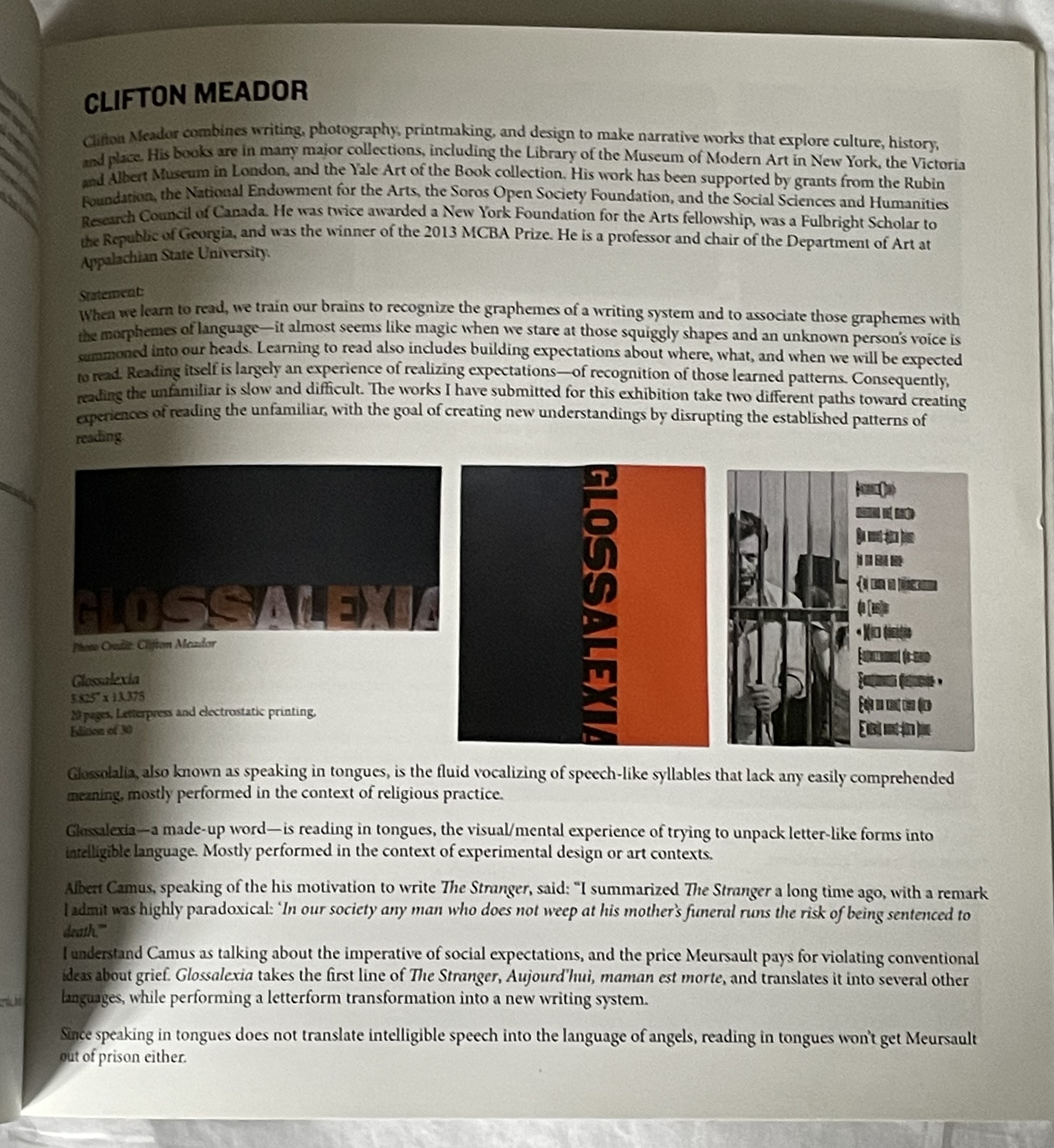

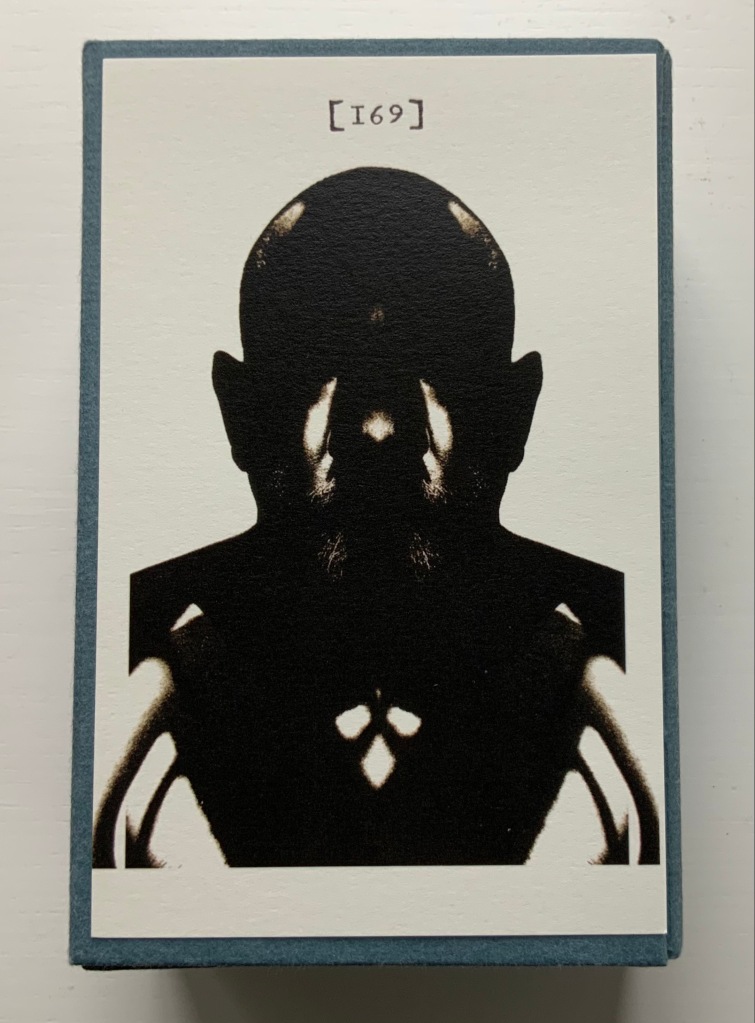

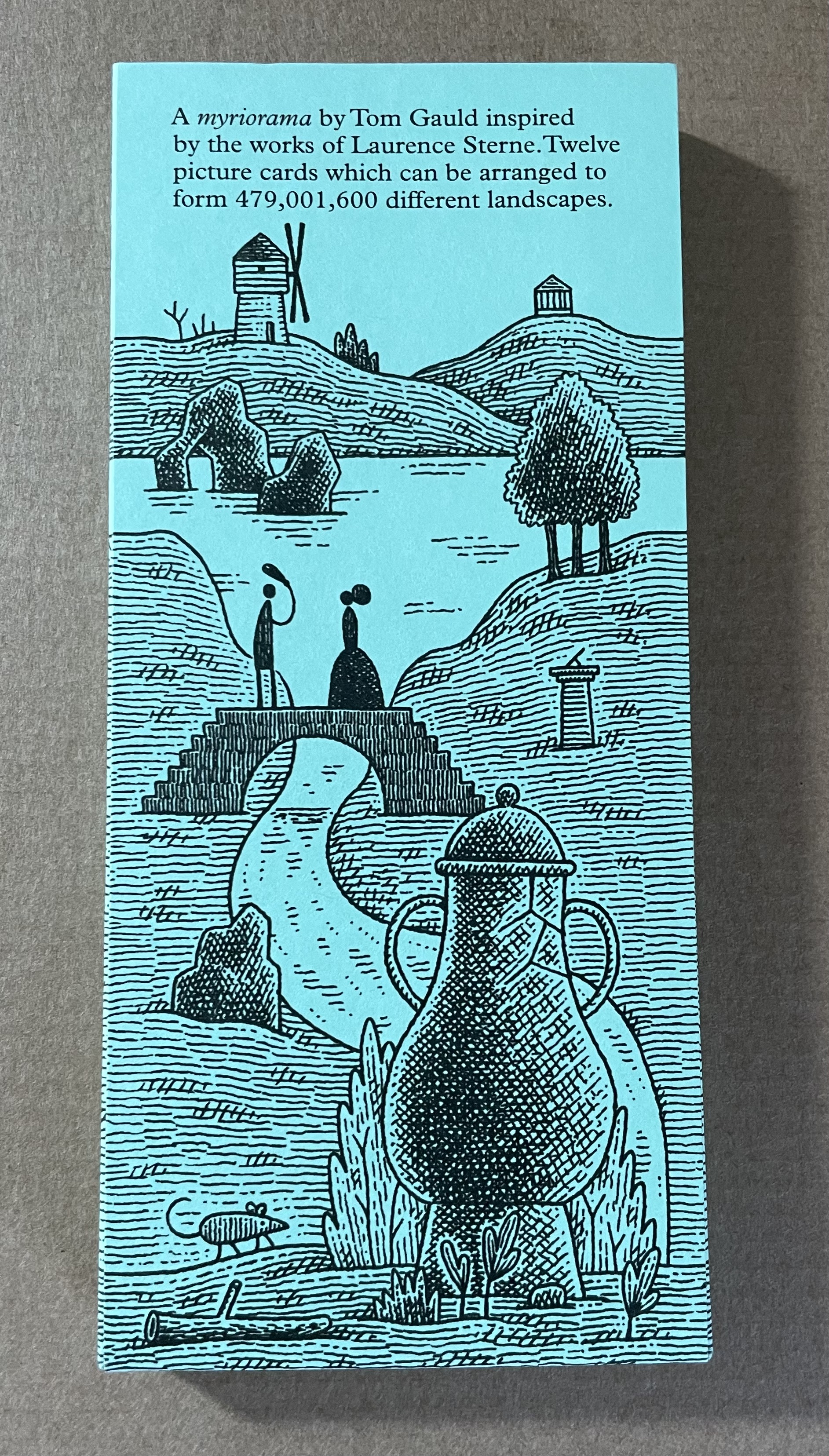

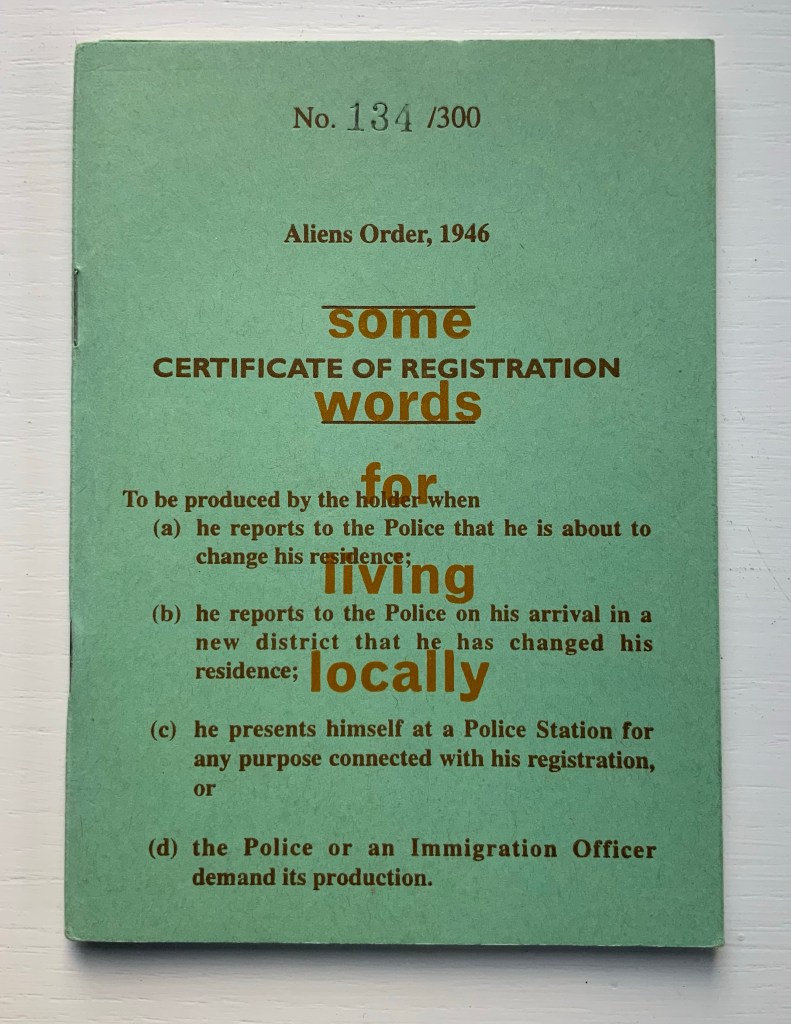

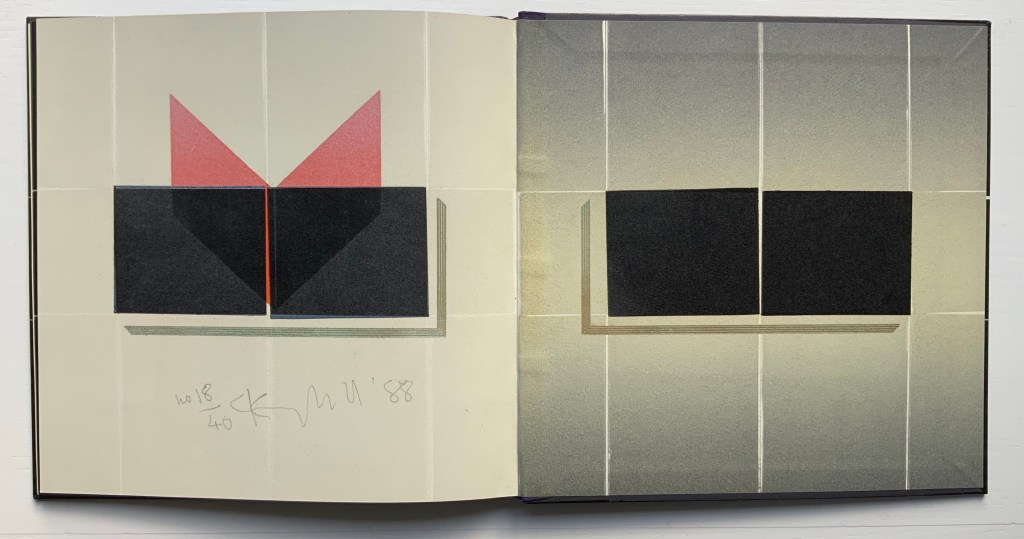

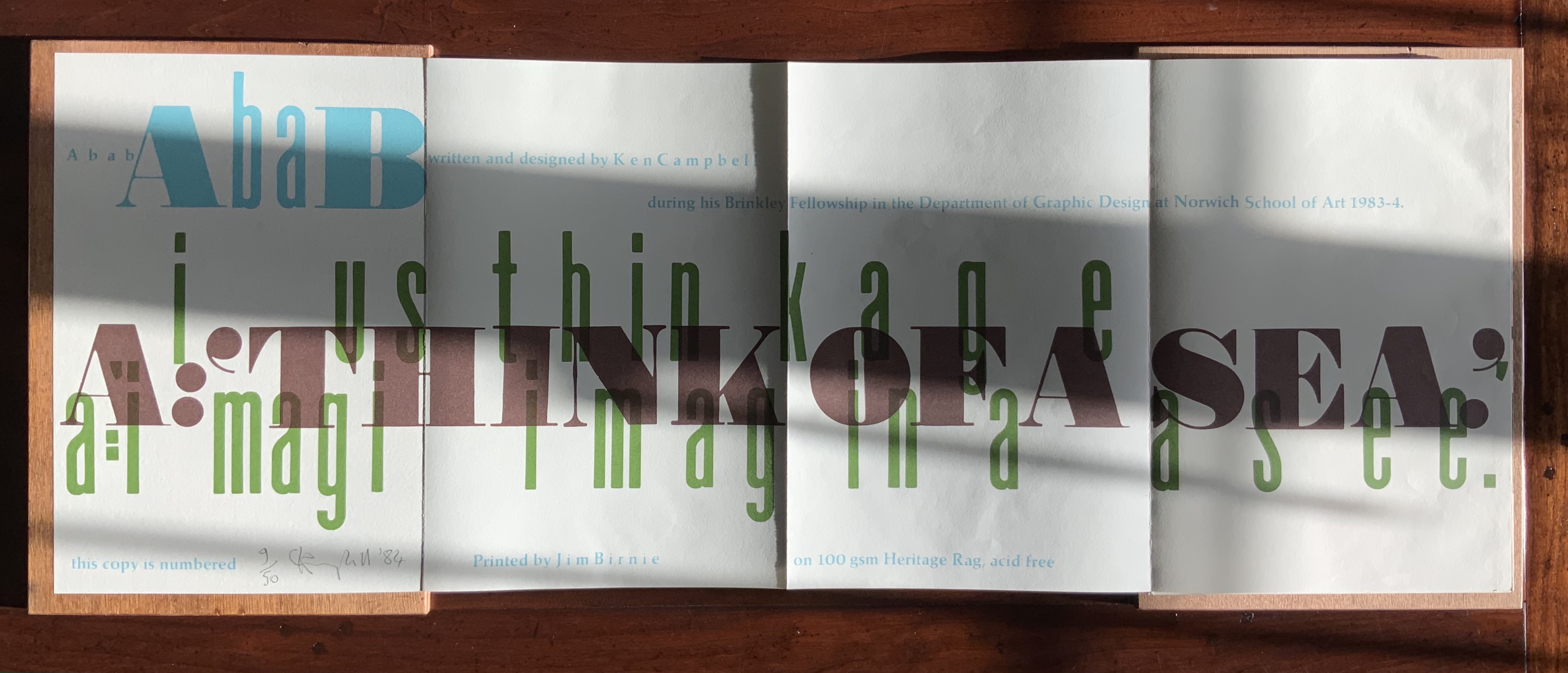

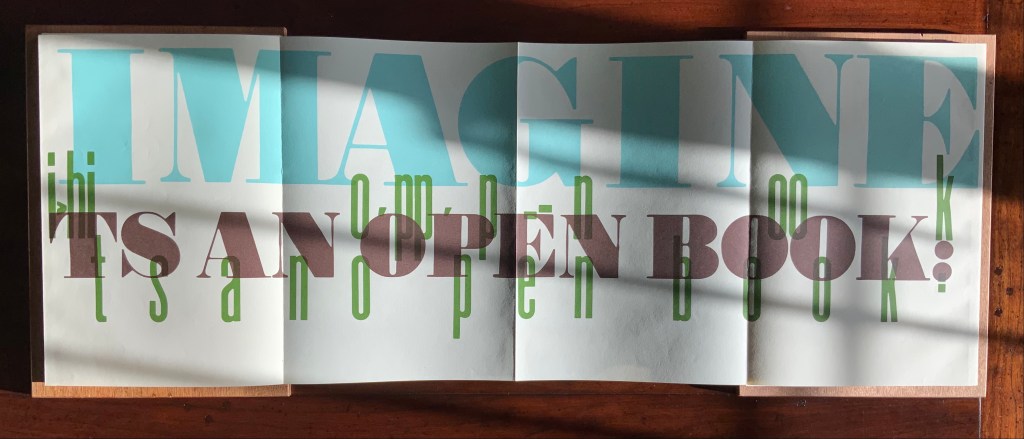

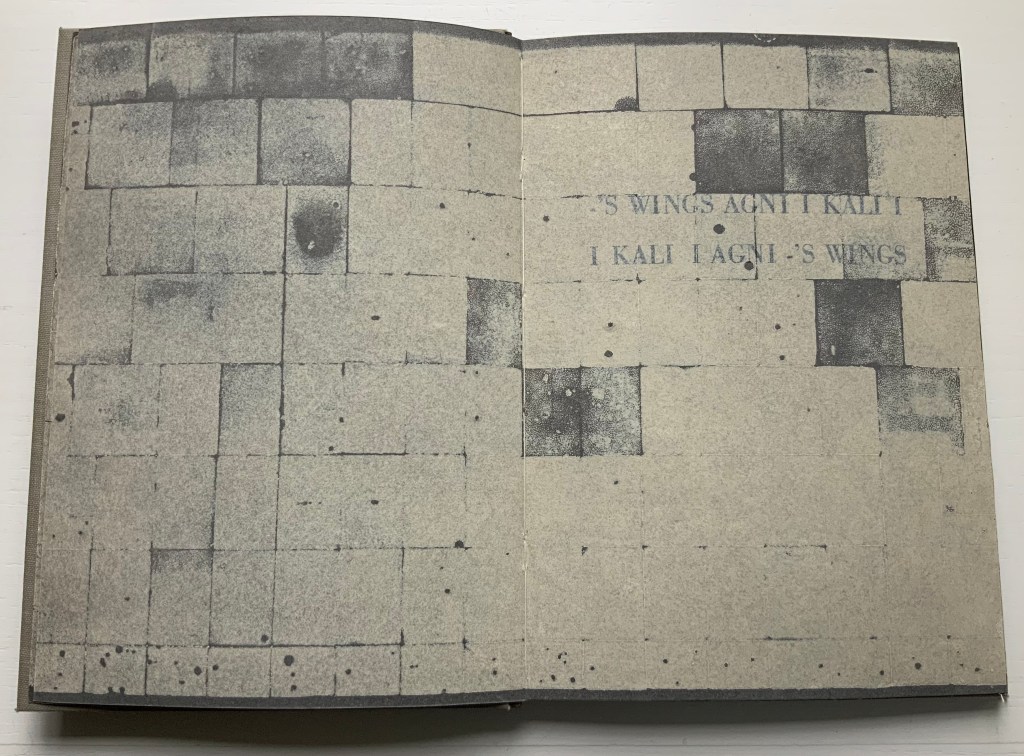

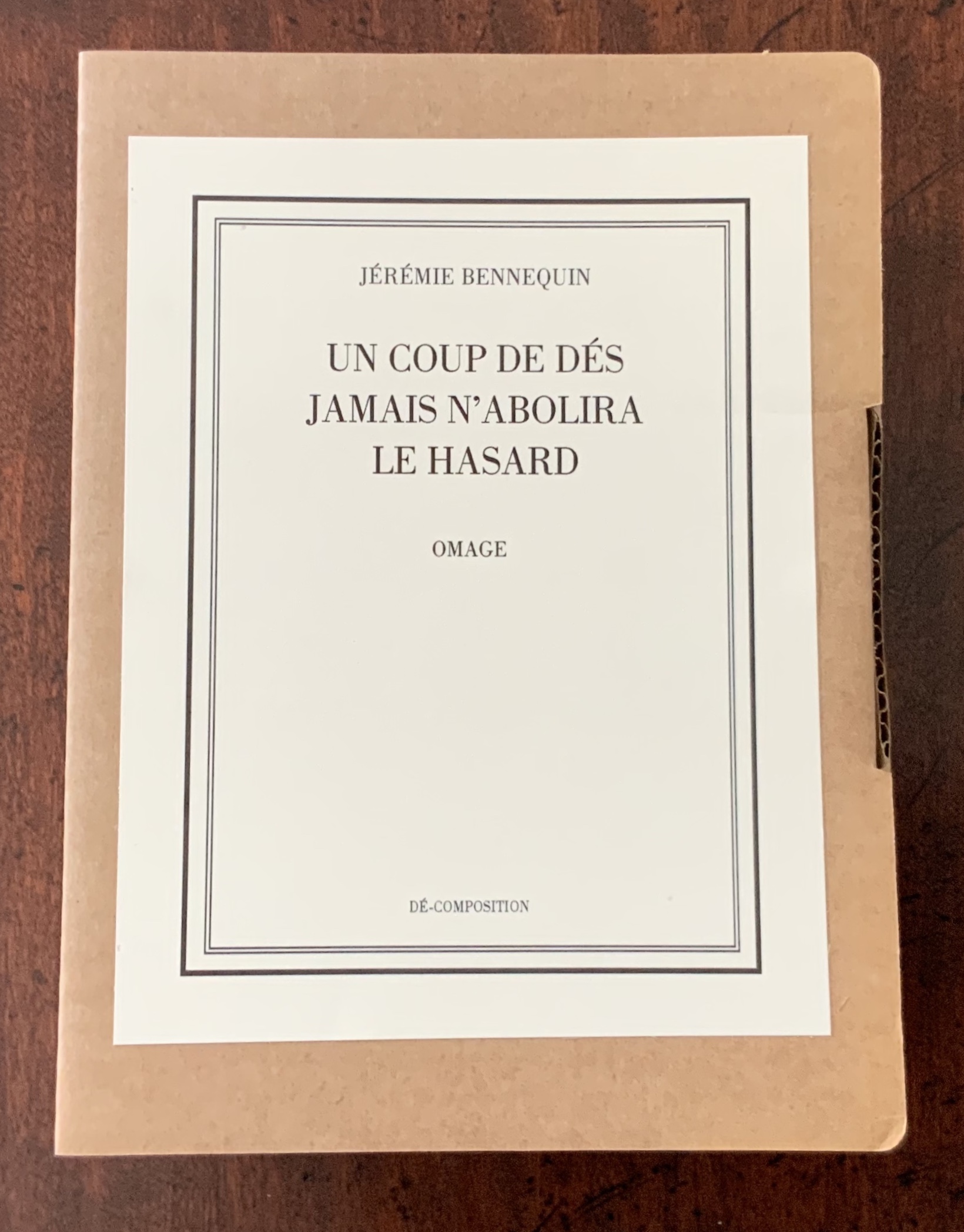

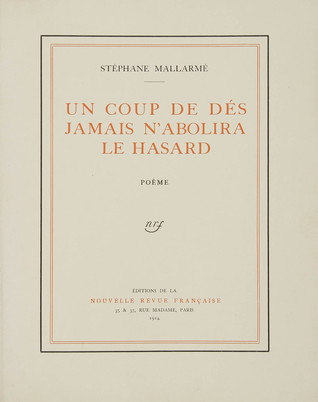

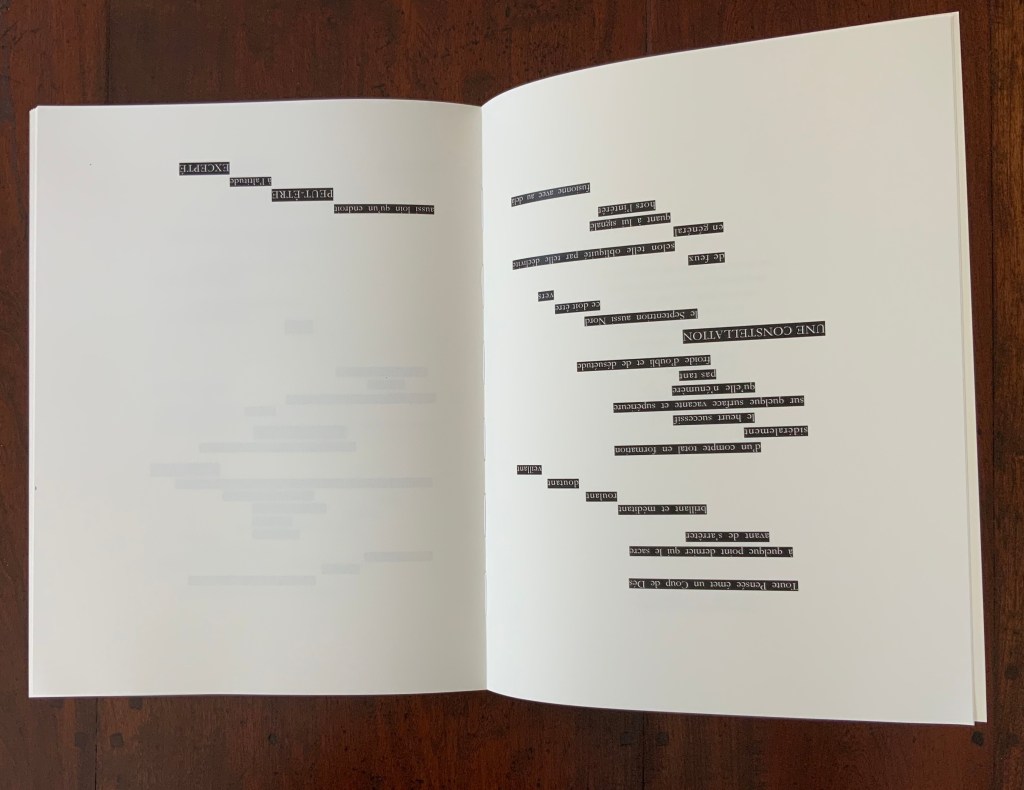

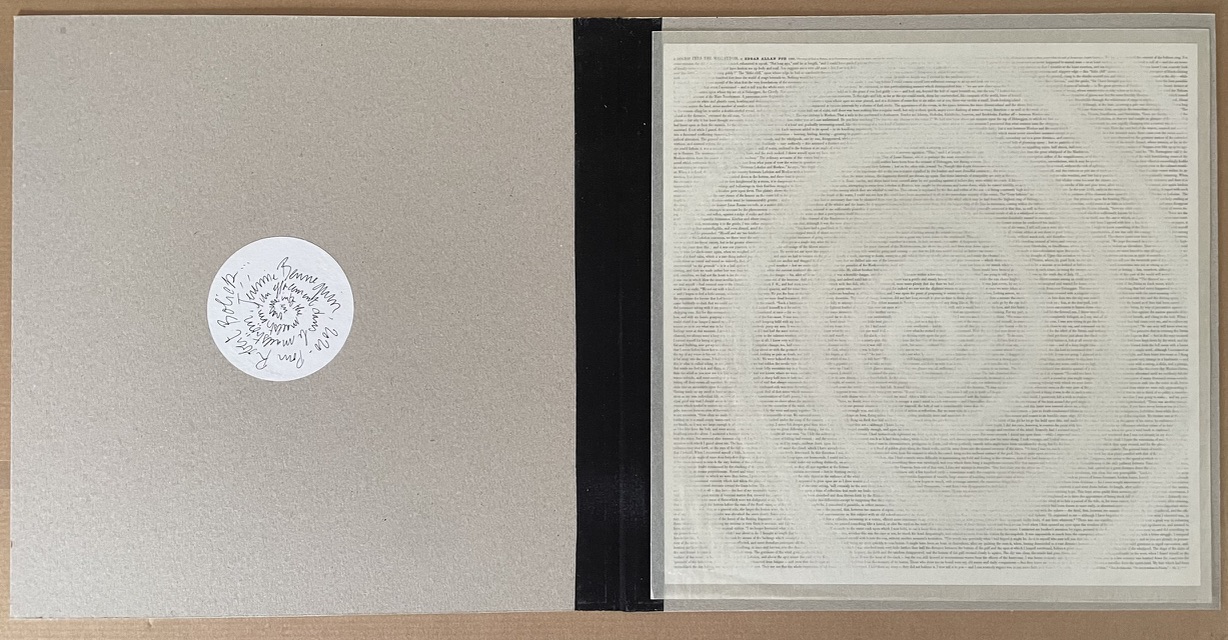

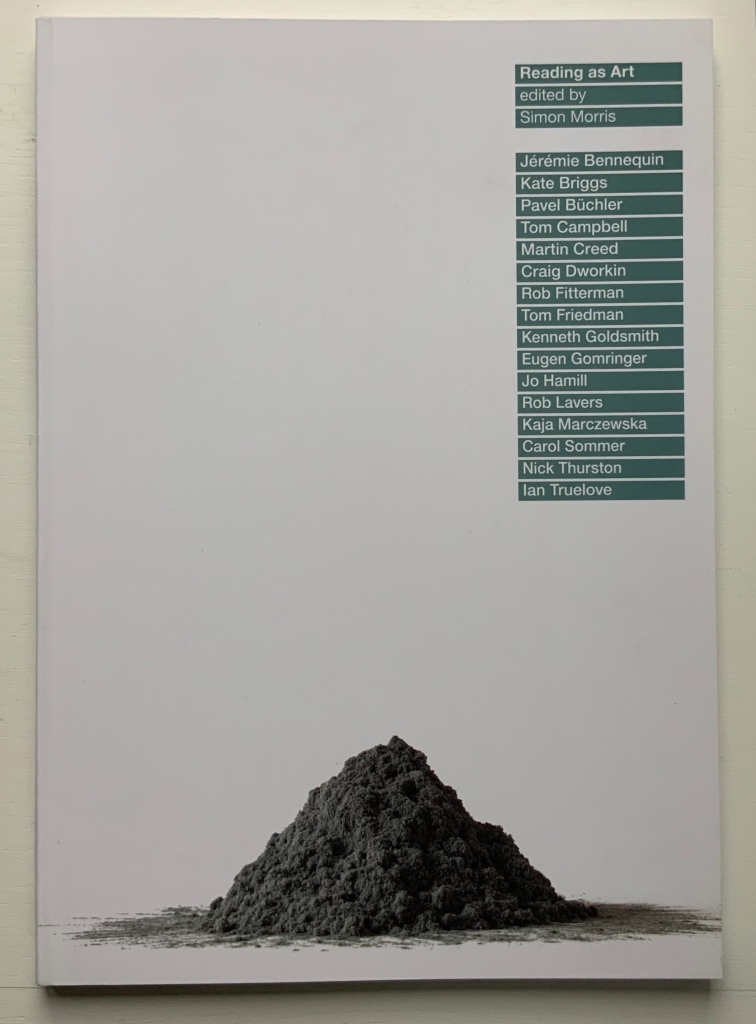

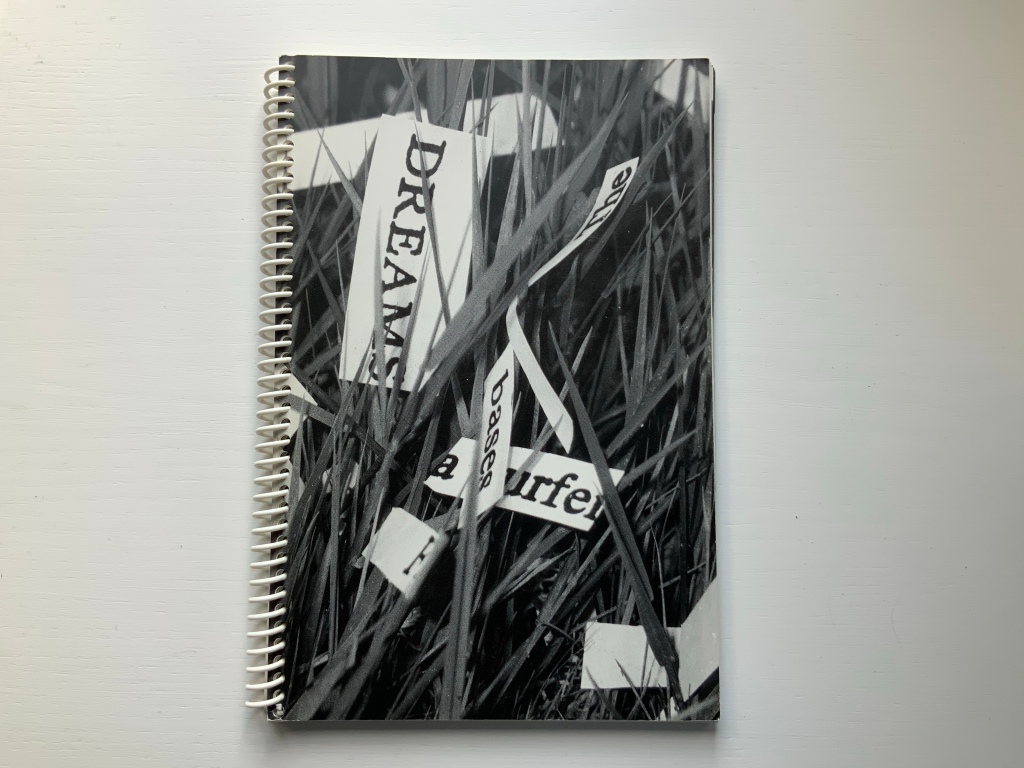

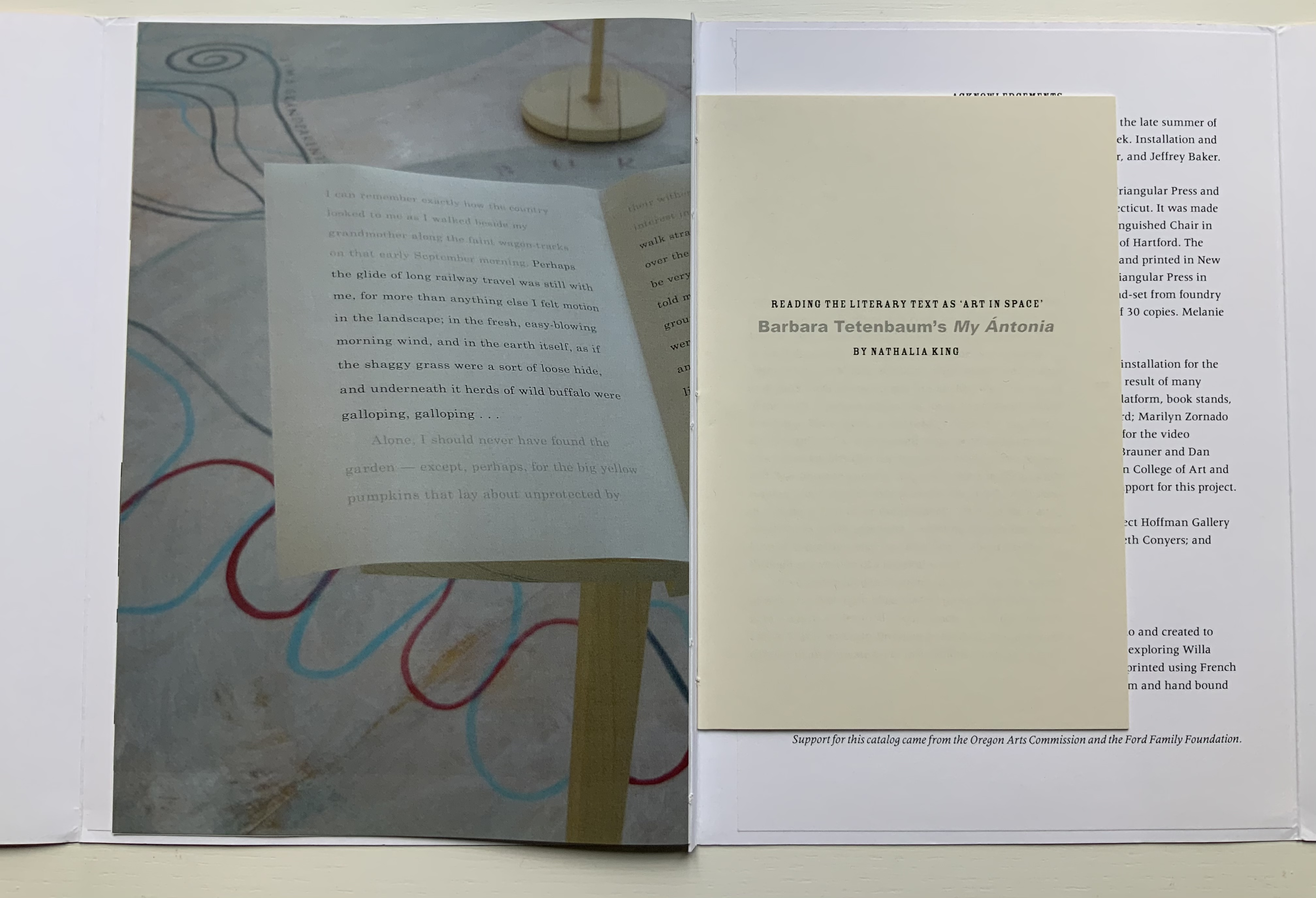

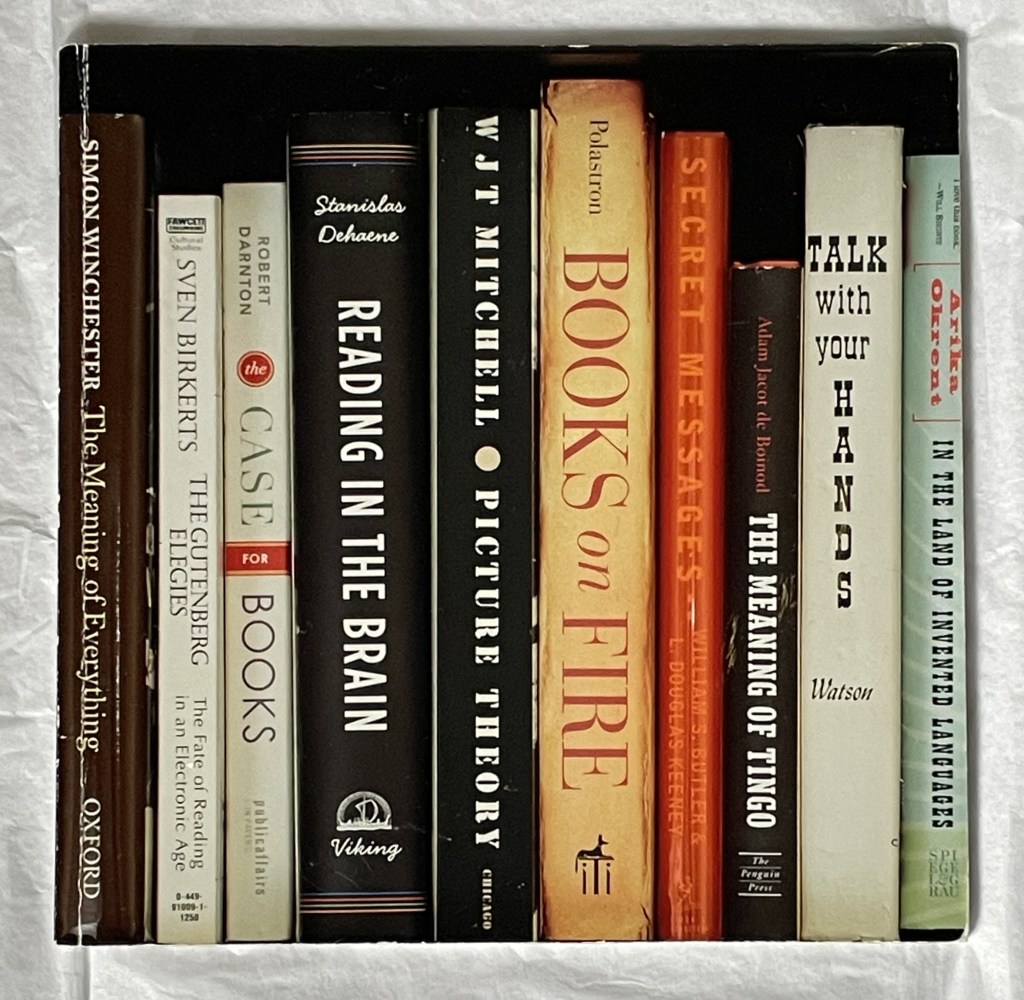

Image of map of My Ántonia reproduced in A Close Read: The Cather Projects (2012)

Barbara Tetenbaum and Jennifer Viviano

Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artist.

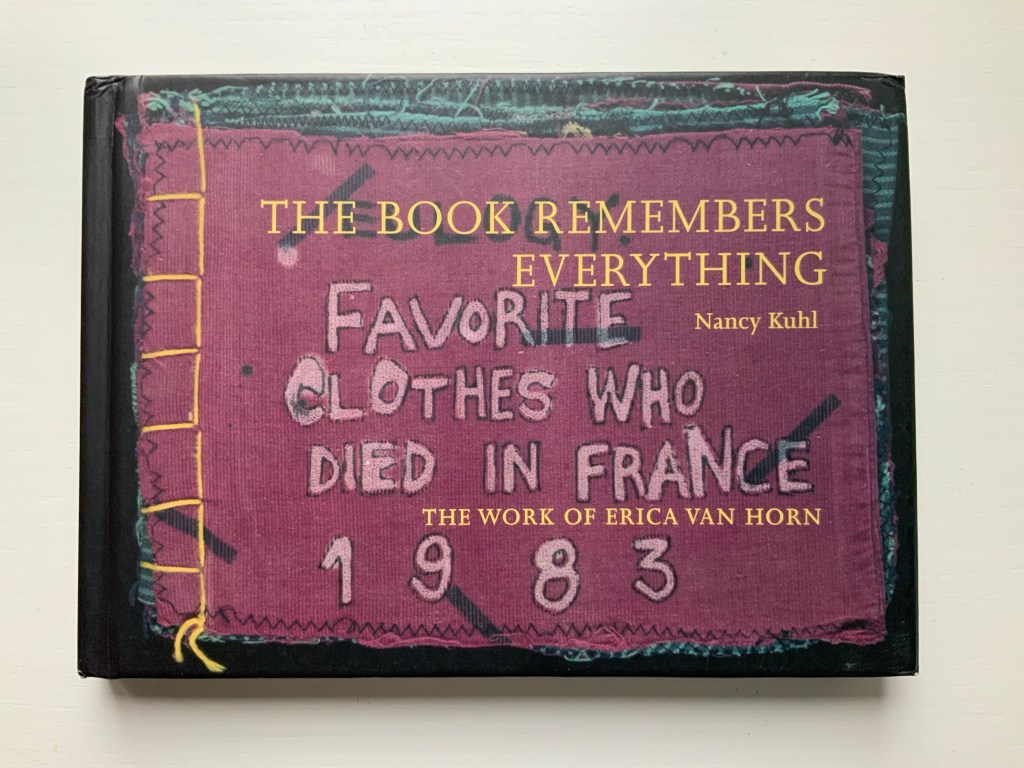

For the Books On Books Collection, Barbara Tetenbaum’s works have offered a map for exploring the different ways that text, image, structure and material bring about enjoyment and meaning in book art and bookmaking. Broadsides, chapbooks, a codex, a sculpture and, yes, a map have joined the collection over time.

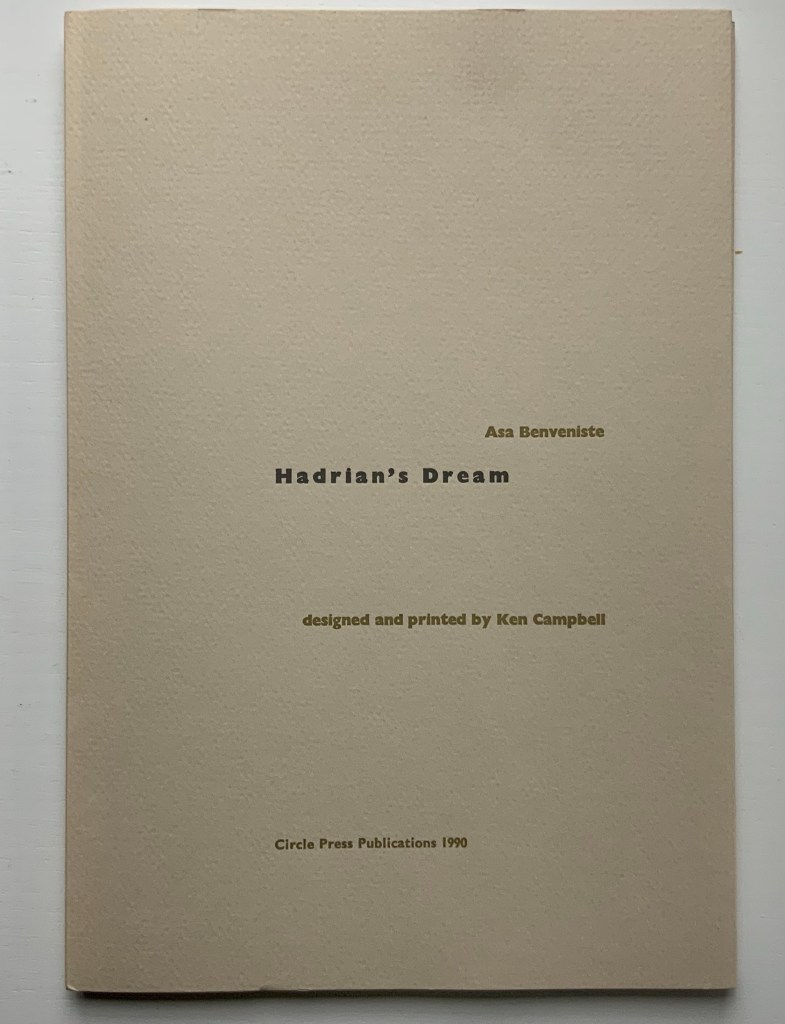

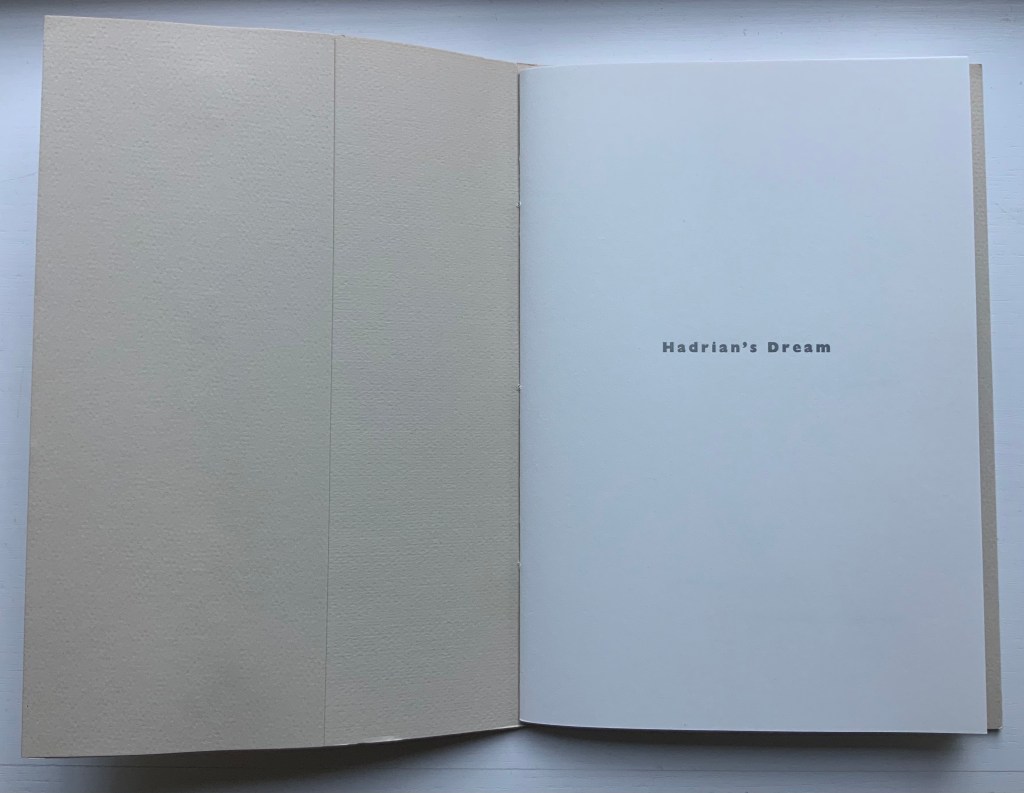

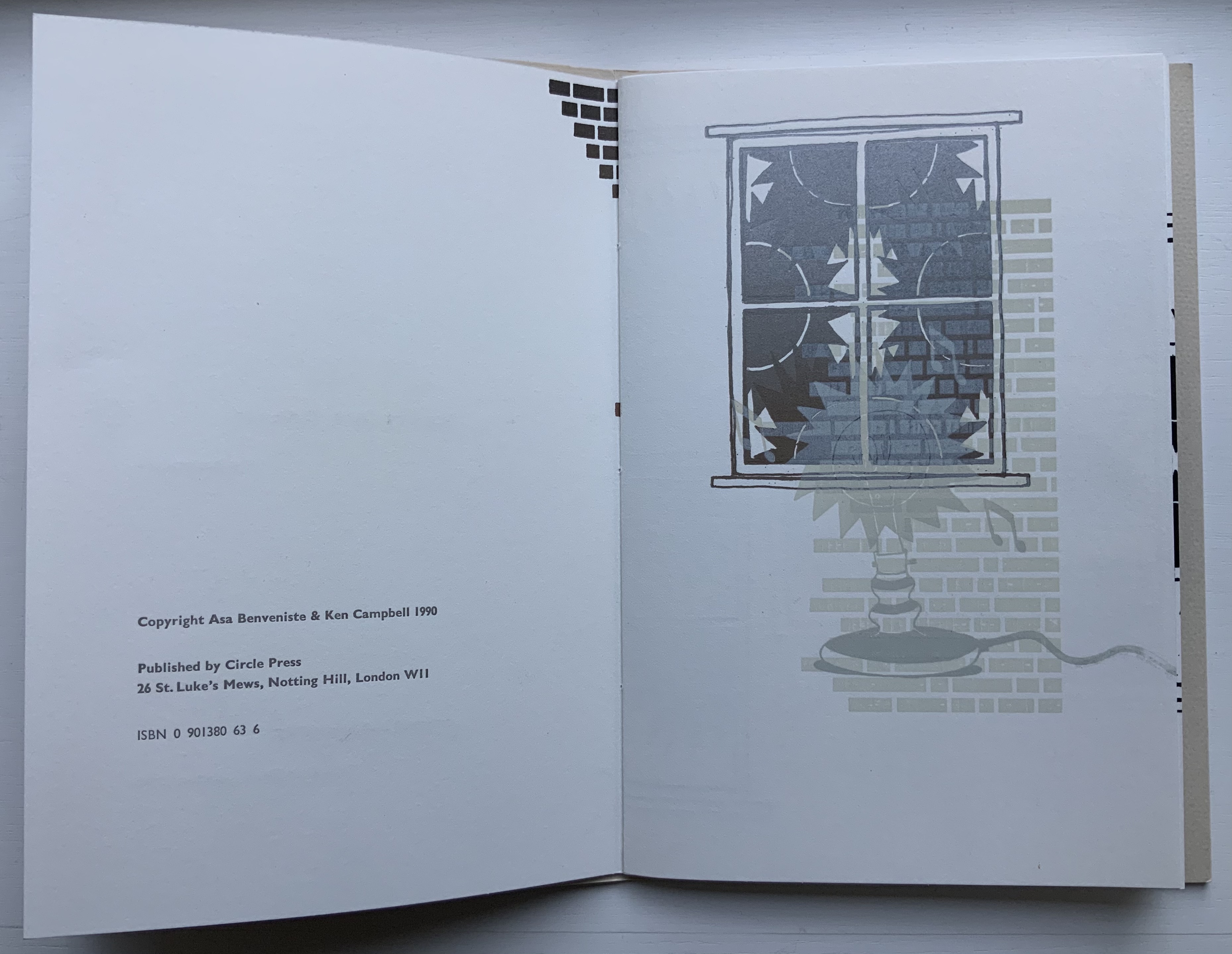

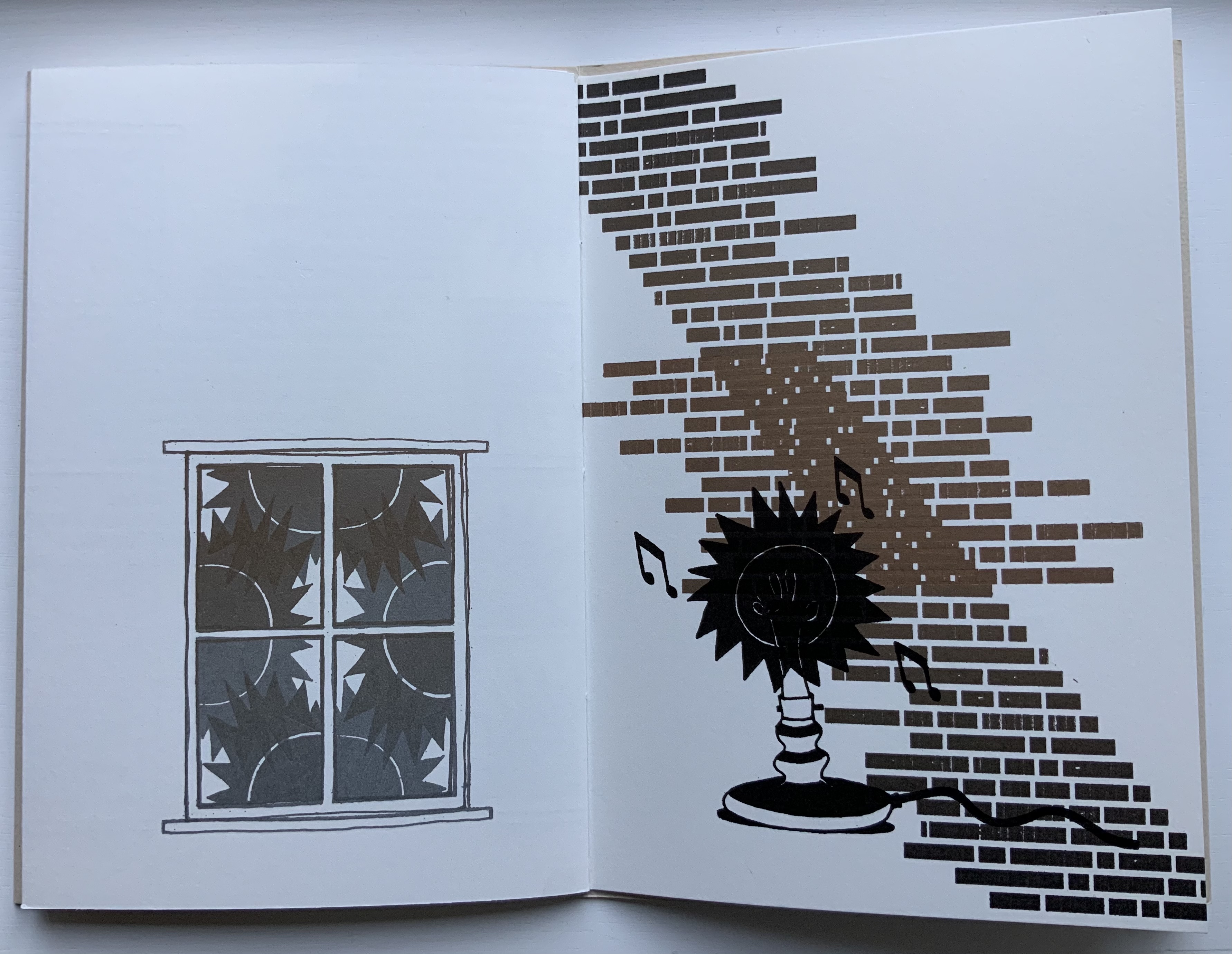

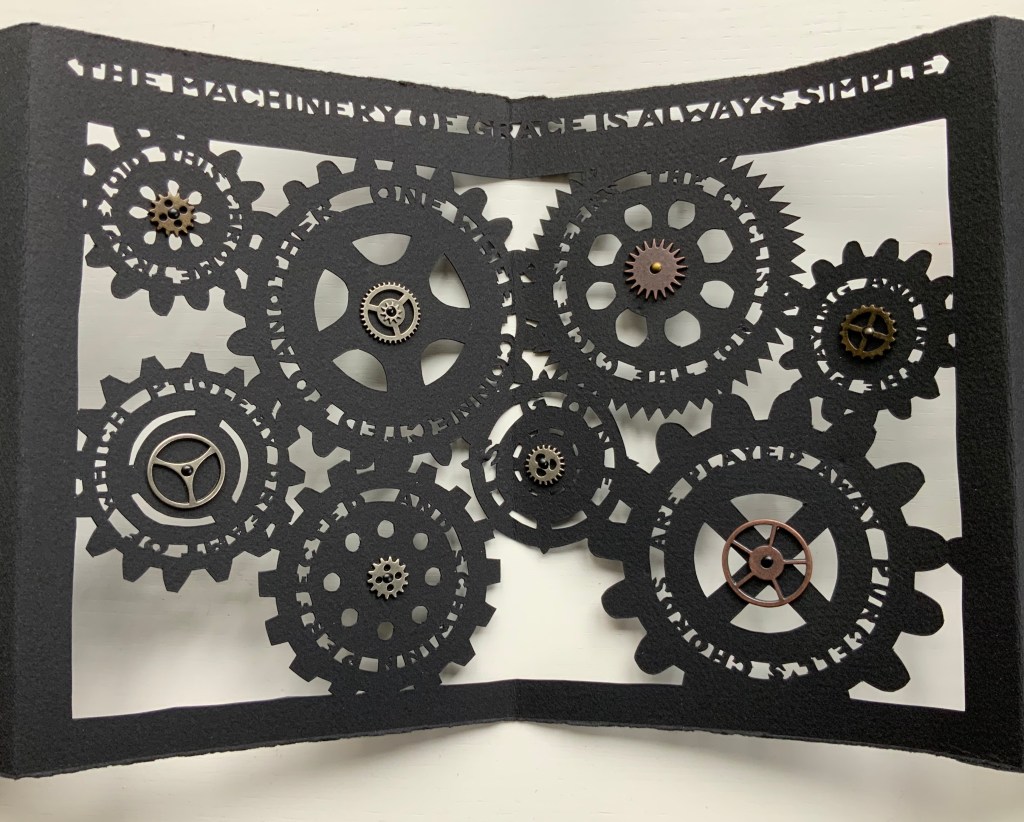

The broadside and chapbook forms seem to be both a rite of passage and a pastime of pleasure for book artists. For Tetenbaum, it has been both of these and a rite of remembrance of friendship. During Tetenbaum’s time at Circle Press, founded and run by UK artist Ron King, she reconnected with Chicago friends poet Michael Donaghy and his wife Maddy Paxman, who had moved earlier to London. Understandably taken with his poetry, she chose his “Machines” when King offered her the chance to set and print anything she liked while King and his wife were away on vacation.

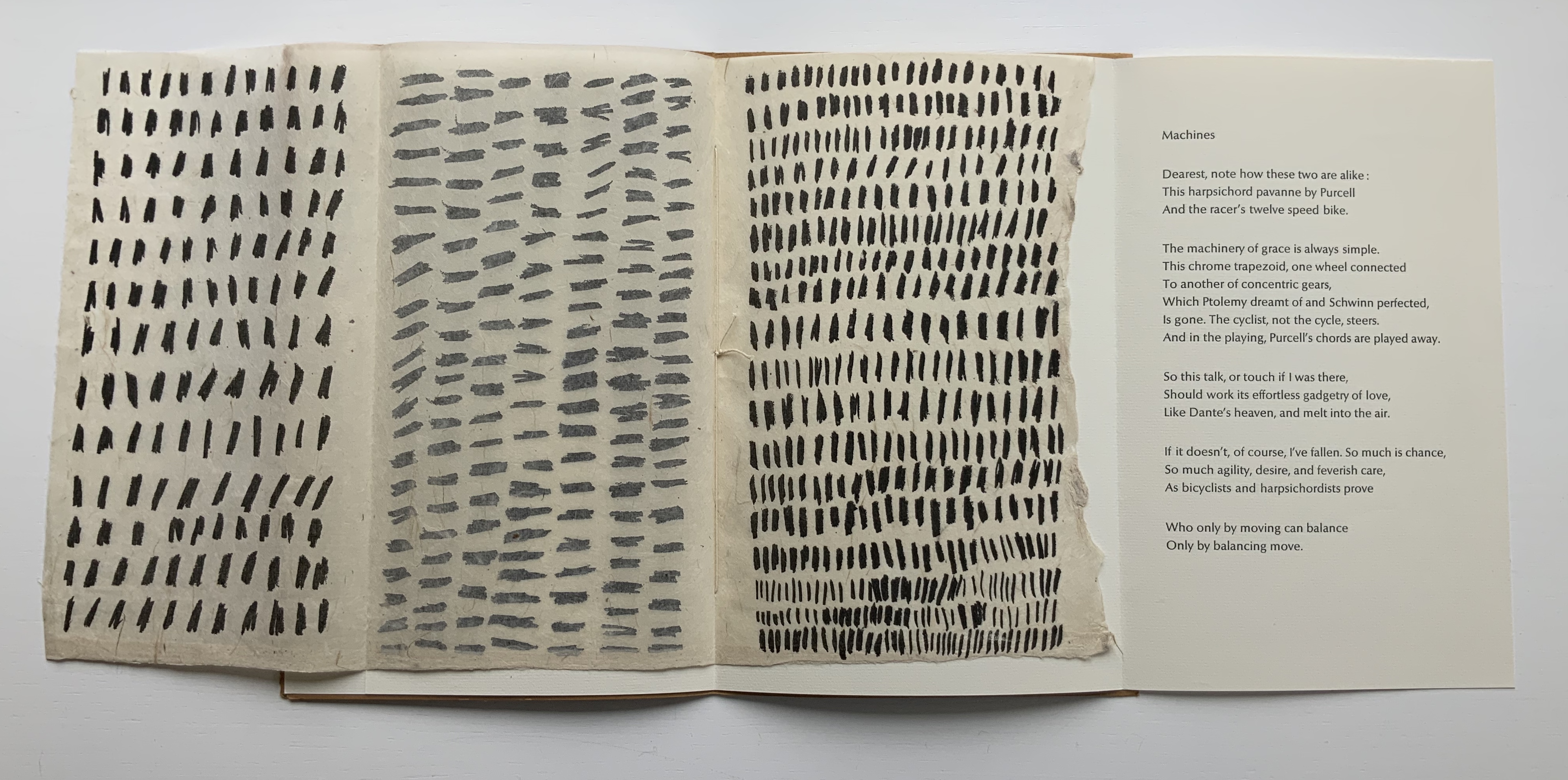

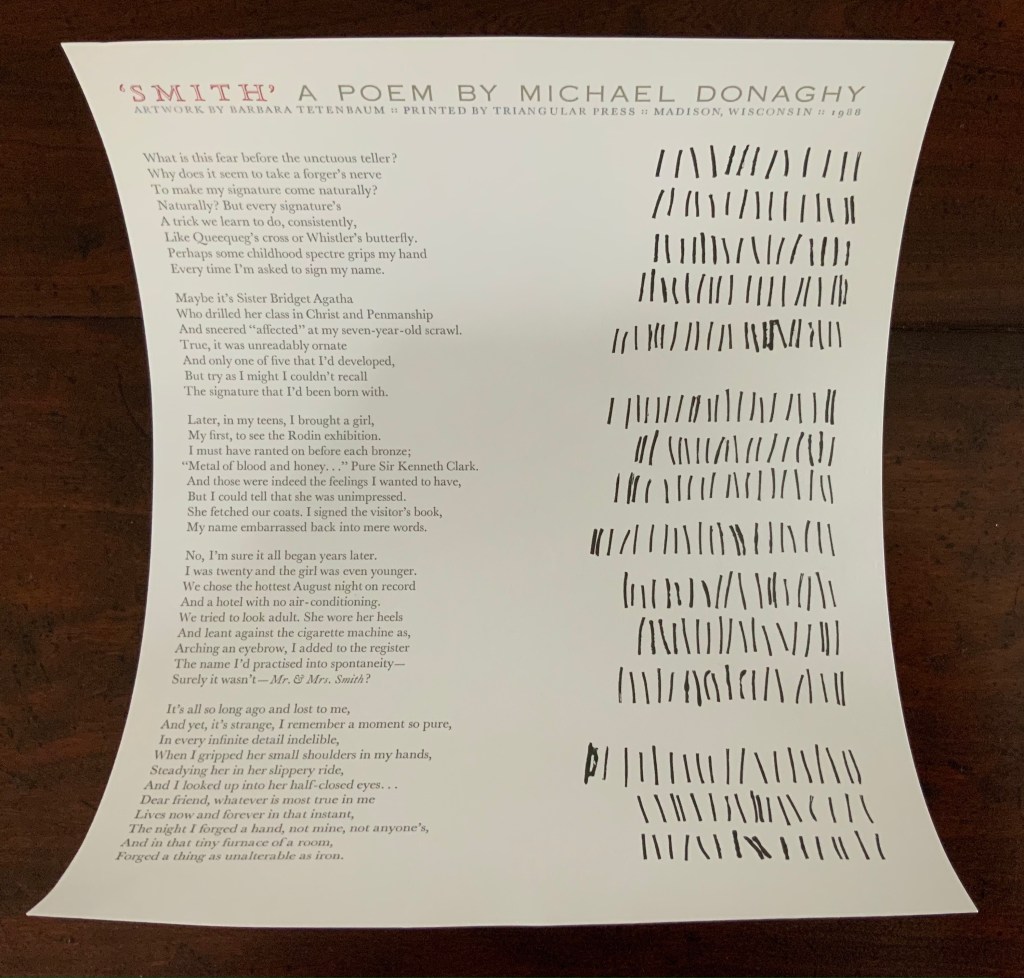

The earliest of Tetenbaum’s work in this collection, the chapbook Machines (1986) pairs Donaghy’s neo-metaphysical poem with the asemic markings that Tetenbaum had begun to pursue as a technique in 1985. Taken on their own, the markings do not call to mind any particular image or metaphor in the poem. Considered more closely as a physical response to the poem, though, they do share in the poem’s building rhythm and density (see further commentary here).

Machines: A Poem by Michael Donaghy with Artwork by Barbara Tetenbaum (1986)

Designed and printed by Barbara Tetenbaum at Circle Press, Guildford. Handset 14 pt Optima printed on rag paper, artwork printed on Himalayan mitsumata paper. Edition of 75, of which this is #72. Acquired from Circle Press, 22 June 2015. Photos: Books On Books Collection. With permission of Maddy Paxman and the artist. “Machines” © Michael Donaghy Estate.

Back in the US, the artist continued with the marks and Donaghy’s words. The broadside below was the result. This time, technique, form and subject cannot avoid similarity — like a reflection in a mirror. ‘Smith’ has a regularity but looseness often found in Donaghy’s poems, something essential to their charm. The iambic pentameter is not always iambic or ten-syllabled, and the length of stanzas vary. Flush right to Donaghy’s flush left, Tetenbaum’s lines of marking mirror the poem’s ragged right and variable counts — but not precisely.

‘Smith’ (1988)

Poem by Michael Donaghy, artwork and printing by Barbara Tetenbaum

Broadside. H333 xW268 mm. Unnumbered edition, signed on reverse. Acquired from the artist, 31 October 2020. Photo: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of Maddy Paxman and the artist. ‘Smith’ © Michael Donaghy Estate.

A love poem that takes off from the act of trying to remember forging a name in a hotel register for an assignation that forged something true and lasting, ‘Smith’ is about making one’s mark as artist and responding, intimately, one human to another. To transfer her marks made in response to the poem, Tetenbaum used

coated wire (bell wire) brought to type high on a piece of MDF covered in carpet tape to hold them in place. This is a technique I learned from Elmar Heimbach and used in a bit of the illustration in O’Ryan’s Belt. (Correspondence with artist, 21 November 2020. Link added.)

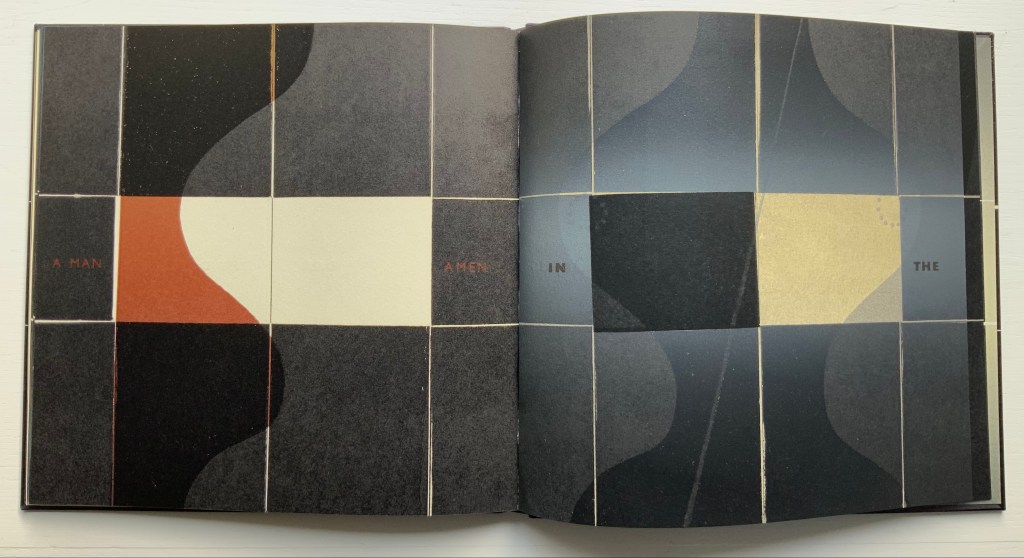

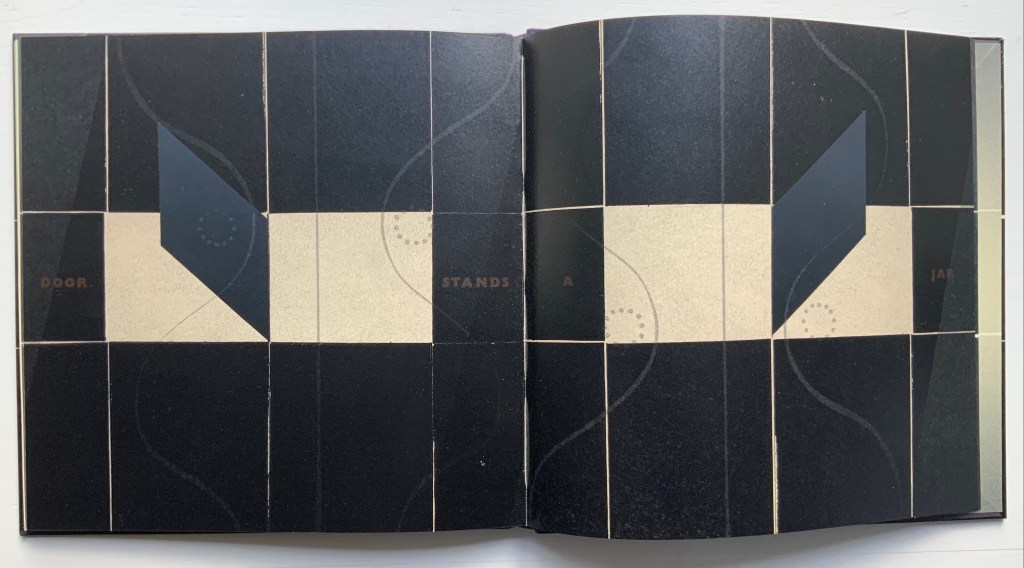

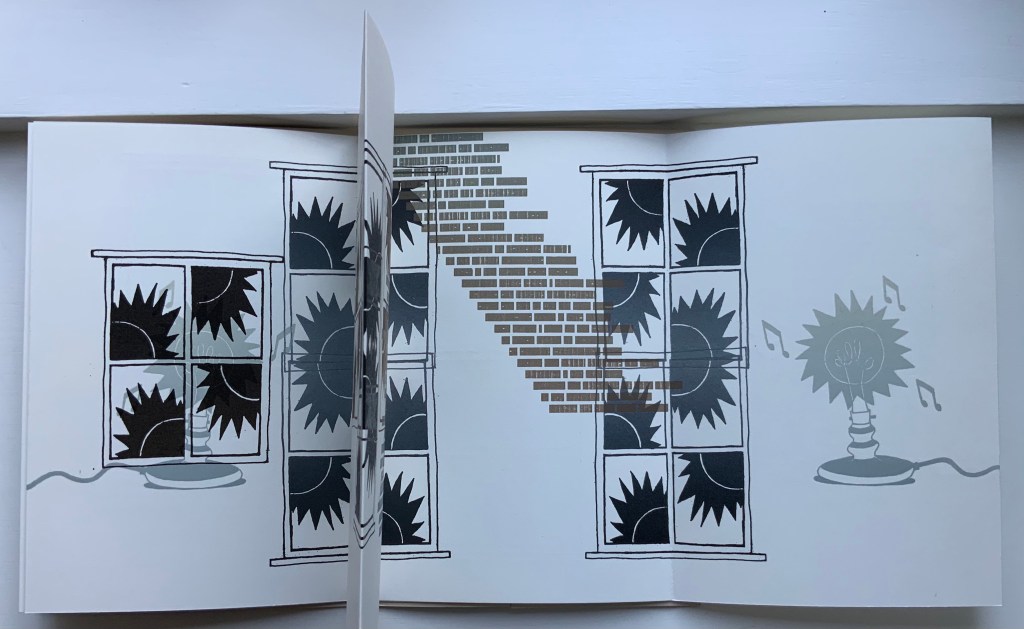

Another of Tetenbaum’s earliest chapbooks, Donaghy’s O’Ryan’s Belt (1991) foreshadows her move toward work that responds with a growing independent relationship to the text.

O’Ryan’s Belt: Eleven Poems: 1990-1991 by Michael Donaghy (1991)

Handbound book of poems produced by Barbara Tetenbaum at the Silver Buckle Press.

Structure designed by Marta Gomez; handbound by Tracy Honn; typography, setting and artwork by Barbara Tetenbaum. Acquired 1 October 2020. Edition of 70, of which this is #31. Photos: Books On Books Collection. With permission of Maddy Paxman and the artist. O’Ryan’s Belt © Michael Donaghy Estate.

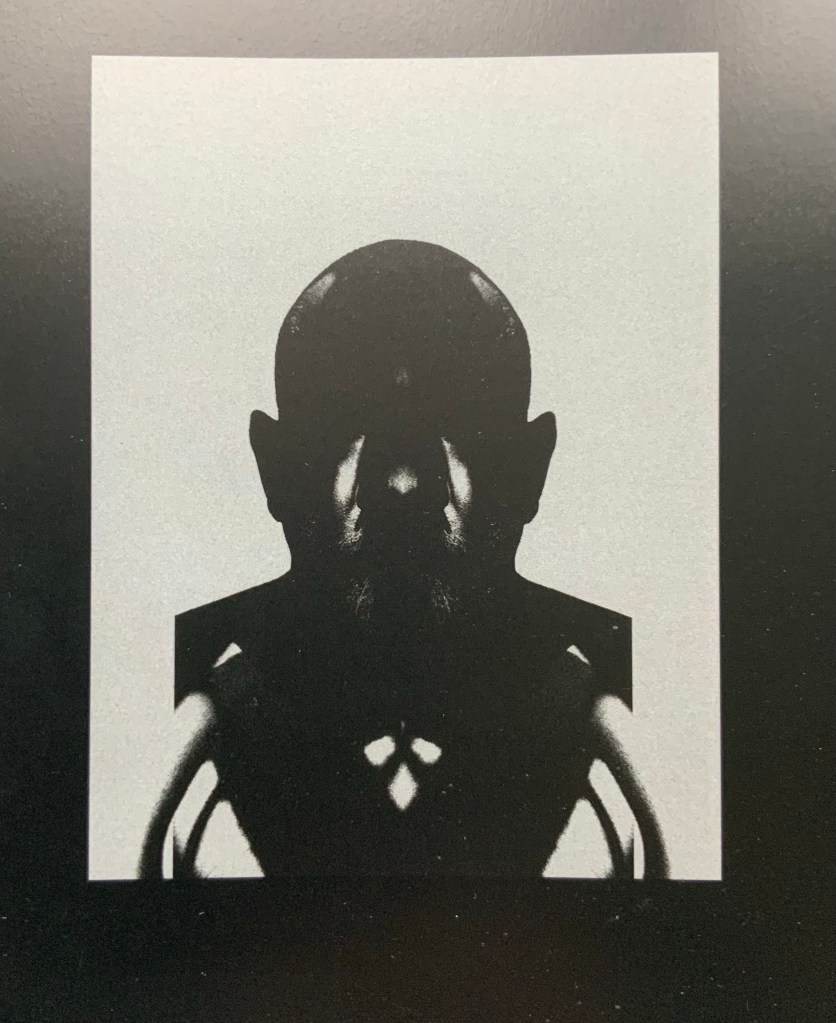

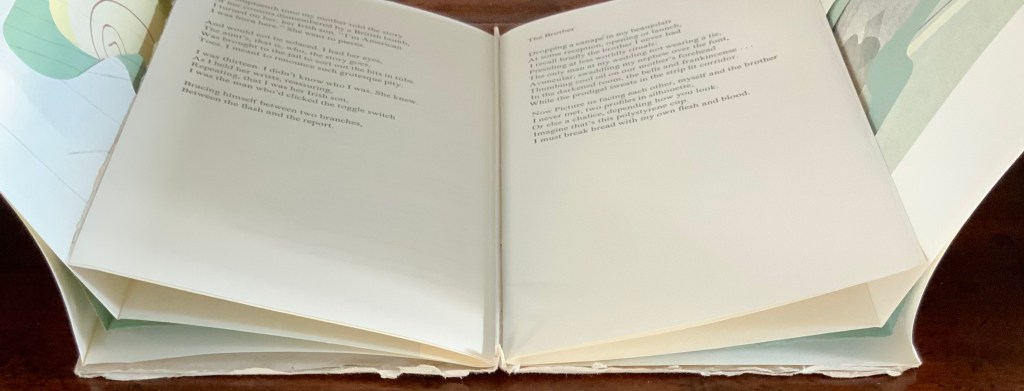

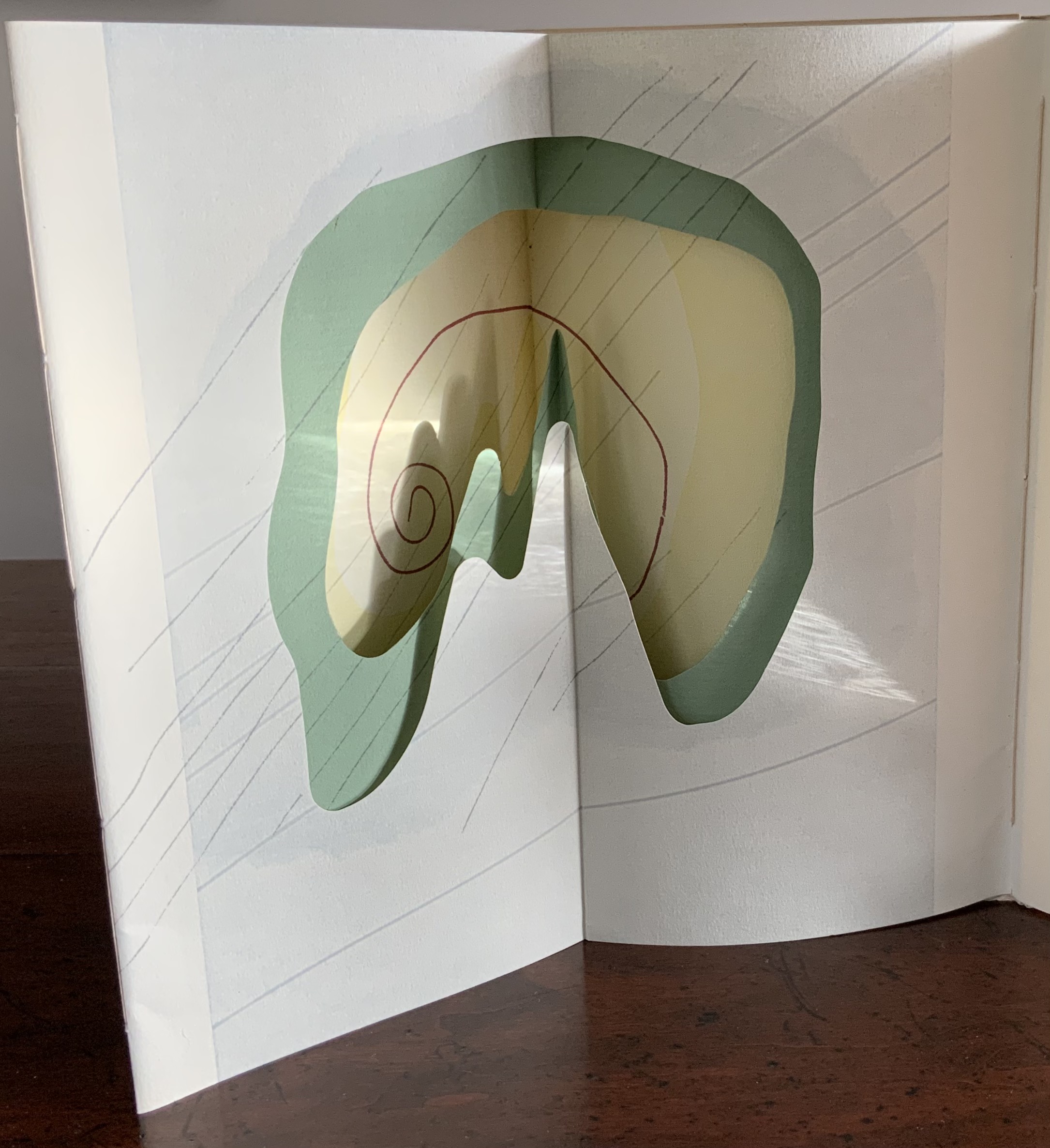

The spine of O’Ryan’s Belt consists of a small fold. Inside, on either side of it, is a gathering of folios. The two sets of folios are sewn (belted?) together through the small fold. Each set includes a tunnel-book-like artwork of three layers. The first sits adjacent to the poem “A Spectacle”, and the second, to “The Hunter’s Purse”, a line from which the chapbook takes its name.

View of the “internal spine”, an inward fold of the cover creating a tab to which signatures on either side are sewn.

View of the tunnel-book image adjacent to “A Spectacle”

The colophon explains that stencils, string and other found objects were used to print the illustrations. Note how the artworks’ lines cross the pages but not into the space of their adjacent poems. It’s as if the artwork is asserting a claim — this is a part of, but apart from; or this is apart from, but a part of. The images created by the artwork seem more related to “A Spectacle” than “The Hunter’s Purse”. Both artworks capture the idea of the image started by the lines “The shape of man, a shadow on the ground,/ Returns a mirror image from pondwater.” As the poem proceeds, we see through the shadow/mirror image to the objects and gravel at the bottom of the pool. Hinting at stalactites or stalagmites as well as the layers reflected on and beneath the water, the first paper sculpture makes sure we recognize the poet’s shadow boxing here with Plato’s cave.

So snugly fitted to the structure, the artwork seems to be waiting to surprise the reader.

The broadside Co-Pilot extends this structurally interpretive technique. The poem “Co Pilot” (no hyphen in the original) hilariously turns the speaker’s conscience into a parrot on his shoulder, “a tiny Charlton Heston” squawking the Ten Commandments. But there is no parrot, no Charlton Heston, no Ten Commandments in the broadside’s artwork beneath the typeset poem.

Co-Pilot (March 2002)

Poem by Michael Donaghy, art and printing by Barbara Tetenbaum.

Broadside H500 x W233 mm. Edition of 35, which this is an artist’s proof. Acquired from the artist, 31 October 2020. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of Maddy Paxman and the artist. “Co Pilot” © Michael Donaghy Estate.

There is, however, an eye peeking from four holes scattered among bubble-like transparent circles printed over a collage of images and texts from newspapers, health and housekeeping guides (from the Fifties?), history books, clothing ads and prayer cards. Are the eyes the conscience in bubbles beneath the surface of a clear punch bowl? Are those images the compromised and socially mundane background noise of the party?

The collage comes from a large photoengraved block, originally made for a tiny book, Collage Book #3 (see below). This may explain the viewer’s urge to turn the broadside upside down to examine the image: it’s an imposition of the unfolded, uncut pages of that book (correspondence with the artist, 21 November 2020).

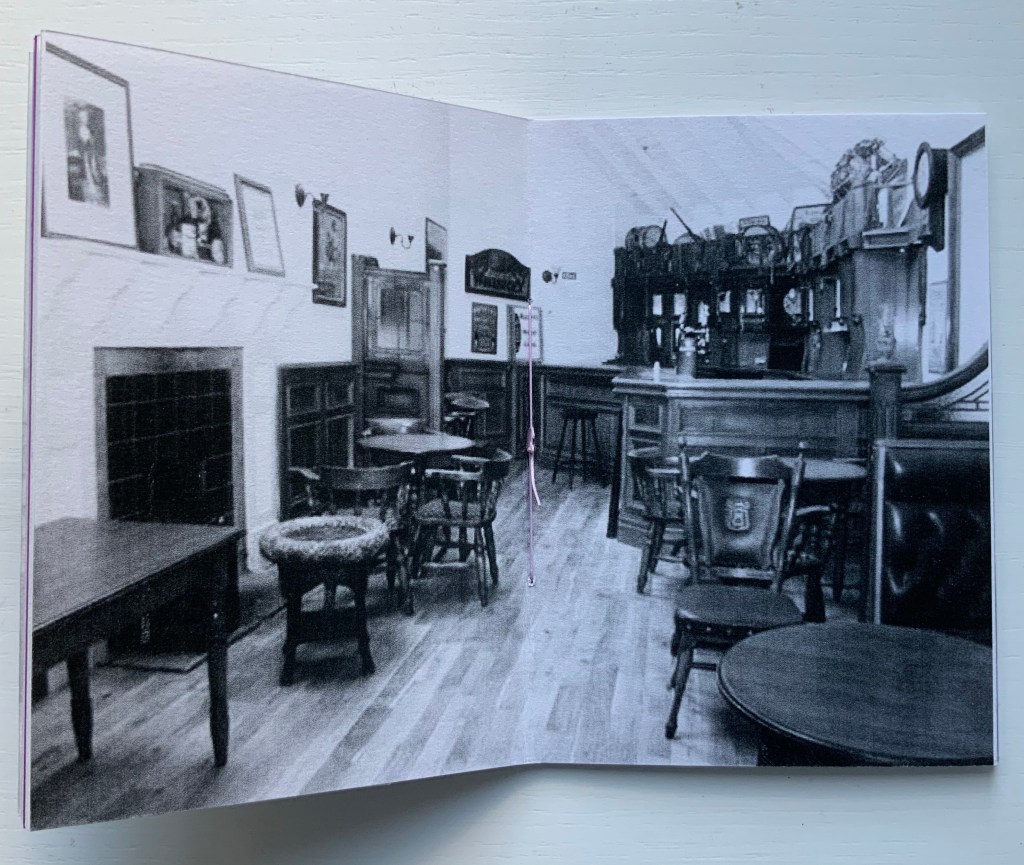

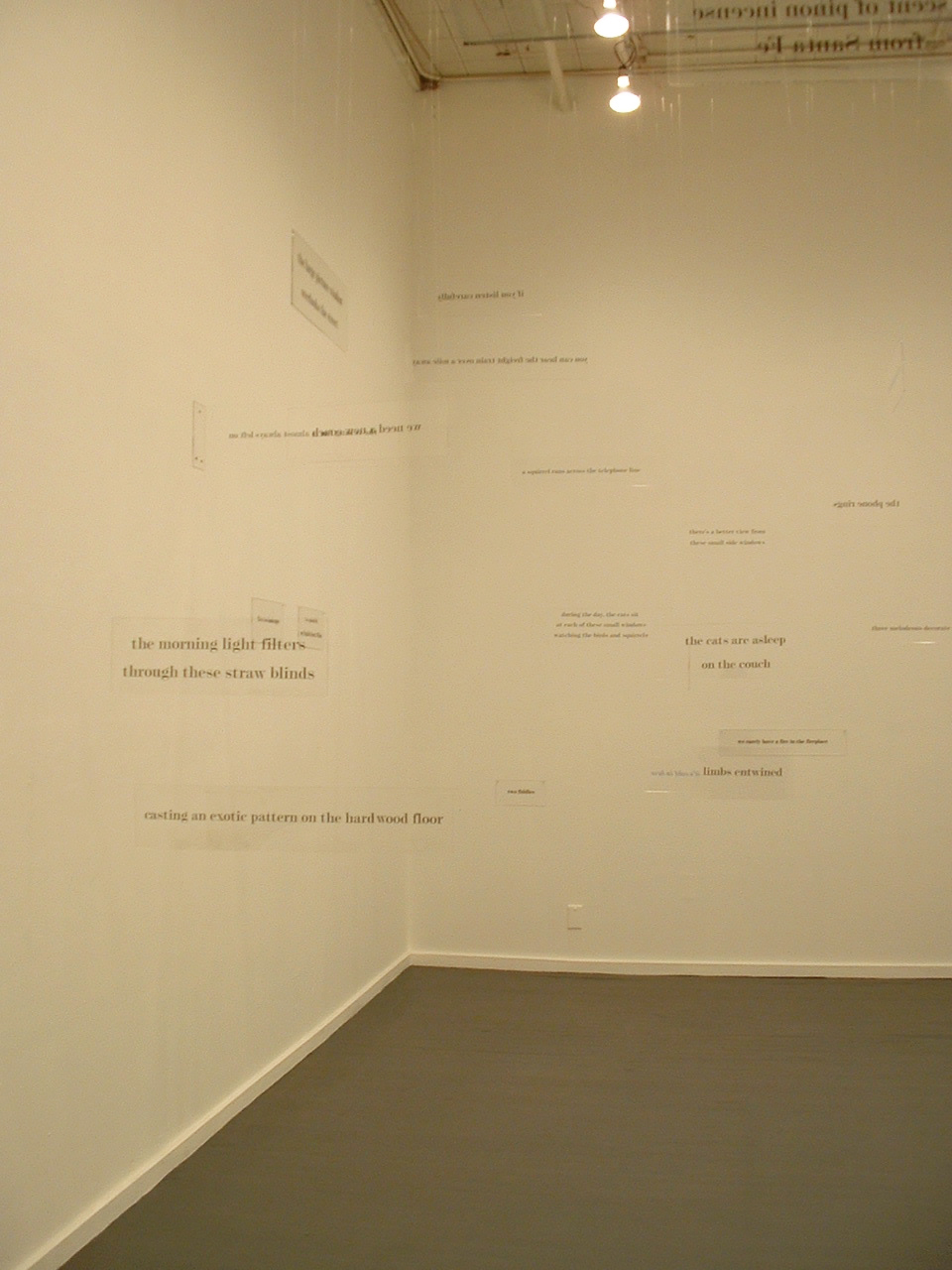

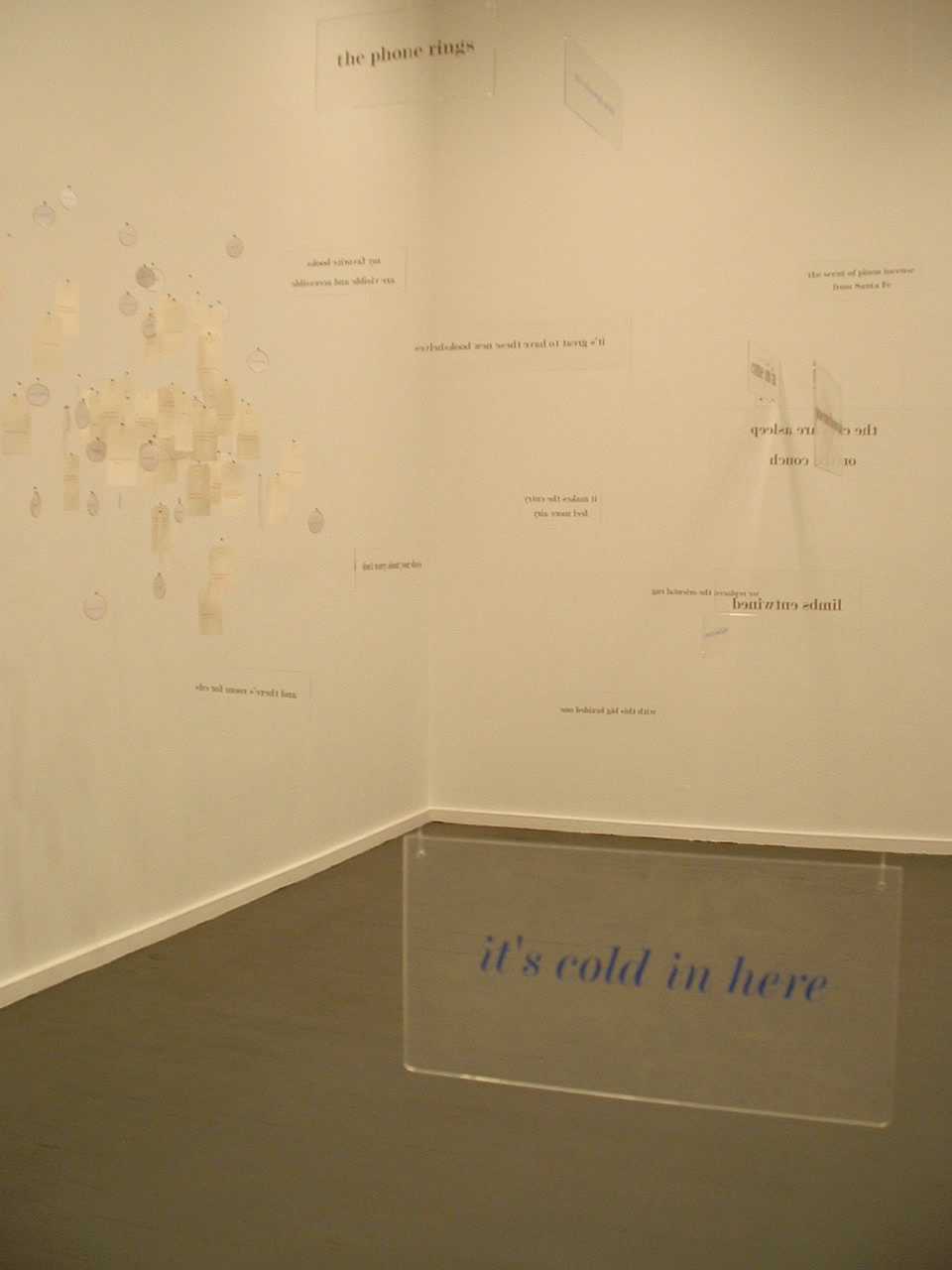

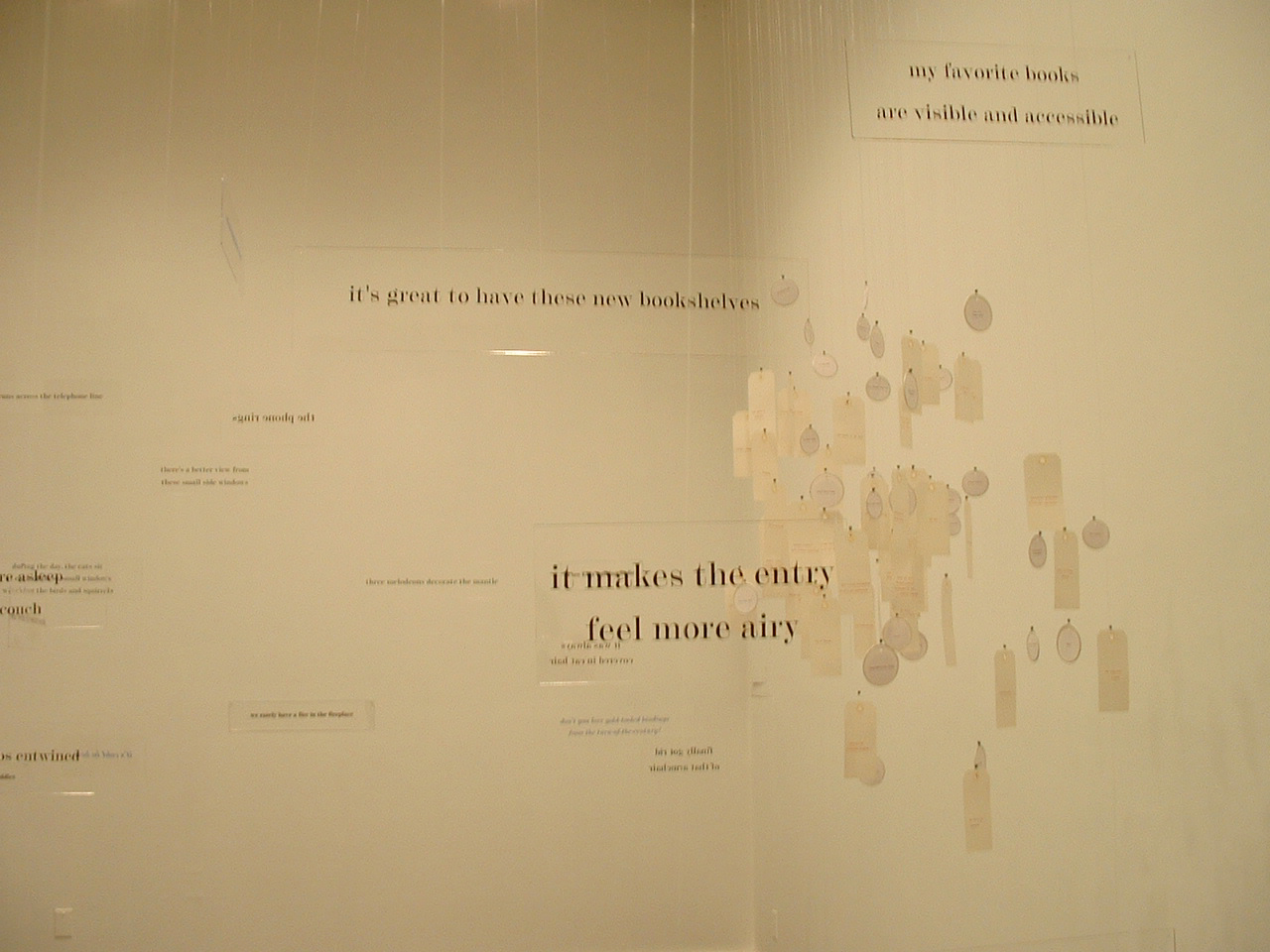

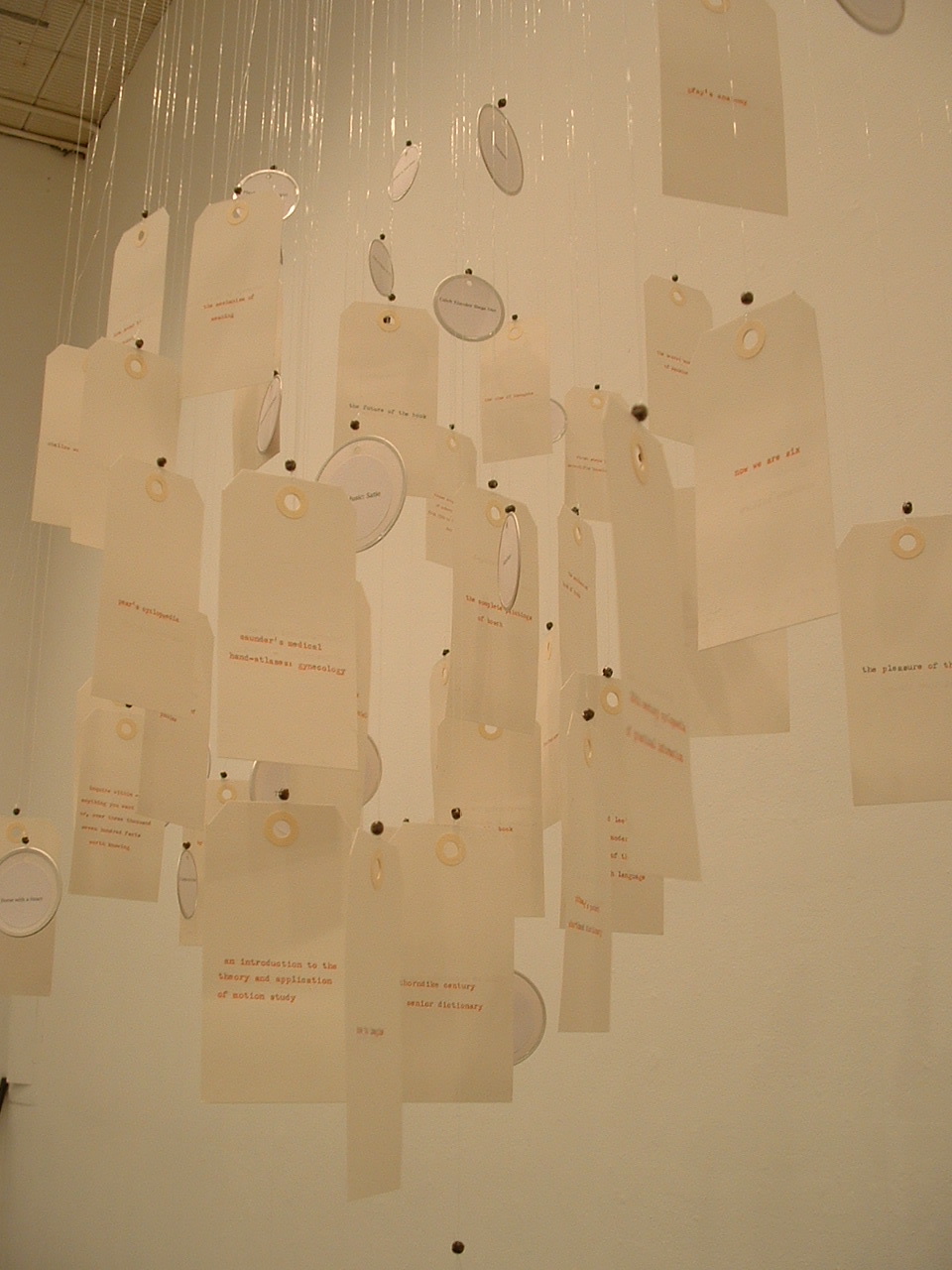

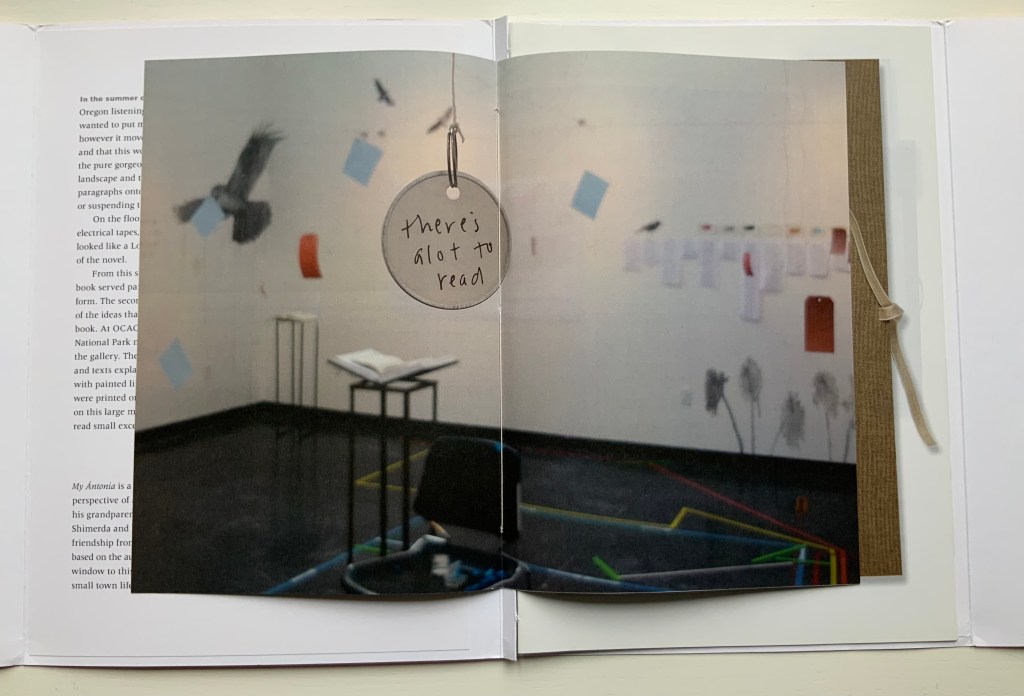

Not strictly a work in the collection, the installation The Reading Room (2002) should be mentioned here — not merely because it occurred the same year as Co-Pilot but also because it is a reminder of a constant theme and a harbinger of other installations to come. Thin slabs of plexiglas bearing text in black serif type hang at angles to one another from clear fishing line. The words, phrases and sentences suspended in air are drawn from a short story composed by Tetenbaum; they are what make The Reading Room a room for reading. That’s almost all there is to do in it. If, as Anthony Powell’s character Lindsay Bagshaw says, “Books do furnish a room”, Tetenbaum’s installation proves, “Words do furnish a room”. What reading is, can or might be is that constant theme in the artist’s works — whether evoked by asemic markings, a walk through the words of a story, a “map of reading” or a “diagram of wind”.

The Reading Room (2002)

Barbara Tetenbaum

Installation at Nine Gallery, Portland, OR, December 2002. Photos: Courtesy of the artist.

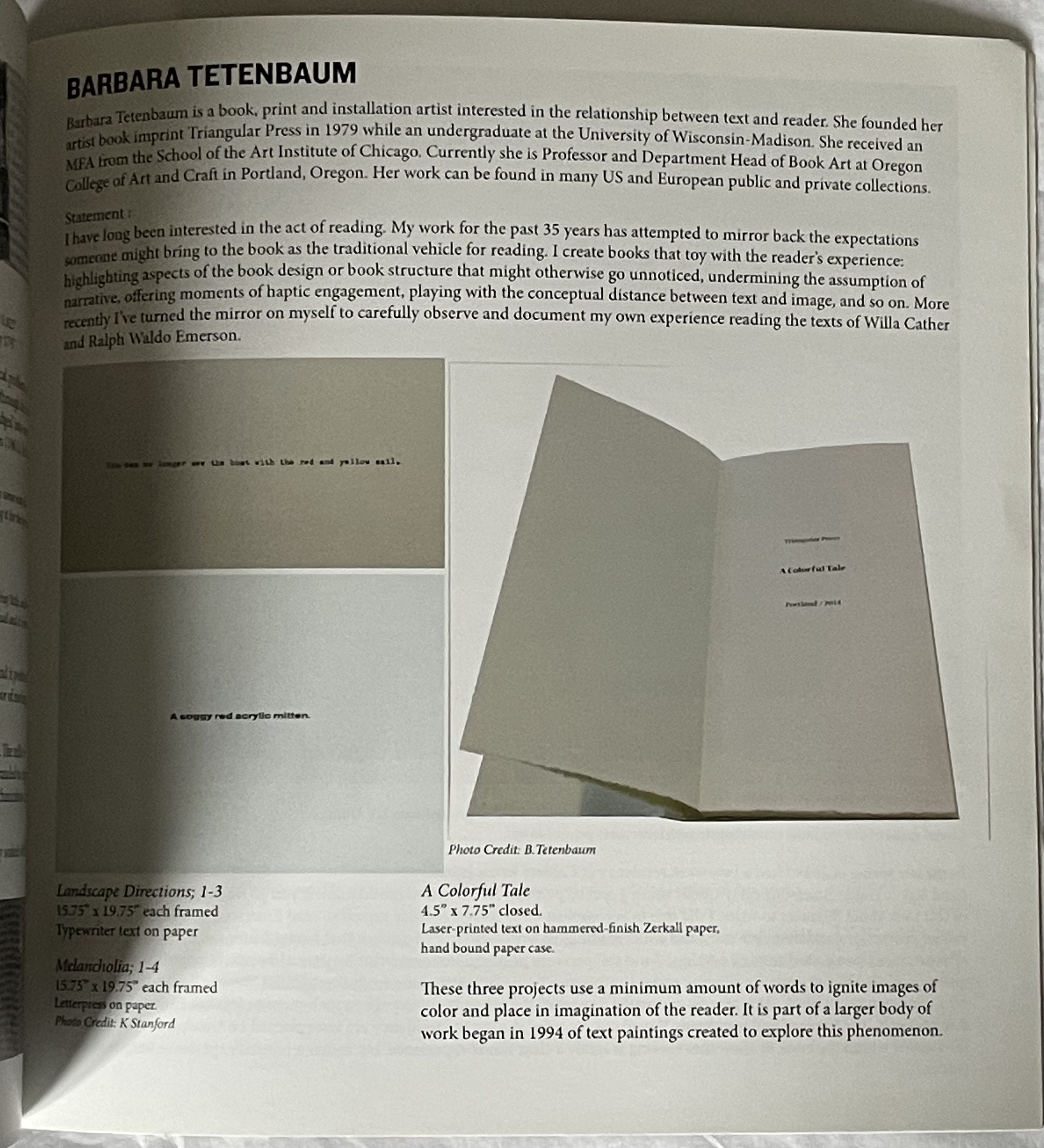

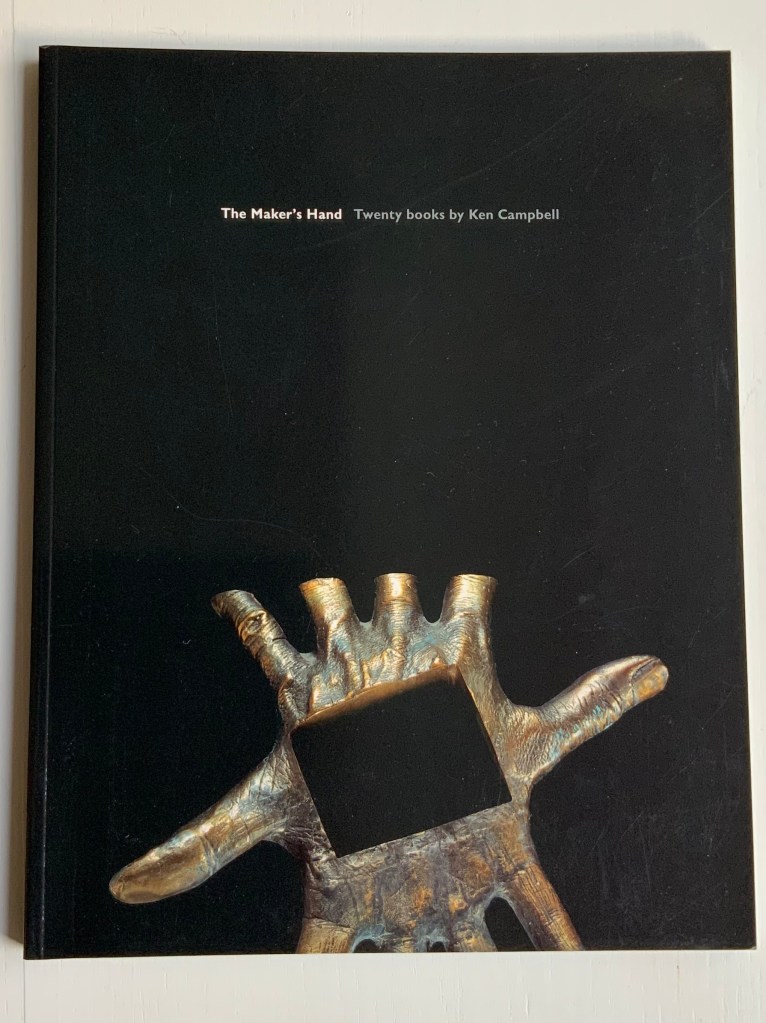

Half-Life: 25 years of books by Barbara Tetenbaum & Triangular Press (2005)

Barbara Tetenbaum

Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with artist’s permission.

Half-Life (2005) is the collection’s representative codex by Tetenbaum. A catalogue raisonné for works between 1978 and 2005, with a chronology of the artist’s life and an appreciation of her work from Uta Schneider, the book reveals several of the influences on Tetenbaum’s development, including Ron King (as noted above) and Walter Hamady (evident particularly in the Co-Pilot broadside). Tetenbaum is generous in her collaborations and acknowledgments. Although closer to a fine press edition than anything produced by Dick Higgins, Half-Life notes in its colophon the influence of his FOEW&OMBWHNW (New York: Something Else Press, 1969).

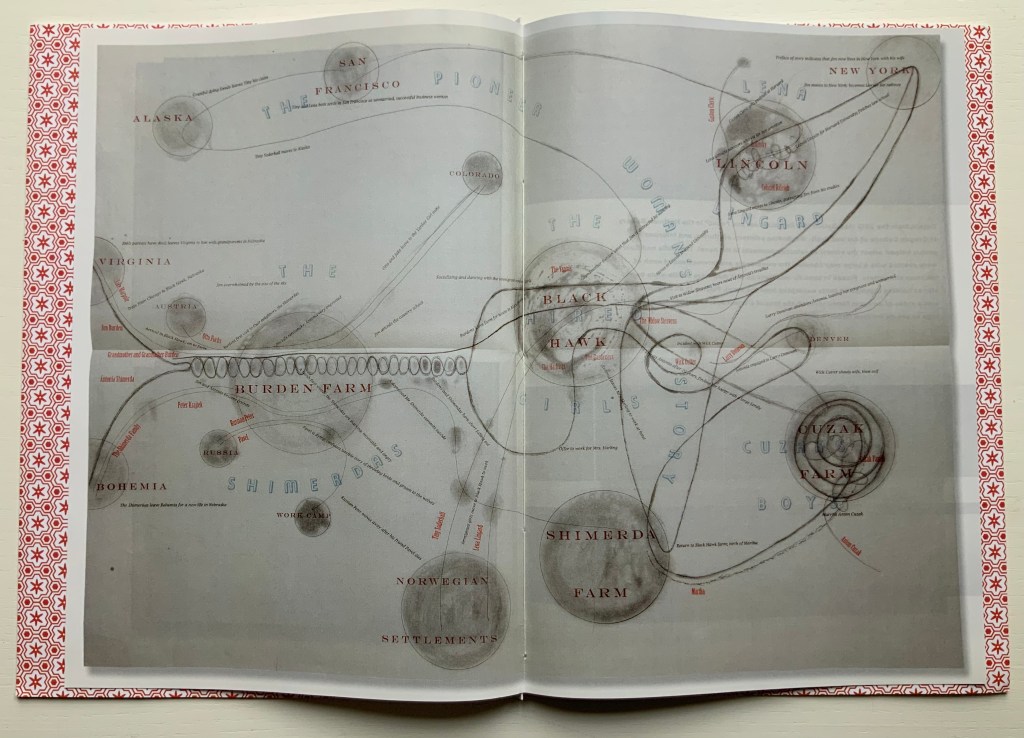

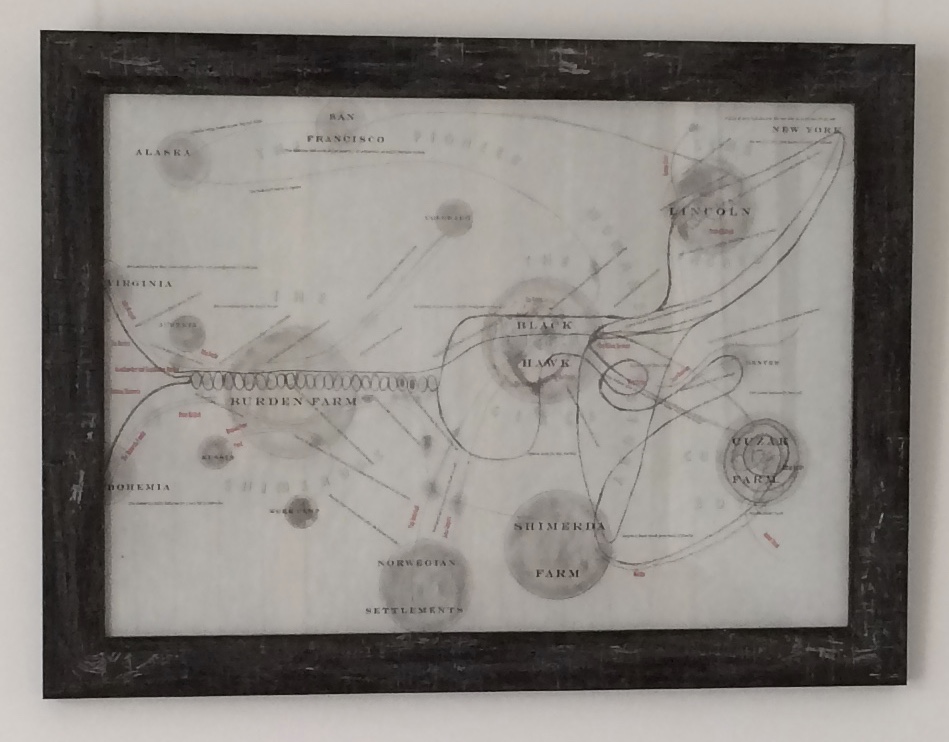

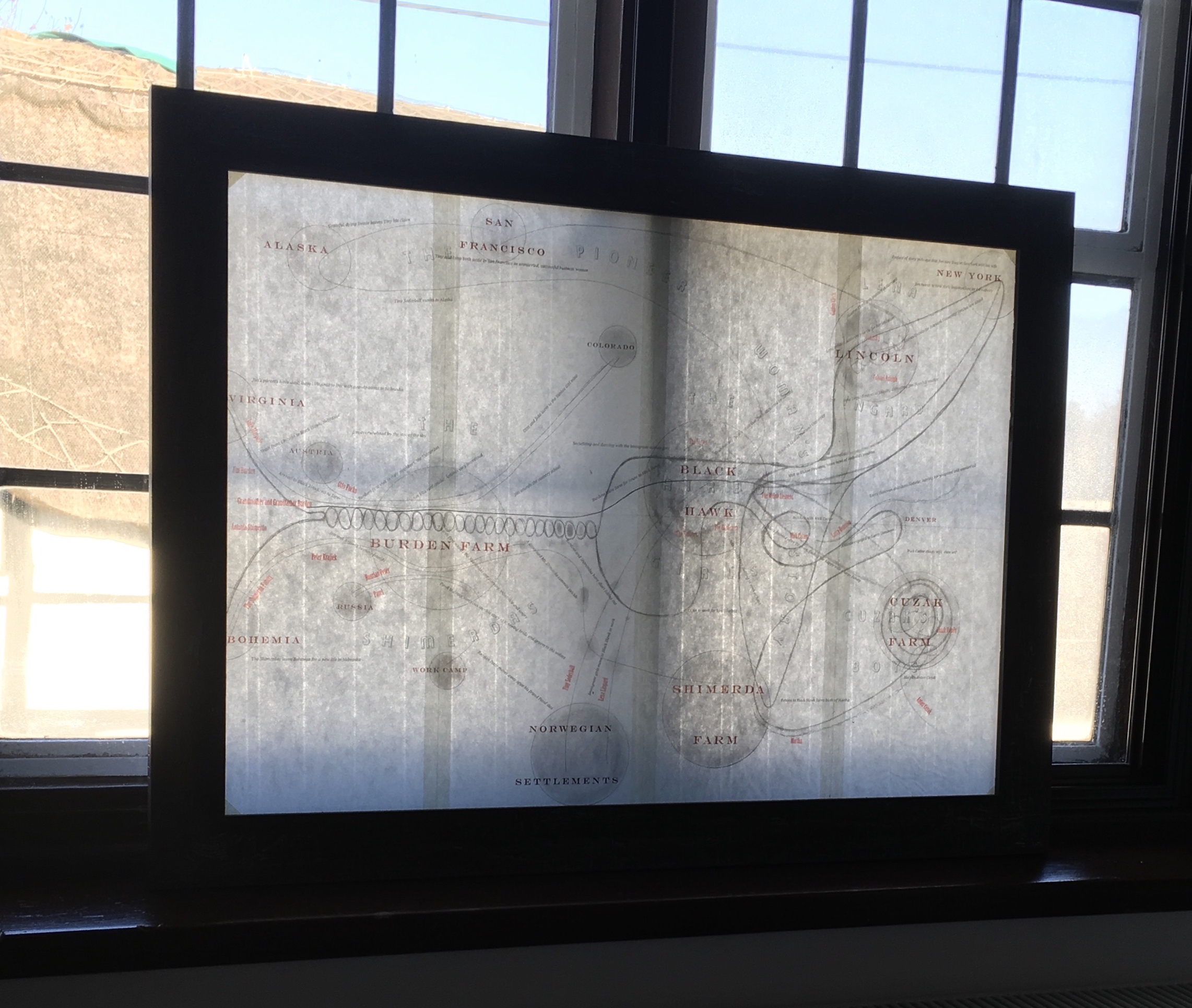

For a body of work realized after Half-Life, Tetenbaum spent a month in a gallery listening to a recording of Willa Cather’s 1918 novel, My Ántonia. The result was two installations and two publications: a catalogue called A Close Read: My Ántonia (2010) and an “artist’s book” or “bookwork” called Mining My Ántonia: Excerpts, Drawings, and a Map (2012). The collection currently includes only the map and the catalogue. Some work in this category of “response to literary material” can be primarily craftwork — as in those well-known narrative scenes sculpted from the pages of the book in question. Other responses to books — including altered books — stand as works of art yielding depths of meaning and aesthetic response on their own.

Of course, the antecedent to this in literature is called ekphrasis. W.H. Auden’s ekphrastic poem Musée des Beaux Arts stands on its own — though with — Breughel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. Even more so Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn stands on its own; the urn described is unknown. Tetenbaum’s direction of ekphrasis is inverse to that of Auden and Keats. The artwork comes after the literary expression. Nevertheless, her inversely ekphrastic artwork Mining My Ántonia stands on its own — though with — Cather’s My Ántonia.

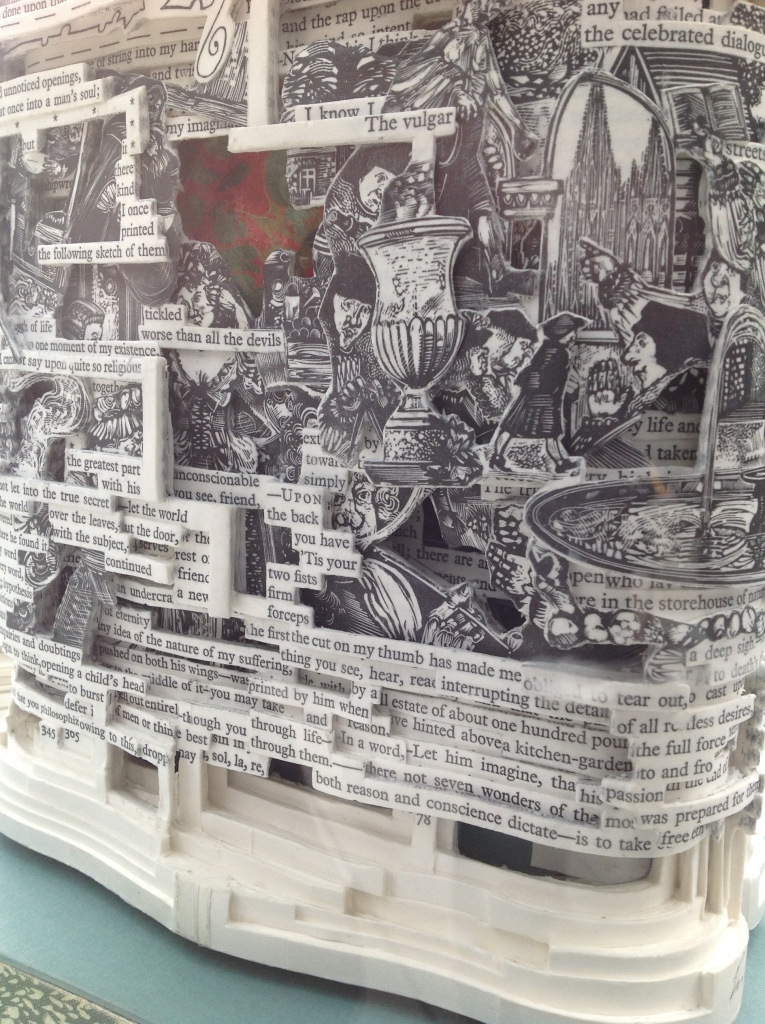

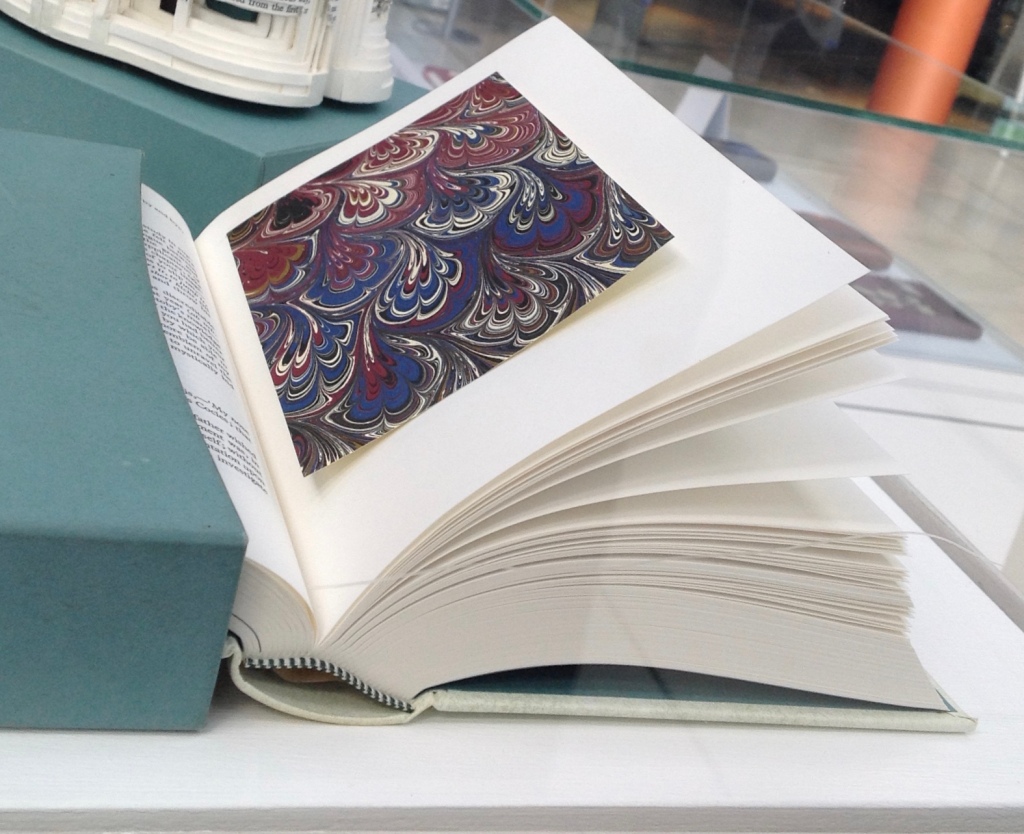

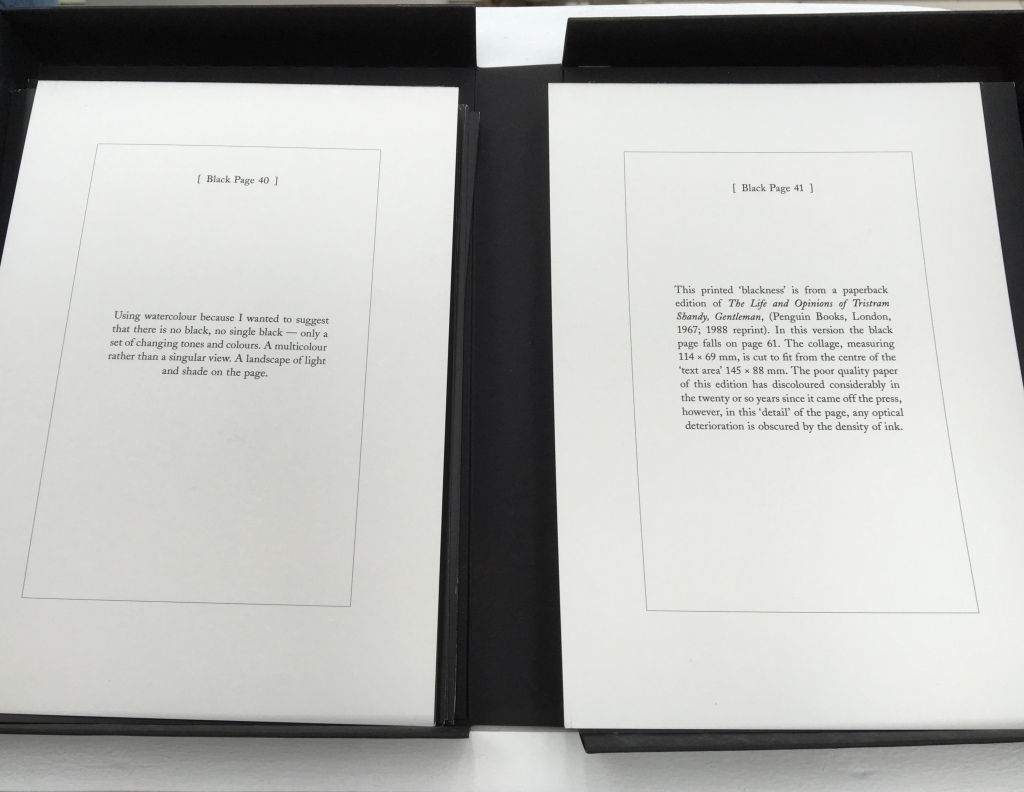

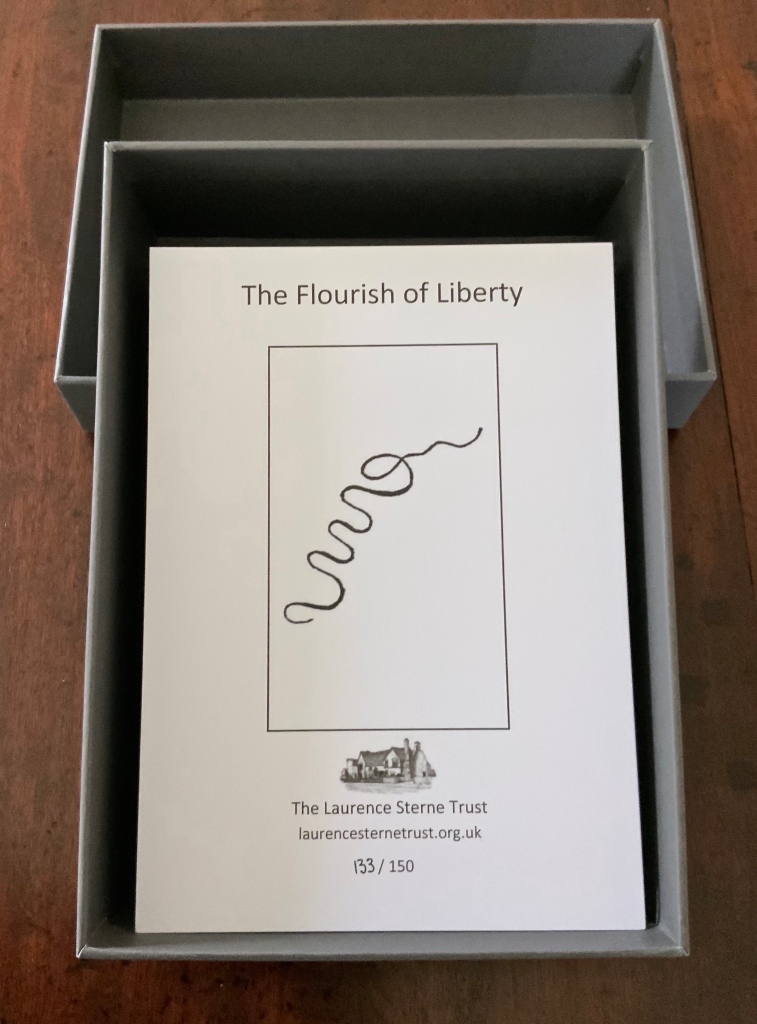

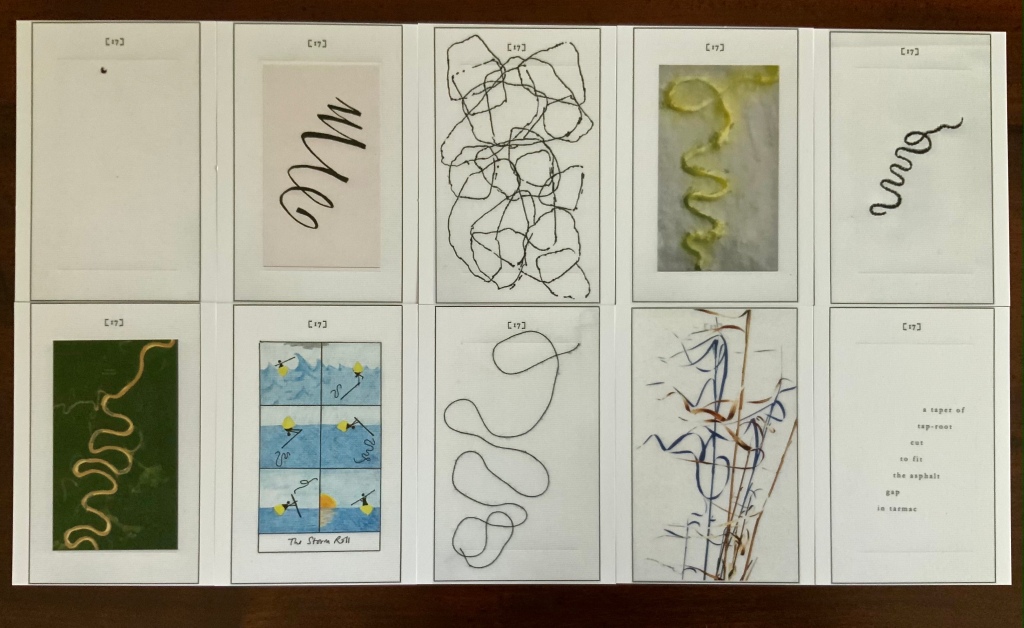

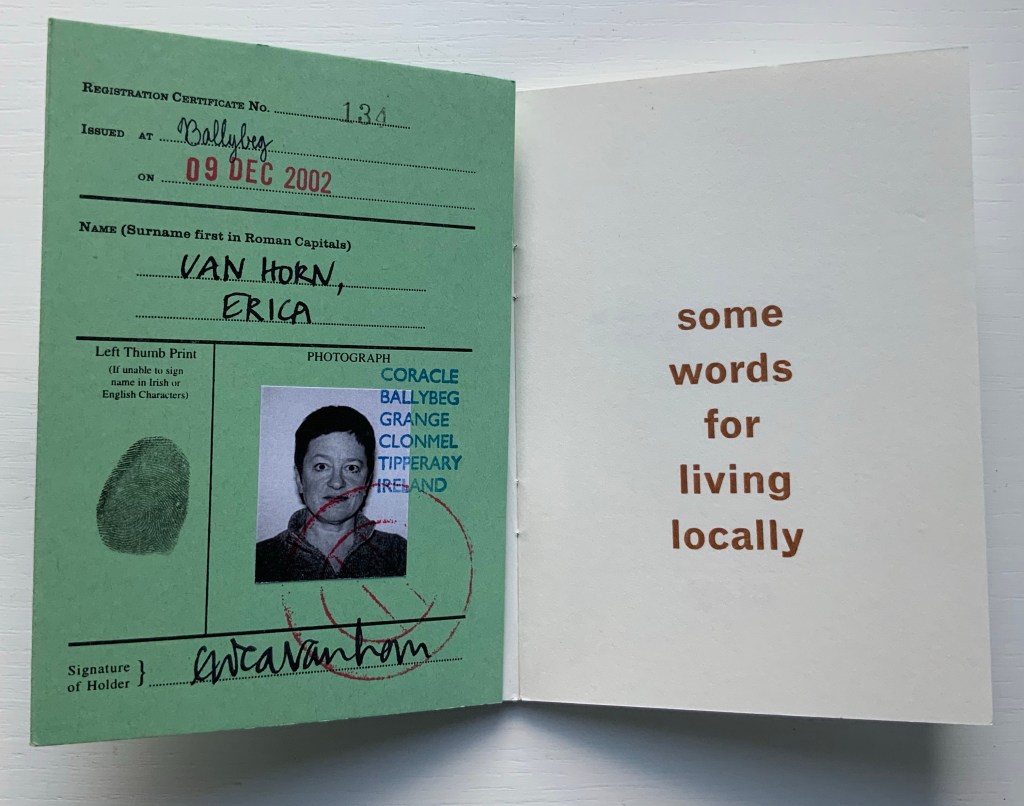

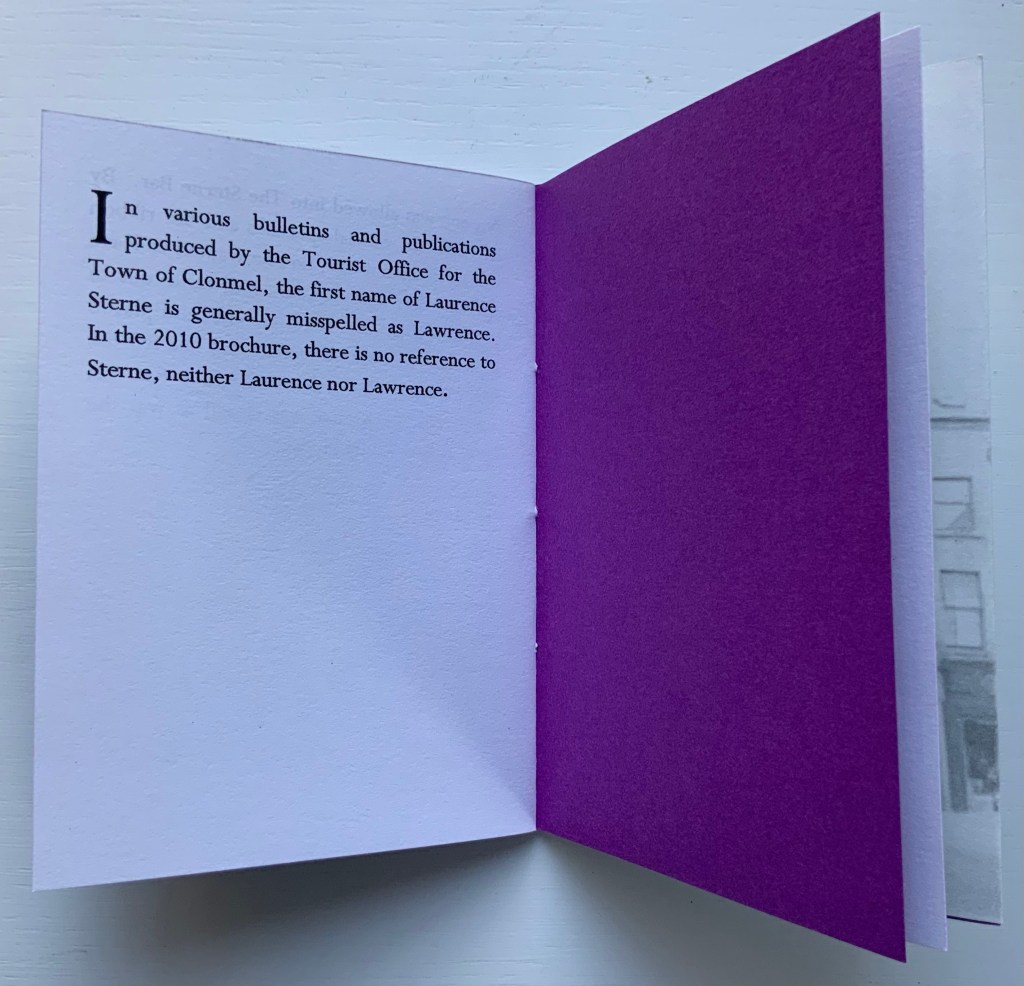

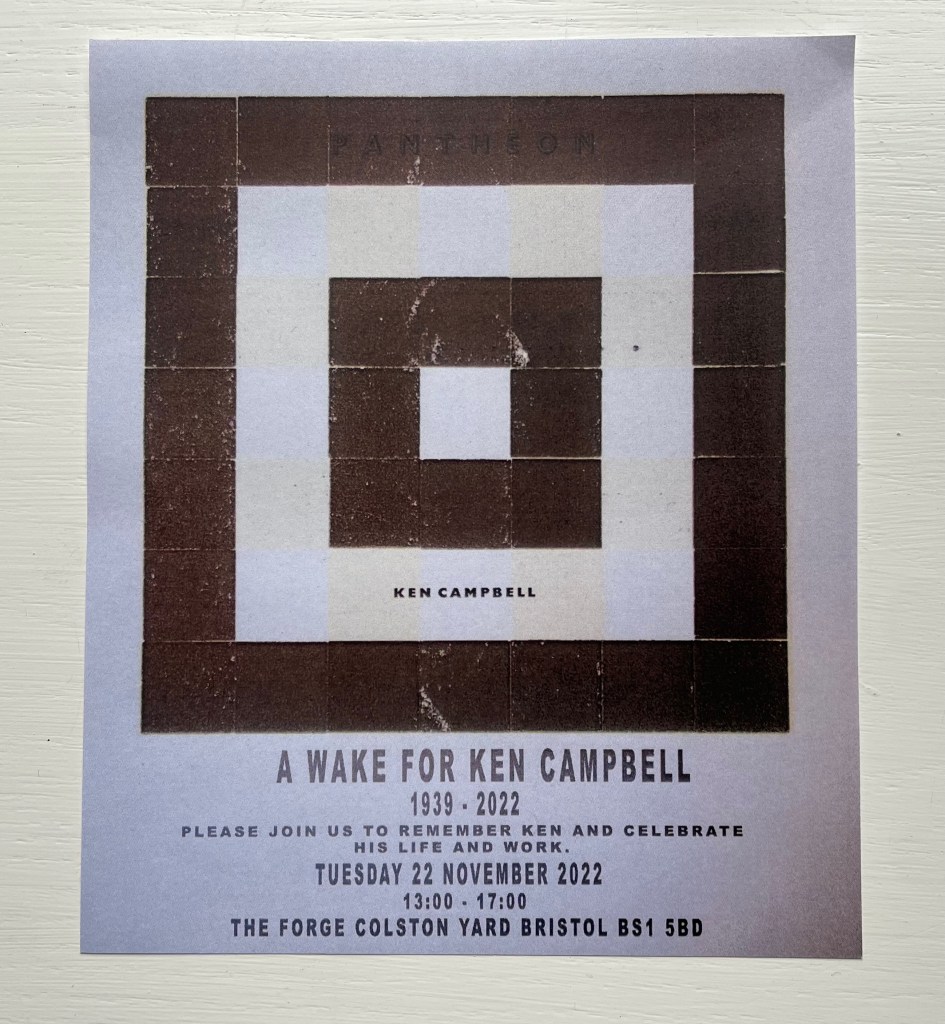

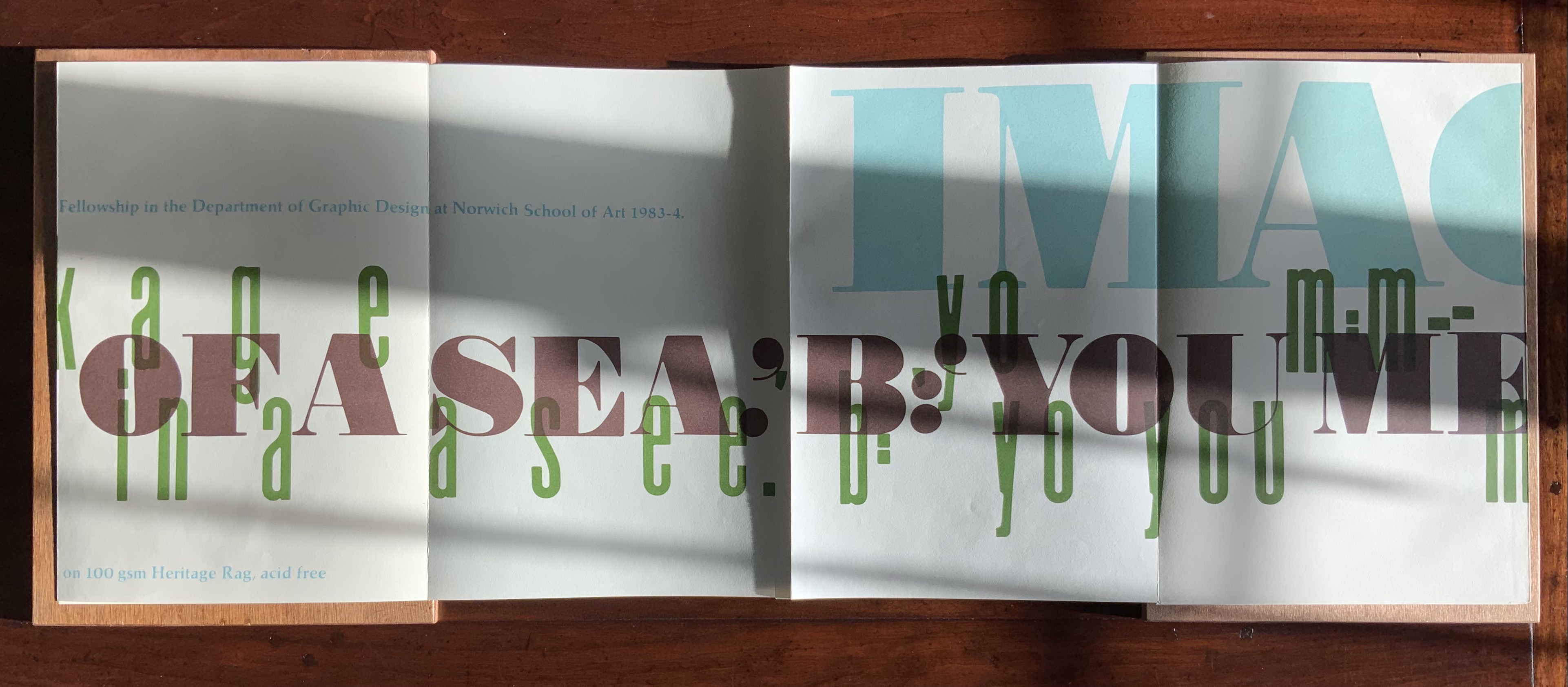

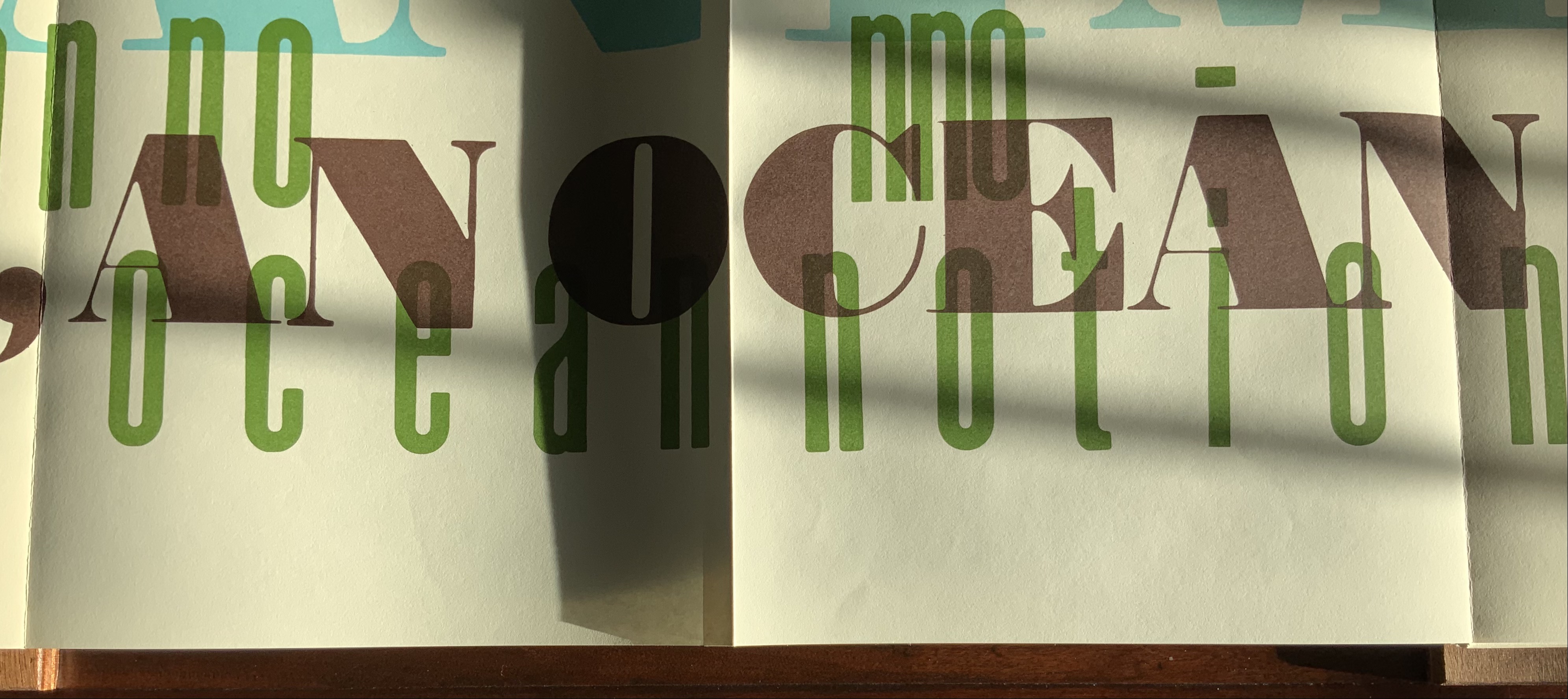

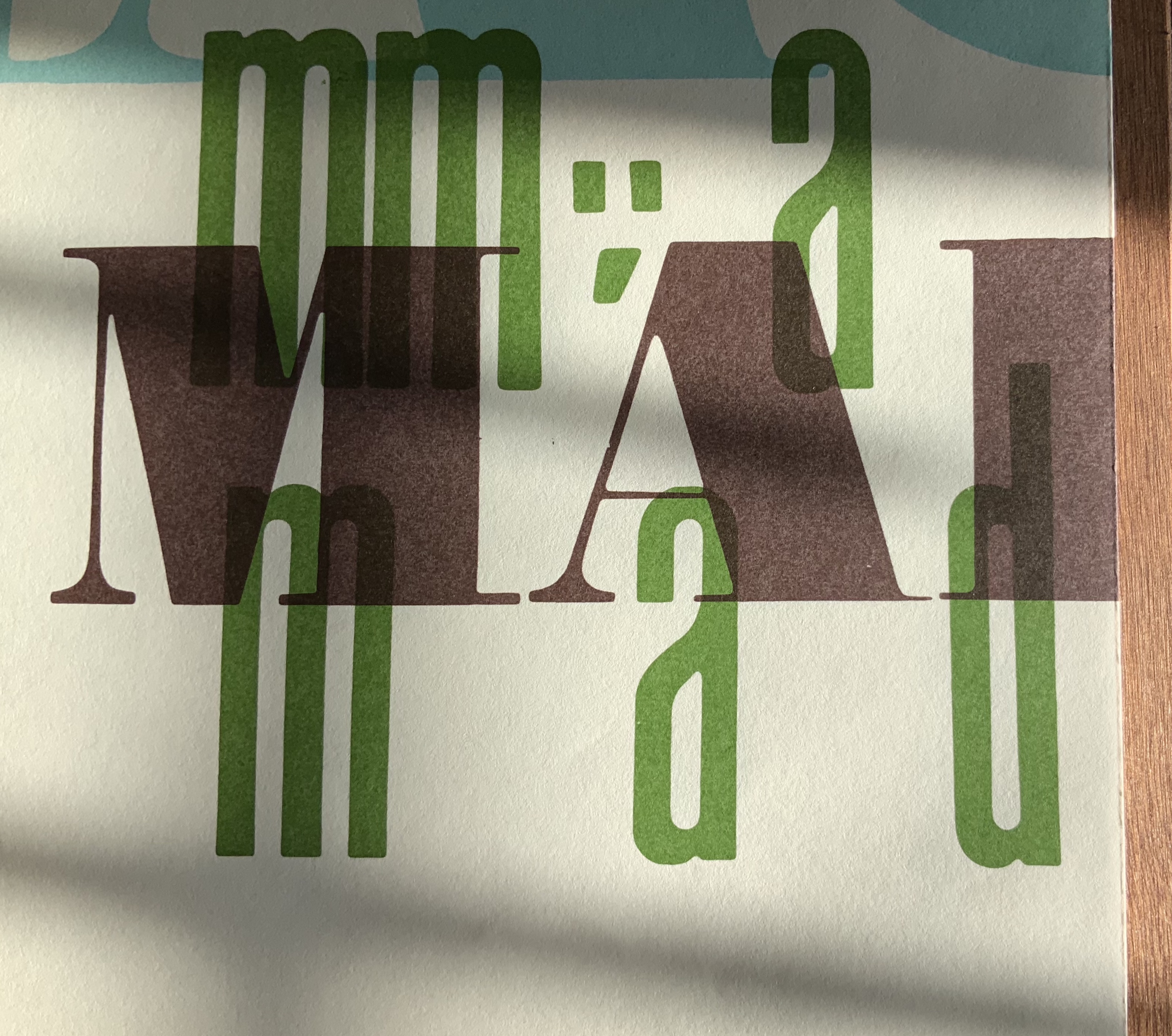

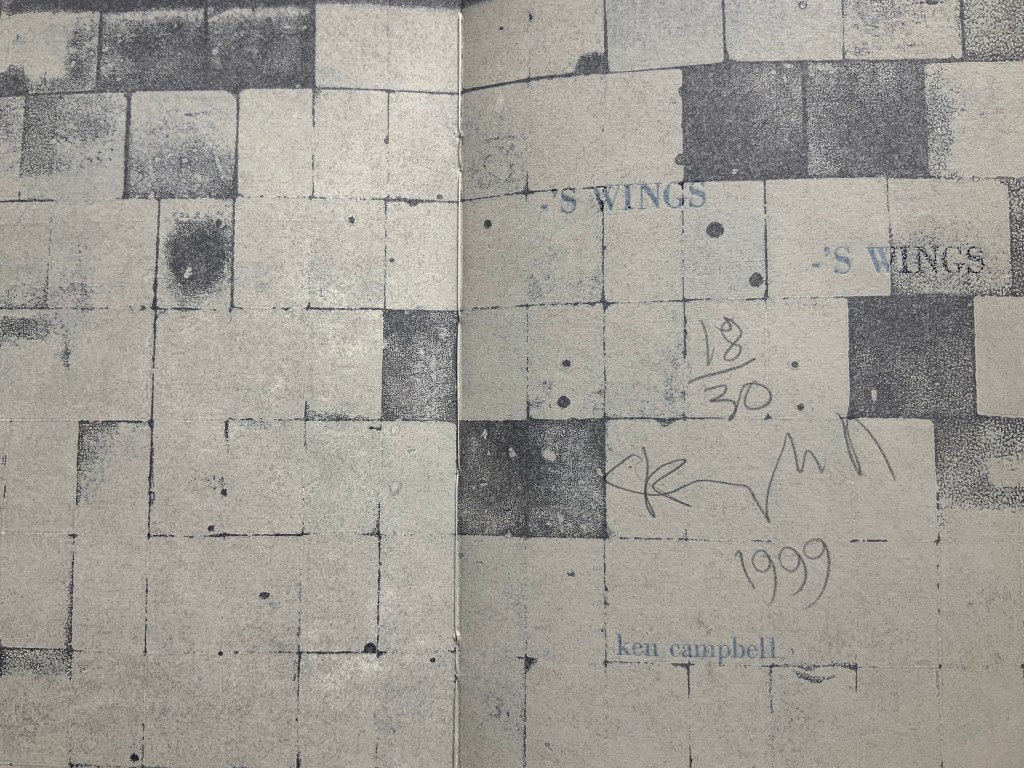

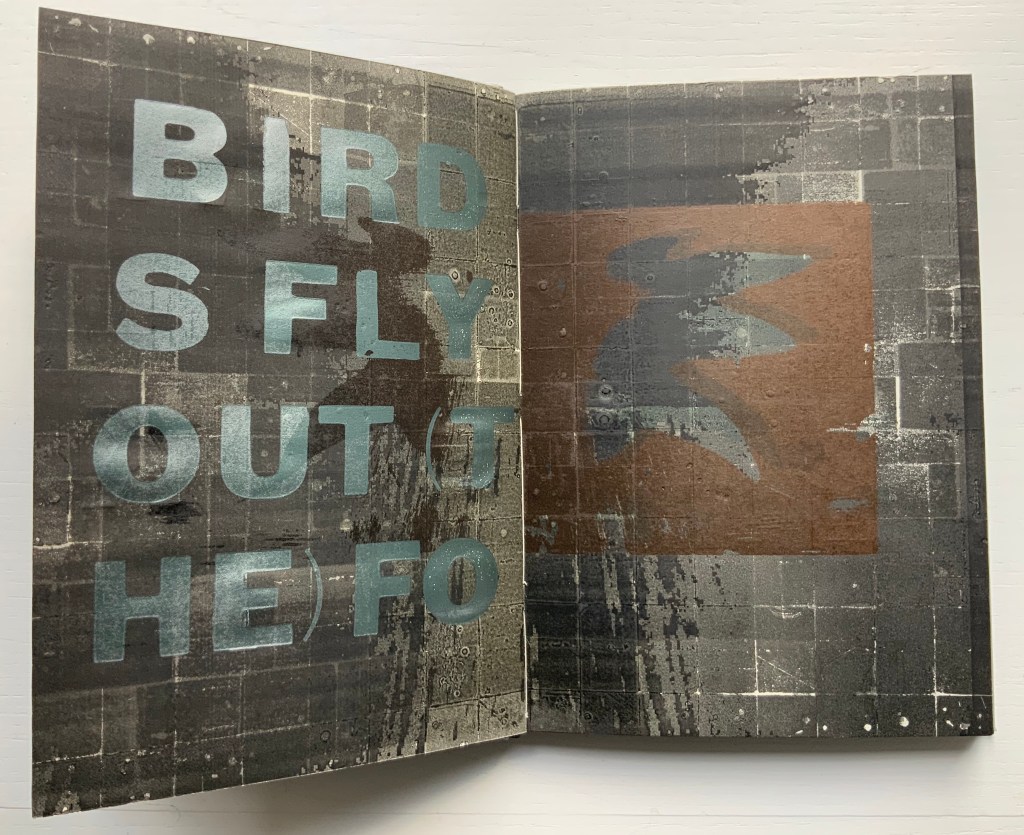

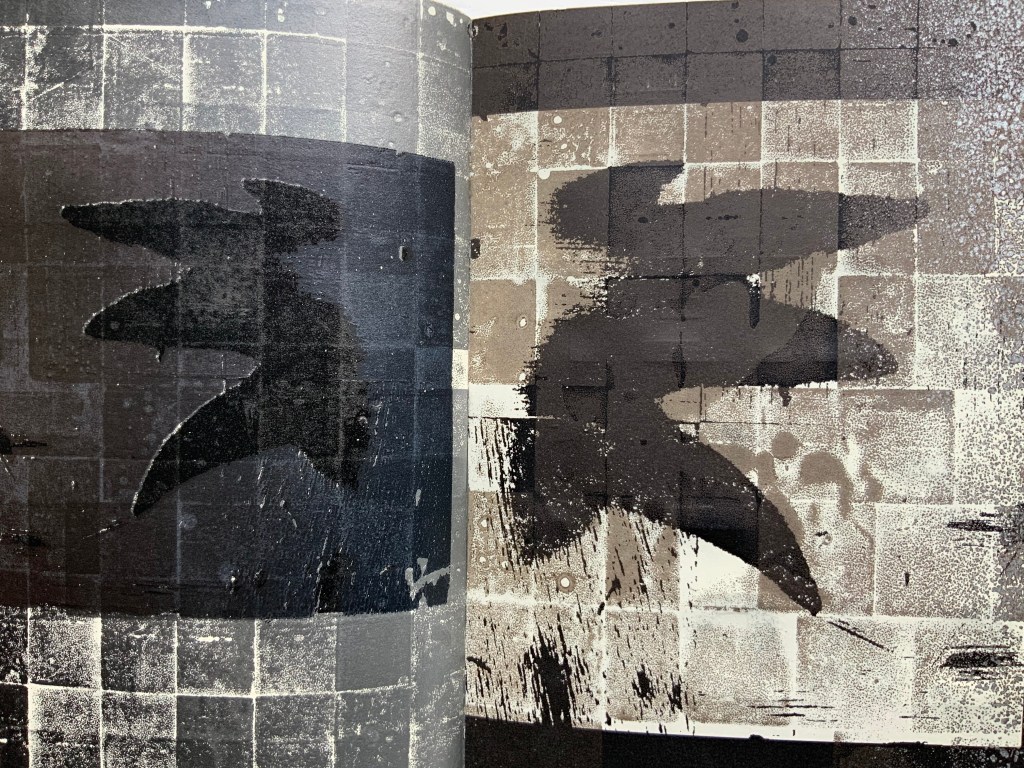

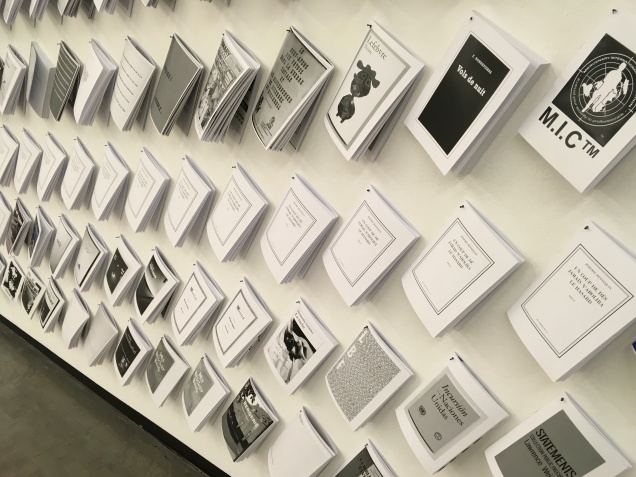

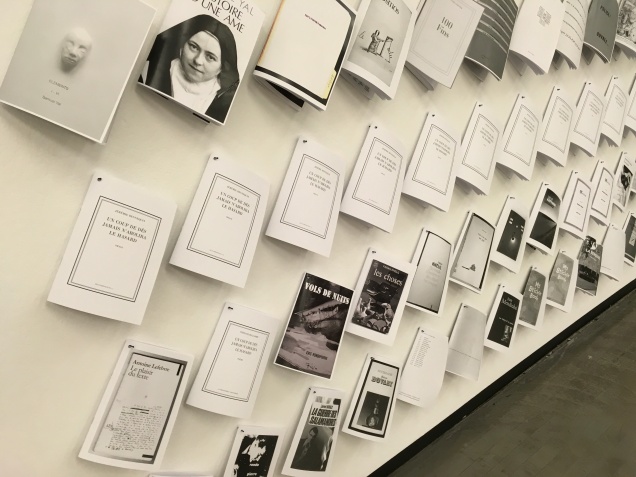

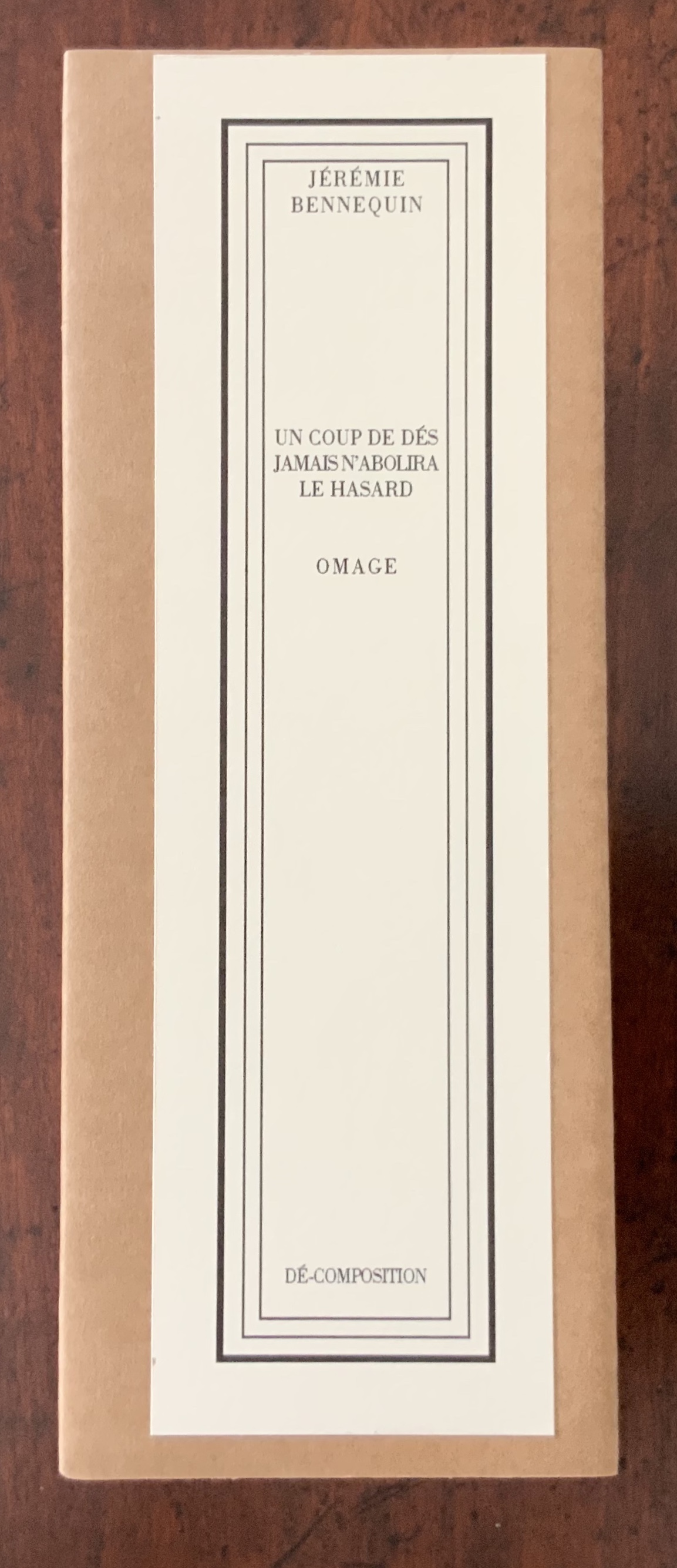

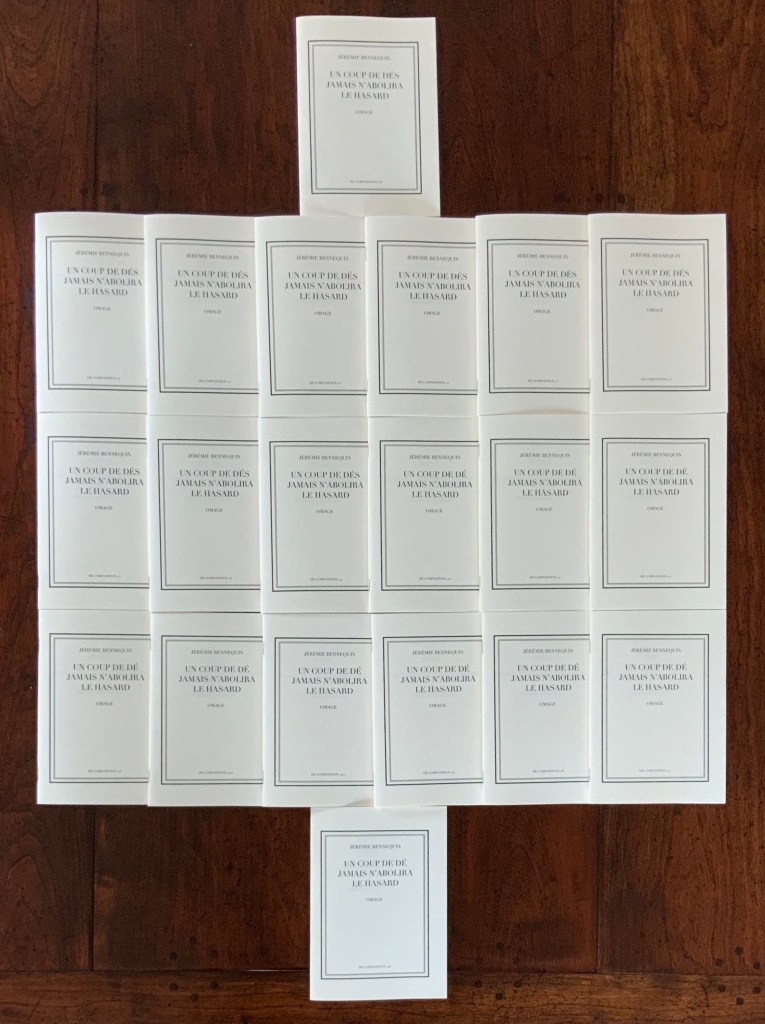

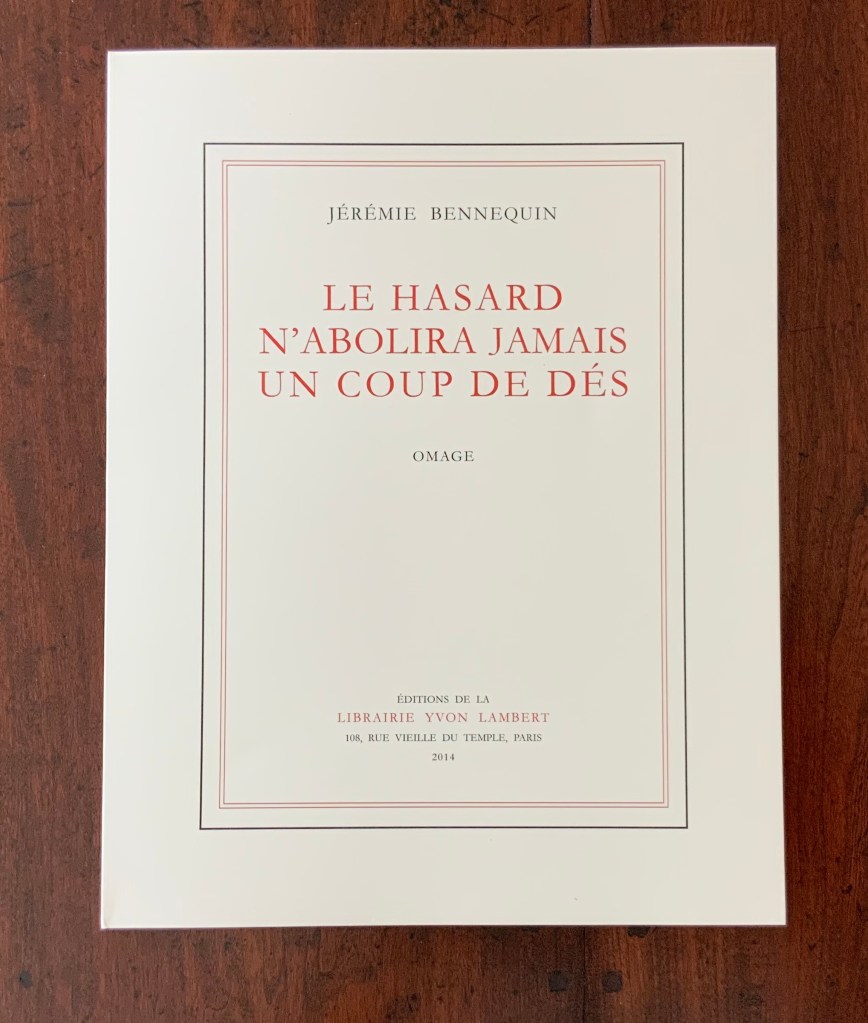

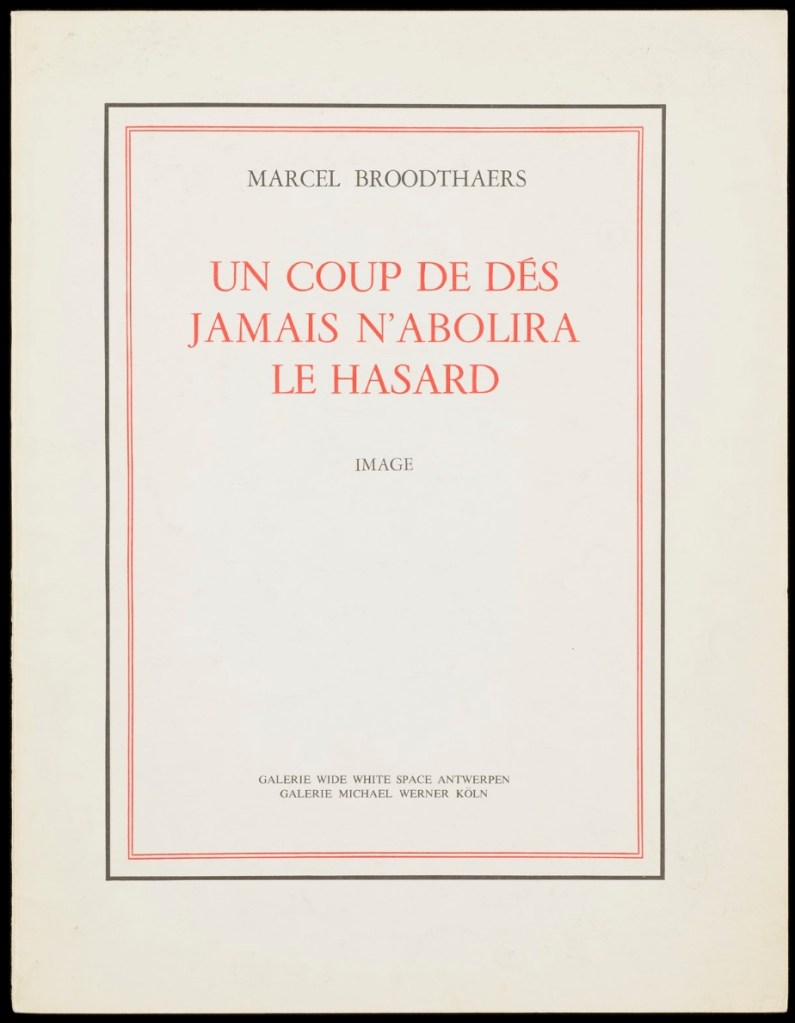

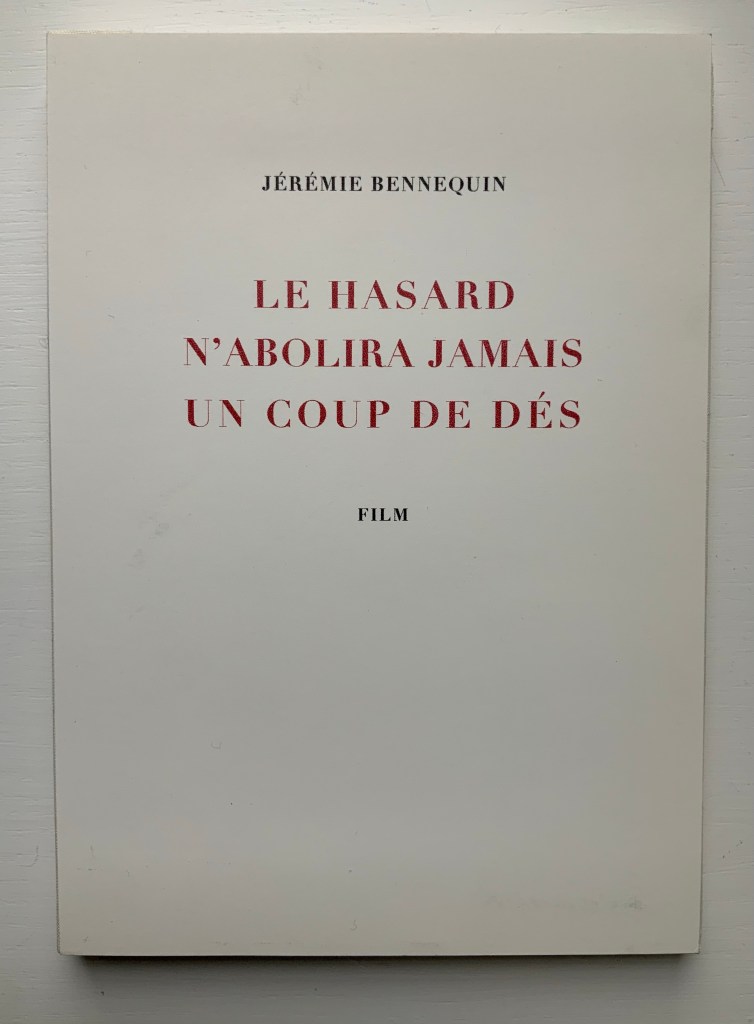

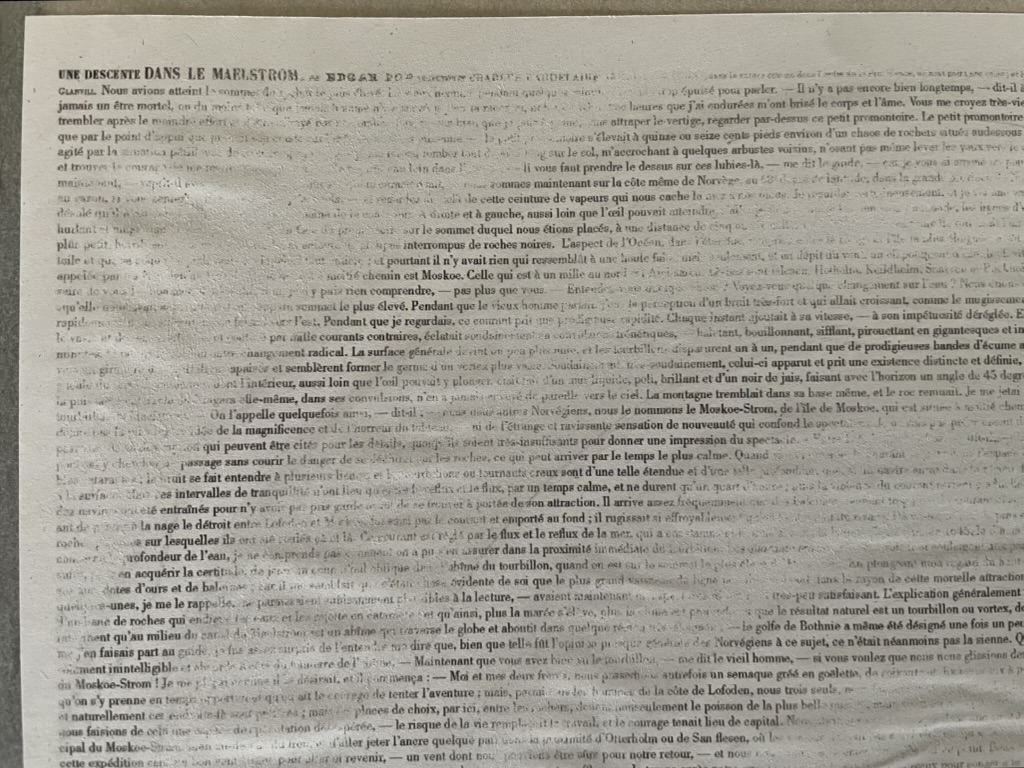

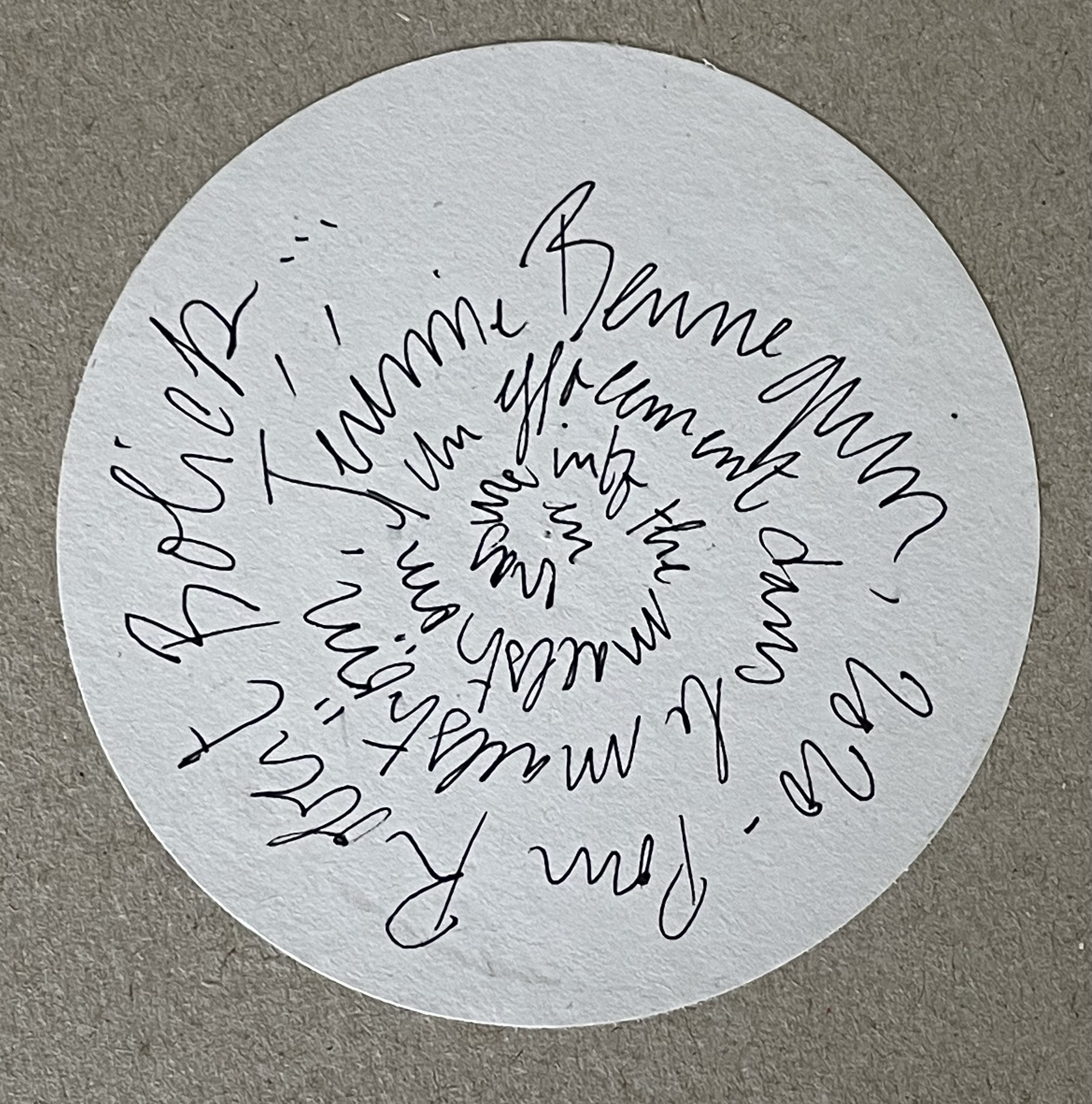

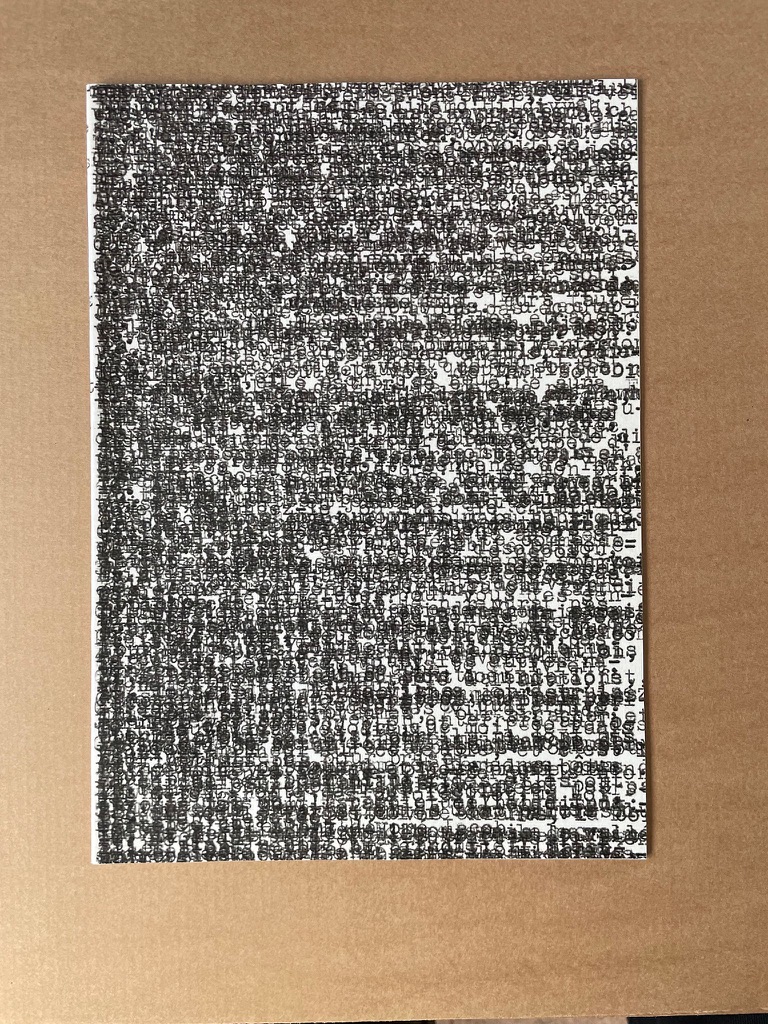

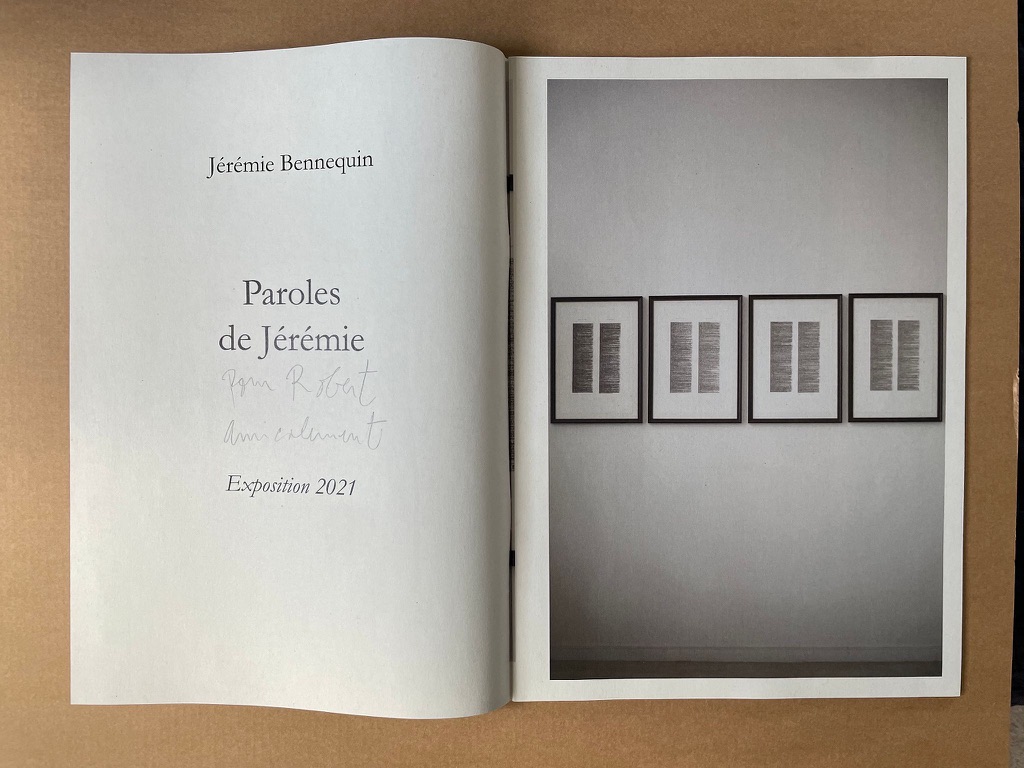

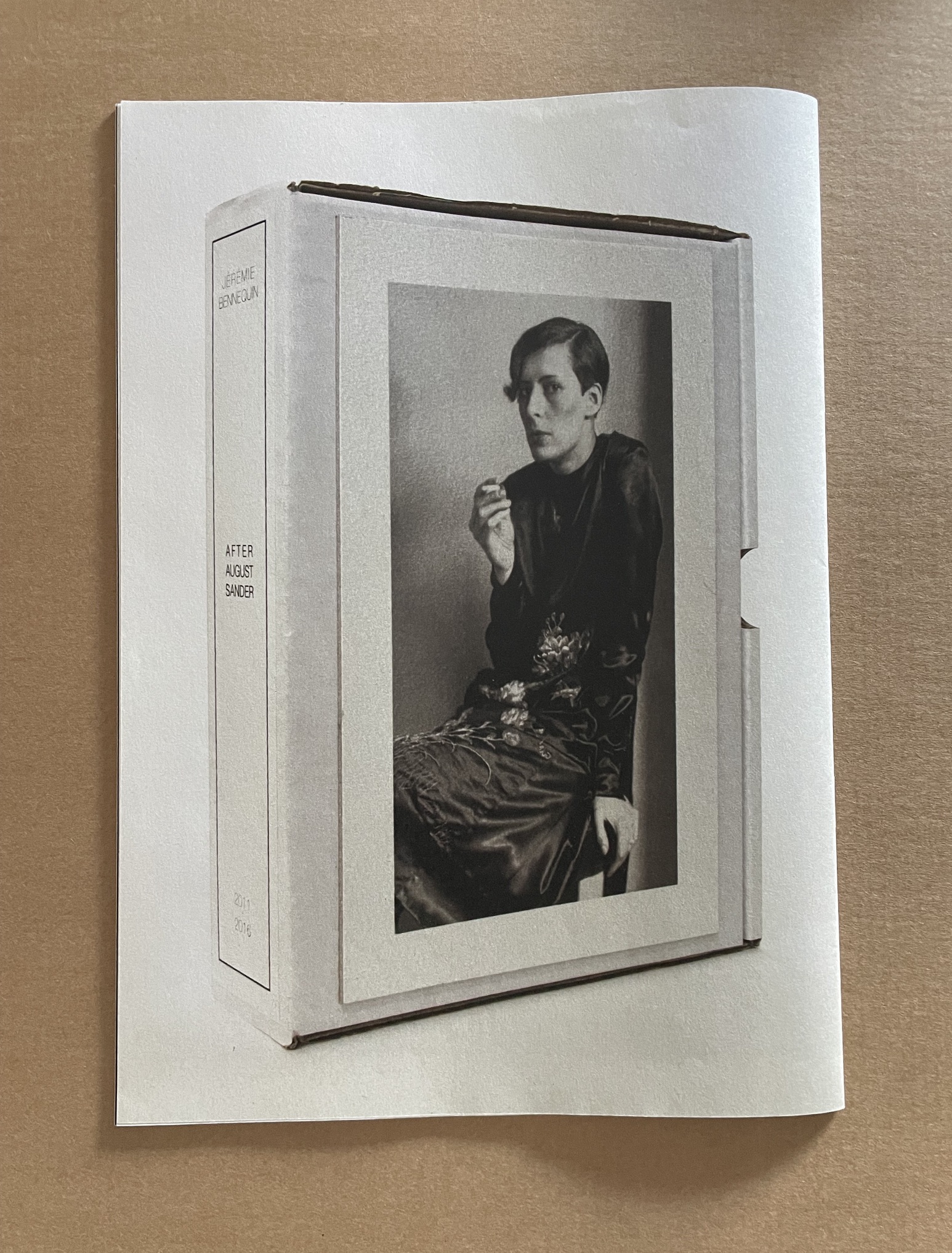

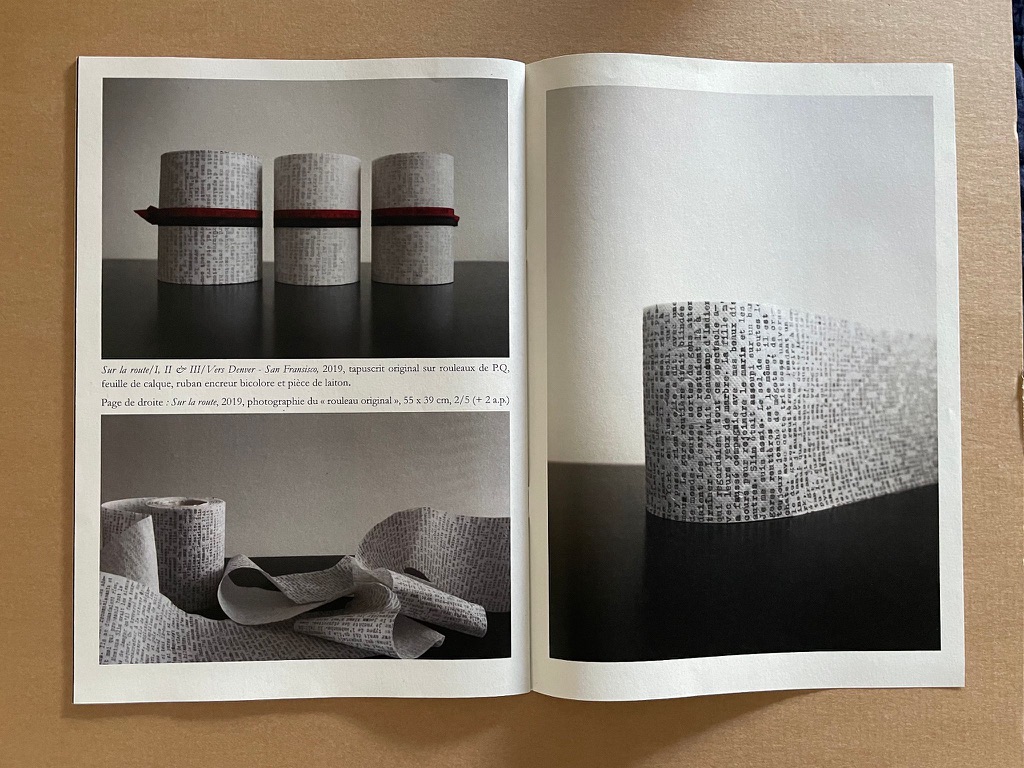

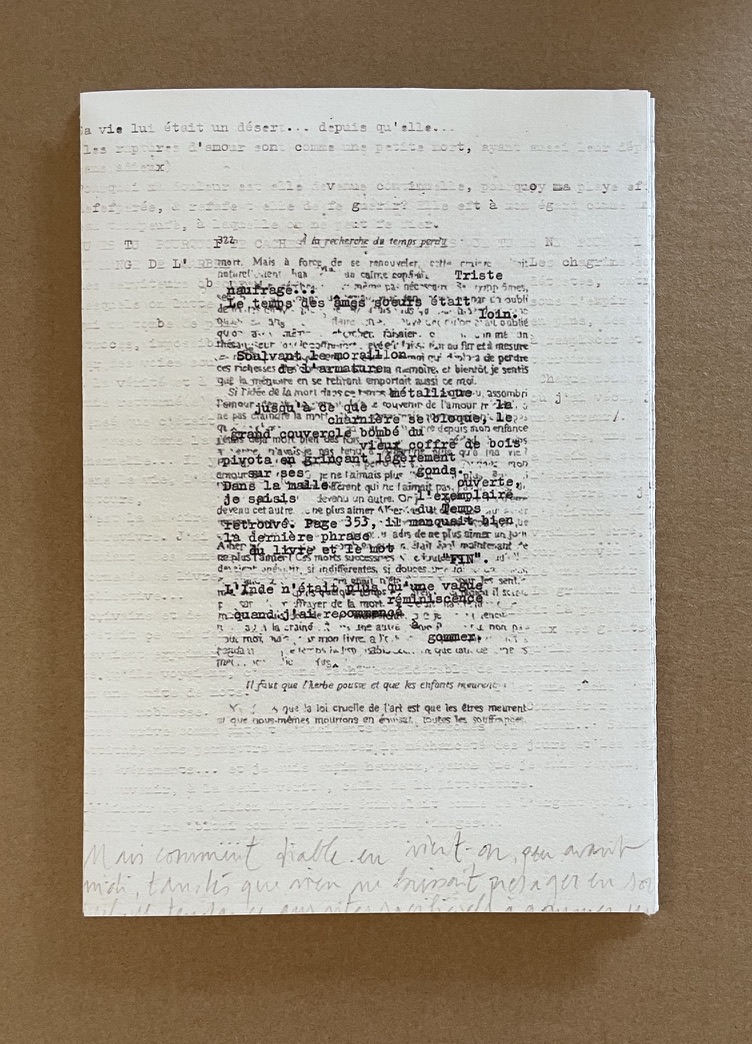

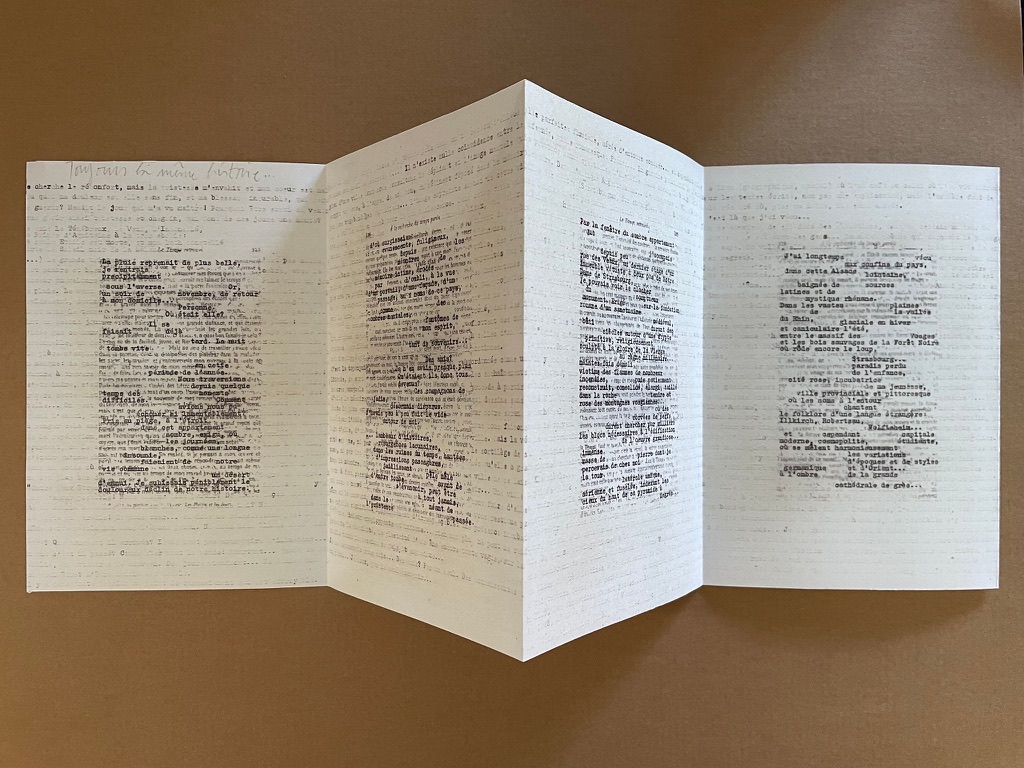

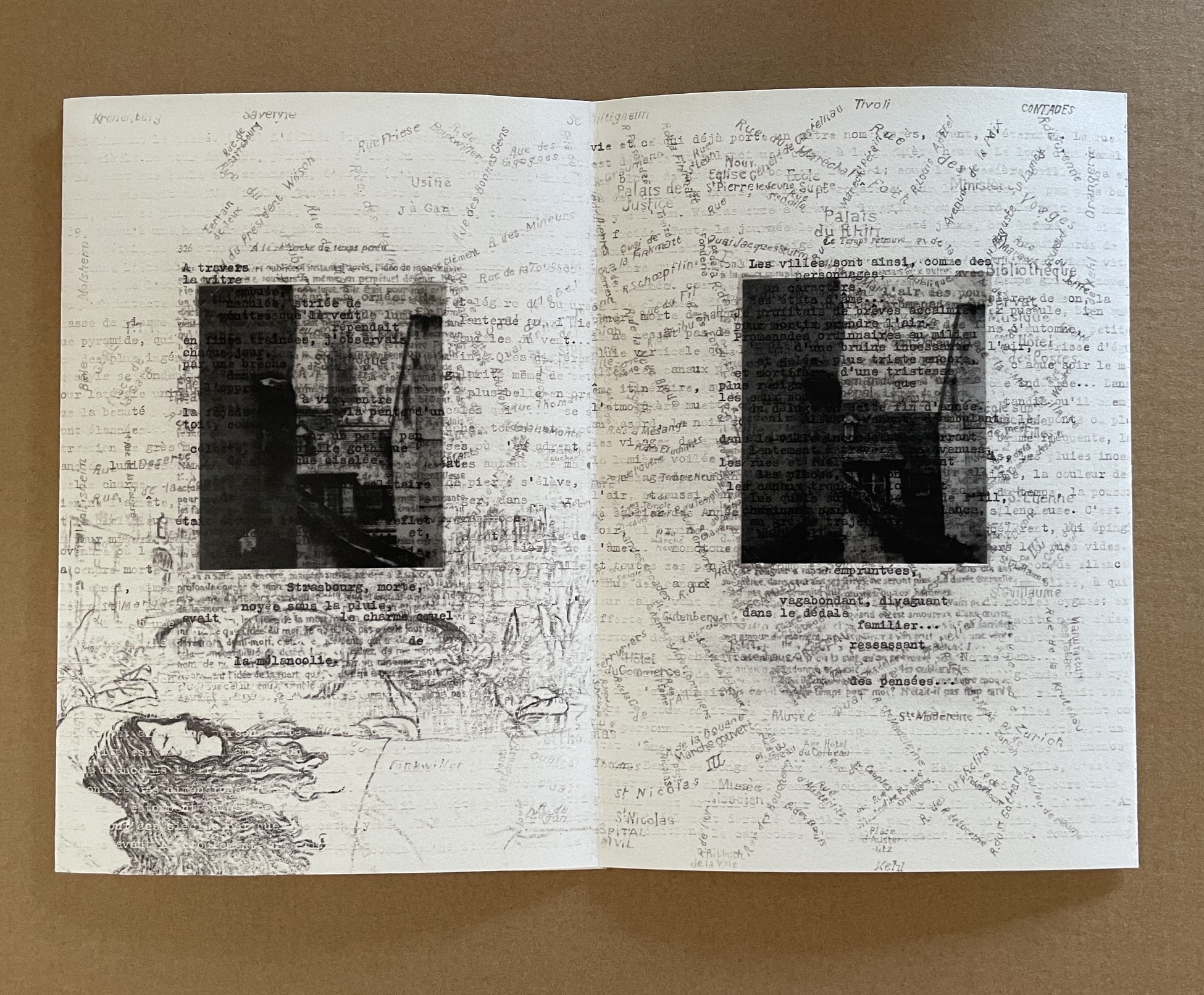

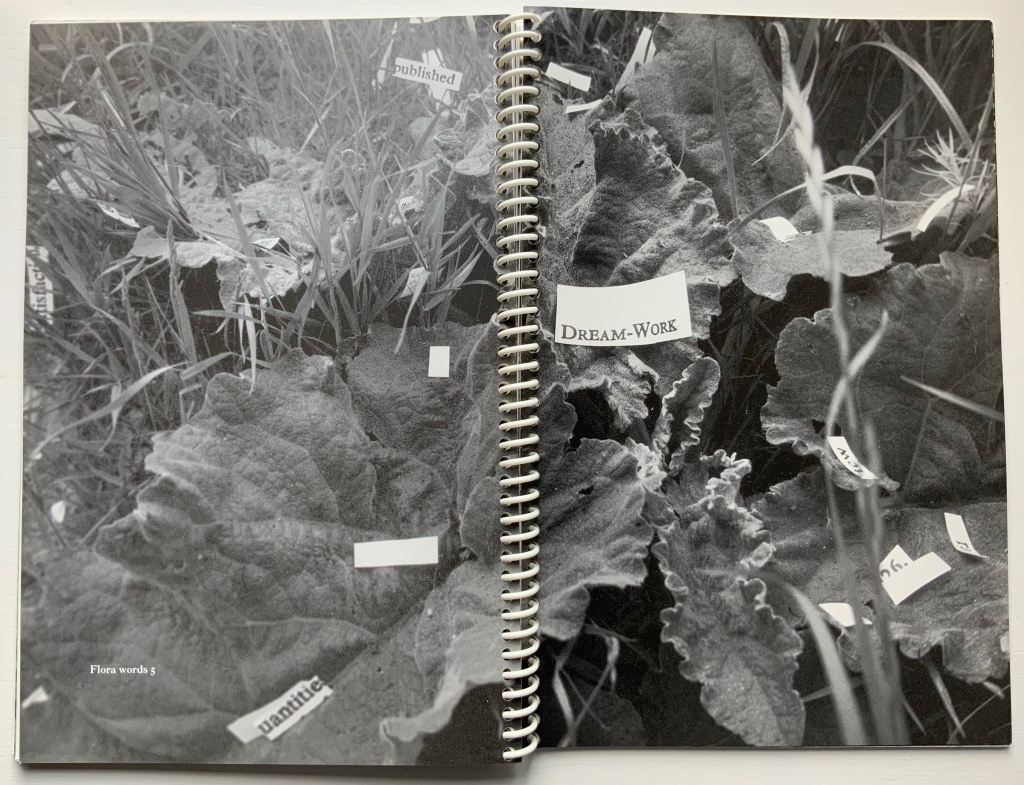

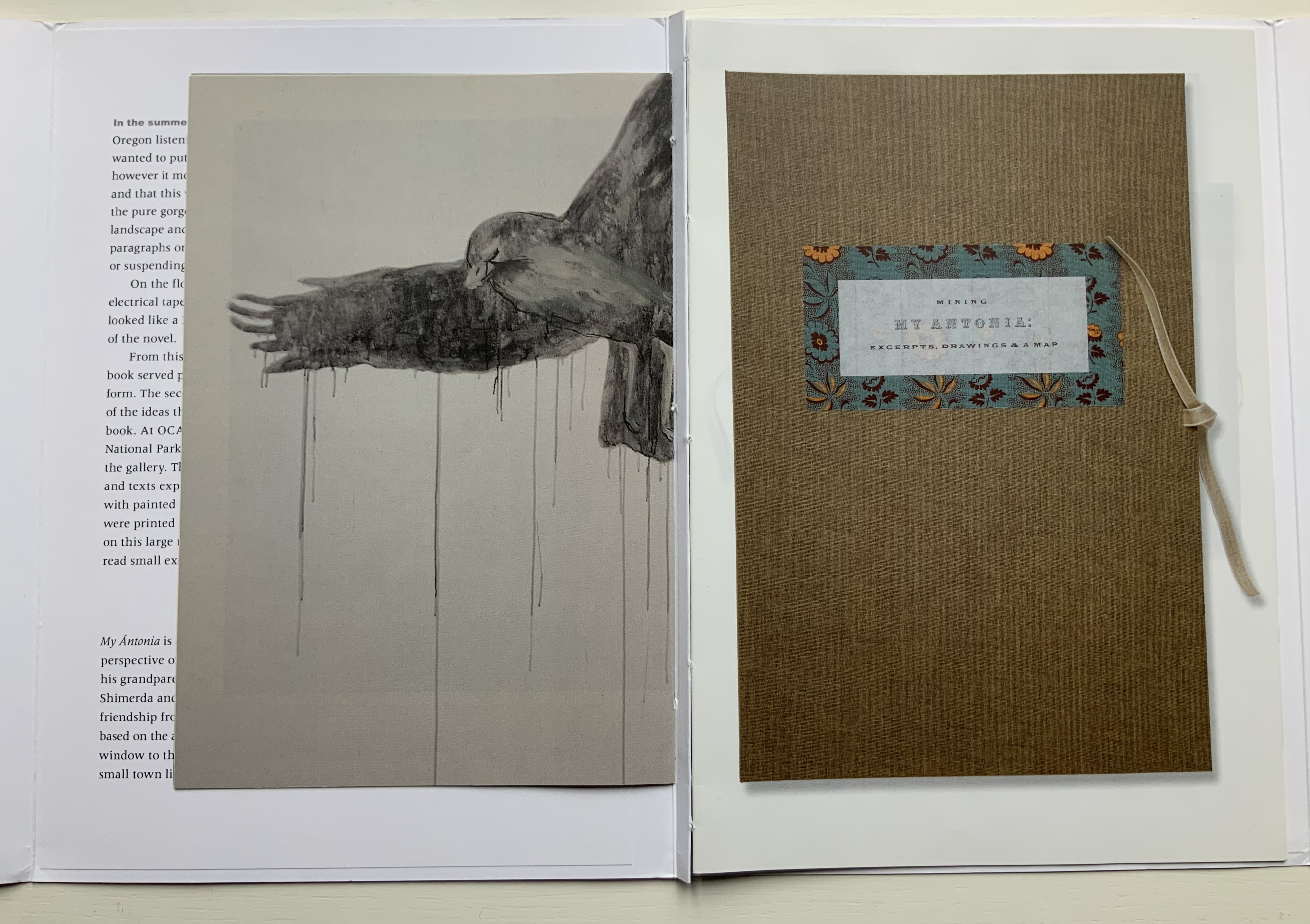

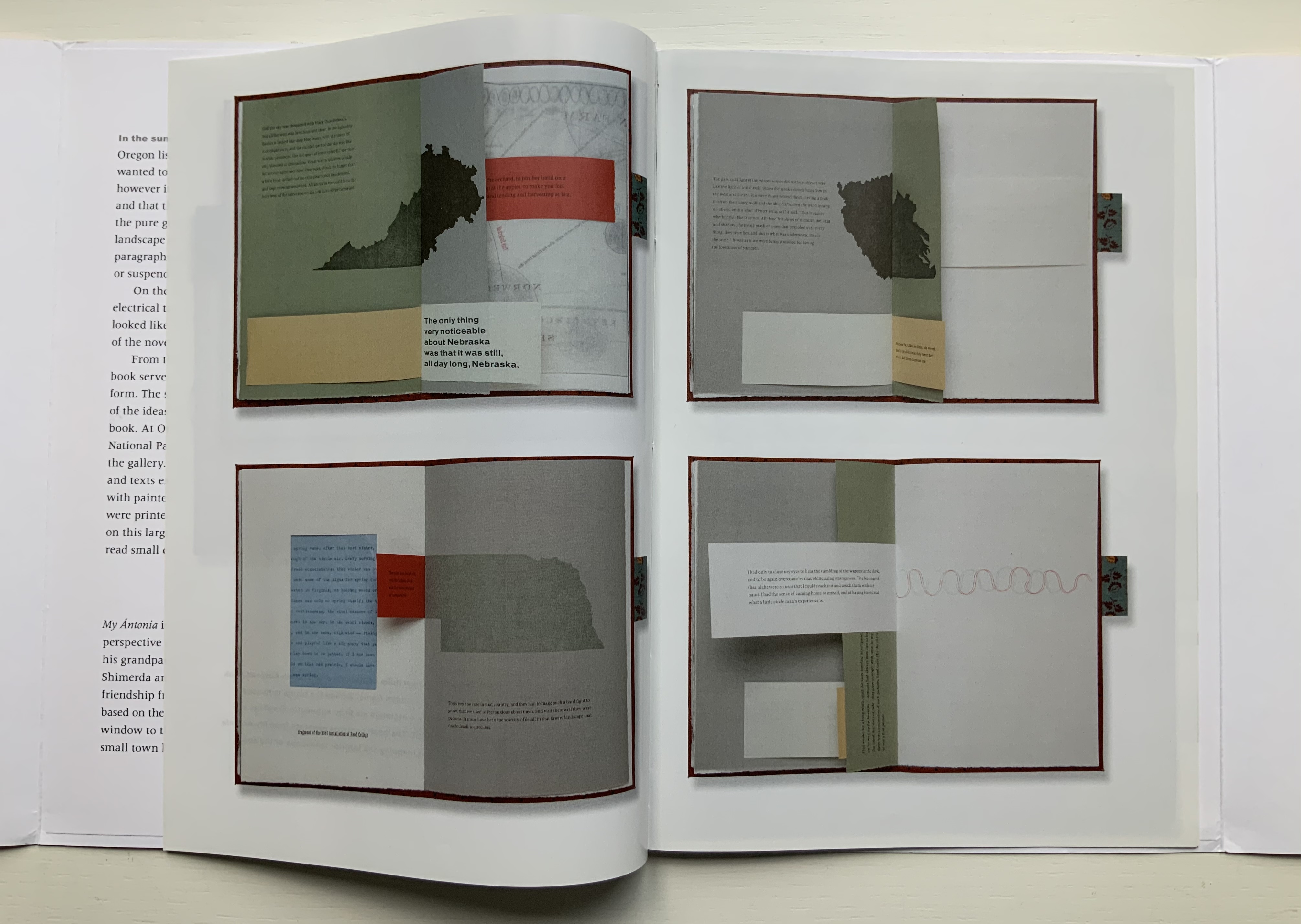

A Close Read: The Cather Projects (2012)

Barbara Tetenbaum and Jennifer Viviano

Catalogue with three inserts sewn to folded card, published by Oregon Arts Commission. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of the artist.

For the collection, the map has been framed between two sheets of glass to make enjoyment of its translucent paper a daily possibility. Each time the catalogue is opened, its binding harks back to O’Ryan’s Belt (see above). Three inserts of different trim sizes are sewn into the central inwardly folded tab.

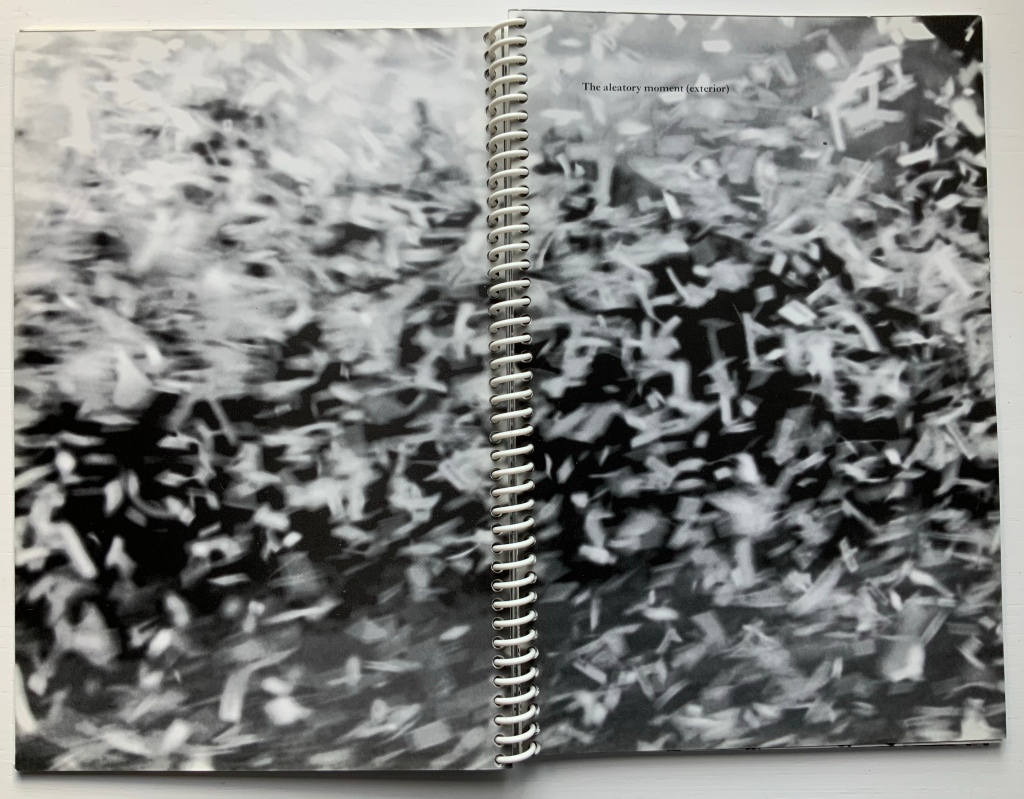

The first insert provides details from the 2010 installation; the double-page spread below recalls the dangling tags from The Reading Room (2002). The second insert shows images of the artist book Mining My Ántonia and details from the second installation in the Hoffman Gallery at Oregon College of Art and Craft (2012); an image of the map from Mining My Ántonia: Excerpts, Drawings, and a Map is shown at the start of this entry. The third insert is a 14-page pamphlet from Nathalia King, Professor of English and Humanities at Reed College where the first installation occurred.

Put aside — difficult as it may be — the play of craft and art so plainly suffusing the print, paper and binding of the catalog and artist book, what are their relation to the text that drove them? Is it like making a “movie of the book”? Are we looking at some new form of literary/artistic criticism? As Nathalia King’s essay walks us through the installation, she points out how it teaches the viewer to read My Ántonia in multiple ways. To what degree, though, can we appreciate Tetenbaum’s book art or installations without having read My Ántonia? They certainly inspire the reader/viewer to read or re-read the work. But inevitably this reader/viewer is drawn back to enjoying Tetenbaum’s “making the novel her own” (as in the pun on mining). As with all book art, the more informed we are about the “material” of which it is made, the greater the enjoyment. We want to make such a work our own — to mine it — which may send us back to multiple quarries from which the artist drew her material. Cather’s novel is not the only material of which Mining My Ántonia is made. It is made of the artist’s experience of the novel in print, the novel as read aloud and the exterior/interior space in which that occurred. It is made of various papers, tabs, reveals and media. The artist book offers a solitary way of ”material reading”, but with the catalogue, it also offers a glimpse at the ambulatory and perhaps social way of reading offered in the installations.

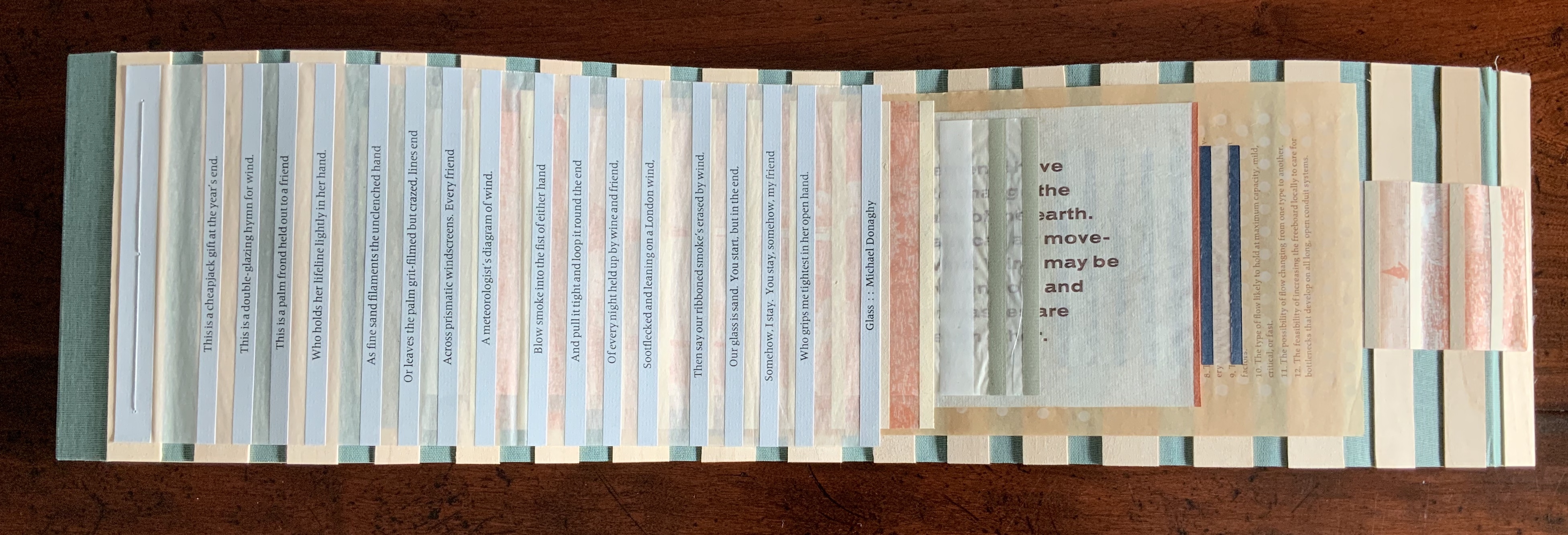

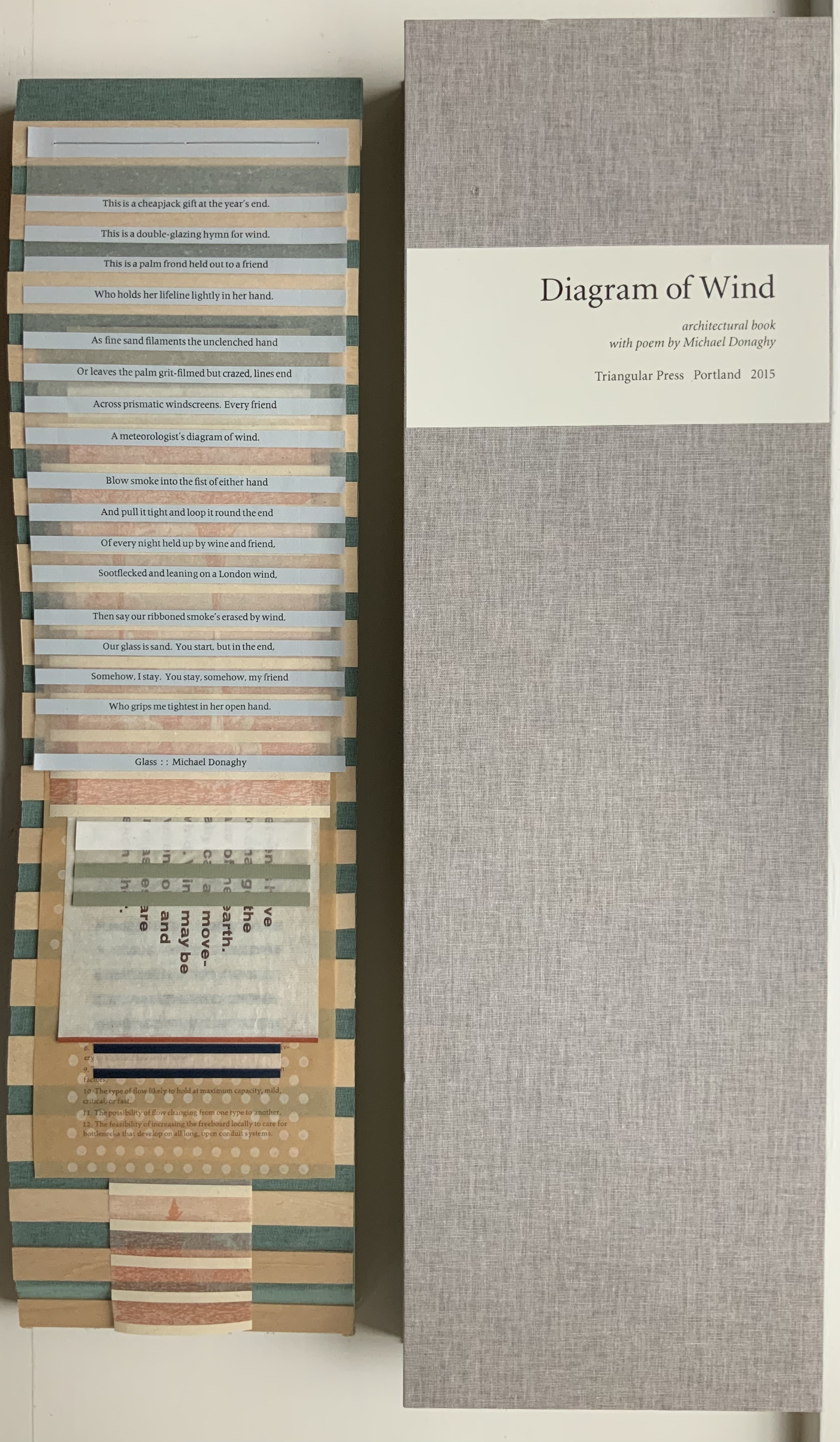

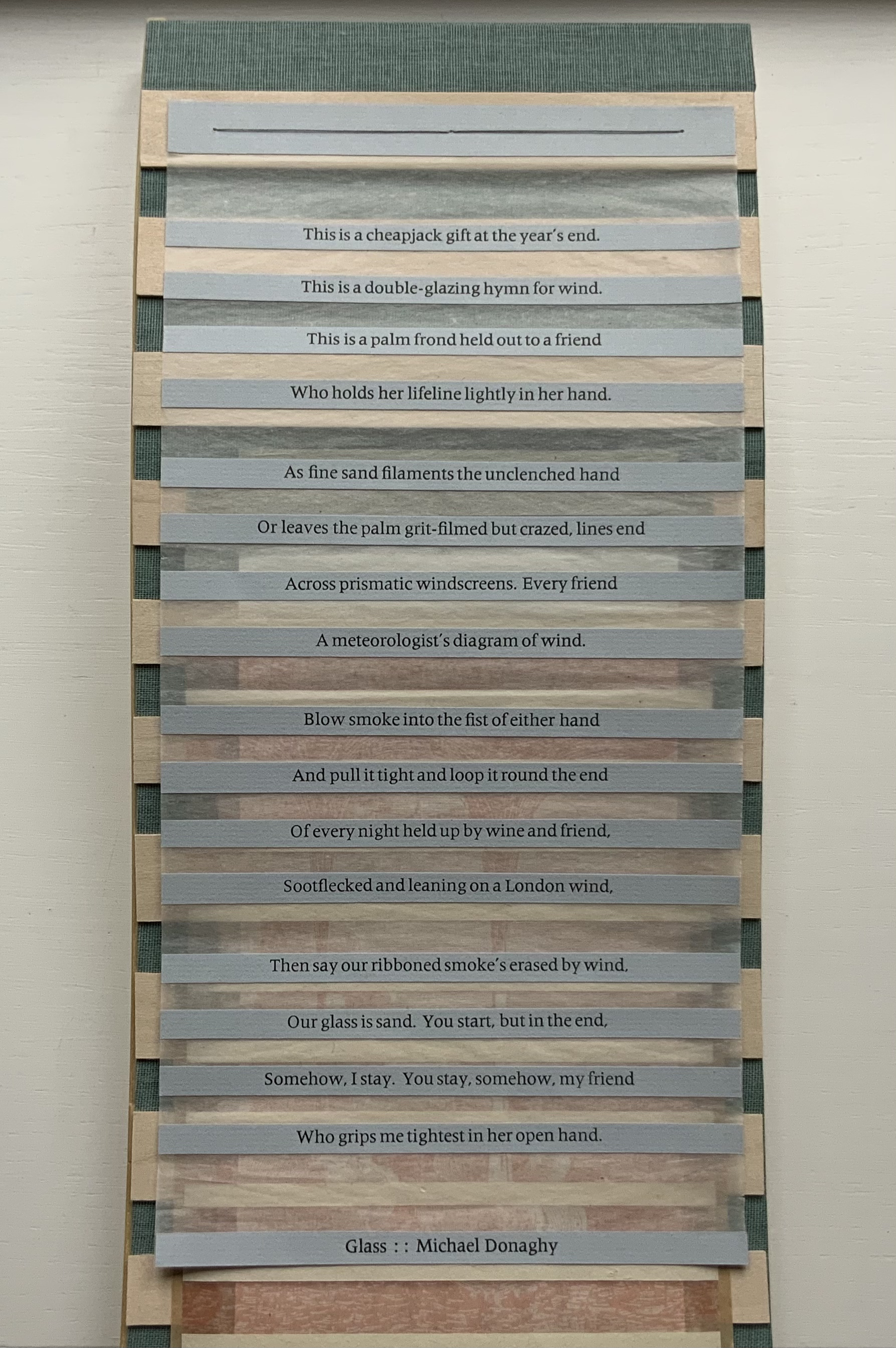

Also offering a different way of reading, Diagram of Wind (2015) pulls further away from its responding point than Mining My Ántonia. A line in Donaghy’s poem “Glass” provides the title for this sculptural work, and the work’s structure draws on the poem’s sestina form in its undulating, layering structure. Yet Diagram of Wind goes far beyond that.

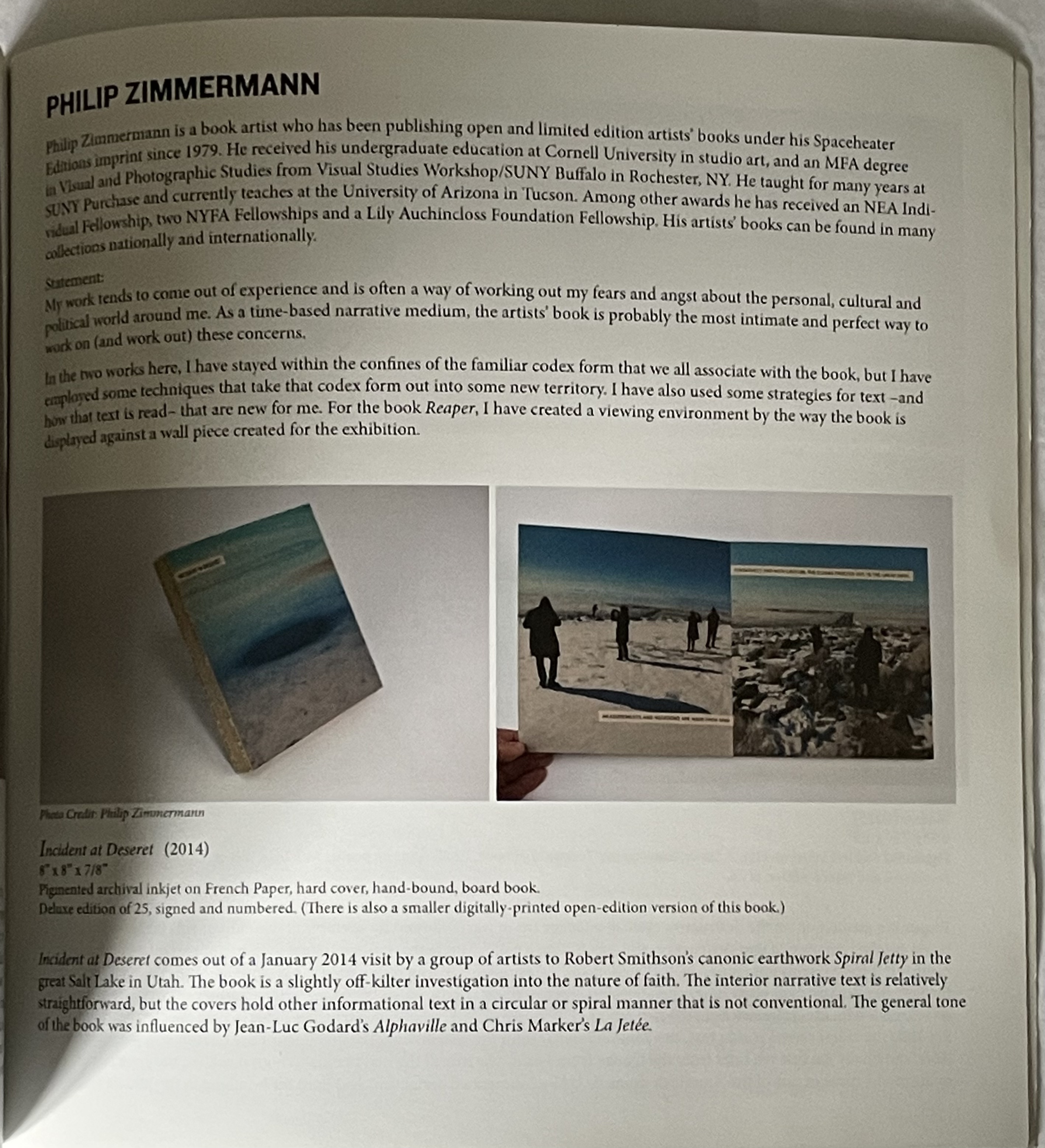

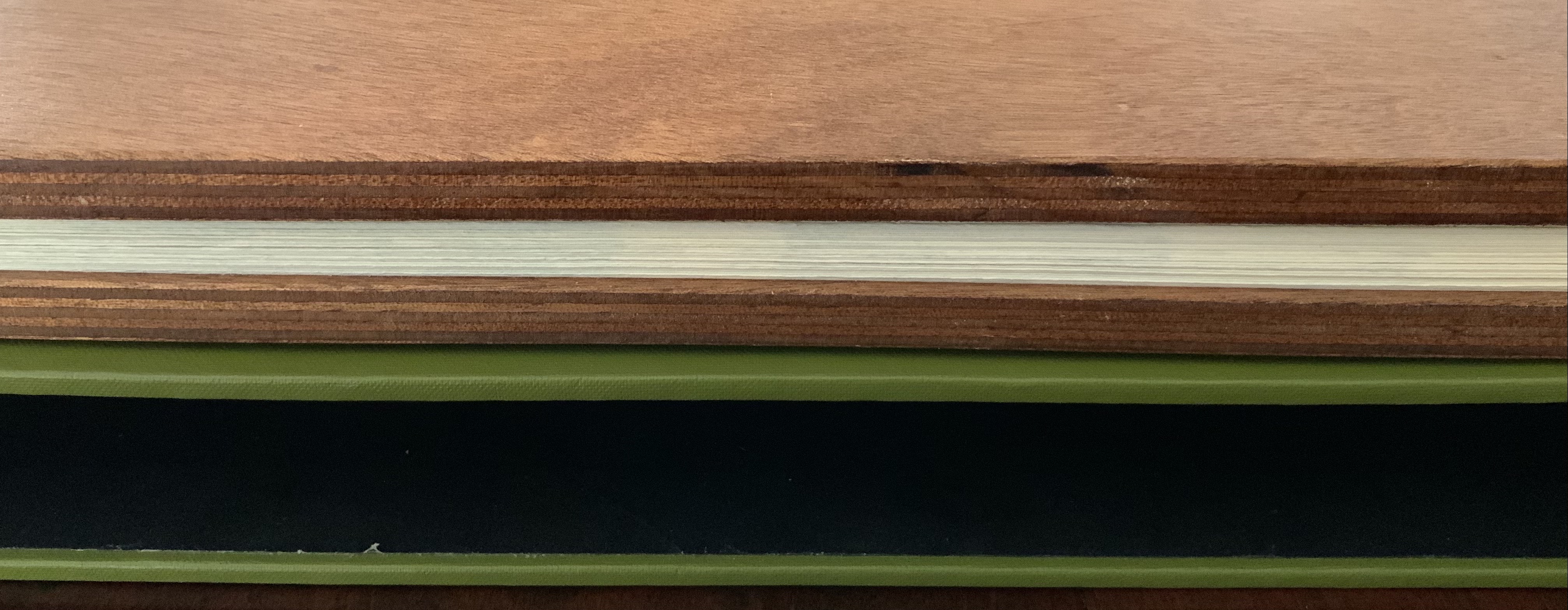

Diagram of Wind: architectural book with poem by Michael Donaghy (2015)

Barbara Tetenbaum

Housed in a clothbound box (H590 x W180 x D52 mm). Book of seven overlapping pages of various papers including gampi (silk tissue), Zerkall Ingres and F-color, collaged with letterpress-printed text and images and sewn to backing of cloth and wood slats (H567 x W153 mm). Designed to be viewed horizontally on the wood platform (H565 x W153 x D39 mm) or vertically hung from the wall. Edition of 25, 0f which this is #11. Photos: Books On Books Collection, displayed with permission of Maddy Paxman and the artist. “Glass” © Michael Donaghy Estate.

There are seven “pages” to this work, each sewn to green book cloth panelled with wooden slats and backed with gampi. The first page carries Donaghy’s sestina, each line letterpress printed on a strip of paper pasted to gampi paper. Less wide than the sestina page and shorter than the third, the second page shows an etching image of waterspouts rising from a body of water with mountains in the background. Less wide than the second page and shorter than the fourth, the third page consists of narrow, evenly sized white strips of paper pasted on gampi. The fourth page, slightly wider than the preceding page but still shorter than the following, offers the school-book-like statements:

Air movements have helped to change the whole face of the earth. We usually call air move- ments wind. Wind may be started when cold and warm air masses are next to each other.

Suddenly much less wide than the fourth page but still shorter than the sixth, the fifth page presents narrow dark panels or strips that narrow in themselves and narrow the space between them as they descend the page. Much wider than the preceding page, shorter than the seventh and printed with blue and white dots reminiscent of Co Pilot (above), the sixth page gives guidance on determining the amount of space to leave between the top of a flume (an engineering structure for measuring water flow) and the height of the water moving through it. The narrowest page of all and ending flush with the slatted backing, the seventh page shows a print similar to that on page two, but here between the evenly spaced paper strips, there is a small ship in the distance and the subsiding whirlpool and withdrawing upper part of a waterspout in the foreground.

The poem that inspired this work uses images of the natural world — sand, smoke, wind — to build its metaphor of love’s paradox (its holding fast with an open hand). Humanity is in the foreground, nature in the background. Tetenbaum’s Diagram of Wind reverses that. Nature with its air movements and waterspouts move into the foreground. Then humanity with its controlling and measuring flume comes into the middle ground. And finally it ends with humanity’s ship on the horizon and nature’s dissipating waterspout in the foreground. Even though by virtue of its page one position the poem is in the foreground, it has become as much “material” for the artwork as the paper, ink, wood, cloth, earthy colors and physical structure are. The artist has transformed the poem’s sestina shape, its use of nature and its paradox into “material” for Diagram of Wind. In this instance of inverse ekphrasis, Tetenbaum has created a work that stands independently of, and in dependence on, its literary inspiration.

An early guidebook and two of Tetenbaum’s non-ekphrastic works, one early and one late, are in the collection: Paper Art, the third publication under her Triangular Press imprint, and Collage Book #6.

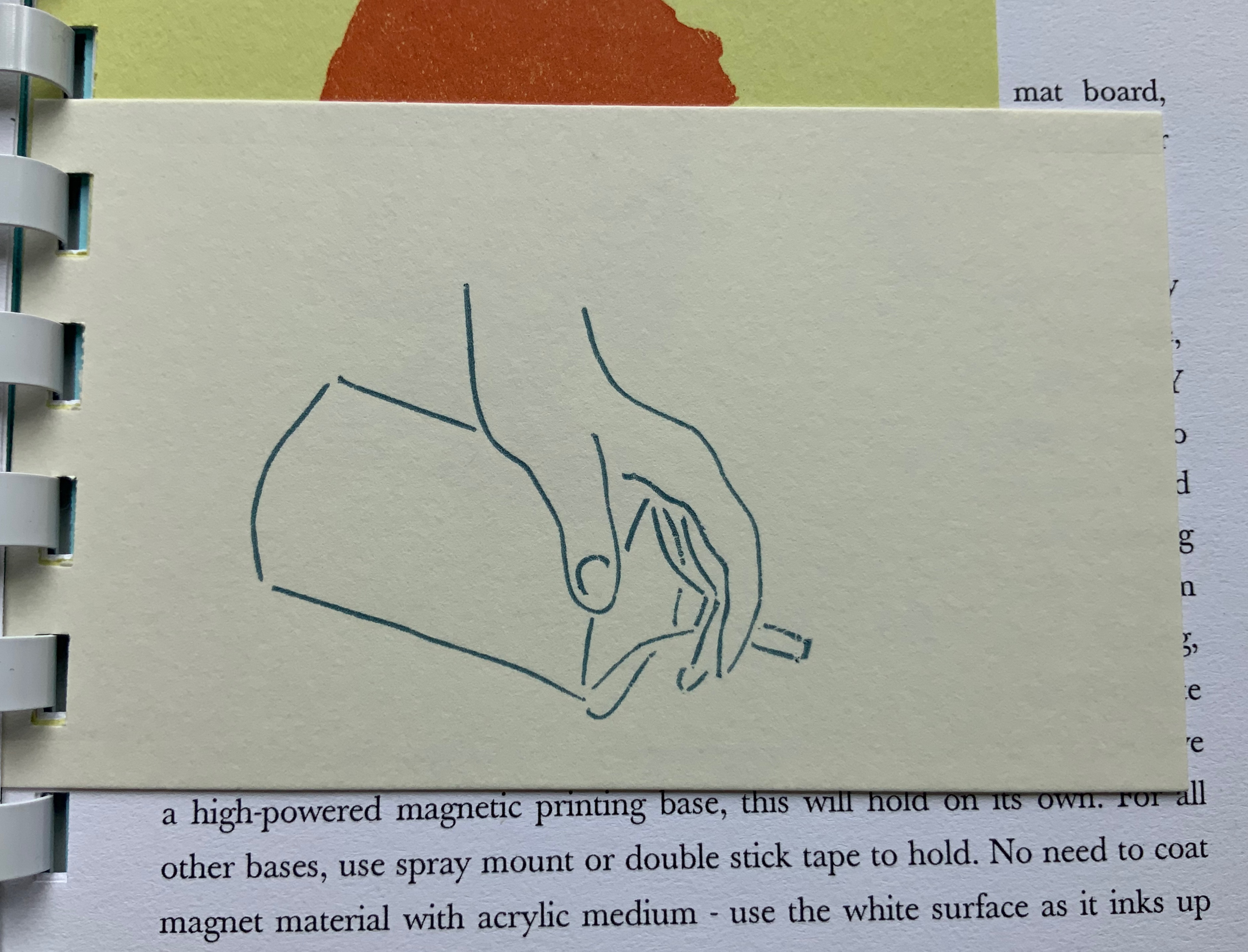

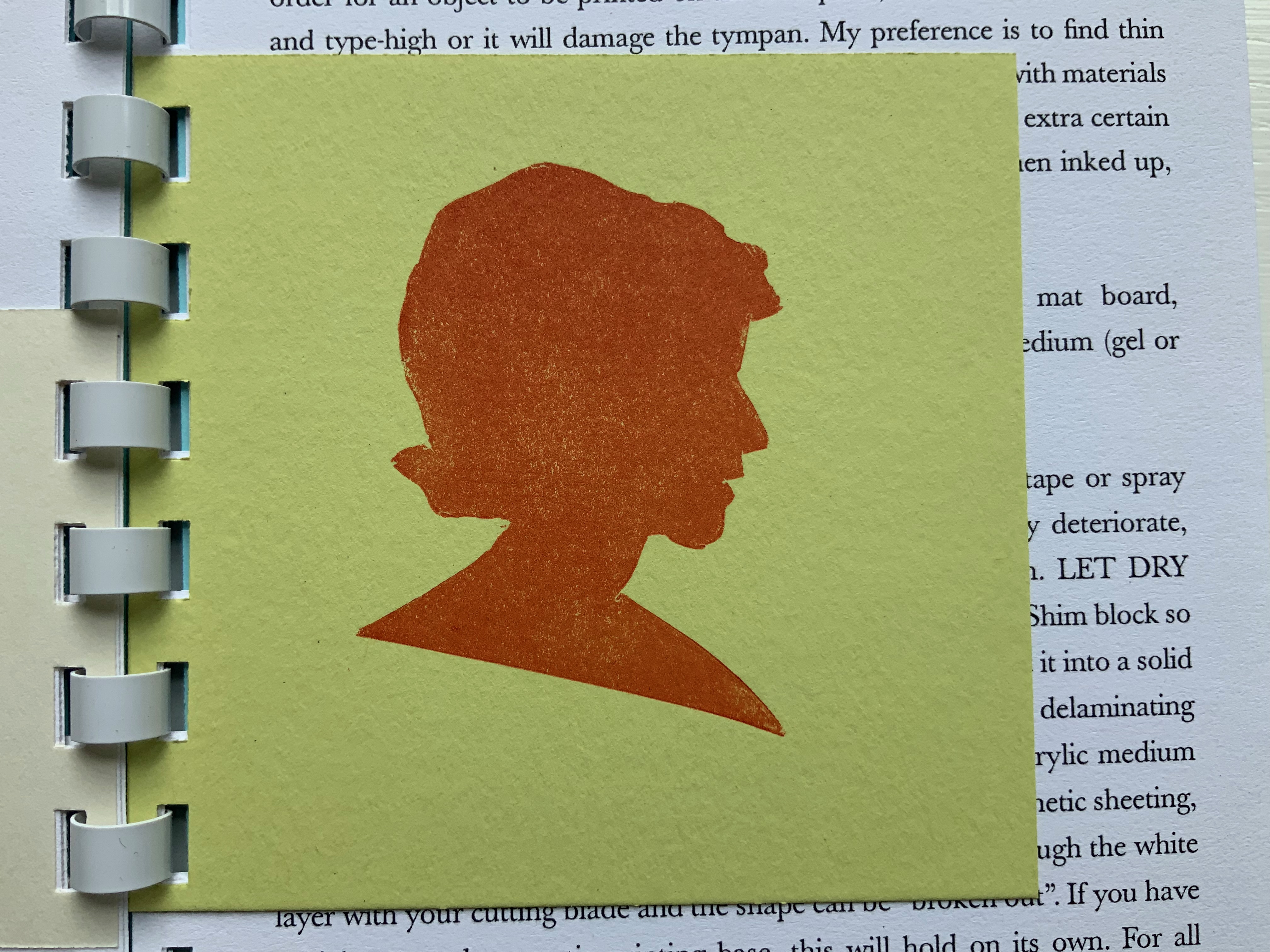

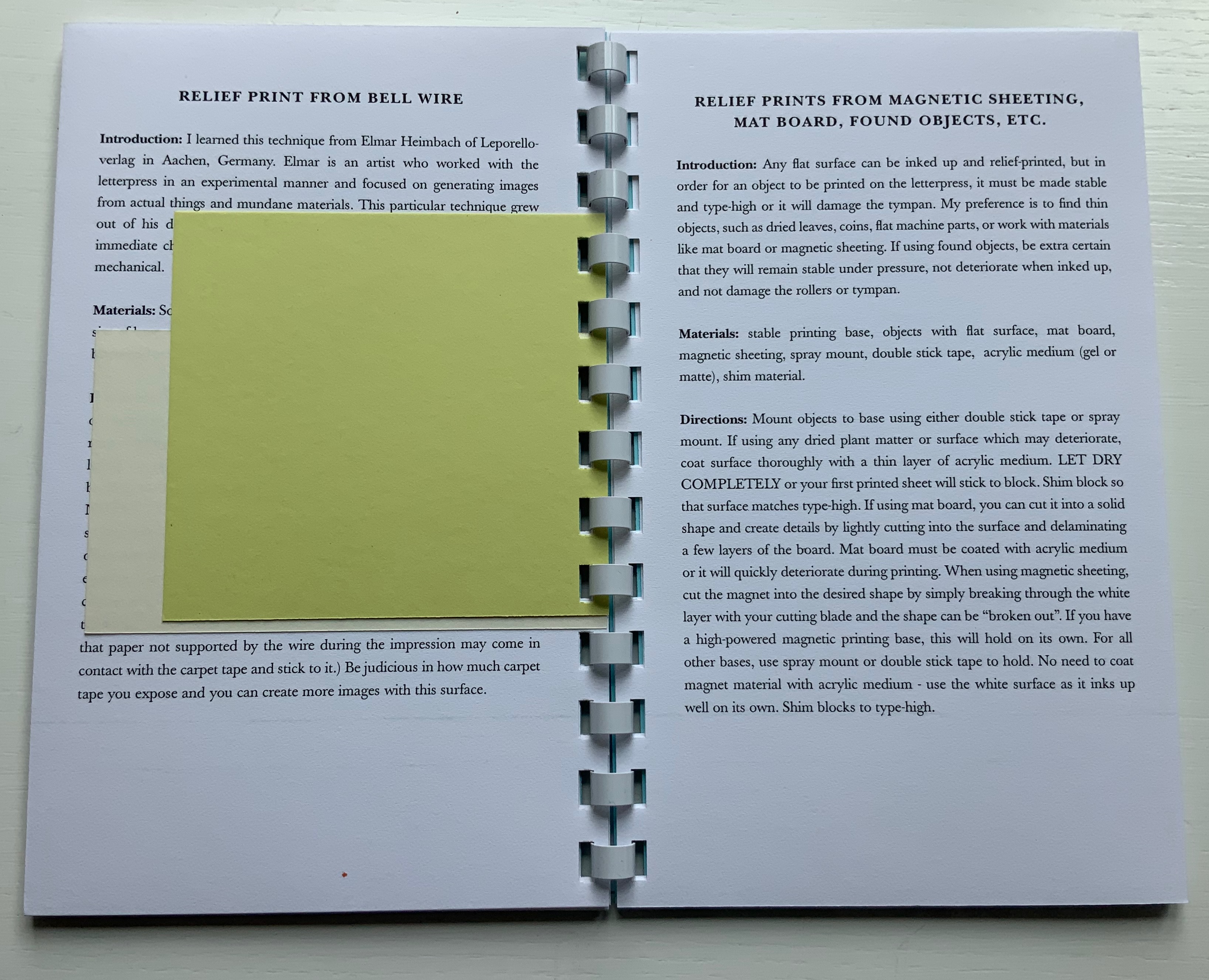

A Guide to Experimental Letterpress Techniques (2004)

A Guide to Experimental Letterpress Techniques (2004)

Barbara Tetenbaum

Spiral-bound. H190 X W123 mm, 16 unnumbered pages, Chinese fold. Acquired from the artist, 11 April 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

For a non-practitioner, instruction books like this encourage closer examination of artwork and an appreciation of the act of thinking with one’s hands.

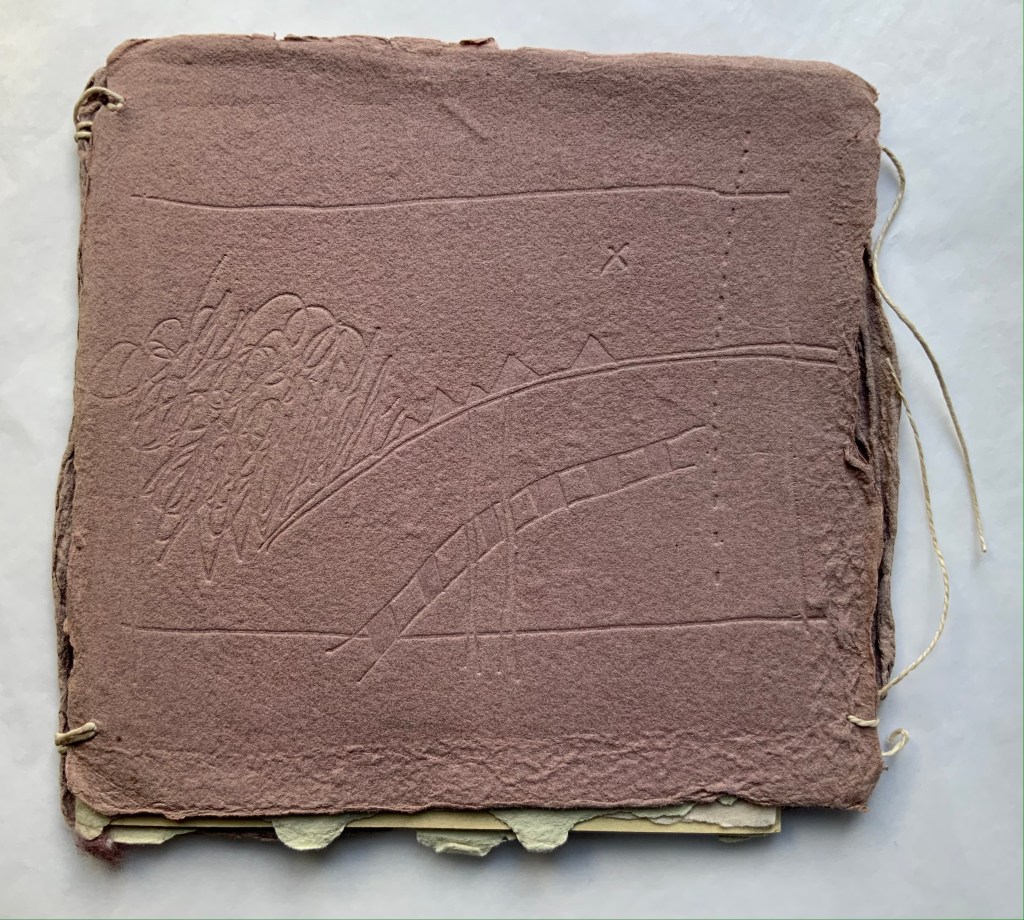

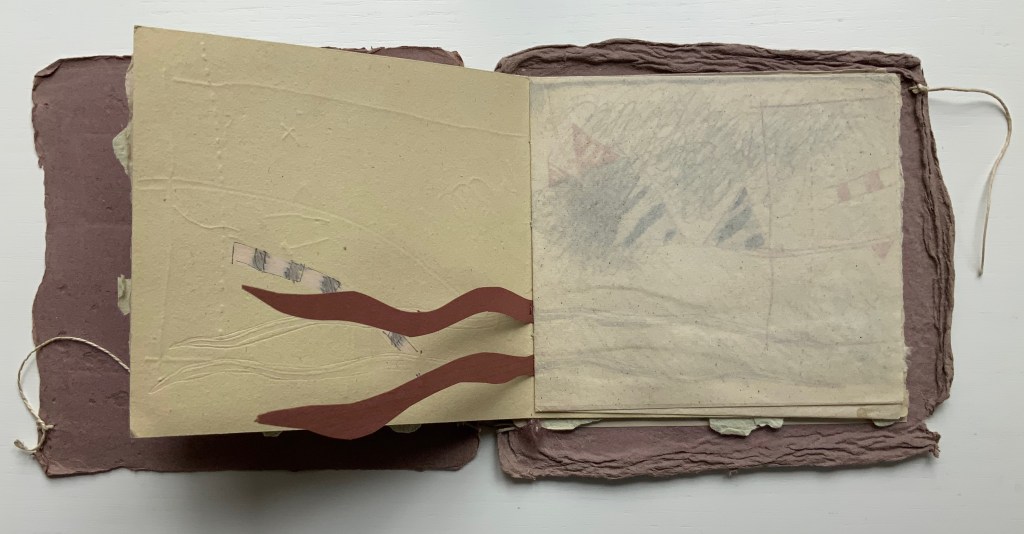

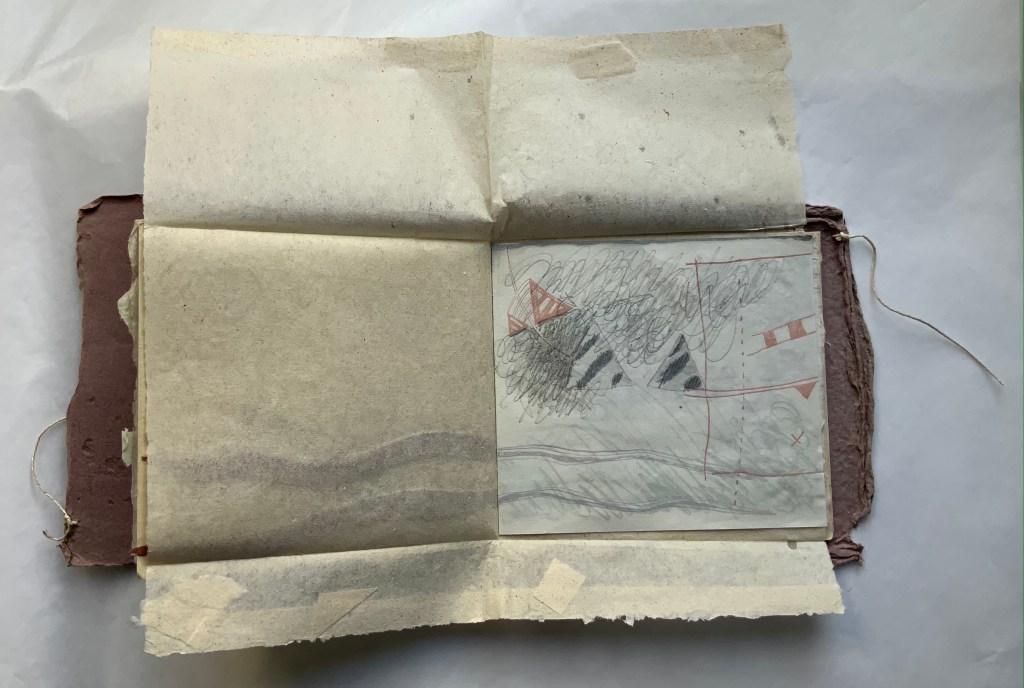

Paper Art (1980)

Paper Art (1980)

Barbara Tetenbaum

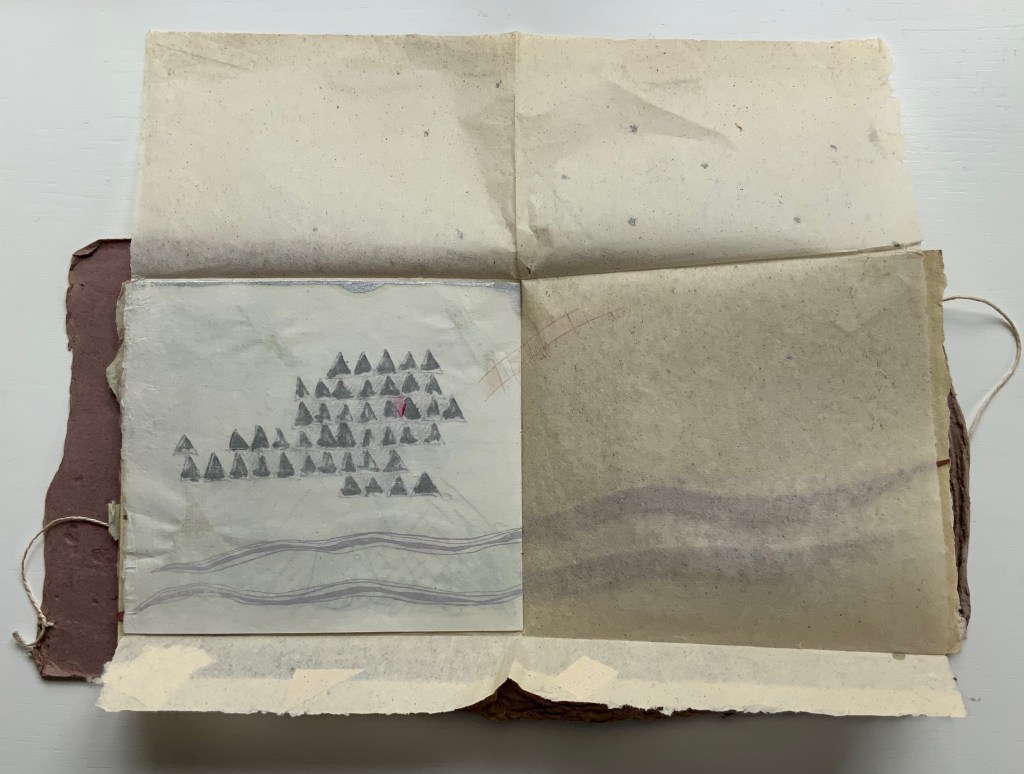

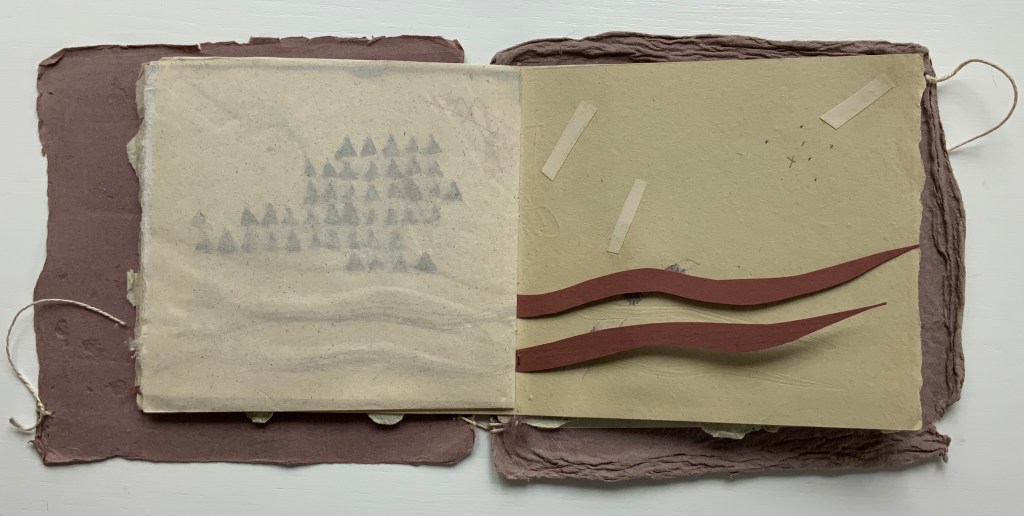

“Sequential picture plane / book-like object”. String-bound container: 165 x 165 mm; Object: H135 x W145 mm, 16 unnumbered pages and one fold-out leaf. Edition of 42. Acquired from Versand-Antiquariat Konrad von Agris, 22 January 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection. Permission to display from the artist.

“Sequential picture plane / book-like object” is the artist’s description of this work. The images come from cut paper and collage, relief printing, pen and ink, and washes. A narrative-like sequence develops involving two triangles and a community of triangles in a sort of landscape with a scribbled wilderness, parallel rivers or tracks, stars above, and moving to a boundaried community of triangles beneath a brownish wash and concluding with a double-page spread of the river or track images migrating to a final blank page.

Just as important are the binding, paper, folds and container. In its three-hole sewn deckle-edged cover, four more different kinds of paper make up the object and its images. The fold-out leaf, composed of the work’s most fragile paper, encloses the central four pages, which have the most intense concentration of images. The cutout paper rivers or tracks are attached with brown thread on either side of this fold-out leaf, which further cues us to be aware of parallel scenes. The range of papers from dense and thick to sheer and thin reminds us that parallels can present opposites: the couple and the collective, conflict and resolution, lost and found.

The container consists of the densest and darkest paper and, at one time, had a box-like shape held closed by string at its four corners. There is a barely perceptible hole in the upper left corner of the container’s cover.

The contrast between the sturdiness of the paper and the flimsiness of the string closure echoes the cut-out rivers or tracks, loosely attached by brown thread and embracing the central fold-out leaf enclosing the densest body of images. All of these material aspects suggest looking for the paradoxical in this “sequential picture plane / book-like object”.

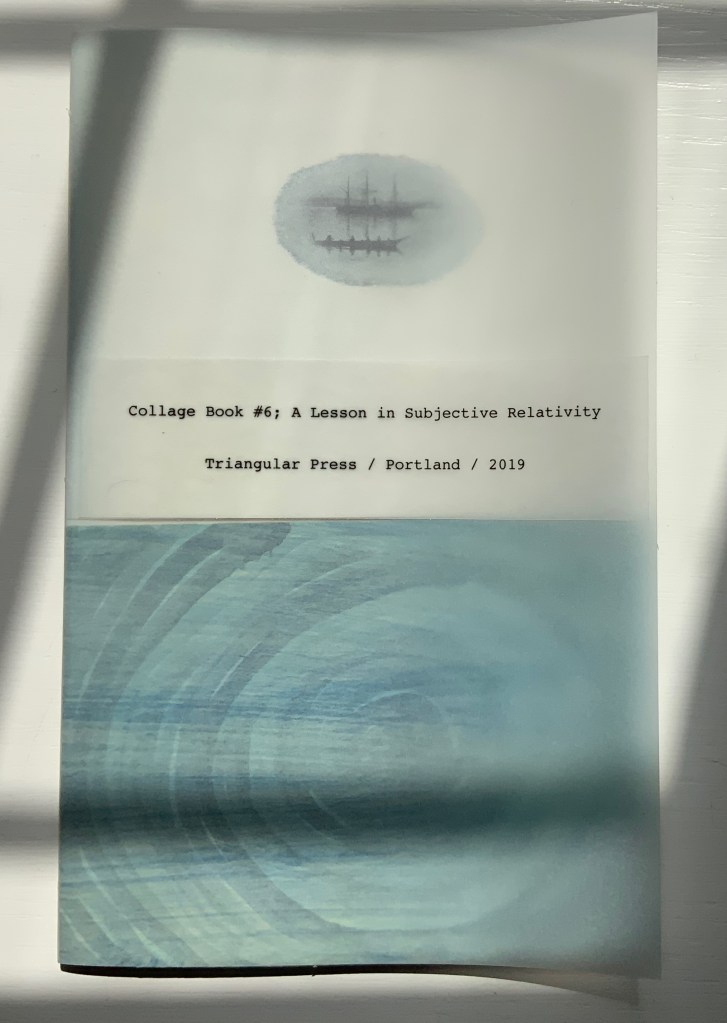

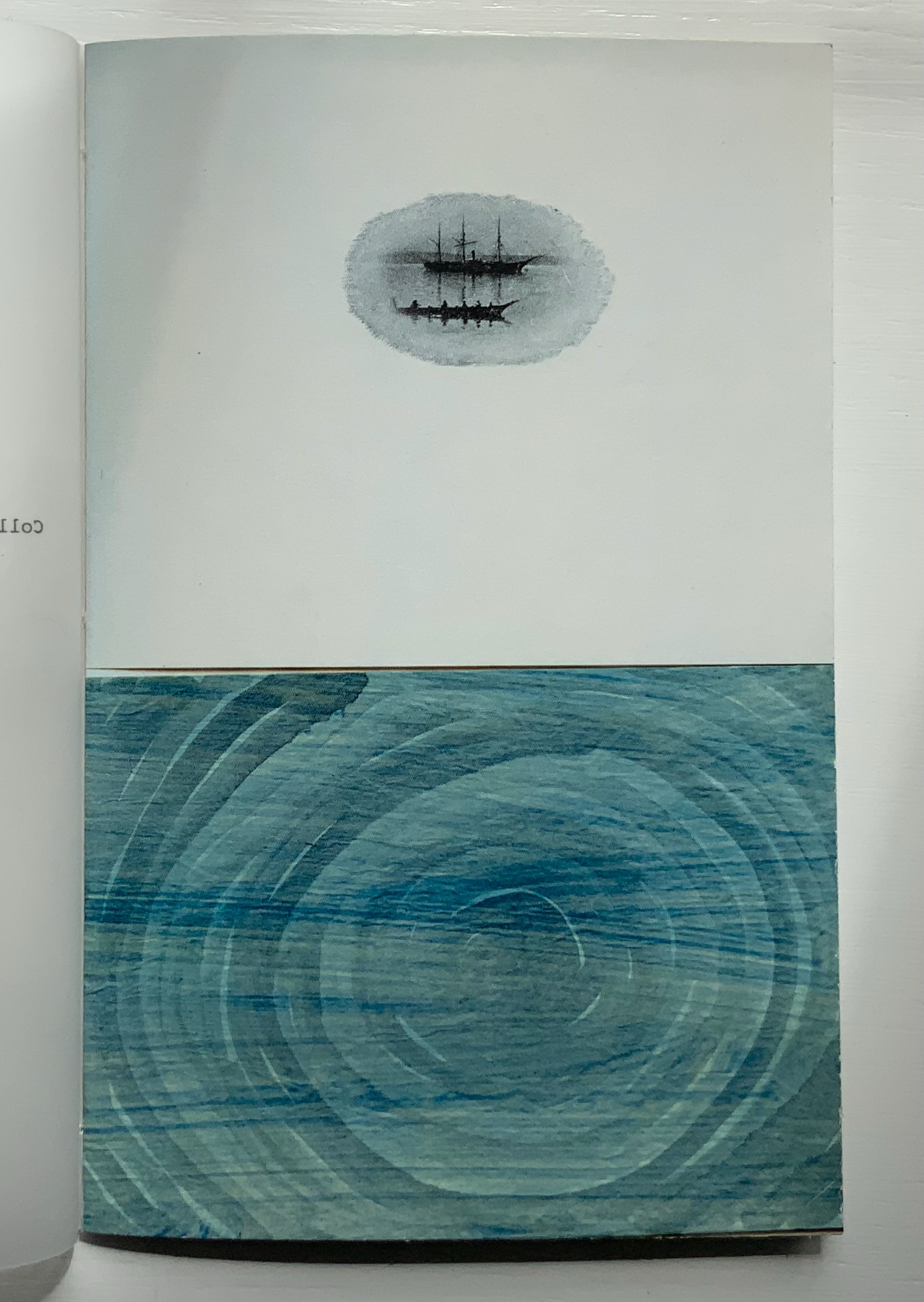

Collage Book #6: A Lesson in Subjective Relativity (2019)

Barbara Tetenbaum H190 x W120 mm, 32 unnumbered pages. Acquired from the artist, 11 April 2022.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Collage Book #6 also consists of sequential picture planes, but the sequence is not narrative. Rather it is one of visual association. In an oval shape, a three-masted schooner and longboat hover over a swirling blue abyss. The image is repeated on the following verso page, which faces a full-page bleed depicting a calving iceberg or glacier in blue and white. Again, the image is repeated on the following verso page, which faces an overdrawn black-and-white image of crops along a winding road leading to a steepled building at the edge of a lake. This image, too, repeats on the verso page, and its reddish-orange overdrawn lines or stakes echo the color in the facing photo of a textbook graphic representing exports. And on it goes until the final image on the back cover echoes the initial image on the front cover (see below).

The booklet’s structure recalls that of O’Ryan’s Belt: Eleven Poems: 1990-1991 by Michael Donaghy (see above). The spine consists of inward folds of the front and back covers. Internally (see below) two sets of signatures are sewn together through the inward-folded tabs.

Old-Time Film (2011)

Old-Time Film: Letterpress-printed Animated Short (2011)

Barbara Tetenbaum and Marilyn Zornado

Slotted cardboard envelope containing DVD and print. Acquired from Barbara Tetenbaum, 12 July 2019.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Artists’ description: DVD contents: Old-Time Film (2min, 58 sec) and “Behind-the-scenes” (2m, 48 sec). ; “Hand-set type, printer’s ornaments, and antique engravings come to life in this animated short created entirely through letterpress printing. Includes behind-the scenes showing the letterpress animation techniques on the Vandercook. Tetenbaum and Zornado have dubbed their process of combining letterpress techniques and animation ‘Vander-Mation.’ In this production using Vander-Mation shoes tap, sheep jump an ornamental enclosure, and words expand and contract in time with the music.

Postscript

Tetenbaum has provided another way to experience the Cather Projects: The Slow Read (2018). Take a wander through that site, composed of an introductory page to “a public literary and fine art project conceived and produced by Barbara Tetenbaum honoring the centenary of the publication of Willa Cather’s novel My Ántonia“, a set of seventy-four links to the daily scheduled readings, a blog section, a “concordance” that is more an unfolding of the installation and artist’s book than a listing of words and phrases against page references, and finally a portfolio of artwork by Tetenbaum.

Further Reading

“… in medias res … Barbara Tetenbaum“. 18 August 2013. Bookmarking Book Art.

“‘Machines’ by Michael Donaghy and Two Artists’ Books“. 12 October 2020 Books On Books Collection.

Michaelis, Catherine Alice. 20 March 2021. “Elemental Impressions“. Artist’s Books Unshelved. Bainbridge Island Museum of Art. Accessed 22 March 2021. Video presentation and discussion of Diagram of Wind.

King, Nathalie. “Reading the Literary Text as ‘Art in Space’: Barbara Tetenbaum’s My Ántonia,” The Artist’s Yearbook, 2014-2015. Bristol: Impact Press, pp. 95-99.

Paterson, Don. 2014. Smith – A Readers Guide to the Poetry of Michael Donaghy. London: Pan Macmillan.

Schneider, Uta. “Turning the Page”, pp. 18-28 in Tetenbaum, Barbara, James Carmin, and Uta Schneider. 2005. Half-life: 25 years of books by Barbara Tetenbaum & Triangular Press. Portland, OR: Triangular Press. Three key works not in the collection are described in Half-Life. The first would be an edition from the Gymnopaedia series, based on the artist’s response to Erik Satie’s musical compositions of the same name. The second would be Tetenbaum’s collaboration with Julie Chen that resulted in a powerfully moving work: Ode to a Grand Staircase (for Four Hands) (2001). The third key work returns to Donaghy’s poetry with the clear aim to incorporate sound in book art: Black Ice and Rain: Psalms 6.6 (2002). In the absence of the work itself, Uta Schneider’s description of it in Half-Life is as close as one can come to experiencing it.

Tetenbaum, Barbara. 14 June 2021. “My Ántonia at Six Pages a Day: The Slow Read Project”, presentation for the panel “Willa Cather and Her Readers”, organized by the Willa Cather Foundation for the American Literature Association Virtual Panel. Accessed 19 July 2021.

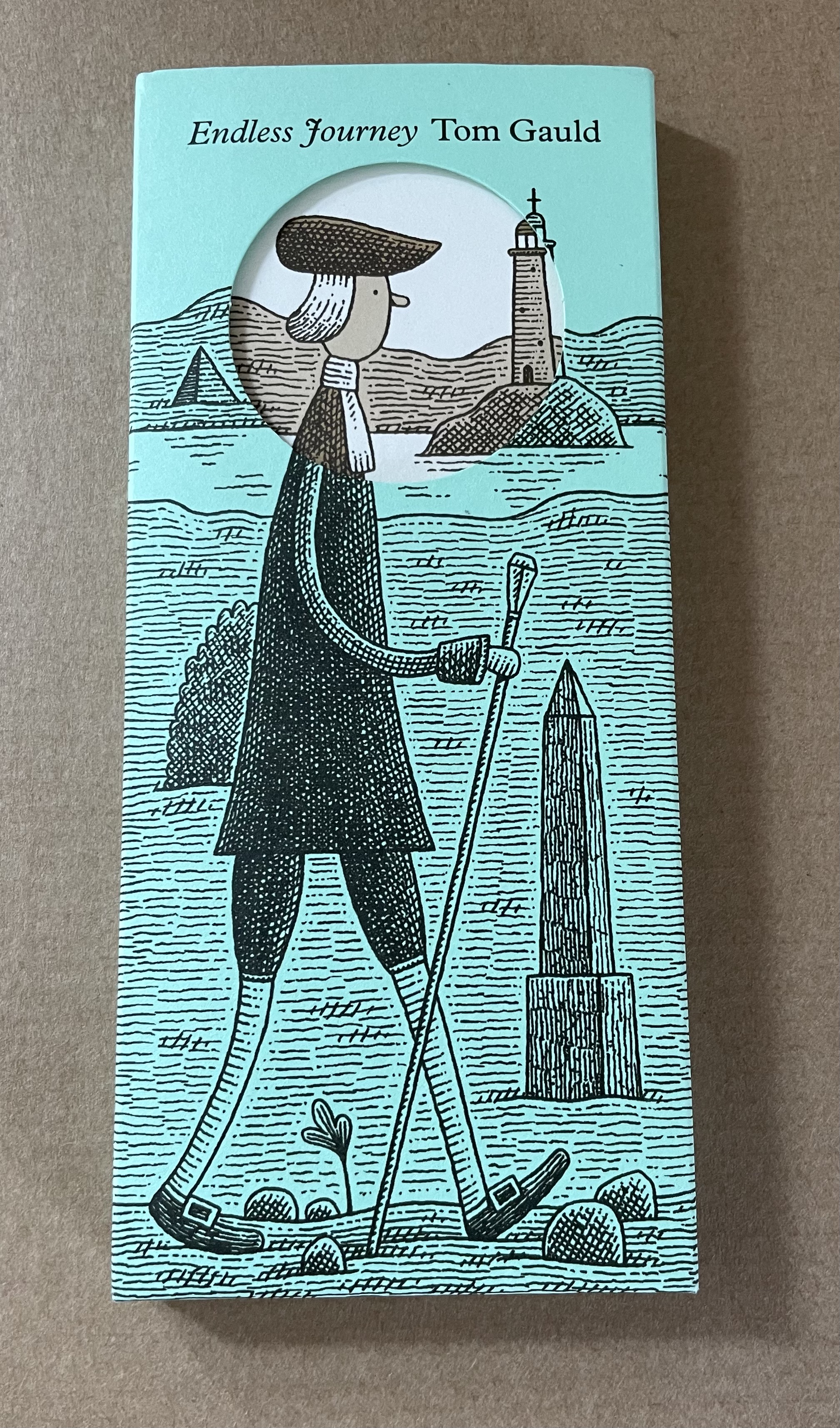

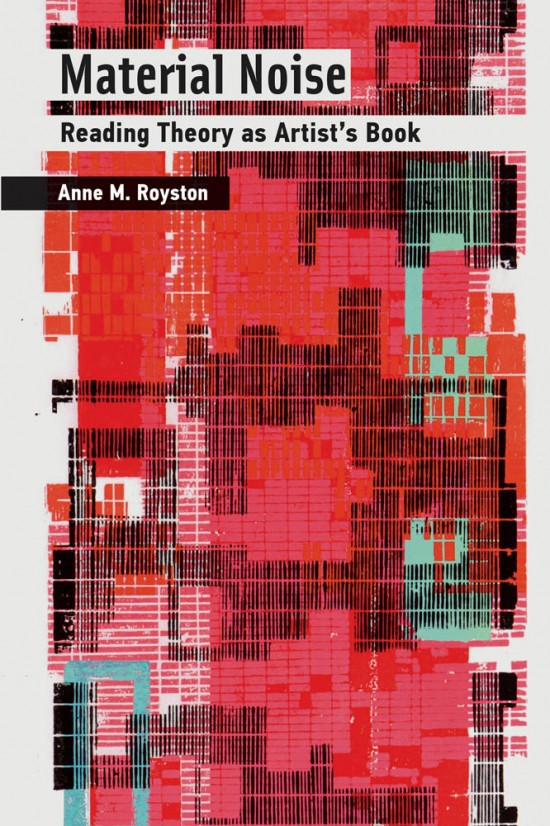

Four Proposals for Reading (2015)

Four Proposals for Reading (2015)

Seager Gray Gallery and Barb Tetenbaum (ed.)

Perfect bound book. 203 x 203 mm. [44] pages. Acquired from Barb Tetenbaum, 2019.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.