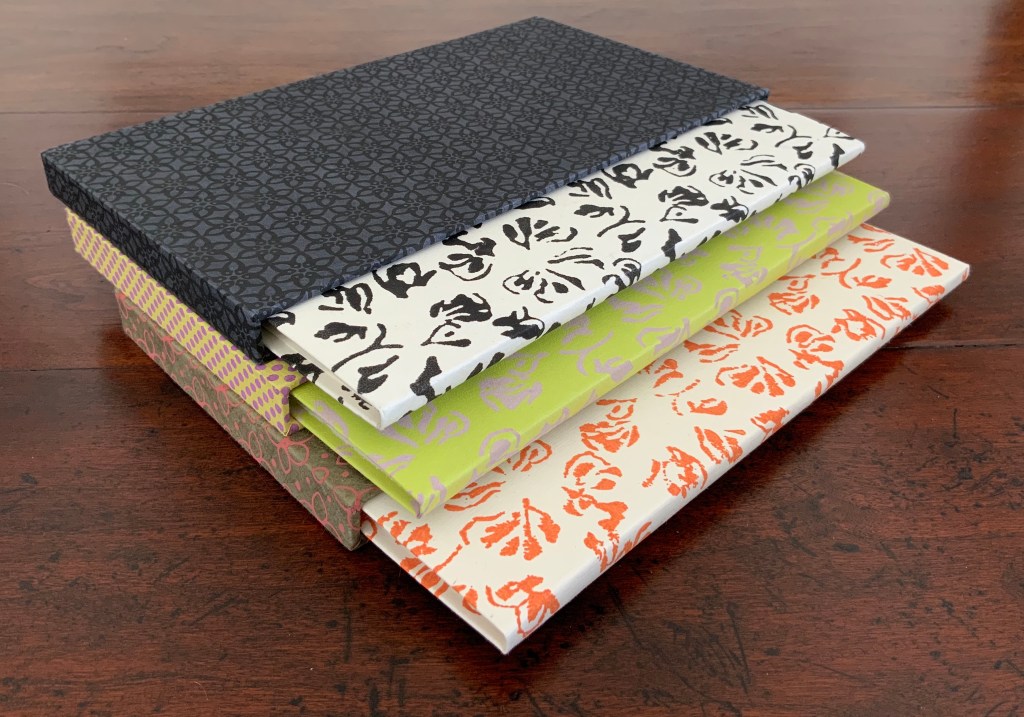

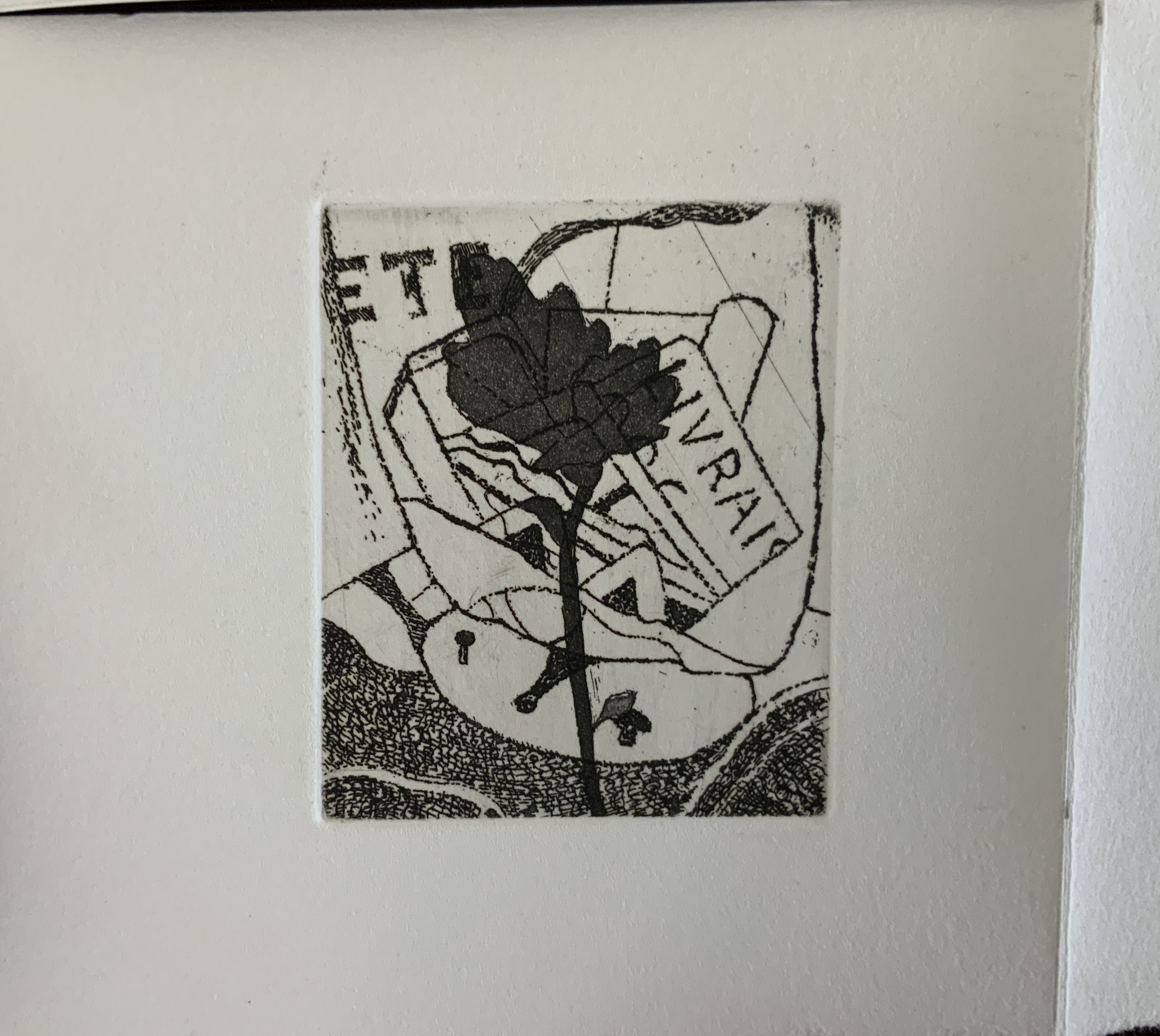

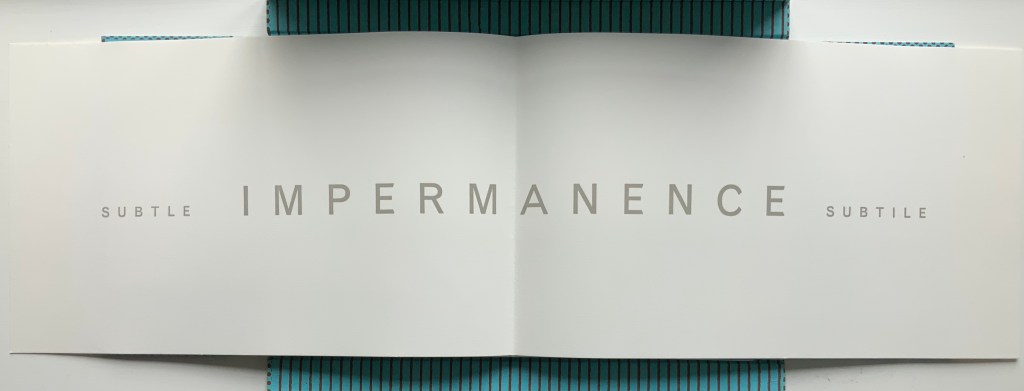

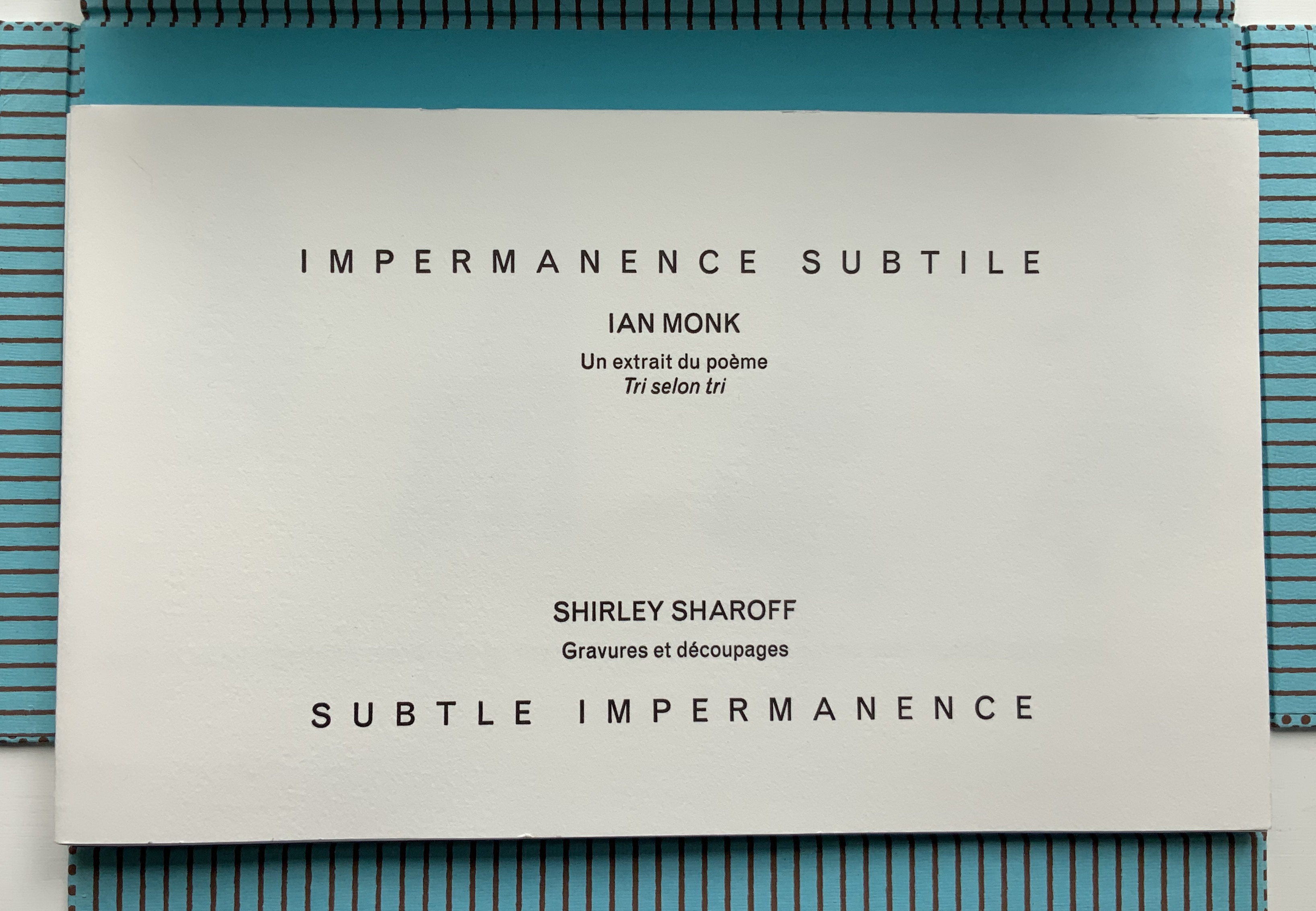

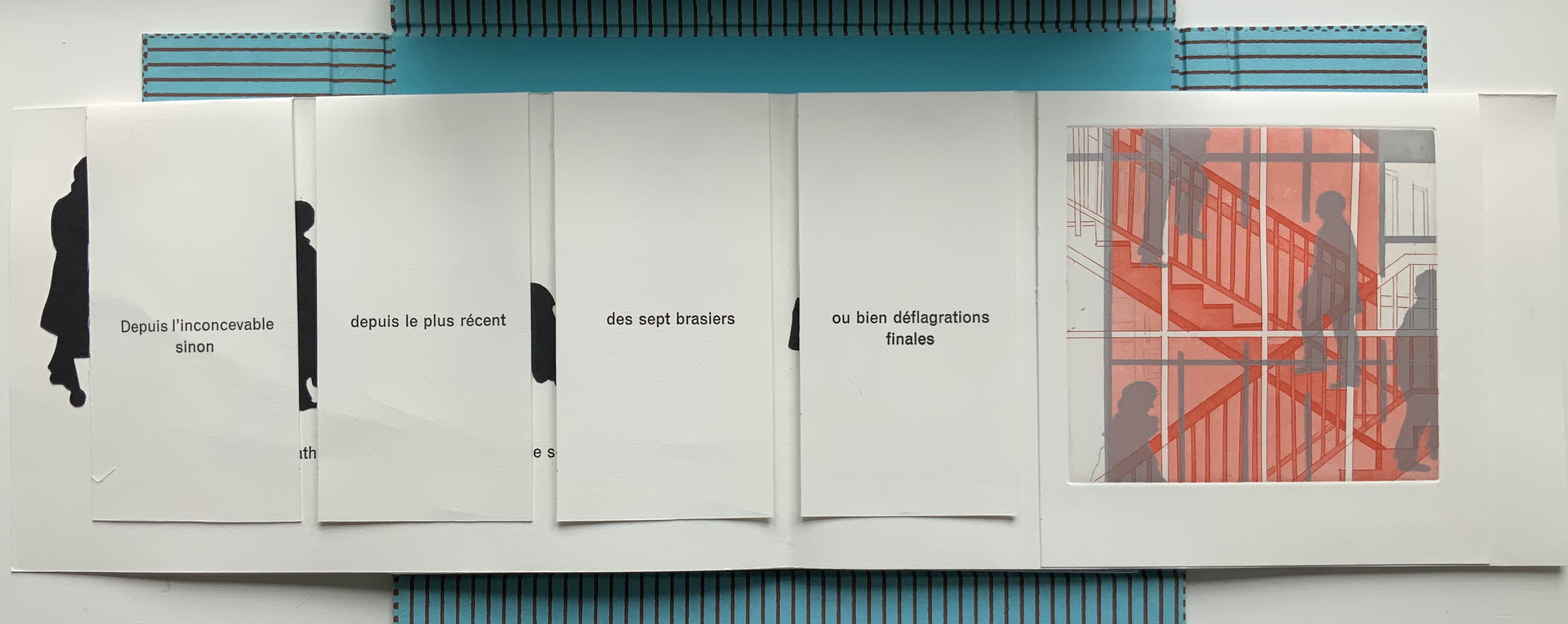

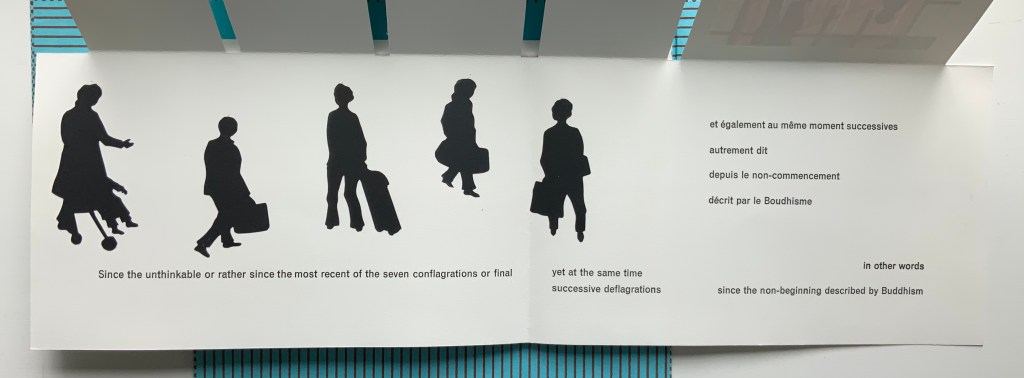

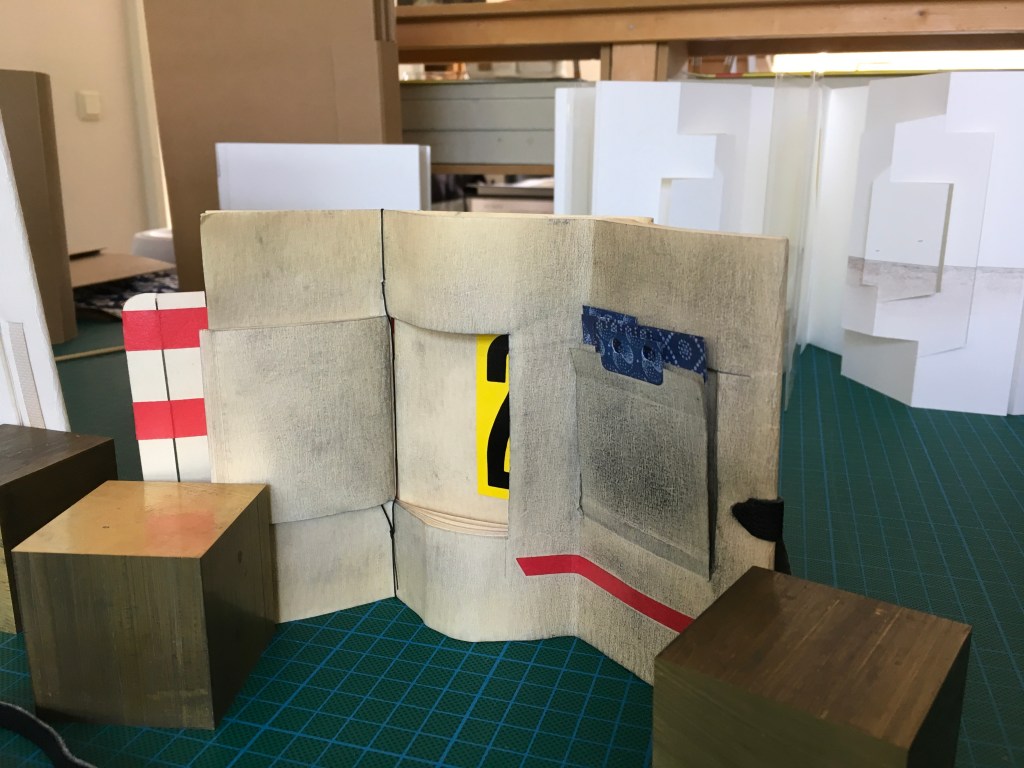

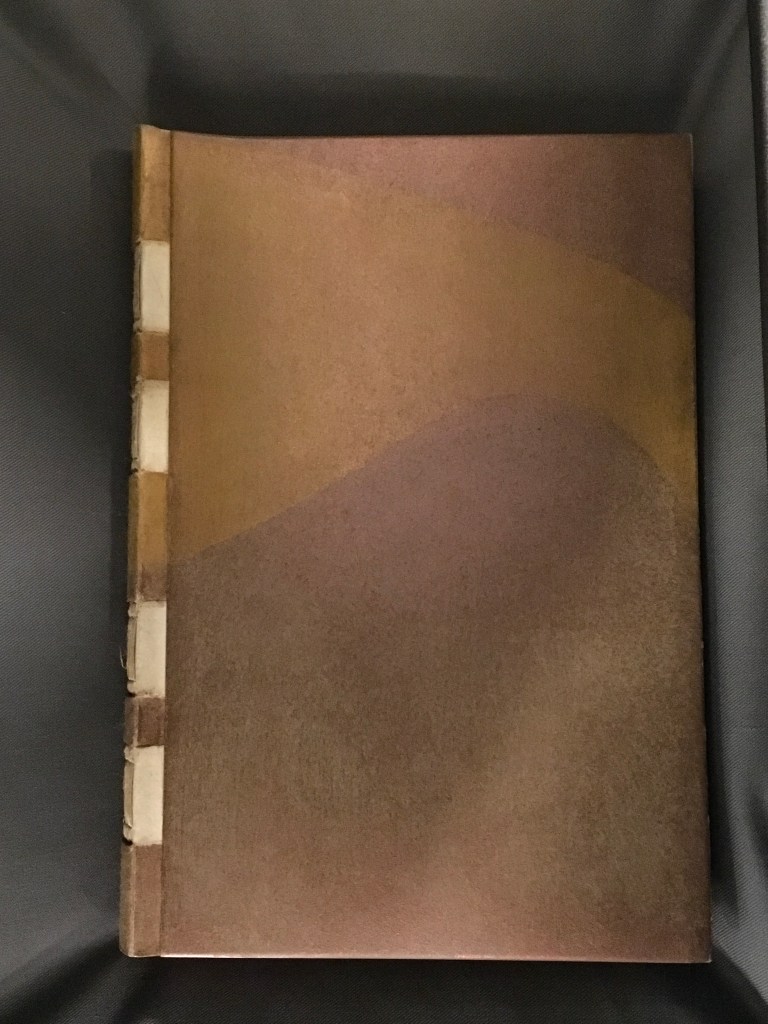

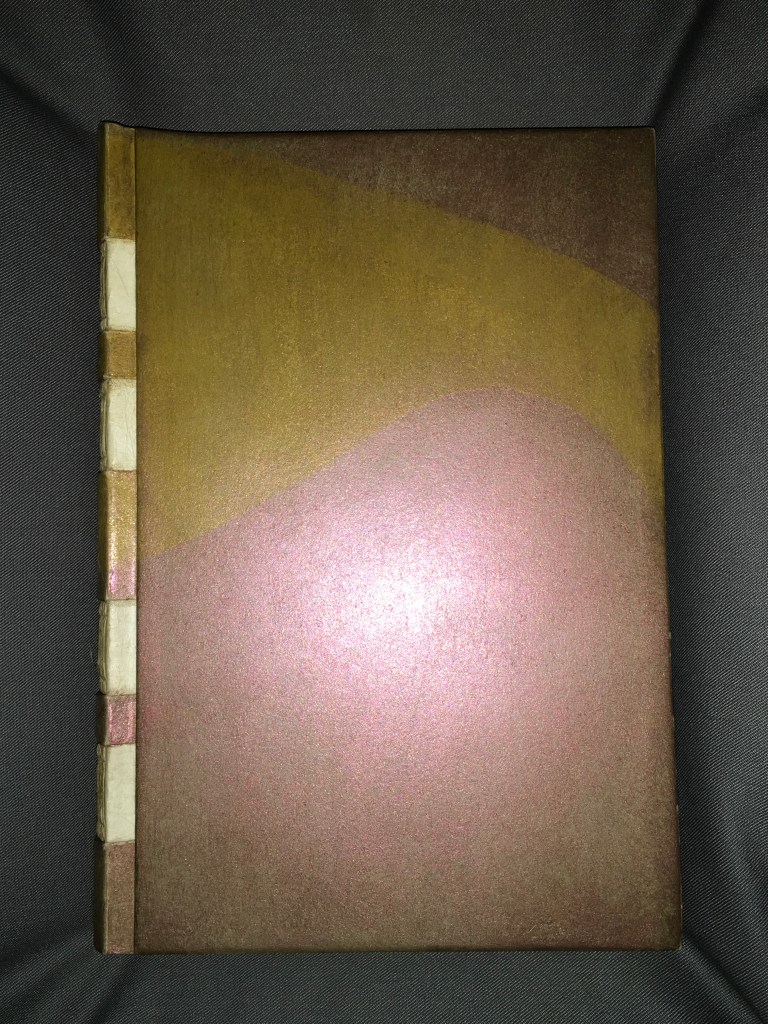

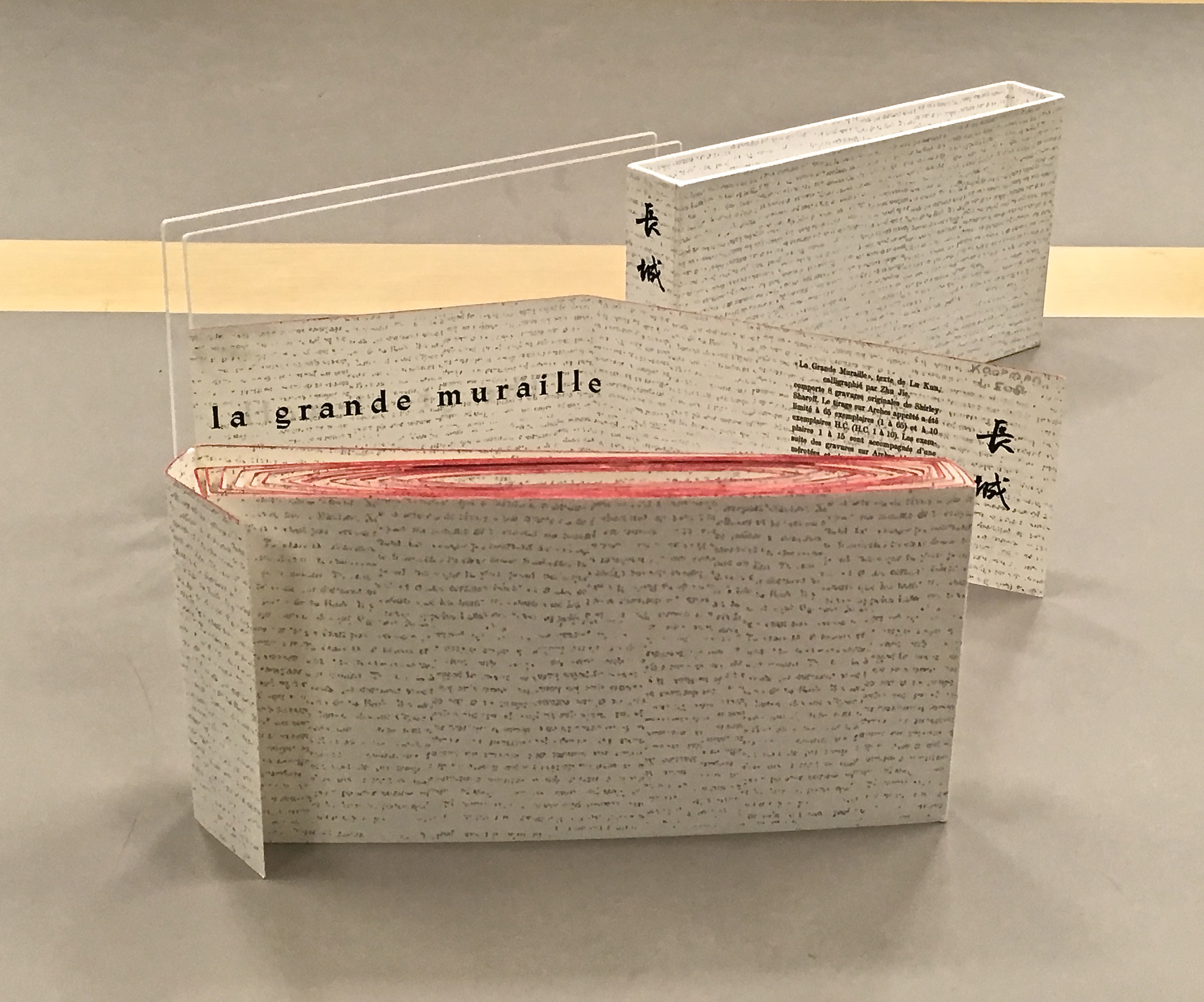

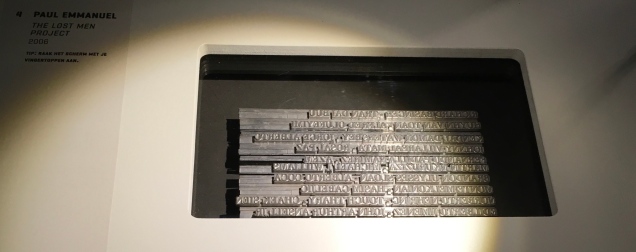

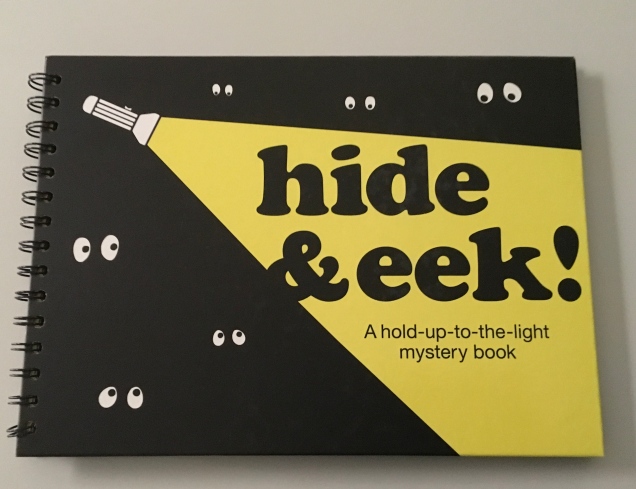

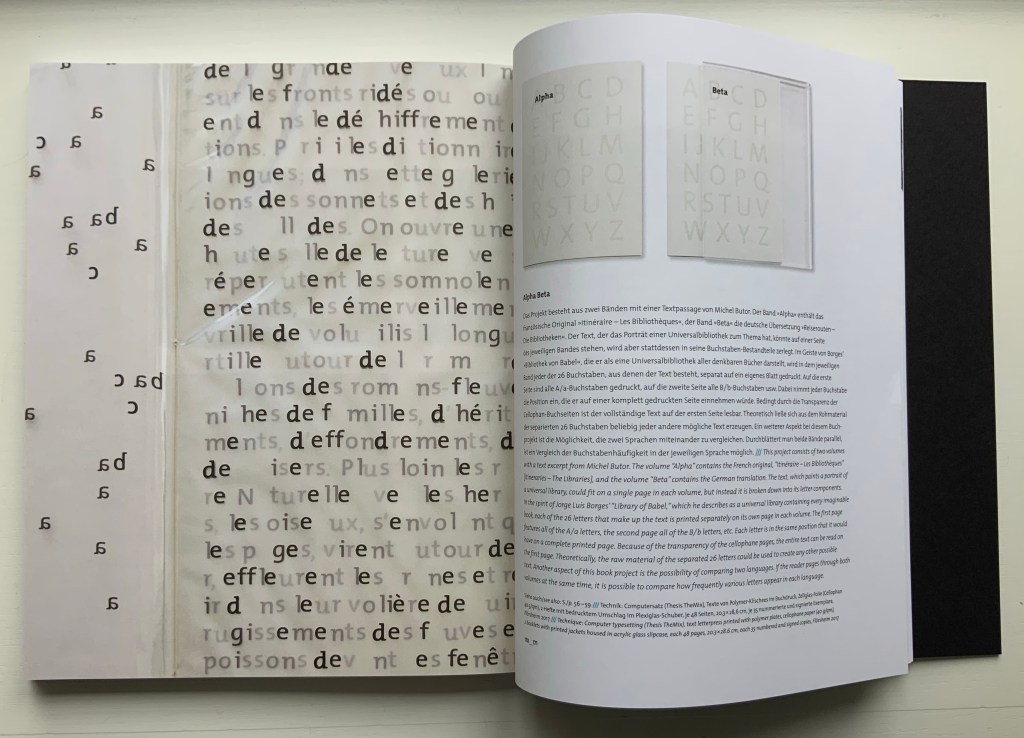

Alpha Beta (2017)

Alpha Beta (2017)

Ines von Ketelhodt, text by Michel Butor

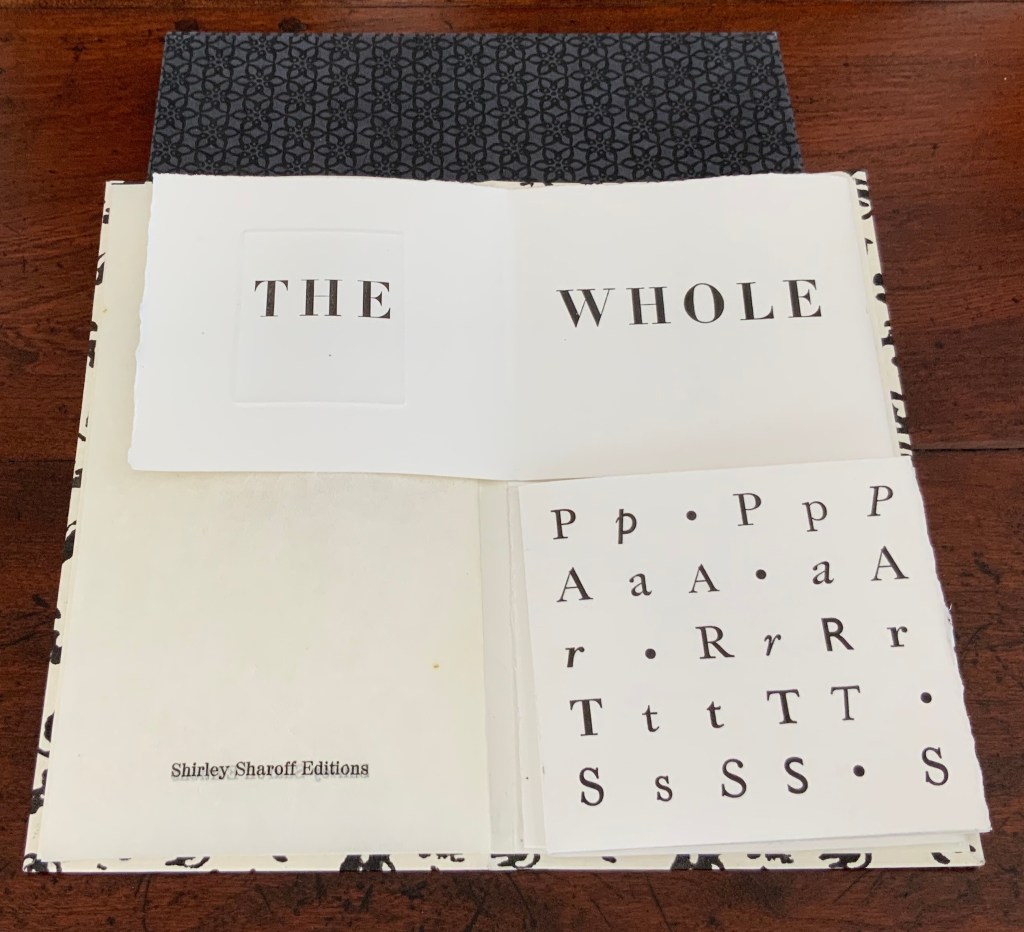

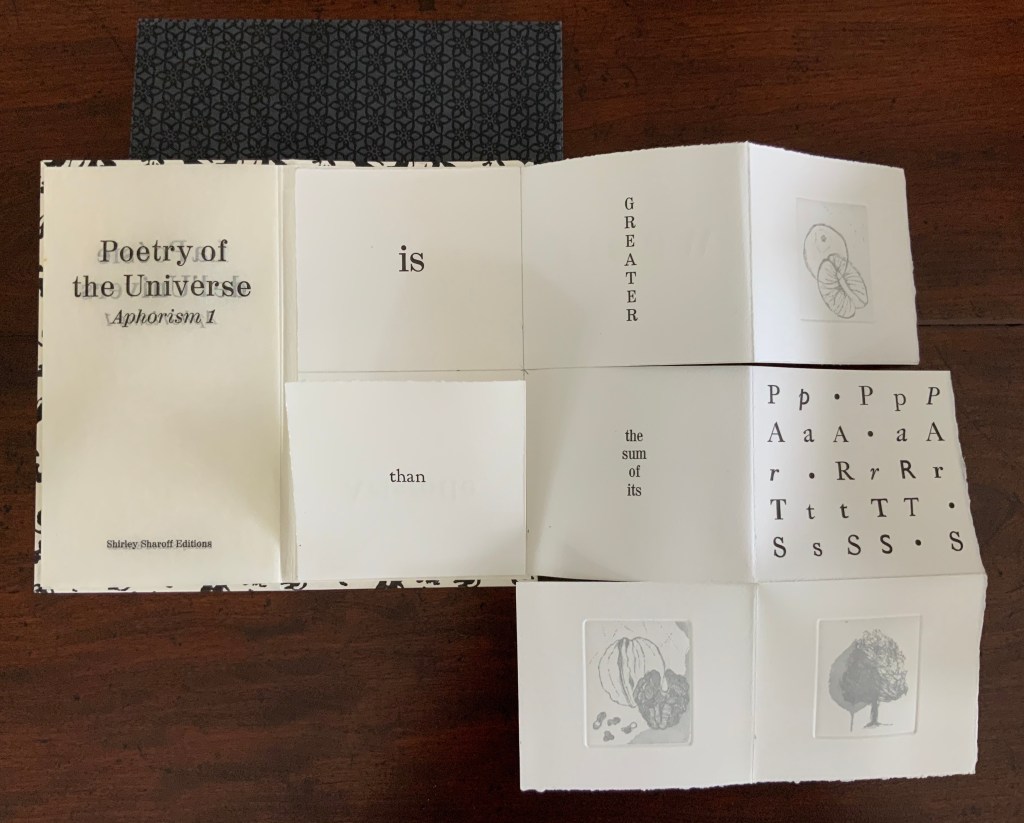

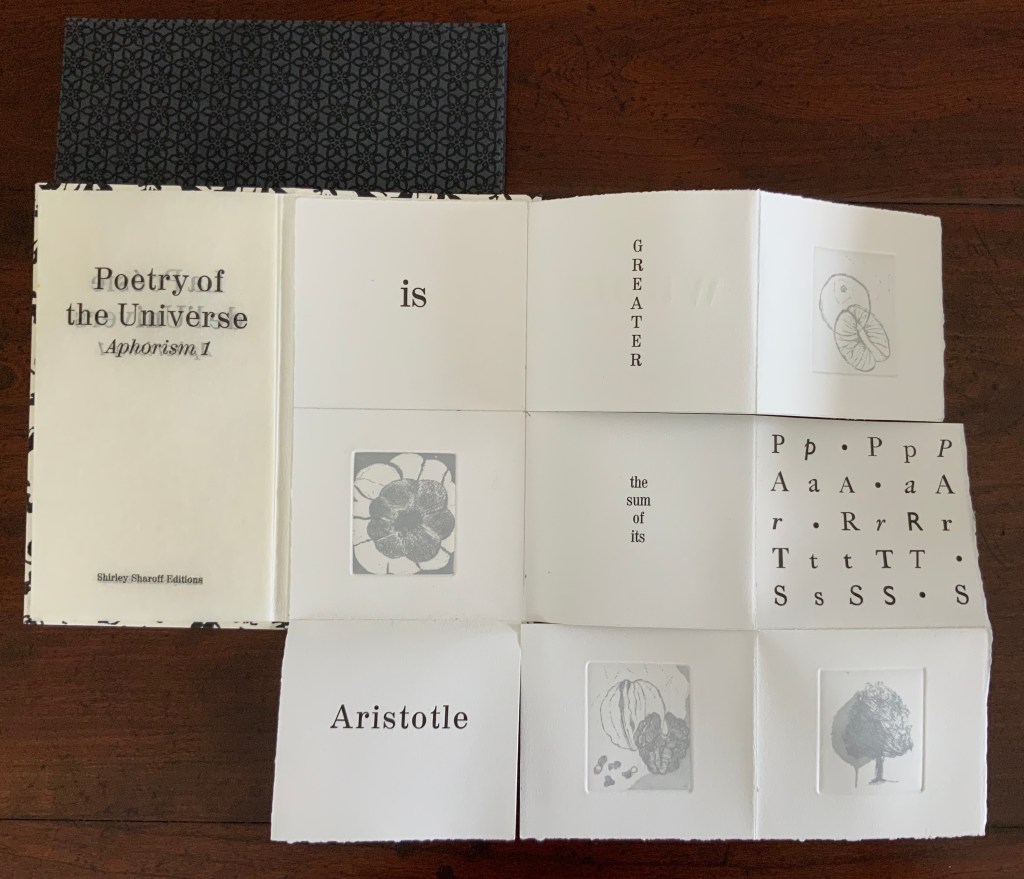

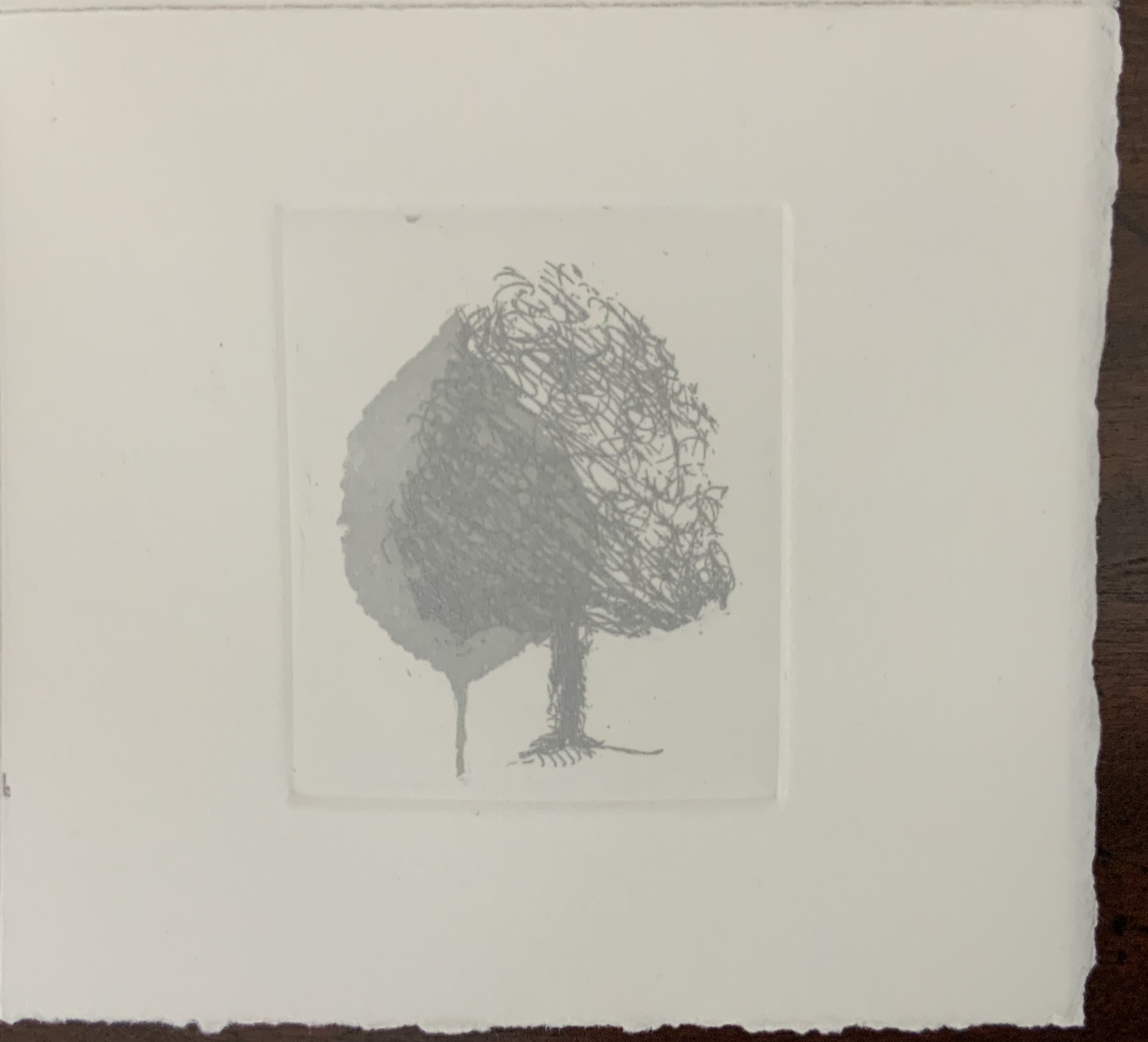

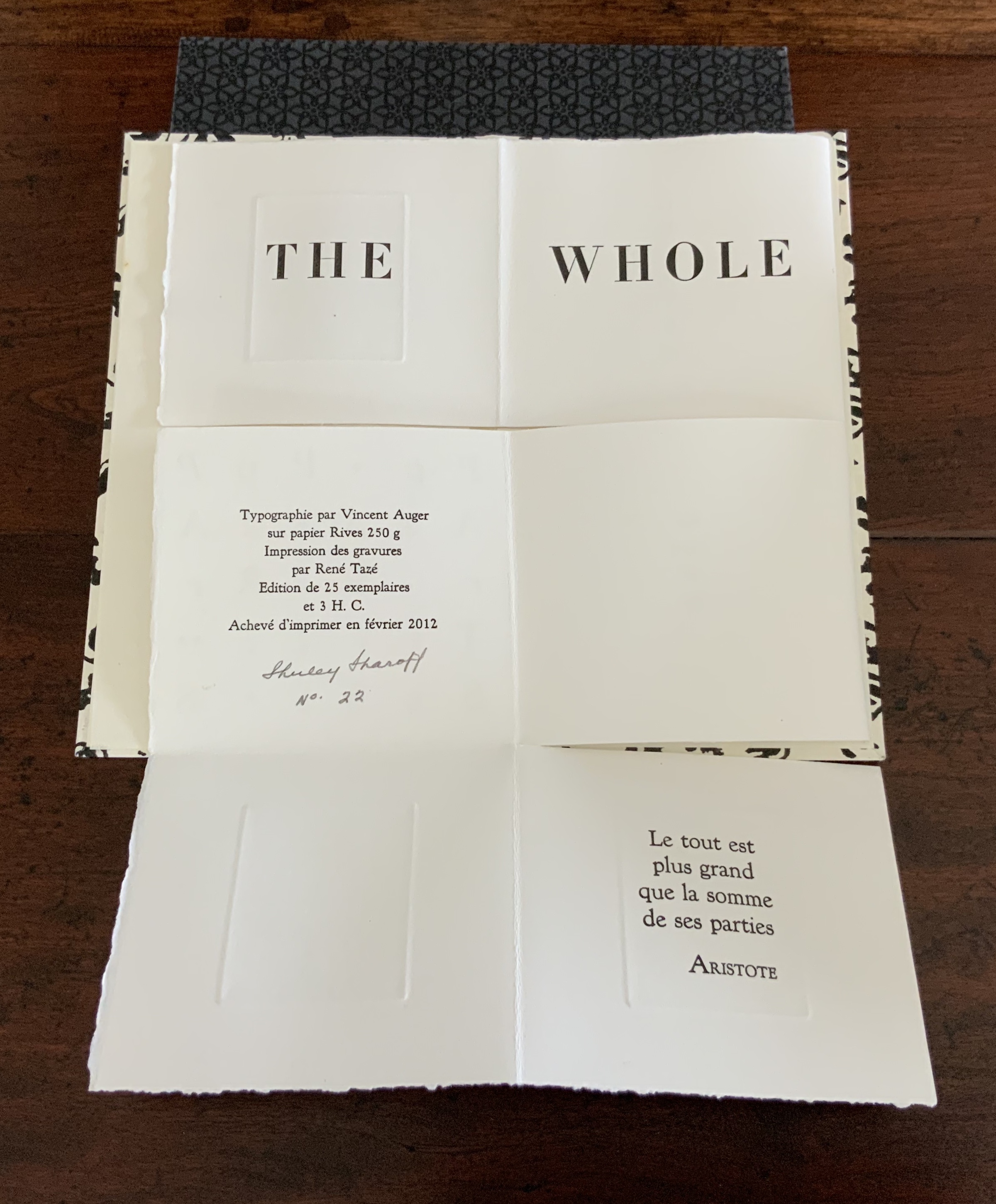

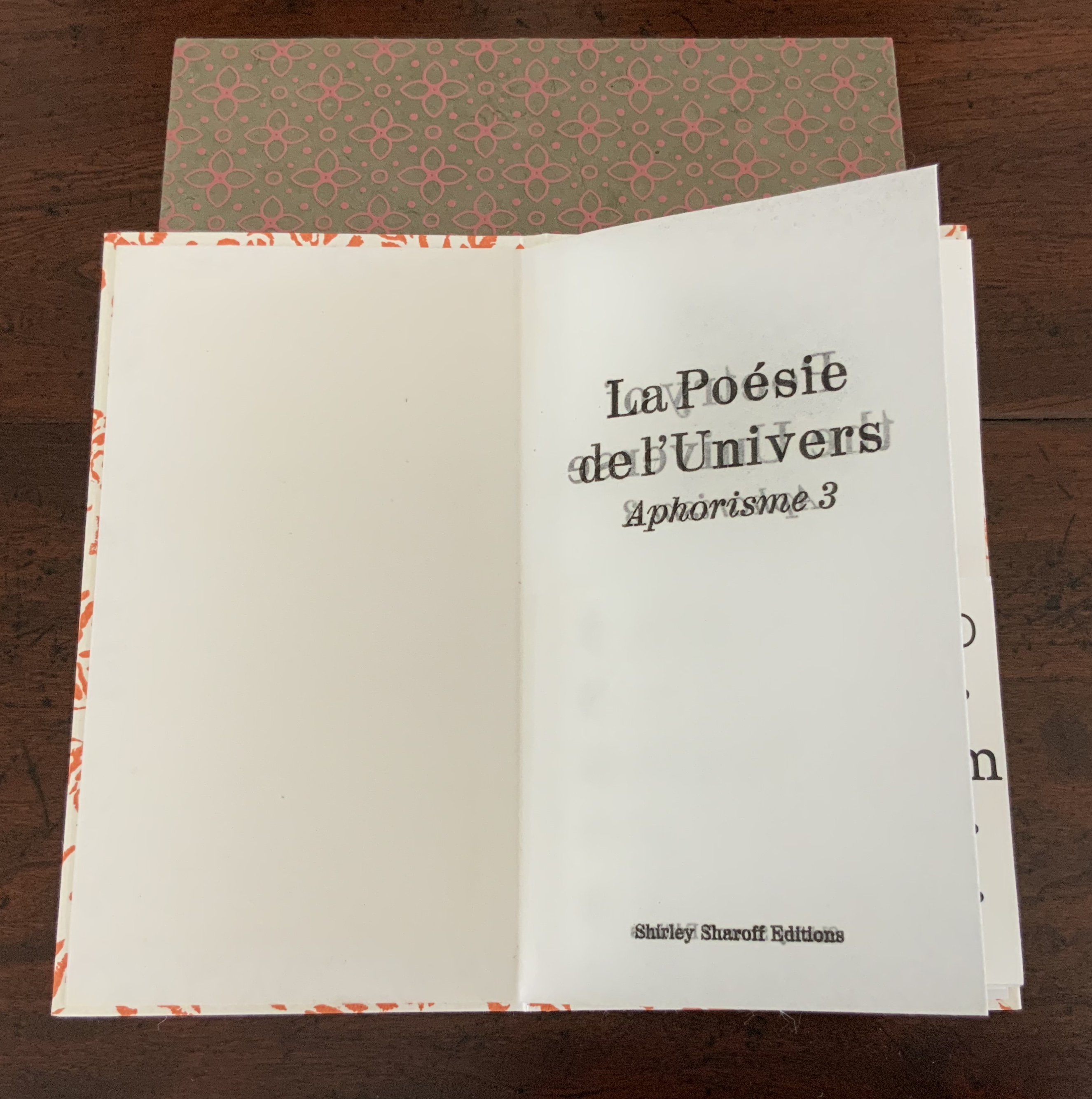

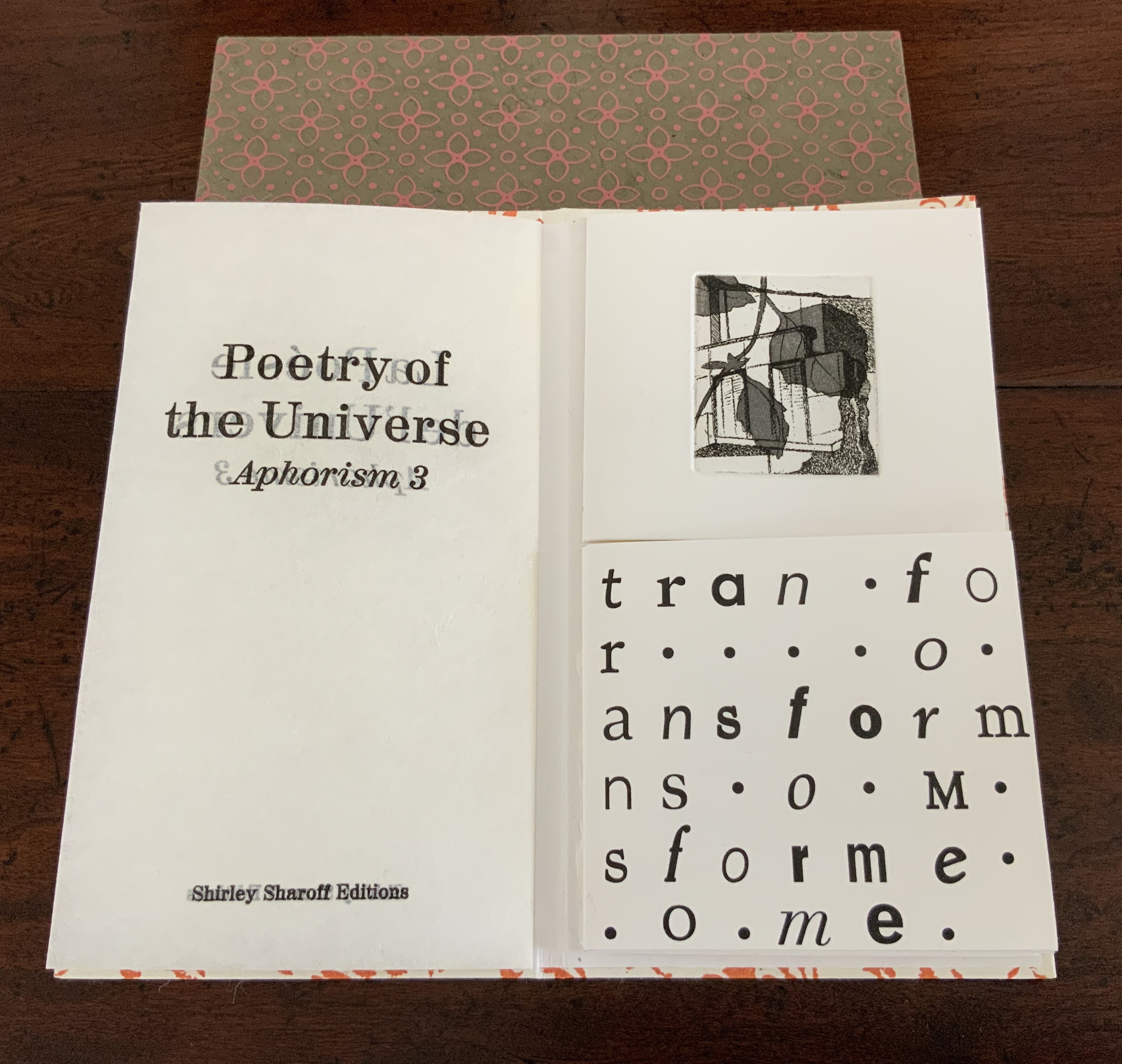

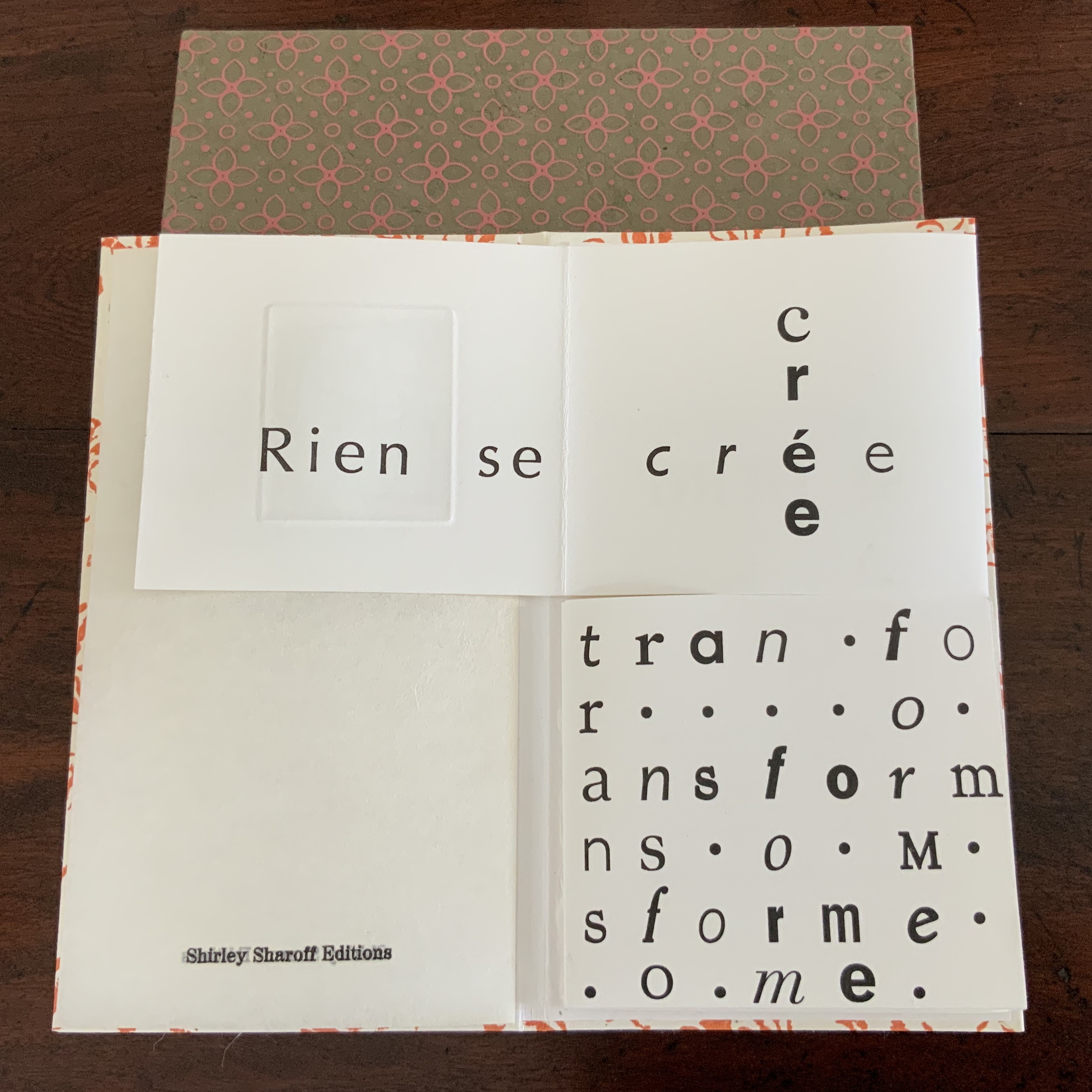

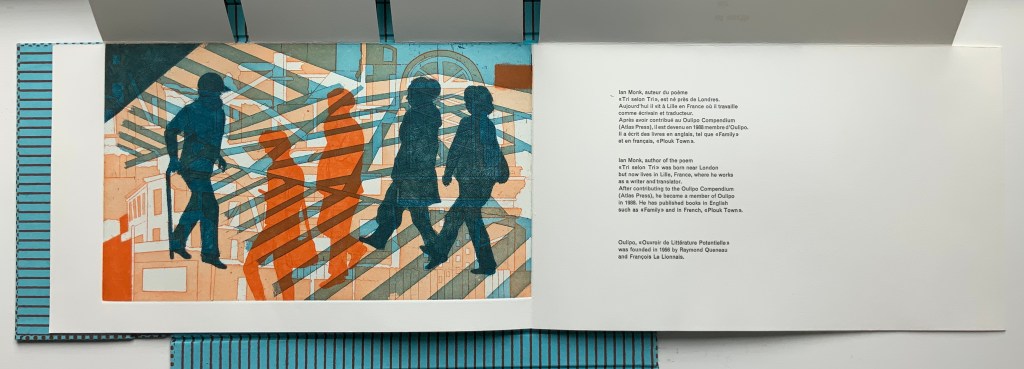

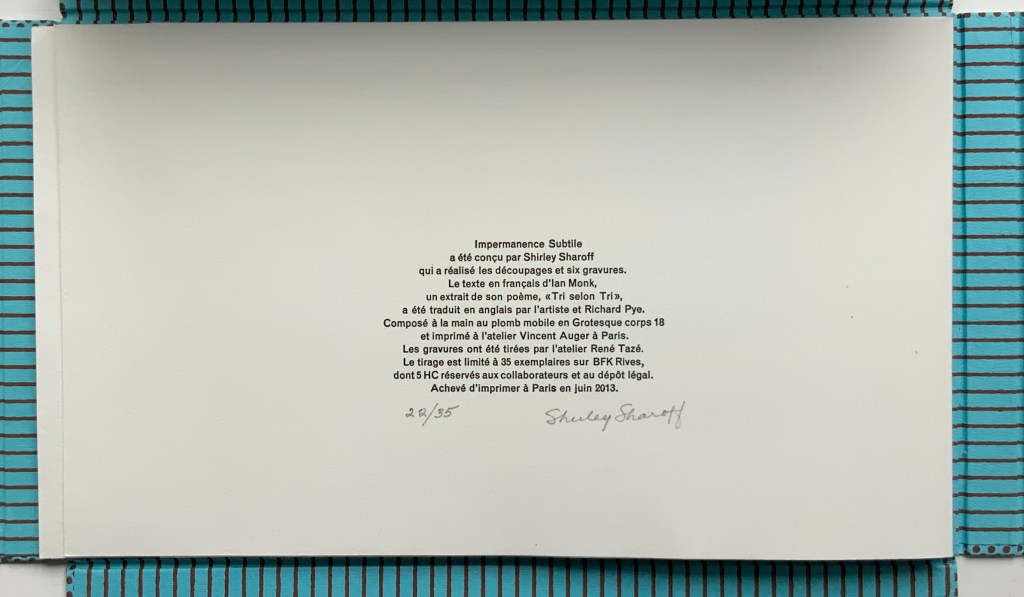

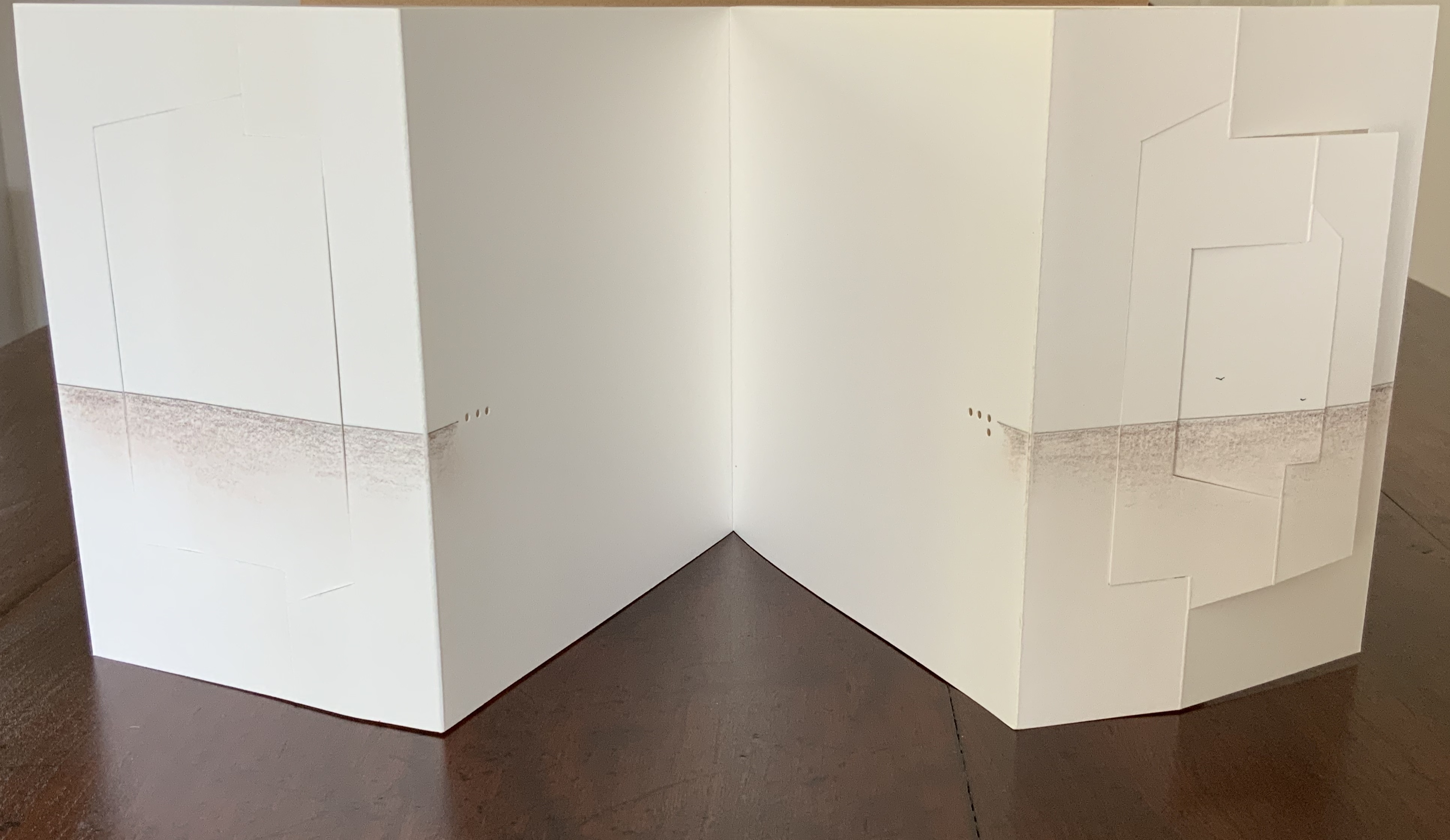

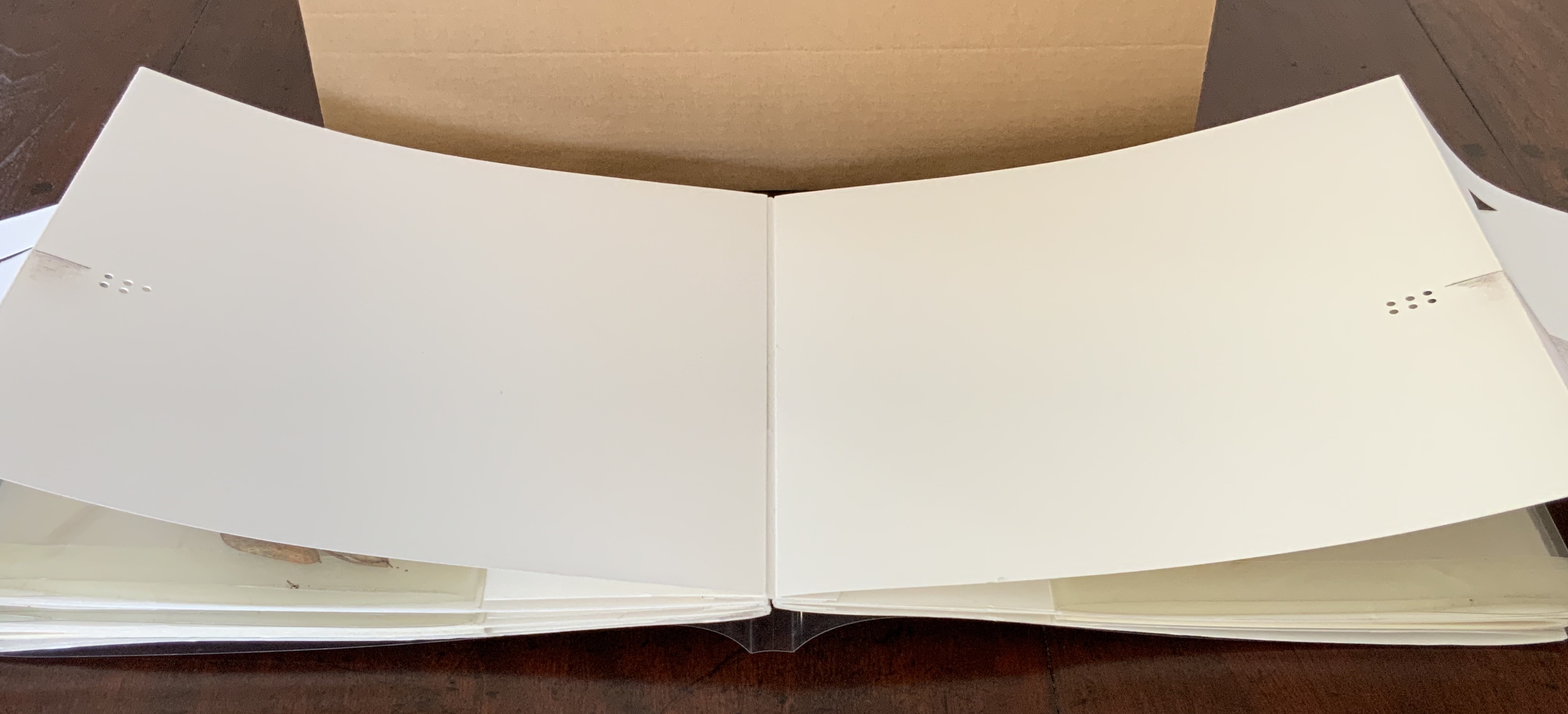

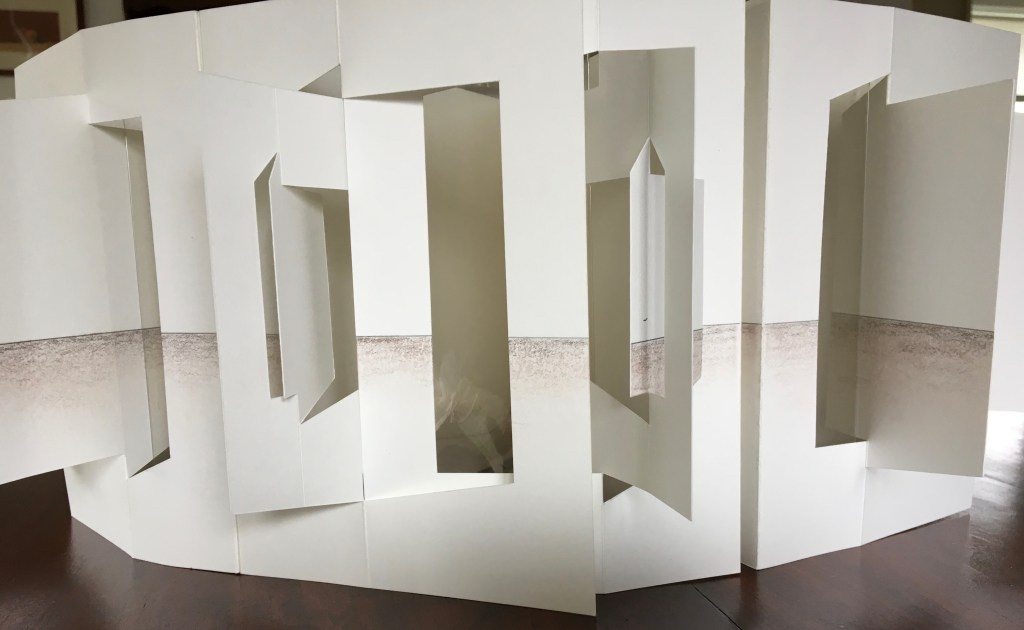

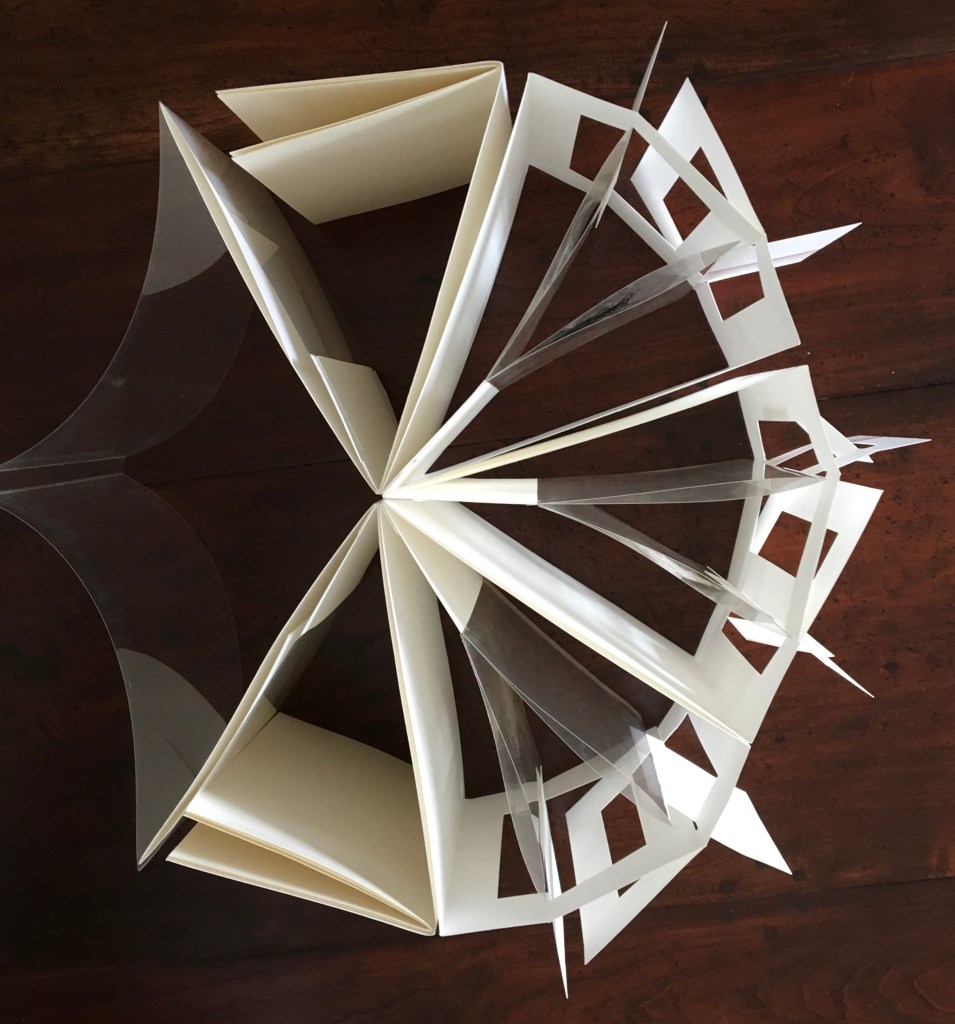

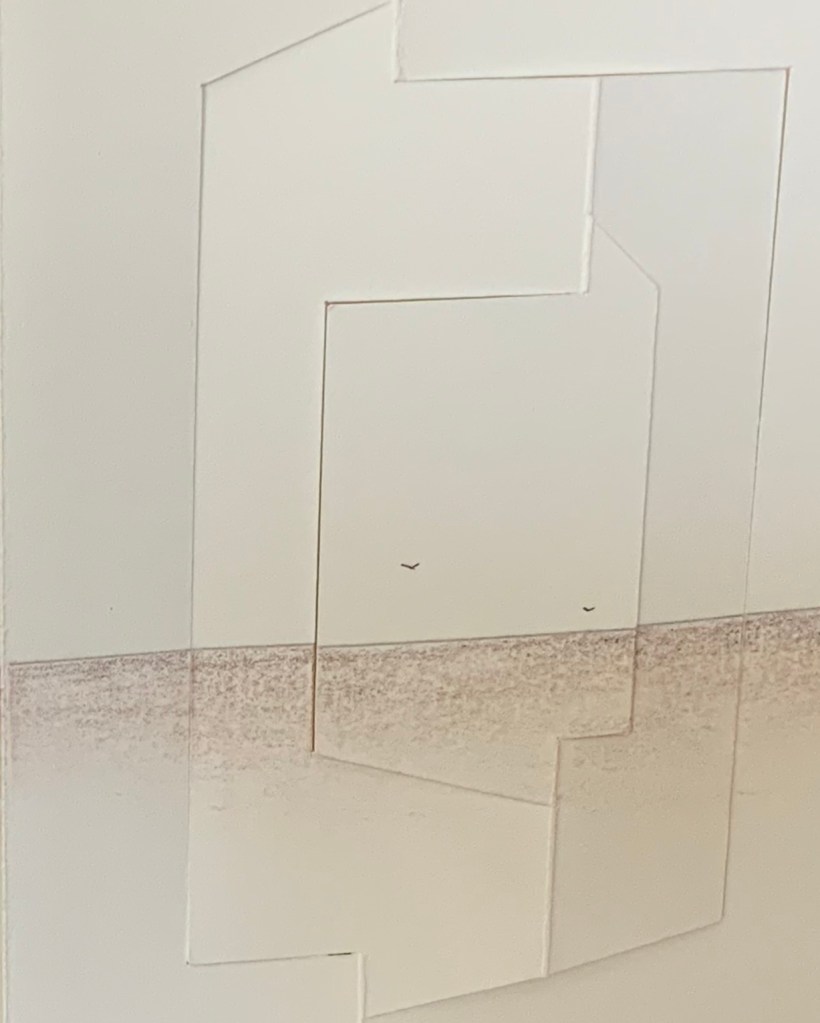

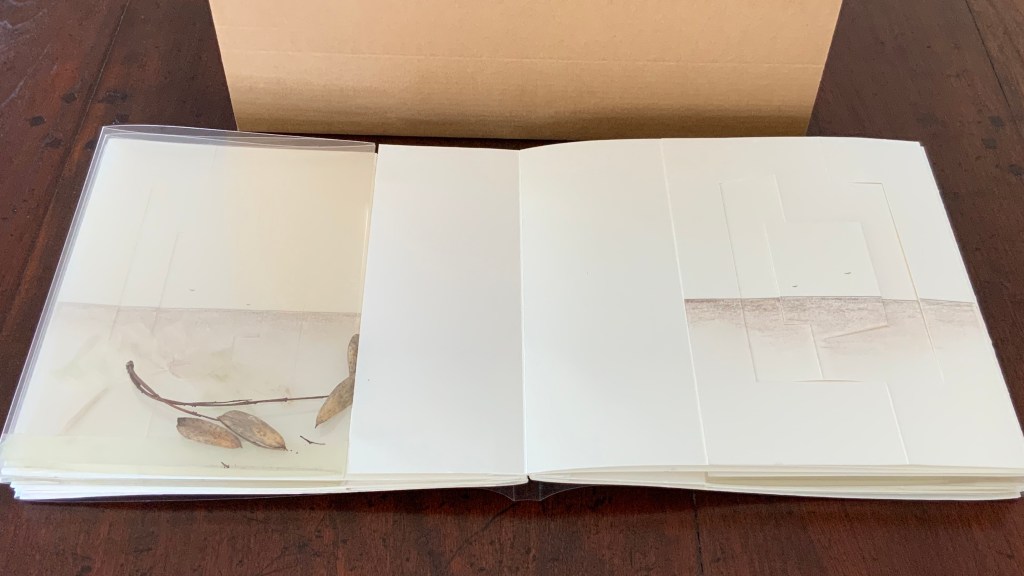

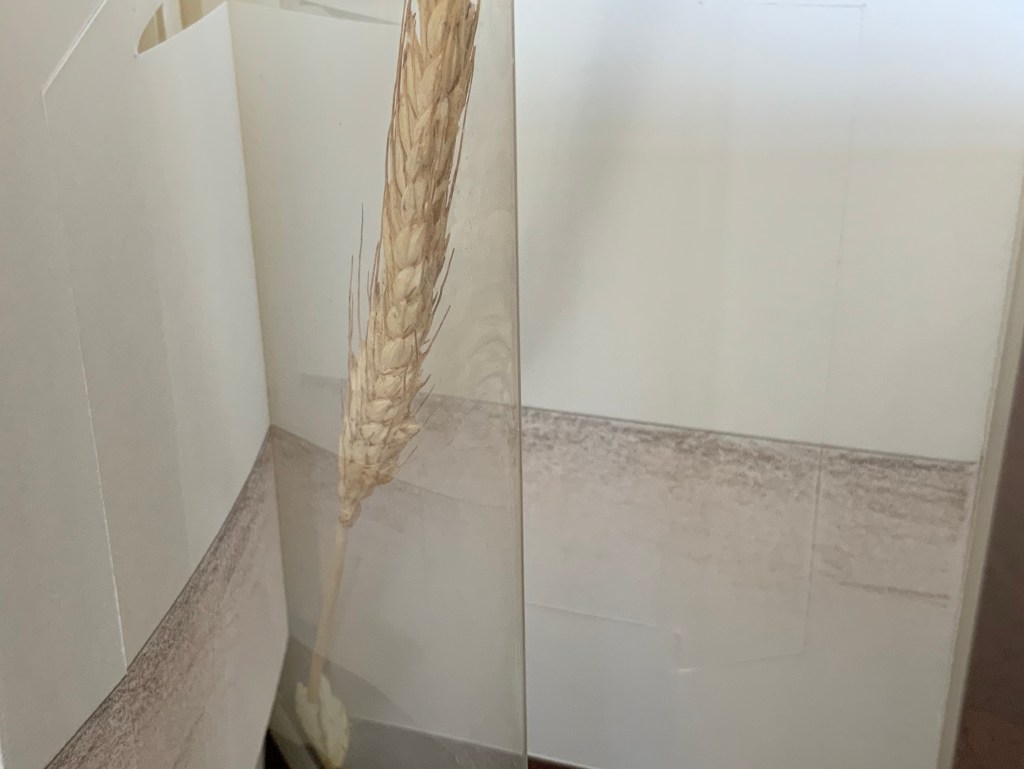

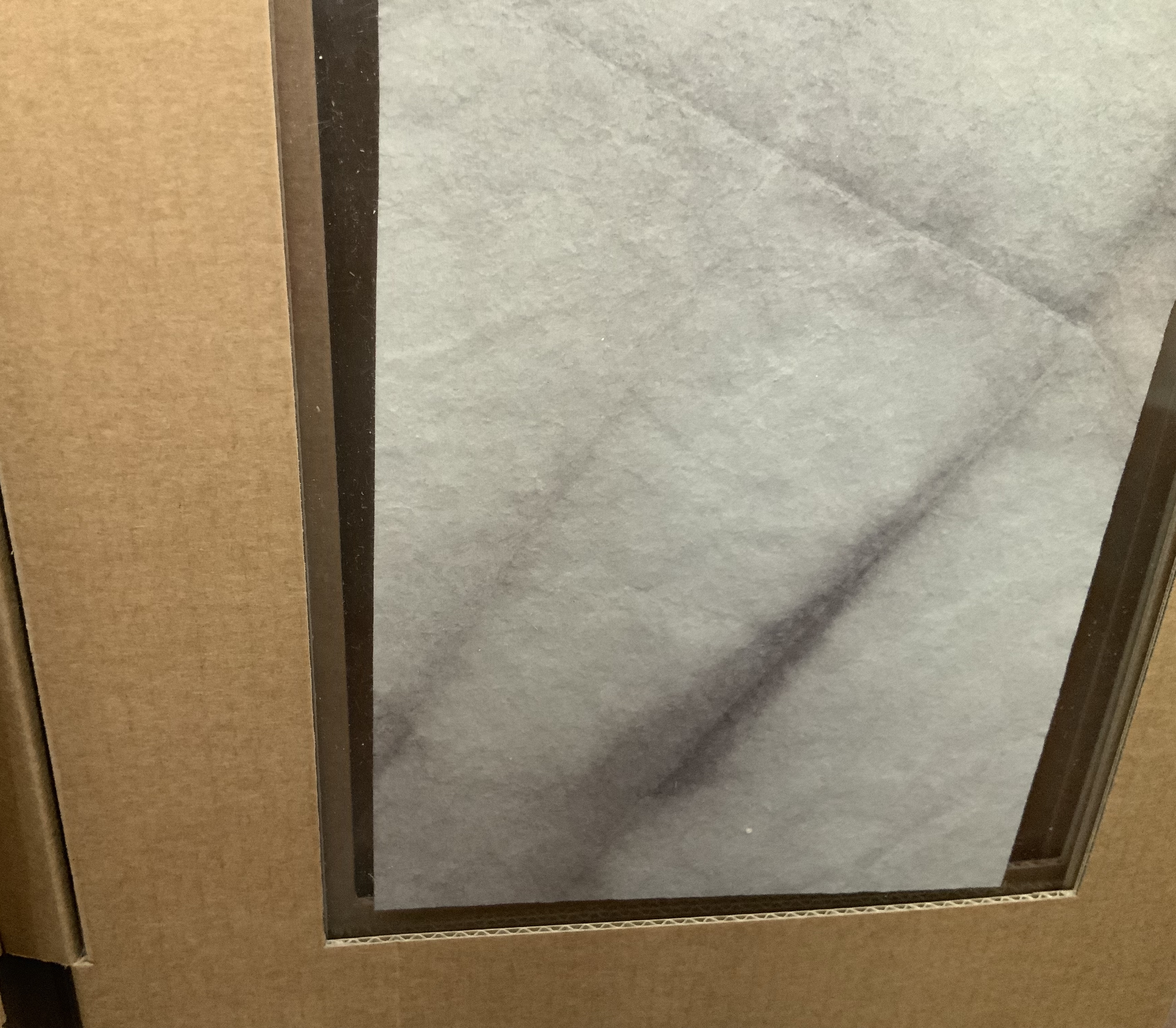

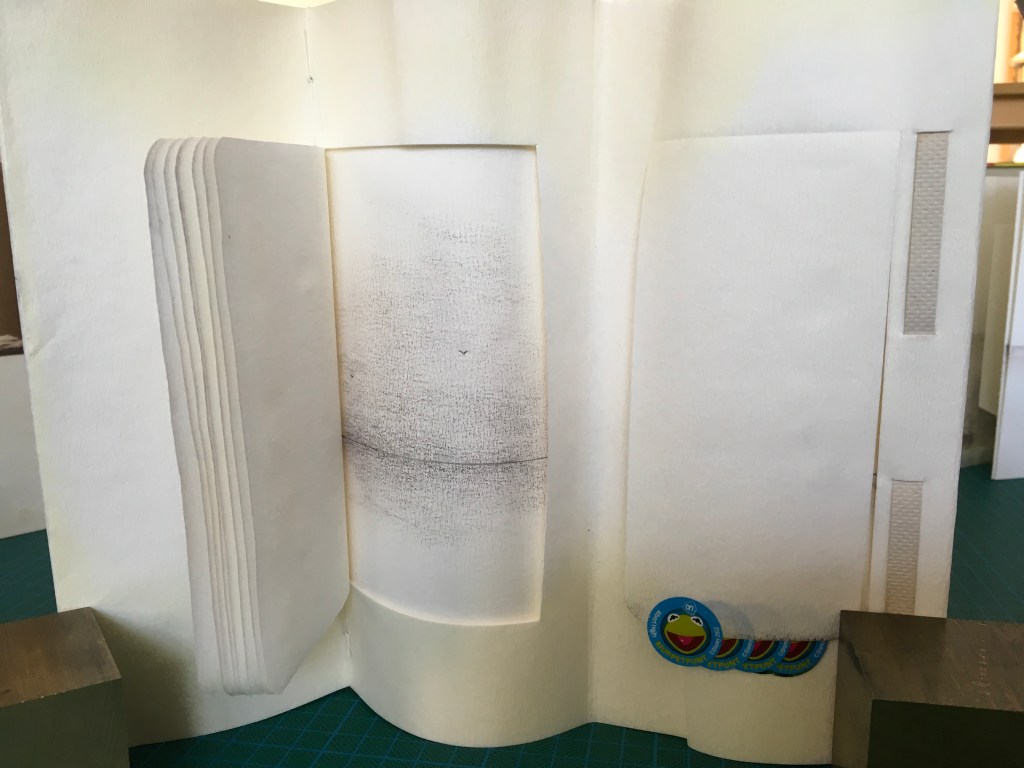

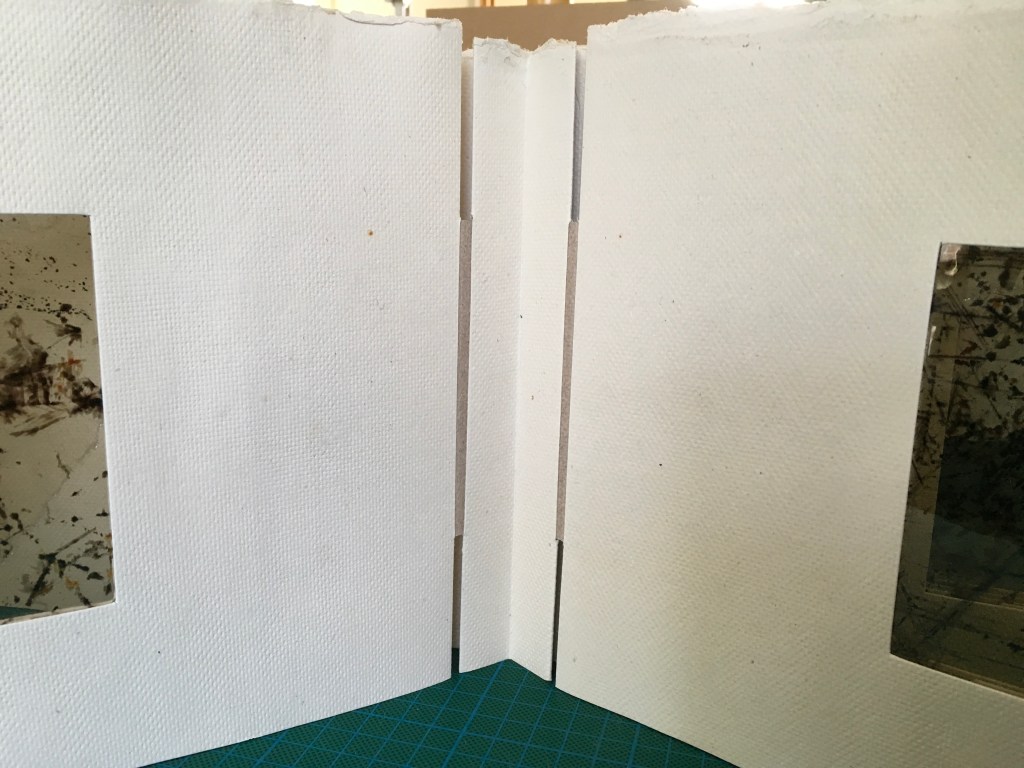

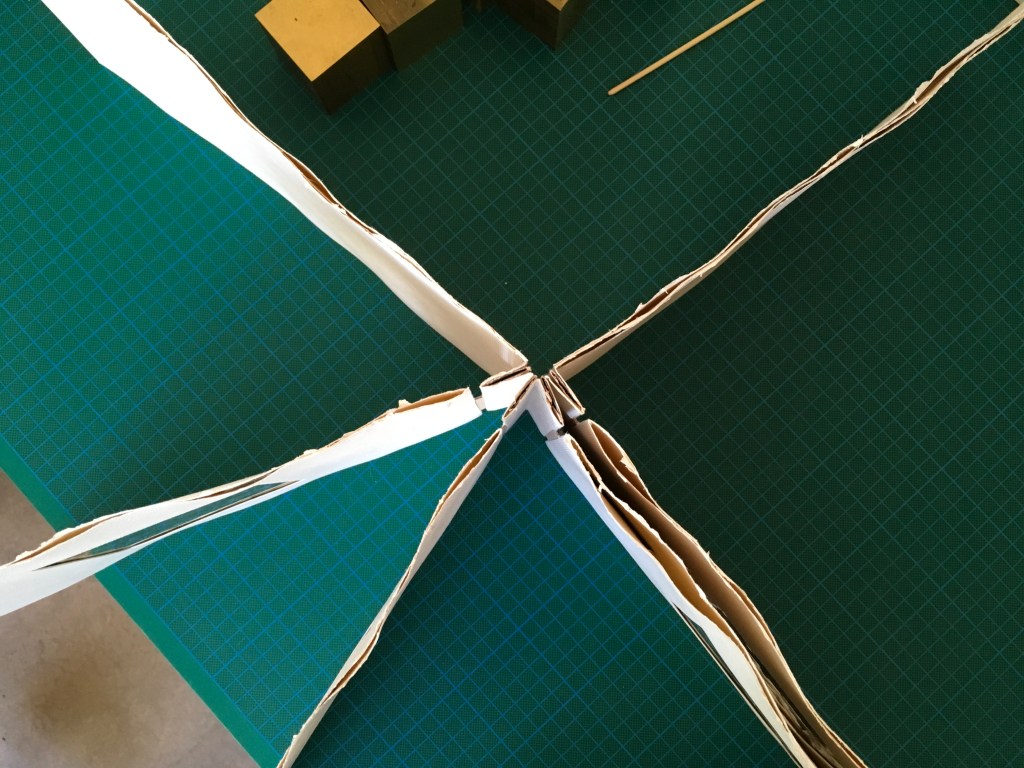

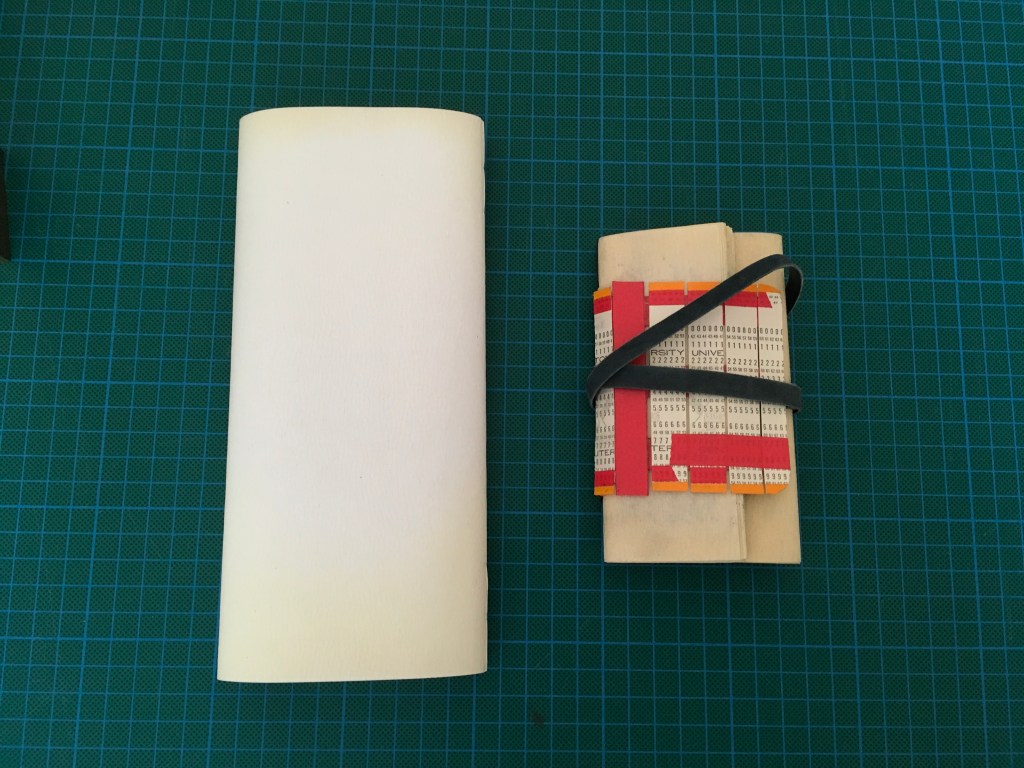

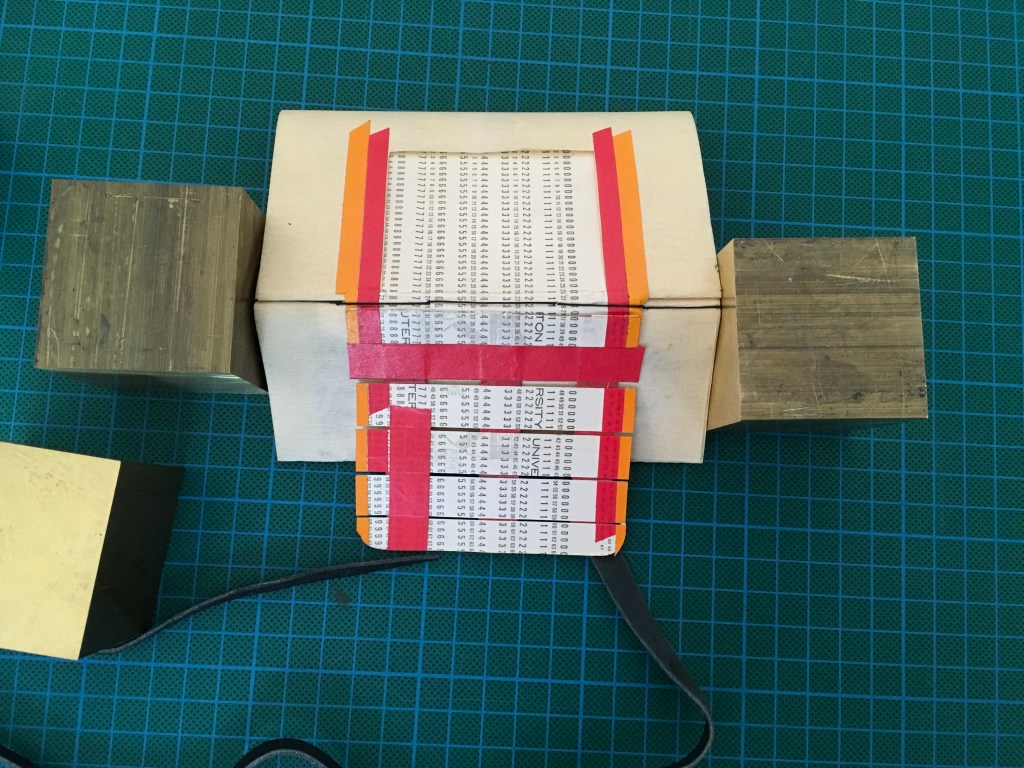

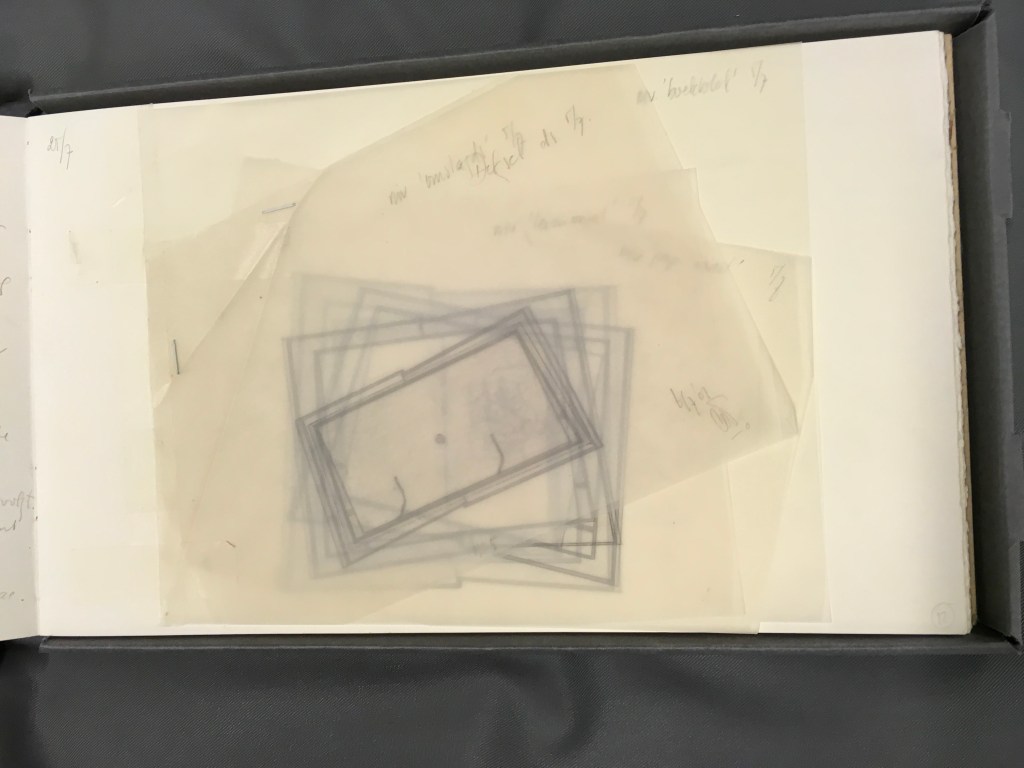

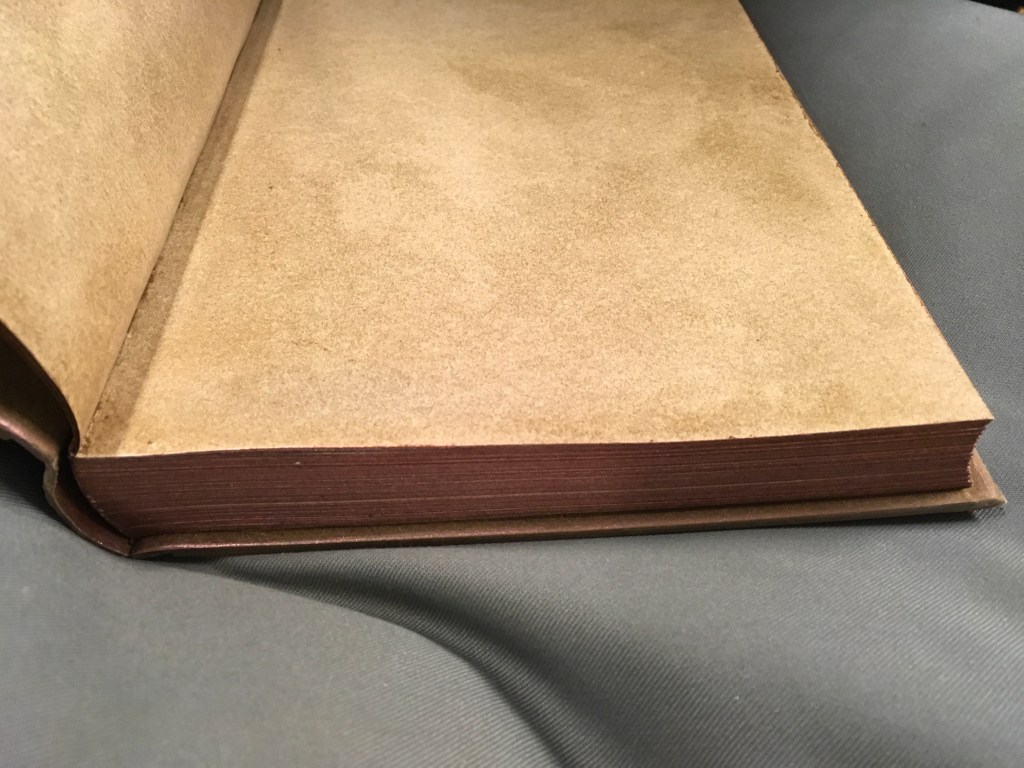

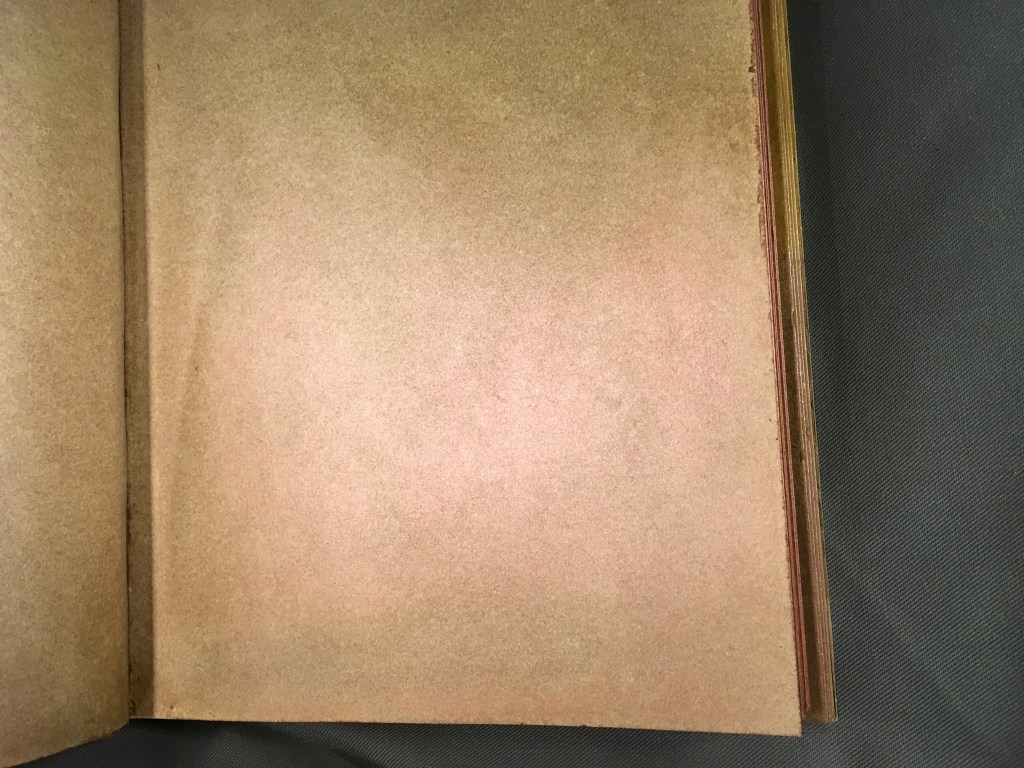

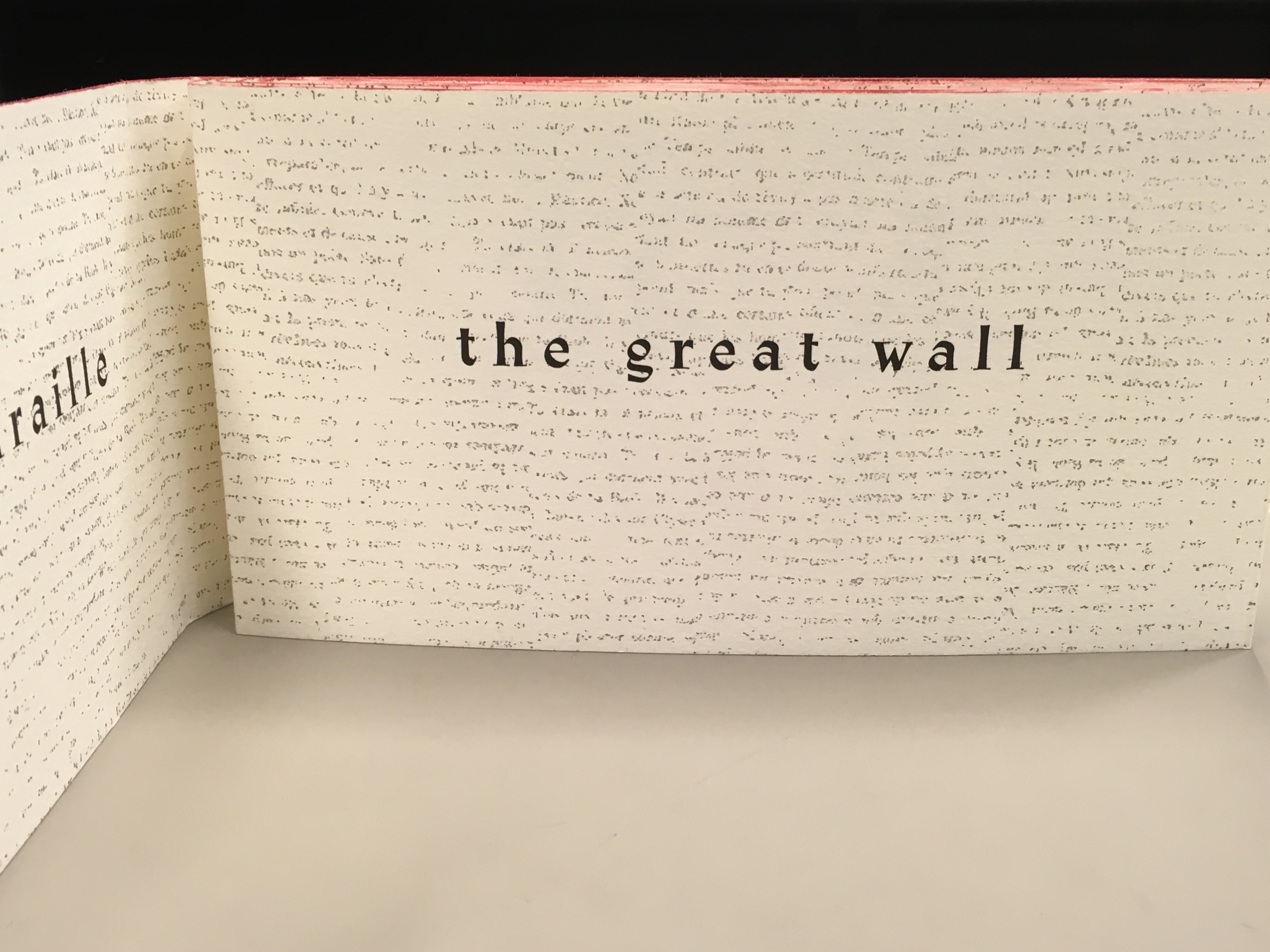

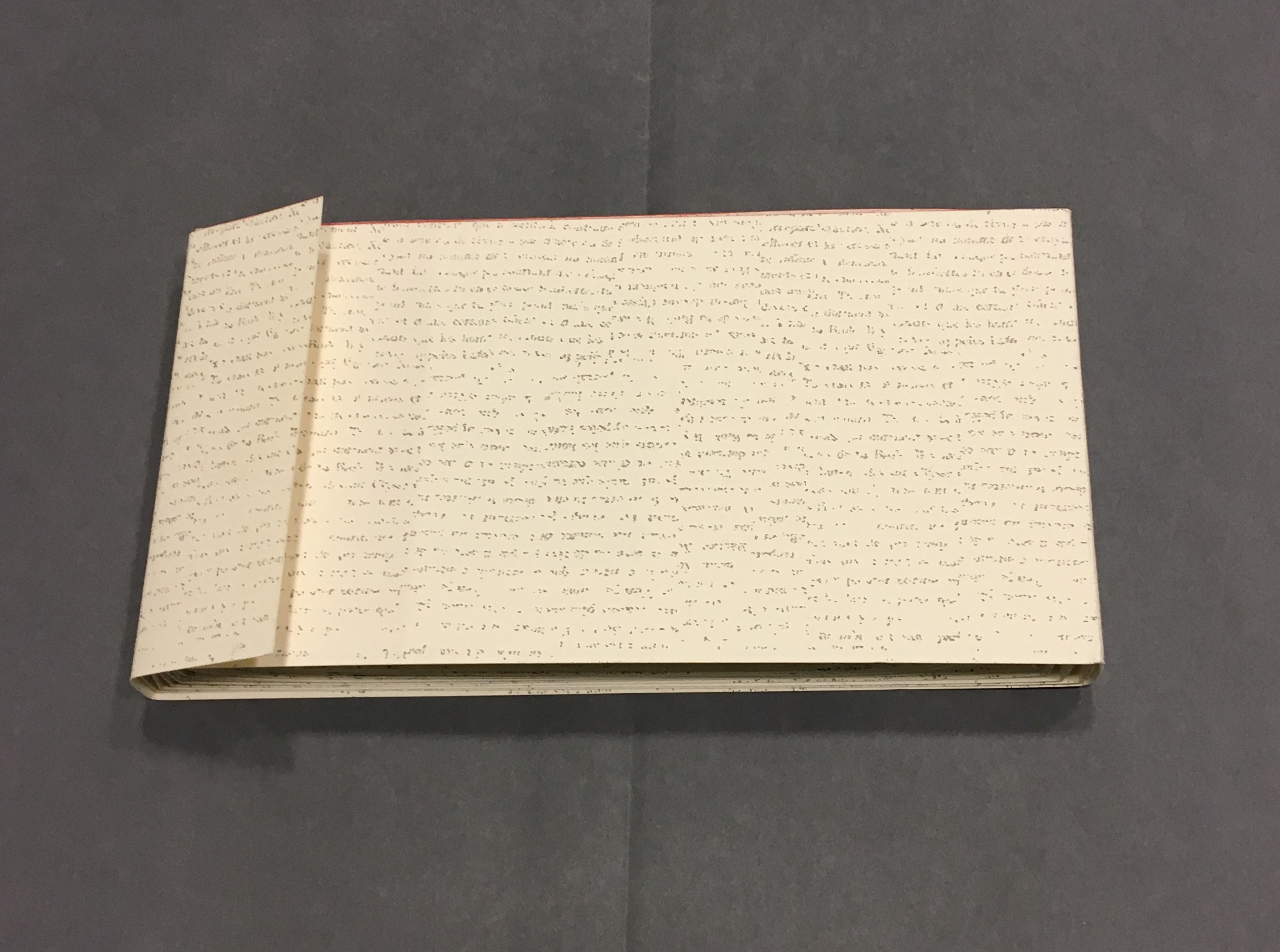

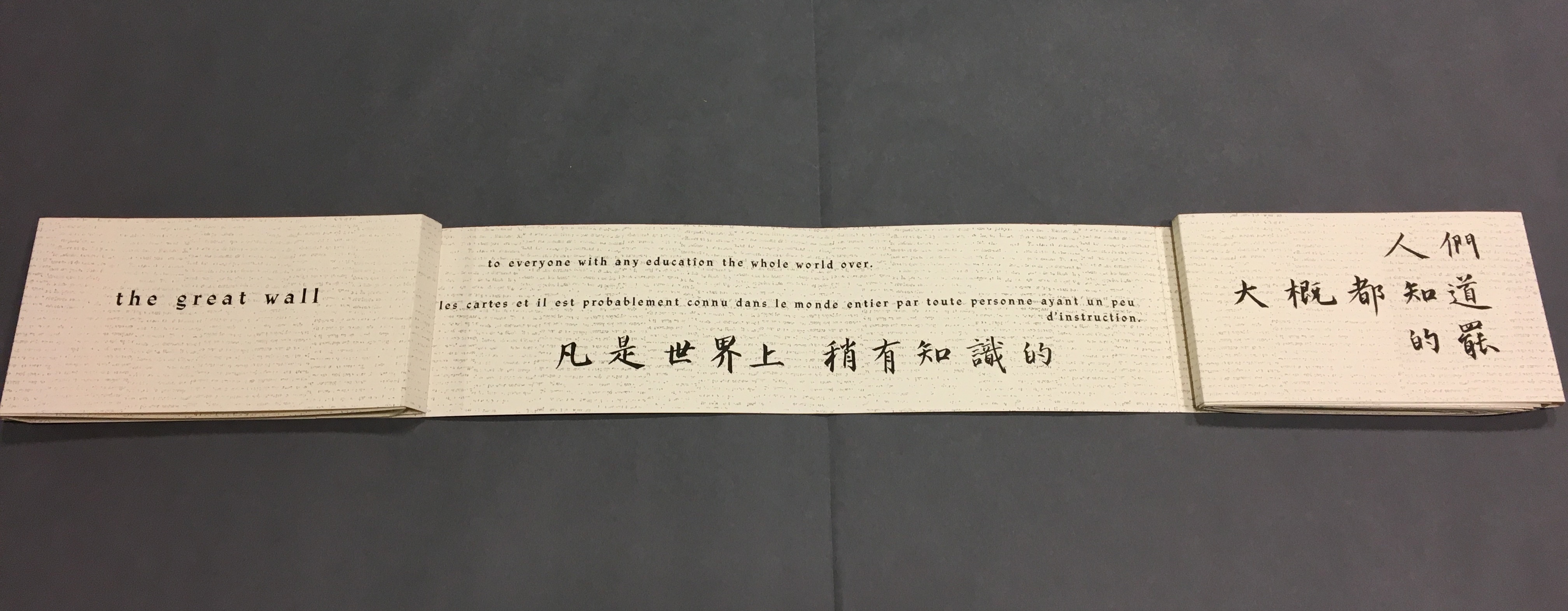

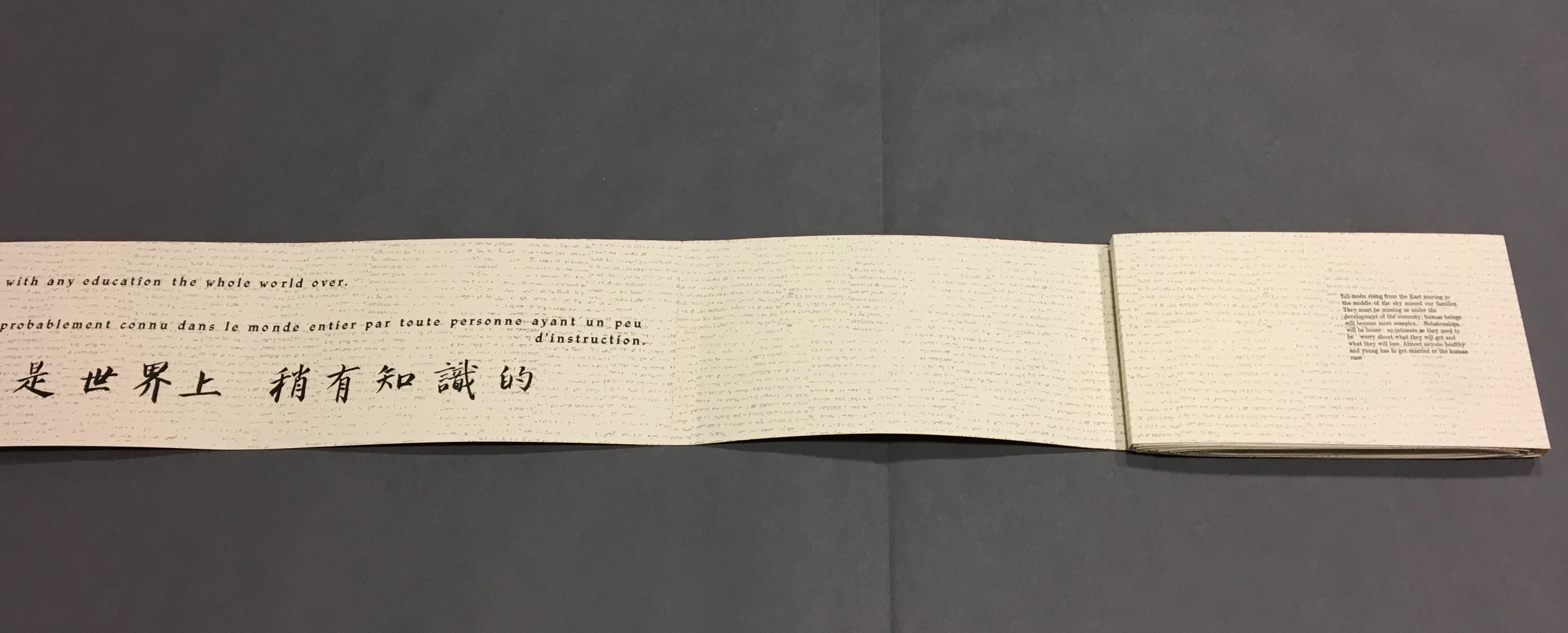

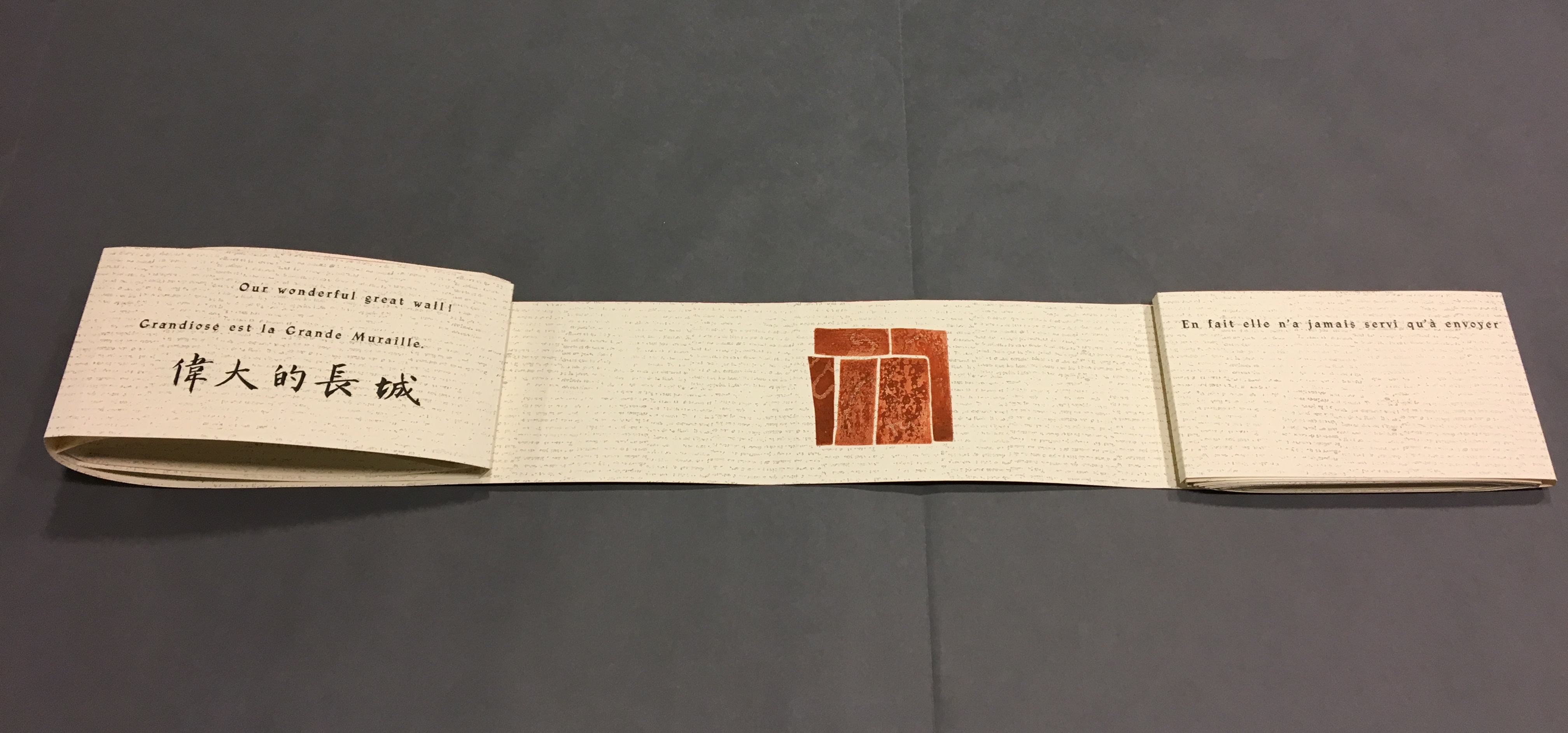

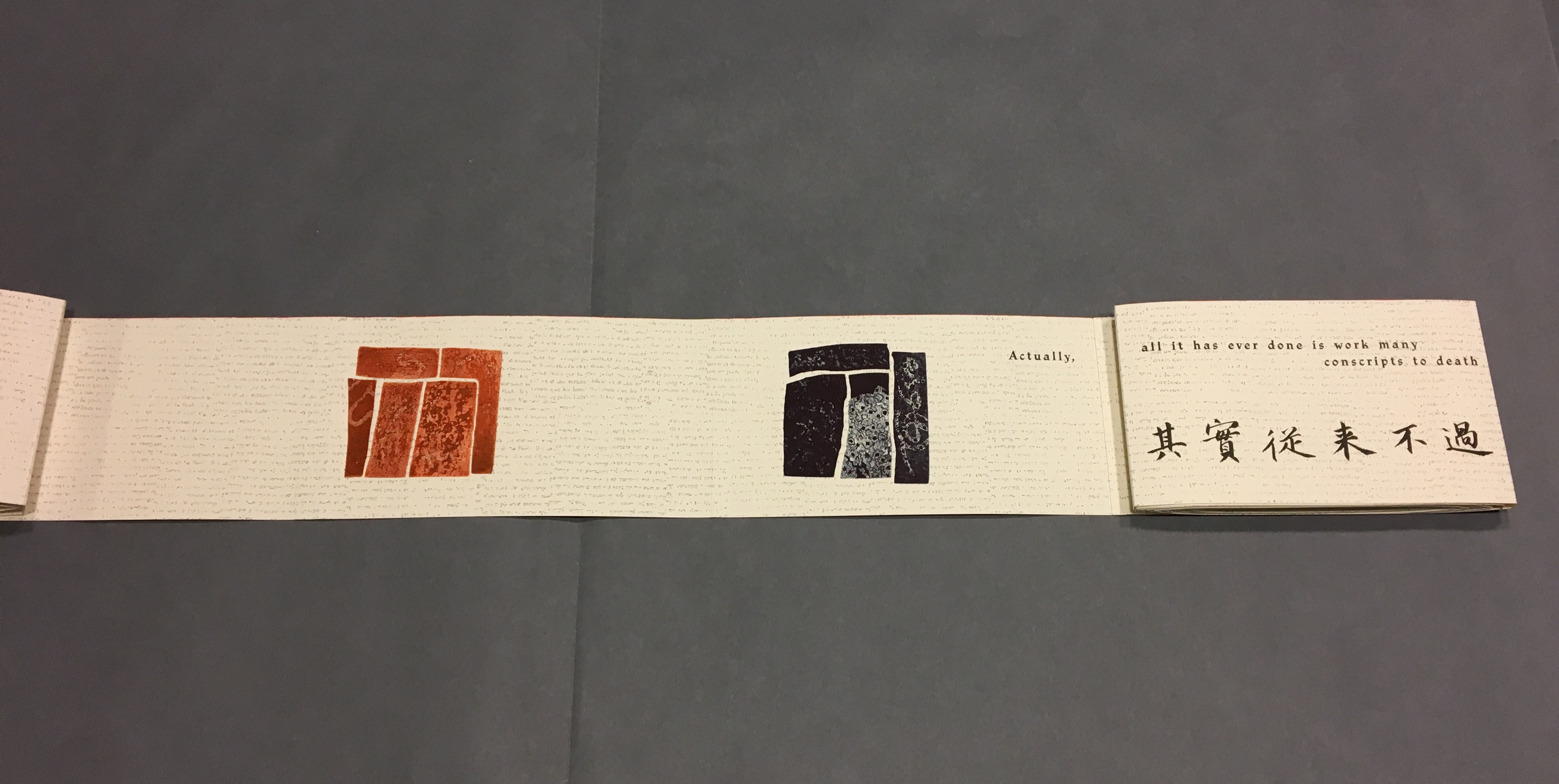

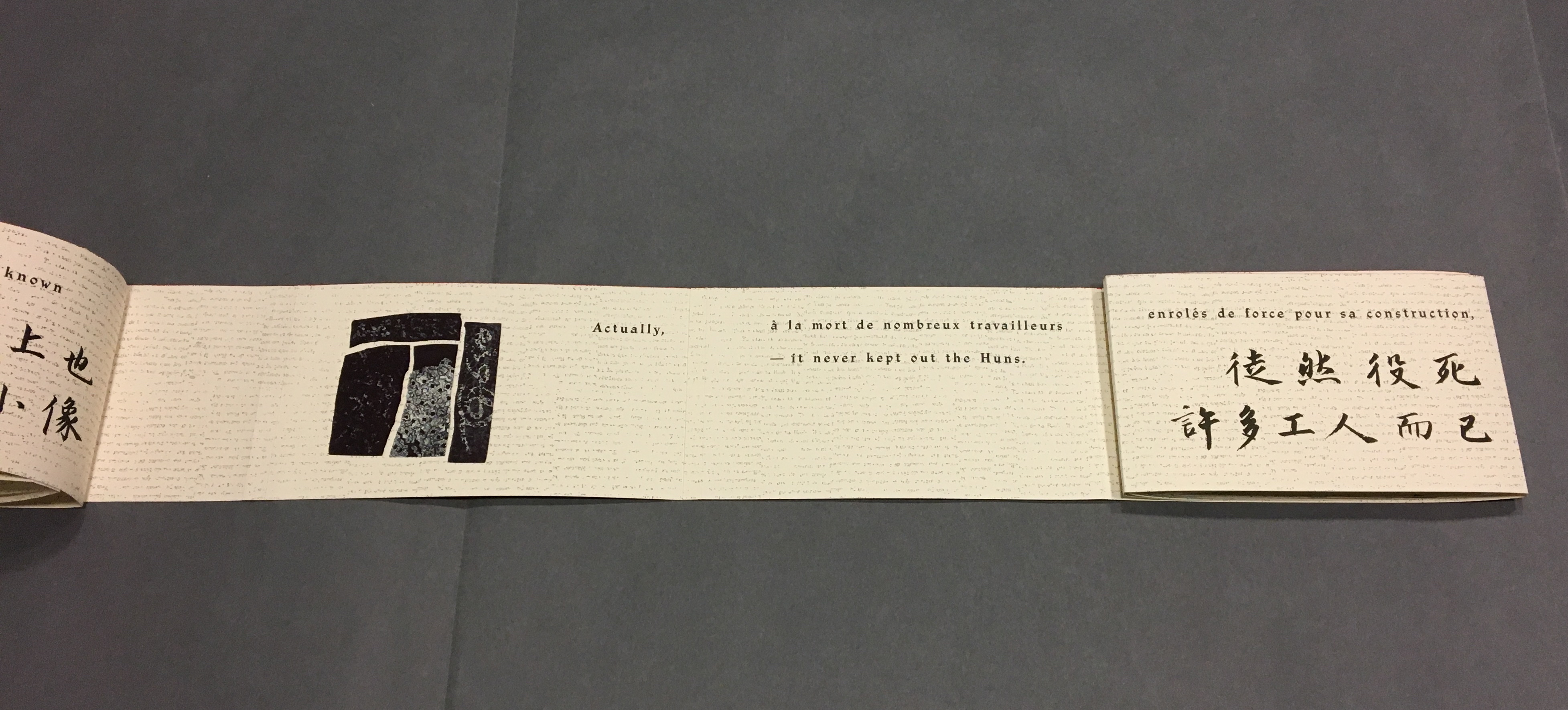

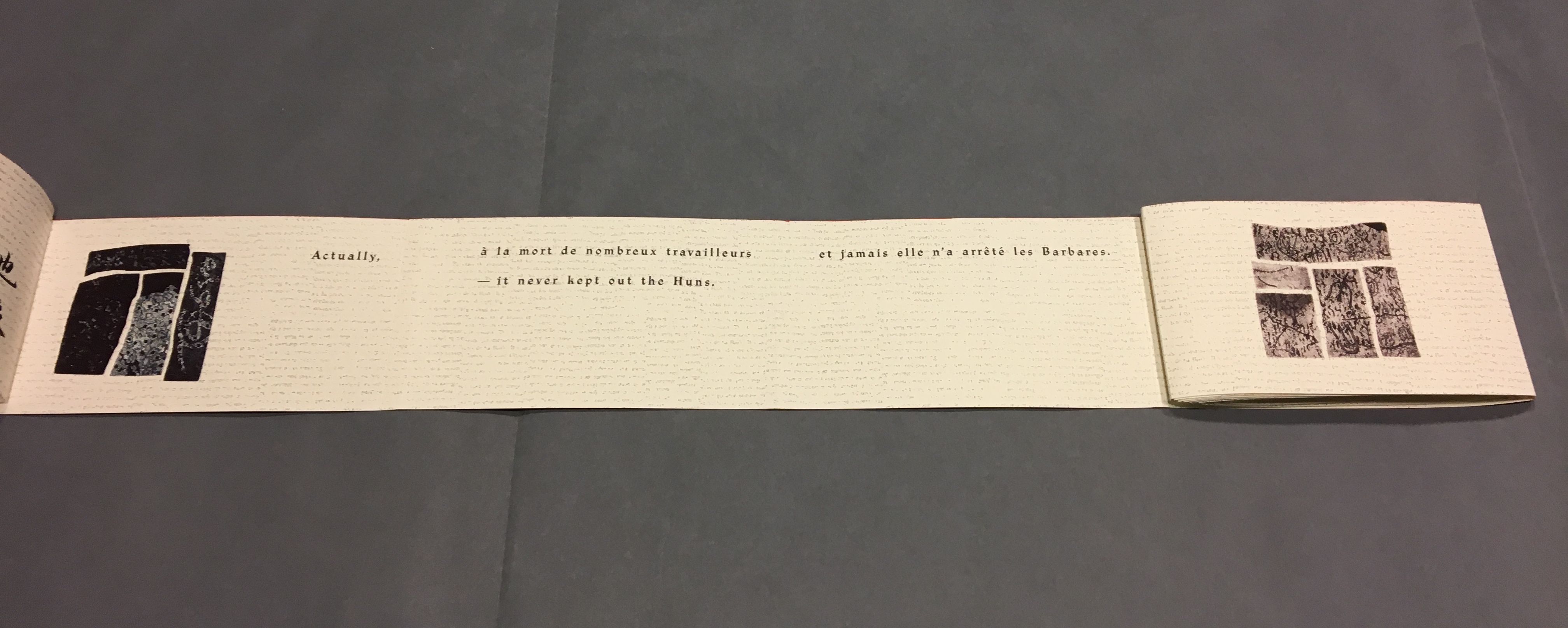

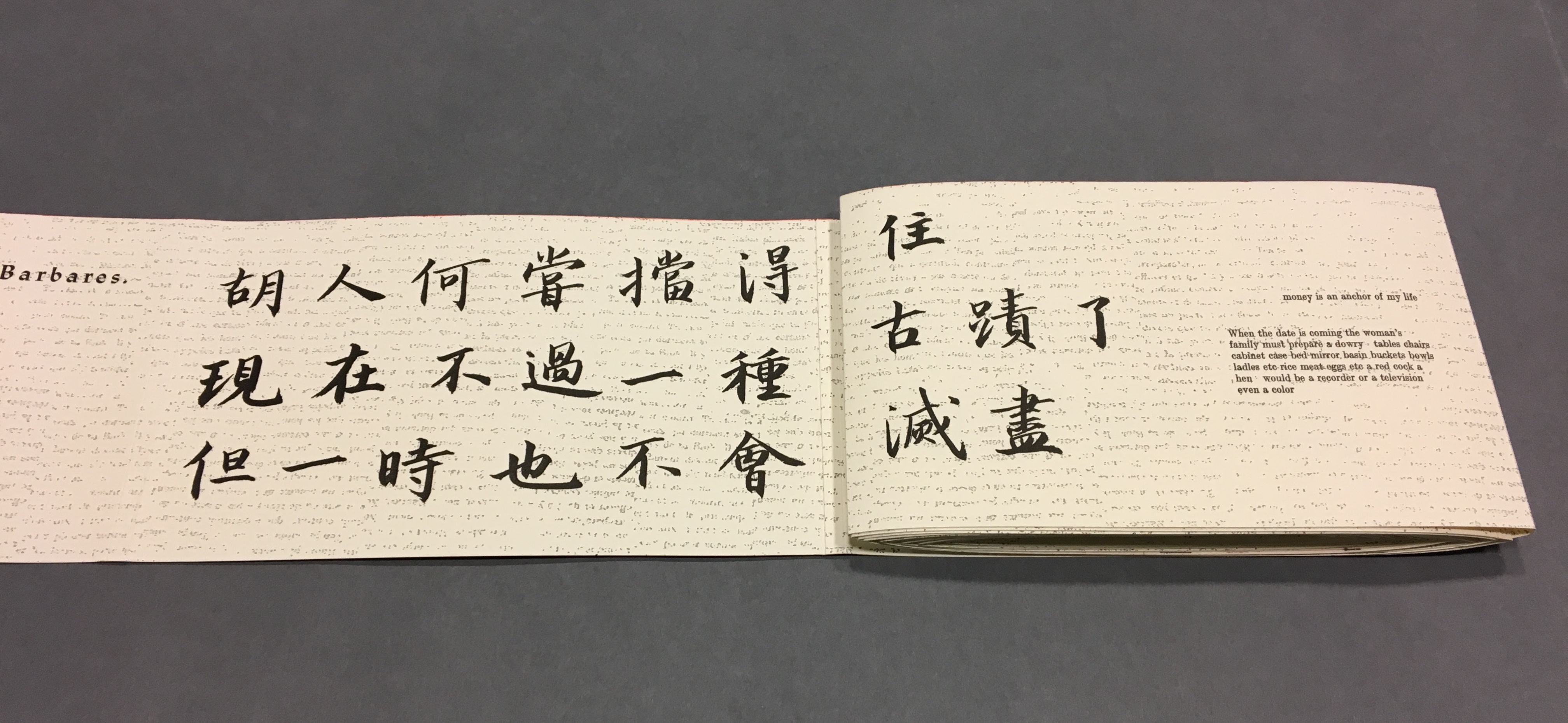

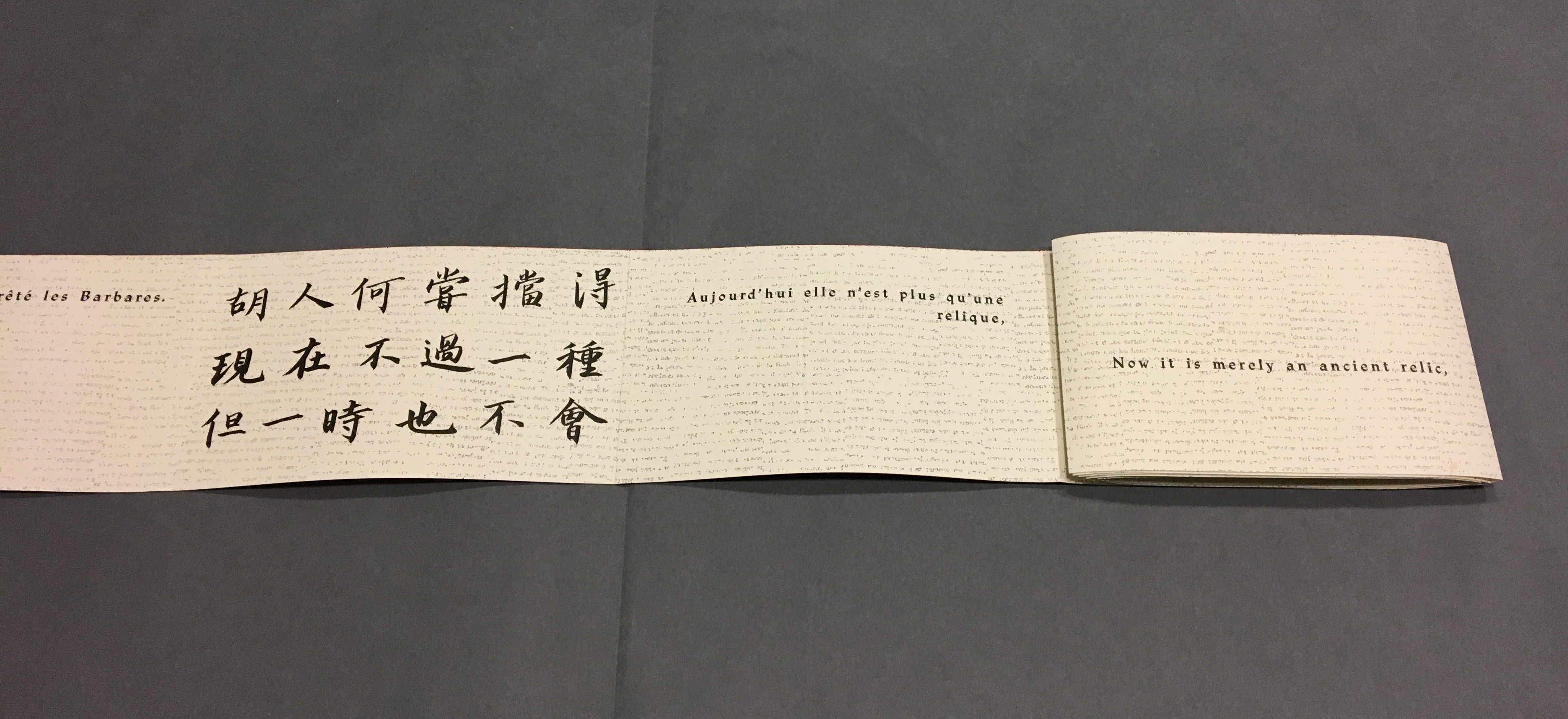

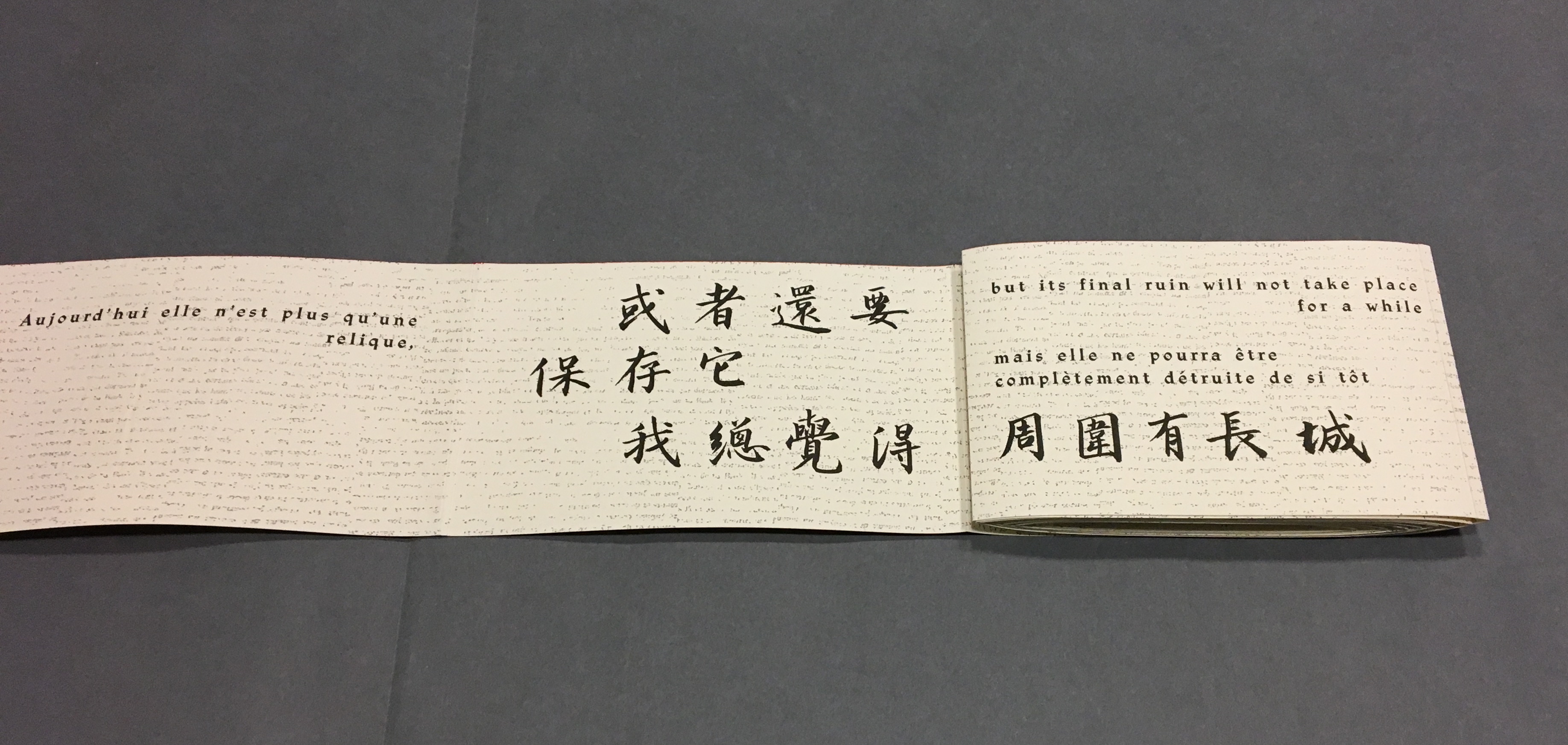

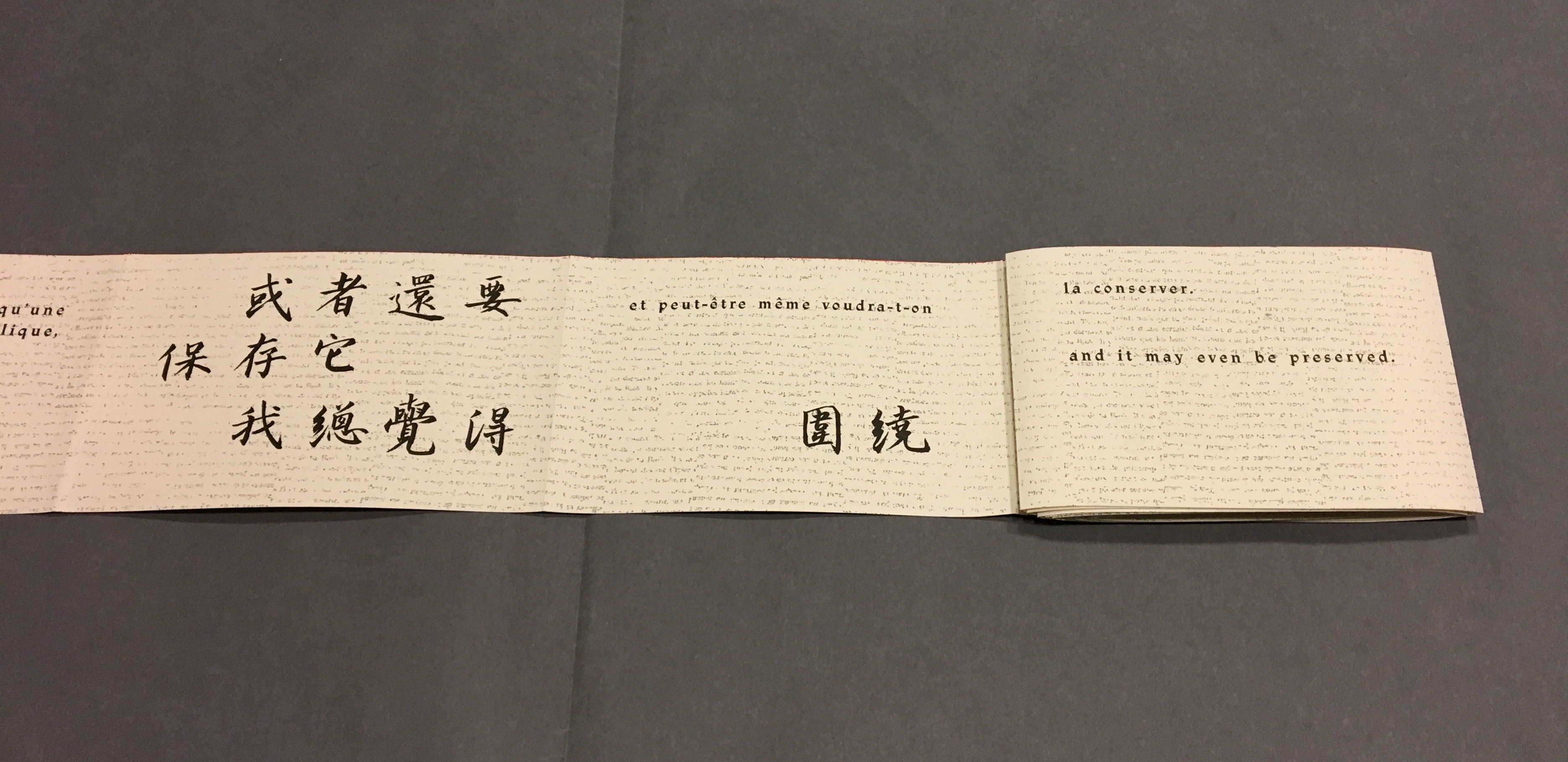

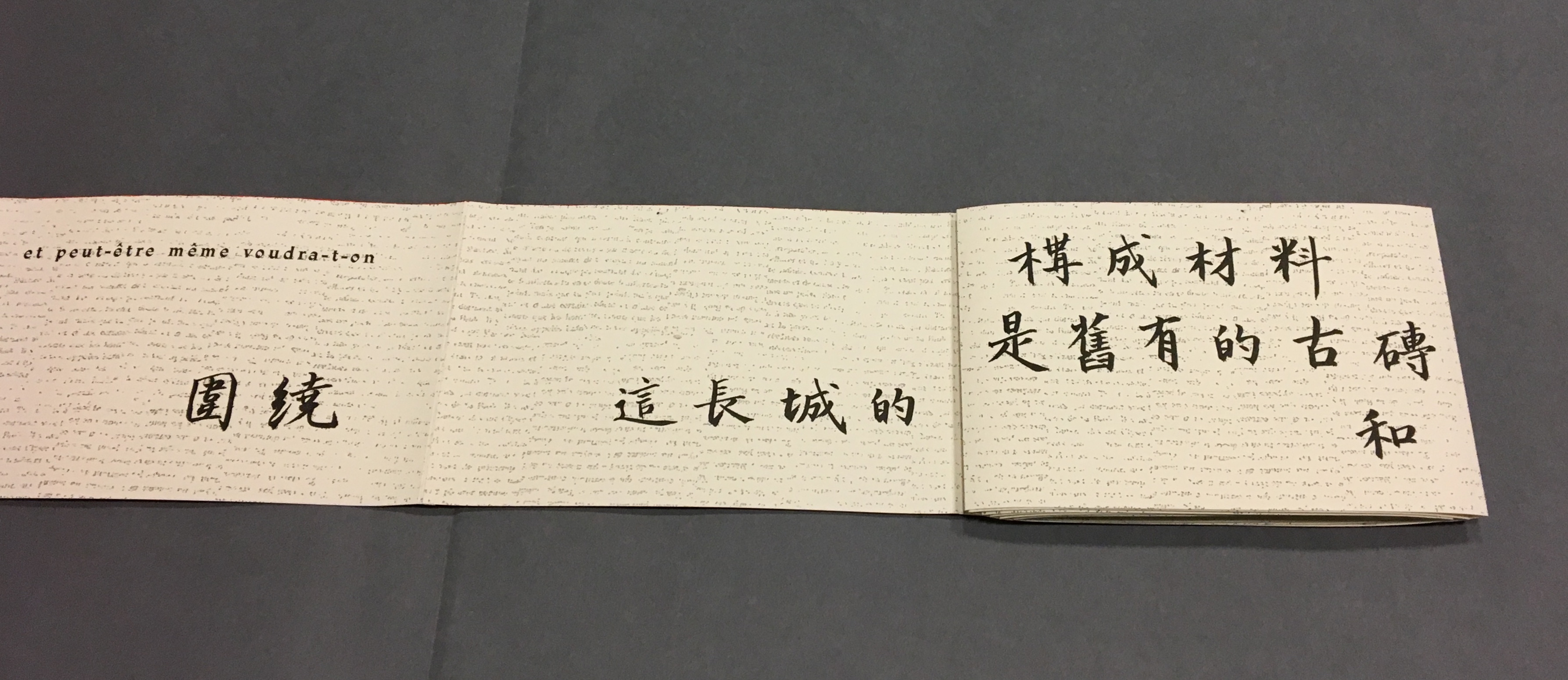

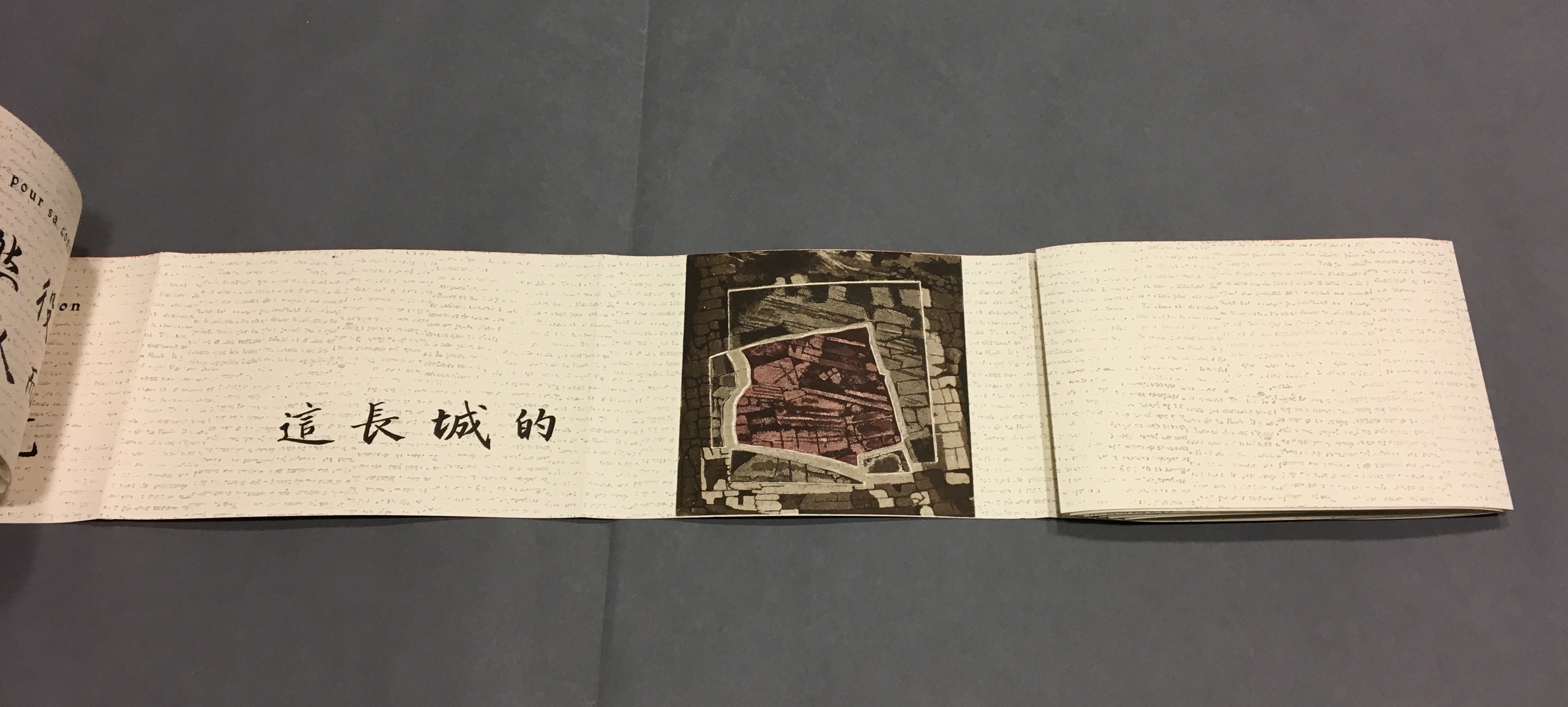

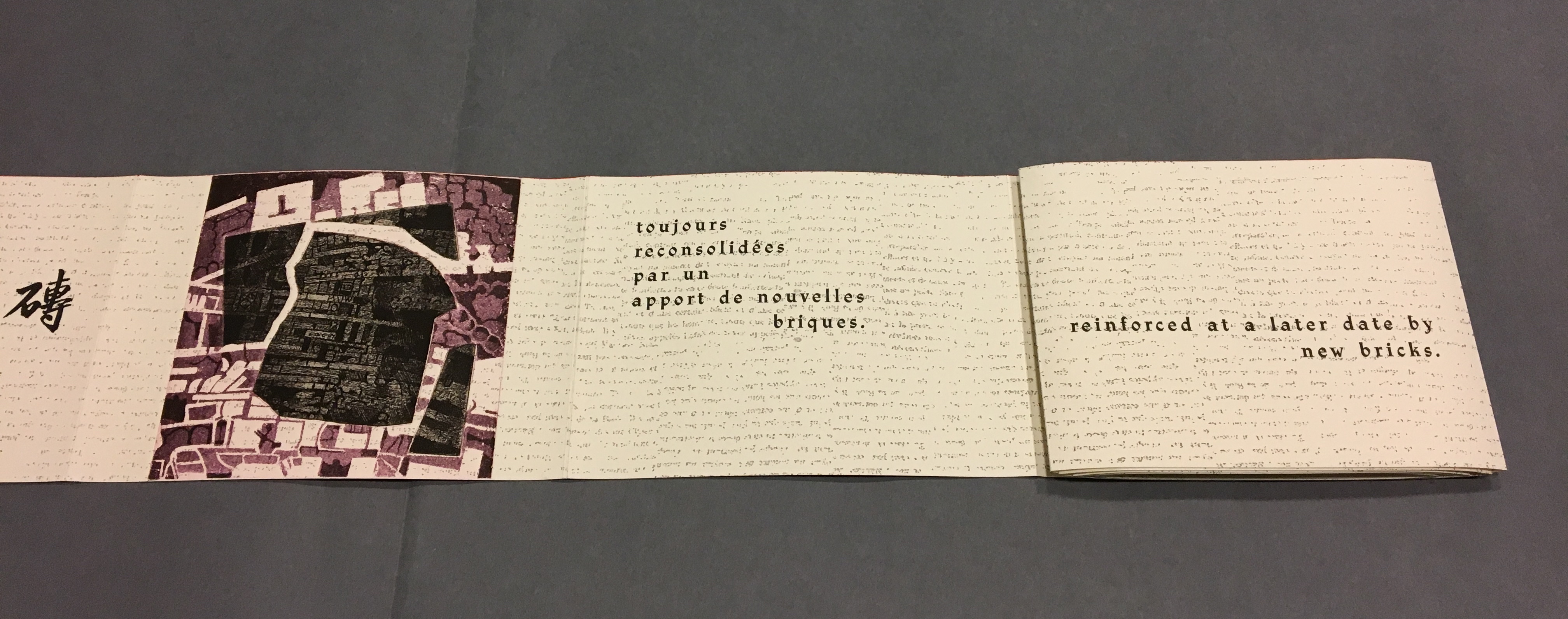

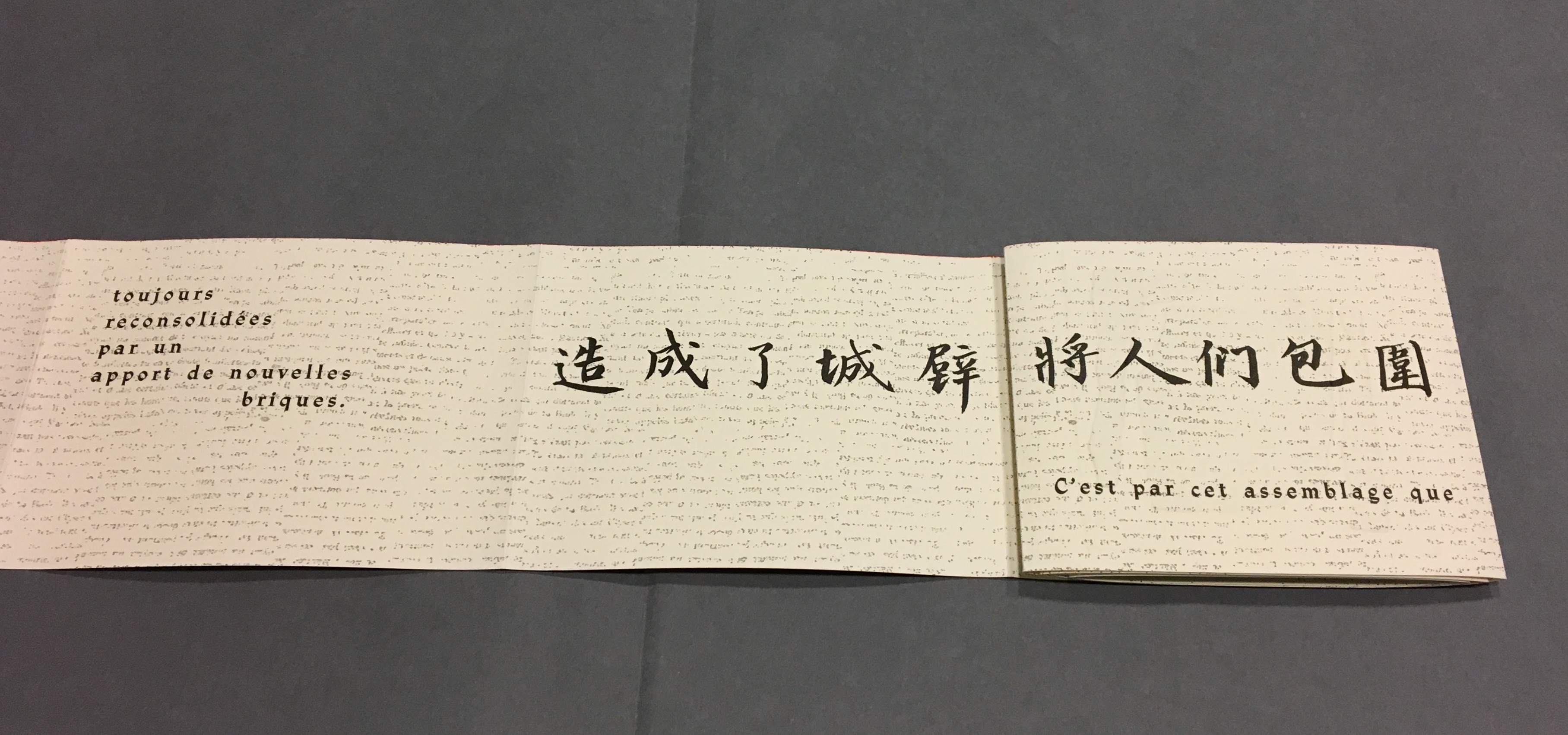

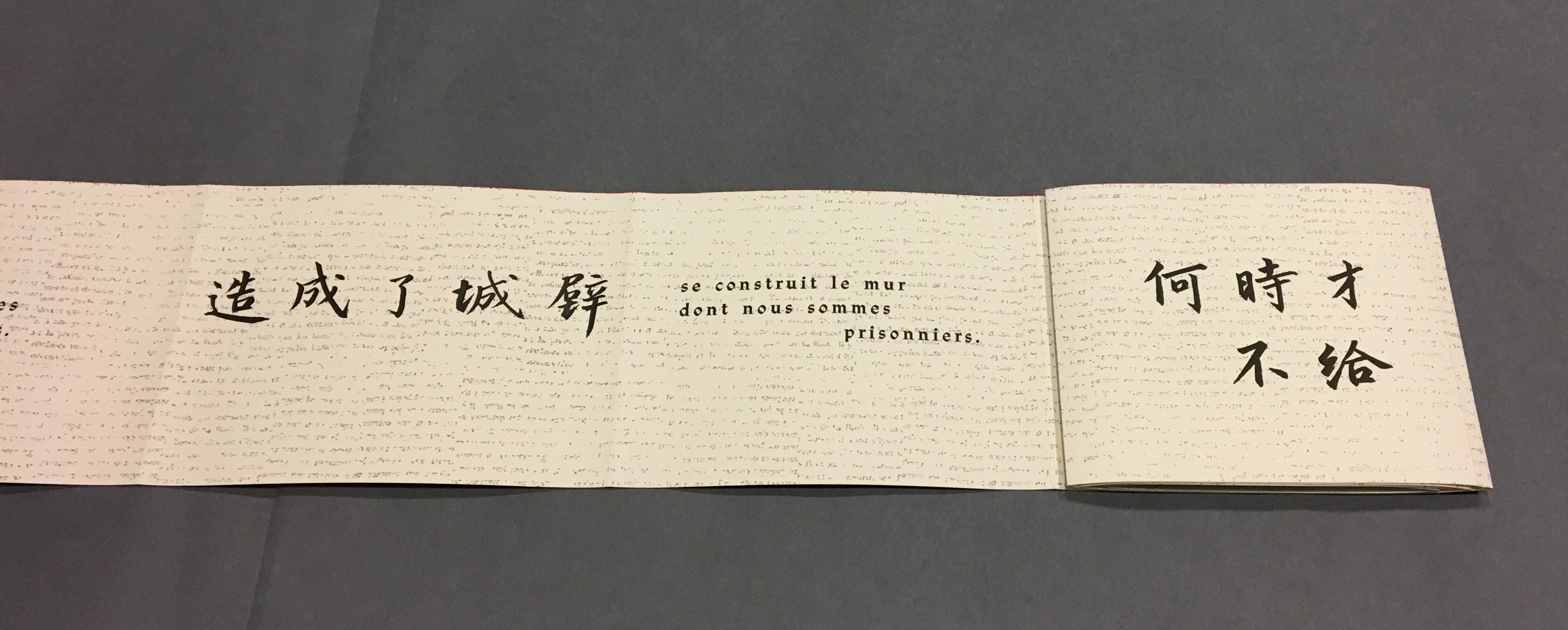

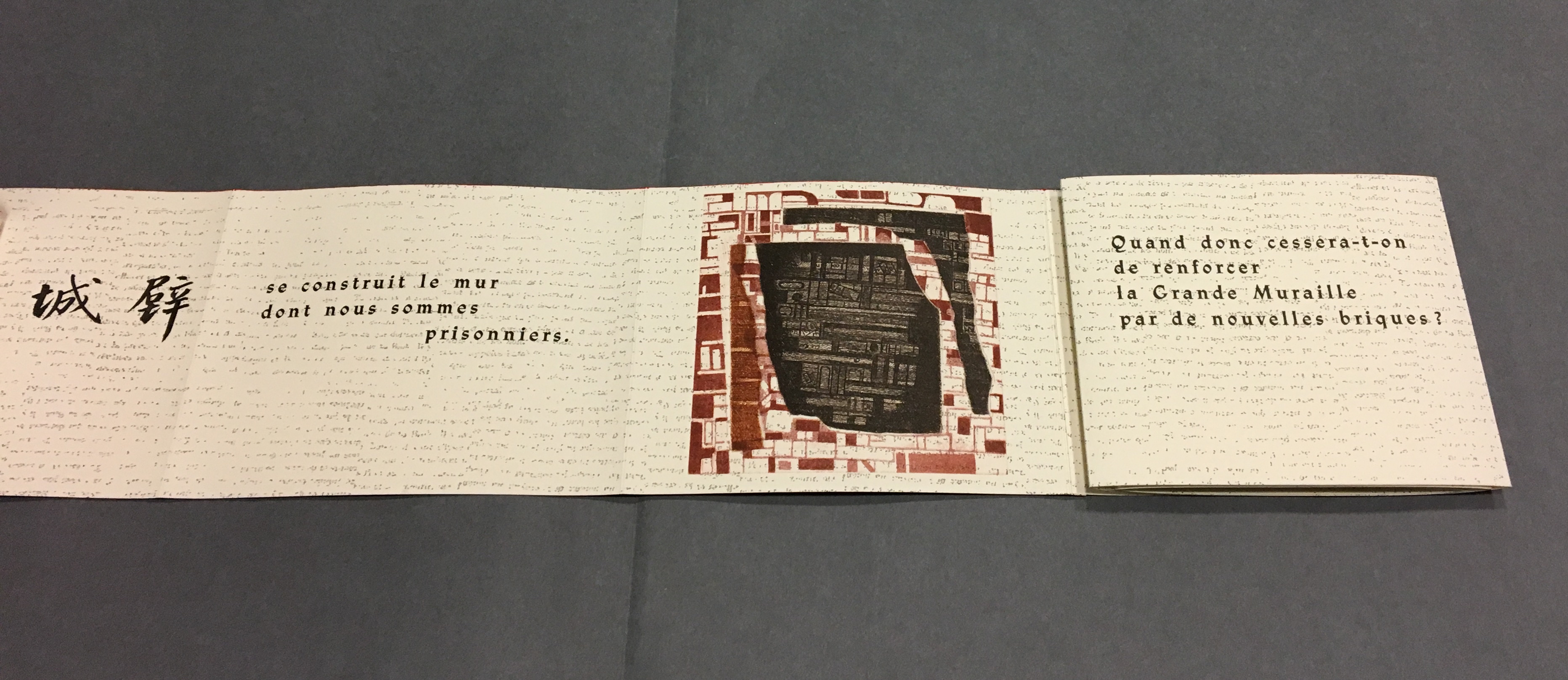

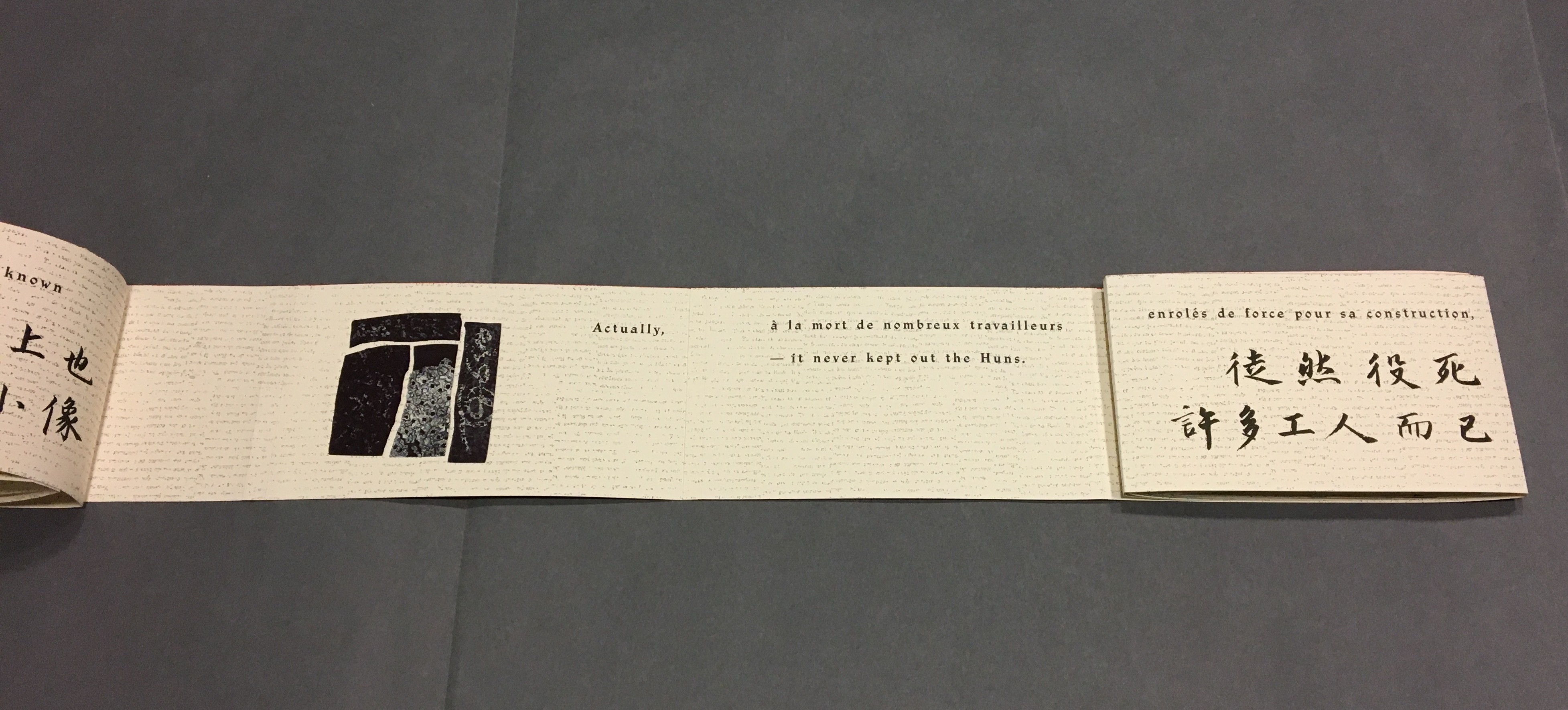

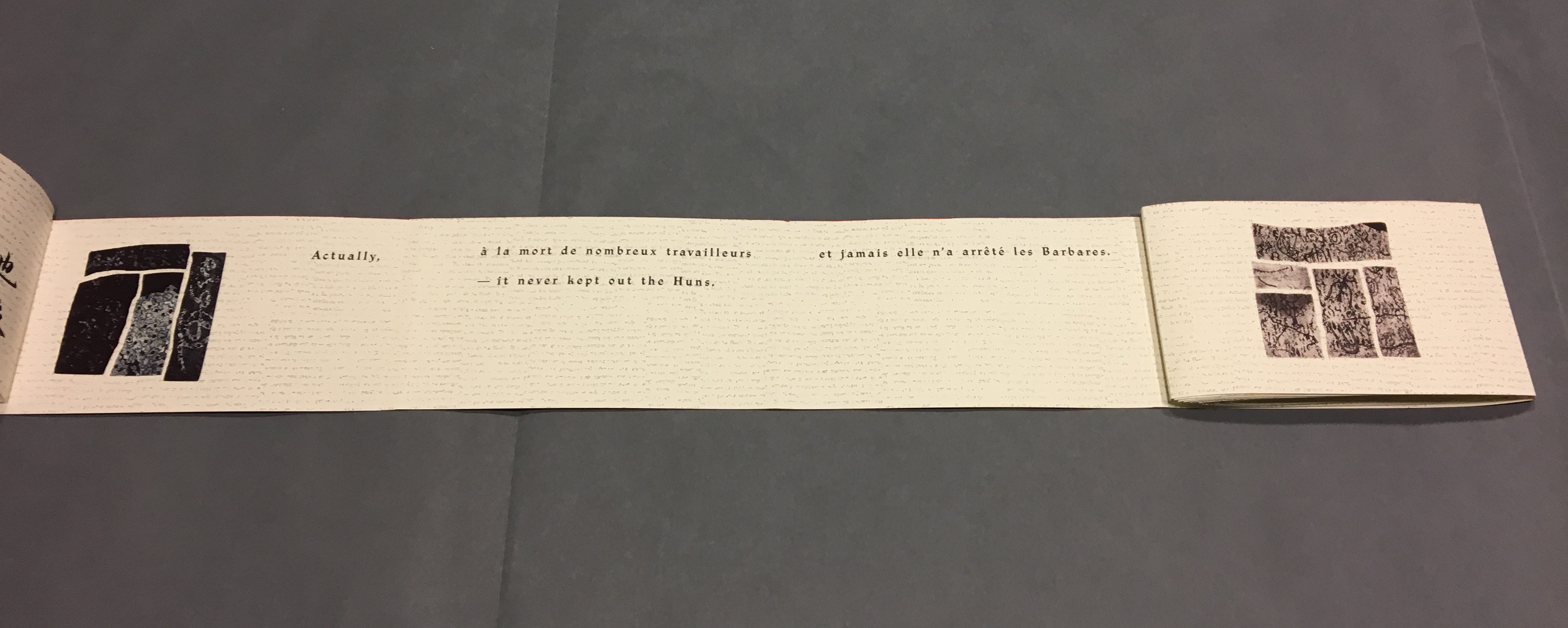

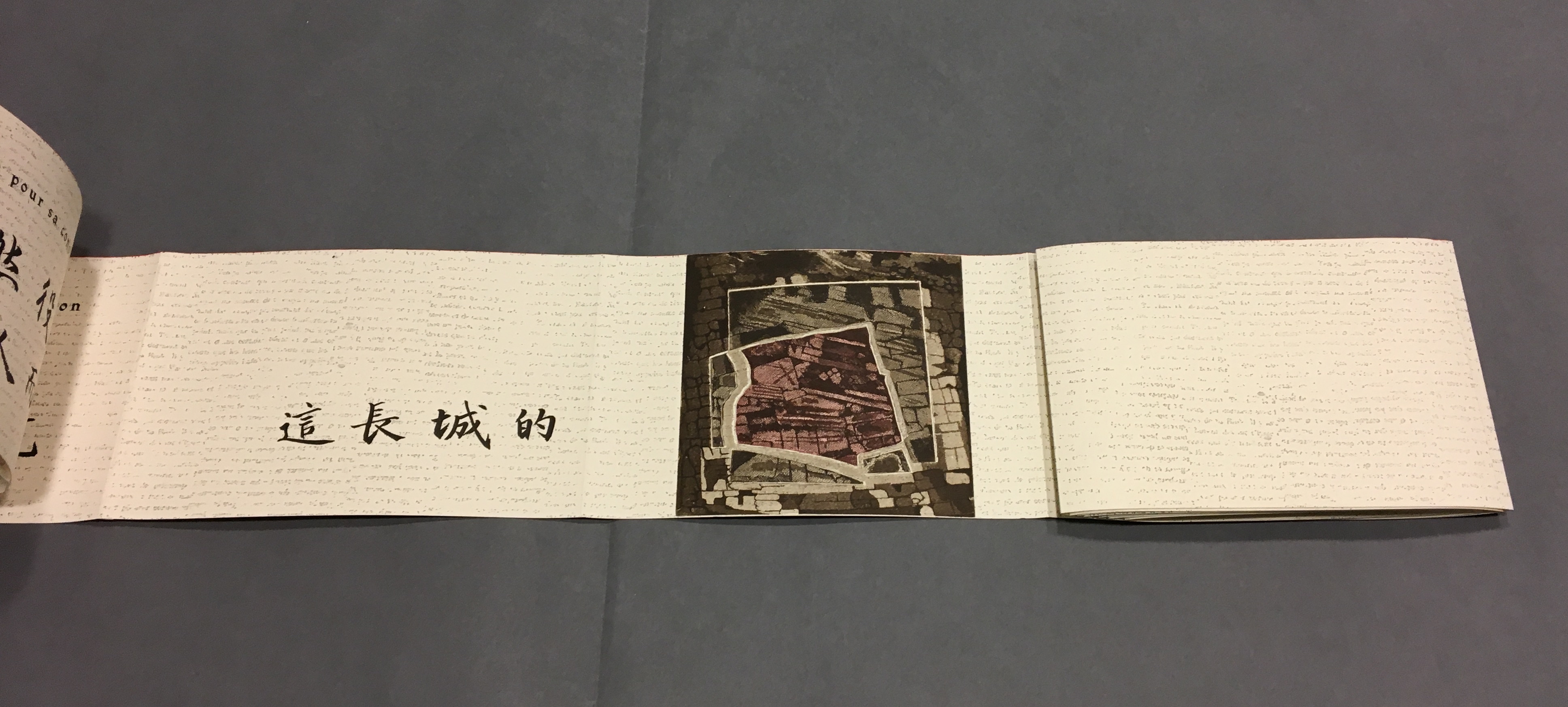

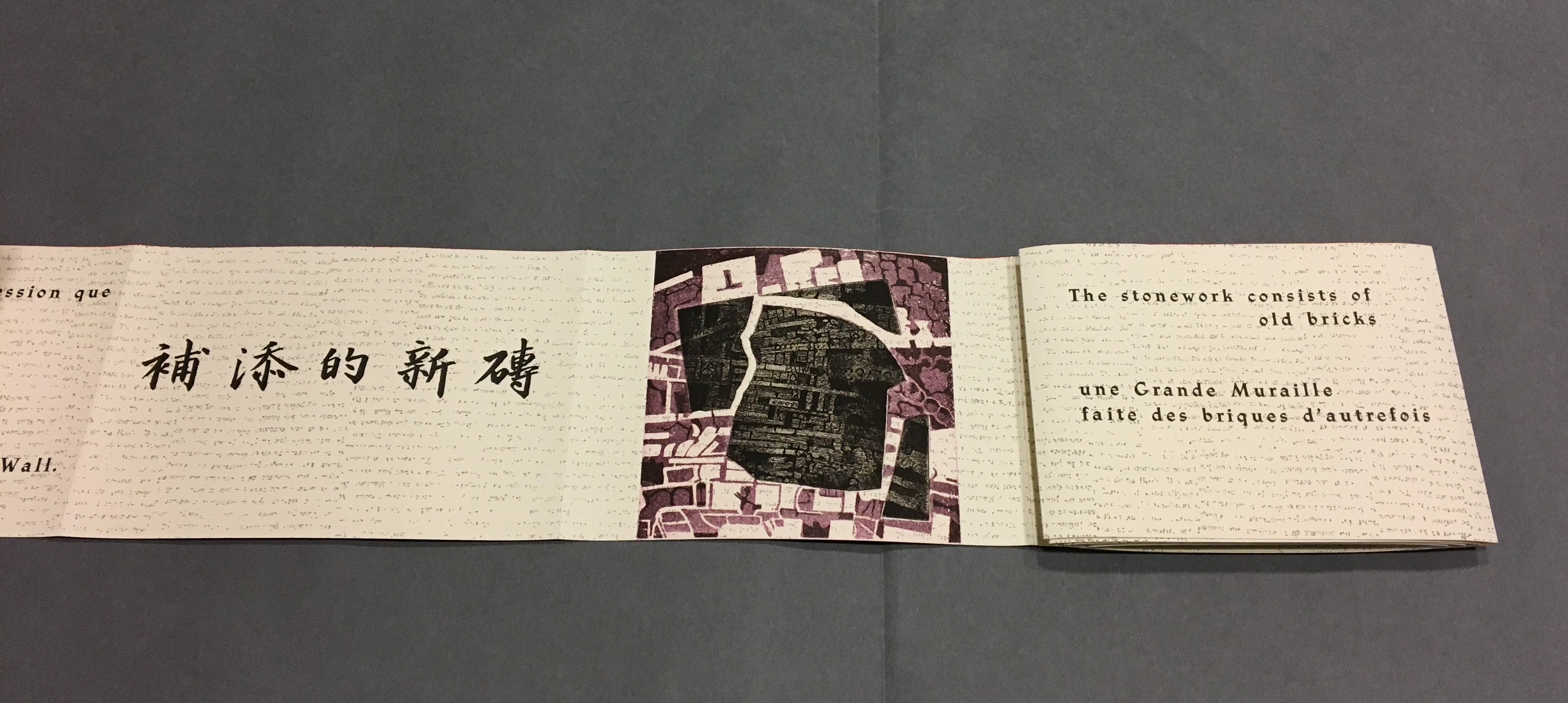

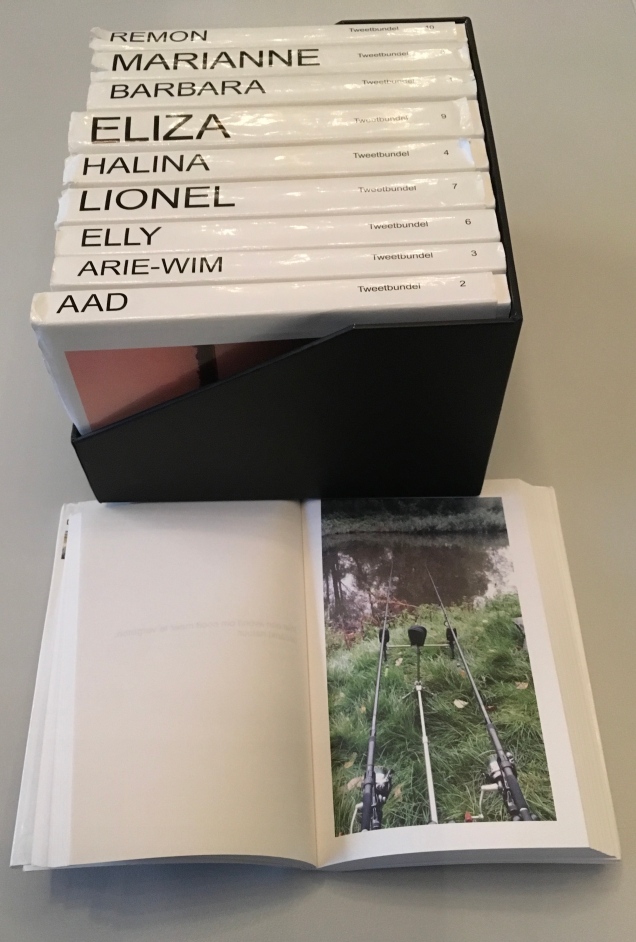

Plexiglass slipcase (287 x 203 x 14 mm) containing two volumes (278 x 198 x 3 mm), 48 unnumbered pages. Edition of 35, of which this is #18. Acquired from the artist, 14 December 2020. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with the artist’s permission.

Paul van Capelleveen, curator at the National Library of the Netherlands, writes in his contribution to Ines von Ketelhodt’s exhibition catalogue Bücher///Books (2019):

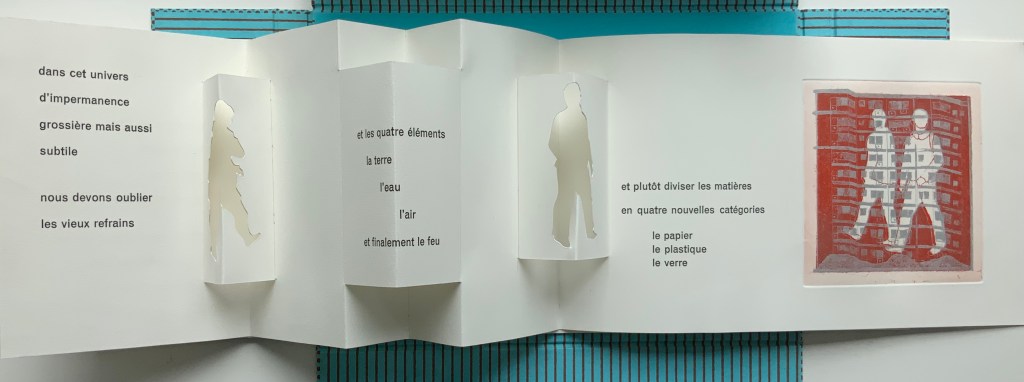

The artist’s book is, perhaps, more than other book forms, a stage where conventions and innovations may be brought to life. On this stage, typography is a means of text interpretation; it can be visual, decorative, or alienating. It should be noted that typography is only one of the key players in artists’ books. We have to consider the book’s materiality (paper, binding, weight, size, etc.), its images or blank spaces, and interventions such cutting, erasing, pasting, embossing, and covering. The reader is a spectator, listener, and in many cases an actor as well. (P. 18)

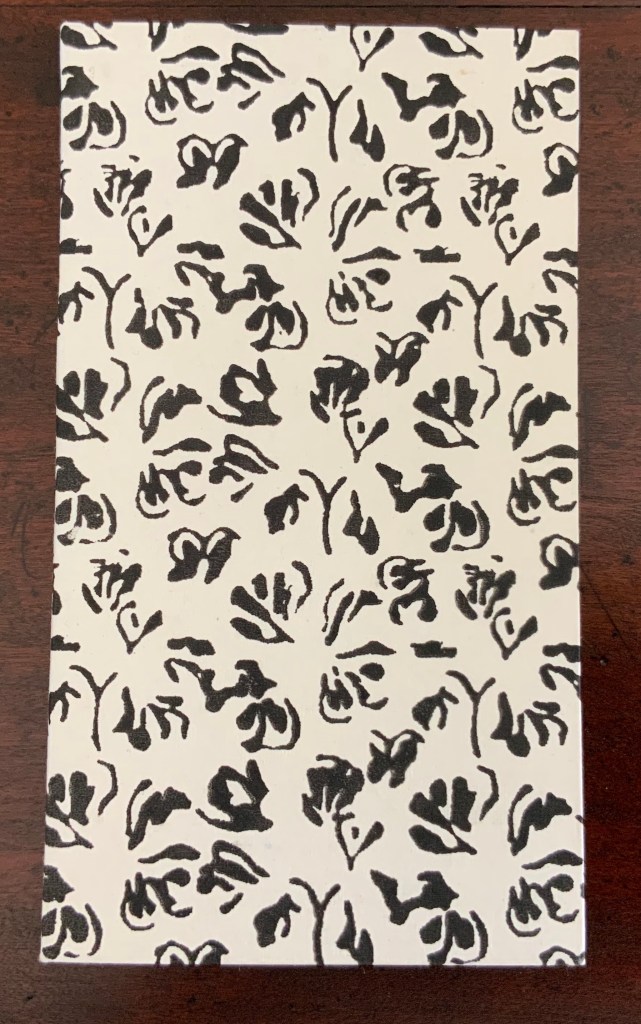

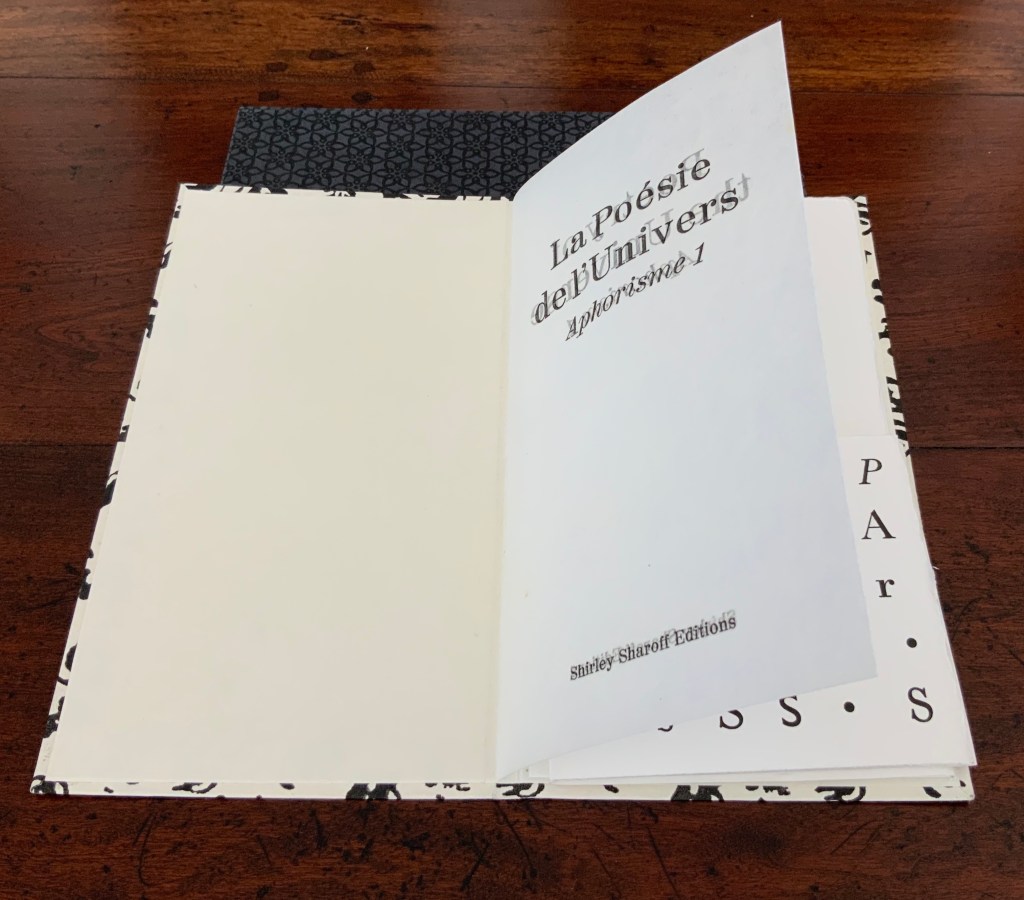

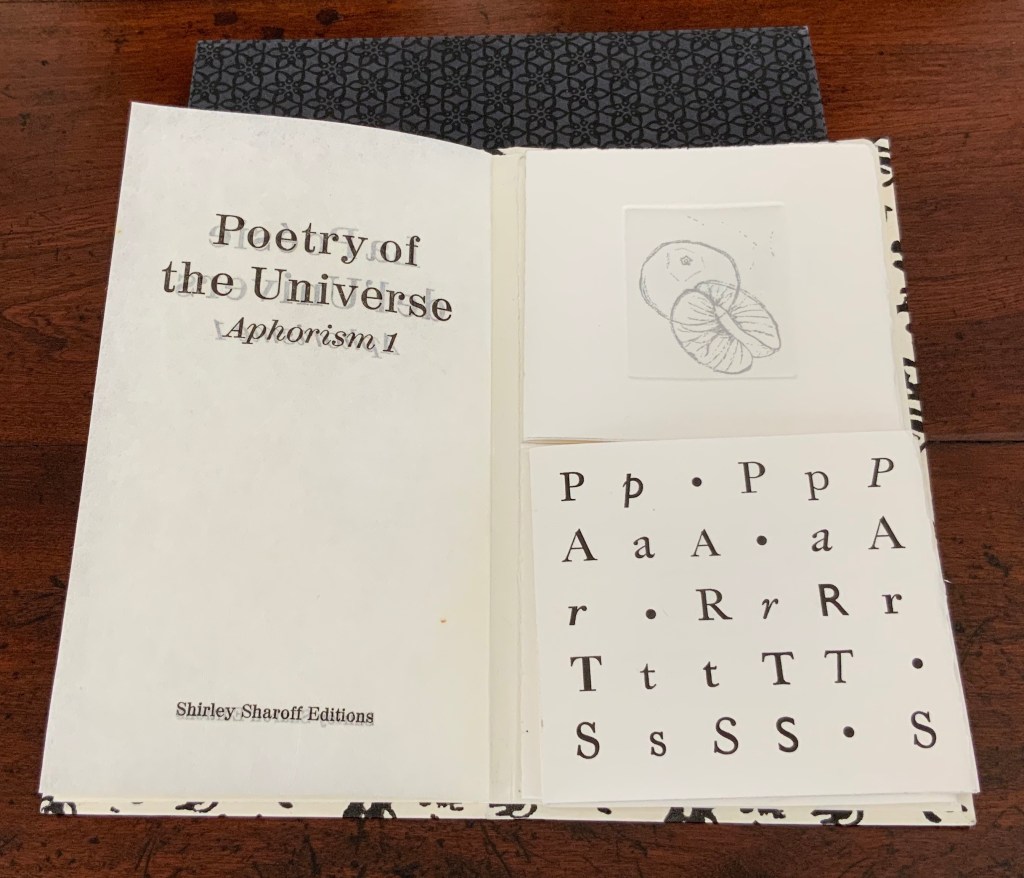

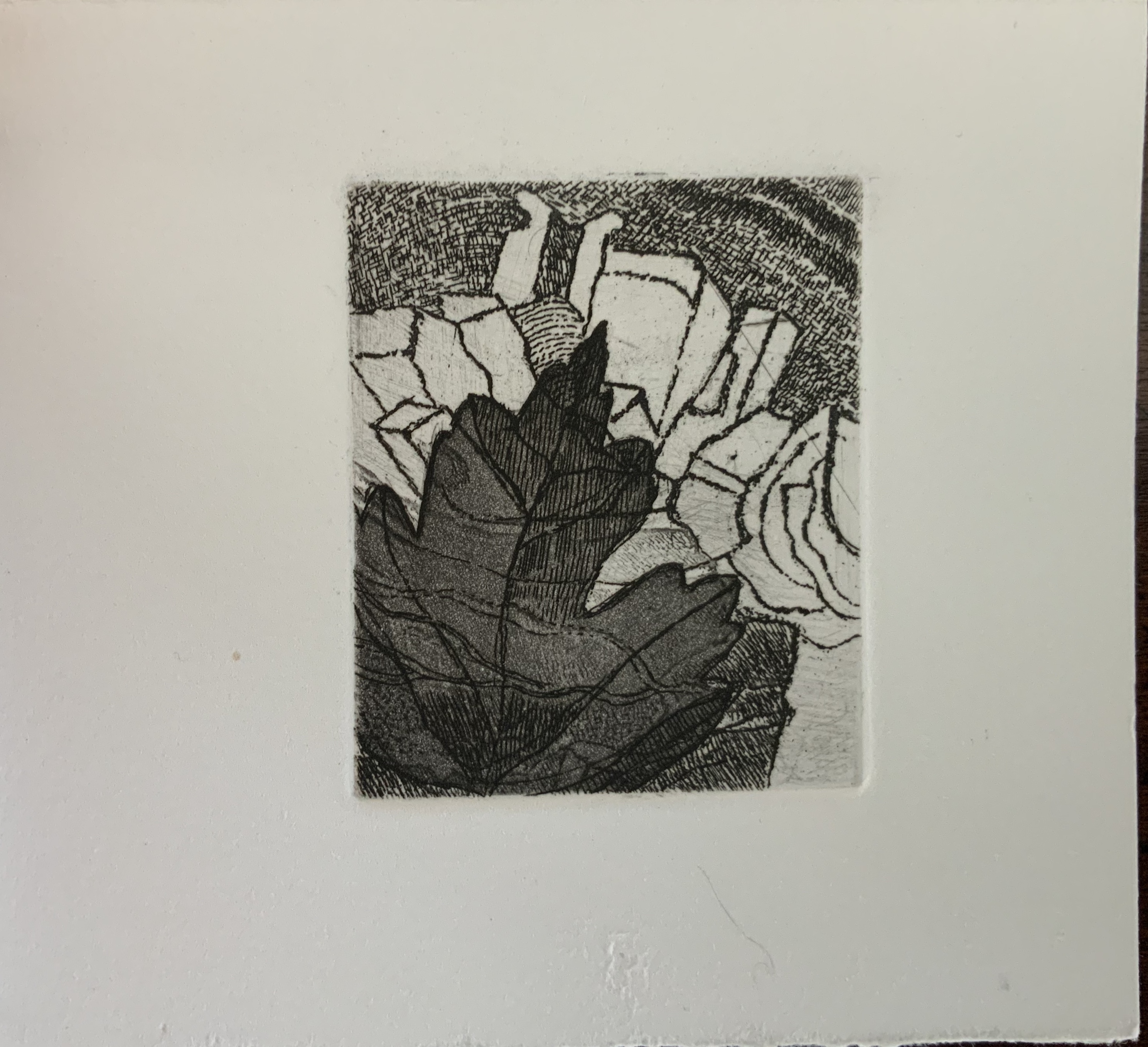

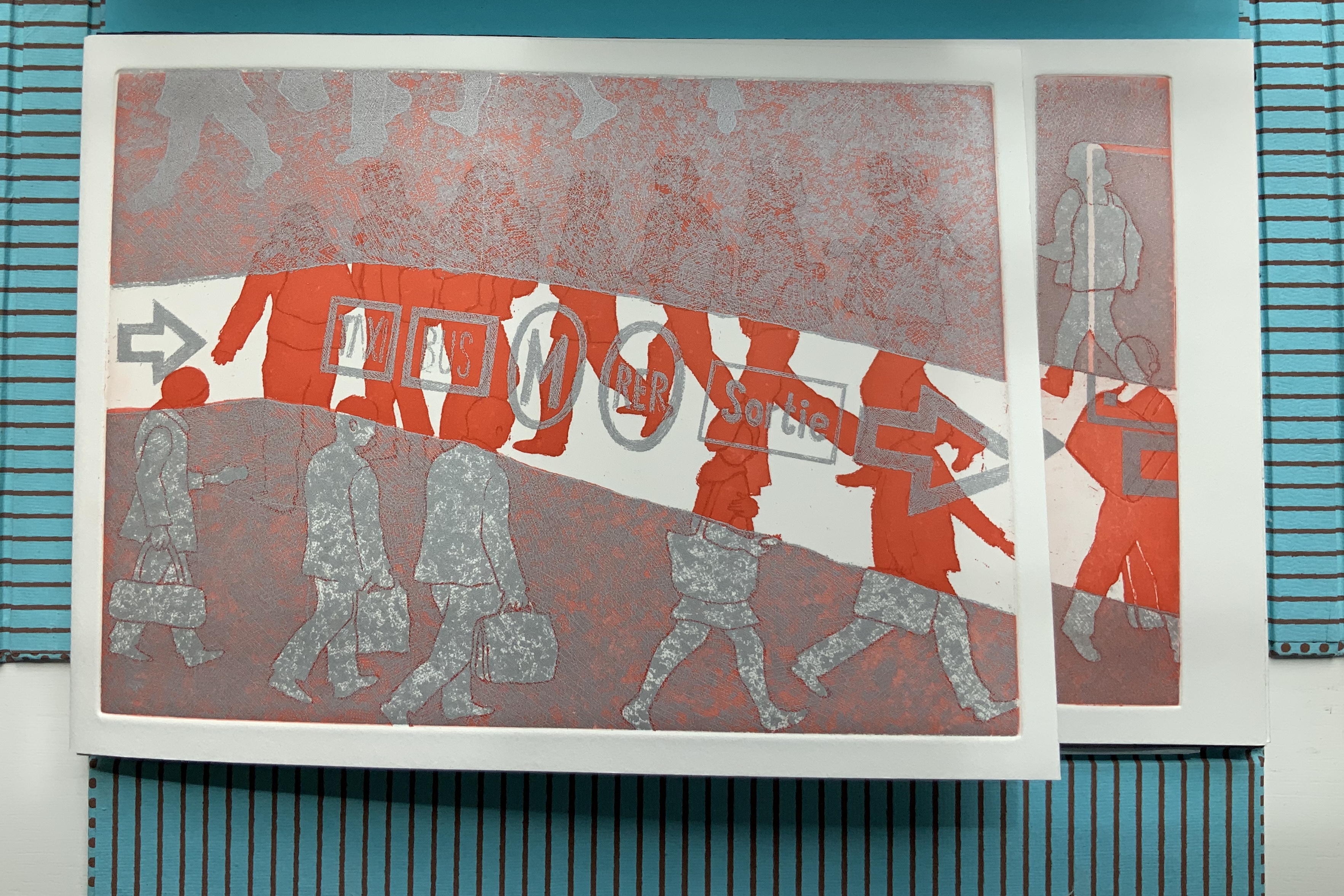

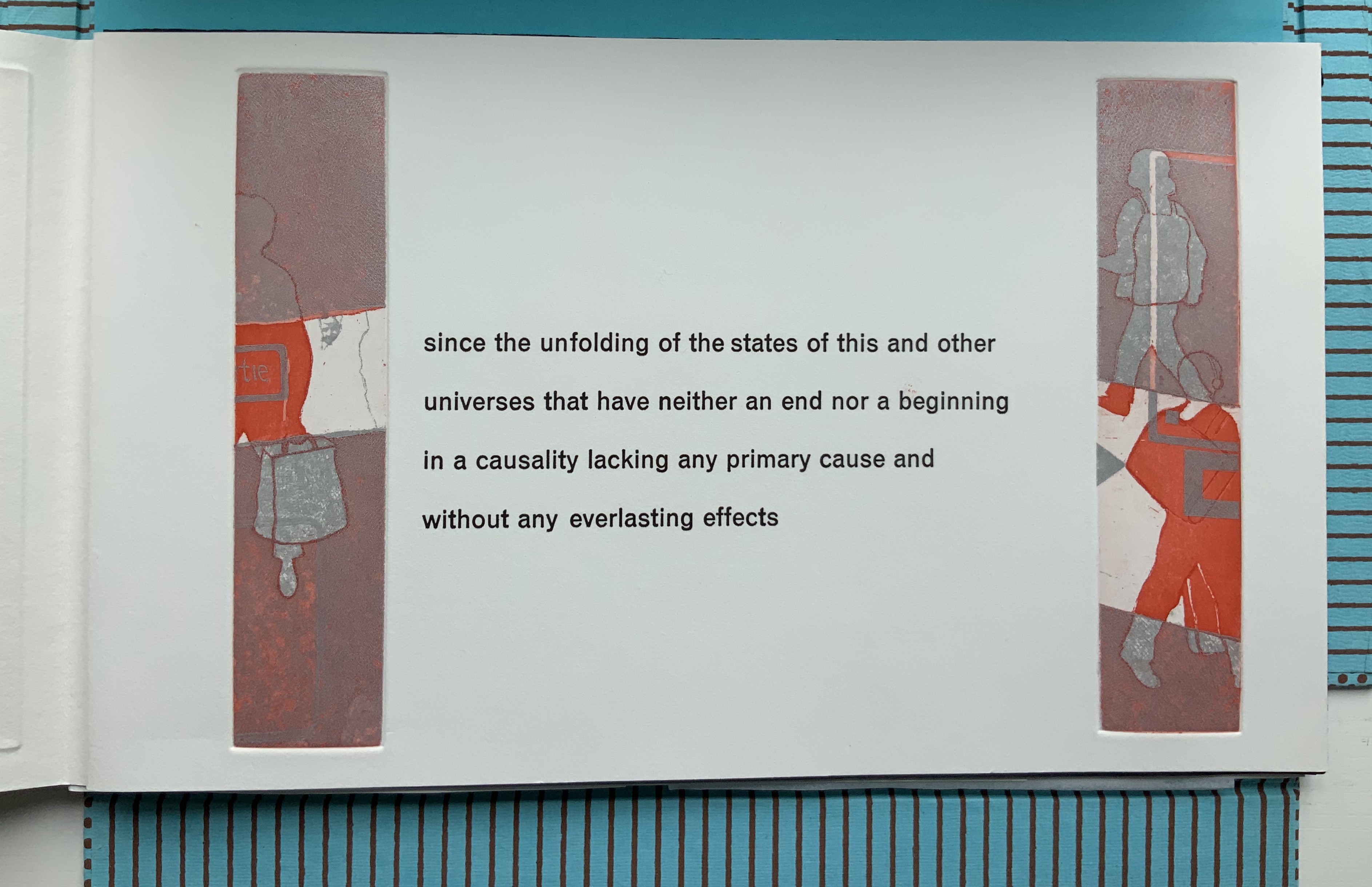

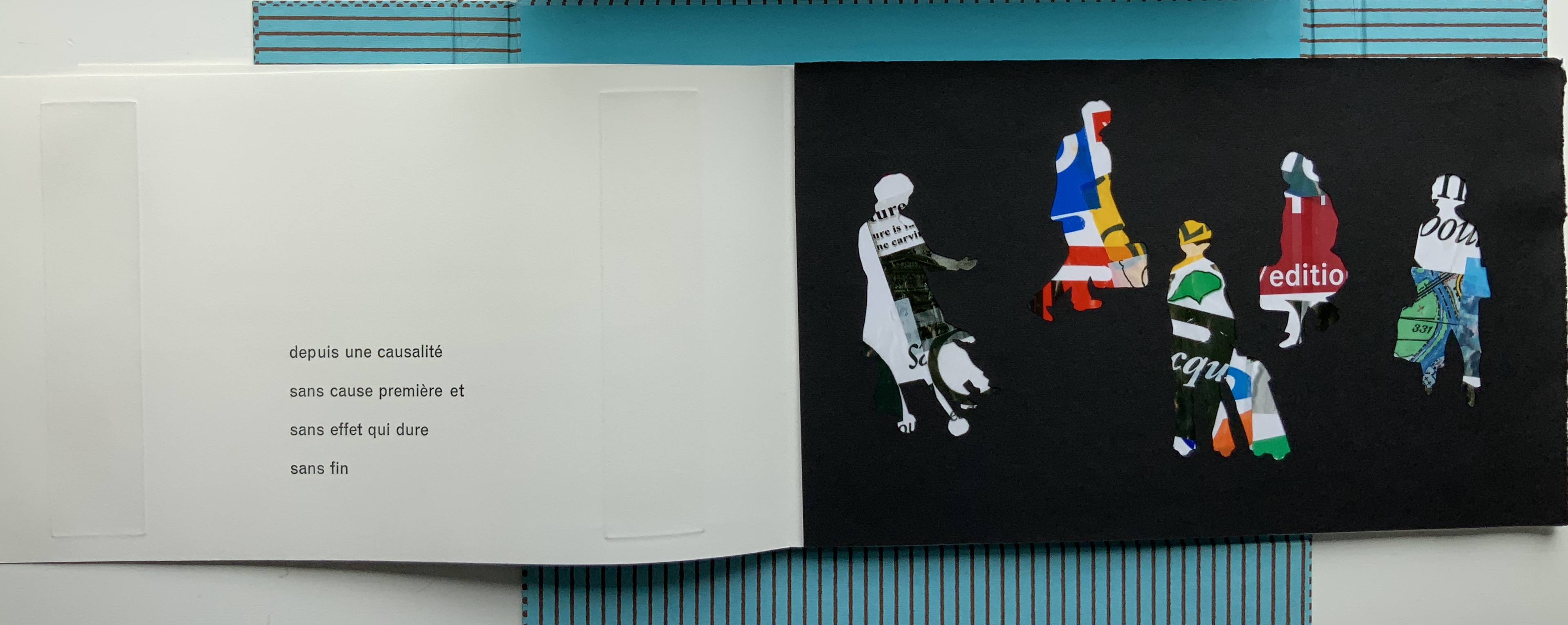

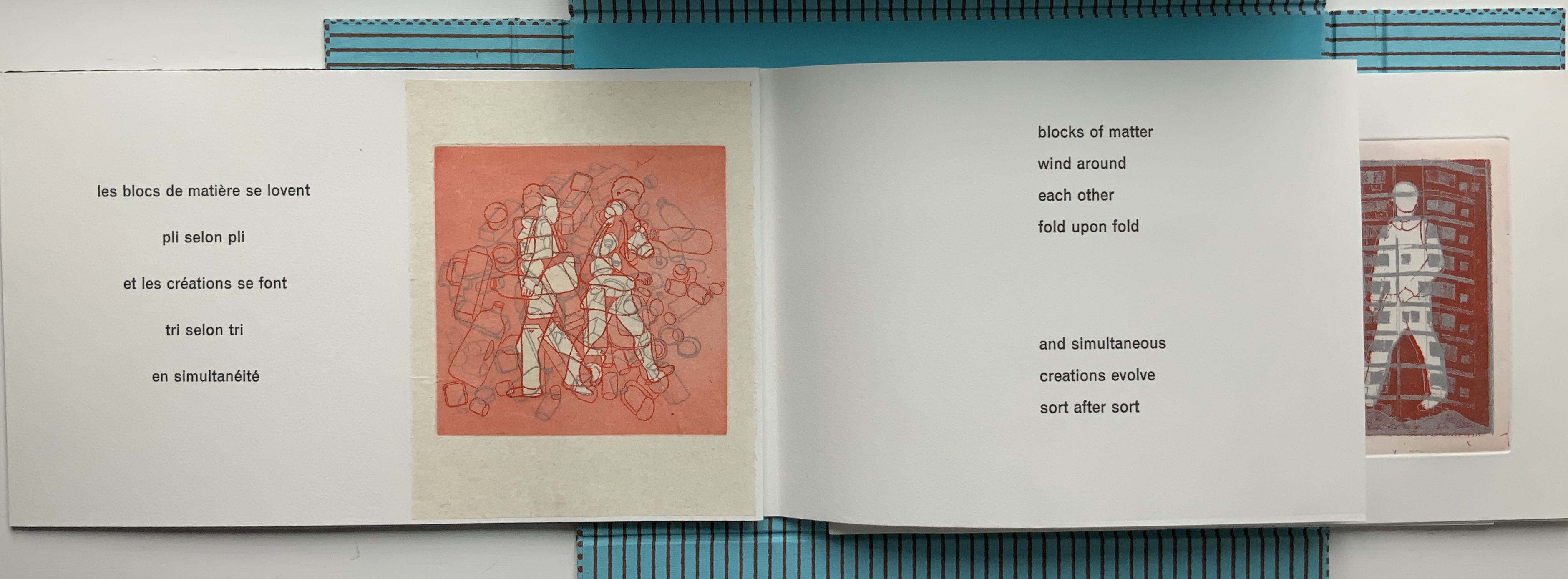

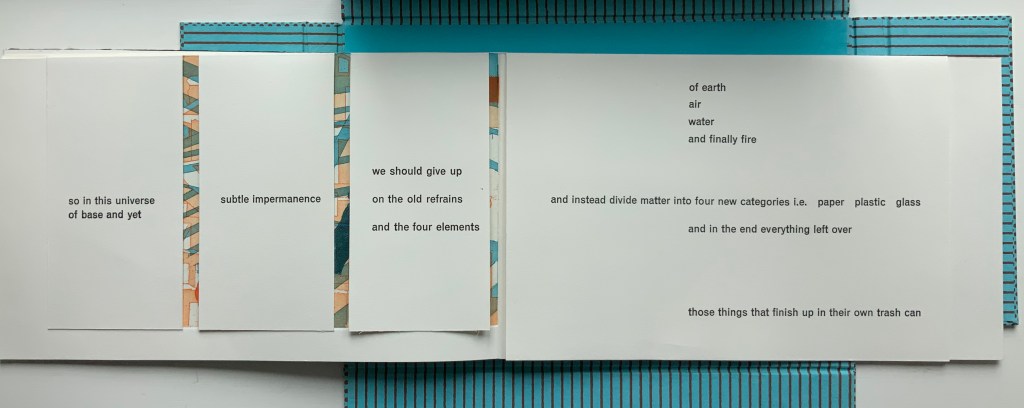

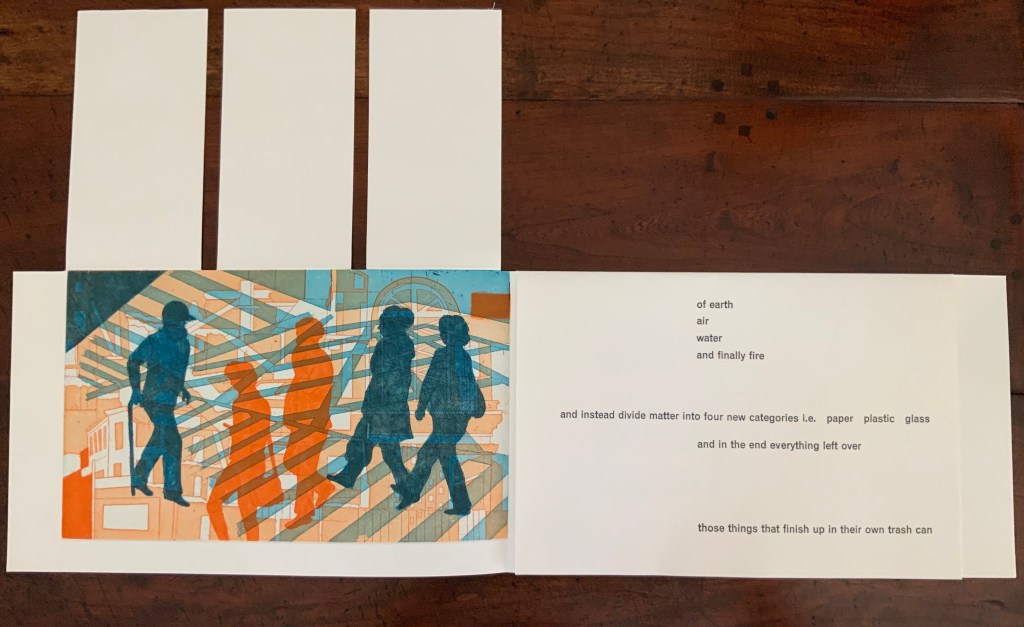

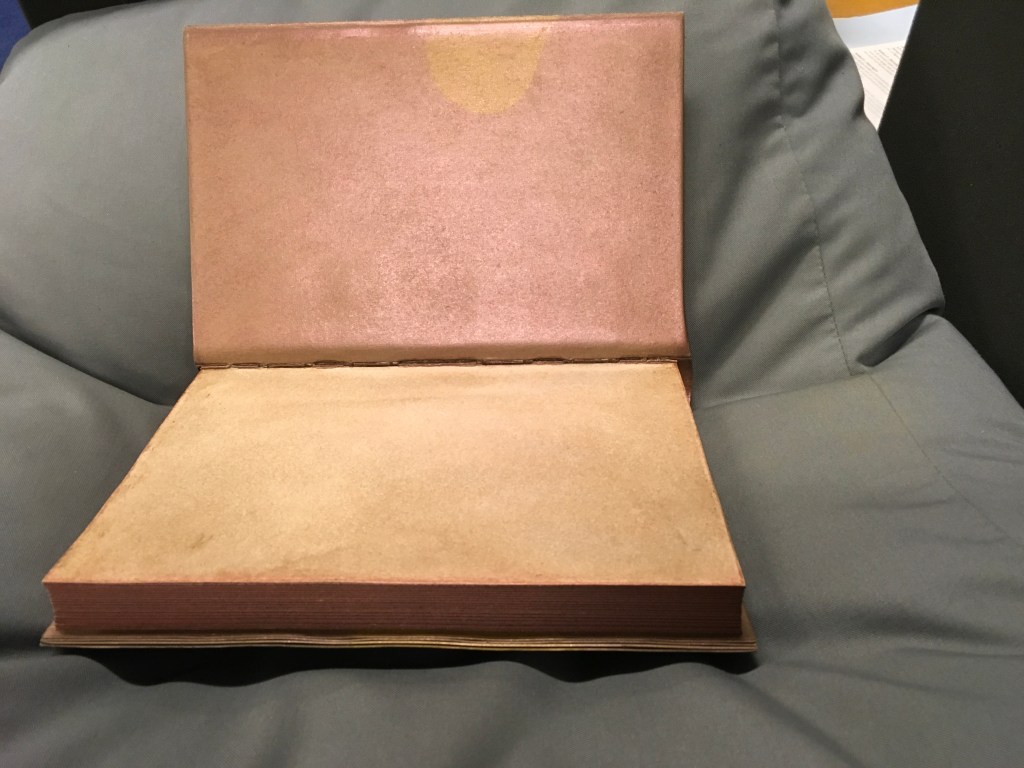

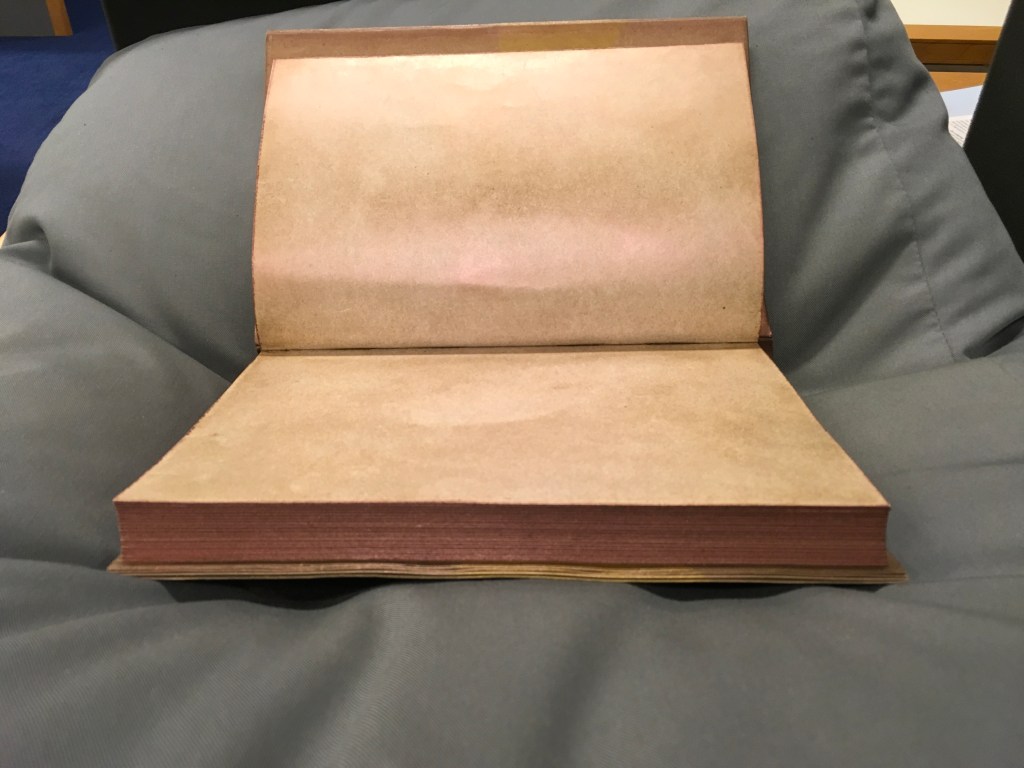

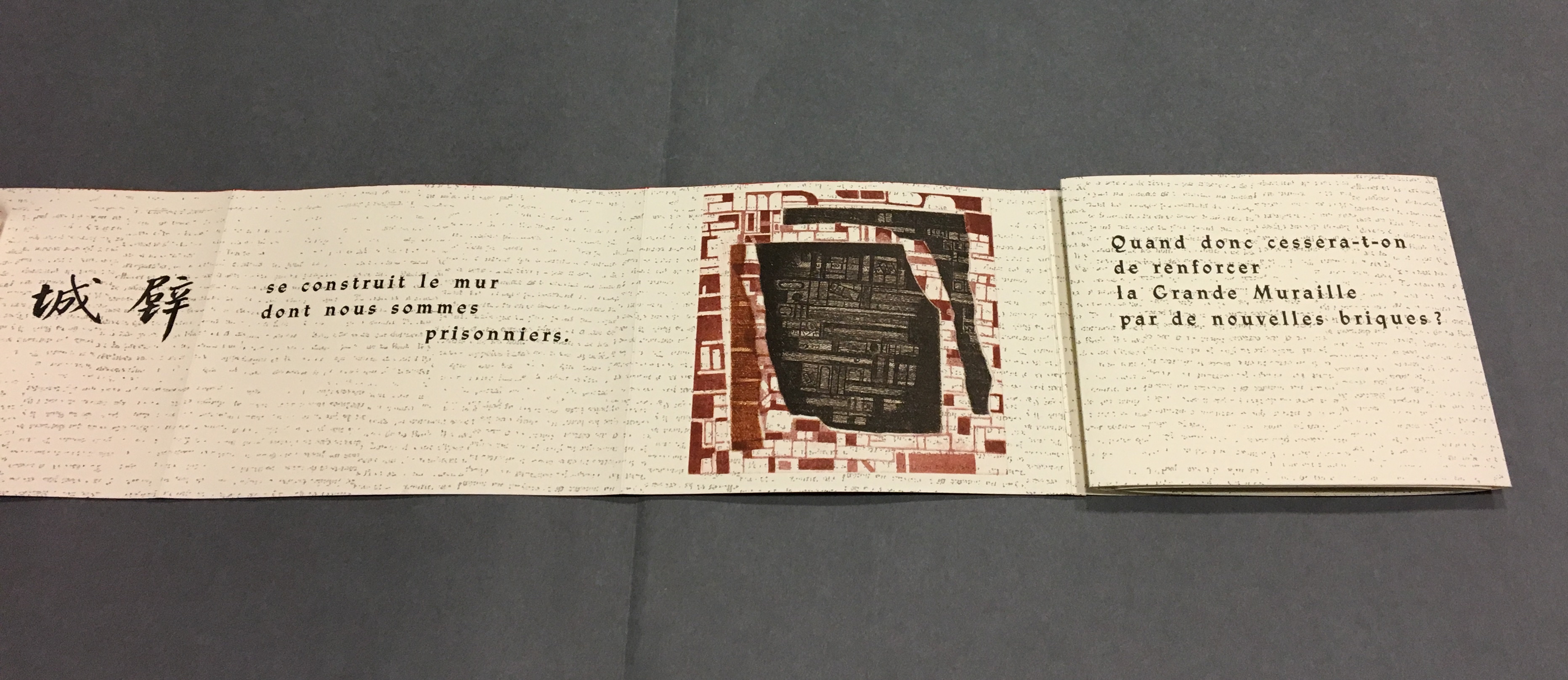

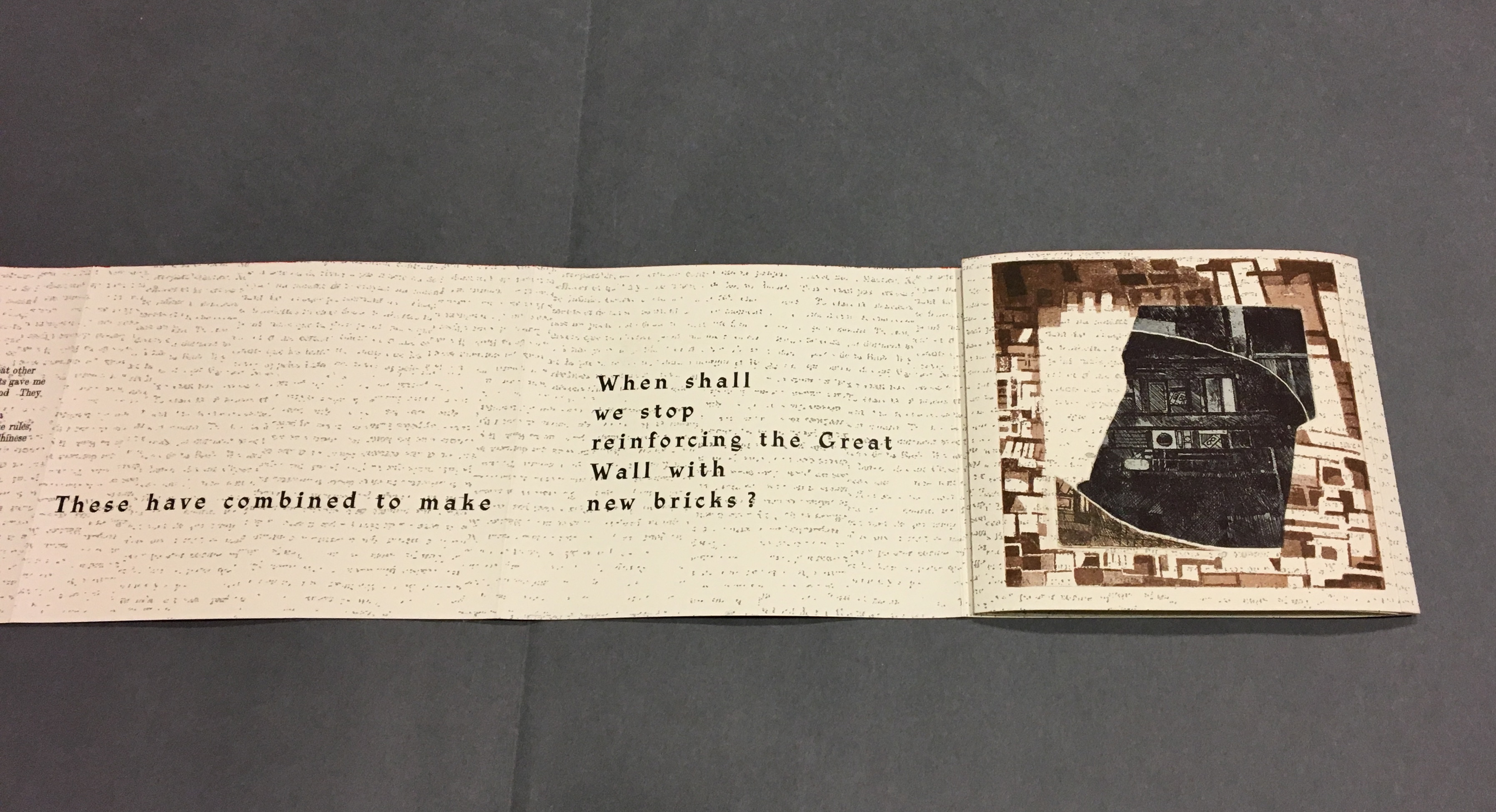

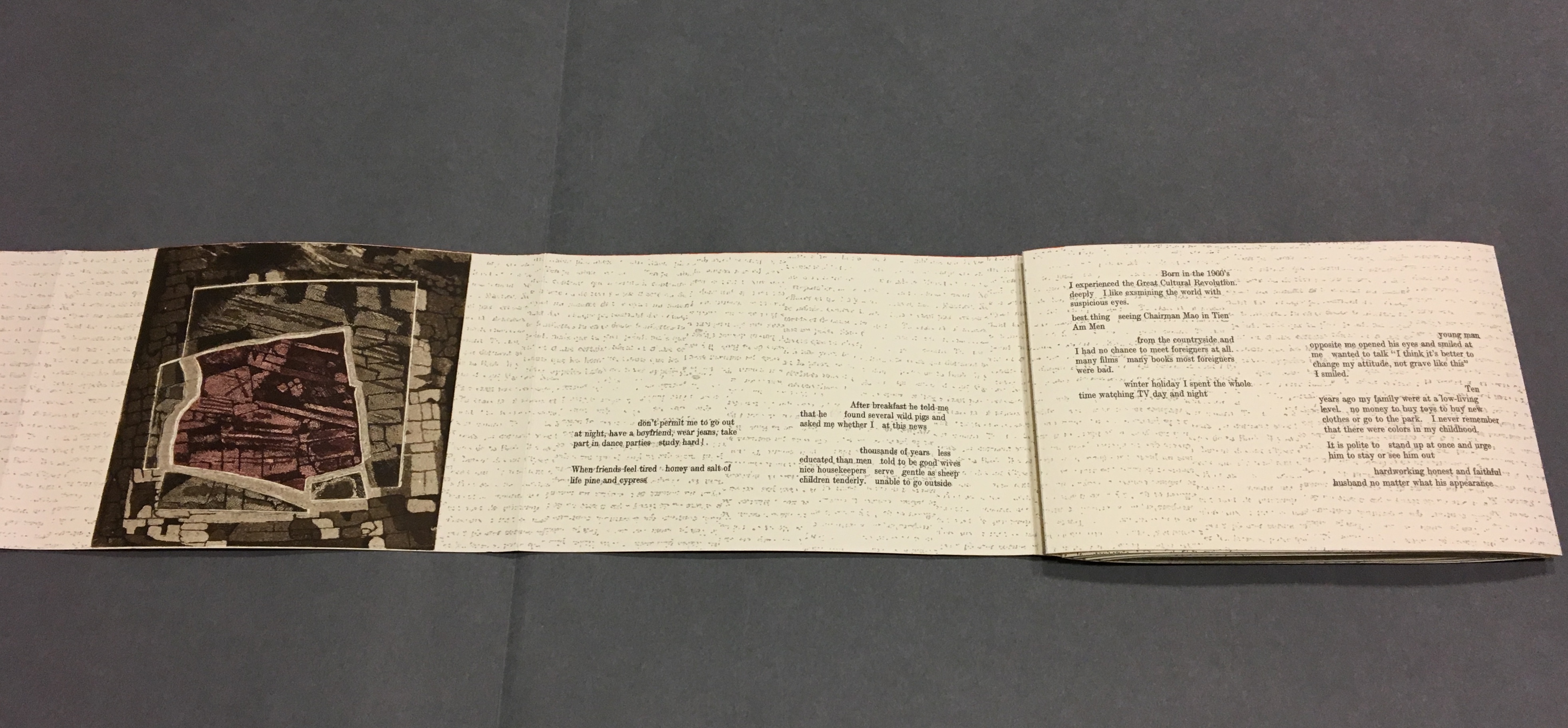

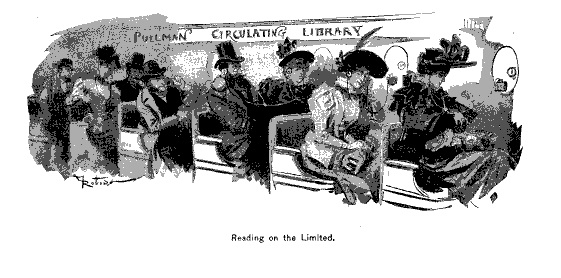

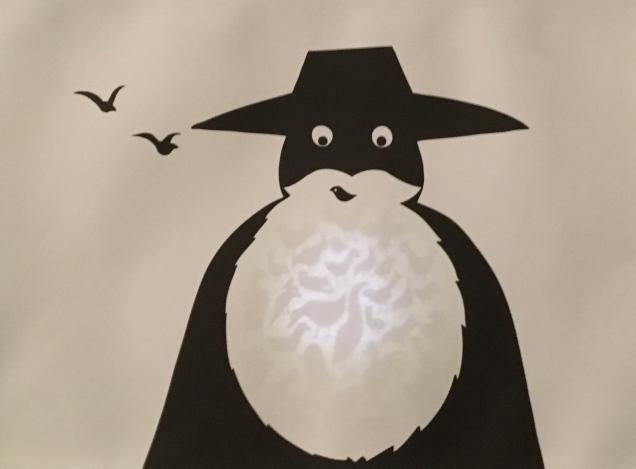

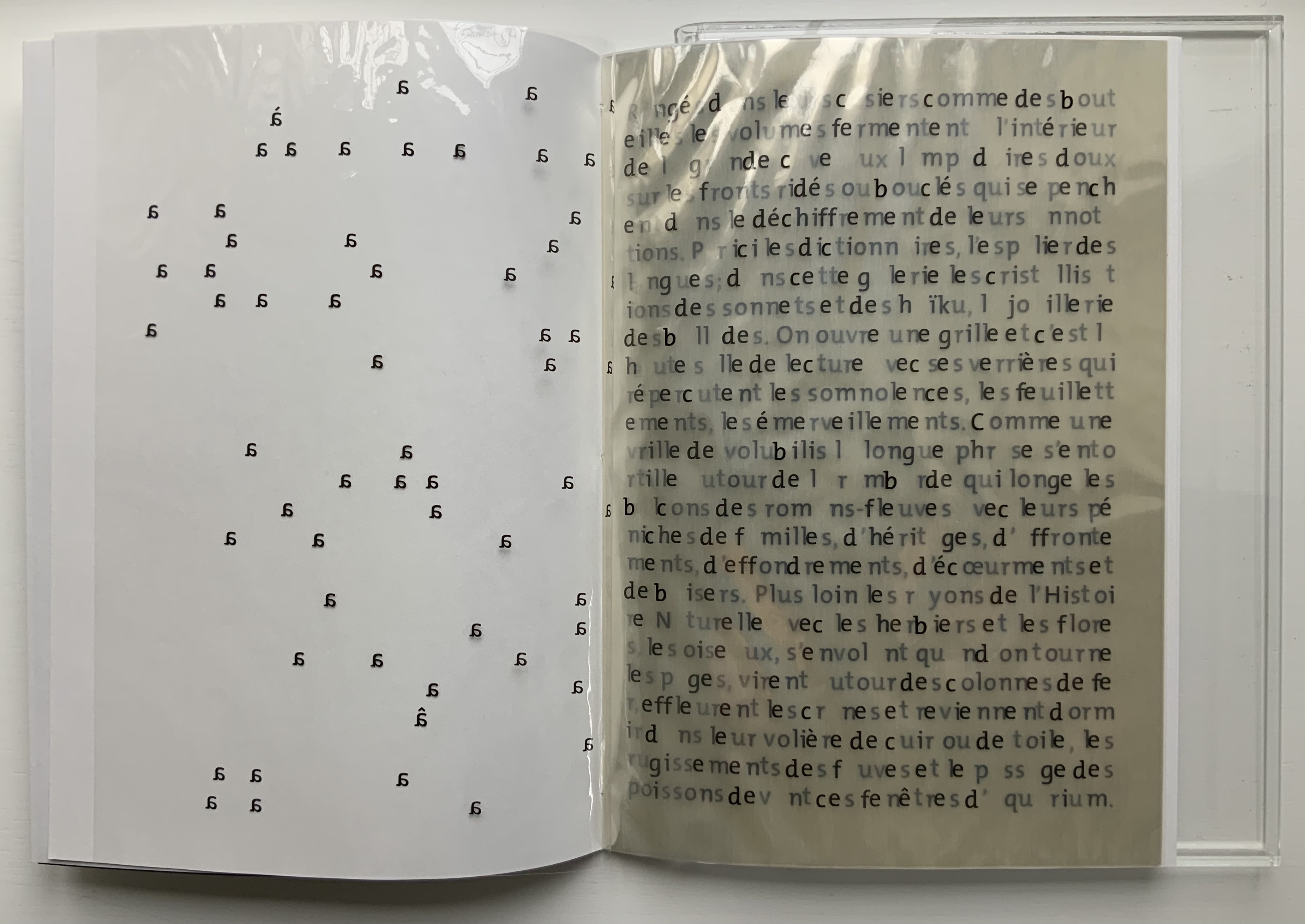

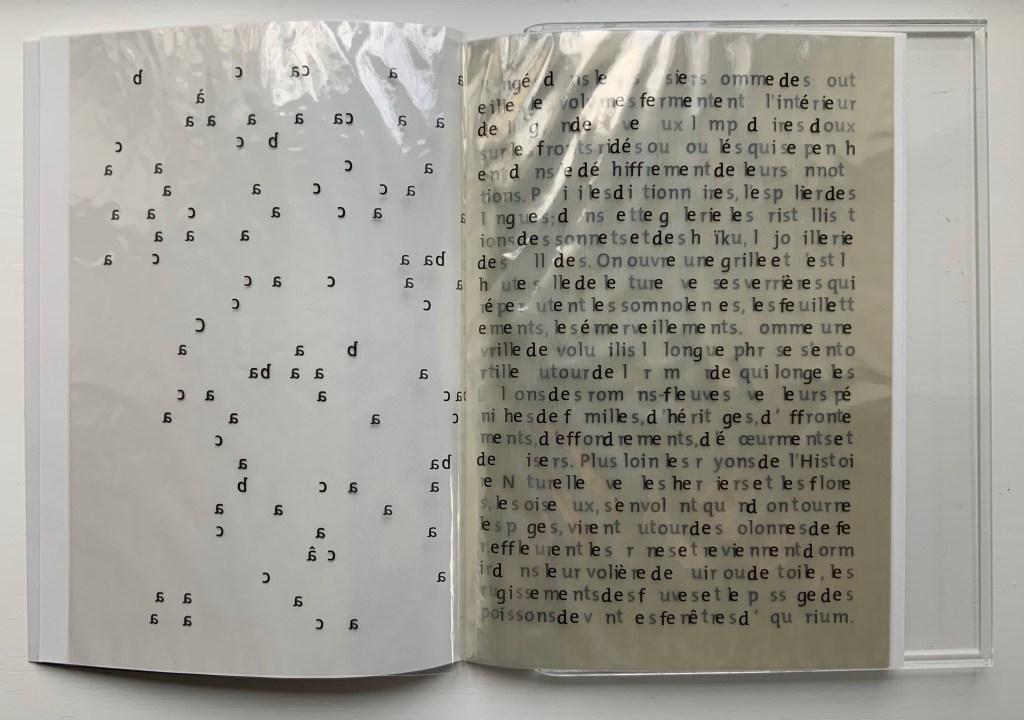

With Alpha Beta, we are reader, spectator, listener and actor. Its plexiglas slipcase must be shaken sharply to start the two thin volumes slipping out. On acetate, the first recto page presents an extract from an essay by Michel Butor describing a fantastical library. The acetate pages crinkle and mesmerize as they turn. Alphabetically, letter by letter, the transparency lifts from Butor’s text all the instances of that sans serif character into the air, falls leftward and settles onto the accumulation of clear verso pages showing the letters reversed.

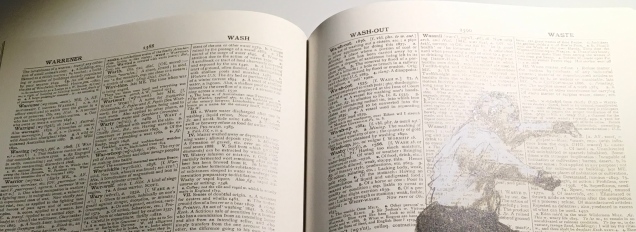

Traditionally the cellophane or transparent overlay and their predecessor the “flap book” were meant to reveal the layers of the human body, a geological formation or an edifice — to show us how something is made or built up. With an alphabet and punctuation, an infinite number of words, sentences, essays and books can be made. In Alpha Beta, however, as letter by letter is removed, what was made becomes indecipherable, disintegrates. Page by page, what was there depends on memory, or the eye’s ability to decipher from what is left, or a willingness to flip back to the beginning. We know, of course, that Butor did not piece together his disintegrating text letter by letter alphabetically in the first place, but materially and typographically that is what von Ketelhodt did to present the full text to us on the first recto page. If we return to that page to fix the text in memory, we notice that not only is it justified left and right, its words break at the end of a line without hyphenation or regard for syllabification. This is not typography in transparent service to legibility but rather to its own materiality and a concept or concepts. But what is it, what are they?

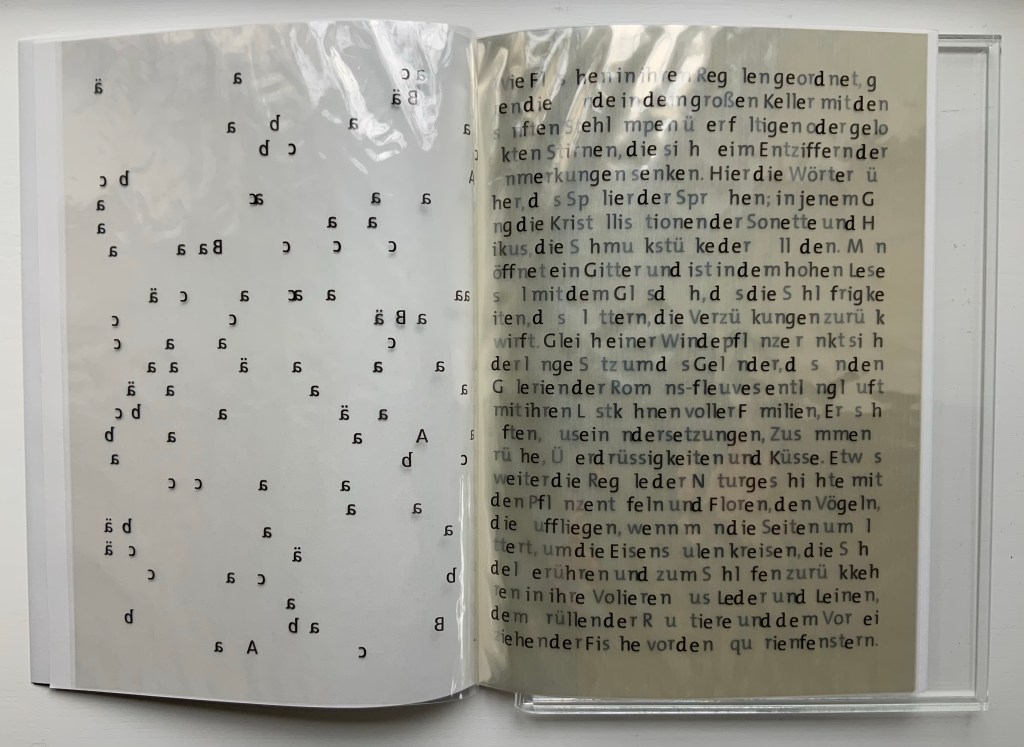

Just as strange is that Alpha Beta is materially multilingual. The first volume, Alpha, presents and disintegrates Butor’s text in its original French. The second, Beta, does the same in German.

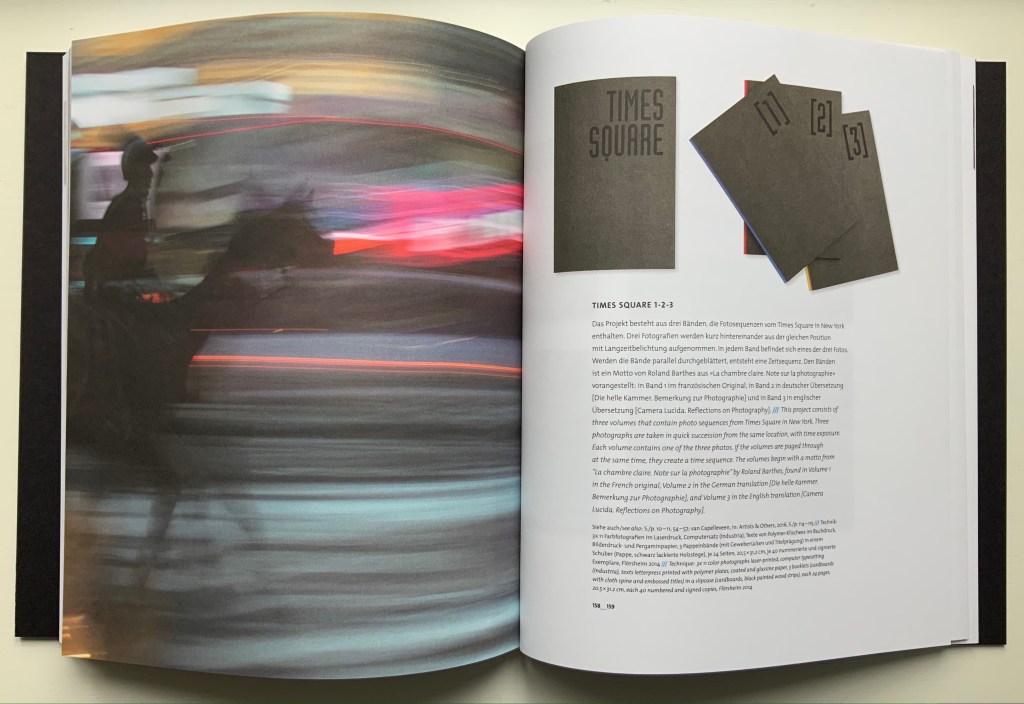

Why this multilingual materiality? Could it be the advantage of appealing to two language markets? Could it be as simple as the text’s being available in French and German? There’s no denying von Ketelhodt’s multilingual proclivity. Many of her solo works involve multiple languages, but it is how and why that count. Consider her sequential photographic work Times Square 1-2-3 (2014). In it, she uses a quotation from Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography in its French original for volume 1, German for volume 2, and English for volume 3. Von Ketelhodt took three photos in quick succession, with time exposure, from the same spot in Times Square. She then split the photos across the three volumes. To see the sequence, we have to look across the three volumes. By virtue of its focus on the effects of photography on the spectator and its availability in three languages, Camera Lucida was the ideal source from which to draw a quotation as inspiration and compositional material for Times Square 1-2-3.

So why this particular text from Michel Butor? A bilingual market advantage was probably decisive for Campus Verlag, publisher of Butor’s volume of essays in which von Ketelhodt found the text. If a trilingual market advantage had outweighed the additional production costs for Campus Verlag, von Ketelhodt might have created Alpha Beta Gamma instead. The essay she selected from Butor is “Les bibliothèques/Die Bibliotheken” (“The libraries”), which appears in the collection’s second part: “Itinéraires à travers l’univers de Maria-Helena Vieira da Silva/Reiserouten durch das Universum von Maria-Helena Vieira da Silva” (“Itineraries through the universe of Maria-Helena Vieira da Silva”). None of Butor’s essays are about the alphabet. So, still, why this particular text?

Butor wrote extensively in response to Da Silva’s works. A French-Portuguese abstract/figurative artist, she drew on cityscapes, railway stations, bridges as well as books and libraries for her source of figures. The libraries led to a series of canvases with titles such as Bibliothèque Humoristique, La Bibliothèque, and La bibliothèque en feu. The latter appears dimly reflected in the upper left-hand corner of this photograph from the Paris exhibition La Pliure (2015). A clearer image can be found on the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum’s site.

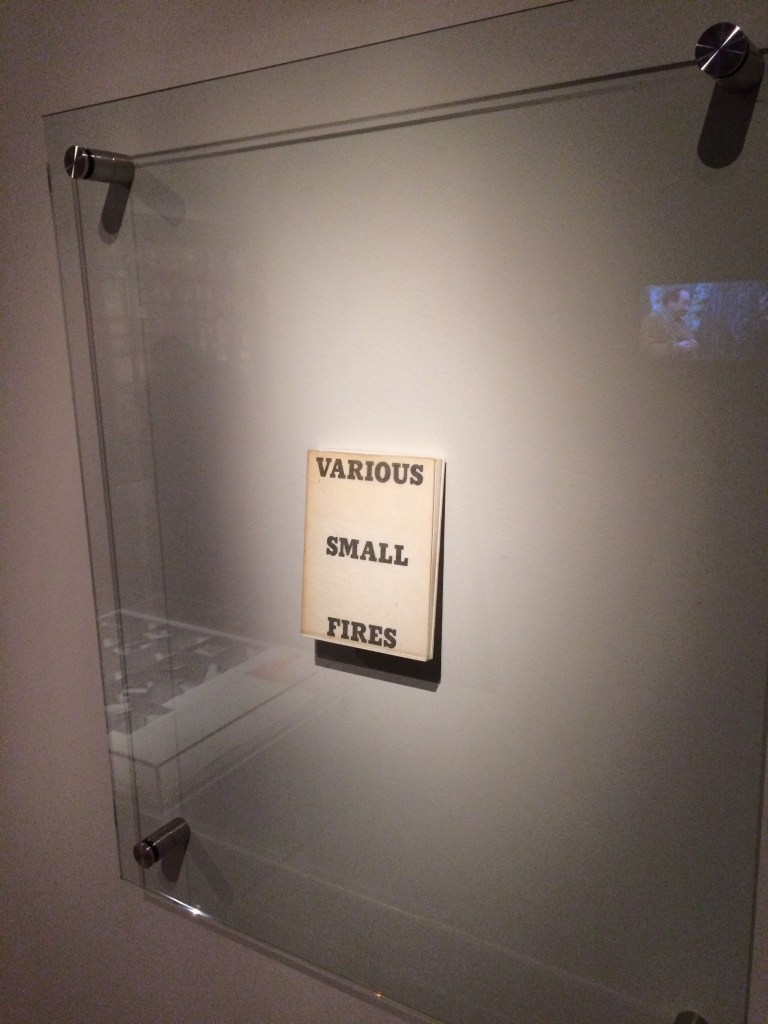

Display of Ed Ruscha’s Various Small Fires and Milk, 1964, at Pliure: La Part du Feu, 2 February – 12 April 2015, Paris. Photo: Books On Books. Reflected in the lower left hand corner is the display of Bruce Nauman’s Burning Small Fires; in the upper right corner, the film clip of Truffaut’s 1966 Fahrenheit 451; and in the upper left, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva’s La bibliothèque en feu, 1974.

In its capture of Bruce Nauman’s referencing Ed Ruscha’s Various Small Fires, the photo is serendipitously apropos to Alpha Beta and its use of Butor’s “Les bibliothèques”. Butor’s essay is ekphrastic, built on the premise of referencing a visual artwork. It does not, however, describe the details of any particular one of the paintings; it is rather a fantasia on all of them, distilling them into a universal library. Von Ketelhodt’s ABC book is built on the very premises of Butor’s extract as well as on the premise of referencing the subject of Butor’s essay. Alpha Beta does not describe Butor’s essay; rather, it physically reaches into the text, extracts and abstracts from it an ABC book letter by letter. As the letters fly up, they could be those “birds that fly upward when you turn the pages”. The light reflected from the transparent pages could be that of the “soft lamps hovering”. The transparent pages recall the libraries’ “crystalline sonnets” and their “glass ceiling that reflects back the drowsiness, the leafing”. (See full English translation under Further Reading below.)

Von Ketelhodt’s work of art is far from an illustration of Butor’s universal library just as Butor’s essay is far from a verbal attempt to describe any one of Da Silva’s paintings. If this response to Alpha Beta seems “too clever by half”, consider the multilingual, self-referencing and self-referential complexity of the next work in the collection.

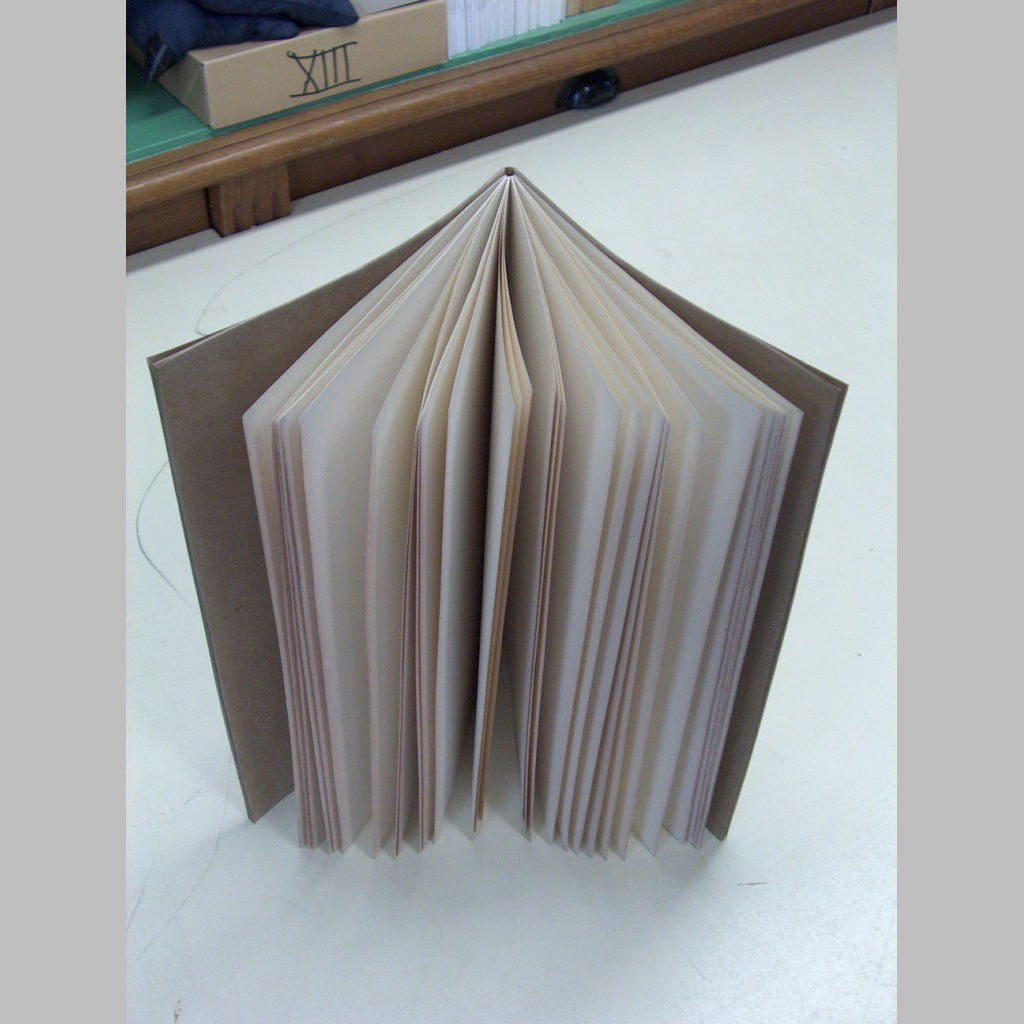

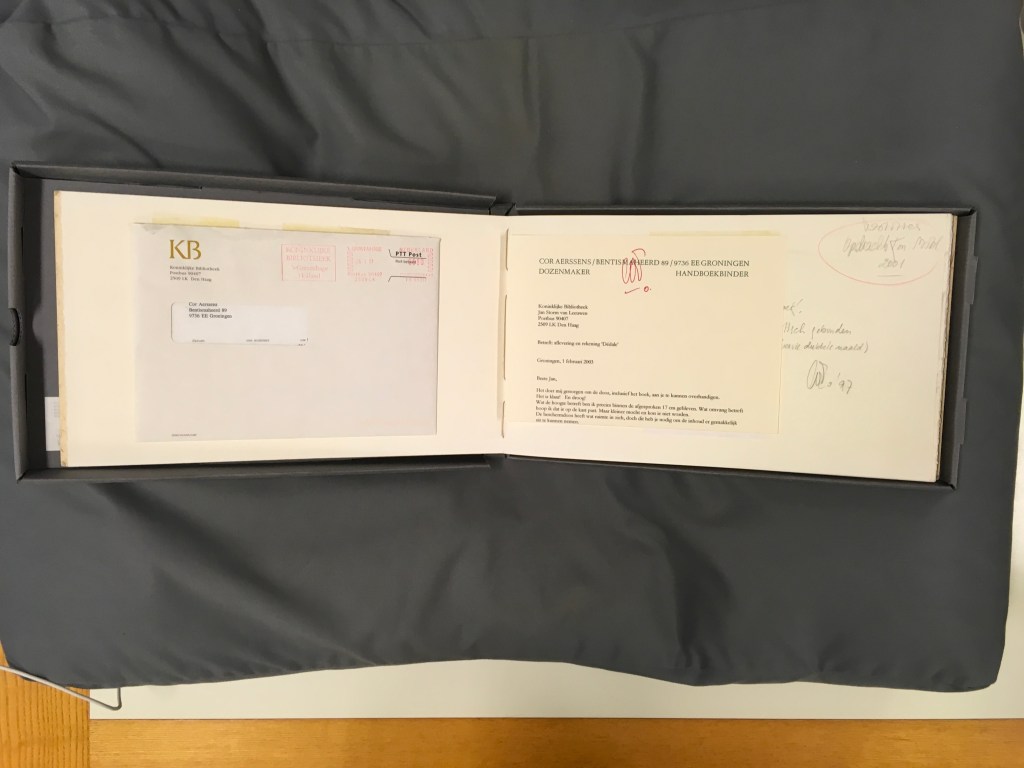

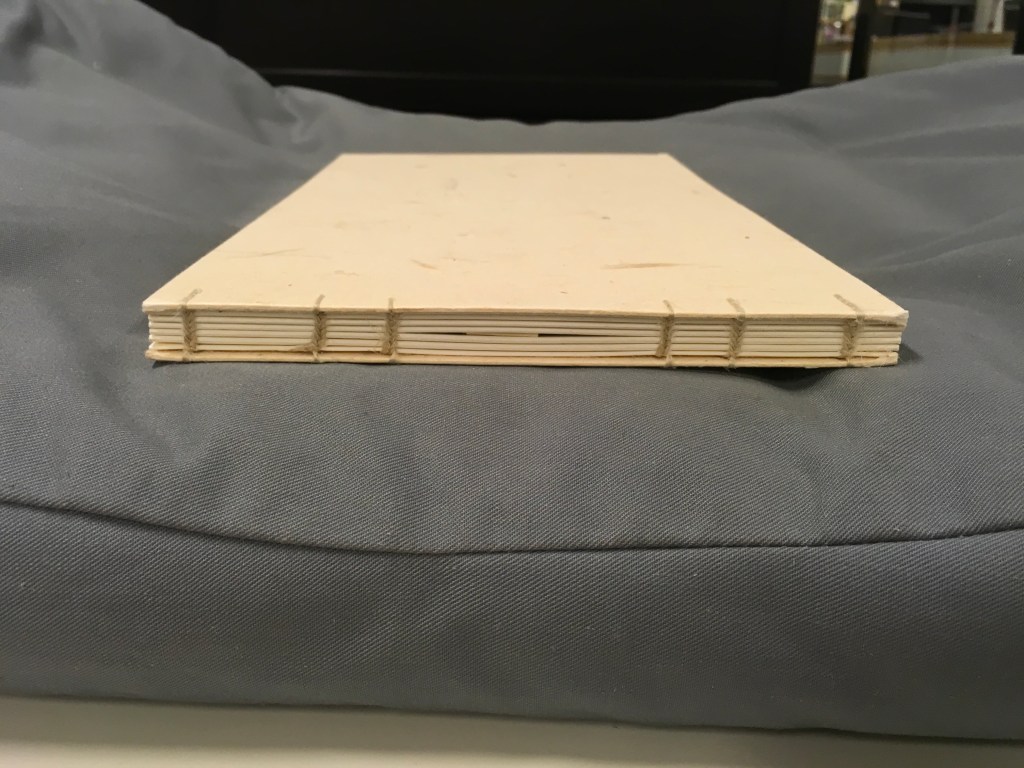

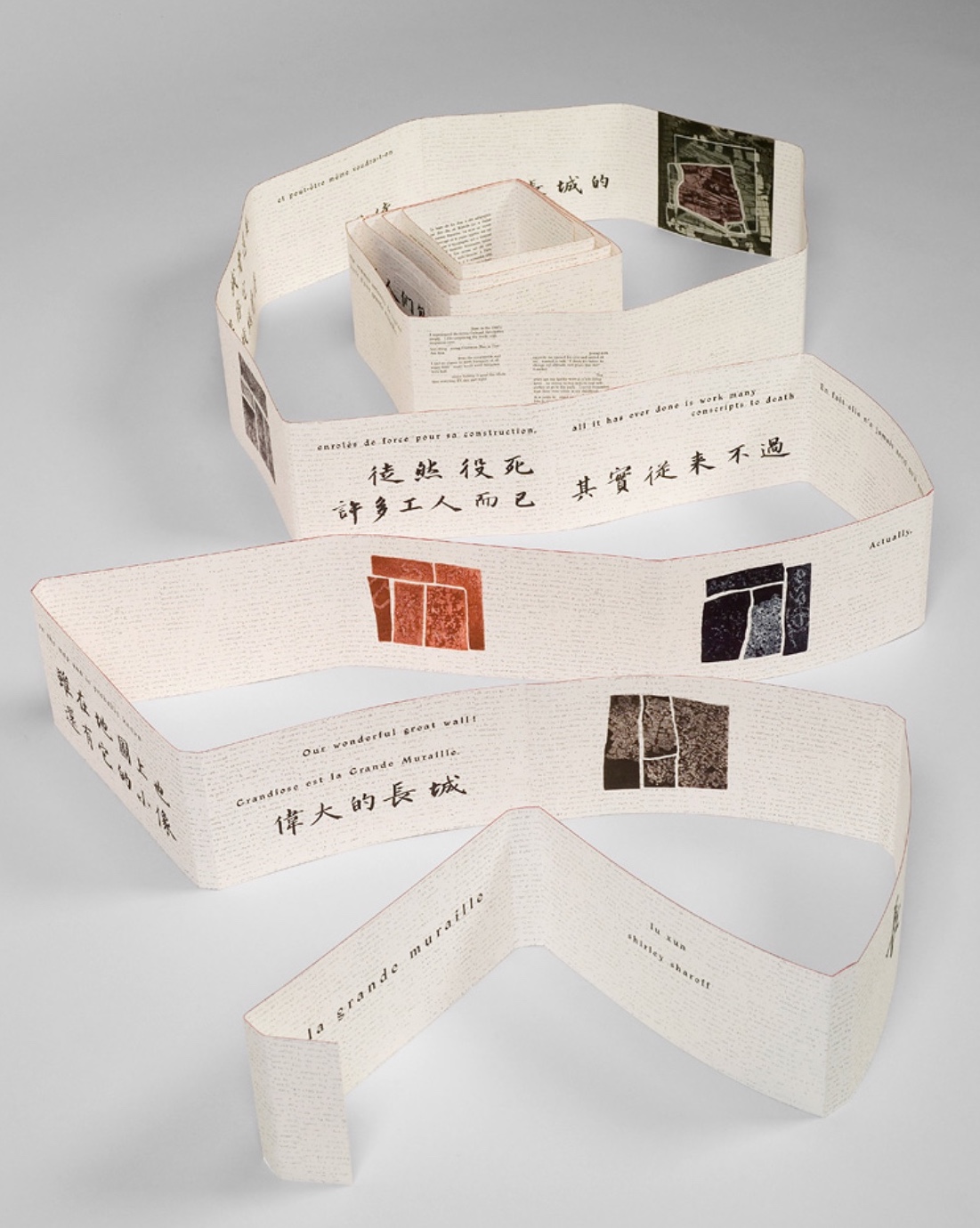

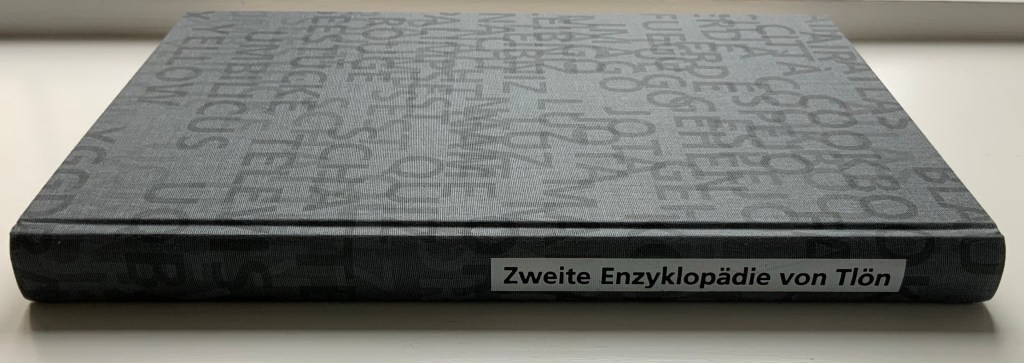

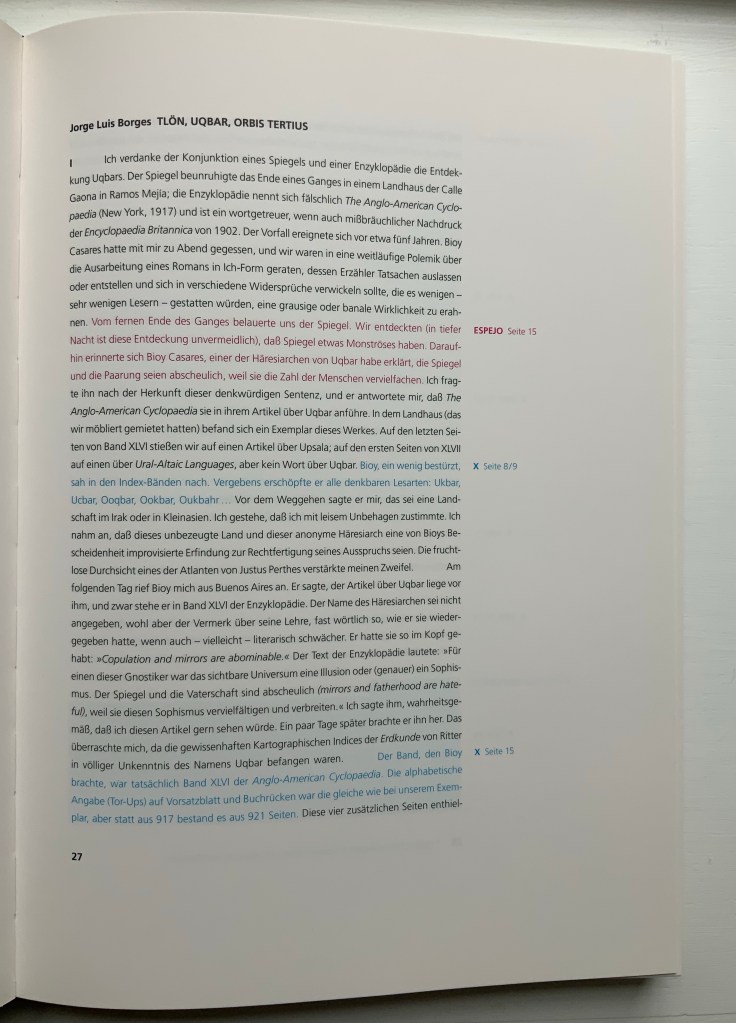

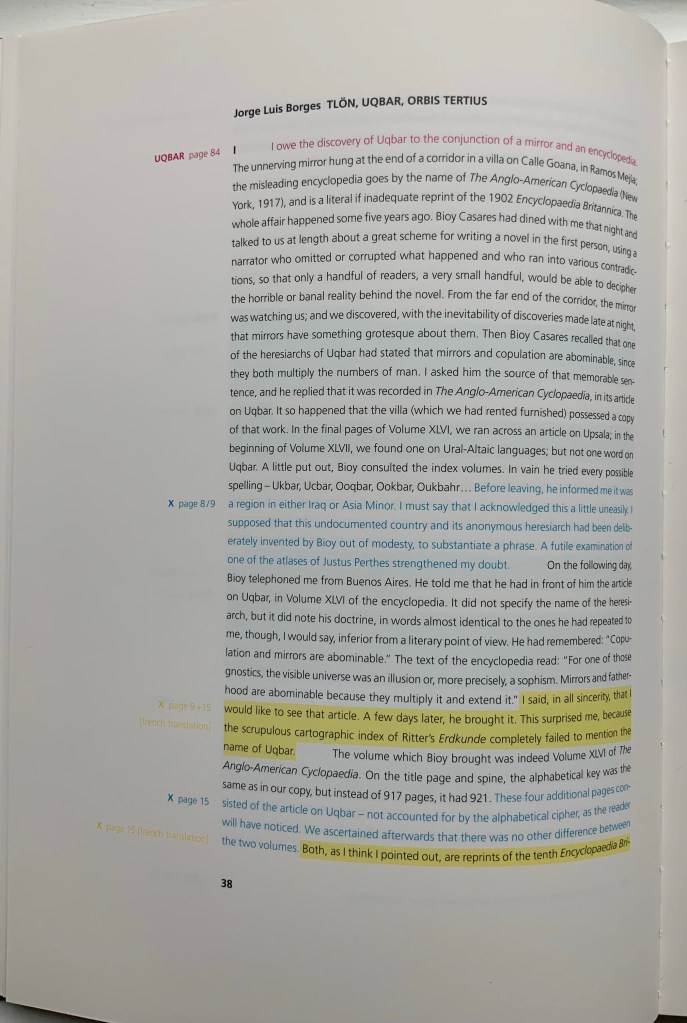

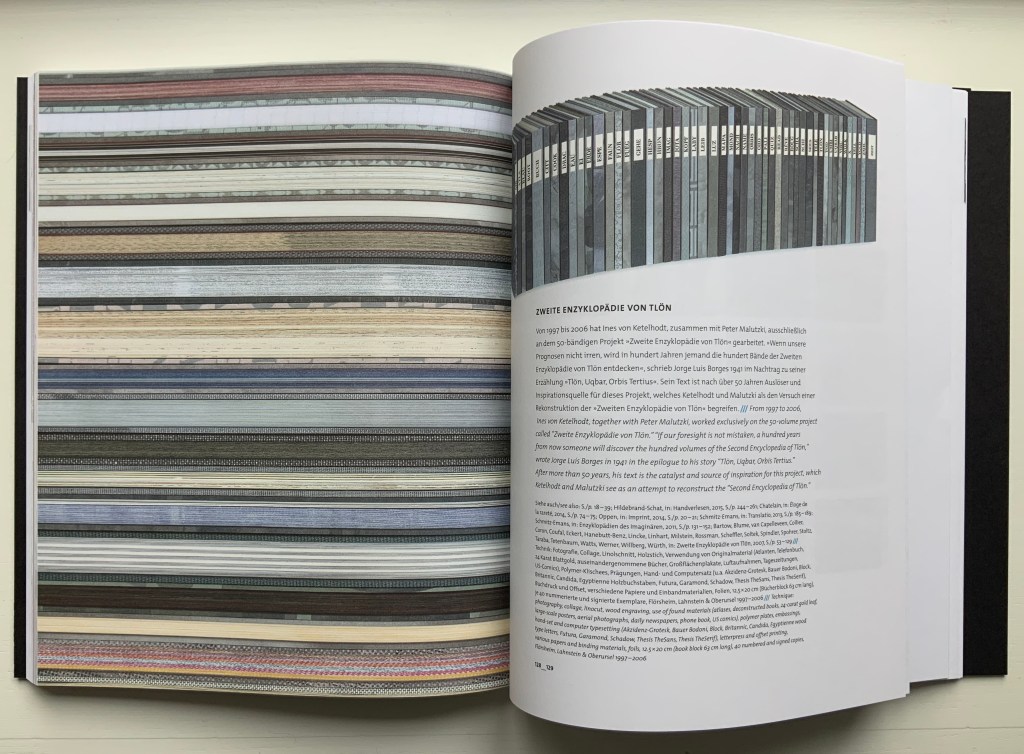

Zweite Enzyklopädie von Tlön (2007)

Zweite Enzyklopädie von Tlön (2007)

Ines v. Ketelhodt and Peter Malutzki

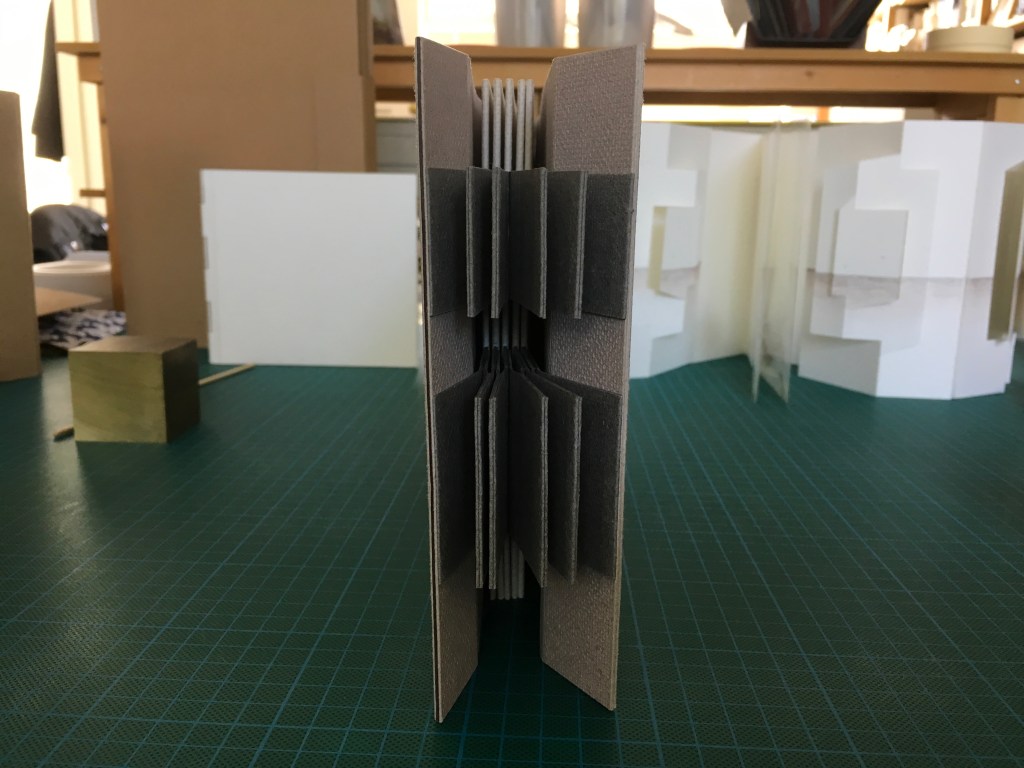

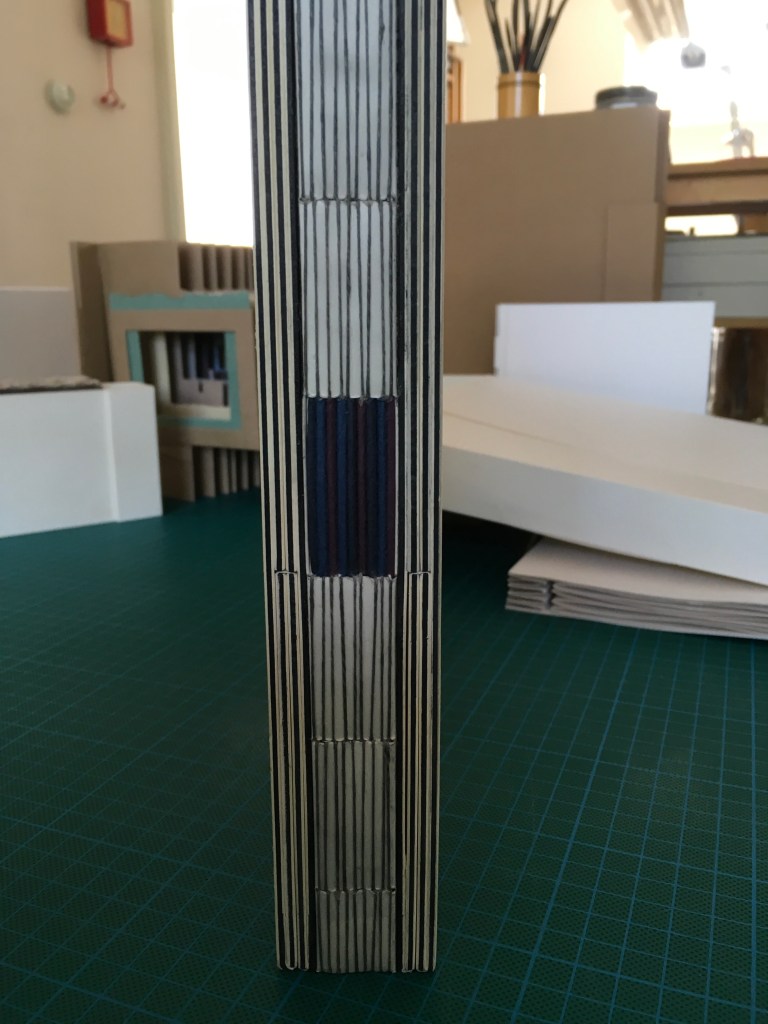

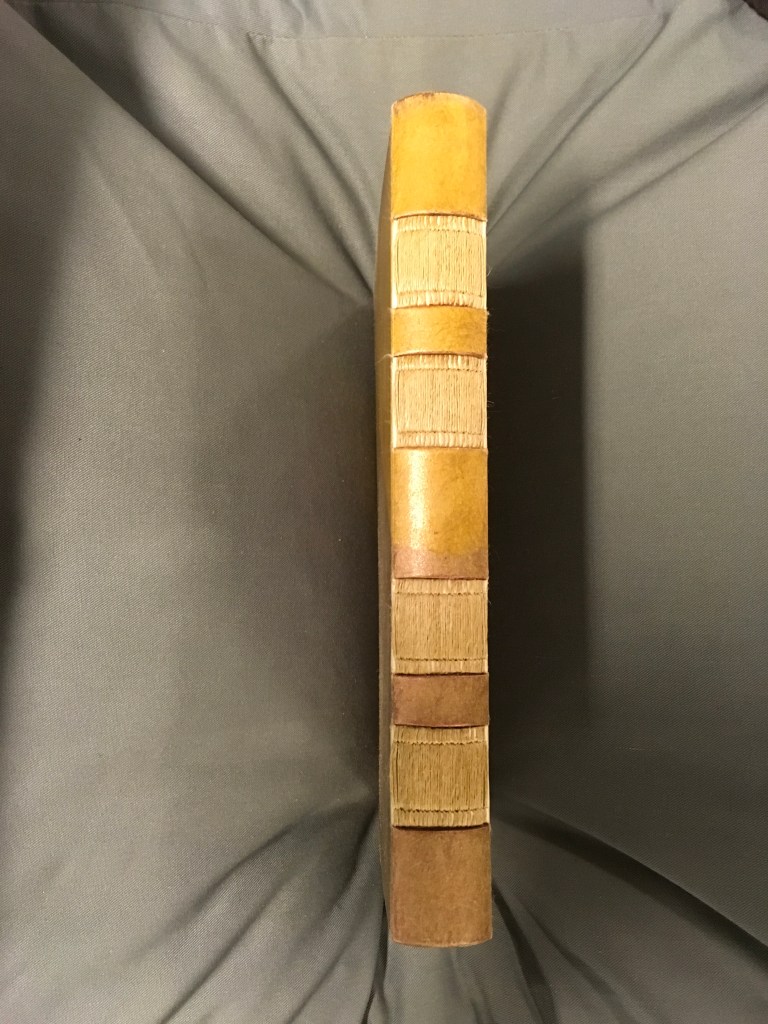

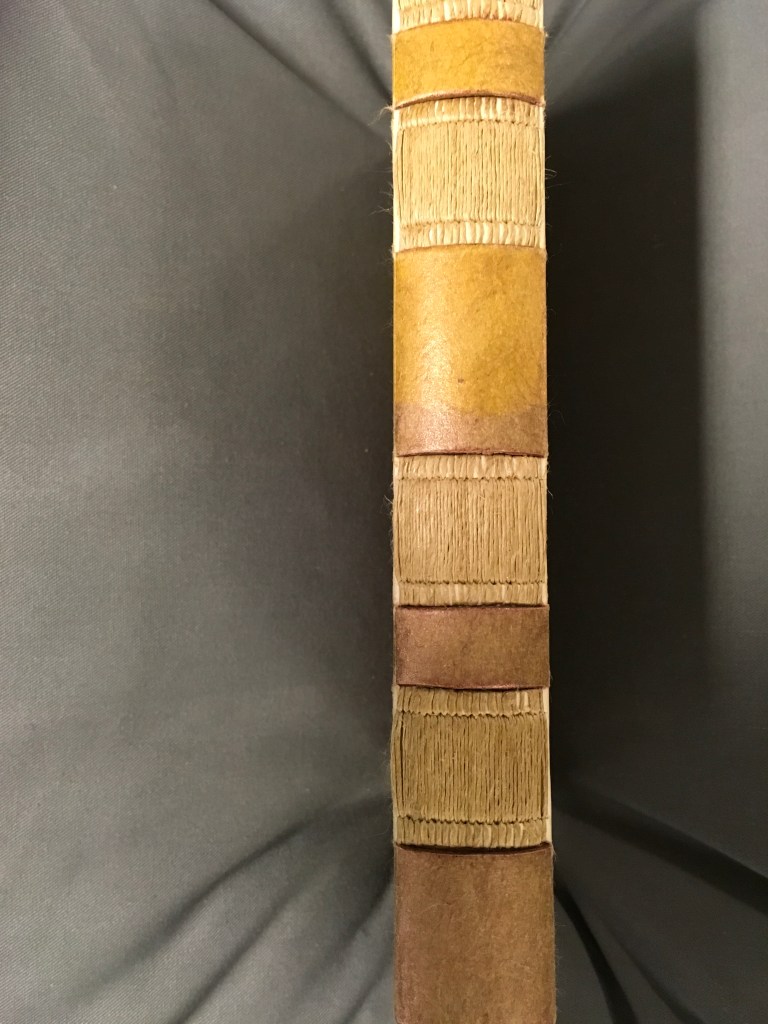

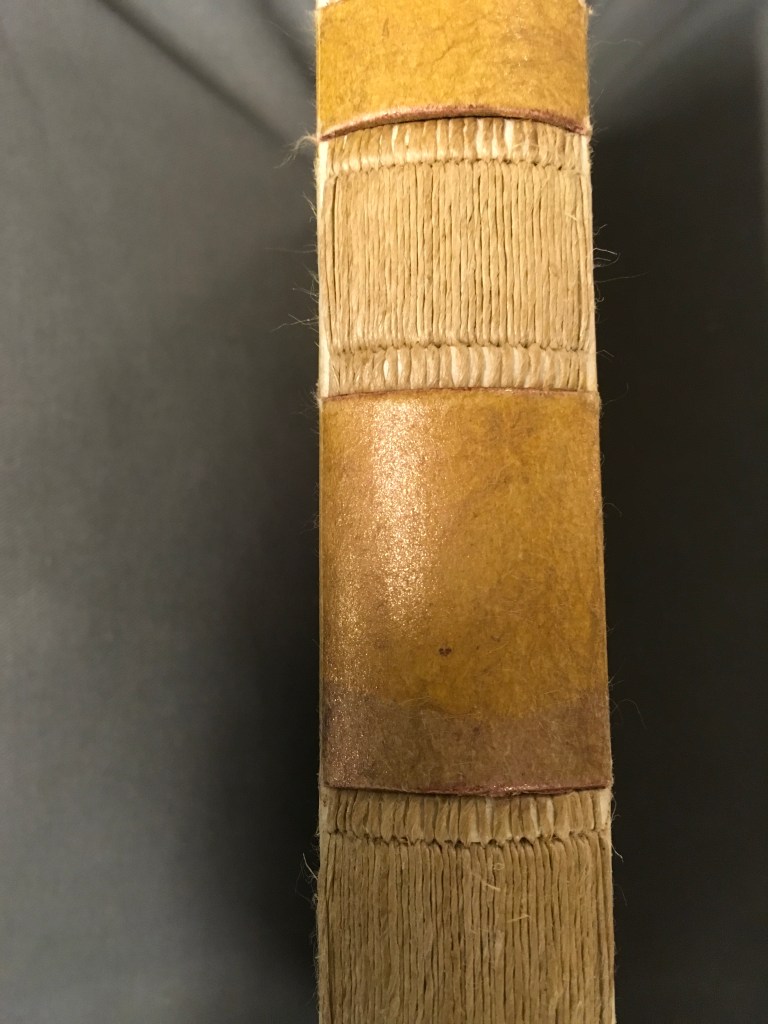

Catalogue casebound, thread-stitching, in printed linen-over-board cover with embossed spine title. H302 x W217 x D25 mm, 256 pages. Acquired from the artists, 21 August 2017. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artists.

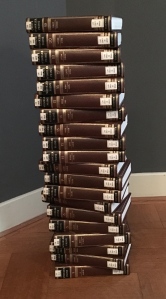

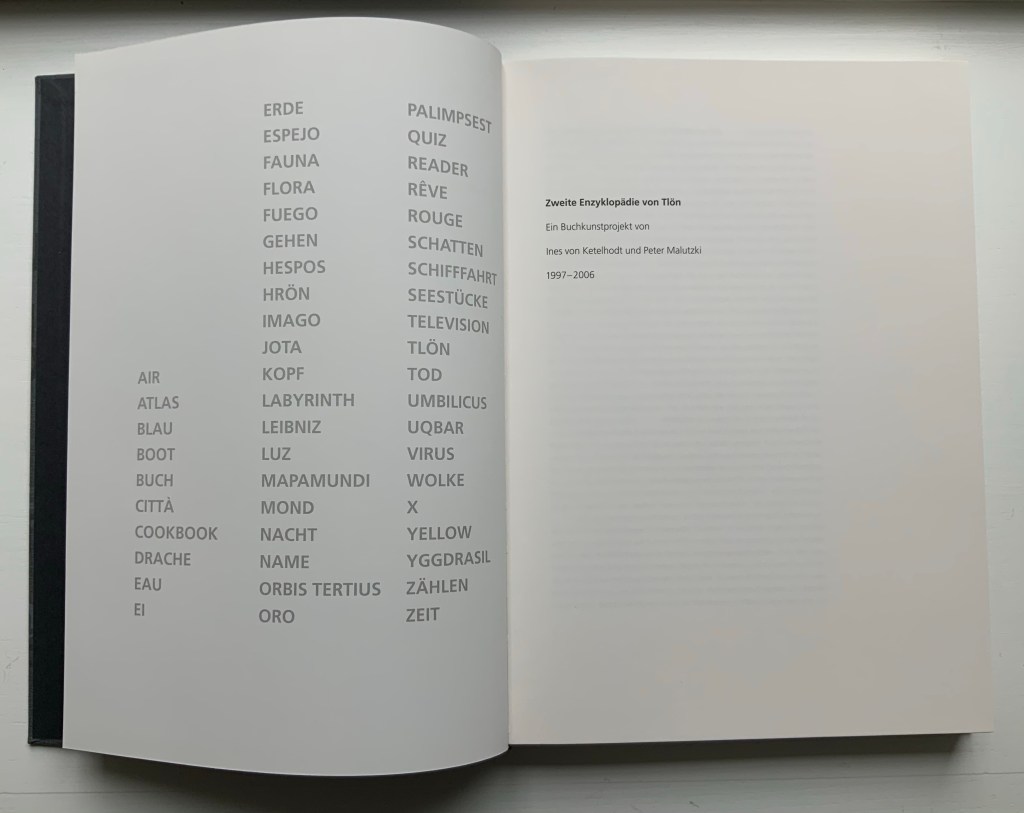

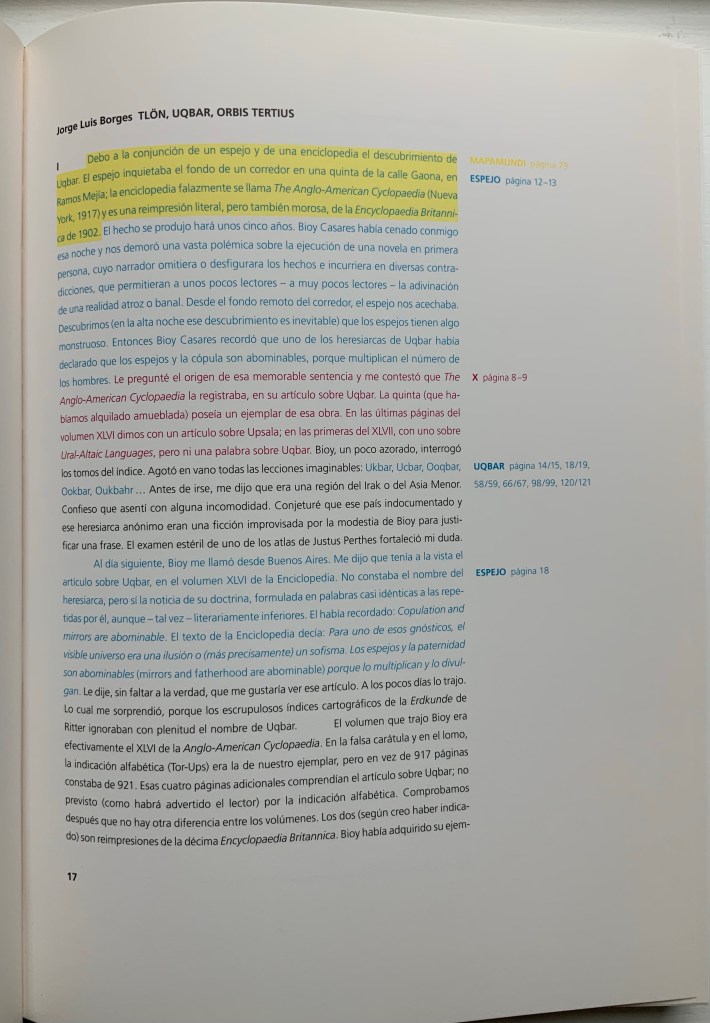

Inspired by Jorge Luis Borges’ epilogue to his short story “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”, von Ketelhodt and Peter Malutzki embarked on their fifty-volume multilingual masterpiece Zweite Enzyklopädie von Tlön (2006), two decades before Alpha Beta (2017). Between 1997 and 2006, the fifty volumes appeared. For the catalogue, they collaborated with twenty-three authors. The site devoted to the project provides a look inside all of the volumes and its companion catalogue. The catalogue alone, however, works well as the tip “of the tip” of the book-berg as von Ketelhodt and Malutzki call it:

Now the fifty volumes lie before us, and we see they are actually only a tiny part of a huge ice-berg that is really a book-berg. Most of it we cannot see because it is below the surface, but we are aware of its existence. We see the project connected to a multitude of other books and are happy that, by the incorporation into public collections, it is now literally close to an enormous number of other books.

The fifty-volume work’s residence in libraries and collections around the world matters to the artists not only financially but conceptually. Only in that setting or frame does the artwork “converse” multilingually with simulacra of the Tlön library. The catalogue includes text in English, French, German and Spanish, and its own system of internal and external cross-referencing is enacted typographically and in color across Spanish, German and English in that order. After all, Borges’ short story was the origin of the work, and it is in Spanish.

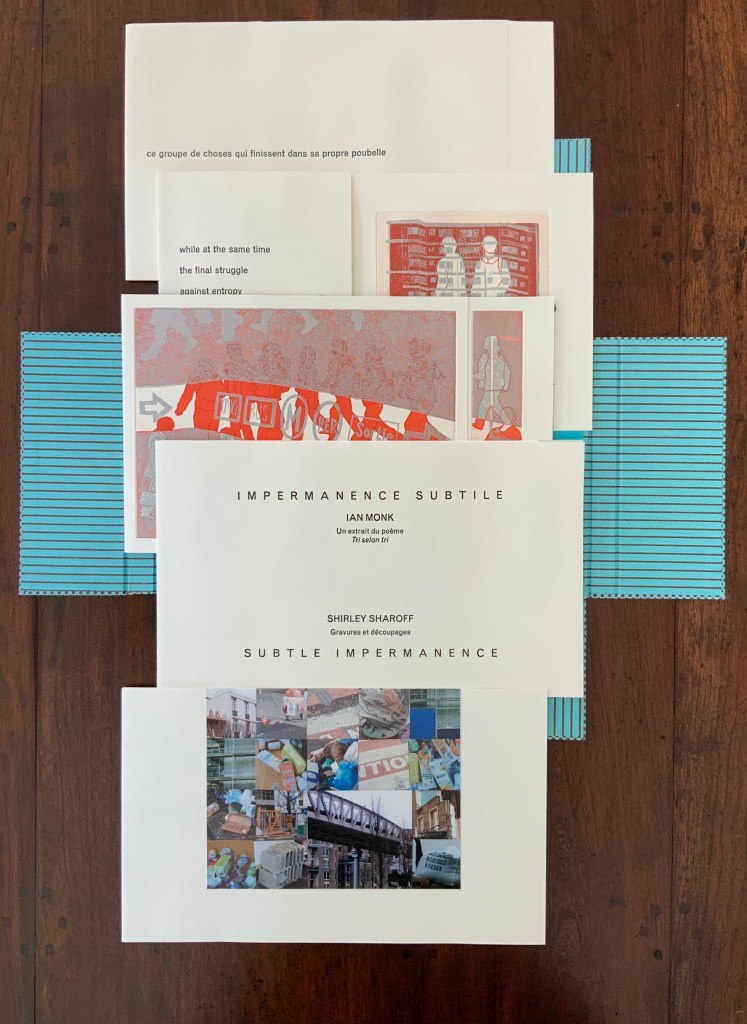

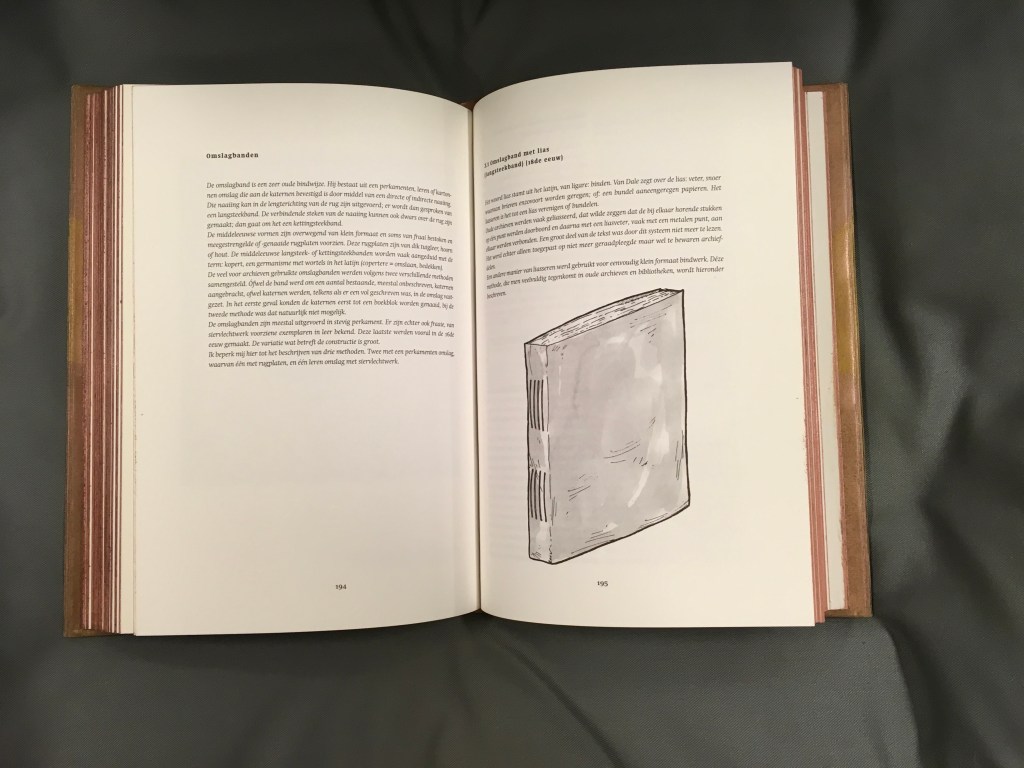

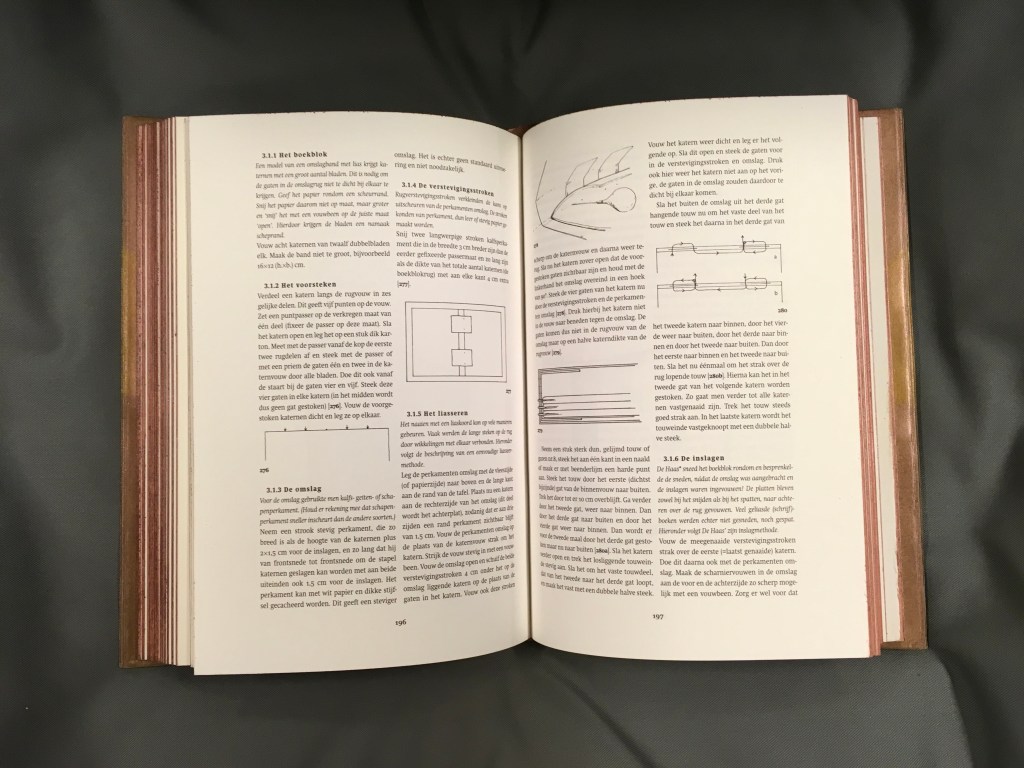

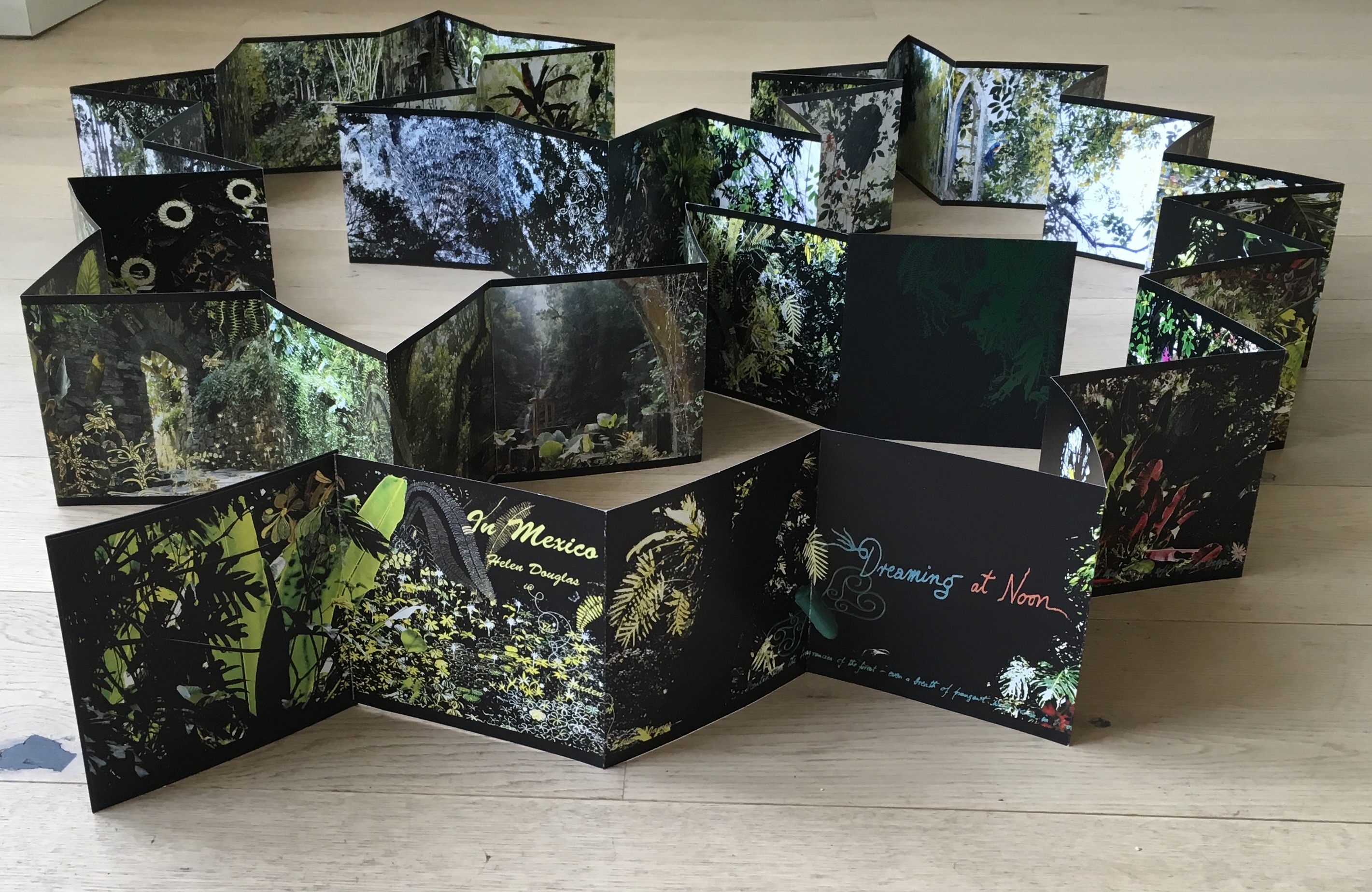

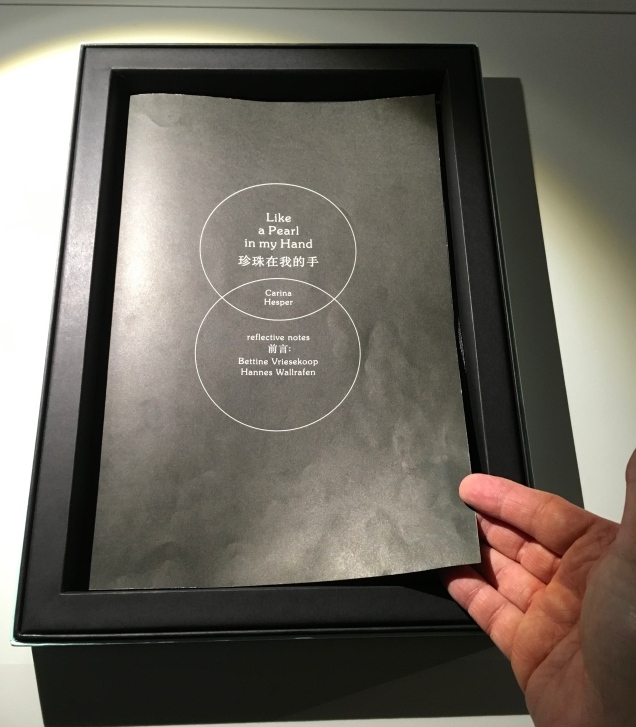

Bücher /// Books (2019)

Bücher /// Books (2019)

Ines von Ketelhodt

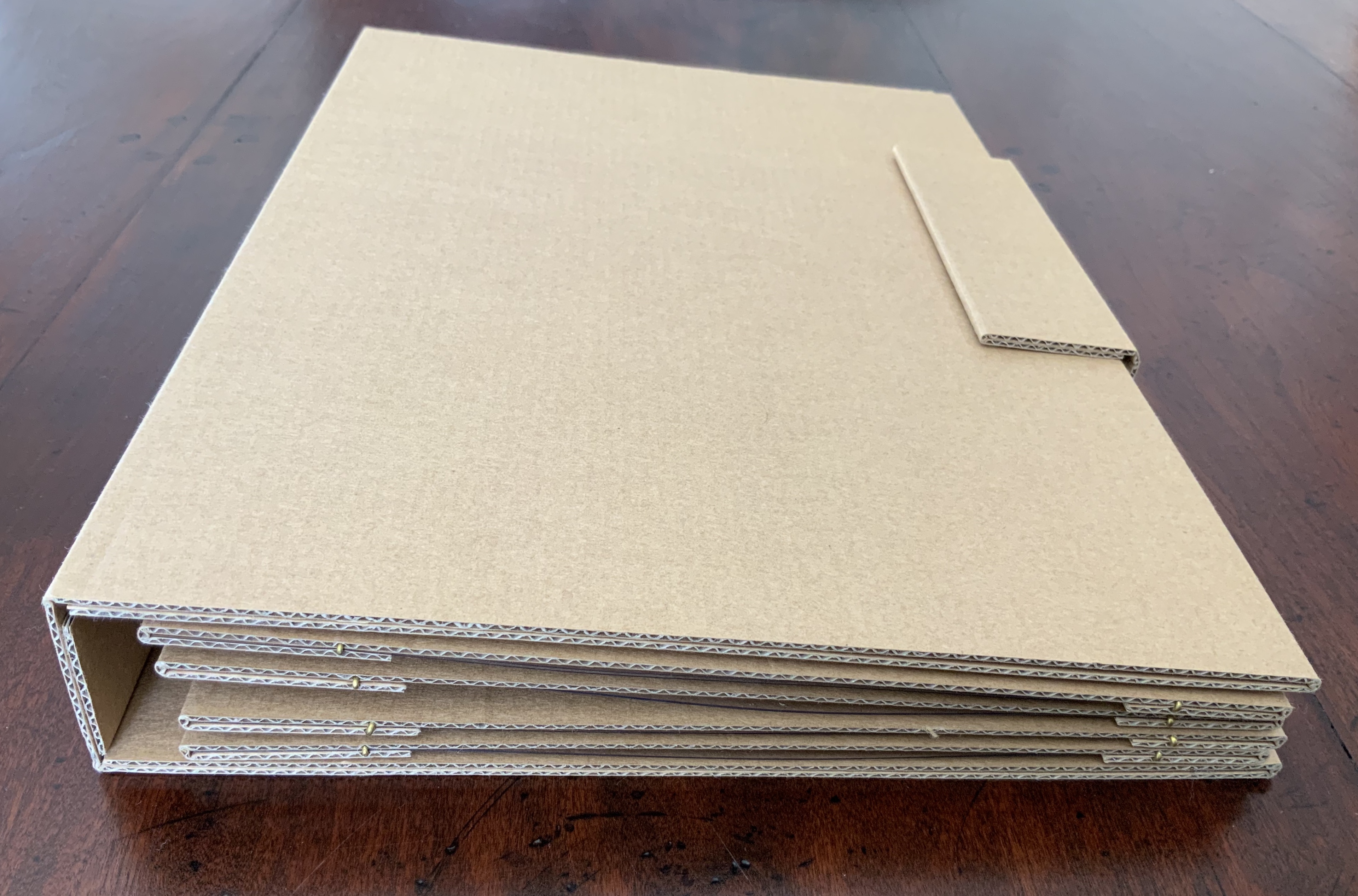

Catalogue for the exhibition at the Klingspor Museum Offenbach, 3 March to 19 May 2019. Card slipcase (H281 x W233 x 21 mm), Perfect bound, photographic-board covered book (H280 x W230 x D19 mm), 192 pages. Acquired from the artist, 22 November 2018. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artist.

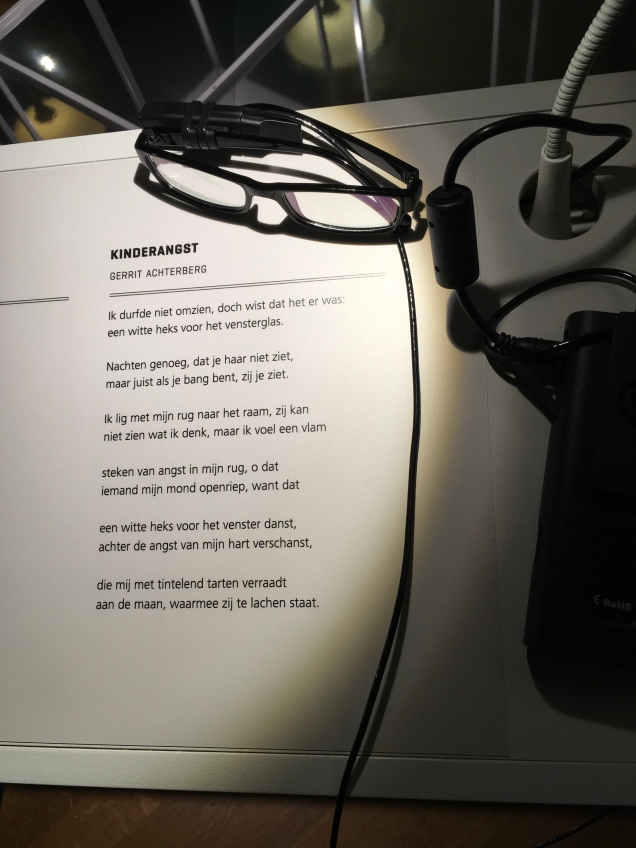

Catalogue entry for Alpha Beta. Photo: Books On Books Collection, displayed with artist’s permission.

Catalogue entry for Zweite Enzyklopädie von Tlön. Photo: Books On Books Collection, displayed with artist’s permission.

Catalogue entry for Times Square 1-2-3. Photo: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artist.

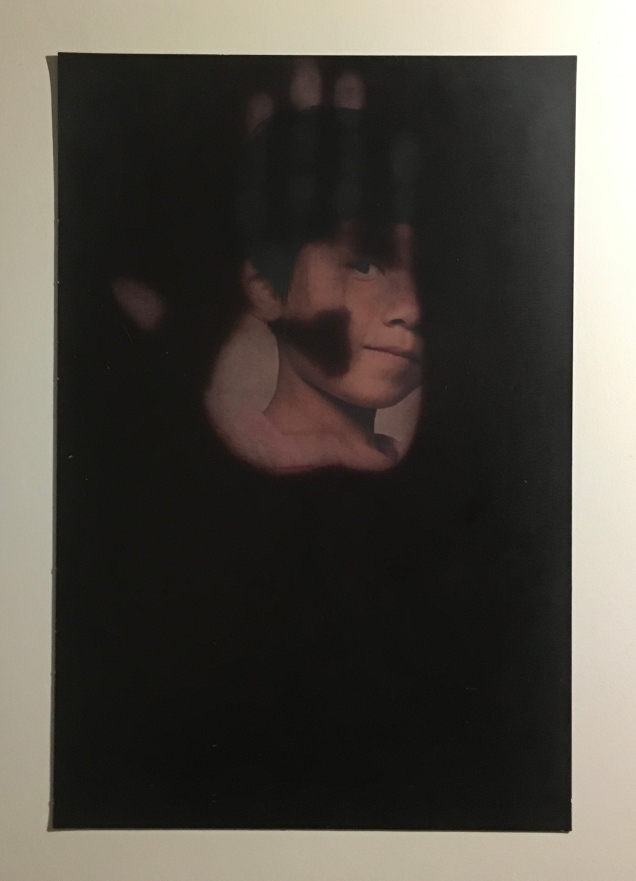

Photo: Books On Books Collection, displayed with artist’s permission.

Alpha Beta is von Ketelhodt’s primary solo work in the collection. As such, it does not reflect her extraordinary talent with photos (B/W and color) in making book art. The description above of Times Square 1-2-3, its representation in this catalogue of her work, and the catalogue’s cover have to suffice as place holders for now.

Further Reading

Princeton University holds Alpha Beta in its Graphic Arts Collection and provides two (unattributed) English translations of the extract. Accessed 18 August 2020. Here is one of them:

Arranged like bottles on their shelves, the volumes age in the large cellar, soft lamps hovering over creased or ringleted foreheads lowered in their attempts to decipher the comments. Here are the dictionaries, the espaliers of languages; in that aisle over there, the crystalline sonnets and haikus, the gemlike ballads. Opening a grating, you find yourself in a lofty reading room with a glass ceiling that reflects back the drowsiness, the leafing, the ecstasies. Like a climbing plant, the long sentence twines around the railing that runs along the galleries of the Romans-fleuves [sic; means “saga novels”] with their barges full of families, inheritances, conflicts, collapses, wearinesses and kisses. A bit farther on: the natural history shelves with their plant posters and flora; the birds that fly upward when you turn the pages and circle around the iron columns, touch their skulls [sic; “bump their heads”?] and then return to their leather and linen aviaries to sleep; the beasts of prey roaring and the fish gliding by the aquarium windows.

“Lizzie Brewer“. 4 July 2023. Books On Books Collection. For another homage to Borges.

“Peter Malutzki“, Books On Books Collection, 11 November 2019.

“Aurélie Noury“. 9 November 2020. Books On Books Collection. For another homage to Borges.

“Hanna Piotrowska (Dyrcz)“. 13 December 2019. Books On Books Collection. For another homage to Borges.

“Benjamin Shaykin“. 3 December 2022. Books On Books Collection. For another homage to Borges.

“Rachel Smith“. In progress. Books On Books Collection. For another homage to Borges.

Basile, Jonathan. 2015~. The Library of Babel. Website. Accessed 3 July 2023.

Butor, Michel, and Helmut Scheffel, trans. 1986. Fenster auf die Innere Passage = Fenêtres sur le Passage intérieur. Frankfurt a.M: Edition Qumran im Campus-Verlag.

Oppen, Monica. “Masterpiece: Zweite Enzyklopädie von Tlön”. Imprint: Journal of the Print Council of Australia. Volume 49, Number 4. Fitzroy 2014.

Van Capelleveen, Paul, and Jos Uljee, Clemens de Wolf, Huug Schipper, and Diane E. Butterman-Dorey. 2016. Artists & others: The Imaginative French Book in the 21th century: Koopman Collection, National Library of the Netherlands. Pp. 114-15.