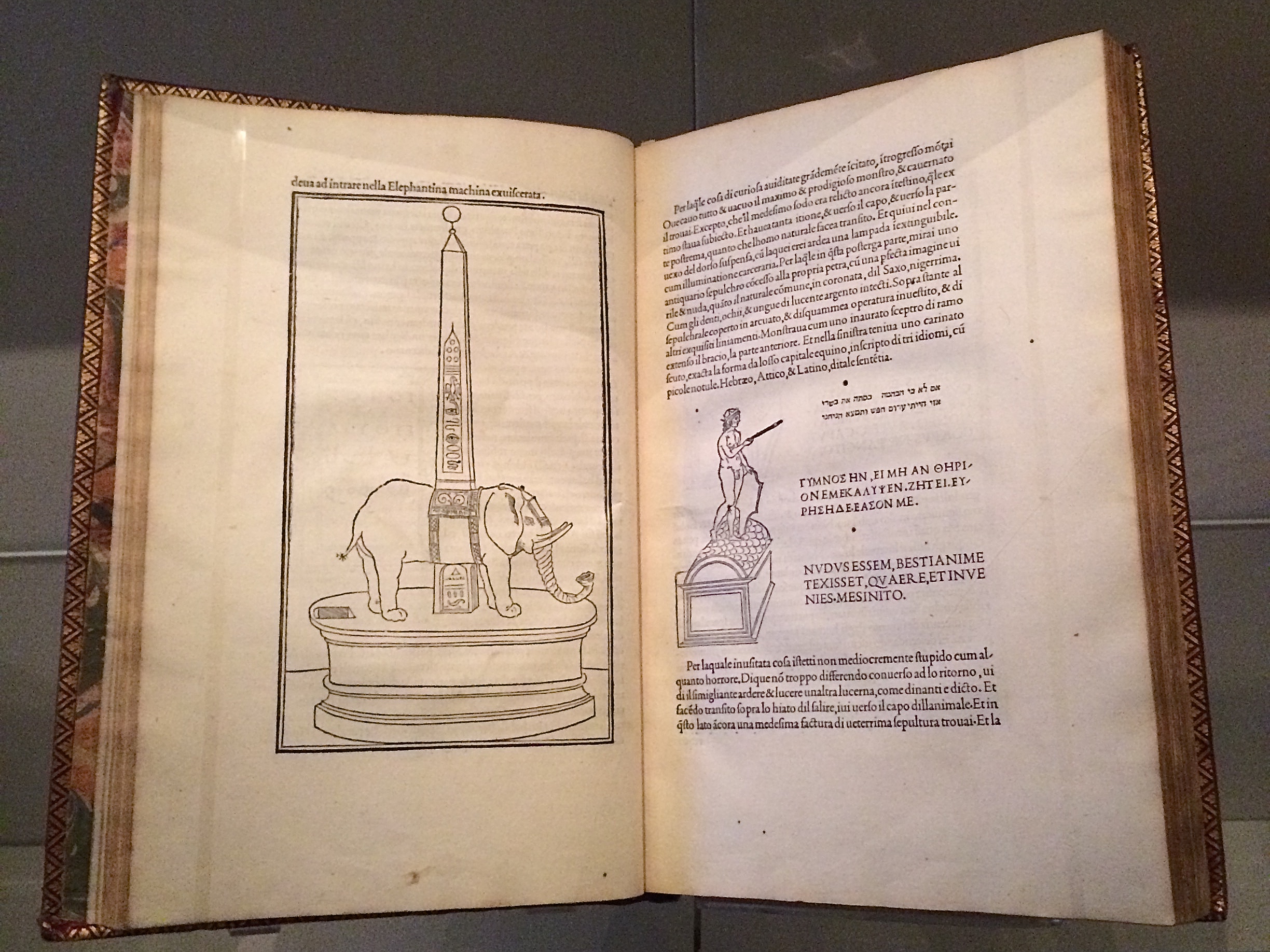

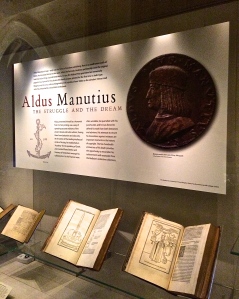

Late afternoon before the long worn wooden benches in the Bodleian’s Convocation Hall, 500 years after the death of Aldus Manutius, Oren Margolis served his audience well, providing them with a richer appreciation of the “finest printed book of the entire Renaissance”* – the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili – and of its publisher Aldus Manutius.

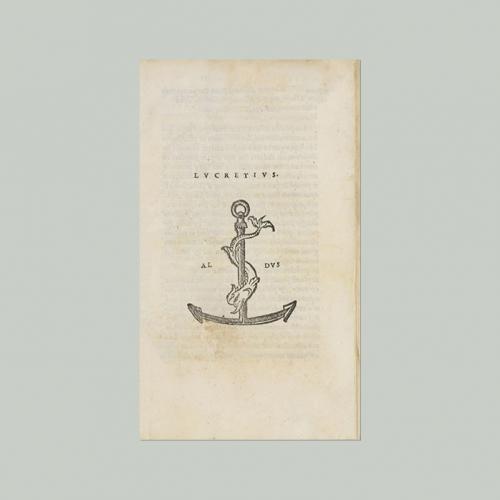

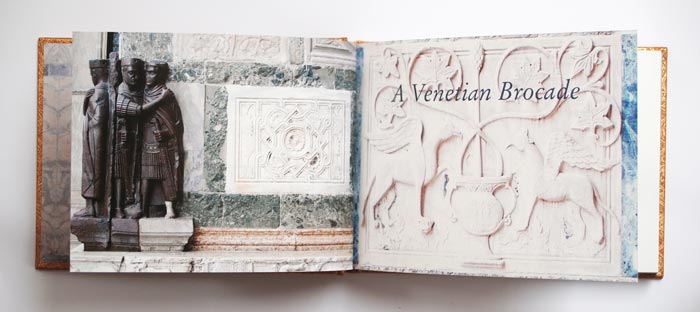

Drawing our attention to the more sculptural qualities of Venetian Renaissance printed books over the Florentine and to the evidence of the humanist agenda that drove Manutius, he led us to the page where Poliphilo (lover of all things, but in particular Polia, the ideal woman pursued to the end of the book) stands before a carving that foreshadows the Aldine Press device: a dolphin entwined around the shank of an anchor. The Aldine Press device was inspired by a similar image on an ancient Roman coin given by Pietro Bembo to Aldus, who wrongly associated it with Augustus and his proverb Festina lente (“Make haste slowly”) and adopted both for his printing and publishing business.

Erasmus praised Aldus, saying that he was “building a library which knows no walls save those of the world itself”.

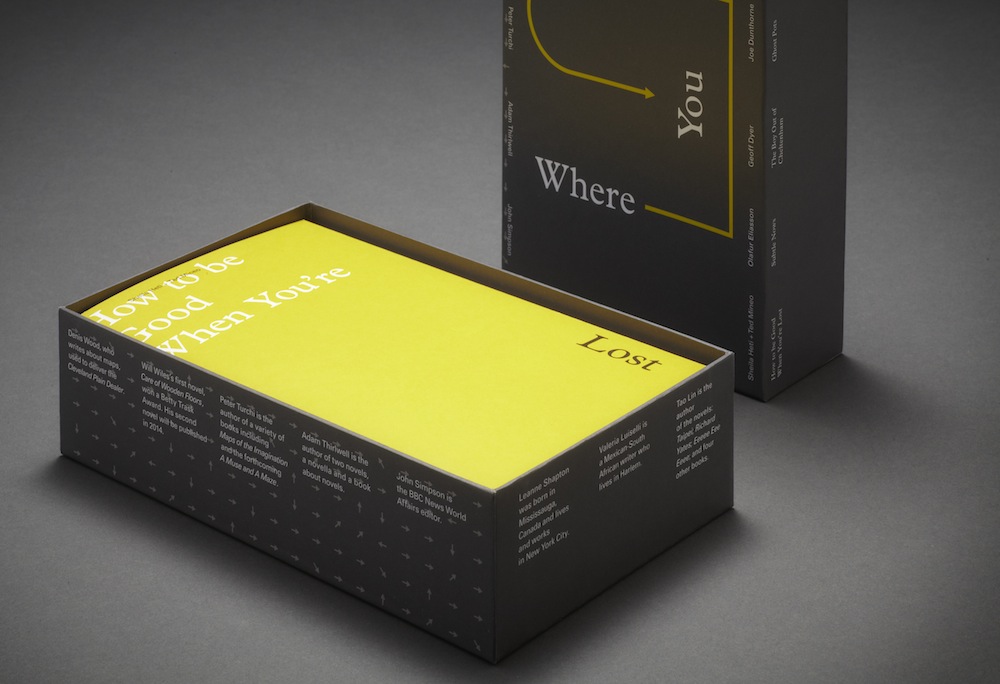

For all of 2015, the world enjoyed a multitude of celebrations of the contribution of Aldus Manutius to publishing, printing and the book. After Gutenberg, Fust and Schoeffer, Aldus Manutius was perhaps the most important printer of the Renaissance. His portable books are still here, although locked away or displayed under glass, no longer so portable. Until now.

The Manutius Network 2015 provides a running list, links for some of which are provided below, including the online exhibition associated with Margolis’s talk. See also below, added in May 2016, the belated exhibition “Aldo Manutius: The Renaissance in Venice” at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice.

In the Proscholium, The Bodleian Library Oxford

Invitation from the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana

The Grolier Club exhibition. See the New York Times coverage here.

In aedibus Aldi

The Brigham Young University’s Harold B. Lee Library

John Rylands Library

University of Manchester

The afterlife of Aldus : posthumous fame, collectors and the book trade

Edited by Jill Kraye and Paolo Sachet.

London : The Warburg Institute, 2018.

from Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, 1499

University of Glasgow

International Conference

Celebrating Aldus Manutius

University of California, Los Angeles

Aldo Manutius: The Renaissance in Venice

Exhibition poster containing detail of ‘Portrait of a Woman as Flora’ (c1520), by Bartolomeo Veneto © Eton College

From Crispin Elsted’s review of the Thames & Hudson facsimile edition of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Parenthesis, December 2000, No. 5:

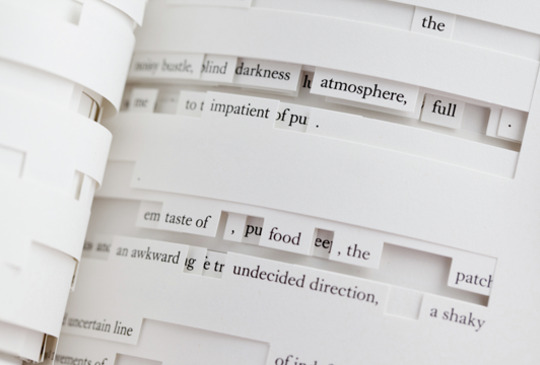

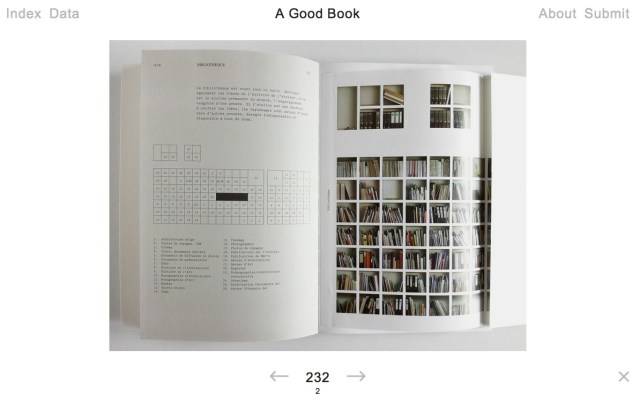

I once spent three hours in a library with a copy of the Aldine edition of Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, and I have never known a book take my breath away so consistently. Every page is a masterpiece: the dance of text with the more than 170 woodcuts; the firm, male stature of the typeface; the crisp spring of the impression; the elegant proportion of the page — all combine to an end in which the craft of printing and design carry the text into an atmosphere not of its own making. This new edition has the appearance of a fine actor in a part lately played by a great one. Here are the signs of the grace that greatness lent the commonplace five centuries ago; and in these signs, the commonplace finds here another advocate for its small claims to our time.

Timelines are, of course, for looking further back as well as forward. Earlier this year, April 2012 marked the fifteenth anniversary of the publication of Liane Lefaivre’s Leon Battista Alberti’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-Configuring the Architectural Body in the Early Italian Renaissance (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997) and the online publication of The Electronic Hypnerotomachia, which contains the facsimile text and illustrations. The online publication of extracts from Lefaivre’s book illustrates the linking prefigured by the “card stack” approach of HyperCard. What MIT Press and TU Delft, Lefaivre’s affiliation, host on their servers are not ebooks or even e-incunabula of the sort we experience today, but they are clearly forerunners to them.

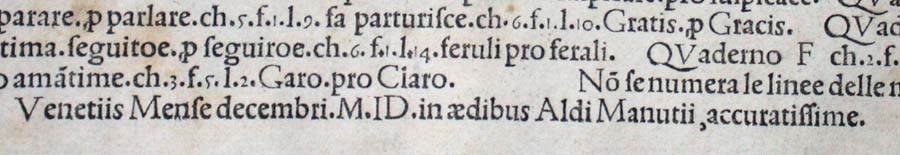

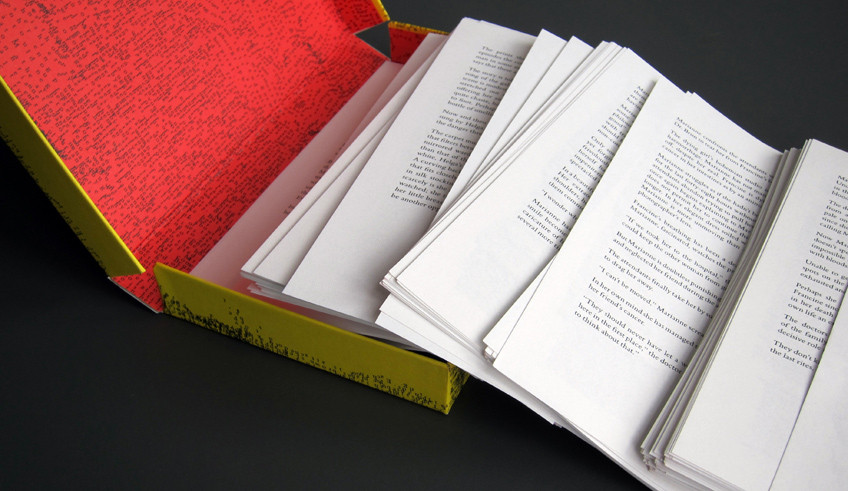

In twenty-eight more months, December 2014, we will see the 515th anniversary of the original work’s publication by Aldine Press (Venice, December 1499). The founder Aldus Manutius did not normally publish heavily illustrated books. The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili was the exception and the only commissioned work that Manutius undertook. The exception reflects favorably on the overall success of his business and supports the view that Venice had become the capital of printing and publishing very shortly after the invention of printing by moveable type.

The book unveils an inscrutable, almost comic-book-illustrated story, glittering with made-up words in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic (including proto-Greek, -Hebrew and -Arabic fonts). In addition to the page displays sculpted into shapes such as goblets, this one volume displayed the technological mastery of and improvement on the new Roman (as opposed to the heavy Gothic) typeface Bembo. According to Norma Levarie in The Art & History of Books (New York, 1968), this singular volume revolutionized typography in France in less than twenty-five years.

Somewhat like software releases, though, the 1499 edition came with bugs. The colophon to the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili falls at the end of a full page of errata.

Initiated in 2015 in celebration of the anniversary and acknowledgement of the more than 100 Aldine editions in the Wosk McDonald Collection, Simon Fraser University’s Aldus@SFU is the digitization of 21 Aldine volumes published between 15011 and 1515. The image above is the edition of Lucretius’ De rerum naturam, published just after Manutius’ death in 1515.

See also “More Manutius in Manchester and More to Come“, Bookmarking Book Art, 1 June 2015.