What is it about artists’ books and architecture that they intersect so often? Architectural interiors and exteriors, ideas, themes, styles, landmark dwellings and edifices have found their metaphorical expression and embodiment in book art with such regularity that they make up a genre within the genre. Perhaps it is that, as Victor Hugo expresses it in Nôtre Dame de Paris (1831/1902),

… the human race has two books, two registers, two testaments: masonry and printing; the Bible of stone and the Bible of paper. … The past must be reread upon these pages of marble. This book, written by architecture, must be admired and perused incessantly; but the grandeur of the edifice which printing erects in its turn must not be denied. (Book V, Chapter 2, p. 187)

Or perhaps it is even more fundamental. As Hugo asserts in his posthumous The Alps and the Pyrenees (1890/1895):

All letters were signs at first, and all signs were images at first…. Human society, the world, man as a whole, is in the alphabet…. A is the roof, the gable with its cross-beam, the arch, arx; … Z is the lightning, it is God. (pp. 64-65)

Beneath the mysticism and pareidolia, Hugo is on to something. Maybe the affinity of books and architecture lies in the origin of the raw material of books — the alphabet — whose second letter comes from a mark signifying shelter or house.

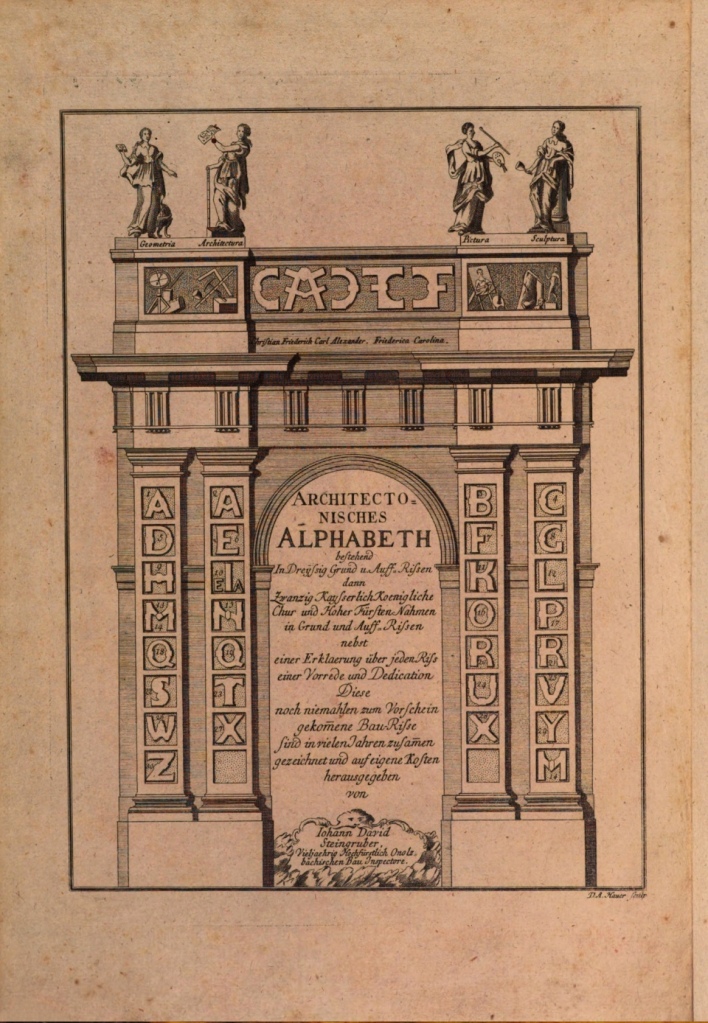

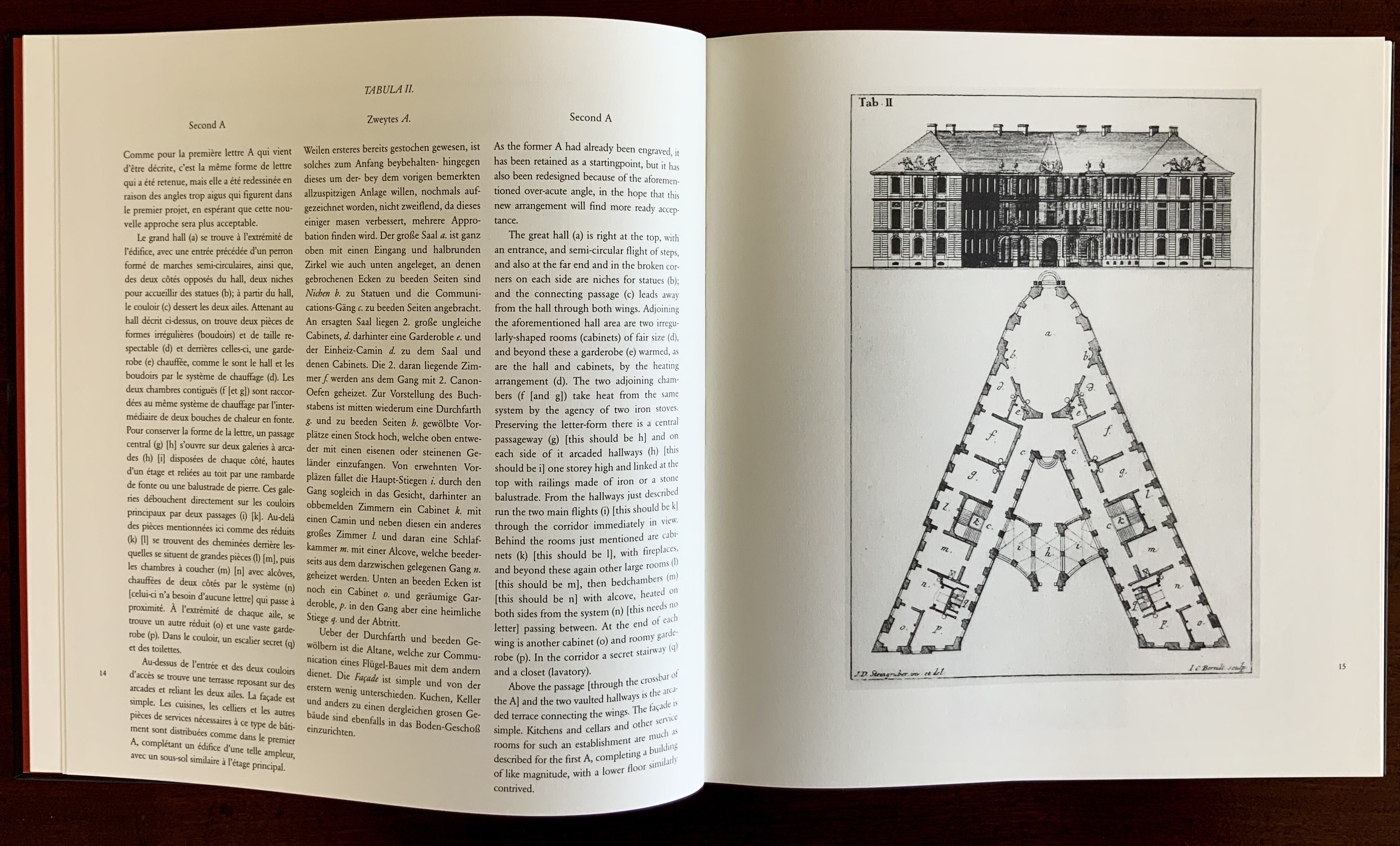

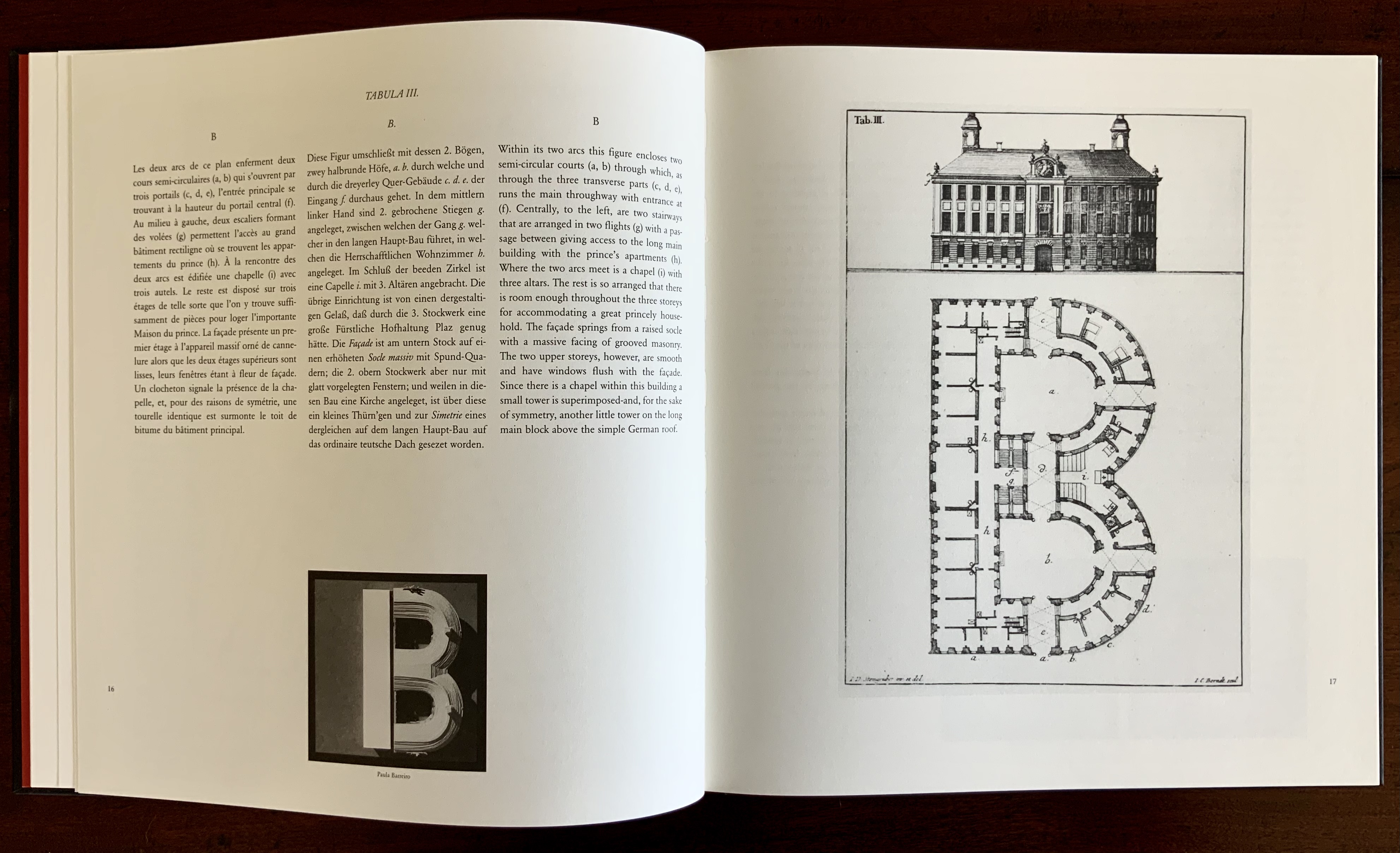

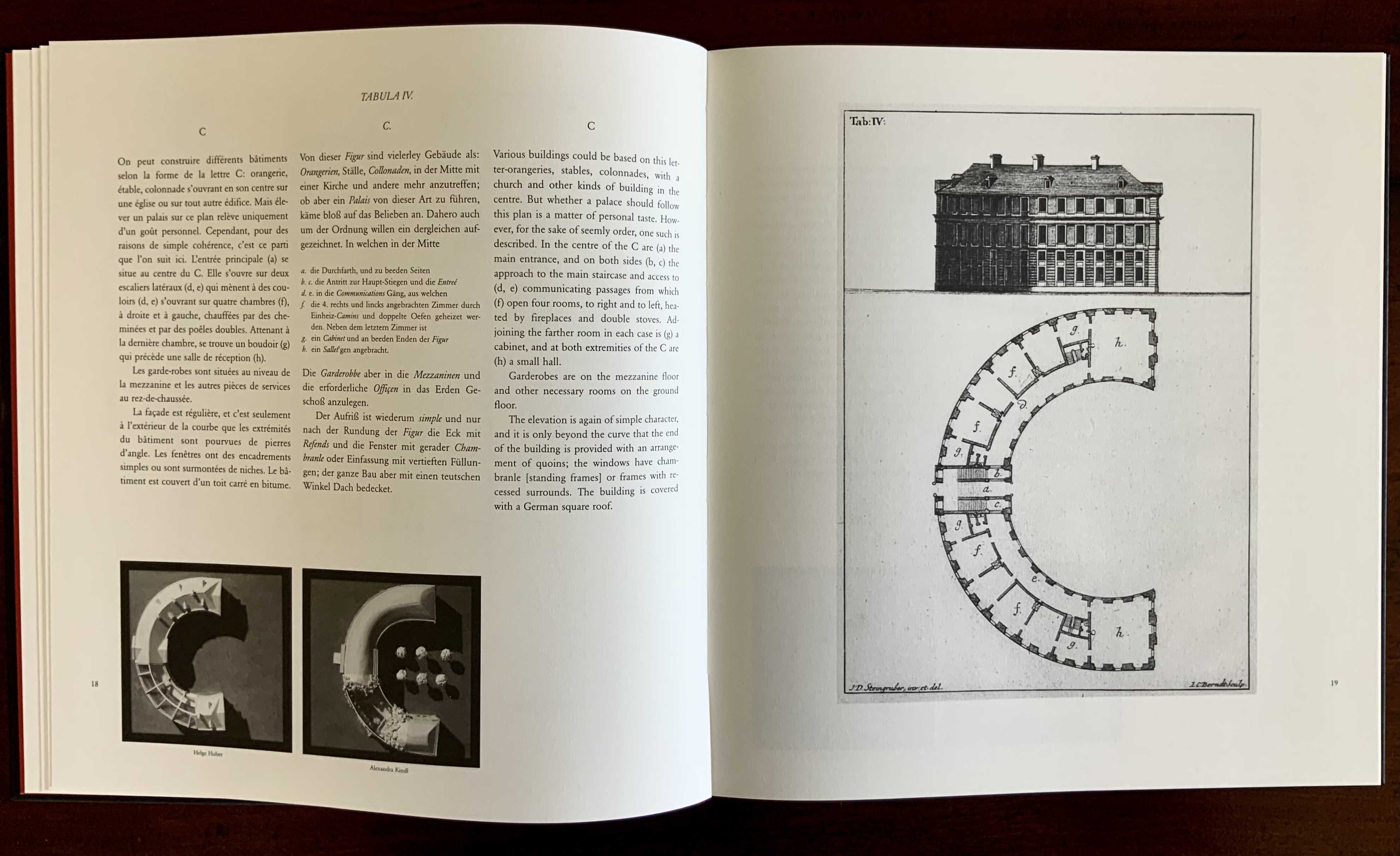

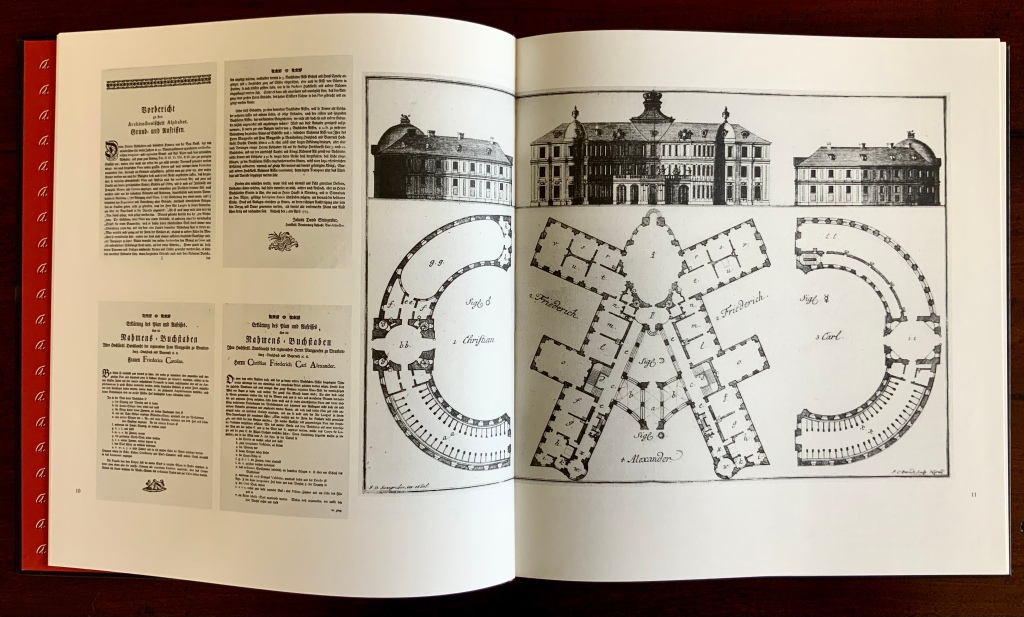

This wondering and wandering about the intersection of architecture and the artist’s book is prompted by the 250th anniversary of the publication of Johann David Steingruber’s Architectonisches Alphabeth(1773). This postcard-famous volume of print folios depicts architectural elevations and plans for residences in the shape of the letters of the alphabet. It is dedicated to Christian Friedrich Carl Alexander, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, not to be confused with the paying dedicatee of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, the Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt. By a baroque coincidence, however, the first Brandenburg concertos, the ones composed by Giuseppe Torelli and influencing Bach, are dedicated to the Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, then George Friedrich II, Alexander’s great-uncle who employed Torelli as court composer. Unlike Bach, however, Torelli received no direct payment for his composition. Steingruber too had to be satisfied with his payment as an appointee (court and public surveyor, and later principal architect of the board of works).

Steingruber may have felt he had good reason to be miffed. After all he had published the volume in installments at his own expense and made sure that the Margrave’s monogram (and that of Carolina Frederica, his wife) in building form appeared in the span above the roman arch on the title page. His elevations and plans draw attention to the heating, kitchen, toilet and servants’ arrangements as if conferring with a prospective client ready to commission one of these typographic palaces. Perhaps he was thinking, Who would not want a serif with a view? Or conduct guests on a tour of the bowl, capline, crossbar, stem, stroke and tail of the property? In a flourish that illustrates the intersection of book and architecture, the title page presents the title and subtitle inside an arch and serves double duty as a Table of Contents with thumbnail images of the letter-shaped buildings to come inscribed on the columns.

Munich, Bavarian State Library

To celebrate the Architectural Alphabet‘s 250th anniversary, this online essay/exhibition explores sixteen propositions about the affinity of architecture and artists’ books. Examples supporting each proposition include works from within and without the Books On Books Collection, and each example includes a link or links for additional views of the work. Every effort has been made to provide bibliographical (or webliographical?) links from WorldCat and the Internet Archive. The former will allow the reader to find local libraries that hold a copy of the exhibited work to be viewed in person; the latter will partly address the problem of broken links. Where broken links (or factual errors) do appear, readers are encouraged to alert the curator in the Comments section at the end of the essay/exhibition.

Proposition #1: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in the alphabet.

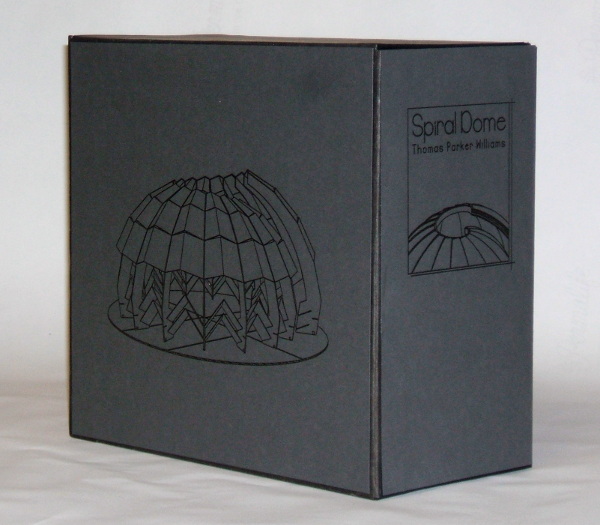

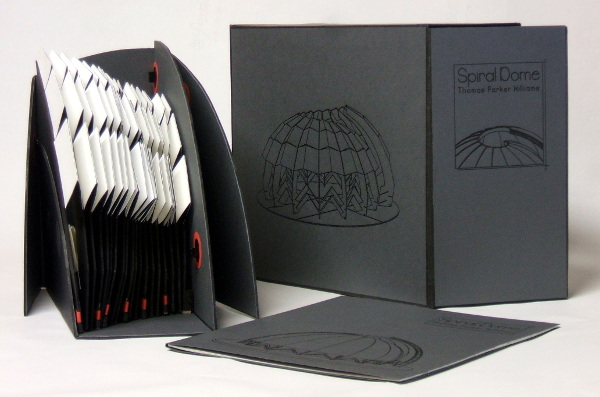

Architectural alphabet (1773/1972)

Johann David Steingruber

Published by Merrion Press.

Architectonisches Alphabeth (1773/1995)

Prepared by Joseph Kiermeier-Debre and Fritz Franz Vogel for Ravensburger Verlag.

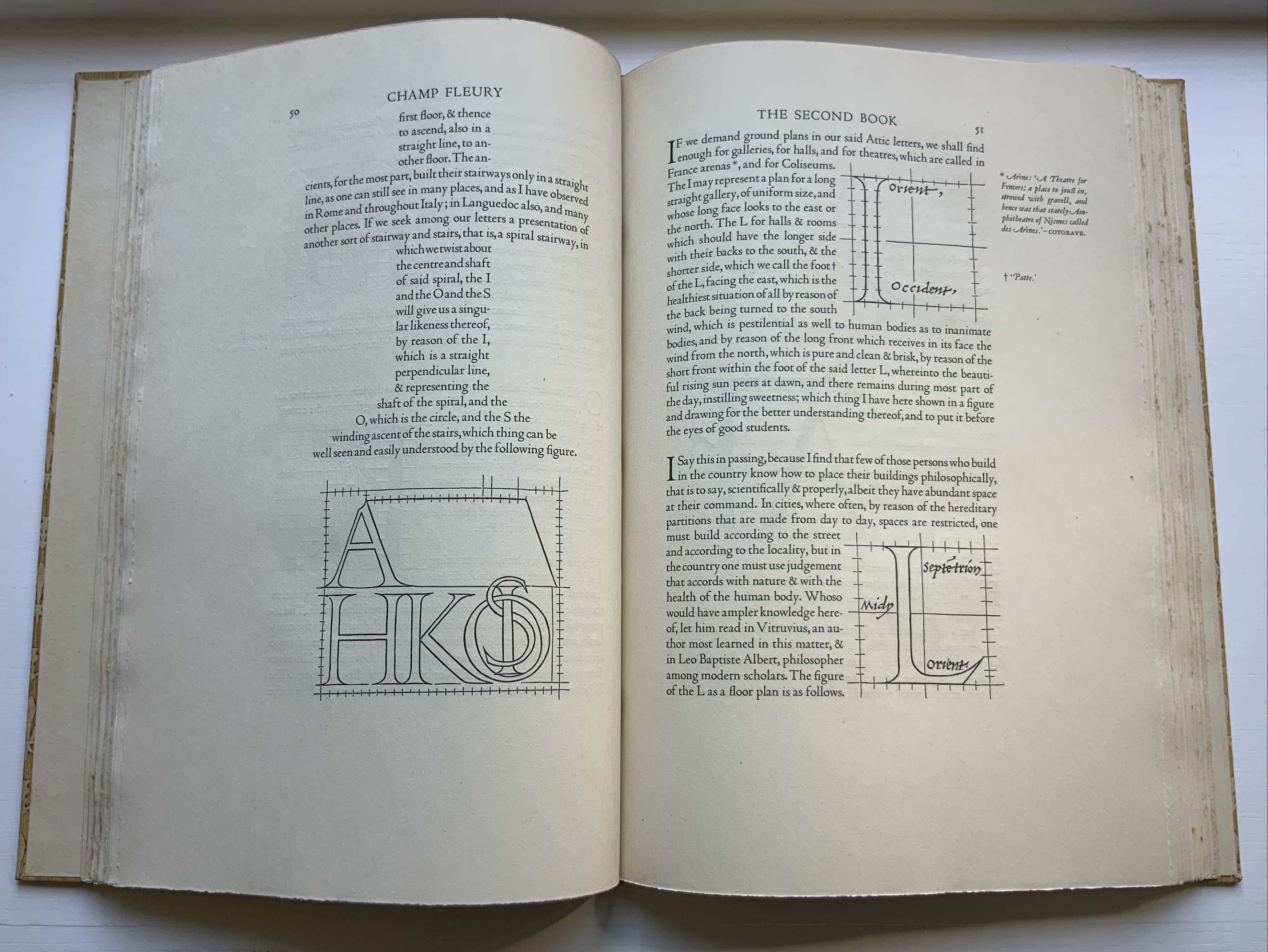

Of course the first exhibit would be Steingruber’s Architectural Alphabet, but related works — before and after, published or built — will clamor for admission: Geofroy Tory’s Champ Fleury (1529/1927/1998), Antonio Basoli’s Alfabeto Pittorico (1839/1998), Giovanni Battista de Pian’s Alphabetto Pittoresque (1842), and Daniel Libeskind’s Contemporary Jewish Museum (2000), whose form within the walls of a former power substation is composed of two Hebrew letters — the Yud and the Chet — which make up the word Chai (“Life”).

Left to right: Tory/Rogers, Basoli, Battista de Pian (Photos by Books On Books Collection), Libeskind (The Yud Gallery, Photo by Paul Dyer).

Lanore Cady’s Houses & Letters (1977) is another work supporting the proposition, in this case with calligraphy, watercolor and verse.

Houses & Letters: A Heritage in Architecture & Calligraphy (1977)

Lanore Cady

More than the novel inventions and historical associations above, though, the space within and around a letter, a building and the artist’s book suggests the real root of the affinity. As cultural historian Fiona MacCarthy put it: “‘the Italians knew by instinct what we are slowly grasping, that the meaning of the city is not so much a matter of the buildings as the spaces in between.’” To which John Ryder added: “‘This is exactly how typography works.’” (From David Esslemont’s Inside the Book, 2002). And it is exactly how book art works.

Proposition #2: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in telling stories.

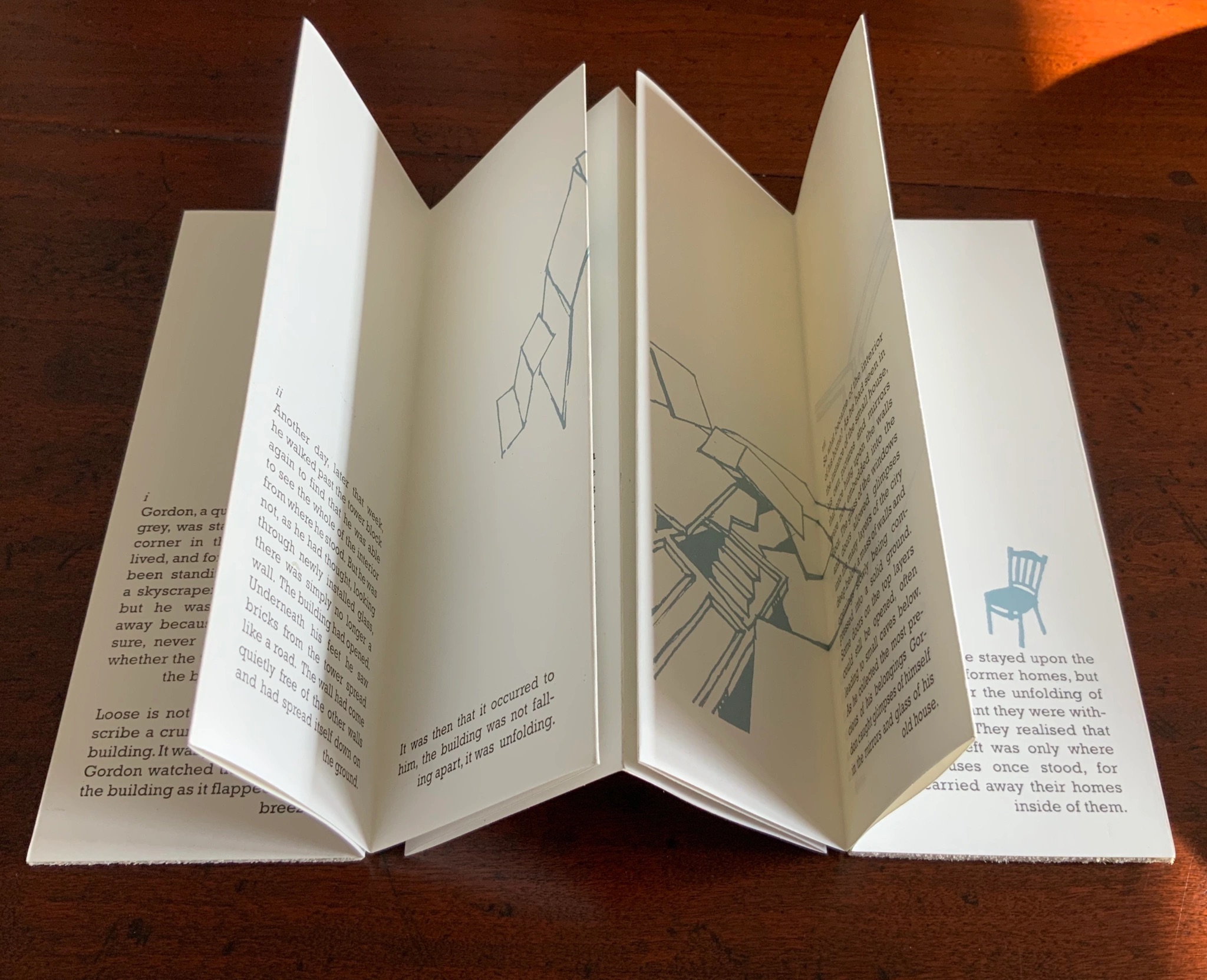

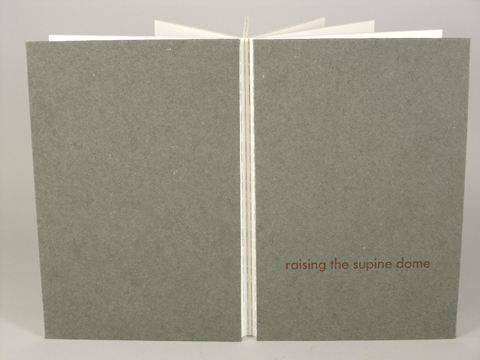

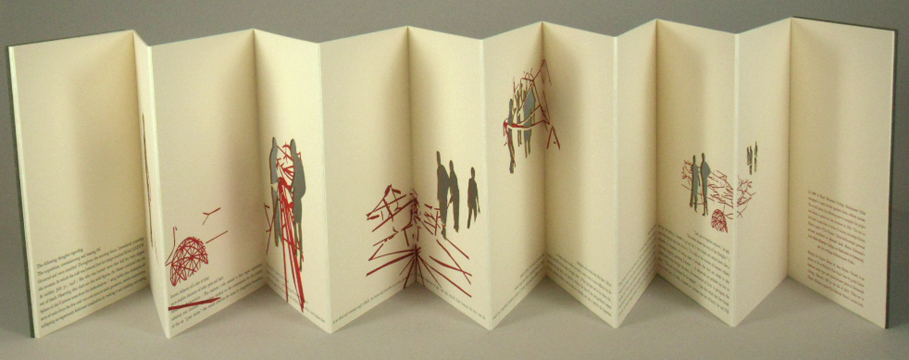

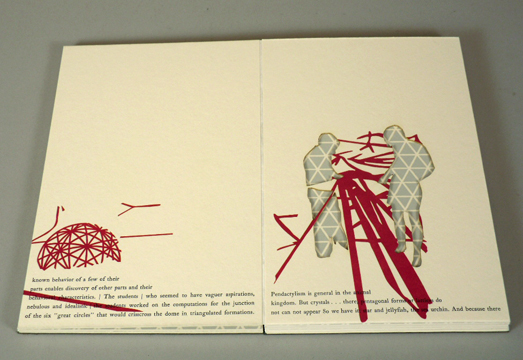

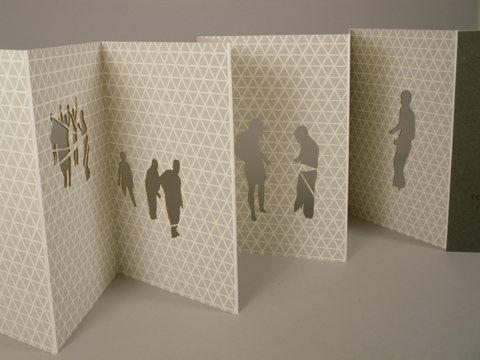

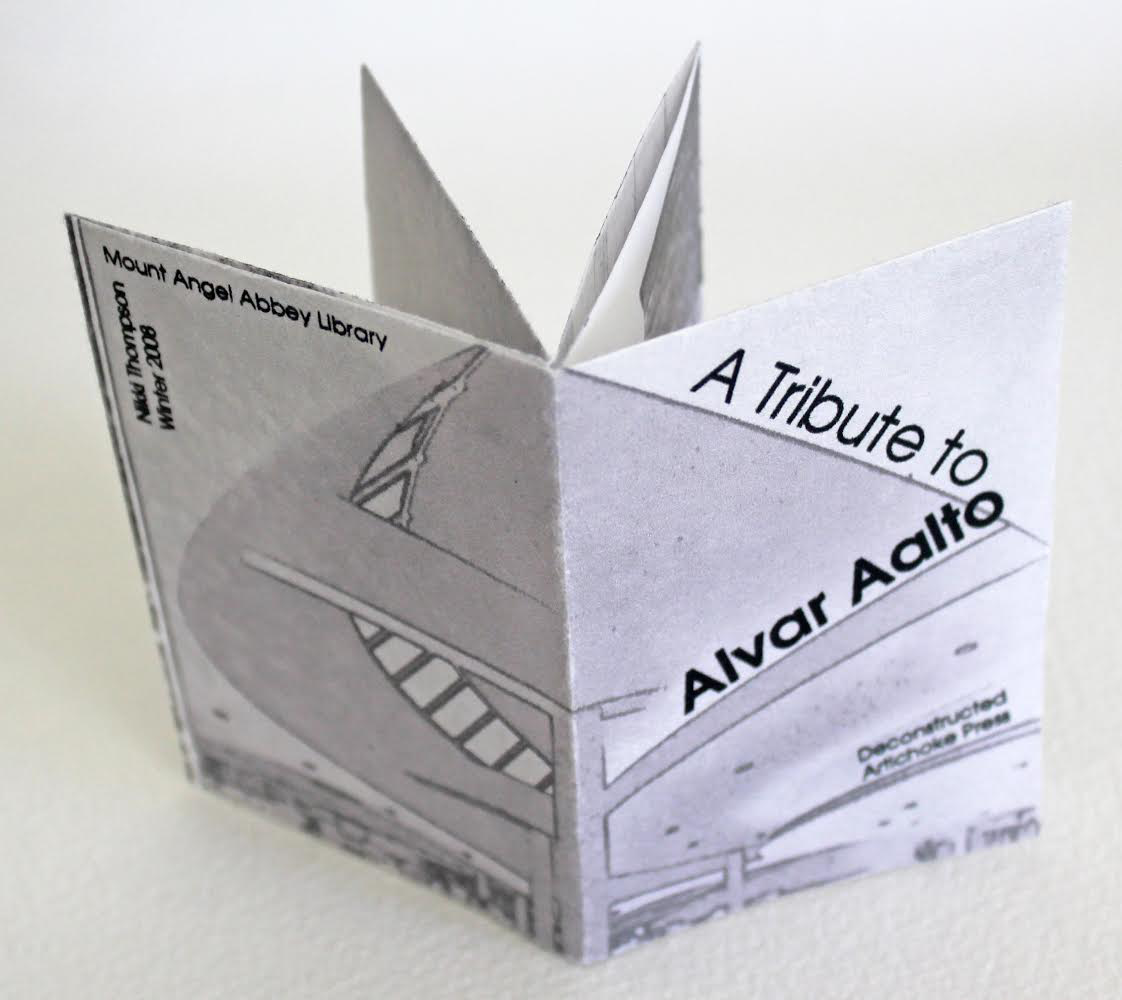

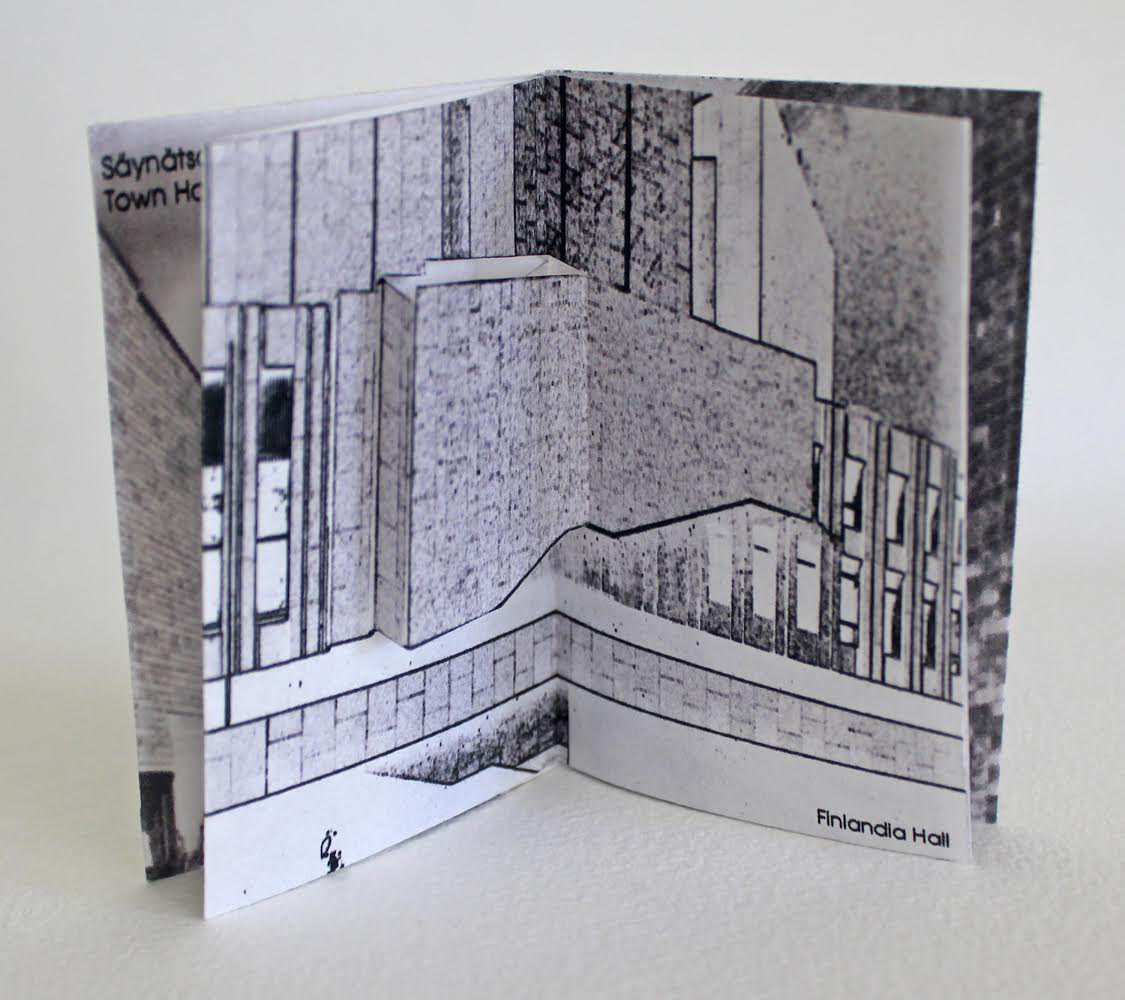

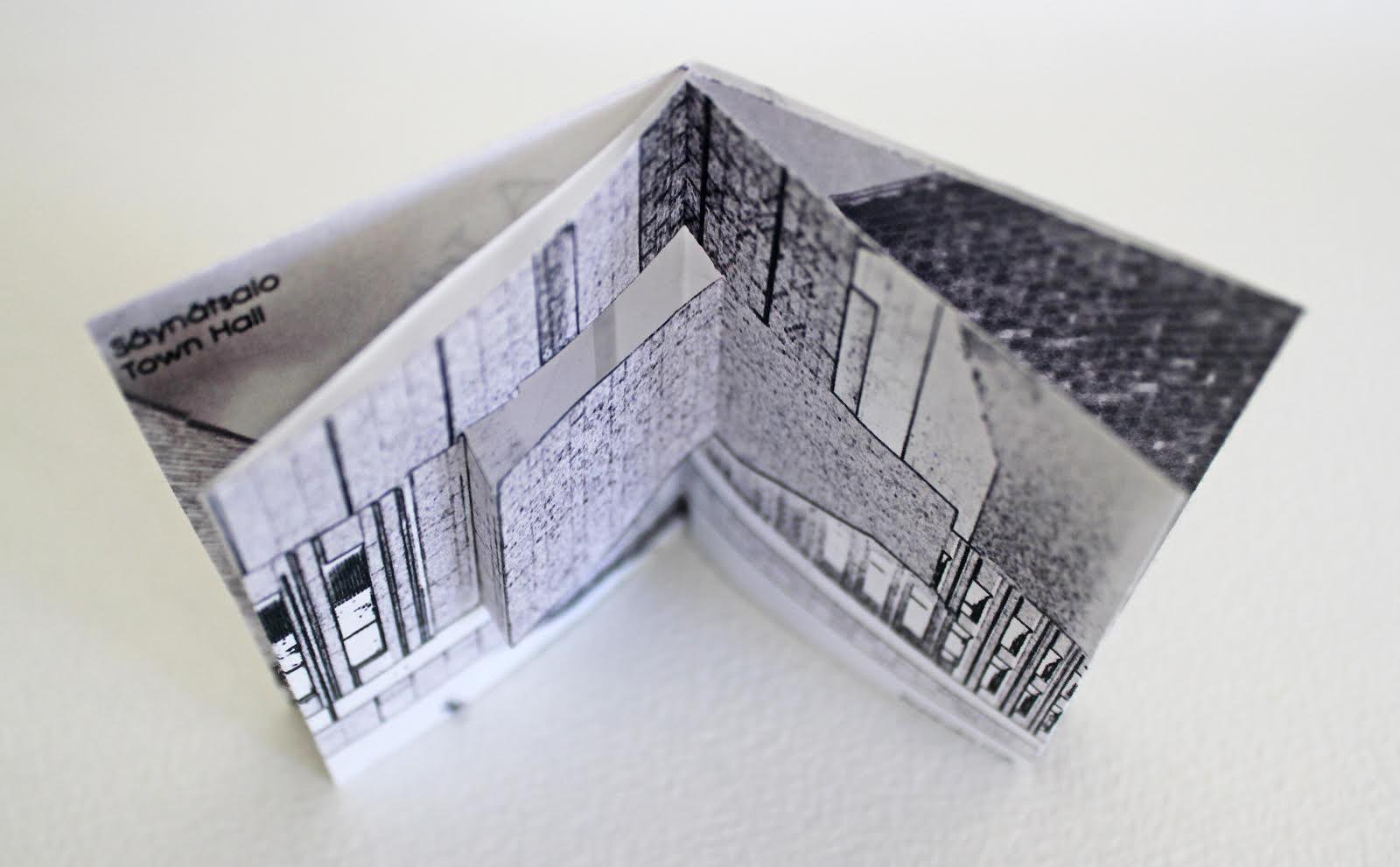

As Daniel Libeskind has said, “For me, a building is a medium to tell a story.” Emily Speed’s Unfolding Architecture (2007) tells the tale of Gordon, a city dweller who witnesses the collapse of public buildings and, ultimately, his own home as the urban fabric begins to unfold around him — a story replicated by the housing’s structure and the book’s accordion fold.

Unfolding Architecture (2007)

Emily Speed

But Ulises Carrión denied that books are about narrative. Instead they are about space and time, which leads to the next proposition.

Proposition #3: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in space and time.

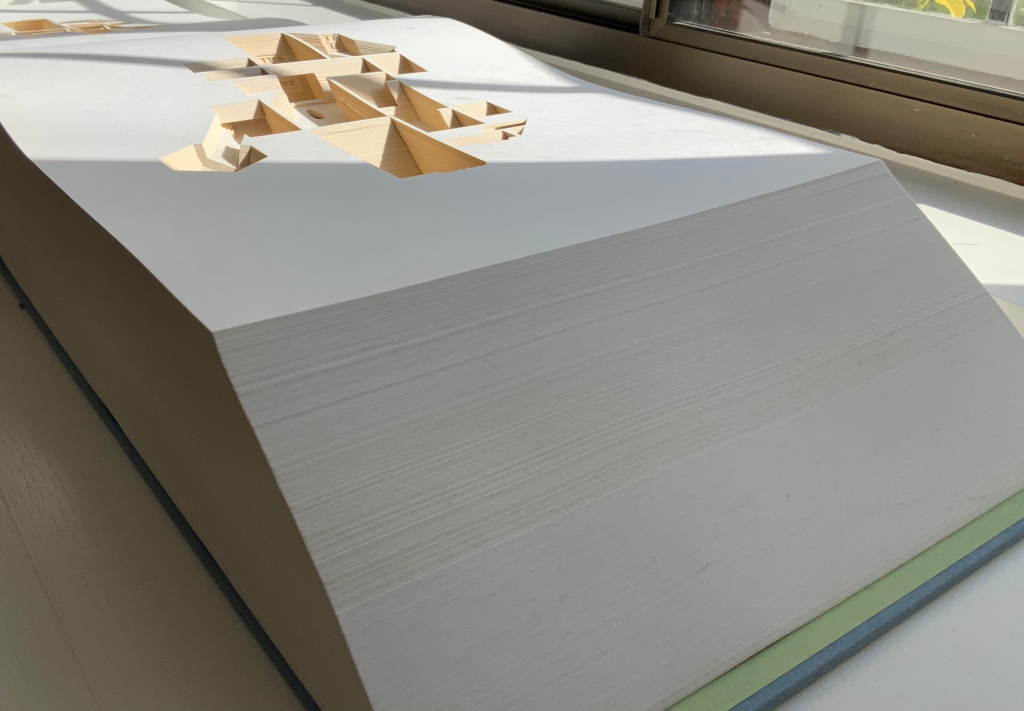

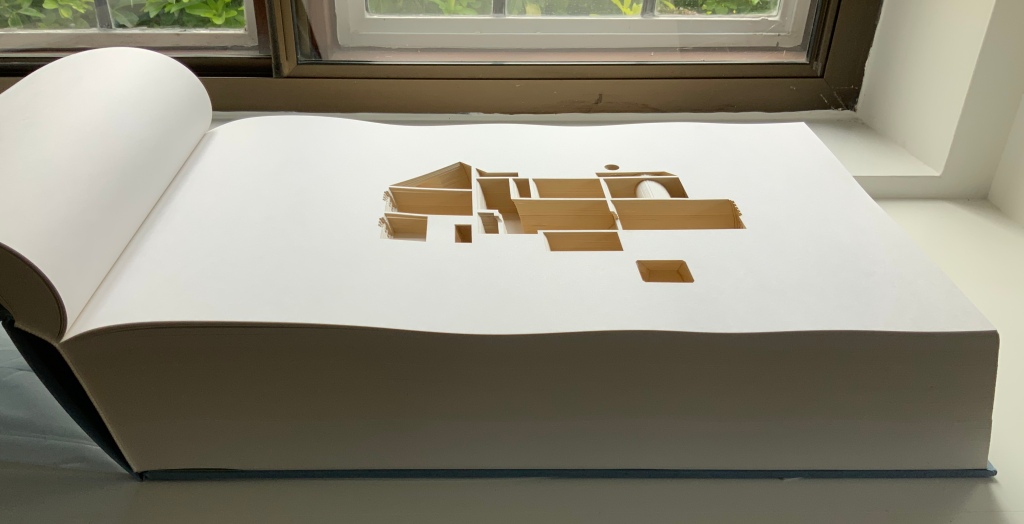

Olafur Eliasson’s Your House (2006) is a laser-cut model of his residence in Copenhagen at a scale of 1:85, which means that each page equates to a 220 mm section of the actual house. In the film Russian Ark (2003), Aleksandr Sokurov made cinematic history with his one continuous shot in 90 minutes, depicting a 17th century time traveller moving through different periods of history as he moves through the rooms of St. Petersburg’s Winter Palace. The film inspired Johan Hybschmann’s Book of Space (2009).

Your House (2006)

Olafur Eliasson

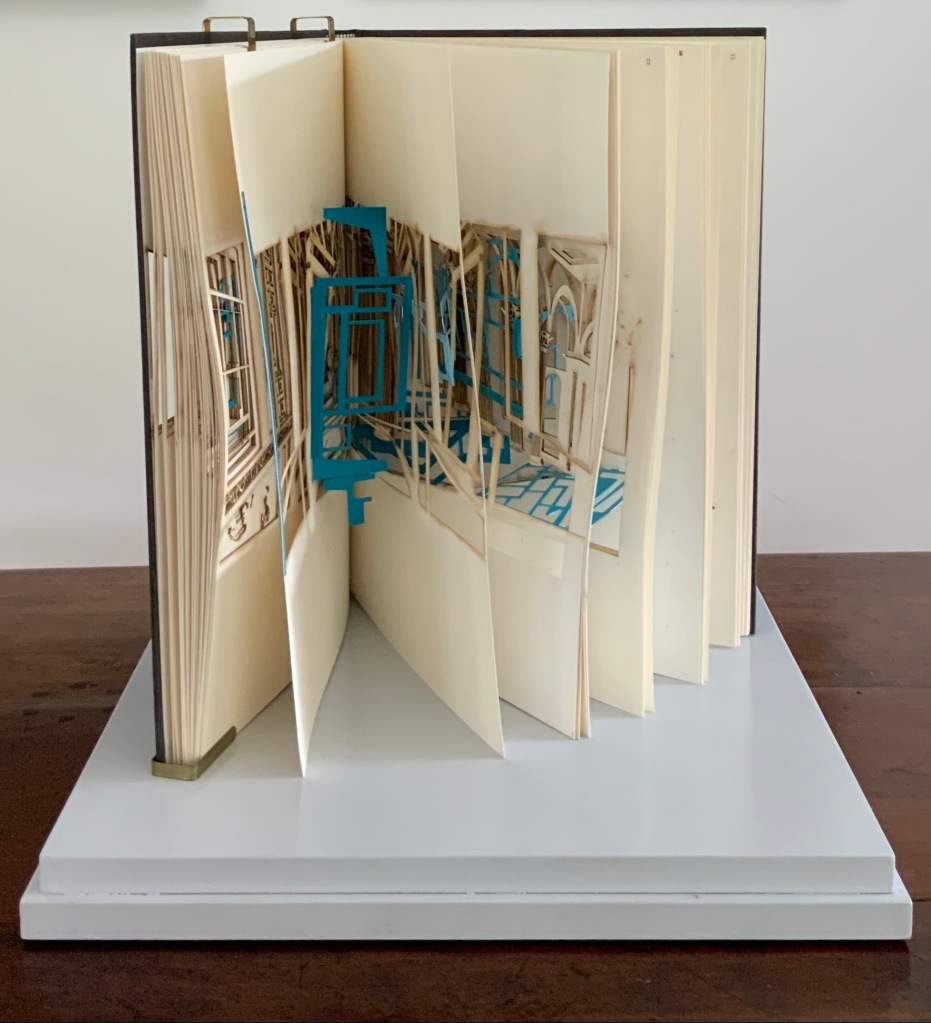

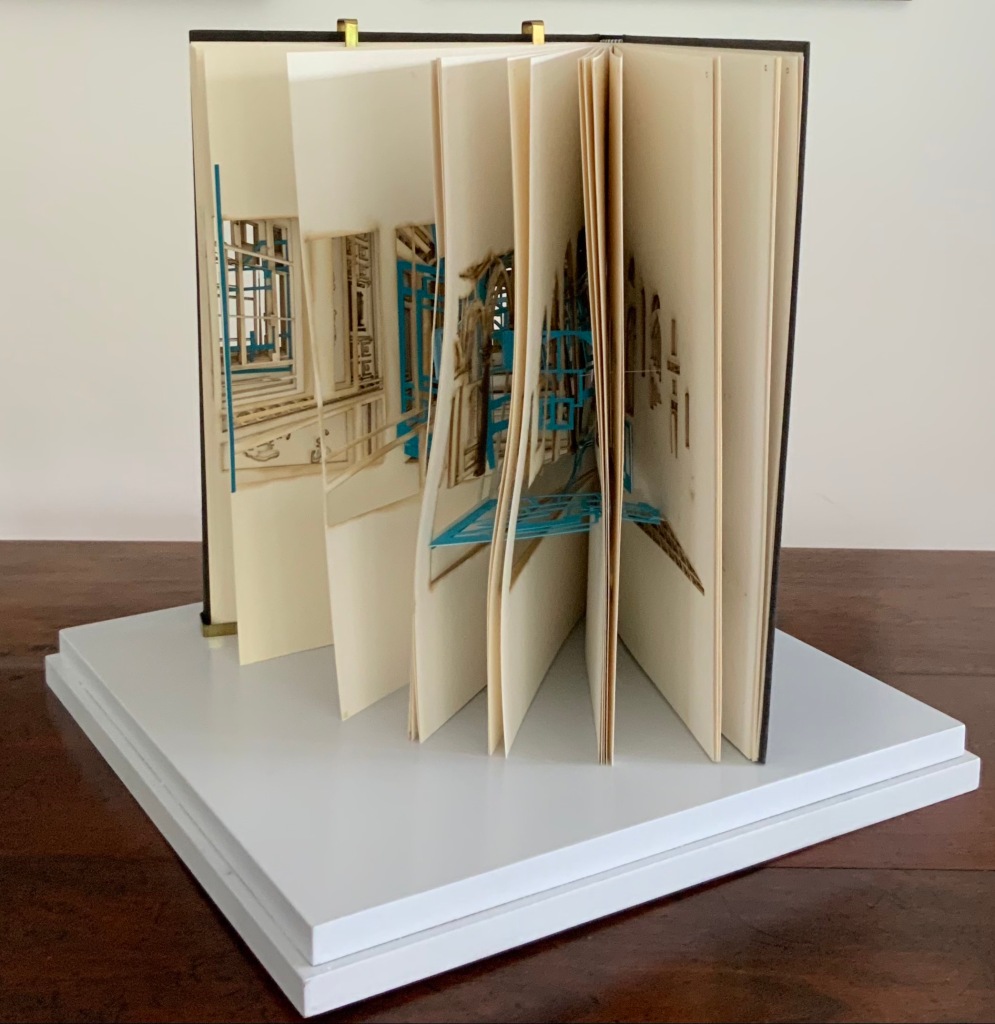

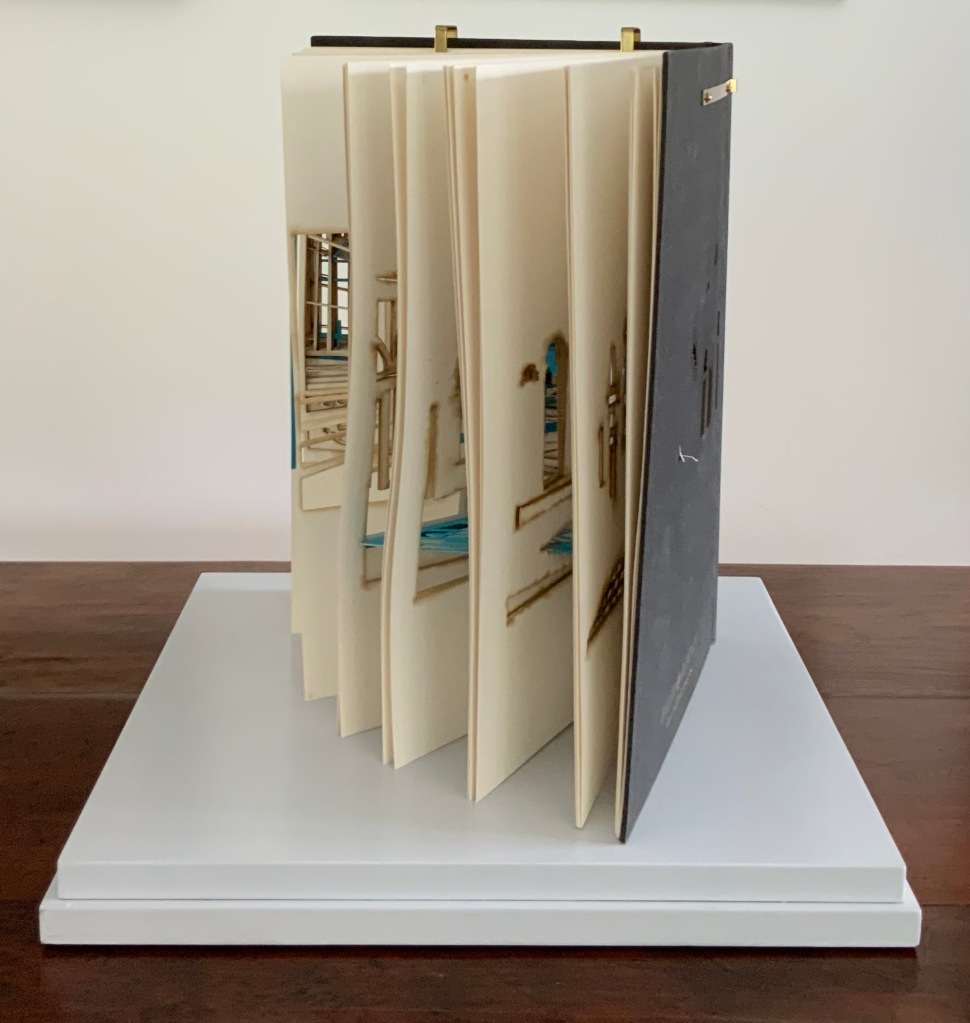

Book of Space (2009)

Johan Hybschmann

How do you read works like this? The size, weight and delicacy of Eliasson’s book and the fragility of Hybschmann’s book and its need for an armature to freeze-frame it defy a simple turning of pages. They must be turned slowly and carefully. Both works heed the task of the arts as posed by architect Juhani Pallasmaa for our age of speed: to defend the comprehensibility of time, its experiential plasticity, tactility and slowness (The Embodied Image, p. 78).

Proposition #4: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in process.

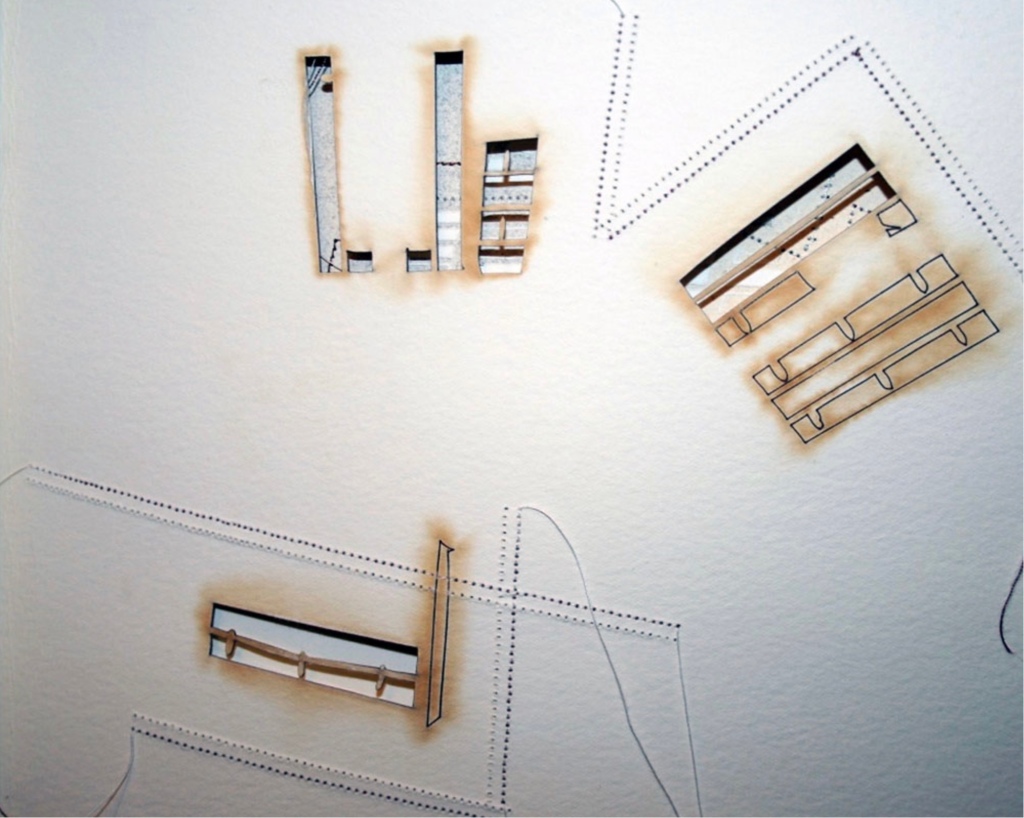

A trained architect and book artist, Marian Macken articulates and illustrates in her book Binding Space why and how the artist’s book can serve as an important tool for design, documentation and critique of architecture. Macken’s perceptive descriptions show how to observe materiality and its functioning and understand how they contribute to the making of art.

Investigating bookness results in the book becoming a highly productive intervening medium with which one can imagine, investigate, analyze, represent and exhibit particular qualities — haptically, and with narrative and ambiguity — of a built environment and the design process. Through the book, we read spatial practice anew (p. 163).

Reading Macken’s book will sharpen the ability of any reader or viewer to appreciate book art, especially her Ise Jingū: Beginning Repeated. Ise Jingū is a Shinto shrine complex in the Mie Prefecture, Japan. “Once every 20 years, since … the seventh century, every fence and building is completely rebuilt on an identical adjoining site, a practice of transposition known as shikinen-zōkan” (Binding Space, p. 101). For Macken, this ritualistic rebuilding poses architecture as performative process rather than as inert object; it “manifests the replication of a beginning, of a process” (p. 100).

Ise Jingū: Beginning Repeated (2011)

Marian Macken

Macken’s artwork consists of 61 loose sheets with a watermarked image within each, the number reflecting the 61 iterations of the shrine up until the making of this work of book art. The watermark is a perspective image based on Yoshio Watanabe’s photograph of the Inner Shrine, taken in 1953 on the occasion of the 59th rebuilding. The contrast of the watermark in kozo and the movement of its placement from one sheet to the next entice reflection on the phenomenon of representation and the architectural process of shikinen-zōkan.

Proposition #5: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in phenomenology.

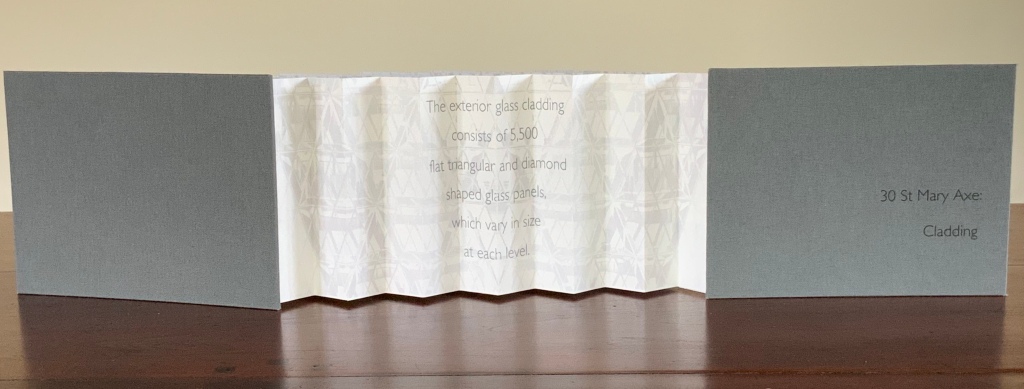

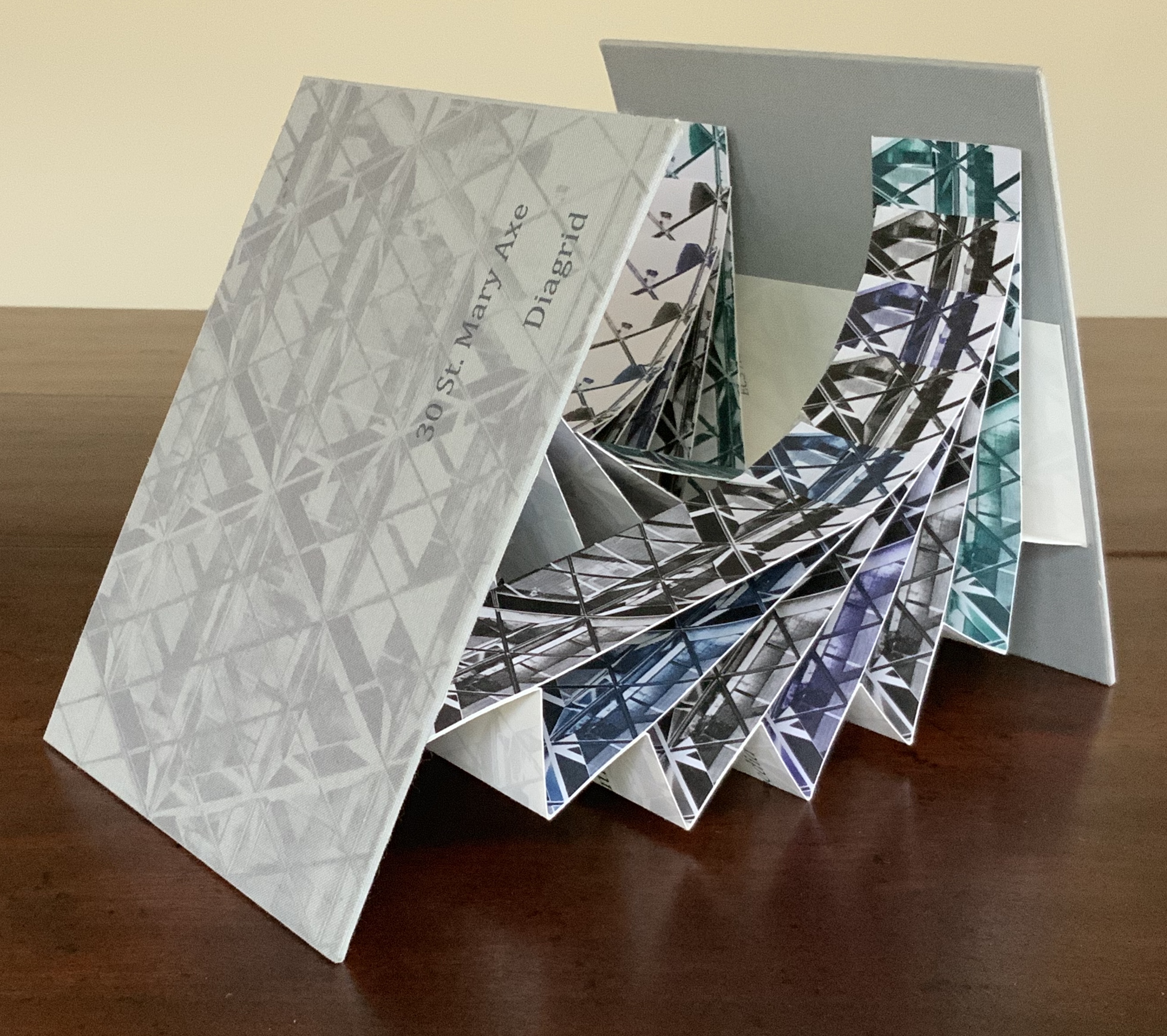

Architects such as Alfredo Muñoz and his firm ABIBOO, Juhani Pallasmaa and Peter Zumthor are among those often associated with architectural phenomenology, concerned with perception psychology, focused on the primacy of sensory and experiential qualities. Norman Foster and phenomenology are not so often yoked, but 30 St Mary Axe: Diagrid (2009) and 30 St. Mary Axe: Cladding (2009)– Mandy Brannan’s treatments of his iconic London office tower (aka “the Gherkin”) that refocus the perception and experience of it — might prompt reconsideration.

Top: 30 St Mary Axe: Cladding (2009). Bottom: 30 St Mary Axe: Diagrid (2009)

Mandy Brannan

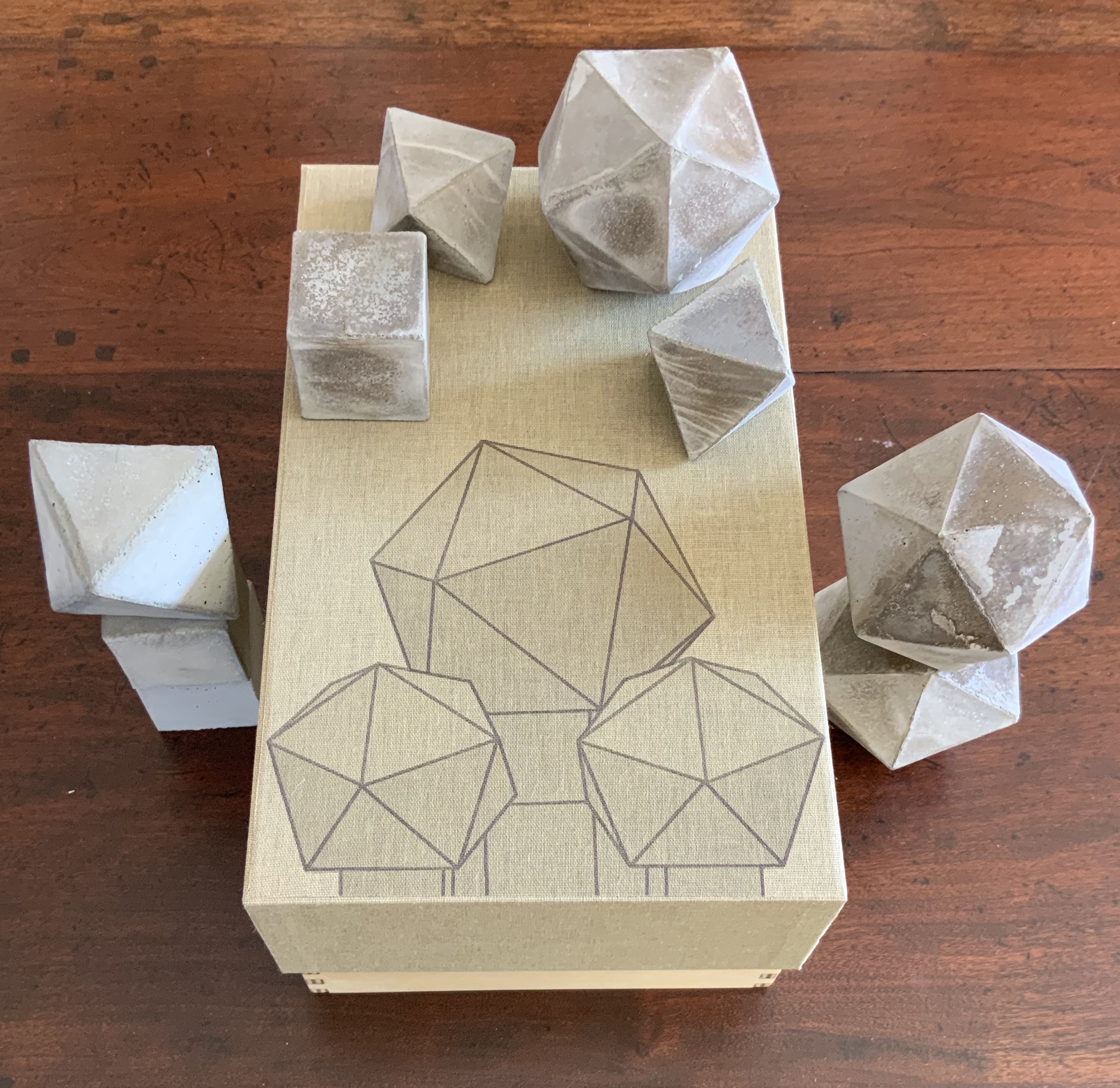

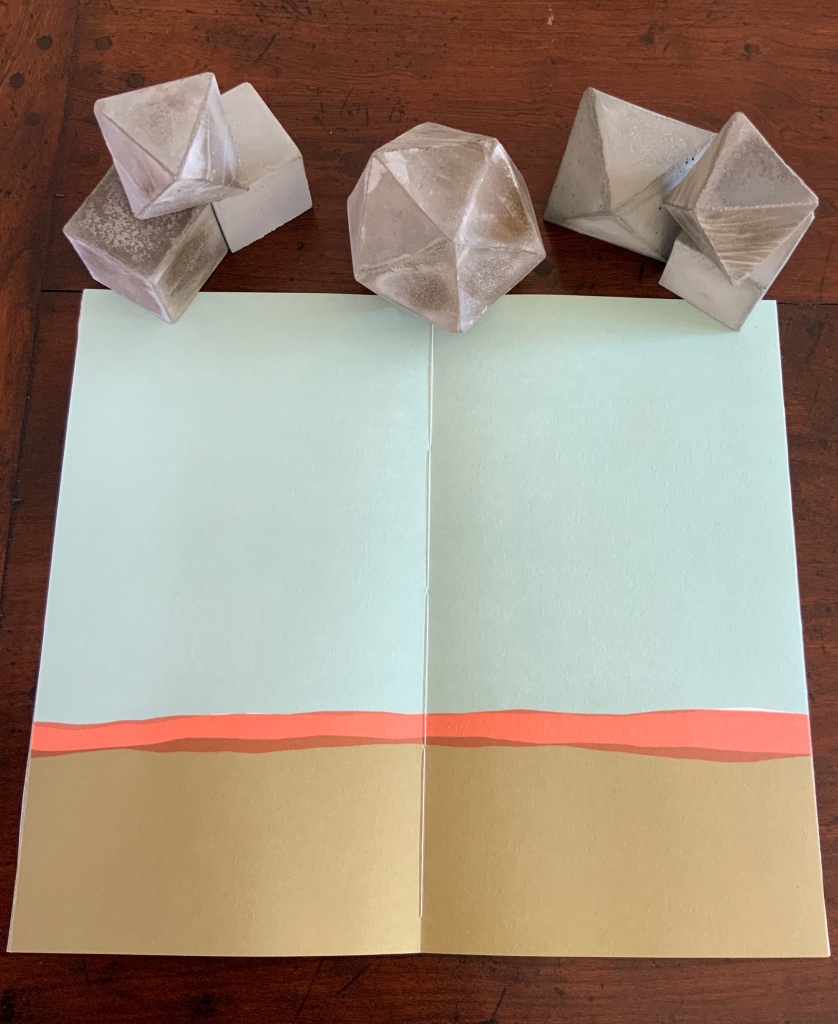

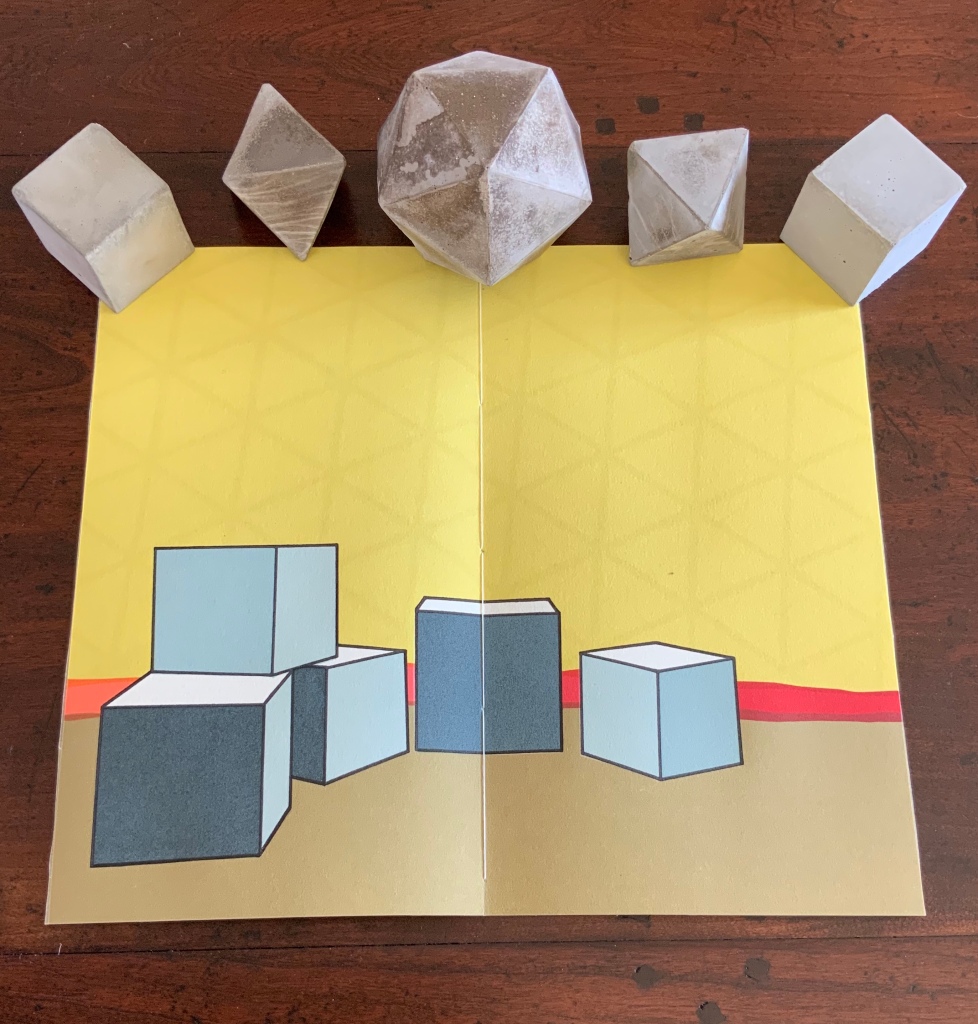

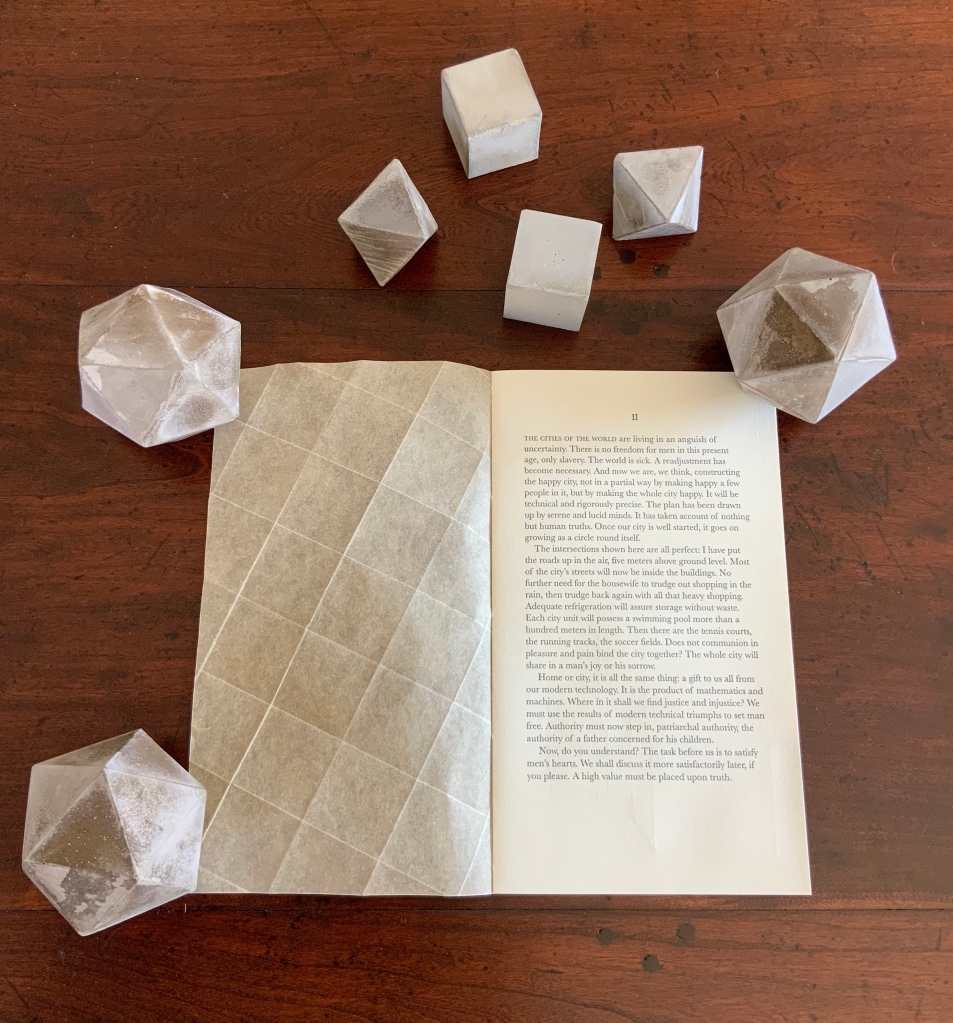

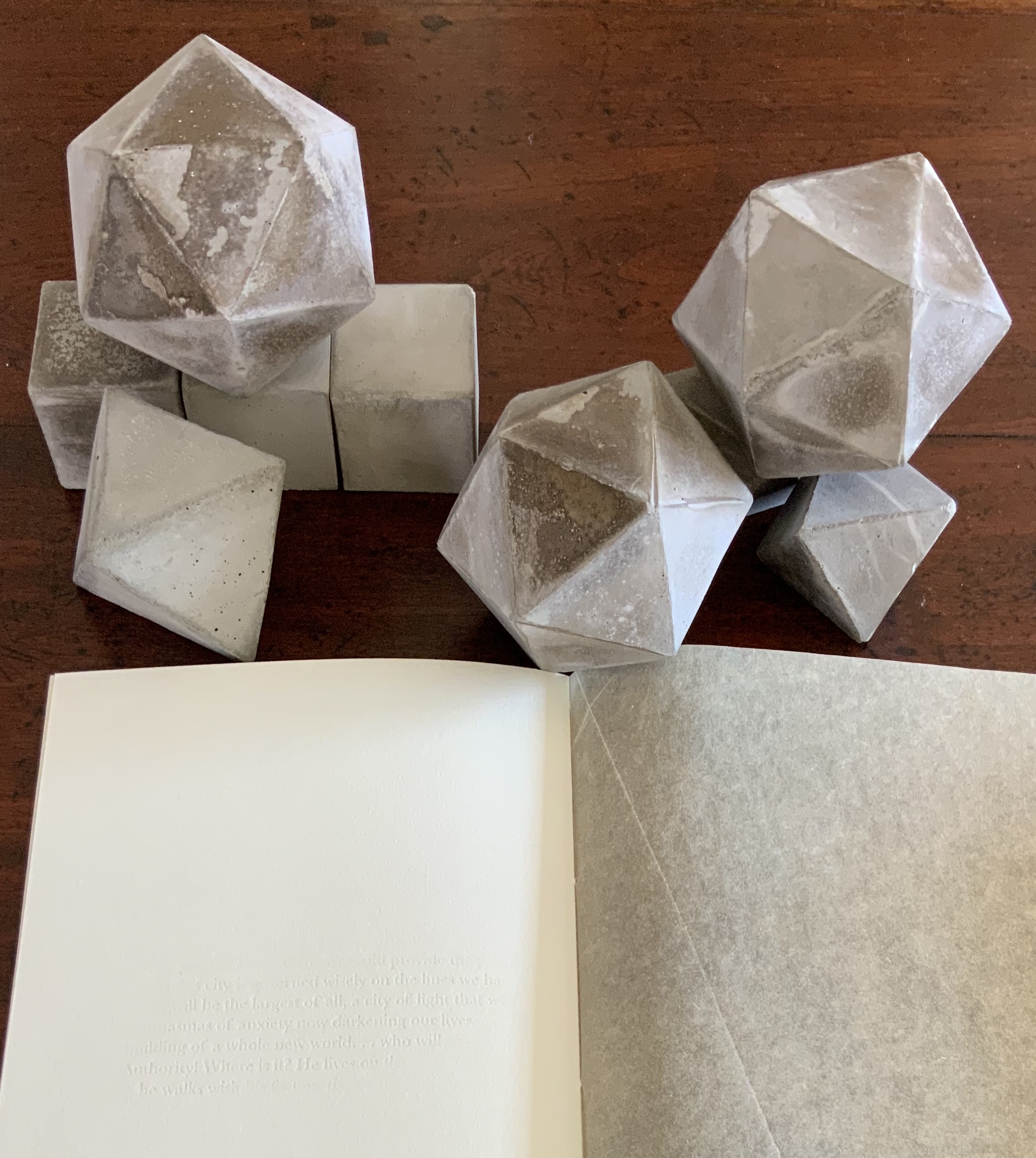

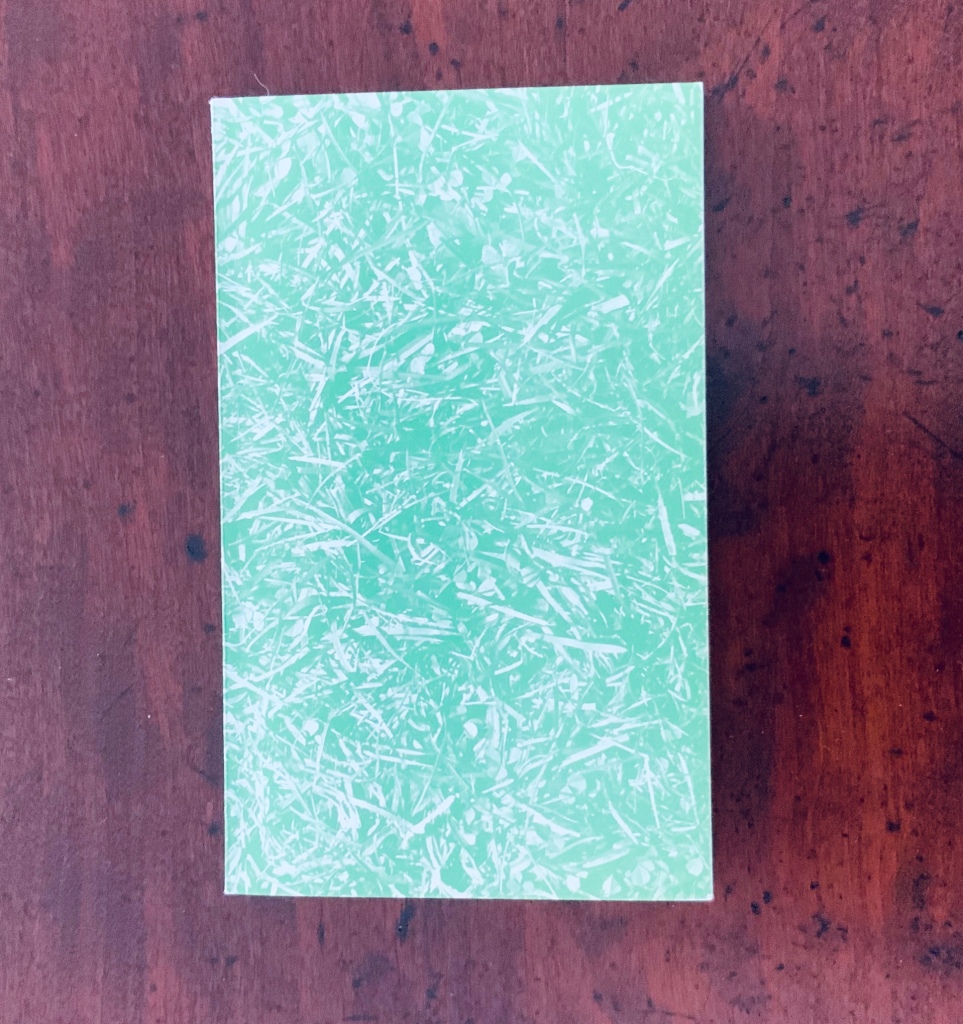

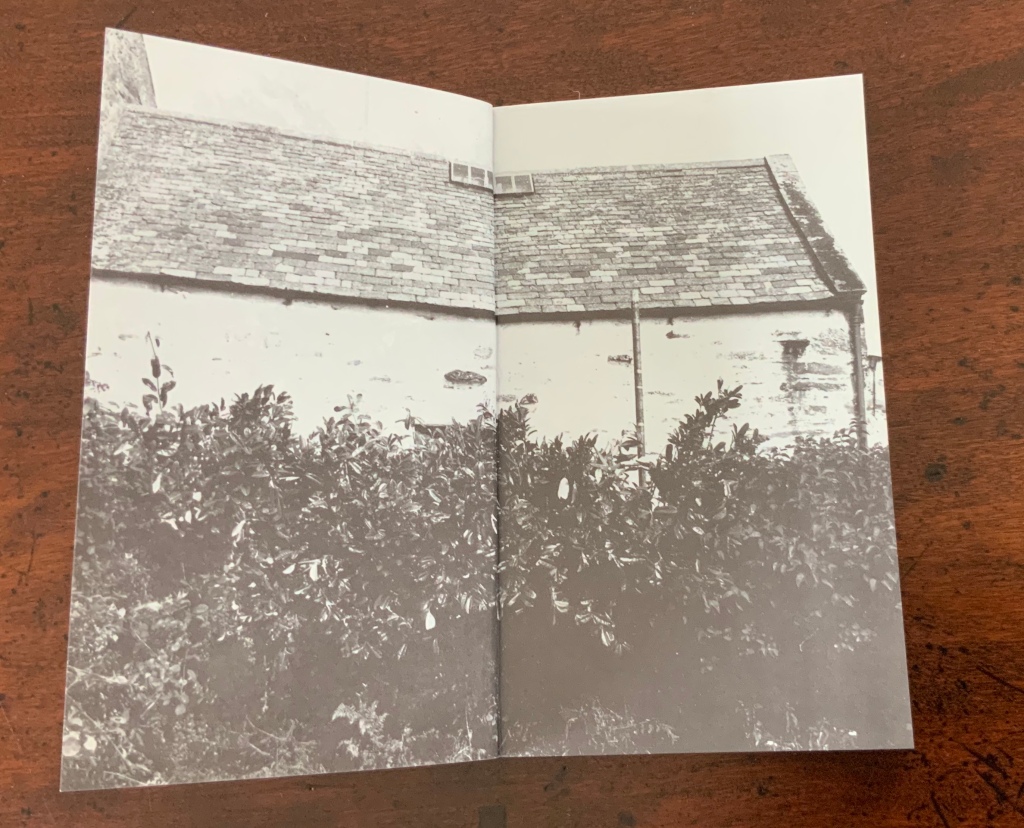

Proposition #6: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in geometry.

Sarah Bryant’s The Radiant Republic (2019) insightfully integrates Plato’s and Le Corbusier’s texts and ideas. The very physicality of the blond wood, linen cover, glass window, concrete representations of Platonic solids, embossed type and sewn papers could easily be a response to Juhani Pallasmaa’s comment: “The current overemphasis on the intellectual and conceptual dimensions of architecture contributes to the disappearance of its physical, sensual and embodied essence” (The Eyes of the Skin, p. 35).

The Radiant Republic (2019)

Sarah Bryant

Proposition #7: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in modelling.

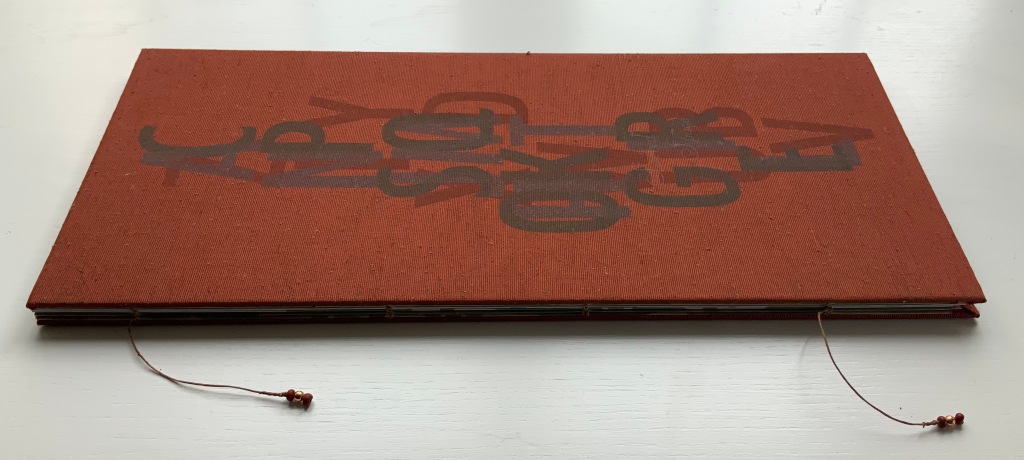

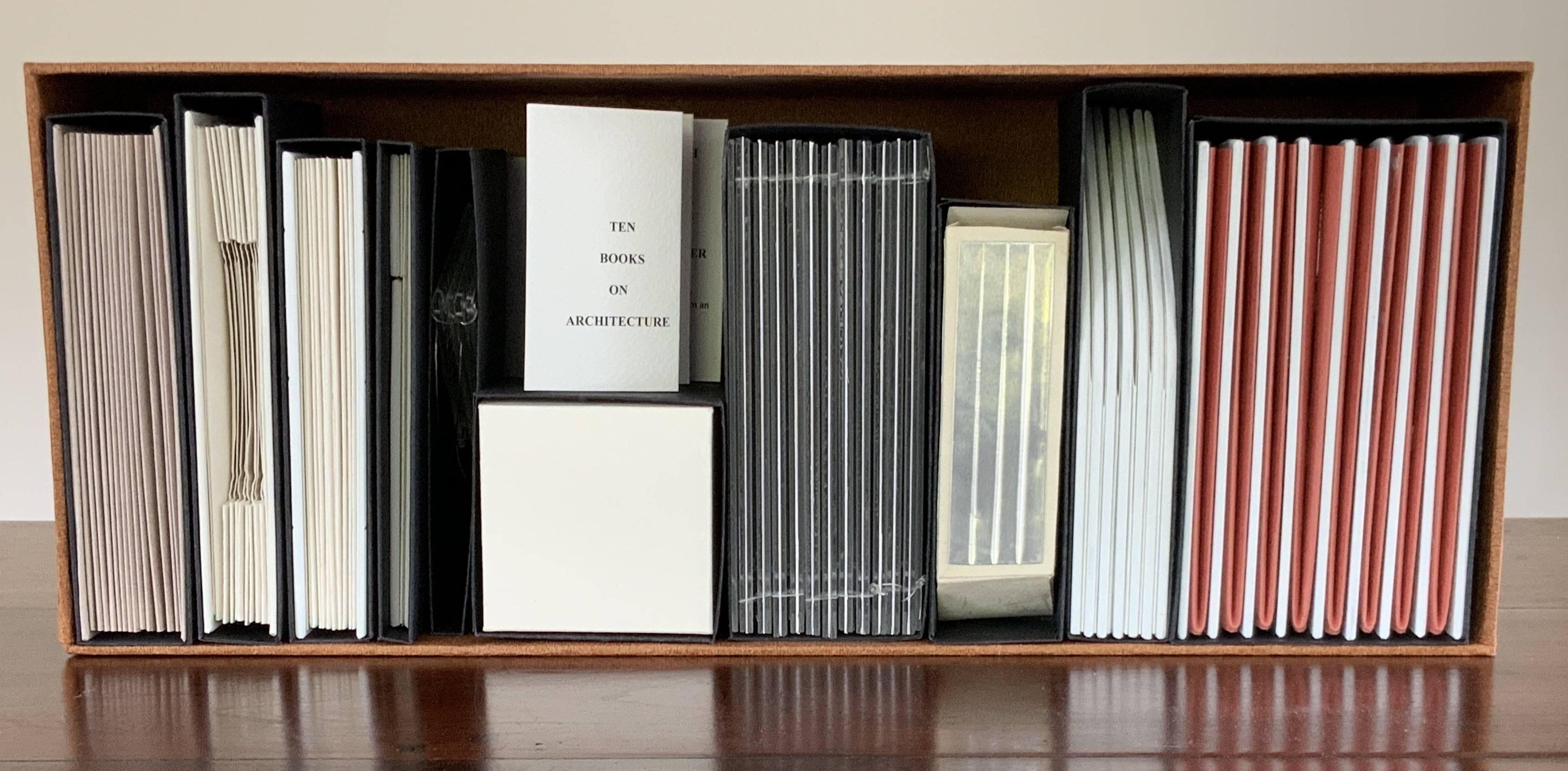

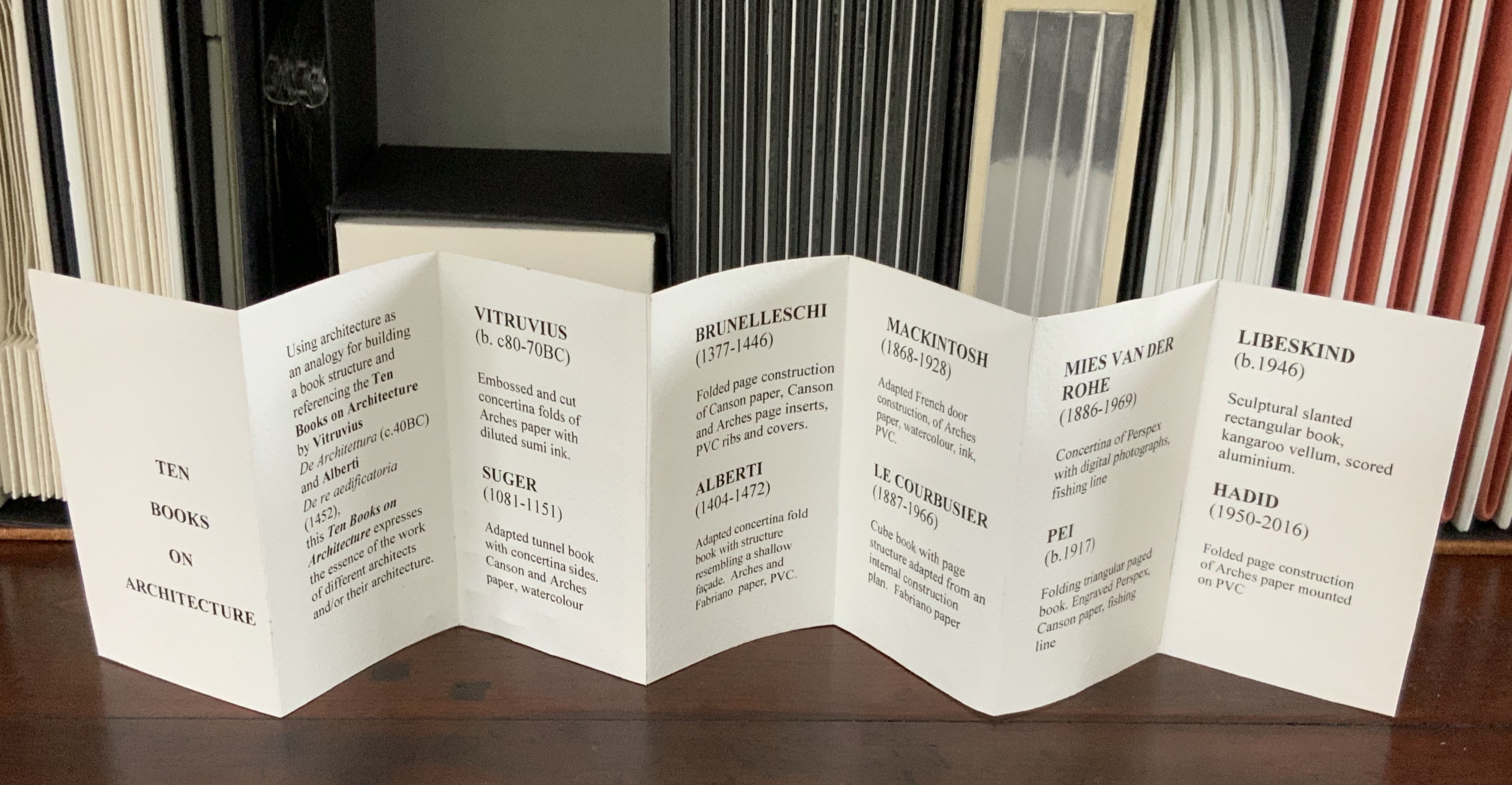

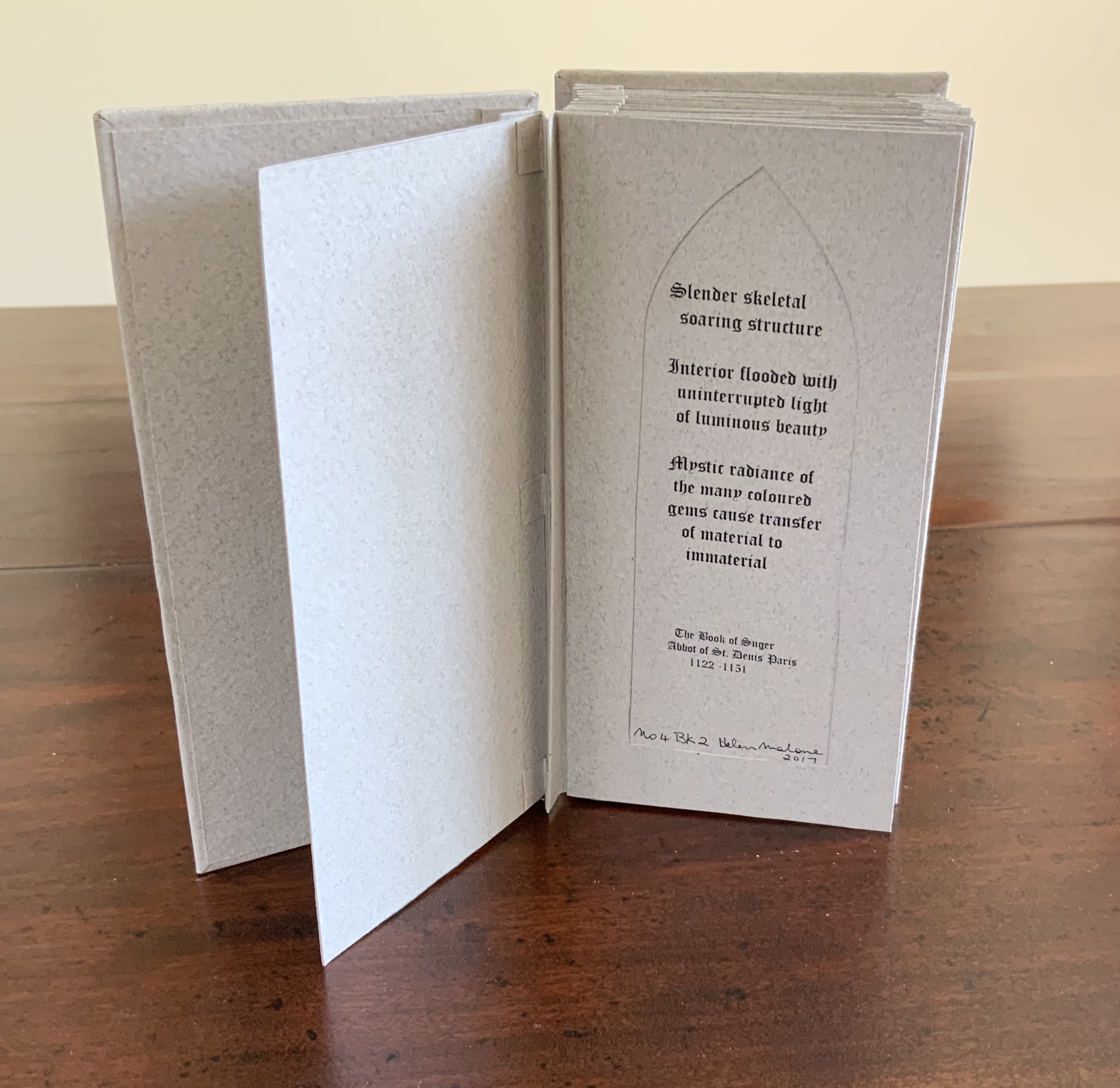

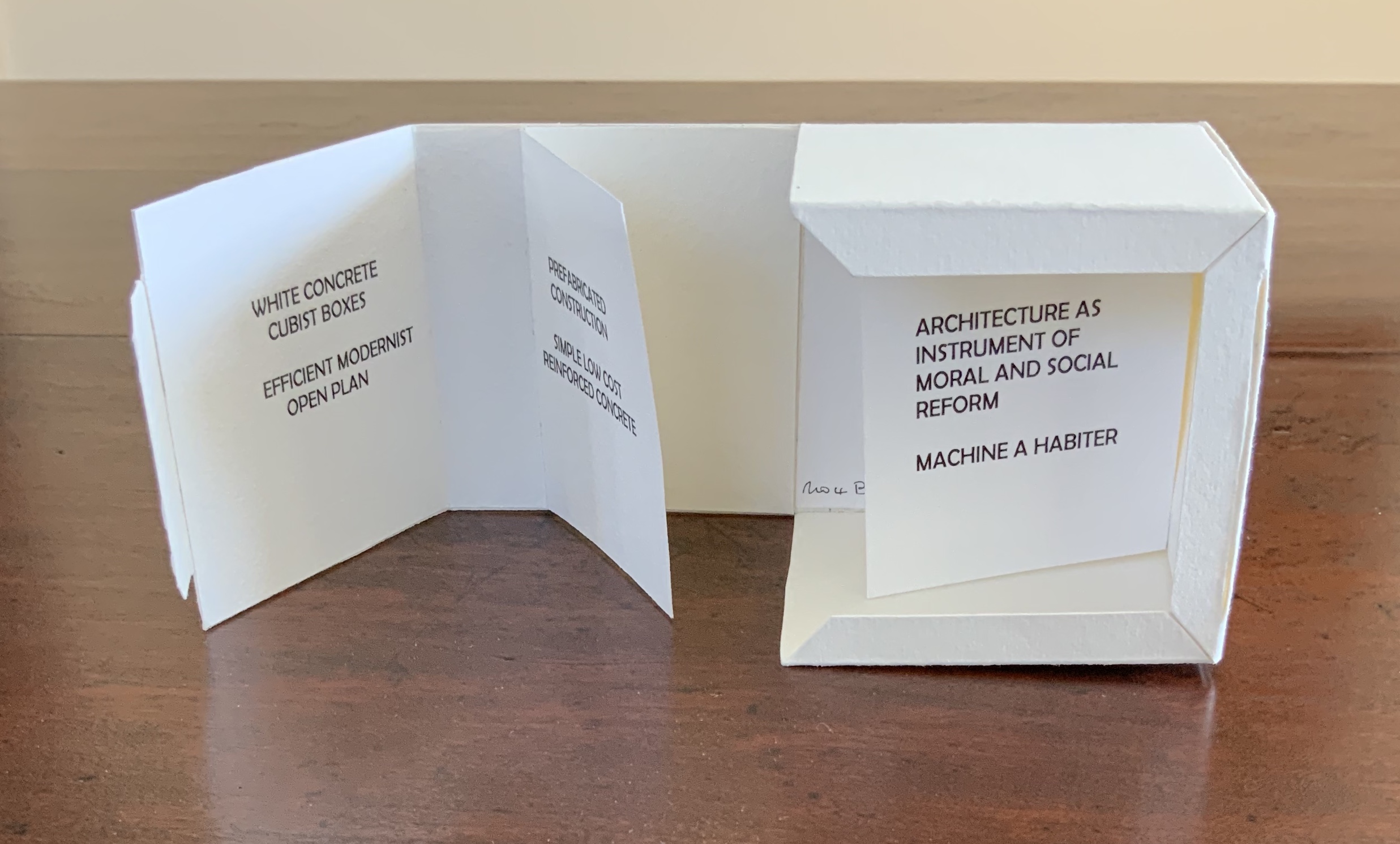

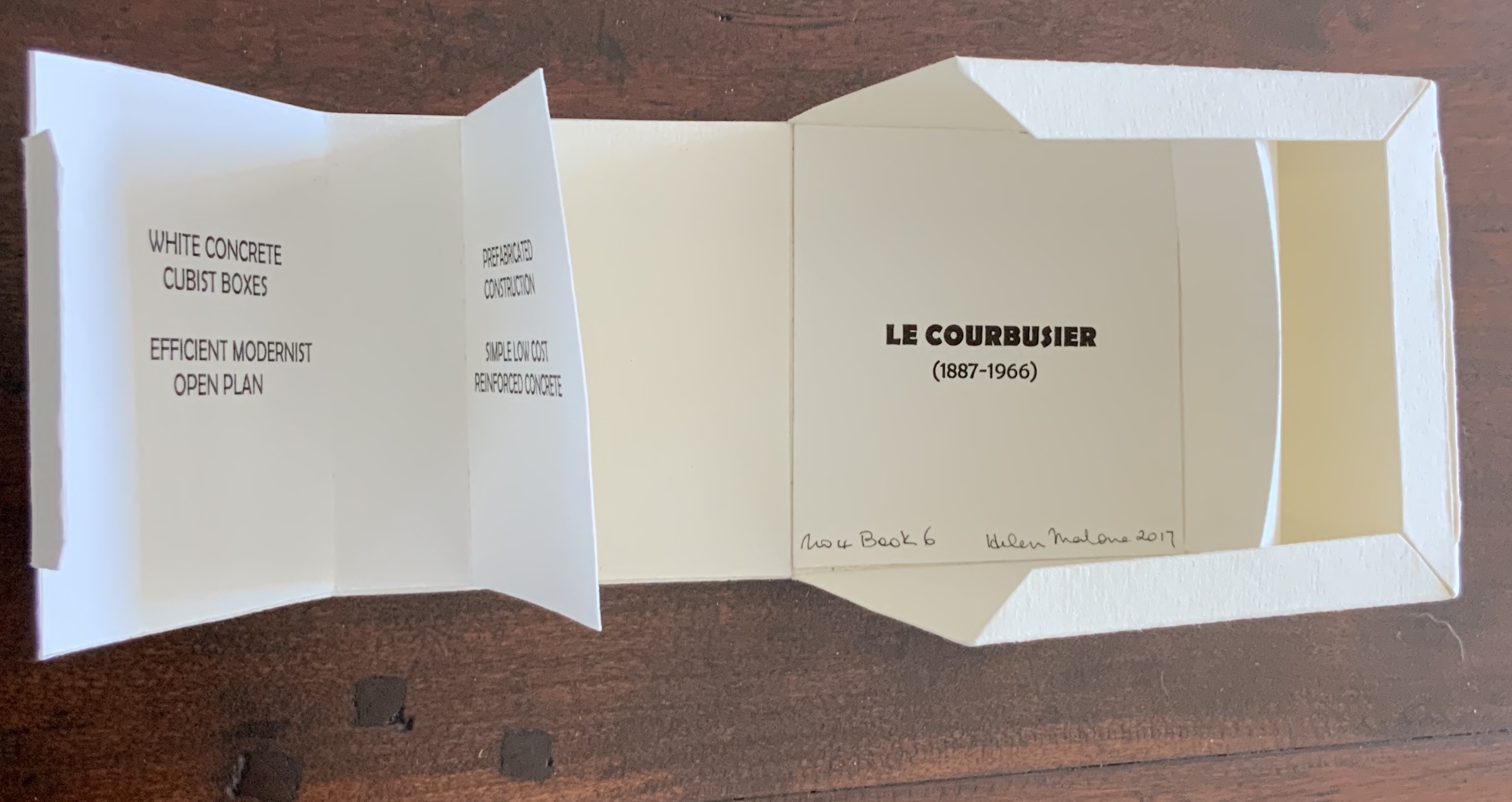

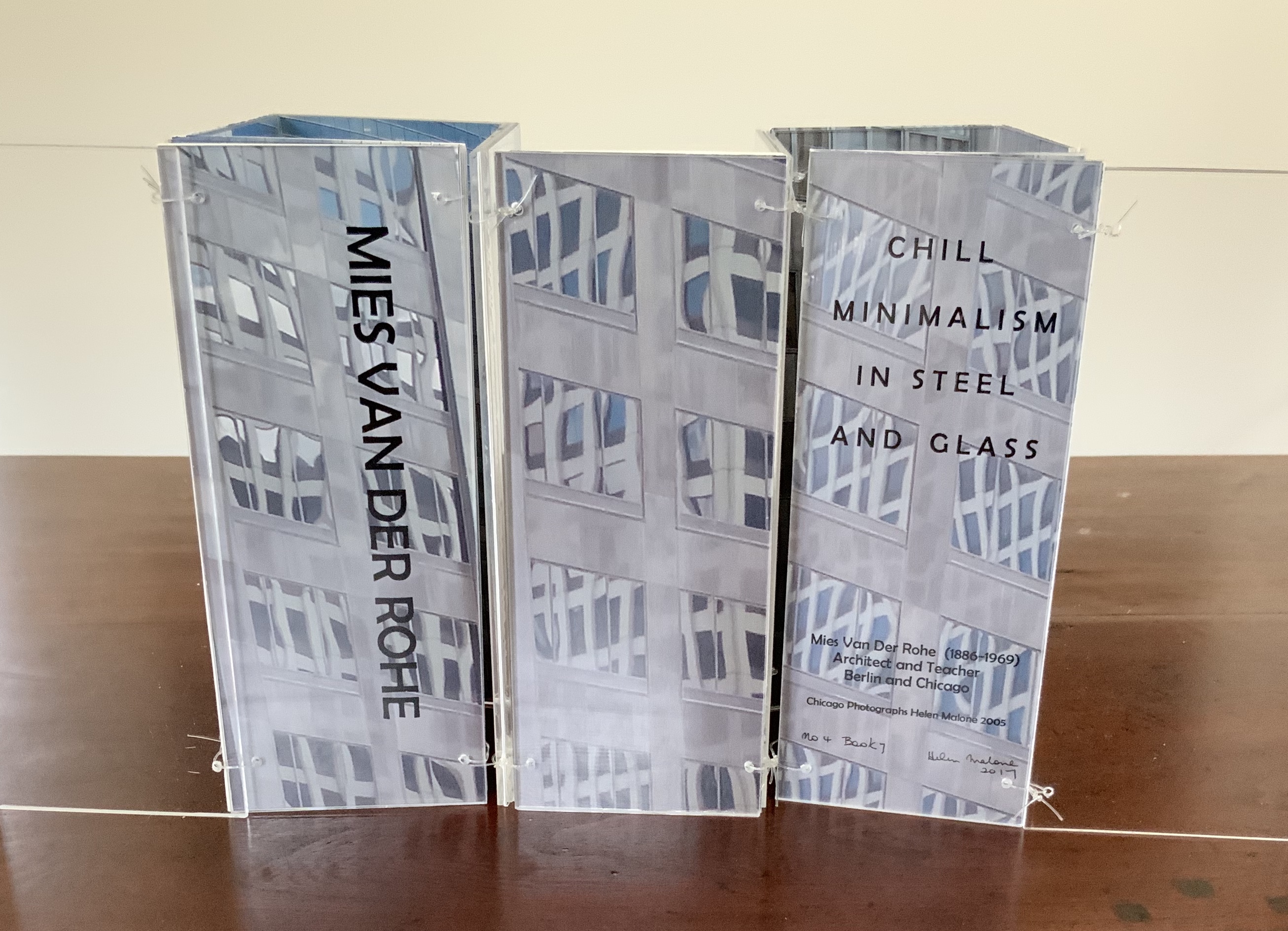

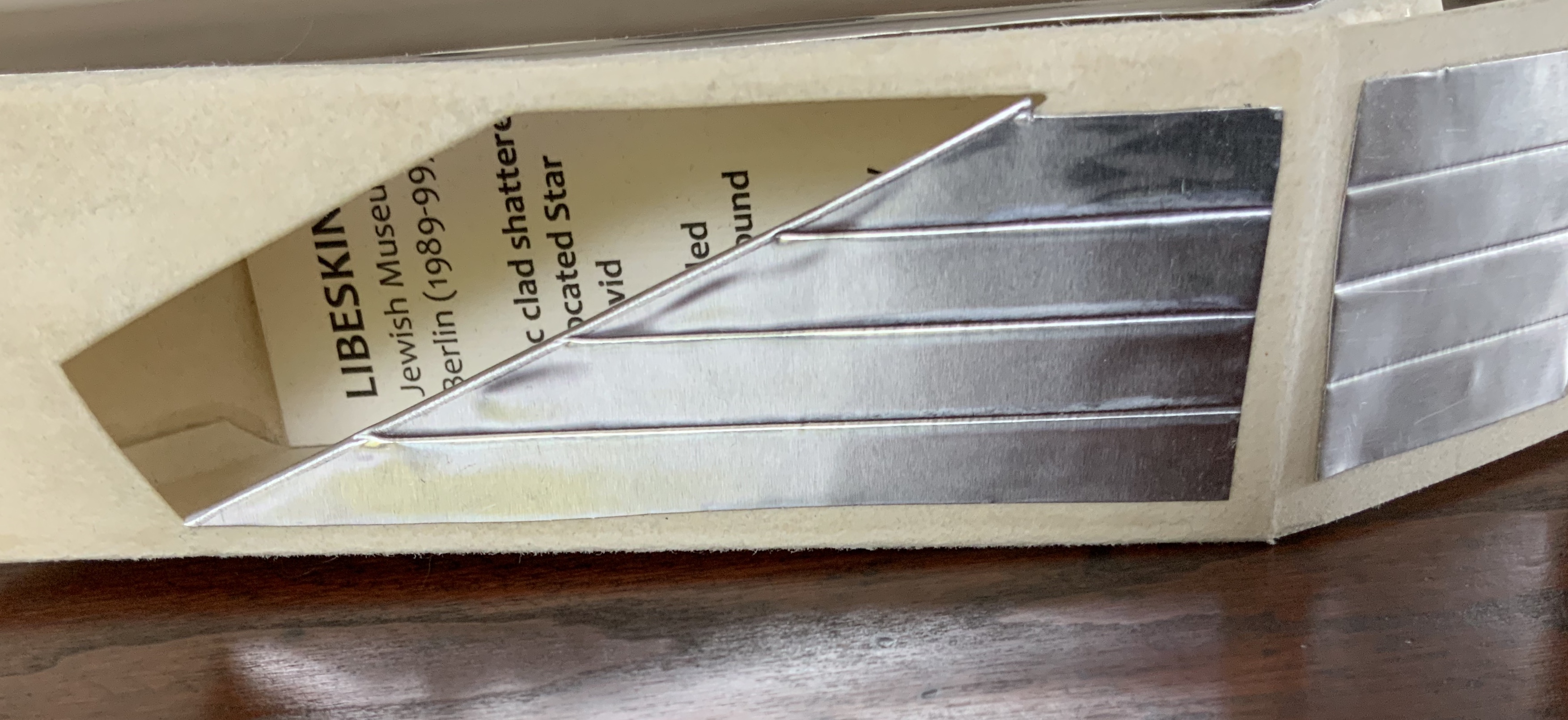

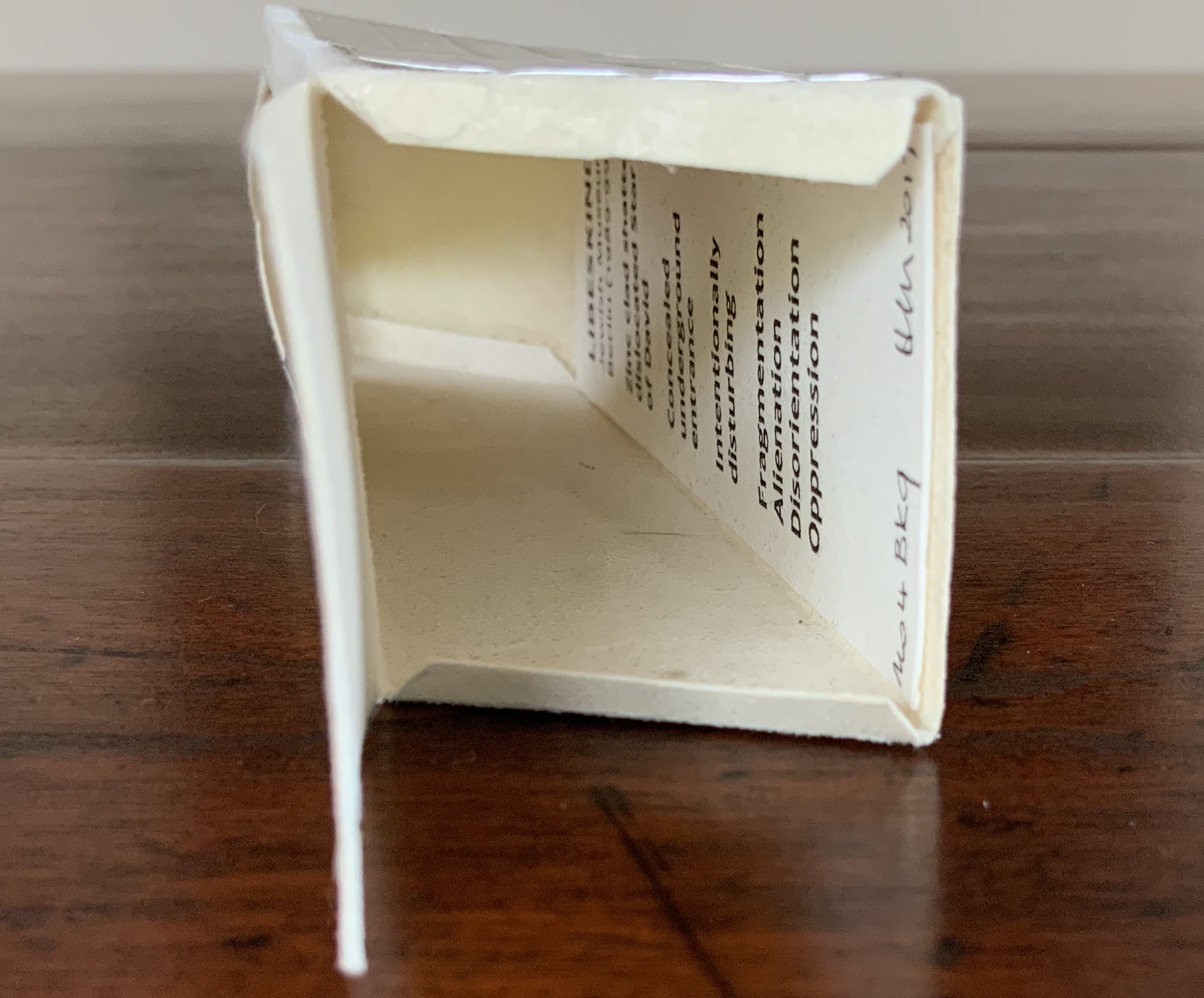

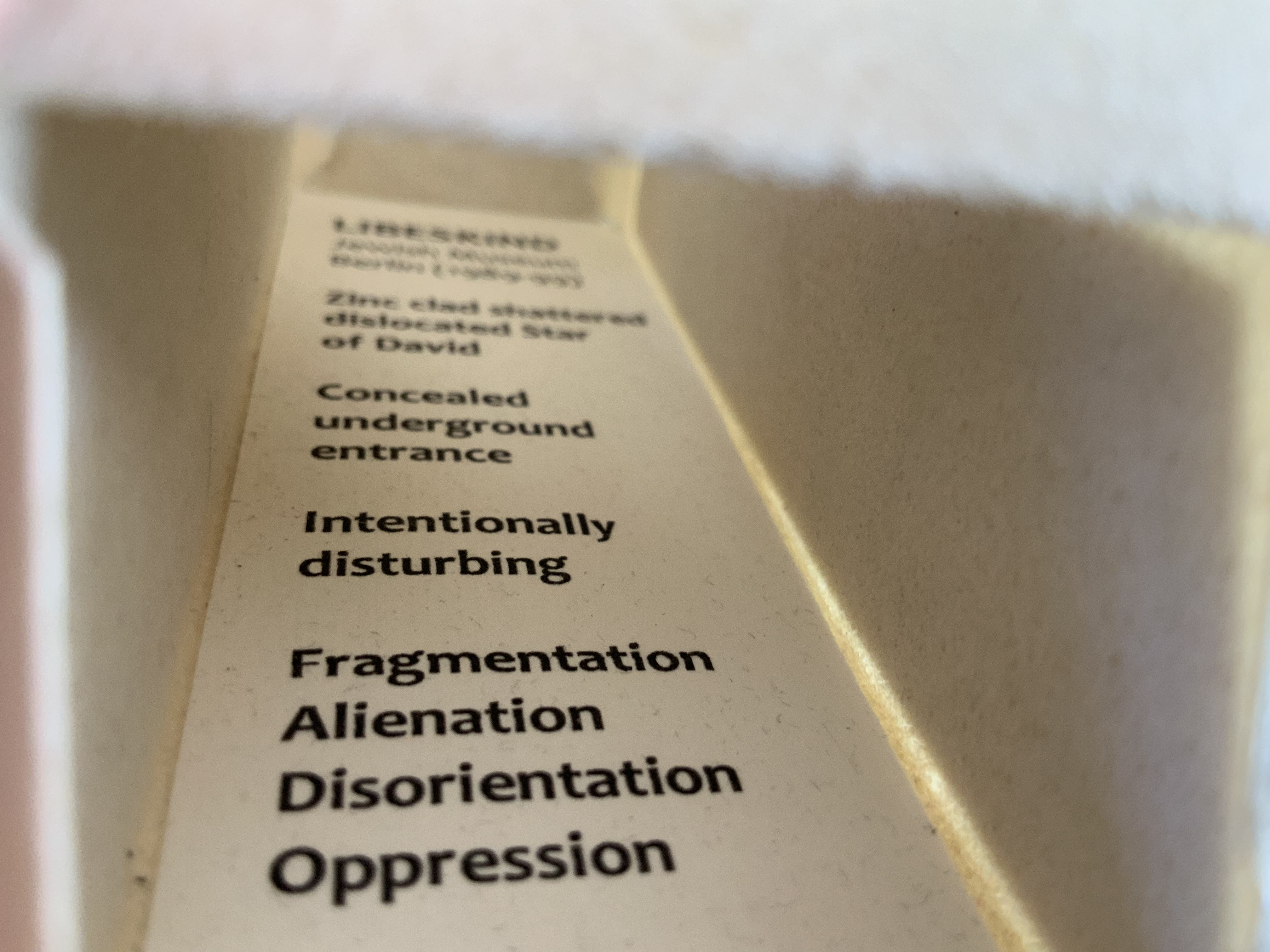

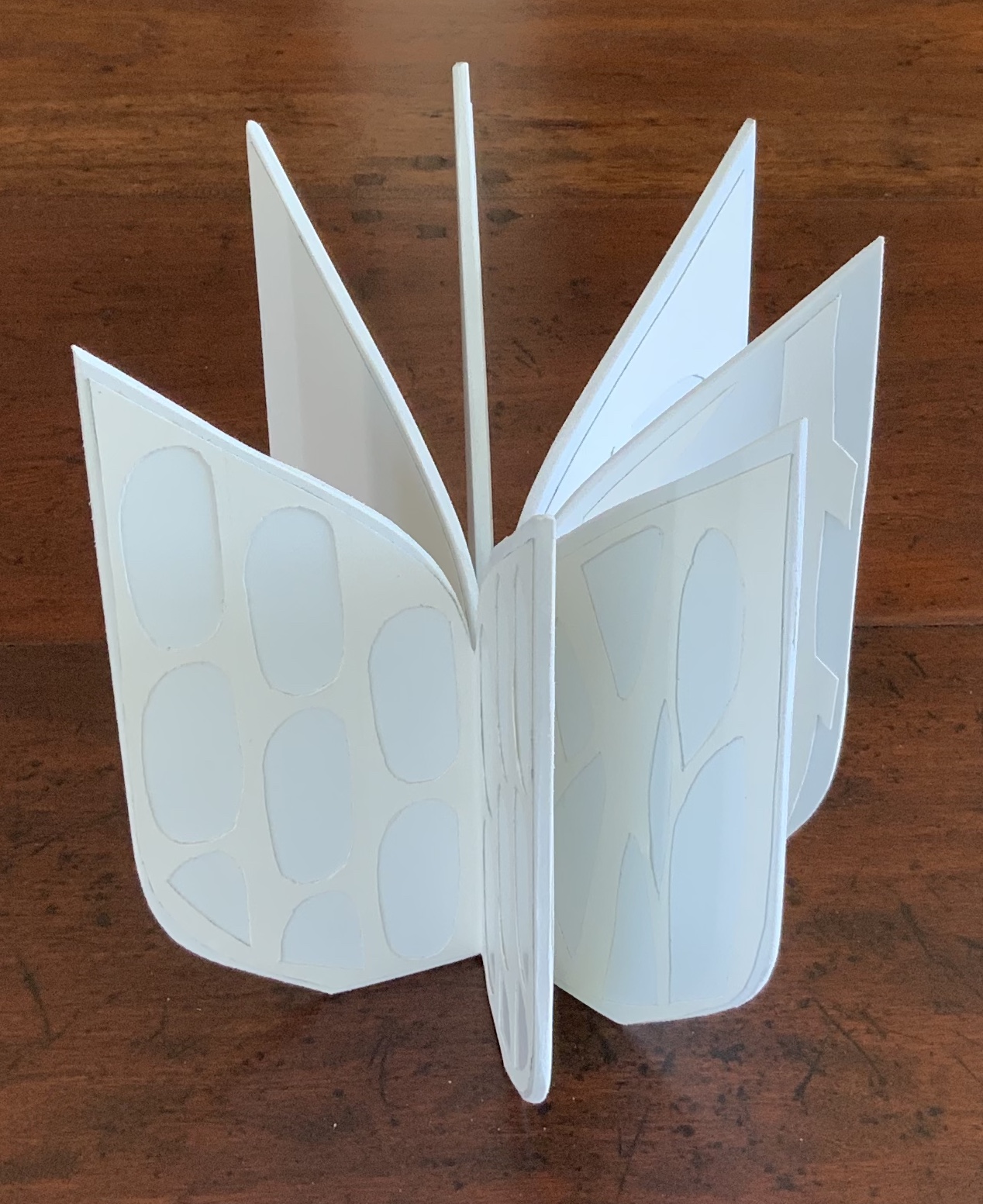

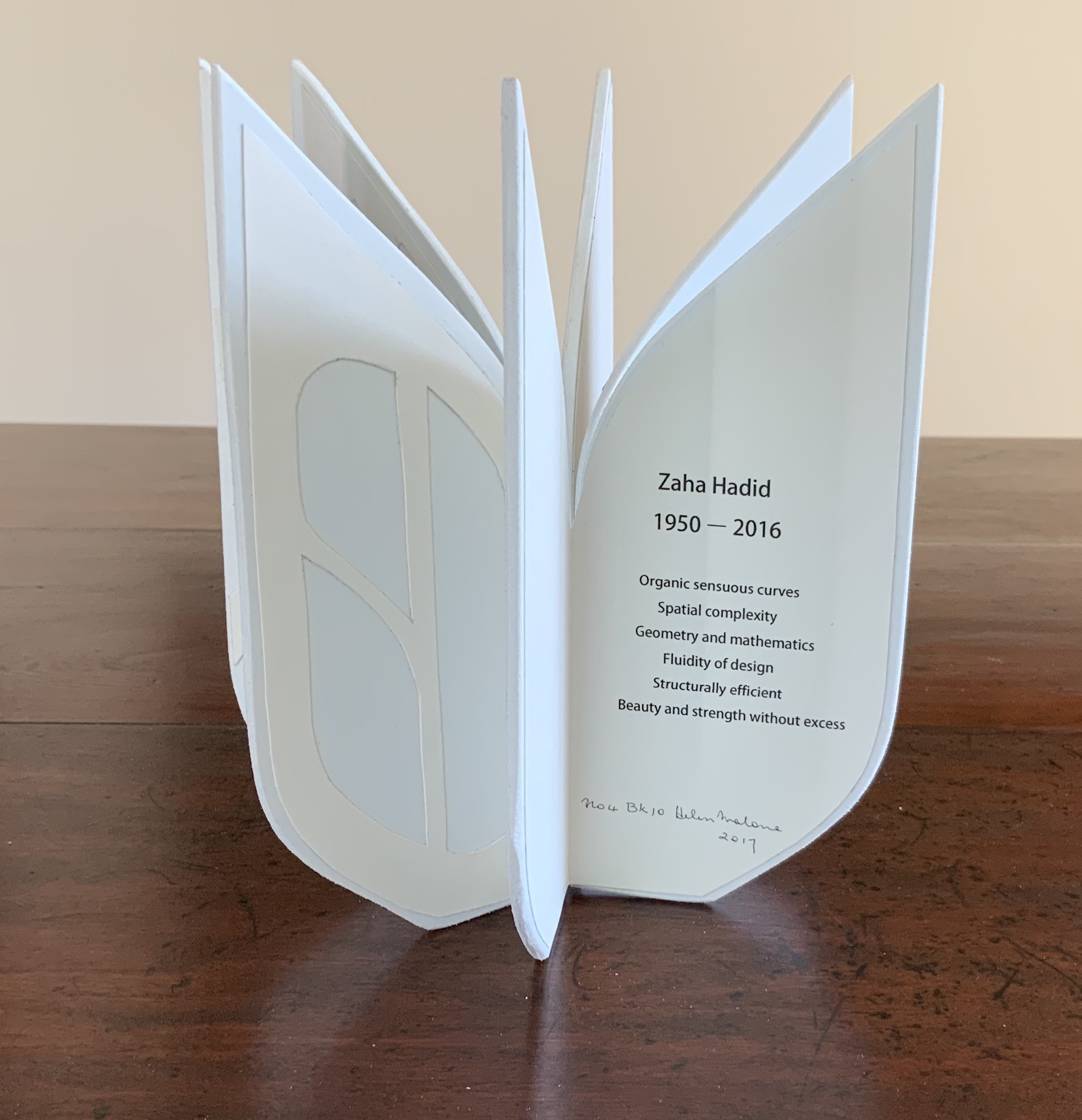

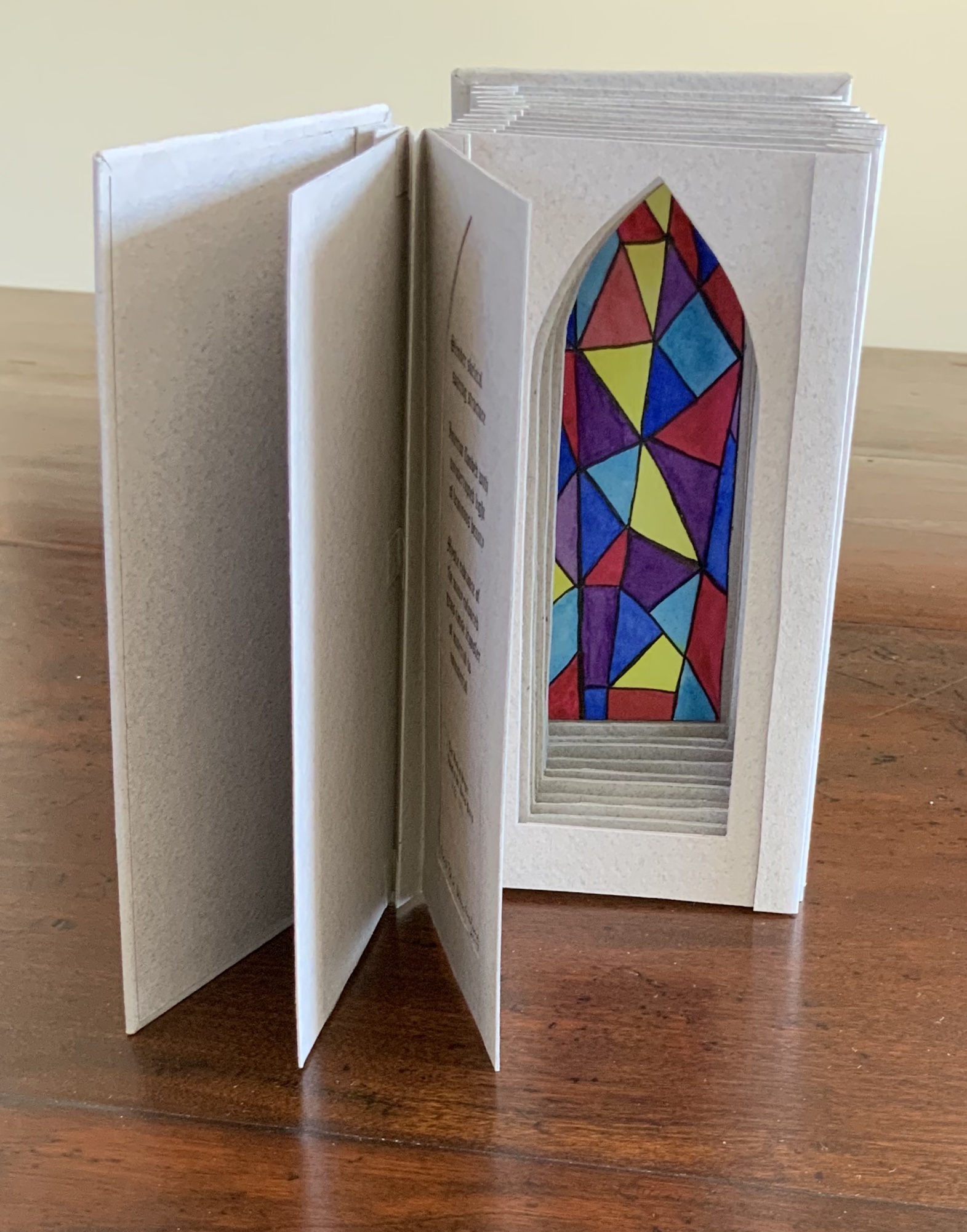

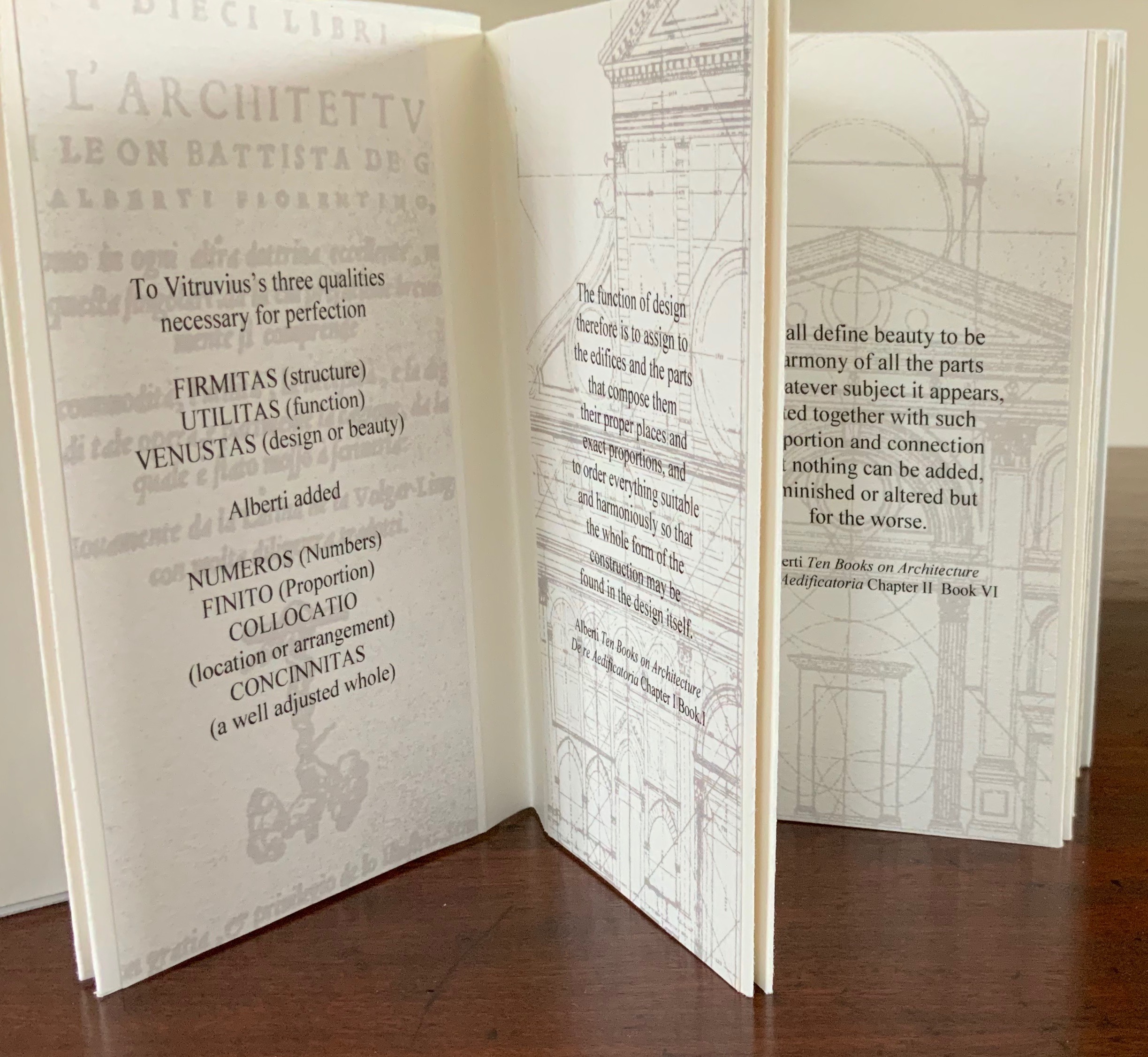

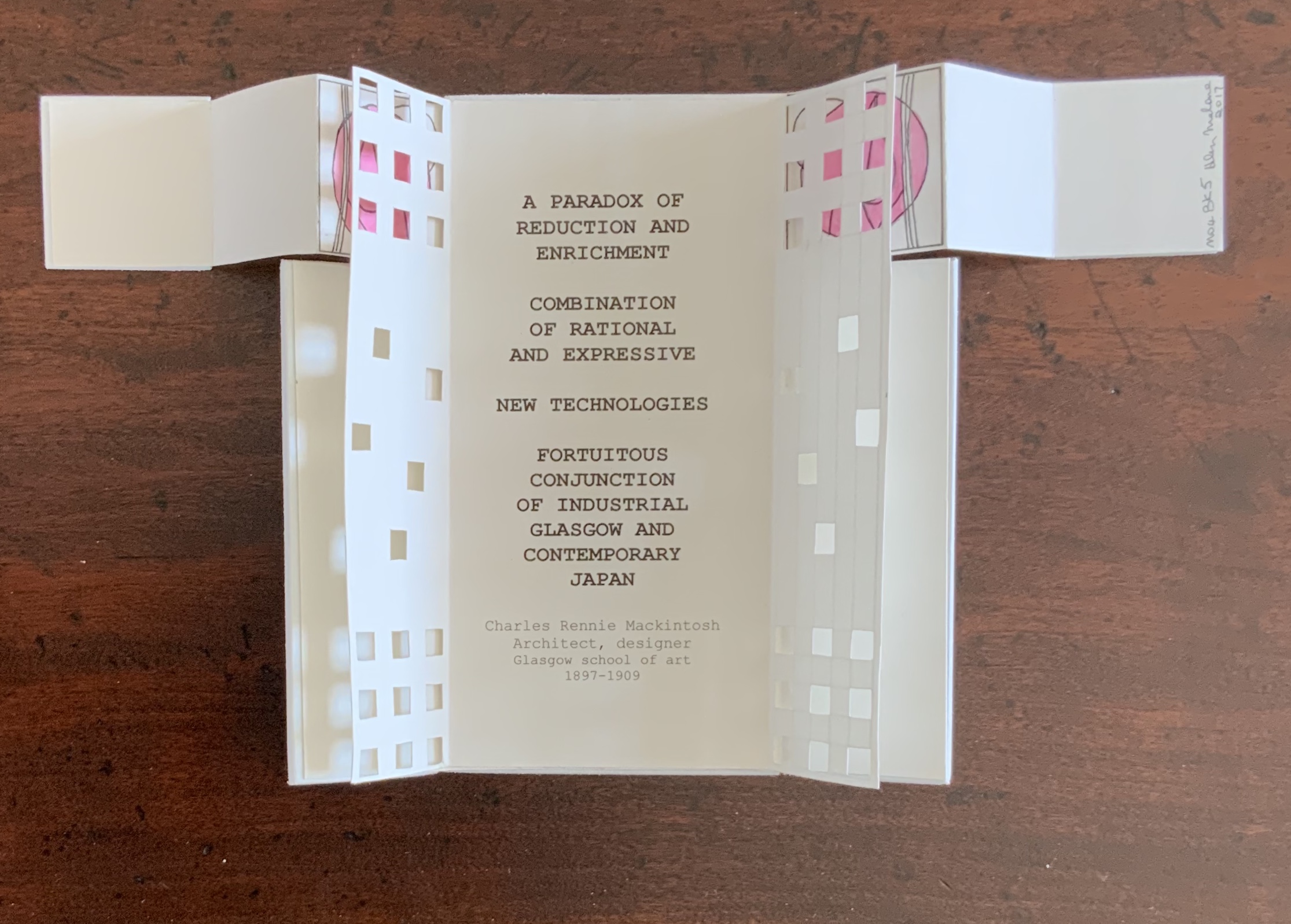

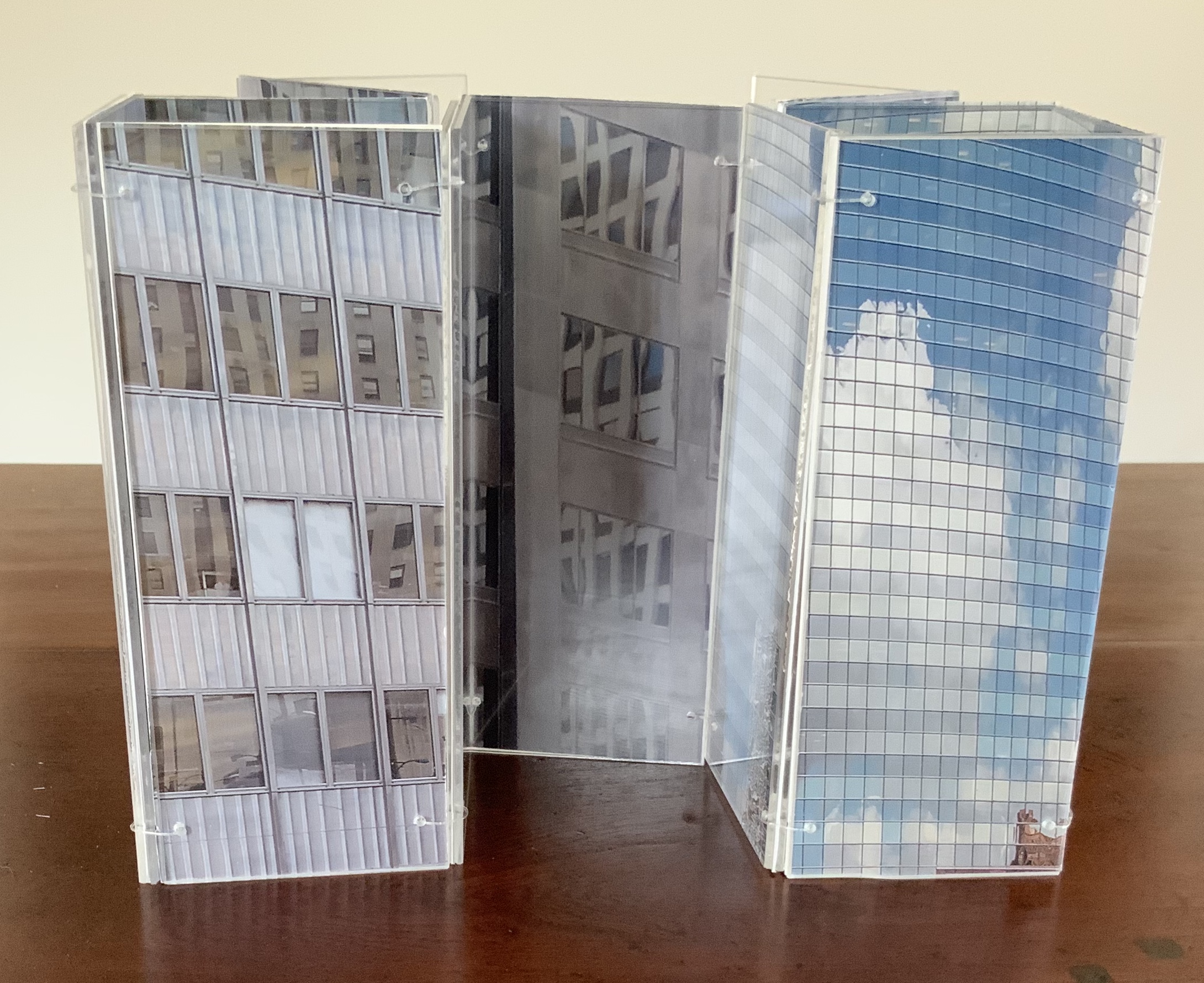

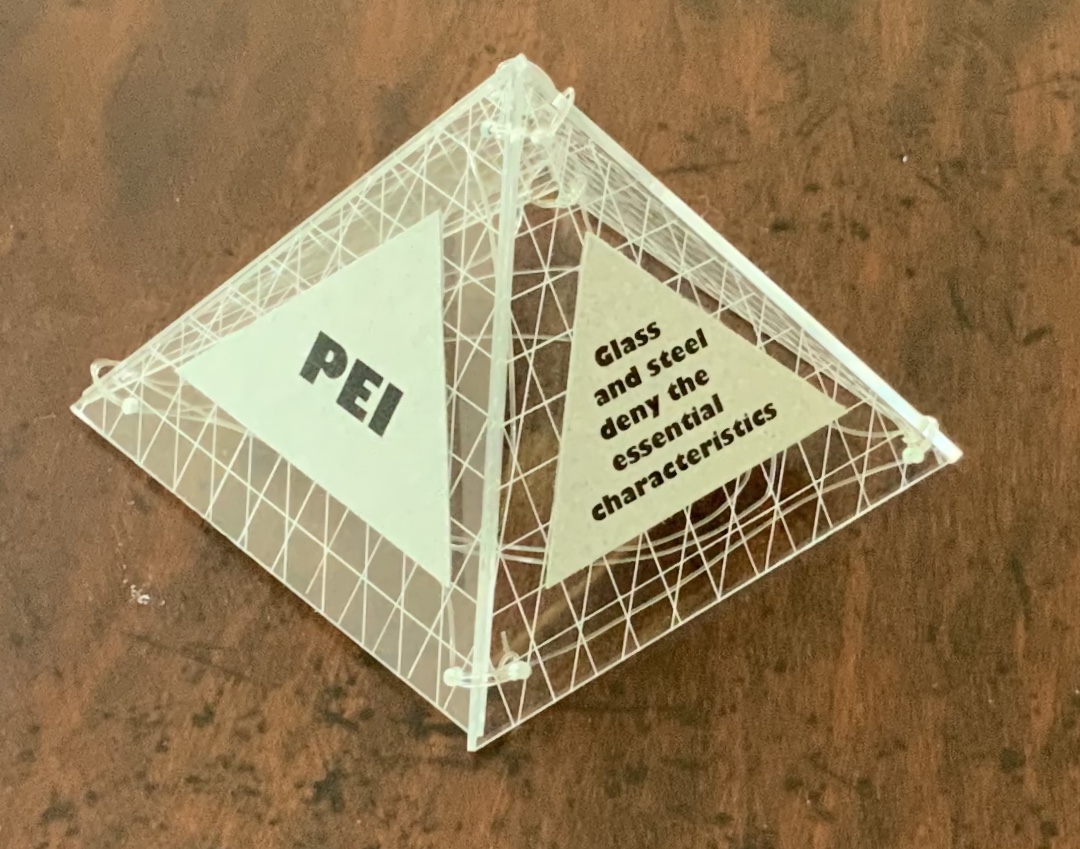

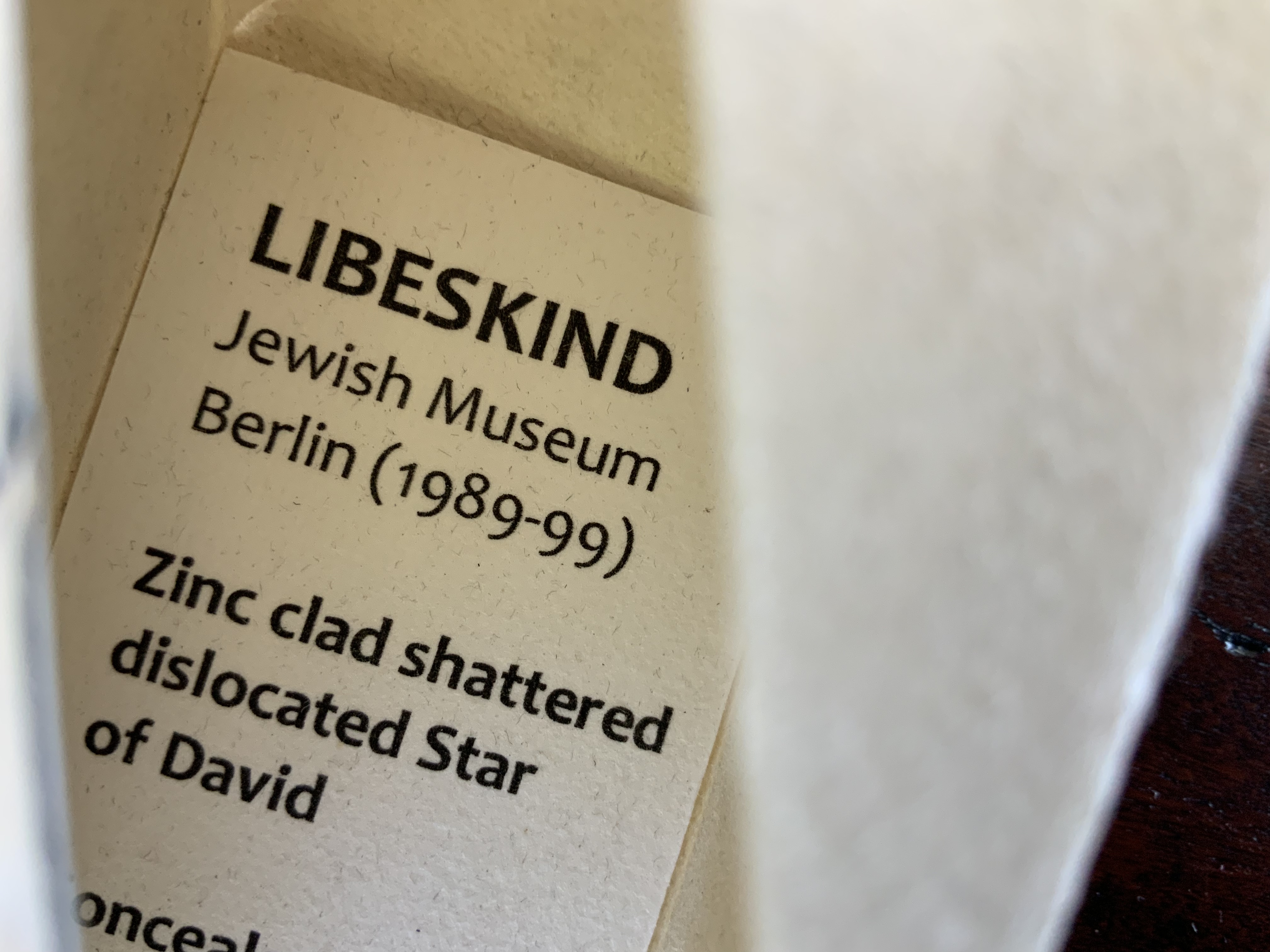

Helen Malone’s Ten Books of Architecture (2017) takes a broad historical and, most important, haptic view of architecture from Vitruvius to Hadid. Each of the ten books is a bookwork that models its architectural subject.

Ten Books of Architecture (2017)

Helen Malone

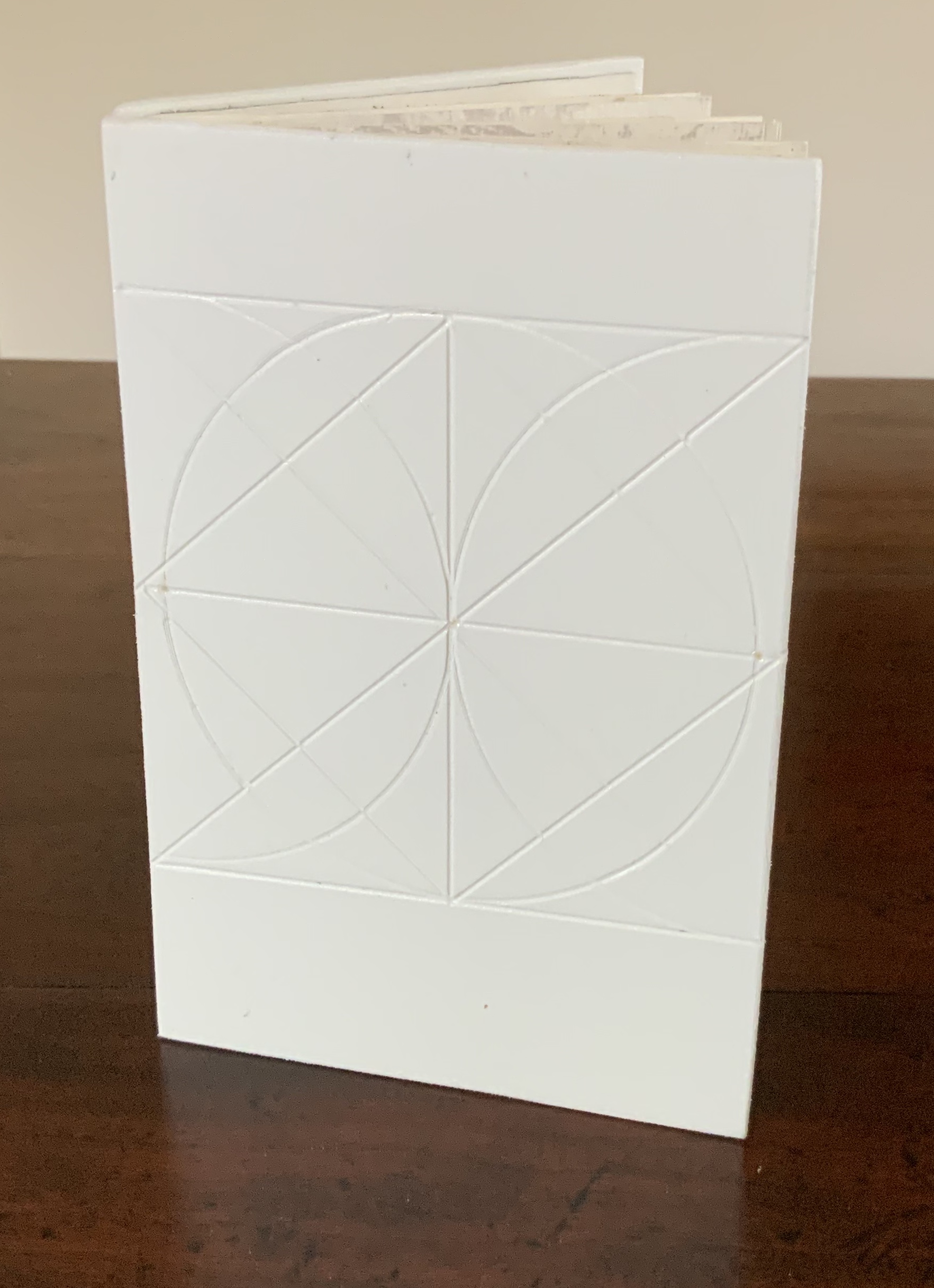

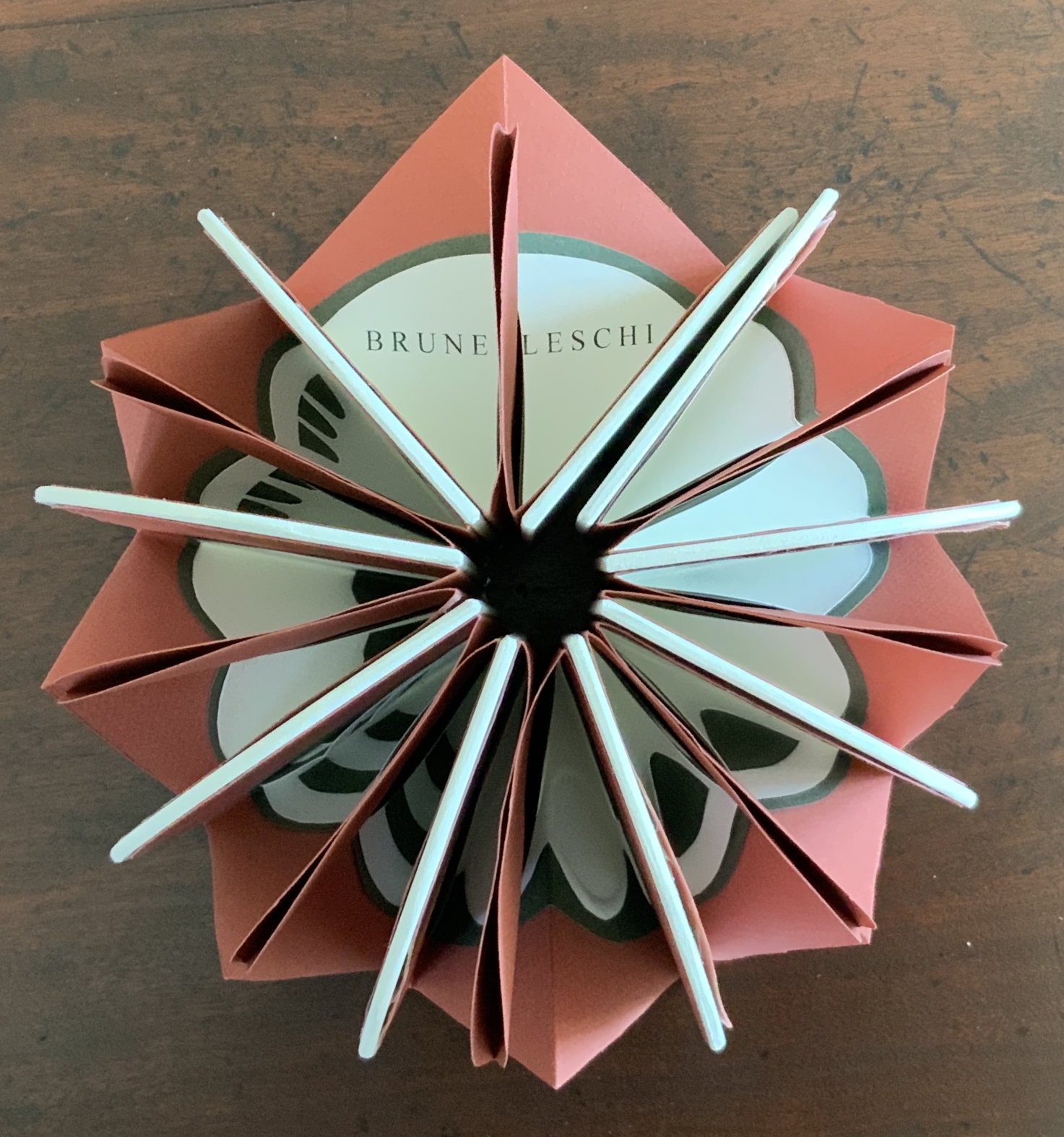

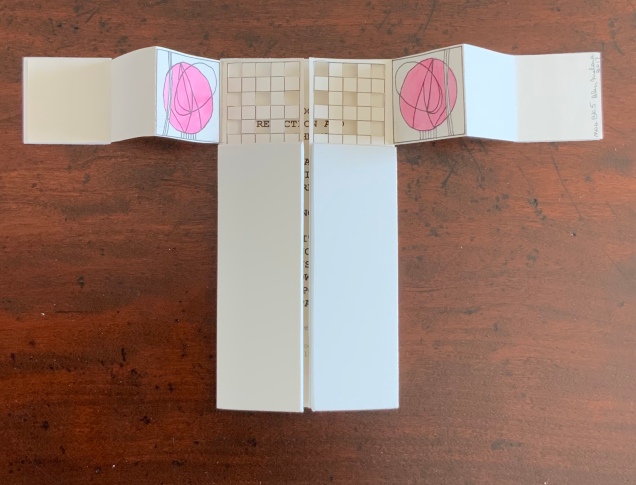

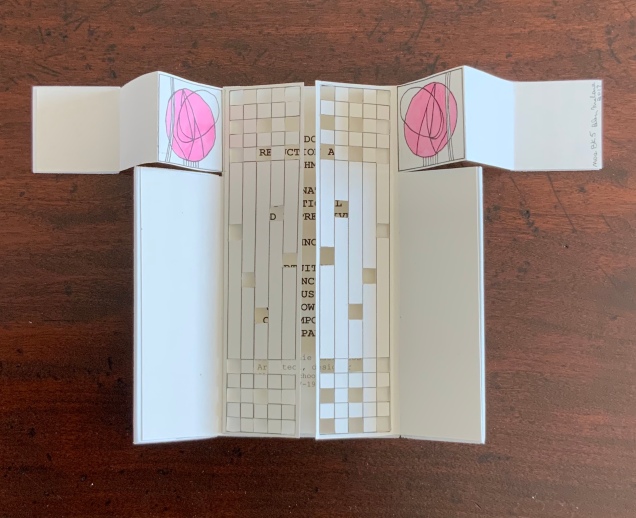

Proposition #8: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in folding.

At the end of the 20th century, architects like Peter Eisenman, Jeffrey Kipnis and Greg Lynn latched on to computer-aided design and Gilles Deleuze’s Le pli: Leibniz et le baroque (1988) / The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque (1993). This led to real constructions such as Eisenman’s Rebstock Park in Frankfurt as well as to the seminal books Folding in Architecture (1993), edited by Lynn, and Folding Architecture 92003) by Sophia Vyzoviti.

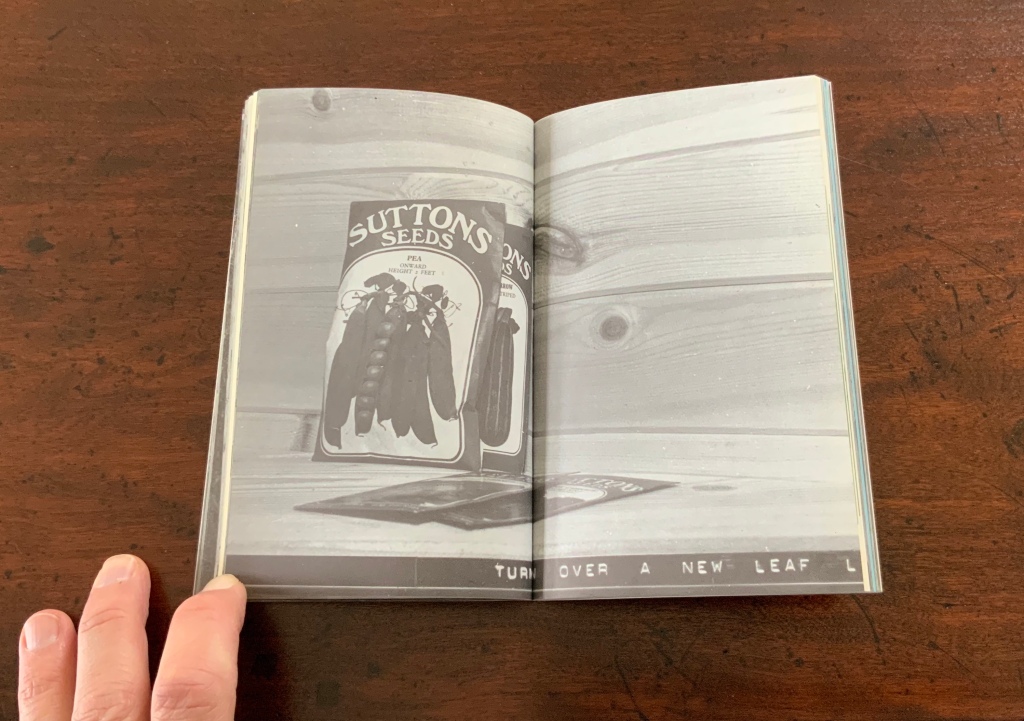

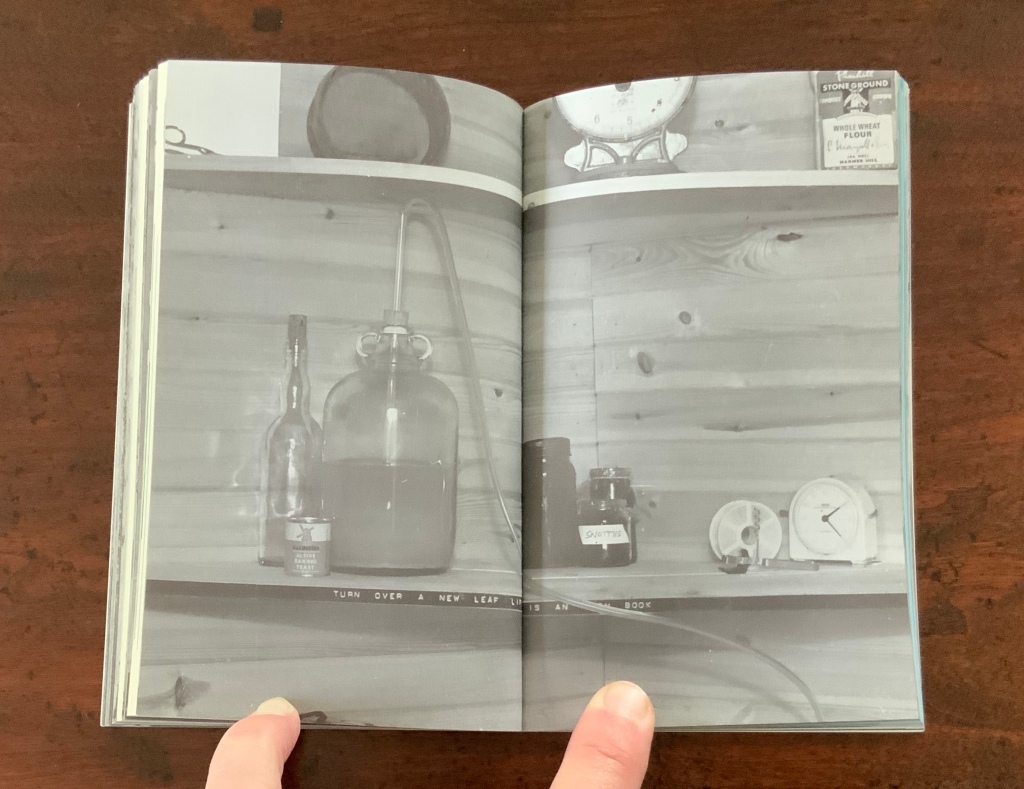

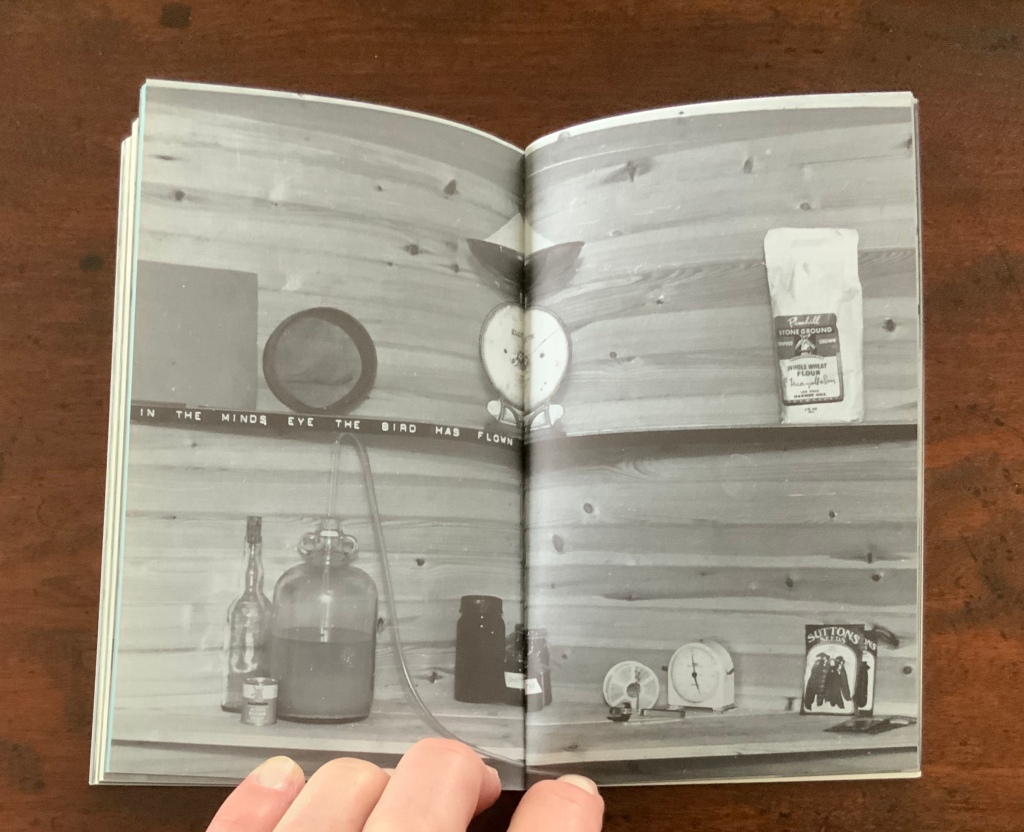

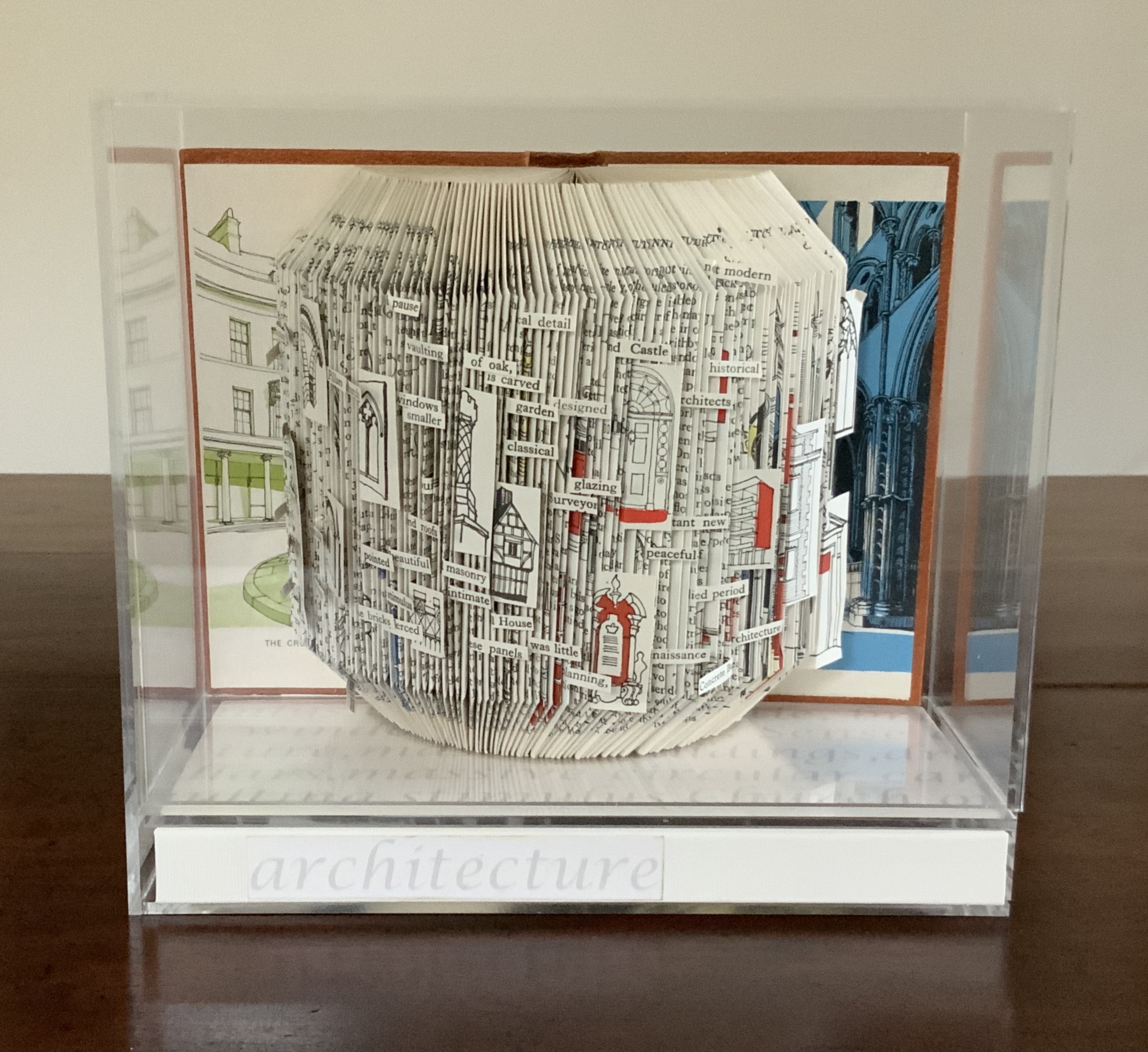

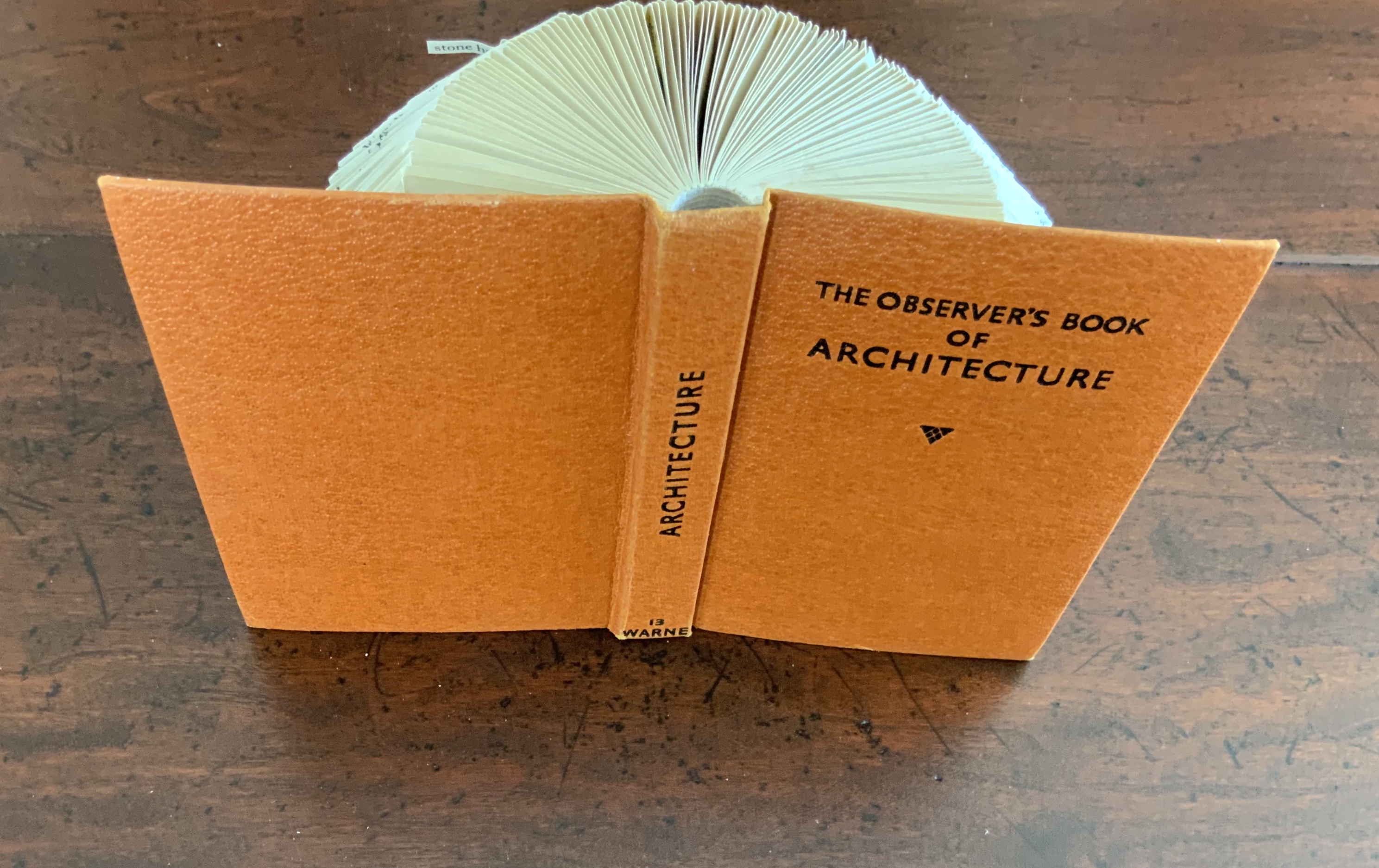

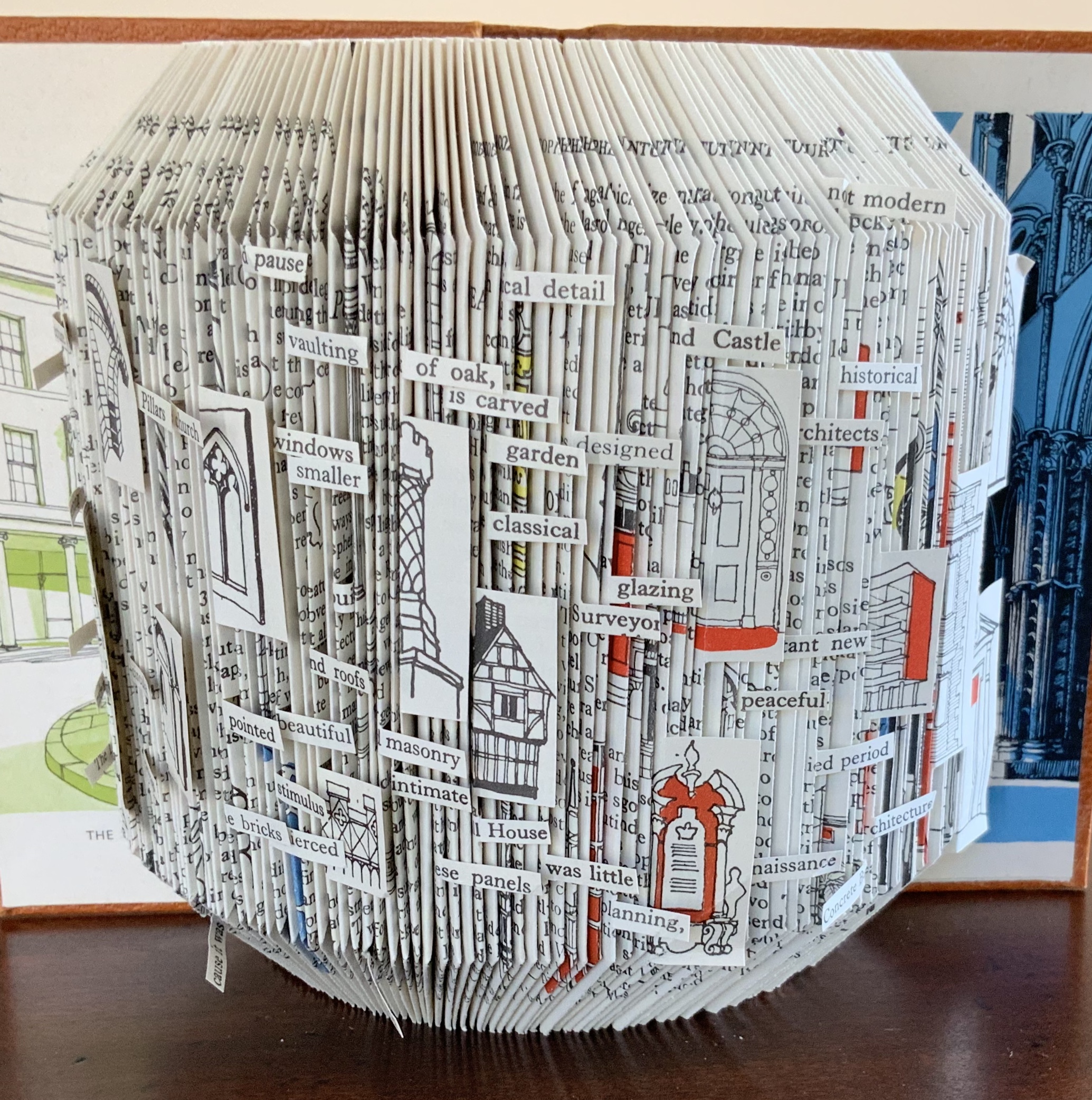

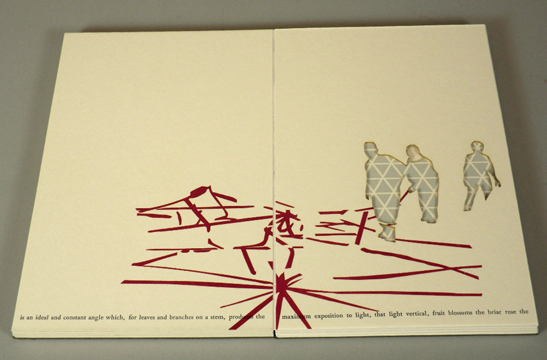

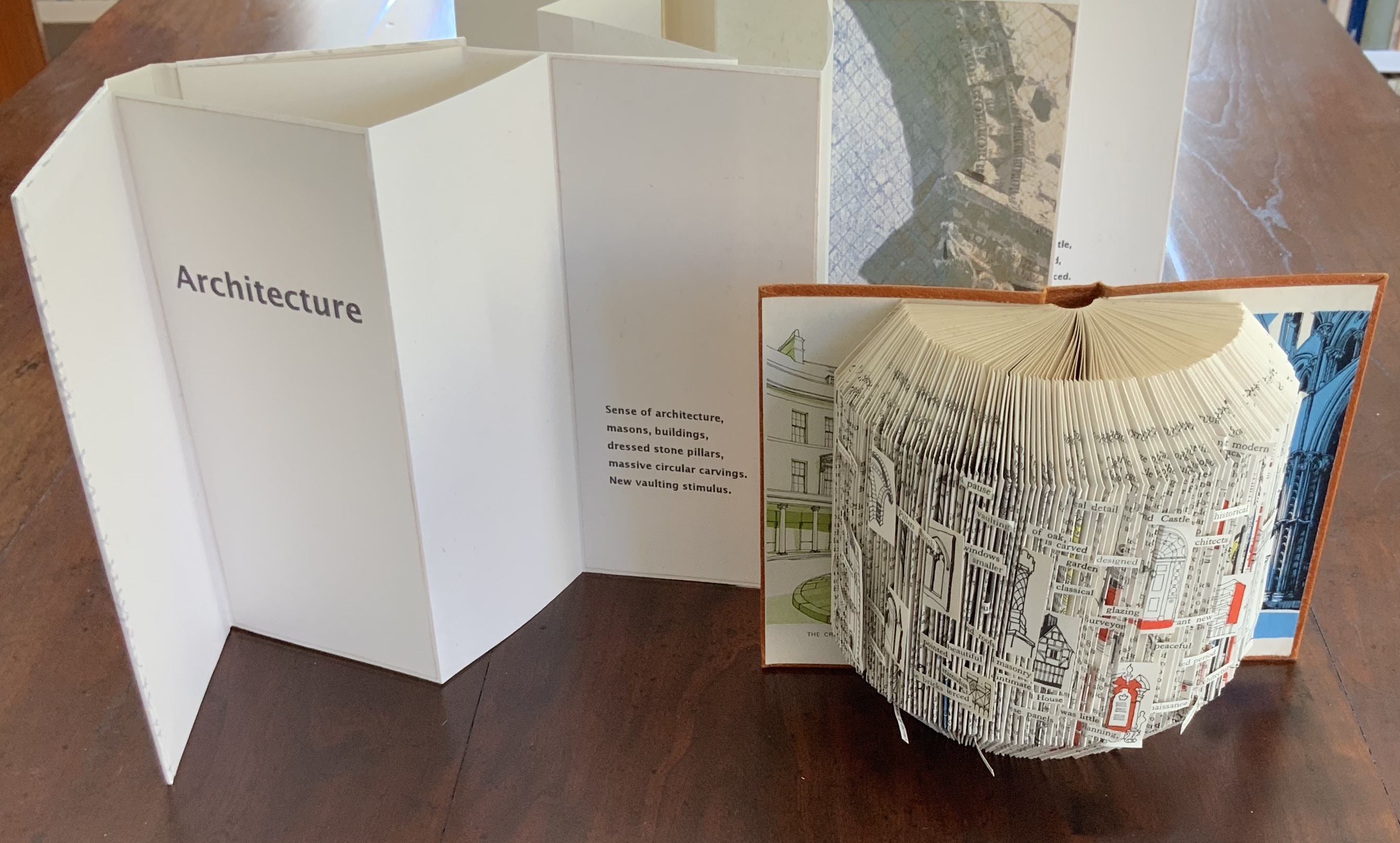

Folded book pages rarely generate a work that rises above mere craft. Heather Hunter’s Observer Series: Architecture (2009) achieves the necessary height. It combines the altered book with an accordion book that incorporates a found poem composed of the words excised and folded outwards from the folded pages of The Observer’s Book of Architecture.

Observer Series: Architecture (2009)

Heather Hunter

Proposition #9: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in light.

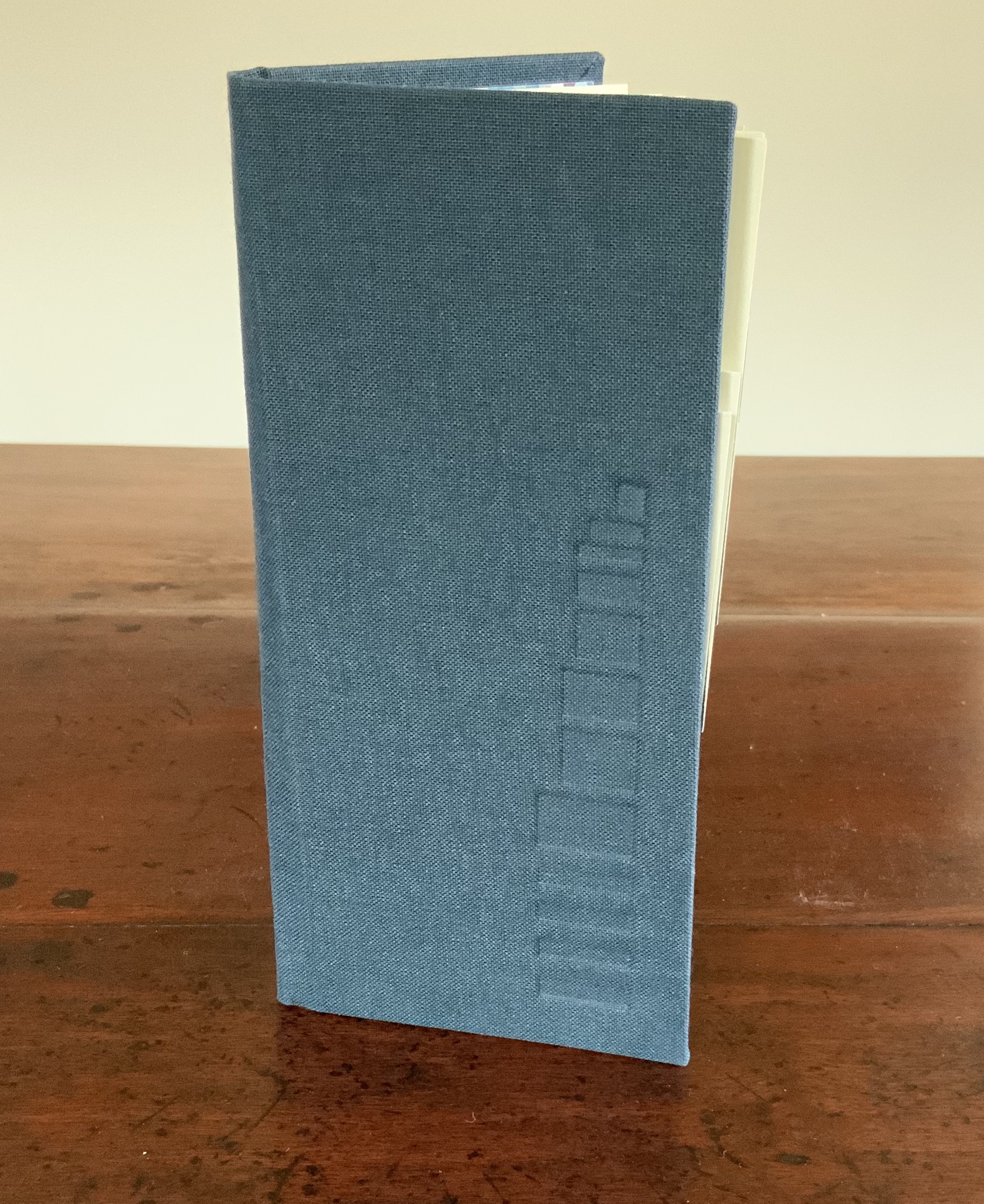

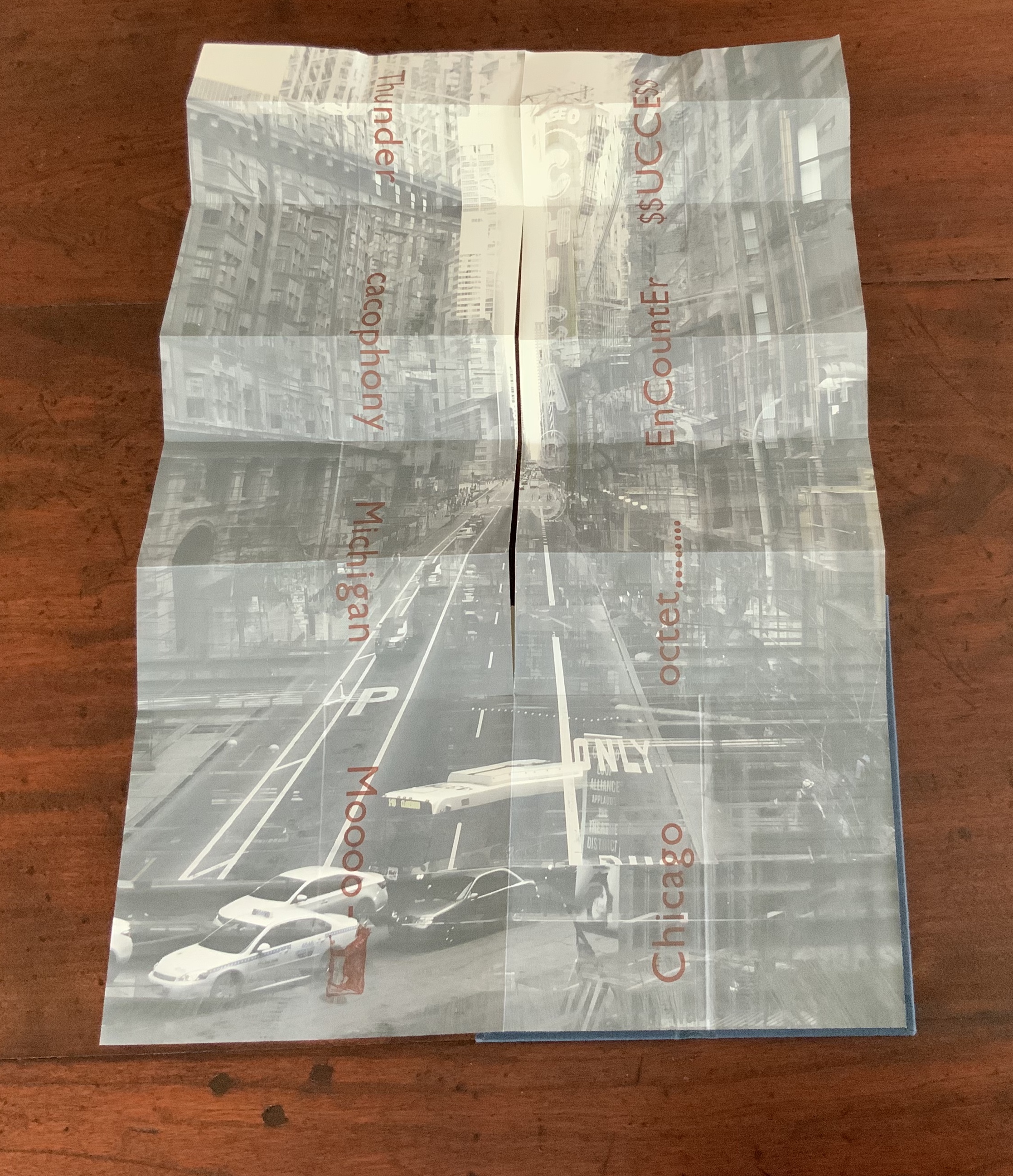

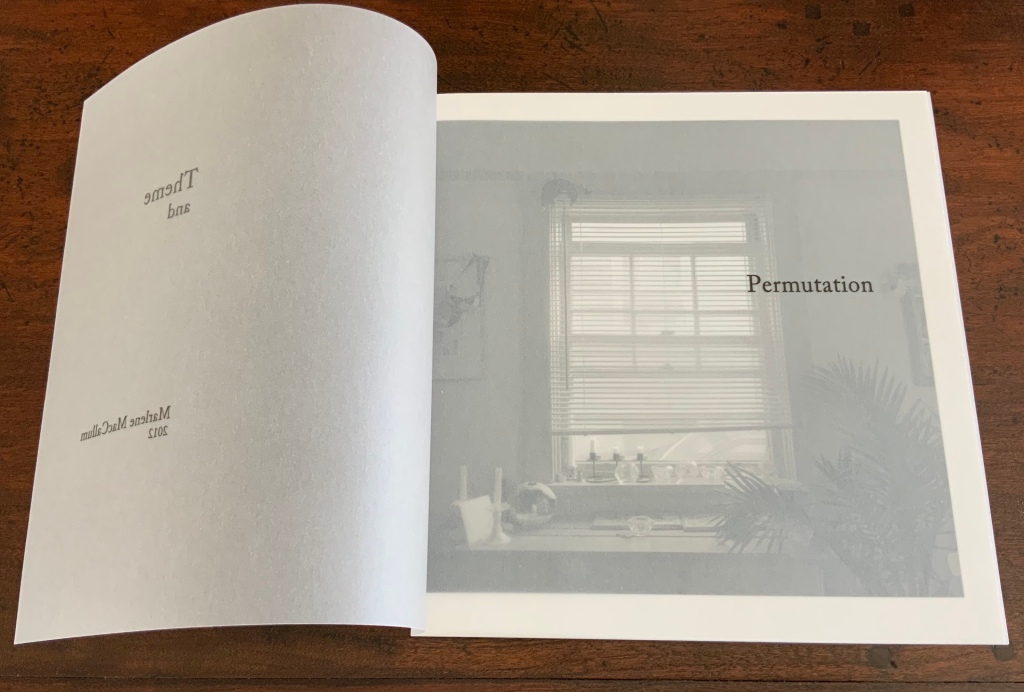

Marlene MacCallum’s Theme and Permutation (2012) is a response to the permutations and variations over time in five houses built to a common plan in Townsite area of Corner Brook, Newfoundland. MacCallum used digital tools to translate the original film source of eight different window images from the houses. A tritone image of a single Townsite window under translucent pages opens the book. As the pages turn, new window images appear and layer over each other, darkening up to the book’s mid-point. In the center spread, two text blocks appear speaking to the history, architectural permutations and economic shifts of the Townsite area. The tonality begins to lighten over the ensuing new combinations of window layers. A third text block of personal narrative is introduced, and a tritone image of one of the Townsite windows in its original condition concludes the work.

Theme and Permutation (2012)

Marlene MacCallum

Proposition #10: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in perspective.

Cees Nagelkerke’s Piranesian Window (1996) resides in the Vedute Foundation’s collection of “spatial manuscripts”, invited works that must conform to the dimensions of the Gutenberg Bible. Piranesian Window‘s form and title capture multiple meanings of vedute (“views”). Views are things seen — which this spatial manuscript is. Views are prospects from which to see — which a window offers. Views are perspectives — for which Giambattista Piranesi’s etchings are famous. Views are thoughts held — which “Piranesian” implies (the work’s title could be that of a manuscript on art history and philosophy). Piranesi’s mid-eighteenth century etchings Vedute di Roma (“Views of Rome”) and Carceri d’invenzione (“Imaginary Prisons”) are the obvious sources of inspiration, but Nagelkerke provides an interview describing the dream source of the work:

– … Please, continue relating your dream …

– I wandered through vast ruins … along wrecked bridges … feeling remarkably at ease.

– How did you find the window in this windowless world?

– When a cool breeze wafted inside, I suddenly saw it. It showed a landscape, within the distance a city. There was complete tranquillity and harmony there, like in a painting by Piero della Francesca … I stood there for some considerable time and I became increasingly saddened, because I discovered that I was looking at something that had vanished forever.

– But how did you manage to take the window?

– I wanted to touch it … as a result, I immediately fell down. The gap left in the wall closed by itself … I picked it up and continued on my way, meeting people who spoke to me saying that I should leave the Carceri. I was taken to a gateway. No one looked at, or said anything about, the window… In the square where I found myself, there was an intense, chaotic commotion. The window still reflected something of the vast space I had left. The exterior showed traces of the wall in which it had been mounted. I looked through it and saw everyday life …

Piranesian Window (1996)

Cees Nagelkerke

Proposition #11: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in archaeology.

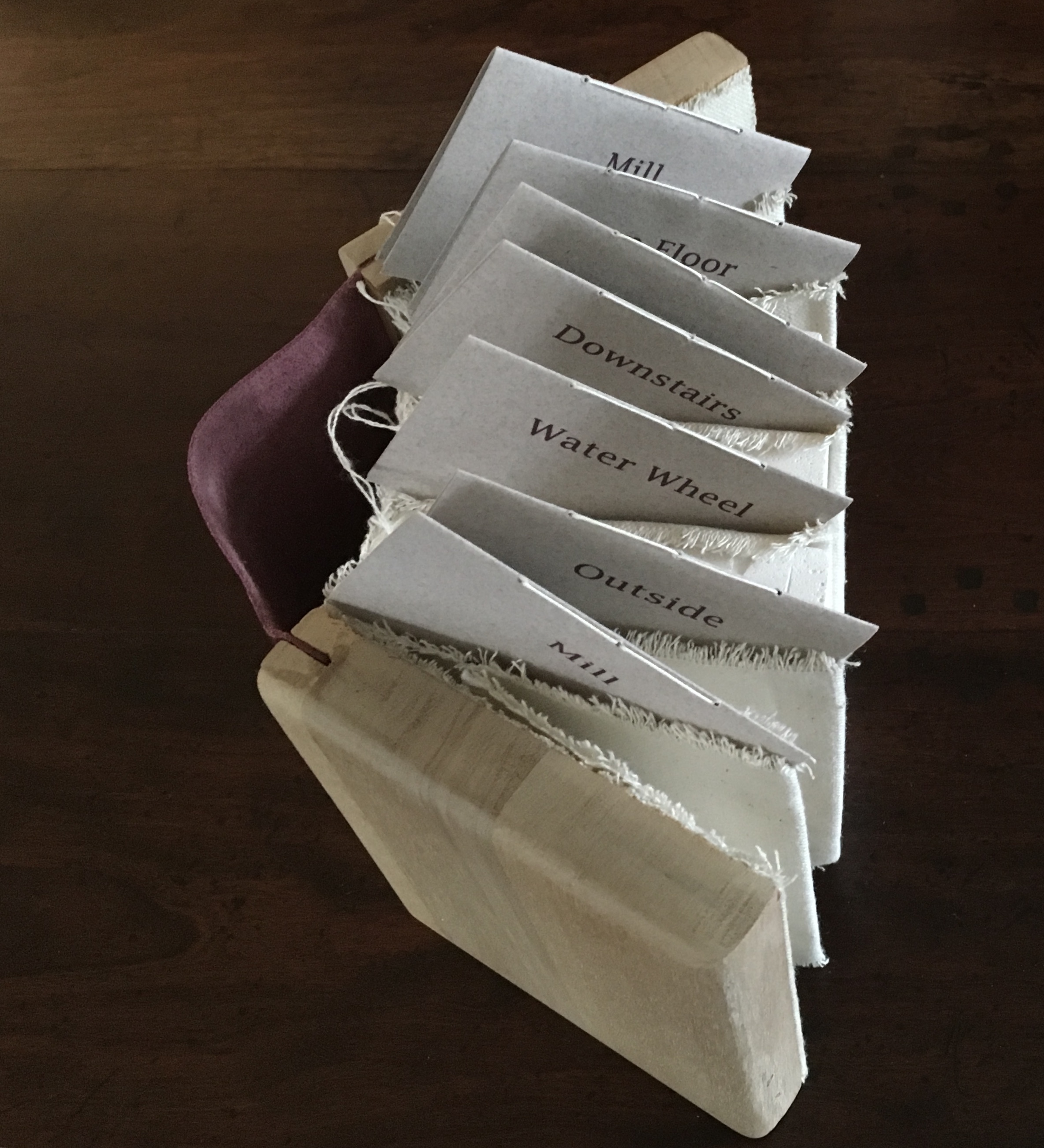

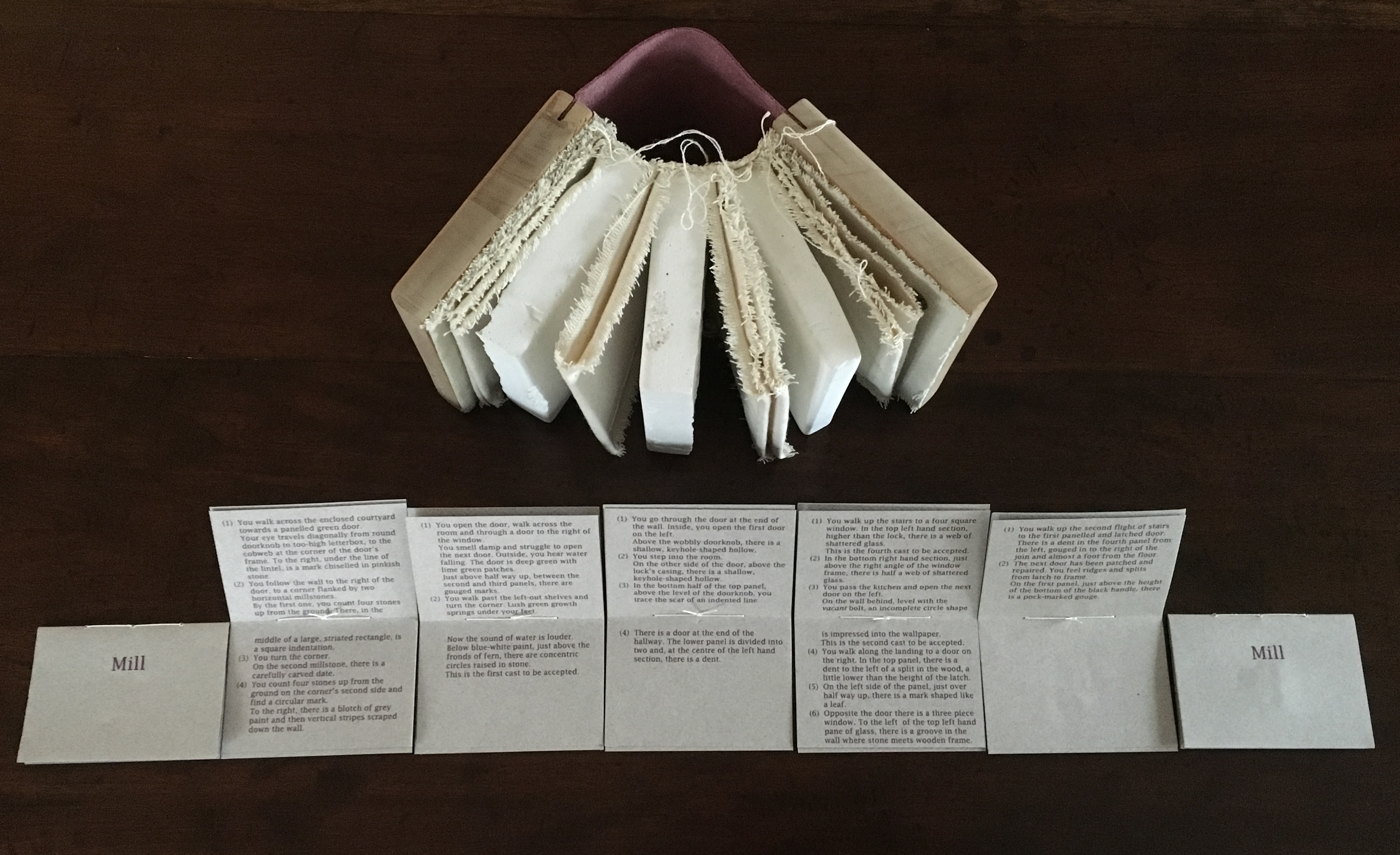

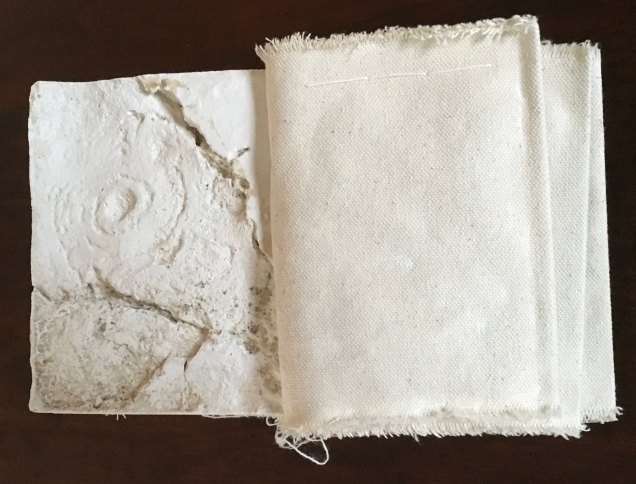

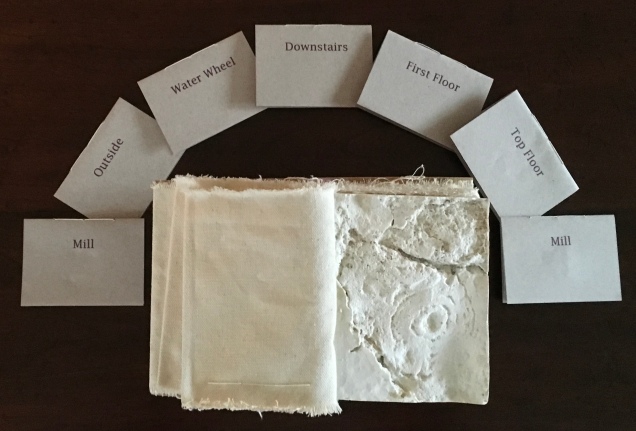

Mill: A journey around Cromford Mill, Derbyshire (2006) by Salt + Shaw (Paul Salt and Susan Shaw) is the result of the artists’ exploration of Cromford Mill in Derbyshire, the first water-powered, cotton-spinning mill developed by Richard Arkwright in 1771. Bound in a cover of recycled wooden library shelves, three plaster cast blocks and seven calico pocket pages containing hidden texts imply the hidden archaeological history to be found. The forensic-like casts are taken from interior surfaces, and the texts walk the reader step by step through each area of the mill.

Proposition #12: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in assemblage and collage.

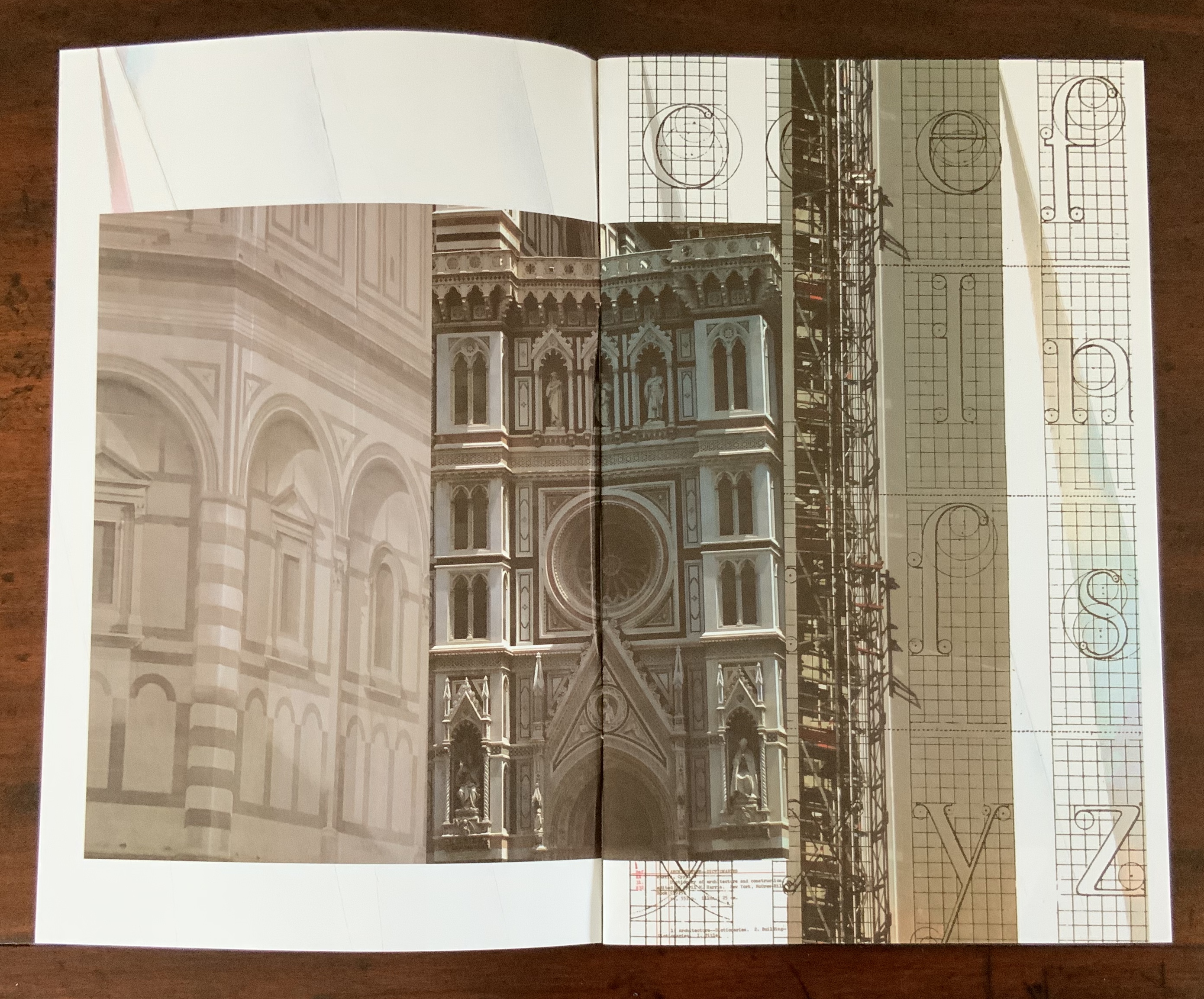

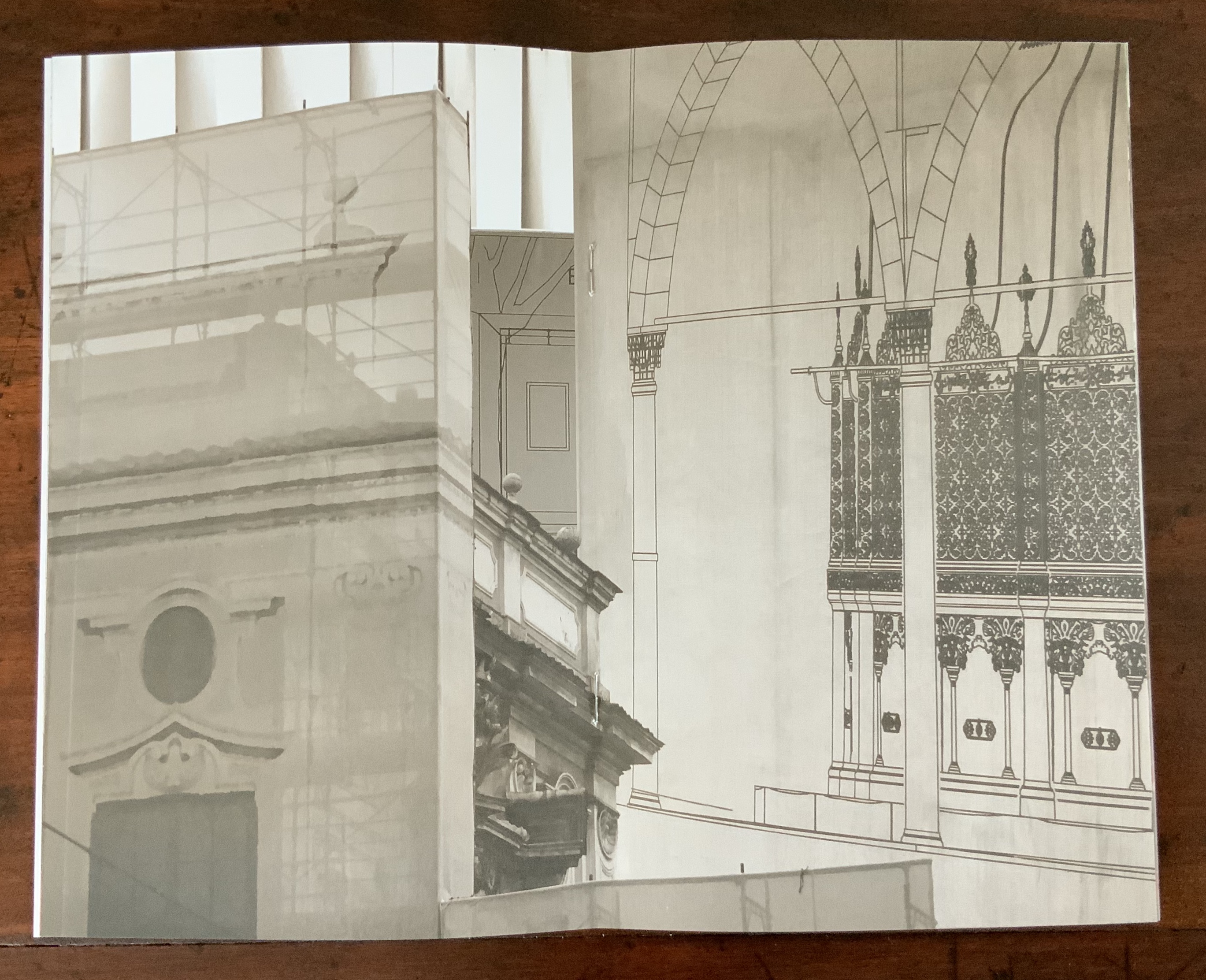

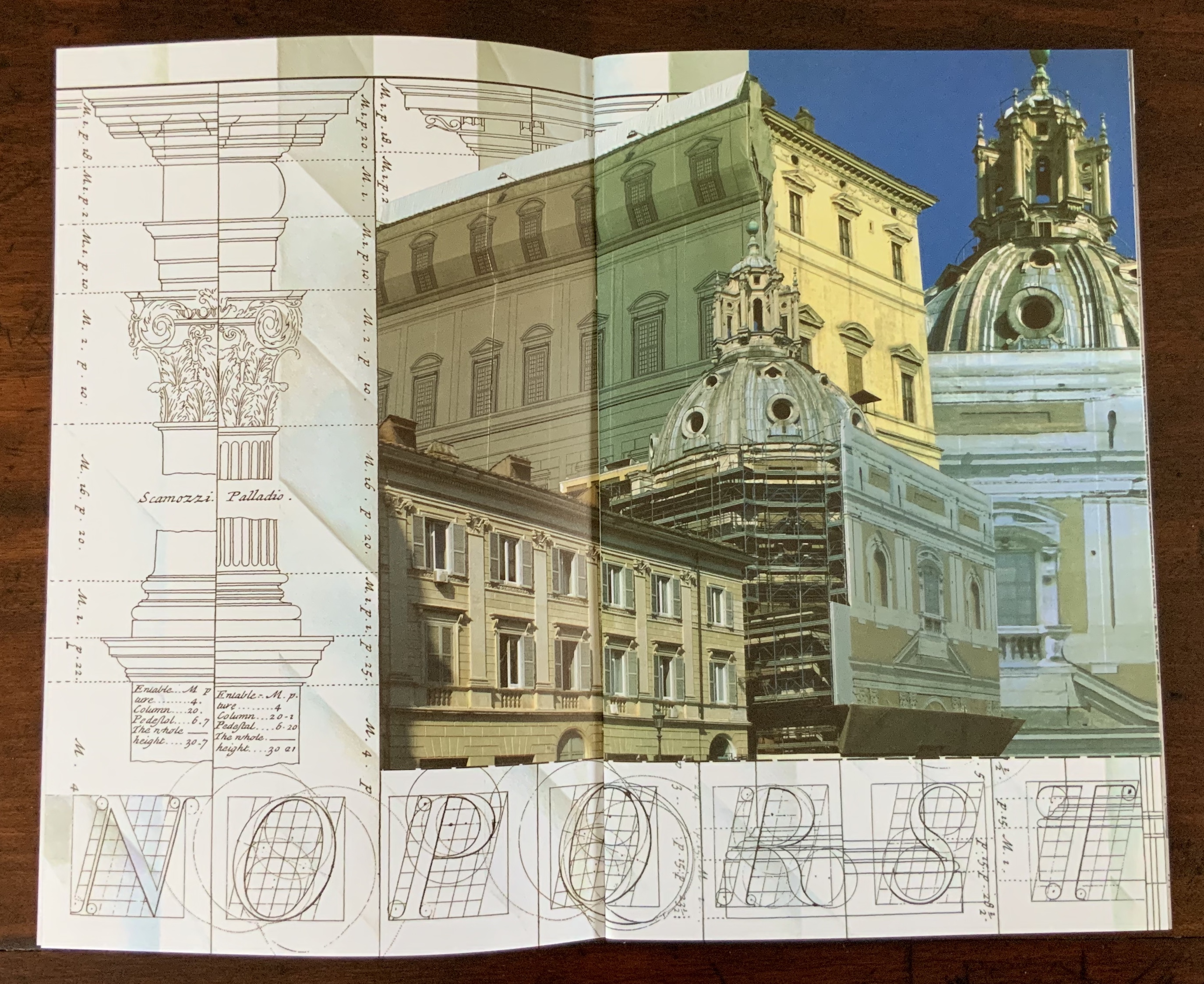

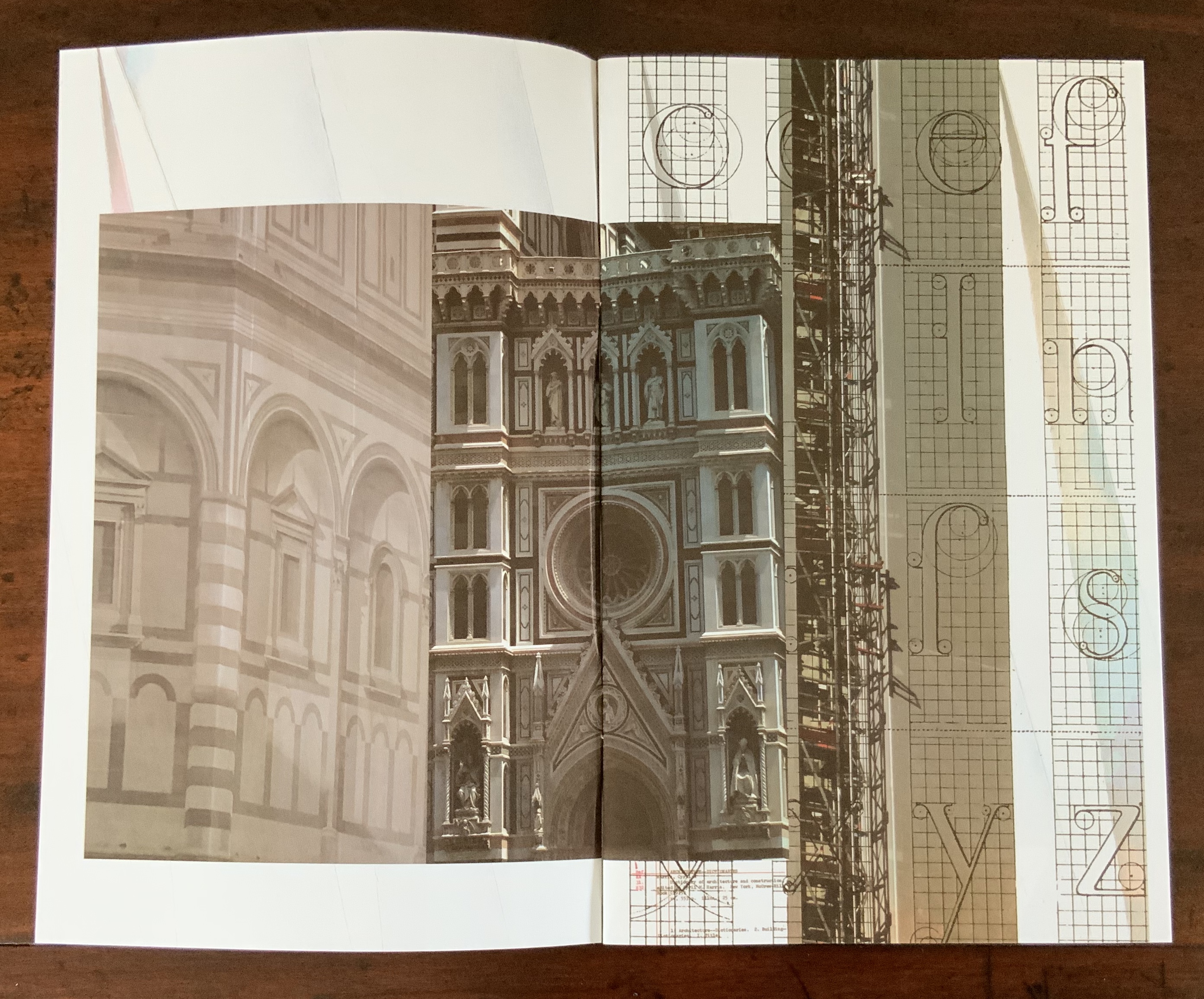

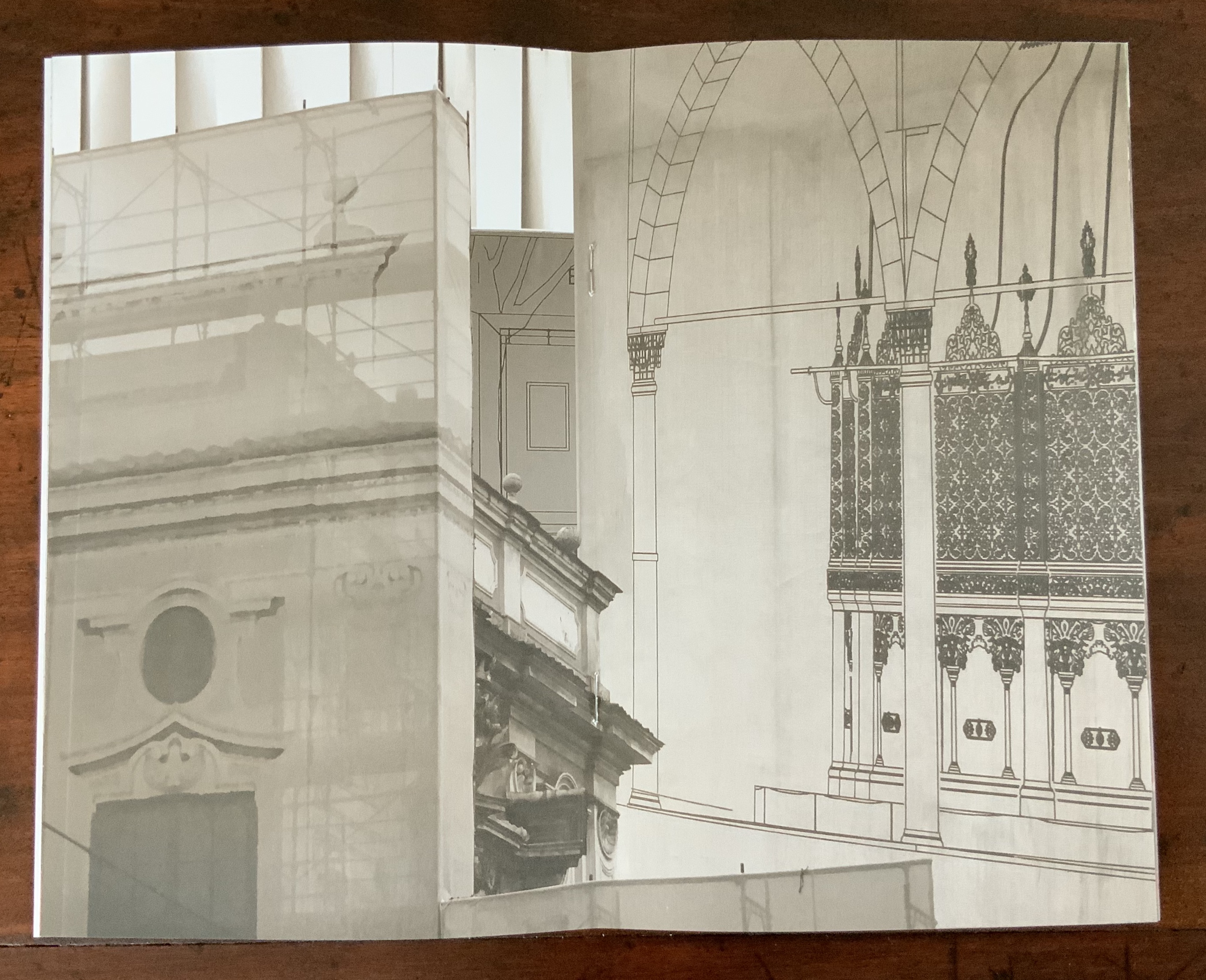

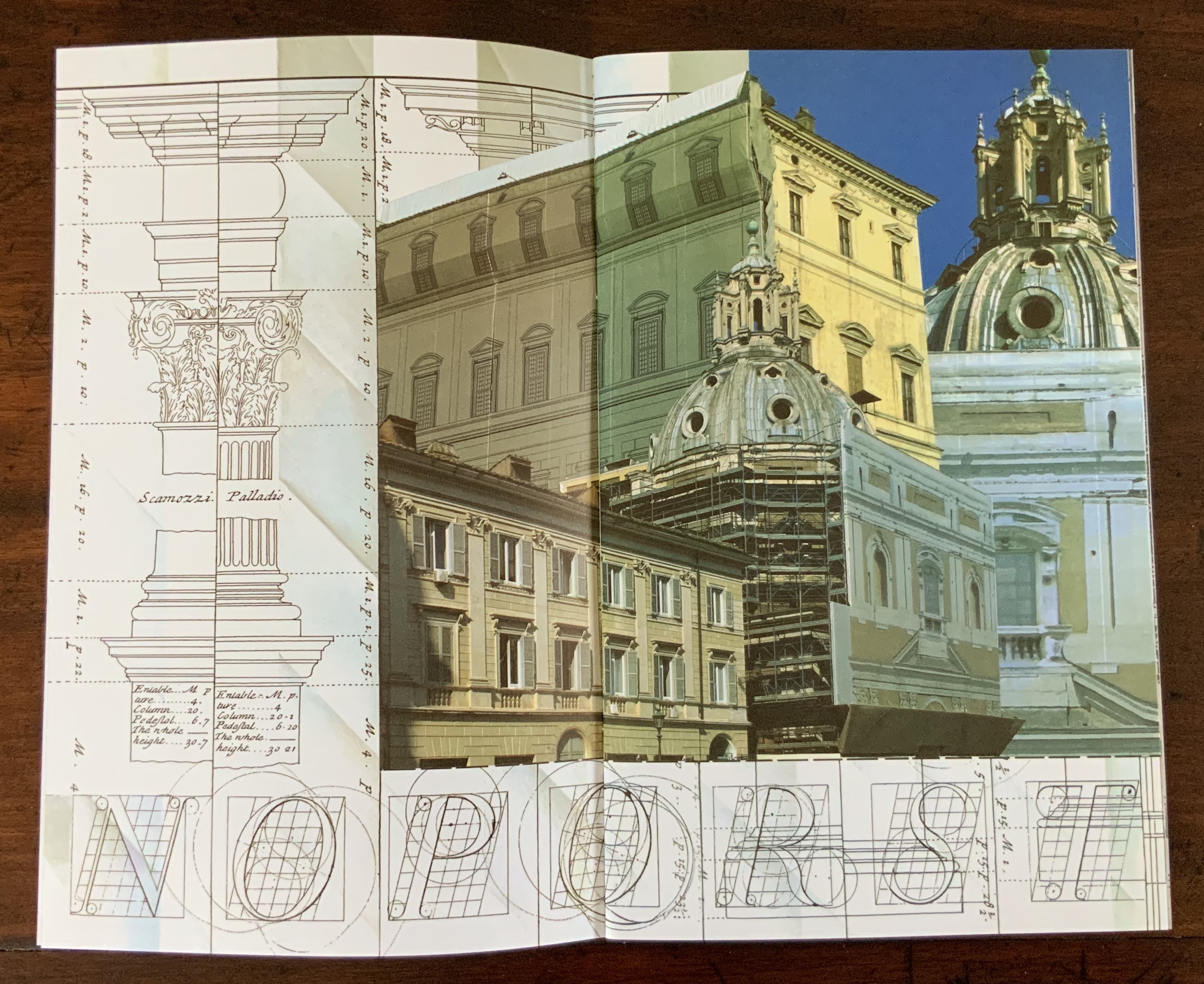

Based on an architectural installation at the Minnesota College for Art and Design and drawing on her photos of Ayvalik, Amsterdam, Florence, Istanbul, New York City, Rome, San Diego and Venice, Karen Wirth’s Paper Architecture (2017) certainly prompts a revisit to MoMA’s “Cut ’n’ Paste: From Architectural Assemblage to Collage City“, 10 July 2013 – 5 January 2015, to prove this proposition.

Paper Architecture (2017)

Karen Wirth

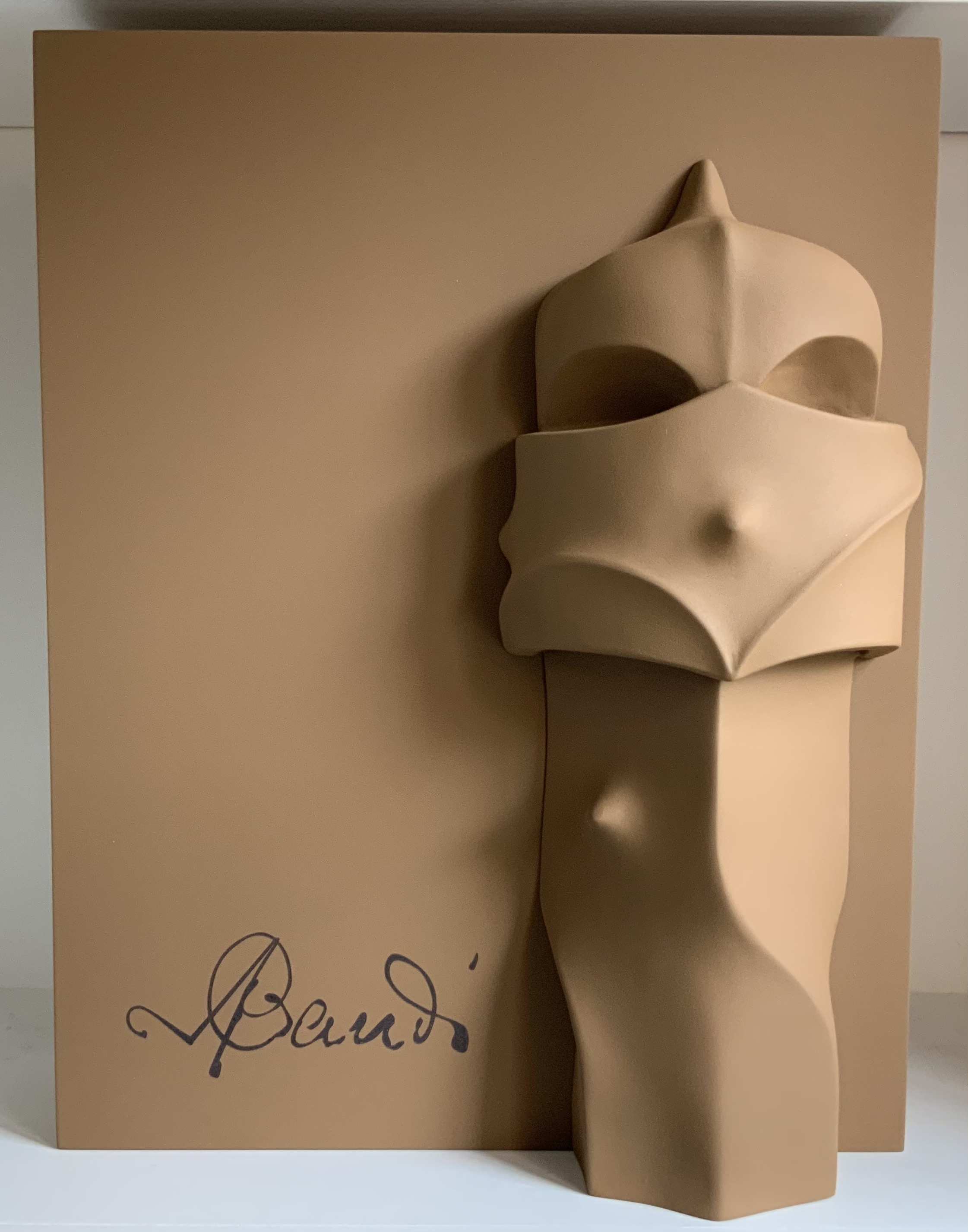

Proposition #13: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in luxe.

Early theorists, critics and artists of book art expended great effort to exclude livres d’artiste and deluxe productions from the definition of a form of art that struggled to find a name: artist’s book, artists’ books, bookworks, book art, etc. The spectrum from objects of conspicuous consumption to democratic multiples characterizes both architecture and book art. Antoni Gaudí’s architectural efforts easily span that spectrum — from his Casa Milà to his tiles found underfoot in Barcelona’s Passeig de Gràcia. Under the guidance of Juan José Lahuerta (chief curator at the National Museum of Art of Catalonia), the publisher Artika produced Gaudí Up Close (2020), enclosed in a wooden case with marble sculpture finished in paint, cement powder and anti-graffiti varnishes and lined with Naturlinnen fabric.

Gaudí Up Close (2020)

Published by Artika.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Proposition #14: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in the memorial.

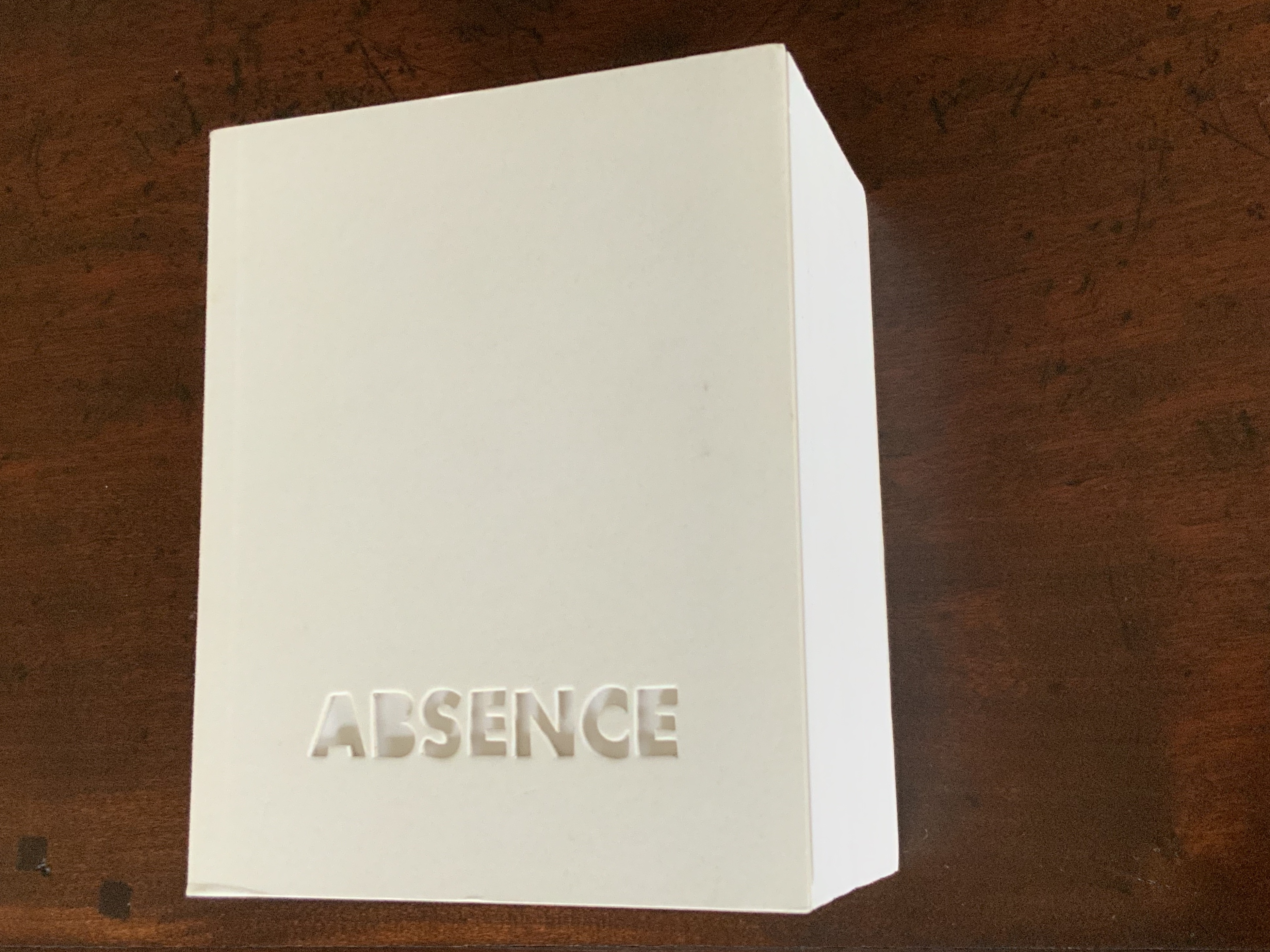

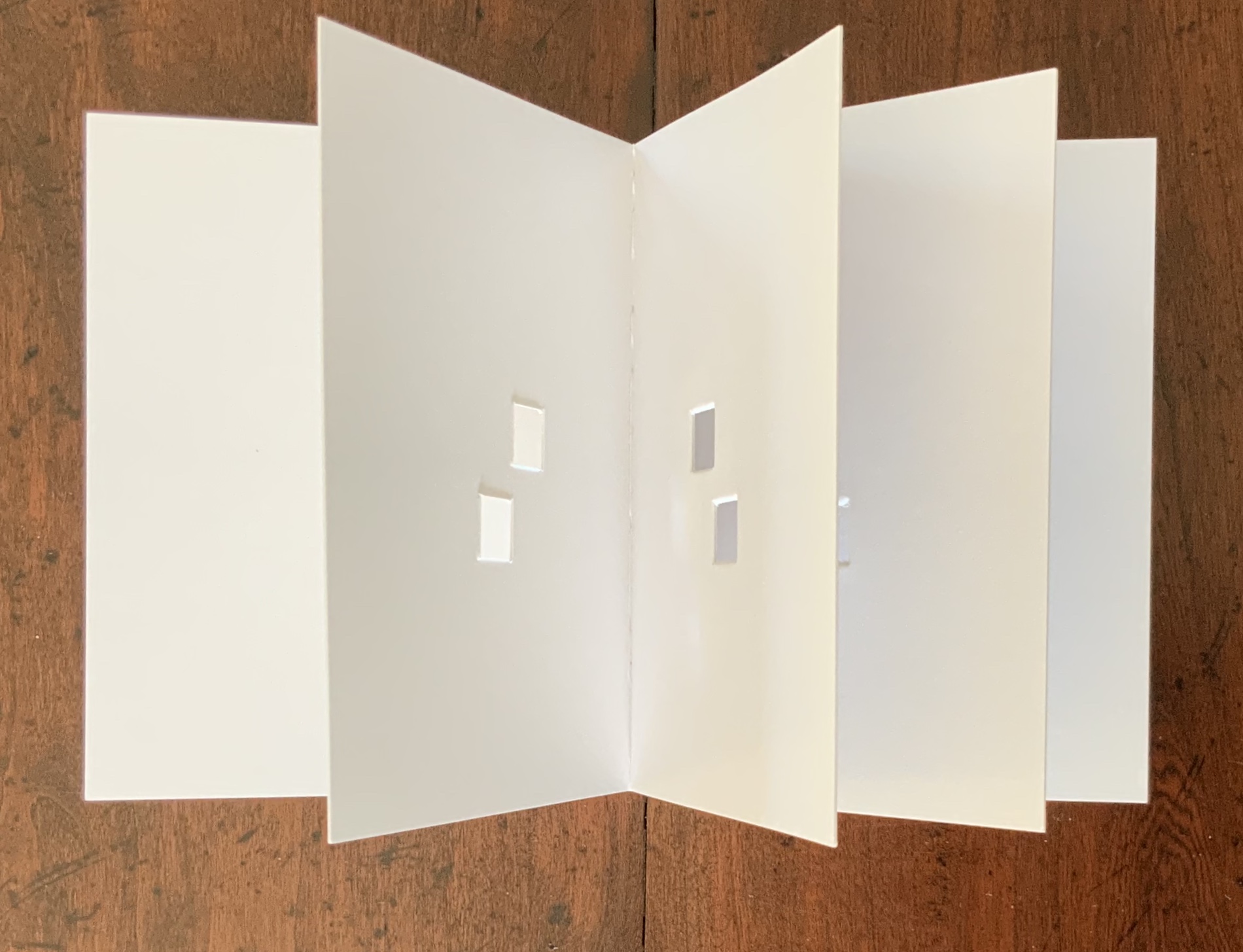

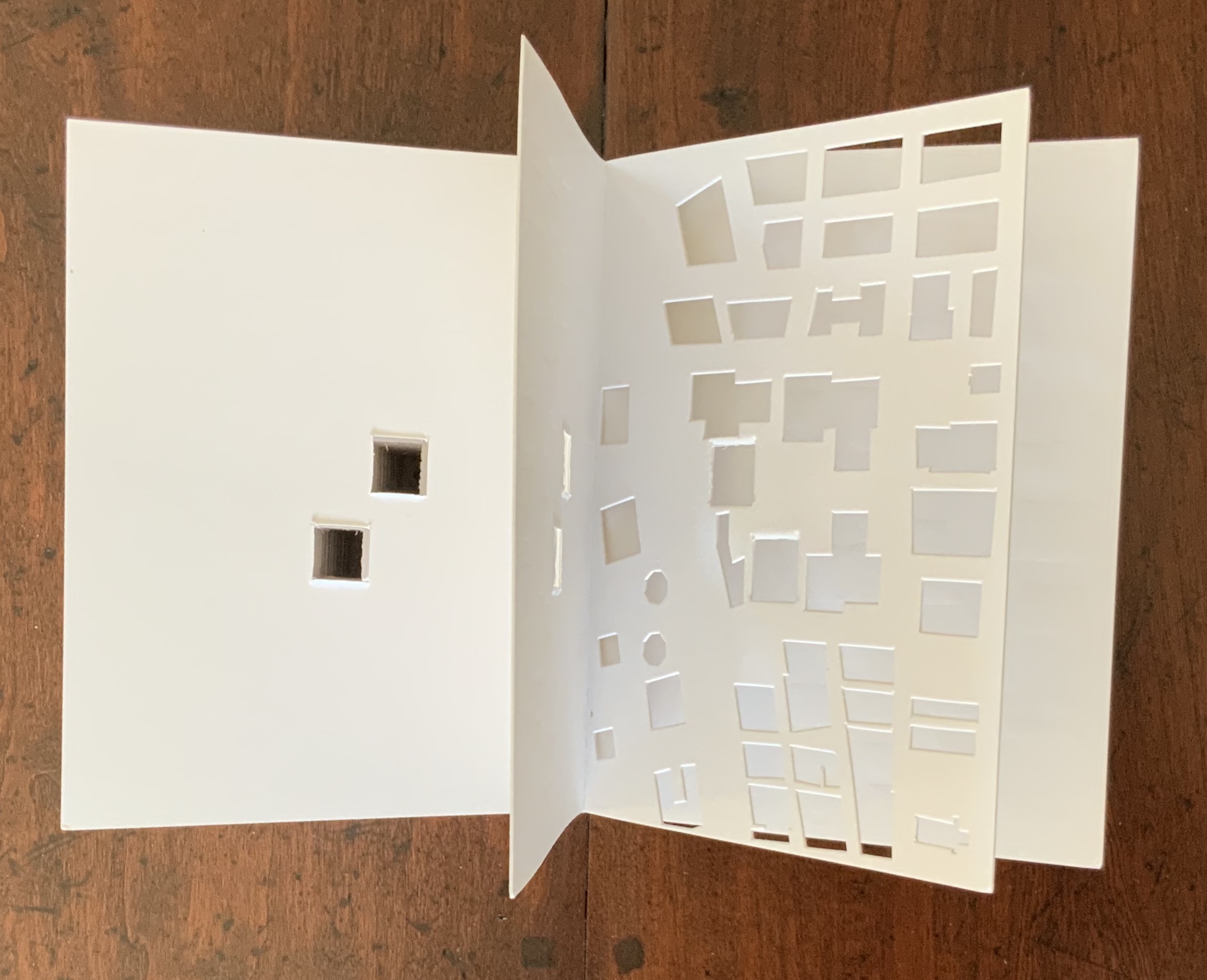

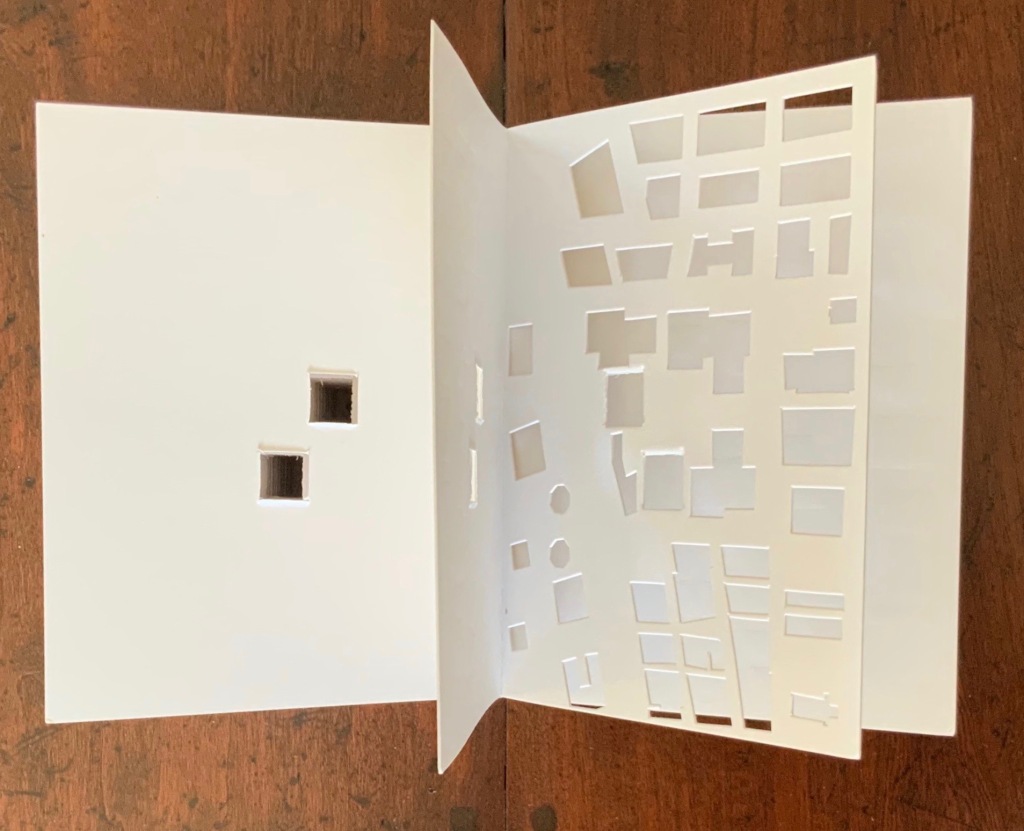

As you turn the corner into Judenplatz in Vienna, Rachel Whiteread’s great cube appears showing only the fore edge of book after book. As you hold J. Meejin Yoon’s small white brick of paper and turn its thick pages, a small pinhole appears on the page. Then two larger square holes emerge, one of which falls over the pinhole. Page after page, the two square holes repeat, creating two small dark wells in the field of white, until on the last page they take their place in the cut-out schematic footprint of the city blocks and buildings surrounding the Twin Towers. Whiteread’s Nameless Library (2000) and Yoon’s Absence (2004) surely underscore this proposition of memorial.

Nameless Library (2000)

Rachel Whiteread

Photo: Books On Books.

Absence (2004)

© J. Meejin Yoon

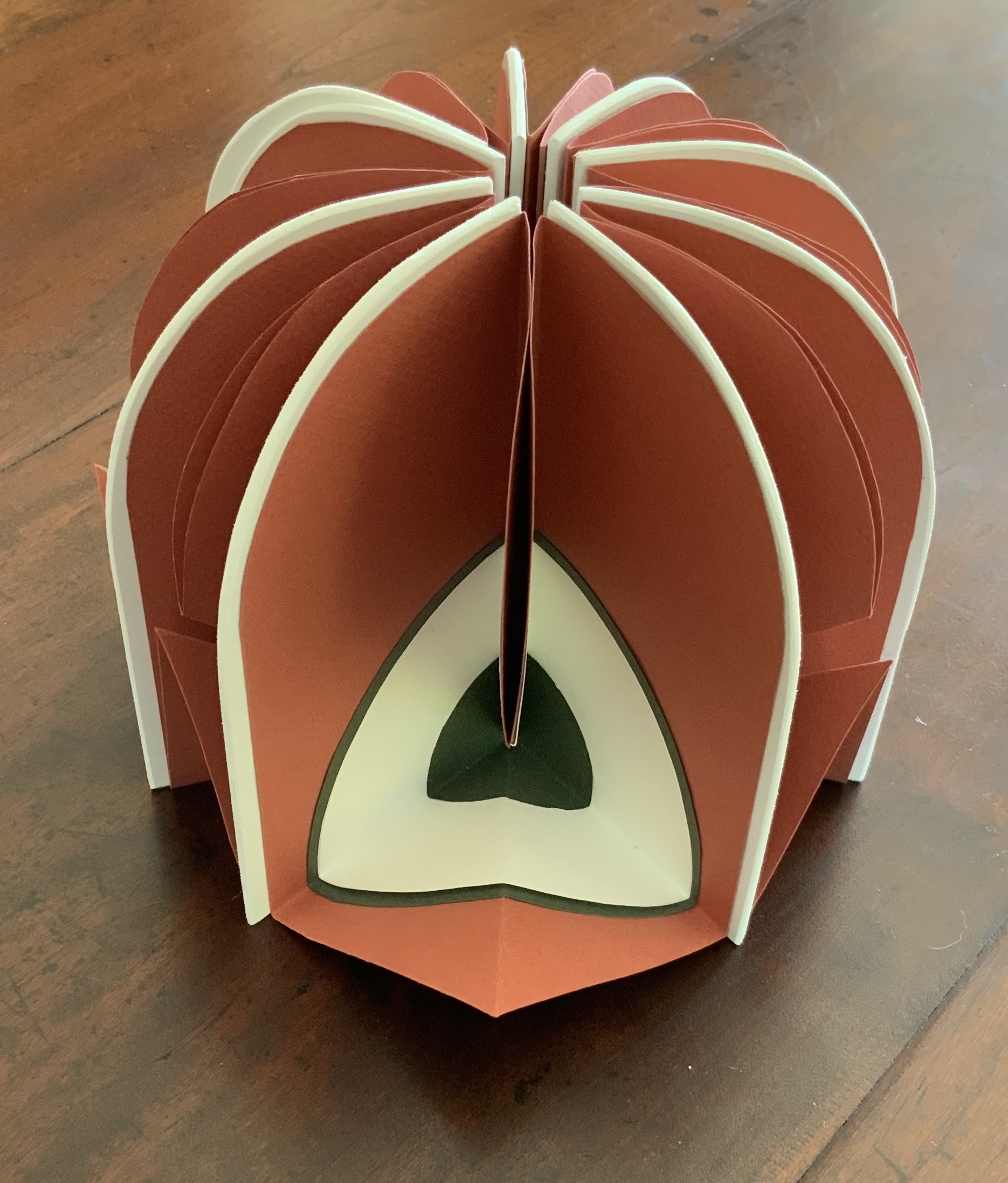

Proposition #15: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in the sacred.

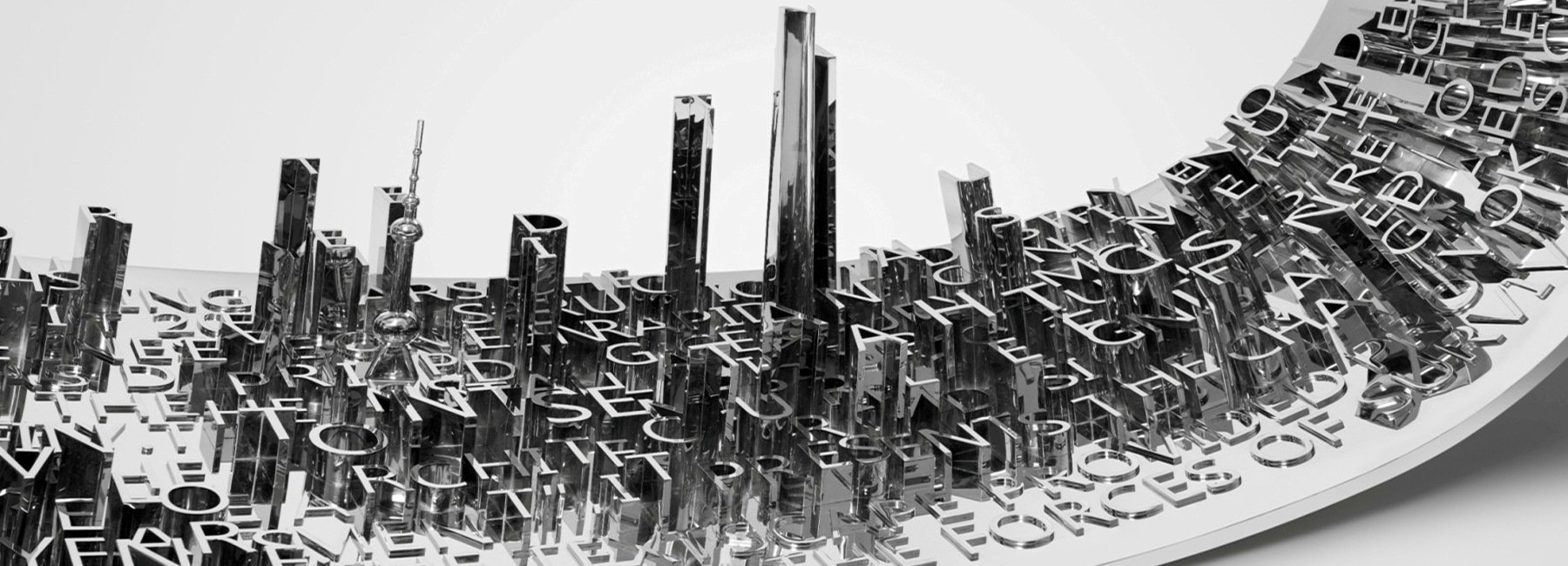

Jeffrey Morin and Steven Ferlauto’s Sacred Space (2003) is an intimate monument of book art. Made intimate by the content and texture of its book, made more intimate by the viewer’s having to construct the chapel. Made monumental by the echo of typographic history, made more monumental in Galileo Galilei’s echo from its floor: Mathematics is the alphabet with which God has created the universe.

Sacred Space (2003)

Jeffrey Morin and Steven Ferlauto

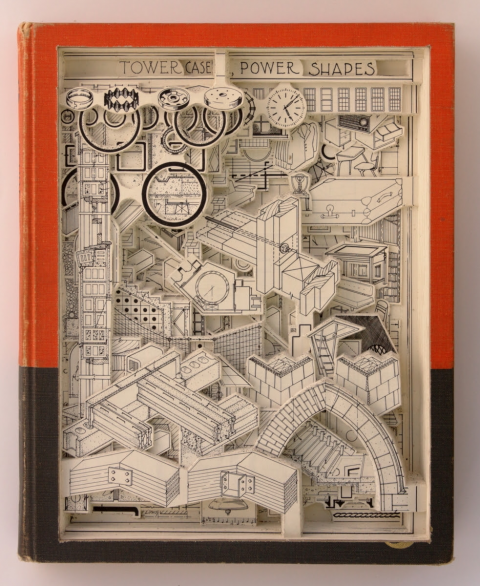

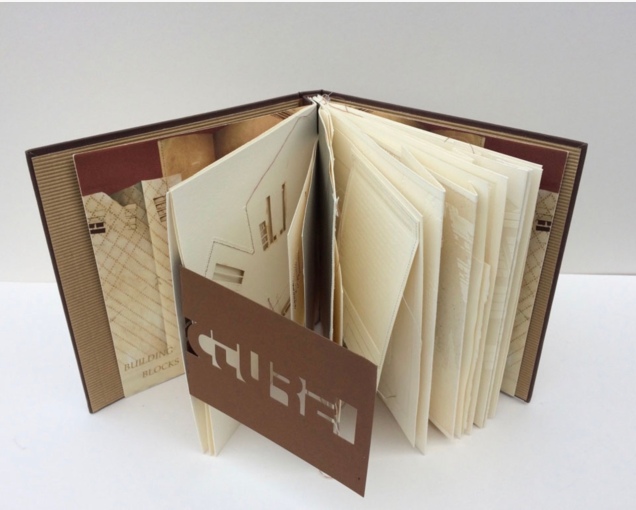

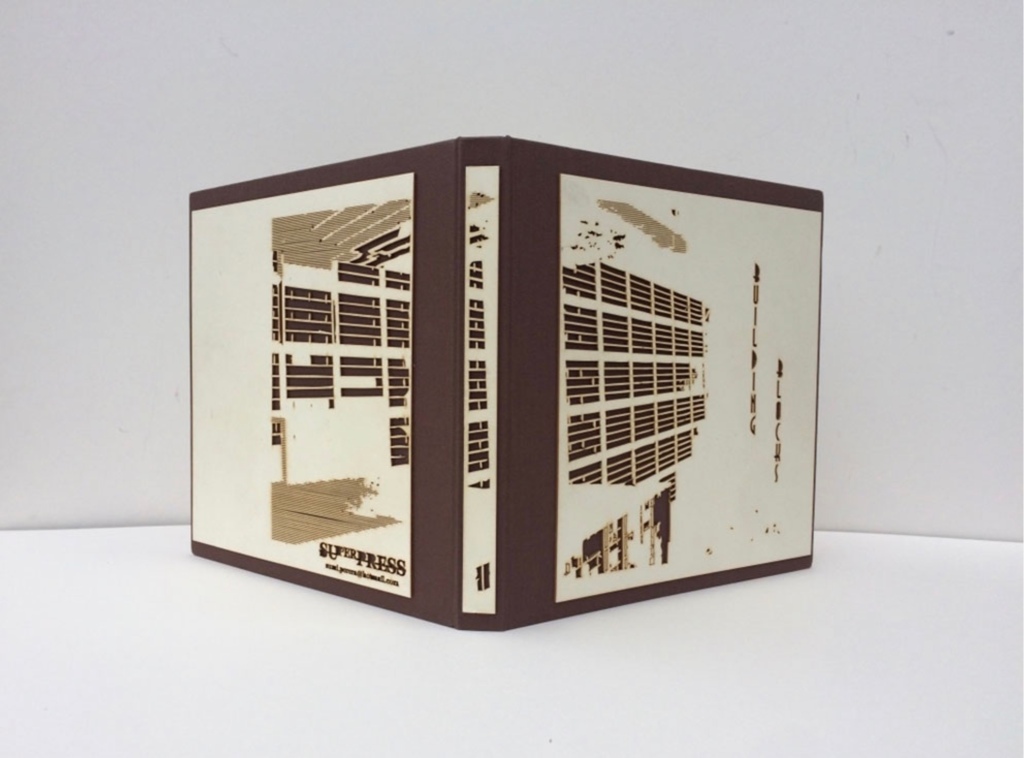

Proposition #16: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in collaboration.

In Victor Hugo’s Nôtre-Dame de Paris (1831), Archdeacon Claude Frollo points to the book in his hand and then to the cathedral and says, “This will kill that”. It is ironic that Hugo’s book (popularly known now by its English title The Hunchback of Nôtre-Dame) was written in large part to save the then-decaying cathedral (post-Revolution, it served as a warehouse), and it succeeded. It is also ironic that, while the fictional character’s metaphor has a point about the book’s permanence of replicability outlasting the building’s permanence of stone, it misses the collaborative foundations of both.

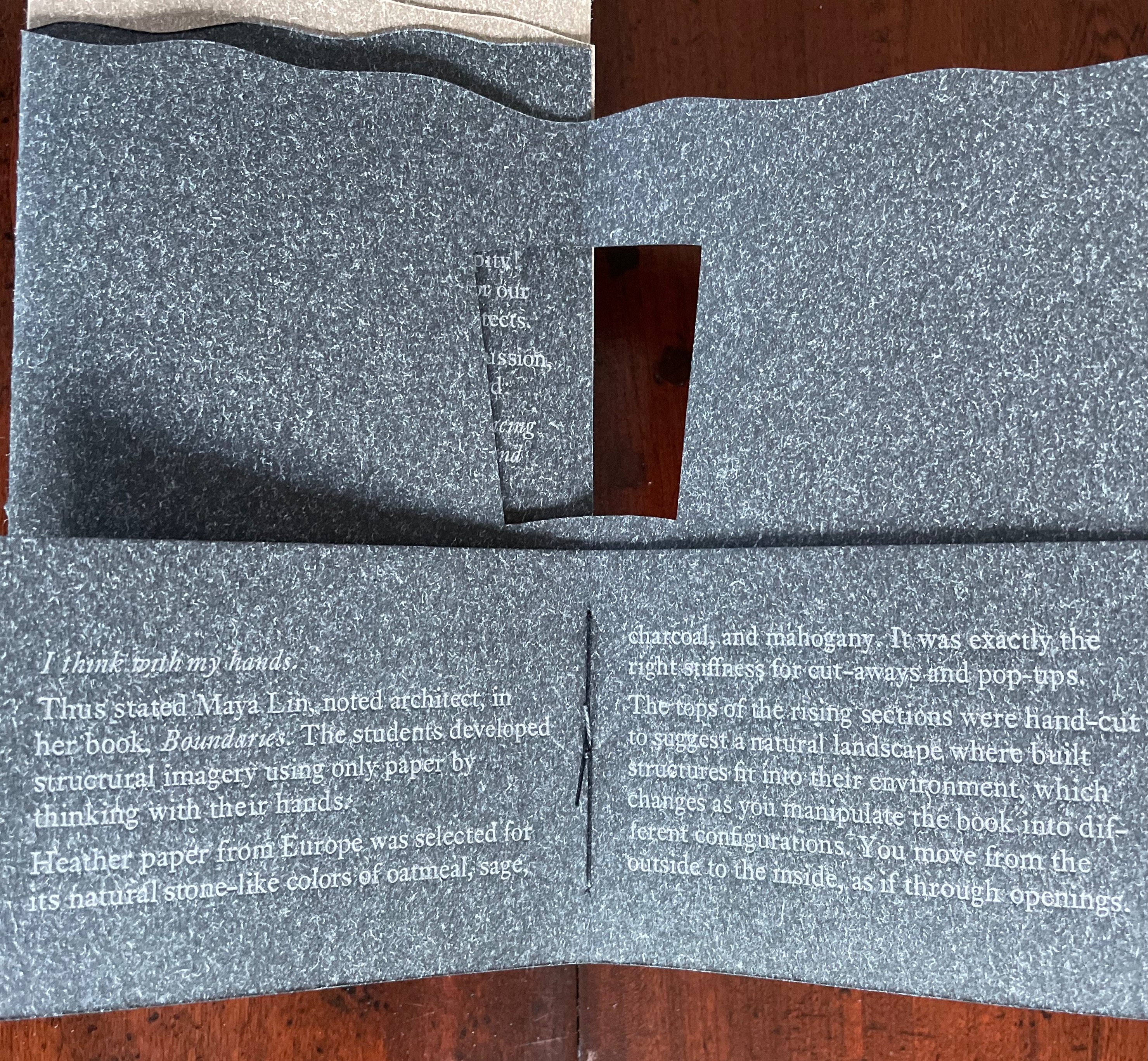

Created by ten students at Scripps College under the direction of Kitty Maryatt, Arch (2010) reminds us that the creation of a book — even a work of book art — is a collaborative effort.

Arch (2010)

Kitty Maryatt, Jenny Karin Morrill, Ali Standish, Alycia Lang, Jennifer Wineke, Mandesha Marcus, Catherine Wang, Kathryn Hunt, Ilse Wogau, Jennifer Cohen, Winnie Ding

Photos: Books On Books Collection

Maryatt’s preface to Arch is entitled “Blueprint” and is brief enough to warrant citing in full:

Books are inherently architectonic. Studying architecture would naturally be profitable to students building their own books.

On January 17, 2010, just days before class was to start, the Los Angeles Times published a fascinating article on contemporary women architects, highlighting a striking building by Jeannie Gang.

Earlier this year, the brand-new President of Scripps College chose The Genius of Women as her inaugural theme. What serendipity! This gave us the perfect inspiration for our artist book: the genius of women architects.

After extensive research and class discussion, a mission statement for the book evolved:

Architecture, like books, is a delicate balancing act between stability and motion, interior and exterior, aesthetic values and structural practicalities.

Books, like building, are fundamentally inhabited spaces. They are incomplete without human interaction.

The first portals were built of post and lintel construction. A curved arch is more difficult: the keystone is needed at the apex to lock the other pieces into position. Building a book is a similarly difficult feat. — Professor Kitty Maryatt

Conclusion: The affinity of architecture and artists’ books lies in our attraction to the beauty of form.

No doubt the proximity of the need for shelter and the need for oral and written language have played some gravitational role of mutual attraction for architecture and books (and latterly artists’ books). But equally, both architecture and artists’ books speak to our attraction to the beauty of form. All of the examples above are re-offered here in support of this proposition. Look at them again.

“Architecture”, “art” and “the book” are all fluid concepts. So it should be no surprise that we arrive at the equally fluid similes: architecture is like book art, book art is like architecture.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in The Blue Notebook, Volume 16 No 2, Spring – Summer 2022.

Further Reading

“Architecture“. 12 November 2018. Bookmarking Book Art.

Carrión, Ulises. 1975. “The New Art of Making Books”. Reprinted in Lyons, Joan. 1993. Artist’s books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press.

Côme, Tony. 2018. “The Typotectural Suites“, The Palace of Typographic Masonry. Accessed 5 April 2021.

Esslemont, David. 2002. Inside the Book. Cefn Mawr Newton Powys, Wales: Solmentes Press.

Goldberger, Paul. 2008. Counterpoint: Daniel Libeskind. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag.

Hugo, Victor, and Jessie Haynes, trans. 1831 (1902). Nôtre Dame de Paris. New York: D. Appleton & Co.

Hugo, Victor, and Nathan Haskell Dole, trans. 1890 (1895). Victor Hugo’s Letters to His Wife and Others (The Alps and the Pyrenees). Boston, MA: Estes and Lauriat.

Lynn, Greg. 2004. Folding in Architecture Rev. ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Academy. See for references to Mario Carpo, Gilles Deleuze and Peter Eisenman.

Macken, Marian. 2018. Binding Space: The Book as Spatial Practice. London: Taylor and Francis.

McEwen, Hugh. 12 January 2012. Polyglot Buildings. Issuu. Accessed 13 March 2021.

Niessen, Richard. 2018. The Palace of Typographic Masonry. Leipzig: Spector Books.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 1996. The Eyes of the Skin. London: Academy Editions.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2009. The Thinking Hand. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2011. The Embodied Image. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Steingruber, Johann David. 1773 (1774). Architectonisches Alphabeth: bestehend in Dreysig … . Schwabach: Johann Gottlieb Mizler.

Tsimourdagkas, Chrysostomos. 2014. Typotecture: Histories, Theories and Digital Futures of Typographic Elements in Architectural Design. Doctoral dissertation, Royal College of Art, London. Accessed 13 March 2021.

Vyzoviti Sophia and BIS Publishers. 2016. Folding Architecture : Spatial Structural and Organizational Diagrams. 14th print ed. Amsterdam: BIS.

Williams, Elizabeth. 1989. “Architects Books: An Investigation in Binding and Building”, The Guild of Book Workers Journal. 27, 2: 21-31.