Your House (2006)

Your House (2006)

Olafur Eliasson

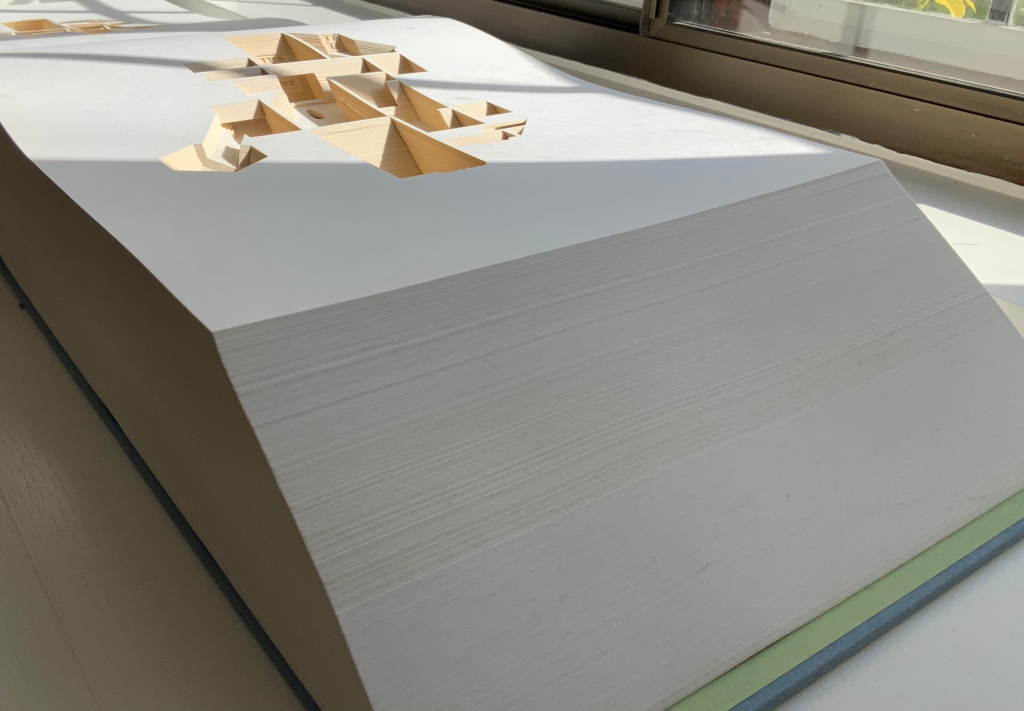

Hardback handbound with 454 laser cut leaves. H273 × W432 × D114 mm. Edition of 225, of which this is #210. Acquired from Carolina Nitsch Contemporary Art, August 2020. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artist.

Your House is a laser-cut model of Olafur Eliasson’s residence in Copenhagen at a scale of 1:85, which means that each page equates to a 220 mm section of the actual house. How do you read a work like this — physically? At the 22″ mark in the video below, the pages fall in a cascade like a flipbook, but for the most part, their size, accumulated bulk and weight — and delicacy — defy that handling. They must be turned slowly and carefully. Your House heeds the task of the arts as posed by the architect Juhani Pallasmaa, “in our age of speed, …to defend the comprehensibility of time, its experiential plasticity, tactility and slowness” (The Embodied Image, p. 78).

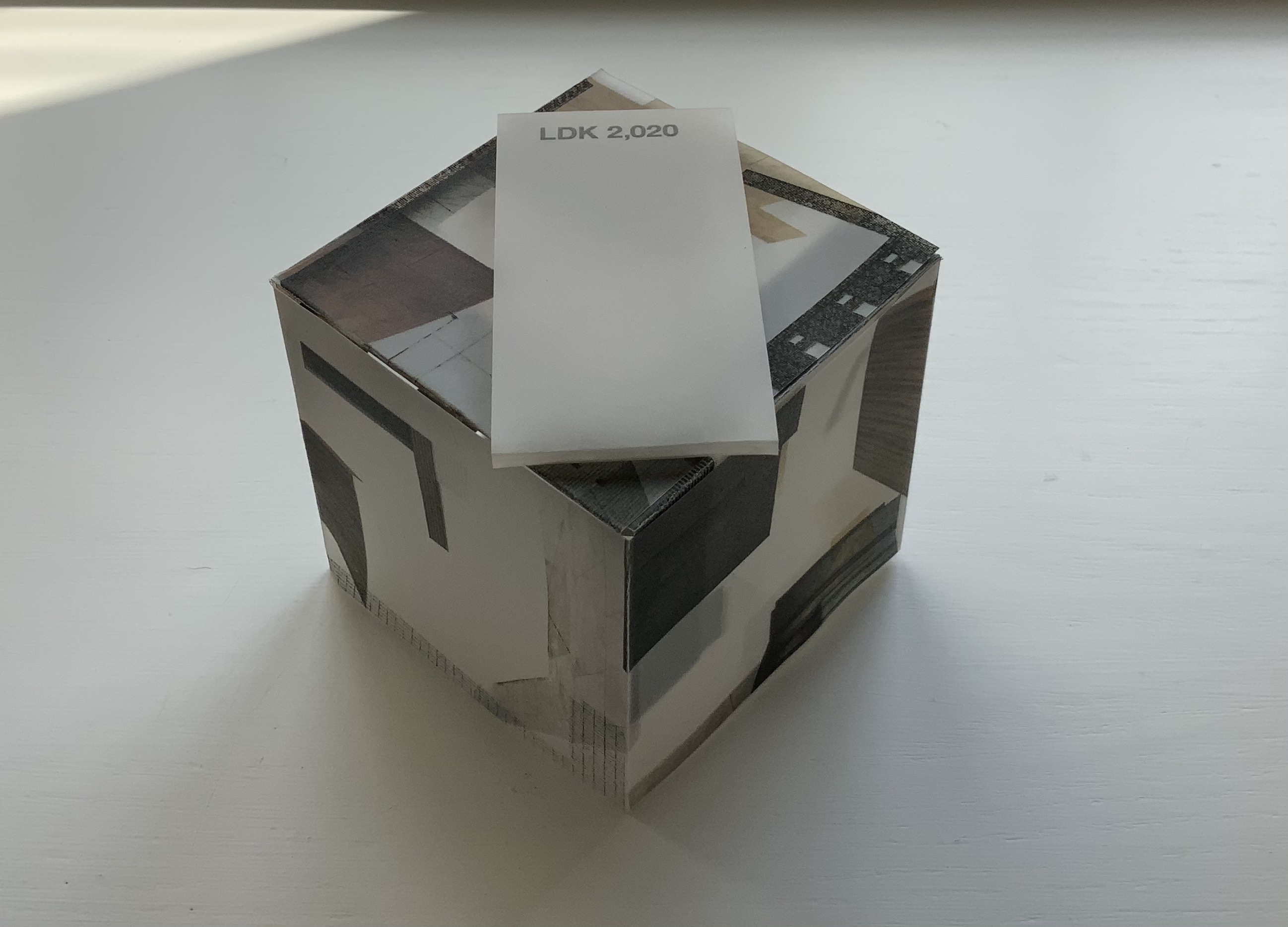

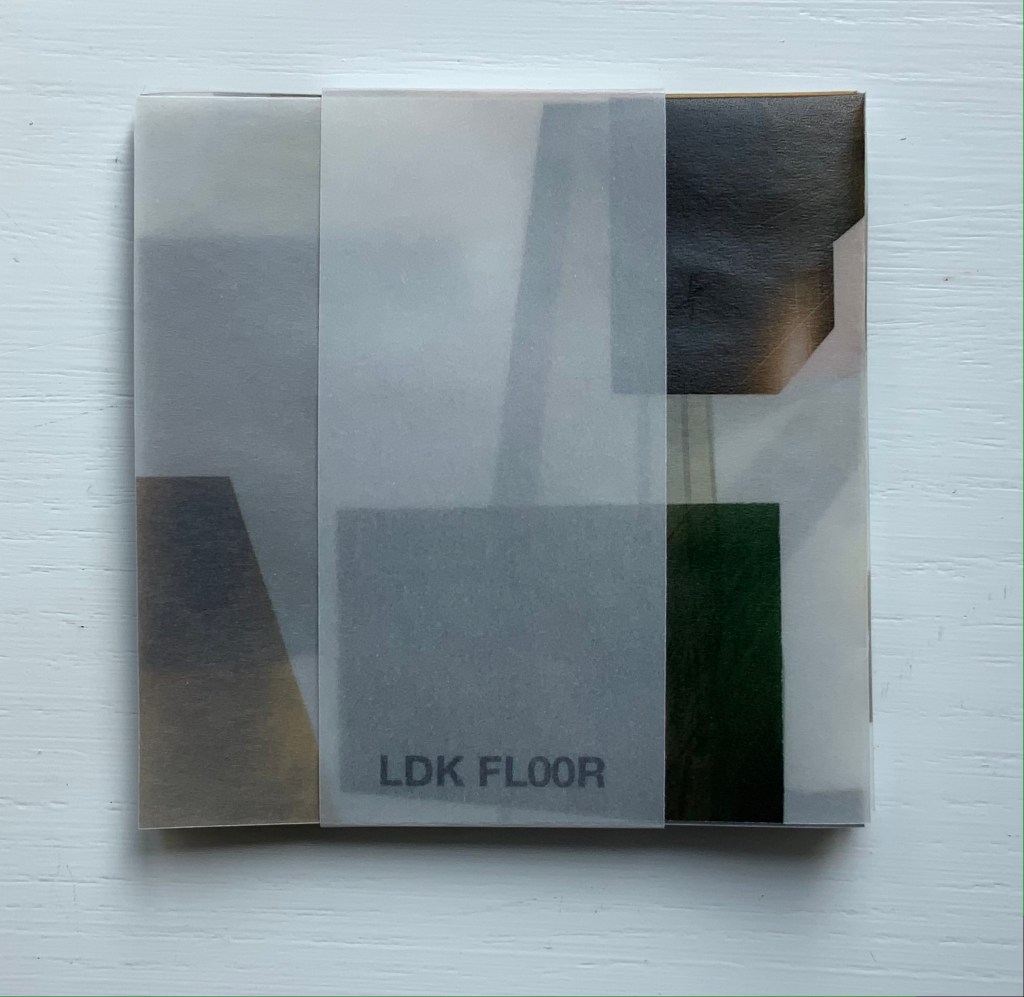

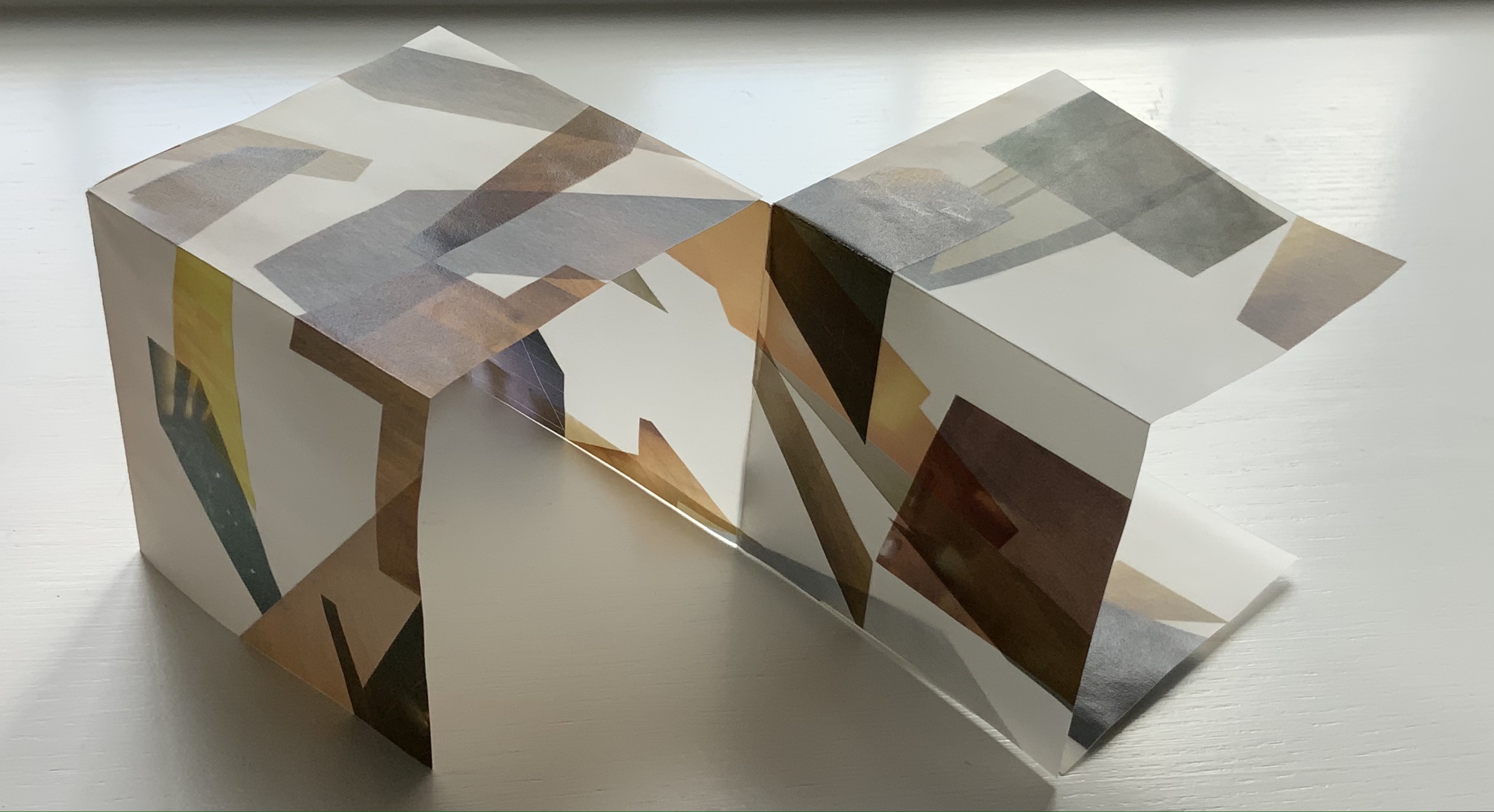

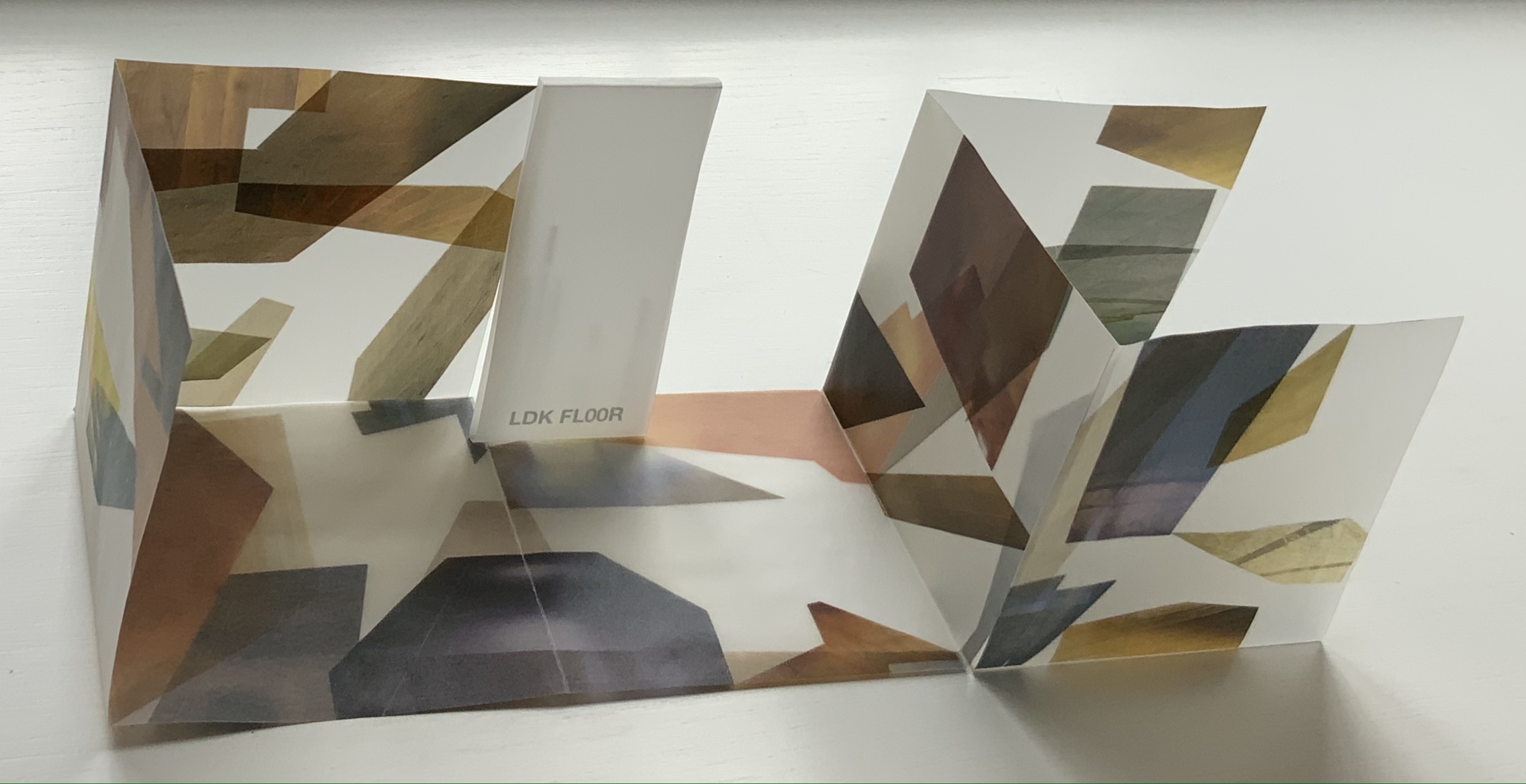

Your House (2014)

Studio Olafur Eliasson

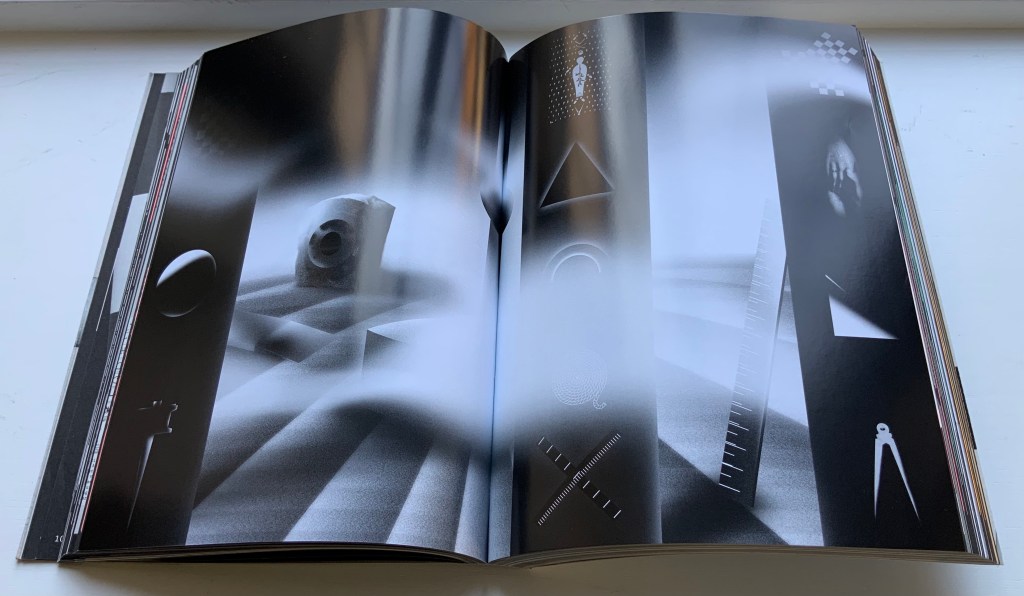

As you move from Your House‘s entrance to its exit, the outlines of walls, floors, stairs, doors, domes, windows, fireplaces and bookcases tremble in the air. Is this what Gaston Bachelard calls “the material imagination”? What Juhani Pallasmaa calls “the embodied image”?

Video: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Studio Olafur Eliasson.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Studio Olafur Eliasson.

There is something meditative about reading Your House properly. The cautious repetitive turning of pages can induce a daydream of inhabiting the space revealed. At some point in turning the pages, the empty shapes begin to become “your house”. Perhaps you see yourself moving through its spaces, and imagined furnishings occupying its rooms.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Studio Olafur Eliasson.

Or perhaps as in the sequence above — the end of one room (or chapter or part) and the start of another — you become a ghost — with all the work’s past and future readers — passing through the walls.

Video: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Studio Olafur Eliasson.

In The Poetics of Space, Bachelard writes of poetic time and prosodic time. The one is vertical, a spot in time, a frozen moment; the other is horizontal, a narrative, a continuity. But they are not mutually exclusive. Your House is a site where poetic and prosodic time occupy the same space. More than that, it is a site where temporality, as Eliasson puts it, “becomes something you perform by involving yourself physically over time” and thereby you become, “in the end, the createur” (“Not how, but why!”, p. 108).

Eliasson’s house in Hellerup, a suburb of Copenhagen, was advertised for sale in 2024. For comparison with the book, you can see photos of the exterior and interior here. Also, with thanks to Byopia Press, an X-ray documentation of the book can be found here.

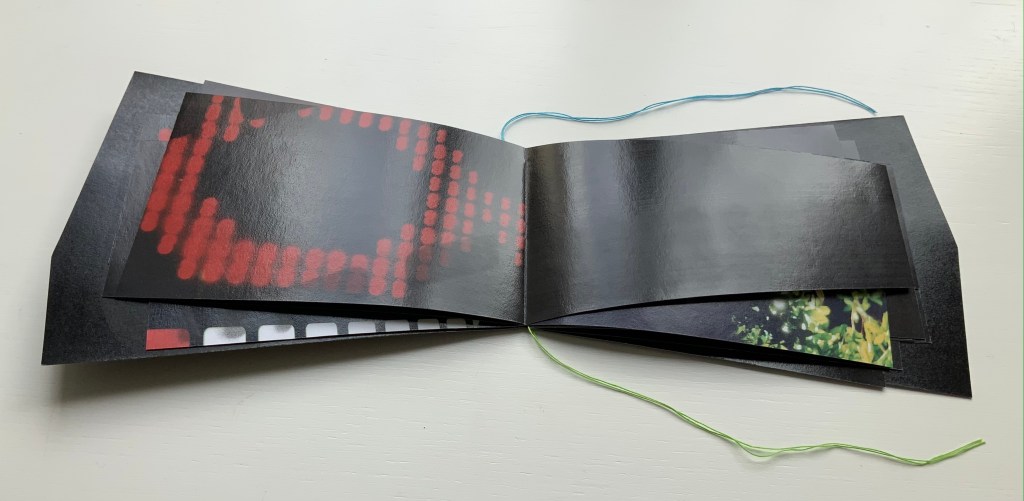

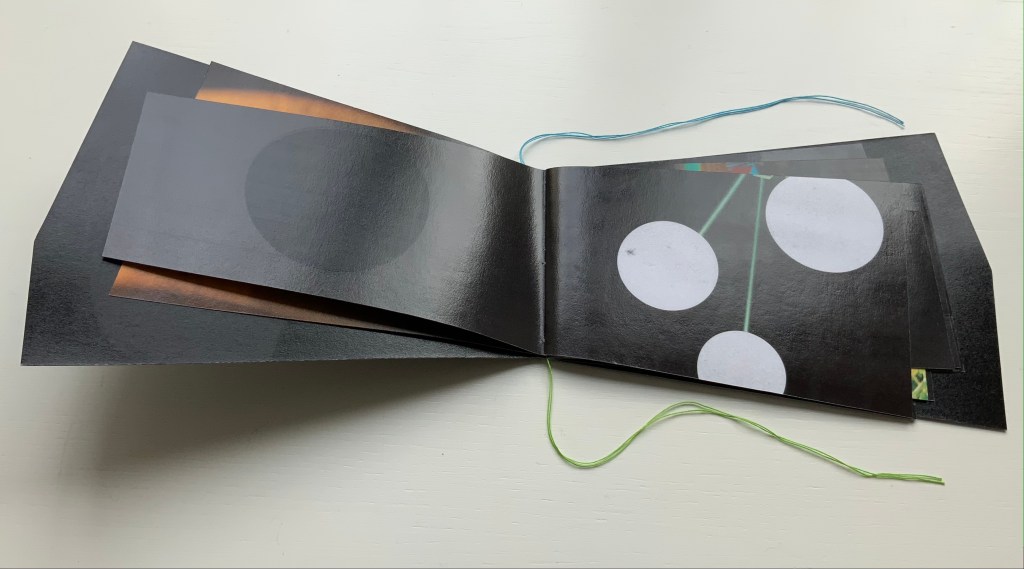

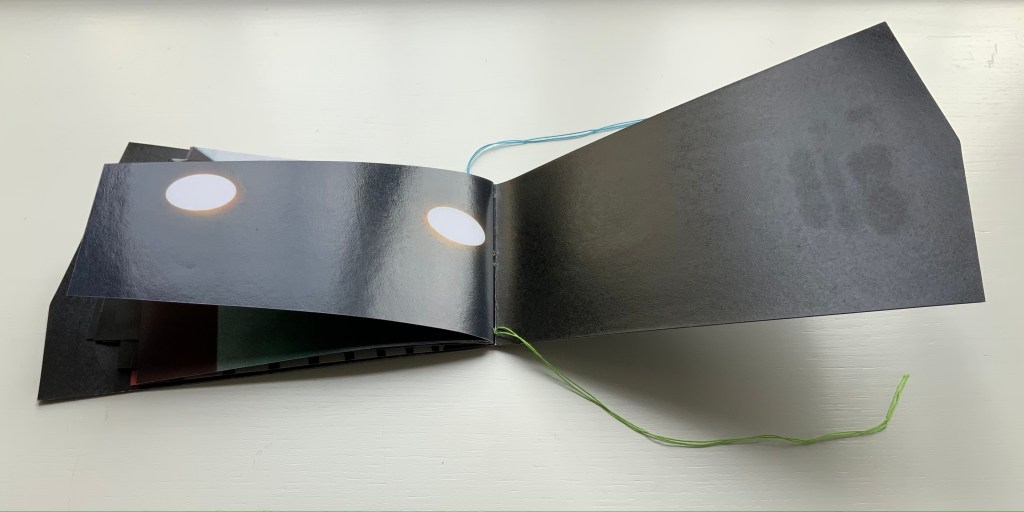

Contact is Content (2014)

Contact is Content (2014)

Olafur Eliasson

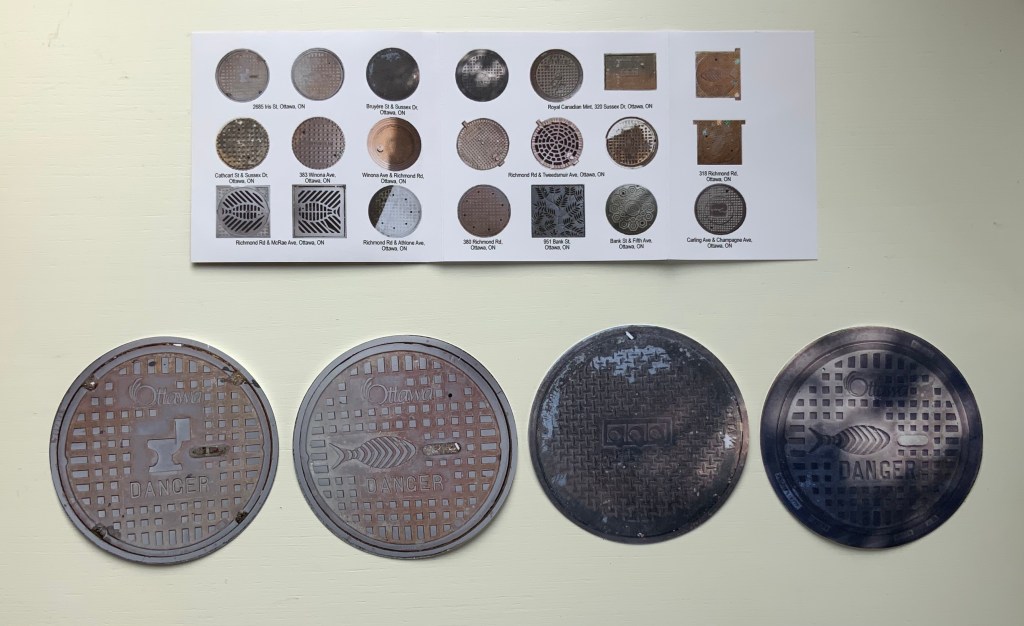

Casebound, cloth mesh-covered board. H345 x W310 x D50 mm, 416 pages. Photos: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of the artist.

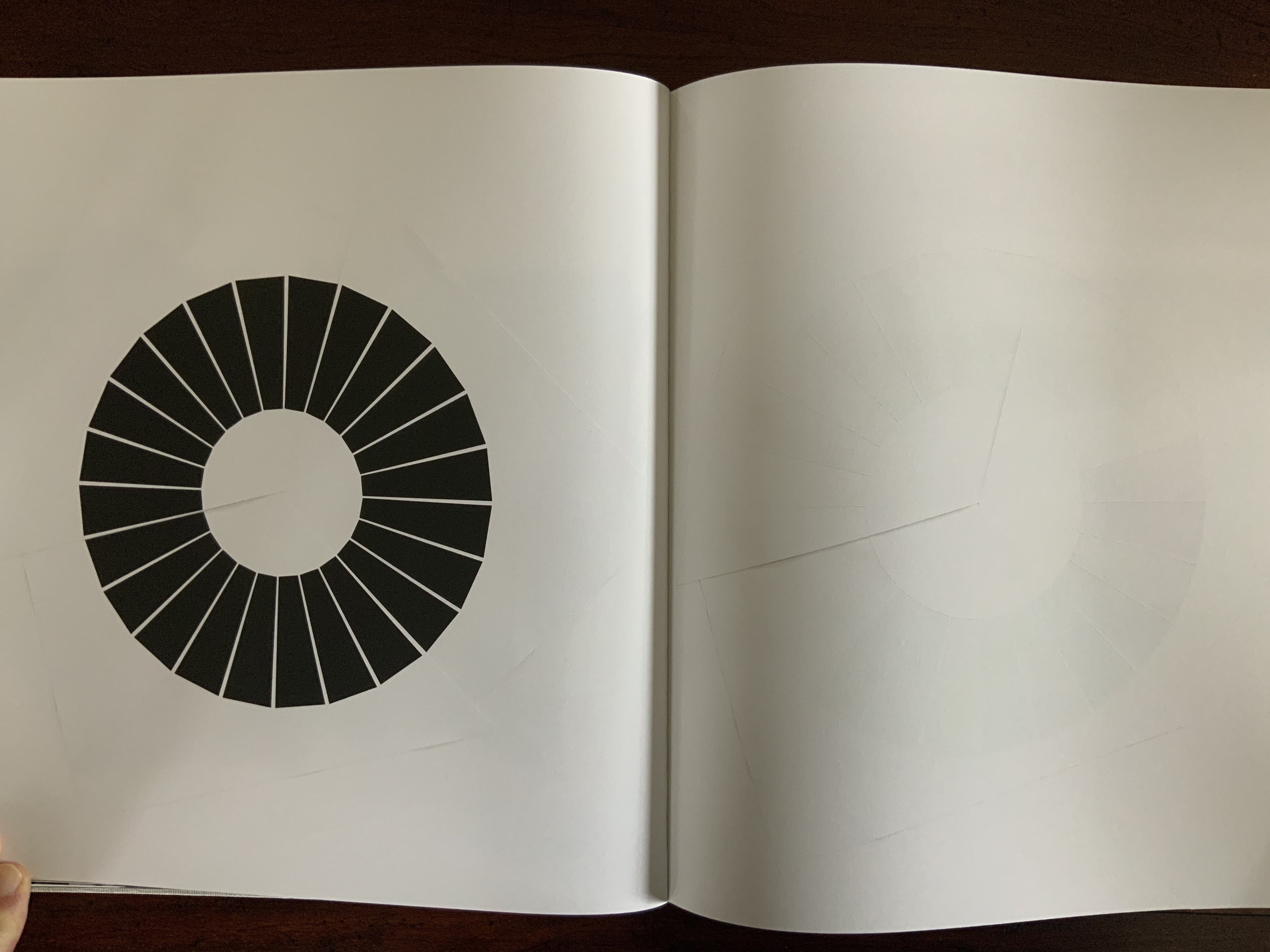

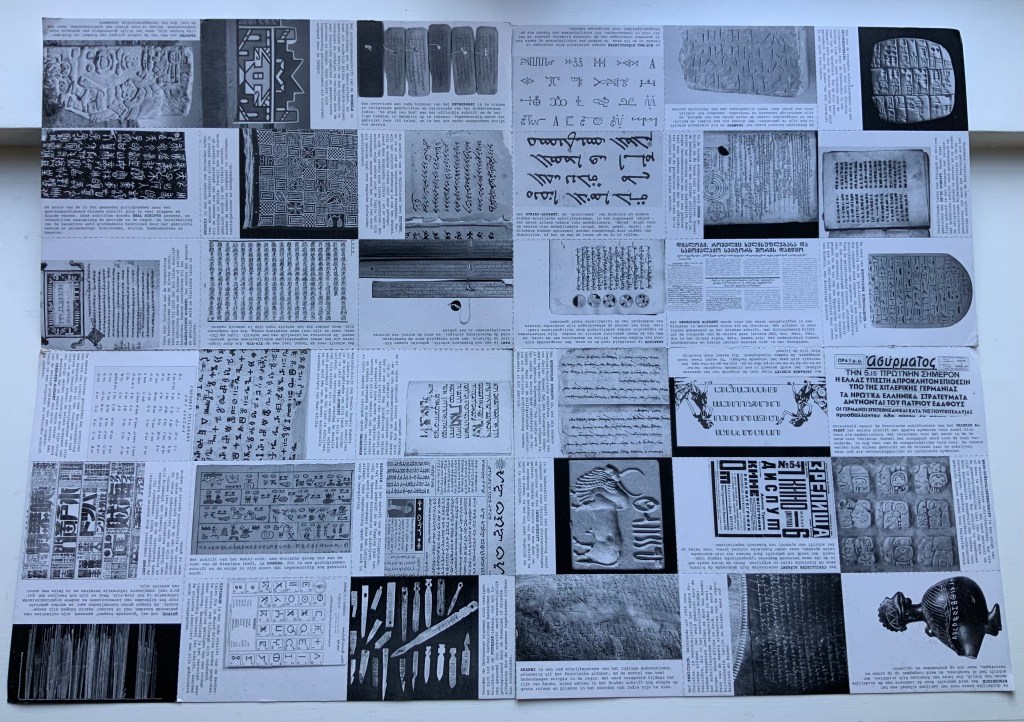

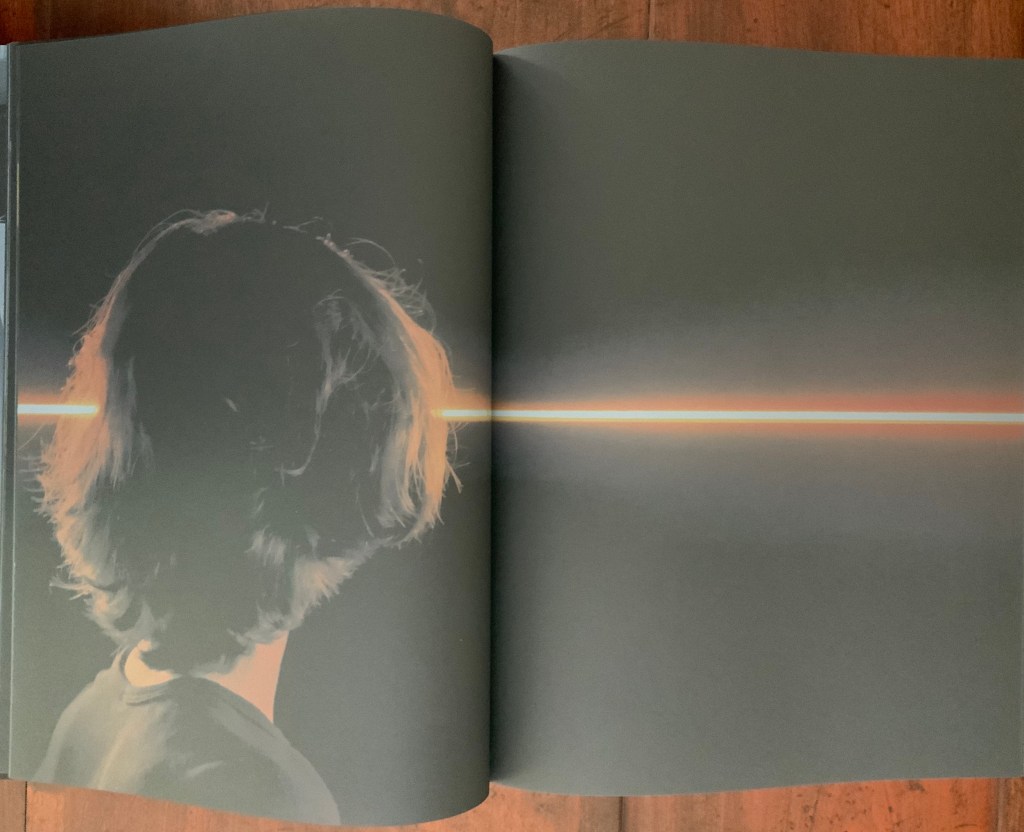

Like Your House, this work requires a slow, careful interaction in which viewing becomes learning the language of Eliasson’s images, discovering its syntax and exploring its rhymes and rhythms — reading the content presented with it. Unlike Your House, which focuses on contact with one source of content, Contact is Content draws on multiple sources: photographs Eliasson took in Iceland between 1986 and 2013 as well as images from his other projects and artworks. Over 80 different series make up the content of this work. The overwhelming number of round images — artificial and natural — in Contact is Content might suggest that Eliasson is completely sold on Bachelard’s pronouncement in The Poetics of Space that all being is round. But Eliasson’s world is spikier.

Within Contact is Content, images converse with one another — over near and far subjects, over aerial and ground level perspectives, over contrasting textures, over colors and their absence or presence, over artifice and nature

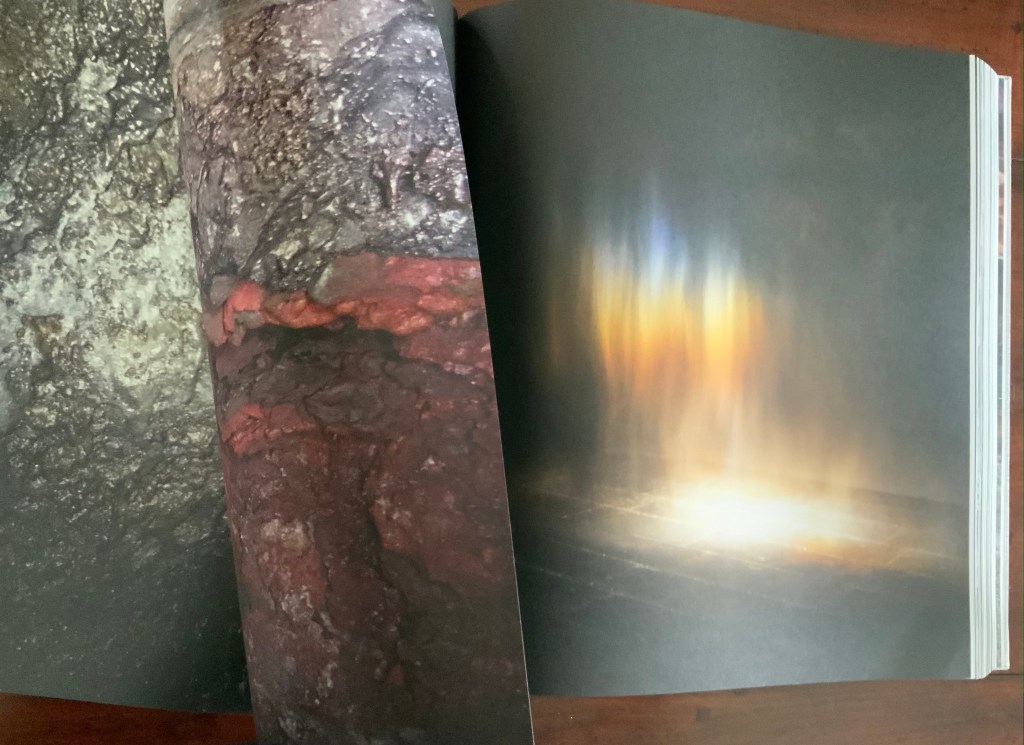

Often the conversations are reverse echoes: the reflective surface of blocks of ice echoes that of basalt.

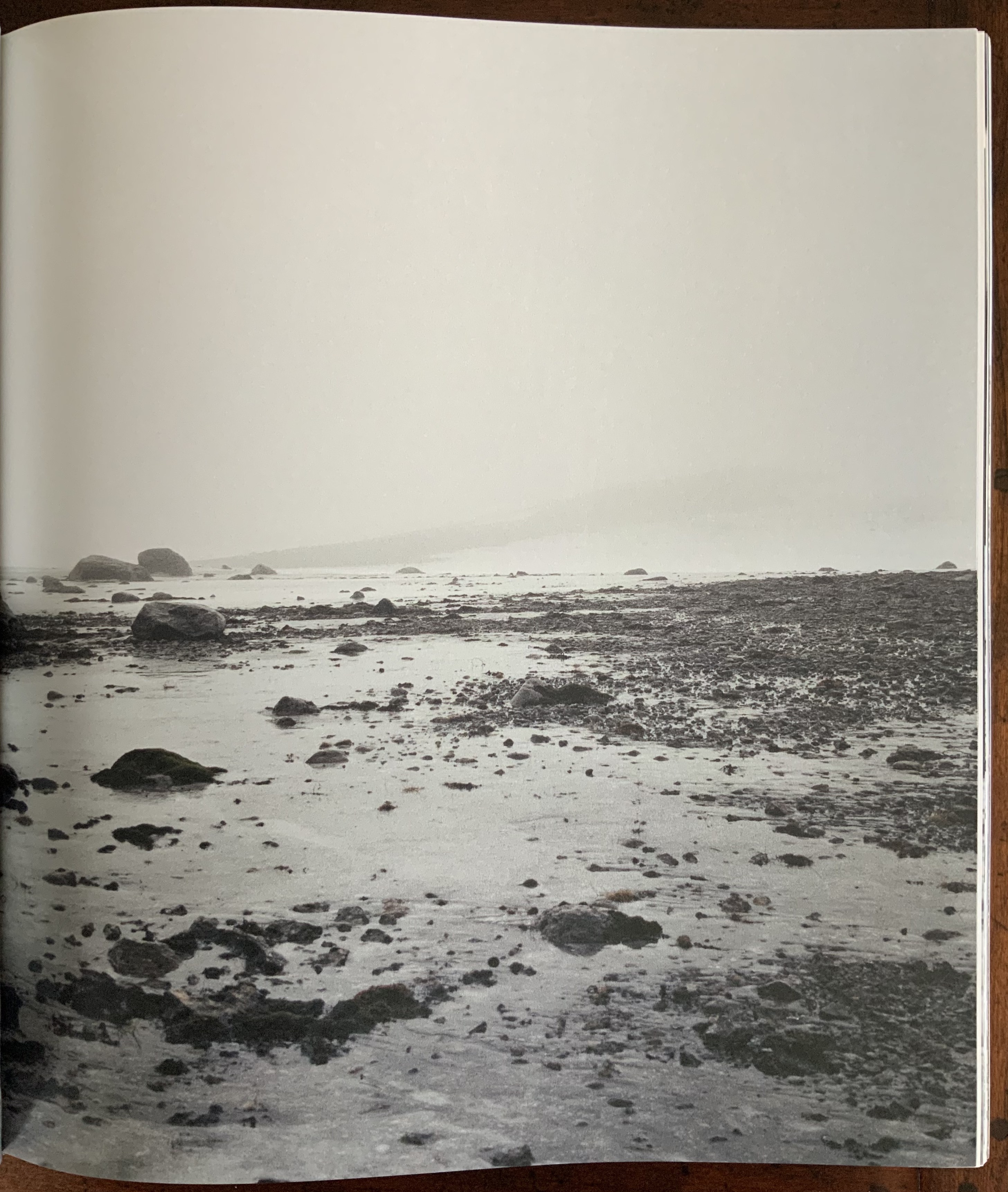

The echo of near and far becomes a theme in itself: black-and-white aerial views of landscapes elide into black-and-white close-ups.

The absence and presence of color also emerges as a theme in its own right that interweaves with that of “near and far”: waterfalls without color vs waterfalls with the barest hint of color; close-ups of rocky terrain without color vs those dotted with intensely green or blue flora.

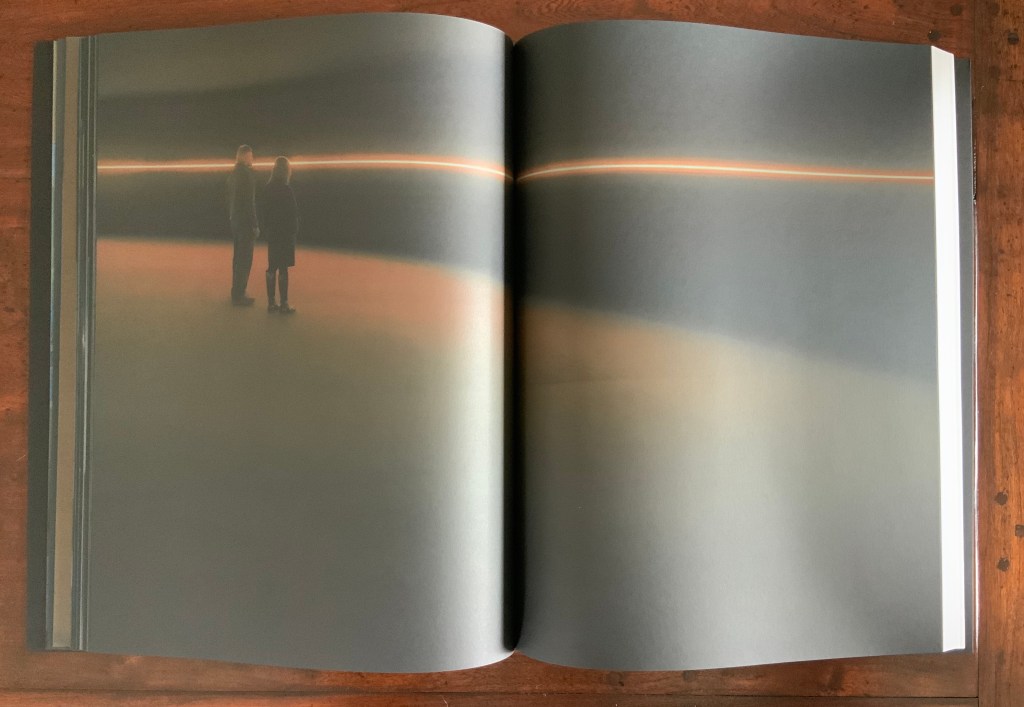

Some reverse echoes are the artificial conversing with nature: a gallery room containing a construction pumping water upwards over four levels echoes an Icelandic waterfall; or shorescapes under fog echo human outlines swallowed up in gallery rooms flooded with color-lit mists. Down to up; outside to inside; black-and-white to color; nature to artifice. And back.

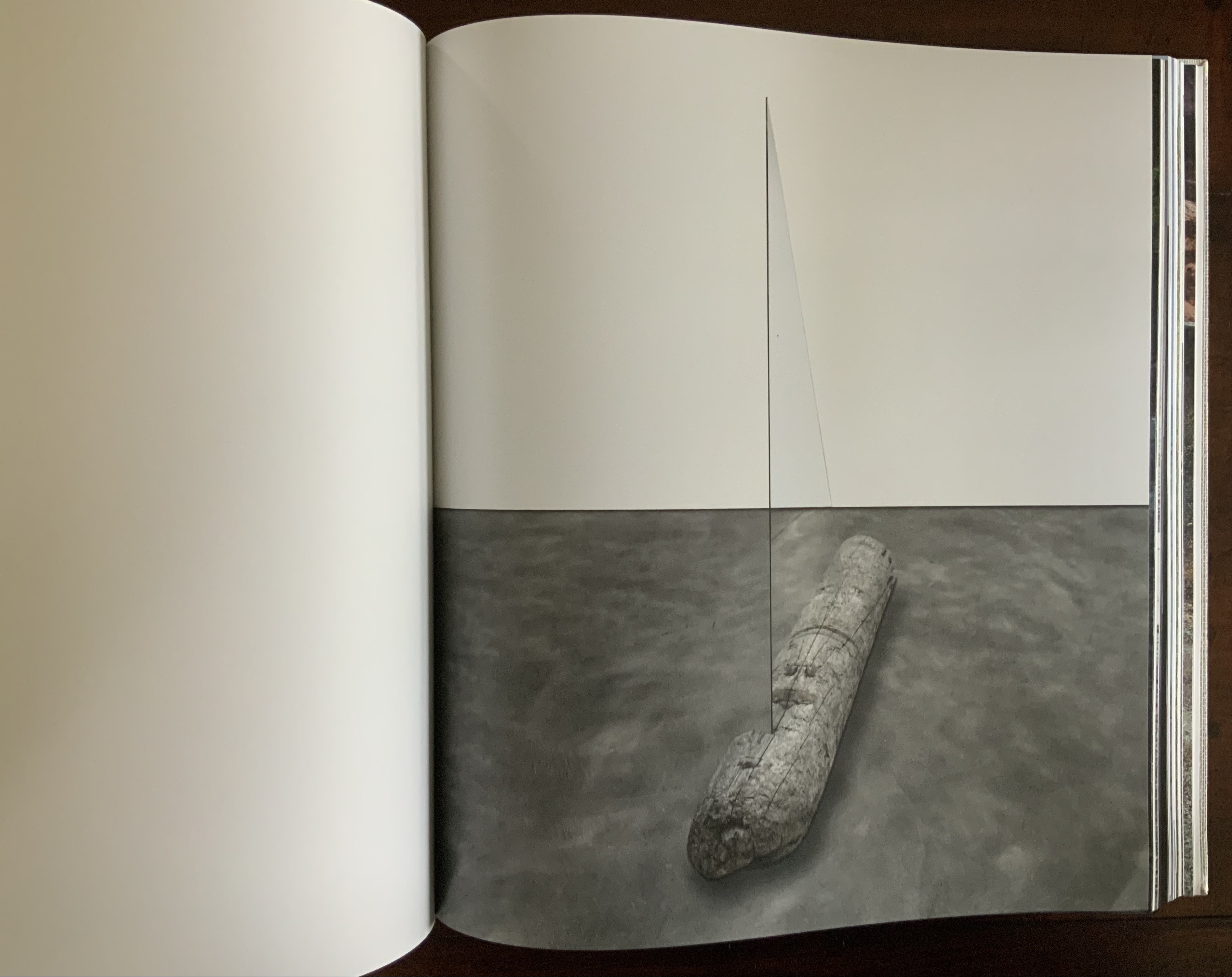

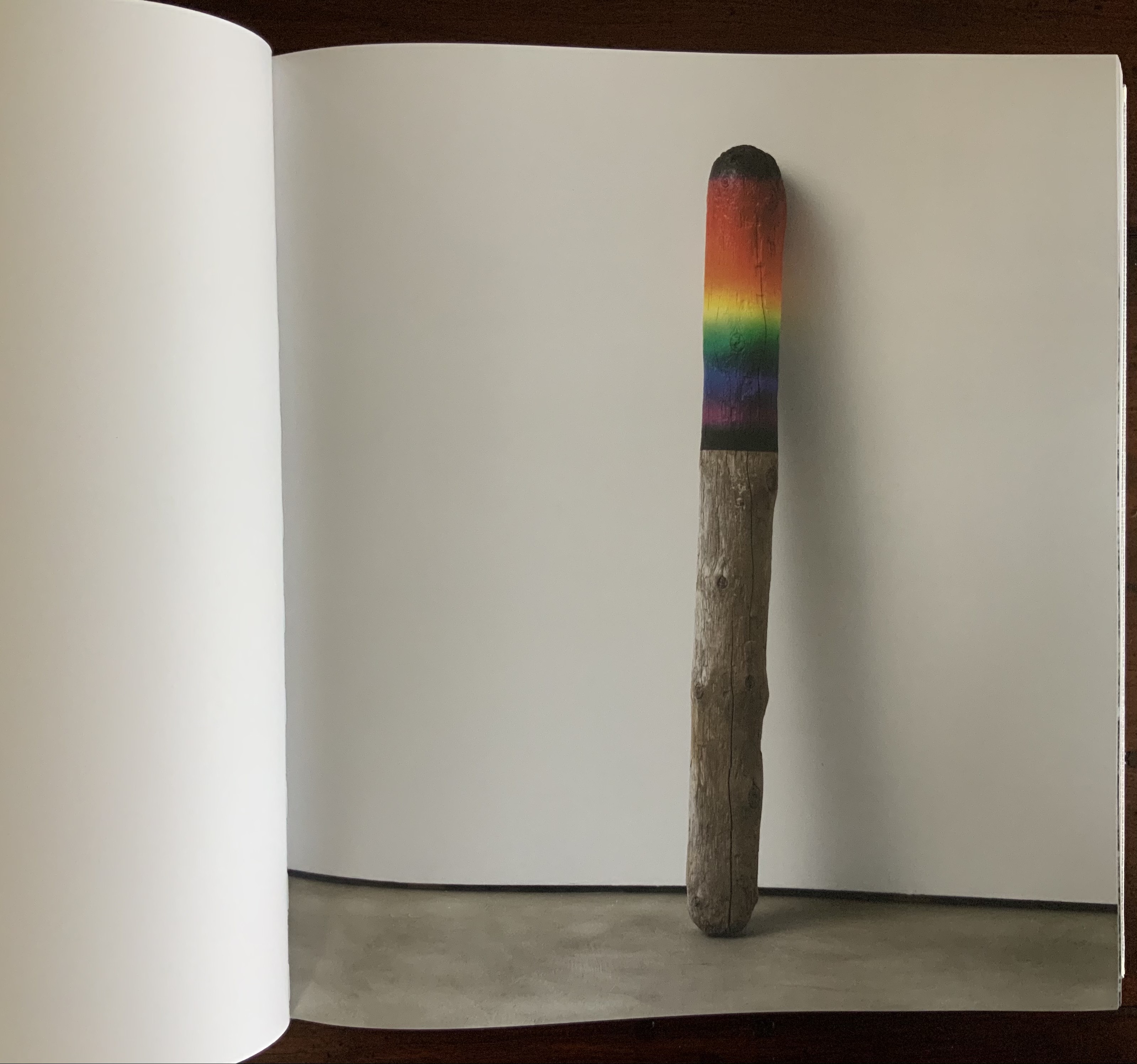

Some of these artifice/nature echoes are compressed into one image: a brightly half-painted stick of driftwood echoes the multiple color wheels used to punctuate the stretches of landscape images.

Other echoes occur within the span of artifice (whole color wheels echoed by sliced black ones) before colliding with nature (a piece of driftwood impaled by a glass triangle) and then jumping back to artifice (round mirrors bisected at floor and wall and cascading upwards to be bisected by wall and ceiling).

Some echoes occur across dozens and dozens of pages. Still others occur in the single turn of a page.

These are but a few of the themes that Eliasson weaves into a narrative with his images, artworks and projects. Every encounter with this book as container seems to reveal a new theme.

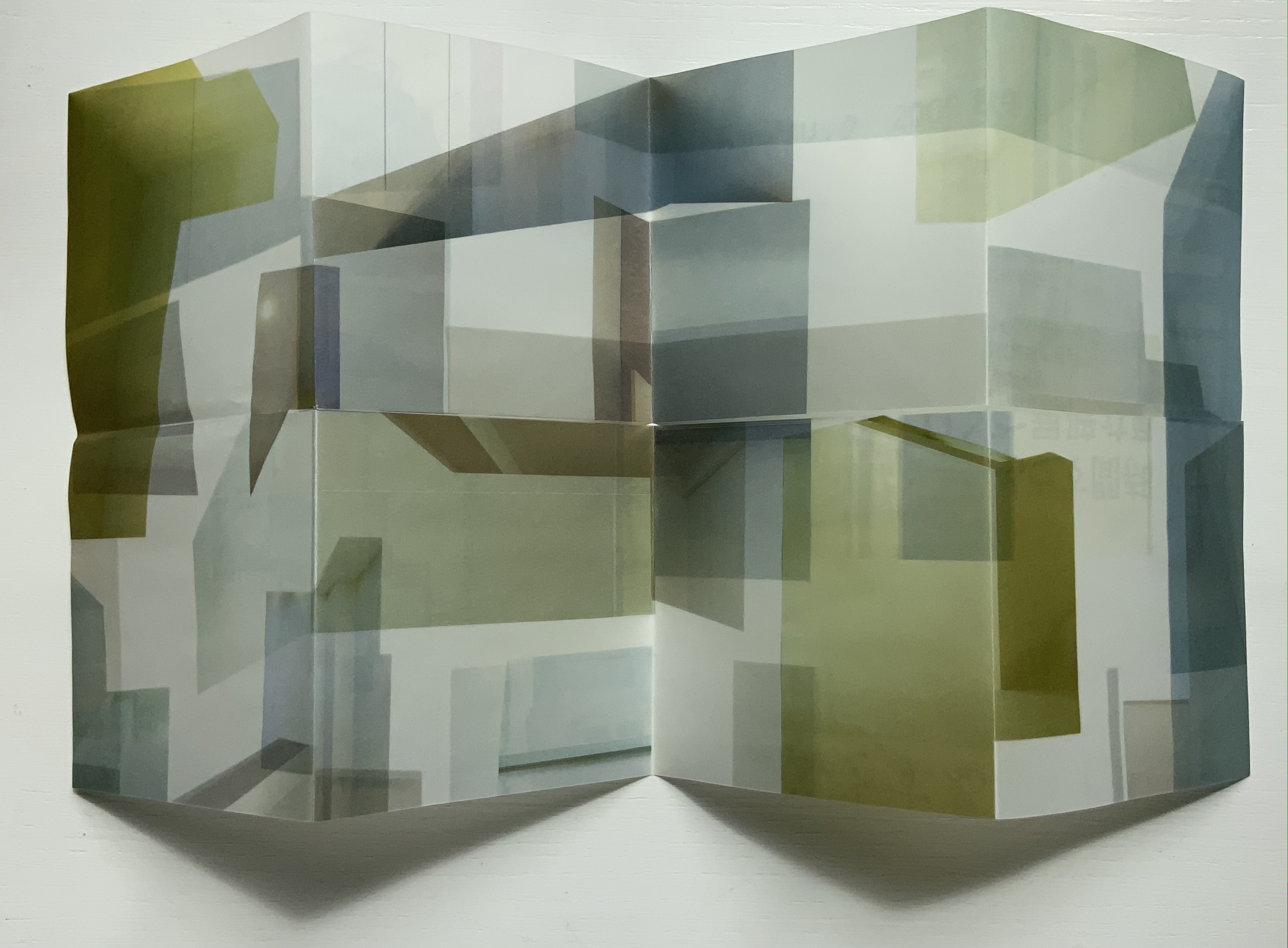

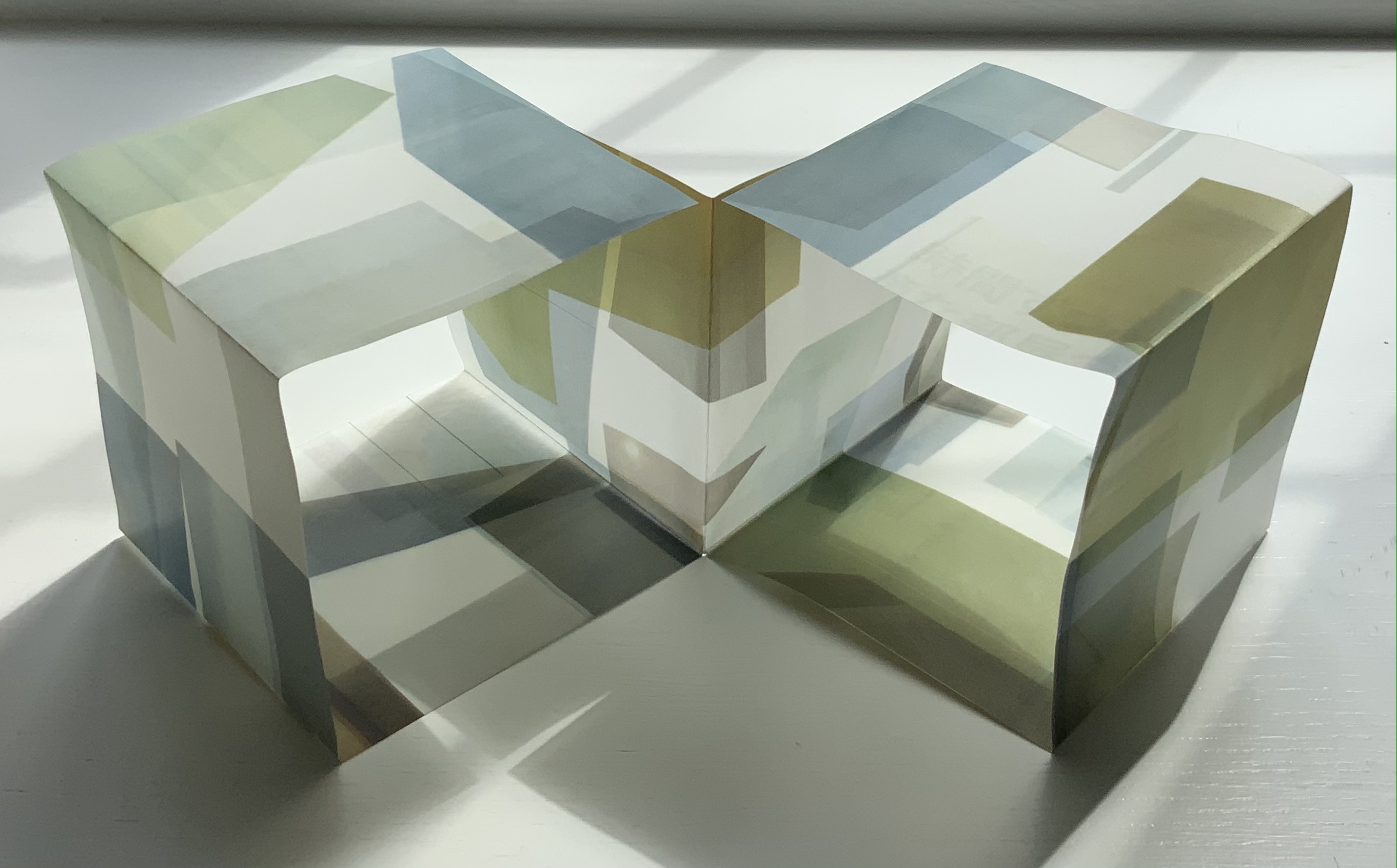

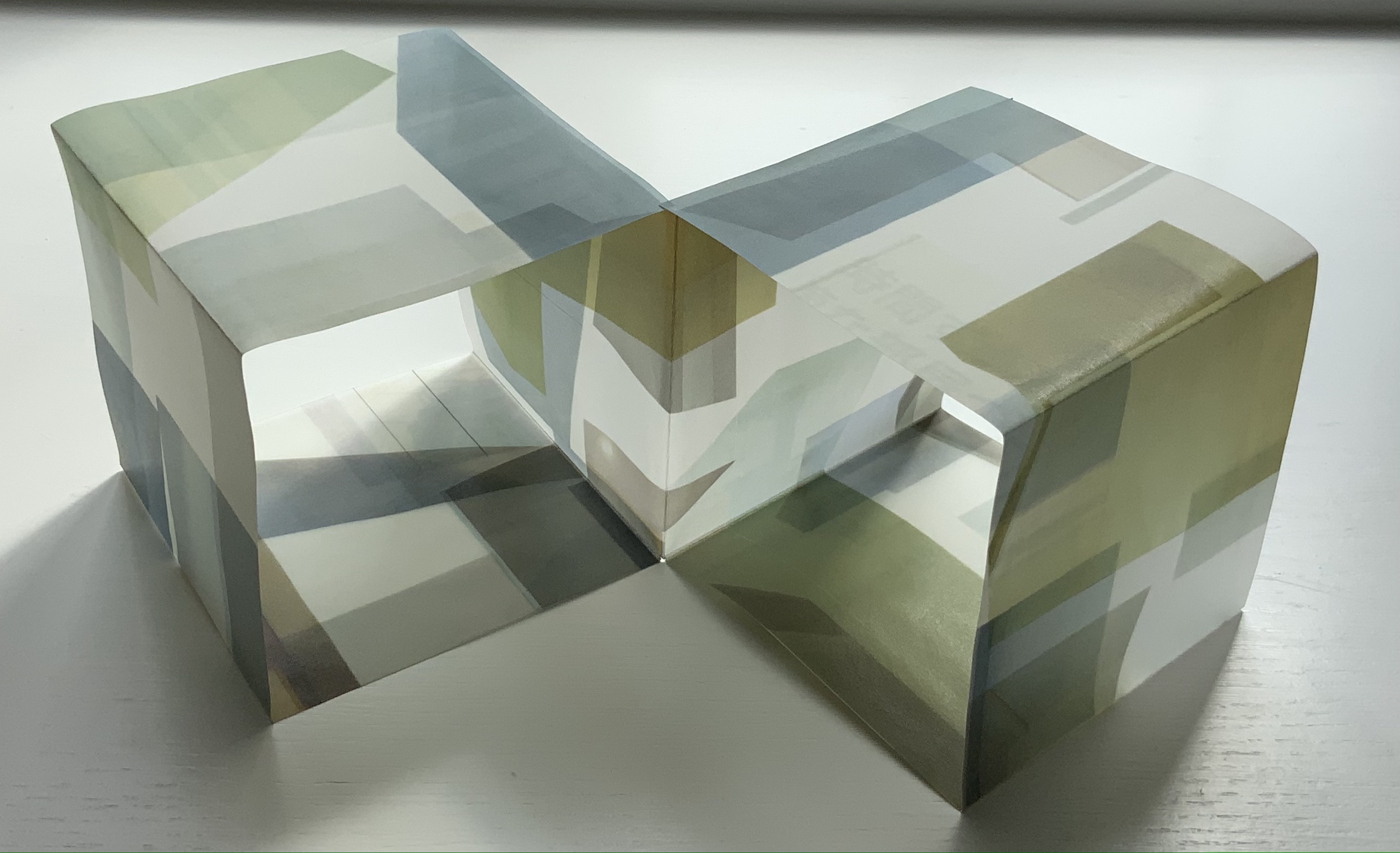

Contact (2014)

Contact (2014)

Olafur Eliasson

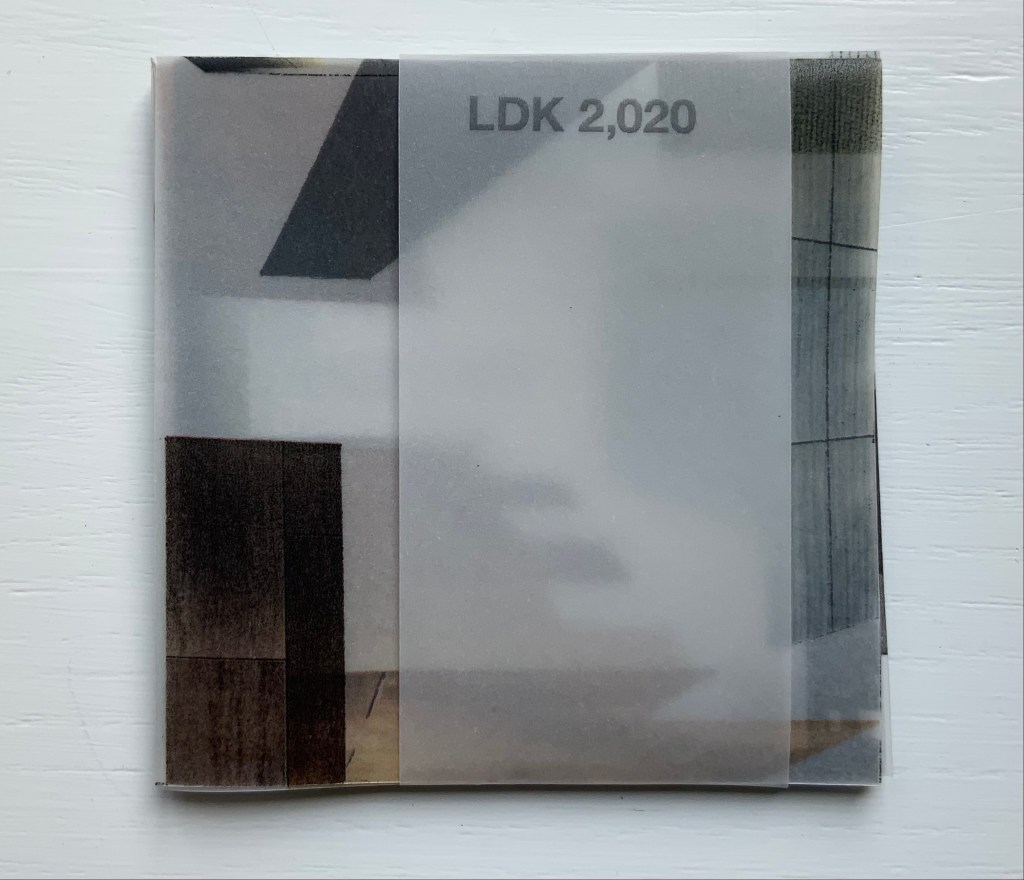

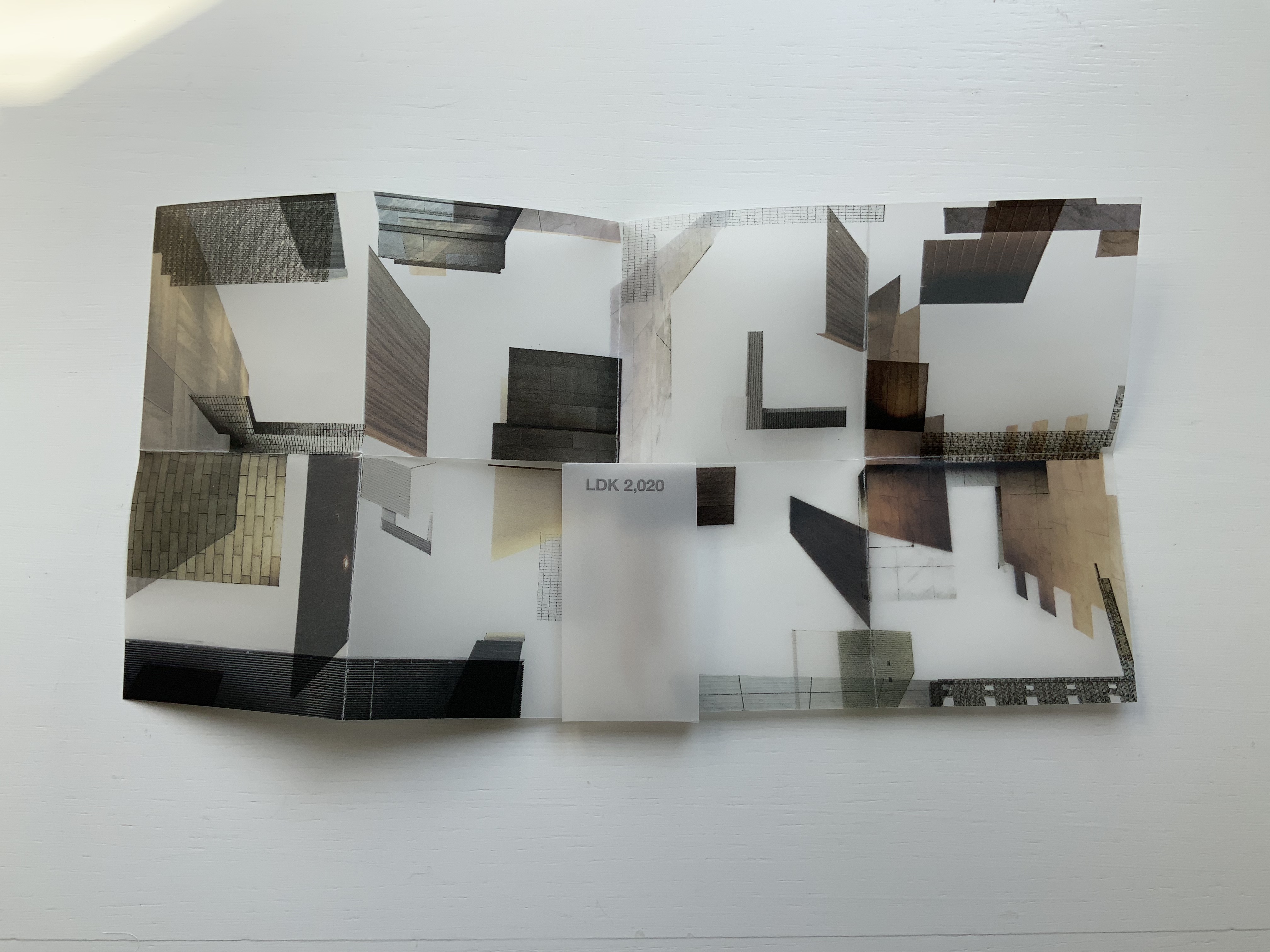

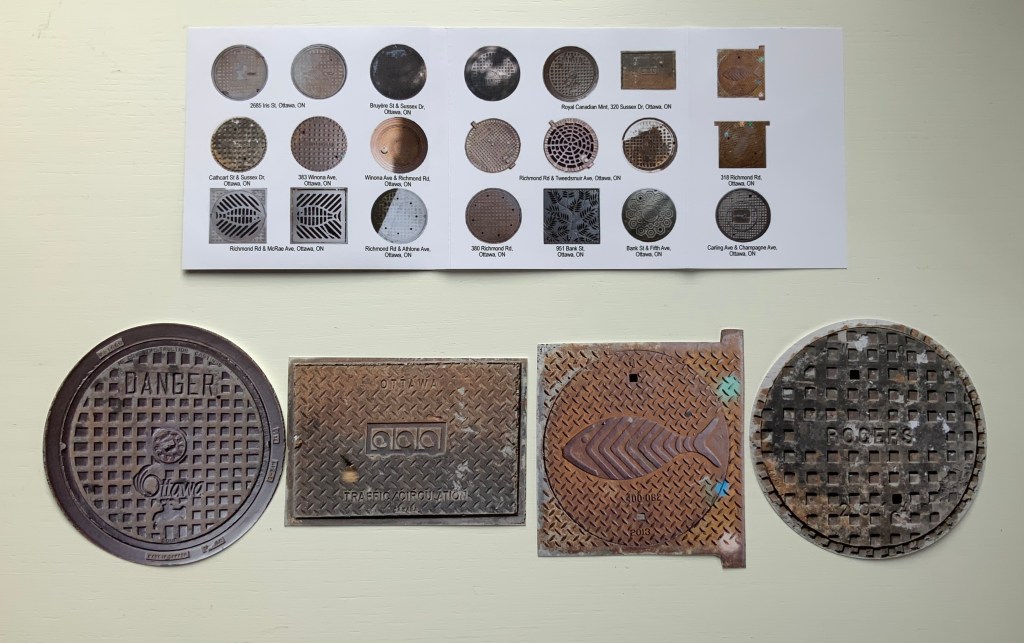

Front and back covers and center spread of exhibition catalogue in paperback. Designed by Irma Boom. Acquired from Artbooksonline.eu, 27 September 2020. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with permission of Studio Olafur Eliasson.

Contact interprets the eponymous site-specific exhibition, commissioned by the Fondation Louis Vuitton and held in its Frank Gehry-designed building, 17 December 2014 through 23 February 2015. Here is the artist’s statement on Contact:

being in contact is the opposite of being disconnected. to be in contact is to be aware of the consequences that your actions have in and on the world. contact is about experience rather than consumption. to be in contact is to be in touch with the good things in life as well as with the difficult things in life. contact can be a greeting, a smile, the feeling of another person’s hand in your hand. contact is not a picture, it is not a representation; it is about your ability to reach out, connect, and perhaps even put yourself in another person’s place. for me, contact is where inclusion begins. contact is the highest luxury of all. olafur eliasson

Contact is also between page and page. Eliasson and Irma Boom, “the queen of books”, have worked together on several works. Boom’s mastery of the full bleed, double-page spread and gutter is the perfect match for this volume that brings the virtual into contact with the material.

Contact is also between paper and ink, between black and white as well as between dark and light when the book’s fluorescent title glows in a darkened room. The cover’s fluorescent ink, however, is not integral enough with the rest of the book to rise above an amusing touch; whereas contact between black and white extends to the division of the book into black and white halves.

In the first half of the book, photographs on entirely black paper present a codex-experience of the exhibition. In the second half of the book, drawings take the viewer behind the scenes of the exhibition’s design and, retrospectively, train the eye to read the book as exhibition.

This incorporation of design drawings draws attention to time, and Contact is very much about our perception of time. In her book Binding Space: The Book as Spatial Practice, Marian Macken refers to “the tenses of the book”. Especially when presented in a book, architectural plan drawings “are not fixed in their sequence, but instead may be read and interpreted as existing within a range of times, such as the time of their making, of the present of the reader, the future they may refer to, and the contextual moment of apprehension” (p. 157). In the case of this “book of the exhibition”, published to coincide with the exhibition, the plan drawings and photographs exist in the exhibition’s past and present. For an exhibition attendee, they exist as a reminder of a personal past performance of contact with the exhibition. For attendees and non-attendees, they bring the exhibition’s past and future together in the present in a performance of contact guided by the architecture of the book.

How appropriate it is that, in her essay in the book’s white section, Caroline A. Jones writes, “Personally, I will not have seen the installations that the present text accompanies” — as is/will be the case for many of us experiencing Contact only in its book form. Jones’ essay is entitled “Event Horizon: Olafur Eliasson’s Raumexperimente”, which confirms that contact is not only about perception of time, but of space as well. While Jones teases out how the exhibition will play/plays/played with the astrophysical conundrum, she cites a comment from Eliasson in conversation that captures a simpler view: “There is a tradition of the horizon as a boundary between the known and unknown. But as you approach, it fades in, or comes into your experience. You can think of it as a space” (p. 133).

Space — which brings up the awkward point of the setting in which the exhibition occurred. Since the Renaissance, imagination in art and science has sat sometimes uneasily, sometimes too easily with wealth and privilege. There may be nothing democratic in Eliasson’s expensive, spectacular art, but Contact’s fusion of science, art, nature (Earth-bound and cosmic) and social connectedness contrasts pointedly and paradoxically with its setting in the opulent property of a global luxury brand — “the blandishments of follies and bling” as Jones puts it. As Eliasson’s artist statement asserts: “contact is about experience rather than consumption….is where inclusion begins….is the highest luxury of all”. But without the Fondation’s patronage, the experience of Contact in situ or even in these artfully designed pages would be denied.

Somewhat less reconcilable is the statement “contact is not a picture,… is not a representation”. Placing contact with art (a picture, a representation) in opposition to contact through human touch and empathy is not quite right. Just as Your House resonates with the perspective of the physicist/philosopher/humanist Bachelard, for whom the image is language, so too does the language of Contact as exhibition, images, objects, book — and experience. We cannot have contact without it.

Studio Olafur Eliasson. 2015. Olafur Eliasson, Contact, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris 2014 – 2015.

Further Reading, Looking & Listening

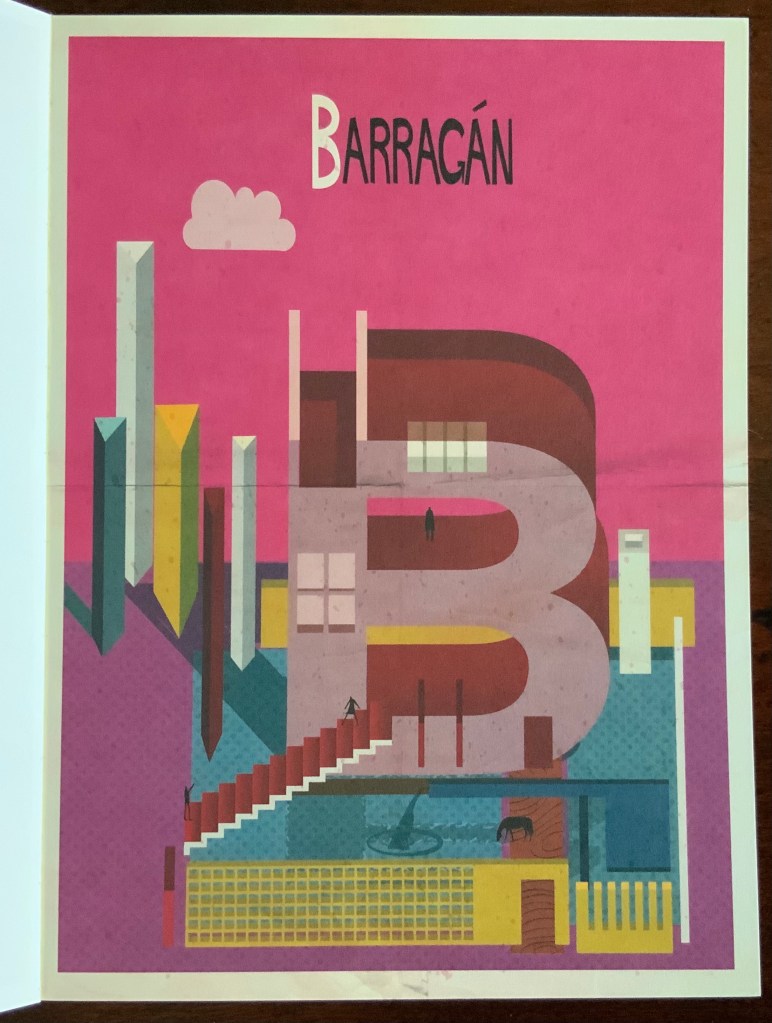

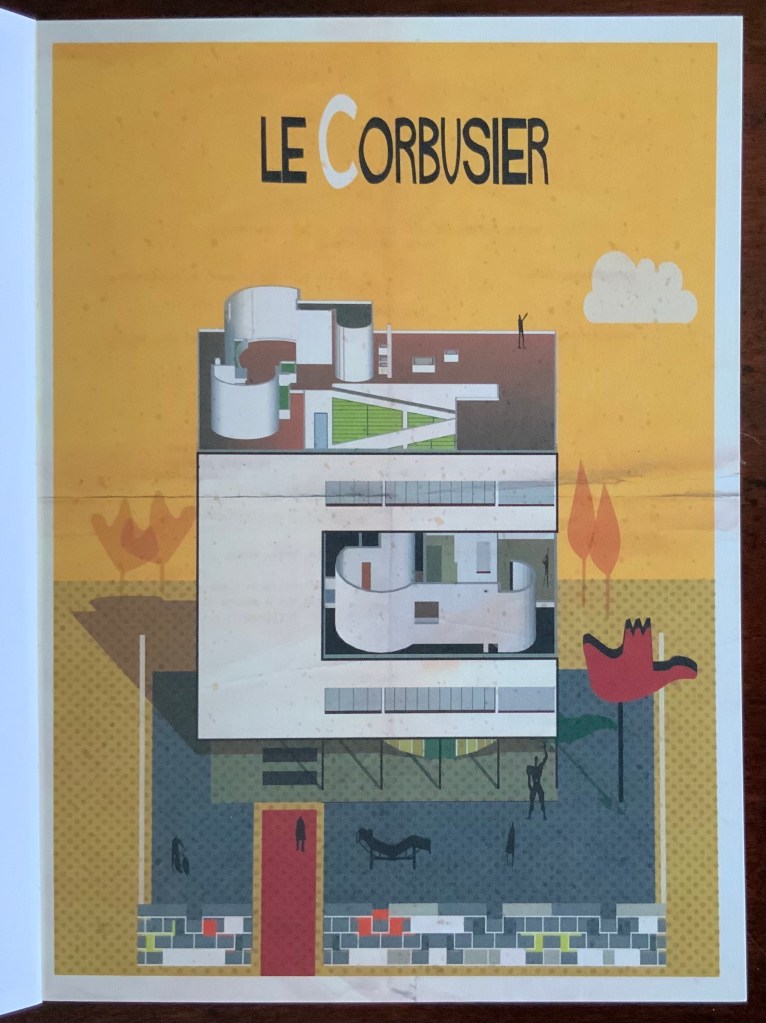

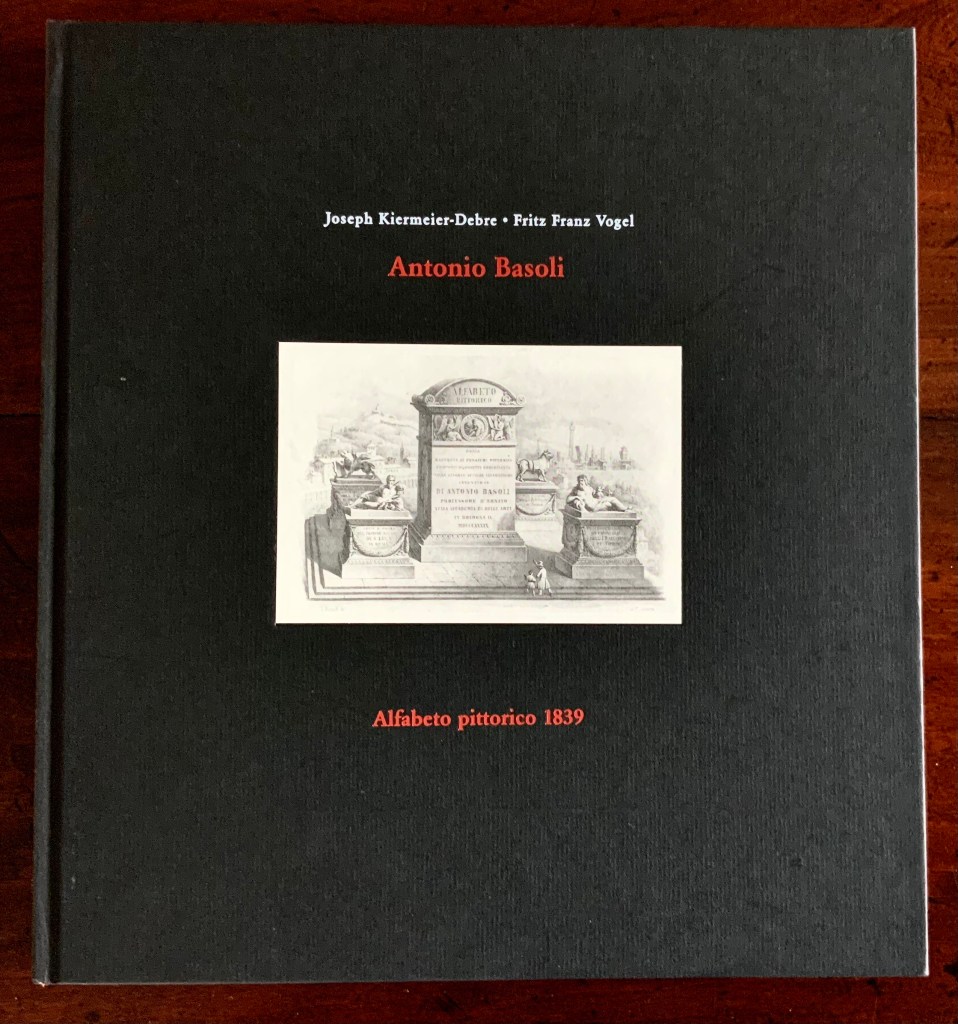

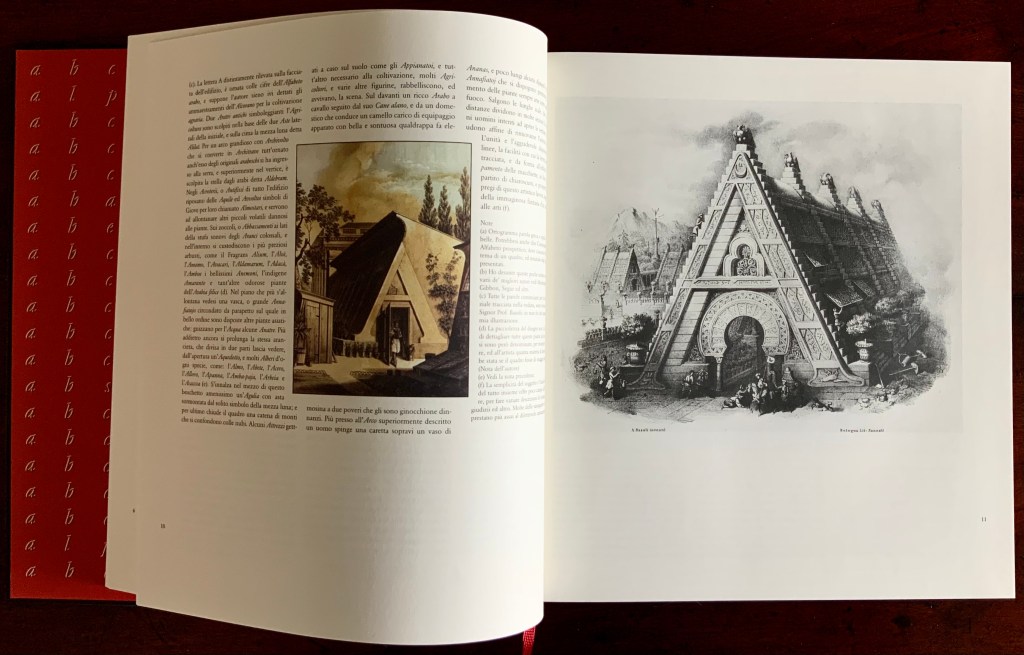

“Architecture“, Bookmarking Book Art, 12 November 2019.

Bachelard, Gaston, M. Jolas, and Etienne Gilson. 1964. The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press.

Chavasse, Paule. Interviewer. 1959. “Gaston Bachelard – Entretien : La poétique de l’espace.” Radiodiffusion Française (RDF). 1959. Accessed 8 February 2021.

Denis, Claire. 2016. Contact by Olafur Eliasson. Video. 8 March 2016. Accessed 7 February 2021.

Eliasson, Olafur. 2009. “Not how, but why!” in Concrete Design Book on Implicit Performance. Eds. Siebe Bake and Billy Nolan. Brussels: FEBELCEM.

Fondation Louis Vuitton. 2015. Contact – Olafur Eliasson. Video. 13 January 2015. Accessed 7 February 2021.

Jones, Caroline A. 2014. “Event Horizon: Olafur Eliasson’s Raumexperimente”, pp. 132-37, in Contact. Paris: Flammarion.

Marian Macken. 2018. Binding Space: The Book as Spatial Practice. London and New York: Routledge.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2016. “Matter, Hapticity and Time Material Imagination and the Voice of Matter.” Building Material, no. 20: 171-89. Accessed February 8, 2021.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2011. The embodied image: imagination and imagery in architecture. Chichester: J. Wiley & Sons.

Razzall, Katie. 2013. “Celebrating books… with pages made of glass“, Channel 4 News, 20 September 2013. Accessed 3 November 2020.