With the exception of Unpacking my Library and Between the Sheets, Spector’s works in the Books On Books Collection fall into the category of ephemera. More than most book artists’ ephemera such as invitations, broadsides and the like, however, Buzz Spector’s ephemera have that self-reflexiveness so characteristic of book art.

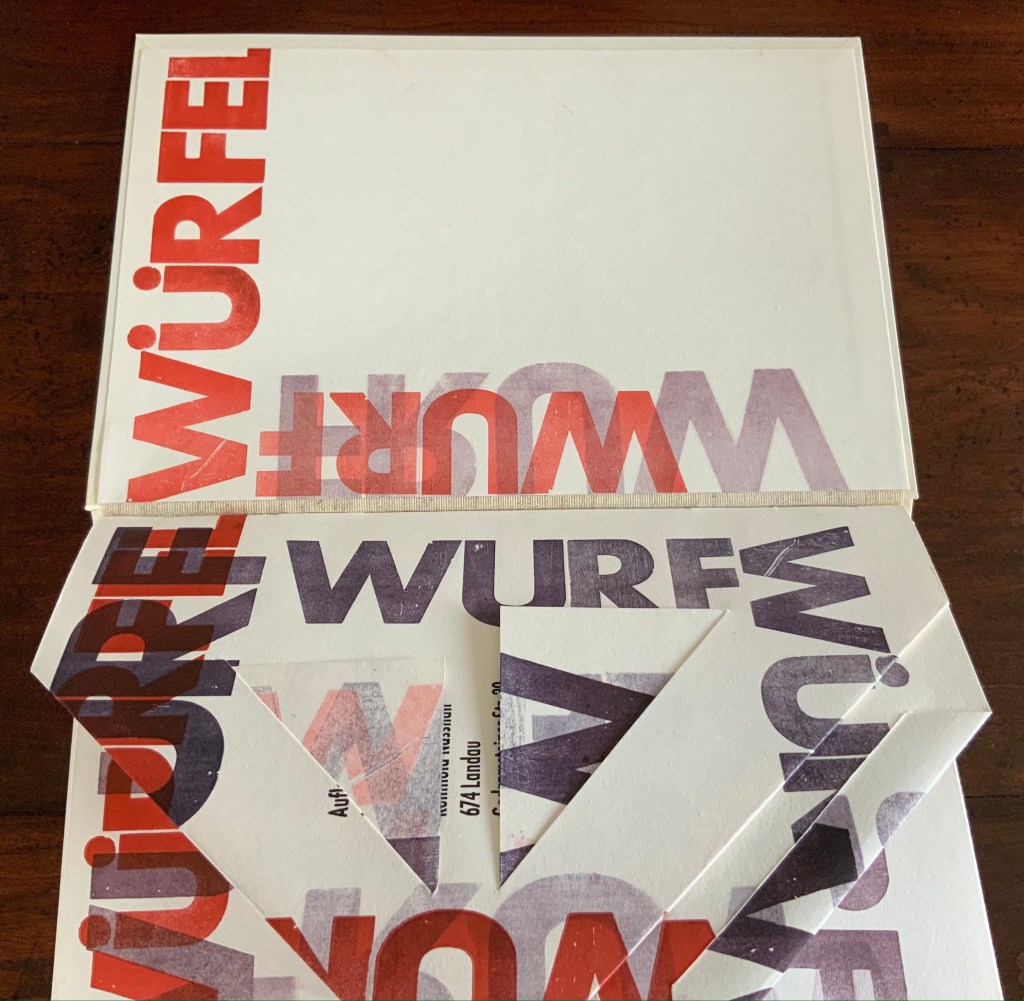

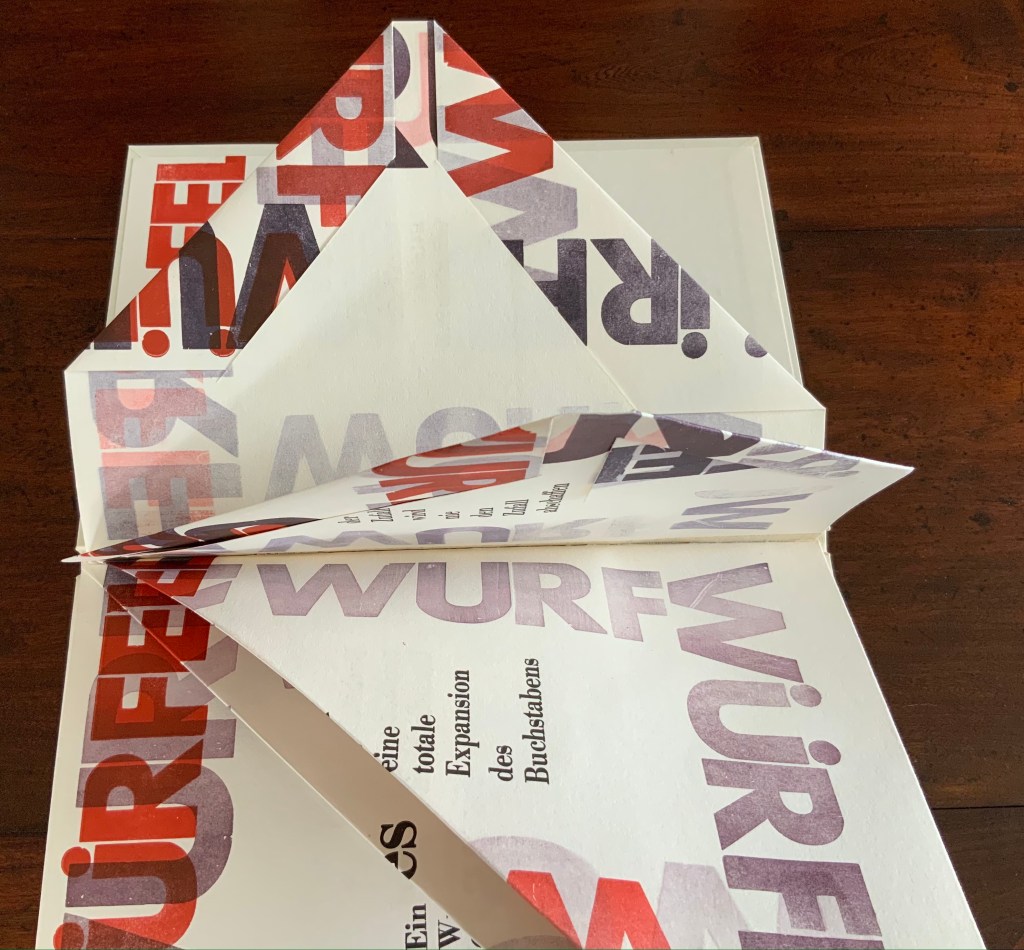

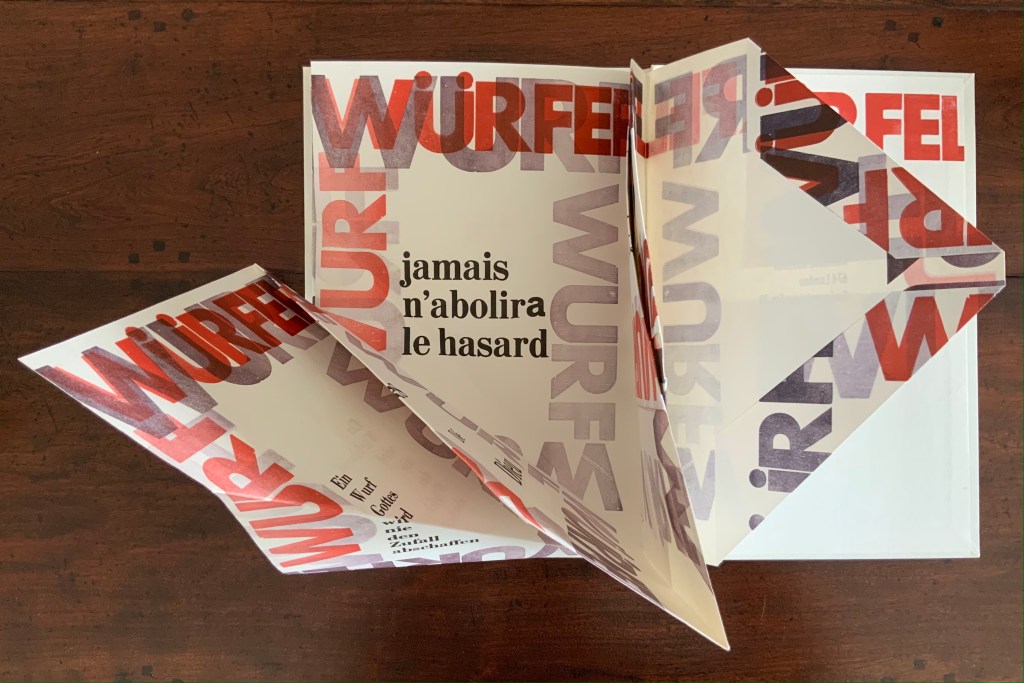

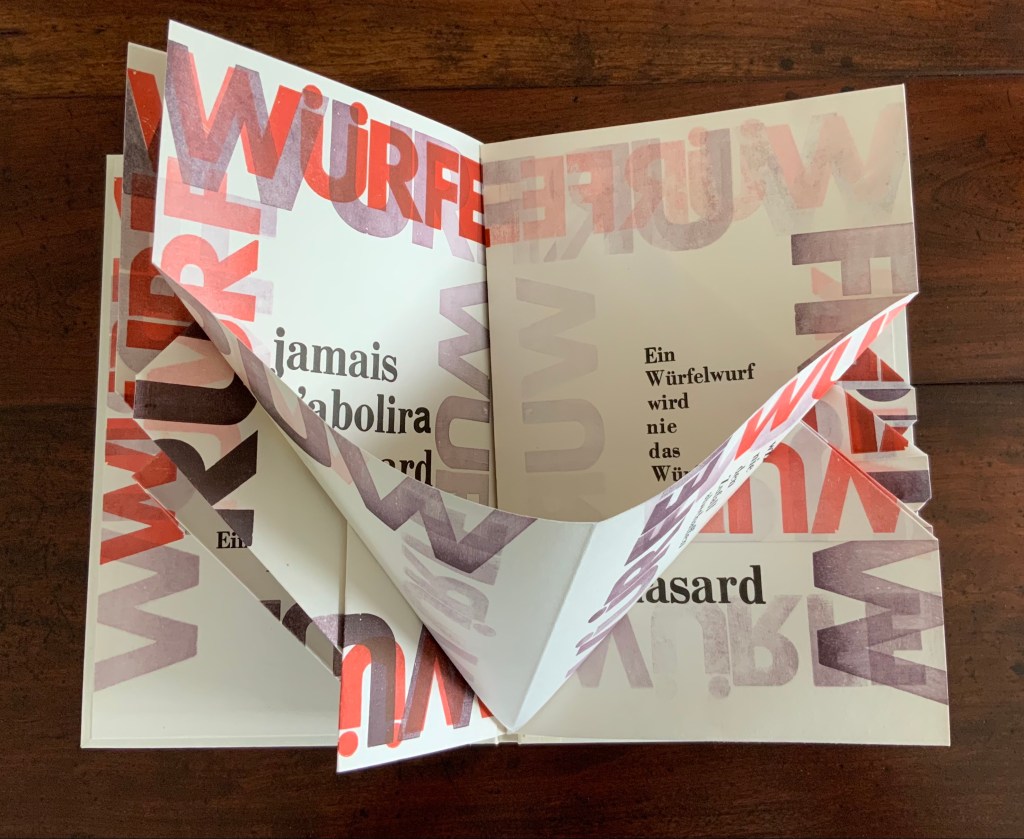

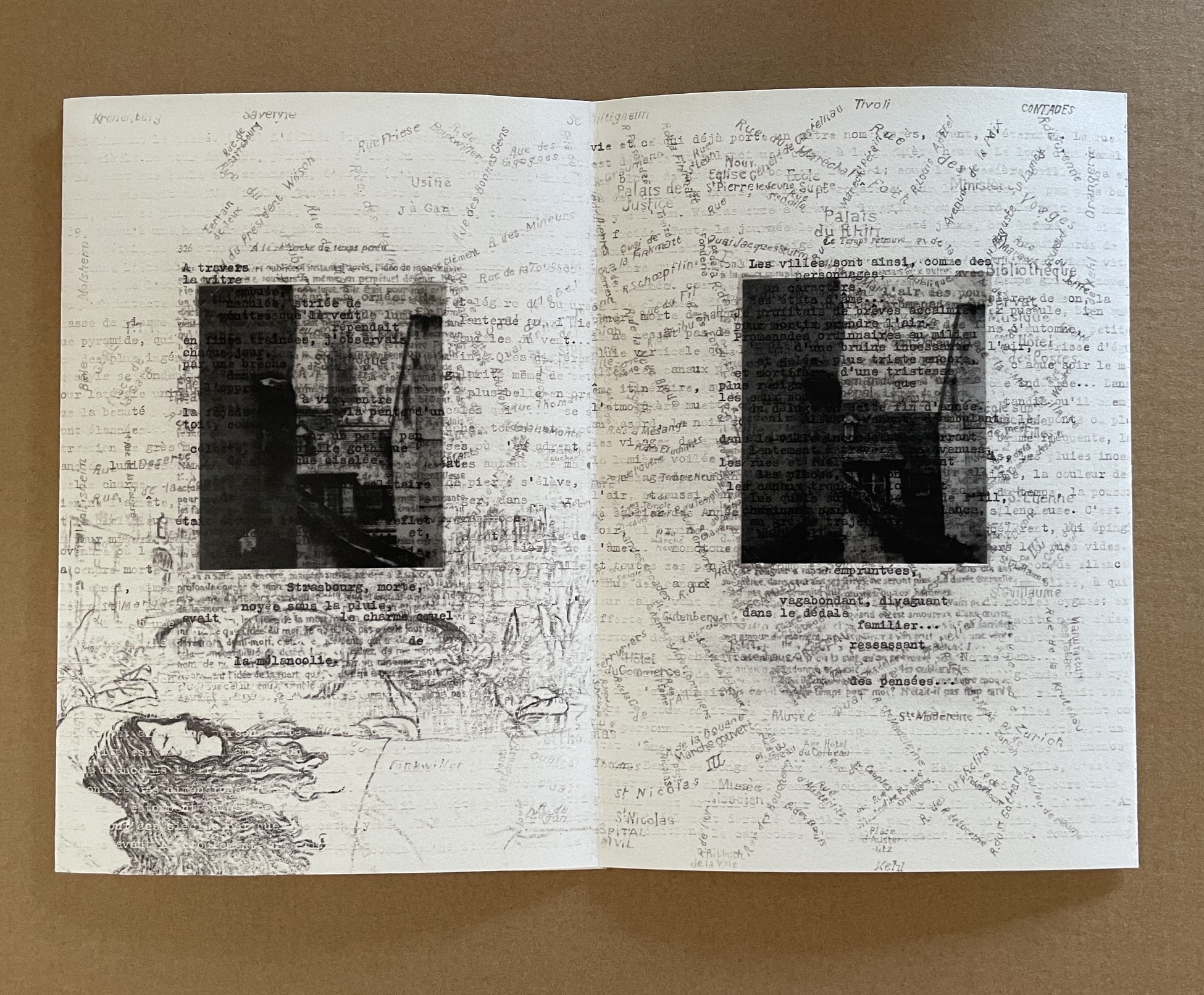

The Book Made Art (1986)

The Book Made Art: A Selection of Contemporary Artists’ Books, exhibited in the Joseph Regenstein Library, The University of Chicago, February through April 1986

Curated and edited by Jeffrey Abt; catalogue designed by Buzz Spector.

Saddle-stitched, staples; H200 x W200 mm.

Chicago: University of Chicago Library, 1986.

Artist, curator and historian Jeffrey Abt wrote that the “irresistible” idea of placing an exhibition of artists’ books alongside the University of Chicago Library’s collection “broadly representative of the history of the book” started with a visit to famed art dealer Tony Zwicker‘s studio. It was also, however, almost as if he were taking a cue from this statement by artist-printers Betsy Davids and Jim Petrillo just the year before:

A representative collection of artists’ books often does not seem visually remarkable in a gallery, where a wide range of visual experience is the norm. The same collection, installed in a library or bookstore, can seem visually startling almost beyond the limits of decorum. — “The Artist as Book Printer: Four Short Courses”).

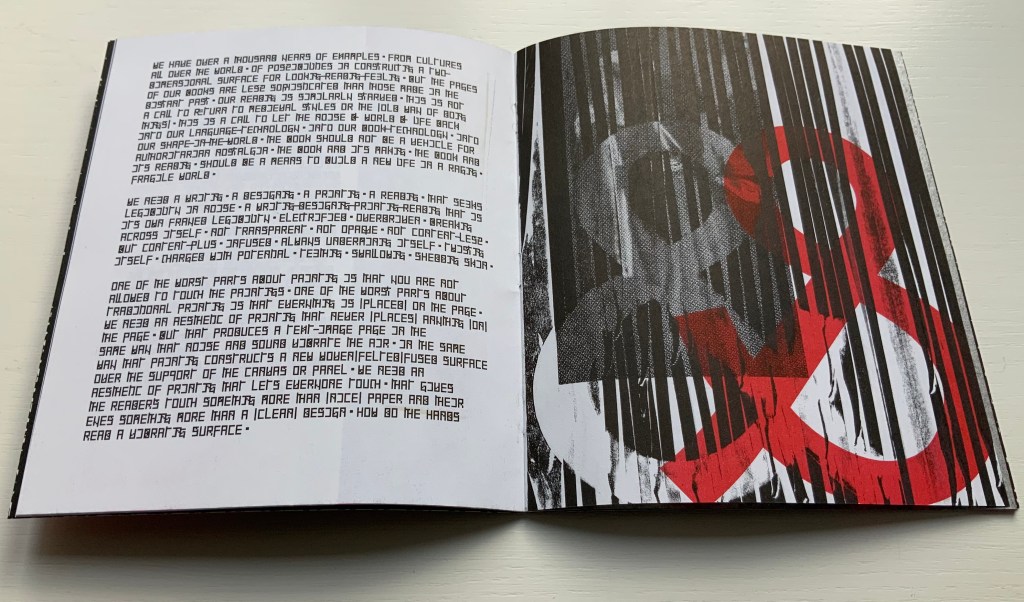

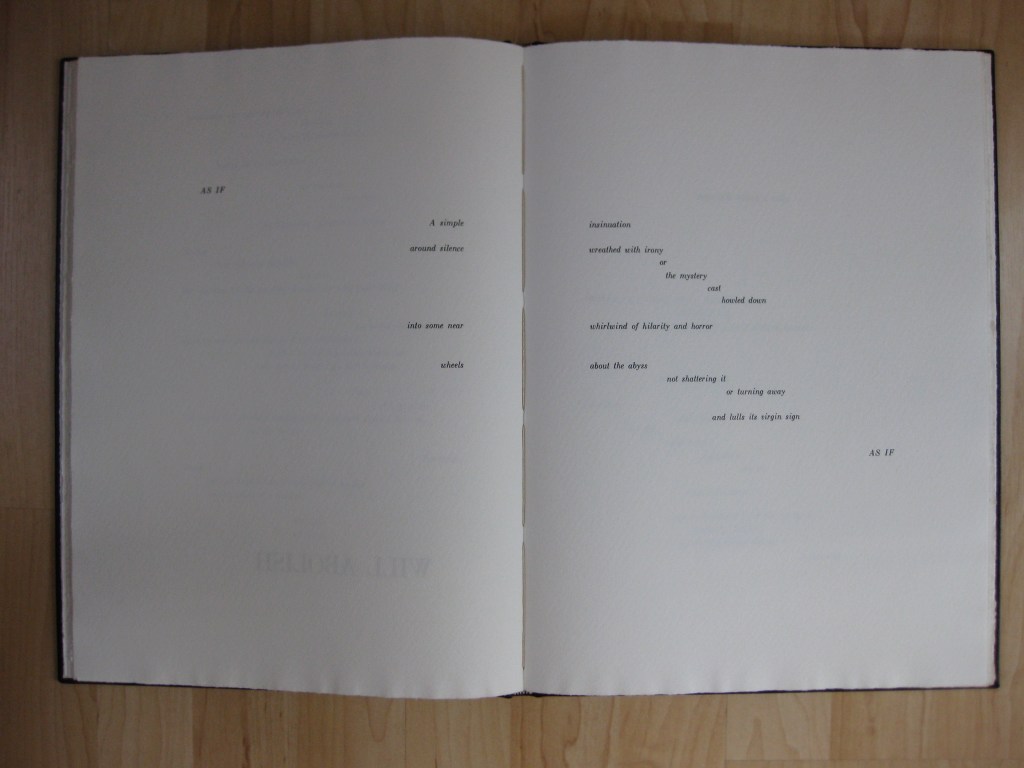

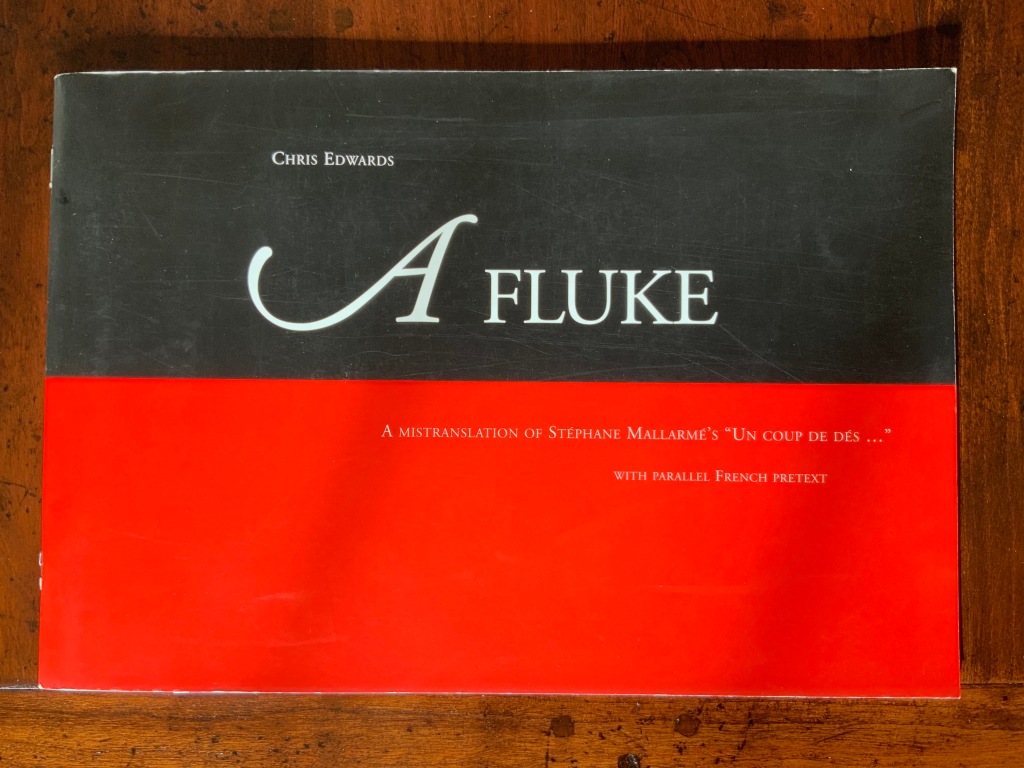

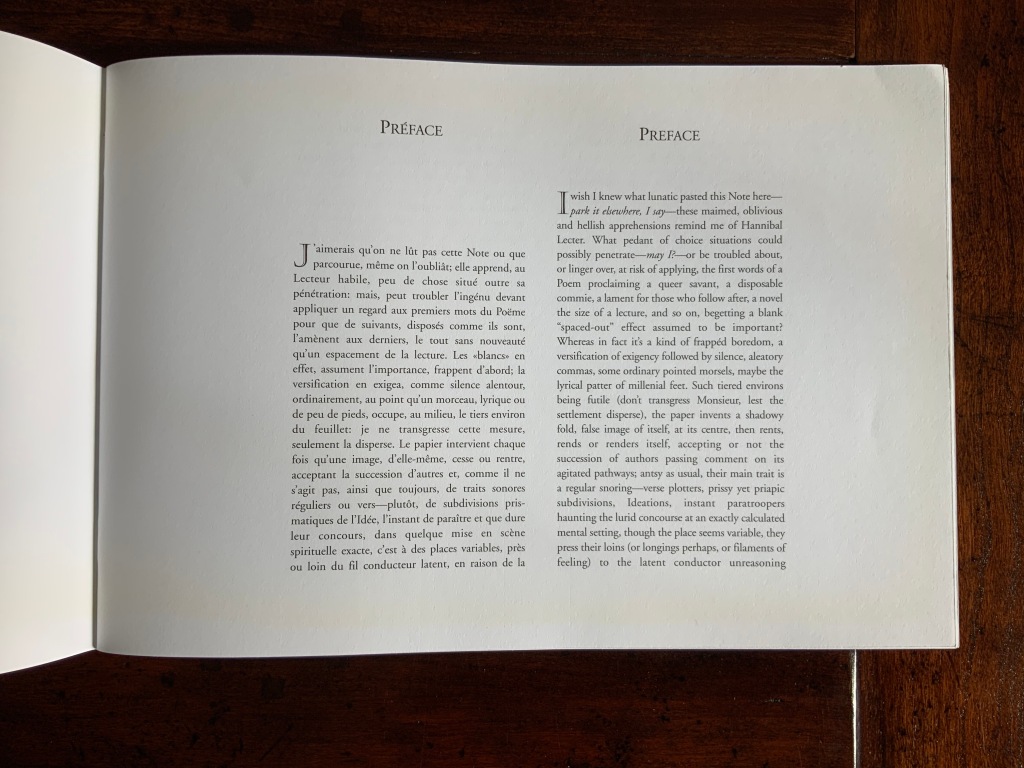

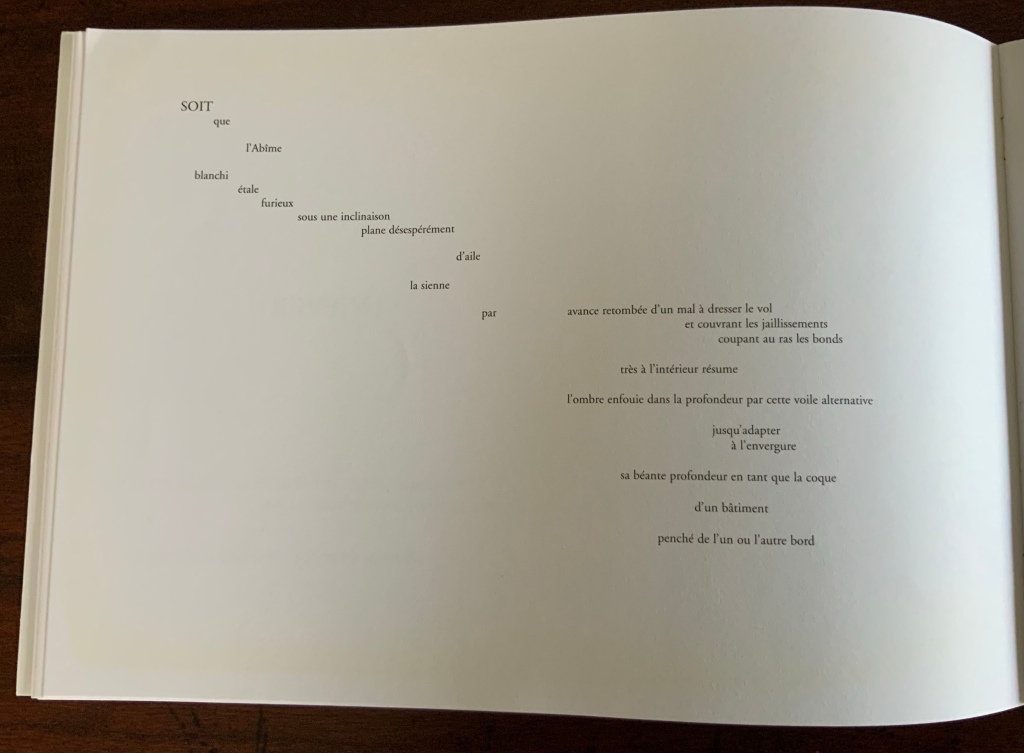

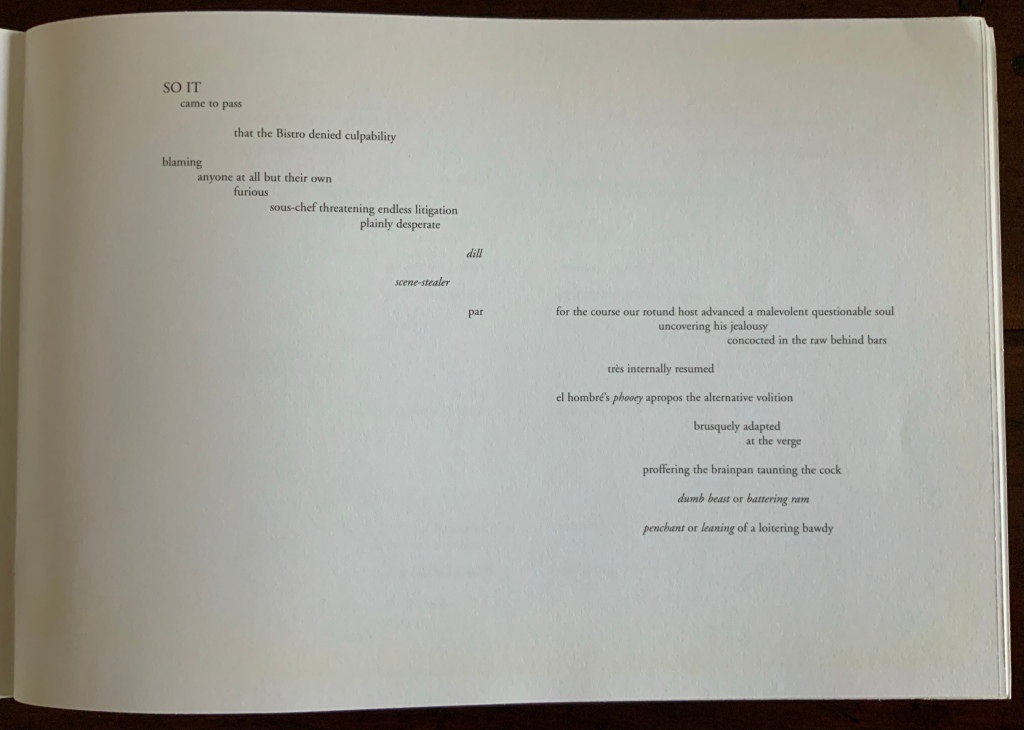

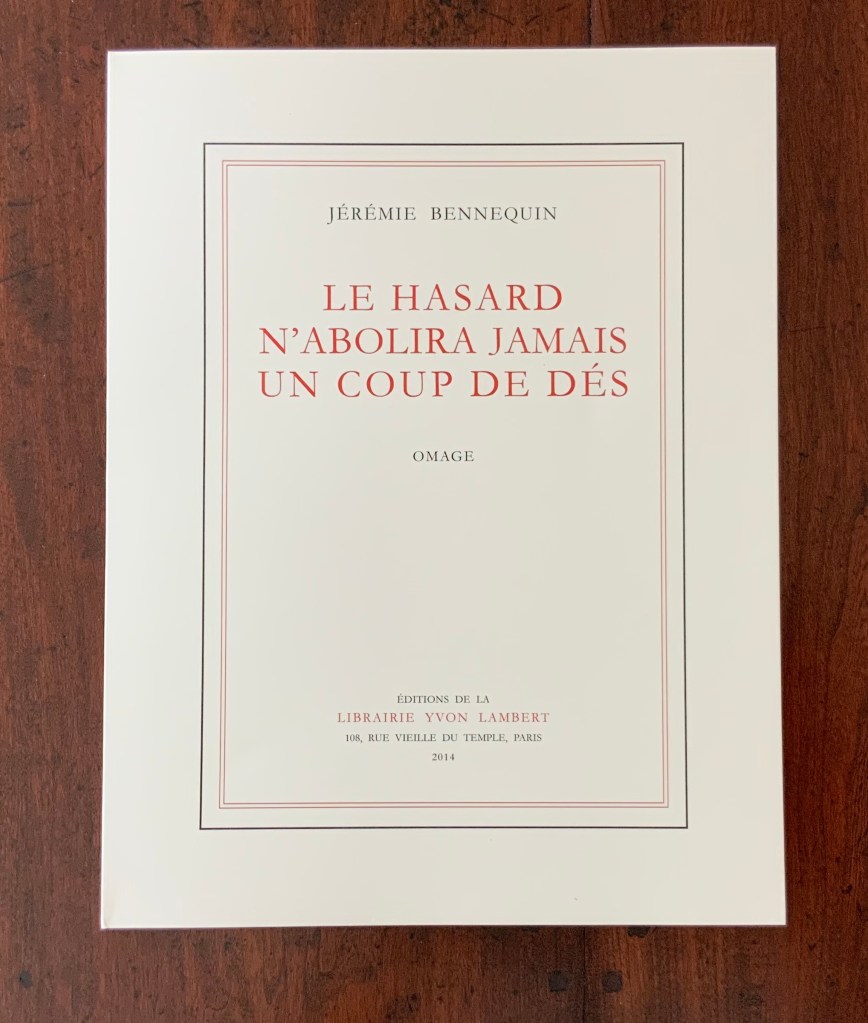

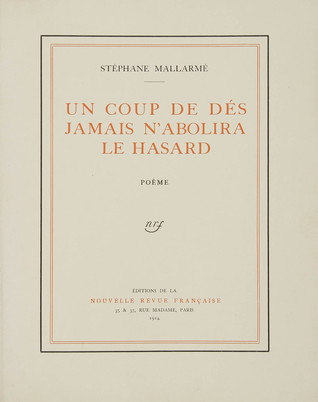

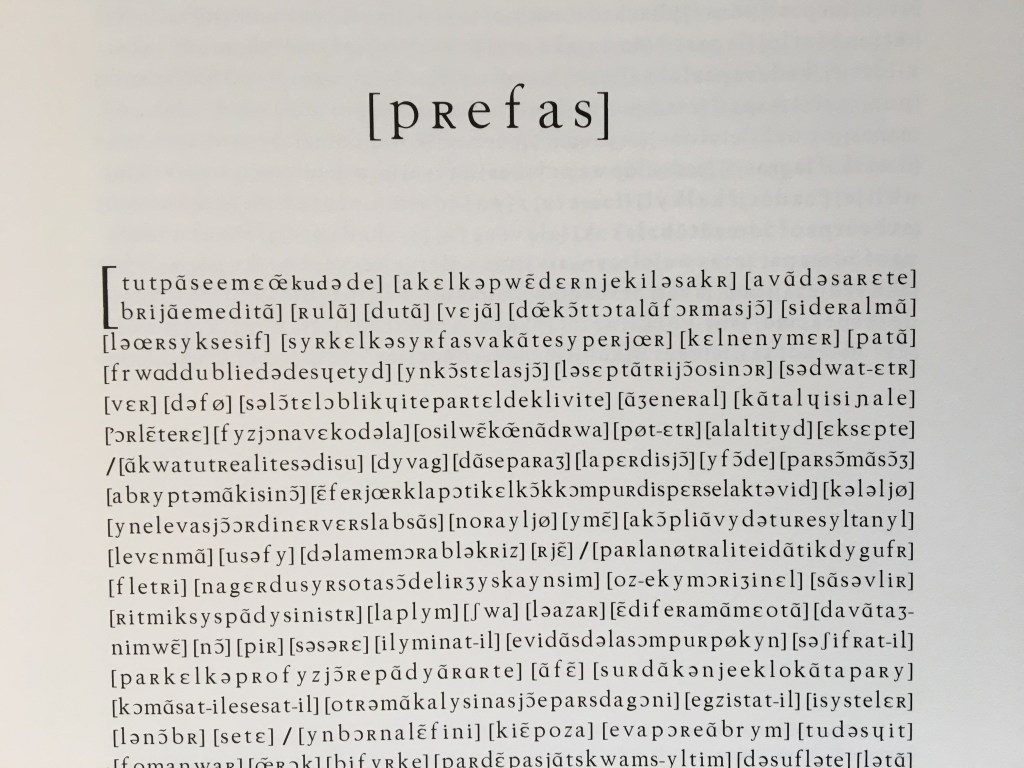

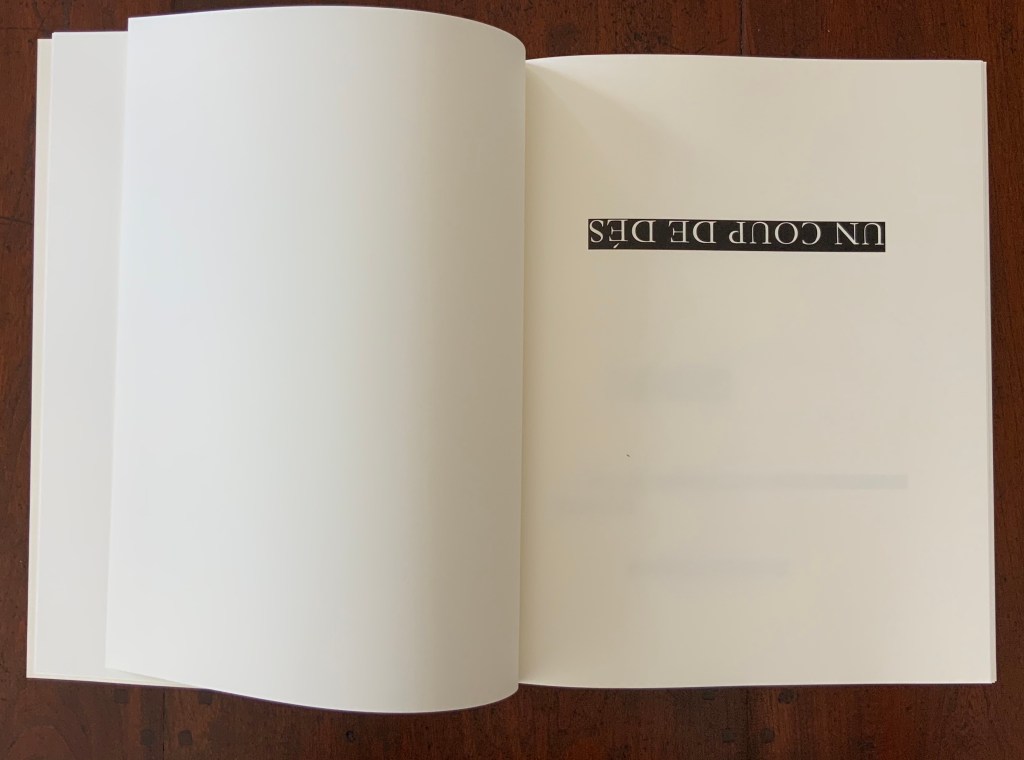

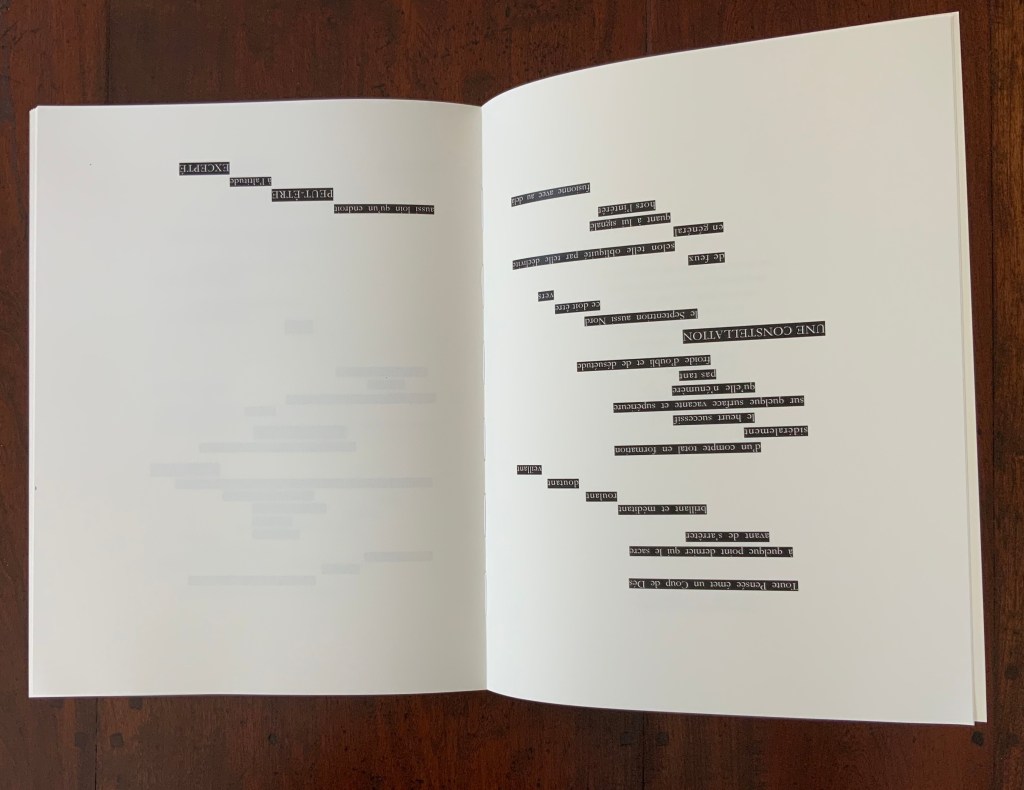

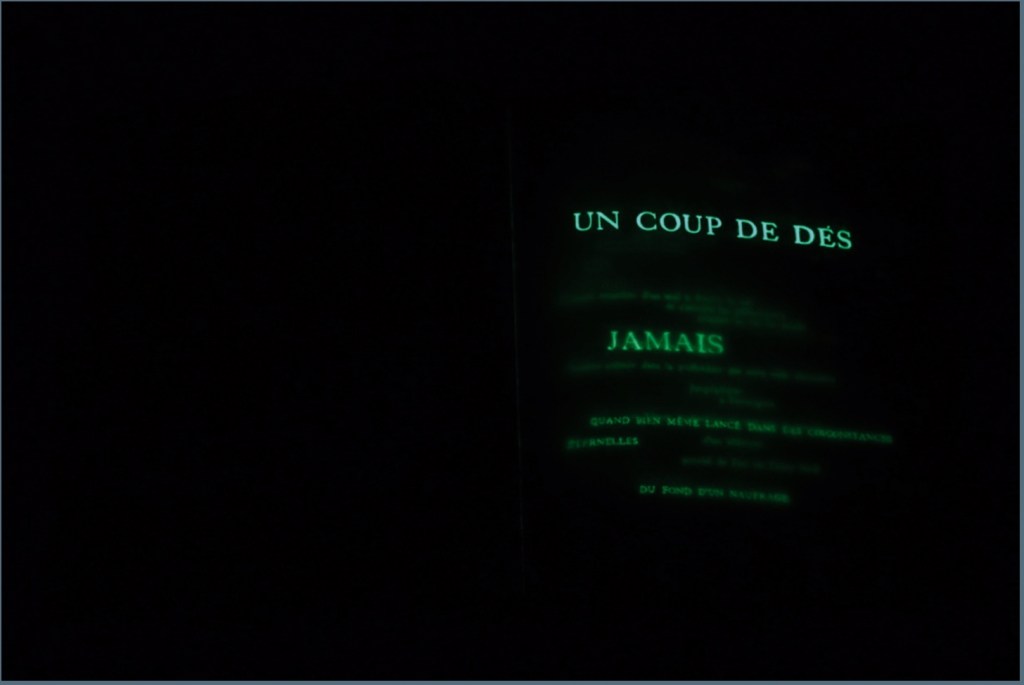

While Abt’s introductory essay rings the historical changes on the roots of book art — once there was Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard, but before Mallarmé, there was William Blake — the works included and the catalogue’s design ring some chimes of their own about book art. One way or another, all book art self-consciously draws attention to some particularly bookish element. For the most part, the 49 works listed in this catalogue ring true. The catalogue’s design itself, however, not only chimes to that notion of self-reflexiveness but also to wider notions about the nature of book art within contemporary art.

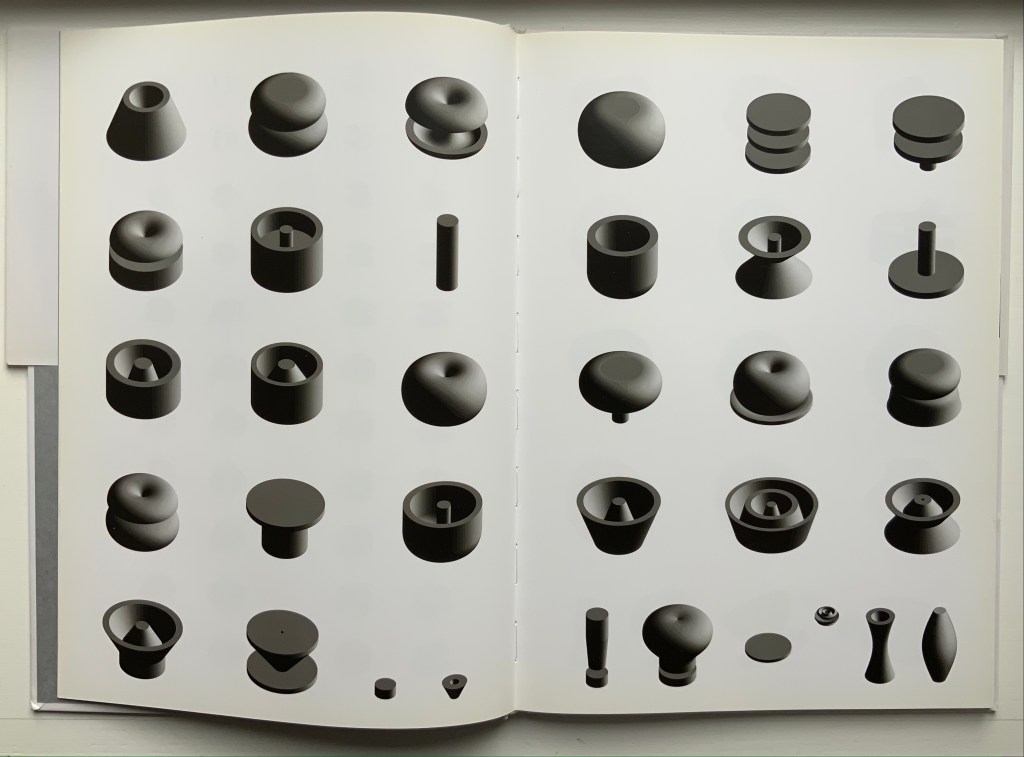

Not long after this exhibition, Spector wrote of “the language of the book” and all its parts — pages, signatures, cover, letter forms and their placement on the page, etc. — as having a syntax (“Going Over the Books”). With its pencil-circled numbers, alignment guides, pastedowns and other designer’s marks appearing throughout — as if a printer’s devil had run amok and let the marked-up proofs go to press unchanged — the catalogue draws attention to that syntax, the underlying processes of bookmaking and, therefore, this object’s “bookness”. The colophon’s note initialed by Jeffrey Abt to Buzz Spector and “pasted” on the last page jokingly rings the self-reflexive chime of the markings throughout the catalogue.

The second chime comes in the catalogue’s verbal and visual punning. Like book art, punning is self-reflexive, words playing on words. The title ”the book made art” can be read with different meanings: “the book made into art”, “art that is bookish” and so on. The catalogue’s trim and two-dimensional representation of three-dimensions create the visual pun of a glass or white cube. The verbal and visual puns also play with Abt’s “irresistible” context. Here in the Joseph Regenstein Library was an exhibition catalogue, teasing the viewer with a reminder that vitrines separated them from the bookworks. Reviewing two other exhibitions of book art, Spector elaborated explicitly on his visual tongue-in-cheek irony:

The dilemma in staging exhibitions of books as art objects is the denial of access to the work that conservation necessarily demands. … and it is a more than passing irony that implications of hermeticism and elitism should surround books shown to a public using the library as a means of gaining access to texts. — “Art Readings”.

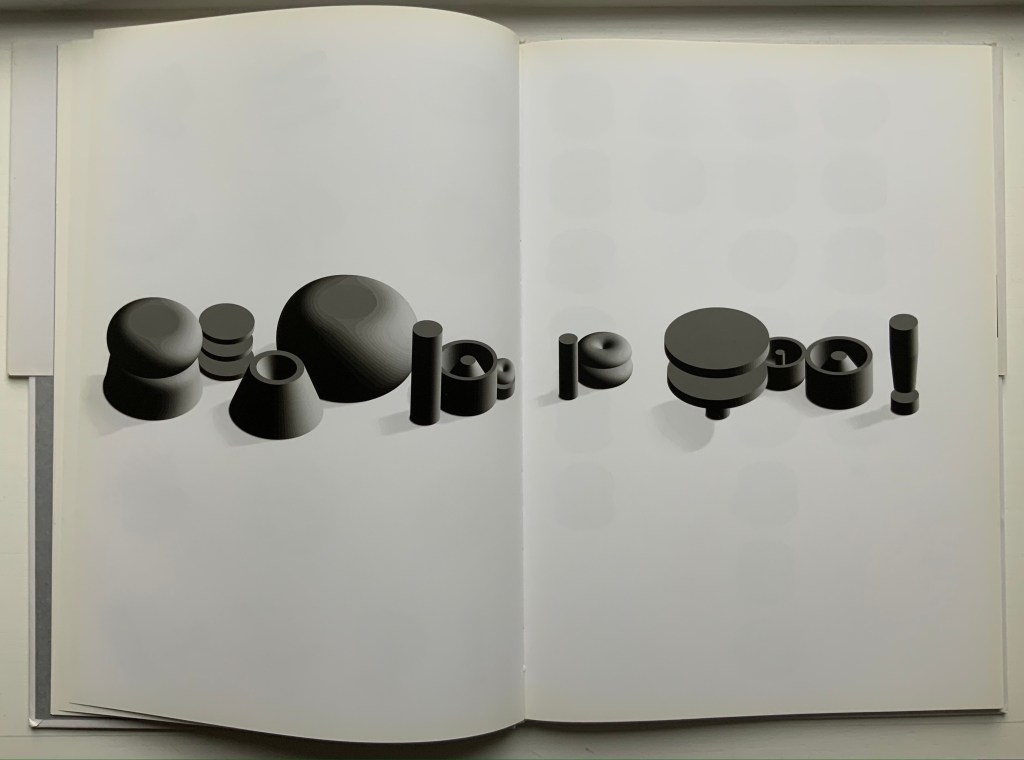

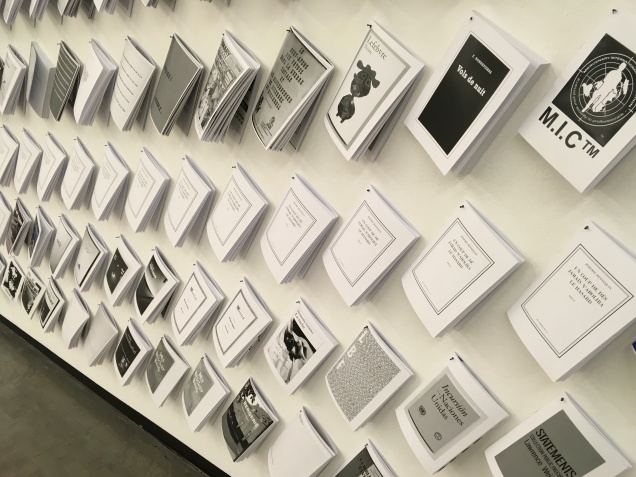

The catalogue also teases with its title and design by suggesting that once books have been placed on display like this, the setting is no longer a library but a “white cube gallery“. As the catalogue progresses, black-and-white photos of items from the exhibition appear on the verso page in frames that appear to be hanging on the trompe l’oeil cube’s rear wall.

Poster distributed on the University of Chicago campus.

The image combines Michael Kostiuk’s Airplane Shadow Book (1981/82) with a variation of the catalogue cover.

Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

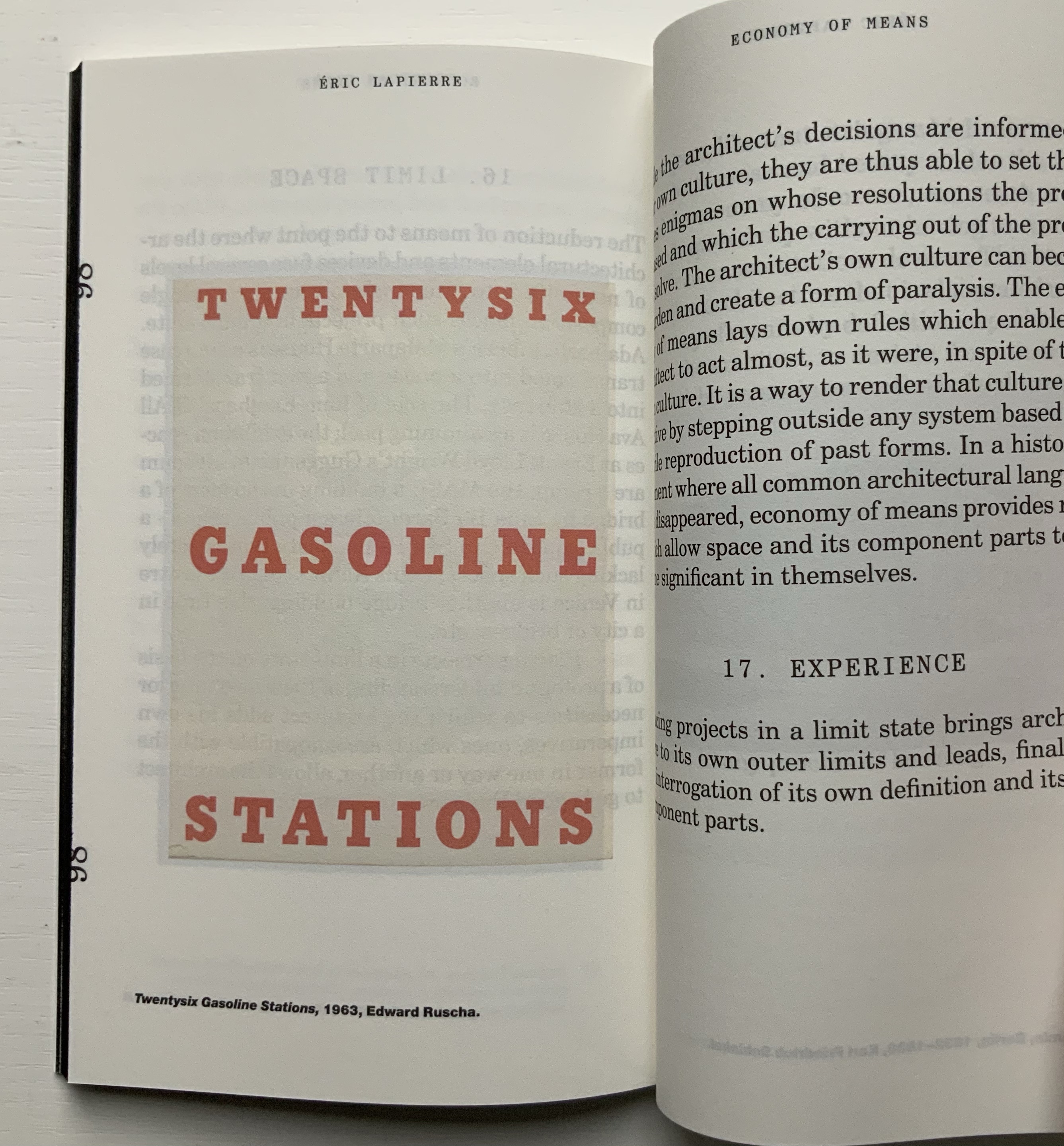

But a viewer standing in the “brutalist” construct of the Regenstein Library and holding the finished catalogue might have asked, “What makes these objects I cannot touch — or, in some cases even if I could, cannot read — art?” There is the catalogue’s third chime. From the start, book art has faced a constant definitional or identity crisis and even the challenge “but is it art?” The catalogue’s title echoes Lucy Lippard’s Duchampian proposition: “It’s an artist book if an artist made it, or if an artist says it is”. The catalogue’s design says, “This is the gallery, these are the objects on display in it, they are art”.

The “white cube gallery” brings on a fourth and final ironic chime. In the 1970s and early ‘80s, artists’ books were pitched as a “democratic” medium and means by which art could escape the clutches of the gallery and reach a wider public. In another catalogue — the one for the 1973 Moore College exhibition, nominated as the first of book art — John Perreault writes:

Books as art, from the artist’s point of view and the viewer’s point of view, are practical and democratic. They do not cost as much as prints. They are portable, personal, and, if need be, disposable. Because books are easily mailed, books as art are aiding in the decentralisation of the art system. — “Some Thoughts on Books as Art”.

By the mid-80s, lo and behold, The Book Made Art’s catalogue-cum-gallery jokingly recaptures “books as art”. And in a further irony, by the mid-80s and since, the increased rareness and price of such bookworks have made them into galleries‘ and museums’ expensive objects of desire. Including this catalogue.

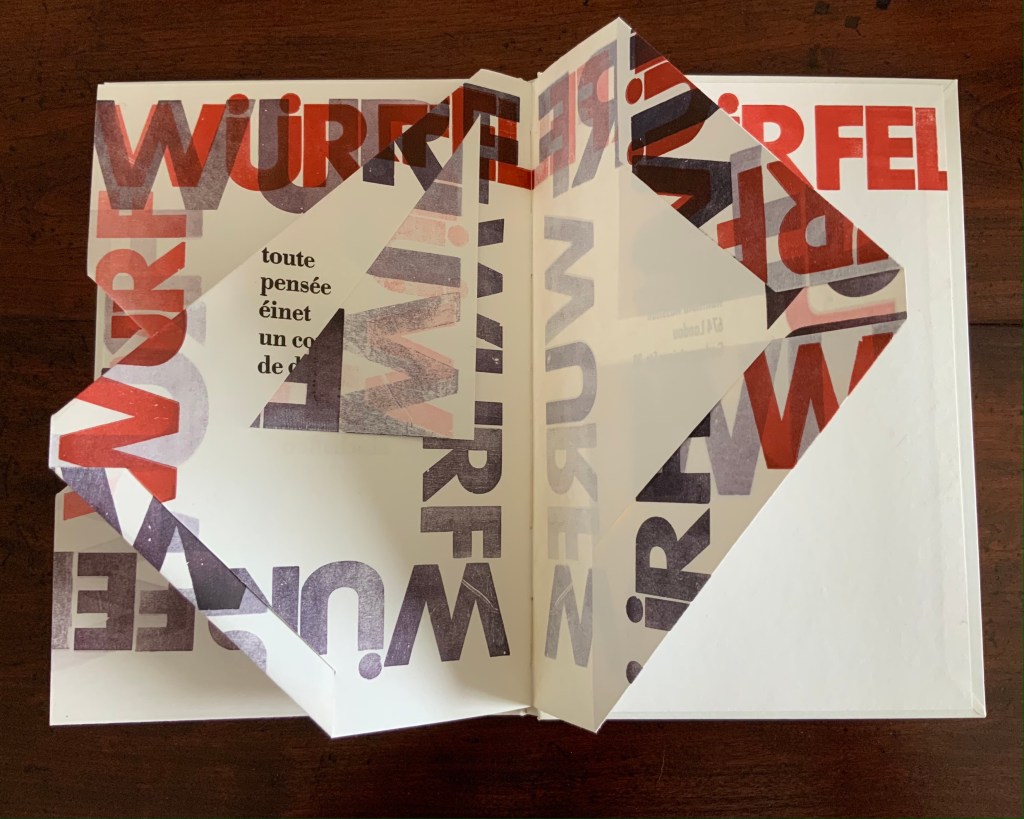

The Library of Babel (1991)

The Library of Babel

Curated and edited by Todd Alden; catalogue designed by Buzz Spector.

Dos-à-dos binding, offset. H241 x 177 mm

Buffalo, NY: Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center, Hallwalls Inc., 1991.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

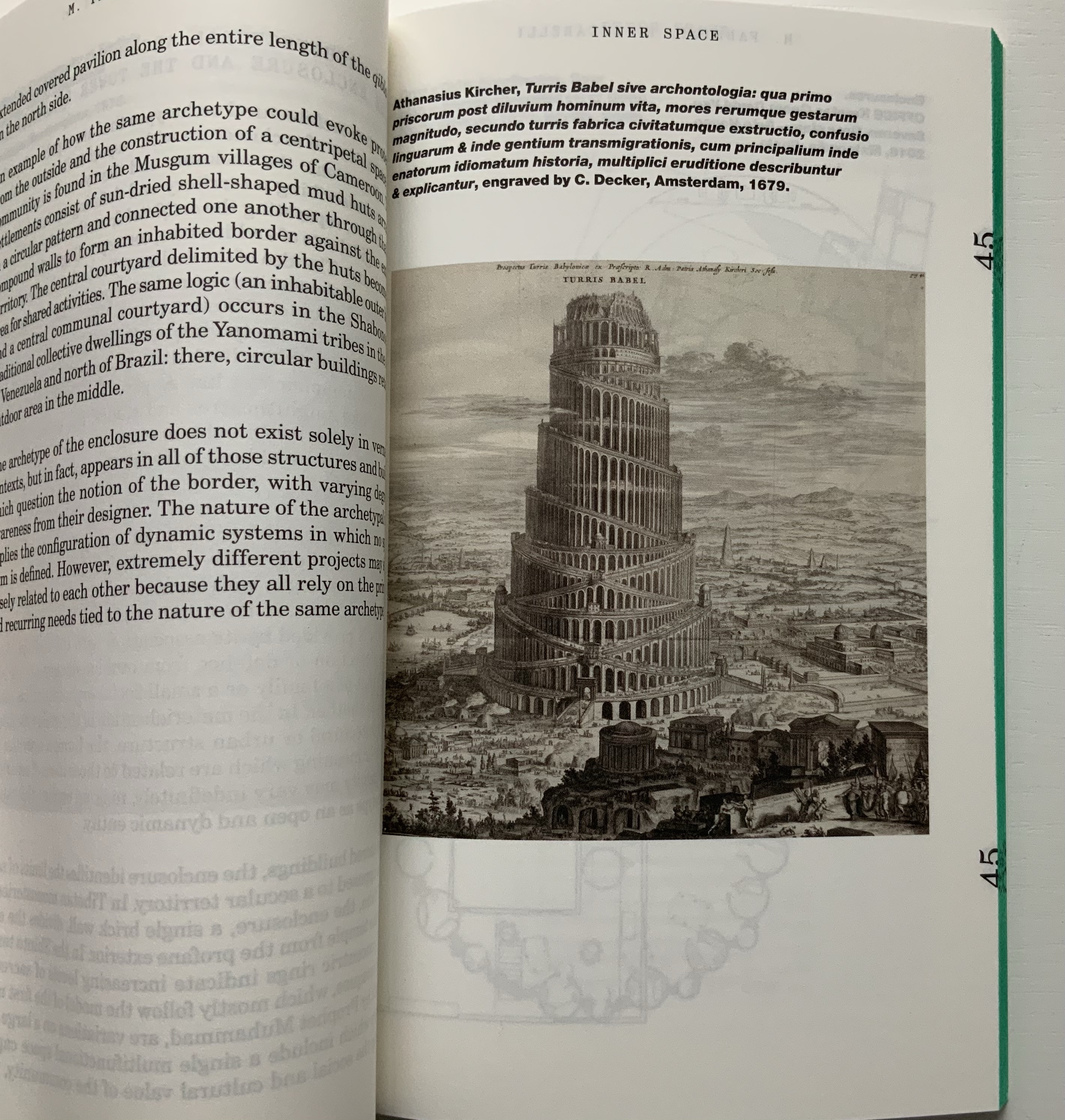

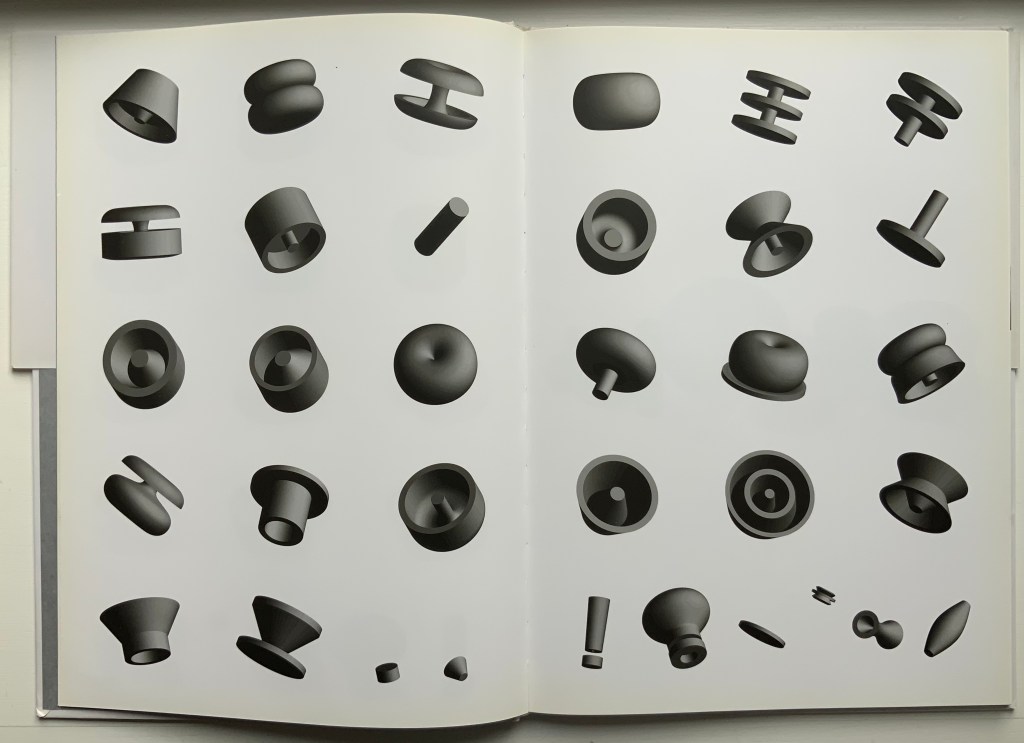

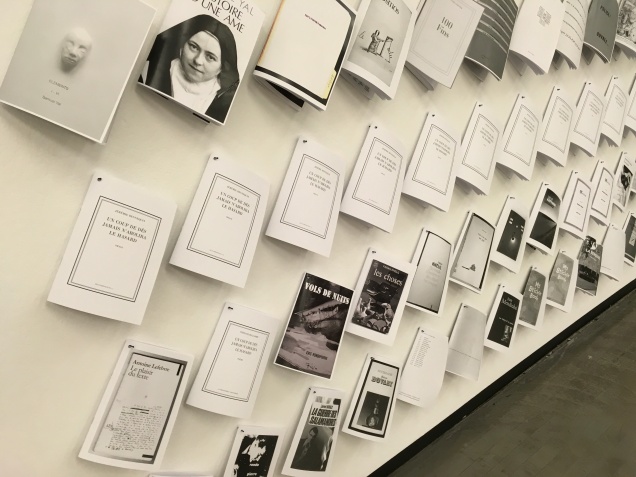

As with The Book Made Art, Spector uses the cover (this time with a photograph of The Library of Babel) to introduce the self-reflexivity so characteristic of book art, but he does not stop there. Pagination and the back-to-back binding structure work together to evoke a mirror’s reflection; the last page of the first half “faces” the last page of the second half.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

The first half contains Todd Alden’s essay “The Library of Babel: Books to Infinity”, Paul Holdengräber’s “Unpacking Benjamin’s Library: Bibliomania in Dark Times”, and a checklist of the 34 works by their 10 artists.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

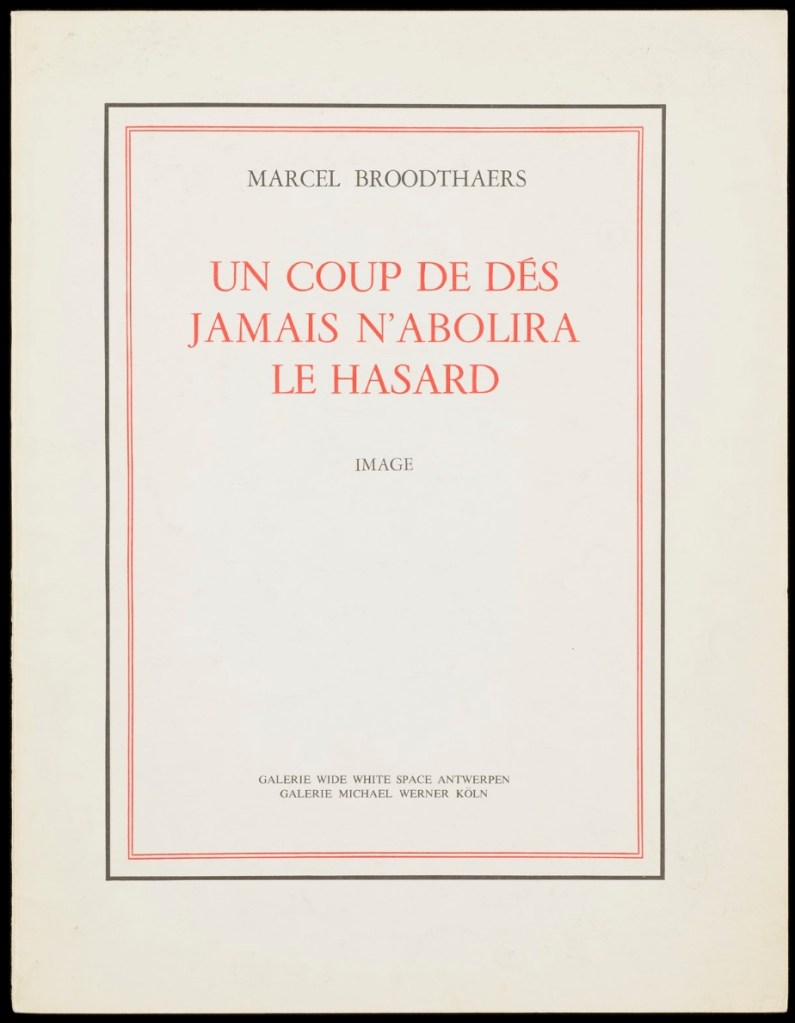

The second half contains half-tones of selected works and brief CVs of the artists. Among the half-tones are also photographs of works referenced by Alden (one by Jasper Johns, two by Marcel Broodthaers). Notice how the rules change position in the footers of the two halves, again evoking the back-to-front theme of the dos-à-dos binding.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

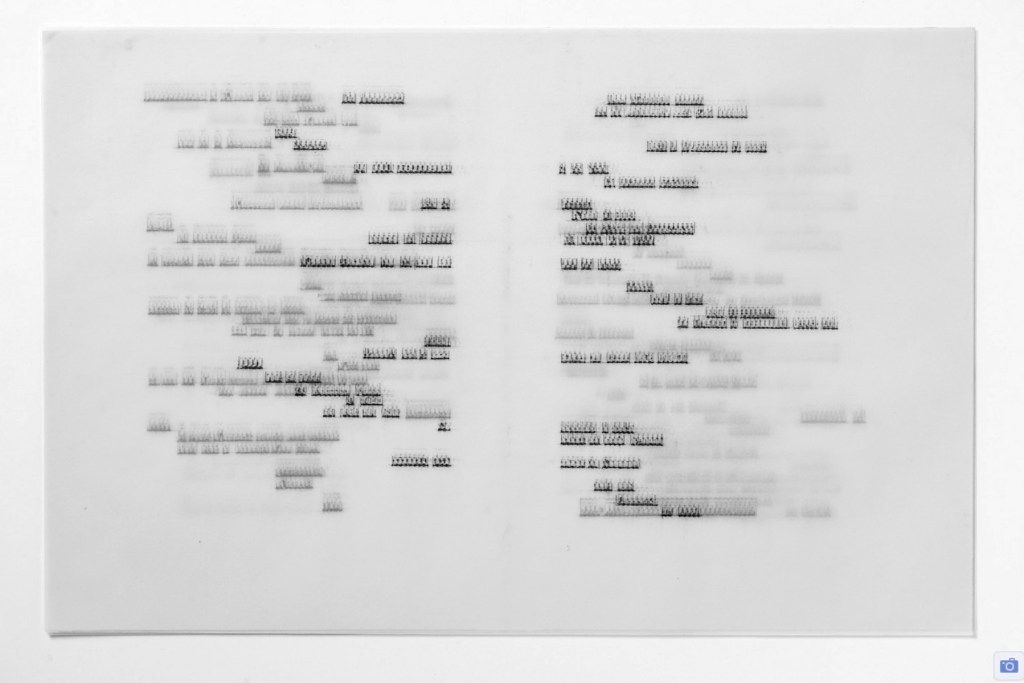

As in The Book Made Art, Spector had an entry in “The Library of Babel“ exhibition. With its torn pages, North Sea (for M.B.) (1990) echoes Altered LeWitt (1985), further below, but it is instead a work 10 feet long and presented on a table appropriately jutting out from the wall like a pier. “M.B.” is Marcel Broodthaers, to whose works there are multiple and layered references. The eleven “waves” of torn pages placed in a row on top of the steel shelf are the excised material from another of Spector’s works: Marcel Broodthaers, made from eleven copies of the Walker Art Center’s 1987 catalogue to Broodthaers’s first U.S. retrospective. Spector painted all the pages in each copy with white gesso before excising them and leaving behind his 1990 “altered Broodthaers”.

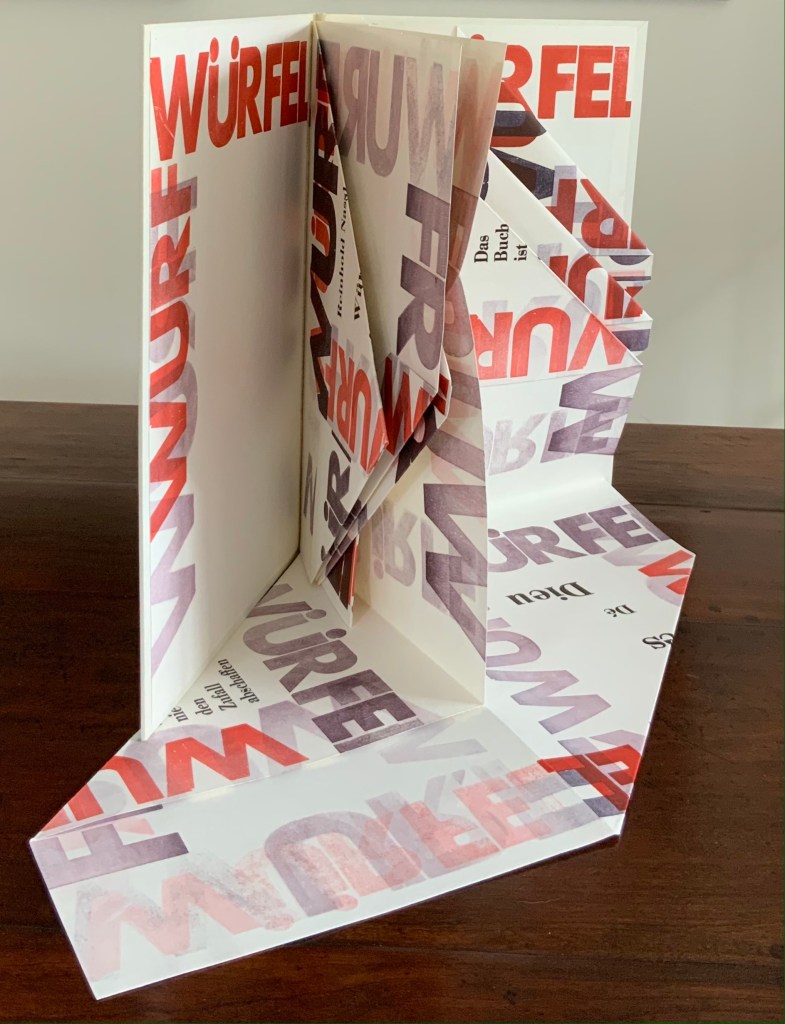

Marcel Broodthaers (1990)

Buzz Spector

An altered copy of: Marcel Broodthaers (Minneapolis/New York: Walker Art Center/Rizzoli, 1989).

Photos: Courtesy of Buzz Spector.

He saved the excised “wedges” and bound them at the fore edges. Because the gesso does not completely obscure the text and images from the catalogues, viewers who come close to the work can see slivers of some of Broodthaers’ works along with the word fragments typical of Spector’s altered books.

North Sea (for M.B.) (1990)

Buzz Spector

Books, steel, gesso, 25 x 96 x 10 inches

Collection Orange County Museum of Art,CA; Museum purchase with additional funds provided by Peter and Eileen Norton and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency.

Photo: Courtesy Orange County Museum of Art.

Spector’s library contains a copy of Broodthaers’ 1974 artist book, A Voyage on the North Sea. These layered references and self-references — direct references to Broodthaers’ A Voyage, indirect references through the self-reference to Spector’s Marcel Broodthaers (1990) — bring into sparkling focus two features of book art and, in particular, late 20th century book art: reverse ekphrasis and bookworks in conversation with one another.

When a visual work of art inspires poetry or prose, the literary result is called ekphrastic: “the verbal representation of visual representation”. But where the poets Keats, Auden and Jarrell, for example, use words to “recreate”, re-present, evoke or respond to works of art — an antique urn, a painting by Brueghel and Donatello’s sculpture of “David” — book artists have in turn used the letter, words, actual books, the physical materials of the book or even the shape of books, their functions or processes of making them to create works of art. A kind of ekphrasis in reverse.

Not only does Spector perform this reverse ekphrasis with exhibition catalogues in North Sea (M.B.), he does it in conversation with a multimedia work by Broodthaers. Works in conversation with one another is also a common occurrence in poetry. An entire anthology showcases these poems that talk to other poems. The later work not only evokes the earlier work, it illuminates and adds to it. In book art, other instances include Bruce Nauman’s Burning Small Fires (1968), a one-sheet folded book of photos of Ed Ruscha’s Various Small Fires and Milk (1964) being set on fire and burning to ash, and Dennis Oppenheim’s Flower Arrangement for Bruce Nauman (1970), a leporello which refers to Nauman’s Flour Arrangements (1967), a video in which the artist pours over 50 pounds of flour on a mock talk-show studio floor and then sculpts it into ephemeral shapes. Nauman’s shift to an ingenious folded single-sheet structure and Oppenheim’s shift (and pun) to an accordion view of flowers are part of the addition to their conversations with their very structurally different counterparts. Spector’s shift to the sculptural is part of the addition to his conversation with Broodthaers’ book and video. Consider not only Spector’s gessoed sea of pages and the pier, but also those two 19th century black bronze sailing ship bookends evoking the 19th century nautical painting that Broodthaers appropriated in A Voyage on the North Sea.

North Sea (for M.B.) (1990)

Buzz Spector

Books, steel, gesso, 25 x 96 x 10 inches

Collection Orange County Museum of Art,CA; Museum purchase with additional funds provided by Peter and Eileen Norton and the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency.

Photo: Courtesy Orange County Museum of Art.

Screenshot of “Marcel Broodthaers: A Voyage to the North Sea“, an exhibition at Specific Object, 28 January-20 March 2009.

Unpacking my Library (1995)

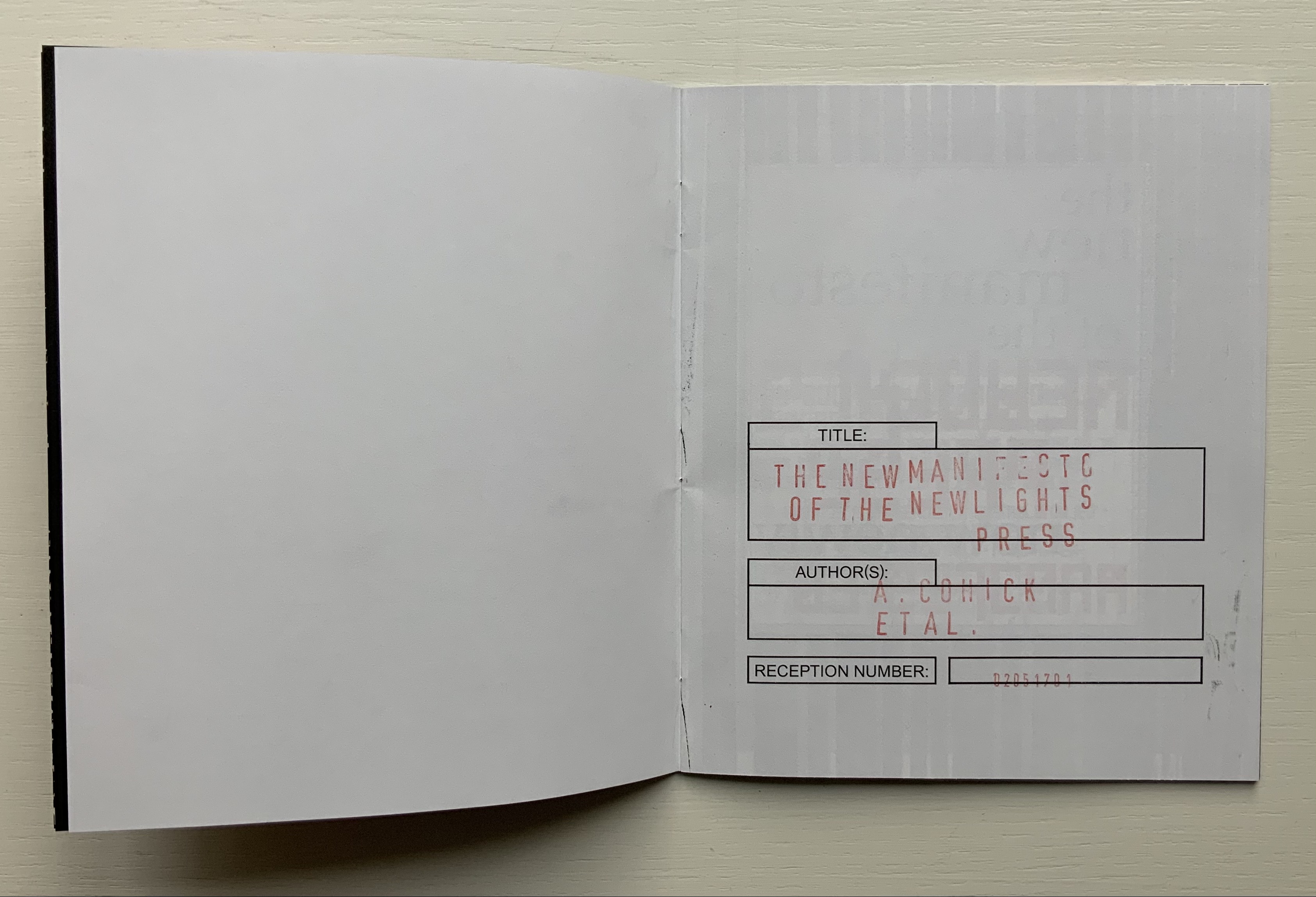

Unpacking my Library (1994-95)

Buzz Spector

Leporello full-colour offset printed; folded H100 x W155 mm, unfolded W3600 mm; Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art.

Installation exhibited at the San Diego State University Art Gallery, 1-31 October 1994.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

Clearly from his entry in The Library of Babel, Spector’s artistic output extends beyond altered books and catalogue design to larger scale installations. One of the more well-known, Unpacking my Library imposes multiple orders on what Walter Benjamin called “the chaos of memories”. How “multiple orders”? First, because of its subtleties; second, because of its several forms.

From the start at the San Diego State University Art Gallery, 1-31 October 1994, the installation imposed the order of “descending height” on Spector’s library, unpacked and displayed across one shelf attached along the white walls of a room in the gallery. The single shelf ran 188 feet.

Although Spector is rejecting the library’s traditional method of making sense of a collection of books — ordering by academic category — in favor of a physical criterion, the title imposes another method of making sense — allusion. The installation makes “more” sense if you have read Walter Benjamin’s essay “Unpacking My Library — A Talk on Collecting” (1931). If you haven’t, then, on the reverse of the leporello produced with the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, are these two sentences from the essay:

This or any other procedure is merely a dam against the spring tide of memories which surges toward any collector as he contemplates his possessions. Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the collector’s passion borders on the chaos of memories.

So what has ordering by height to do with the chaos of memories? Well, if the order of the personal library had been chronological by acquisition, that would be an assertion against chaos, a kind of aide- mèmoire. If the order had been by the library’s traditional method, again that would be an assertion against chaos. Benjamin and Spector embrace the chaos. Spector’s at-first amusing and puzzling organization of his library prods the viewer into the chance to do somewhat the same — to wander along the shelf with that phrase of process hovering in the mind and be reminded of books once read (when? where?), familiar and almost-familiar names and places (from when or where?) and subjects studied (what did that cover?). But the viewer also experiences a surge of unknown names, places and subjects, and spines that mystify.

The allusion to Benjamin’s essay offers another way of making sense of this experience into which the viewer is prodded. If a personal library is a kind of self portrait you can detect from the clues that its usual groupings into fiction, biographies, history, science, etc., give us about the owner, then here the order by height washes them and the portrait away. And if the viewer knows the essay, Benjamin’s last sentence may come to mind:

So I have erected one of [the real collector’s] dwellings, with books as the building stones, before you, and now he going to disappear inside, as is fitting. — Walter Benjamin, “Unpacking My Library”

Screenshot from Buzz Spector, inSITE 94 (interview).

Spector mentions this disappearance in a video record of the making and showing of the installation. Whether or not the installation’s spectator knows Benjamin’s essay, the installation’s title is a clue to the imposition of a fictional order. “Unpacking my library” is a phrase implying an activity that is just getting going. For his essay, Benjamin created the fiction of the reader’s being present as the library is being unpacked. Likewise for Spector’s installation, any spectator walking into it has entered a fiction. Spector’s library has already been unpacked, sorted on the floor and placed on the single shelf running around the room.

Of course, however, the owner of the leporello form of Unpacking my Library does not experience this fiction as directly. The opening and arranging of the leporello is a hands-on activity; the unpacking of Spector’s library occurs panel by panel in the reader’s hands. The library’s arrangement by height appears more gradually than in the gallery. Once the bookwork is fully extended, the installation’s fiction then becomes more readily available to the leporello’ s reader/viewer.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

As fictions, Benjamin’s essay and Spector’s installation need an ending. Benjamin’s technique is to disappear into his collection. Spector chooses a different technique. In correspondence with Books On Books, he writes:

The length of all the publications in my library was 165 feet; the single shelf, at the UCSD Art Gallery, on which they were placed ran 188 feet. That additional space implied a future, and life-affirming, growth of my collection. — Buzz Spector, 26 March 2020.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

Whether it is leporello or installation, the reader/viewer of Unpacking my Library is launching and launched on this open-ended ending.

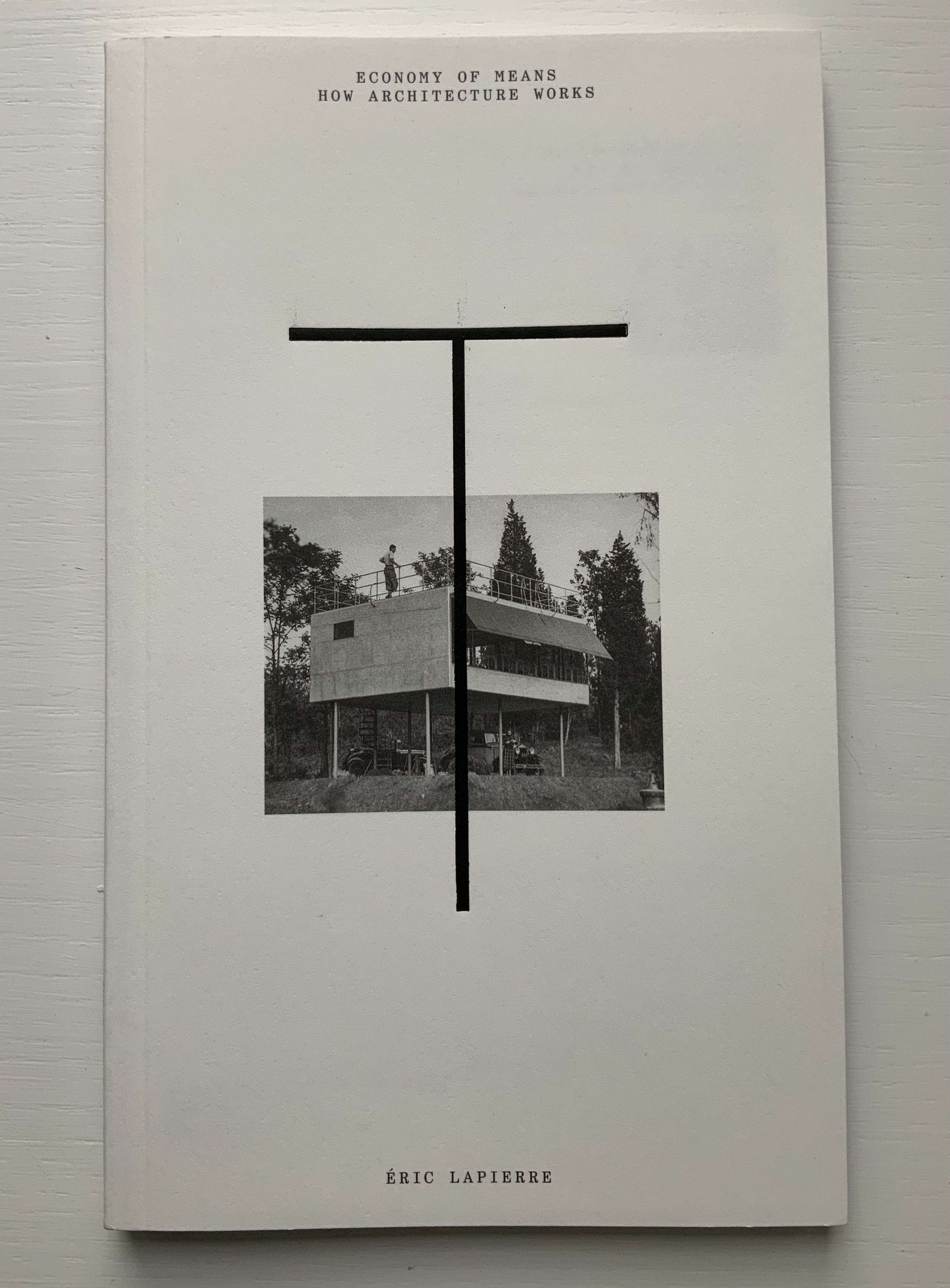

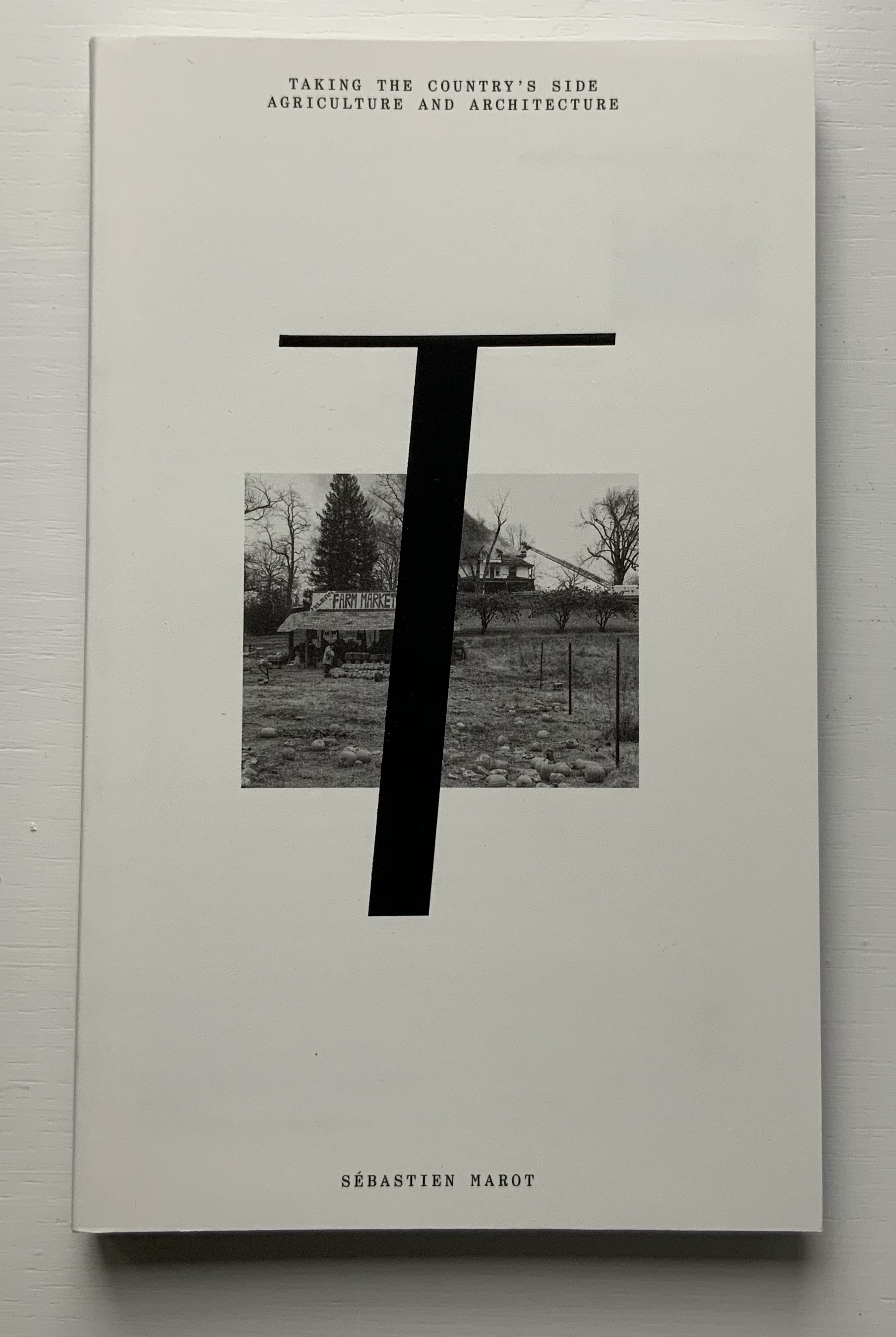

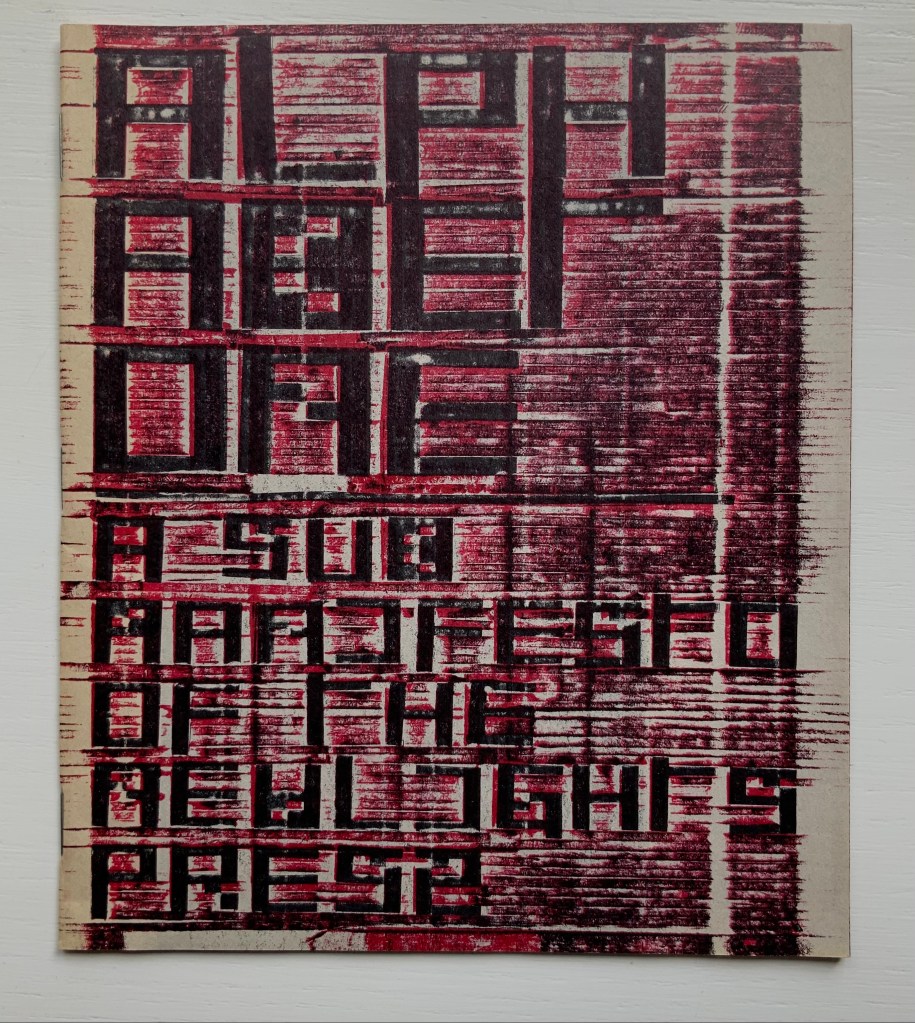

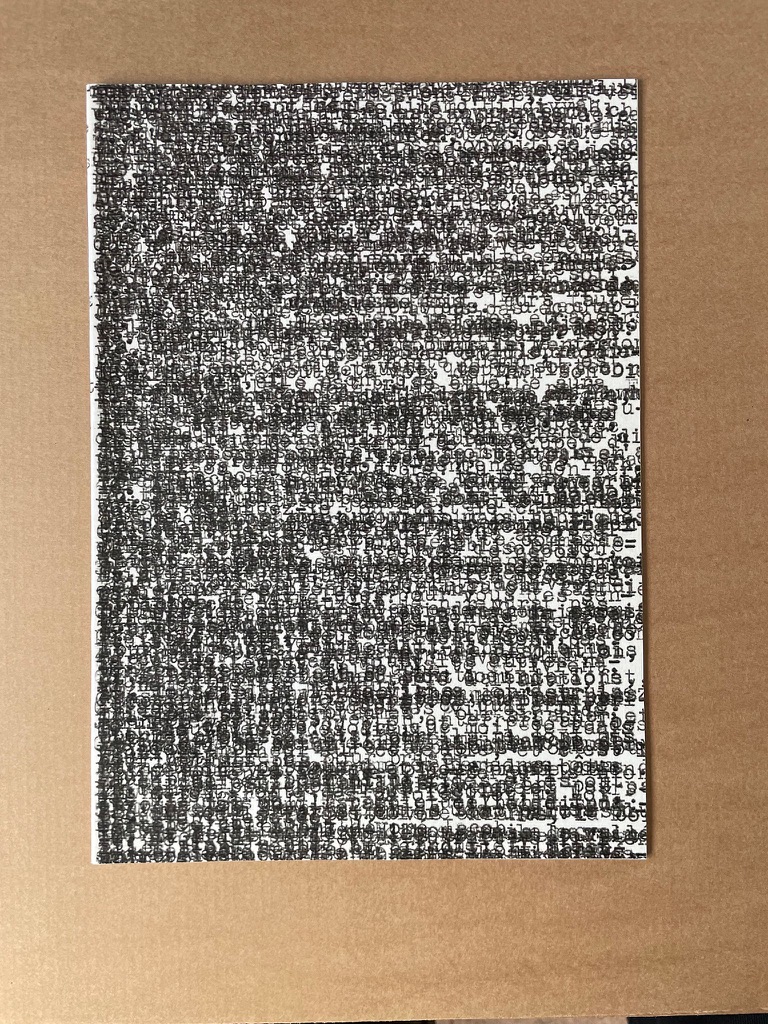

The Book Maker’s Desire (1995)

The Book Maker’s Desire: Writings on the Art of the Book

Buzz Spector

Pasadena, CA: Umbrella Editions, 1995. 2nd printing.

Cover design by Buzz Spector. Image: History of Europe (1983) by Buzz Spector; plaster over found book, 10.5 x 12 x 15 inches.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

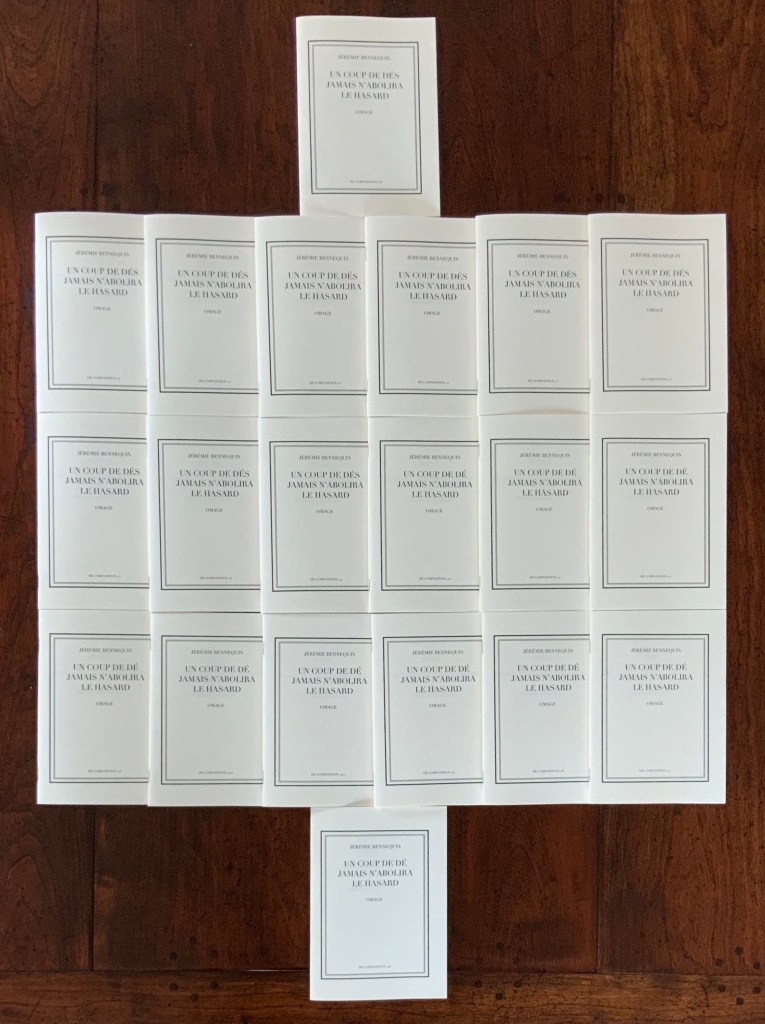

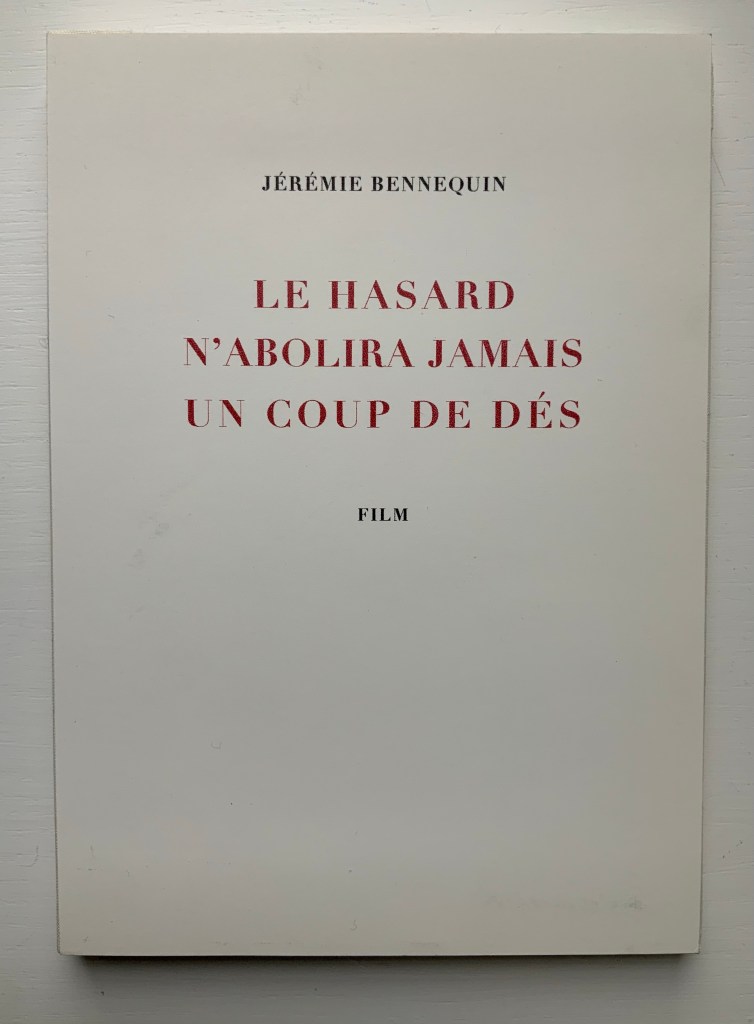

Spector’s essays are tonic. His comments on Margaret Wharton’s bookworks could refresh any reader and viewer lucky enough to see her works (Union League Club-Chicago or Yale) or remind the viewer of them when looking at works by later artists such as Thomas Wightman or the “Mystery Book Artist of Edinburgh”. In the past few months, Walter Hamady and John Baldessari have died, and Spector’s essays on them bring them both and particular works of theirs to present life. His essay and letter on Broodthaers would enhance any reading of the artists who have stood on Broodthaers’ shoulders to address Mallarmé’s Un Coup de Dés: Bennequin, Mutel, Pichler, Wyn Evans, Zboya. The essay “Going Over the Books” may have inspired Alden’s curation of ‘The Library of Babel” exhibition.

The essays are not entirely the point of having The Book Maker’s Desire in the Books On Books Collection. What completes the point is the cover design. The object on the book’s front cover is Spector’s own work History of Europe (1983), which pays homage to Broodthaers’ Pense-Bête (1964). But look closer. The cover stock has elements of text and colour seeping through, almost as if it were made of shredded books. The aptness and artistry of the cover design make The Book Maker’s Desire an object of desire in and of itself.

Detail of cover: Books On Books Collection.

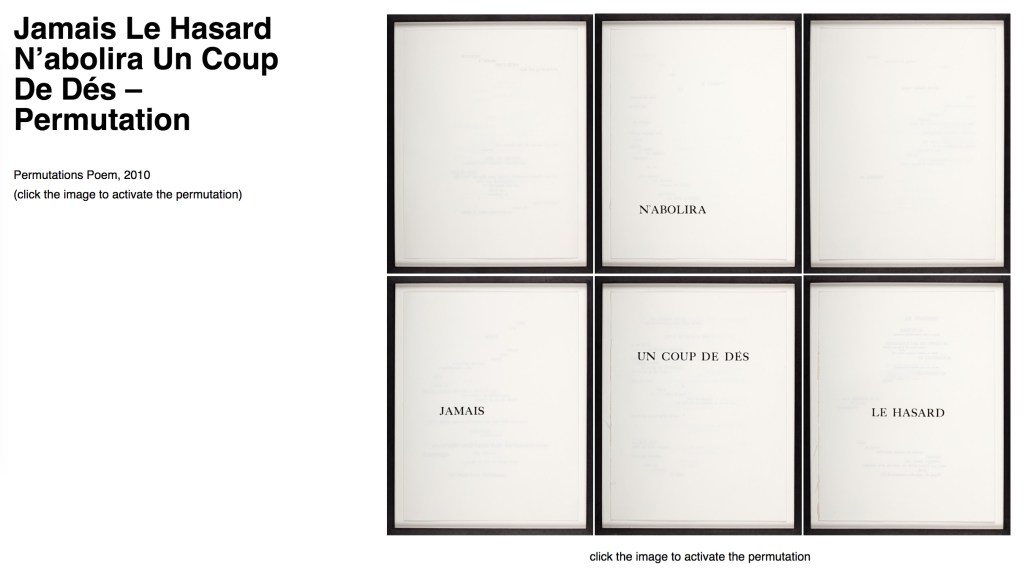

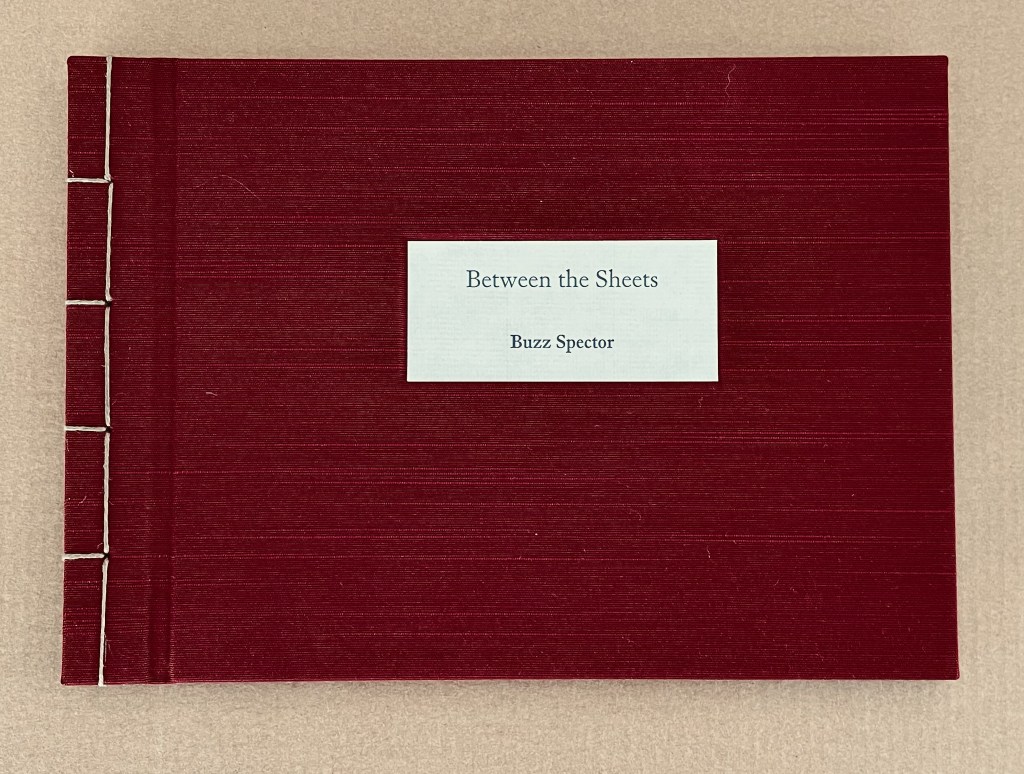

Along with Unpacking my Library, Between the Sheets (2003) is the only other of Spector’s limited edition artist’s books in the Books On Books Collection. It is the solo exhibition to the joint exhibition of The Book Made Art (1986), described at the outset of this entry. In Between the Sheets, Spector again shows the self-reflexiveness of book art but also demonstrates how originality can spring from it.

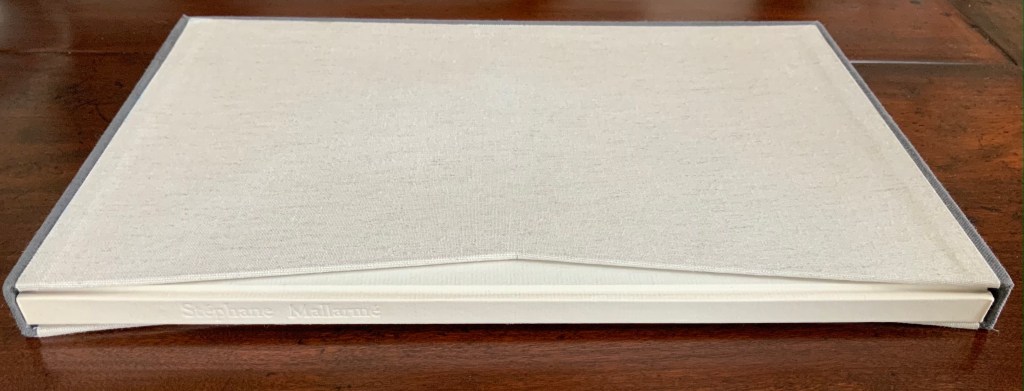

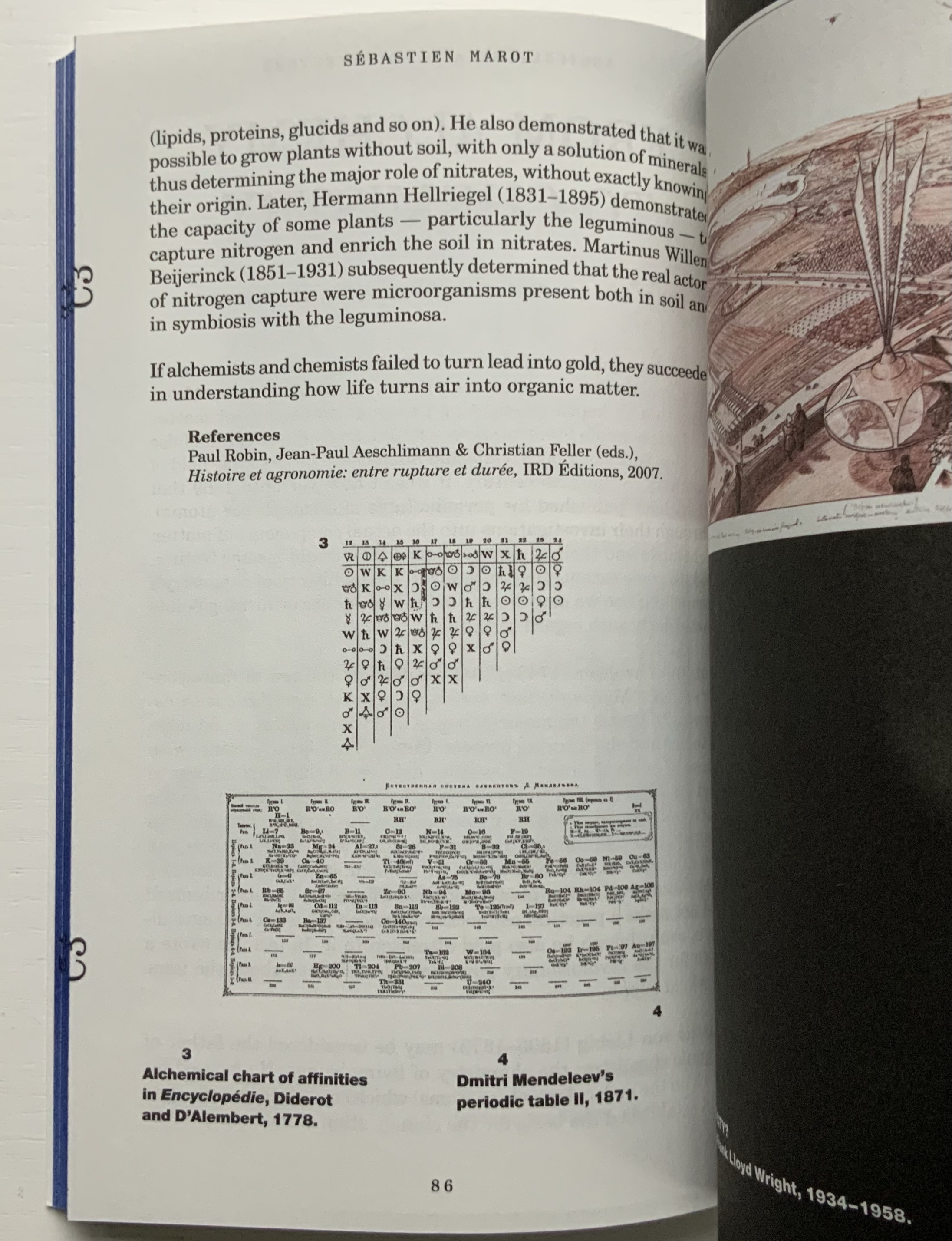

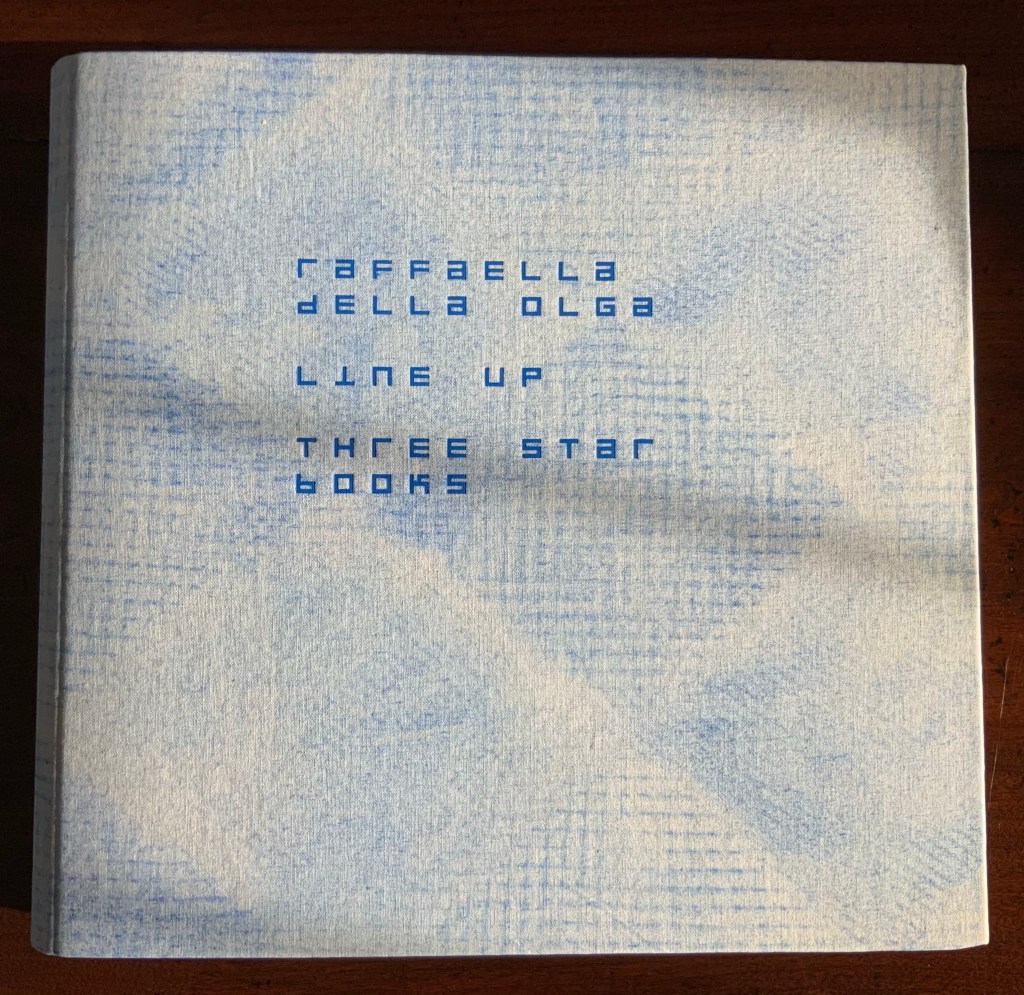

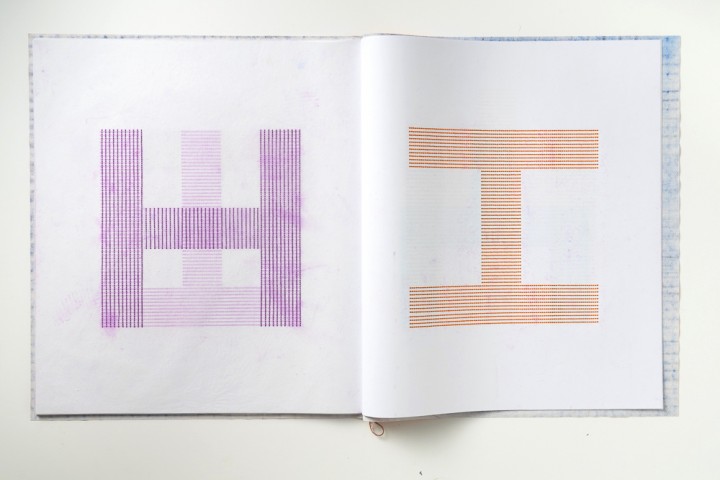

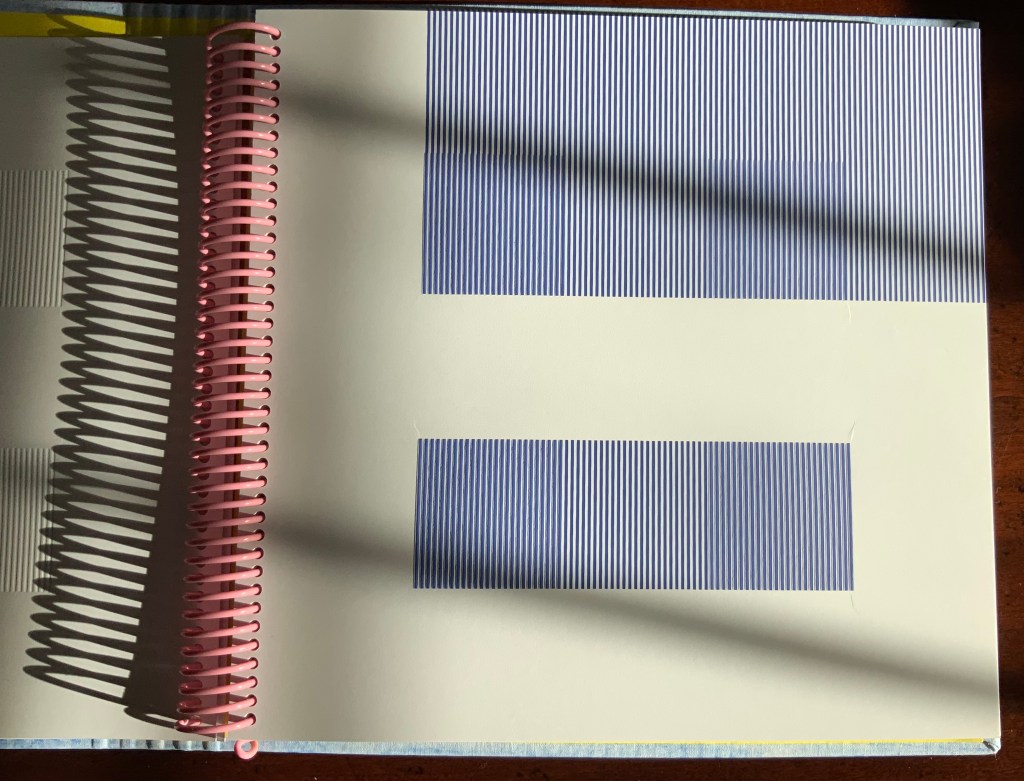

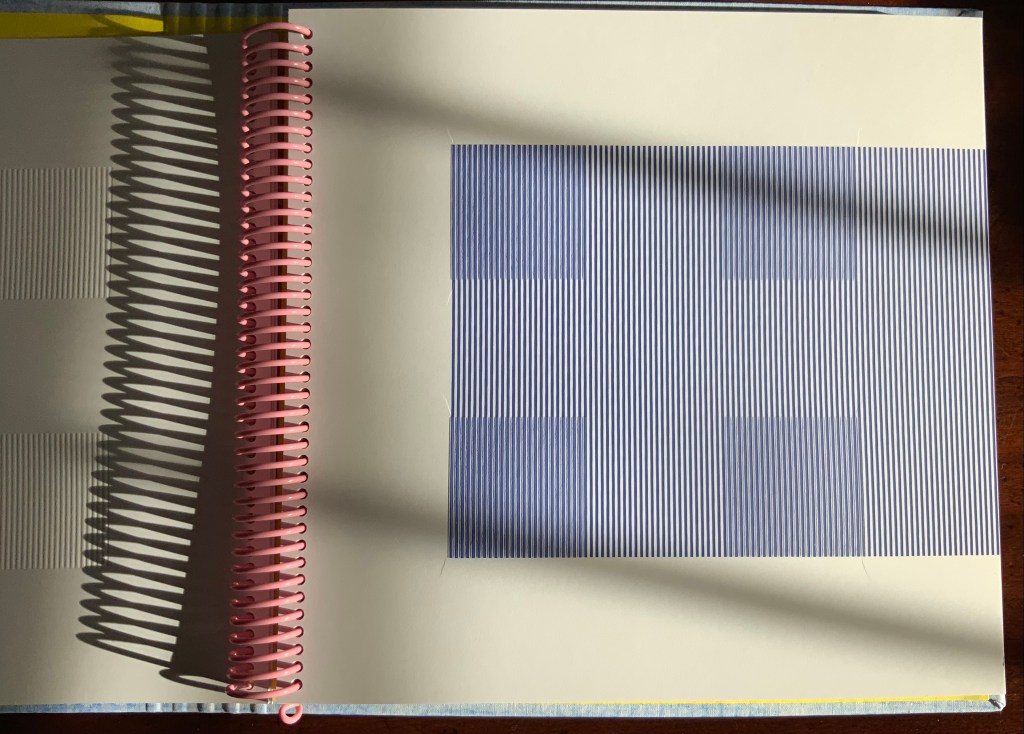

Between the Sheets (2003)

Between the Sheets (2003)

Buzz Spector

Cloth over boards, Japanese stab binding, 15 folded sheets, outer sides offset printed with enlarged “authors’ photos” clipped from dust jackets of art books repurposed by Spector for his bookworks, inner side printed (recto only) with text by and selected by Spector. H157.5 x W216 x D12.7 mm. Edition of 40, of which this is #40. Acquired from Olive Branch Press, 26 June 2020.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

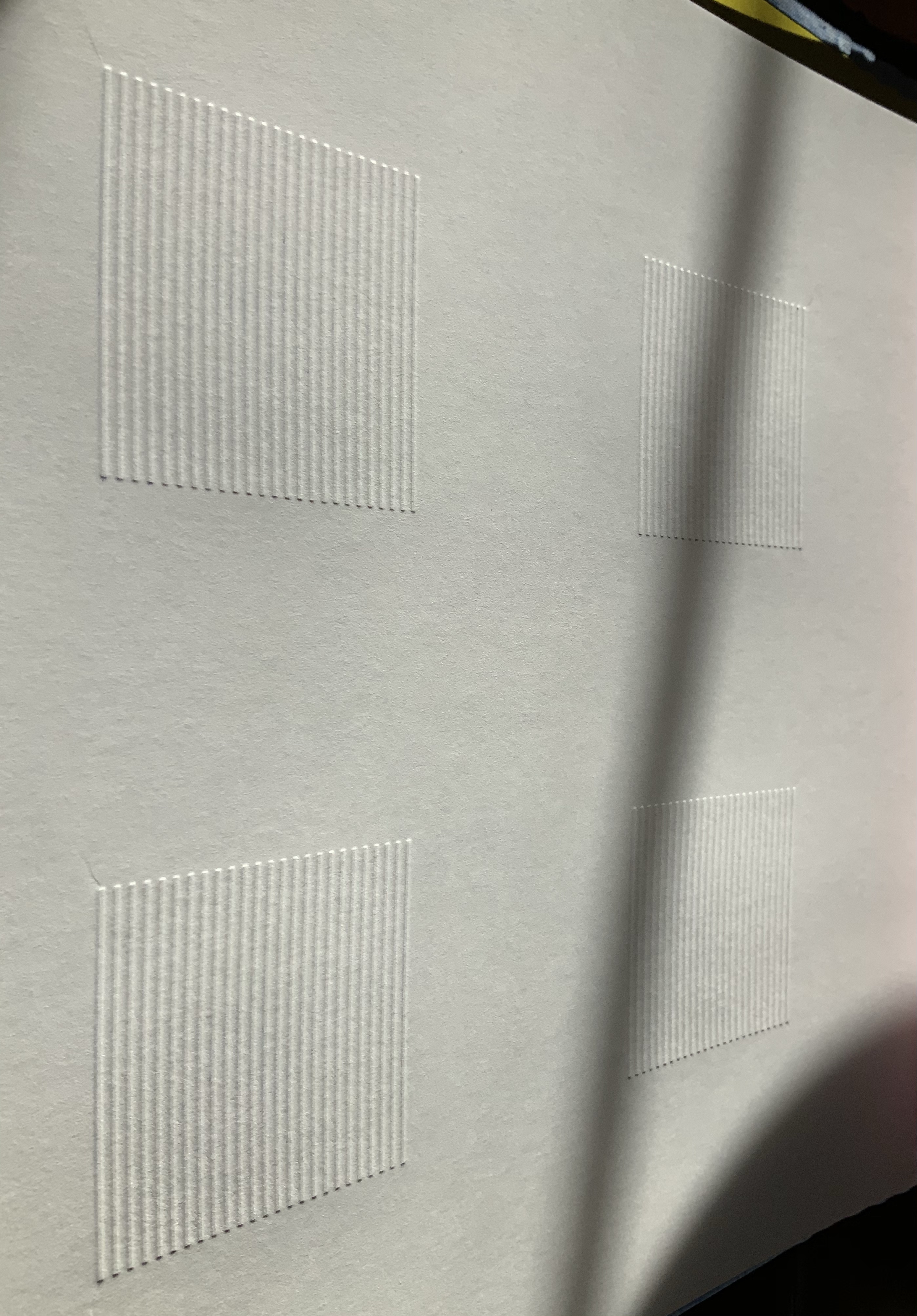

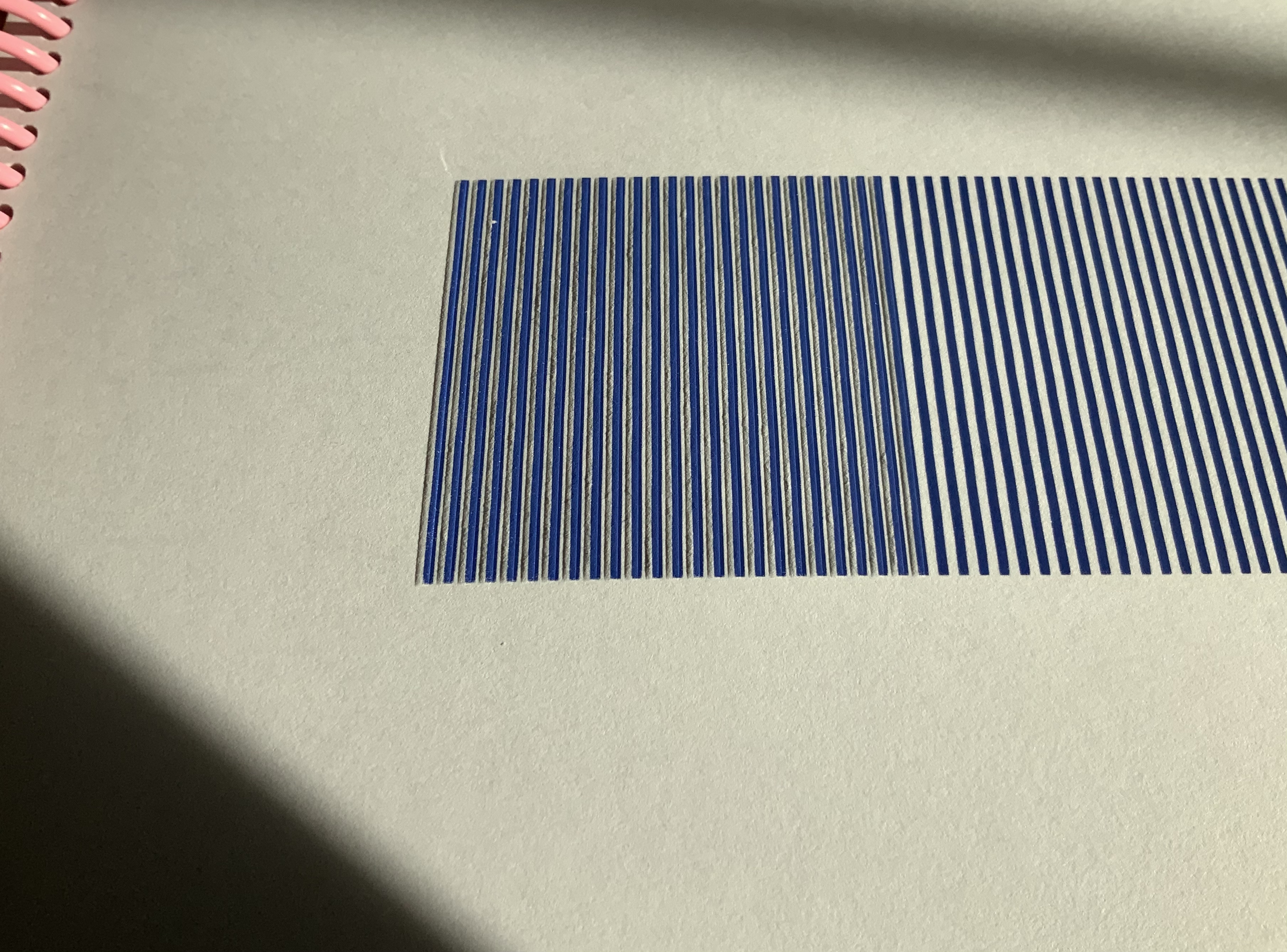

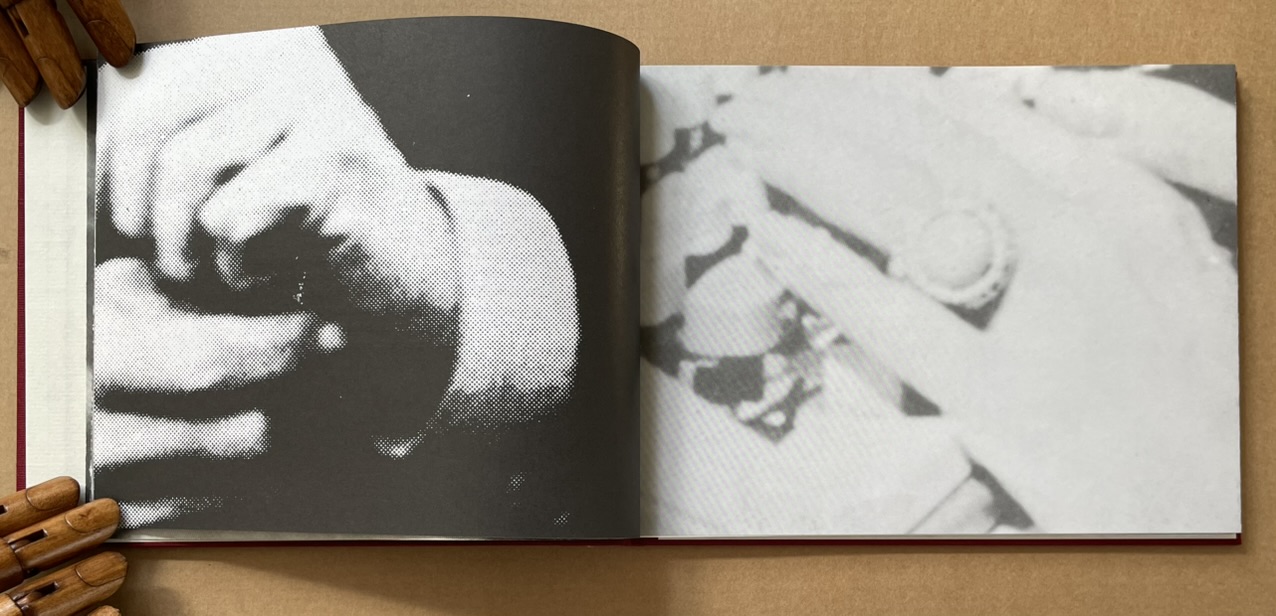

Unlike Altered Lewitt (1985) and North Sea (for M.B.) (1990), which appropriate and alter named works, Between the Sheets is made at two or three removes from its source material. In the first instance, Spector clipped authors’ photos from the dust jackets of their books (unnamed), then rephotographed and printed them at enlarged scale in offset editions. These prints were then bound together to make books. As with Altered Lewitt and other works, Spector then tore strips in a sequence of decreasing increments from the spreads so as to form a wedge-shaped cross section of the image block. In the next remove, this process left a pile of torn strips, and from these torn strips, Spector has proceeded to create Between the Sheets. With images on one side and text imposed on the reverse, these folios are folded and bound at their open ends with Japanese stab binding.

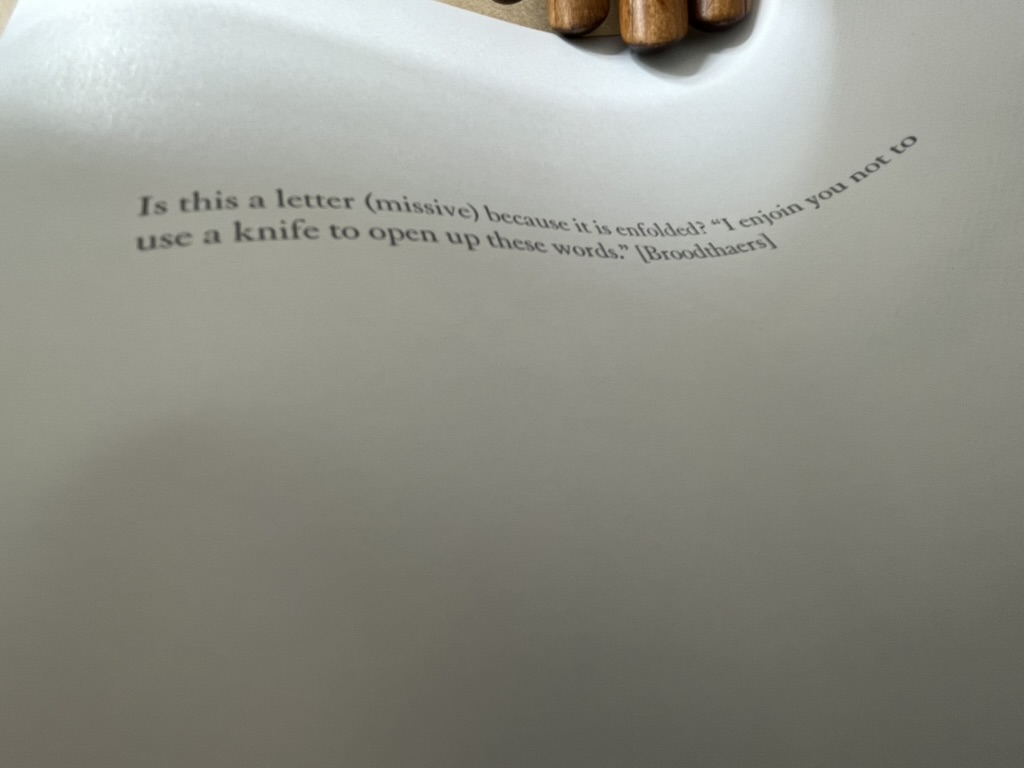

The work’s main thrust is philosophically, artistically and self-reflexively aesthetic. It quotes from the French philosopher Guy Debord, the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers and Spector himself. The quotation from Debord comes early on, the first after the title page and two of prefatory explanation, and very much sets the tone.

Diversion is the opposite of quotation, of the theoretical authority which is always falsified by the mere fate of having become a quotation — a fragment torn from its context, from its movement … [Debord]

With Between the Sheets, we have on our hands a decidedly multi-layered diversion. At one layer, it diverts by questioning Debord’s own words, consigning their “theoretical authority” to a fate of falsification by “having become a quotation — a fragment torn from its context”. Like a fun-house mirror, the page bows to give this distorted reflection of Debord’s words.

But is it a diversion? After all, the “truth” of Between the Sheets rests at least in part in its composition from fragments. At this other layer, Between the Sheets “quotes” the fragments torn from the context of another of Spector’s artwork. In turn, that other artwork was composed of prints of photographic “quotations”, the fragments torn from authors’ images on dust jackets (the coverlets for the source books and their sheets). It is no accident that, when the sheets of Between the Sheets are bowed to permit a look inside, the images bracket the text pages like single quotation marks.

Another quotation resting between the sheets comes from Spector’s own essay on Ann Hamilton in The Book Maker’s Desire (p.63):

A printed page to whose every word is attached a tiny stone. It is as if an edifice of ancient language had crumbled under the force of centuries, leaving a granular residue that still corresponded to the structure of now vanished thought. [a page by Ann Hamilton]

Spector runs the risk of “Debord-ing” himself here with his self-quotation, but he only succeeds in diverting this reader back to the essay on Hamilton’s work and specifically the four works commissioned to benefit The New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York:

The artist chose a total of fifty four volumes (40 in the edition, plus 14 artist’ proofs) for the untitled project. These found books, mostly old novels or poetry, were selected for a variety of physical characteristics –size, wear, and paper quality — and for their typographic layout. Each book was opened to its middle, where six or eight pages were cut from the text block and reattached, edge-to-edge, to the right-hand side of the opened page spread, making an accordian-fold [sic] extension from the book. The eight pages thus displayed were meticulously rendered unreadable by Hamilton and several attendants who glued tiny stones over every word on the visible side. (p. 63)

Is it a coincidence that Between the Sheets also consists of 40 in the edition just like Hamilton’s commission? Spector quotes not only images and words from others’ works and his own, he quotes the details of their production and form. It is certainly no coincidence that Between the Sheets quotes the stab bound structure of Marcel Broodthaers’ A Voyage on the North Sea. After all, in his hidden prefatory explanation, Spector makes no bones about the fact that Between the Sheets arose in part from his astonishment at finding the page numbers hidden within the bound edge of A Voyage. But how did he find them? In the process of creating his own North Sea (for M.B.) (1990). So yet another self-quotation of production process.

Spector’s forthright quotations are divertingly sly. When he cites Broodthaers between these sheets,

he is also echoing Broodthaers’ injunctions in A Voyage on the North Sea:

Before cutting the pages the reader had better beware of the knife he will be wielding for the purpose. Sooner than make such a gesture, I would prefer him to hold back that weapon, dagger, piece of office equipment which, swift as lightning, might turn into an indefinite sky. … These pages must not be cut.

Of course, Spector did not cut the pages; he tore them.

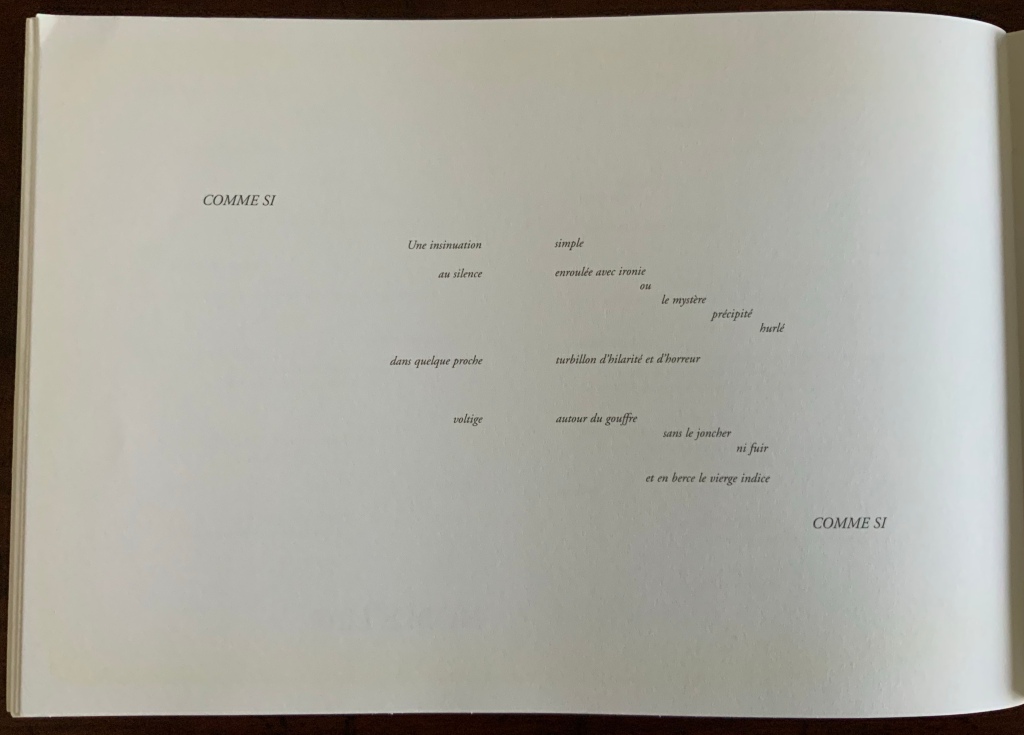

Another sly diversion is sex. By using photos of male and female authors and by interposing suggestive phrases inside the folds (“a movement of bodies together as one body” and “peek between the sheets”), Spector spices up the obvious diversion of sex in his work’s title. But the slyness re-diverts via Broodthaers to Mallarmé, whose poem Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira le Hasard (1897) Broodthaers “knifed up” at the very level of the words and whose contemplations of the letter, the page and the fold have taken on an erotic tone that Spector embraces in A Book Maker’s Desire:

When Stéphane Mallarmé described the folded and uncut signatures of books as “virginal,” awaiting the penetration of the “paper knife,” he identified an erotics of reading. (p.15)

The topography of an open book is explicit in its erotic associations: sumptuous twin paper curves that meet in a recessed seam. Page turning is a series of gentle, sweeping gestures, like the brush of fingers on a naked back. Indeed, the behavior of readers has more in common with the play of intimacy than with the public decorum of art viewing or music listening. Most of us read lying down or seated and most of us read at least partially unclothed. We dress up to go out and look at art; undressed, in bed, we read. We seek greater comfort while reading than the furnishings of museums or concert halls will ever grant us. When we read — the conventional distance between eye and page is around fourteen inches — we often become the lectern that receives the book: chest, arms, lap, or thighs. This proximity is the territory of embrace, of possession; not to be entered without permission. (p.17)

There is much more between the sheets of Between the Sheets. I wish that the 40 copies could find many more readers/lovers to embrace its diversions.

Buzz Spector: Alterations (2020)

Buzz Spector: Alterations (2020)

Buzz Spector

Gretchen L. Wagner; Elizabeth Wyckoff; Andrea Ferber Brochure. H254 x W256 mm, 4 unnumbered pages. Acquired from the artist, 23 June 2020.

Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection.

Three items of ephemera conclude this entry. The first is a pristine copy of the announcement for Spector’s retrospective at the Saint Louis Art Museum, held 20 November 2020 through 31 May 31 2021, along with a copy of it with the front cover hand torn by the artist. The second is the catalogue from his show in 2021 Between the Lines. With both, Spector makes an ephemeral piece echo the works in the exhibition. The third item is a hand torn postcard reproducing his drawing Torn Flag (2022).

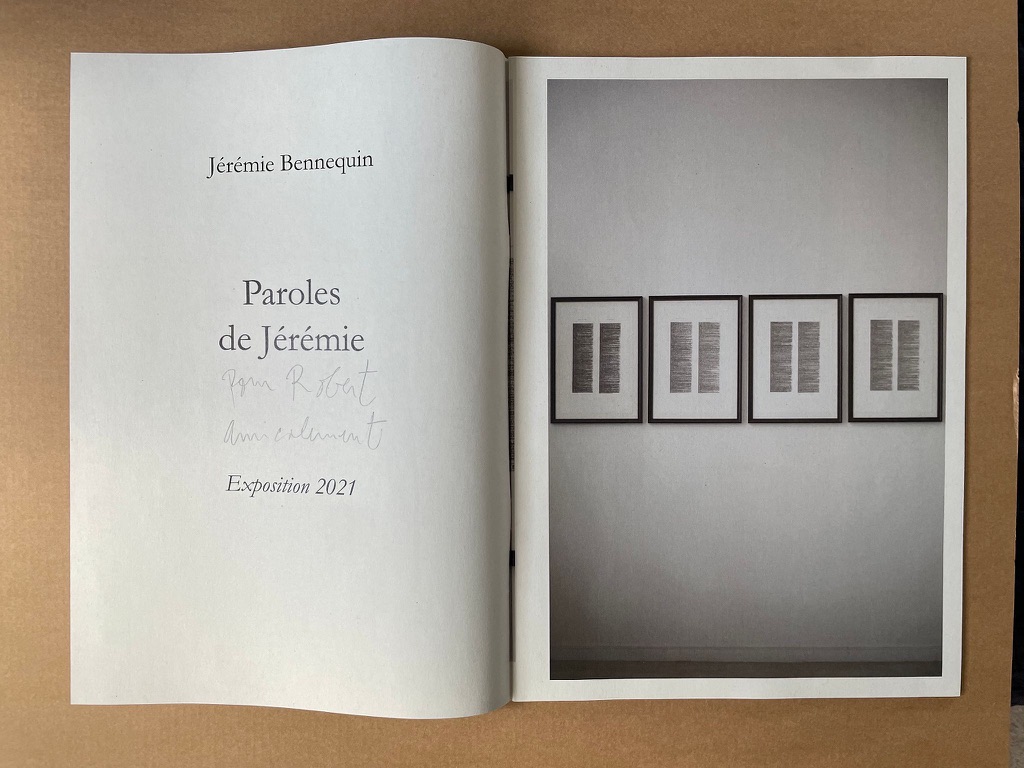

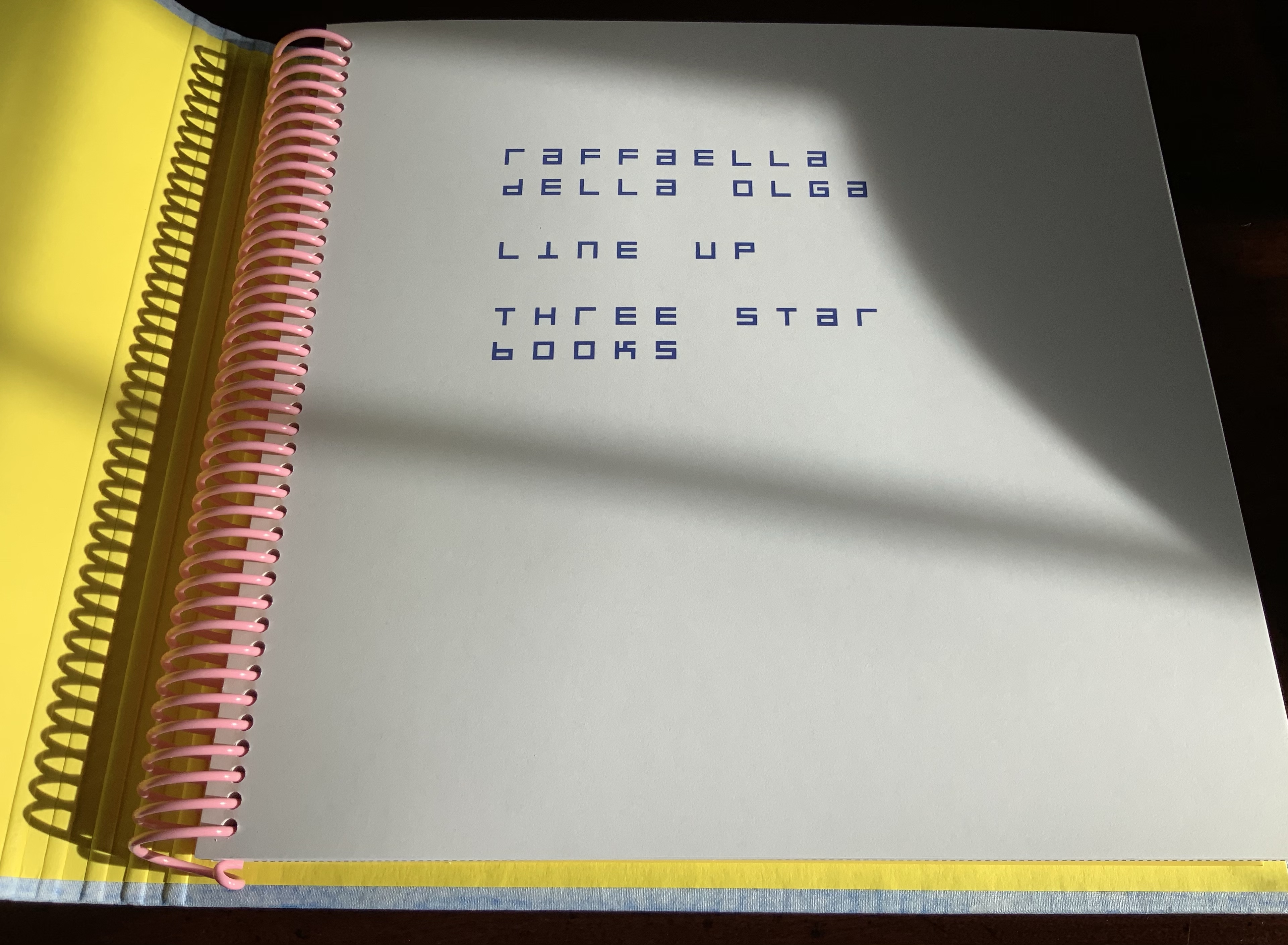

Between the Lines (2021)

Between the Lines (2021)

Buzz Spector

Elizabeth Wyckoff, Gretchen L. Wagner, Meredith Malone, Michael Garzel, Jane E. Neidhardt

Perfect bound paperback. H268 x W 230 mm, 81 pages. Acquired from the artist, 10 March 2021.

Photo of the work: Books On Books Collection.

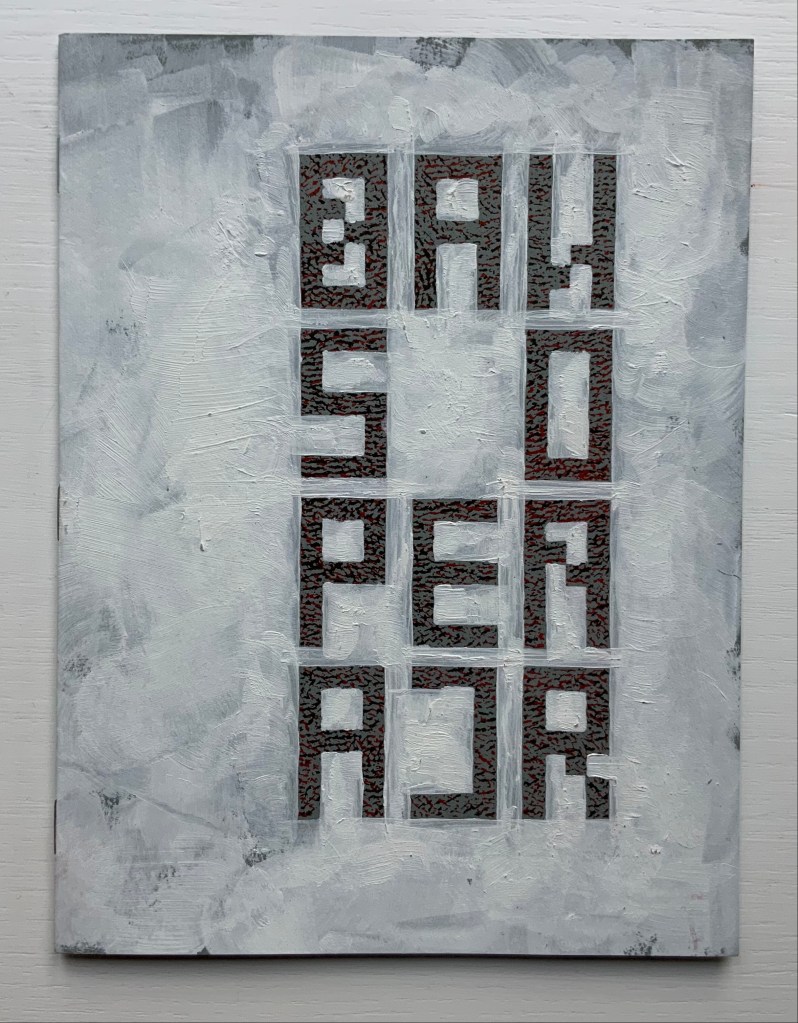

The Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, which has supported Spector’s work since 1995, sponsored this monograph following 2020/21 retrospective held at the Saint Louis Art Museum. As a slightly less ephemeral item, it neatly rounds off this entry. Its cover image shows one of Spector’s well-known alterations: Altered LeWitt (1985), one of five of the found and hand-torn catalogue: Sol LeWitt, Drawing Series I, II, III, IIII A & B (Turin, Italy, at the Galleria Sperone, 1974). Compare it with North Sea (for M.B), above, which Spector created five years after Altered LeWitt. Spector extends the technique and concept across the two works in distinctive ways to echo two distinctive artists and yet also speak to commonalities and originality among the three artists.

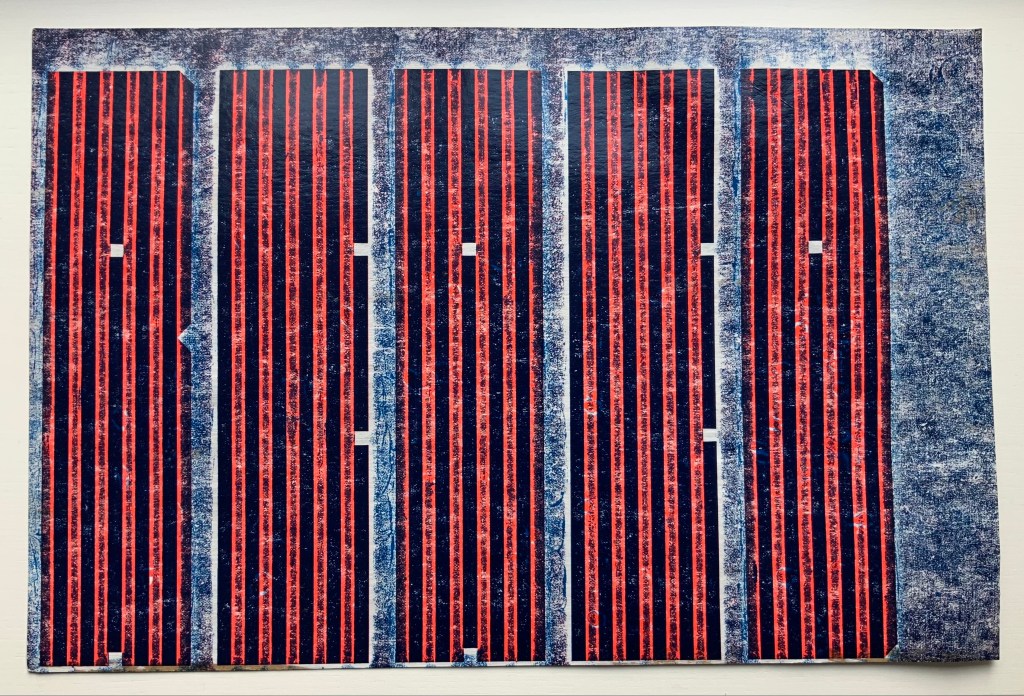

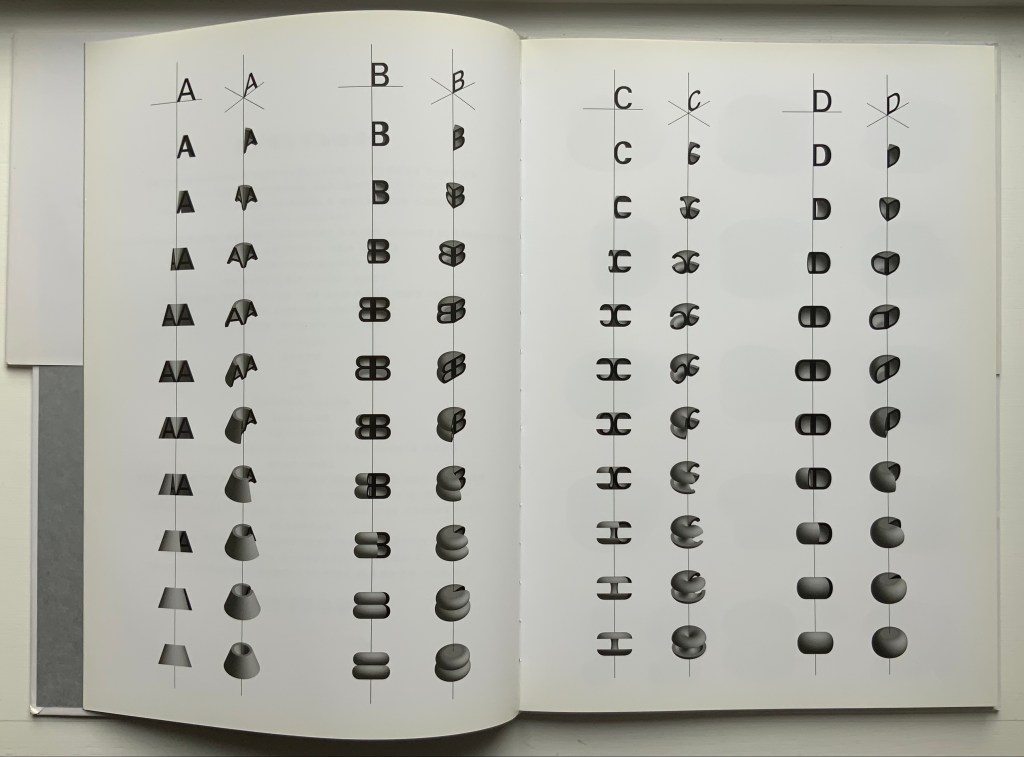

Photo of Between the Lines (pp. 12-13): Books On Books Collection.

Between the Lines‘ presentation of the works is spectacular. Recalling the effect in The Book Made Art (above), they seem to float three dimensionally on the page. The detail photo of Unpacking my Library across a double-page spread offers a good example, especially when compared with the images above.

Photo of Between the Lines (pp.16-17): Books On Books Collection.

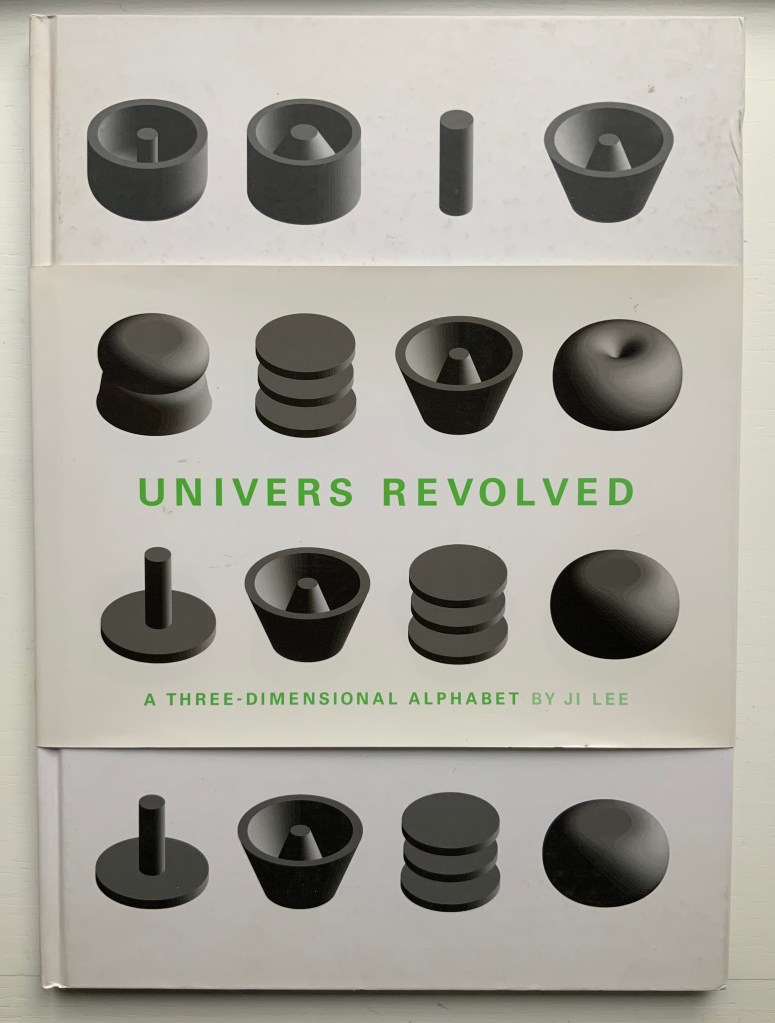

Between the Lines also provides the opportunity to end this entry with an image of the work incorporating an image of the author and his generosity toward his fellow bookworkers. Note in particular the reference to Michael Garzel, the monograph’s designer and creator of the typeface used so strikingly on the cover, for chapter titles and here in the heading “Acknowledgments”.

Photo of Between the Lines (pp. 4-5): Books On Books Collection.

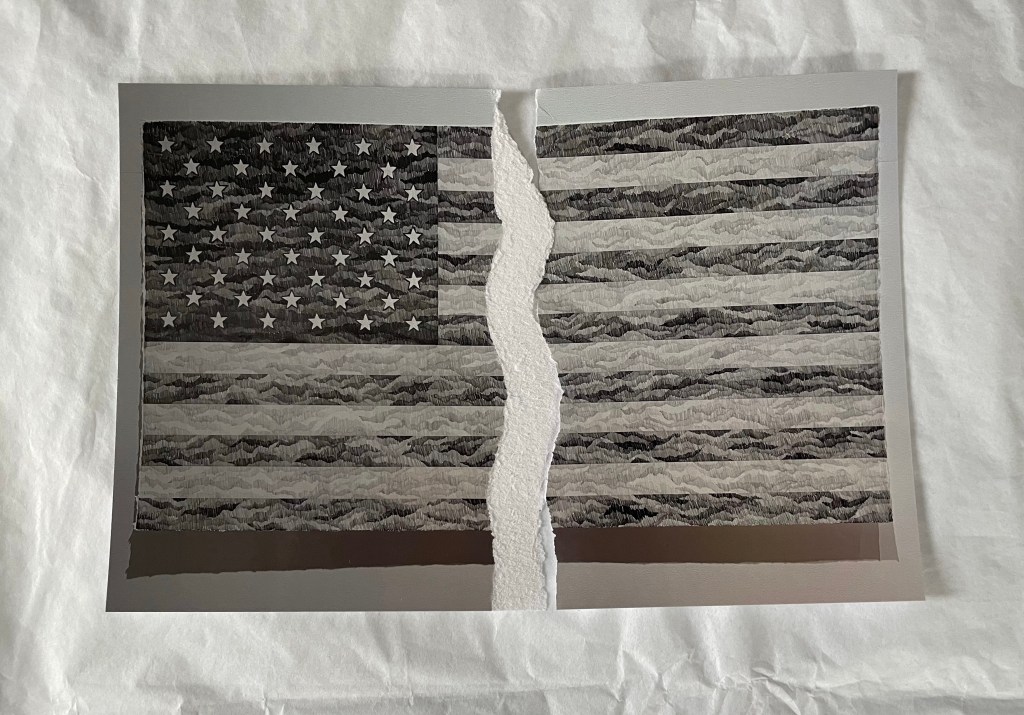

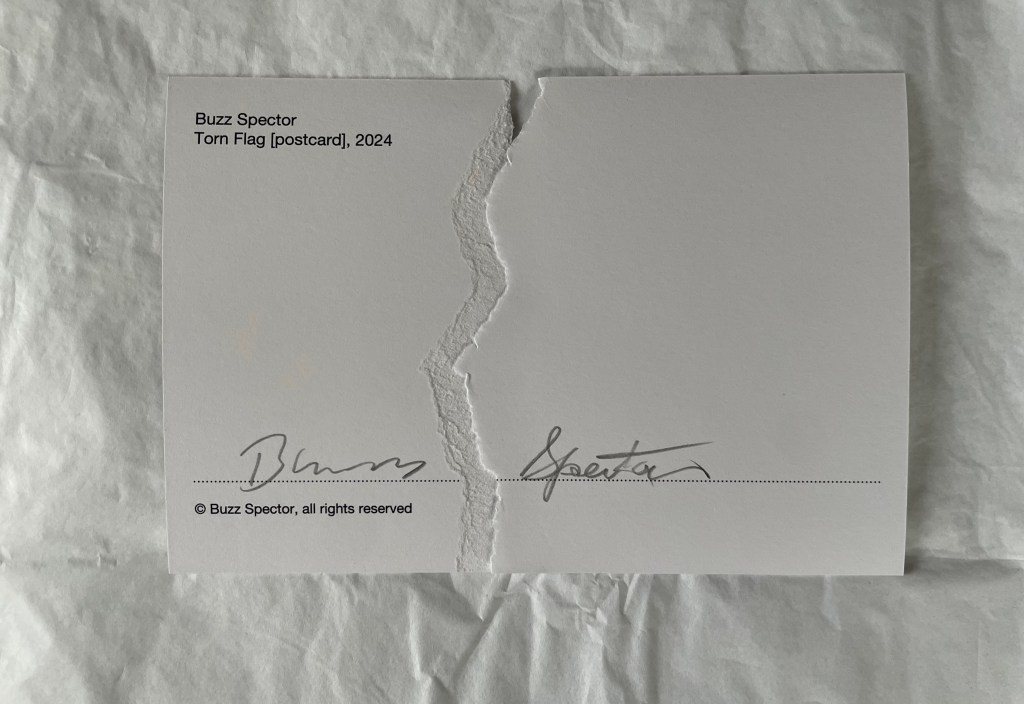

Torn Flag (2024)

Torn Flag (2024)

Buzz Spector

Postcard. Acquired from the artist, 26 February 2024.

Photos: Books On Books Collection.

Revisiting Spector’s works this time was prompted by an invitation from the Center for Book Arts to “BookTalk: Full Dress or Half Dress, Not Casual with Buzz Spector” on 8 October 2024. The postcard reproduces the drawing Torn Flag (2022), a 565 × 1118 mm drawing (graphite on paper) that appeared in the Zolla/Lieberman Gallery. Spector describes the postcard as an “(informal) edition … Elegy to the Divided States”. Ephemeral though the postcard may be, its tearing makes a self-reflexive artistic gesture. But it also serves as an injunction: Vote. Always.

Revised entry: 7 October 2024; 24 September 2021; original entry, 31 March 2020.

Further Reading

“Buzz Spector“, Bookmarking Book Art, 12 March 2016.

Baran, Jessica. 16 March 2021. “Showing What Has Been Forgotten“. Art in America. Accessed 23 September 2021.

Benezra, Neal. “Buzz Spector: The Library of Babel and Other Works“, [exhibition] 16 February – 17 April 1988, The Art Institute of Chicago. Accessed 26 March 2020.

Davids, Betsy, and Jim Petrillo. “The Artist as Book Printer: Four Short Courses” in Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, edited by Joan Lyons (Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1985), p. 160.

Drucker, Johanna. 2004. The Century of Artists’ Books [Second edition] ed. New York City: Granary Books. See pages 118-19 for perceptive comments on Spector’s A Passage (1994) and his method of torn pages.

Krauss, Rosalind. “A Voyage on the North Sea”: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 1999). Accessed 26 March 2020.

Lippard, Lucy. “New Artist’s Books” in Artists’ Books. A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook, edited by Joan Lyons (Rochester, NY: Visual Studies Workshop Press,1985), p. 53.

Mathews, Emily, and Sylvia Page. “Off the Shelf and Into the Gallery: Librarians on Spector”, Buzz Spector: Off the Shelf, Grunwald Gallery of Art, October 19 — November 16, 2012 (Bloomington, IN: Grunwald Gallery of Art, Indiana University, 2012), pp. 9-15.

Otten, Liam. “A sea of torn pages“, The Source, Washington University in St. Louis, 26 February 2010. Accessed 26 March 2020.

Perloff, Nancy. 2016. Explodity : Sound, Image, and Word in Russian Futurist Book Art. Los Angeles, California: Getty Research Institute. See pages 179-81 for perceptive comments on Spector’s A Passage (1994), a variant on biblioclasm and example of what Spector calls “a ‘conceptual purity’ because it engages completely with the book as a book.” (p.180)

Perrault, John. “Some Thoughts on Books as Art” in Artists Books, Moore College of Art, 23 March – 20 April 1973, curated by Dianne Perry Vanderlip (Philadelphia, PA: Moore College of Art, 1973), p. 21.

Platzker, David. “Marcel Broodthaers : A Voyage on the North Sea”, Specific Object, New York, New York, 28 January — 20 March 2009. Accessed 31 March 2020.

Ray, Ashley. 28 December 2020. “At the Saint Louis Art Museum, artist Buzz Spector considers literature by playing editor“. St. Louis Magazine. Accessed 23 September 2021.

Schlesinger, Kyle. “The Missing Book”, Buzz Spector: Off the Shelf, Grunwald Gallery of Art, October 19 — November 16, 2012 (Bloomington, IN: Grunwald Gallery of Art, Indiana University, 2012), pp. 17-25.

Spector, Buzz. “Going Over the Books” in The Book Maker’s Desire (Pasadena, CA: Umbrella Editions, 1995), p. 8.

Spector, Buzz. “Art Readings” in The Book Maker’s Desire (Pasadena, CA: Umbrella Editions, 1995), p. 13.

Spector, Buzz. “I stack things. I tear stuff up”, Buzz Spector: Shelf Life: selected works, Bruno David Gallery, January 22 — March 6, 2010 (Saint Louis, MO: Bruno David Gallery, 2010).

Spector, Buzz. 25 March 2021. “Art Speaks“. Saint Louis Art Museum. Video series of artists’ talks. Accessed 23 August 2021.