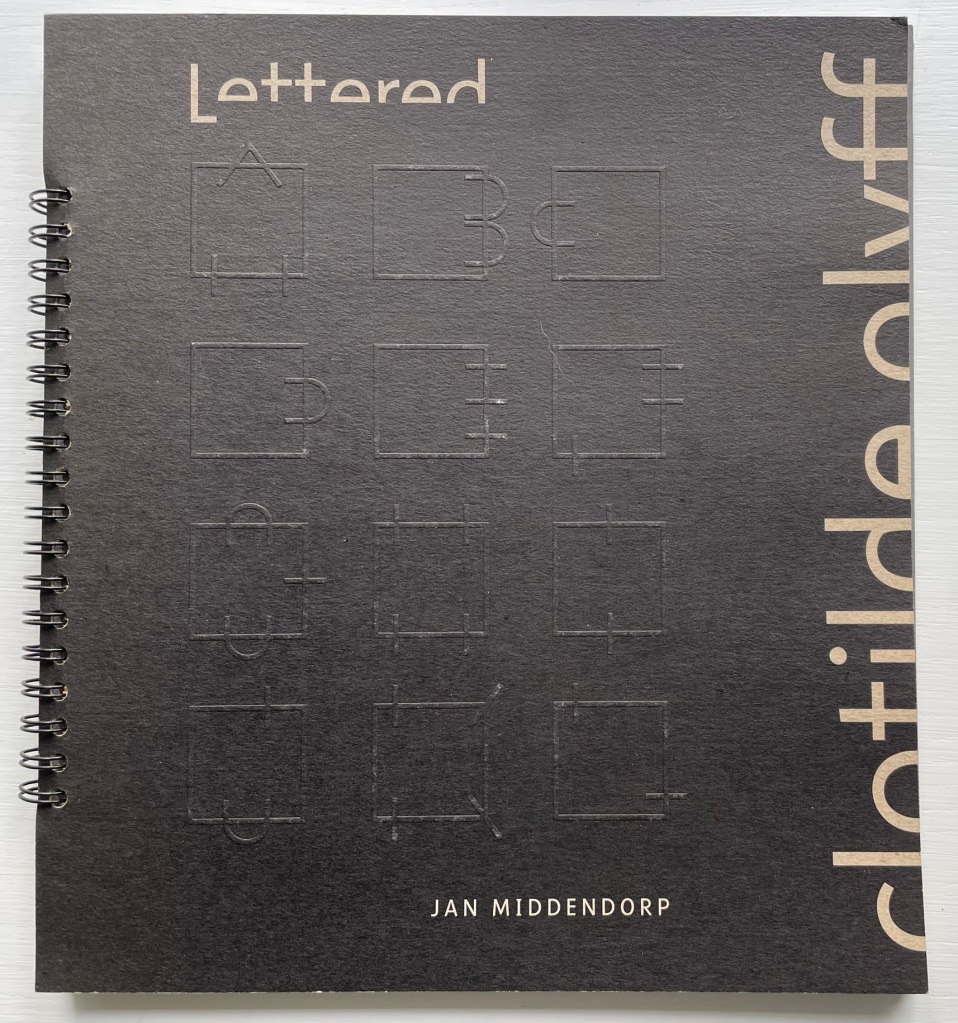

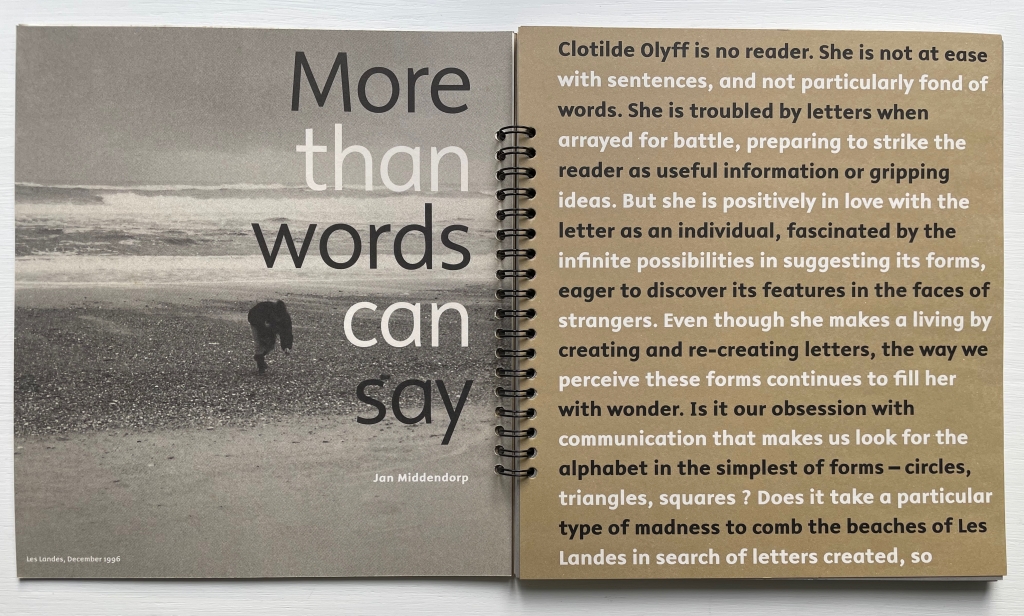

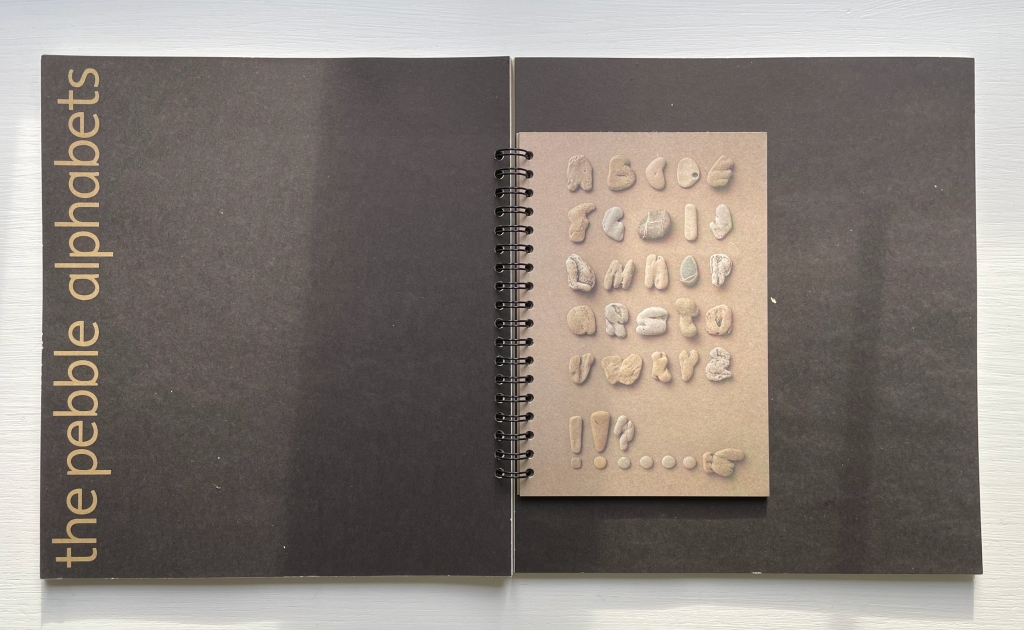

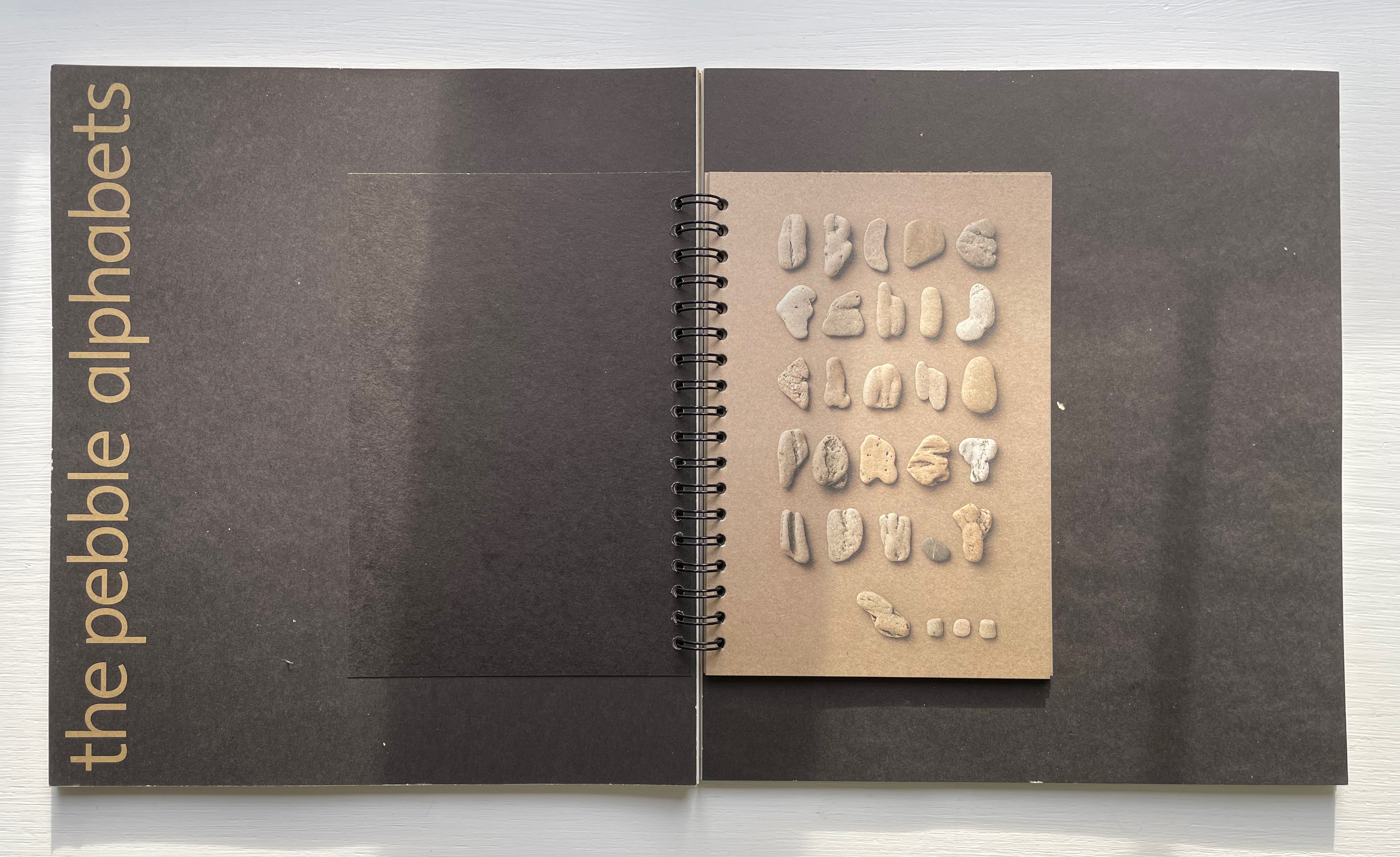

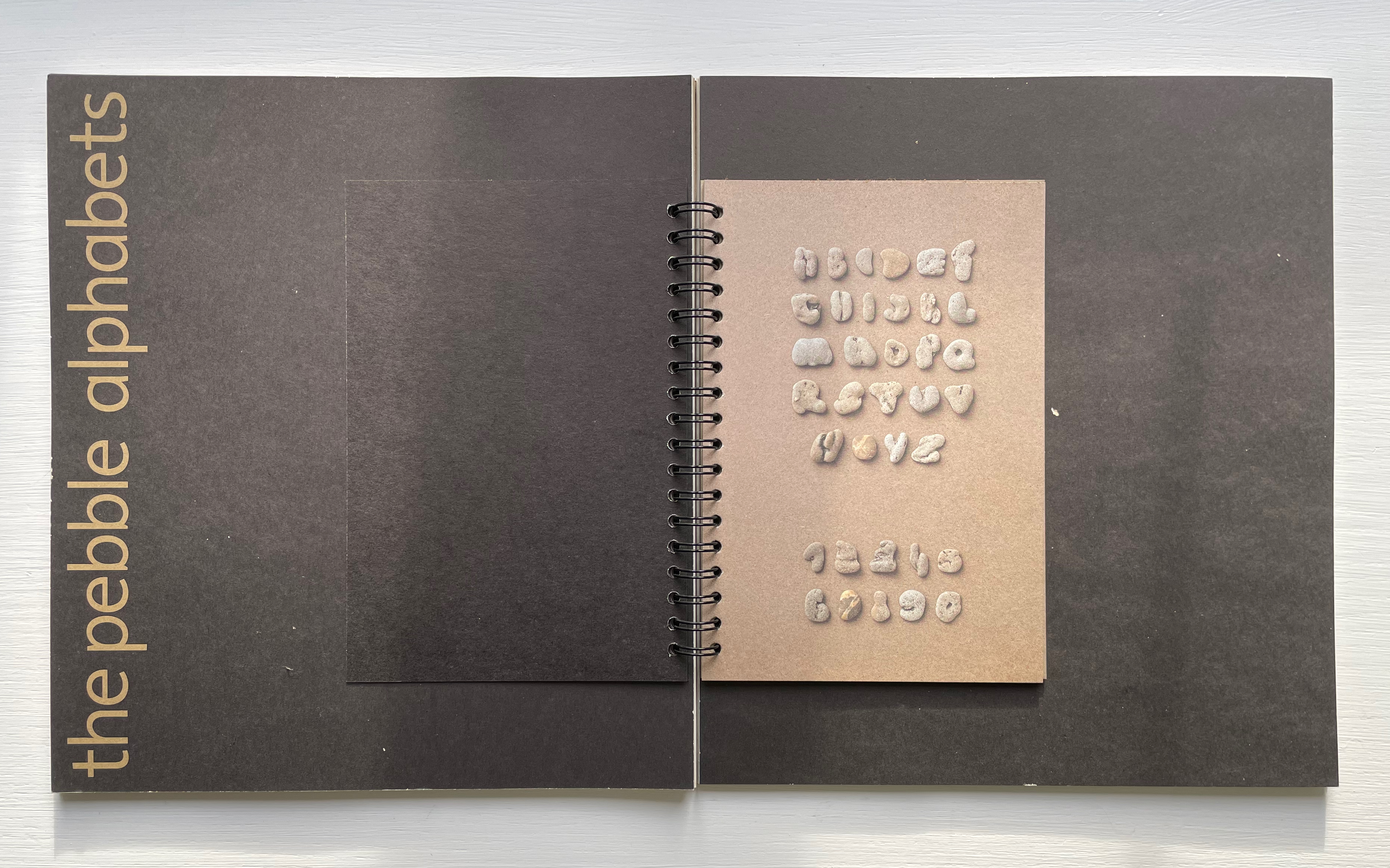

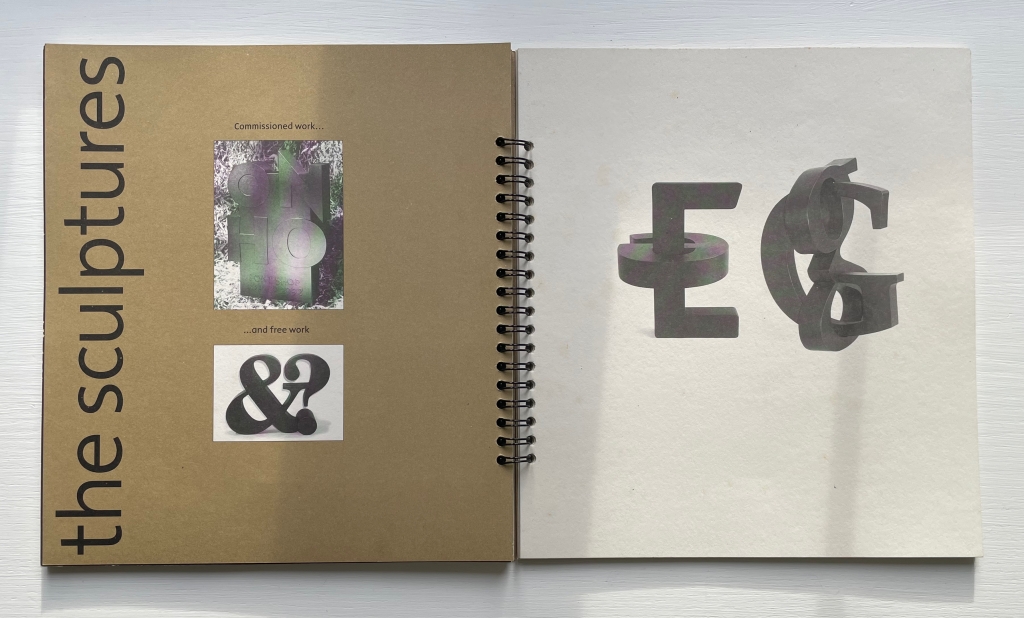

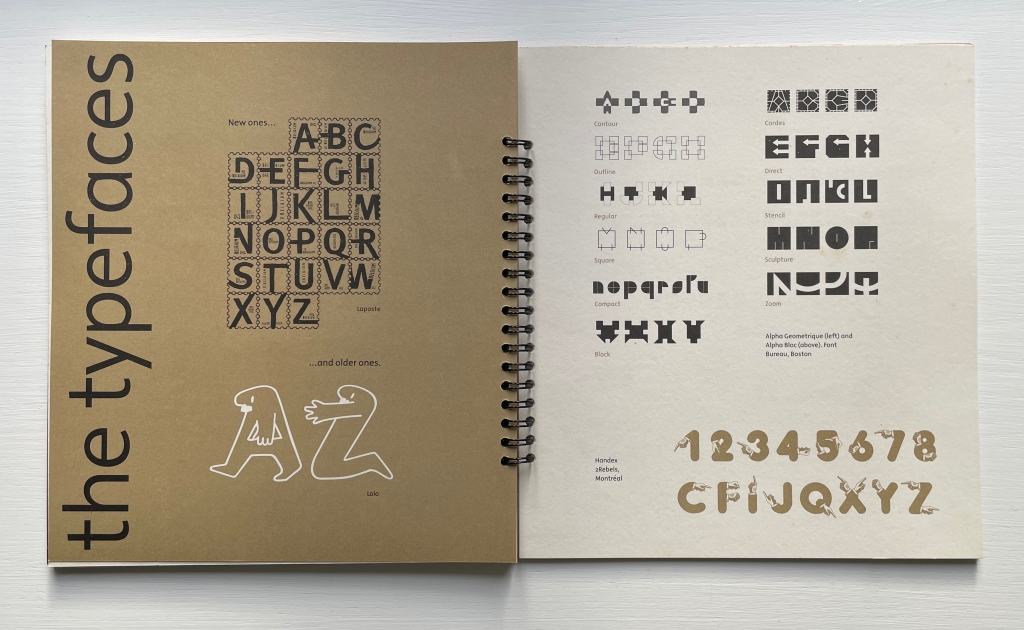

Clotilde Olyff, Lettered : typefaces and alphabets by Clotilde Olyff

Bodil Rosenberg, Vandstand

Chris Ruston, The Great Gathering: Vol. III The Age of Ocean

Emmy van Eijk, Breaking Waves

Phil Zimmermann, Landscapes of the Late Anthropocene

Chinnery, Colin. 1999. “Bookbinding”. International Dunhuang Project. London: British Library. International Dunhuang Project. Formed in 1994, this multilingual collaboration among eight international institutions provides images and information about manuscripts and other artifacts from the Eastern Silk Road. Chinnery is also a multimedia artist.

Drège, Jean-Pierre. “Les Accordéons de Dunhuang”, pp. 195-98, in Soymié, Michel; et al. 1984. Contributions Aux Études De Touen-Houang. Volume III. Paris: Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient : Dépositaire A.-Maisonneuve.

Martinique Edward. 1983. Chinese Traditional Bookbinding : A Study of Its Evolution and Techniques. San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center.

Song, Minah. 2009. “The history and characteristics of traditionalKorean books and bookbinding”. Journal of the Institute of Conservation. 32:1, 53-78, DOI:10.1080/19455220802630743

Zhang, Wenbin. 2000. Dunhuang. A Centennial Commemoration of the Discovery of the Cave Library. Beijing: Dunhuang Research Institute, Morning Glory Publishers.

Zhizhong, L., & Wood, F. (1989). “Problems in the History of Chinese Bindings“. The British Library Journal, 15(1), 104–119.