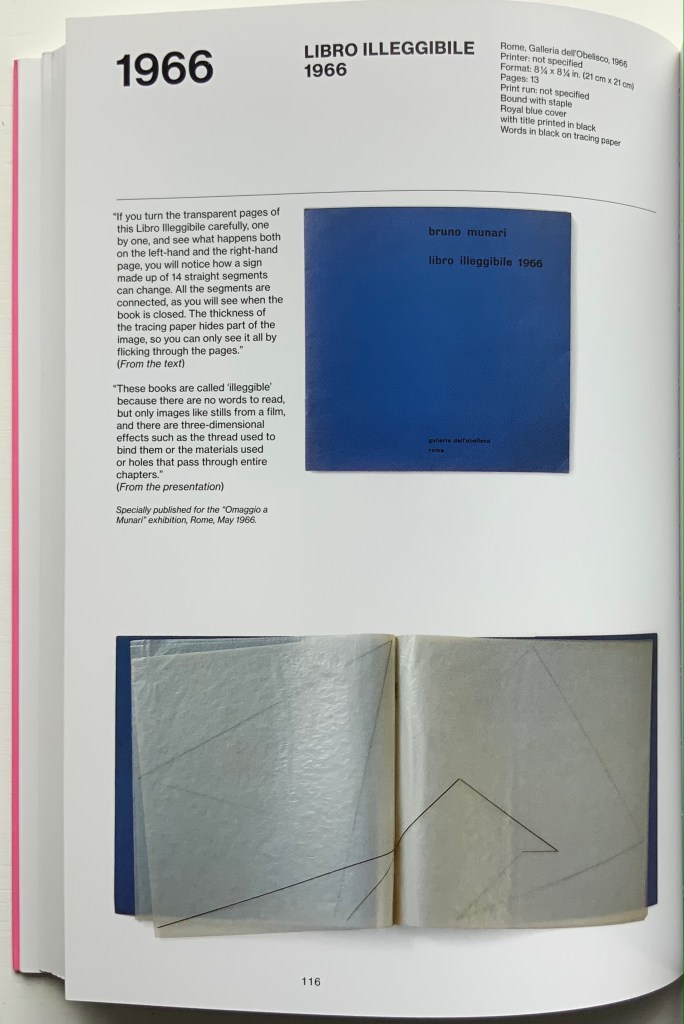

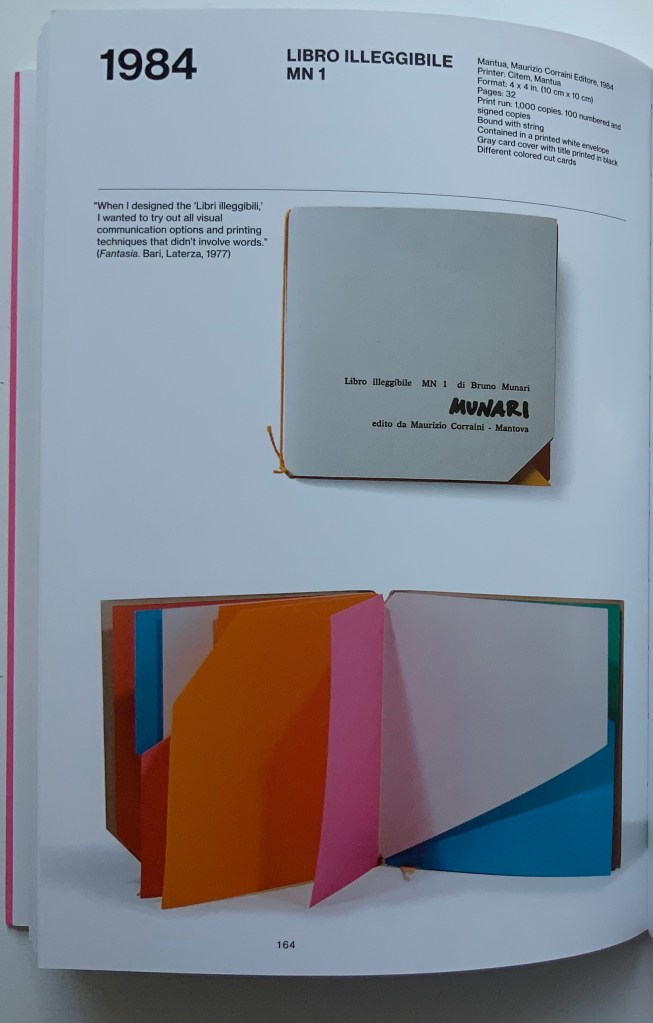

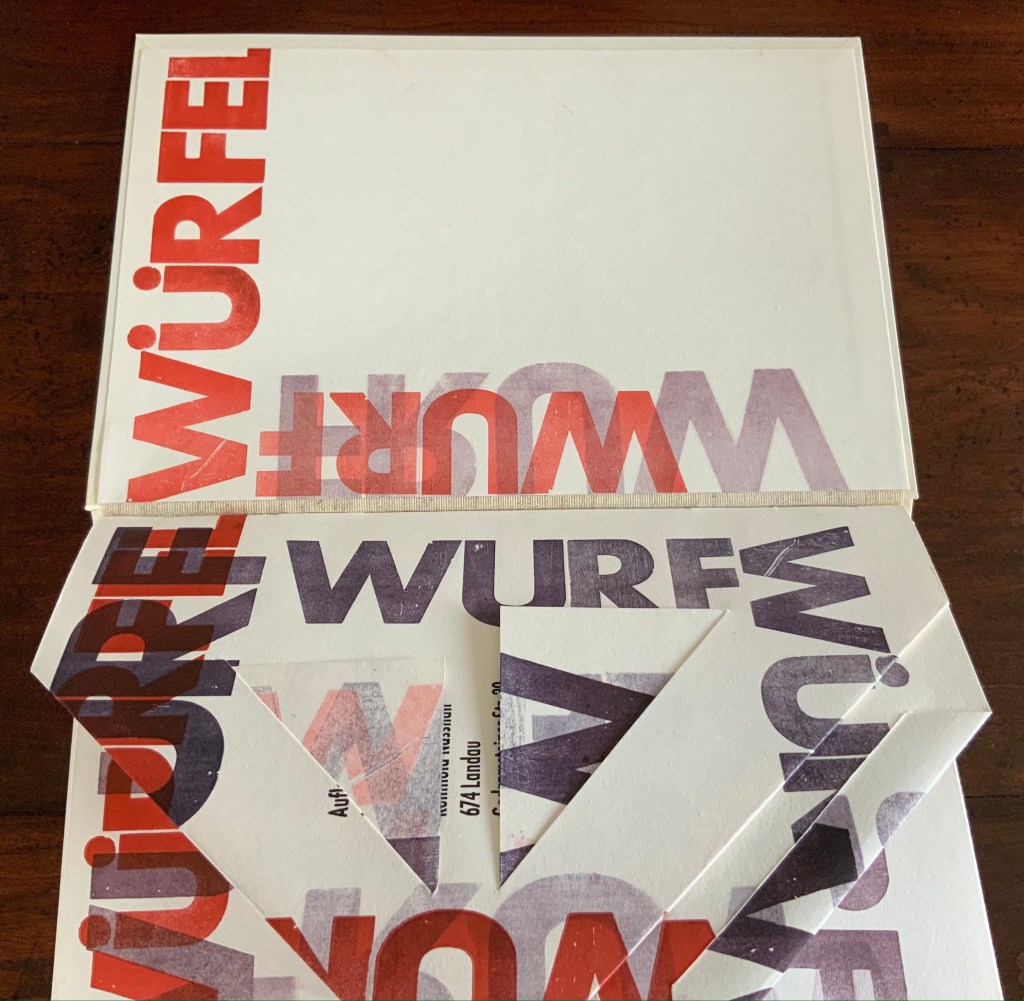

Würfelwurf (1992)

Würfelwurf: fragmentarische Annäherung an Stéphan Mallarmé (1992)

Reinhold Nasshan

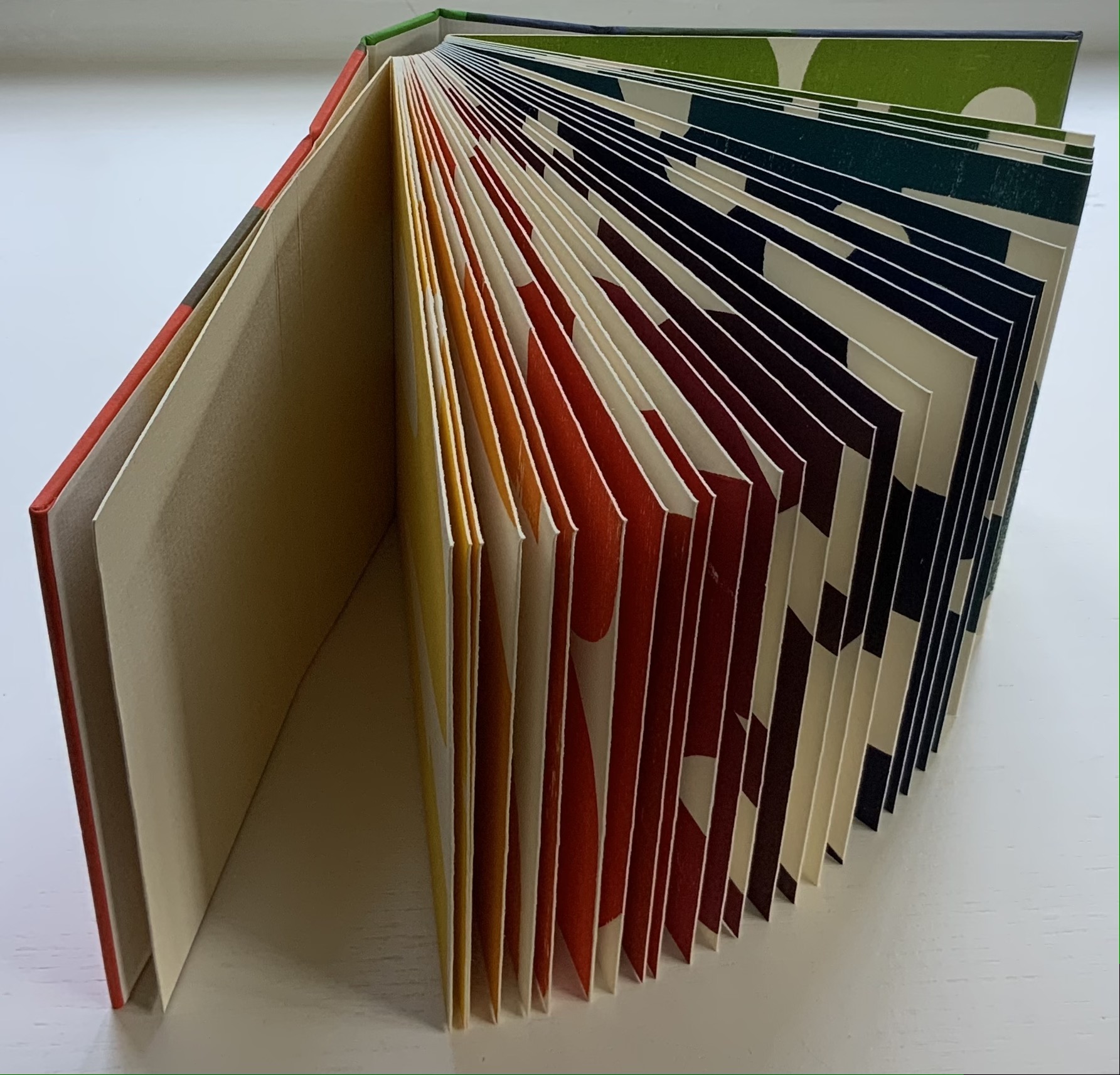

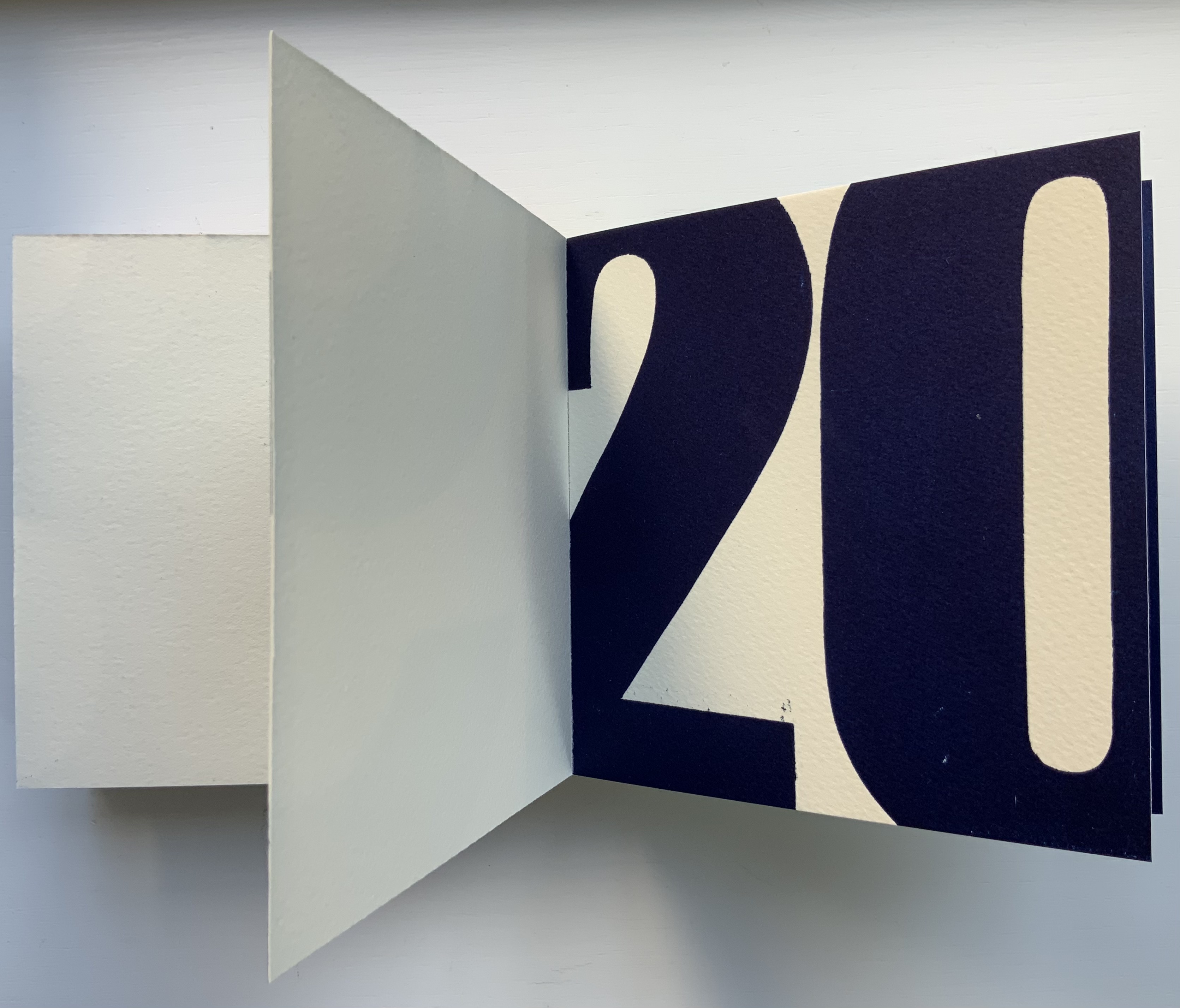

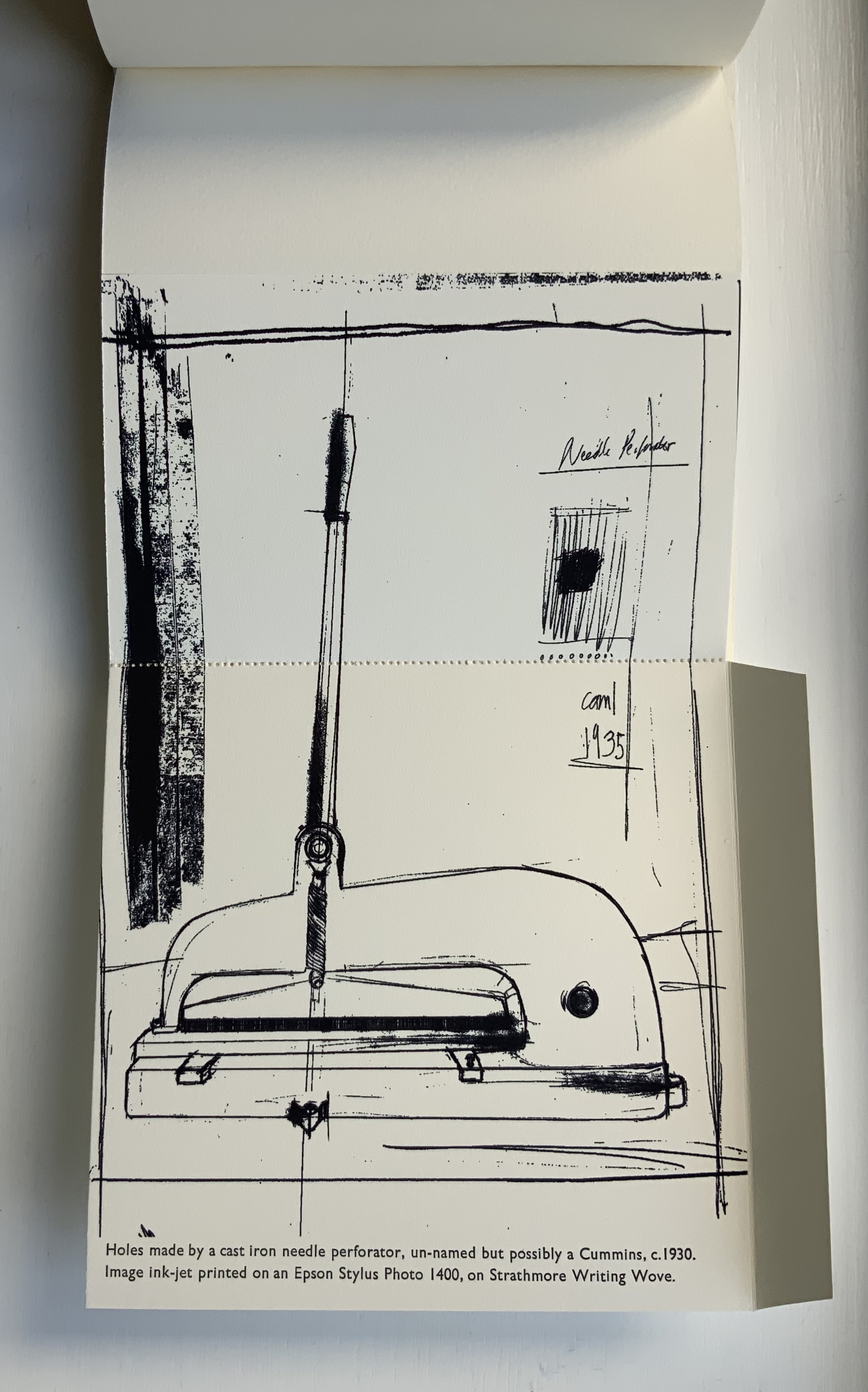

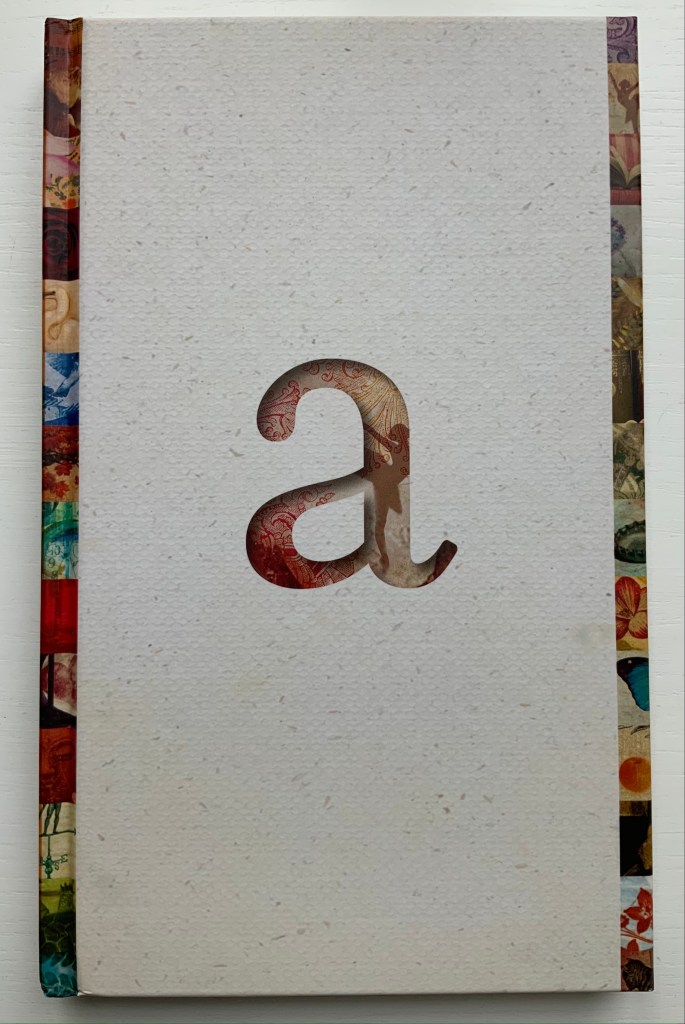

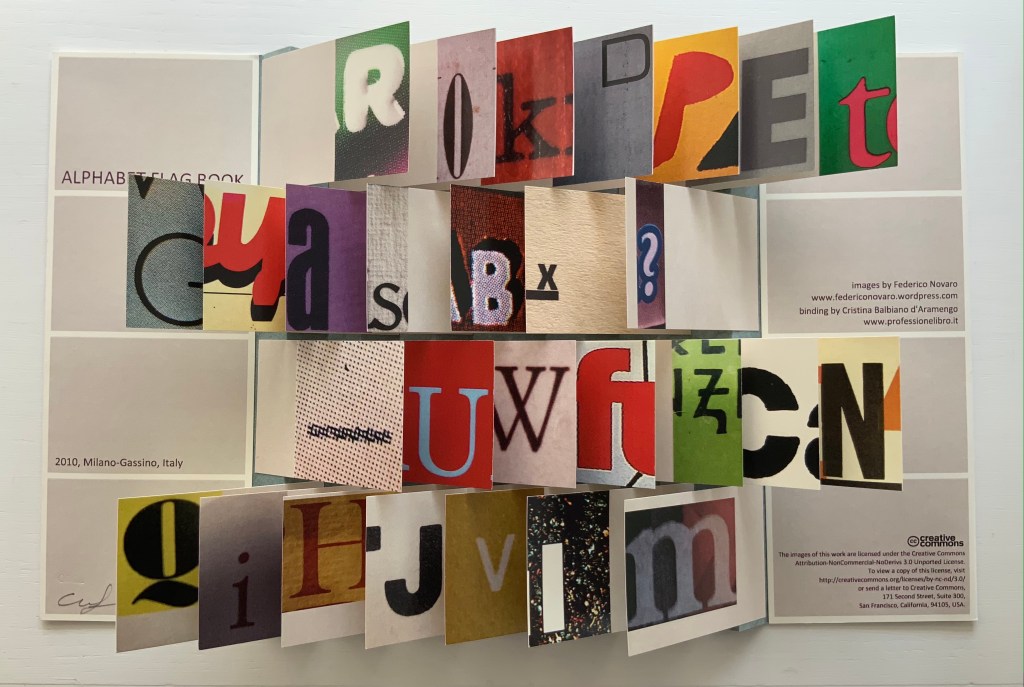

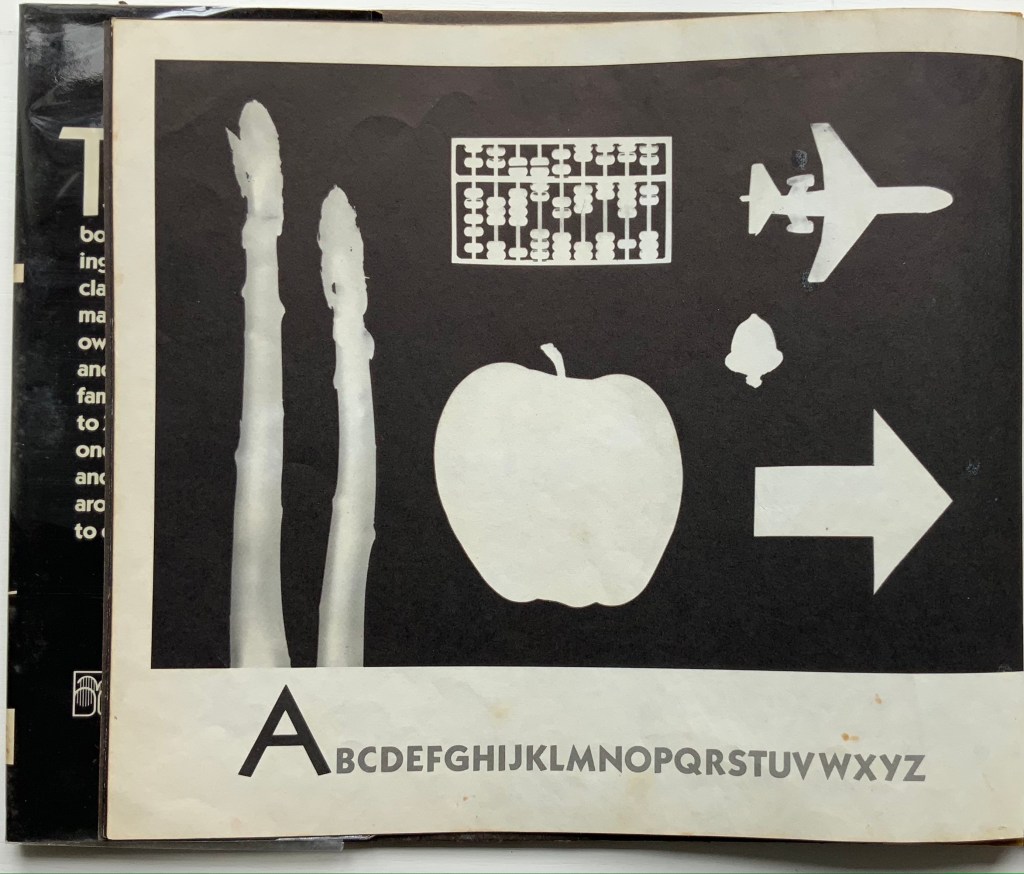

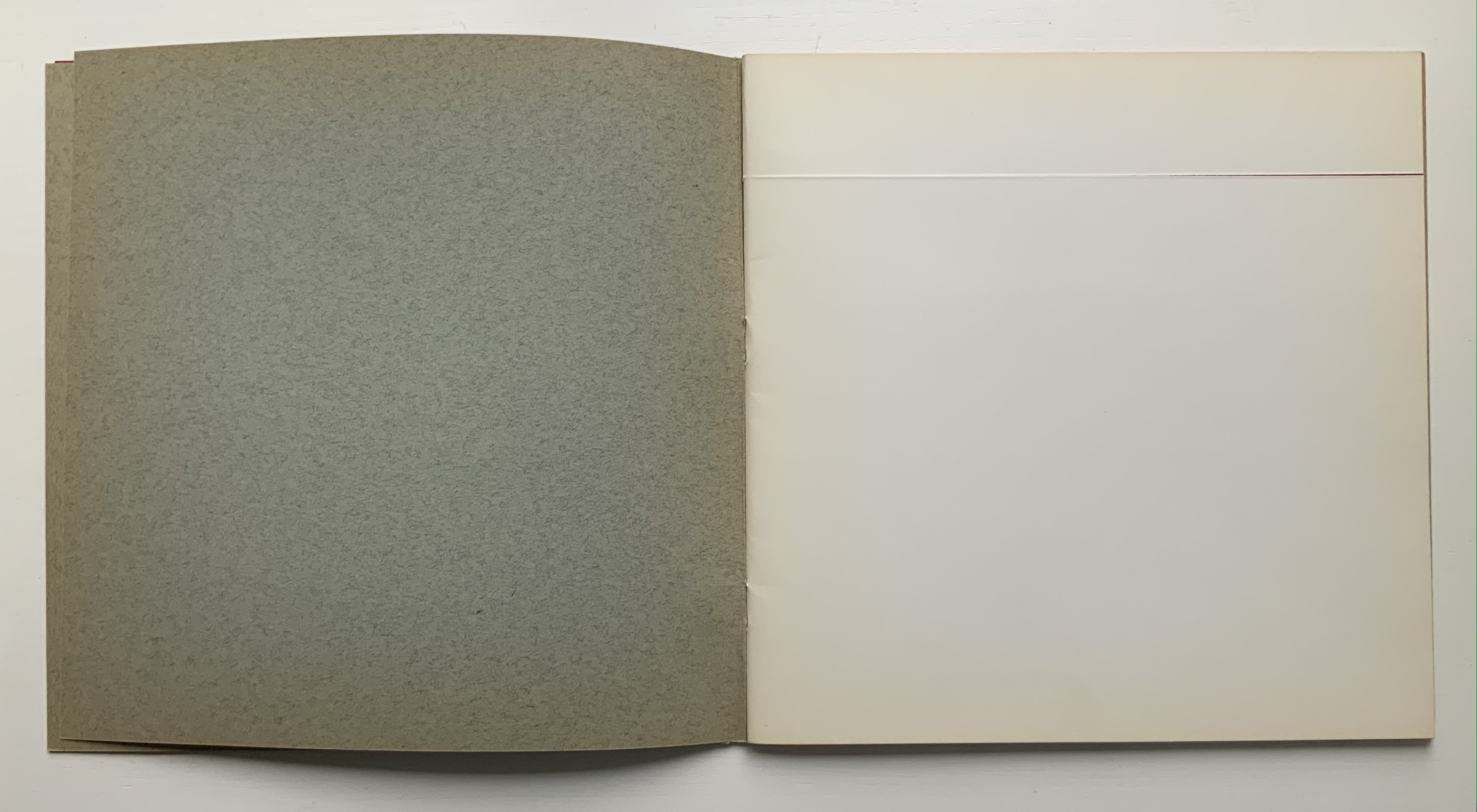

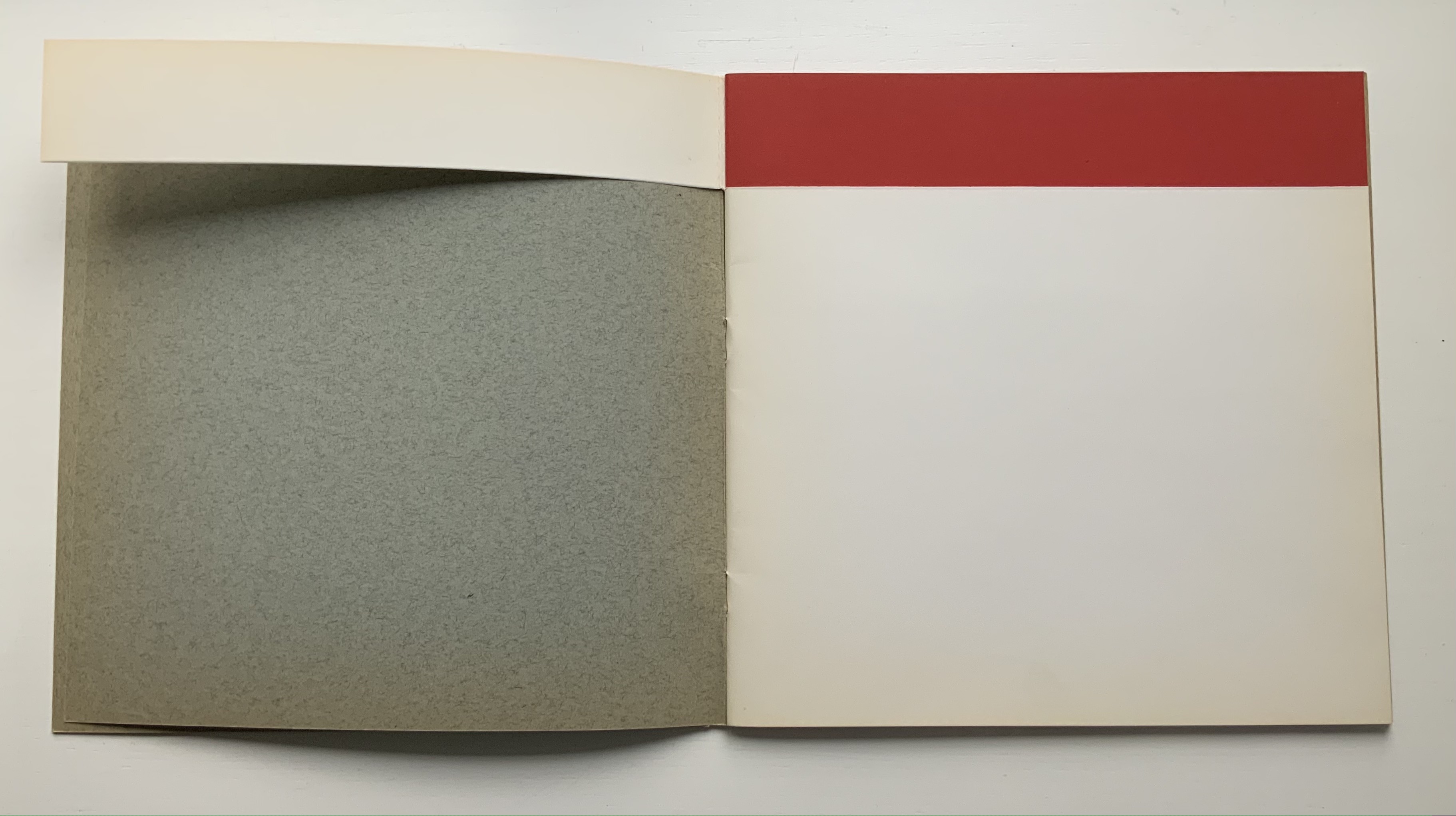

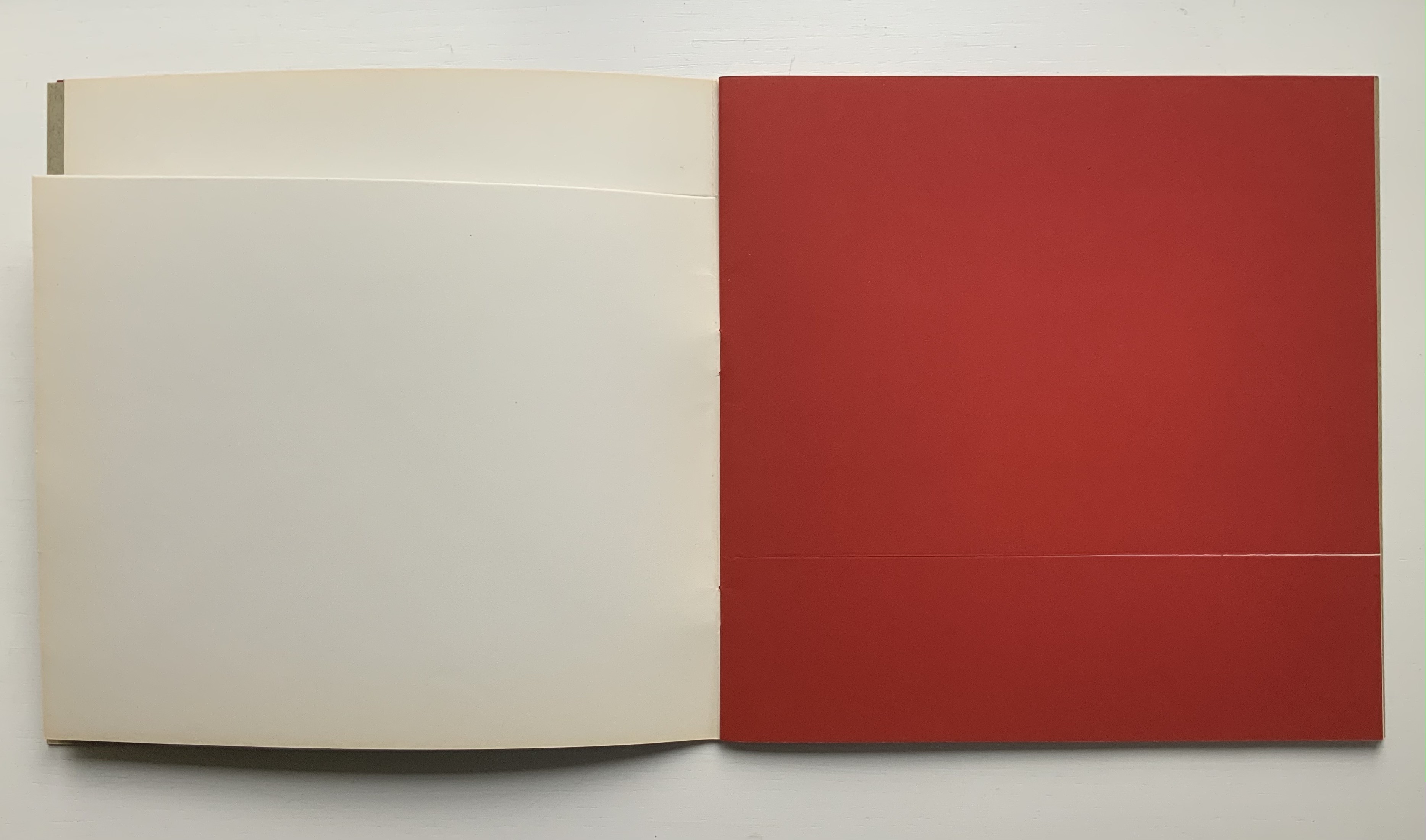

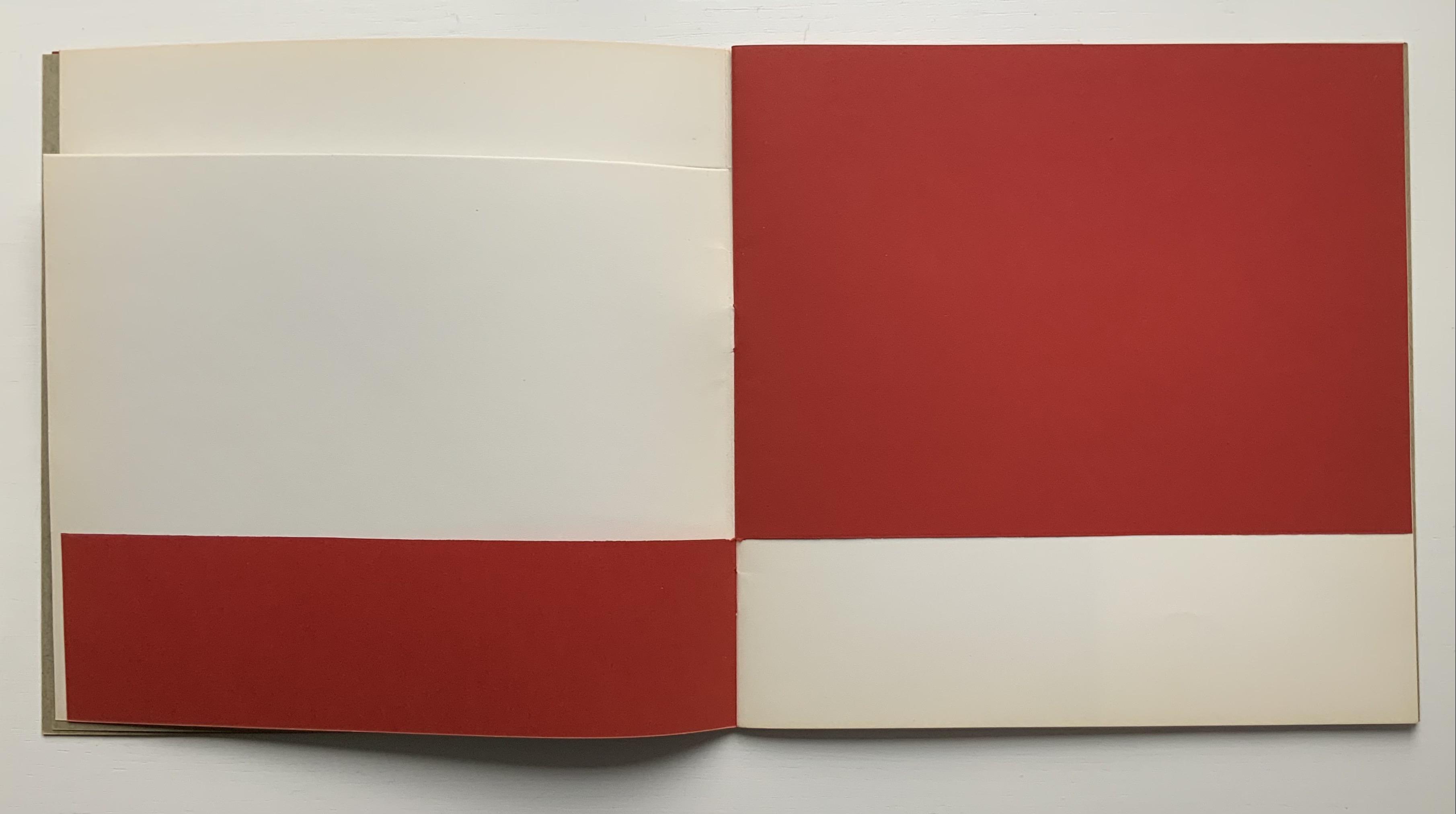

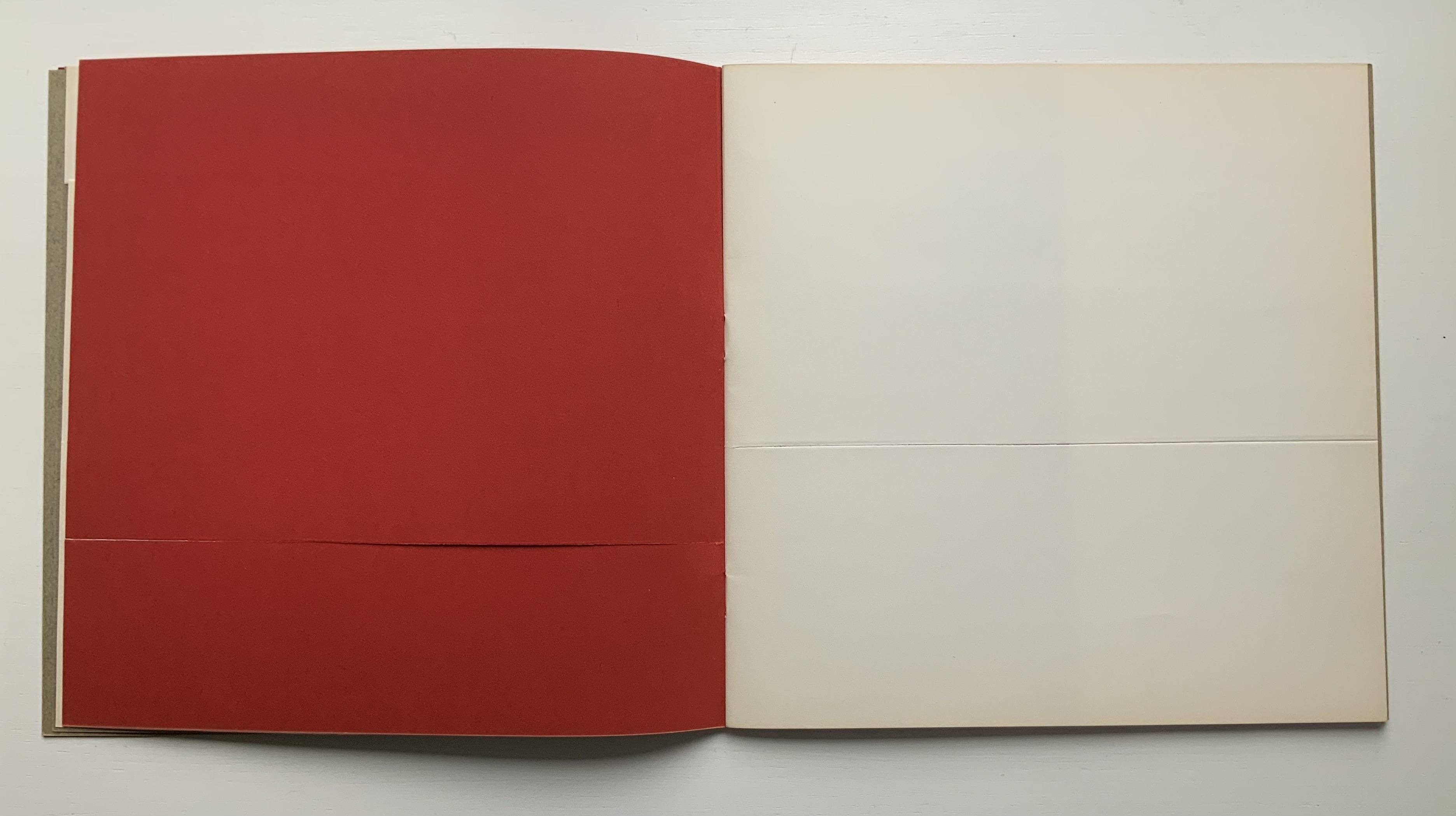

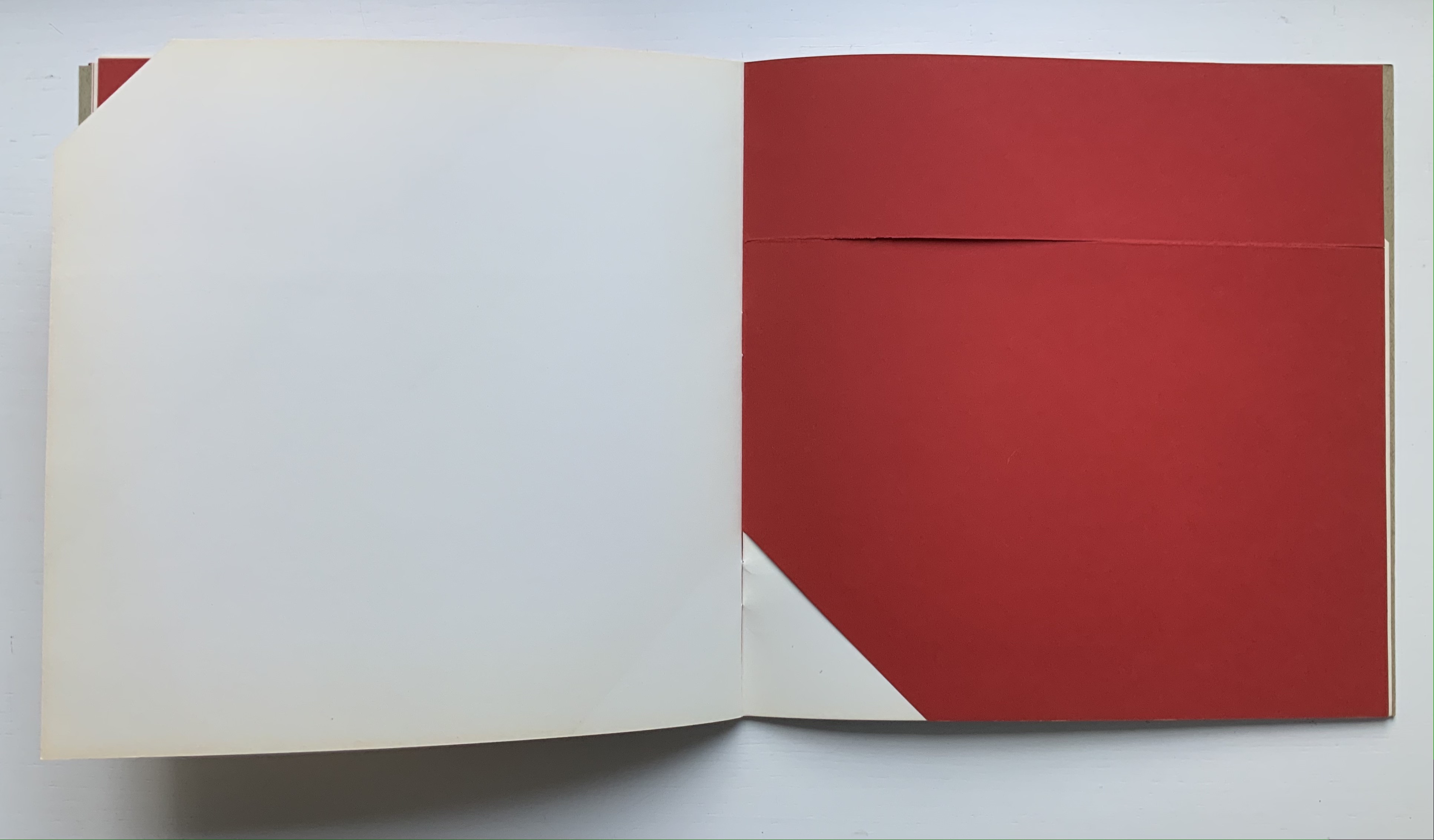

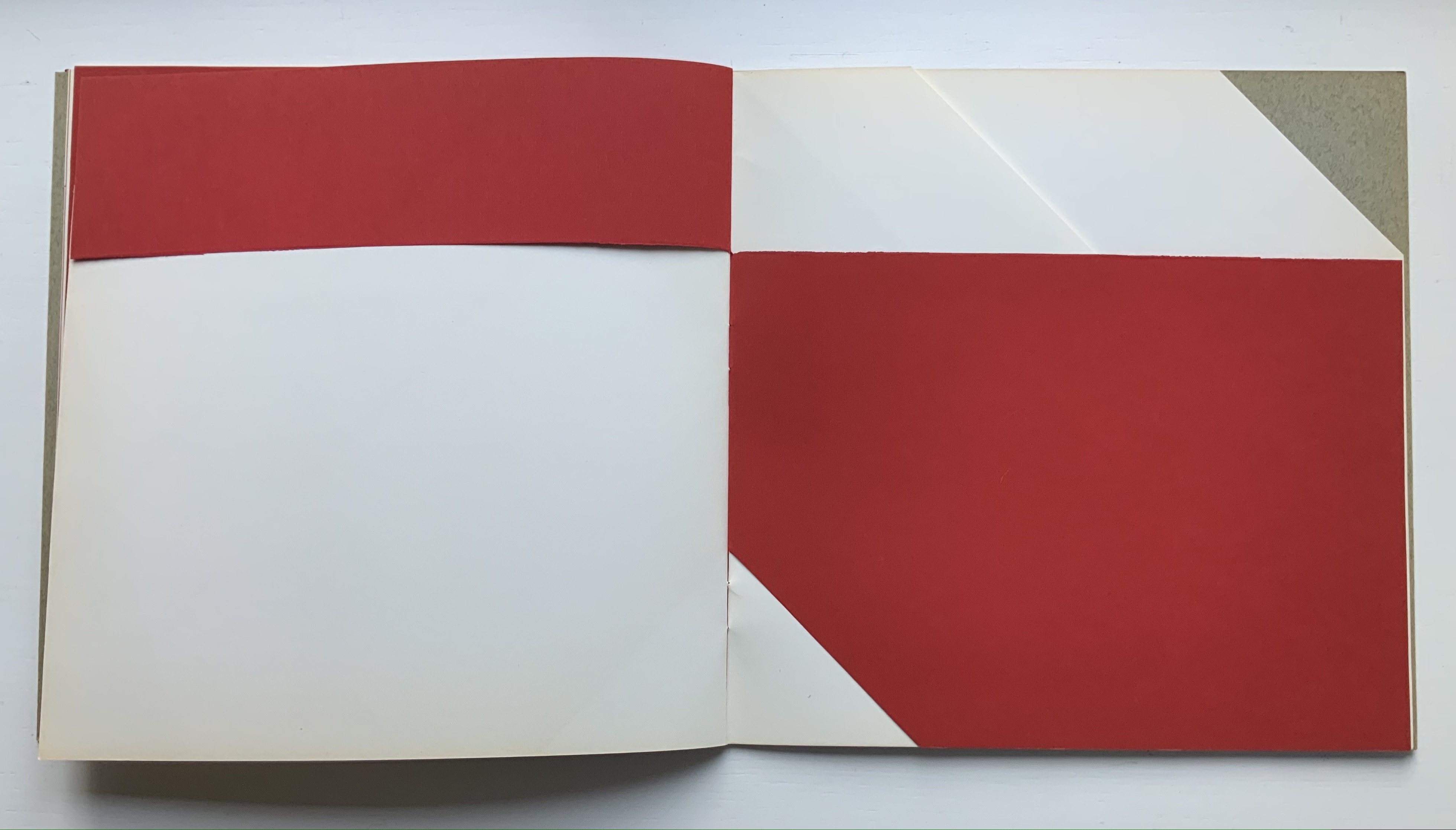

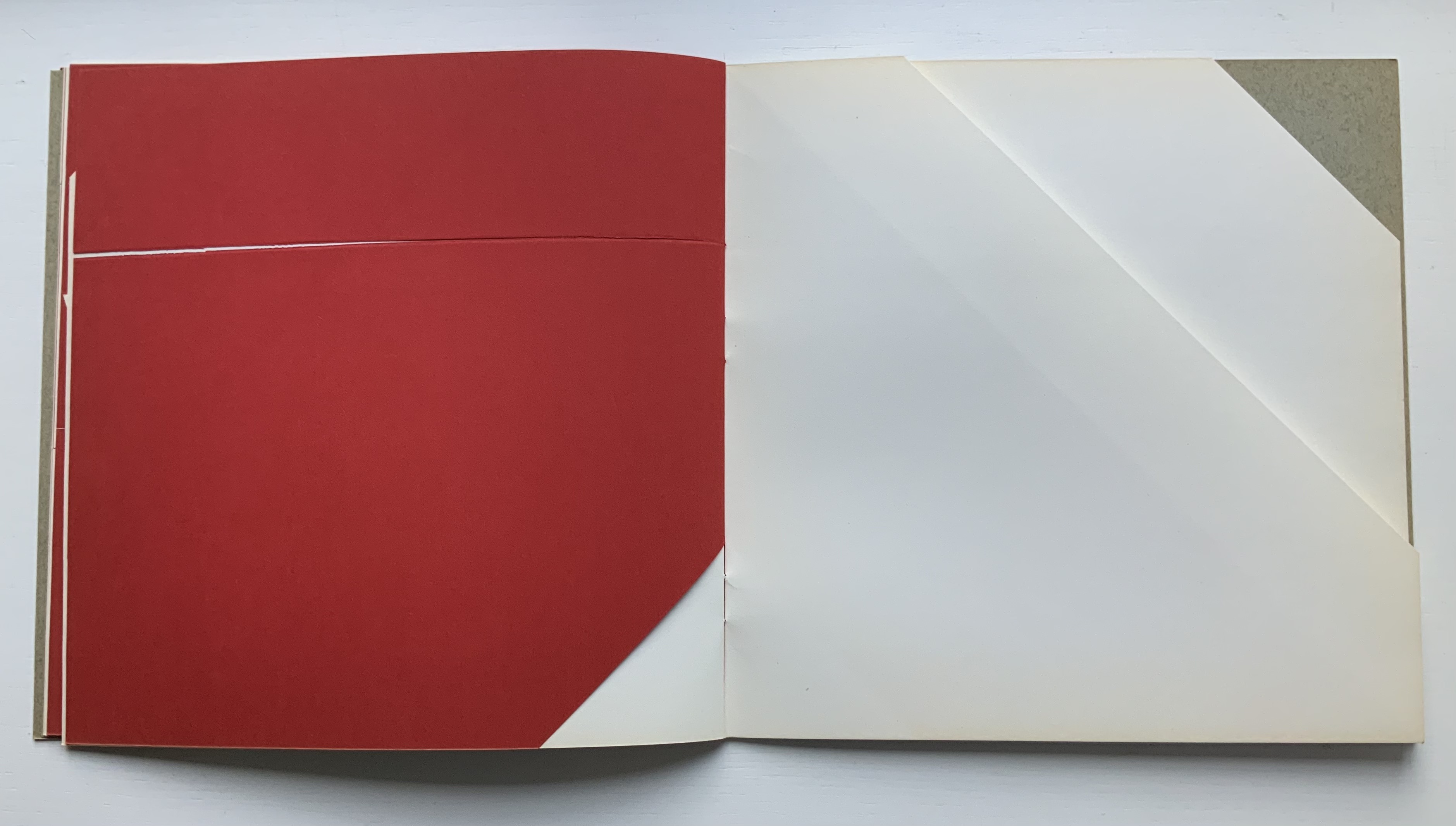

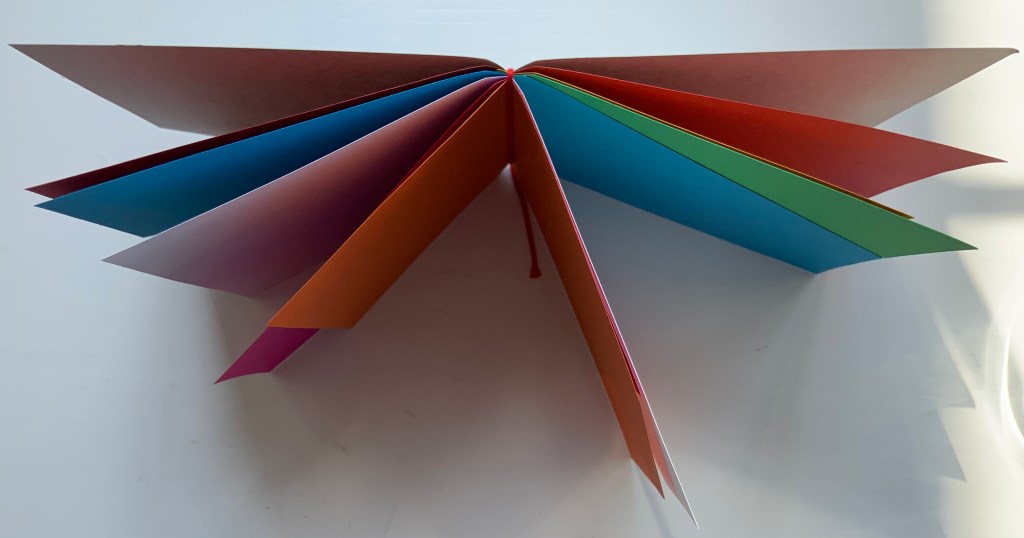

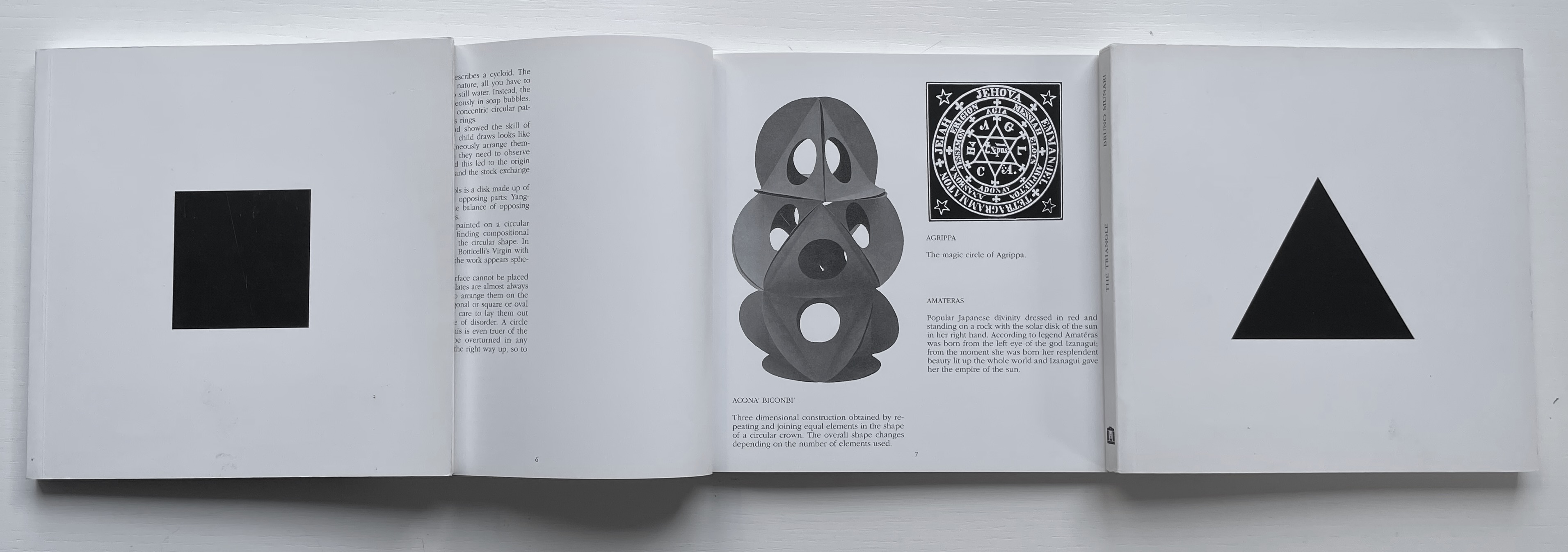

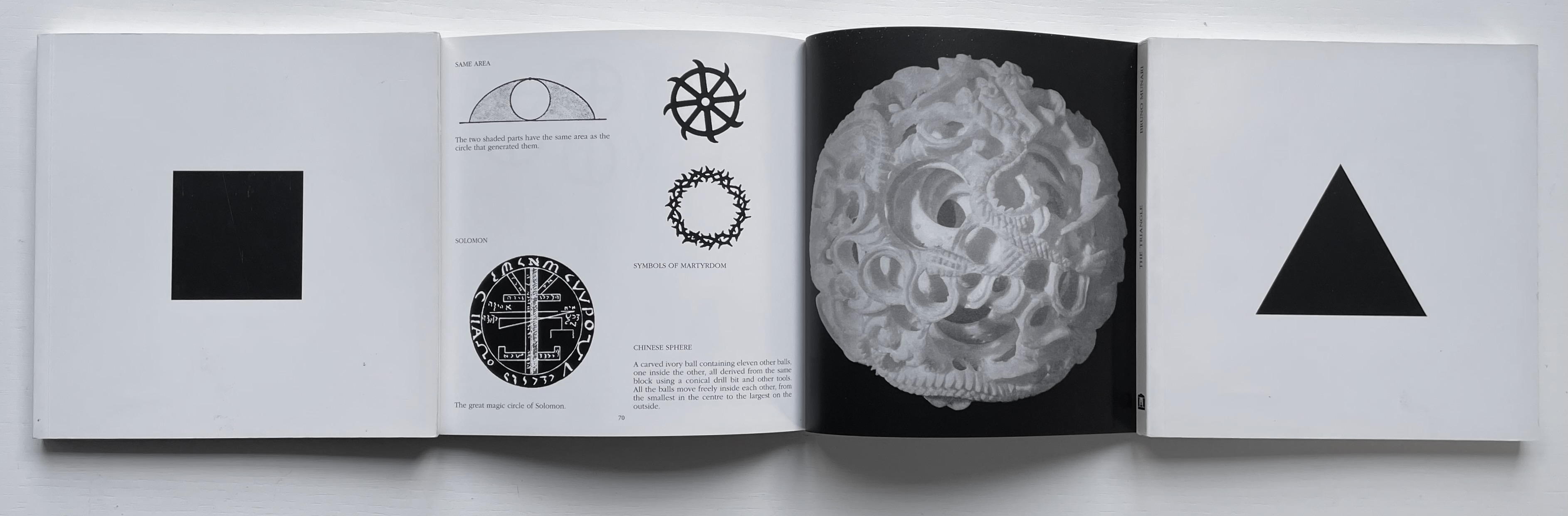

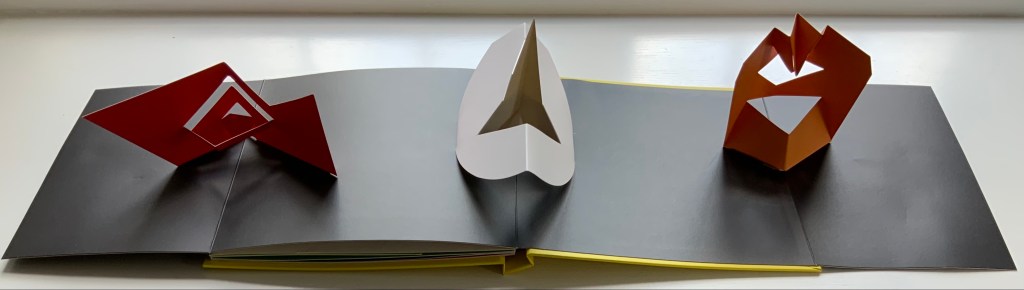

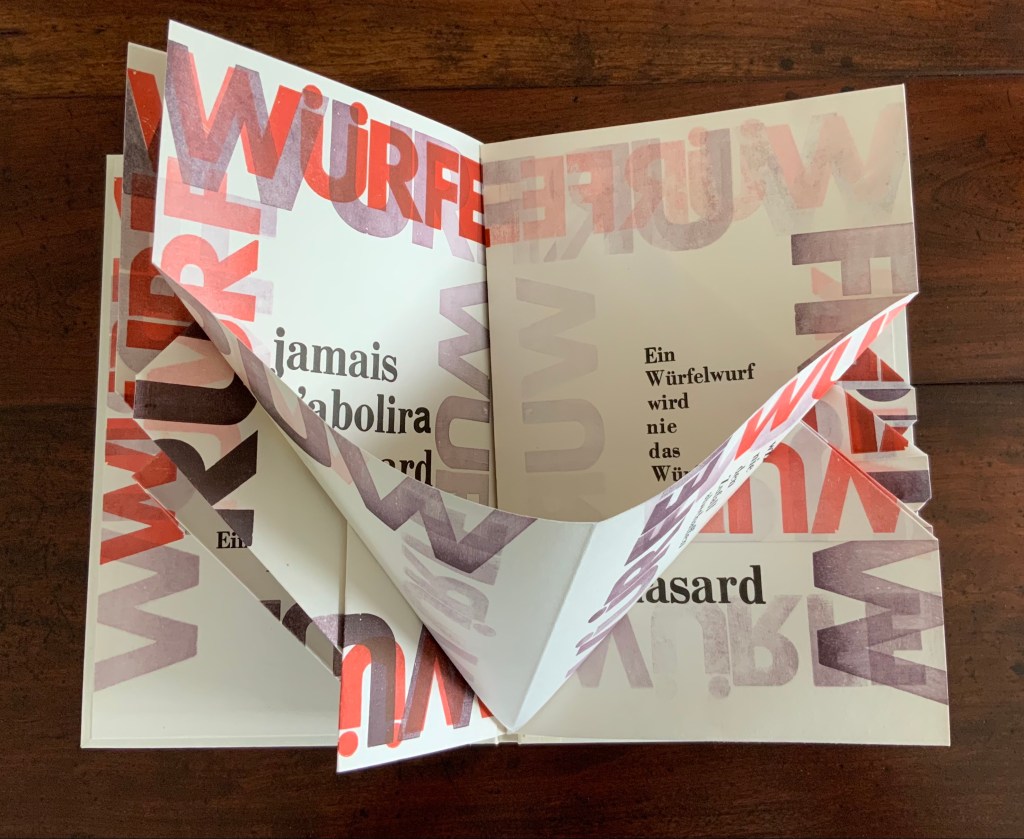

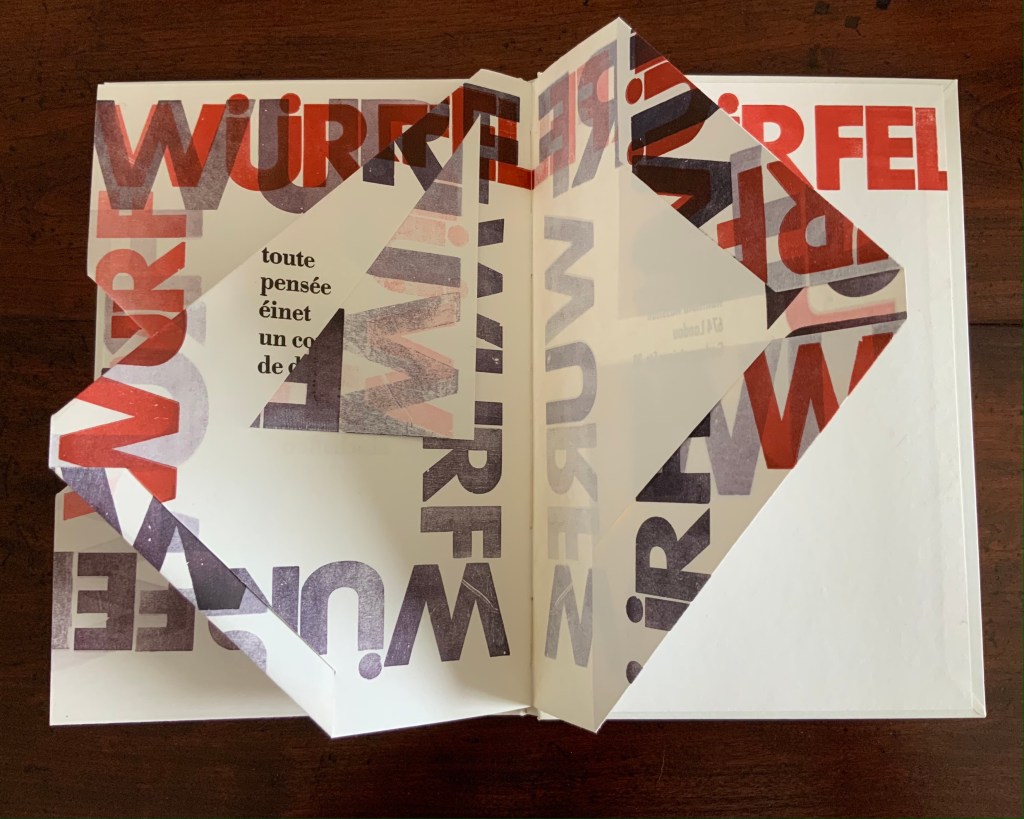

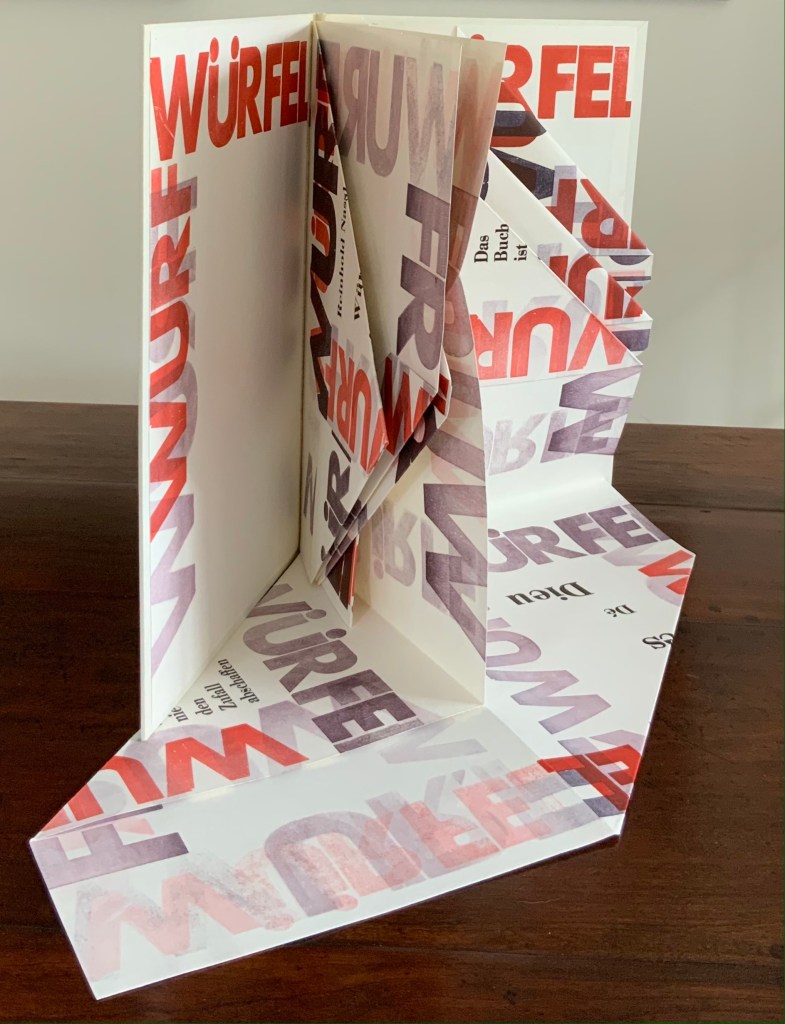

Slipcase, embossed spine, casebound in paper-covered boards, front cover decorated with title set on slip of paper woven into the cover, block sewn and glued, with relief prints as pastedowns. Slipcase: H360 x W248 mm; Book: 351 x 243 mm, 4 gatherings of folios of varying size cut, tucked or folded to fit within the binding’s dimensions. Unique. Acquired from the artist, 24 February 2021.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artist’s permission.

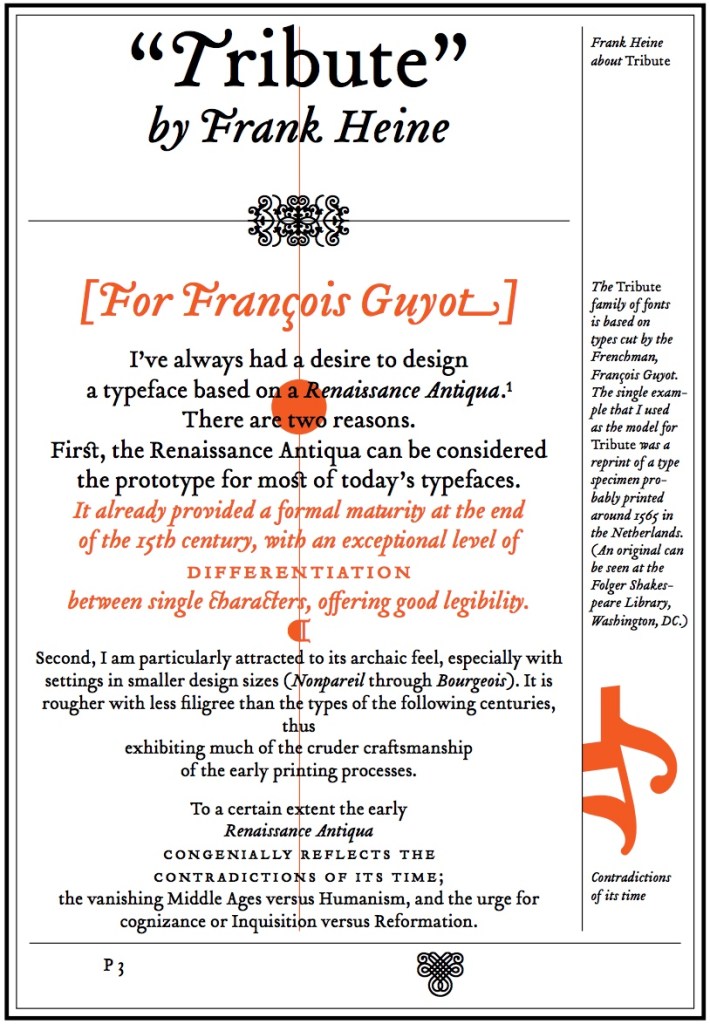

“Throw of the dice”, “dice throw” or “throwing dice” are all reasonable translations of Würfelwurf, but not “a throw of the dice”, which most German translators render as ein Würfelwurf when tackling Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés. But then Reinhold Nasshan is not translating the poem. As the subtitle indicates, he is making “a fragmentary approach”, an approximation.

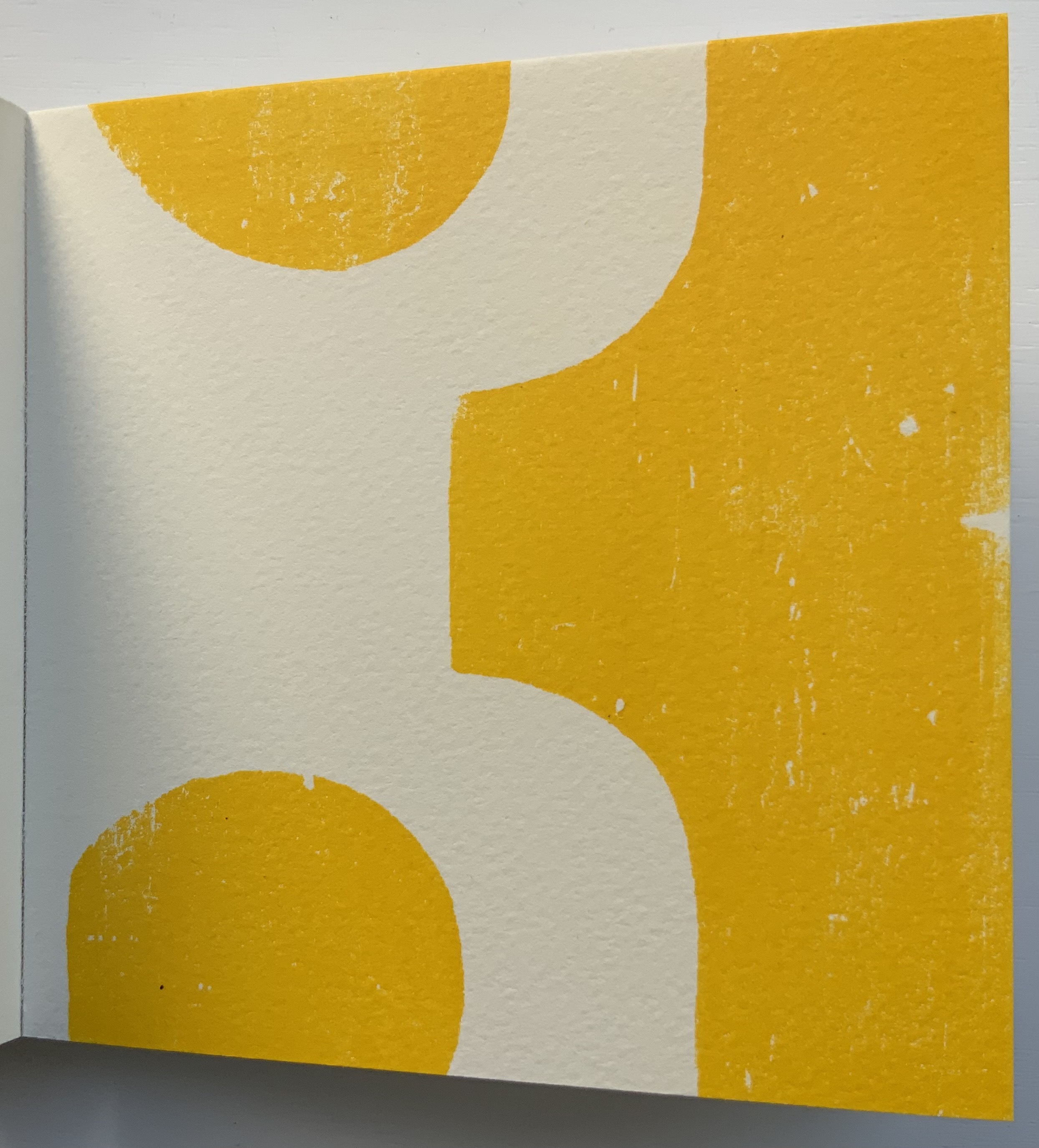

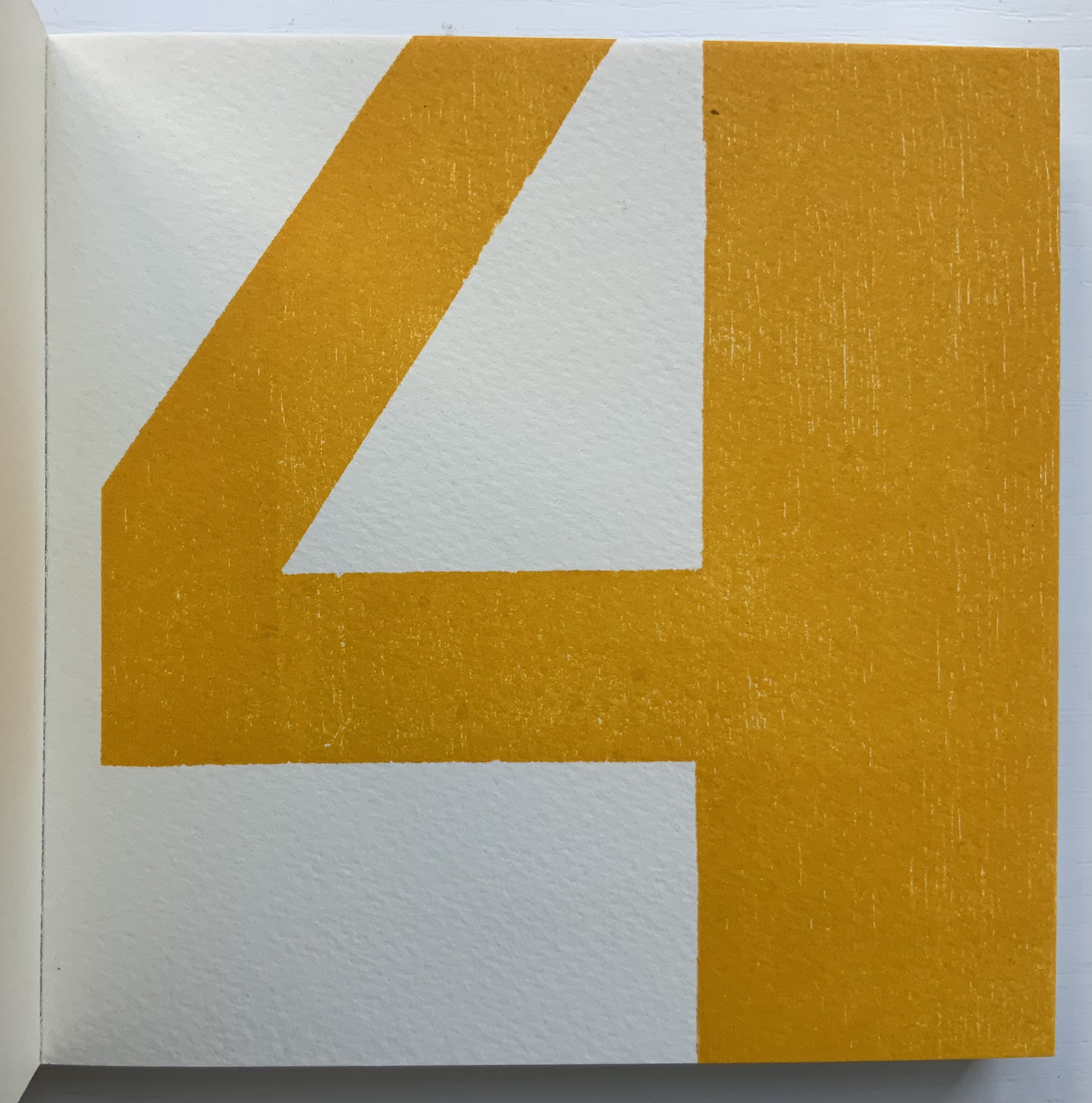

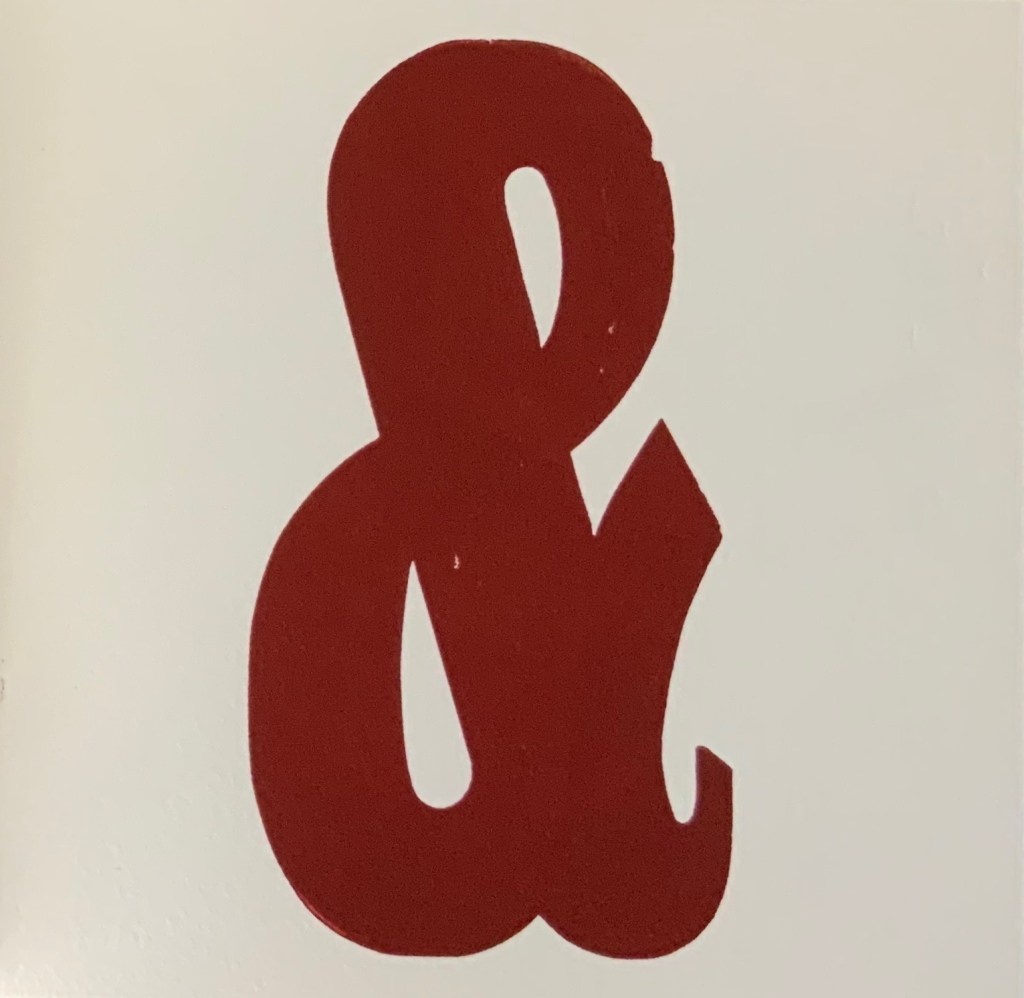

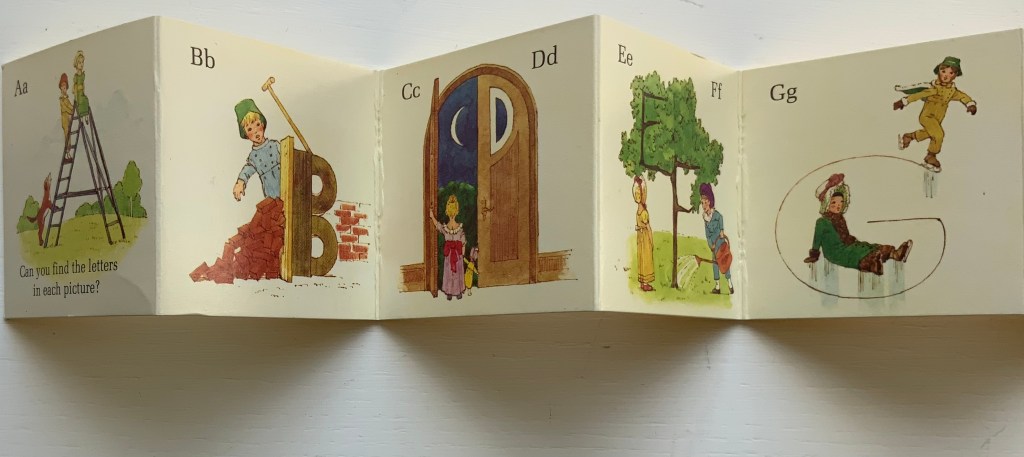

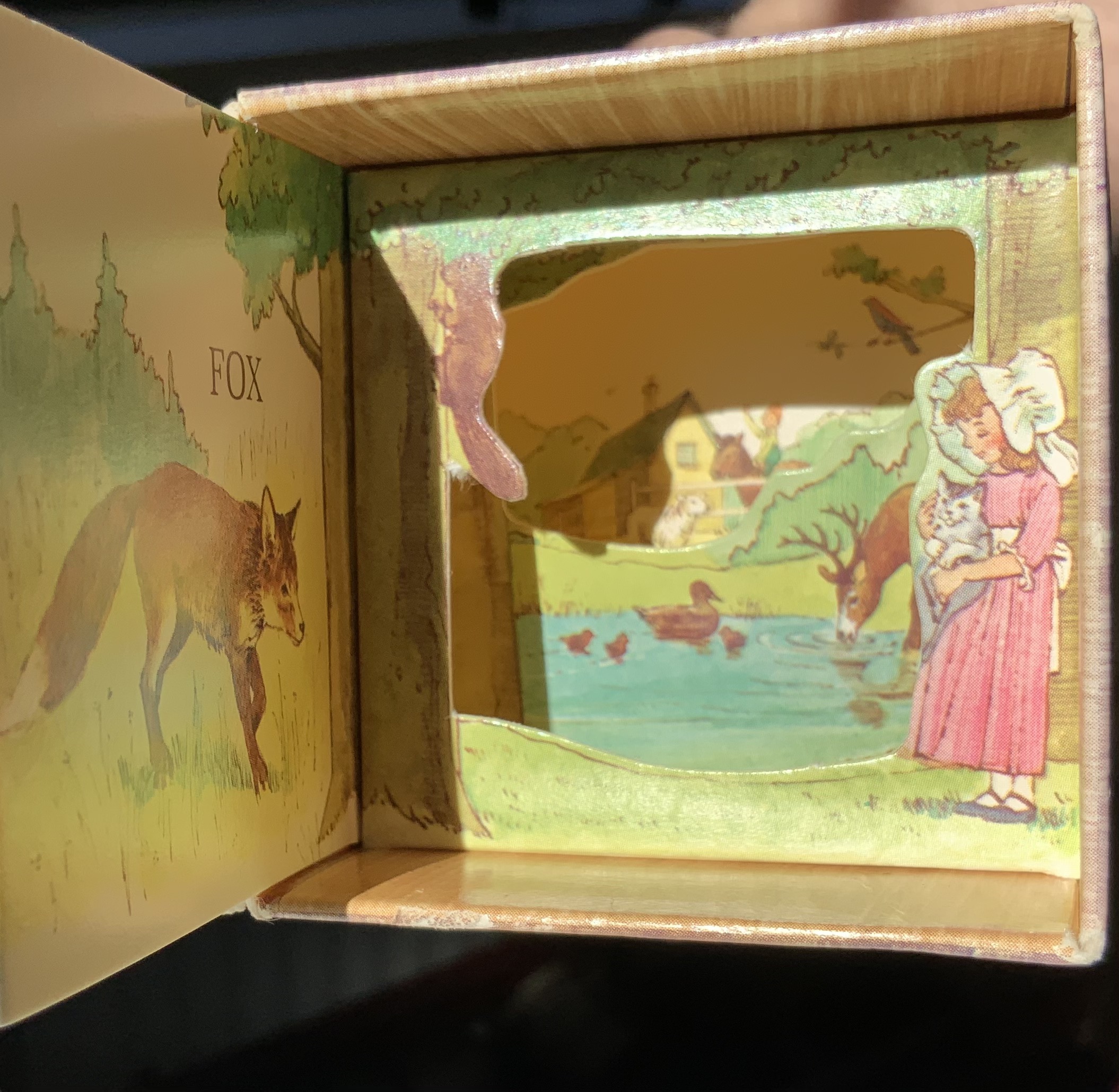

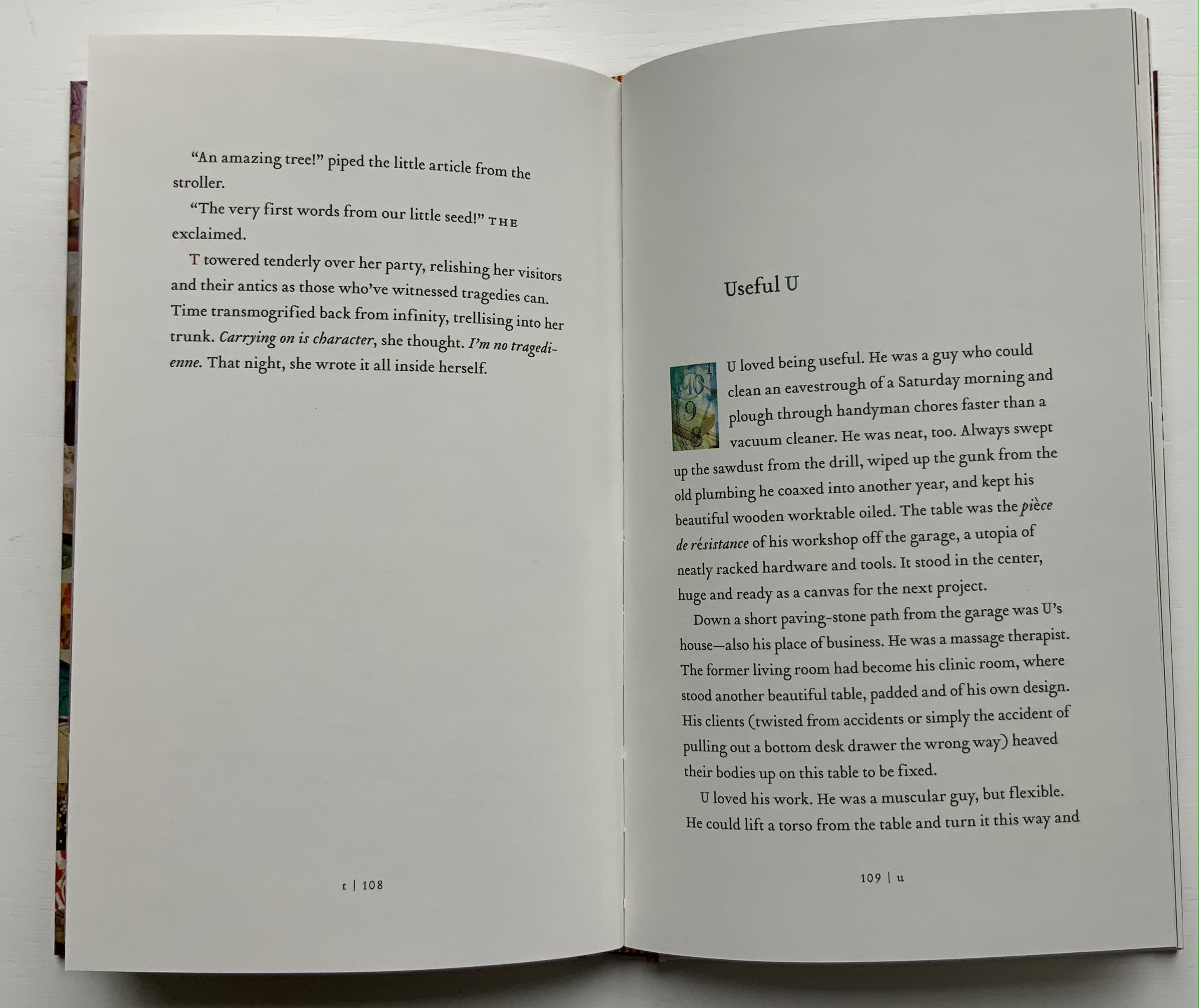

The very structure and working of Nasshan’s Würfelwurf underscore his title’s distinction between a single act and repetition of the act. On its front cover, the word würfelwurf splits in two, one half printed over the other on the slip woven into the slits in the front cover. The slip angles downward from left to right suggesting action, which comes aplenty inside the book.

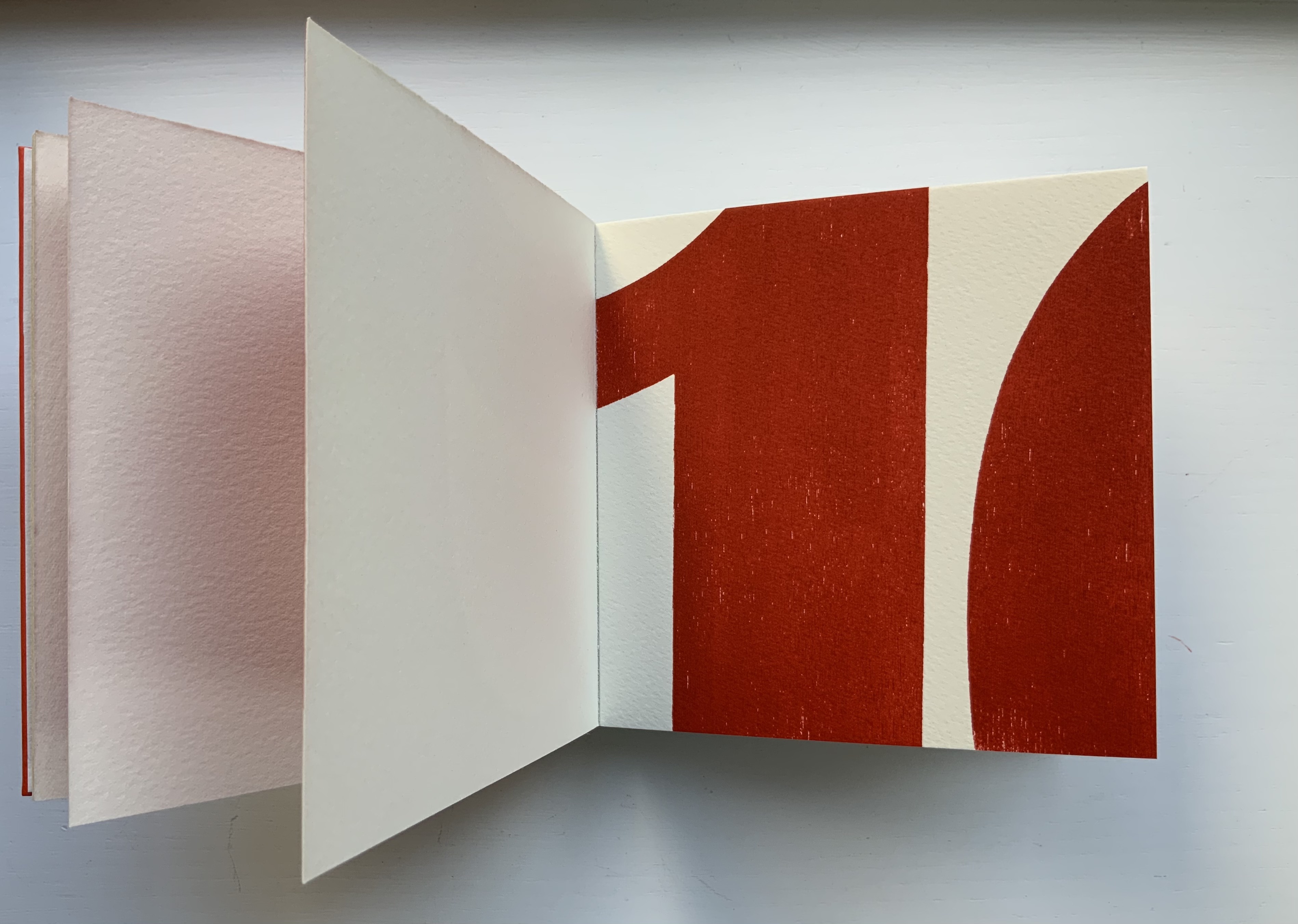

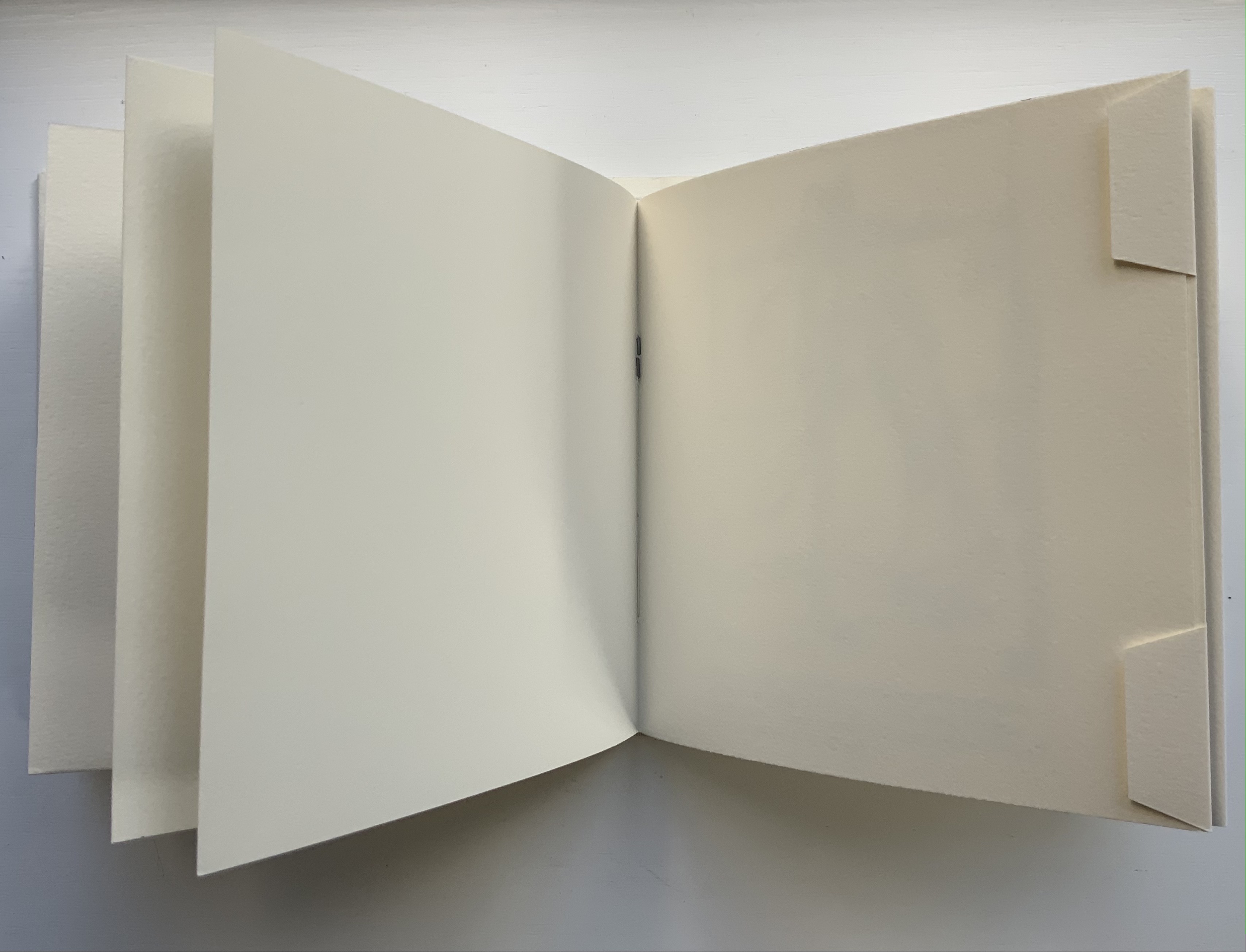

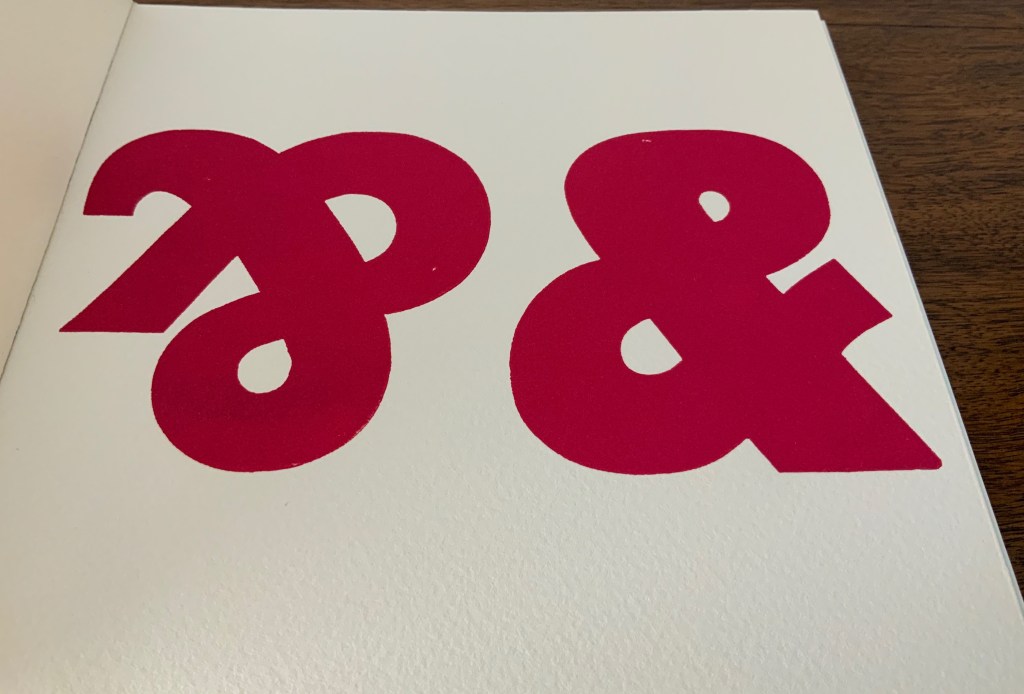

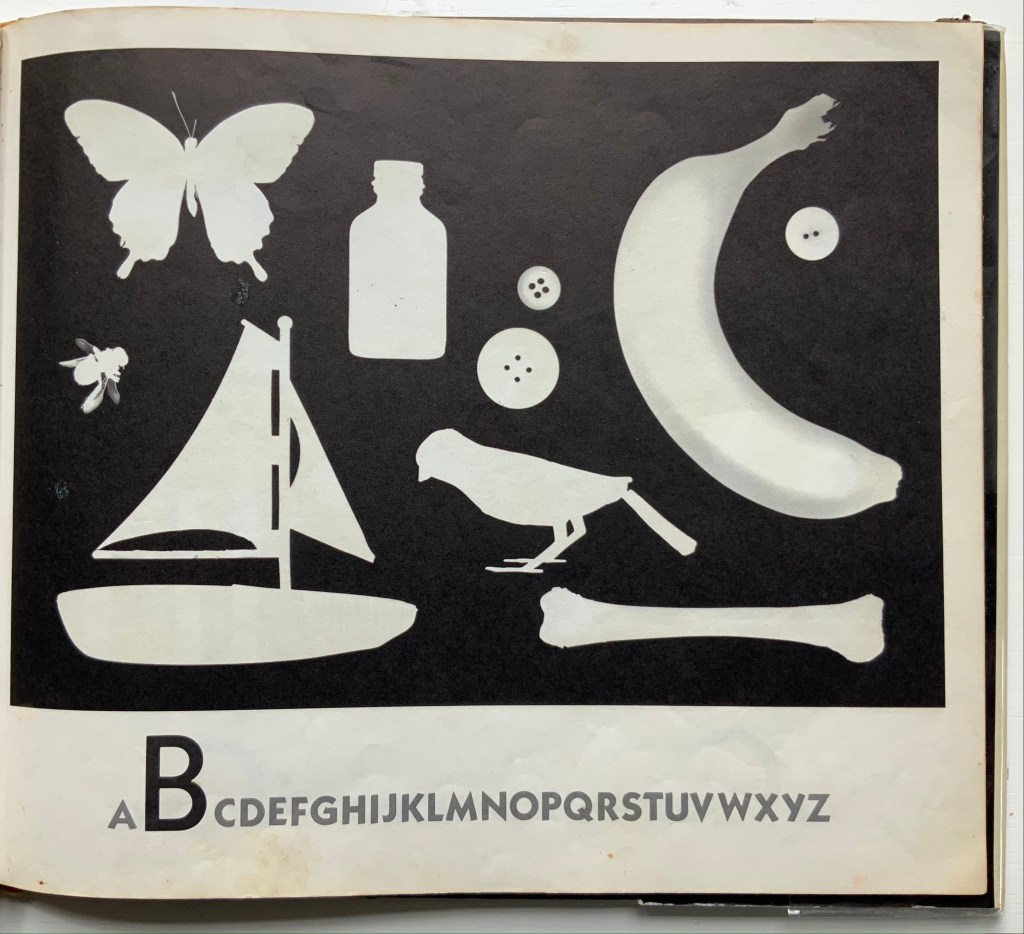

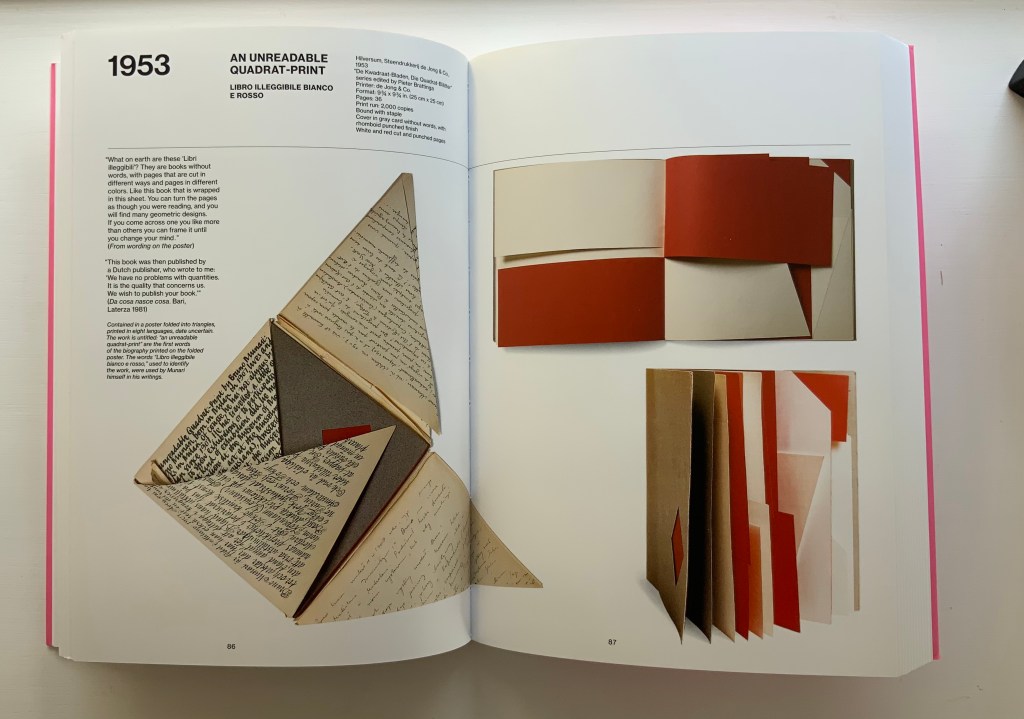

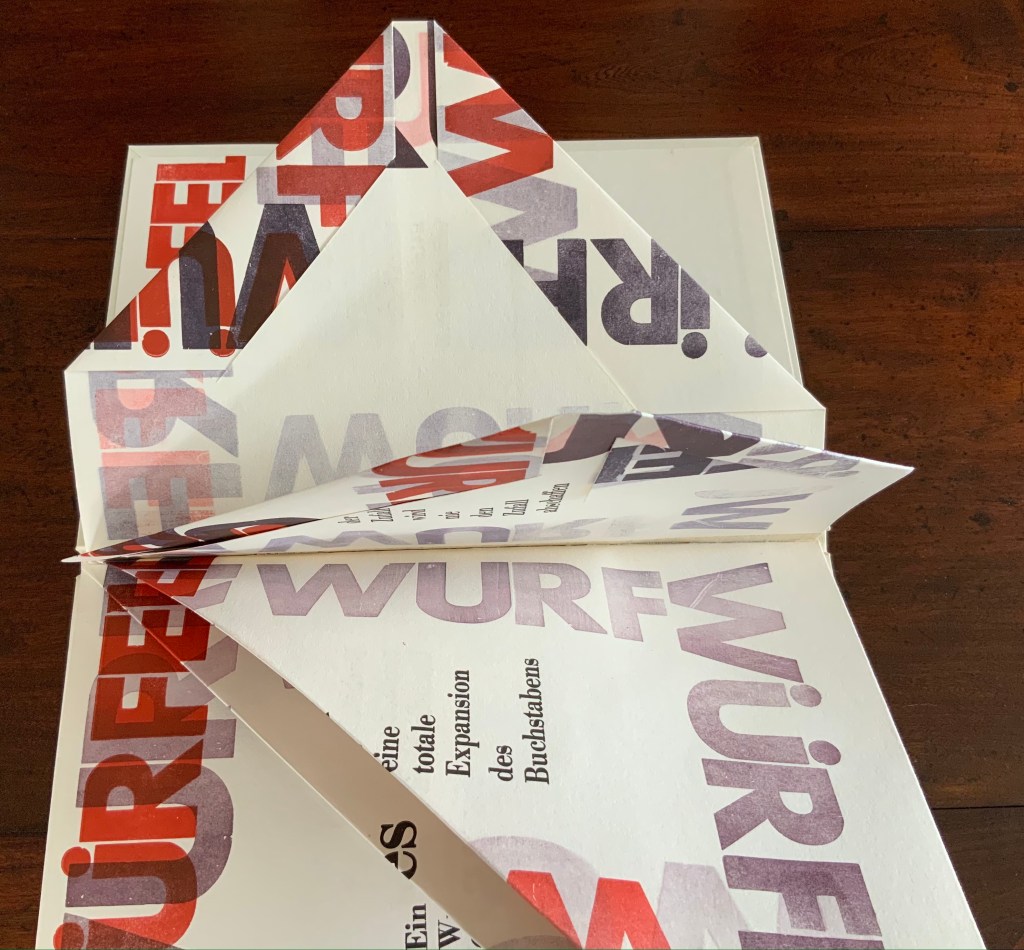

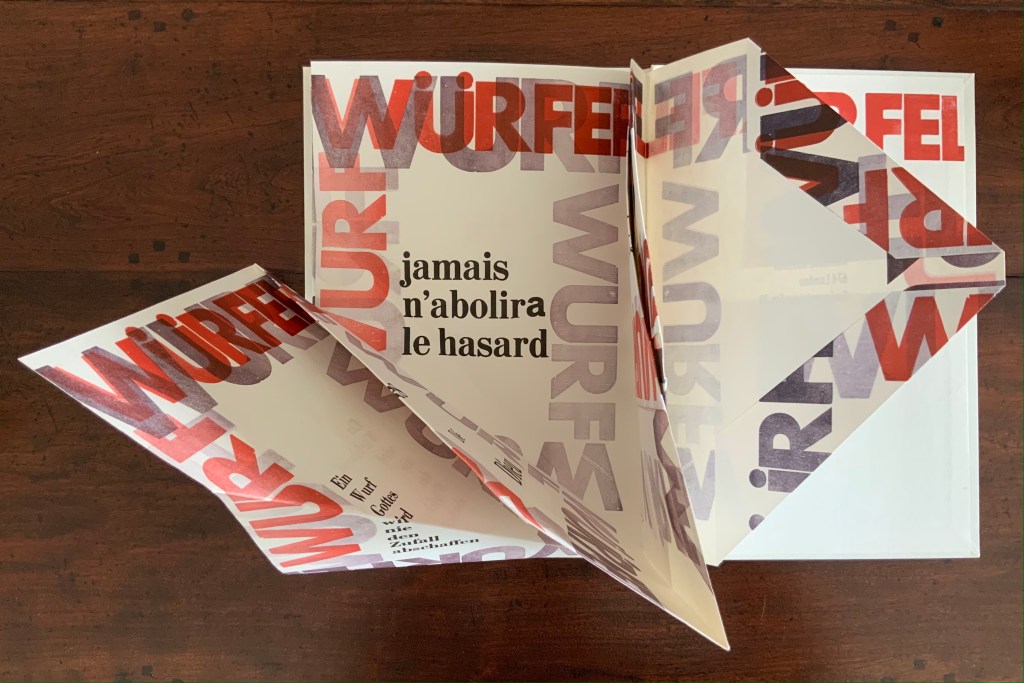

Some pages are cut, their corners folded and tucked in. One gathering consists of a sheet 688 x 470 mm that is creased with mountain- and valley-folds and untrimmed at the bottom edge so that it unfolds into a base that spills out beyond the covers. Pages take on dice-shaped edges and planes that seem to roll from within and against the book. The achieved effect of motion recalls Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2) or Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.

Although the title of Mallarmé’s poem appears, most of the text scattered across the surfaces comes from his other writings; for example, peindre, non la chose, mais l’effet qu’elle produit (“to paint, not the thing, but the effect it produces”); tout, au monde, existe pour aboutir à un livre (“everything in the world exists to end up in a book”); and Das Buch ist eine totale Expansion des Buchstabens (“The book is a total expansion of the letter”). When that large folded gathering comes, though, the Mallarmé’s words begin to be jumbled: Ein Würfelwurf wird nie das Würfelspiel abschaffen (“A throw of the dice will never abolish the game of dice”) and Ein Wurf Gottes wird nie den Zufall abschaffen (“A throw from God will never abolish chance”).

Strangest of all is the mangling of émet from the poem’s final line Toute pensée émet un coup de dés (“All thought emits a throw of the dice”). The word becomes éinet. Not French, not German. Perhaps a typo of “in” for “m”? As it turns out, according to the artist, it is a fluke that the letter “m” available in the font on hand printed poorly, so “i” and “n” provided an alternative three vertical strokes.

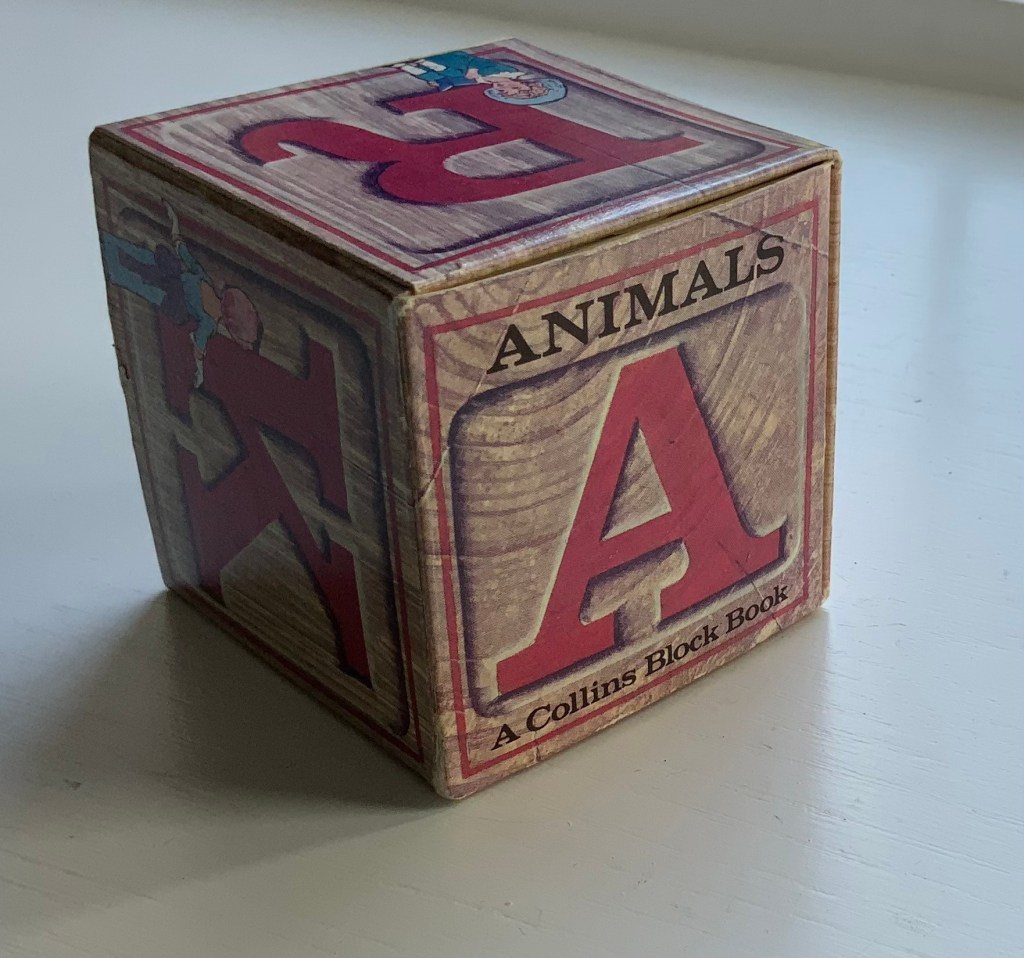

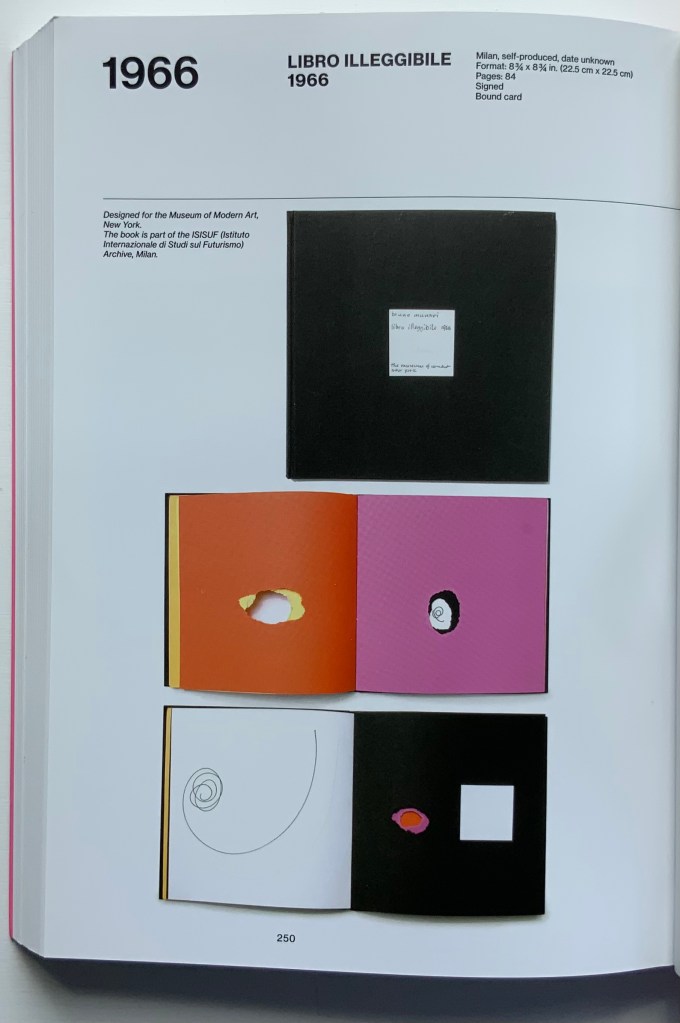

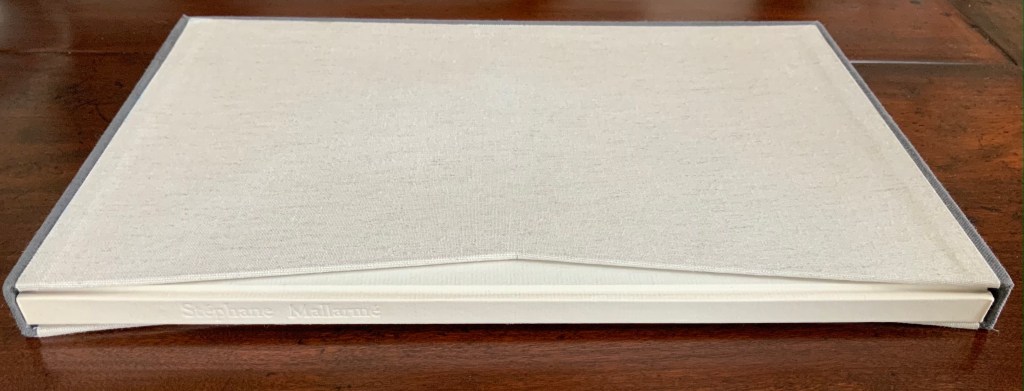

Un Coup: Stéphane Mallarmé (1997)

Un Coup: Stéphane Mallarmé (1997)

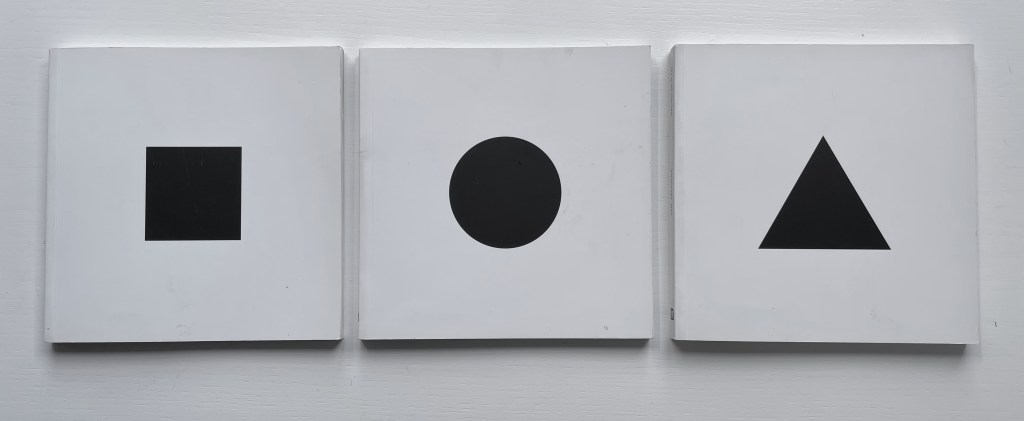

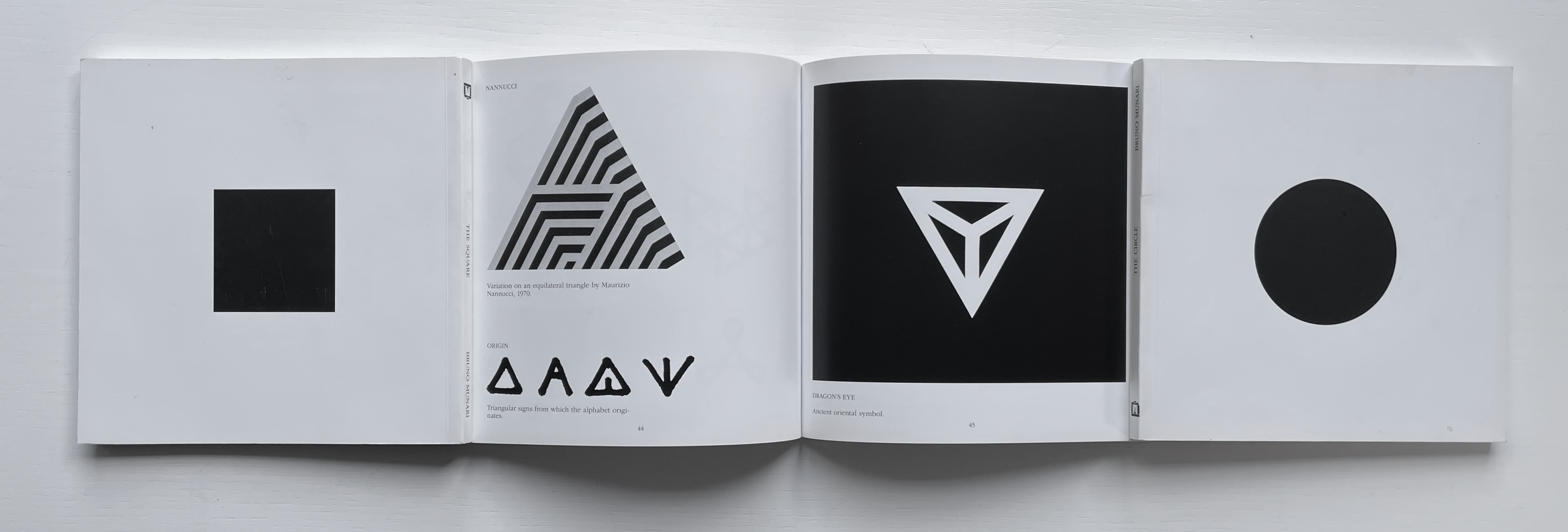

Reinhold Nasshan

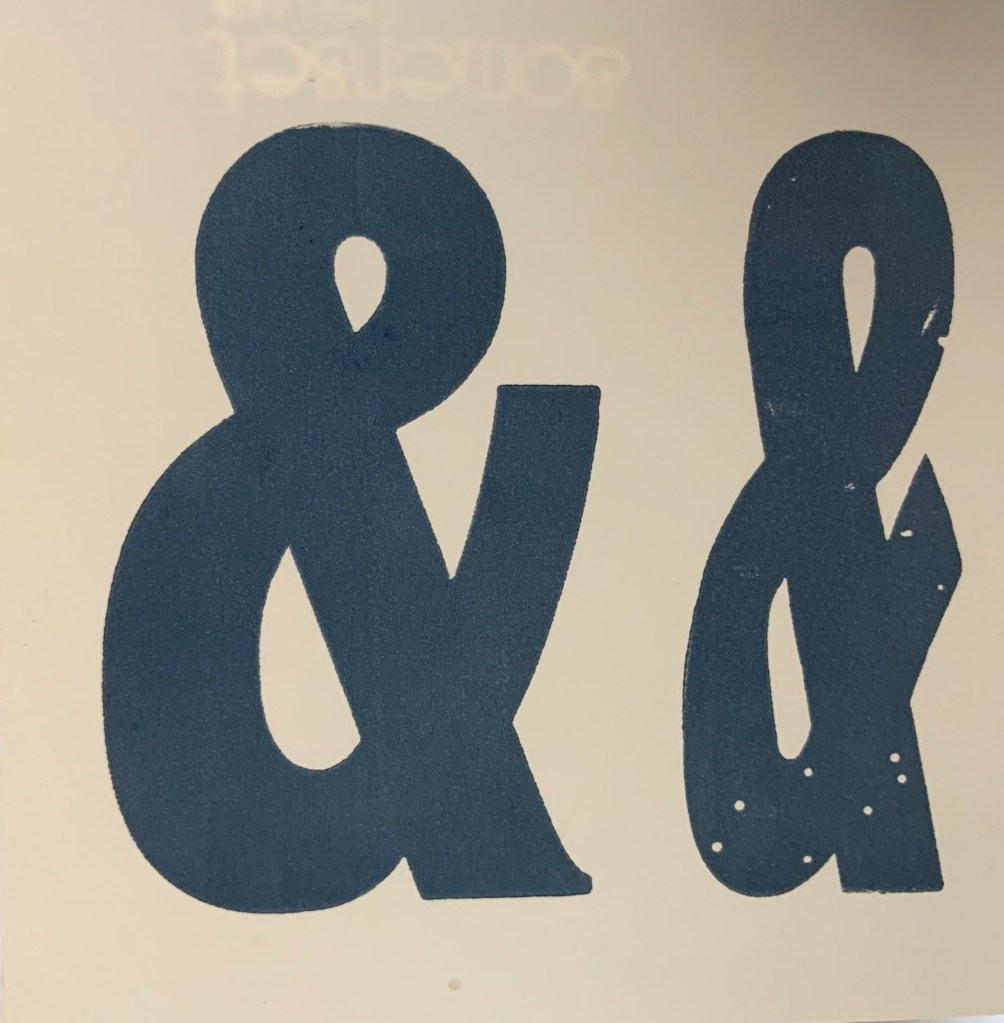

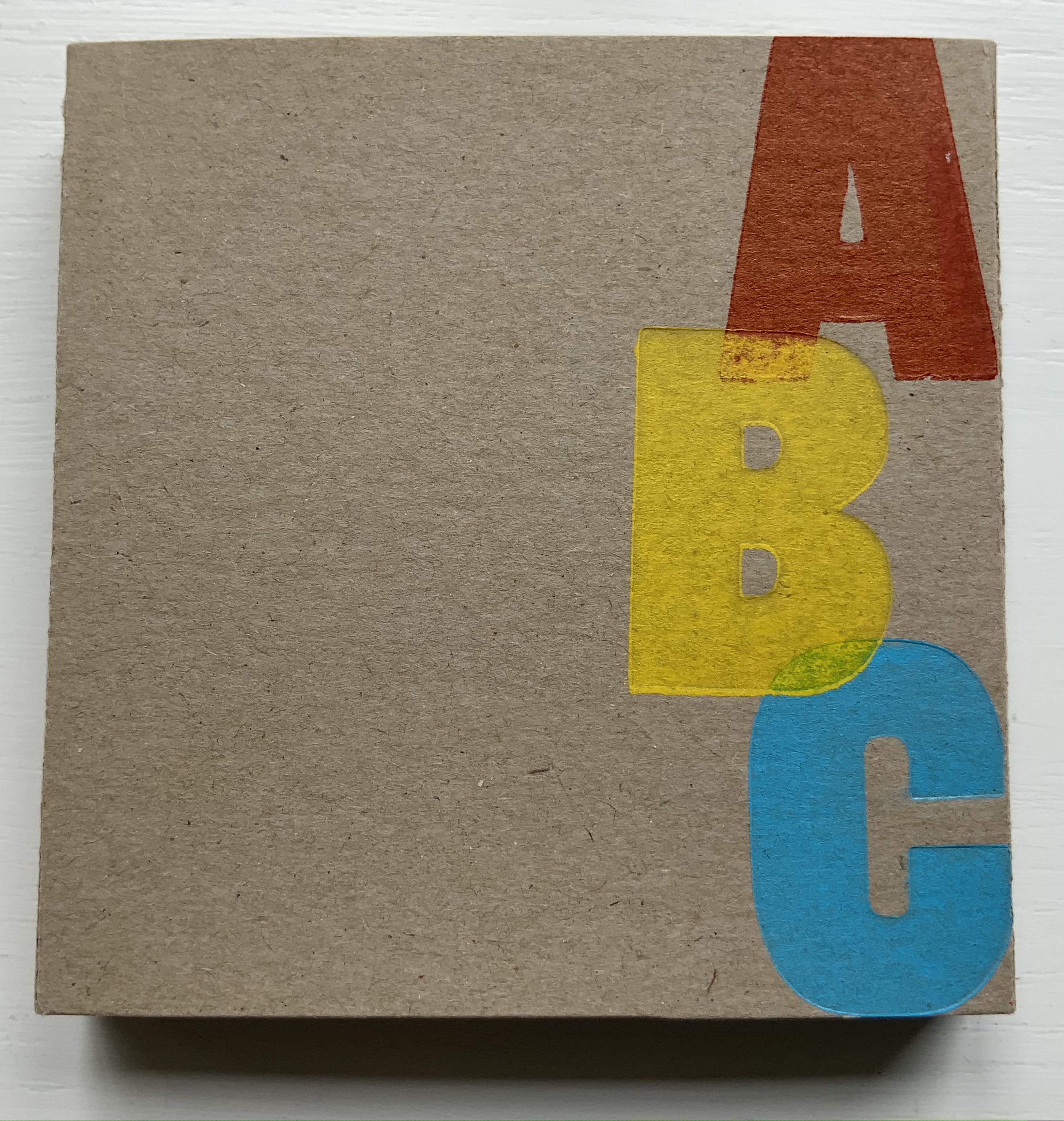

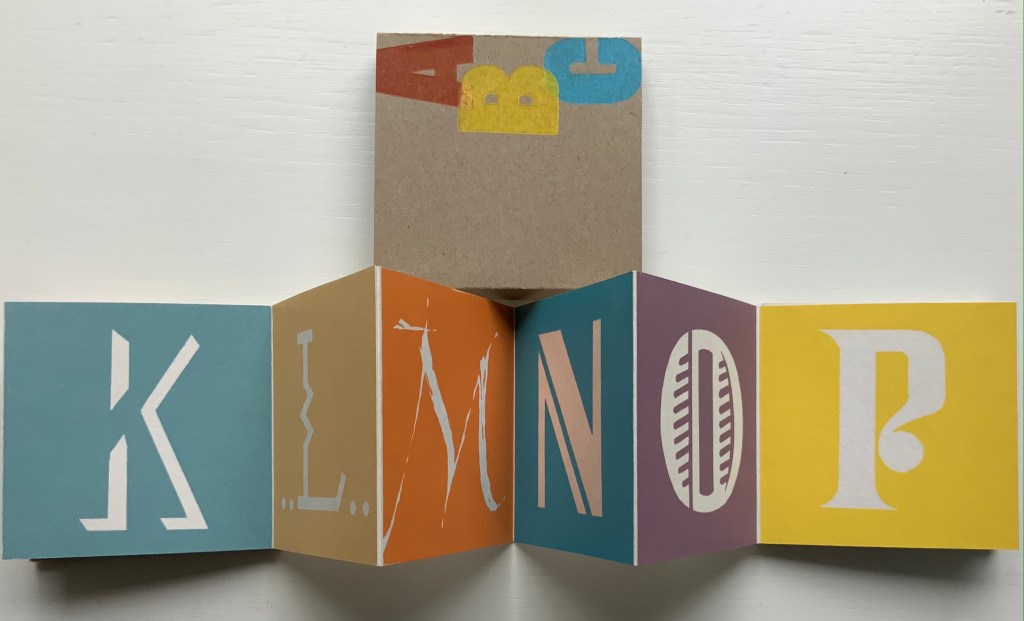

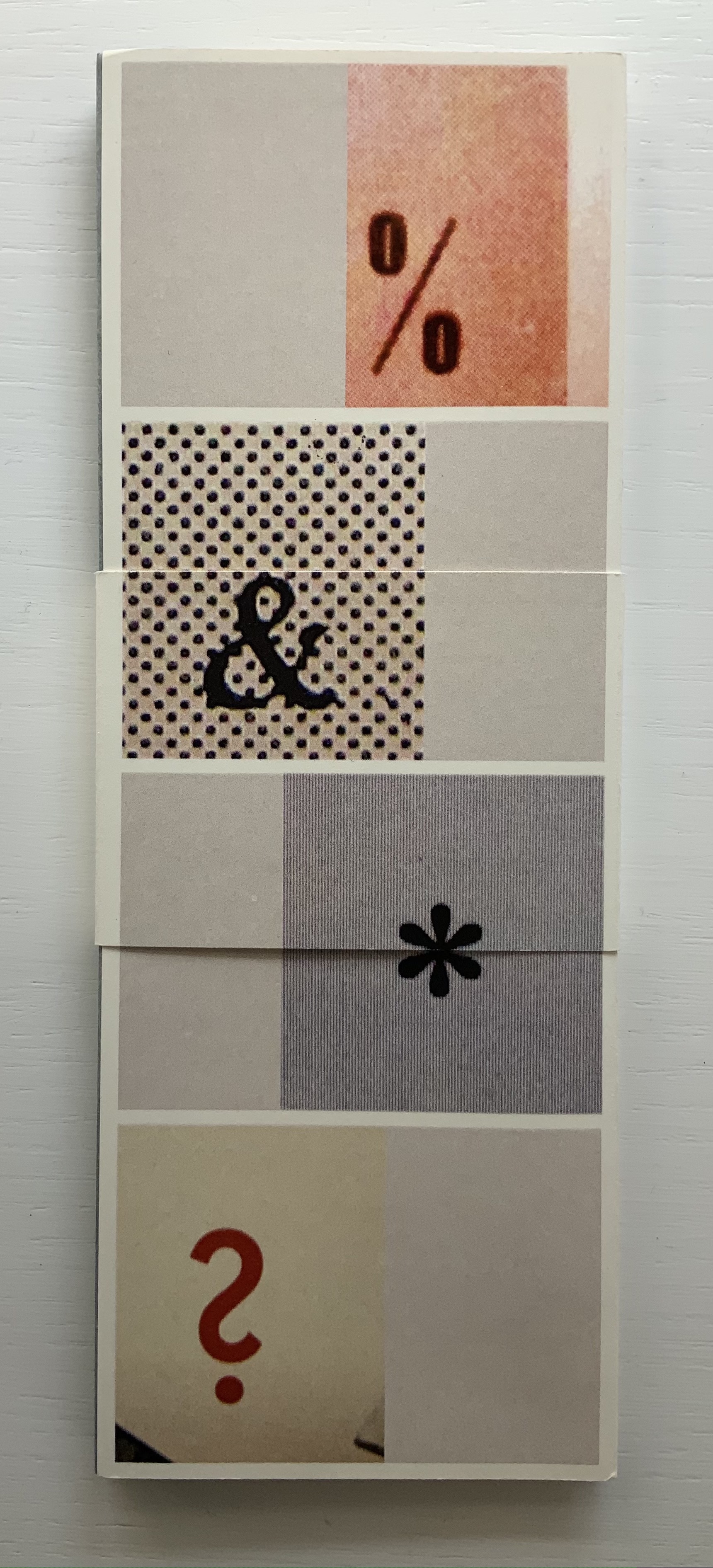

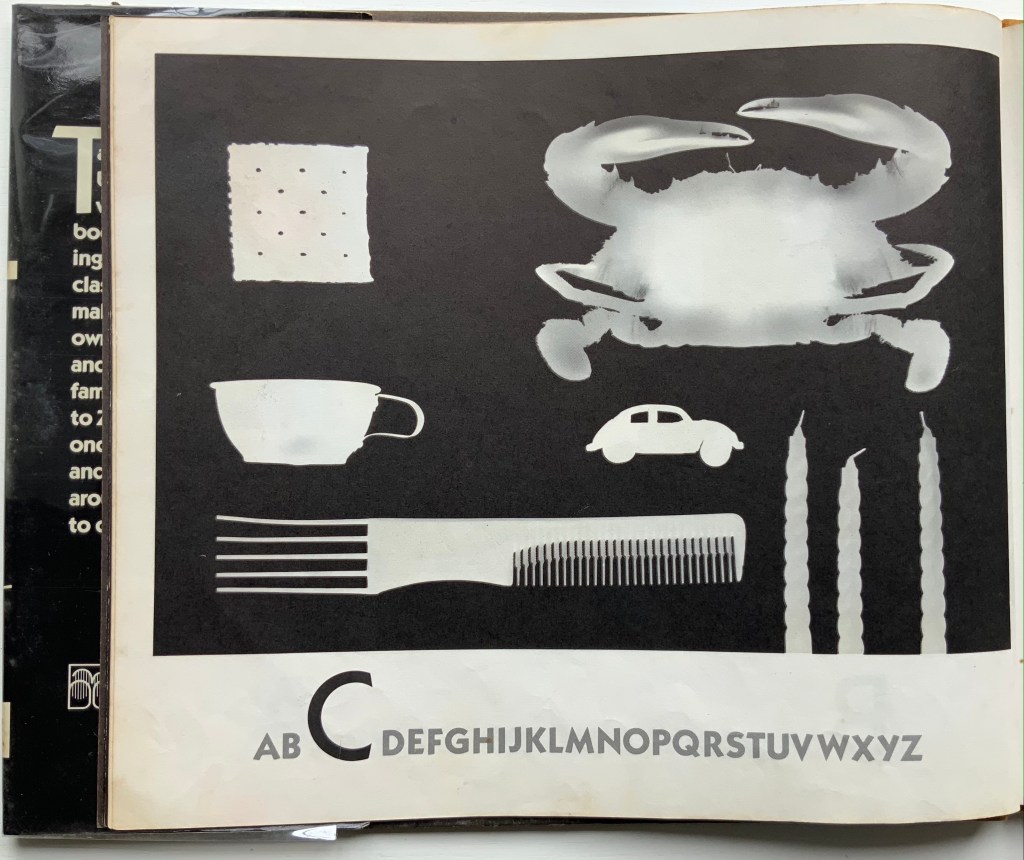

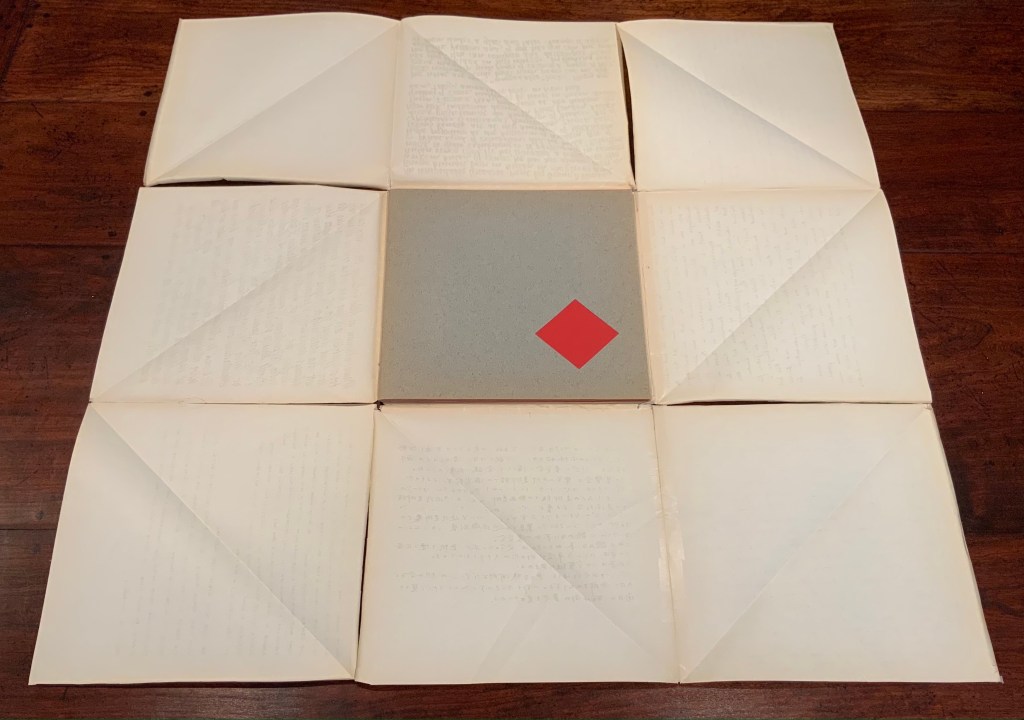

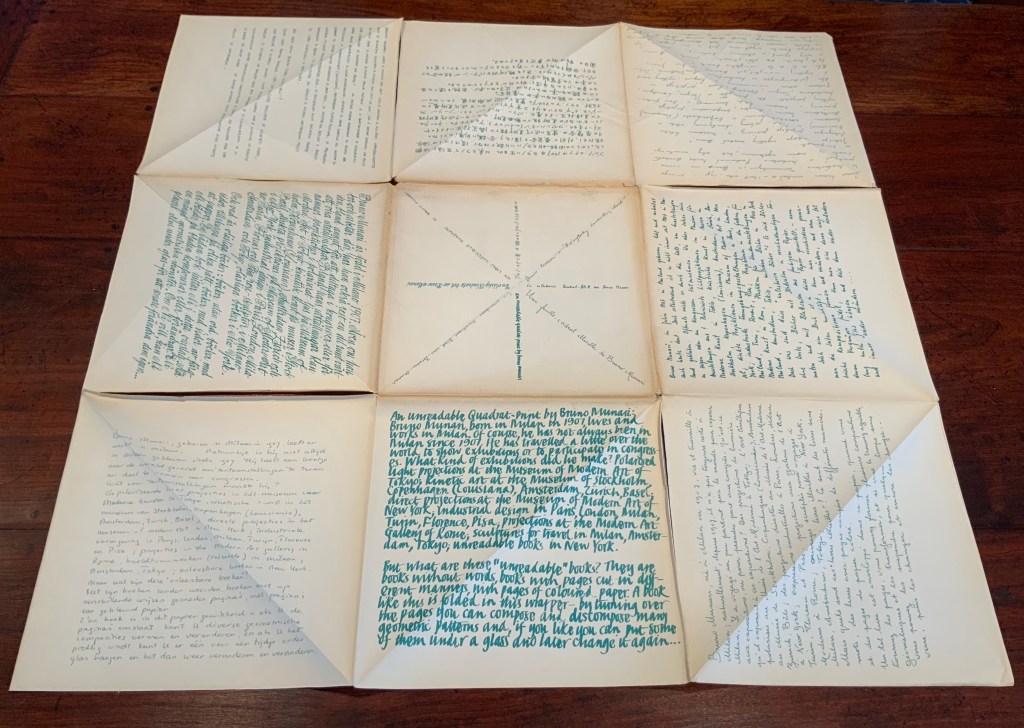

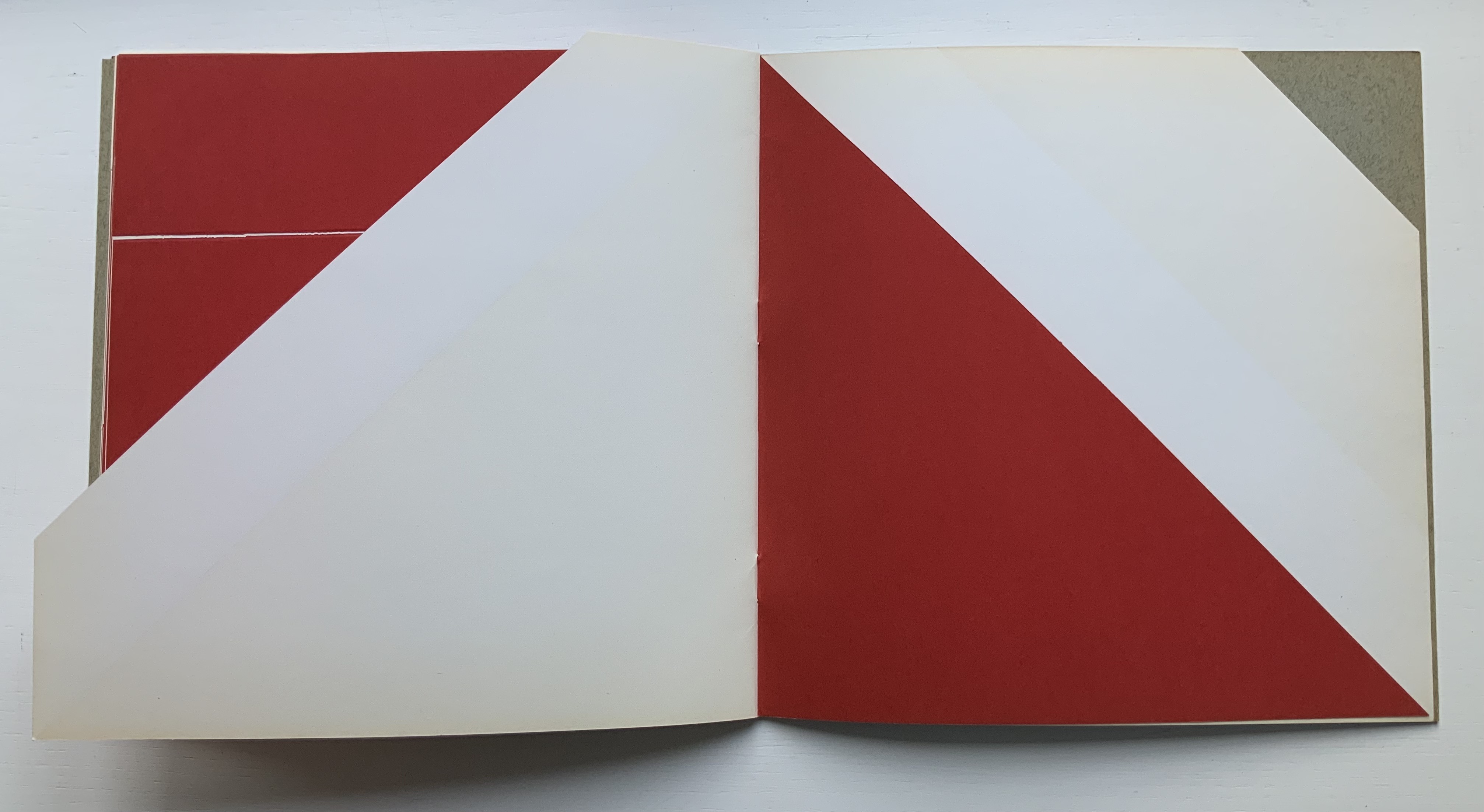

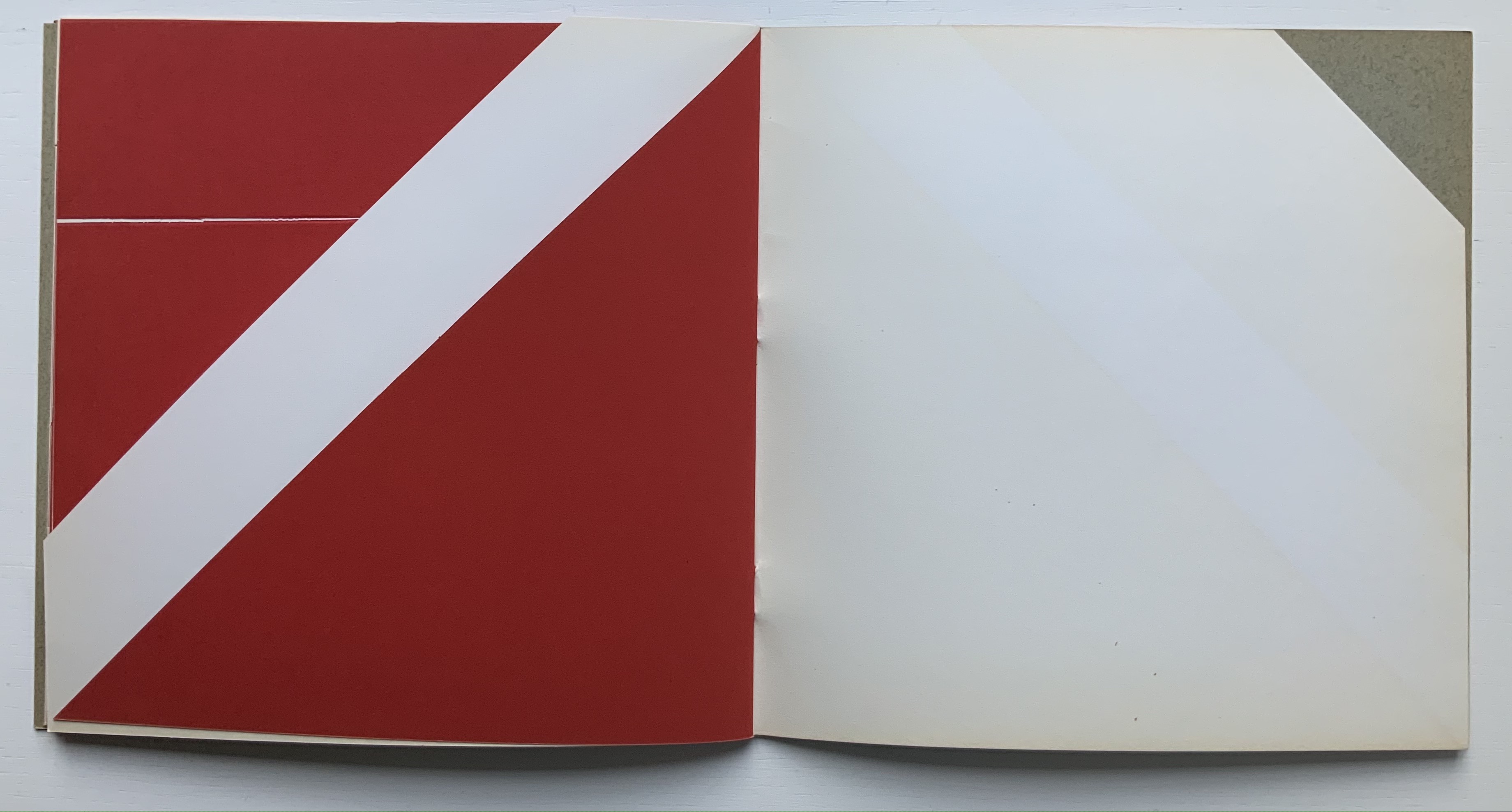

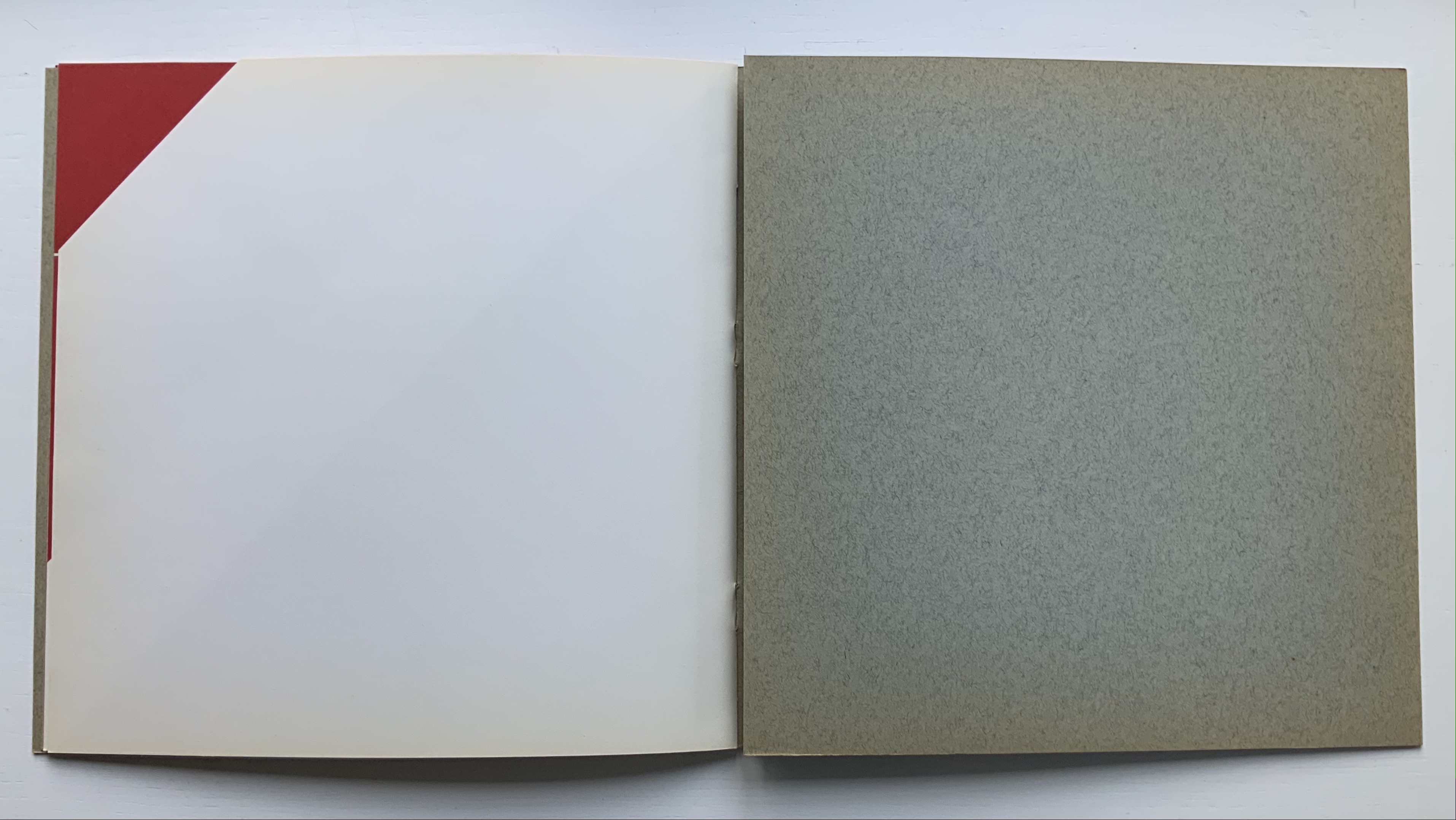

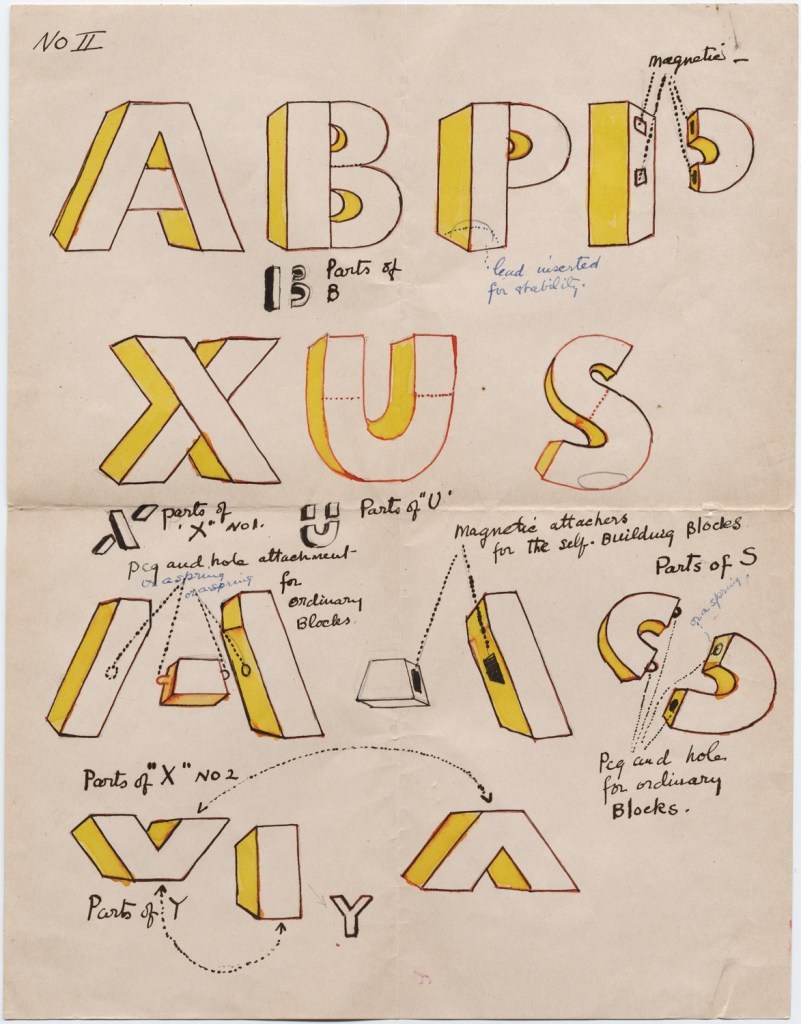

Flexible triangular cloth-covered book boards, 4 cotton paper squares folded into origami water bomb base and glued. Triangle: 127 x 127 x 179 mm; Square “pages”: 166 x 166 mm. Acquired from the artist, 24 February 2021.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Displayed with artist’s permission.

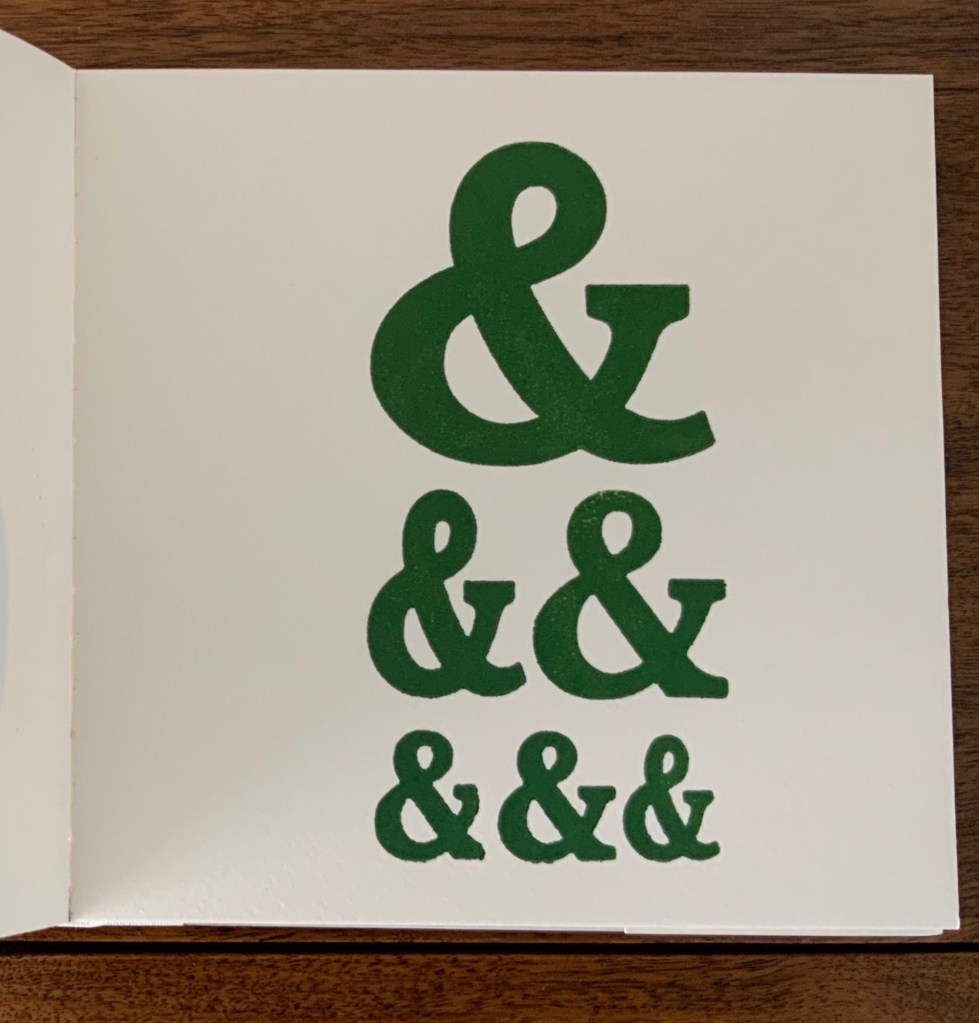

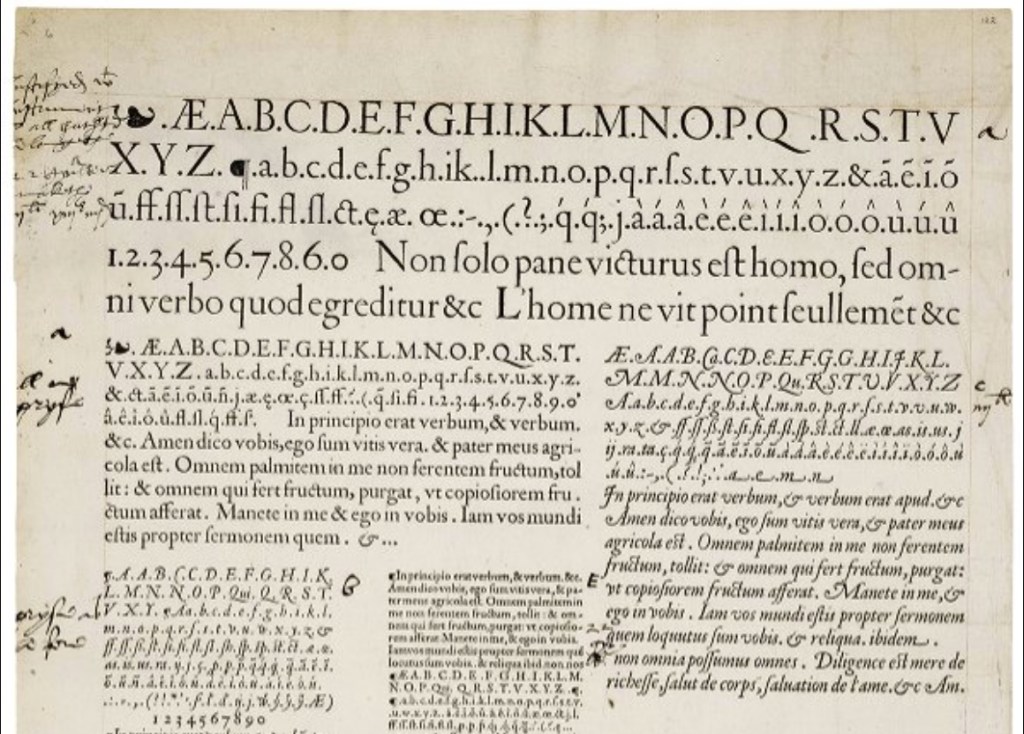

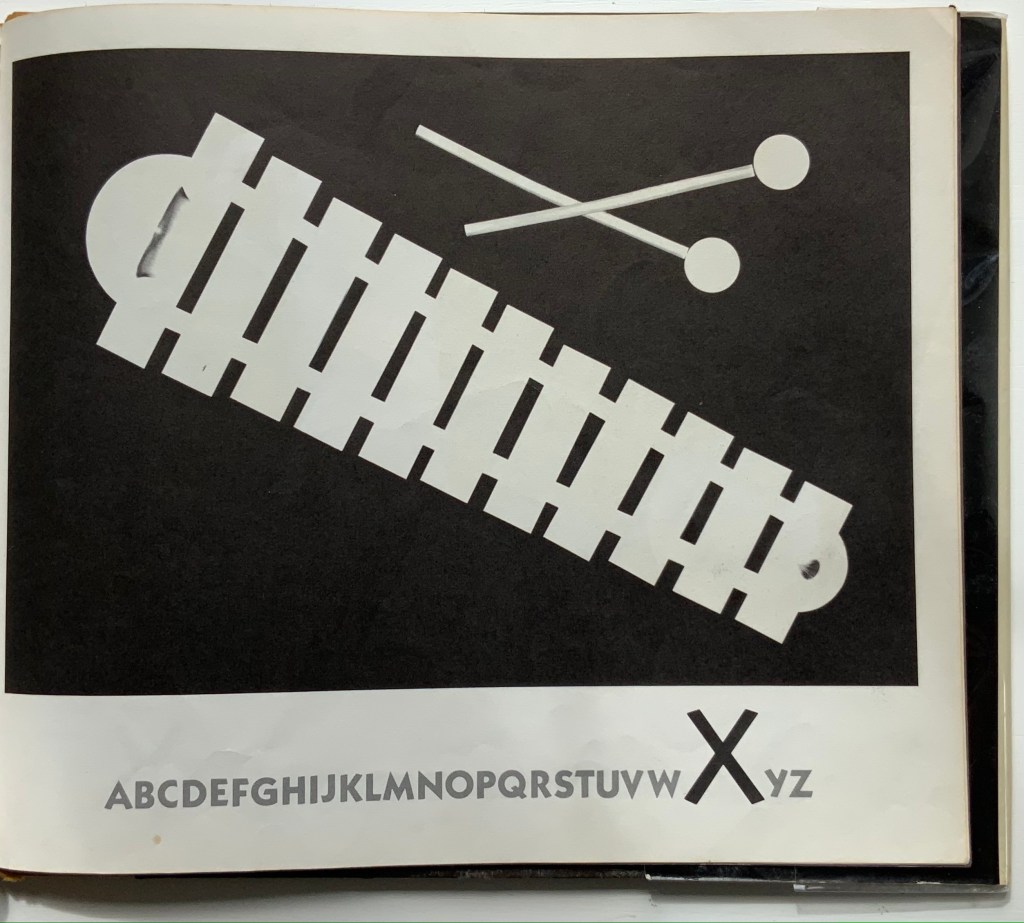

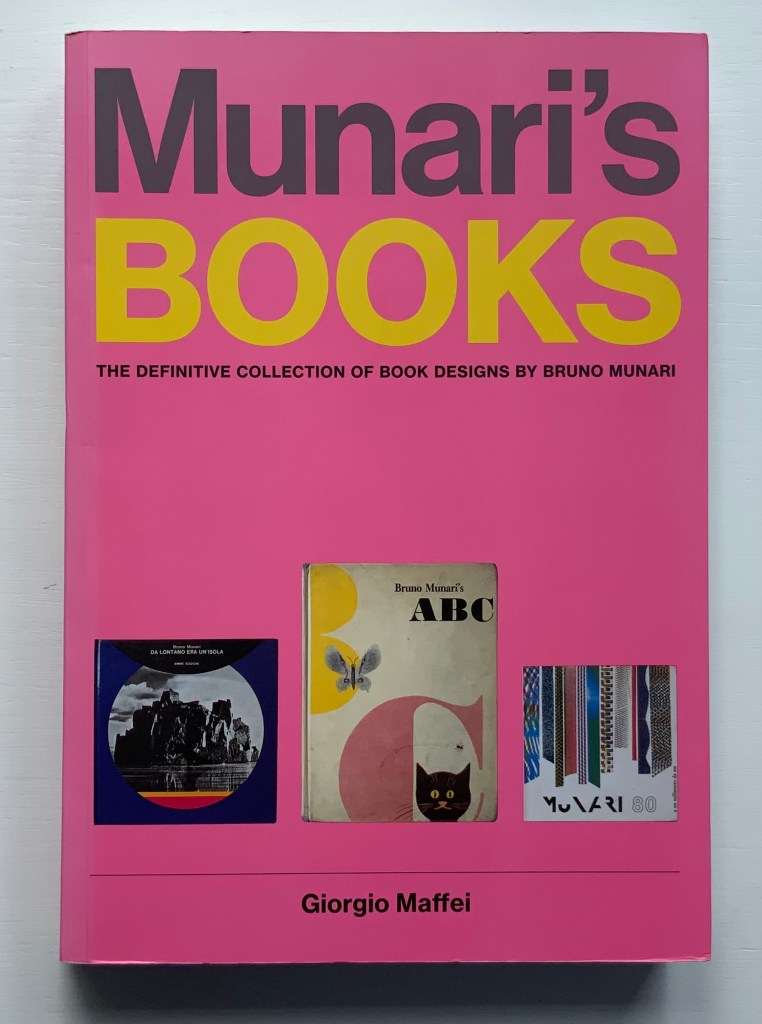

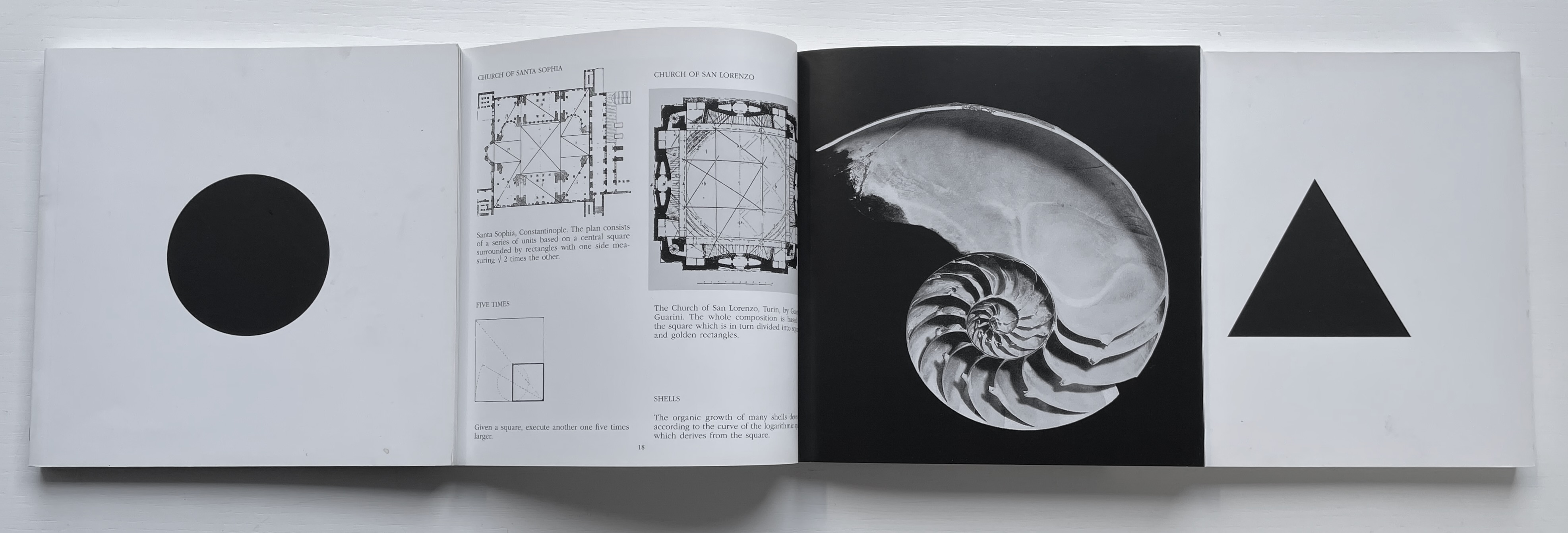

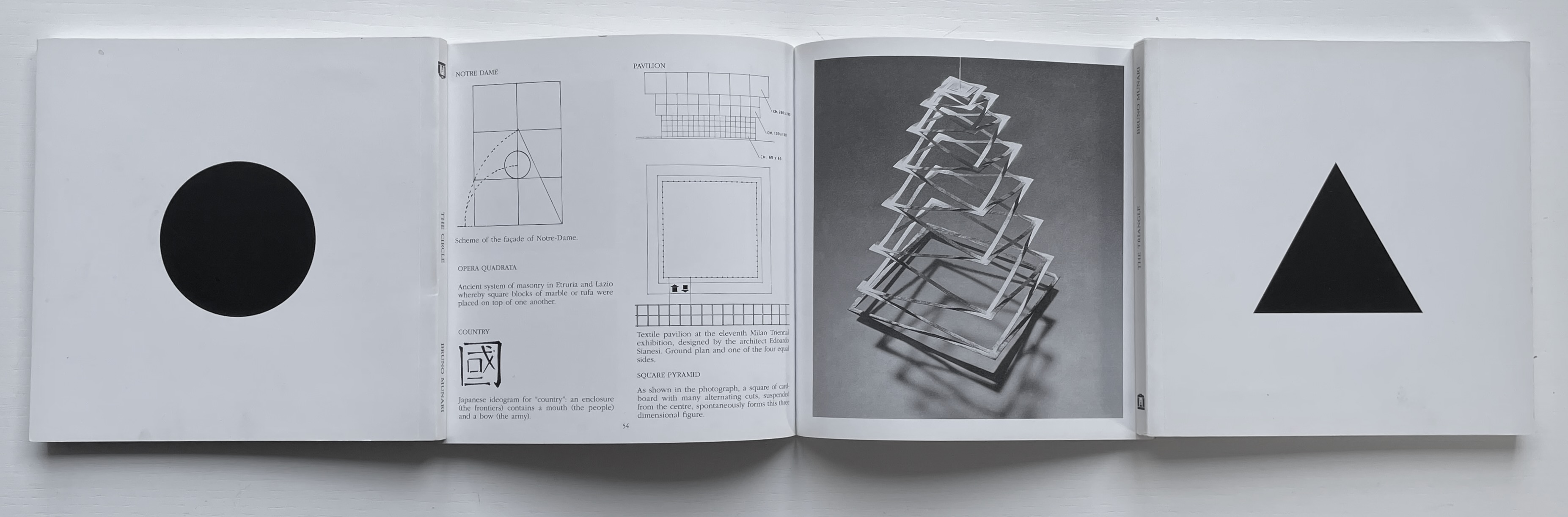

Nasshan also refers to this as a “letter sculpture”. Inviting the reconfiguring as with the works of Eleonora Cumer or Bruno Munari, or simply constant fiddling as with a paper fortune teller, Un Coup is more three-dimensional than Würfelwurf. As with Würfelwurf, this work lets the “moment of movement itself, the transition between the throw and the impact of the dice, emerge graphically” (moment der bewegung selbst den ubergang zwischen dem werfen und dem auftreffen der wurfel, graphisch hervortreten zu lassen). With less surface than Würfelwurf, though, it has fewer extracts from Mallarmé’s writings. Indeed, along with the physical shape shifting, the enlarged letters overprinted at multiple angles to one another combine to make this work more abstract than extract. But because text and book are material from which, on which and with which Nasshan creates, the abstract retains its links to the book.

Also a painter, Nasshan’s works fall into two categories or surfaces — painted books and painted canvases. Though lacking the shape of a book, his abstract paintings retain that link to “the world of Letters” in shapes and figures that evoke hieroglyphics, Chinese characters, typography and even cave paintings. His influences appear equally eclectic — though more Kandinsky, Klee and Miró than Pollock or Rothko — which matches up with his choice of substrates in fiction and nonfiction. When not choosing works from the ancient, classical or Romantic periods (from Gilgamesh to Seneca to Hölderlin), he chooses Apollinaire, Beckett, Celan, Joyce or Wittgenstein among others from the Modern period.

A wider audience would profit from Nasshan’s works. At least these two and others that might enter the Books On Books Collection will be available in the 2022 exhibitions celebrating the 125th anniversary of the publication of Un Coup de Dés in Cosmopolis (May 1897).

Further Reading

Bolton, Ama. 4 November 2013. “Saturday 2 November at the Oxford Book Fair“. Barleybooks.

Guckes-Kühl, Karen. September 2008. “Entdeckungsreise in die Buchkunst“. Buchbinderei Köster.

Klein, Thomas. 7 July 2019. “Die Sprache der Träume“. Wochenblatt-Reporter.de.

Möthrath, Birgit. 29 July 2019. “Reinhold Nasshan zeigt Malerie und Buchobjekte im Frank-Loebschen Haus“. Die Rheinpfalz.

Nasshan, Reinhold. 20 September 2021. Correspondence with Books On Books.