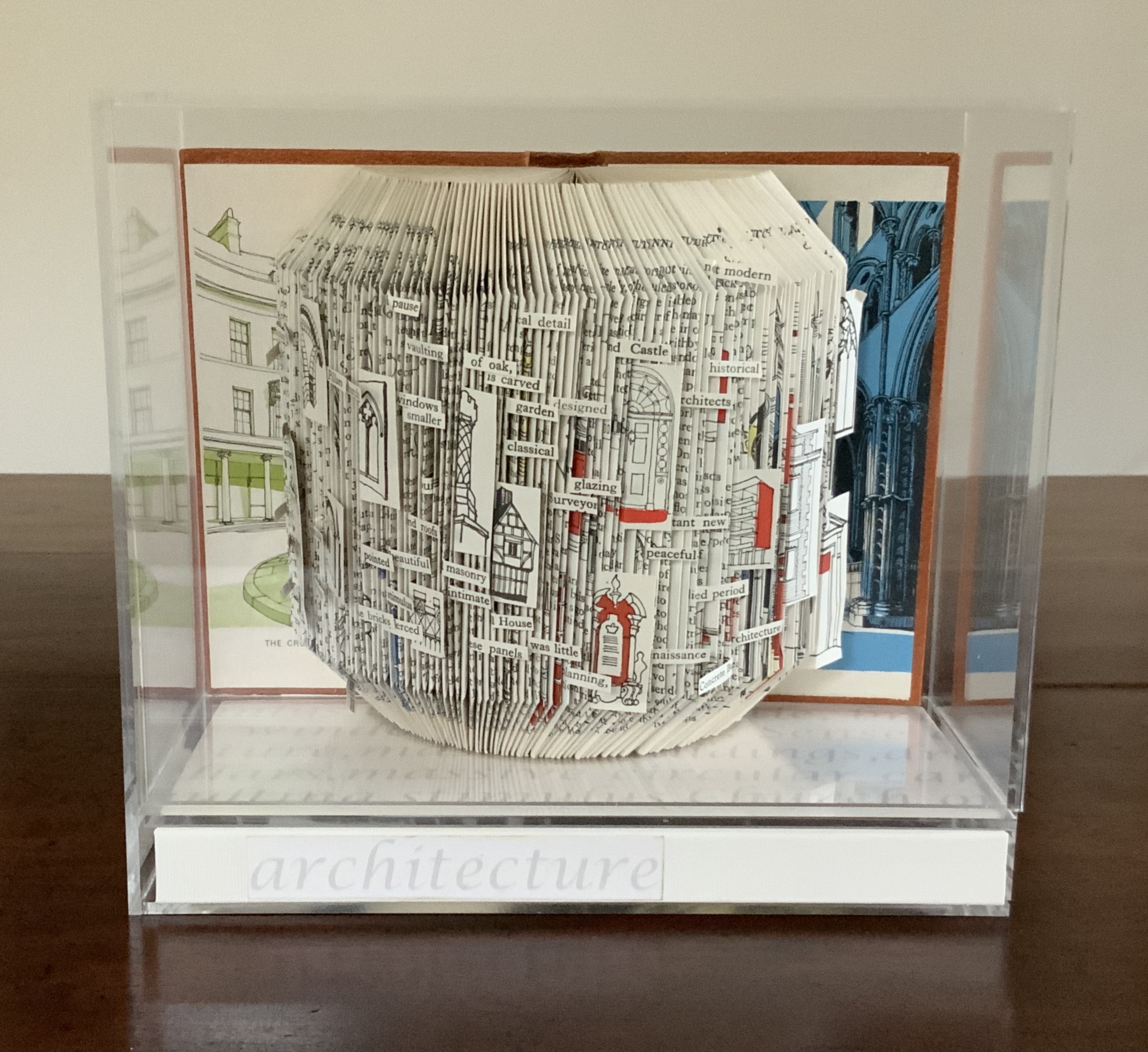

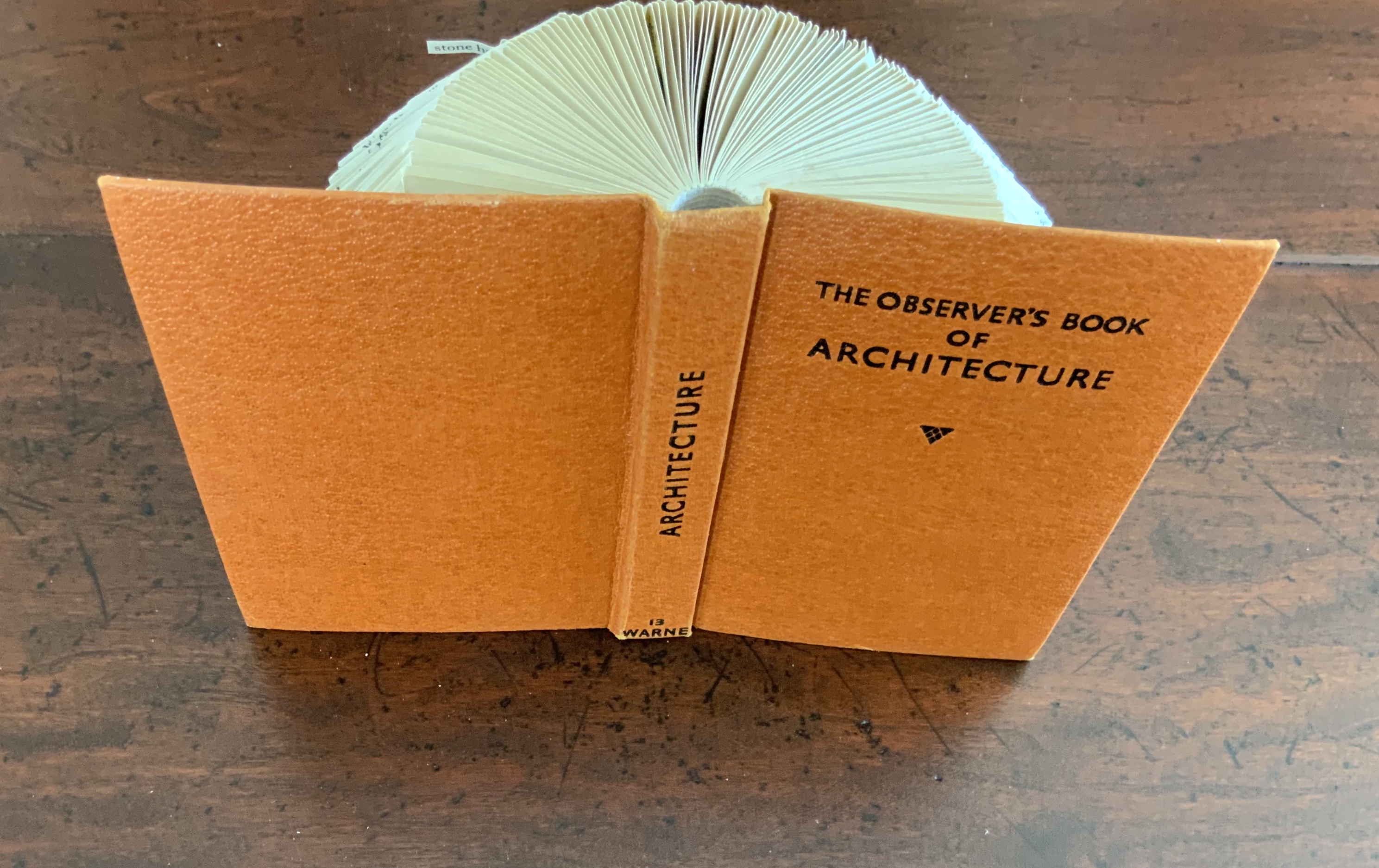

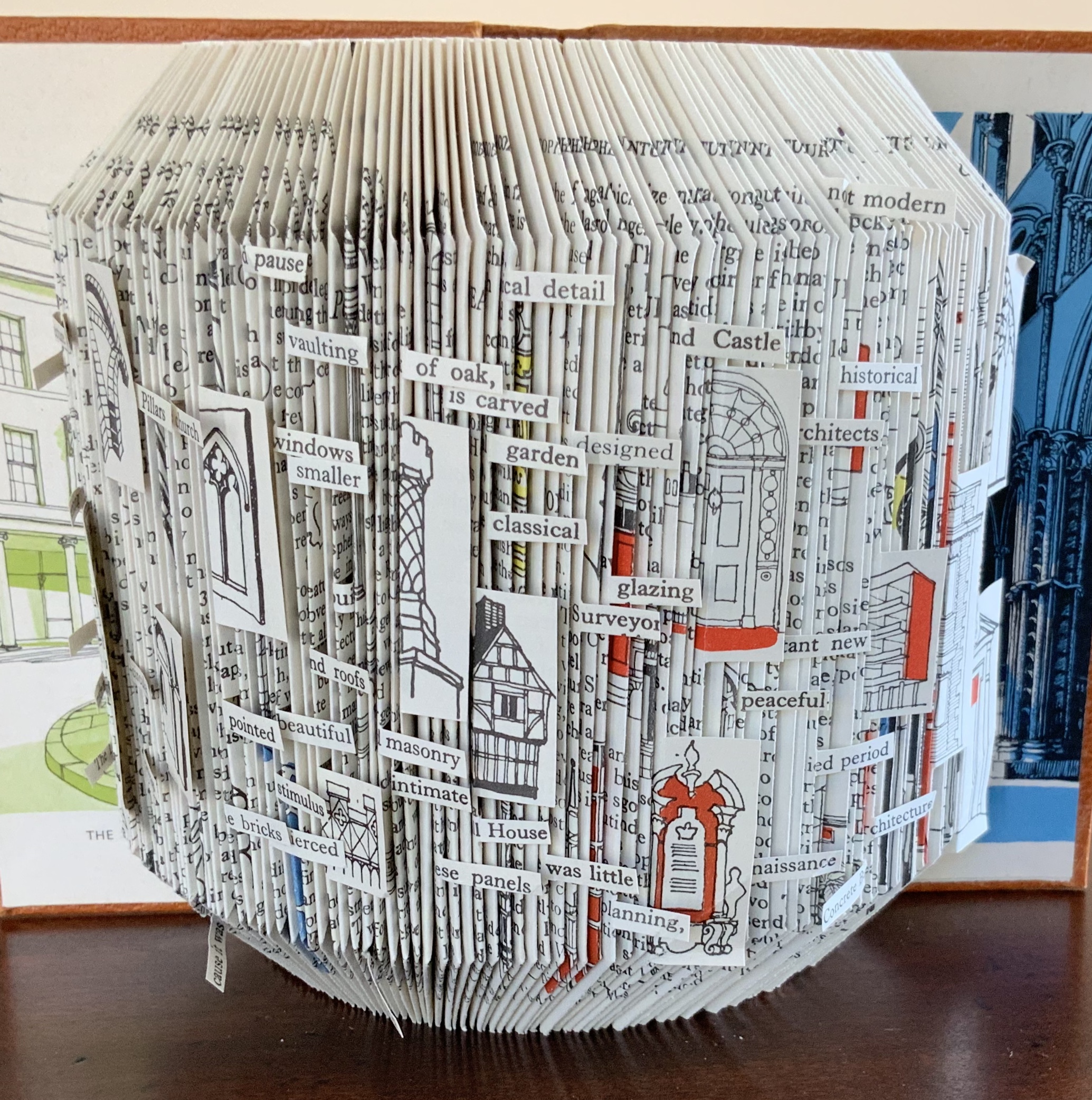

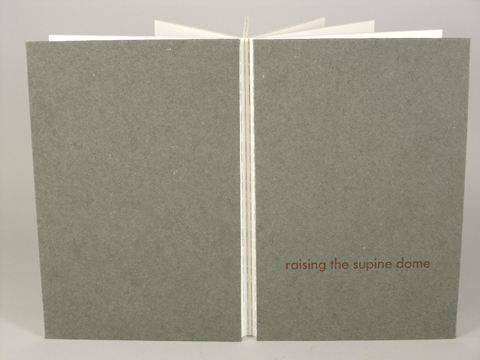

Champ Fleury: Art et Science de la Vrai Proportion des Lettres (1529)

Champ Fleury by Geofroy Tory Translated into English and Annotated by George B. Ives, Designed and printed by Bruce Rogers (1529)[1927]

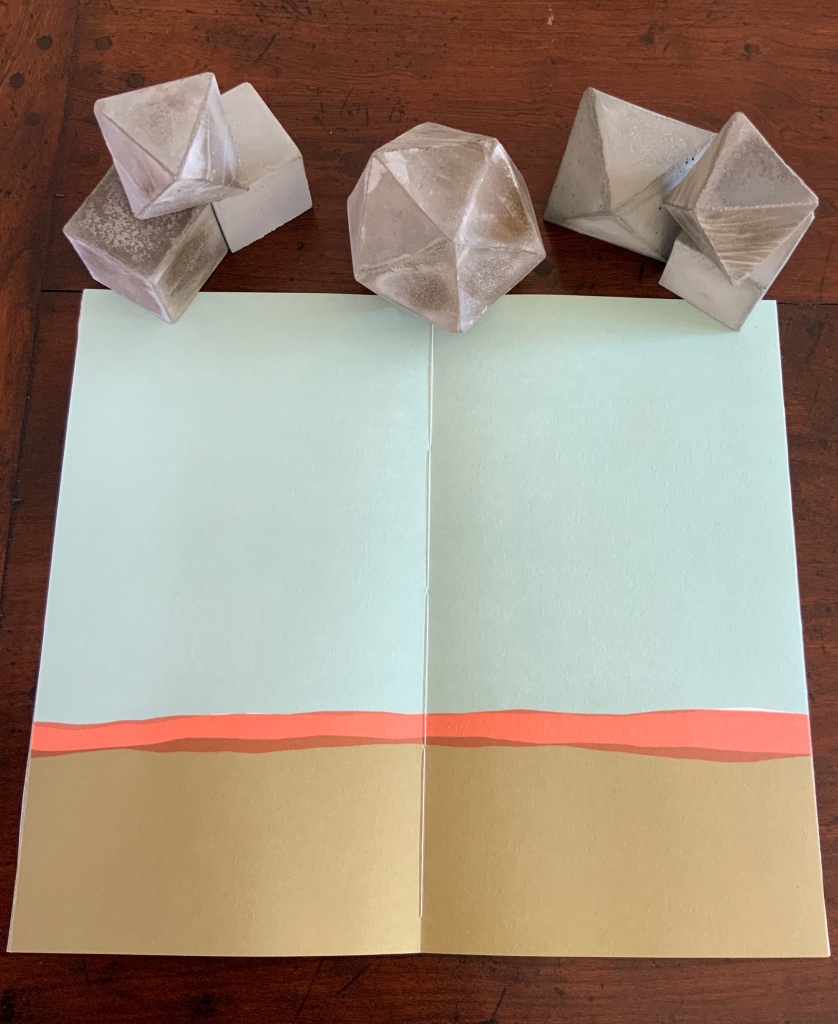

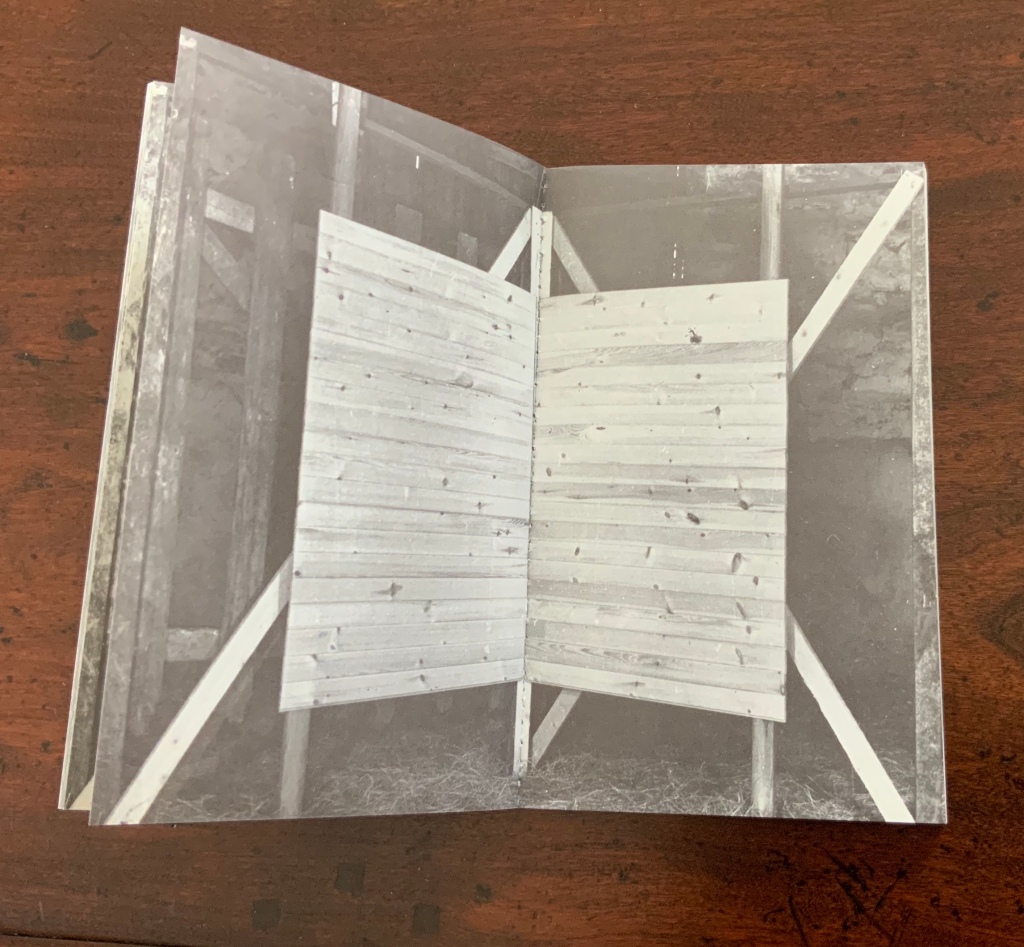

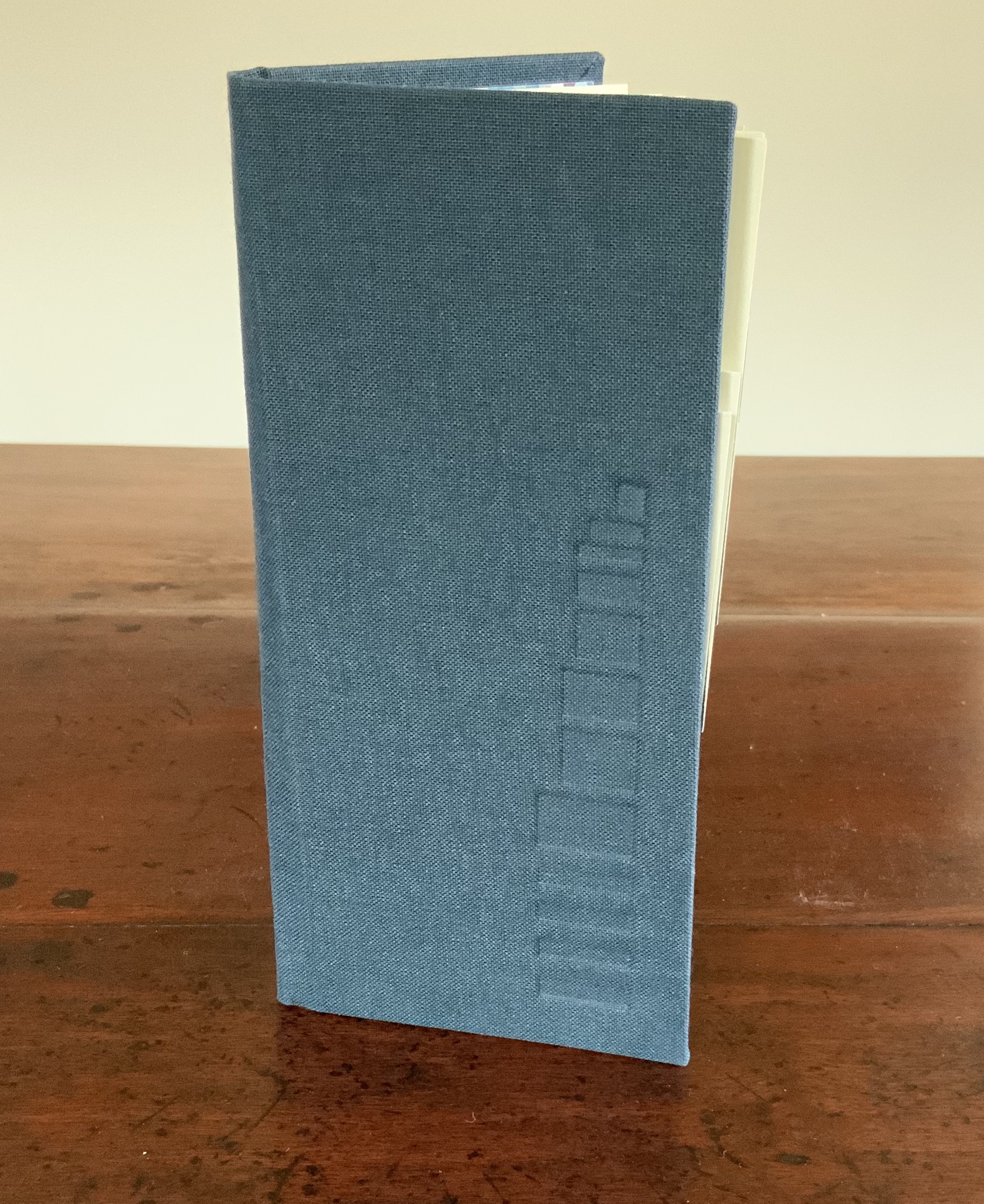

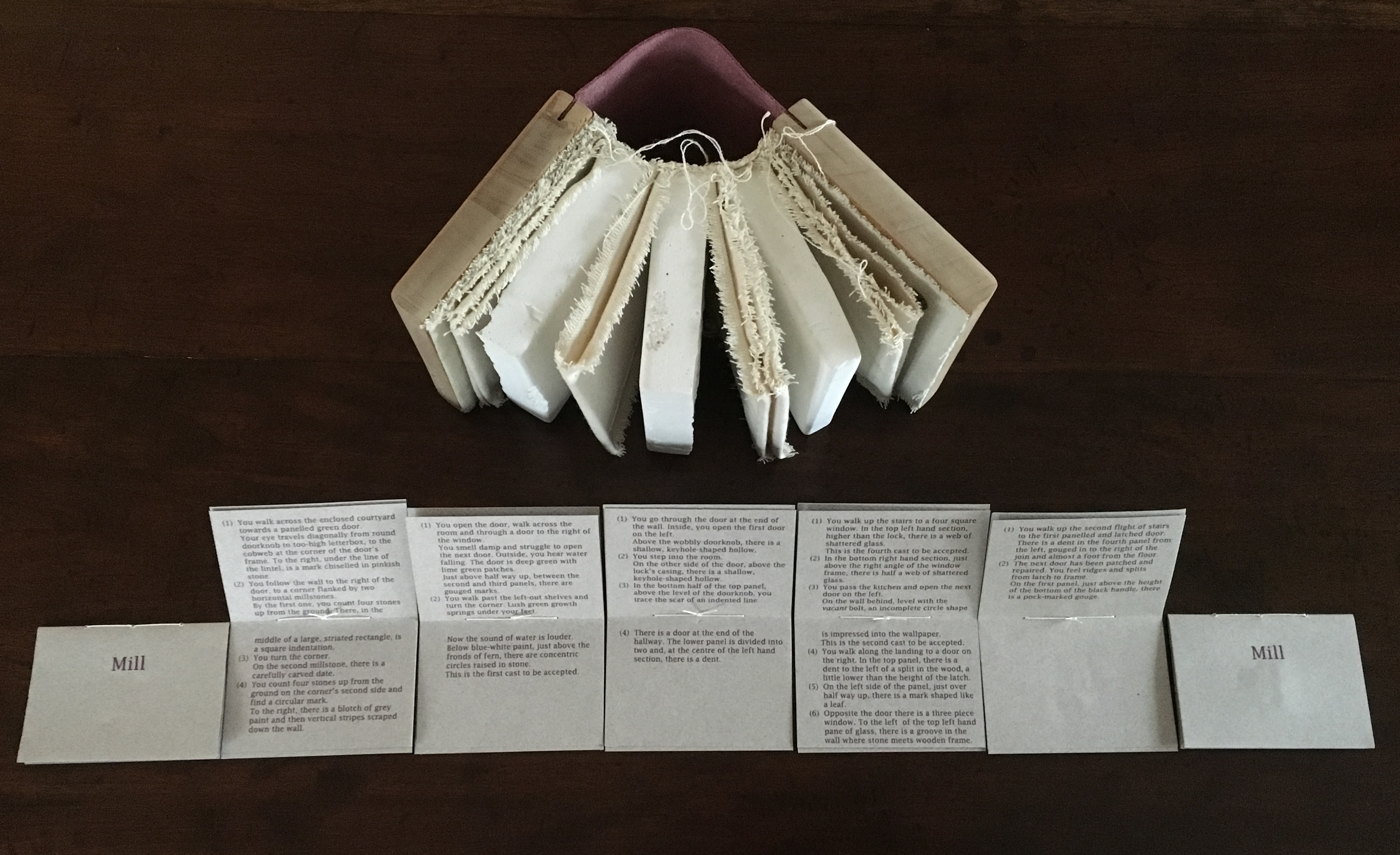

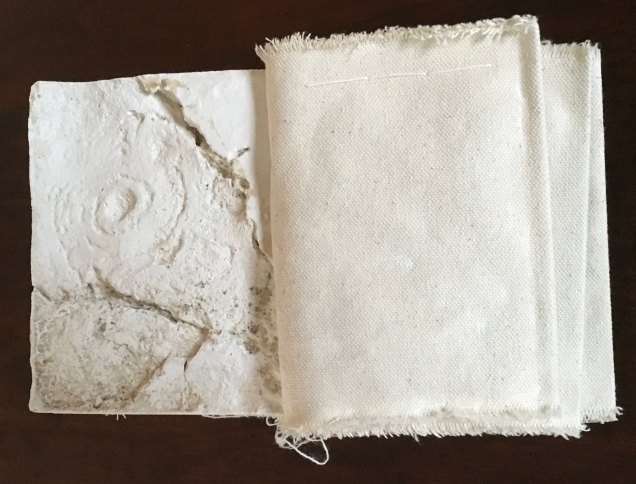

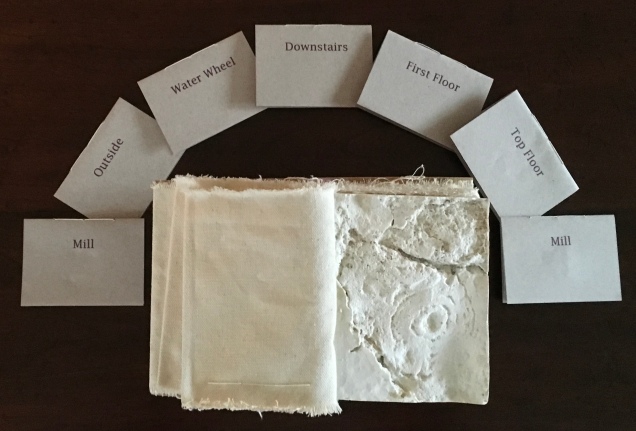

Slipcase, dust jacket over casebound, vellum-backed decorated paper-covered boards, gilt-stamped spine and gilt top edge. H320 x W224 mm, 234 pages. One of 390 copies. One of only ten books printed in the original foundry Centaur type by Rogers. Acquired from Donald A. Heald Rare Books, 26 May 2021.

and

Champ Fleury: Art et Science de la Vrai Proportion des Lettres (1529)[1998]

Geofroy Tory

Sewn paperback, glued to black card cover with deep flaps. H250 x W172mm, 192 pages. Acquired from Antiquariaat Schot, 19 April 2021.

Photos of the books: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the books: © 1927 The Grolier Club. © Bibliothéque de l’Image.

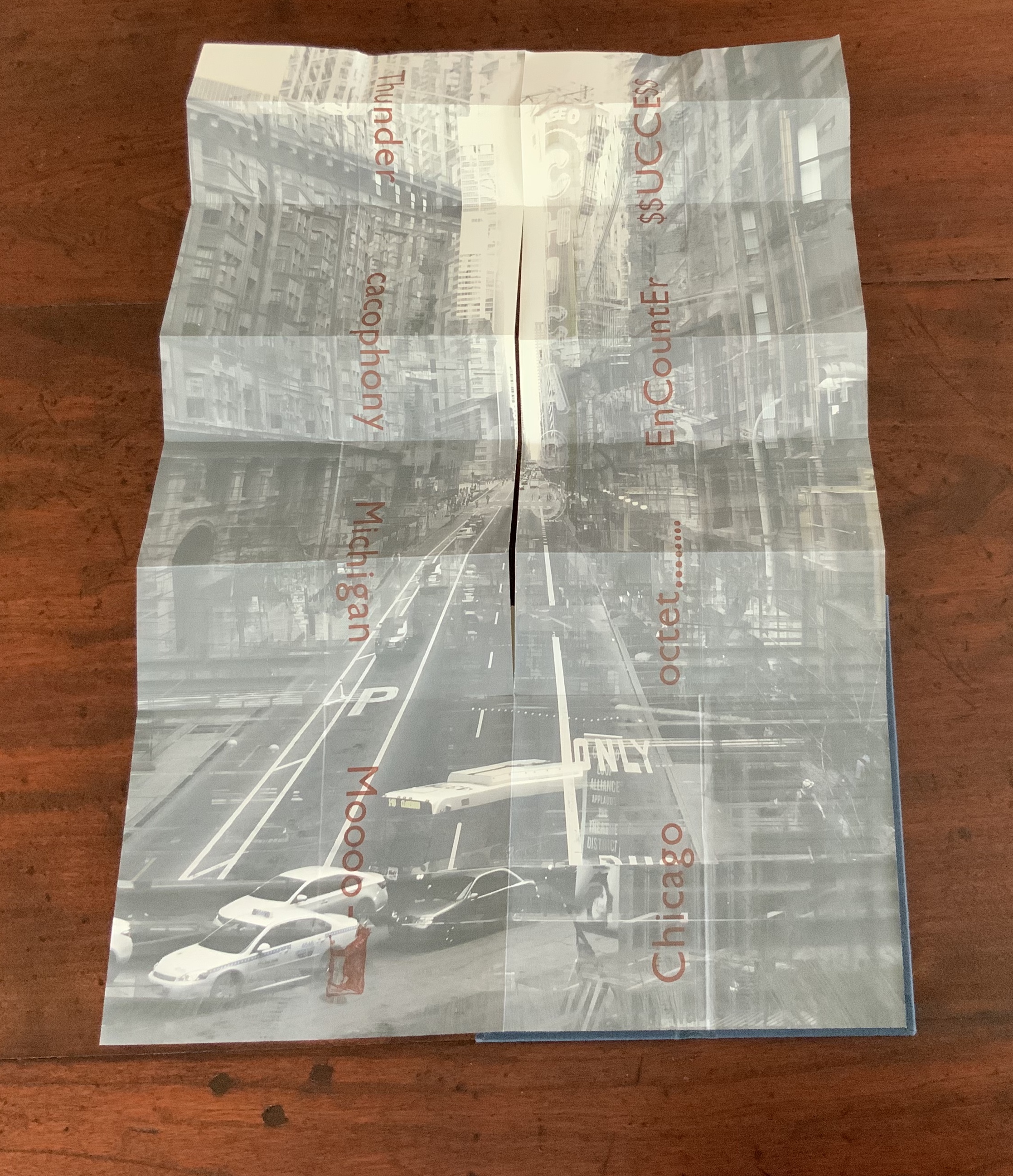

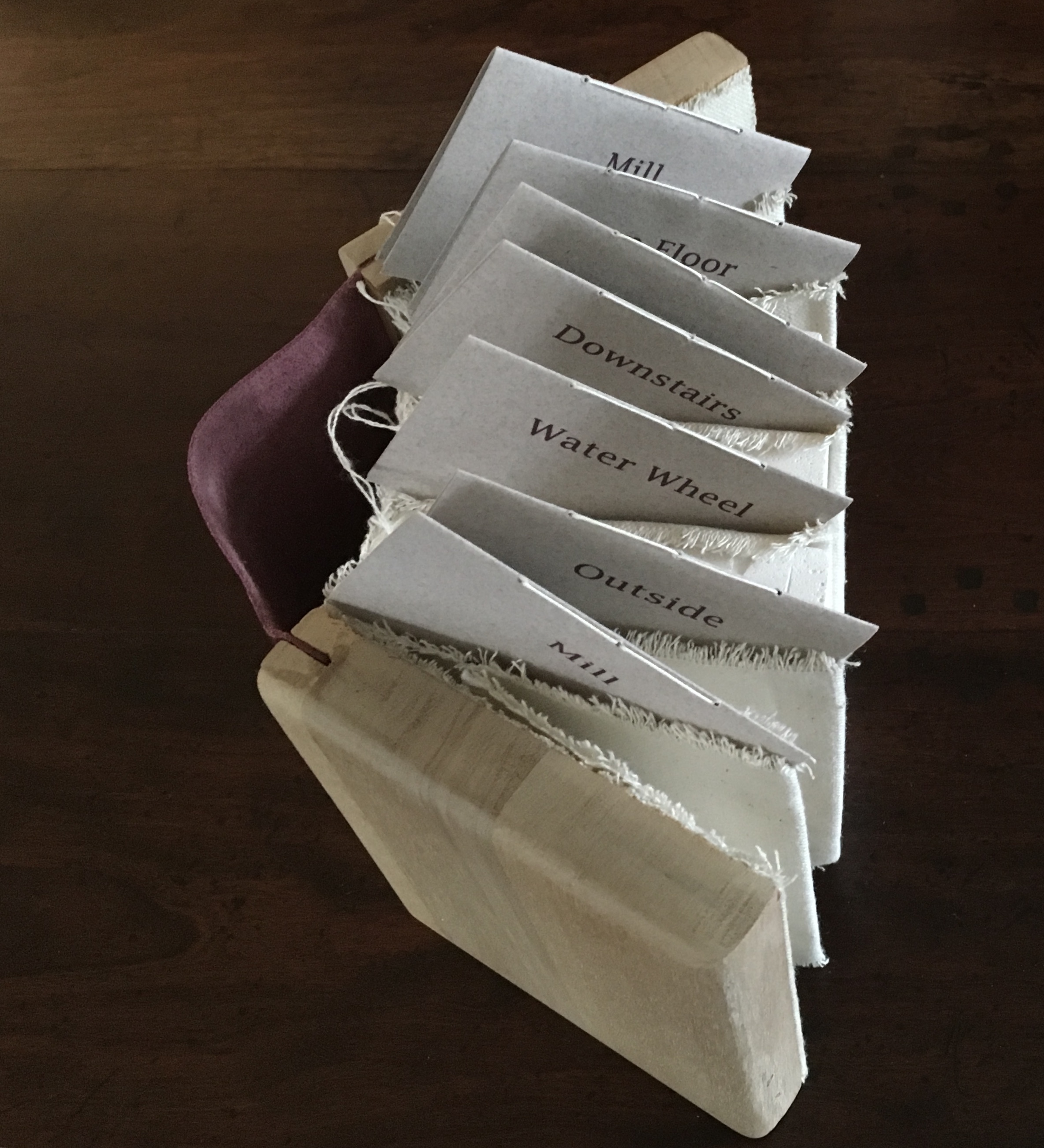

The art of the alphabet seems to be a rite of passage for graphic artists. Perhaps it is that art and the alphabet find common ground in the urge to make sense of the world. Perhaps it’s that the alphabet’s invention, development and artistic treatment present a rich tradition for artists to follow or challenge. Perhaps it’s that letterforms and the alphabet offer raw material, subject and organizing principle all in one. Semic or asemic. Calligraphic, typographic or even plastic. Representational or abstract. All are options. But most often, something bookish results. From Islam Aly’s 28 Letters (2013) to Ludwig Zeller’s Alphacollage (1979), a significant part of the Books On Books Collection is taken up with book art based on the ABCs and letterforms. The Collection’s two facsimiles of Geofroy Tory’s Champ Fleury provide a useful historical backdrop that throws into relief several of the Collection’s works and their performance of this rite of passage.

Left to right: double-page spread and cover from Aly’s 28 Letters; A from Zeller’s Alphacollage. Photos of the works: Books On Books Collection. Copyrights in the works: © Islam Aly. © Ludwig Zeller.

Geofroy Tory de Bourges (c.1480-1533) straddles the letters of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Appointed by François I in 1530 as his printer, Tory operated on the Petit Pont under the sign of le Pot cassé (“the broken pot”) and was known for his workshop’s handwritten Book of Hours (1524). Rooted in the horae tradition reaching back to the 13th century, Tory’s Book of Hours is an early-to-mid-Renaissance version of its predecessors. As beautiful as his Book of Hours is, Champ Fleury (1529) became his best known work. Authored and designed by Tory, it was produced by hand typesetting and letterpress printing in Paris with Giles Gourmont. Printed less than 100 years after Gutenberg’s innovation, Champ Fleury represents the printed book toddling out of its incunabula period.

Book of Hours

Geofroy Tory (1524)

Bound in the 18th century, 113 leaves of vellum. Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection (Library of Congress). Accessed 30 May 2021.

Title page: 1529 original in the Bibliothèque national de France; 1927 translation & facsimile © 1927 The Grolier Club; 1998 facsimile © Bibliothéque de l’Image. Photos of the latter two books: Books On Books Collection.

According to Jeremy Norman’s History of Information site, the first separate printed title page appeared in 1463. Subject indices date back to the 13th century, originating at the University of Paris, and the first printed indices, to 1470. Champ Fleury‘s front matter boasts a title page, two prefaces to the reader, a statement of the King’s Privilege awarded for the book for ten years (a forerunner to the copyright page), a name index without location references and a subject index with folio references. Champ Fleury’s back matter consists of a colophon preceded by a lengthy appendix illustrating various forms of the alphabet (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, etc.).

Tory’s placement of the indices in the front matter rather than the back matter reflects the gradual development of the anatomy of the book towards the structure that would ultimately be codified in reference works like the Chicago Manual of Style. Paratextual elements like the title page, table of contents, page numbers, etc., did not spring up overnight. If, as Eric Havelock and others assert, society, the arts and culture are a superstructure erected on the foundation of the alphabet (see below), Champ Fleury and its “letterology” make for a particularly fitting exemplar of the book as an element of the superstructure arising from the alphabet.

Perhaps book artists sense this, which again leads to that alphabet art rite of passage and the elaborate variations on it. The illustration of various forms of the alphabet in the appendix also draws on another developing tradition: the typesetter/printer’s sample book advertising the firm’s fonts. Abecedaries and artist books have sprung from that tradition, too.

From left to right: Greek, Chaldaic, and Imperial Gothic letters from the 1998 facsimile. Photo of the book: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the book: © Bibliothéque de l’Image.

Tory was not the first to propose an art and science behind the letterforms of the alphabet. Predating his efforts were Giovanninno de’ Grassi (1390-1405), Felice Feliciano (1463), the Anonymous Chicagoensis and Anonymous Monachensis (1468?), Damianus Moyllus (1480), Fra Luca Pacioli (1509), Sigismondo Fanti (1514), Francesco Torniello (1517), Ludovico Arrighi (1522), Albrecht Dürer (1525) and Giovanni Battista Verini (1527). Leading up to Champ Fleury, these earlier efforts track the development of humanism. Arguably, Tory’s effort is a capstone, combining myth, allegory, metaphysics, geometry, linguistics, calligraphy, typography and cryptography.

Book One, concerned with the mythical origins of the French language, also addresses the fabled origins of the alphabet: the story of Jove, Io and Mercury behind the letters I and O and their claim to being the first letters and also the tale of Apollo’s accidental murder of Hyacinth explaining the letters A and Y and their similar claim. Two works in the Collection built on alphabet origin stories are Francisca Prieto’s Printed Matter series (2002-2008) William Joyce’s The Numberlys (2014), but many more follow in Champ Fleury’s art and science footsteps.

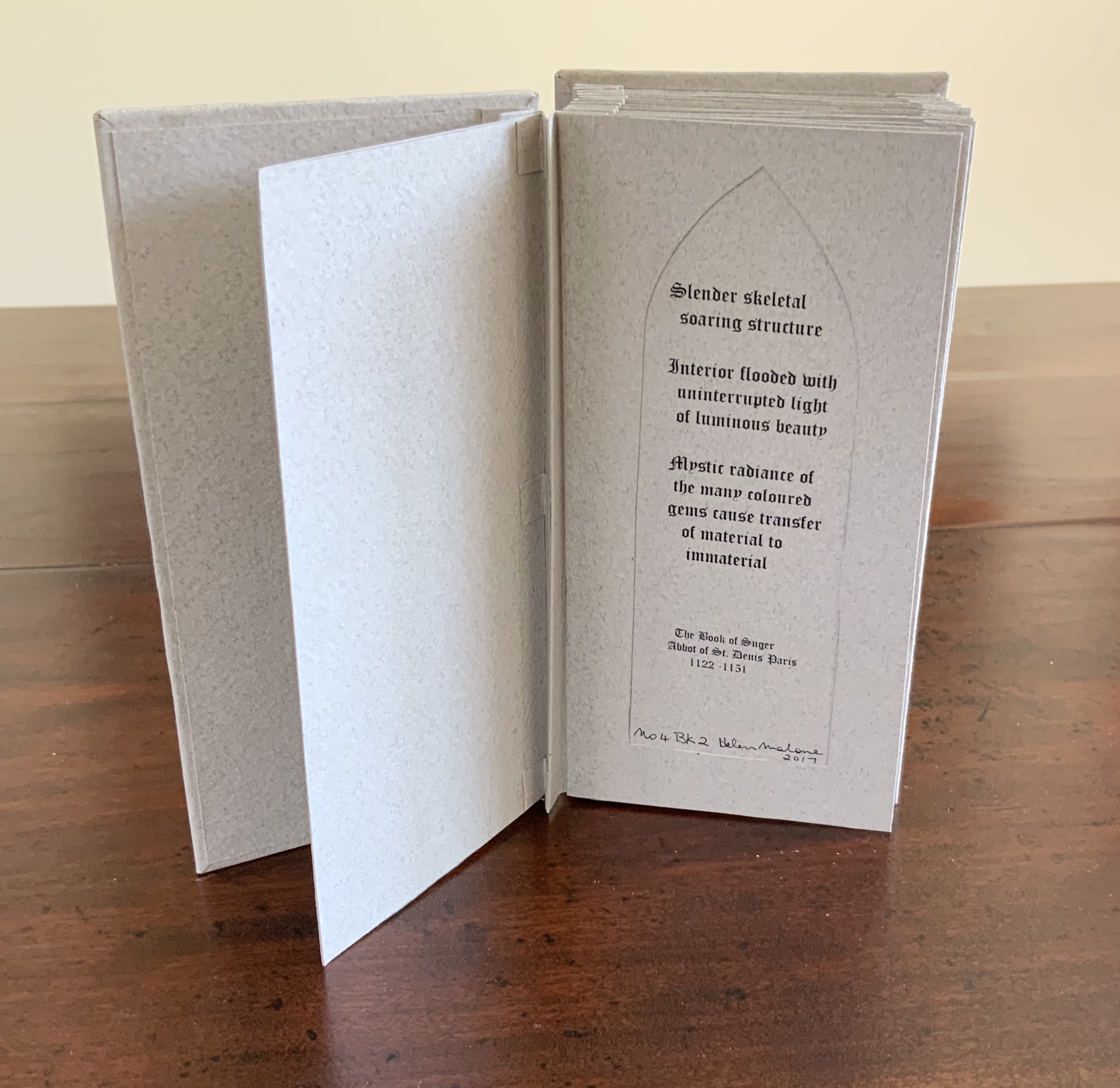

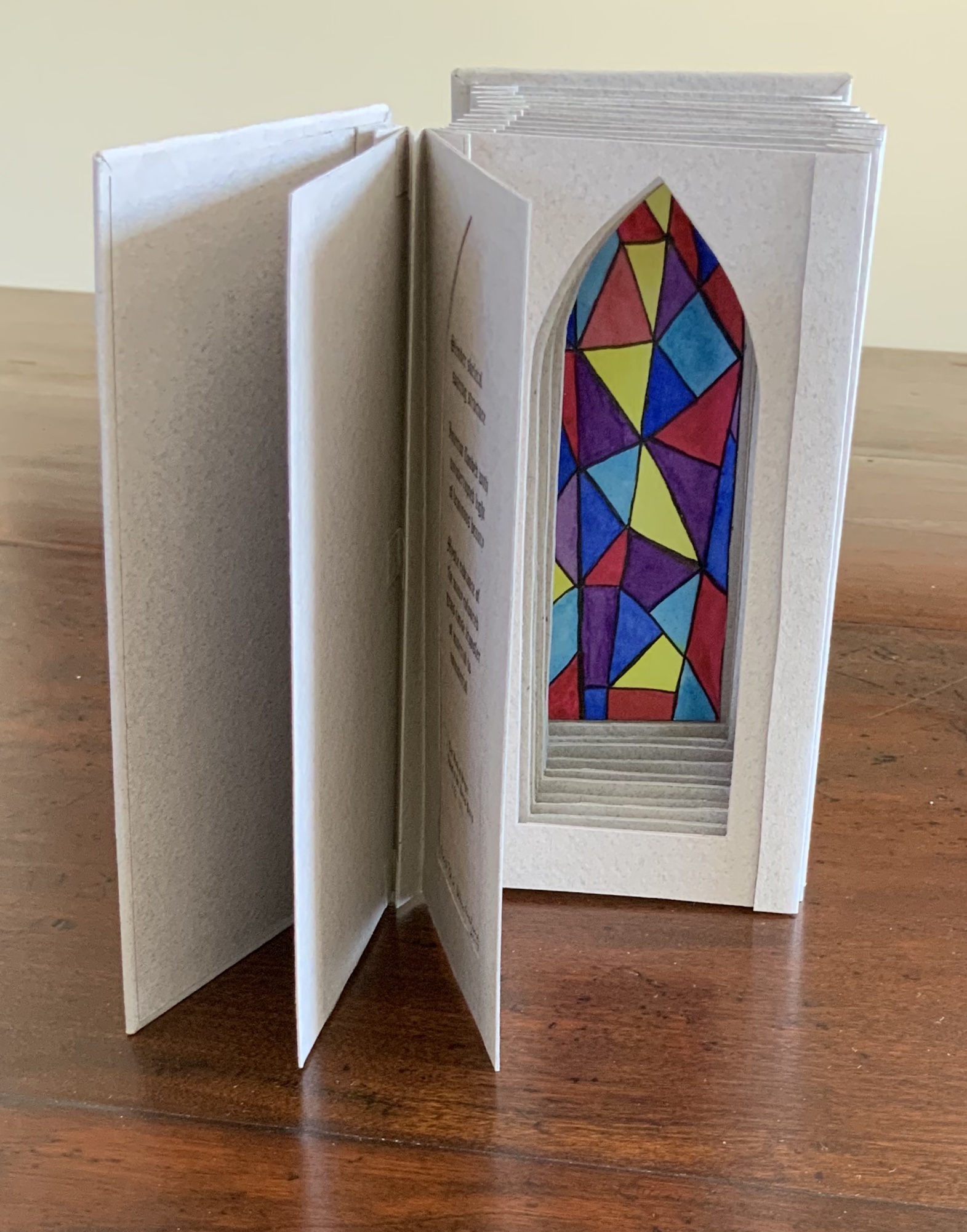

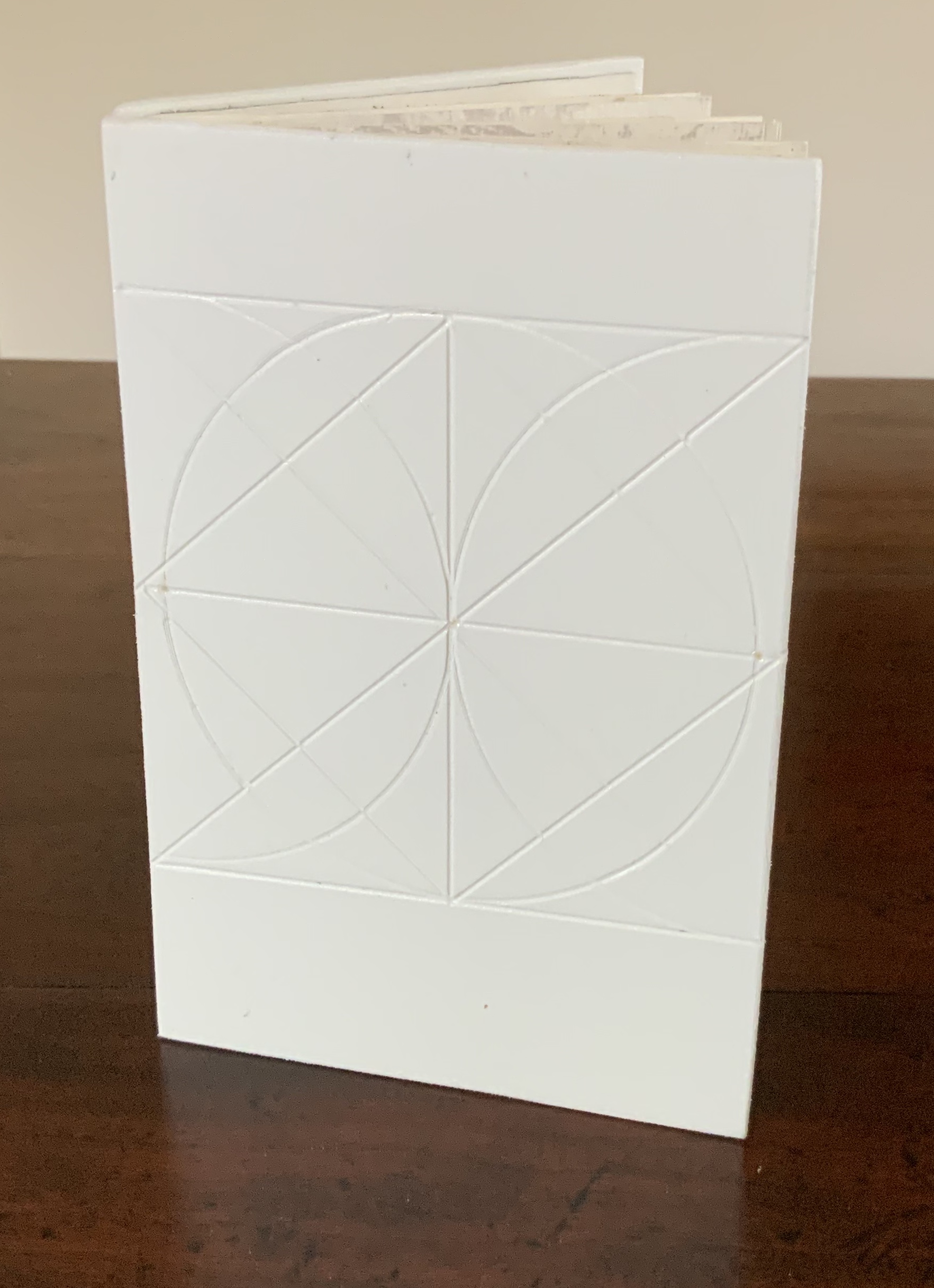

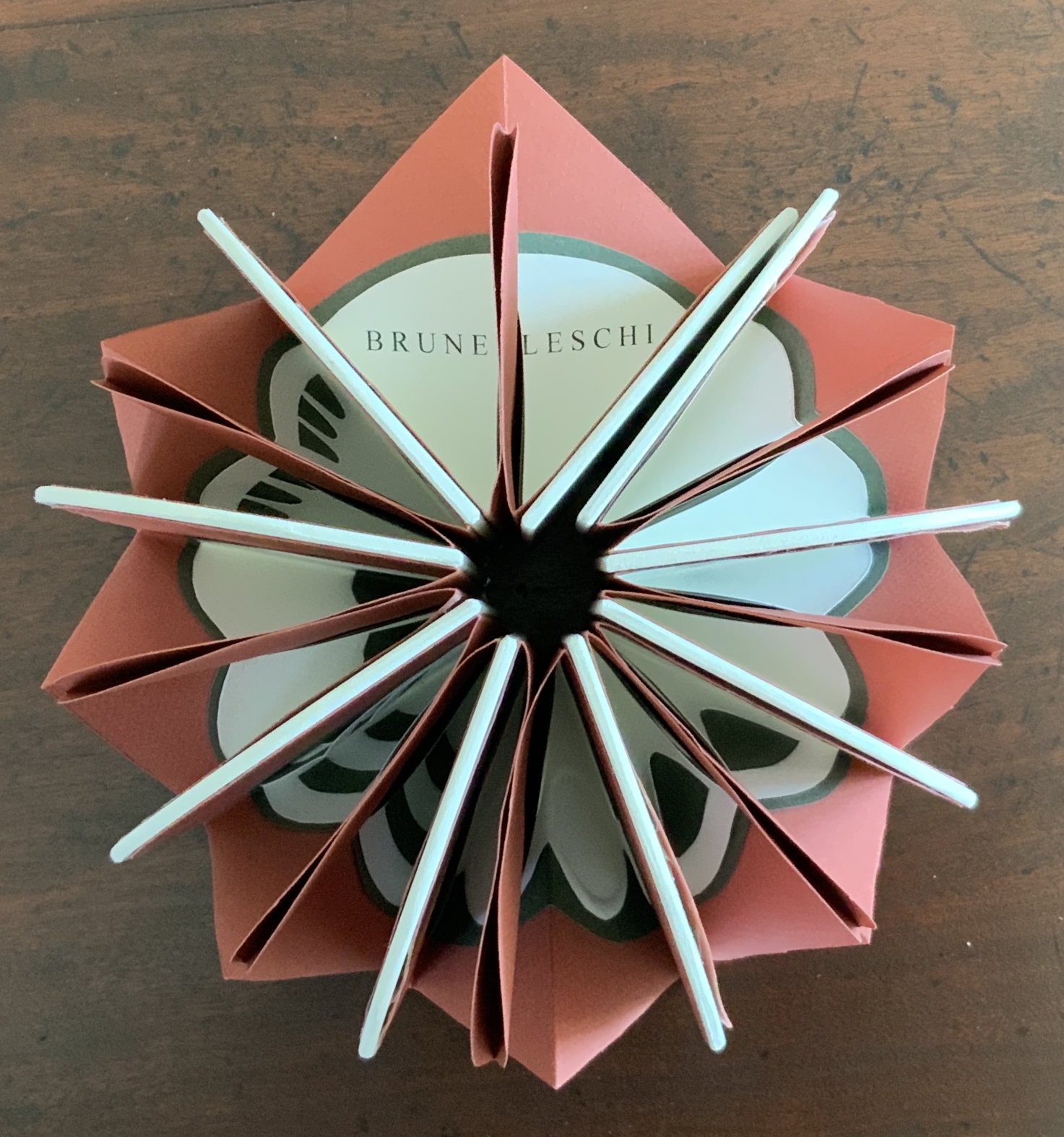

Tory’s late medieval/early Renaissance perspective gives way to 20th and 21st century poetics and phenomenology in most works of the Collection. Aaron Cohick’s The New Manifesto of the NewLights Press (third iteration) (2017) offers a good example. Another — closer to Tory’s moral and geometric perspective but of a more modern spirituality — is Jeffrey Morin and Steven Ferlauto’s Sacred Space (2003).

Clockwise from upper left: B+8 from Prieto’s Printed Matter series; cover of Joyce’s The Numberlys; double-page spread from Cohick’s A New Manifesto; Morin and Ferlauto’s Sacred Space. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © Francisca Prieto. © Michael Joyce and Christina Ellis. © Aaron Cohick. © Jeffrey Morin and Steven Ferlauto.

Compile all the abecedaries ever created and it would approximate the result of Adam and Eve’s task of naming all the creatures and things of the world. Leonard Baskin echoes that innocence in Hosie’s Alphabet (1972) with its words and animals supplied by his children. If Adam and Eve had had an alphabet, they might have been tempted into pareidolia, which is represented in the Collection by VUES/LUES: Un Abécédaire de Marion Bataille (2018) and Typographic Universe (2014) by Steven Heller and Gail Anderson. Heller and Anderson’s compendium extends to letters formed of natural and drawn objects from the real world, which Champ Fleury’s appendix foreshadows with its floral and fantastic alphabets.

Clockwise from upper left: Baskin, Hosie’s Alphabet letter H; Bataille’s VUES/LUES letter O & P; Ceol Ryder’s My Type of Film from Heller and Anderson’s Typographic Universe; Tory’s lettres fantastique and fleuries from 1998 facsimile.

Photos of the works: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © The Estate of Leonard Baskin; © Marion Bataille. © Ceol Ryder. © Steven Heller and Gail Anderson. © Bibliothéque de l’Image.

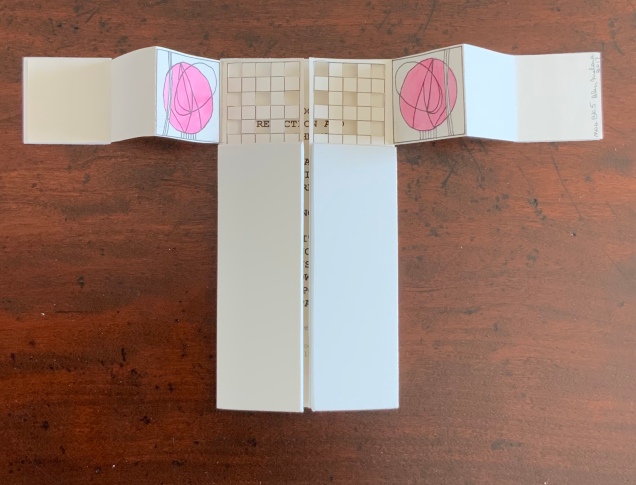

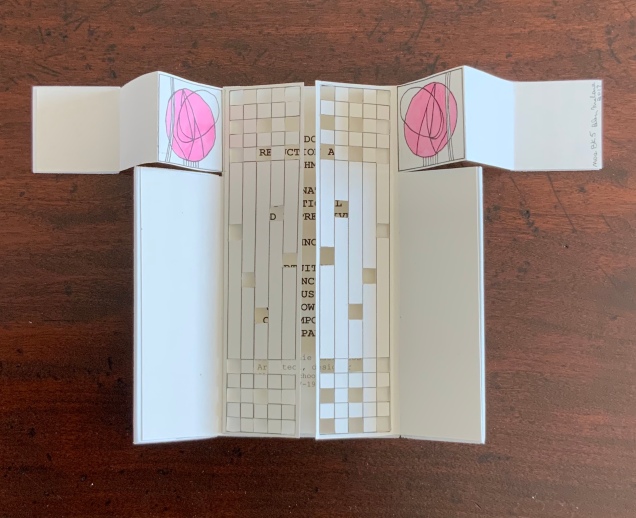

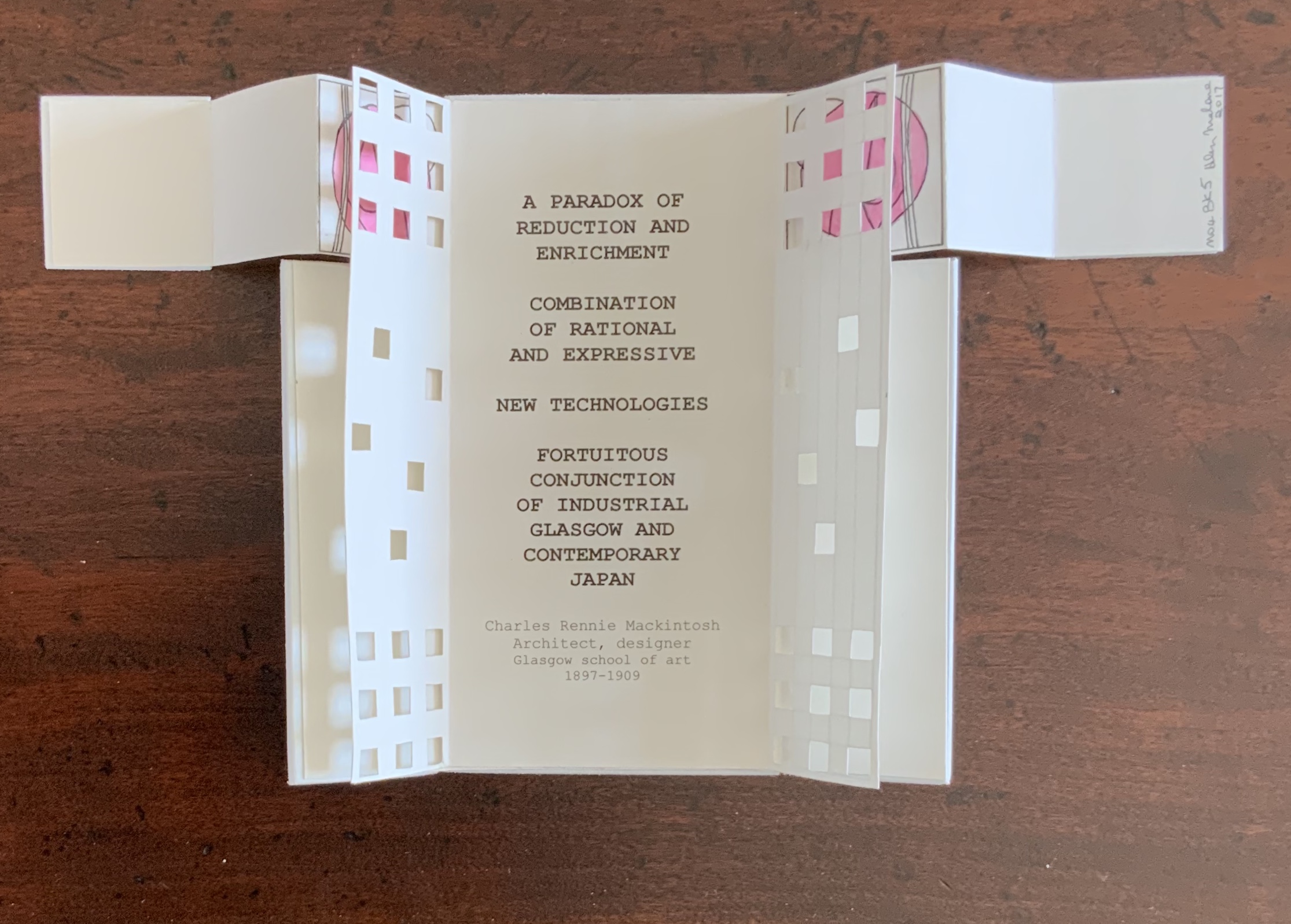

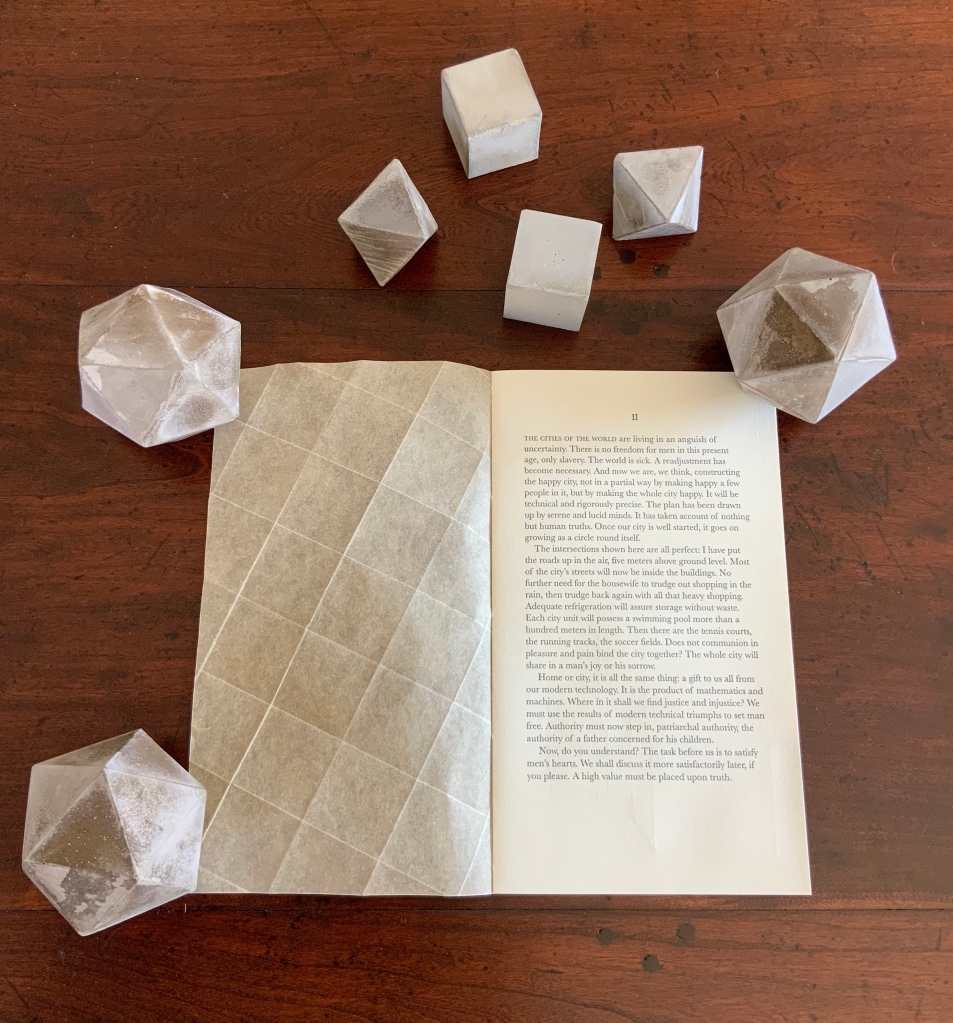

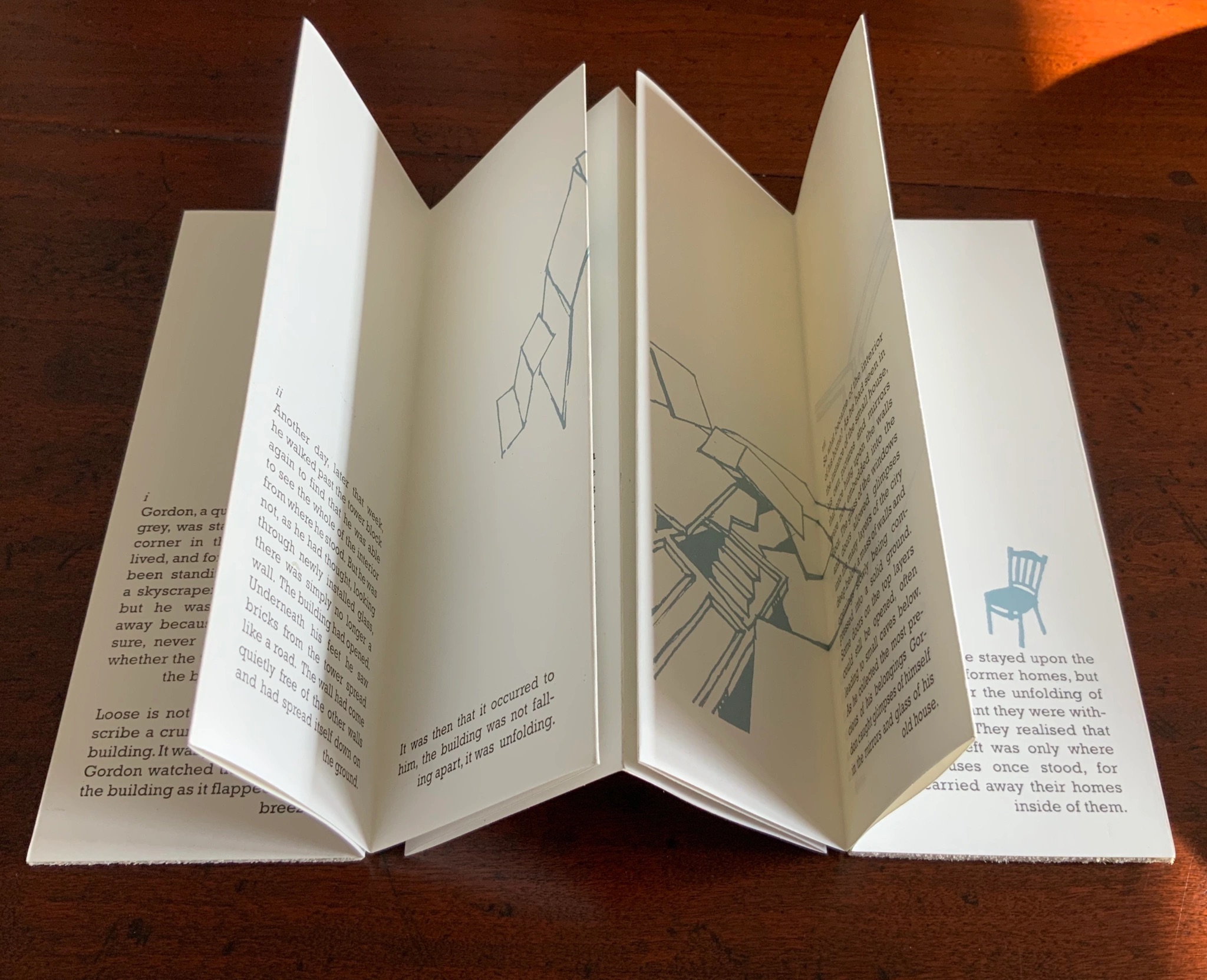

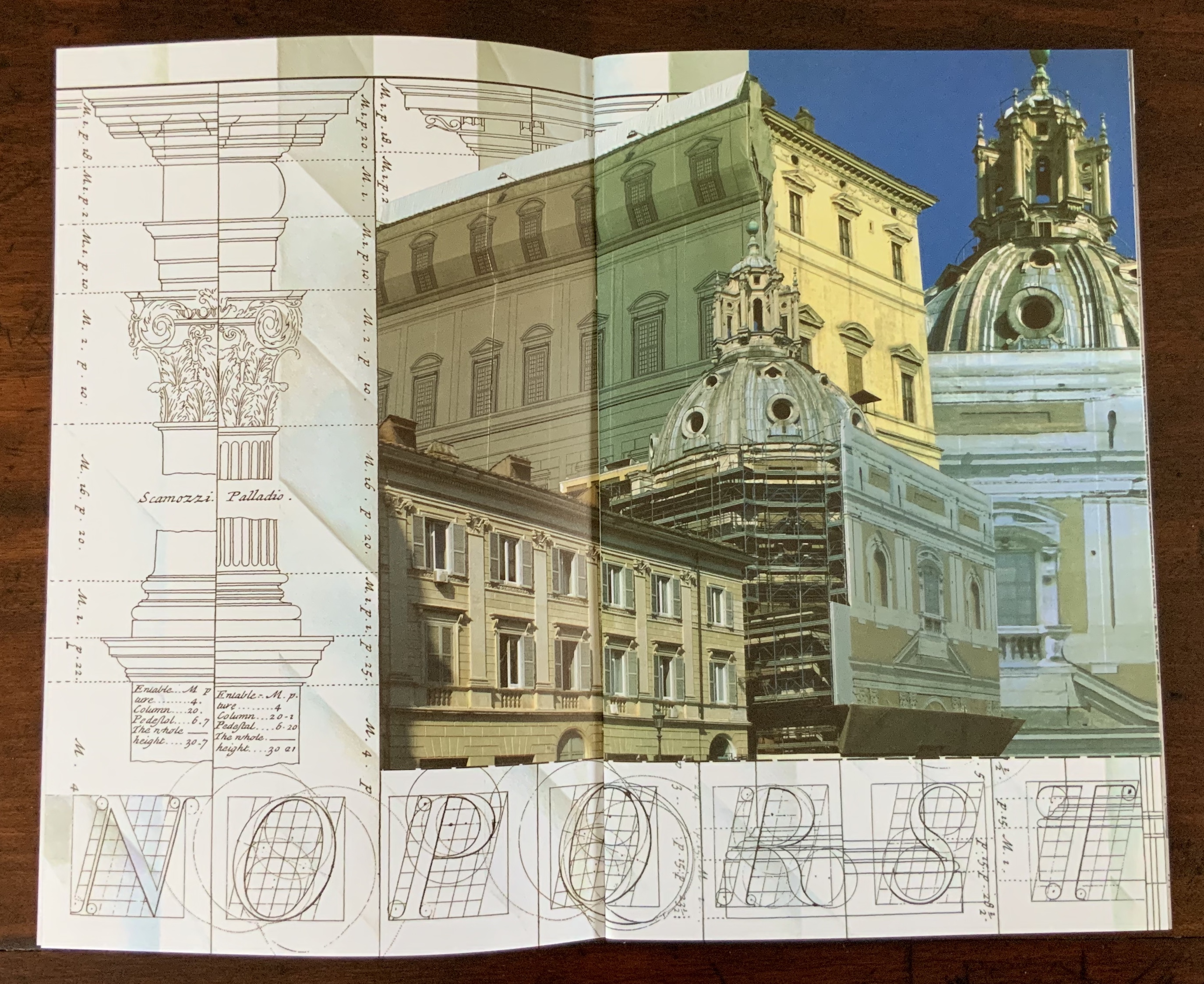

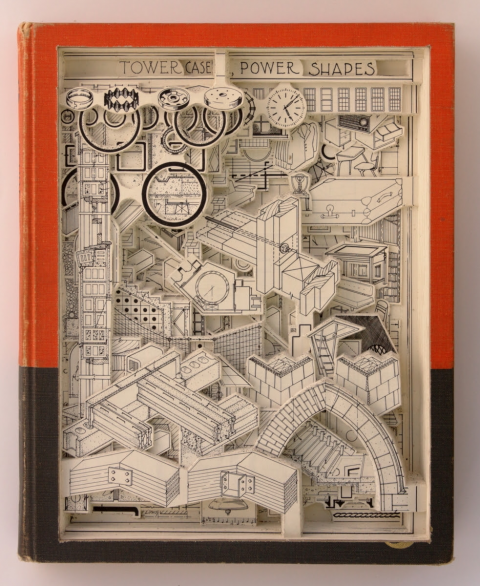

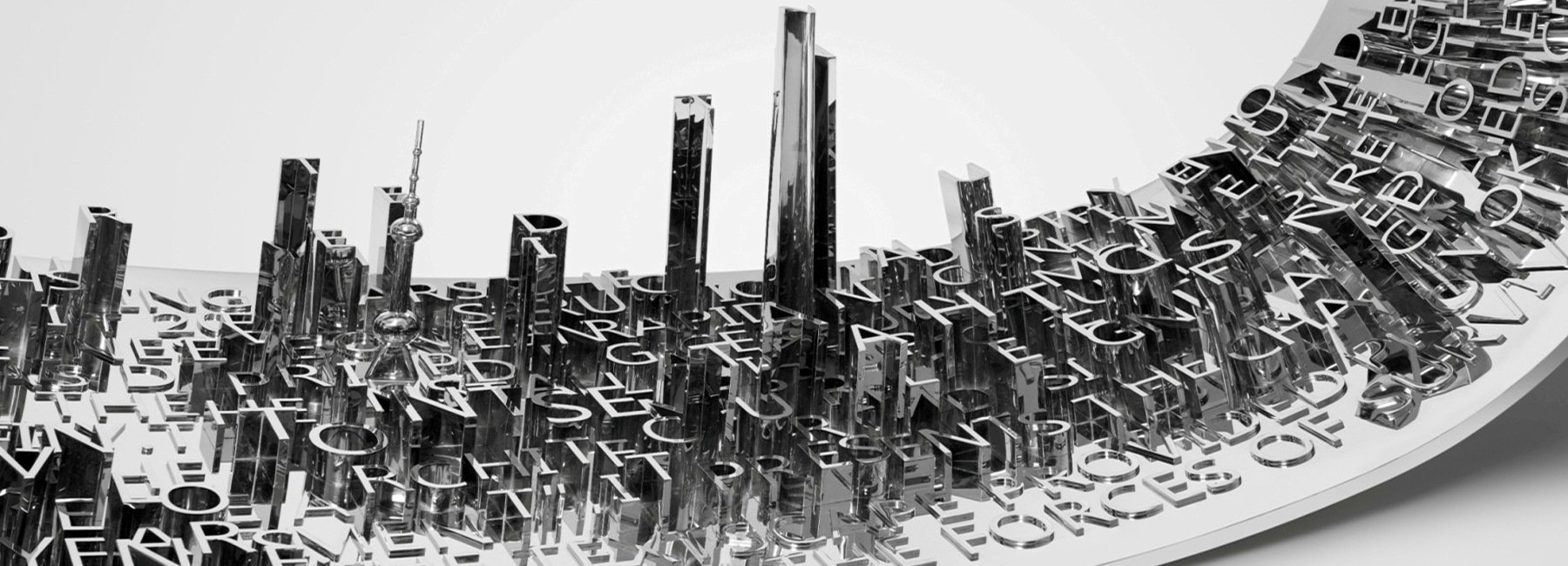

Of course, Tory’s work is not an abecedary. In Books Two and Three, it develops into a full-blown treatise on letterforms whose meaning and appearance are explained allegorically and driven by the compass, rule and geometry expressed within a 10x10x10 cell cube. It would overstate the case to call it “typographic design”. As drawn, Tory’s diagrams would serve poorly for cutting and forming punches or matrices (although it has been done). Nevertheless, his geometric approach foreshadows the grids and algorithms of Wim Crouwel’s New Alphabet (1967), Timothy Epps and Christopher Evans’ Alphabet (1970) and Ji Lee’s Univers Revolved: A Three-Dimensional Alphabet (2004).

OAHK pages showing the grid approach. 1529 original from the Bibliothèque national de France; 1927 translation & facsimile © 1927 The Grolier Club; 1998 facsimile © Bibliothéque de l’Image. Photos of the latter two books: Books On Books Collection.

Clockwise from top left: Crouwel, Lee and Epps/Evans. Photos of the works: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © Wim Crouwel. © Ji Lee. © Timothy Epps and Christopher Evans.

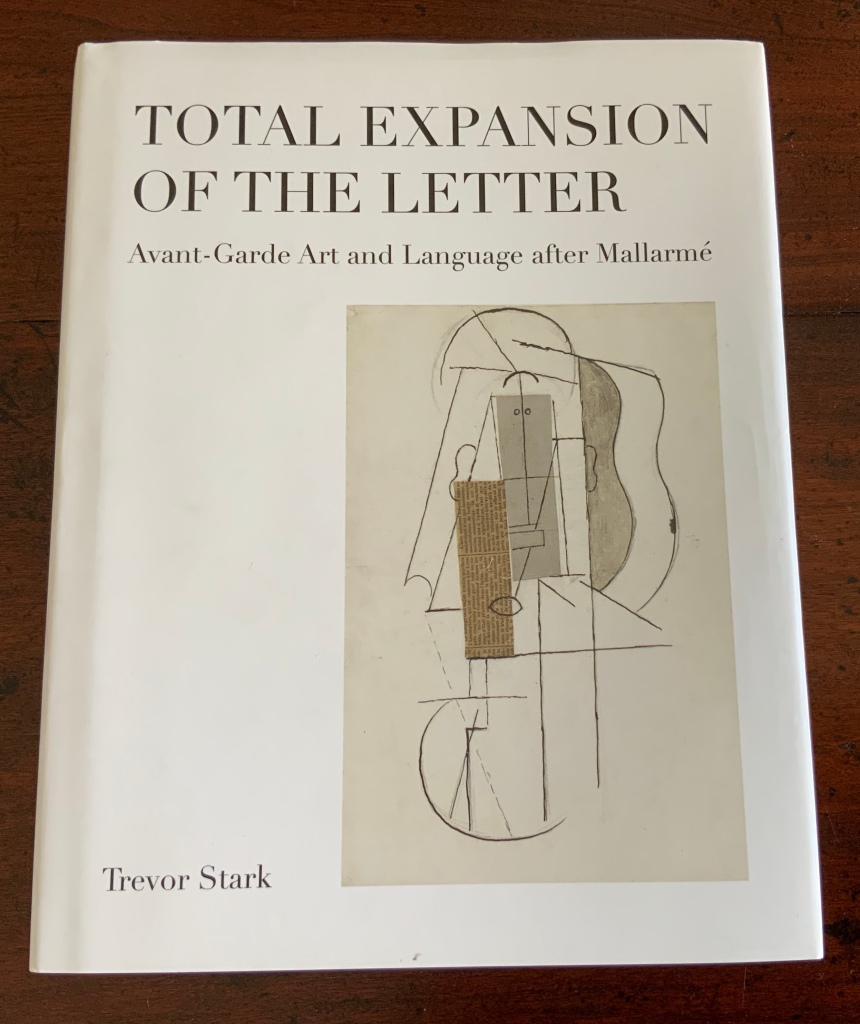

Before the age of computers and algorithms, though, the artist and designer Bruce Rogers did bring typographic design to bear on Champ Fleury. The Grolier Club sponsored the printing of George B. Ives’ English translation. Rogers’ design “translates” Champ Fleury just as much as Ives does, perhaps more so. The Grolier Club edition is one of only ten books to be set completely in the Centaur typeface designed by Rogers.

Bruce Roger’s typeface Centaur, as presented in Paul McNeil’s The Visual History of Type (2017), pp. 196-97. Photo: Books On Books Collection. © Paul McNeil.

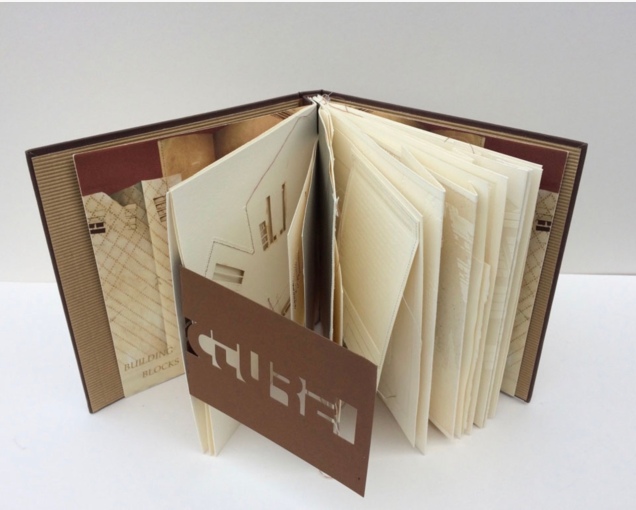

Of course, the translation entails a complete resetting of the text, and Centaur naturally delivers crisper letters. Also, in redesigning with Centaur, Rogers alters the original’s layout and, therefore, the reader’s experience of it. Notice in the OAHK pages above and in the three double-page spreads below how Rogers changes Tory’s flow or jumpiness to something fixed or stately. Attention to the page and its layout offers book artists as well as book designers yet another creative avenue. For proof of that, compare the Collection’s entries for Angel, Baskin and de Cumptich.

Rogers’ change in layout (© 1927 The Grolier Club) shown between 1529 original (from the Bibliothèque national de France) and 1998 facsimile (© Bibliothéque de l’Image). Photos of the latter two books: Books On Books Collection.

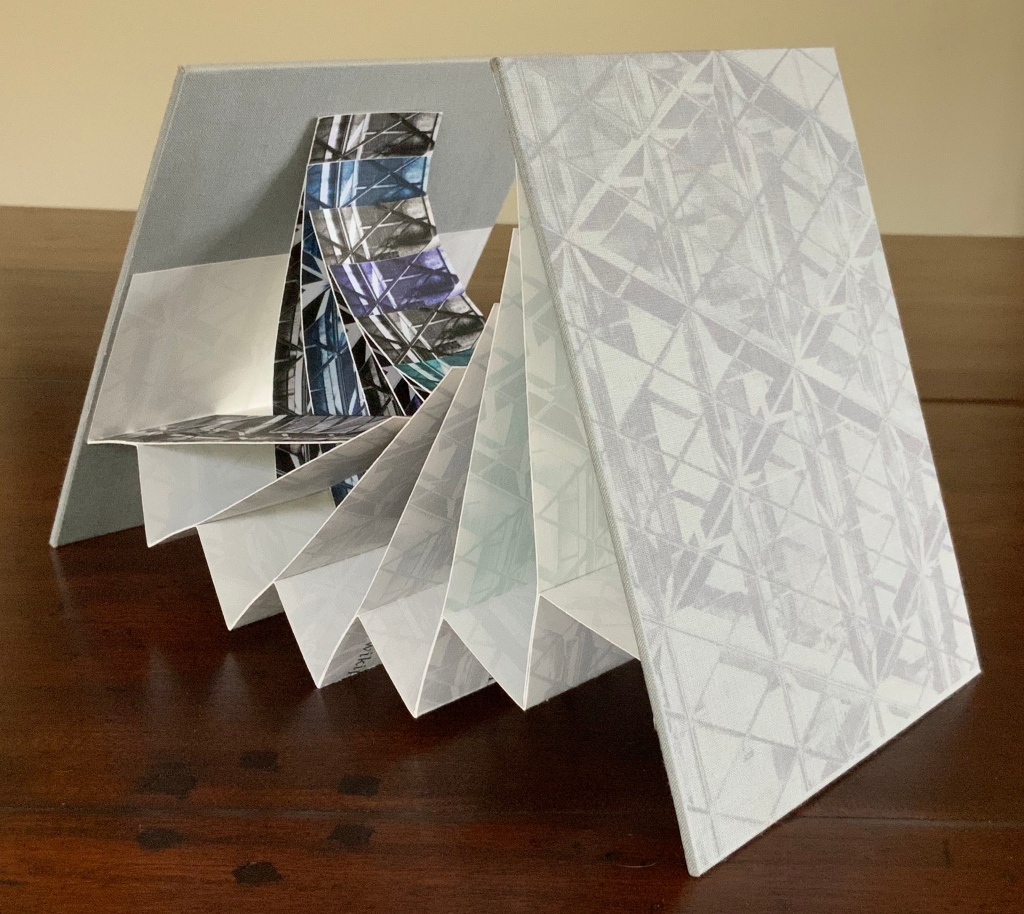

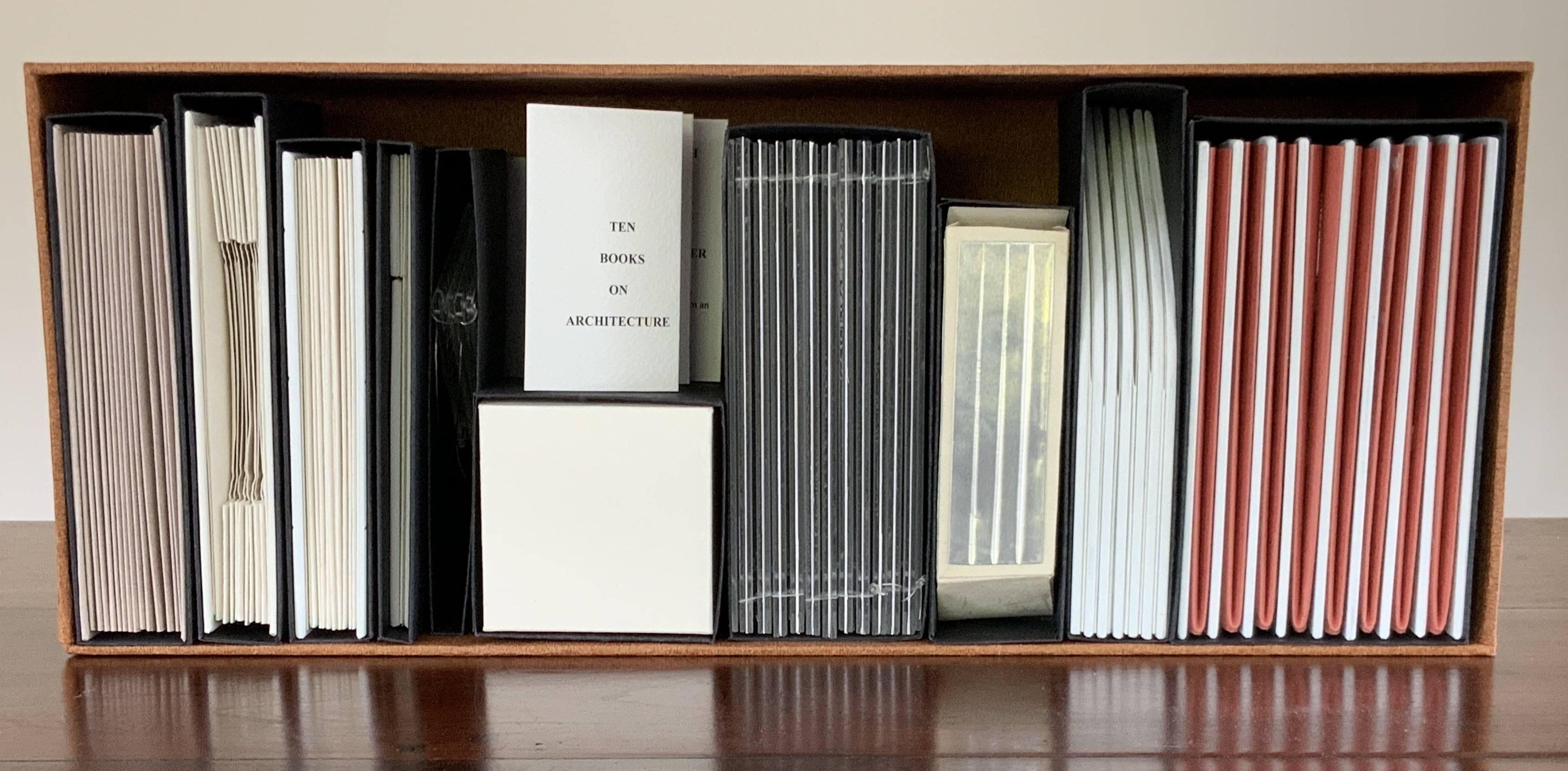

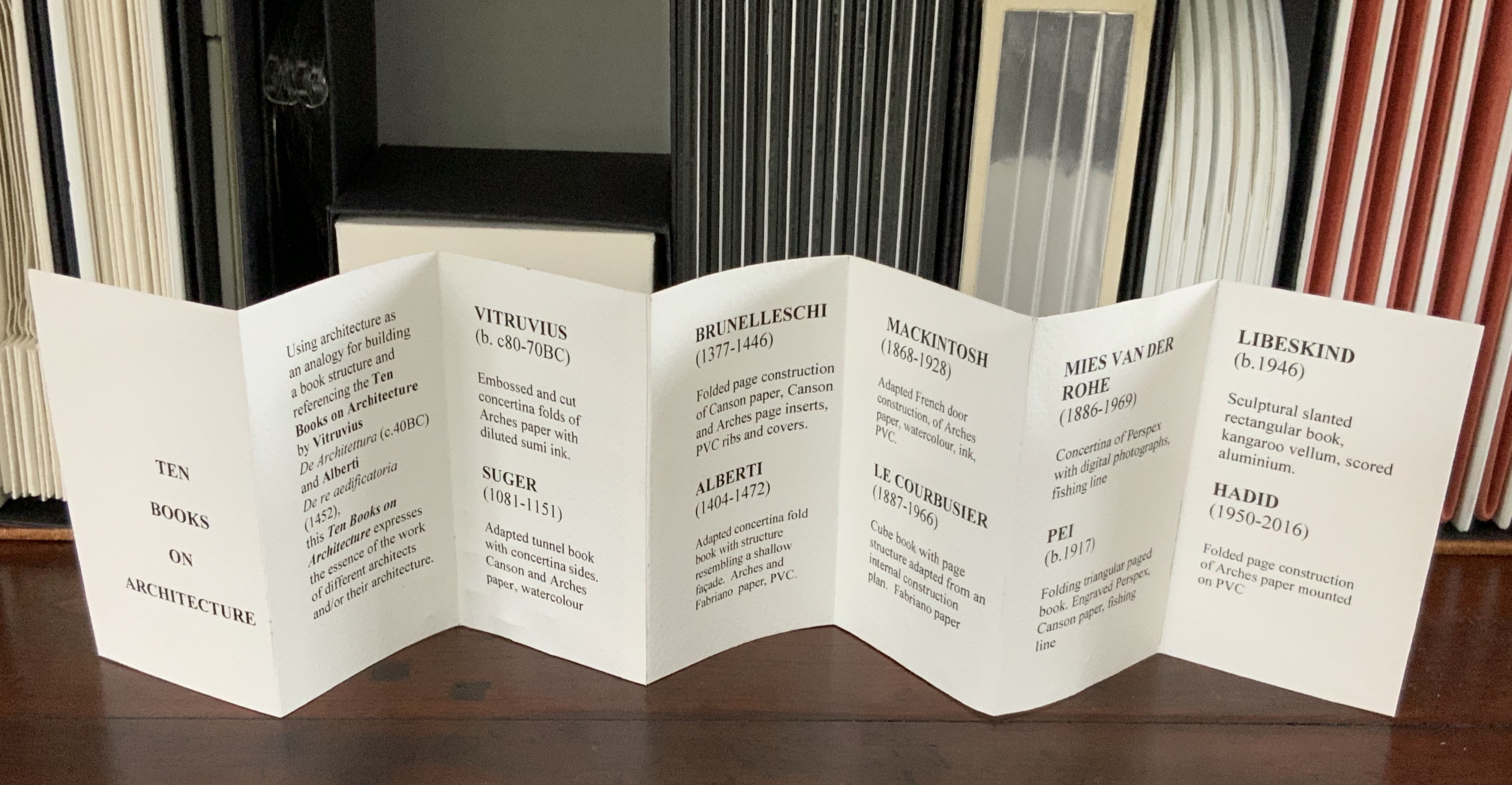

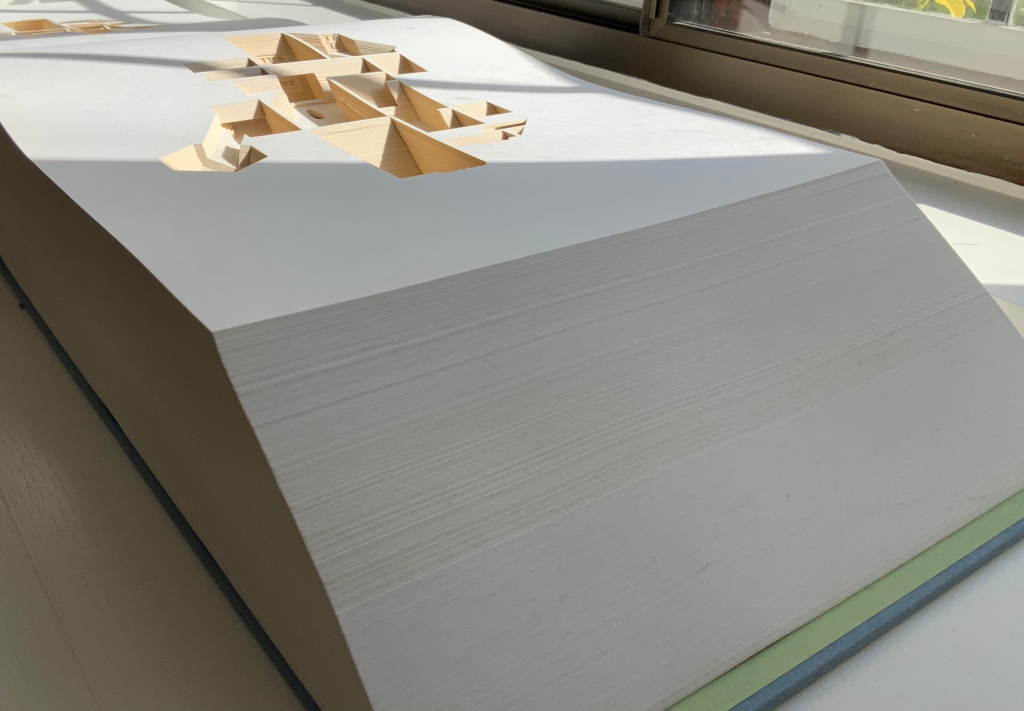

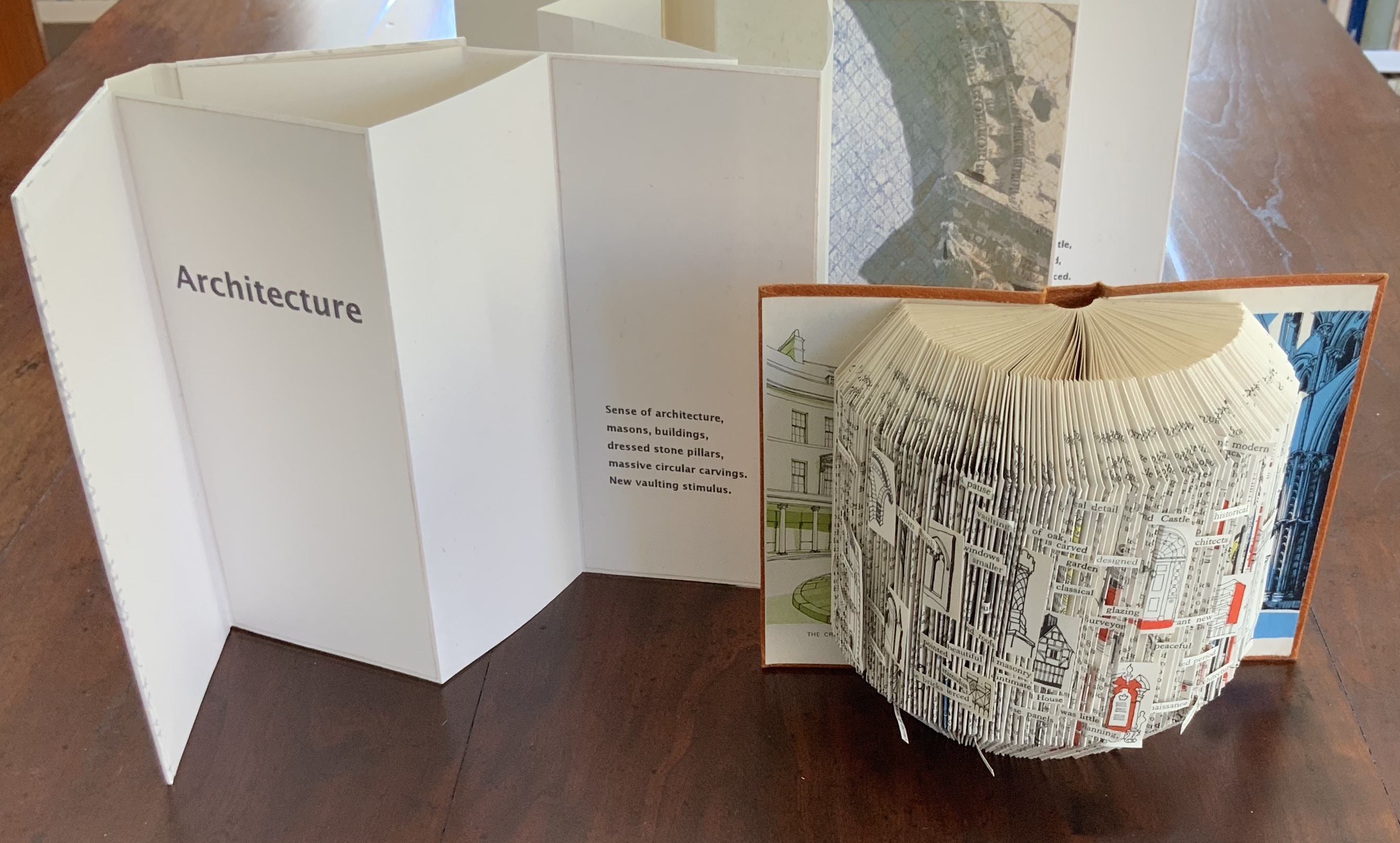

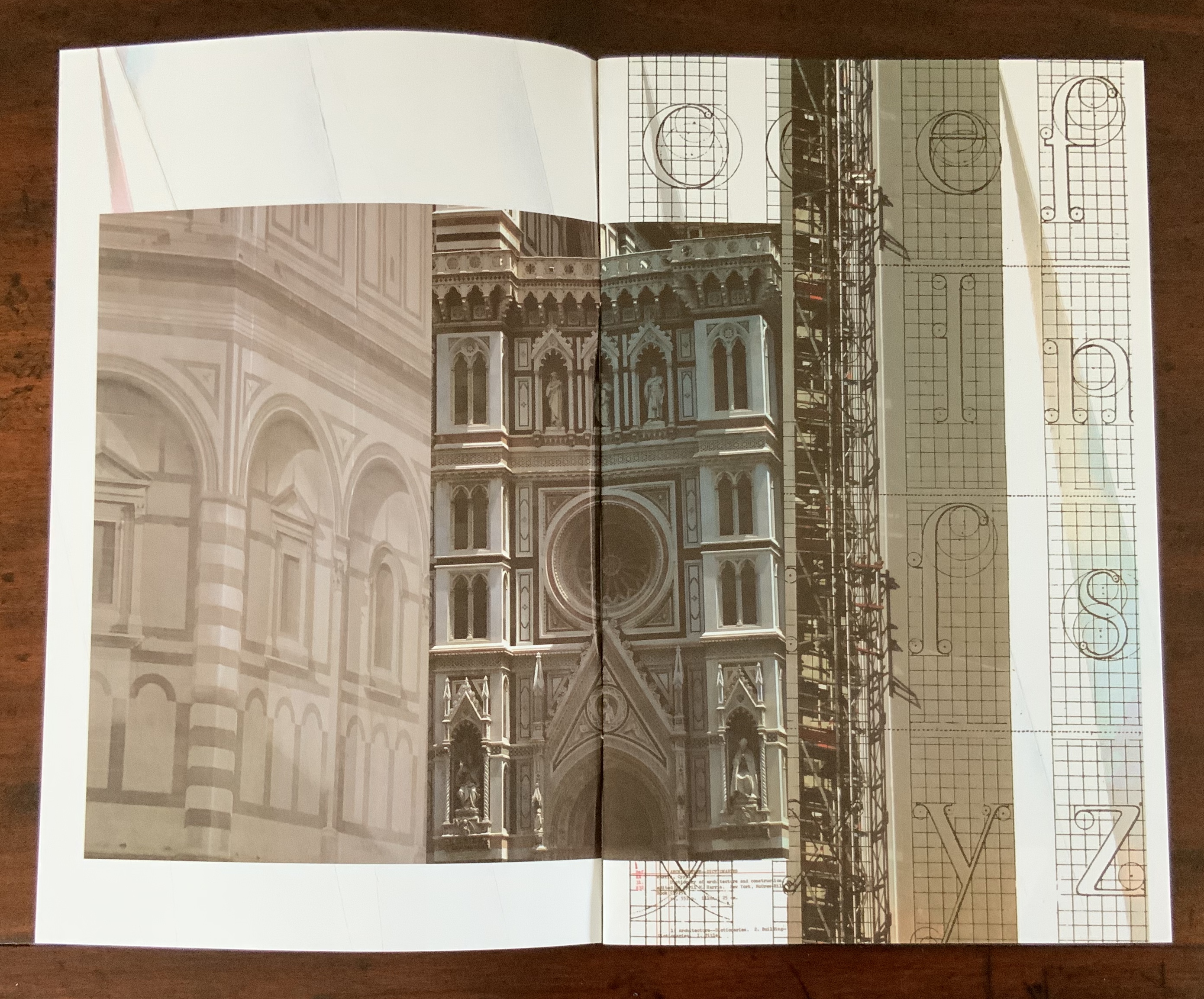

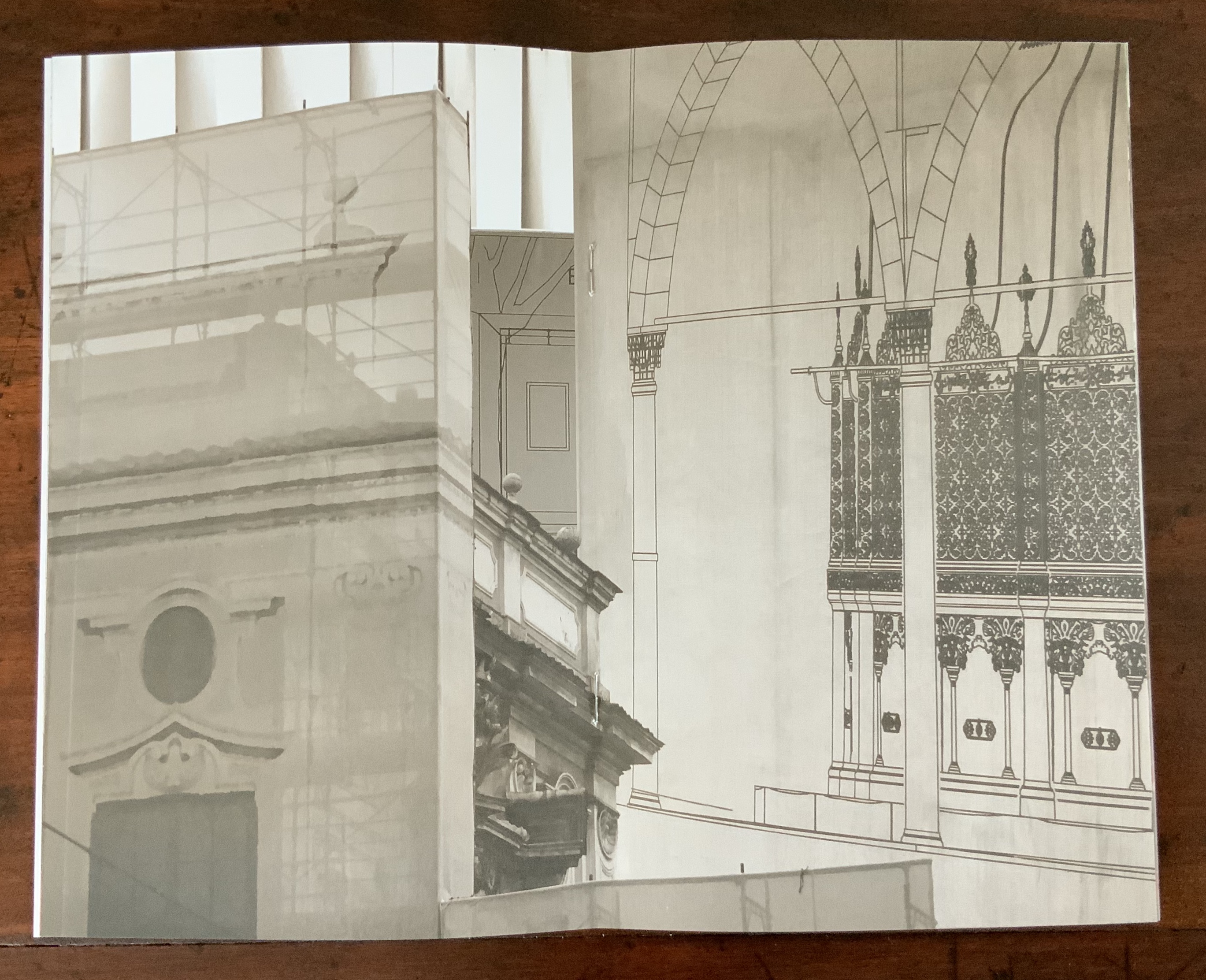

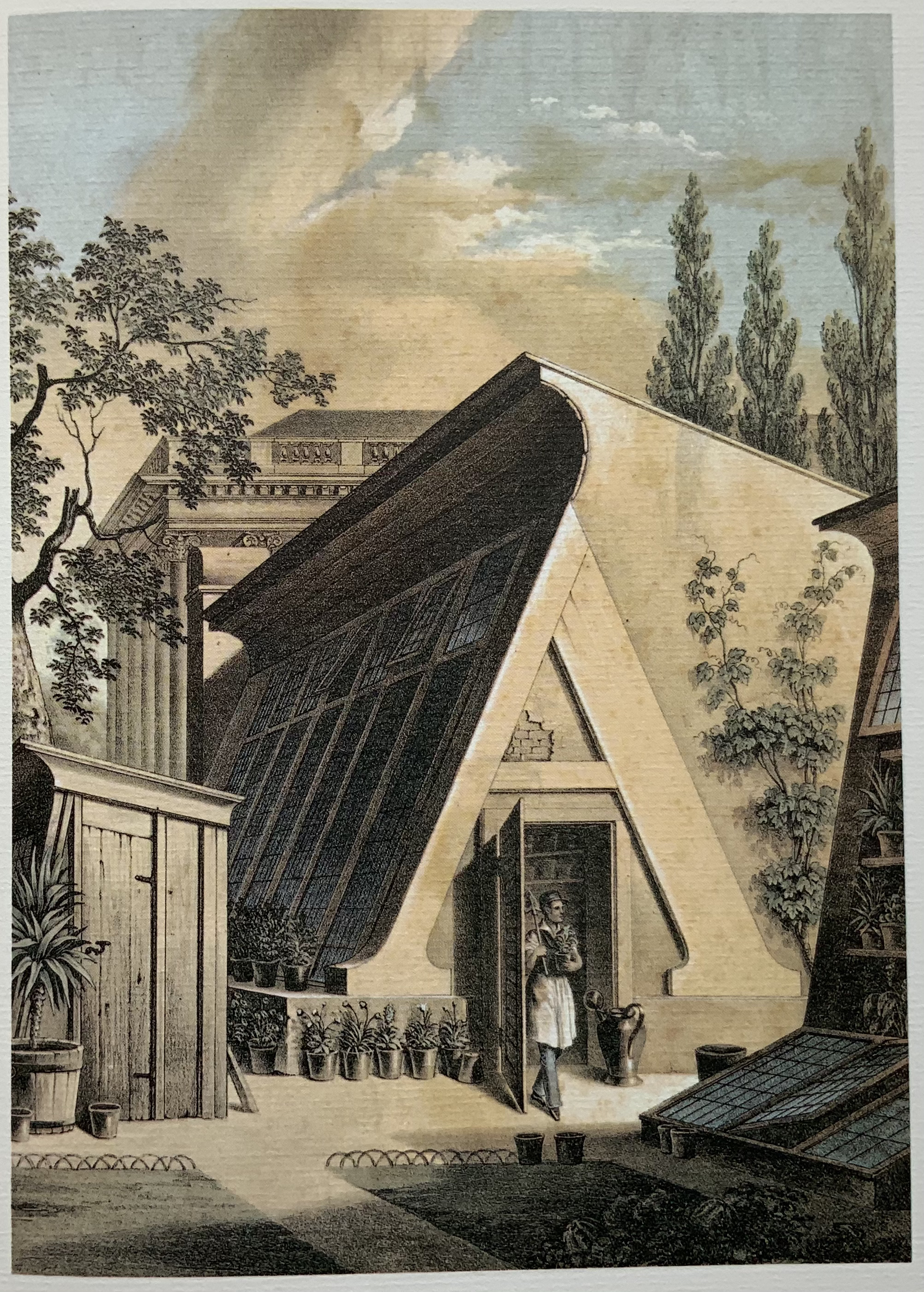

Architecture is another of Tory’s well-developed analogies and explanations of the ancients’ thinking behind the letterforms. In his drawings below, he aligns the letters AHKOIS with the parts of a building and letters IL with floor plans. He connects the circularity of the Coliseum’s exterior and the ovalness of its arena with the proper shape of the letter O. In the Collection, the analogy reappears fantastically in Johann David Steingruber’s Architectural Alphabet (1773/1972), Antonio Basoli’s Alfabeto Pittorico (1839/1998) Antonio and Giovanni Battista de Pian’s efforts in 1839 and 1842.

Architectural analogies: 1529 original in the Bibliothèque national de France; 1927 translation & facsimile © 1927 The Grolier Club; 1998 facsimile © Bibliothéque de l’Image.

Left to right: Steingruber, Basoli, Antonio de Pian and Giovanni Battista de Pian. Photos of the books: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the books: © Ravensburger Buchverlag, Joseph Kiermeier-Debre and Fritz Franssens Vogel.

The architectural analogy provides Tory with his segue from plane to solid geometry in aligning the shapes of letters with human anatomy and virtues. His three-dimensional analysis of letterforms also finds contemporary analogues in two of Pieter Brattinga’s Kwadraat Blad series: Crouwel’s, mentioned above, and Anthon Beeke’s Alphabet (1970). Tory’s three-dimensional letterforms foreshadow Crouwel’s investigation of units based on the assembly of organic cells and his later musings on a laser-generated four-dimensional typography (Elliman, 62). And it is hard to evoke anything more humanoid and three-dimensional — albeit far less analytical or prudish — than Beeke’s alphabet formed with naked female models. (Tory comments that in a correctly drawn A, the crossbar will virtuously cover the genitals of Vitruvian man inscribed in the 10×10 grid. Modesty seems to extend to H as well but not so much to O and K.)

Following Beeke’s design, the photographer directed the models into position then took the shot from above. Photos of the work: Books On Books Collection. Images in individual folios: ©Geert Kooiman. Copyright in the work: ©Anthon Beeke Archive Foundation.

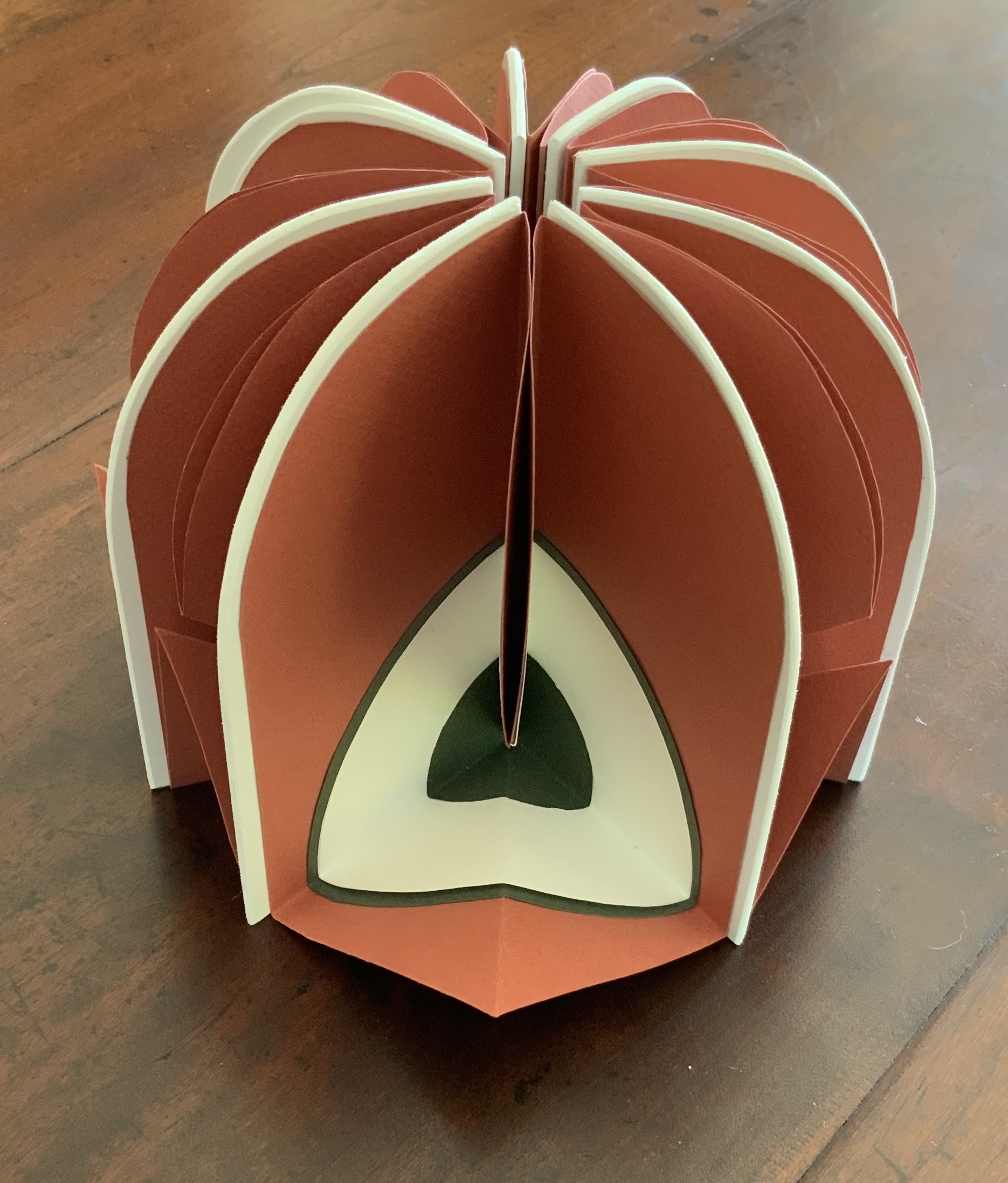

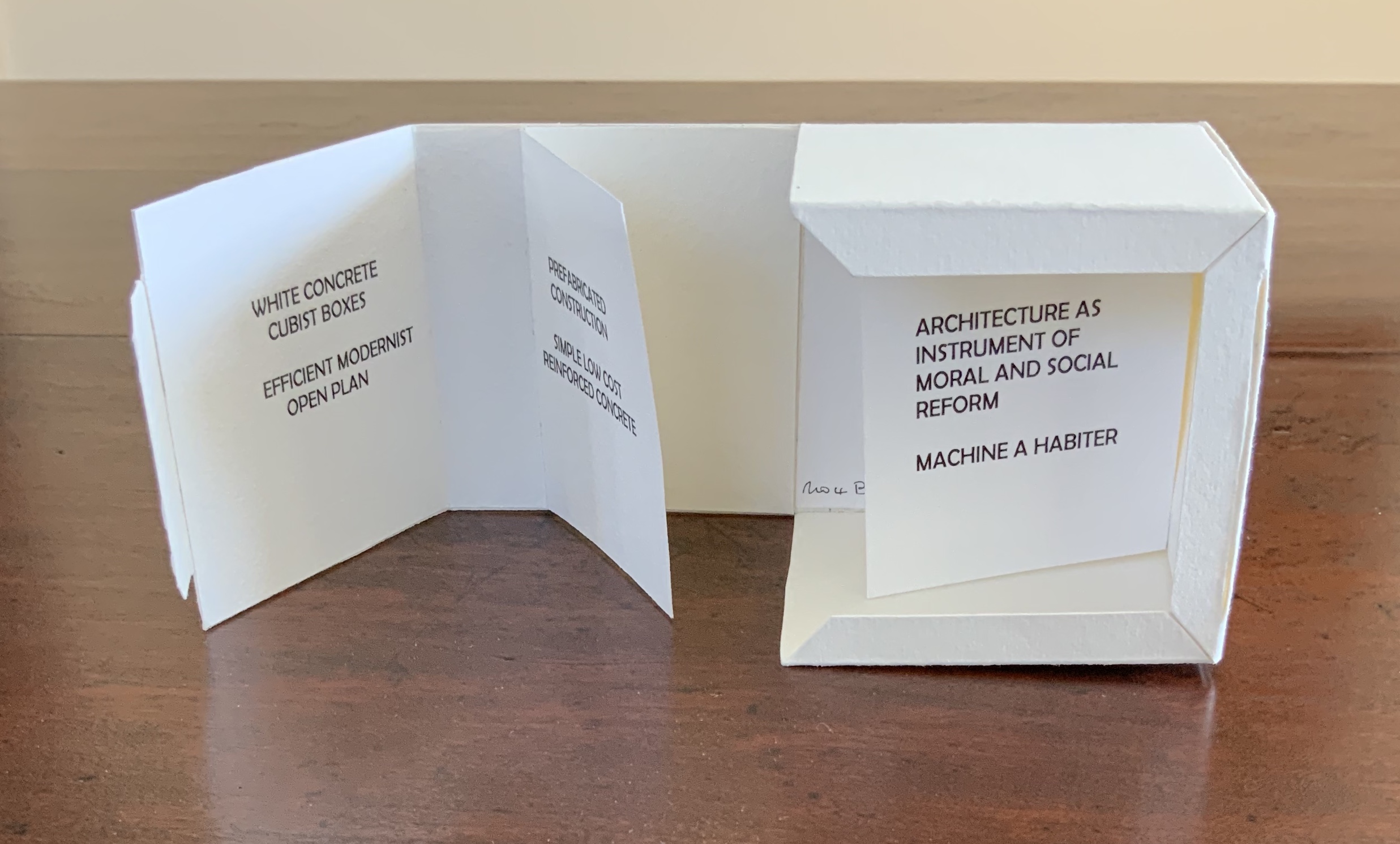

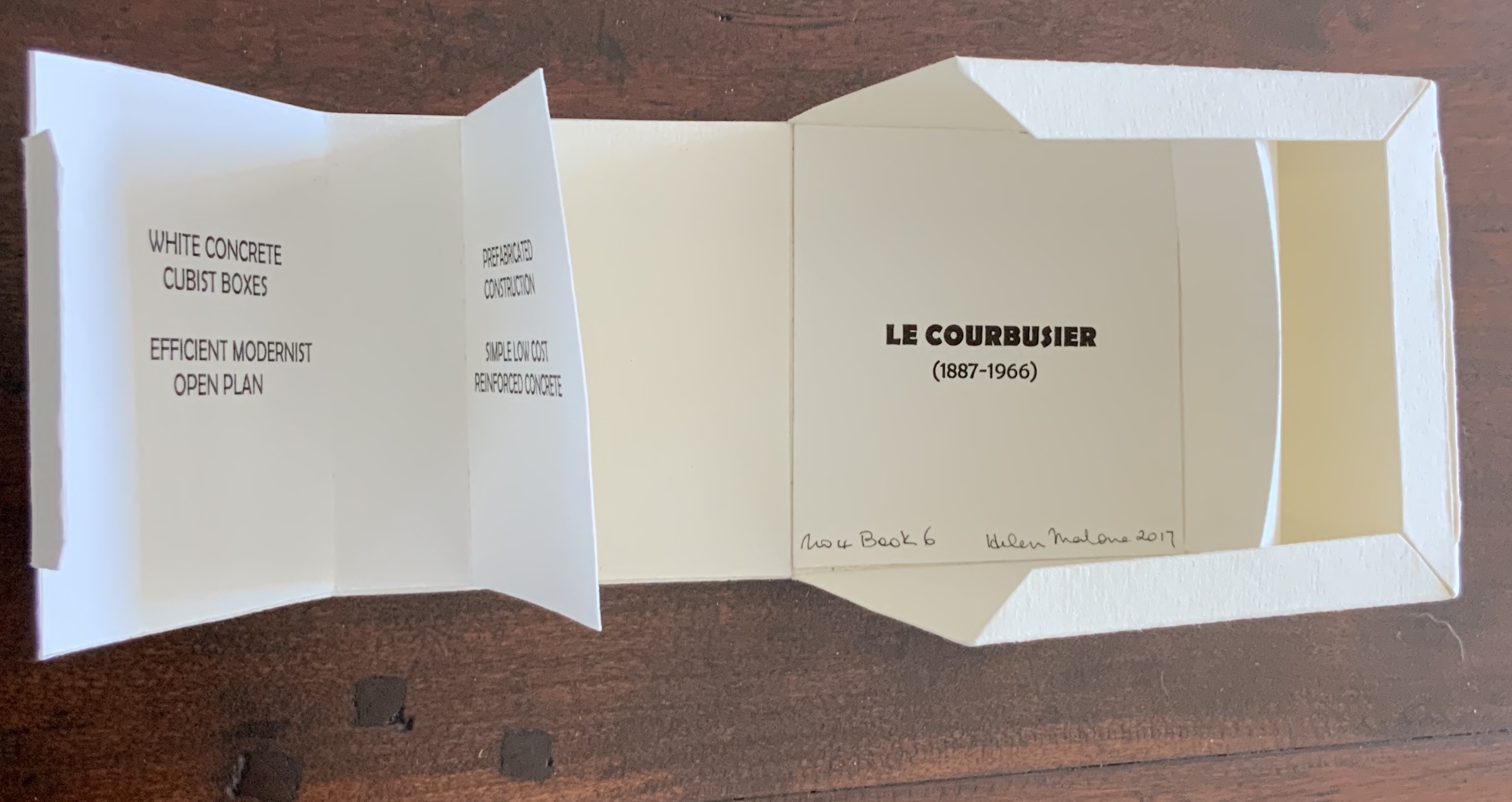

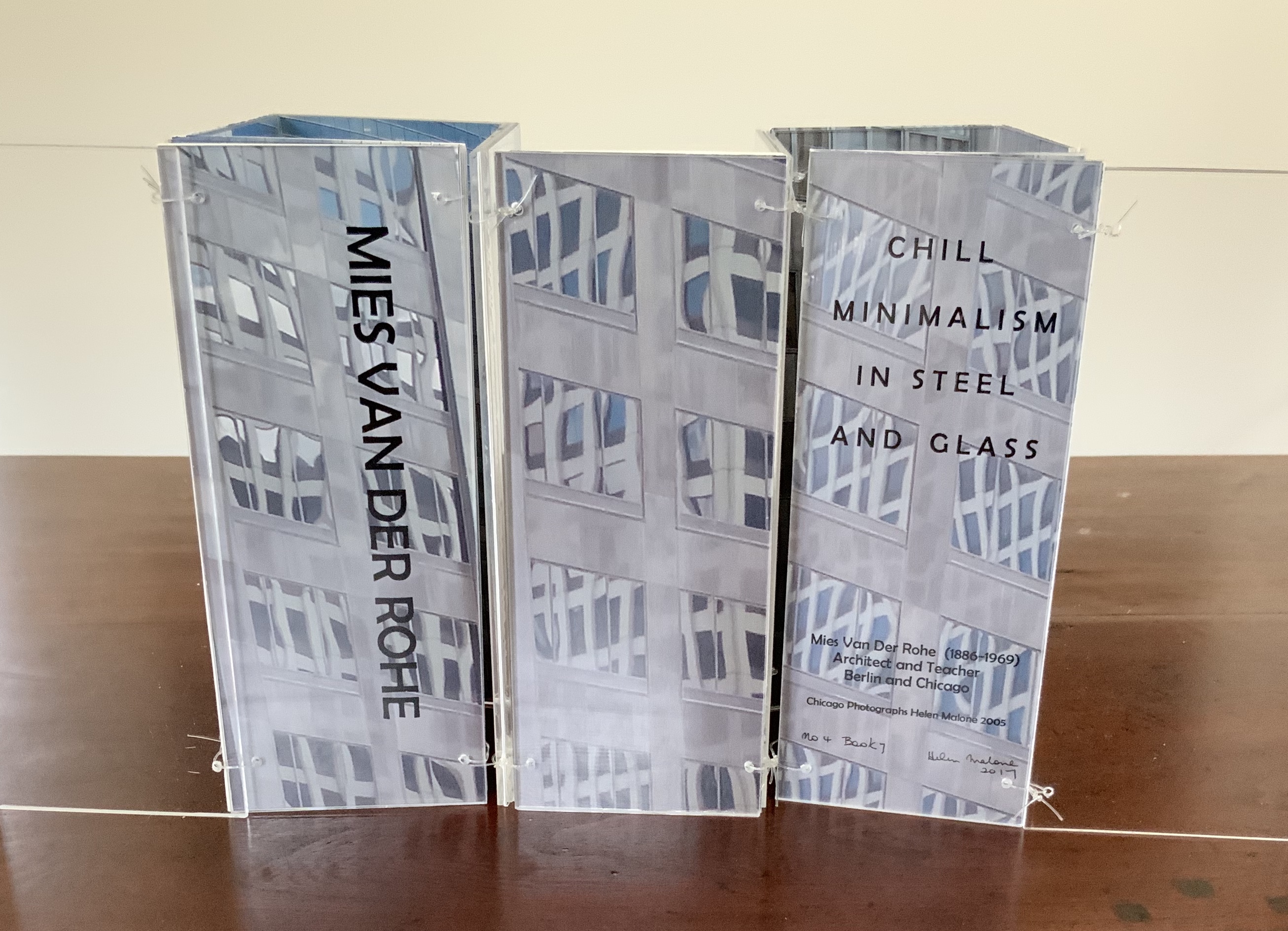

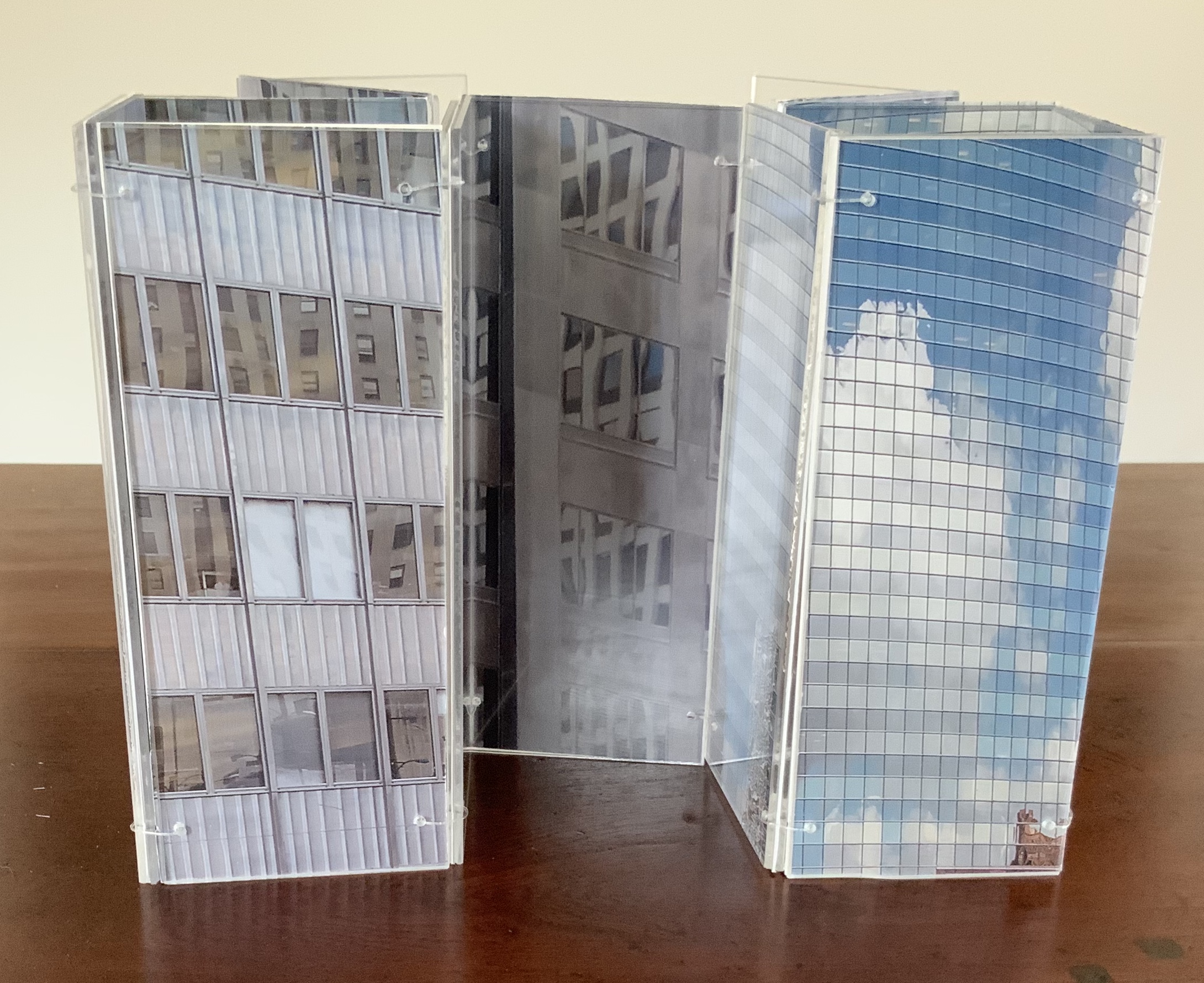

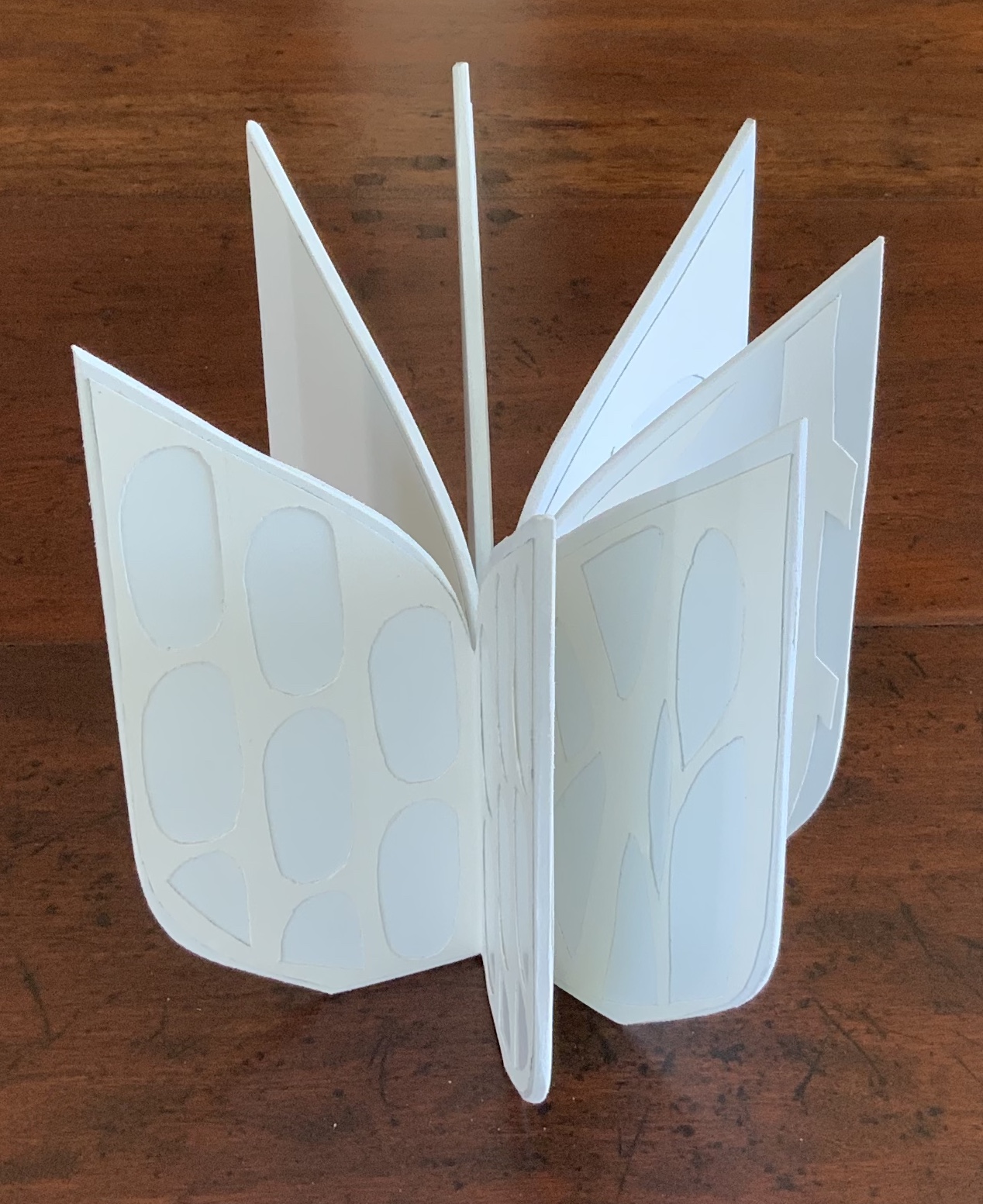

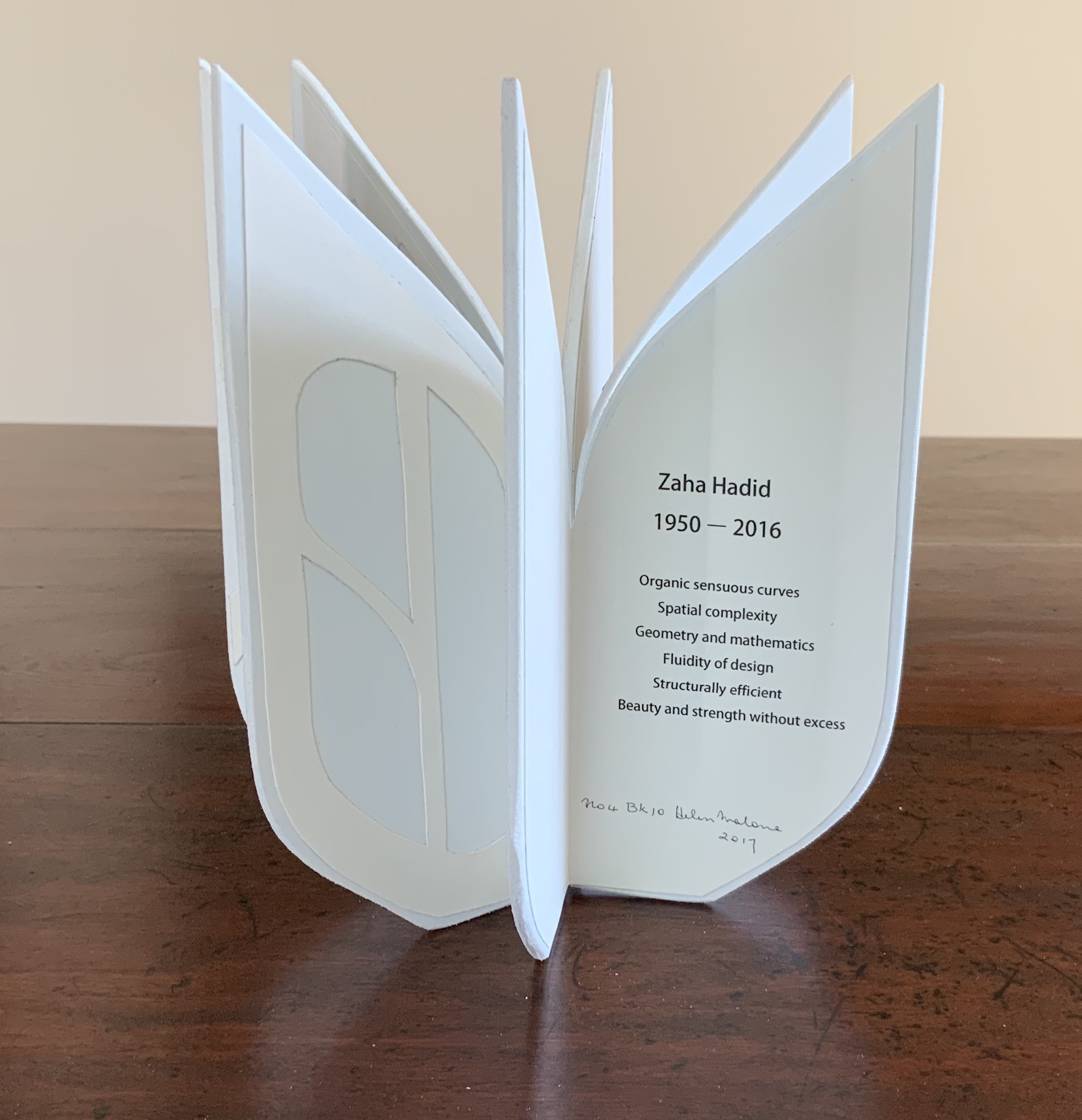

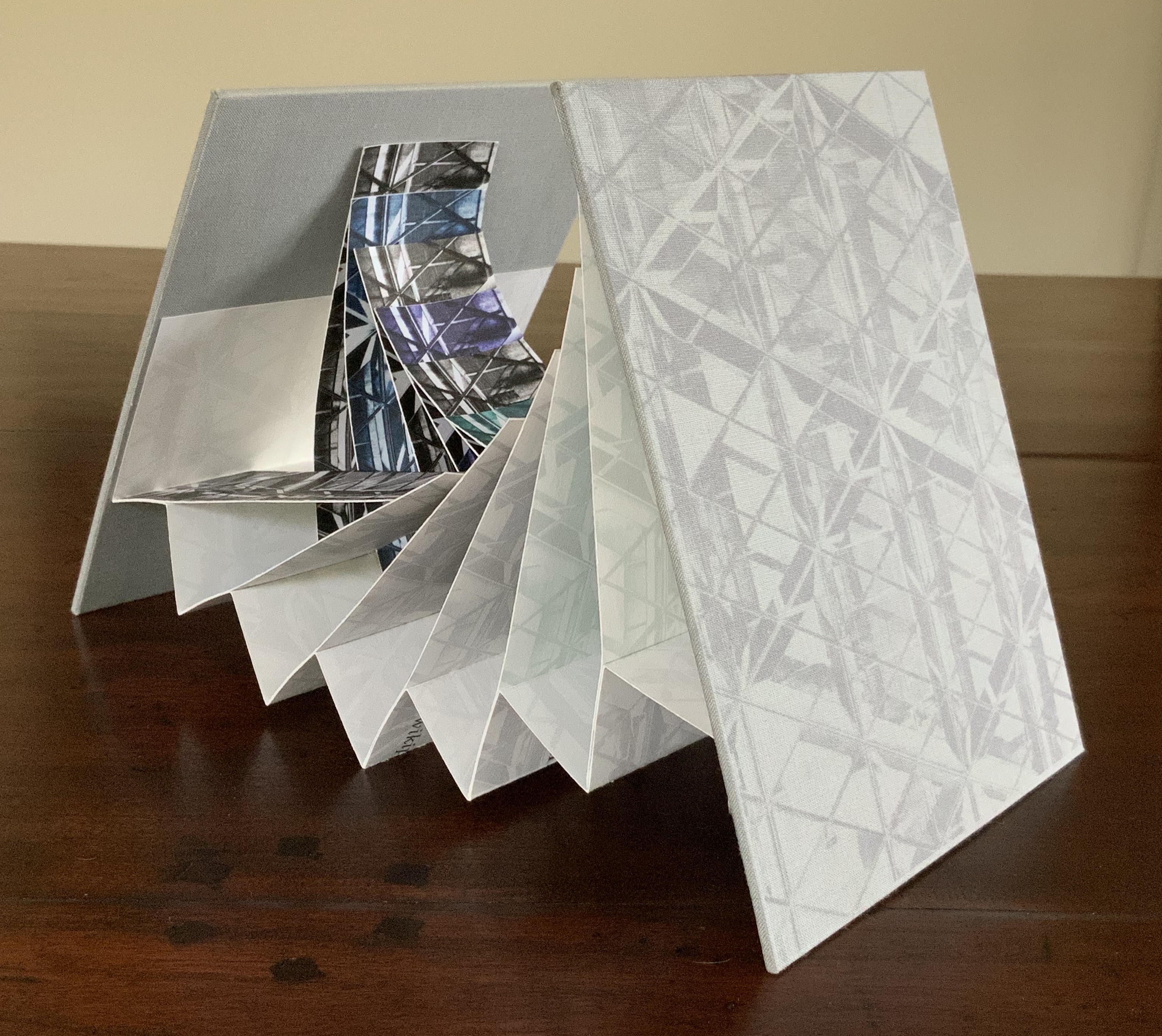

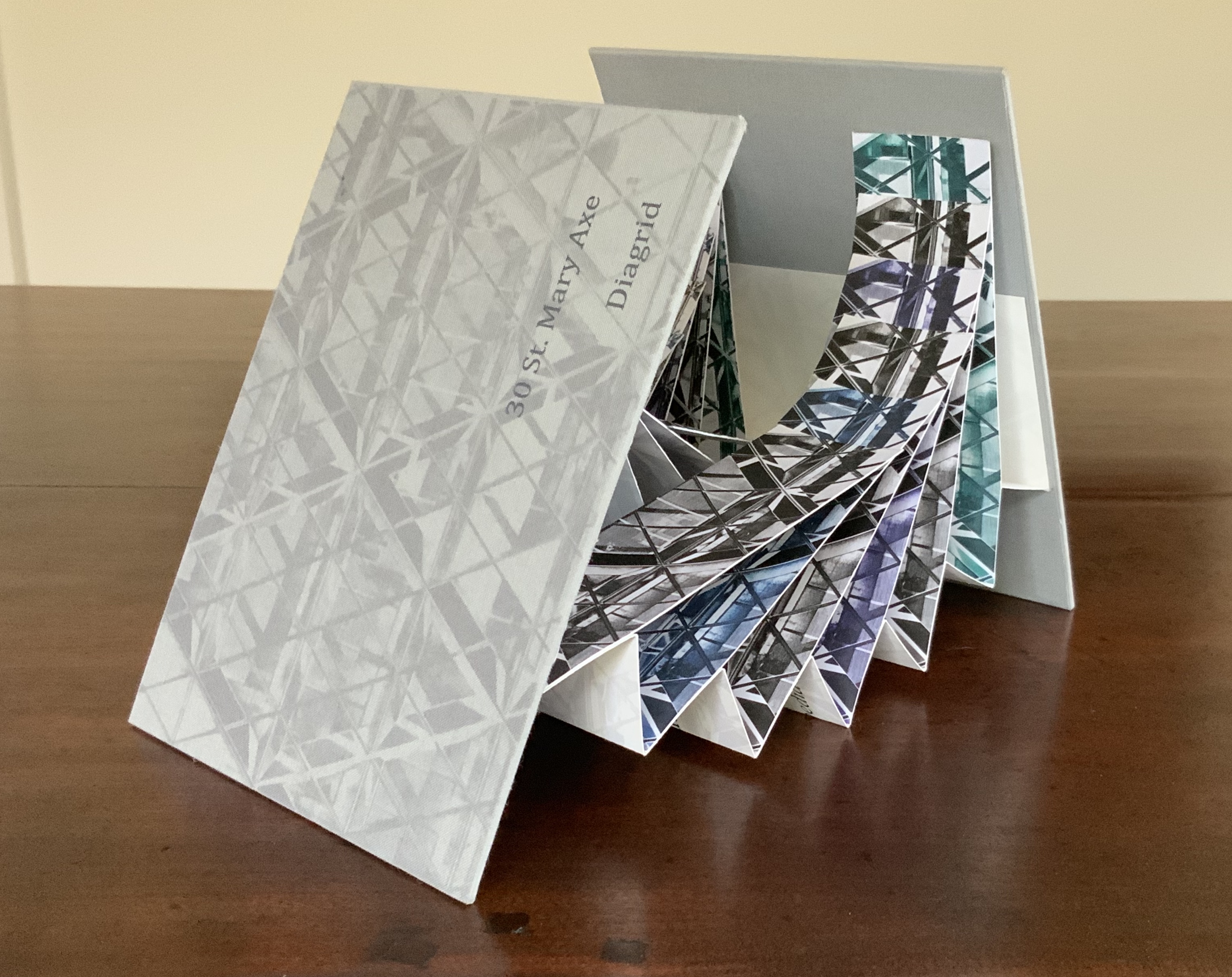

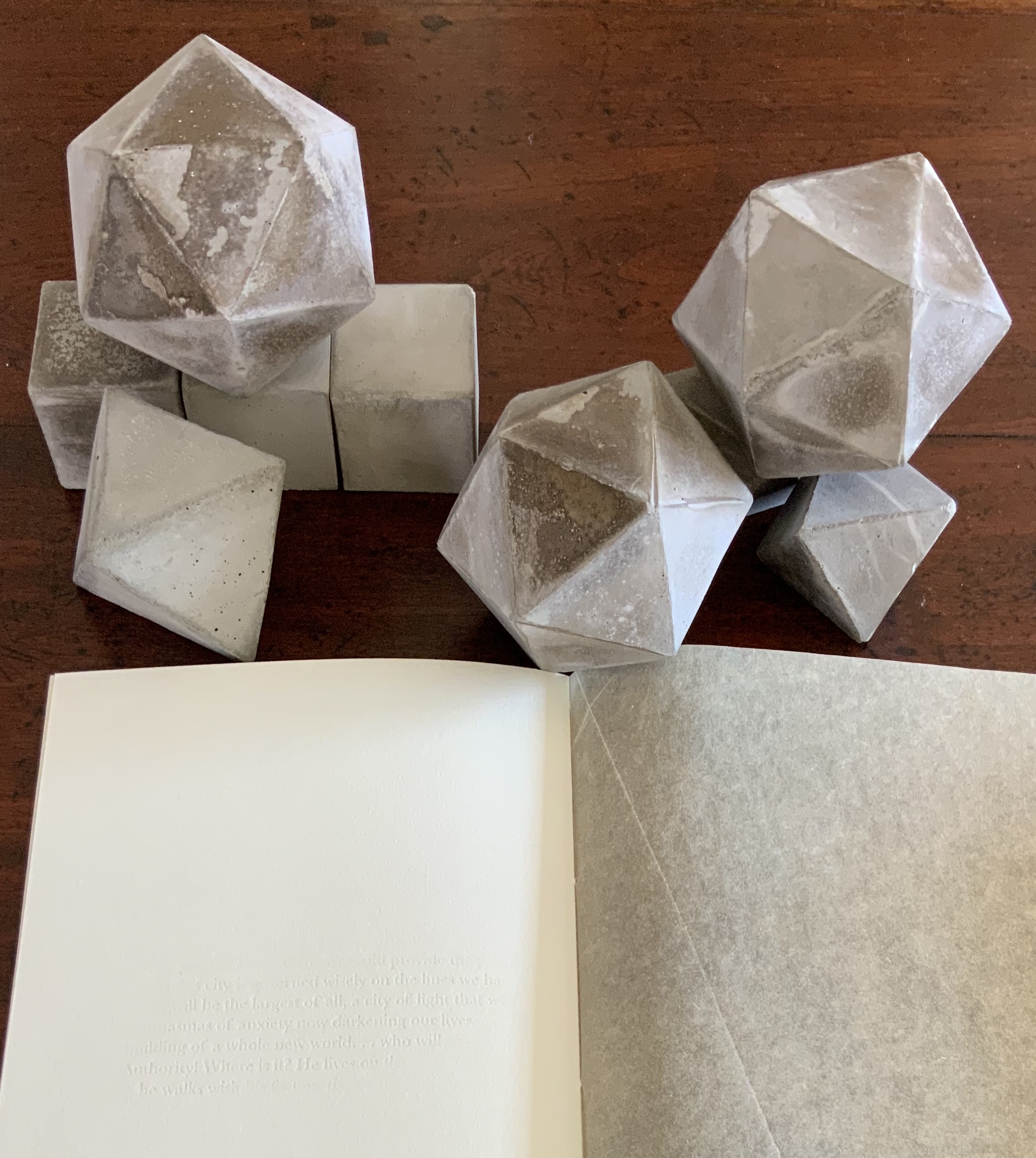

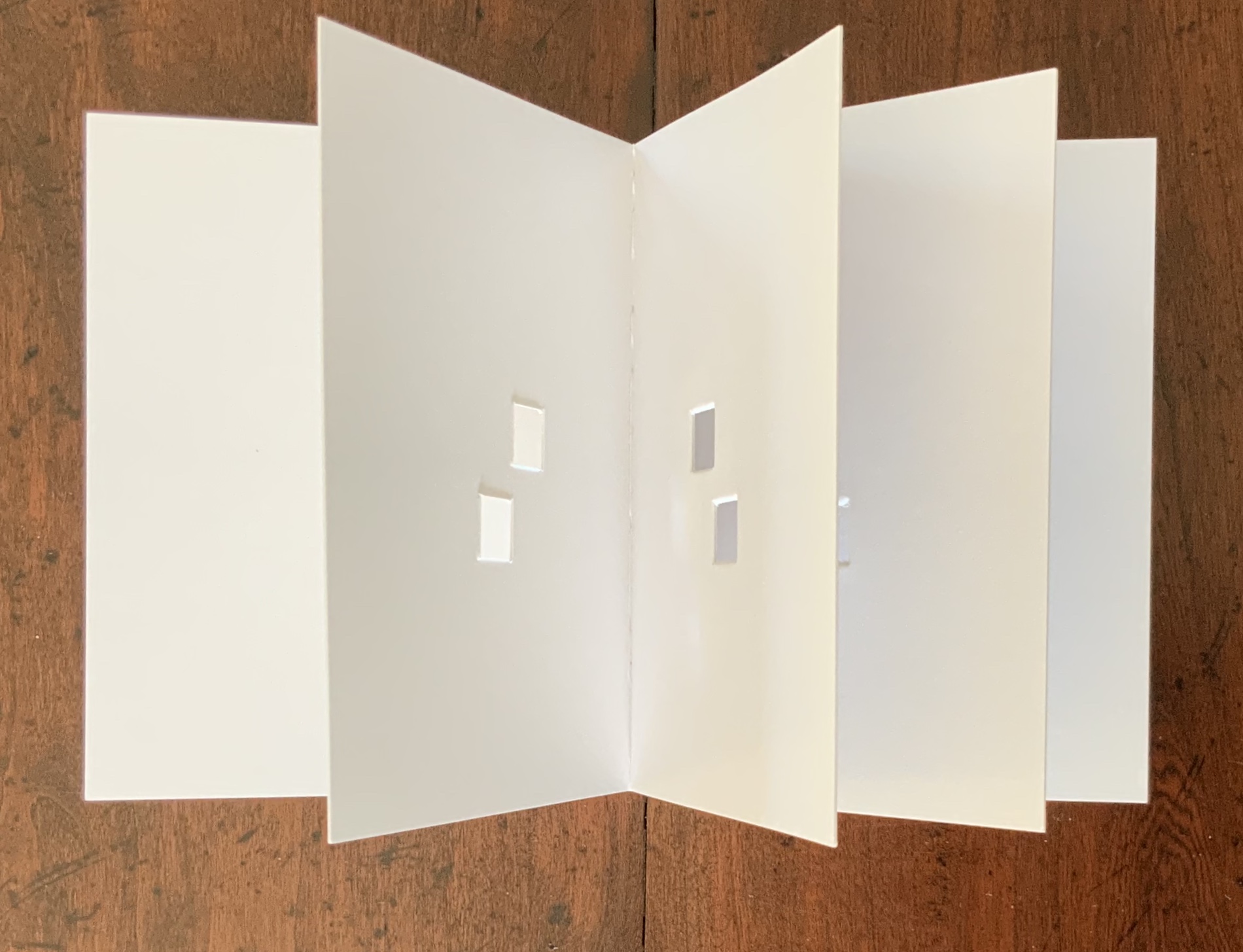

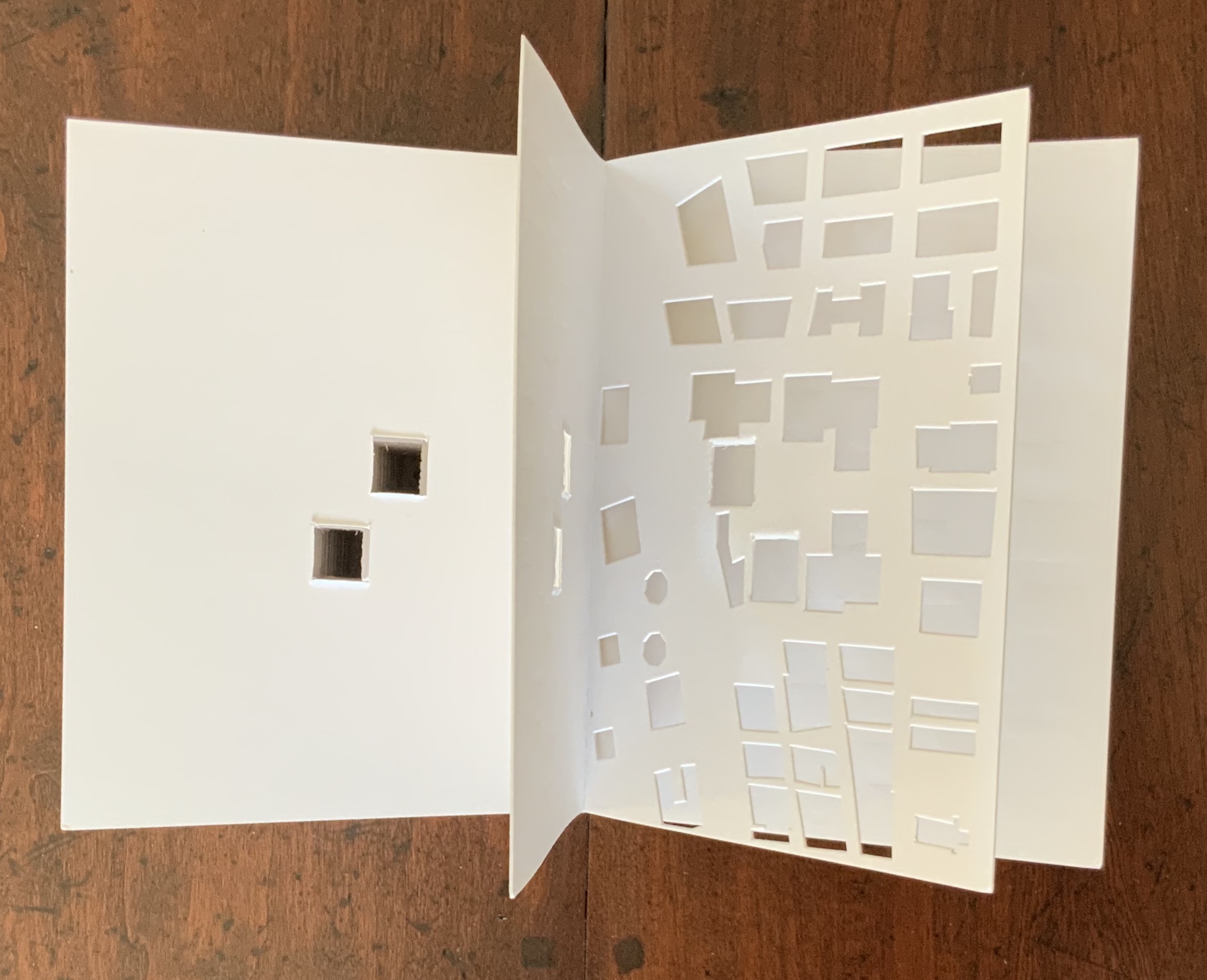

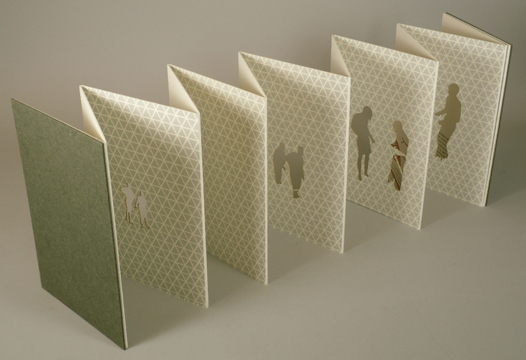

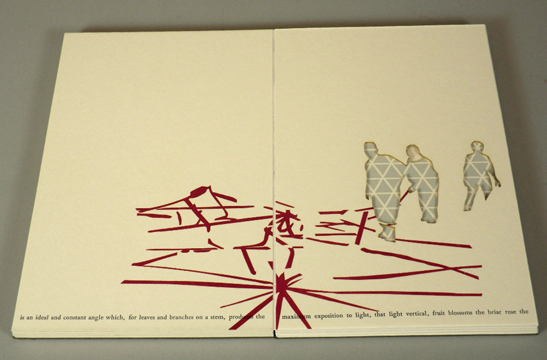

Other less humanoid but still three-dimensional analogues to Tory’s letters appears in various sculptural bookworks by Marion Bataille, Helen Hiebert, Takenobu Igarashi, Ron King, Scott McCarney, Claire Van Vliet and the 25th anniversary compendium from the Movable Books Society.

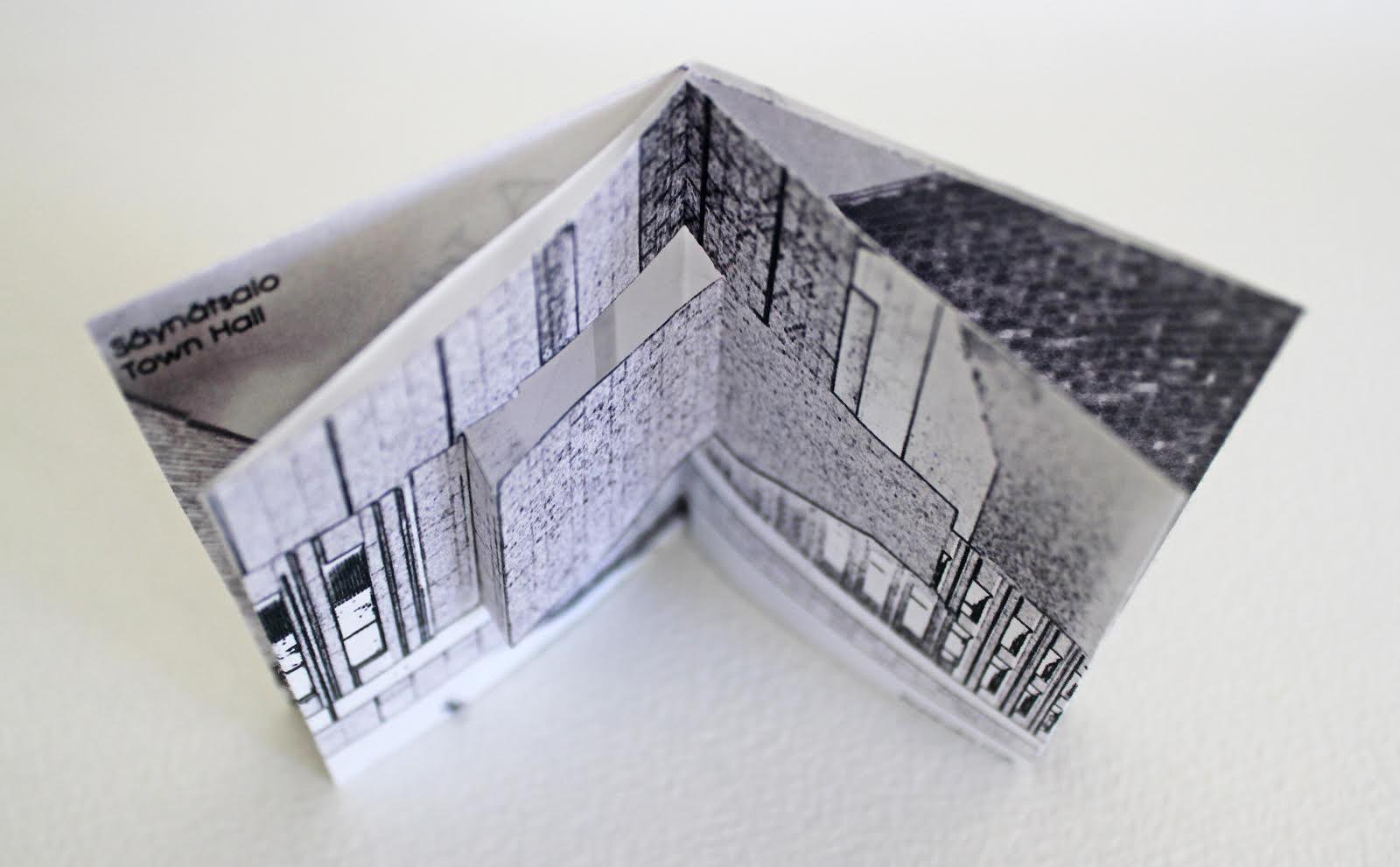

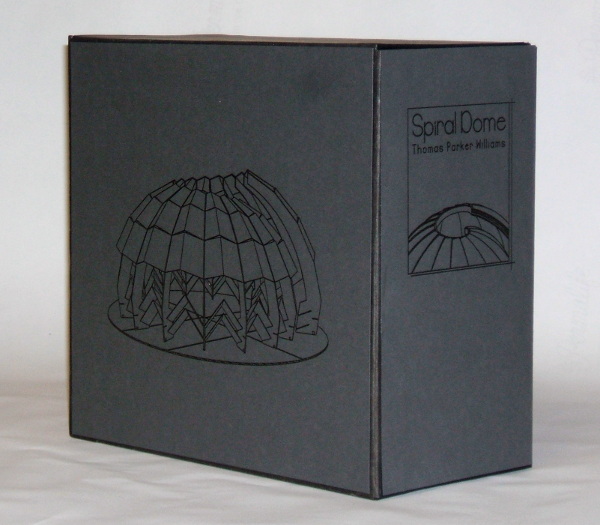

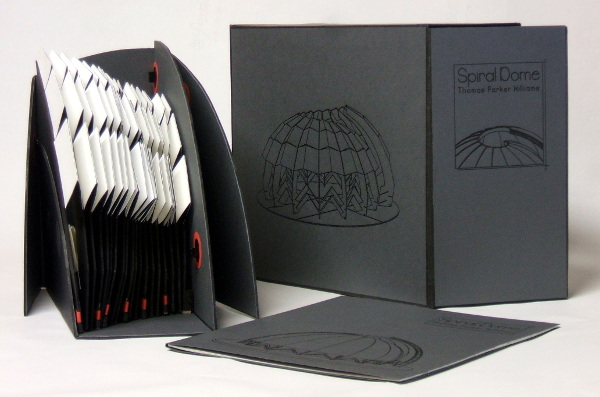

Top row from left to right: A from Bataille’s ABC3D; EFGH from Helen Hiebert Alpha Beta; b from Ron King’s Alphabeta Concertina Miniscule.

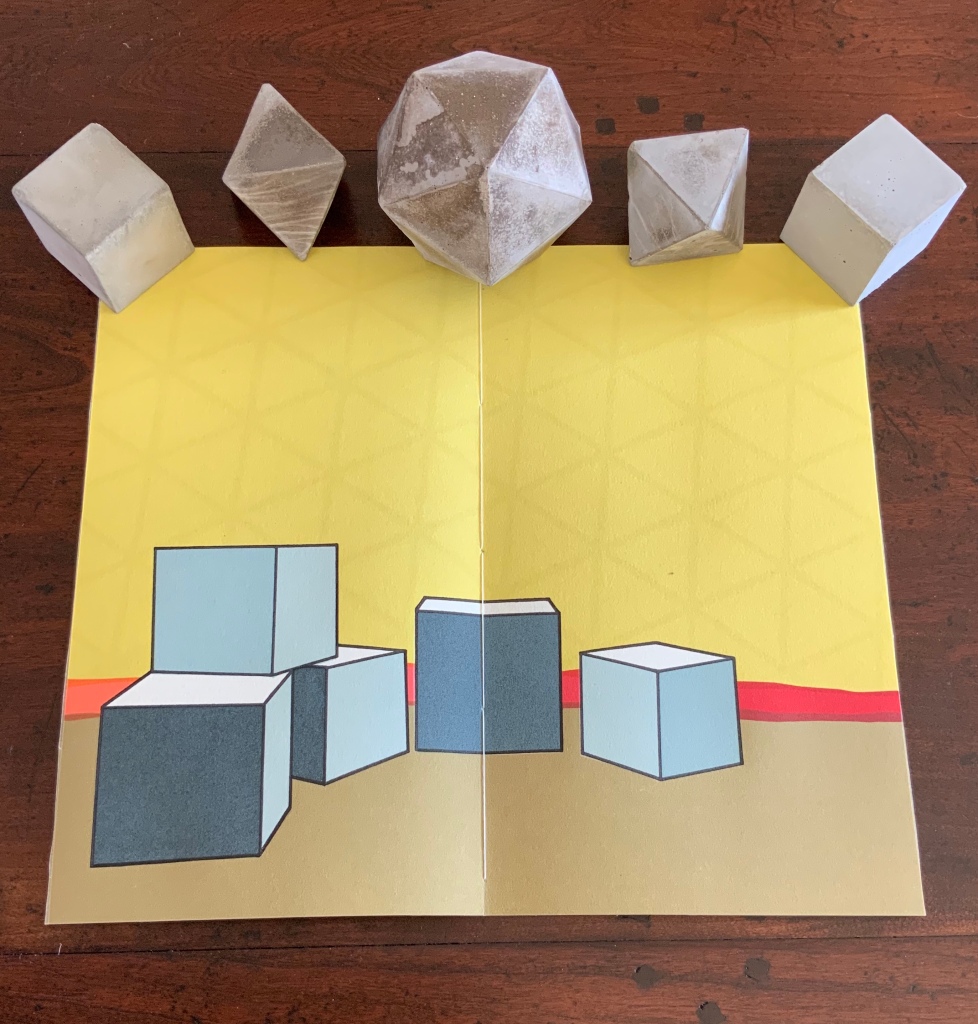

Bottom row: ABC… from Scott McCarney’s Alphabook 3; AB from Claire Van Vliet’s Tumbling Blocks for Pris and Bruce; box opening from The Movable Book Society’s 25th Anniversary.

Photos of the works: Books on Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © Marion Bataille; © Helen Hiebert; © Ron King; © Scott McCarney; © Claire Van Vliet; © The Movable Book Society.

The calligraphic impulse that underlies Champ Fleury‘s typographic representations shows itself clearest in the woodcuts for the Cadeaulx alphabet in the appendix. The Books On Books Collection has its share of calligraphic abecedaries such as Marie Angel’s An Animated Alphabet (1996) and Andrew Zega and Bernd Dam’s An Architectural Alphabet (2008) as well as more purely calligraphic alphabets such as Islam Aly’s, mentioned above, and Suzanne Moore’s A Blind Alphabet (1986) .

From the appendix to Champ Fleury. Photo of the book: Books On Books Collection. 1998 facsimile © Bibliothéque de l’Image.

Clockwise from the left: A from Angel’s An Animated Alphabet; U from Zega and Dam’s An Architectural Alphabet; BC from Moore’s A Blind Alphabet. Photos of the works: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © Marie Angel; © Andrew Zega and Bernd Dam; © Suzanne Moore.

Two artists whose abecedaries blend the calligraphic and typographic are Robert de Vicq de Cumptich and Cathryn Miller. In de Cumptich’s Bembo’s Zoo (2000), letters and punctuation marks from the Bembo typeface form calligraphic animal shapes. Miller’s L is for Lettering (2011) joins up the alphabetic rite of passage, calligraphy and typography by allying each of her hand-drawn letters with the name of a typeface from “A is for Arial” to “Z is for Zapfino”.

Left: A from De Cumptich’s Bembo’s Zoo. Right: Z from Miller’s L is for Lettering. Photos of the books: Books On Books Collection. Copyright in the works: © Robert de Vicq de Cumptich; © Cathryn Miller.

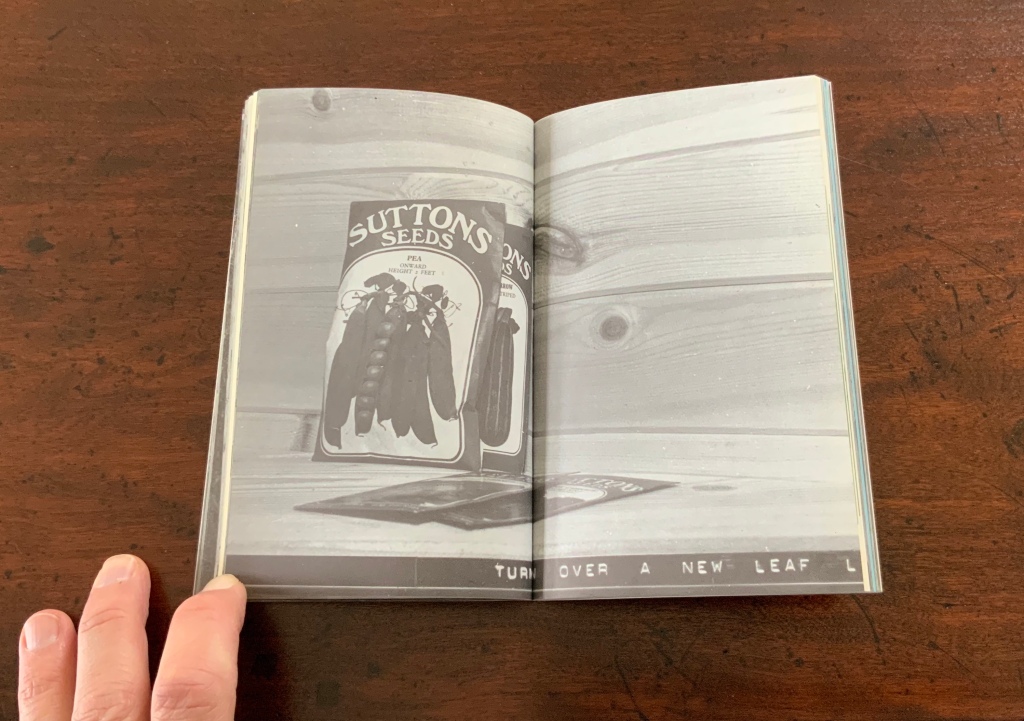

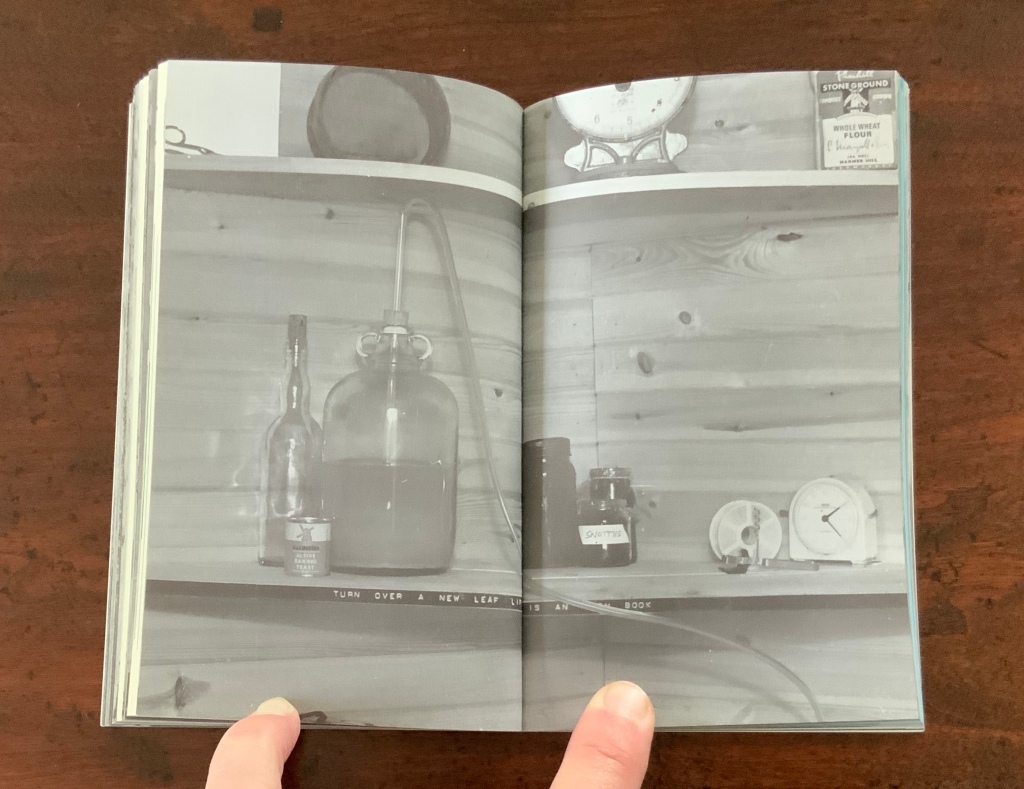

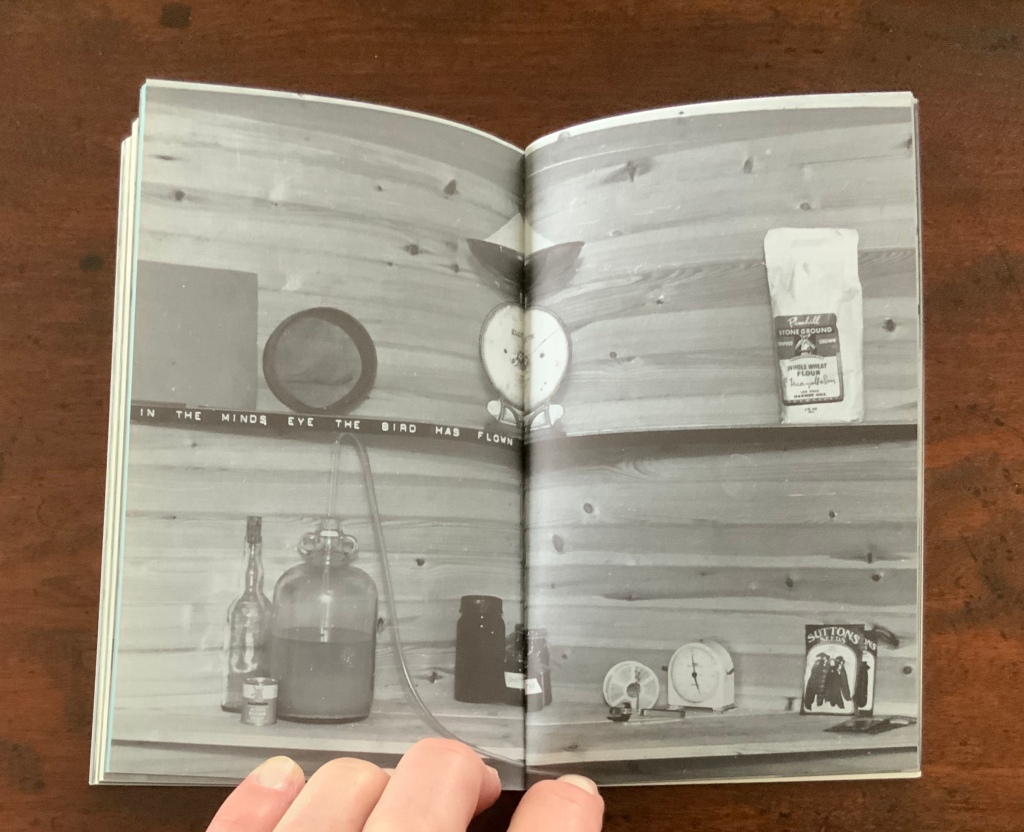

The last page of Tory’s illustration of additional alphabets is not the end of his work. The colophon plays that role. Curiously, Tory misses out the character that plays that role for the alphabet itself: the ampersand. “Curiously” because the character & appears throughout Champ Fleury — even at the end of the colophon’s fourth line in French — and it is after all the most flowery of the alphabet’s characters. Perhaps some book artist will follow Bruce Rogers’ example in his joking Depression-era homage to Tory on the back of Champ Rosé and create an homage to Tory and Rogers of three-dimensional ampersands.

Colophon: 1529 original from the Bibliothèque national de France; 1927 translation & facsimile © The Grolier Club; 1998 facsimile © Bibliothéque de l’Image. Photos of the latter two books: Books On Books Collection.

Champ Rosé (1933)

© Bruce Rogers

Photos of the book: Left, Courtesy of Veatchs; Right, Books On Books Collection.

The 1529 original of Champ Fleury can be viewed online in Gallica (BnF), de France, the Library of Congress or the British Library. The V&A’s National Art Library and a few other venues also have physical copies for inspection.

Further Reading

“Abecedaries I (in progress), Books On Books Collection, 31 March 2020.

“The Colophon and the Left-over ‘i’“. 23 April 2019. Books On Books Collection.

Bernard, Auguste, and Ives, George B. 1909. Geofroy Tory : Painter and Engraver: First Royal Printer: Reformer of Orthography and Typography Under François I ; an Account of His Life and Works. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Bowen, Barbara C. 1979. “Geofroy Tory’s “Champ Fleury” and Its Major Sources.” Studies in Philology 76, 1: 13-27. Accessed May 28, 2021.

De Looze, Laurence. 2018. The Letter and the Cosmos: How the Alphabet Has Shaped the Western View of the World. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Elliman, Paul. Spring 1998. “My typographies: A personal view on the kinship of type and things“. Eye Magazine, 27: 58-63.

Gelb, Ignace J. 1974. A Study of Writing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Golec, Michael. 2015. “Champ Fleury in the Machine Age”, lecture at the School of Visual Arts, NYC. Uploaded 4 June 2015. Accessed 12 May 2021. Good slides and a comparative look at Tory’s original and Rogers’ resetting.

Havelock, Eric A. 1986. The Muse Learns to Write: Reflections on Orality and Literacy from Antiquity to the Present New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ivins, William M. 1920. “Geoffroy Tory.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 15, 4: 79-86. Accessed May 13, 2021.

McNeil, Paul. 2017. The Visual History of Type. London: Laurence King Publishing.