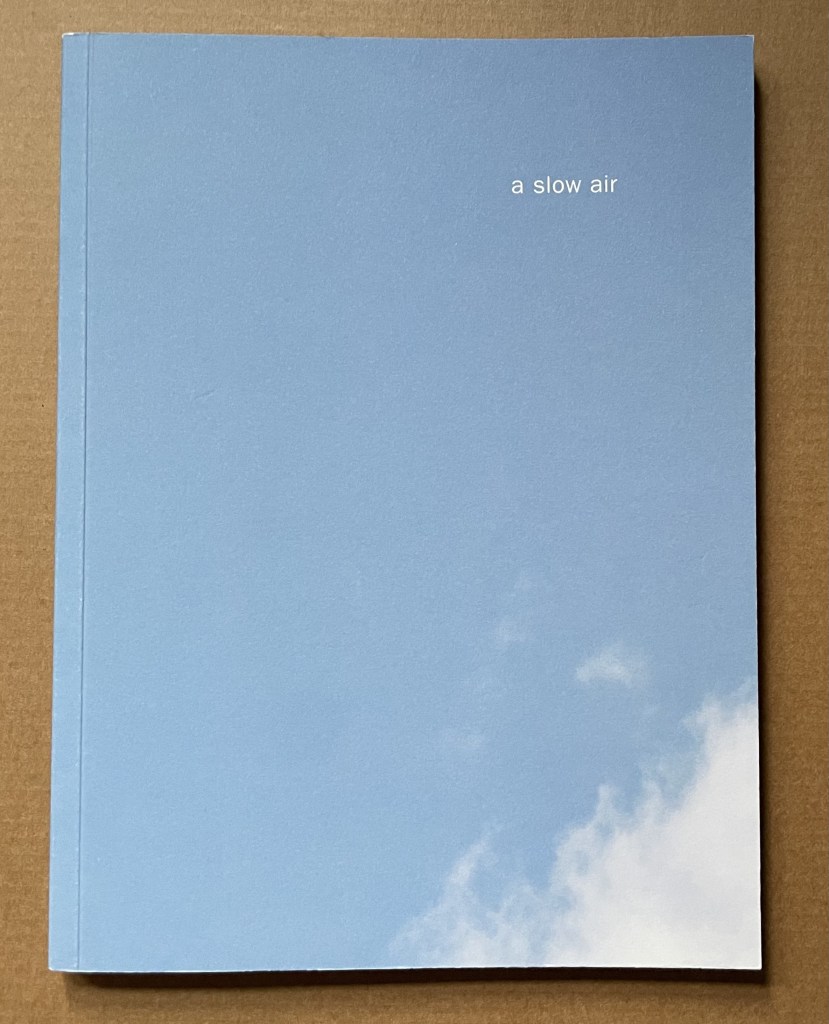

Tau blau / Dew Blue (2013)

Tau blau / Dew Blue (2013)

Barbara Beisinghoff ; Solander box in linen, handbound Vera Schollemann; Flax paper, handmade by John Gerard.

Solander box: H240 x W200 x D32 mm. Flagbook: H220 x W180 mm. Edition of 38, of which this is #22. Acquired from the artist, 30 December 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Familiarity with Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale Hørren /The Flax enhances appreciation of Barbara Beisinghoff’s Tau blau / Dew Blue. Andersen gives a voice to the plant that expresses its joy, pain, hope and observations at each stage of its blooming, being harvested, turned into linen and clothing then paper, and finally consigned to flames. The H.C. Andersen Centre offers Jean Hersholt’s translation of it here.

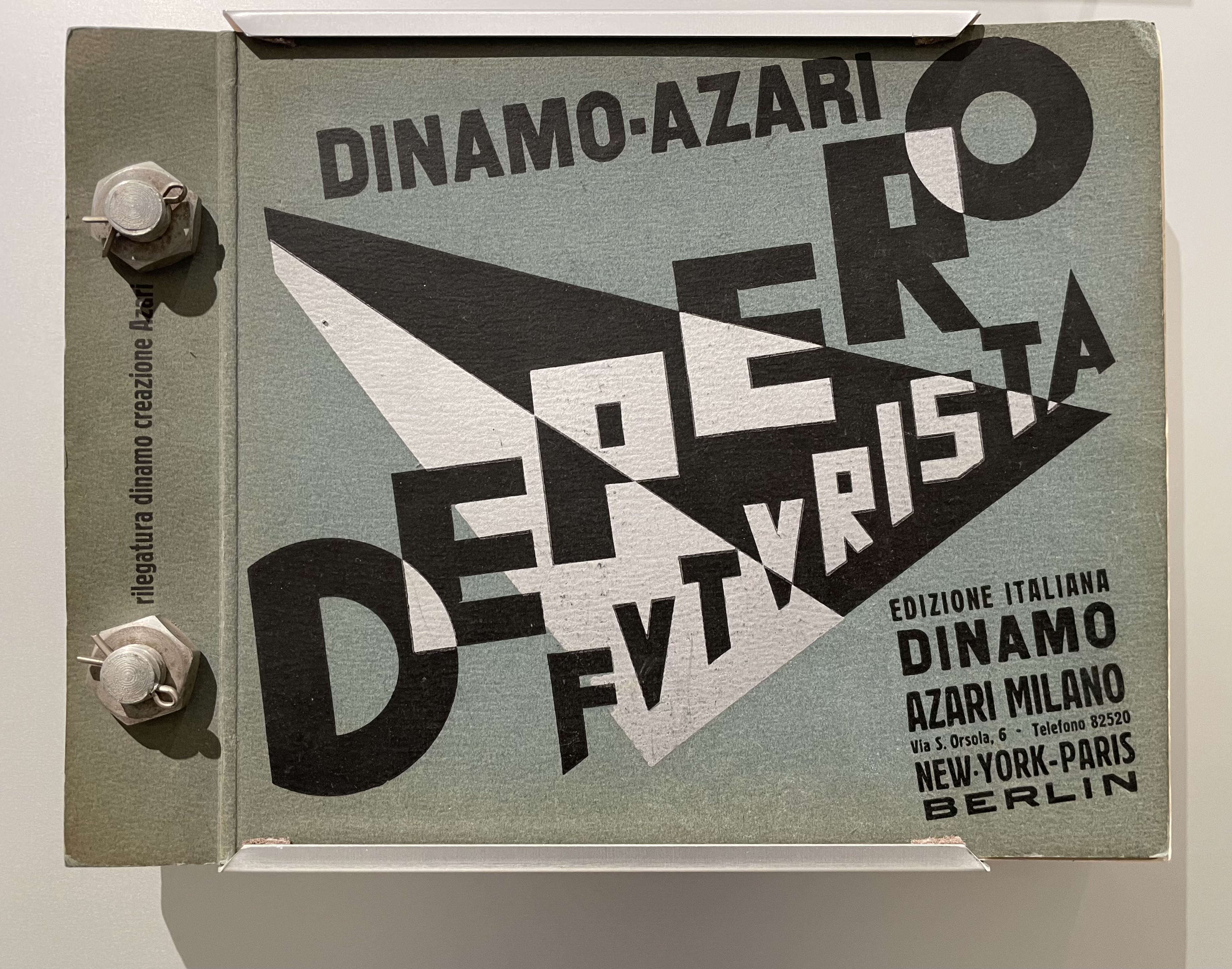

Only the opening paragraph of the story appears in Tau blau / Dew Blue, but Beisinghoff documents and illustrates the stages from her own cultivation of flax, observation of its growth and preparation of its processing. And with the etching, drawing, watermarking, handmade papers, linen cloth and thread, and binding structure, Beisinghoff suffuses the spirit of the tale’s metamorphosizing plant throughout the whole of Tau blau / Dew Blue.

From the blue of the plant’s blossoms to the white of its change into linen and paper to the red, burnt orange and black of its sparks and ash when it is consumed by fire in the end, all of the story’s colors are replayed across Tau blau / Dew Blue from its Solander box to its covers and spine like motives in a Baroque musical piece.

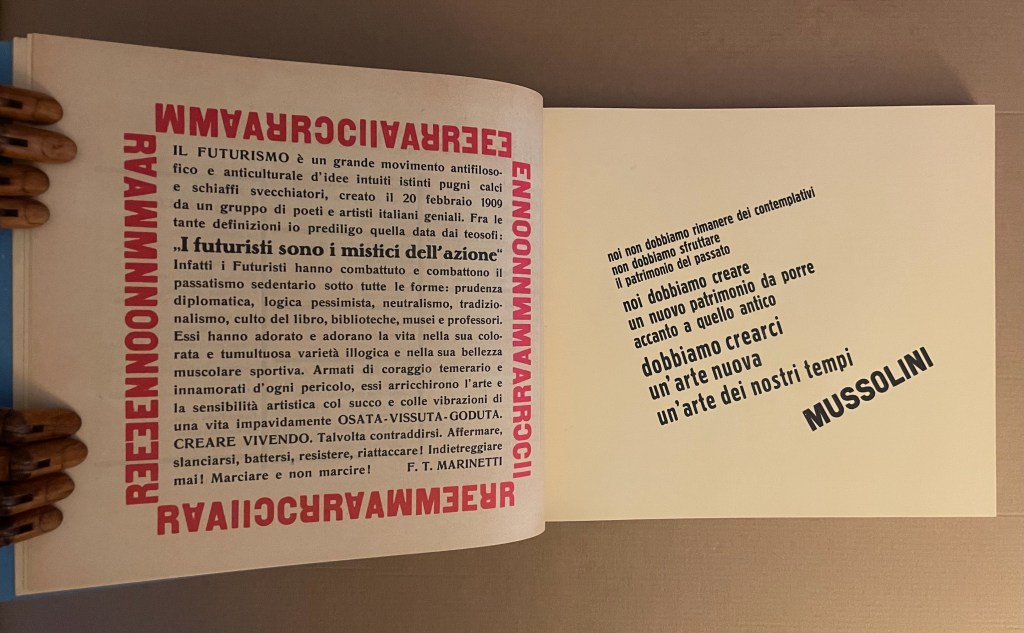

In a concerto, motives play off one another and develop. In Tau blau / Dew Blue, the motif of nature (the plant) plays off the motif of artifice and the manmade (the fairy tale, music, linen, paper, etc.). On the front cover (above), a young girl, surrounded by large damselflies, plays a fiddle or violin and seems to hover above a silver foil image of flax thread and tools for making it. In the spread above alongside the front cover, the specks rising over the staves and musical notes (a recurring motif in itself) recall the tale’s final passage in which the bundle of papers (made from linen rags) is cast into a fire:

“I’m going straight up to the sun!” said a voice in the flame. It was as if a thousand voices cried this together, as the flames burst through the chimney and out at the top. And brighter than the flames, but still invisible to mortal eyes, little tiny beings hovered, just as many as there had been blossoms on the flax long ago. They were lighter even than the flame which gave them birth, and when that flame had died away and nothing was left of the paper but black ashes, they danced over the embers again. Wherever their feet touched, their footprints, the tiny red sparks, could be seen.

Images of tools — whether for preparing flax or for making the products from it — also recur on the inside of the front and back covers and throughout the book. The human figures alongside the tools, however, appear engaged in more than manufacturing. Elsewhere in the book, they dance, they sit and meditate or write, they row on ponds beside the growing flax. The fairy tale, too, has these Romantic juxtapositions of nature, art and craft. So, again, the spirit of Andersen’s tale finds another way into Tau blau / Dew Blue.

Inside front and inside back covers.

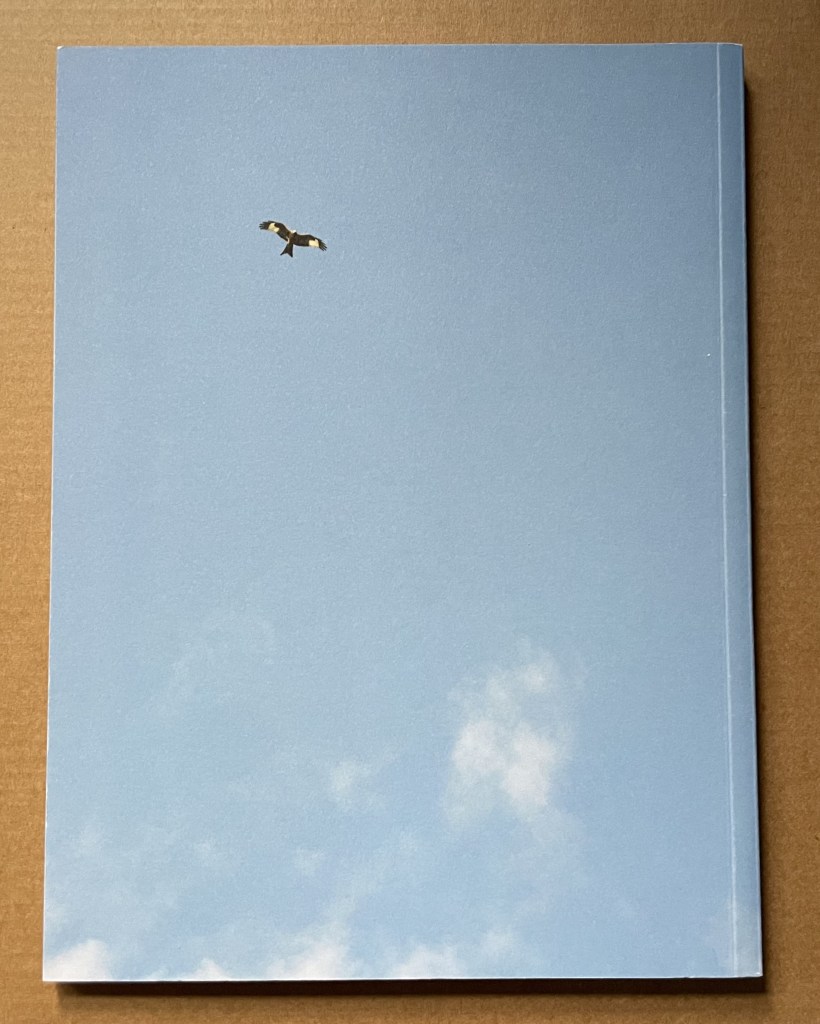

The front cover also announces another motif in those coils of thread below the young girl’s feet. Within the coils is the image of a Fibonacci spiral, which appears on the back cover and throughout the book in different ways. It can be found drawn and printed. It can be found in watermarks in the handmade paper. It can be found in the arrangement of florets in flax. Being a composite flower, flax blossoms display the spiral based on the Fibonacci sequence 1, 2, 3, 5 … 233, and so on. These numbers are waterjet-drawn on the pure flax paper below and explained in an entry printed on the adjacent plain handmade paper folio. By appearing on the book’s front and back covers, the spiral echoes the beginning and ending cycles of birth and rebirth the flax goes through in the folktale.

The Fibonacci spiral on the front and back covers.

The sequence of Fibonacci numbers 1, 2, 3, 5 … 55, 89, 144, 233 … watermarked on handmade flax paper with a water jet.

Description of the Fibonacci spiral side by side with quotation from Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917), drawing on Leibniz’s Rationalist philosophy.

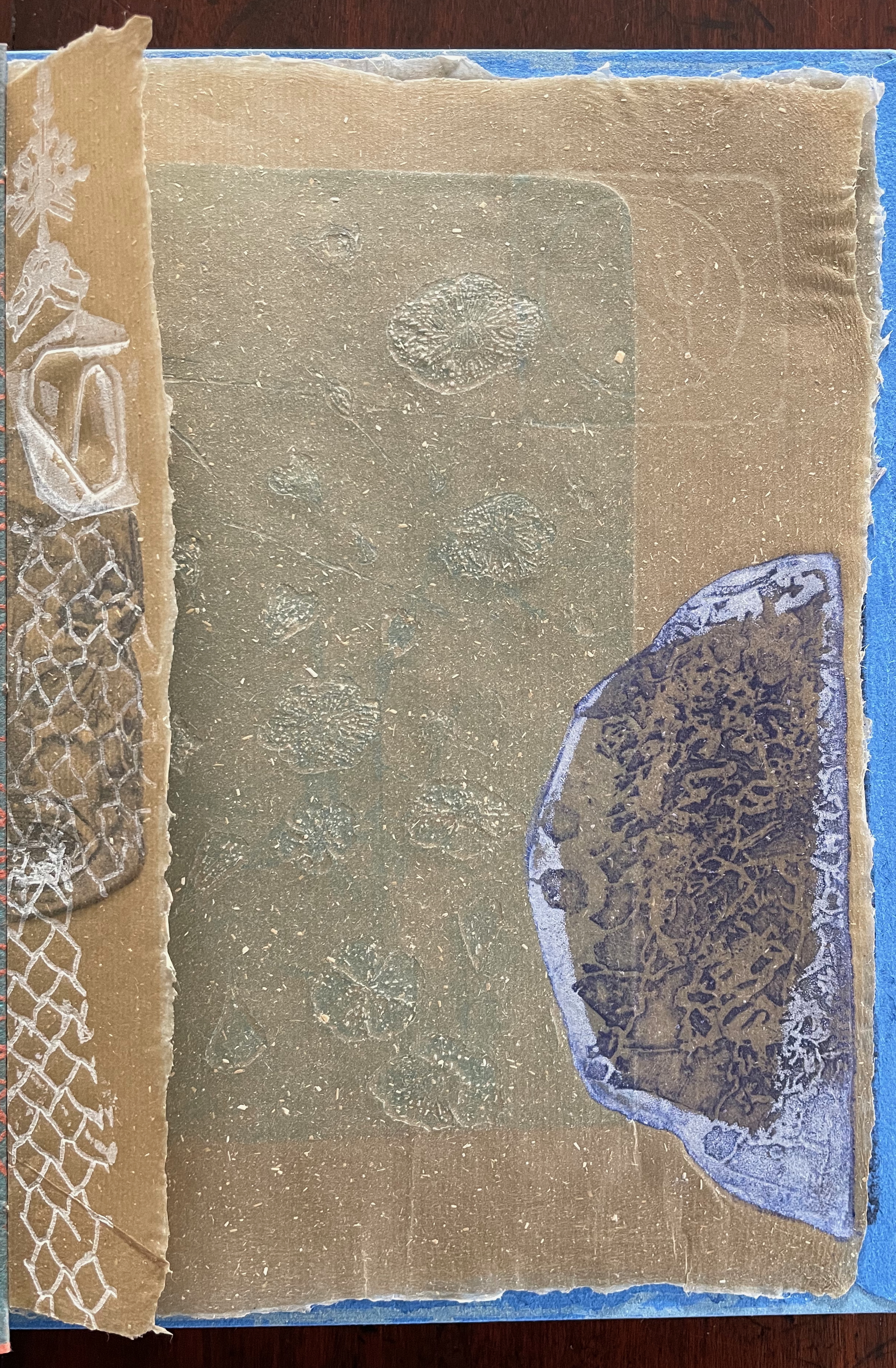

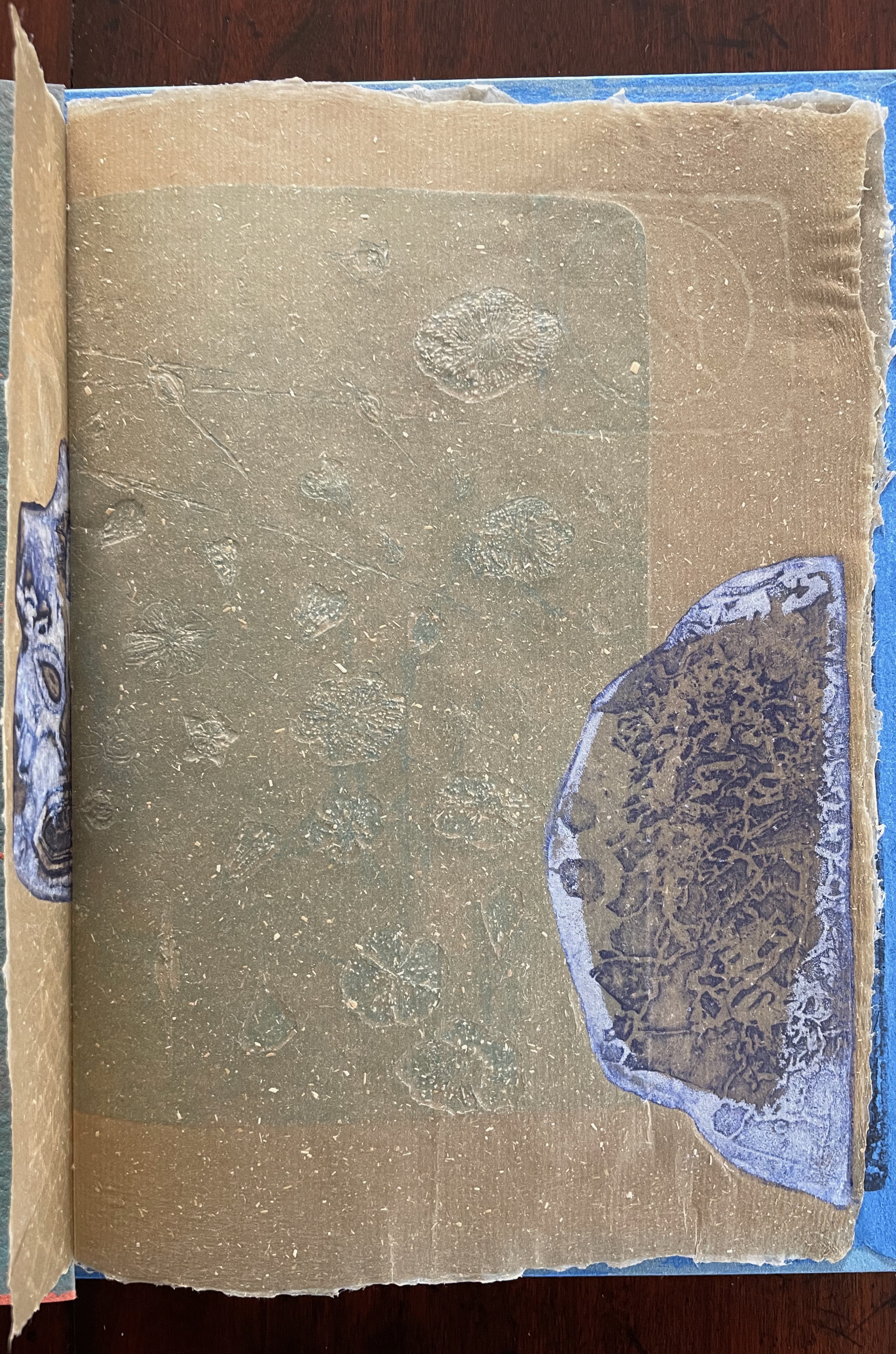

To organize and weave her motives together, Beisinghoff uses an accordion spine to whose peaks eleven sets of folios are sewn with linen thread. Three of the eleven are 4-page folios consisting of blue handmade paper. Another three 4-page folios consist of pure flax paper (handmade by John Gerard). The remaining five gatherings have 8-page folios, each consisting of a pure flax paper folio around a blue or plain one.

Side and top views of the accordion spine.

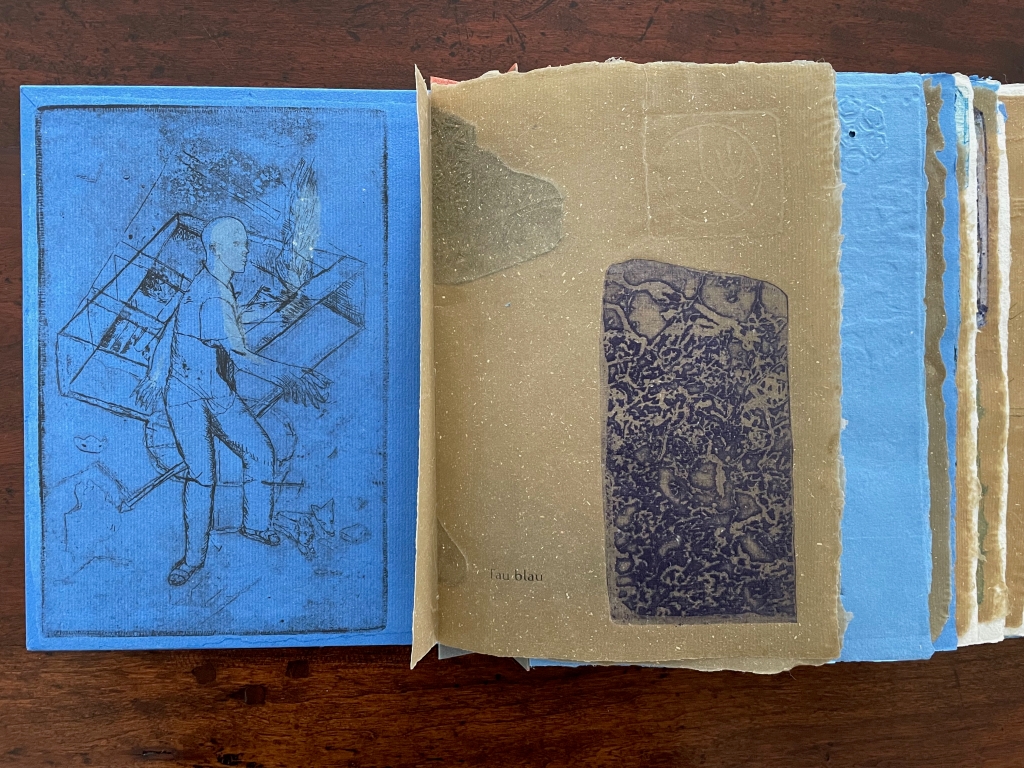

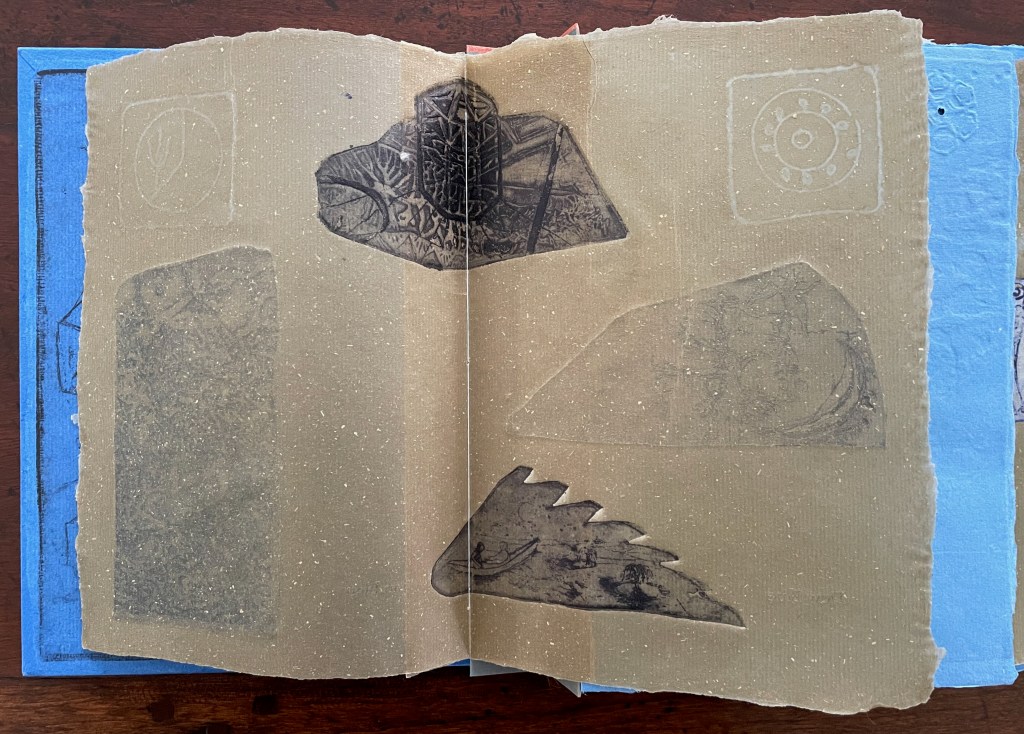

The first pure flax folio begins the book, displaying two title pages (German and English) and two etchings on its first and last pages. In the center spread, two more etchings appear. A watermark symbolizing phyllotaxis shows through in the upper left, balanced by a watermark with a cross section of a flax stalk in the upper right of the center spread. The texture and weight of the flax paper allows the impress and shadow of the etchings to stand out on both sides against the inking and watermarks.

Inside front cover and Tau blau title page and etching.

Center spread of first flax paper folio. Note the watermarks in the upper left and right corners.

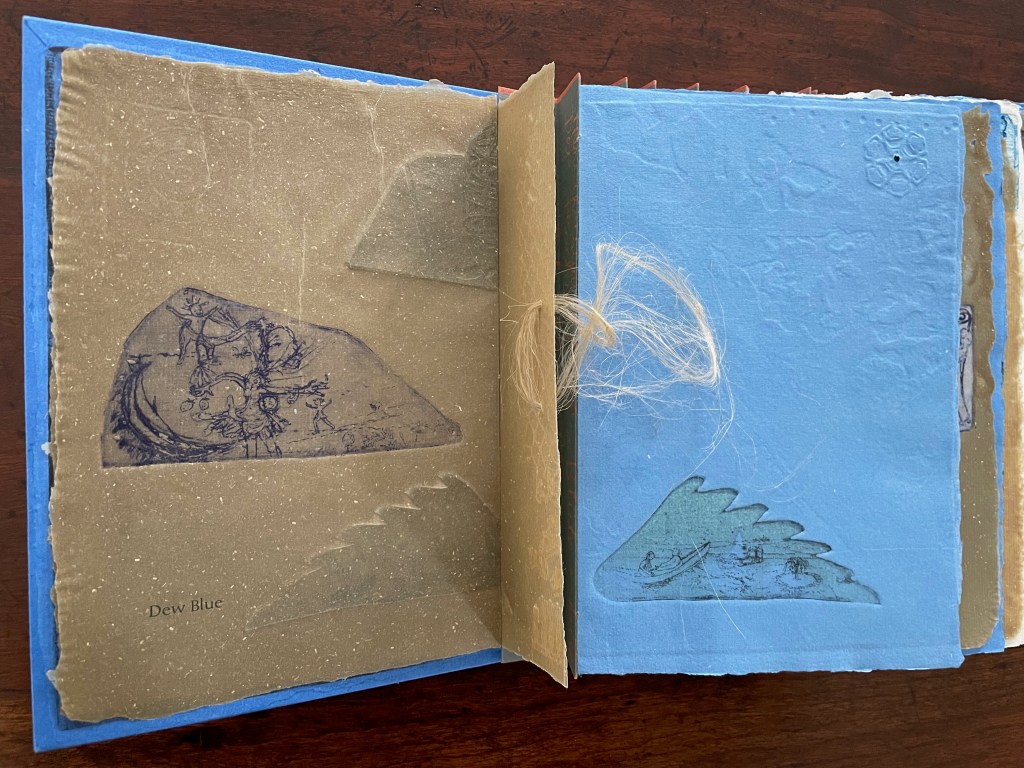

Dew Blue title page and etching, loop of flax fibers, first page of blue handmade paper folio; note its boating image repeated from the prior center spread.

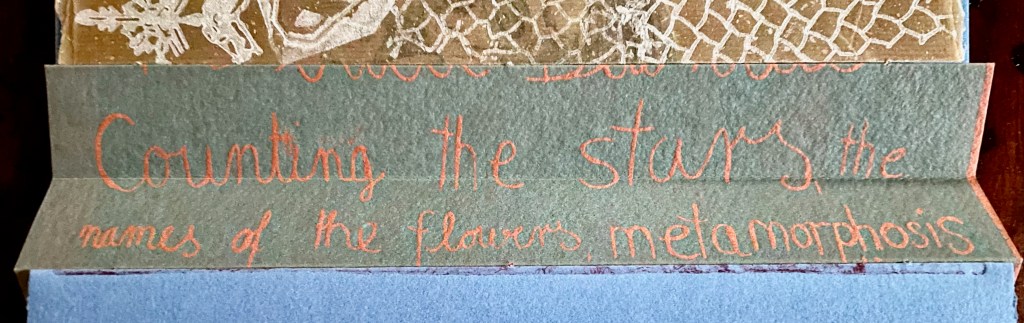

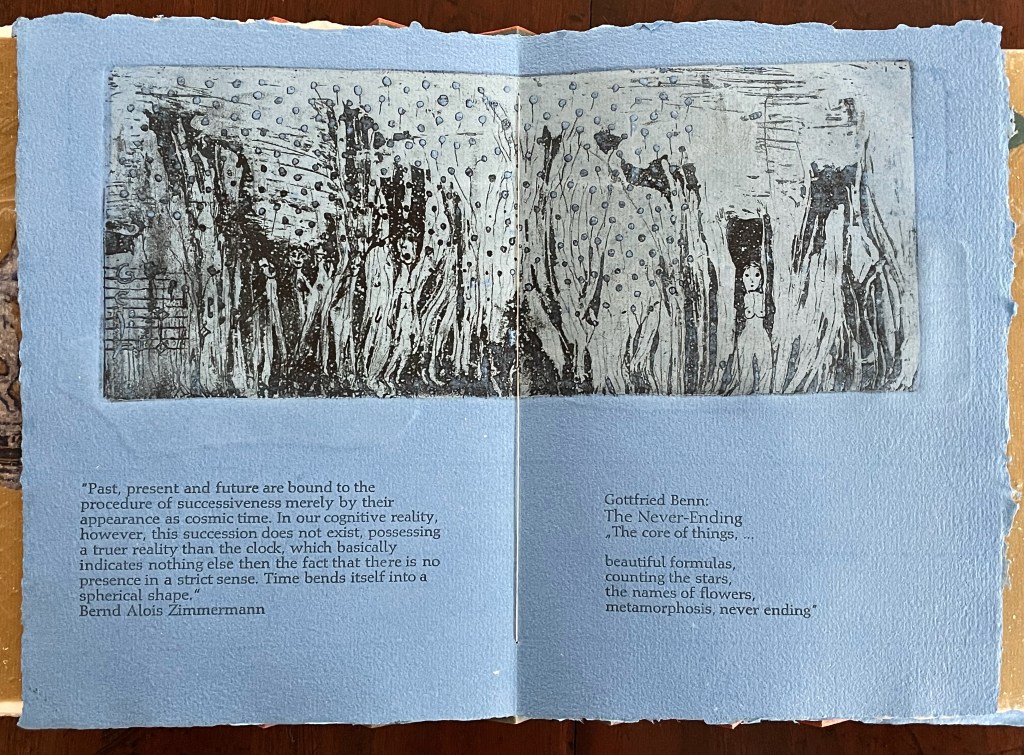

Following the pure flax folio, the first all blue folio gives us that introductory excerpt from Andersen’s fairy tale. Next comes a description of flax comes from Leonhart Fuchs’ Book of Herbs (1543), then the series of planting and harvesting observations from Beisinghoff, then the refrain from Clemens Brentano’s poem “Ich darf wohl von den Sternen singen” (1835), then philosophical observations drawing on G.W. Leibniz from D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917), a much-quoted theorem of musical composition from Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Intervall und Zeit (1974), and finally (below) a passage of text by Gottfried Benn from the Hindemith oratorio Das Unaufhörliche / The Neverending (1936). In the valleys of the accordion spine, some of the lines from Andersen, Fuchs, Beisinghoff and Been appears handwritten in orange paint.

Translated fragment of Benn’s lyrics for Paul Hindemith’s oratorio Das Unaufhörliche / The Neverending (1936).

Even with these additional texts, Andersen’s fairy tale remains the most central text in Tau blau / Dew Blue, despite the brevity of its excerpt. Brentano’s Romantic/religious expostulations (“O Star and Bloom, Garb and Soul, Love, Hurt and Time for evermore”) sound like those of the plant in the story’s final passage. The occurrence of Fibonacci’s spiral in the plant may be a physical fact, but Beisinghoff turns it into something more mystical by placing the description of phyllotaxis next to Leibniz’ and Thompson’s transcendental view of mathematical science and natural philosophy. Likewise she links the texts from Bernd Alois Zimmermann and Gottfried Benn to the fairy tale by placing them beneath the etching that captures the flax plant’s singing and dancing into its transformation by fire.

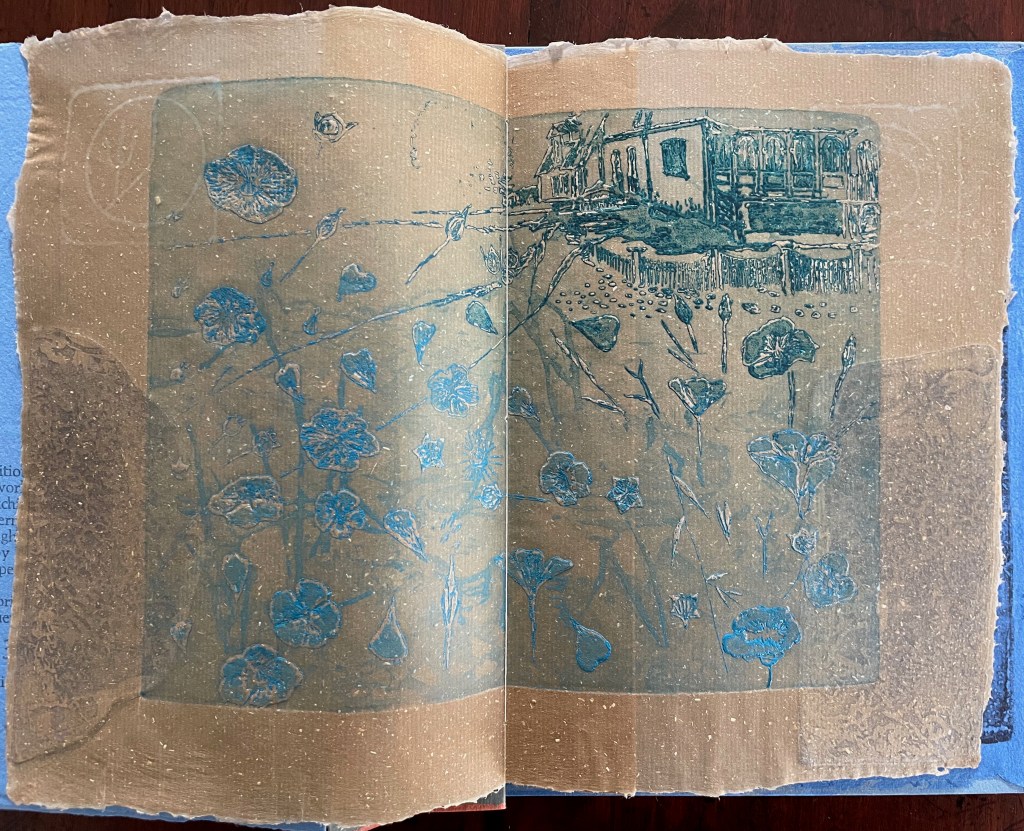

Below is the final folio of the work. Like the first, it is made completely of flax paper, but its center spread offers a fuller image: flax blossoms and stalks float in the foreground, and in the background is a sketch of Beisinghoff’s residence where she grows her flax. Like the Fibonacci spiral on the front and back covers, the first and last flax folios round out the work. But go back and listen for the hidden sound installations accompanying Dew Blue. Noticing Beisinghoff’s abstract musical notation, indulge yourself with recordings of a Swedish folk song (“Today is supposed to be the big flax harvest” here or here) to which the notation and phrases allude, and as the flax papers turn and wave on their accordion peaks, listen carefully for their musical rustle.

The final pure flax paper folio.

Tule Bluet damselfly perched on flax leaf. Photo: John Riutta, The Well-Read Naturalist (2009). Displayed with permission.

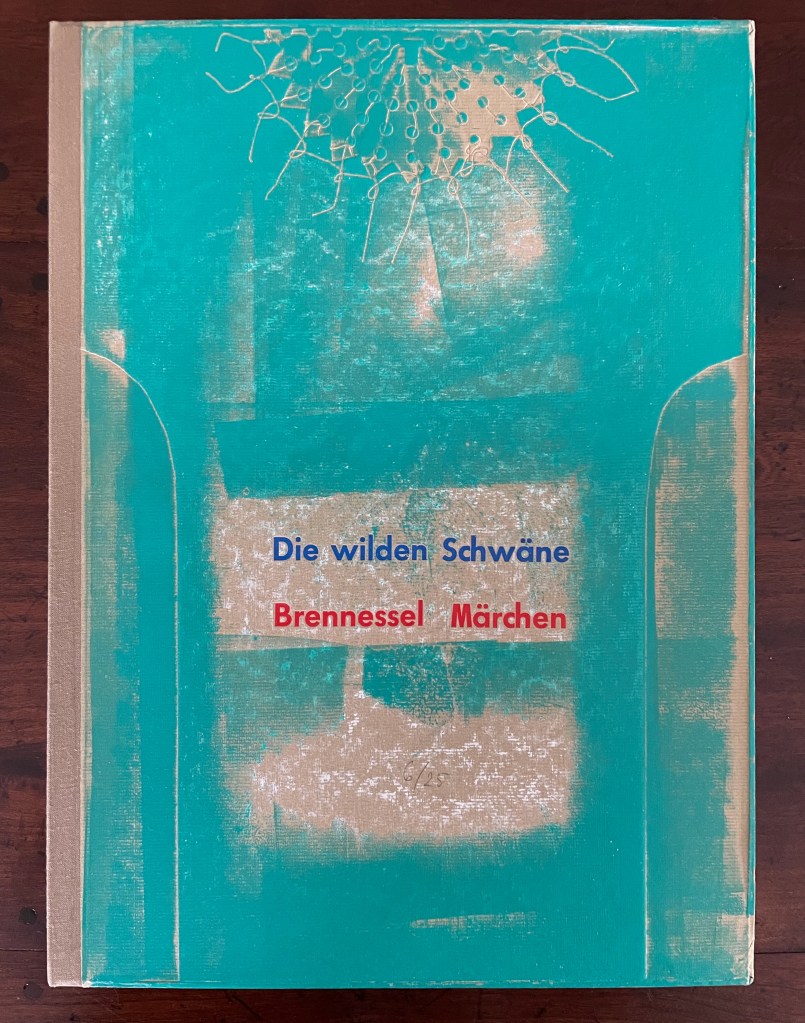

Die wilden Schwäne (2001)

Die wilden Schwäne (2001)

Barbara Beisinghoff

Box with embossed cover holding folios wrapped in chemise. H35o x W250 mm. 18 folios. Edition of 25, of which this is #6. Acquired from the artist, 20 December 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

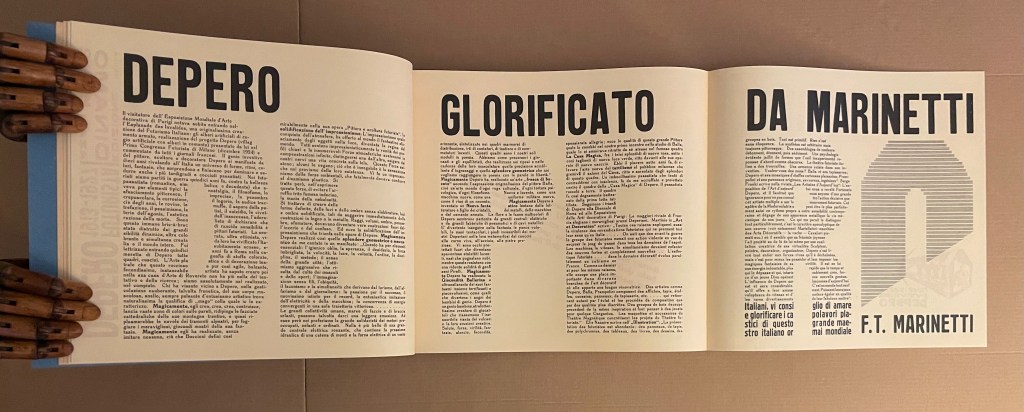

Barbara Beisinghoff’s Die wilden Schwäne is an exemplar of collaboration and craft. In it, she even requires collaboration between Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. Andersen’s Die wilden Schwäne and the Grimms’ Die sechs Schwäne are based on the same tale of brothers turned into swans who are saved by their sister Elisa’s diligent and mute harvesting, pulping, spinning and sewing of stinging nettles into shirts that break the spell when donned. H.C. Andersen, however, is verbose and elaborate in his telling (even including vampires!), and Beisinghoff has done a bit of nipping and tucking with the more succinct Brothers Grimm to create a version more suited to the artist’s book she creates.

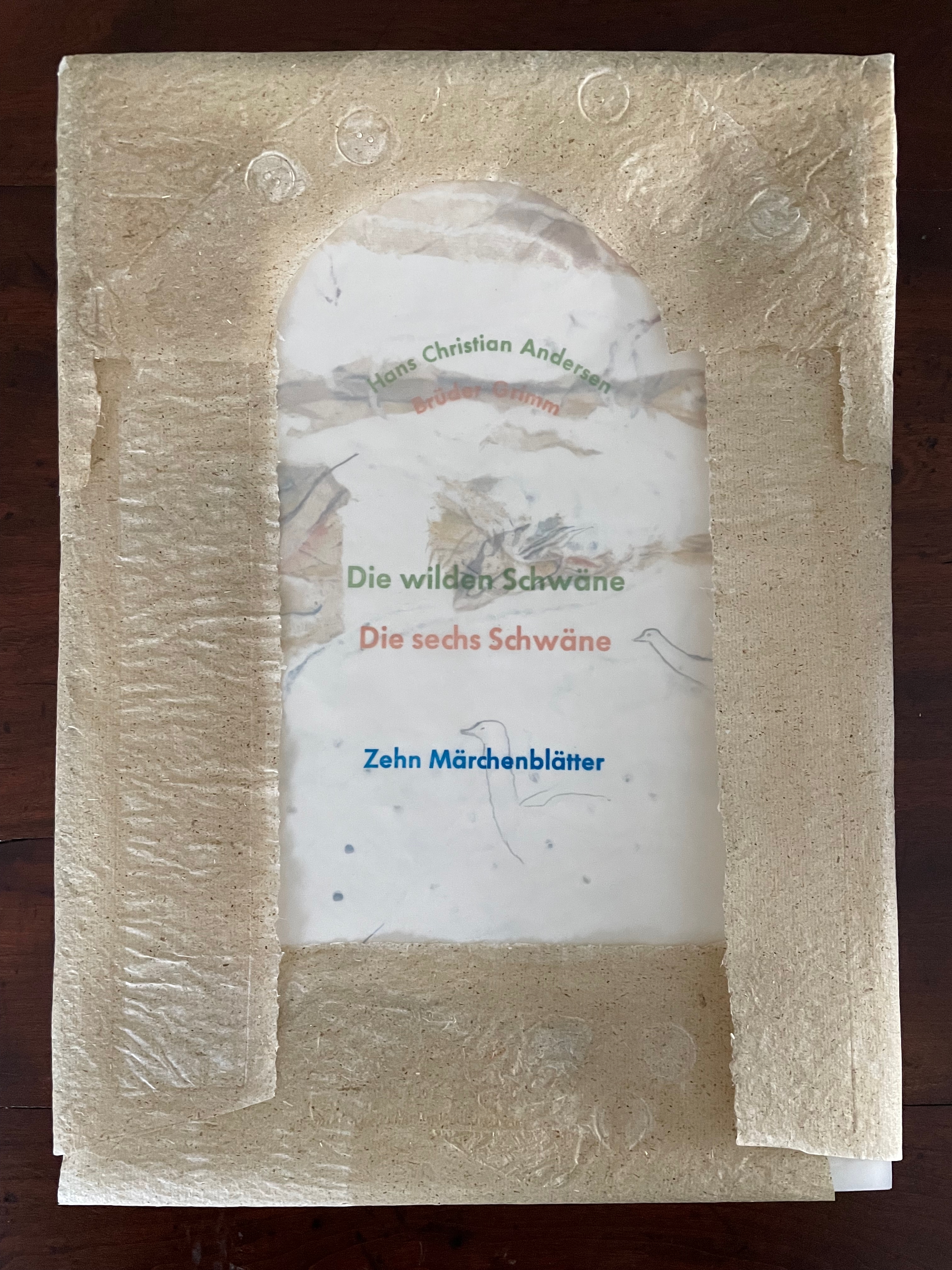

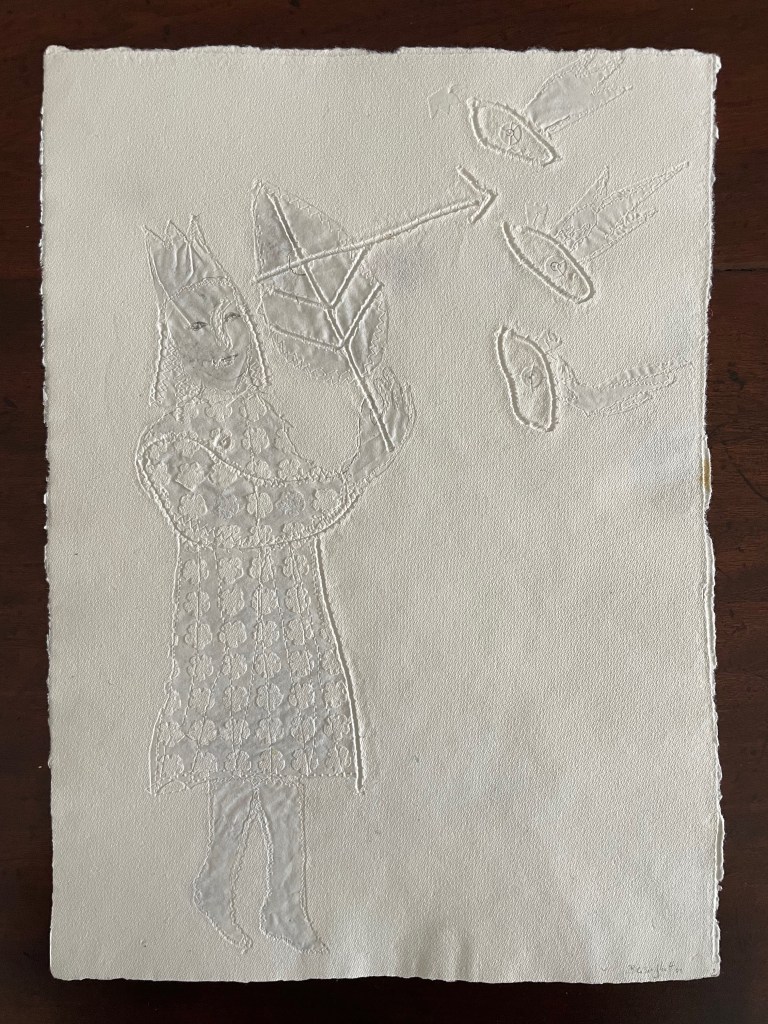

To match Elisa’s effort with stinging nettles, Beisinghoff enlisted the collaboration of Johannes Follmer, the owner of a paper mill. Together they obtained cultivated stinging nettles from the Institute for Applied Botany in Hamburg, cut the fibers, left them to rot, boiled them into a pulp, mixed that with water in a vat, scooped up layers in a sieve embroidered with illustrations, couched the sheets, then pressed and dried them into paper. Beisinghoff applied further drawings with a water jet, watercolor and pencil to the watermark-embossed sheets to illustrate aspects of the tale. To present the Andersen/Grimm “collage”, Beisinghoff had the type set and printed at the Gutenberg Museum. Andersen is printed in light green and Grimm in light red on seven numbered translucent sheets and interleaved with the nine folios of paper art (two more translucent sheets carry the cover page and colophon). To wrap the folios together, Beisinghoff made an embossed chemise or “feather dress” of pure nettle fiber, which could represent Andersen’s description of the brothers’ blowing off each other’s feathers every evening when the sun has set or one of the shirts that their sister makes to break their spell.

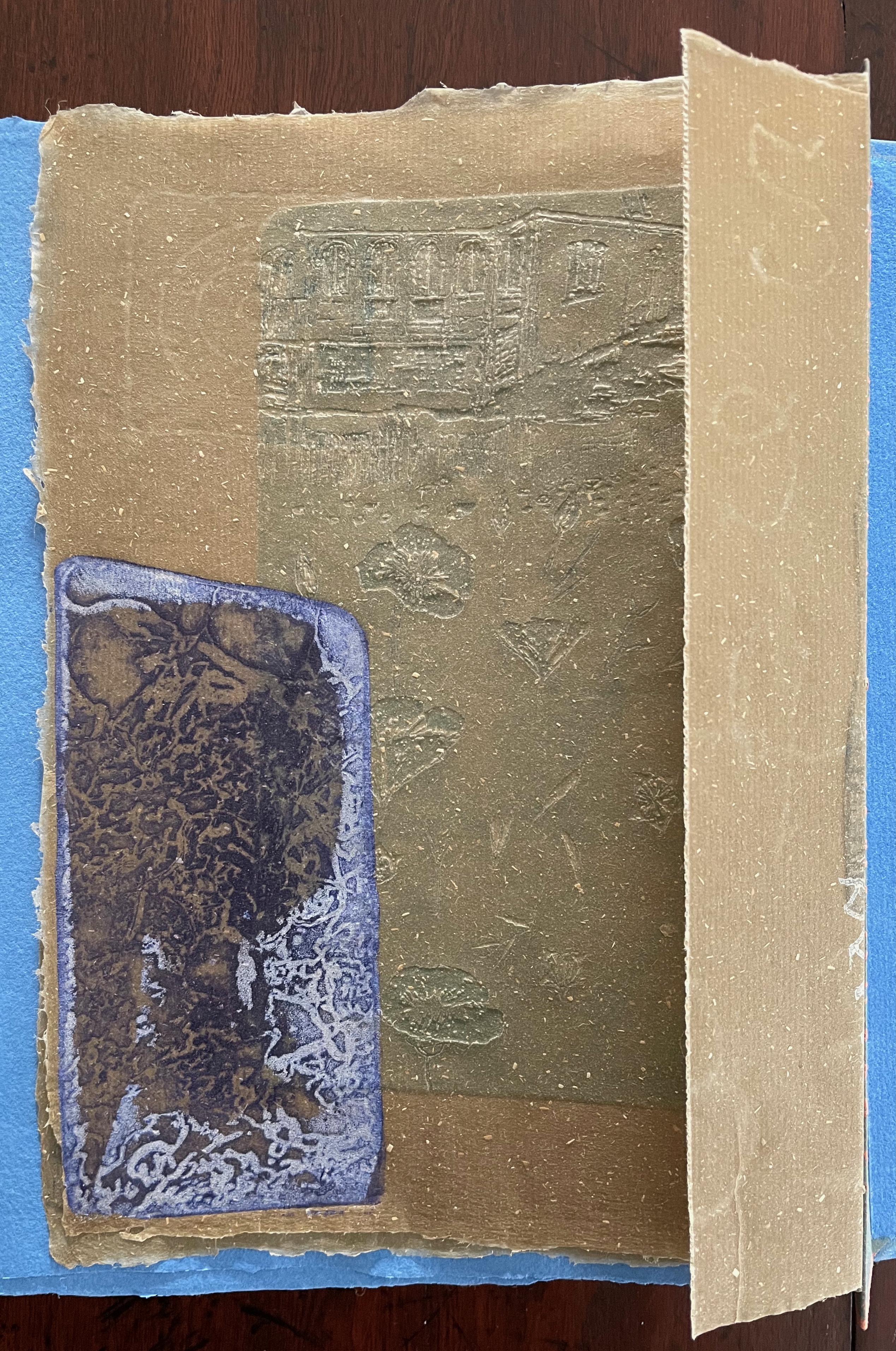

The “feather dress” of stinging nettle fiber.

“The King’s little daughter was standing in the cottage room, playing with a green leaf, for she had no other toys. She pricked a hole right through the leaf, looked up at the sun, and there it was, she saw the clear eyes of her brothers, but every time the warm rays of the sun shone on her cheeks, she thought of all their kisses.” Translation with DeepL.

“When she had fallen asleep, it seemed to her as if she were flying high through the air, and she met a fairy, beautiful and radiant, yet she looked very much like the old woman who had given her berries in the forest and told her about the swans with gold crowns on their heads.” Translation with DeepL.

“The swans swooped down to her and lowered themselves so that she could throw the shirts over them: and as she touched them, the swan skins fell off, and her brothers stood before her in the flesh, fresh and beautiful.” Translation with DeepL.

“Barbara Beisinghoff (head in the background) covers the frame with this transparent, embroidered and sewn gauze, which is used to scoop and emboss her nettle papers. This is how her large-format watermark illustrations end up on the sheets.” Translation with DeepL.

Peter Holle. 30 August 2001. Frankfurter Rundschau. Photo: Oliver Weiner.

This art by watermarking recalls that of other artists in the collection: Fred Siegenthaler and Gangolf Ulbricht, in particular. The technique of pulp painting also finds other practitioners in the collection: Pat Gentenaar-Torley, John Gerard, Helen Hiebert, Tim Mosely, Maria G. Pisano, Taller Leñateros, Claire Van Vliet and Maria Welch. Beisinghoff’s blend of embroidered watermarks, waterjet marking and pulp painting, however, creates a bas relief effect that is echoed only in the collection’s works by Mosely, Taller Leñateros and Van Vliet, albeit achieved differently. These workings of the substrate — as material, color, surface, and even narrative — with the workings of book structure is one of the more magical locations of book art. It is perfect for Beisinghoff’s metamorphical interpretation of the Andersen/Grimm fairy tale.

Further Reading

“The First Seven Books of the Rijswijk Paper Biennial“. 10 October 2019. Books On Books Collection.

“Pat Gentenaar-Torley“. 8 October 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“John Gerard“. 13 August 2020. Books On Books Collection.

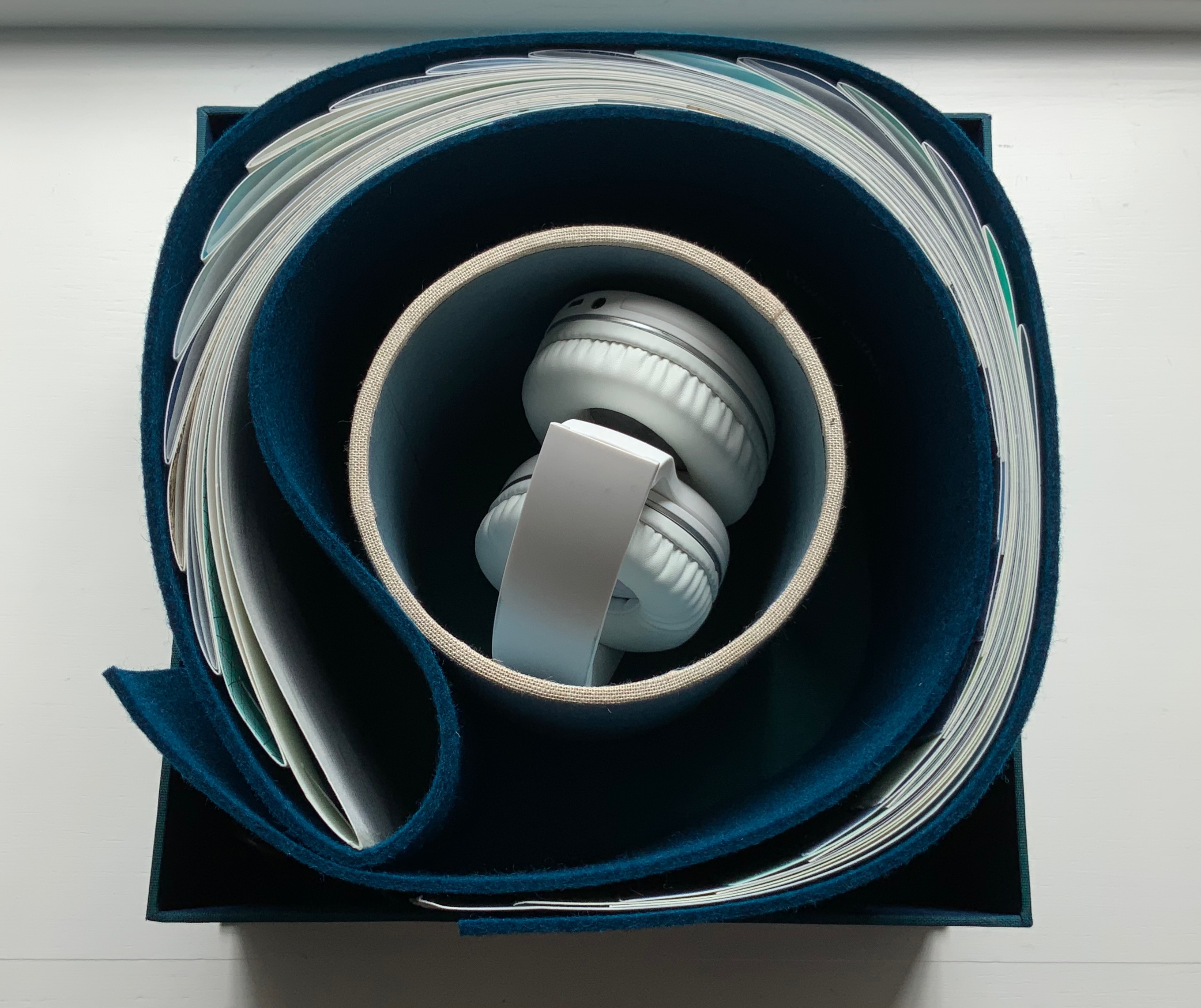

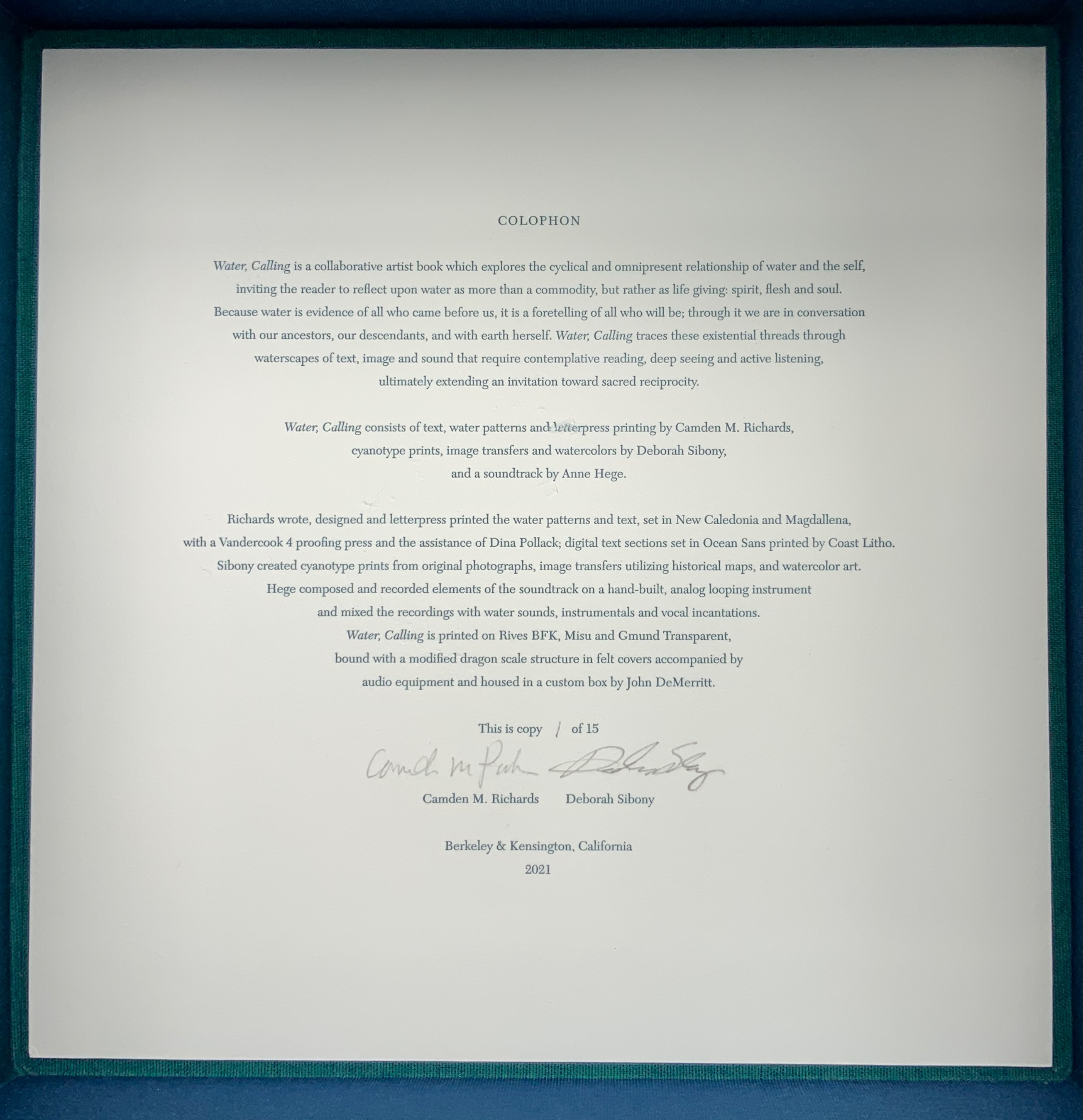

“Helen Hiebert“. 18 June 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Werner Pfeiffer and Anselm Kiefer“. 17 January 2015. Bookmarking Book Art.

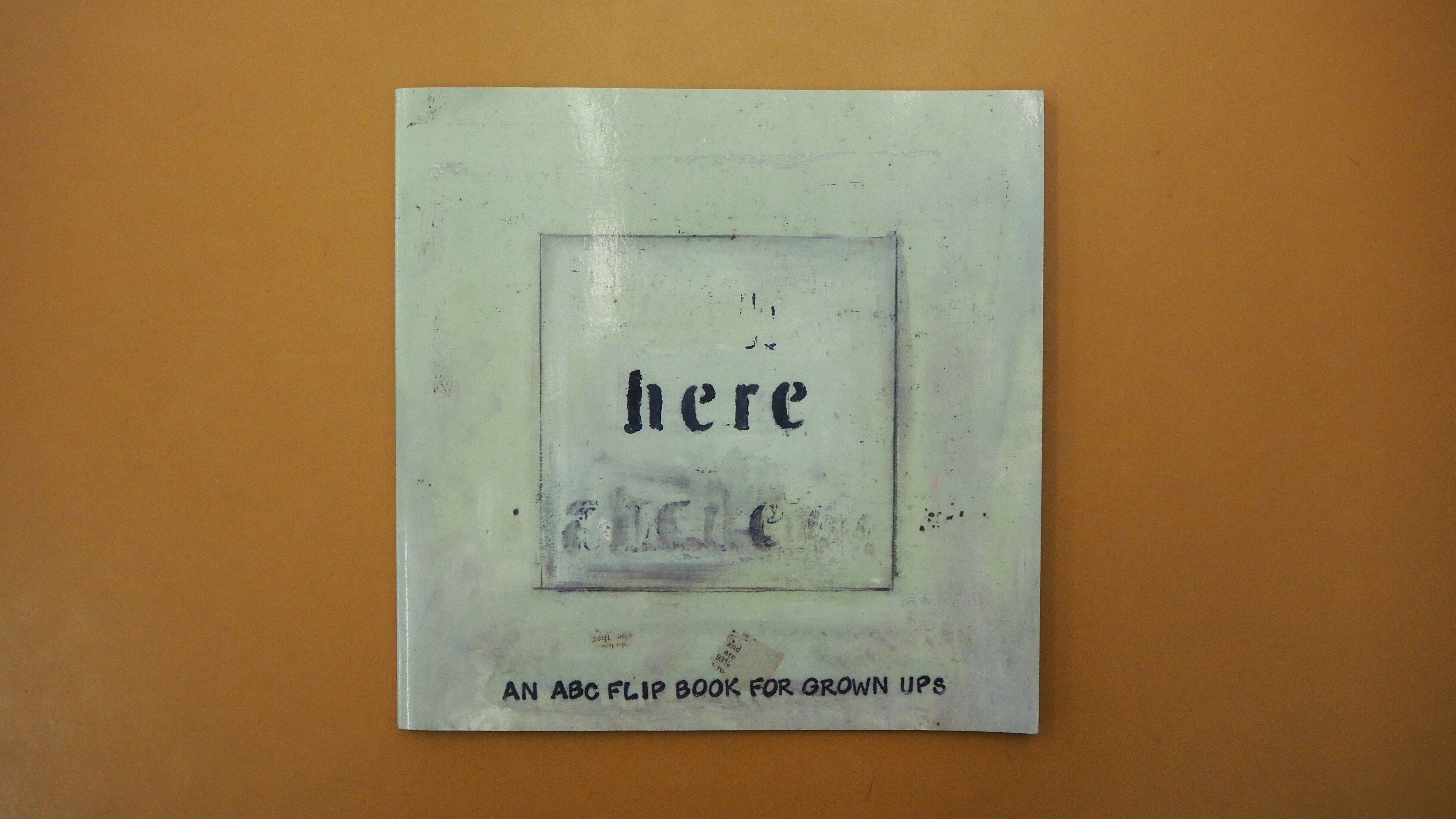

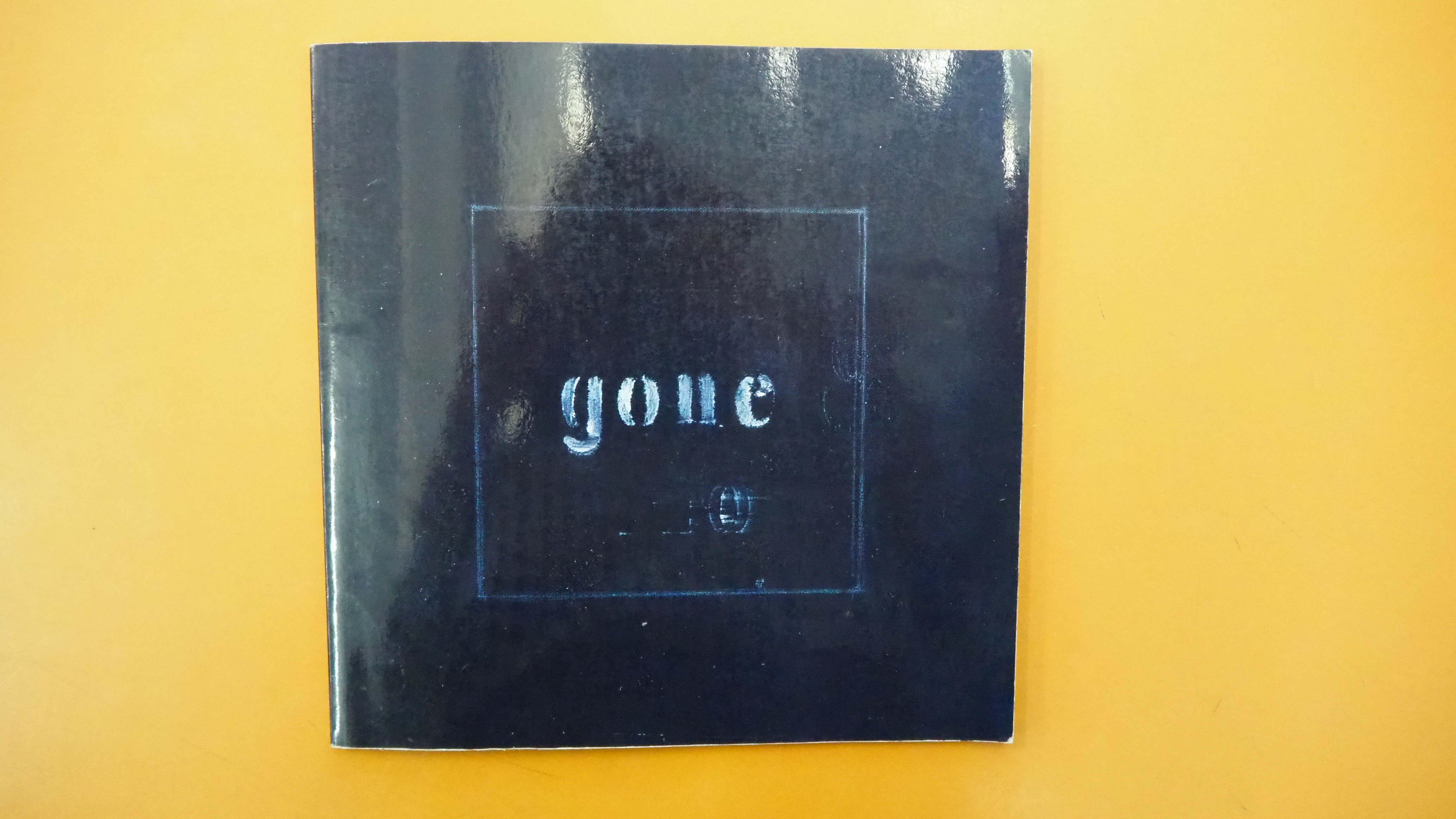

“Warja Lavater“. 23 December 2022. Books On Books Collection.

“Tatyana Mavrina“. 24 February 2023. Books On Books Collection.

“Tim Mosely“. 23 August 2024. Books On Books Collection.

“Maria G. Pisano“. 15 August 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Fred Siegenthaler“. 10 January 2021. Books On Books Collection.

“Taller Leñateros“. 19 November 2020. Books On Books Collection.

“Gangolf Ulbricht“. Books On Books Collection. In process.

Brentano, Clemens. 1970. Clemens Brentano’s Gesammelte Schriften. Edited by Christian Brentano. Bern: Herbert Lang. See also “Nach großem Leid“. Wikisource.

Fehn, Ann Clark. 1977. Change and Permanence : Gottfried Benn’s Text for Paul Hindemith’s Oratorio Das Unaufhörliche. Bern ; Peter Lang.

Feneyrou, Laurent. 2009.”Survey of works by Bernd Alois Zimmermann“. ircam. Paris: Centre Pompidou.

Fuchs, Leonhart, Klaus Dobat, and Werner Dressendörfer. 2016. The New Herbal of 1543 = New KreüTerbuch. Complete coloured edition. Köln: Taschen.

Holle, Peter. 30 August 2001. “Sie schöpft aus Brennnesseln Papier und druckt daraus ein Buch”. Frankfurter Rundschau. Photo: Oliver Weiner.

Rienäcker, Gerd. 2012. “Musizieren über Traditionen. Die Soldaten von Bernd Alois Zimmermann, Einstein von Paul Dessau” in Musik und kulturelle Identität, Vol. 2, edited by Detlef Altenburg and Rainer Bayreuther. Kassel: Bärenreiter-Verlag.

Thompson, D’Arcy Wentworth. 1917. On Growth and Form . Cambridge: University Press.