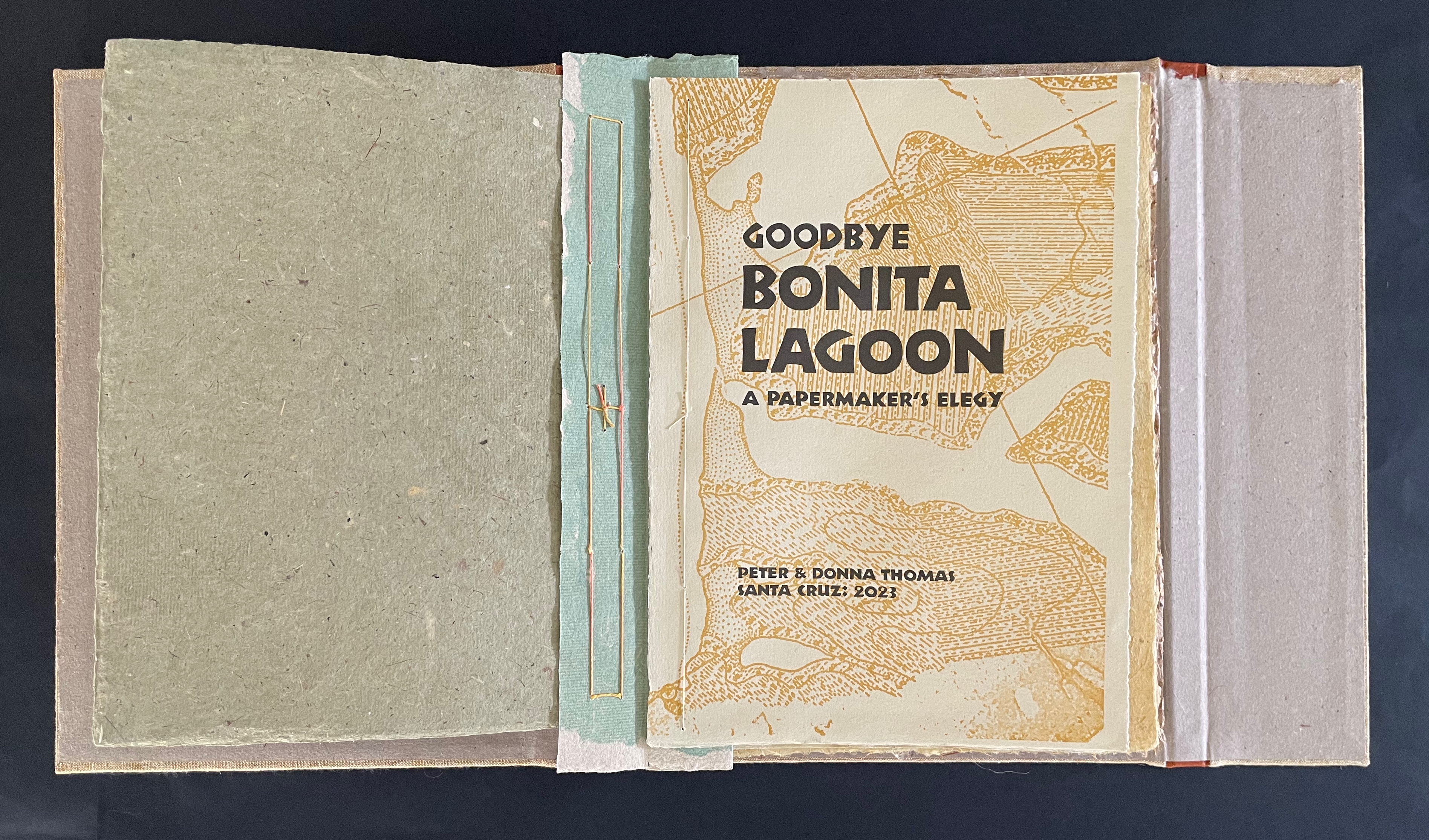

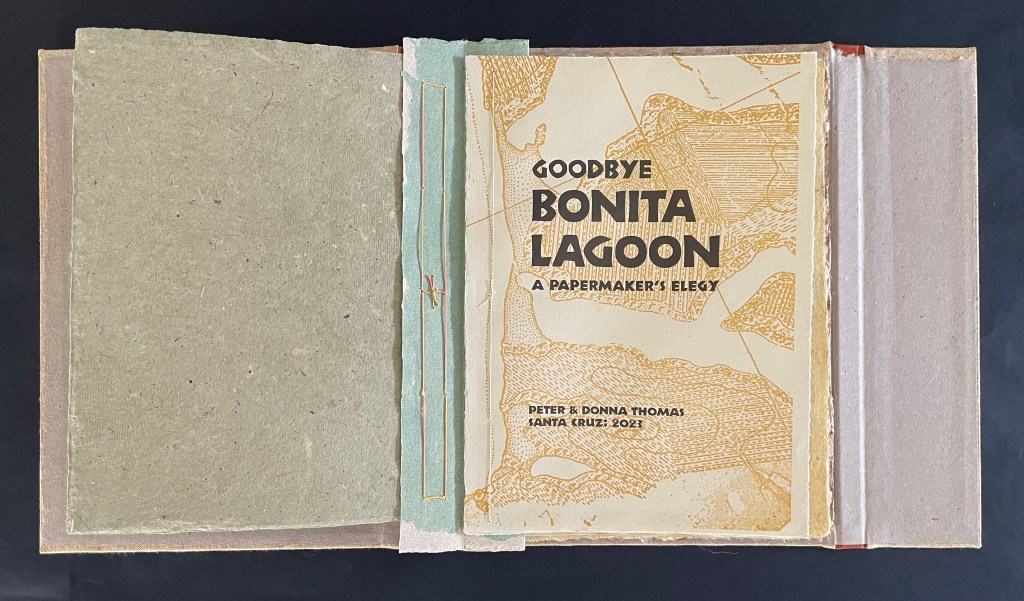

Goodbye Bonita Lagoon (2023)

Goodbye Bonita Lagoon: A Papermaker’s Elegy (2023)

Peter and Donna Thomas and Guy Van Cleave.

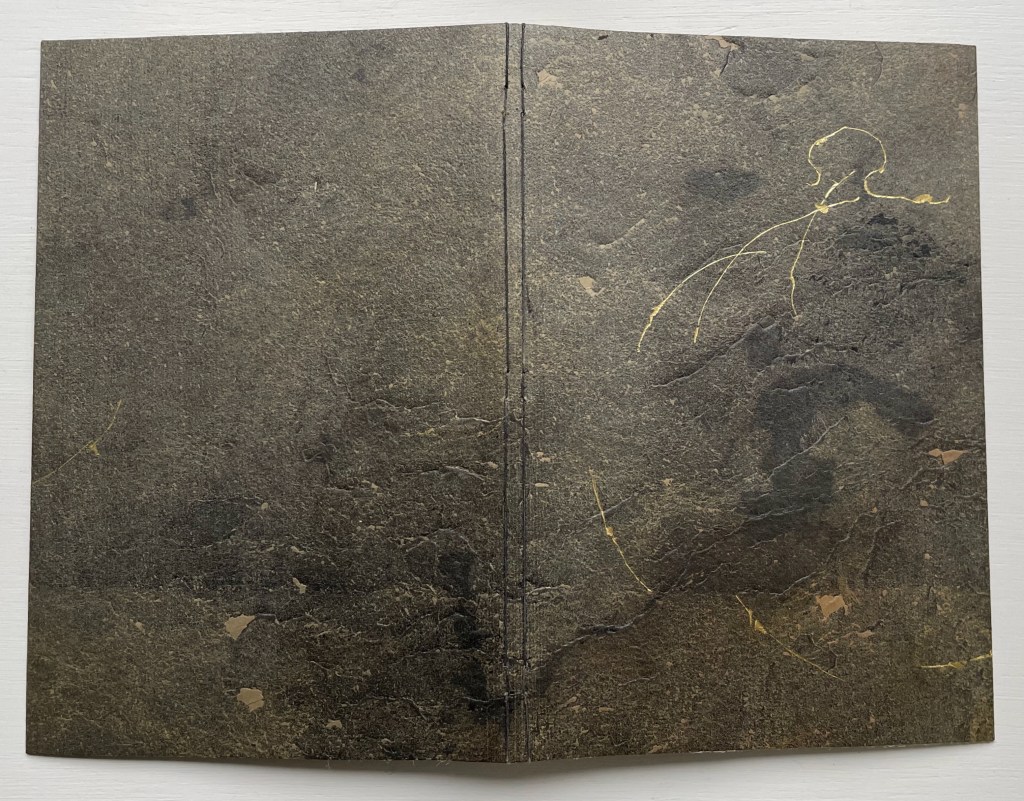

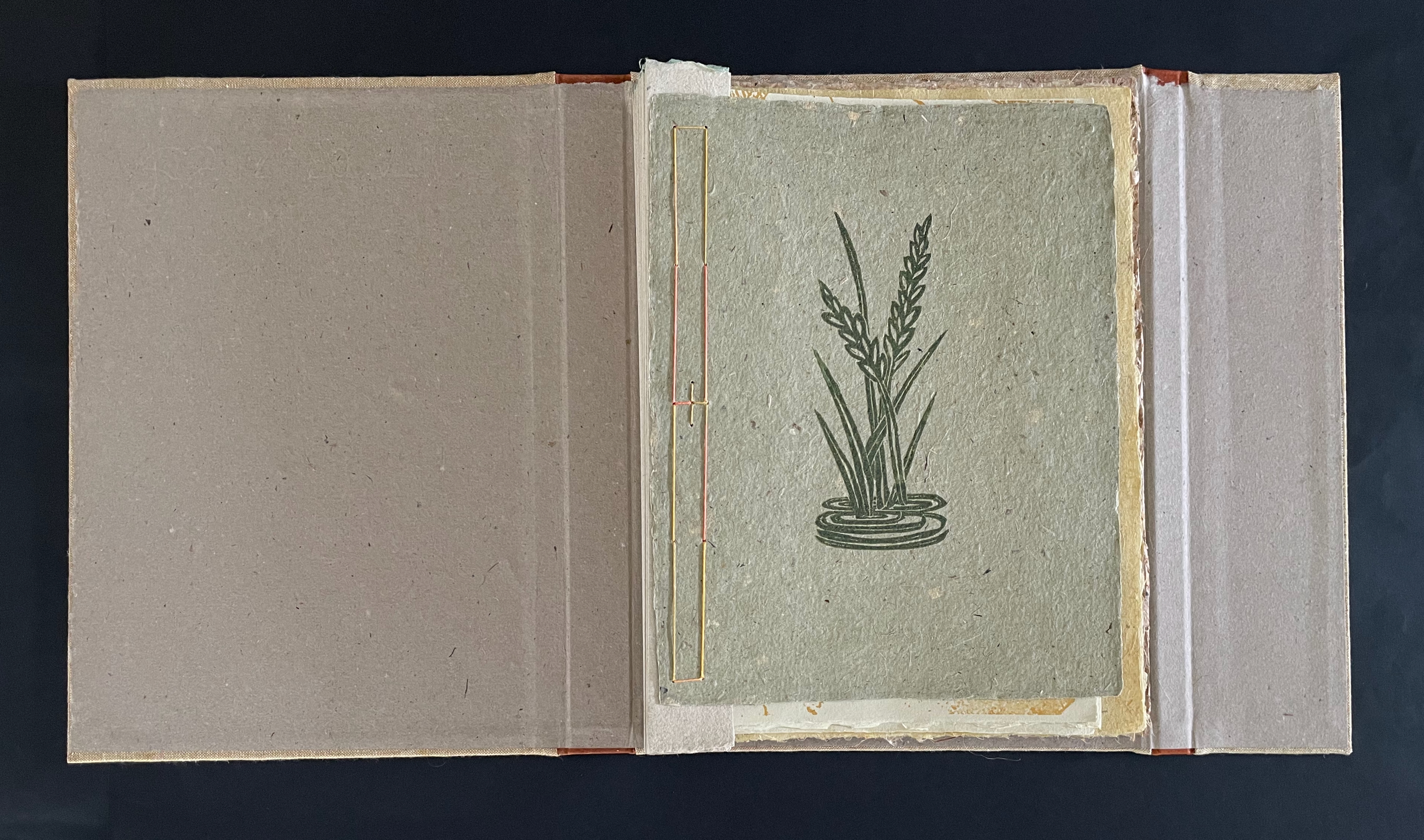

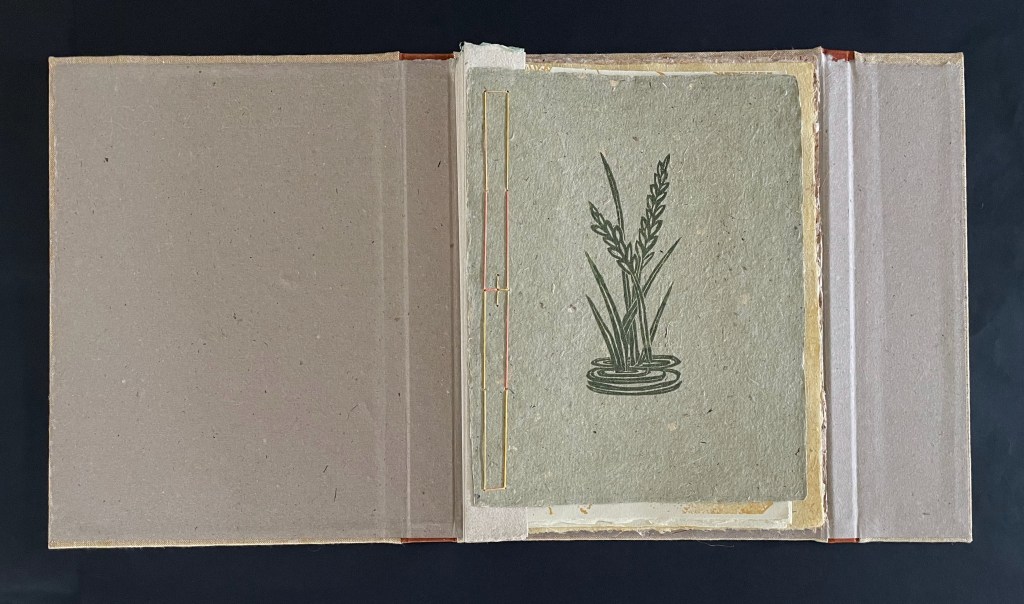

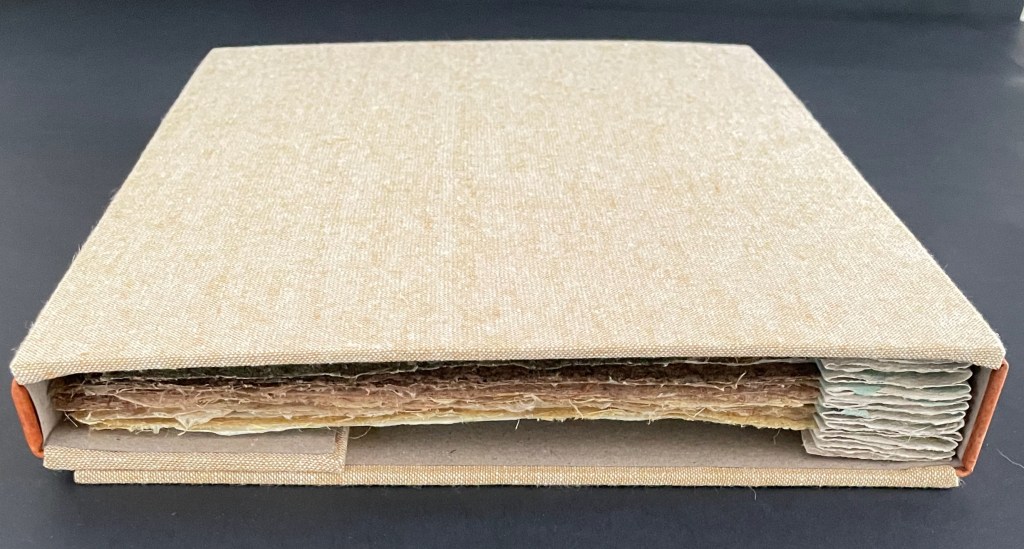

Tri-fold binding with 2 leather spines and sewn accordion binding structure, cloth over boards, light green linen cloth letterpress printed with three color linocut print on front cover, and title blind stamped on spine in brown foil. H300 x W225 mm. 80 pages. Edition of 30, of which this is #27. Acquired from the artists, 5 February 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

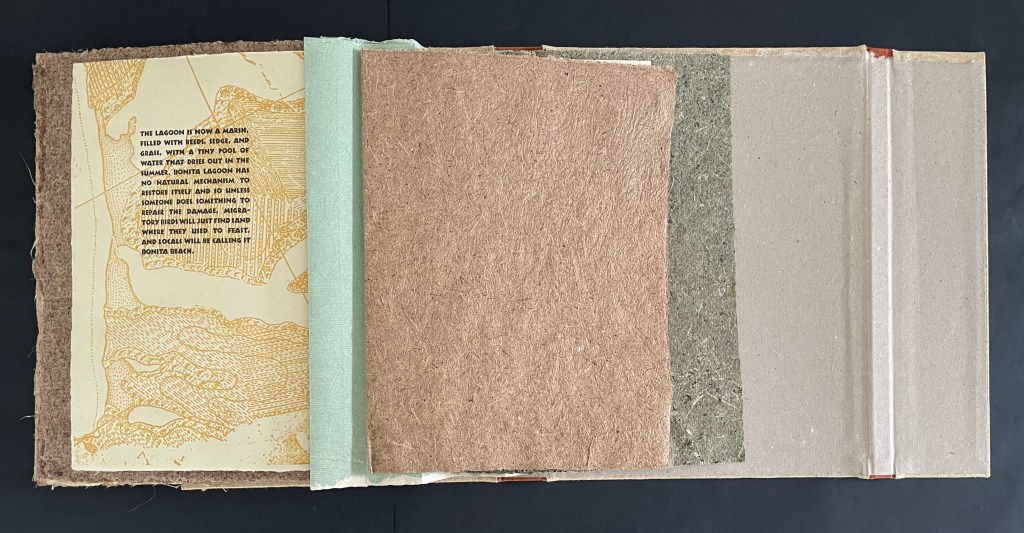

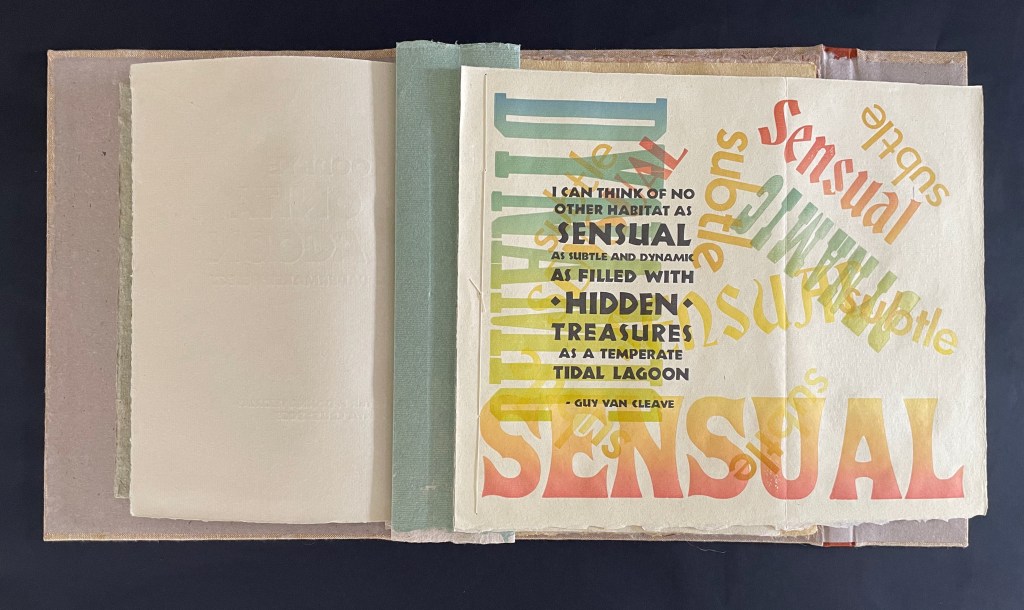

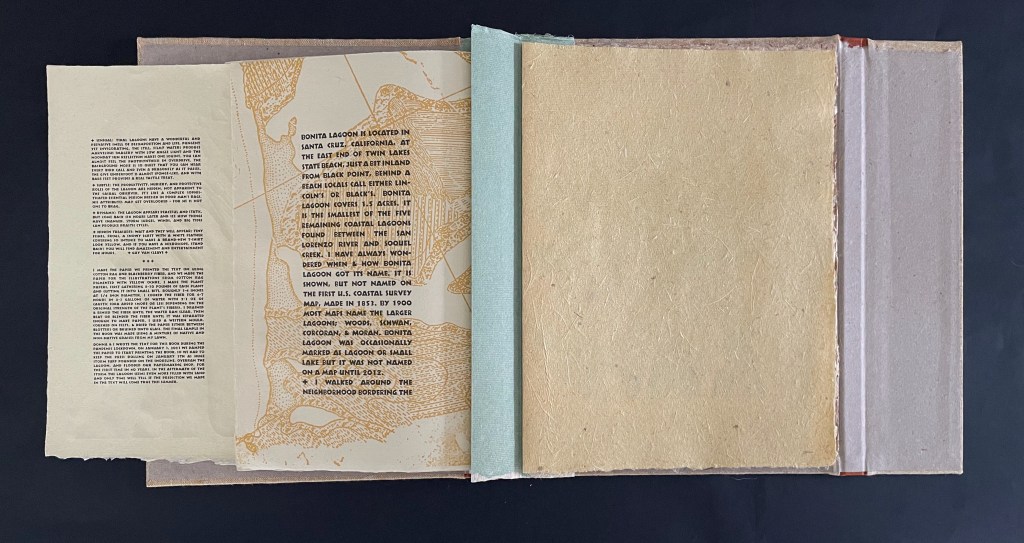

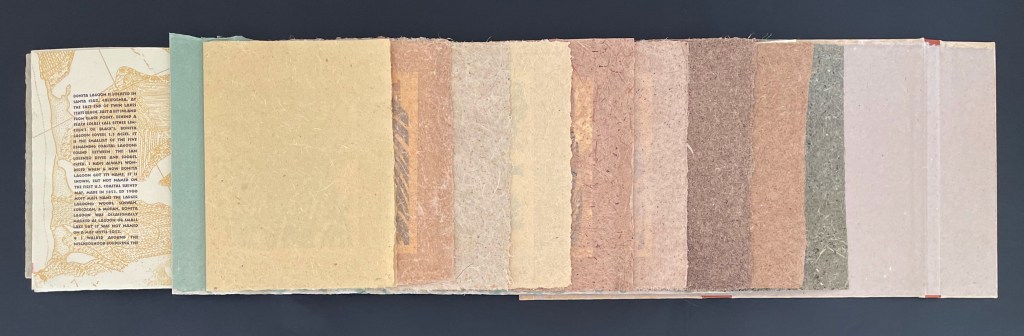

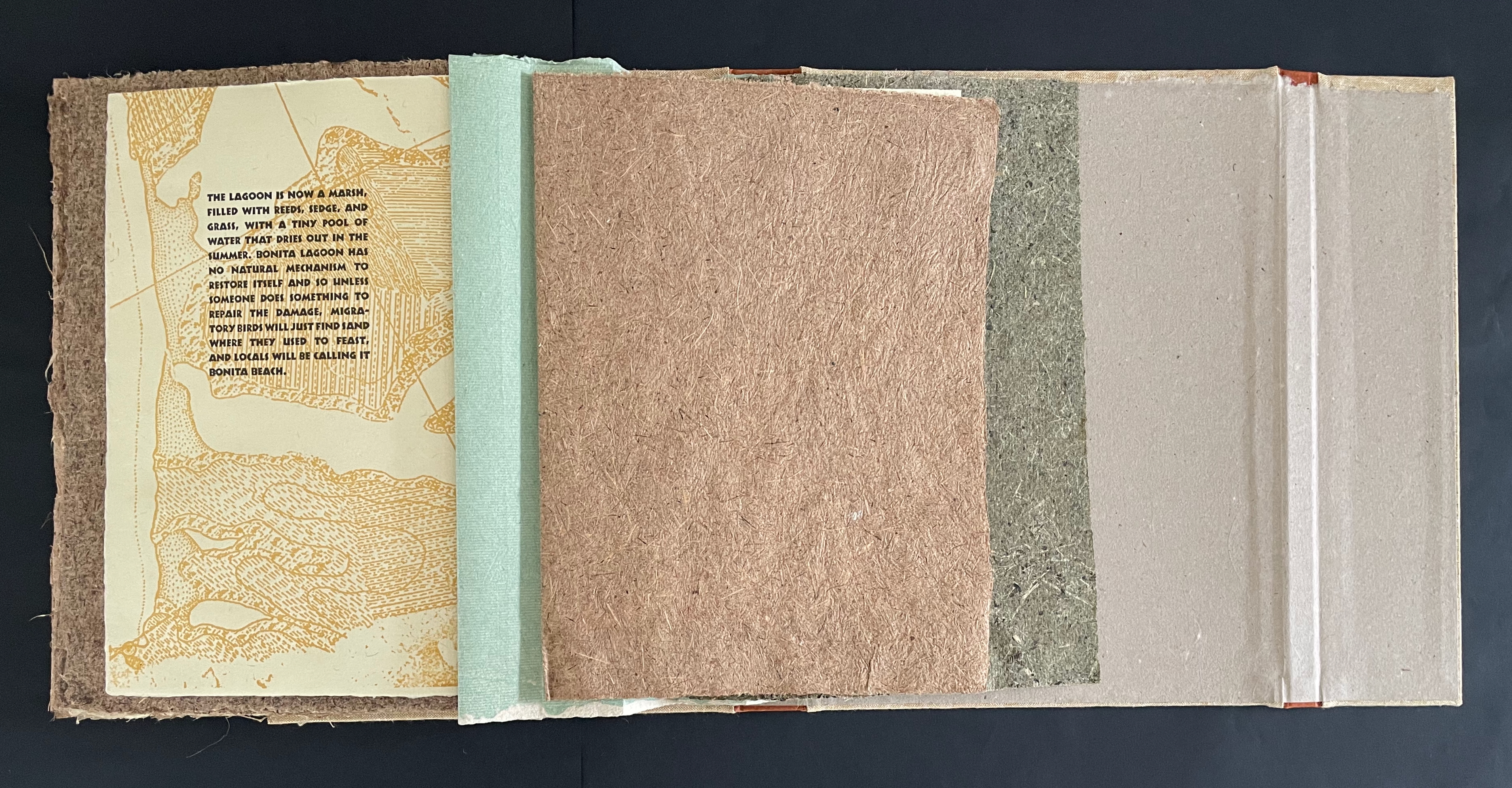

To read Goodbye Bonita Lagoon properly, you must read its text, its images, and its handmade papers as a whole. To do that, you need to let the binding structure guide you. The Thomases call the structure an accordion pleat spine stab-sewn book and have described and illustrated it in More Making Books by Hand (2004). Although the basics are the same –stab-sewing two single sheets of handmade paper and a single plant-paper folio to the recto or ascent side of each mountain fold in the accordion pleat spine — Goodbye Bonita Lagoon extends like a flag book, and as each gathering is turned to the left, the accordion pulls the left hand side of the book toward the right, tucking itself atop the previously turned sheets and folios. Below are the fully extended book, the extended book with the first five gatherings turned to the left, and the extended book with all the gatherings except the last turned. As the book progresses, the width of the extension narrows.

The photos below show the accordion pleat spine’s functioning end on.

Turning the next to last gathering (blackberry paper folio and single sheets) to show the spine’s function end on. Note how the right-hand edge of the light green accordion pleat is fixed to the inside back cover. As the gatherings turn to the left, the accumulated accordion has to move rightwards.

Like the extended width’s narrowing as the book comes to its close, Bonita Lagoon, too, has been collapsing. Elegiacally, each of the plant-paper folios is made from a plant gathered from the lagoon in the past. Inside each of the plant-paper folios, a single sheet insert carries a linocut of the plant and its name printed with wood type. On the back of each plant-paper folio, a single sheet insert bears text about Bonita Lagoon.

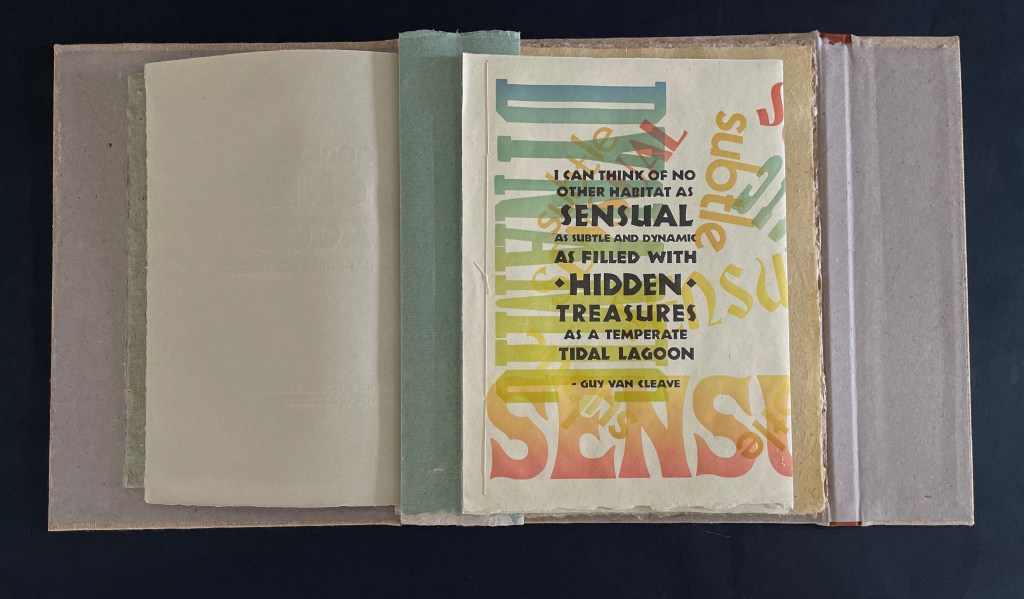

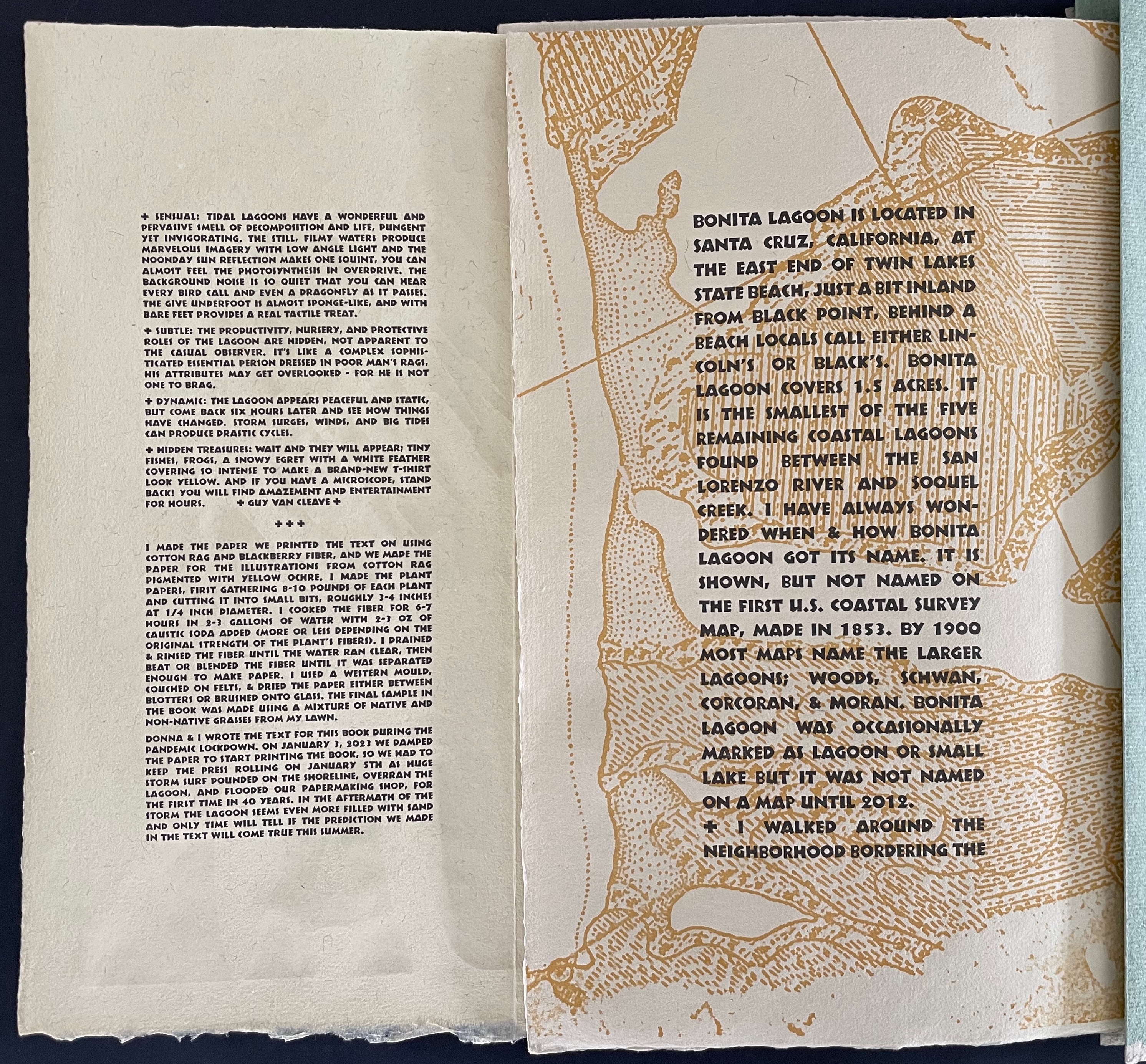

That descriptive text begins at the end of the book’s preliminary gathering, which opens with the book’s only multicolored text, a sort of epigraph from Guy Van Cleave (Professor of Biology, Glendale Community College), extolling the attractions of lagoons. Displayed on the book’s only foldout, the text continues on the reverse with more of Van Cleave’s observations but also a preview paragraph from Peter Thomas. The preview describes the sourcing and processing of the plant-paper folios and the circumstances in which the book was written. When you turn the foldout to read the text on its reverse side, the accordion spine also pulls into view this gathering’s final sheet presenting the book’s formal opening text.

Here’s the opening sequence without extending the book:

Left: The text on the reverse side of the extended foldout. Right: The preliminary gathering’s final sheet with the book’s formal opening text.

It feels a bit awkward to have the final bit of the prelim text hanging out as the book begins, so there’s the urge to tuck it away and take in the expanse of the plant-paper folios, while still carrying in the back of the mind a curiosity about the prediction that the prelim text teases.

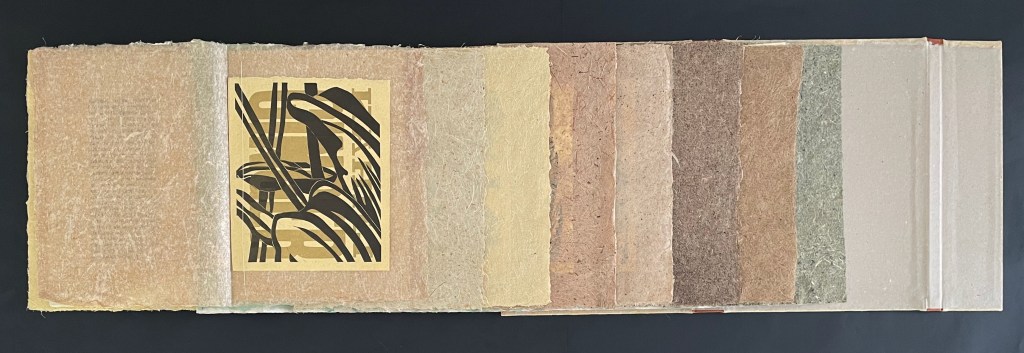

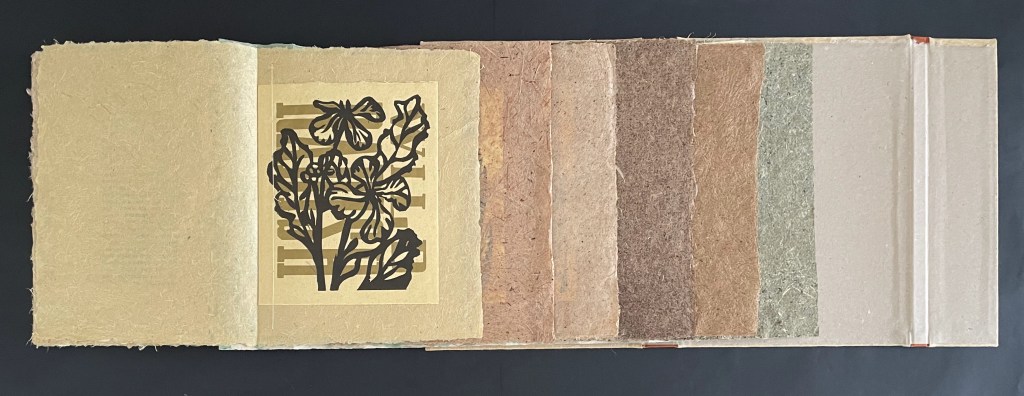

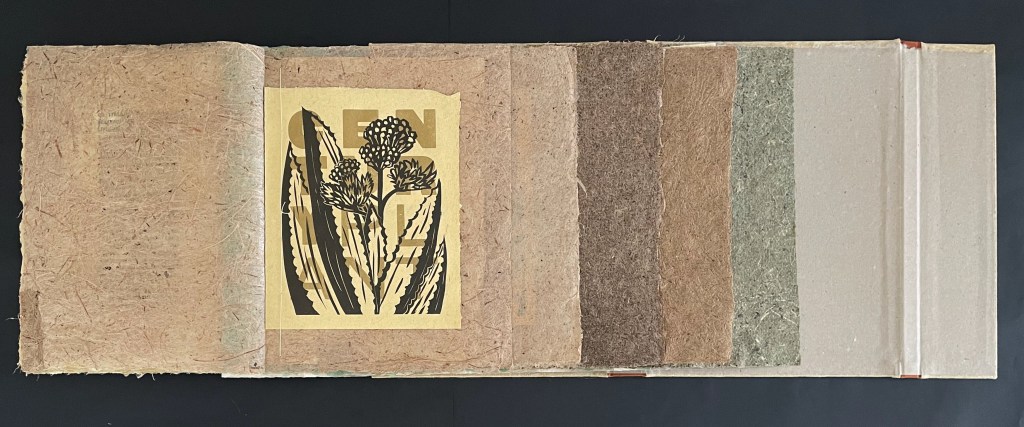

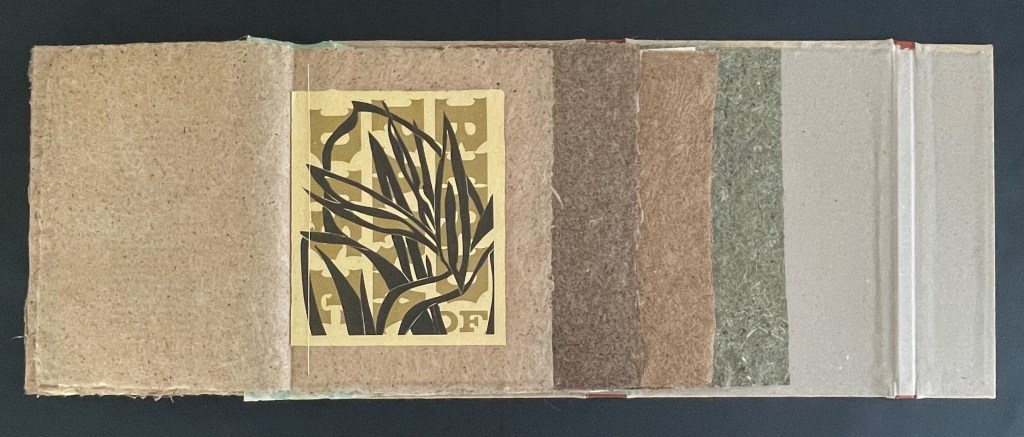

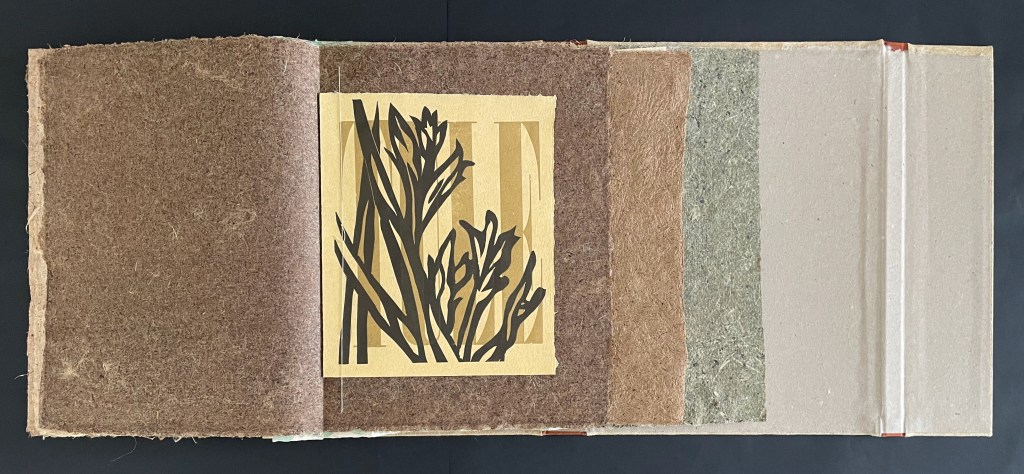

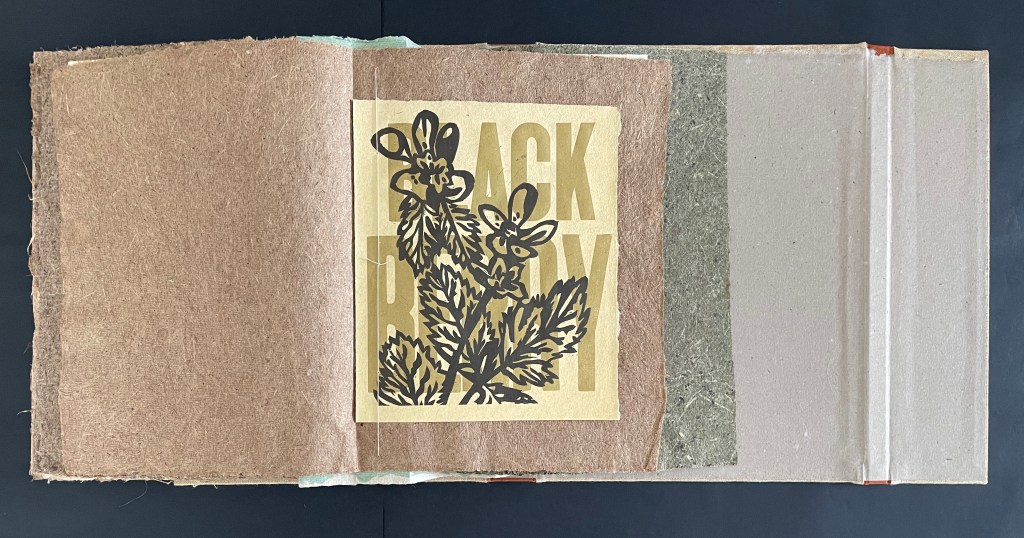

Donna Thomas’s linocuts printed over the names of the plants in wood type vary in orientation. Impressed on cotton rag paper handmade by Peter, they memorialize the plants harvested long ago and emphasize by contrast the texture of the plant-paper folios embracing them.

Folio of Pampas Grass paper with single sheet linocut by Donna Thomas over wood type.

Extended book open to folio of Kahili Ginger paper; single sheet linocut turned 90º.

Folio of New Zealand flax.

Folio of Wild Radish.

Folio of Century Plant.

Folio of Bird of Paradise.

Folio of Tule.

Folio of Blackberry.

The book’s formal elegy concludes on the Tule gathering’s end sheet. Here we find the prediction teased in the prelims. Due to construction along the coast, the lagoon has become a marsh and tiny pool that dries out in the summer. Without restoration, Bonita Lagoon is on its way to becoming Bonita Beach.

The prediction on the Tule gathering’s end sheet.

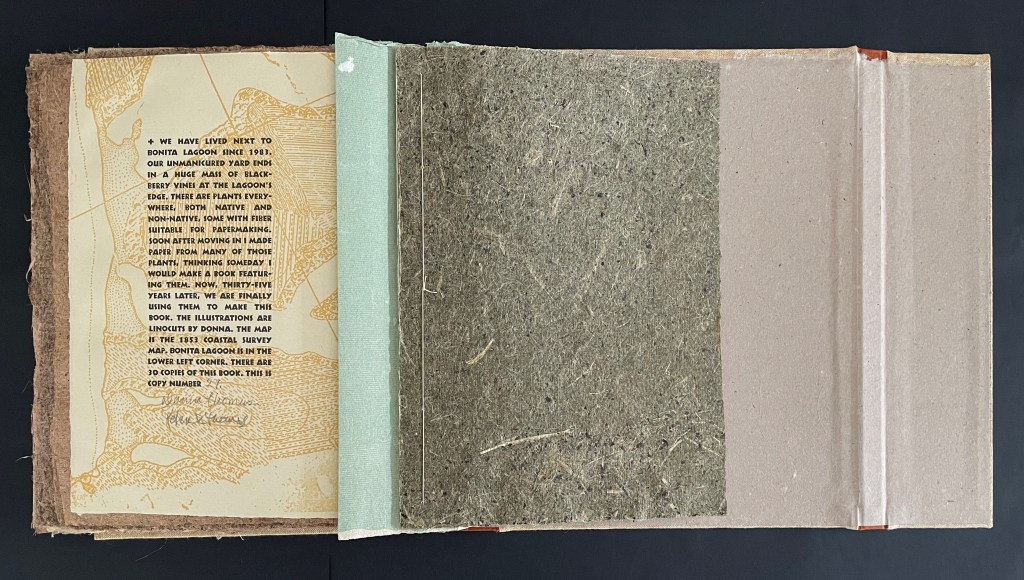

All along, the text set in Neuland has appeared over the print of a map. Not until after the prediction above and the turning of the Blackberry gathering is it revealed in the colophon that the map is from the 1853 coastal survey mentioned at the beginning. With a sort of unwritten coda, the book ends with a single sheet made from clippings from the Thomases’ otherwise unmanicured lawn next to Bonita Lagoon.

Colophon.

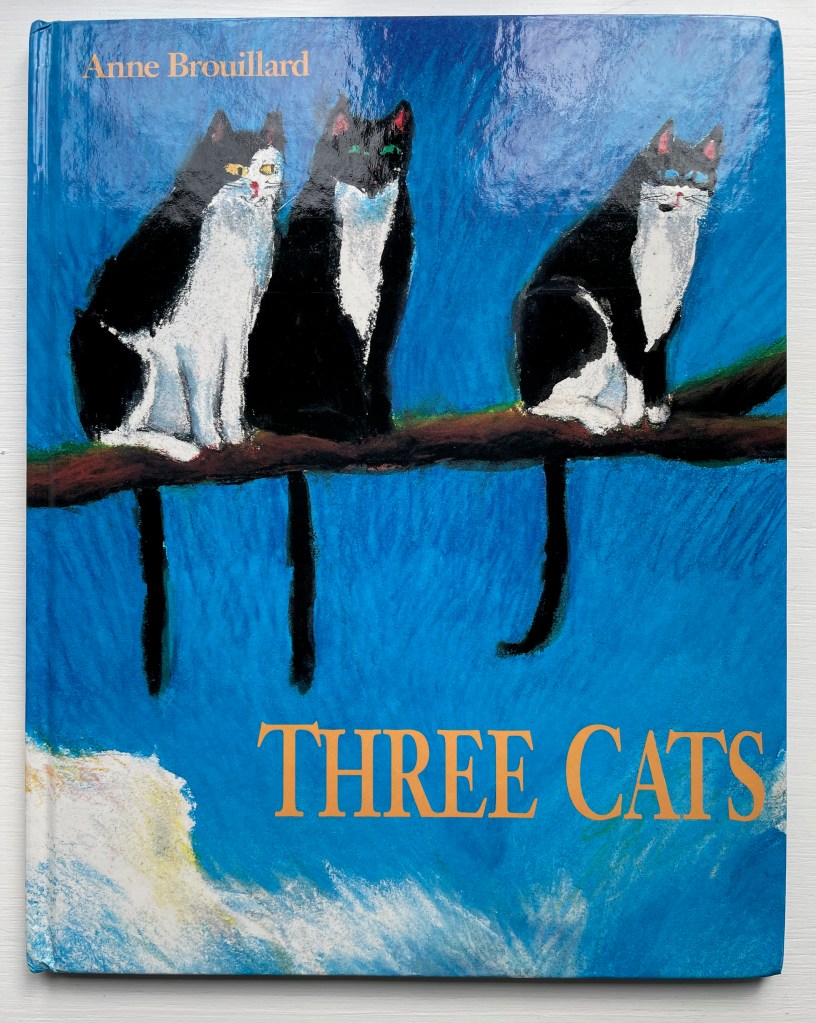

1,000 Artists’ Books (2012)

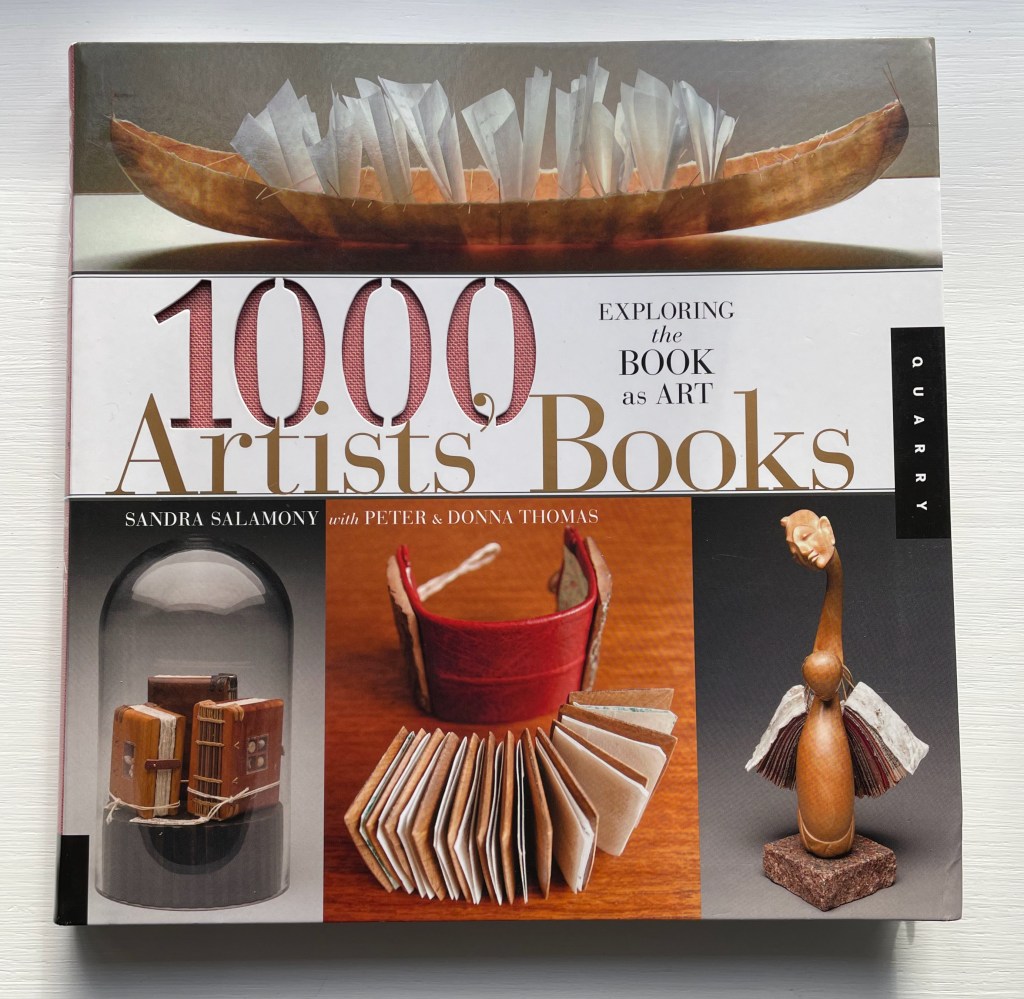

1,000 Artists’ Books: Exploring the Book as Art (2012)

Sandra Salamony and Peter & Donna Thomas

Softcover, casebound in illustrated paper over flexible card, patterned doublures, headbands. H235 x W235 mm. 320 pages. Acquired from Brendan McSherry, 20 October 2023.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Besides their prolific artistic output, much of which (up to 2005) can be viewed in the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries Special Collections, the Thomases have also published several instructional and reference works on papermaking and the book as an art form. This one with Sandra Salomony covers various aspects of hand-crafted books: covers, bindings, scrolls, folded and origami structures, books made from found objects, altered books, and book installations, as well as books created from a variety of printing processes. Its taxonomy is useful when exploring new works and examining collections.

Further Reading

“Amanda Degener“. In process. Books On Books Collection.

“The First Seven Books of the Rijswijk Paper Biennial“. 10 October 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Taller Leñateros“. 19 November 2020. Books on Books Collection.

“Timothy Mosely“. 23 August 2024. Books on Books Collection.

“Maureen Richardson“. 28 September 2019. Books on Books Collection.

“Fred Siegenthaler“. 10 January 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Peter & Donna Thomas (I)“. 20 May 2023. Books On Books Collection.

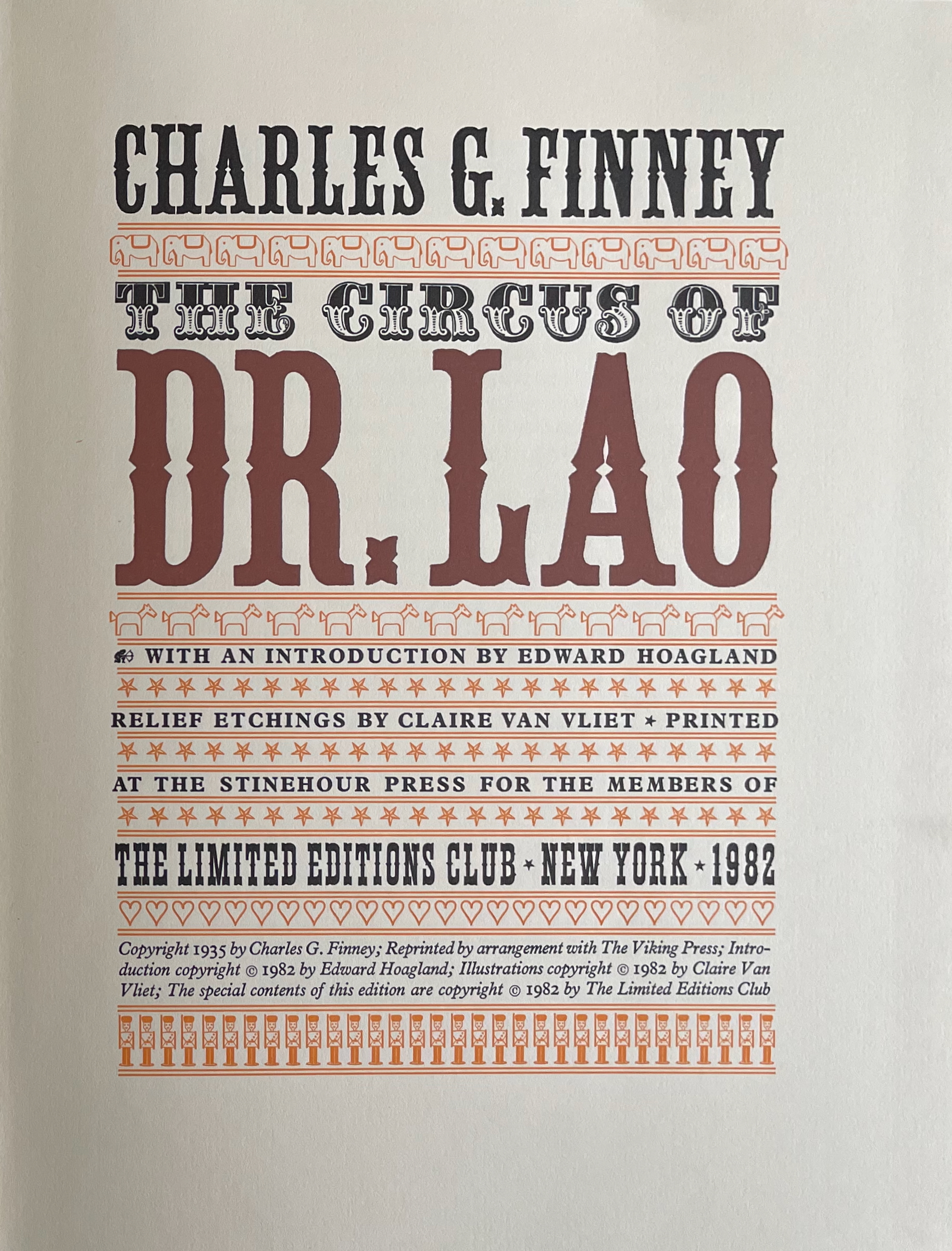

“Claire Van Vliet (II)“. 28 May 2025. Books on Books Collection.

“Hedi Kyle’s The Art of the Fold: How to Make Innovative Books and Paper Structures (2018)“. 24 September 2018. Bookmarking Book Art.

Blum, André, and Harry Miller Lydenberg. 1934. On the origin of paper. New York: R.R. Bowker Company.

Chen, Julie. 2013. 500 Handmade Books. Volume 2. New York: Lark. Pp. 87 (Not Paper), 258 (The Alder).

Hamady, Walter; Samuel Haatoum; and Hermann Zapf. 1982. Papermaking by Hand : A Book of Suspicions. Perry Township, Dane County, Wisconsin, USA: Perishable Press Limited.

Hiebert, Helen. 2000. The papermaker’s companion: the ultimate guide to making and using handmade paper. North Adams, MA: Storey Pub.

Hunter, Dard. 1987. Papermaking: the history and technique of an ancient craft. New York: Dover.

Jury, David, and Peter Rutledge Koch (eds.) 2013. Book Art Object 2 : Second Catalogue of the Codex Foundation Biennial International Book Exhibition and Symposium, Berkeley, 2011. Berkeley, CA; Stanford, CA: Codex Foundation; Stanford University Libraries. Pp. 409 (Yellowstone), 410 (The History of the Accordion Book).

Jury, David, and Peter Rutledge Koch (eds.) 2008. Book Art Object. Edited by David Jury. Berkeley, California: Codex Foundation. Pp. 323 (Believe in the Beauty), 324 (The History of Papermaking in the Philippines), 325 (An Excerpt from John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row).

Kurlansky, Mark. 2016. Paper: paging through history. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

Miller, Steve. 2008. 500 Handmade Books : Inspiring Interpretations of a Timeless Form. Edited by Suzanne J. E. Tourtillott. New York: Lark Crafts. Pp. 77 (Paper from Plants), 225 (Ukulele Series Book #4 The Ukulele Bookshelf), 254 (Ukulele Series Book #9, The Letterpress Ukulele), 291 (Y2K3MS: Ukulele Series Book #2, Ukulele Accordion).

Müller, Lothar. 2015. White magic: the age of paper. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Richardson, Maureen. 1999. Grow your own paper : recipes for creating unique handmade papers . N.P.: Diane Pub Co.

Salamony, Sandra, and Peter and Donna Thomas. 2012. 1,000 Artists’ Books : Exploring the Book as Art. Minneapolis: Quarto Publishing Group USA. Pp. 26 (Ukelele Series Book #14 Old Ukes), 31 (The Pencil), 187 (The Real Accordion Book), 201 (The Mystical Quality of Handiwork), 205 (California Dreaming).

Sansom, Ian. 2012. Paper: an elegy. New York, NY: Wm. Morrow.

Thomas, Peter, and Donna Thomas. 2004. More Making Books by Hand : Exploring Miniature Books, Alternative Structures, and Found Objects. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Quarry Books.

Thomas, Peter, and Donna Thomas. 1999. Paper from Plants. Santa Cruz, Calif: Verf. You can find images of this and others by the artists online in the Special Collections website of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

Weber, Therese. 2008. The language of paper: a history of 2000 years. Bangkok, Thailand: Orchid Press.